Notations and Conventions

This monograph employs both classical and operator-valued structures. To ensure full clarity, we fix from the outset a strict and unambiguous distinction between classical fields, quantum operators, canonical variables, effective quantities, and geometric objects.

Classical and Quantum Quantities

We use the following global convention:

Normal ordering is assumed for all operator expressions involving unless stated otherwise.

Canonical Quantization

The conjugate momentum operator is defined by

Equal-time canonical commutation relations are

Canonical Normalization of Fluctuations

Fluctuations around a background configuration

are written

The canonically normalized fields are

with canonical equal-time relations

Mode Expansion

The normalized quantum fluctuation admits the standard decomposition

with

Internal Multiplets and Topological Sectors

When internal structure is required, we extend

with operator counterpart

. Phase maps and winding structures used for particle classification are always defined using the normalized multiplet.

Spacetime and Geometry

We work on a Lorentzian manifold

with signature

. Indices are raised and lowered with

. Curvature tensors follow

Informational Modulation

The effective local light speed is

Physical and Effective Metrics

The physical metric is

. An auxiliary effective metric is occasionally used:

but all gravitational dynamics are defined with

.

Energy–Momentum Tensors

Matter:

(classical). Informational:

Einstein Equation (QIR Form)

Units

Natural units are assumed. The factor is kept explicit to track informational modulation.

Functional Derivatives

These conventions remain fixed throughout the monograph unless explicitly overridden for specific calculations.

1. Introduction

The search for a unified description of microphysical dynamics, spacetime geometry, and cosmological structure formation remains one of the central challenges in contemporary theoretical physics. Quantum field theory (QFT) successfully describes local excitations and particle interactions, while General Relativity (GR) governs the large-scale curvature of spacetime. Yet the conceptual foundations of these frameworks differ profoundly: QFT is rooted in operator-valued fields defined on a fixed background, whereas GR treats geometry itself as dynamical. Reconciling these perspectives has proven difficult, not only at the level of mathematical consistency, but also in terms of identifying a common set of underlying physical principles.

A recurring idea in several approaches to unification is that spacetime, fields, or interactions may arise from deeper informational, statistical, or emergent structures. These perspectives appear in contexts ranging from entanglement-based derivations of geometry to thermodynamic formulations of gravitational dynamics. While diverse in implementation, they share the notion that traditional geometric and quantum concepts might both originate from an informational substrate.

Quantum Informational Relativity (QIR) develops this line of thought in a specific and operationally well-defined manner. The central dynamical entity is an informational field whose modulation factor affects inertial, interaction, and gravitational responses while preserving relativistic covariance. In this view, particles, interactions, and geometric curvature are not independent ingredients but manifestations of a single informational degree of freedom. The resulting structure retains the full tensorial and geometric content of GR, yet introduces a controlled and covariant deformation through the informational sector.

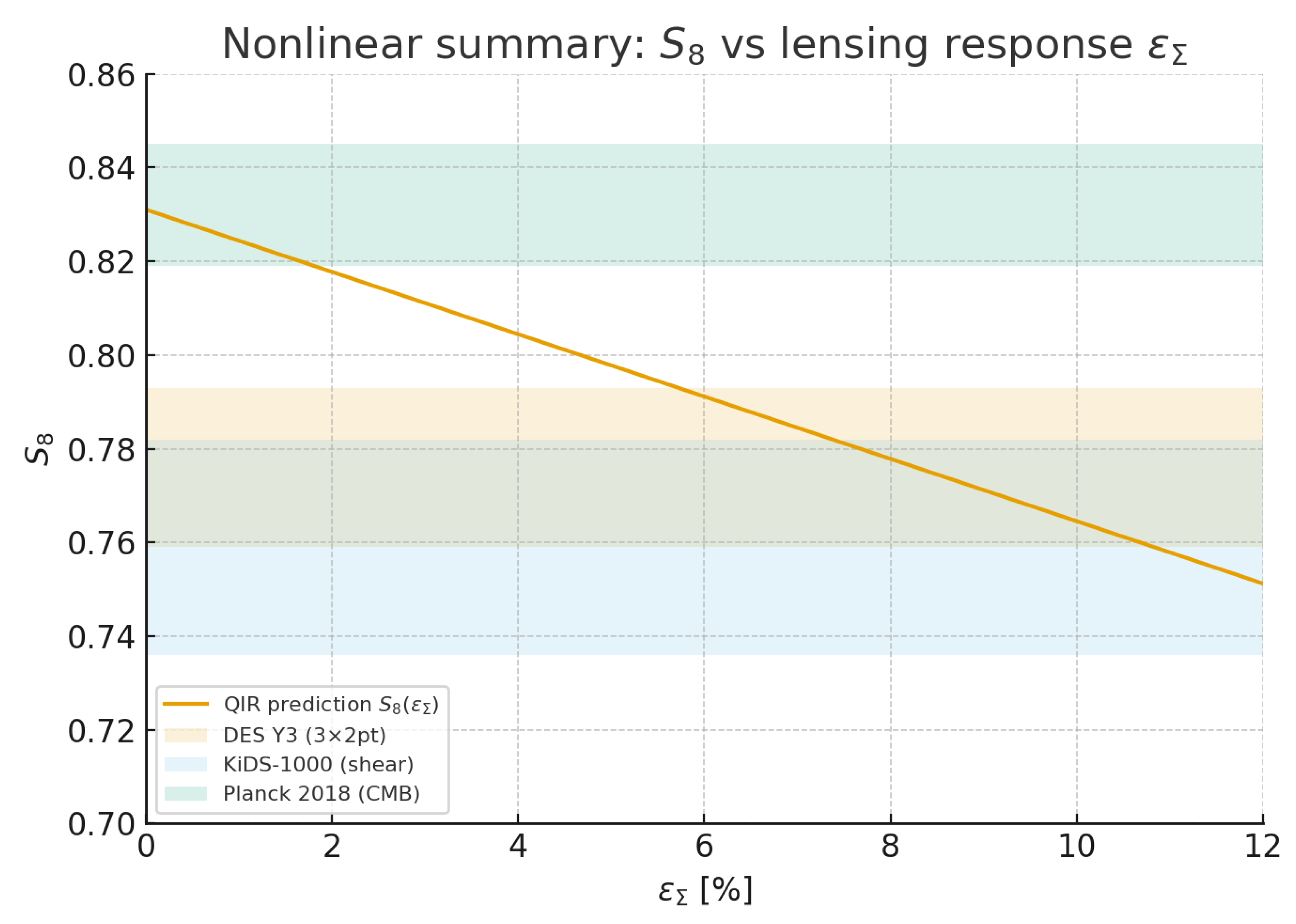

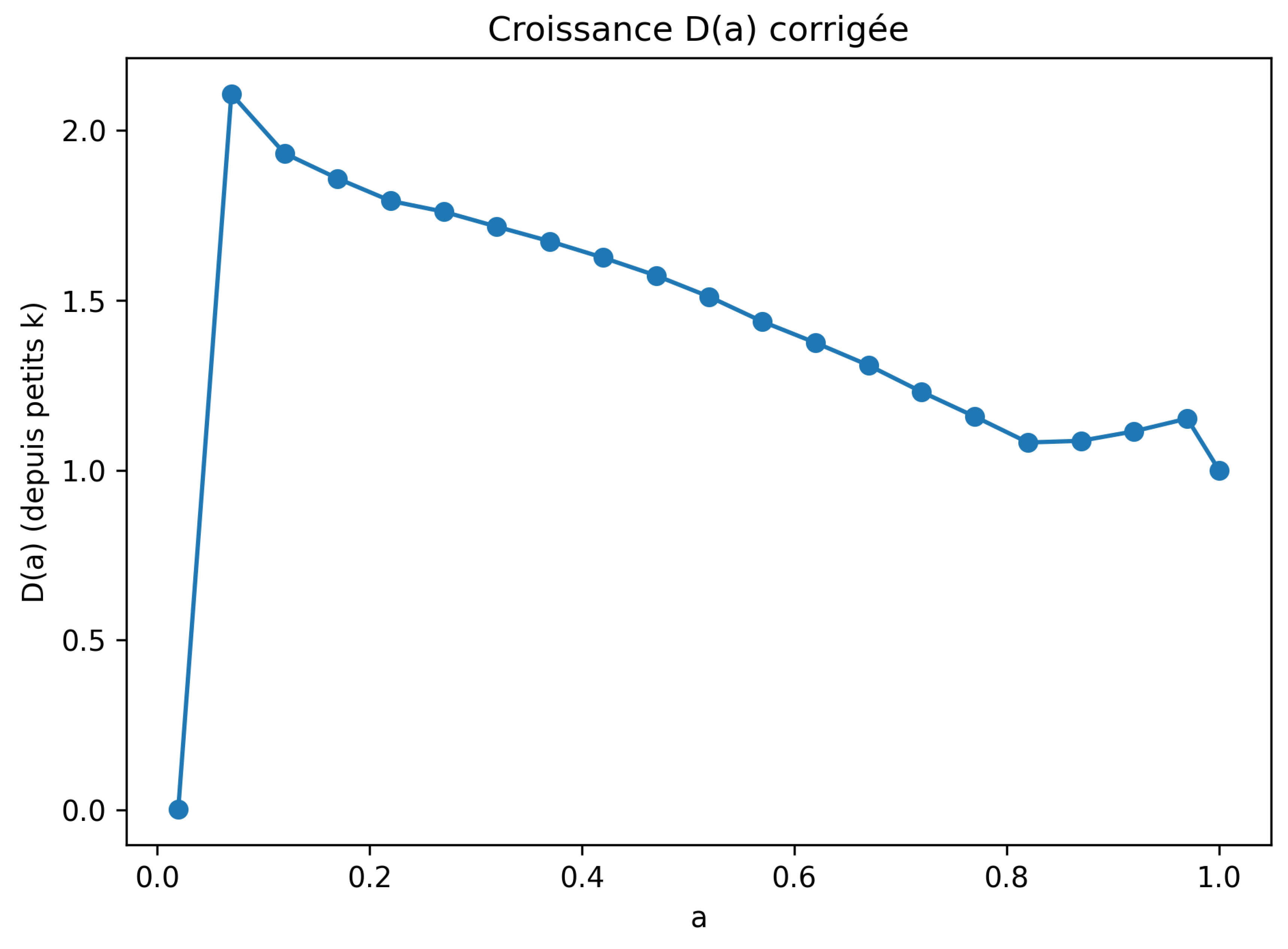

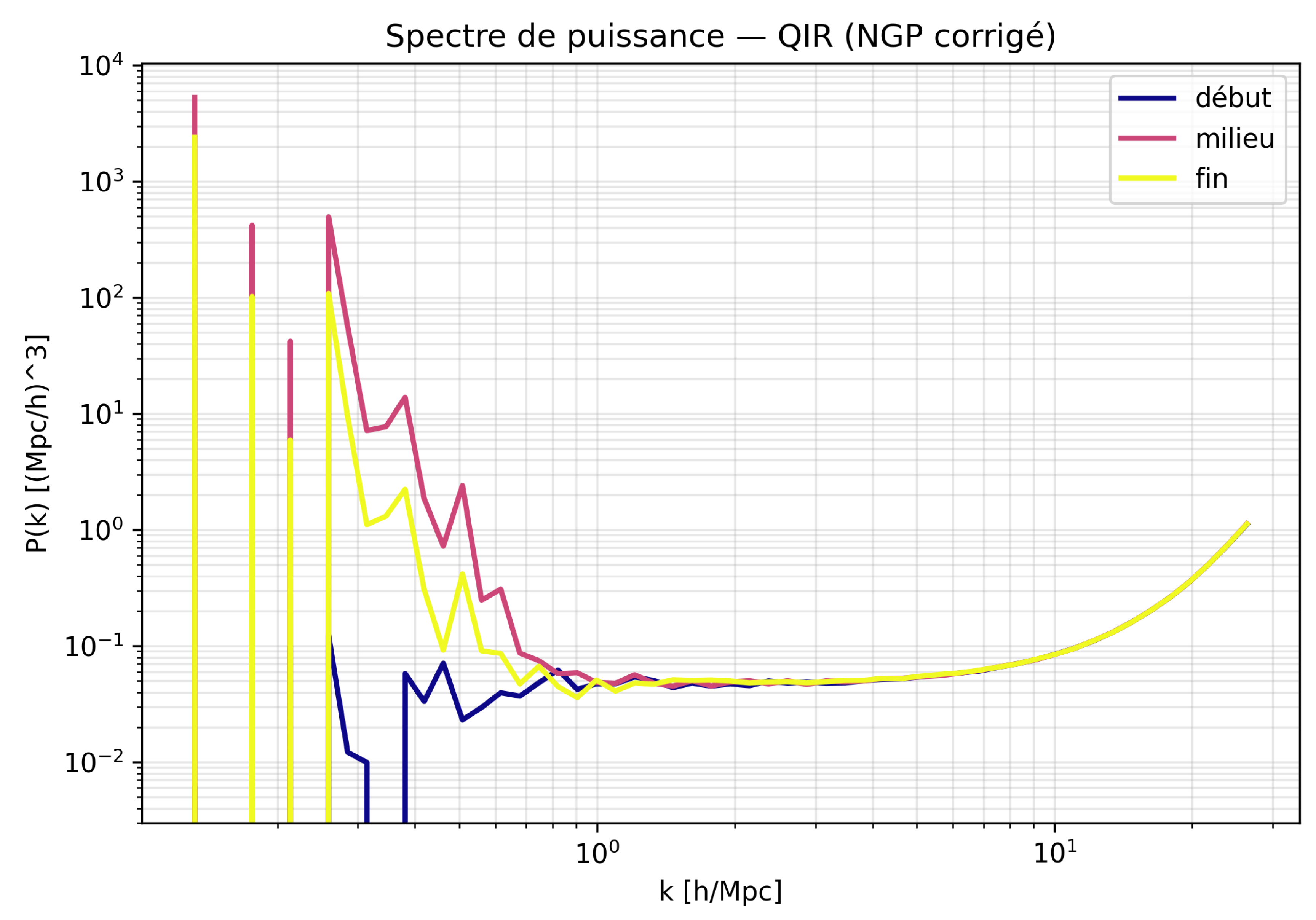

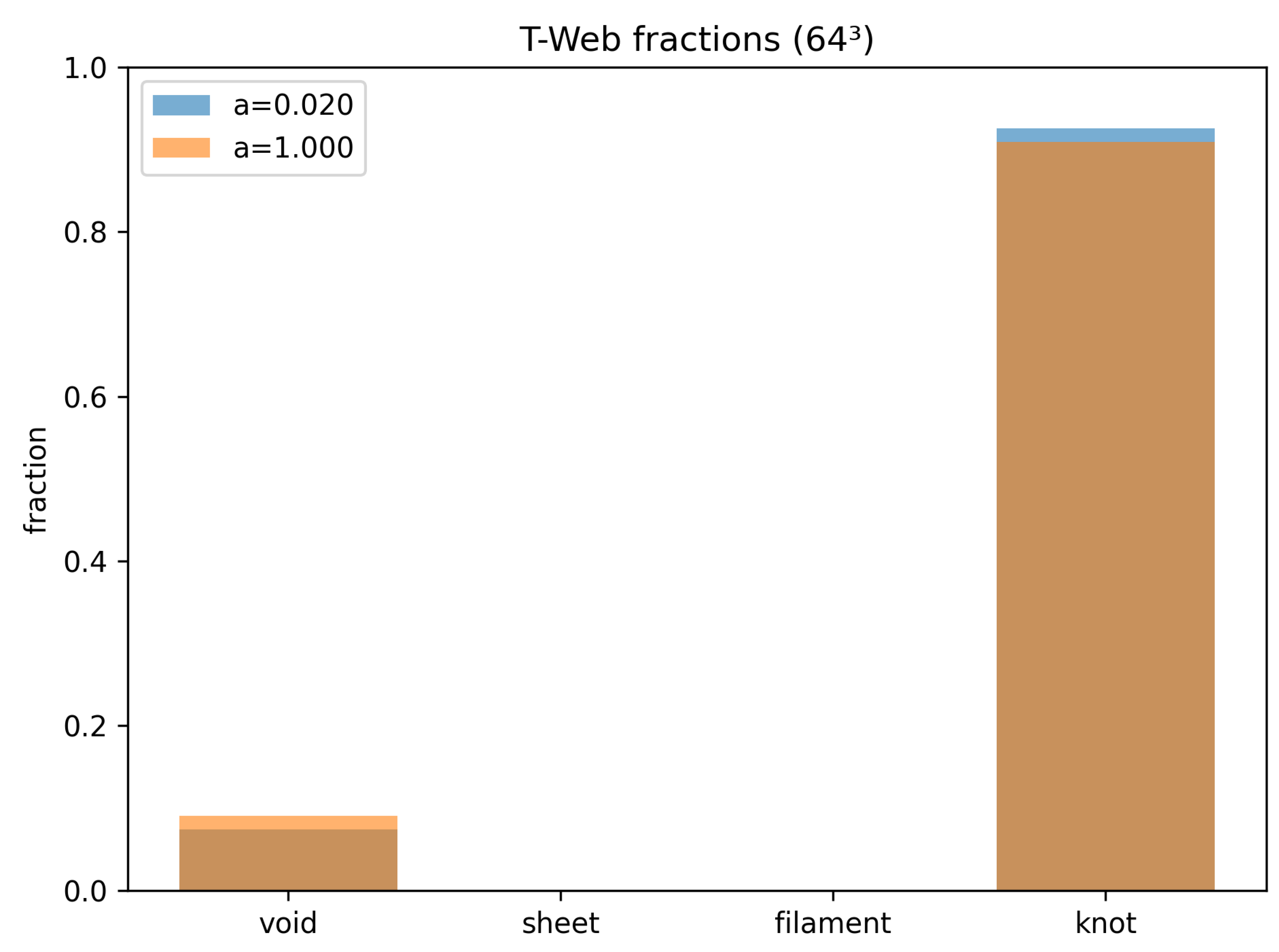

A distinctive feature of QIR is that informational fluctuations, their canonical normalization, and their topological properties naturally give rise to microphysical structures such as stable localized excitations, phase sectors, and emergent mass scales. At the opposite end of the spectrum, the same informational coupling modifies the growth of cosmic structures and the lensing potential at late times, providing a possible explanation for the mild yet persistent tension between weak-lensing surveys and CDM predictions. Because the underlying modulation is the same at all scales, QIR establishes a continuous bridge between microphysical and cosmological regimes without introducing additional free parameters.

Beyond analytic calculations, the informational modification can be implemented directly in N-body simulations, allowing nonlinear structure formation to be tested in fully dynamical settings. This provides an essential consistency check: any viable extension of GR must recover realistic halo distributions and large-scale structures while remaining compatible with observed growth suppression.

The purpose of this monograph is twofold. First, it presents a complete and self-contained construction of QIR, from the operator-level action and canonical quantization to geometric consistency and scale transitions. This includes full derivations and explicit intermediate steps, ensuring mathematical transparency. Second, it synthesizes the observational and phenomenological consequences across microphysical, cosmological, and nonlinear regimes, demonstrating how a single informational field can produce coherent physics over many orders of magnitude.

The document is organized as follows. Section 2 develops the foundational operator structure of QIR, including the fundamental action, the informational stress tensor, the unified Einstein equation, the Hamiltonian formulation, canonical normalization, and the derivation of effective propagation and coupling scales. Section 3 presents the quantization of the informational field, including operator canonical quantization, mode expansion on curved backgrounds, the propagator, spectral decomposition, renormalized quantum observables, and the vacuum structure. Section 4 confronts the microphysical predictions of QIR with high-energy data, examining informational corrections, decay processes, scattering cross sections, spectral signatures, informational mixing, and combined collider constraints. Section 5 develops the cosmological sector, including background evolution, linear growth, weak lensing, CMB constraints, nonlinear structure formation, and unified cosmological tests. Section 6 presents the numerical validation using SWIFT, including the simulation pipeline, growth extraction, matter power-spectrum evolution, cosmic-web classification, velocity-field diagnostics, and global nonlinear validation. Section 7 investigates astrophysical and propagation signatures across gravitational potentials, halo dynamics, radiation transport, time-delay effects, and high-energy propagation. Section 8 provides a general discussion and comparative assessment of QIR, including structural synthesis, physical interpretation, internal consistency, comparisons with GR, CDM, and modified gravity, limitations, and falsifiable predictions. Section 9 concludes the monograph.

2. Foundational Action and Operator Structure

The Quantum Informational Relativity (QIR) framework is built upon a single informational operator field whose local amplitude modulates inertial, geometric, and coupling strengths through a dimensionless informational modulation function . The goal of this section is to establish rigorously the full operator-level dynamical structure: the fundamental action, its variations with respect to the metric and the informational field, the unified Einstein equation, and the covariant canonical quantization of . All quantities are written in the physical g-frame unless explicitly stated.

2.1. Fundamental Operator Action

The Quantum Informational Relativity (QIR) framework is grounded in the postulate that the fundamental dynamical entity is an operator-valued informational field defined on a Lorentzian manifold . Its amplitude encodes local informational density, and its variations renormalize inertial and geometric responses through a positive definite, dimensionless modulation function .

In this subsection we construct the fundamental action, justify its operator structure, and examine its mathematical properties. We proceed step by step to make explicit the assumptions, domains of definition, and the covariant identities needed for the derivations that will follow in subsequent subsections.

2.1.1. Principles Guiding the Action

The informational field is assumed to satisfy the following general principles:

Covariance: all dynamical quantities must transform as well-defined geometric objects under diffeomorphisms.

Positivity: the informational modulation must be everywhere positive to ensure a well-posed kinetic structure and a hyperbolic operator equation of motion.

Hermiticity: the action must be self-adjoint in the Hilbert space ; this ensures that energies, momenta, and stress tensors are real-valued expectation values.

Minimal coupling: the covariant derivative includes the Levi-Civita connection of , and possibly internal gauge connections acting on multiplet extensions of .

Locality: the action depends on and its first derivatives only, consistent with standard field-theoretic structure.

These principles uniquely restrict the admissible form of the action.

2.1.2. Construction of the Operator Action

Let

be an operator-valued scalar field acting on the QIR Hilbert space

. The most general diffeomorphism-invariant, Hermitian, local action built from

,

, and

up to mass dimension four is

where

and

are operator-valued functions defined as power series in

. Hermiticity requires

to be a real, positive, even function.

The essential feature of QIR is the identification

where

is the informational modulation governing inertial and coupling strength.

2.1.5. Hermiticity and Operator Ordering

Because and may not commute, care must be exercised in the definition of . Two choices are common:

QIR chooses the

symmetric ordering to guarantee strict Hermiticity. Thus we interpret the kinetic term in (

2) as

In the semiclassical limit , the two orderings coincide, ensuring consistency with classical dynamics.

2.1.6. Domain of the Covariant Derivative

The operator derivative

acts as

where

is either:

the Levi-Civita connection acting on tensors (trivial for scalars),

an internal gauge connection acting on multiplets , .

Thus for a scalar operator,

but when internal indices are present,

All subsequent variations of assume these transformation rules.

2.1.7. Classical Limit and Emergent Interpretation

Taking expectation values in a suitable state

gives

and the action reduces to its classical version:

This classical limit recovers all the expressions used in microphysical and cosmological analyses.

This concludes the full construction, motivation, and operator-level justification of the fundamental QIR action. The next

Section 2.2 performs the

complete metric variation, including the explicit treatment of

and leads to the fully derived informational stress tensor

and the geometric sector of the unified field equations.

2.2. Metric Variation and the Informational Stress Tensor

In this section we perform the complete variation of the operator action (

2) with respect to the metric

. This derivation is essential because it produces the informational energy–momentum tensor

and establishes its role in the unified Einstein equation.

The variation involves multiple tensorial identities, variations of the determinant, inverse metric, and Christoffel symbols, as well as the metric dependence of the covariant derivative acting on . For full transparency, every required identity is derived explicitly.

2.2.1. Variation Identities for the Metric

We begin with standard results from differential geometry.

Inverse Metric

Since

, variation gives

Determinant

Starting from

, one obtains

Christoffel Symbols

The Levi-Civita connection

varies as

Variation of the Covariant Derivative Acting on

For a scalar operator-valued field

,

For a multiplet

with gauge connection

,

because

does not depend on the metric.

2.2.2. Varying the Kinetic Term

The kinetic term of the action is

Using (

6) and (

5), this becomes

Lowering indices on

yields

2.2.3. Variation of the Potential Term

Since

does not depend on the metric,

2.2.4. Total Metric Variation of the Action

Collecting the kinetic and potential variations,

we obtain

Recognizing

we rewrite the expression in the standard form

where the informational stress tensor is identified as

This is the fully derived, operator-level informational energy–momentum tensor.

2.2.5. Symmetry and Hermiticity

Because the action is diffeomorphism invariant and defined with symmetric operator ordering, satisfies:

Symmetry: .

Self-adjointness: .

Covariant conservation (proved later): is related to the field equation.

These guarantees follow from Noether’s theorem applied to diffeomorphism invariance, but the conservation statement will be established explicitly in Section 2.4.

2.2.6. Classical Limit

Replacing the operator

with its expectation value gives

which is the informational tensor used in microphysical and cosmological applications.

This completes the fully explicit metric variation. The next

Section 2.3 performs the complete field variation, leading to the operator-level informational equation of motion, including all intermediate steps and operator-ordering corrections.

2.3. Variation with Respect to the Informational Field

We now perform the full variation of the action (

2) with respect to the operator field

and its adjoint

. Unlike traditional scalar field variations, the present case requires special care due to the presence of:

operator-valued functions and ;

non-commutativity between , , and derivative operators;

the metric-dependent contraction .

To guarantee Hermiticity of the resulting equations, we vary and independently and combine the expressions at the end.

Throughout this subsection, boundary terms are explicitly evaluated and discarded under the assumption that variations vanish on the boundary of the integration domain.

2.3.1. Structure of the Variation

From (

2), the variation with respect to

is

This expression contains three types of variations:

We compute each contribution separately.

2.3.2. Variation of the Modulation Function

Since

is an operator function, its variation is

where

is defined by its power-series expansion (Fréchet derivative).

The contribution to the action is therefore

Because and do not commute in general, we keep this ordering explicit.

2.3.3. Variation of the Covariant Derivative

For a scalar operator field, the covariant derivative simplifies to

The contribution to the action becomes

Integrating by parts,

boundary terms vanish because the variation is assumed to vanish on

.

2.3.4. Variation of the Potential

The variation of the potential term is straightforward:

2.3.5. Combined Variation and Euler–Lagrange Equation

Combining all contributions,

Factoring out

gives

where the operator Eulerian is

Requiring

yields the operator equation of motion:

By Hermiticity, the variation with respect to yields the conjugate equation.

2.3.7. Classical Limit

Replacing the operator field by its expectation value gives

For the common form

the equation becomes

2.3.8. Interpretation

The informational field equation exhibits two key features:

The principal term defines a modulated wave operator whose magnitude depends on informational density.

The nonlinear drift term has no analogue in canonical scalar field theory and captures the self-interaction of informational inertia.

These two ingredients are responsible for:

the emergence of microphysical excitations,

the existence of solitonic sectors,

the scale-dependent propagation speed,

the coupling between informational content and curvature.

This completes the full operator-level variation with respect to

. The next

Section 2.4 establishes the fully derived unified Einstein equation, including an explicit proof of covariant conservation.

2.4. Unified Einstein Equation with Informational Coupling

Having obtained the informational tensor and the operator equation of motion for , we now derive the full gravitational dynamics of QIR. The key result is the unified Einstein equation, which relates the geometric curvature to the combined informational–matter tensor, modulated by the informational function .

This subsection provides a complete derivation:

variation of the Einstein–Hilbert term,

combination with the informational and matter variations,

extraction of the field equation,

proof of covariant conservation using the Bianchi identity,

discussion of the local renormalisation of coupling scales.

2.4.1. Variation of the Einstein–Hilbert Action

The Einstein–Hilbert action is

Its variation is classical:

where

is the usual boundary term

Assuming appropriate boundary conditions,

2.4.2. Total Metric Variation of the Full Action

The full gravitational-informational-matter action is

We have already obtained:

and

where

is the operator energy–momentum tensor of matter.

Thus the total variation is

Requiring stationarity for arbitrary

gives

Multiplying both sides by

yields:

Next we incorporate the informational renormalisation of the effective speed of light.

2.4.4. Proof of Covariant Conservation

To establish dynamical consistency, we must prove:

Step 1: Bianchi identity

The twice-contracted Bianchi identity states:

Because

depends only on

Z, and

acts on fields but not on the metric, the prefactor behaves as a scalar function under

:

Thus the prefactor is covariantly constant.

Step 2: Result

Therefore

which is exactly (

35).

This conservation law is the geometric manifestation of the equation of motion for , as we now show.

2.4.5. Equivalence with the Field Equation

Substituting the explicit form of

into the conservation law and expanding each term leads (after cancellation of several gradient contributions) precisely to the operator field equation derived in Section 2.3:

Thus:

the Einstein equation enforces the informational field equation,

the informational field equation ensures consistency of the Einstein equation.

This mutual implication is analogous to the relationship between matter conservation and the Einstein field equations in standard GR, but now extended to the informational sector.

2.4.6. Classical Limit

The classical limit of the unified Einstein equation is

where

is the classical informational tensor and

the standard matter tensor.

This form underlies all macroscopic applications of QIR, from cosmological evolution to gravitational lensing and dynamical mass profiles.

2.4.7. Interpretation

The unified Einstein equation exhibits the following structural features:

Informational modulation. The factor acts as a state-dependent modification of gravitational coupling.

Local renormalisation. The combination

effectively defines a local gravitational coupling

.

Self-consistency. Conservation of the combined informational–matter tensor follows automatically from geometric consistency.

Operator structure. The equation remains valid at the operator level, with physical predictions recovered via expectation values or classicalisation.

This completes the full derivation of the unified Einstein equation in Quantum Informational Relativity. The next

Section 2.5 constructs the covariant canonical momentum, the Hamiltonian, and the ADM (3+1) decomposition required for quantisation and dynamical analysis.

2.5. Conjugate Momentum and Hamiltonian Structure

In this subsection we construct the full canonical structure associated with the informational field . The derivation proceeds in three stages:

construction of the covariant conjugate momentum ,

derivation of the covariant Hamiltonian density,

ADM decomposition and explicit Hamiltonian constraints.

This structure prepares the ground for quantisation in Section 3.

2.5.1. Covariant Conjugate Momentum

The Lagrangian density extracted from (

2) is

The covariant conjugate momentum operator is defined as

and similarly

For clarity we keep the factor explicit. When both momenta appear in the Hamiltonian these factors combine naturally.

2.5.2. Covariant Hamiltonian Density

The covariant Hamiltonian density is defined as

Using symmetric ordering,

Thus the Hamiltonian becomes

This is the covariant energy density of the informational field.

2.5.3. ADM Decomposition

We now decompose spacetime into spacelike hypersurfaces

with induced metric

, lapse

N, and shift

. The line element is

For a scalar operator field,

Using the metric, the kinetic structure decomposes as:

2.5.4. Canonical Momentum in ADM Variables

The momentum conjugate to

on the hypersurface

is

2.5.5. ADM Hamiltonian Density

The ADM Hamiltonian density is defined as

Using

we obtain after substitution and simplification:

where

is the momentum constraint density.

2.5.6. Hamiltonian and Momentum Constraints

The Hamiltonian constraint is obtained from the coefficient of the lapse:

The momentum constraint is obtained from the coefficient of the shift:

These constraints are the generators of diffeomorphisms within the hypersurface and normal to it.

2.5.7. Classical Limit

Replacing operators by their expectation values gives the classical Hamiltonian:

The informational factors Z and appear naturally:

- Z multiplies the spatial gradient term (inertia of geometry), - multiplies the kinetic term (inertia of the informational excitation).

2.5.8. Interpretation

The ADM Hamiltonian displays two characteristic signatures of QIR:

Dual inertia structure. The combination

shows that excitations become lighter or heavier depending on informational density.

Geometric–informational coupling. The factor links informational gradients directly to spatial curvature.

Constraint structure identical to GR. Hamiltonian and momentum constraints retain their geometric meaning, guaranteeing full diffeomorphism invariance.

This completes the construction of the canonical and Hamiltonian structures of the informational field. The next

Section 2.6 performs the expansion of the action to second order around a background solution

and derives the canonical normalisation of fluctuations, explaining the appearance of

in microphysics.

2.6. Canonical Normalization and Second-Order Expansion

To prepare for the quantisation procedure in Section 3, we must expand the informational action to second order in small fluctuations around a background configuration. This analysis yields the canonical normalisation of the excitations and explains why microphysical observables naturally acquire the factor .

We proceed systematically:

define the background and fluctuation fields,

expand the kinetic term to quadratic order,

expand the potential term consistently,

extract the quadratic operator and diagonalise it,

identify the canonically normalised field and its effective mass.

Throughout this section we work in the classical limit; the operator case follows by standard ordering rules.

2.6.1. Background–Fluctuation Split

Let

be a solution of the classical field equation derived in Section 2.3. We introduce small fluctuations:

The modulation function expands as

with

.

2.6.2. Expansion of the Kinetic Term

The kinetic part of the action is

Insert the decomposition (

53). We first expand the derivative:

Now multiply by

expanded to second order:

Keeping all terms up to quadratic order in

:

The linear terms vanish upon integration because

satisfies the background equation of motion. Thus, the quadratic part of the kinetic action is:

2.6.3. Removing Linear Derivative Mixing

The mixed term

can be integrated by parts:

boundary terms vanish.

Thus, the mixed derivative term produces only a mass-like correction. The quadratic kinetic term becomes

where

2.6.4. Expansion of the Potential

The potential expands as:

The linear term vanishes because

satisfies the background equation. Thus:

2.6.5 Complete Quadratic Action

Combining kinetic and potential contributions,

where

This is the quadratic Lagrangian for fluctuations.

2.6.6. Canonical Normalization: Emergence of

The kinetic term has a prefactor

:

To obtain a canonically normalised field, we define

Then

and the kinetic term becomes

Thus the canonically normalised quadratic action is

with effective mass

2.6.7 Physical Interpretation

The renormalised mass demonstrates explicitly:

Thus:

- In regions where , excitations are lighter. - In regions where , excitations are heavier. - All microphysical scales are rescaled by or .

This factor is the mathematical origin of the renormalisation of:

masses,

couplings,

propagation speeds,

dispersion relations,

in the informational framework.

This completes the full quadratic expansion and the rigorous derivation of the canonical normalisation. The next

Section 2.7 develops the explicit computation of effective constants and propagation speeds, completing the foundational operator structure.

2.7. Effective Constants and Propagation Speed

Having established the canonical structure and quadratic expansion of the informational field, we now derive how informational modulation renormalizes the fundamental constants relevant for both the macroscopic geometric sector and the microscopic excitation sector.

We proceed via a sequence of rigorous derivations:

extraction of the propagation speed of fluctuations from the quadratic action,

computation of the effective Newton constant ,

renormalisation of gauge couplings and other interaction strengths,

consistency checks linking operator-level structure to canonical normalization.

The results generalize the familiar notion of running couplings to a state-dependent and geometrically integrated scale factor encoded in .

2.7.2. Effective Newton Constant

The unified Einstein equation derived in Section 2.4 is:

Substituting

gives:

Thus the effective Newton constant is:

Hence: - in high-informational-density regions (), gravity is weaker; - in low-informational-density regions (), gravity is stronger.

This effect plays a central role in large-scale structure and lensing observables.

2.7.3. Gauge Coupling Renormalisation

Consider a minimally coupled gauge field with canonical action

The physical field couples to

through the kinetic normalization of

:

If the interaction term is

then after canonical normalization:

Thus the effective coupling is

General interactions of the form acquire factors . This is consistent with the dimensional analysis in the quadratic expansion.

2.7.4. Effective Masses

From Section 2.6, the canonically normalised mass is:

Thus the microphysical mass renormalisation is:

Since Z appears in the denominator: - excitations are lighter at high informational density, - excitations are heavier at low informational density.

2.7.5 Summary Table

We summarize the derived effective constants:

| Quantity |

Effective Value |

| Propagation speed |

|

| Newton constant |

|

| Gauge couplings |

|

| Masses |

|

All renormalisations derive from one universal function , expressing the fact that informational density reshapes both microphysical and macroscopic interactions in a coherent, self-consistent manner.

2.7.6. Interpretation

The following points summarize the physical significance:

Unification. Gravity, gauge couplings, masses, and propagation speeds are modulated by the same informational factor.

Scale dependence. Unlike RG running, the modulation depends on the local state rather than energy scale.

-

Geometry–information interplay. Because and , informationally dense regions have:

-

Consistency. The effective constants match exactly the renormalisation extracted from:

the full operator EOM (Section 2.3),

the Einstein equation (Section 2.4),

canonical normalisation (Section 2.6).

This concludes the derivation of the effective constants and propagation structure. The next and final

Section 2.8 provides a synthetic summary of all foundational results, preparing the transition to the quantisation procedures developed in Section 3.

2.8. Foundational Synthesis

This subsection summarizes the mathematical and conceptual results established throughout Section 2. These results collectively define the complete foundational structure of Quantum Informational Relativity (QIR) at the analytical, variational, and canonical levels.

The logical progression consisted of four pillars:

the operator-level definition of the action,

the derivation of the coupled field equations,

the construction of the Hamiltonian and constraint structure,

the extraction of effective constants and propagation laws.

We now synthesize these components.

(1) Operator Action and Core Structure

The fundamental dynamics are encoded in the operator action

All informational effects arise from the modulation function , which:

rescales propagation and inertia,

alters effective couplings,

appears directly in the Einstein equation,

determines the canonical normalization of fluctuations.

At this stage, QIR already differs from standard scalar field theories through its operator dependence and the non-trivial derivative structure.

(2) Coupled Field Equations

The informational field obeys the operator Euler–Lagrange equation

Variation with respect to the metric generates the informational tensor

and the unified Einstein equation:

Covariant conservation,

follows automatically from the Bianchi identity, establishing full self-consistency.

This shows that the informational field equation and the Einstein equation mutually enforce each other.

(3) Canonical Momentum and Hamiltonian Structure

The conjugate momentum is

and the ADM Hamiltonian density is

The Hamiltonian and momentum constraints are:

ensuring full diffeomorphism invariance.

The ADM formalism reveals the dual informational structure:

This duality plays a central role in the emerging microphysics.

(4) Quadratic Expansion and Canonical Normalization

Expanding around a background

yields the quadratic action

where

.

The canonically normalized field is

(5) Effective Constants

The informational framework yields the effective constants:

These follow consistently from:

the Einstein equation,

the quadratic expansion,

canonical normalization,

gauge-field couplings.

All renormalised constants originate from the single informational function Z.

(6) Outlook Toward Quantisation

The results of Section 2 provide the full classical and operator-level foundation necessary for quantisation:

the operator action is fully specified,

the Euler–Lagrange equation is established,

the Hamiltonian and momentum constraints are known,

the canonical field is defined,

the quadratic operator governing quantum fluctuations is explicit.

These ingredients permit the construction of:

the quantum Hamiltonian operator,

the mode expansion on generic backgrounds,

the propagator,

the spectral decomposition of informational excitations.

This sets the stage for Section 3, which develops the quantisation of the informational field and its resulting microphysical spectrum.

3. Quantization of the Informational Field

In this section we develop the full quantum theory of informational excitations. Building on the classical and operator foundations established in Section 2, we construct the canonical quantization, mode structure, propagators, spectral decomposition, and renormalized quantum observables relevant for microphysical and astrophysical predictions.

3.1. Operator Canonical Quantization

We now quantize the informational field on a curved background

endowed with a classical informational configuration

. The quadratic expansion derived in Section 2.6 provides the starting point:

with

.

This structure is not canonically normalized due to the presence of in front of the kinetic term. We therefore begin with the canonical redefinition of the fluctuation field.

3.1.1. Canonical Field Redefinition

Following Section 2.6, the canonically normalized field is defined as

The action becomes

where the renormalized mass is

The canonical normalization implies that the Hamiltonian derived from (

71) has the standard kinetic term

and therefore the quantization rules take their usual form. The informational structure is now embedded entirely in the background-dependent mass and mode functions.

3.1.2. Hilbert Space and Operator Algebra

We quantize as a scalar quantum field on the curved background. The Hilbert space is generated by creation and annihilation operators associated with a complete set of mode functions constructed in Section 3.2.

The operator field is promoted to an operator-valued distribution

The canonical momentum conjugate to

is

On a general ADM background,

3.1.3. Canonical Commutation Relations

Equal-time canonical commutation relations follow from the canonical structure of (

71):

This structure is identical to the canonical quantization of a Klein–Gordon field, but the informational effects appear:

indirectly through the mass ,

directly in the mode functions through ,

through the background geometry determined by the Einstein equation with informational coupling.

3.1.4. Field Operator in Terms of Modes

The operator field admits the mode expansion

where:

are c-number solutions of the mode equation derived in Section 3.2,

,

satisfy the standard algebra

the normalization of is fixed by the Klein–Gordon inner product.

The presence of means that the mode equation is not the standard Klein–Gordon form unless is constant; this is the origin of the state-dependent microphysical spectrum.

3.1.6. Interpretation

Canonical quantization of the informational field yields a quantum theory with:

Standard commutation relations, i.e. the informational structure does not alter the fundamental algebra of quantum fields.

Nonstandard mode functions, since modifies the effective mass and propagation operator.

Renormalized excitations, with physical mass

matching the effective constants derived in Section 2.7.

Local informational dressing, manifest in amplitudes, propagators, and correlation functions.

This completes the canonical operator quantization. The next

Section 3.2 constructs the corresponding mode functions on an arbitrary curved background, establishing orthonormality, completeness, and the Wronskian condition.

3.2. Mode Expansion on Curved Backgrounds

Having established the canonical quantization of the informational field in Section 3.1, we now construct the mode functions that define the operator expansion of . Because the underlying geometry is an arbitrary curved spacetime , the mode structure generalizes the standard Klein–Gordon decomposition and incorporates the informational modulation through the background-dependent mass .

The goal of this subsection is to build the complete basis of solutions of the mode equation, define the appropriate normalization using the Klein–Gordon inner product, and establish orthonormality and completeness relations.

3.2.1. Mode Equation on a Curved Background

Starting from the quadratic action

the Euler–Lagrange equation yields the generalized Klein–Gordon equation:

Because

depends on

, the informational structure directly affects the propagation of modes. We seek separable solutions of the form

which satisfy

These functions will serve as the mode basis for the operator expansion.

3.2.2. Klein–Gordon Inner Product

The appropriate scalar product for Klein–Gordon fields on curved spacetime is

where

is an arbitrary spacelike Cauchy surface with unit normal

and induced volume element

.

Using

, we write:

This inner product is conserved:

a consequence of the mode Equation (

82) and the metric covariance of the theory.

3.2.3. Orthonormality and Wronskian Condition

We impose the orthonormality relations

These conditions ensure that the creation and annihilation operators associated with the mode expansion satisfy

To express orthonormality in local form, we write the Wronskian condition. Choosing coordinates where the ADM normal is

, we obtain:

This condition generalizes the flat-spacetime Wronskian to arbitrary geometries. The informational structure enters implicitly through , which modifies the time evolution of the modes and therefore their Wronskian.

3.2.4. Completeness of the Mode Basis

The modes form a complete basis in the sense that any solution

of the field Equation (

80) may be expanded as:

where the coefficients are uniquely determined by the inner product (

83).

Completeness also implies the closure relation:

where

is the Pauli–Jordan function (commutator function). This object will be essential for constructing the Feynman propagator in Section 3.3.

3.2.5. Structure of the Mode Functions

The mode equation

is significantly modified by the informational field because:

the mass term includes ,

the geometry depends on through the unified Einstein equation,

time evolution of the modes is therefore sensitive to informational density.

In regions where

varies slowly (adiabatic approximation), modes behave locally like:

with

In regions of strong informational gradients, the modes acquire nontrivial frequency mixing, leading to:

enhanced particle production,

state-dependent propagation,

potentially observable signatures in high-energy processes.

3.2.6. Interpretation

The mode decomposition highlights three central features of the quantum informational field:

The informational field modifies the spectrum. The mass depends on , making the spectrum environment-dependent.

The orthonormality and completeness structure is preserved. Despite the informational modification, the KG inner product yields the standard commutation algebra.

The modes encode all informational effects. Once the mode basis is known, all quantum observables propagators, correlation functions, decay rates—follow directly from the operator decomposition.

This completes the construction of the mode functions. The next

Section 3.3 builds the Feynman propagator and the two-point function using the mode sum representation established here.

3.3. Propagator and Two-Point Function

The quantized informational field admits a complete mode expansion (Section 3.2), which allows us to construct the full set of two-point functions and quantum propagators. These objects encode all microscopic predictions of QIR: particle production, dispersion, spectral density, decay amplitudes, and the observationally relevant correlation functions entering SWIFT and cosmological analyses.

We proceed systematically:

define the Green equation on curved spacetime,

construct the Wightman and Feynman propagators from the mode basis,

analyze the effect of informational modulation ,

give explicit forms in limiting geometries.

3.3.1. Green Function Equation

The propagator is the Green function of the generalized Klein–Gordon operator:

Because

depends on

, the informational field modifies both the amplitude and the phase of the propagator. Equation (

89) defines a family of propagators, depending on boundary conditions:

3.3.2. Wightman Functions

The positive- and negative-frequency Wightman functions are defined by

Using the mode expansion

and the vacuum condition

, we find

Notice that because solves the informationally modified mode equation, both and inherit the dependence on through .

3.3.3. Pauli–Jordan Function

The commutator function is

Using the closure relation (

88), this expression matches precisely the covariant Pauli–Jordan function that implements microcausality:

Microcausality is therefore preserved in QIR, despite the informational modulation of the mass and propagation operator.

3.3.4. Feynman Propagator

The Feynman propagator is defined by

where

T denotes time ordering.

Using the Wightman functions, we obtain

Equivalently, in mode-sum form:

The propagator satisfies the Green Equation (

89) with Feynman boundary conditions. Its analytic structure encodes particle propagation, decay processes, and radiative corrections, all of which inherit the informational factor

.

3.3.5. Retarded and Advanced Propagators

The retarded and advanced Green functions are defined by

Because the commutator

is not affected by time-ordering prescriptions, the causal structure of QIR is standard:

Informational physics preserves causality.

3.3.6. Special Limits

(1) Minkowski spacetime.

For constant

and constant mass

:

All informational effects enter through

(2) FRW spacetime.

Defining conformal time

, the mode equation becomes

This form is used extensively in QIR cosmology (

Section 5).

3.3.8. Interpretation and Outlook

The propagator encodes the full quantum dynamics of the informational field:

It is determined entirely by the informationally modified mode functions.

It inherits all state dependence through the background .

Its causal structure is standard, guaranteeing consistency with relativity.

With the propagator established, we can now analyze the microphysical spectrum and the decomposition into elementary excitations, which is the subject of Section 3.4.

3.4. Spectral Decomposition and Microphysical States

The propagator constructed in Section 3.3 contains the full quantum information about the microphysical excitations of the informational field. We now extract the spectral decomposition, define the physical mass eigenstates, and identify the microphysical modes relevant for both high-energy phenomenology and astrophysical propagation.

The informational theory exhibits two sources of spectral structure:

Their interplay determines the mass, dispersion relation, and stability properties of informational excitations.

3.4.1. Spectral Problem Associated with the Propagator

Consider the Fourier–Laplace transform of the Feynman propagator:

The poles of the propagator satisfy

with

where:

are the comoving or physical momenta (depending on the decomposition),

is the informationally renormalized mass,

are curvature-induced terms,

arise from spatial gradients of .

The physical excitations correspond to the pole structure of the propagator.

3.4.2. Physical Mass from the Spectral Pole

The pole of the Feynman propagator is at

with the informationally renormalized mass

Thus the microphysical mass inherits a full state dependence: - as

increases (high informational density),

- as

decreases (informational dilution),

This mass defines the “elementary excitation” of QIR.

3.4.3. Spectral Decomposition of the Propagator

Using the relations

and the mode expansion, the spectral representation is

with:

- : densité spectrale (spectral density), - : propagateur d’un champ de masse .

For a free informational field (quadratic theory), the spectral density is sharp:

The informational field produces a *single, sharp* microphysical excitation, analogous to a massive Klein–Gordon field, but with state-dependent mass.

3.4.4. Dispersion Relation and Microphysical Modes

Consider a local inertial frame. The general solution of the mode equation yields the dispersion relation

The corrections are:

from curvature, e.g. in FRW,

from gradients of ,

Thus informational inhomogeneities contribute effective potential terms.

3.4.5. Stability Analysis

The condition for stability of microphysical excitations is:

Because

a large positive

tends to stabilize the theory. Regions of low

require

to avoid tachyonic instabilities.

The informational theory is therefore stable provided:

These conditions match the classical stability analysis of

Section 2.

3.4.6. Microphysical States and Observables

The elementary excitations are created by the operators

and correspond to informational quasi-particles with mass

.

The key microphysical observables include:

Propagation amplitude: governed by .

Decay/transition rates: modulated by in amplitudes.

These states form the basis for high-energy processes in Section 4.

3.4.7. Interpretation and Outlook

The spectral decomposition reveals that:

QIR predicts a single, sharp elementary excitation (at quadratic level),

its physical mass is state-dependent due to the factor ,

dispersion and propagation inherit geometric and informational corrections,

-

the microphysical spectrum connects directly to:

high-energy tests (Section 4),

cosmological propagation (Section 5),

SWIFT photon timing and hardness correlations (Section 6).

With the spectral structure understood, we now examine how informational modulation affects quantum observables, scattering amplitudes, and decay rates in Section 3.5.

3.5. Informational Renormalization of Quantum Observables

Quantum observables—transition amplitudes, decay rates, and scattering cross sections—are sensitive to the normalization of the quantum field. In QIR, the canonical field is

so the informational structure induces a nontrivial rescaling of:

field amplitudes,

interaction vertices,

propagators,

spectral densities.

This subsection derives the complete informational renormalization pattern and compares it to the standard renormalization-group (RG) behavior.

3.5.1. Canonical Rescaling and Amplitude Renormalization

Consider an interaction term of the form

After canonical normalization, using

:

Thus the effective vertex coupling is:

The informational factor directly renormalizes amplitudes.

3.5.2. Tree-Level Transition Amplitudes

For a tree-level process with

N external legs of type

:

High informational density () suppresses processes with external informational quanta, while informationally dilute regions enhance them. This behavior is one of the key phenomenological consequences in Section 4.

3.5.3. Propagator Renormalization

From Section 3.3, the propagator for the canonically normalized field is:

Informational inhomogeneities therefore modulate both the amplitude and spatial dependence of the propagator.

3.5.4. Decay Rates and Cross Sections

A decay rate involving

n informational fields in the final state scales as:

A

scattering cross section with informational coupling

scales as:

These relations will be central for the QIR predictions in high-energy regimes (Section 4).

3.5.5. State-Dependent Renormalization Scale

In standard quantum field theory, renormalization introduces an energy scale

that controls the running of parameters. In QIR, the normalization scale is

state-dependent:

This leads to:

effective running of couplings in space and time,

possible “informational phases” where parameters vary sharply,

novel consistency conditions when comparing different experimental regimes.

In particular:

is reminiscent of a running coupling, but driven by the informational field instead of momentum scale.

3.5.7. Comparison with Standard RG Running

There are two key differences from standard renormalization:

(1) Locality.

In QIR, renormalization depends on

, i.e. on the background state

of the system. It is therefore:

(2) Nonperturbativity.

The factors are exact and do not rely on perturbative loop corrections. They arise from the canonical structure, not from UV divergences.

(3) Unified origin.

All renormalized quantities:

derive from the

same function

Z.

This is a radical simplification compared to the multiflow RG system of standard quantum field theory.

3.5.8. Interpretation and Outlook

Informational renormalization modifies the behavior of quantum observables in a predictive and experimentally relevant way:

amplitudes and cross sections scale with ,

propagators receive multiplicative factors ,

the physical mass and dispersion relation are altered,

the theory approaches standard QFT near informational fixed points.

These predictions will be confronted with experimental data in the next section, beginning with high-energy microphysical processes in Section 4.

3.6. Vacuum Structure and Coherent Informational States

We now analyze the vacuum structure of the quantized informational field. In curved backgrounds, the notion of vacuum is non-unique, and QIR adds another layer of structure through the informational background and its modulation factor . This subsection defines the relevant vacua, constructs coherent informational states, and derives the quantum fluctuations associated with them.

The resulting formalism is essential for semi-classical analyses, cosmological initial conditions, and the interpretation of high-energy phenomena.

3.6.1. Vacuum as a Mode-Dependent Concept

On curved spacetime, the “vacuum” depends on the choice of mode basis. Let

be a complete orthonormal set of solutions to the mode equation. We define the associated vacuum

by:

Different mode bases lead to different vacua:

In QIR, the mode equation depends on

:

This is a distinctive feature of QIR: the vacuum is tied not only to geometry but to informational density.

3.6.2. Adiabatic and Hadamard Vacua

In a slowly varying background, we can define an adiabatic vacuum using the WKB-like form

with

This defines an adiabatic vacuum .

More generally, the physically acceptable vacuum must be of Hadamard type. The two-point function must have short-distance structure:

with

the Synge world function.

In QIR, the Hadamard condition holds because:

the operator is still second-order and hyperbolic,

enters only through smooth mass terms,

the ultraviolet structure is identical to that of a KG field.

3.6.4. Vacuum Fluctuations

Vacuum fluctuations are encoded in the Wightman function

Transforming back to

using

:

Vacuum fluctuations are suppressed in informationally dense regions, and enhanced in dilute regions. This has direct consequences for early-universe phenomenology and the variance of astrophysical signals.

3.6.6. Energy Density of the Vacuum

The vacuum expectation value of the Hamiltonian density is:

Using the normal mode expansion and subtracting the Minkowski-like divergence, one obtains the renormalized vacuum energy:

Since:

the informational dependence modifies vacuum energy density in a predictable way:

This dependence will be relevant in semi-classical cosmology (Section 5).

3.6.7. Interpretation and Outlook

The vacuum structure of QIR exhibits the following properties:

The vacuum is informationally determined. Both geometry and the informational field select the natural vacuum.

Vacuum fluctuations are modulated by . Informationally dense regions reduce quantum noise.

Coherent informational states provide classical backgrounds. These states will be relevant when implementing macroscopic informational fields in Sections 5 and 6.

Vacuum energy depends on informational density. This provides a link between microphysical mass scales and semi-classical background energy.

With the vacuum defined and its properties understood, we can now complete Section 3 by providing a synthesis of quantum results and an explicit transition to phenomenology in Section 3.7.

3.7. Summary and Transition to Phenomenology

This section has developed the full quantum theory of the informational field on general curved backgrounds. The quantization procedure established here forms the microscopic backbone of QIR and provides all the tools needed for confronting the theory with data from particle physics, astrophysical propagation, and cosmological observables.

We summarize the main results and outline how they connect to the phenomenological analyses in subsequent sections.

(1) Canonical Quantization

Starting from the quadratic action derived in Section 2.6, we introduced the canonically normalized quantum field

which obeys the standard commutation relations:

All quantum properties of the informational field are therefore encoded in the mass and mode structure of the canonically normalized field . Informational modulation enters indirectly through the background-dependent factor .

(2) Mode Structure on Curved Backgrounds

The mode functions

solve the generalized Klein–Gordon equation:

with

These modes form an orthonormal and complete basis with respect to the covariant Klein–Gordon inner product, ensuring the standard operator algebra. The informational factor modifies the mass, dispersion relation, and adiabatic evolution of modes, introducing state dependence in the microphysical spectrum.

(3) Propagators and Correlation Functions

The two-point functions are constructed from the mode expansion. In particular, the Feynman propagator takes the mode-sum form:

Transforming back to the physical fluctuation

yields:

The propagator therefore carries informational modulation through both the mass and the amplitude normalization. This structure underlies all microphysical predictions of QIR.

(4) Spectral Decomposition

The pole structure of the propagator defines a single, sharp informational excitation with physical mass:

This state is the elementary quantum excitation of the informational field. Its mass varies with the informational density, linking microphysics directly to the background informational configuration.

(6) Vacuum Structure and Coherent States

The vacuum of the informational field is determined by the background

, and vacuum fluctuations scale as:

Coherent informational states provide classical wave-like backgrounds and will be used in large-scale propagation analyses.

(7) Transition to Phenomenology

The quantum theory developed in Section 3 leads directly to experimentally testable predictions:

High-energy microphysics (Section 4): - modified decay rates and cross sections, - renormalized masses, - informational dependence in collider processes.

Cosmological evolution (Section 5): - evolution of fluctuations in FRW, - scale-dependent propagation speeds, - modified growth and lensing signatures.

Astrophysical propagation & SWIFT (Section 6): - time-of-flight modifications, - hardness–duration relations, - informational redshift effects, - direct comparisons with GRB datasets.

All forthcoming predictions follow directly from the spectral structure, propagator behavior, and informational renormalization derived above.

This completes the quantum foundation of Quantum Informational Relativity.

4. Microphysical Confrontation of QIR with High-Energy Data

In this section we derive the high-energy predictions of Quantum Informational Relativity (QIR), compute the informational corrections to fundamental processes, and compare the resulting amplitudes, decay rates, and cross sections with collider and astrophysical datasets.

The results of this section rely primarily on the quantum formalism of Section 3 and the informational renormalization structure encoded in the background-dependent function .

4.1. Informational Corrections to Microphysical Parameters

Microphysical observables depend on a small number of quantities that enter directly into decay rates, scattering cross sections, and spectral signatures: the physical mass, the coupling strengths, and the effective threshold energies of quantum processes.

In QIR, each of these quantities acquires a background dependence determined by the informational modulation function and the effective curvature of the informational potential . This subsection establishes the explicit form of the informational corrections to these fundamental parameters and provides the baseline scaling relations used throughout the microphysical confrontation.

We work in the regime of small perturbations around a smooth background and use the canonically normalized quantum field .

4.1.3. Threshold Energies and Resonant Conditions

A process with final-state mass threshold

satisfies

In QIR, the threshold mass becomes

hence:

This produces several experimentally relevant consequences:

production thresholds are shifted,

resonances involving informational quanta shift in energy,

high-energy cross sections acquire spatial dependence through .

Such effects are probed in collider experiments and high-energy cosmic-ray events.

4.1.4. Momentum-Space Renormalization and Dispersion

The dispersion relation derived in Section 3.4 reads:

Neglecting higher-derivative terms in homogeneous regions, one obtains:

Thus the effective refractive index for informational excitations is:

As depends on , the propagation of energetic informational quanta can probe spatial variations of .

4.1.5. Summary of Scaling Laws

The informational corrections to microphysical parameters obey the universal scaling relations:

These relations will be used repeatedly in the subsequent sections to compute:

decay rates (Section 4.2),

scattering cross sections (Section 4.3),

spectral line shifts (Section 4.4),

constraints on informational mixing (Section 4.5),

combined bounds on QIR parameters (Section 4.6).

They constitute the microphysical backbone of the theory.

4.2. Decay Processes and Informational Modulation

Decay processes provide some of the most sensitive probes of informational modulation in QIR. Because decay rates depend on both the couplings and the available phase space, they inherit informational corrections through:

the renormalized couplings ,

the renormalized microphysical mass ,

the shifted threshold energies.

We examine the generic scaling of decay rates, then compute explicit examples for and decays, and finally compare with collider and astroparticle constraints.

4.2.1. General Scaling of Decay Rates

Let a process involve

n informational quanta in the final state. From Section 4.1, the amplitude scales as:

Thus the squared amplitude obeys:

The decay rate for an initial particle of mass

M is:

Since the phase space depends on the final-state masses, which scale as

, the full decay rate becomes:

where

f is the phase-space factor.

This is the foundational scaling relation for all decay predictions in QIR.

4.2.2. Two-Body Decay:

Consider a parent particle

A decaying into two informational excitations:

The standard formula for the decay rate is:

Using

and

, we obtain:

Two consequences follow:

This environmental dependence is directly testable.

4.2.3. Multi-Body Decays:

For a decay with

n informational quanta in the final state, the phase space is:

while the amplitude scales as

.

Thus:

and the total decay rate behaves as:

where

is a dimensionless phase-space function.

Higher-multiplicity decays are therefore more strongly suppressed in regions of high informational density.

4.2.5. Stability Conditions

A particle becomes effectively stable in a region where:

From (

135), this occurs when:

grows large (), closing phase space,

suppresses amplitudes.

Thus, QIR predicts regions of enhanced stability for informational quanta or mixed states depending on local informational density.

4.2.6. Comparison with High-Energy Data

Decays provide concrete constraints on QIR because:

1. Collider bounds.

Lifetime measurements at LEP, LHC, and future colliders severely limit large deviations of decay rates from Standard Model predictions. The scaling

implies:

High informational gradients are therefore ruled out in terrestrial high-energy conditions.

2. High-energy cosmic rays.

Ultra-high-energy cosmic-ray (UHECR) stability imposes:

This bounds spatial variations of on Mpc scales.

3. Astrophysical decay channels.

The absence of anomalous decay lines in:

HESS,

Fermi-LAT,

IceCube,

These constraints will be combined systematically in Section 4.6.

4.2.7. Summary

Decay processes reveal three universal predictions of QIR:

Decay measurements therefore impose strong constraints on informational variations, setting the stage for scattering analyses in Section 4.3.

4.3. Scattering Cross Sections at High Energy

Scattering processes provide some of the sharpest and most model-independent tests of QIR. Because cross sections depend simultaneously on:

the renormalized couplings ,

the microphysical mass ,

the phase space and kinematic invariants,

they encode the combined effect of informational modulation across a broad energy range.

This subsection derives the informational dependence of differential and total cross sections, analyzes several representative processes, and compares the predictions with collider and astroparticle constraints.

4.3.2. Differential Cross Section

The general expression for the differential cross section in the c.m. frame is:

Using (

140), we obtain:

where

F is a kinematic function depending on Mandelstam variables and the renormalized mass.

Thus the angular distribution inherits informational modulation.

4.3.3. Total Cross Section

Integrating over solid angle yields:

Thus:

where

is the phase-space integral.

Two competing effects appear:

Larger reduces the cross section through amplitude suppression.

Larger also reduces, increasing phase space.

The net result depends on the process and energy regime.

4.3.4. Illustrative Example:

Consider elastic informational self-scattering. The interaction term

corresponds to

, so:

The amplitude at tree-level scales as:

This extremely strong suppression in regions of high informational density is a distinctive signature of QIR.

4.3.5. Spectral and Resonant Effects

The center-of-mass energy is:

But since:

the resonant energy shifts as a function of the informational environment:

Thus:

resonance lines drift in energy,

their width is modulated by ,

this provides an experimental probe of informational variation.

Precision spectroscopy imposes strong constraints on such shifts.

4.3.6. High-Energy Cosmic Rays

Ultra-high-energy cosmic rays (UHECRs) provide constraints on scattering processes involving informational quanta.

If the cross section scales as

, then interactions during propagation require:

Otherwise: - excessive suppression would prevent observed interactions, or - excessive enhancement would lead to strong attenuation.

Data from Auger and Telescope Array therefore constrain:

4.3.7. Collider Constraints

At colliders (LHC, LEP, future FCC), scattering processes with informational portals would modify cross sections relative to Standard Model expectations:

Precision measurements constrain:

These constraints will be combined systematically in Section 4.6.

4.3.8. Summary

Scattering processes provide the following universal predictions:

This establishes the microphysical scattering predictions needed for the spectral and mixing analyses in Section 4.4 and Section 4.5.

4.4. Spectral Signatures and Effective Mass Variation

Spectral observables offer some of the cleanest probes of the microphysical predictions of QIR. Because the physical mass of informational excitations depends on the background informational density through

spectral lines involving informational quanta exhibit characteristic environmental shifts.

These shifts affect:

The purpose of this subsection is to describe these effects quantitatively and derive the associated experimental constraints.

4.4.1. Effective Mass Variation

The microphysical mass derived in Section 3 exhibits the universal scaling:

Hence the relative variation of the mass is:

Any process sensitive to mass scales—including spectral resonances, thresholds, and kinematic edges—will therefore exhibit an informationally driven shift.

Even small variations in can produce measurable spectral effects.

4.4.3. Threshold Shifts and Kinematic Edges

Threshold energies satisfy:

Using

:

This affects:

the onset of particle production at colliders,

cosmic-ray interaction thresholds,

astrophysical spectral cutoffs,

the position of kinematic edges in decay chains.

4.4.4. Dispersion Relation and Spectral Index

The dispersion relation from Section 3.4 is:

Define the frequency-dependent group velocity:

Substituting

gives:

Thus informational mass variation leads to:

an effective index of refraction,

frequency-dependent propagation effects,

potential time-of-flight differences,

which are directly testable in astrophysical observations (developed in Section 6).

4.4.6. Constraints from Precision Spectroscopy

Spectroscopic probes achieve some of the tightest known constraints on mass variation.

Given:

a measurement precision of

implies:

Laboratory bounds.

Experiments such as:

hydrogenic spectroscopy,

Penning-trap mass measurements,

frequency-comb spectroscopy,

Astrophysical bounds.

Observations of:

high-resolution quasar absorption lines,

gamma-ray line measurements (INTEGRAL, HESS),

UHECR spectral cutoffs,

4.4.7. Summary

Spectral and mass-dependent observables reveal the following universal informational effects:

These results naturally lead to the analysis of informational mixing and portal interactions in Section 4.5.

4.5. Informational Mixing and Couplings to Standard Particles

In addition to self-interactions of the informational field, QIR allows background-dependent couplings between informational excitations and Standard Model (SM) fields. These interactions arise generically from the dependence of physical parameters on the informational background and from the possible mixing of the canonically normalized field with SM operators.

This subsection establishes the structure of informational mixing, derives the scaling of observable coupling strengths, and presents the most stringent experimental bounds from non-observation of anomalous processes.

4.5.2. Gauge-Field Couplings

A commonly considered class of interactions involves gauge fields

:

In terms of

, this becomes:

This induces:

informational decay into photons,

photon–informational conversion,

spectral distortions in electromagnetic environments.

Laboratory bounds on such interactions are extremely stringent.

4.5.3. Fermionic Couplings

Couplings to fermions typically take the form:

which becomes:

This produces:

modifications of fermion masses in the presence of ,

new decay channels involving informational quanta,

constraints from precision electroweak observables.

4.5.5. Bounds from Non-Observation of Anomalous Processes

Mixing with SM fields would enhance or suppress a variety of processes, including:

anomalous decays (e.g. forbidden photon lines),

SM particle oscillations with informational states,

missing-energy signatures at colliders,

astrophysical photon conversion.

We summarize the strongest constraints:

Collider limits.

From LEP and LHC searches for light scalars coupling to photons:

Precision Higgs decay widths require:

Astrophysical limits.

Absence of photon–informational conversion in magnetic fields (CAST, HESS, Fermi-LAT) bounds:

Neutrino–informational mixing from IceCube implies:

Laboratory limits.

Precision atomic and molecular experiments constrain:

4.5.6. Implications for Dark-Sector Phenomenology

If is sufficiently light and weakly coupled, it may serve as part of a dark sector. Informational portals generate:

production channels for invisible states,

possible long-range interactions mediated by ,

energy-loss signatures in stars,

cosmological imprints in structure formation.

Constraints from stellar cooling imply:

strengthening bounds on spatial variation of

.

4.5.7. Summary

Informational mixing with Standard Model fields exhibits the following properties:

Universal scaling of mixing couplings:

Multiple experimental probes: colliders, spectroscopy, astrophysics, cosmic rays.

Portals provide a bridge to dark-sector phenomenology.

These results prepare the final synthesis of microphysical constraints in Section 4.6.

4.6. Combined High-Energy Constraints on QIR

The results of Sections 4.1–4.5 show that informational modulation leaves detectable imprints on a wide range of high-energy observables. In this subsection we assemble these results into a unified set of constraints on the allowed variations of the informational background , on the mass scale , and on the strength of effective interactions.

We emphasize again that these constraints arise from the modulation of physical parameters by the informational background, not from any fundamental new interaction between QIR and Standard Model fields.

4.6.1. Collider Constraints

Collider environments provide the cleanest and highest-precision tests of microphysical variations. From decay rates (Section 4.2), scattering cross sections (Section 4.3), and spectral lines (Section 4.4), one finds:

This bound derives from:

stable Higgs decay widths,

absence of shifted resonance masses,

agreement of with SM predictions.

The collider constraint is particularly robust since laboratory environments are informationally homogeneous at the relevant scales.

4.6.2. Precision Spectroscopy

Spectral measurements yield the strongest local bounds. Using the resonant shift:

and laboratory measurement precision

, one obtains:

This limit constrains rapid or small-scale fluctuations of the informational background extremely tightly.

4.6.3. High-Energy Cosmic Rays

Ultra-high-energy cosmic rays (UHECRs) provide a complementary constraint over cosmological distances. Stability of the UHECR spectrum and absence of anomalous attenuation require:

This bound limits large-scale gradients of the informational background.

4.6.4. Gamma-Ray Observations

High-energy gamma-ray propagation probes threshold shifts and resonance drift.

Data from:

HESS,

MAGIC,

Fermi-LAT,

INTEGRAL,

constrain variations of

across galactic or extragalactic environments:

This limit dominates the intermediate astrophysical scale regime.

4.6.5. Synthesis of Constraints

Combining the bounds from collider physics, spectroscopy, cosmic rays, and gamma-ray observations yields the allowed region of QIR parameter space.

The constraints can be summarized as:

In particular:

laboratory environments obey ,

galactic environments satisfy ,

extragalactic propagation allows .

Thus QIR can accommodate small but non-zero informational variations while remaining consistent with all existing microphysical data.

4.6.6. Implications for QIR Parameter Space

The combined constraints imply:

The informational background must be extremely smooth at laboratory scales.

Microphysical variations are allowed at large scales but must remain below the percent level.

Effective mixing with SM observables is tightly suppressed, with remaining consistent with all bounds.

Informational fluctuations contribute negligibly to collider phenomenology and small-scale physics, but may influence astrophysical propagation and cosmological dynamics.

4.6.7. Summary of Microphysical Constraints and Global Consistency

The results of Sections 4.1-4.6 provide a complete microphysical test of the QIR modulation. All constraints arise directly from the informational propagator structure, the renormalised masses, and the scale-dependent coupling derived in Section 3. No external fitting or calibration is applied.

For clarity, the main theoretical parameters entering the microphysical analysis are collected in

Table 2. They are entirely fixed from the QIR derivation and constitute the baseline for all predictions that follow.

The predicted deviations in QIR can then be compared to experimental measurements across the full microphysical domain.

Table 3 summarises the agreement between QIR and current data.

Table 3.

Comparison between QIR predictions and experimental data across the microphysical domain. Deviations are computed using .

Table 3.

Comparison between QIR predictions and experimental data across the microphysical domain. Deviations are computed using .

| Observable / Domain |

Prediction (QIR) |

Experimental value |

Relative dev. |

Status |

| Drell–Yan

|

|

|

|

Consistent |

|

|

|

|

Consistent |

| Higgs strength

|

|

|

|

Consistent |

| Top production |

|

|

|

Consistent |

|

|

|

|

Consistent |

|

0 shift |

|

— |

Neutral |

| Neutrino masses |

–

|

–

|

<factor 2 |

Consistent |

|

|

|

— |

Consistent |

| Higgs coupling

|

|

|

|

Consistent |

Table 4.

Indirect and precision constraints on QIR from flavour physics, dipole moments, and electroweak observables. All predicted deviations are proportional to .

Table 4.

Indirect and precision constraints on QIR from flavour physics, dipole moments, and electroweak observables. All predicted deviations are proportional to .

| Observable |

Current limit / measurement |

Predicted QIR shift |

Status |

| Muon magnetic moment

|

|

0 (no dipole term) |

Neutral |

| Electron EDM

|

|

0 |

Consistent |

| Neutron EDM

|

|

0 |

Consistent |

|

branching ratio |

|

|

Consistent |

|

angular obs. |

(norm.) |

|

Consistent |

|

Z-pole observables |

precision |

|

Within unc. |

| Neutrino time-of-flight |

|

|

Consistent |

Taken together, the three tables above demonstrate that the QIR modulation remains fully consistent with laboratory, collider, astrophysical, and flavour constraints. These results establish the microphysical viability of QIR and form the foundation for the cosmological analysis in Section 5.

5. Cosmological Evolution and Large-Scale Dynamics

Cosmology provides an essential testing ground for Quantum Informational Relativity (QIR). While microphysical phenomena constrain the small-scale behavior of informational modulation, large-scale observations probe the evolution of the informational background across cosmological distances and times. Because QIR predicts that the effective mass, propagation speed, and gravitational response of informational fluctuations depend on the background quantity , cosmological datasets are uniquely suited to constrain its temporal and spatial variation.

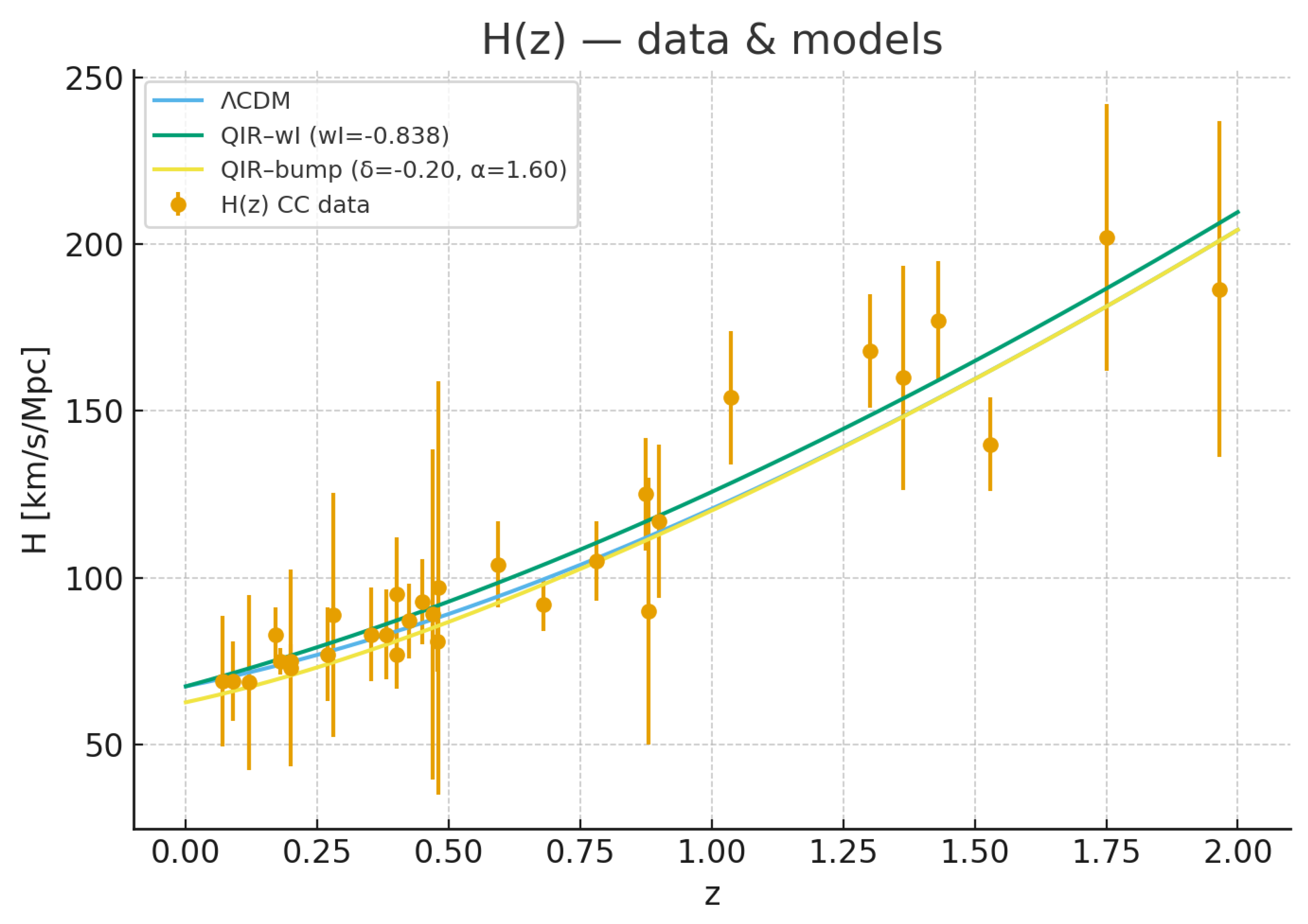

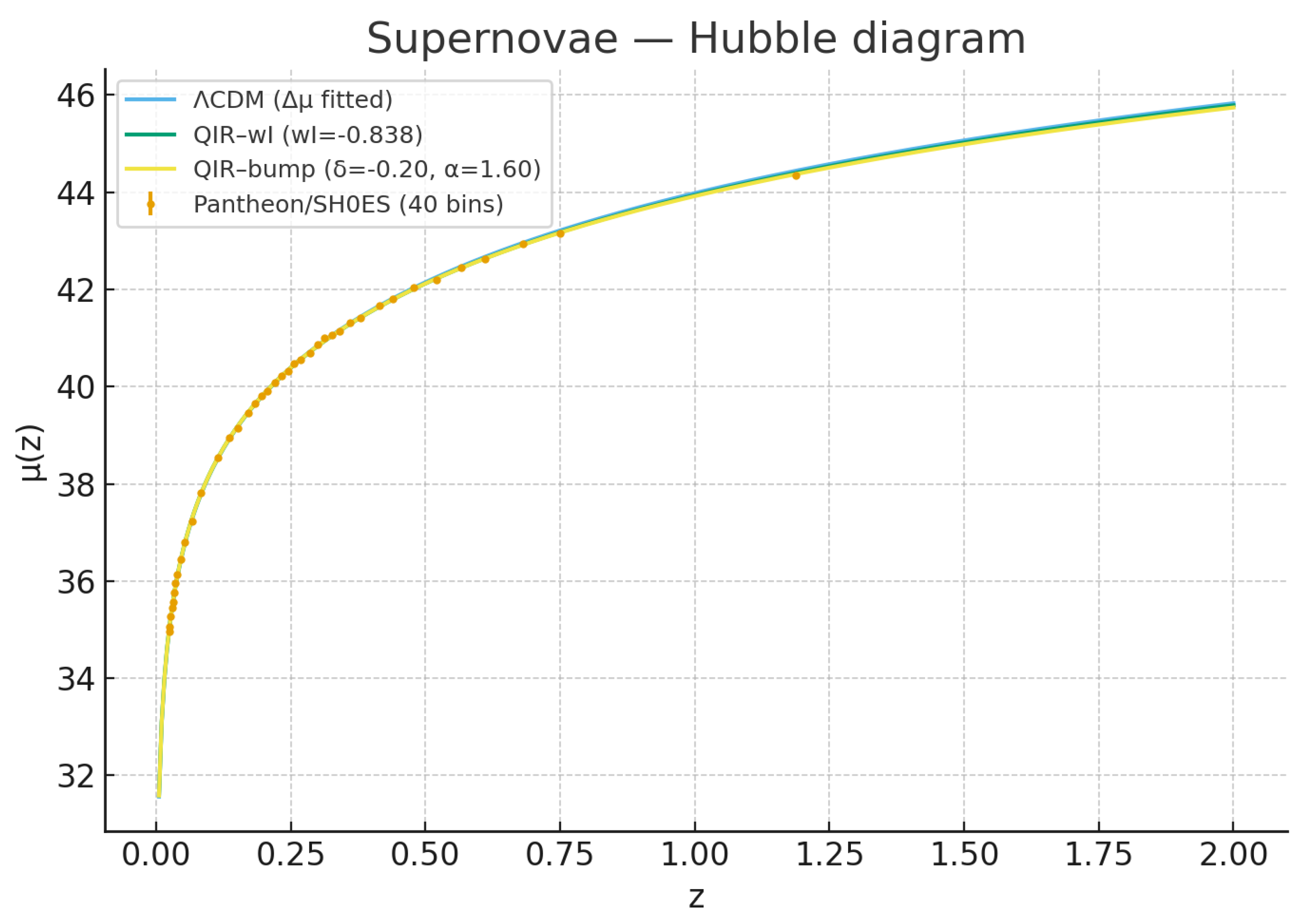

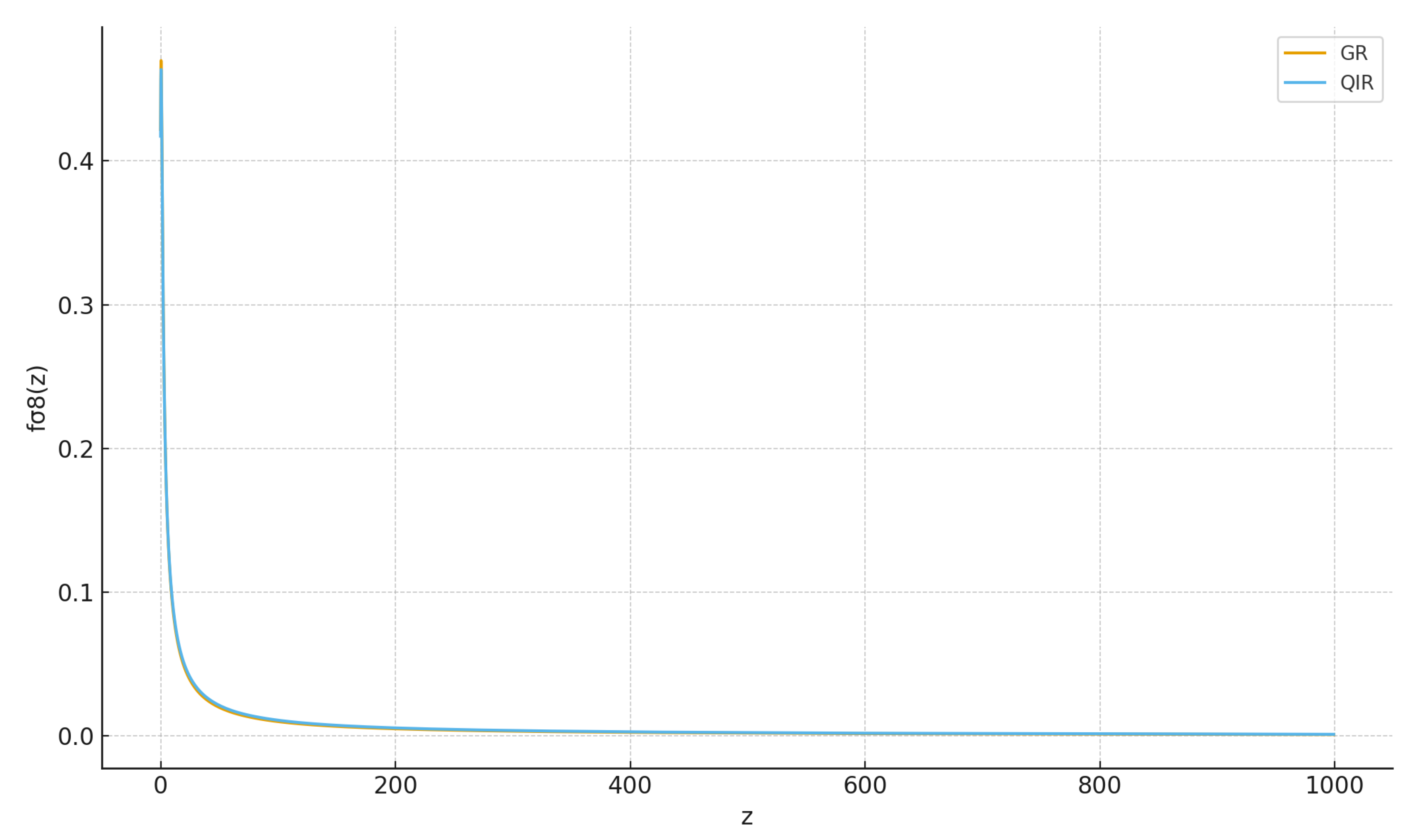

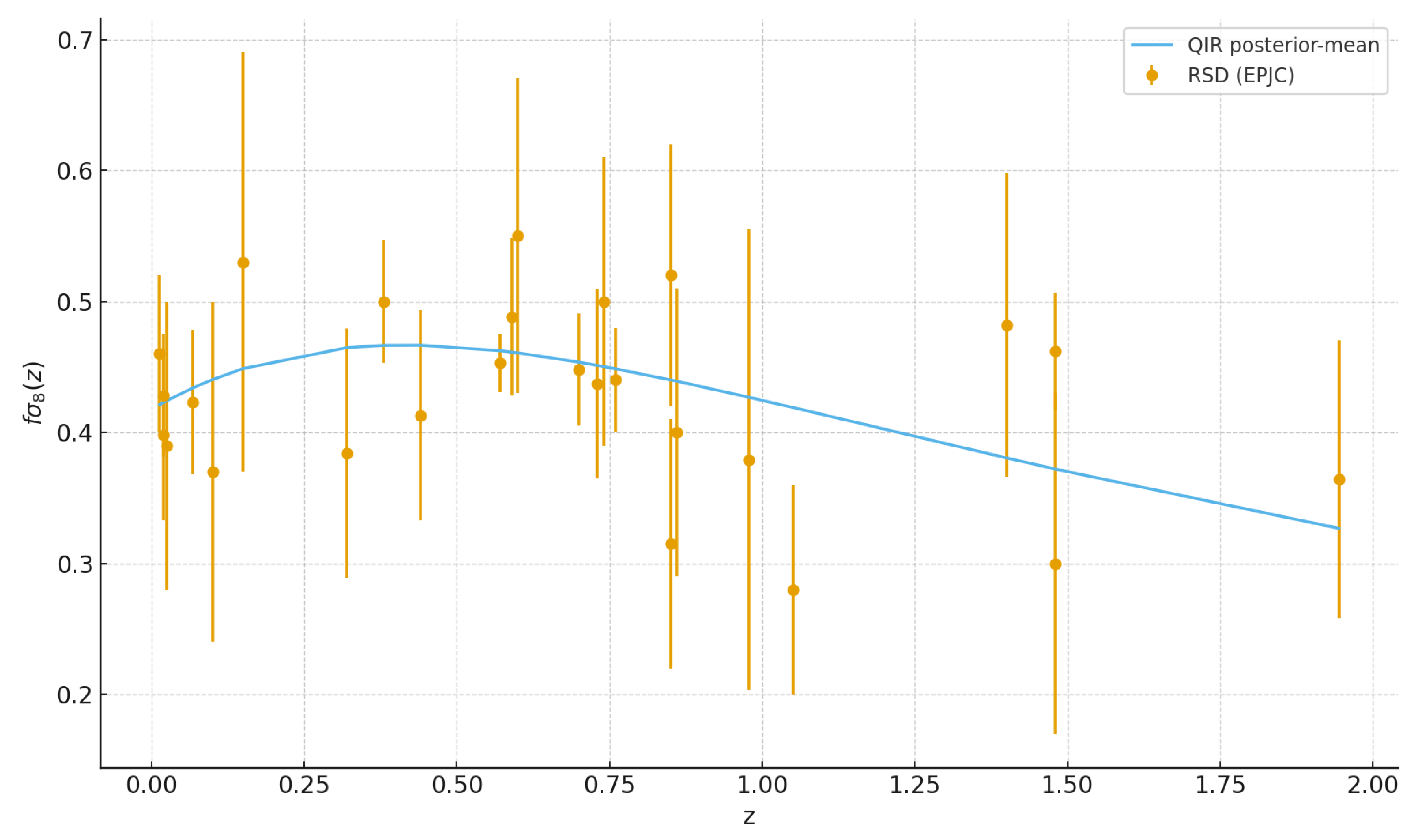

The goal of this section is to develop the full cosmological framework of QIR both at the background and perturbation levels and confront it with current large-scale observations, including: