1. Introduction

Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) is a highly stable tobamovirus that was first detected in Jordan in 2015 [

1] and poses a significant threat to solanaceous crops such as tomato and pepper [

2,

3]. In Mexico, this virus is widely distributed and was first reported in Michoacán in 2018 [

4]. It can persist for prolonged periods on various surfaces, including clothing, tools, and greenhouse structures, thus facilitating mechanical transmission and rapid spread in protected cultivation systems [

5,

6]. Skelton et al. (2023) [

7] demonstrated that ToBRFV remains viable on contaminated surfaces for at least seven days and, in some cases, for over six months. Notably, common crop management activities such as transplanting, pruning, and trellising are often performed manually, and ToBRFV virions have been shown to survive for more than two hours on hands and gloves, further emphasizing the importance of hygiene measures [

7].

In this context, the control of plant virus transmission using chemical disinfectants is influenced by a multifaceted interplay between the physicochemical properties of the disinfectant, the biological characteristics of the virus, the type of contaminated surface, and environmental factors such as temperature and relative humidity [

8]. Effective disinfectants must combine high virucidal activity with safety for humans, animals, and the environment, particularly when water serves as the primary application medium [

9]. In laboratory evaluations, virucidal efficacy is commonly assessed through suspension tests, in which the virus is directly mixed with the disinfectant, or carrier tests, which more accurately mimic field conditions by applying the virus to surfaces prior to disinfection [

10]. Although suspension tests are simpler and more widely used, carrier tests offer a more realistic assessment of performance, as viruses dried on surfaces are considerably more resistant to inactivation [

11]. Furthermore, the presence of organic or inorganic debris can significantly diminish disinfectant efficacy, underscoring the need for robust formulations that maintain effectiveness under field-relevant conditions [

12].

Effective disinfectants for agricultural use should satisfy several essential criteria: they must be affordable, readily available, and fast-acting, ideally achieving their effect within one minute, while remaining safe for humans, plants, and the environment. They must also be legally approved, stable under greenhouse conditions, and exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity [

13,

14,

15]. A

3-log₁₀ reduction in viral titer within a short contact time is generally recognized as the benchmark for virucidal efficacy [

11]. The type and quality of the target surface (whether porous or non-porous, hydrophilic or hydrophobic, hard or soft) are critical factors in selecting an appropriate disinfection method. In addition, the physical dimensions and structural complexity of equipment or facilities can significantly influence the efficiency of decontamination [

12]. Methods such as fogging, fumigation, electrostatic spraying, and ultraviolet light remain important tools for surface and equipment disinfection, emphasizing the need for tailored, physics-informed approaches to virus mitigation in agricultural environments [

16].

Efficient management of ToBRFV requires the integration of multiple phytosanitary measures within protected cropping systems. Key strategies include the use of certified propagation material, the implementation of rapid diagnostic tools, and the prompt removal and destruction of infected plants [

17]. In regions where ToBRFV has been detected, preventing reinfection in subsequent production cycles is essential. This can be achieved through disinfection of greenhouse structures, particularly plastic surfaces, and all previously used tools. Furthermore, continuous disinfection of hands and cutting implements throughout the vegetative growth phase is critical to minimizing mechanical transmission during routine cultural operations. [

7,

18,

19].

Given the persistence of ToBRFV on diverse surfaces and its ease of mechanical transmission, identifying disinfection strategies that are both effective and practical under greenhouse conditions is a priority for disease management. While several studies have assessed the virucidal activity of different chemical agents [

20,

21,

22], there is limited information on how efficacy is influenced by the type of contaminated surface, the application method, and the specific formulations used under conditions that closely mimic commercial tomato production. Reported complete inactivation has been achieved with 1% Virocid, 2% Virkon S, 0.25% sodium hypochlorite (derived from 5% Clorox bleach), 2.5% trisodium phosphate, benzoic acid, glutaraldehyde, and quaternary ammonium compounds [

7,

10,

13]. Similarly, Chanda et al. (2021) [

14] demonstrated 90–100% inactivation using 0.5% lactoferrin, 2% Virocid, 10% Clorox, and Virkon S. However, certain compounds such as trisodium phosphate exhibit phytotoxic effects, which limit their use during routine crop handling in tomato and pepper cultivation [

13].

Most previous evaluations have relied on suspension or confrontation assays rather than carrier-based methods that more accurately simulate field conditions [

23,

24]. Furthermore, few studies have examined the impact of the application technique. Rodríguez-Díaz et al. (2022) [

25] found that spray application outperformed immersion, highlighting the role of delivery method in determining disinfection efficacy. Considering the virus’s stability and the need for products safe for both inanimate surfaces and human skin, it is essential to determine appropriate concentrations and application methods that ensure effective virus inactivation while maintaining user and crop safety.

Therefore, this study aimed to assess the effectiveness of selected disinfectants in inactivating ToBRFV on greenhouse-relevant surfaces, including polyethylene film, pruning shears, and human hands, using both spray and immersion application methods. The most promising treatments were subsequently evaluated for their ability to prevent mechanical transmission to tomato plants, providing a framework for integrating sanitation into ToBRFV management strategies. Notably, this work challenges the prevailing assumption that disinfectant concentration is the primary determinant of virucidal success; instead, it highlights that surface type and application method play a critical role in whether virions are fully inactivated or remain infective. Furthermore, it demonstrates that even highly potent disinfectants such as glutaraldehyde and advanced quaternary ammonium compounds require clean, non-porous surfaces to achieve optimal efficacy, emphasizing the importance of tailoring disinfection protocols to the physical and biological context of the greenhouse operations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental and Computational Workflow for Lesion and Disease Severity Analysis

The workflow used to quantify and statistically analyze leaf lesion severity is summarized in

Figure 1.

The experiments were conducted in the glasshouse facilities of the Department of Agricultural Parasitology at the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo, in Mexico. The inoculum of ToBRFV used for artificial contamination was obtained from the phytopathogenic virus collection of the Graduate Program in Plant Protection. This isolate corresponds to a Mexican ToBRFV strain deposited in the NCBI database under the accession BankIt2895689; PQ628197 [

26]. The computational workflow used to evaluate lesion and disease severity integrates digital image processing, quantitative lesion area extraction, and statistical modeling to assess treatment effects. The overall design ensures reproducibility and comparability across treatments. All analysis scripts are available at this repository

https://github.com/kap8416/DisinfectantsToBRFV.

2.2. Reactivation and Maintenance of the Inoculum Source

Fifteen healthy tomato plants (

Solanum lycopersicum, cv. Saladette) were mechanically inoculated with sap from the ToBRFV-positive source. Thirty days post-inoculation (dpi), systemic infection was confirmed by the development of characteristic viral symptoms, including mosaic mottling, leaf enation, and filiform leaf morphology. To verify ToBRFV infection, symptomatic leaves and shoots were collected for total RNA extraction using the TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality and concentration were assessed with a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Viral detection was performed by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) using specific primers ToBRFV-FMX (5′-AACCAGAGTCTTCCTATACTCGGAA-3′) and ToBRFV-RMX (5′-CTCWCCATCTCTTAATAATCTCCT-3′), under amplification conditions described by Cambrón-Crisantos

et al. (2019) [

4].

2.3. Bioassay Design for Evaluating Disinfectant Efficacy Against ToBRFV

The experimental unit consisted of a fully developed

Nicotiana rustica leaf, within which a 36 cm

2 square area was delimited for inoculation. Each treatment was replicated three times. The disinfectant products evaluated included glutaraldehyde (Glutasan 50®), hydrogen peroxide (Anglosil®), fourth-generation quaternary ammonium compounds (Anglosan Cl®), fifth-generation quaternary ammonium compounds (Sany Green®), soap formulation composed of an ethoxylated nonionic surfactant, organic polyglucoside detergent, and sodium hydroxide (Bio Any Gel®), powdered milk, a mock-inoculated healthy control, and a mock-treated infected control. Detailed information on treatment concentrations and formulations is provided in Supplemental

Table S1. Three types of surfaces were tested for disinfection efficacy: greenhouse polyethylene film, pruning shears, and human hands, the latter evaluated only with low concentrations of quaternary ammonium compounds and powdered milk due to safety considerations. Two application methods were assessed for hands and pruning shears: spraying using a backpack sprayer and surface immersion (dipping). Greenhouse film was treated exclusively by spraying (

Figure 2).

2.4. Quantification of Leaf Lesion Severity Using Image Processing

The severity of leaf lesions for each treatment was quantified using the open-source software QuPath (version 0.6.0) [

27] and ImageJ [

28], both widely used tools for digital image analysis. QuPath was employed for pre-processing and lesion segmentation. This software is designed for bioimage analysis and includes a color deconvolution algorithm that digitally separates images into red, green, and blue (RGB) channels. Leaf images were first processed using the Brightfield H&E setting, a histological visualization method that enhances tissue contrast by rendering the background lighter and lesion-associated structures darker. Subsequently, a Hue filter was applied to isolate color tones independently of saturation and intensity, thereby reducing visual noise and flattening the image. This facilitated accurate segmentation of necrotic or chlorotic areas. Finally, the processed image was converted to grayscale to enhance contrast and streamline quantification of damaged regions. The grayscale images were then imported into ImageJ, which was used to calibrate spatial measurements by setting a scale in centimeters. ImageJ enables calculation of lesion area, distance measurements, and pixel-to-area conversion, allowing precise quantification of the infected leaf surface.

2.5. Descriptive Evaluation Prior to Model Fitting

A descriptive statistical analysis was first performed to identify patterns of virucidal performance across disinfectants, doses, surfaces, and application methods. For each treatment, lesion count and leaf damage severity were summarized using means, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals. These descriptive metrics enabled the identification of the most and least effective dose–method combinations prior to model-based inference. All calculations and visualizations were conducted in Python and R, using the pandas, numpy, and ggplot2 libraries. This descriptive evaluation provided the empirical foundation for subsequent inferential modeling.

2.6. Statistical Modeling of Surface–Method Interactions

Lesion count data were statistically evaluated to determine the effects of disinfectant formulation, surface type, and application method. Data exploration revealed overdispersion, leading to the use of a Negative Binomial Generalized Linear Model (NB-GLM) as the primary analytical framework. Model selection was based on residual diagnostics and Akaike Information Criterion, with the NB-GLM outperforming Poisson and Quasi-Poisson alternatives. The model included disinfectant, surface, and method as fixed effects, along with their pairwise interactions. Incidence Rate Ratios (IRRs) were calculated relative to the plastic–spray reference group to estimate the relative infection risk. Confidence intervals (95%) and Wald tests (p < 0.05) were used to assess significance. For disinfectants showing a monotonic response to concentration, a nonlinear Emax model was applied to characterize dose-dependent efficacy. Parameter estimation was performed using weighted least squares and Levenberg–Marquardt optimization, with model performance evaluated through residual analysis and AIC.

2.7. Bioassays to Assess the Efficacy of Disinfectants in Preventing Mechanical Transmission of ToBRFV to Tomato Plants

From the initial bioassay, the most effective disinfectant products and application methods were selected and tested for their ability to prevent the mechanical transmission of ToBRFV to tomato plants. As the inoculum source, five

Solanum lycopersicum (cv. Saladette) plants were mechanically inoculated with ToBRFV. After 25 dpi, systemic infection was confirmed by RNA extraction and RT-PCR, as described in

Section 2.1, along with the observation of characteristic symptoms. In parallel, tomato seedlings were grown under controlled greenhouse conditions, and once the first true leaf had developed, they were used for the bioassay. Each experimental unit consisted of a single tomato plant, and each treatment included eight replicates. The experiment followed a completely randomized design. The infected tomato plants served to contaminate the tested surfaces—pruning shears and human hands—through direct handling of infected tissues or by making cuts on symptomatic leaves and stems using the shears. Immediately after contamination, these surfaces were treated by spraying with the selected disinfectant formulations (Supplemental

Table S2). Following treatment, mechanical inoculation was performed on healthy tomato plants by either handling or cutting a cotyledon and one leaflet from a true leaf using the disinfected hands or pruning shears (

Figure 3). Plants were monitored every 24 hours to record symptom development, and infection was confirmed 25 dpi by RT-PCR, as previously described.

3. Results

3.1. Bioassays Reveal Surface and Method-Specific Differences in Disinfectant Efficacy

In commercial greenhouse tomato production, disinfection of metallic and plastic infrastructure prior to planting or transplanting is routinely conducted as a preventive phytosanitary measure, most commonly via surface spraying or micro-nebulization. Reflecting this industrial practice, spraying was selected as the application method for polyethylene greenhouse film. During crop management operations such as pruning, deleafing, and trellising, workers frequently handle plants with bare hands due to convenience and speed, rather than using protective gloves. Therefore, only disinfectant formulations deemed safe for direct skin contact at low concentrations were evaluated on human hands. Following application of each disinfectant to artificially contaminated surfaces, virions were collected using phosphate-buffered swabs and mechanically inoculated onto leaves of

Nicotiana rustica. Chlorotic local lesions developed between 5 and 7 dpi, depending on treatment. Lesions progressively became necrotic, and in some cases, merged to form larger necrotic patches. The number of observed lesions per treatment is detailed in

Table 1.

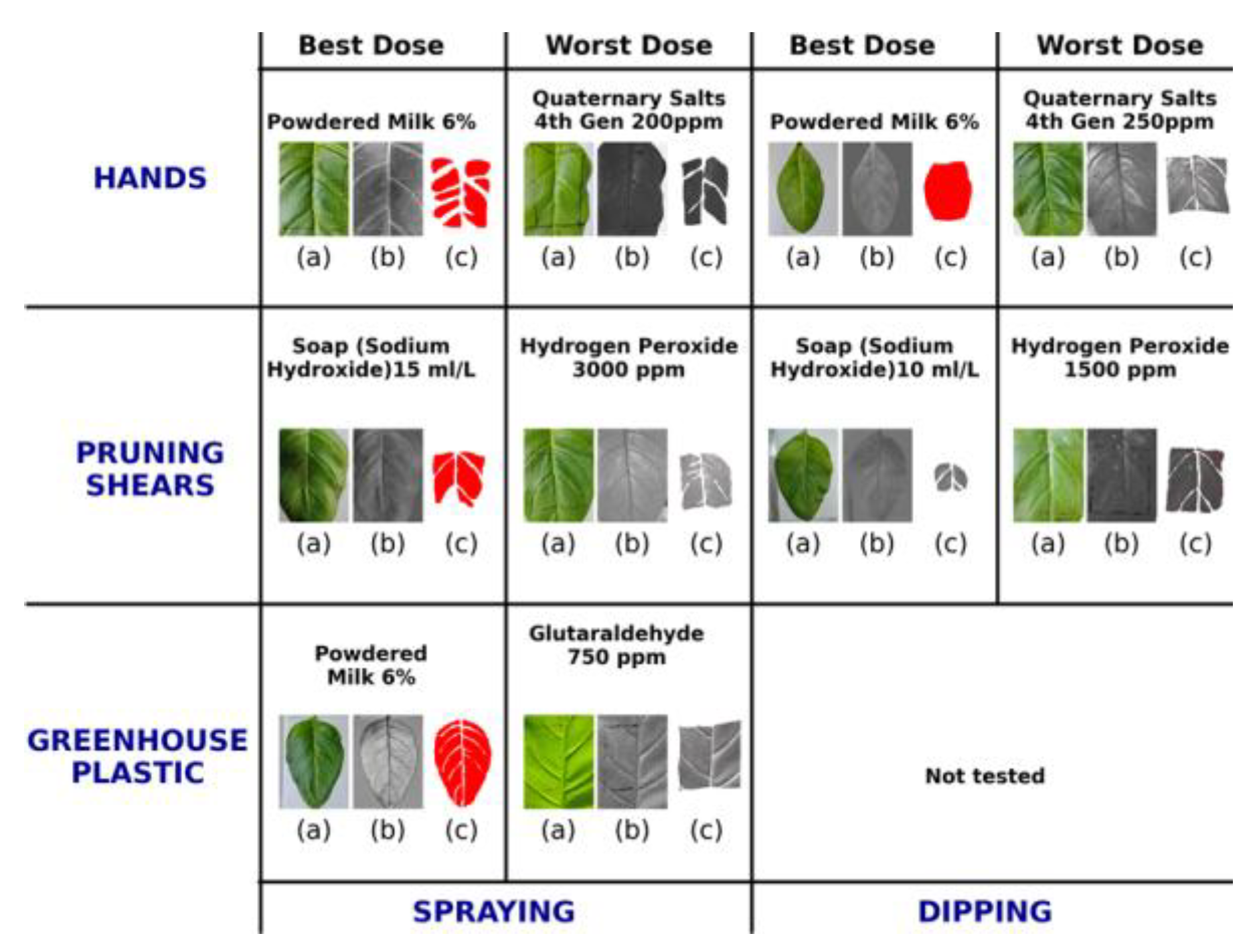

Digital image processing–based quantification of lesion severity (Supplemental

Figure S1) revealed substantial heterogeneity in both lesion number and total affected area across disinfectant formulations, surface types, and application methods. Polyethylene surfaces treated by spraying consistently displayed the lowest lesion counts, whereas pruning shears treated by dipping showed markedly higher residual infectivity, underscoring the strong modulatory effect of surface physicochemical properties on ToBRFV inactivation efficiency (

Figure 4). Additionally, lesion number and lesion area exhibited a positive, moderate, and statistically significant correlation (Spearman’s r ≈ 0.60), indicating that increases in the number of infection foci were accompanied by proportional increases in overall disease severity (Supplemental

Figure S2).

Overall, spraying was the most effective application method, consistently achieving the highest virion inactivation rates across all surface types. In contrast, pruning shears retained the largest number of infectious particles after treatment, confirming that metallic tools constitute a critical mechanical transmission risk and require stricter disinfection protocols [

29,

30]. Among the evaluated chemical disinfectants, fifth-generation quaternary ammonium compounds (5°QAS) showed the most consistent antiviral activity, reducing ToBRFV infectivity by approximately 85–97% across surfaces. Glutaraldehyde and hydrogen peroxide also exhibited strong but more variable efficacy depending on the surface type tested. Interestingly 6% powdered milk reached inactivation values as high as 96–99%, according to visual lesion counting. Similarly, soap (alkaline hydroxide formulation) reduced infectivity by up to 90–96%, but its effectiveness depended strongly on application surface and organic load. In contrast, fourth-generation (4°QAS) were moderately effective (22–66%) and less reliable under greenhouse-like conditions. These results indicate that chemical mode of action and disinfectant–surface interactions are more critical determinants of viral inactivation than concentration alone.

3.2. Quantitative and Dose-Dependent Evaluation of Disinfectant Efficacy Against ToBRFV

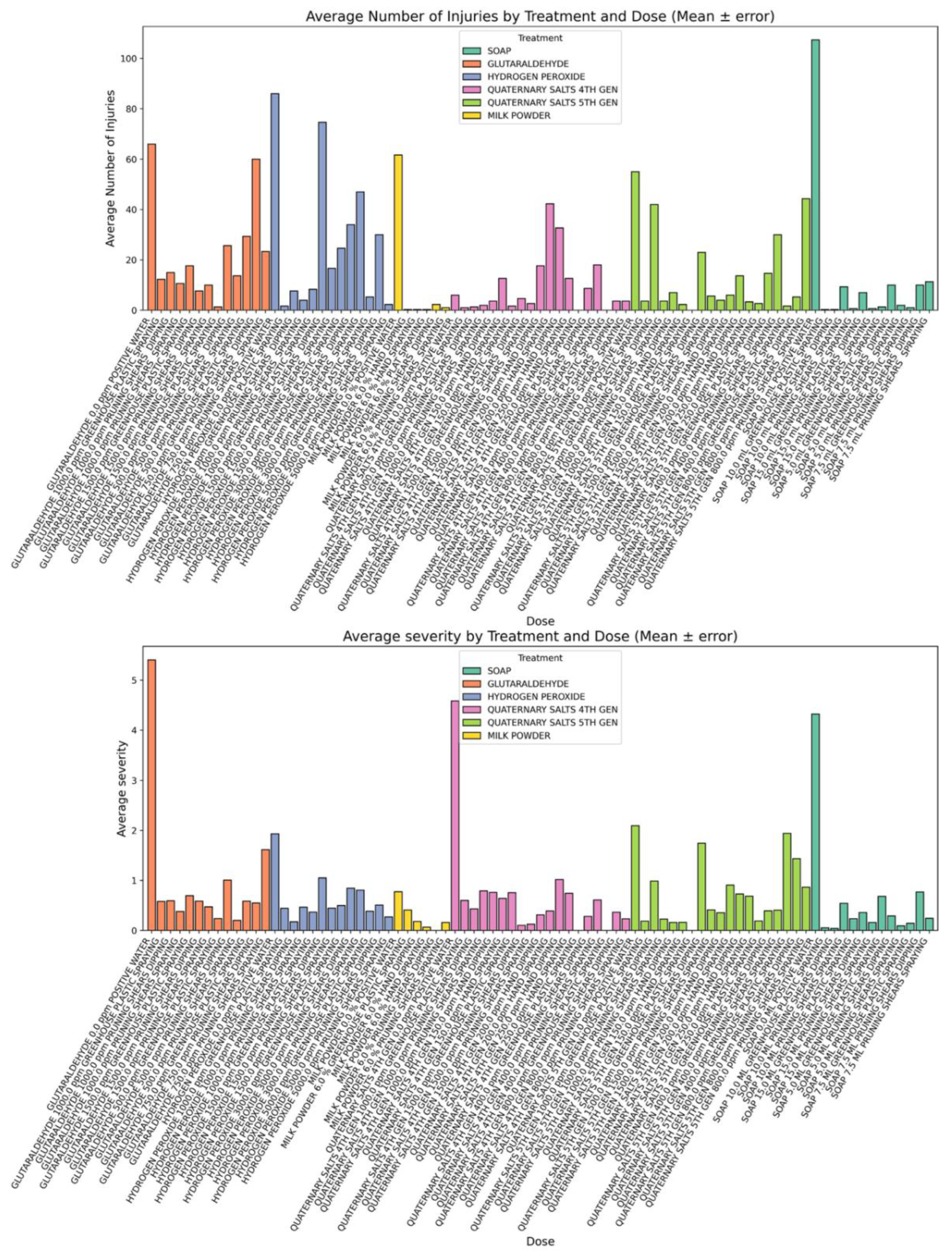

3.2.1. Lesion Count and Symptom Severity as Indicators of Transmission Efficiency

Mechanical inoculation assays on

Nicotiana rustica revealed marked differences in lesion number and symptom severity depending on the disinfectant formulation, surface type, and applied dose (

Figure 5). The positive control (infected mock treatment) consistently produced the highest infection levels, with an average of >100 lesions per leaf and severe necrotic symptoms, confirming efficient ToBRFV transmission. In contrast, several disinfectant treatments markedly reduced infection intensity.

5°QAS were the most effective chemical disinfectants, reducing lesion counts to fewer than 10 per leaf at intermediate to high doses. 4°QAS exhibited moderate but more variable efficacy. Glutaraldehyde and hydrogen peroxide showed dose-dependent effects but their performance fluctuated substantially across surface types, particularly on pruning shears. In agreement with the digital-based lesion quantification, treatments in the dip and plastic–spray conditions showed greater consistency than pruning shears, where organic residues and metallic surfaces likely interfered with virion inactivation. Powdered milk (6%) also reduced lesion formation across replicates. Soap (alkaline hydroxide formulation) demonstrated moderate reduction in lesion counts but did not consistently prevent infection on metal tools. Lesion severity followed similar trends to lesion number. Treatments that yielded fewer lesions typically displayed <1% symptomatic leaf area, whereas untreated controls and ineffective disinfectants reached up to 5% necrotic or chlorotic tissue. Intermediate treatments showed higher variability (larger SD values), reflecting inconsistent disinfectant performance, particularly at suboptimal doses.

Collectively, these results confirm that lesion number and severity are reliable and complementary indicators of ToBRFV mechanical transmission, and underscore that disinfectant efficacy is influenced more by chemical formulation and surface interaction than by concentration alone. This reinforces the need for formulation-specific protocols rather than concentration-based assumptions in greenhouse sanitation practices.

3.2.2. Comparative Performance of Disinfectant Formulations and Application Doses

To dissect the quantitative response of disinfectant treatments, lesion distributions and symptom severity were examined across all dose levels and formulations (

Figure 6). These analyses demonstrated that ToBRFV inactivation was not solely dose-dependent, but strongly modulated by surface type, application method, and product chemistry. Untreated positive controls consistently exhibited the highest lesion counts ( > 100 lesions per leaf), confirming efficient mechanical transmission. In contrast, 5°QAS produced the most consistent reductions in lesion numbers across doses, particularly under plastic spray conditions.

According to the descriptive dose–response evaluation, the most and least effective concentrations were identified for each disinfectant across all treatments. The highest-performing doses were glutaraldehyde at 500 ppm, hydrogen peroxide at 1000 ppm, fourth-generation quaternary ammonium salts at 1000 ppm, fifth-generation quaternary ammonium salts at 1500 ppm, and liquid soap at 10 mL (

Figure 6A). With the exception of 6% milk powder, whose optimal performance was achieved through hand spraying, all of these effective doses were associated with greenhouse plastic spraying. Consistently, greenhouse plastic spraying emerged as the most effective application method in five out of the six disinfectant formulations evaluated. Across treatments, milk powder and soap displayed the highest observed virucidal performance, achieving mean lesion counts as low as 0.33. Fourth- and fifth-generation quaternary ammonium salts also showed strong and stable activity, particularly at intermediate doses (800–1000 ppm). In contrast, glutaraldehyde and hydrogen peroxide exhibited greater variability, resulting in reduced stability and lower reliability for consistent ToBRFV inactivation.

Overall, these results indicate that fifth-generation quaternary ammonium salts (5°QAS) remain the most reliable chemical formulation for greenhouse sanitation, while the disinfection of tools—especially pruning shears—continues to represent a vulnerable point in the mechanical transmission of ToBRFV.

Complementary to the lesion-based virucidal assessment, the analysis of leaf damage severity identified the doses producing the lowest percentage of symptomatic tissue for each treatment (

Figure 6B). Glutaraldehyde at 500 ppm applied through pruning shears spraying resulted in the lowest severity (0.20%). For hydrogen peroxide, the minimum severity was observed at 1000 ppm via pruning shears dipping (0.18%). The 6% milk powder treatment produced the lowest severity (0.07%) when applied by hand spraying, whereas fourth-generation quaternary salts at 1500 ppm via pruning shears dipping yielded 0.10%. For fifth-generation quaternary salts, the lowest severity (0.16%) occurred at 1500 ppm using greenhouse plastic spraying. Soap at 10 mL applied through pruning shears dipping yielded the lowest severity overall (0.04%).When treatments were compared globally, soap, fifth-generation quaternary salts, and milk powder were the most effective at minimizing leaf damage severity, followed by fourth-generation quaternary salts. As in the virucidal assay, hydrogen peroxide and glutaraldehyde were the least effective, presenting higher and more variable severity values across dose–method combinations. The dipping technique was frequently represented among the highest-severity outcomes.

The least efficient dose–method combinations were also identified. For glutaraldehyde, 750 ppm via pruning shears spraying resulted in 1.62% severity; for hydrogen peroxide, 1500 ppm with pruning shears dipping produced 1.05%. For 6% milk powder, the least effective condition was greenhouse plastic spraying (0.41%). For fourth-generation quaternary salts, the lowest performance occurred at 250 ppm via hand dipping, while for fifth-generation quaternary salts, 800 ppm delivered through greenhouse plastic spraying resulted in the highest severity among all treatments (1.94%). For soap, the least effective combination was 7.5 mL applied through pruning shears dipping (0.77%). Overall, fifth-generation quaternary salts at 800 ppm represented the single least effective dose–method combination in the dataset.

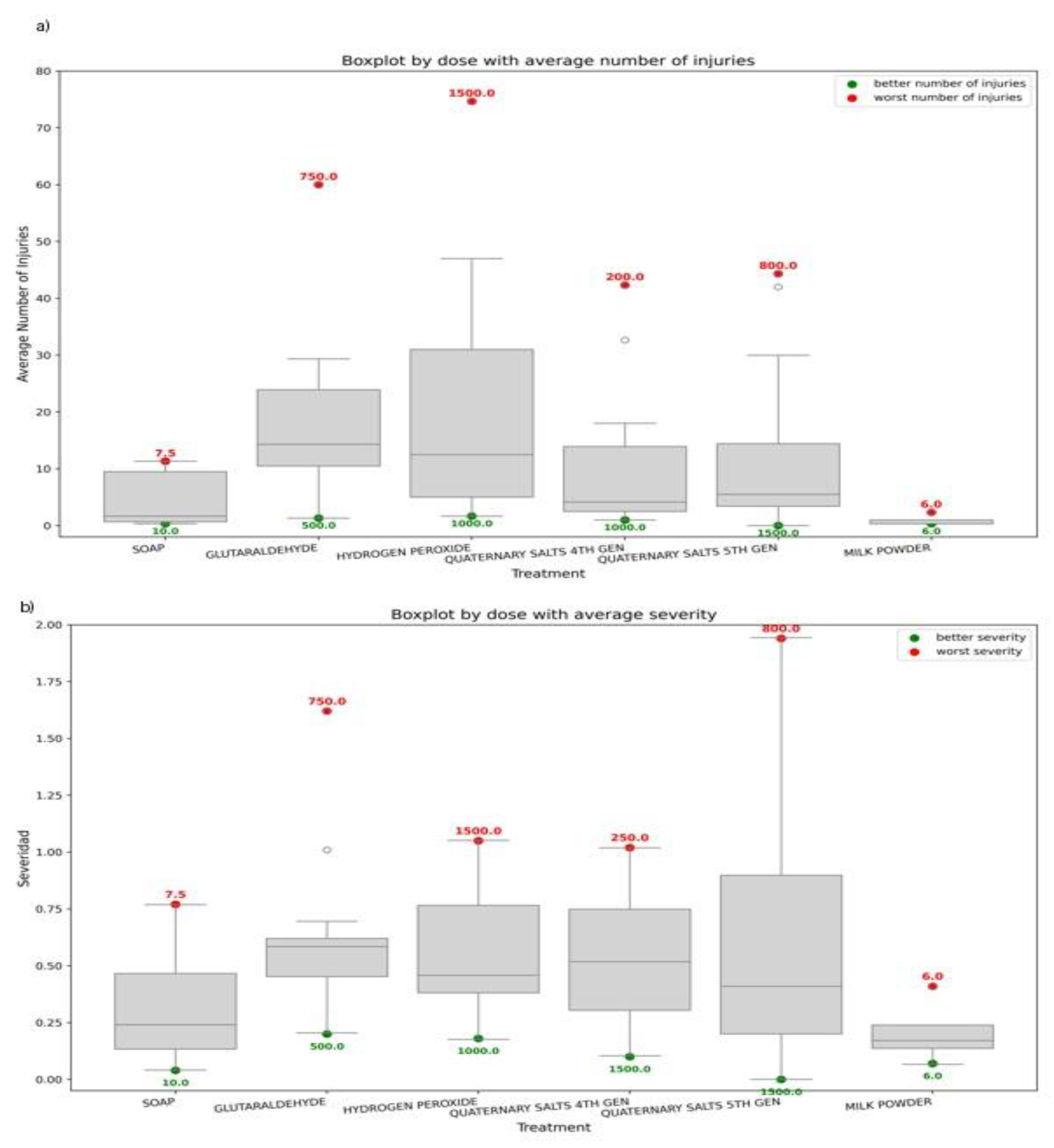

3.2.3. Dose–Response Relationships Between Disinfectant Concentration and ToBRFV Infection

To investigate whether ToBRFV inactivation followed a dose-dependent pattern, generalized regression analyses were applied to lesion count and symptom severity data across all disinfectant concentrations (

Figure 7). Overall, only weak negative correlations were detected between disinfectant concentration and infection intensity (

r < 0.25), reinforcing that concentration alone was not a strong determinant of viral suppression.

Quaternary ammonium compounds—particularly 5°QAS—showed the most consistent downward trend in lesion counts with increasing dose; however, the response plateaued rapidly, suggesting early saturation of virucidal activity. Powdered milk also exhibited a modest reduction in lesion numbers at higher concentrations. In contrast, glutaraldehyde and hydrogen peroxide displayed highly variable trends across concentrations and surfaces, with no consistent linear or nonlinear dose-response relationships. Symptom severity followed a comparable pattern, with slight decreases at higher doses for some treatments but substantial overlap in confidence intervals. The broad dispersion of data points and large variability, particularly on pruning shears, suggests that efficacy is more dependent on surface type, organic load, and application method than on concentration alone.

These results indicate that ToBRFV disinfection is not strictly dose-responsive, and that chemical formulation and surface interaction outweigh dose in determining antiviral efficacy. Therefore, rather than increasing concentrations, optimizing formulation, surface contact, and application protocol yields more reliable control of ToBRFV.

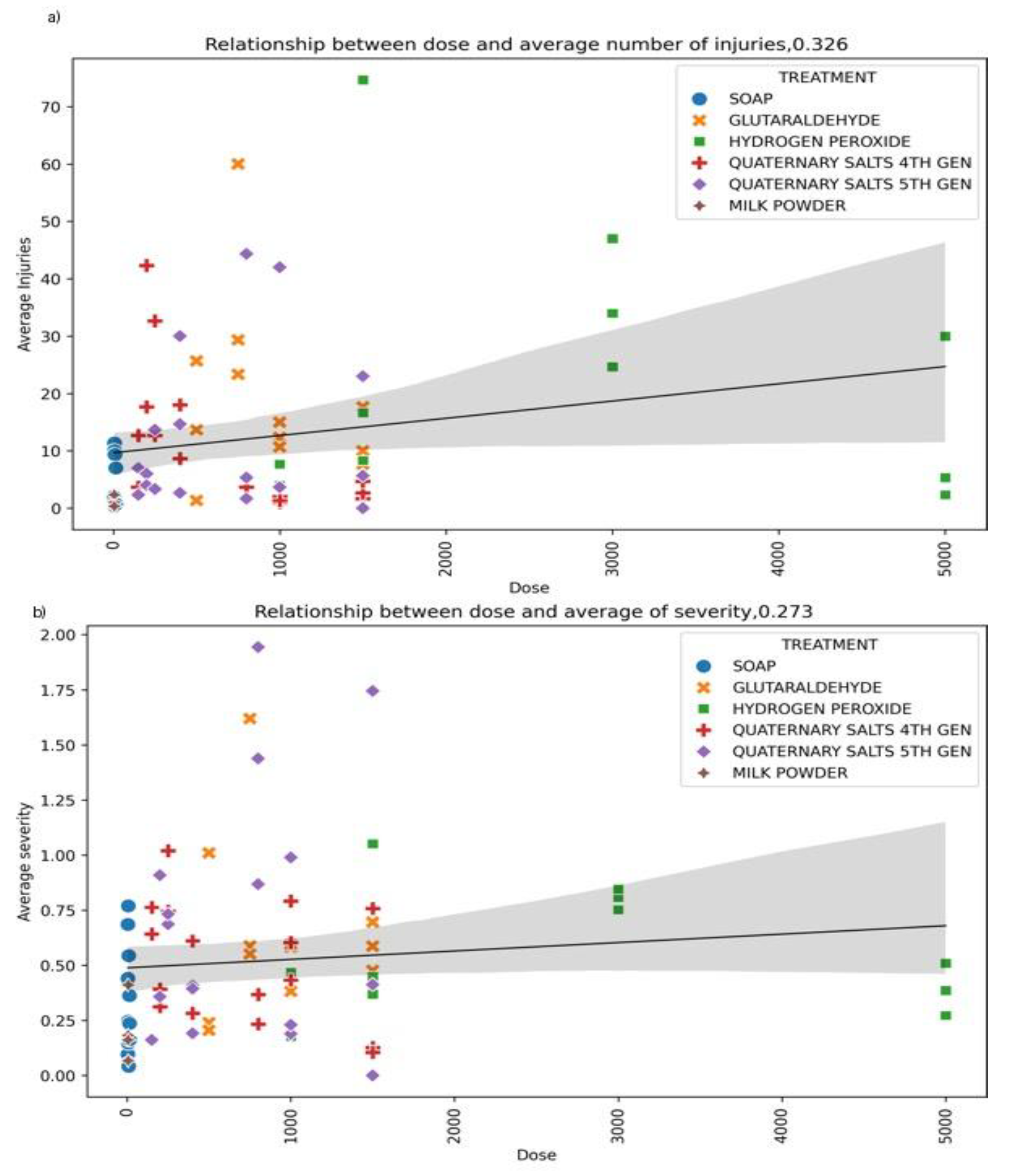

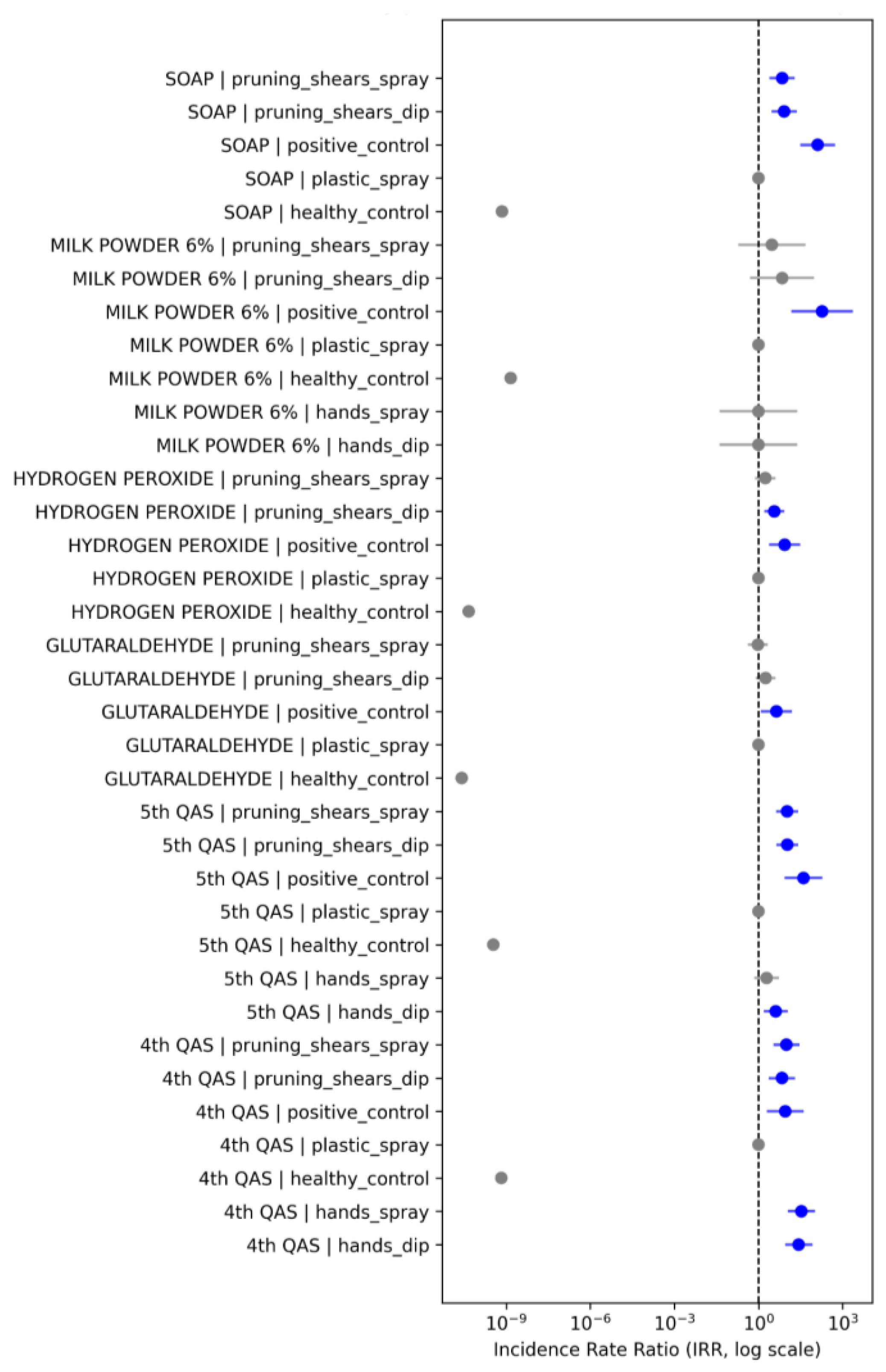

3.3. Multivariate Modeling of Surface–Method Interactions and Dose-Dependent Disinfection Dynamics

To determine how disinfectant performance is influenced by the interaction between product formulation, surface type, and application method, we developed a multivariate statistical approach integrating generalized linear modeling (GLM) and incidence rate ratio (IRR) estimation. For this analysis, only visually obtained lesion counts were used, which showed clear overdispersion (dispersion statistic = 2.65), with variance consistently exceeding the mean across treatments (Supplemental

Figure S3).

This pattern was especially pronounced in pruning shears, where both mean lesion number and variance were higher than on plastic surfaces, indicating increased viral retention and heterogeneous disinfection effects. The NB-GLM model incorporated disinfectant product, surface (plastic, pruning shears and hands), as well as application method (spray vs. dip) as fixed effects, including their interactions. Dose was entered as a product-specific covariate. Treatment efficacy was expressed using IRRs, where values <1 indicate reduced lesion incidence relative to the internal baseline condition:

plastic–spray within the same disinfectant formulation. The NB-GLM revealed distinct and consistent differences in the incidence of ToBRFV lesion formation across disinfectant formulations, surface types, and application methods. A total of 30 contrasts were evaluated, each represented in

Figure 8 by point estimates and corresponding 95% confidence intervals.

A dominant and recurrent pattern was observed for metallic pruning shears, which showed markedly higher infection incidence regardless of the disinfectant used. Under dip application, pruning shears exhibited IRR values 3.2- to 18.7-fold higher than the baseline. The most pronounced effects were associated with 4°QAS and 5 t°QAS. For instance, 5°QAS | pruning_shears_dip displayed an IRR = 18.74 (95% CI: 7.1–48.9), while 4°QAS | pruning_shears_dip reached IRR = 12.53 (95% CI: 4.8–32.1), indicating substantially reduced disinfection efficiency on metallic tools. Similarly, glutaraldehyde treatments demonstrated elevated incidence rates on pruning shears. The glutaraldehyde | pruning_shears_dip contrast yielded an IRR = 9.62 (95% CI: 3.5–26.4), whereas the spray application partially mitigated this effect (IRR = 3.14; 95% CI: 1.2–8.4). Hydrogen peroxide also showed significant increases under pruning-shears conditions, particularly in dip mode (IRR = 6.41; 95% CI: 2.7–15.8). In contrast, plastic–spray treatments remained consistently near the reference value (IRR ≈ 1) across products, confirming that polyethylene is inherently easier to disinfect and that spray application promotes more uniform chemical coverage. Treatments applied to hands showed intermediate and mostly non-significant effects, with IRRs ranging from 0.8 to 2.1, reflecting the lower viral retention capacity of skin and greater variability introduced by surface moisture and microtopography. Marked differences among disinfectants were also observed. Most contrasts involving milk powder 6% yielded non-significant IRRs (0.6–1.4), consistent with its expected mechanical shielding rather than virucidal activity. As expected, positive controls showed IRRs well above unity, whereas healthy controls consistently exhibited low incidence ratios (IRR < 0.5), reflecting the strong separation between infected and non-infected groups. Several treatments displayed extremely wide confidence intervals—sometimes spanning multiple orders of magnitude—particularly in contrast with near-complete separation in lesion counts. This pattern suggests quasi-complete treatment effects, where some treatment combinations resulted in almost no infections. Although such contrasts reduce the precision of parameter estimates, they do not alter the direction or overall interpretation of the effects. Taken together, the IRR patterns demonstrate that surface type is the major determinant of residual infectivity, with metallic pruning shears consistently acting as the most persistent reservoir of infectious ToBRFV particles. Application method further modulated efficacy, with spray outperforming dip across nearly all disinfectants. These findings underscore the need for surface-specific sanitation protocols, particularly for metallic tools in greenhouse production systems.

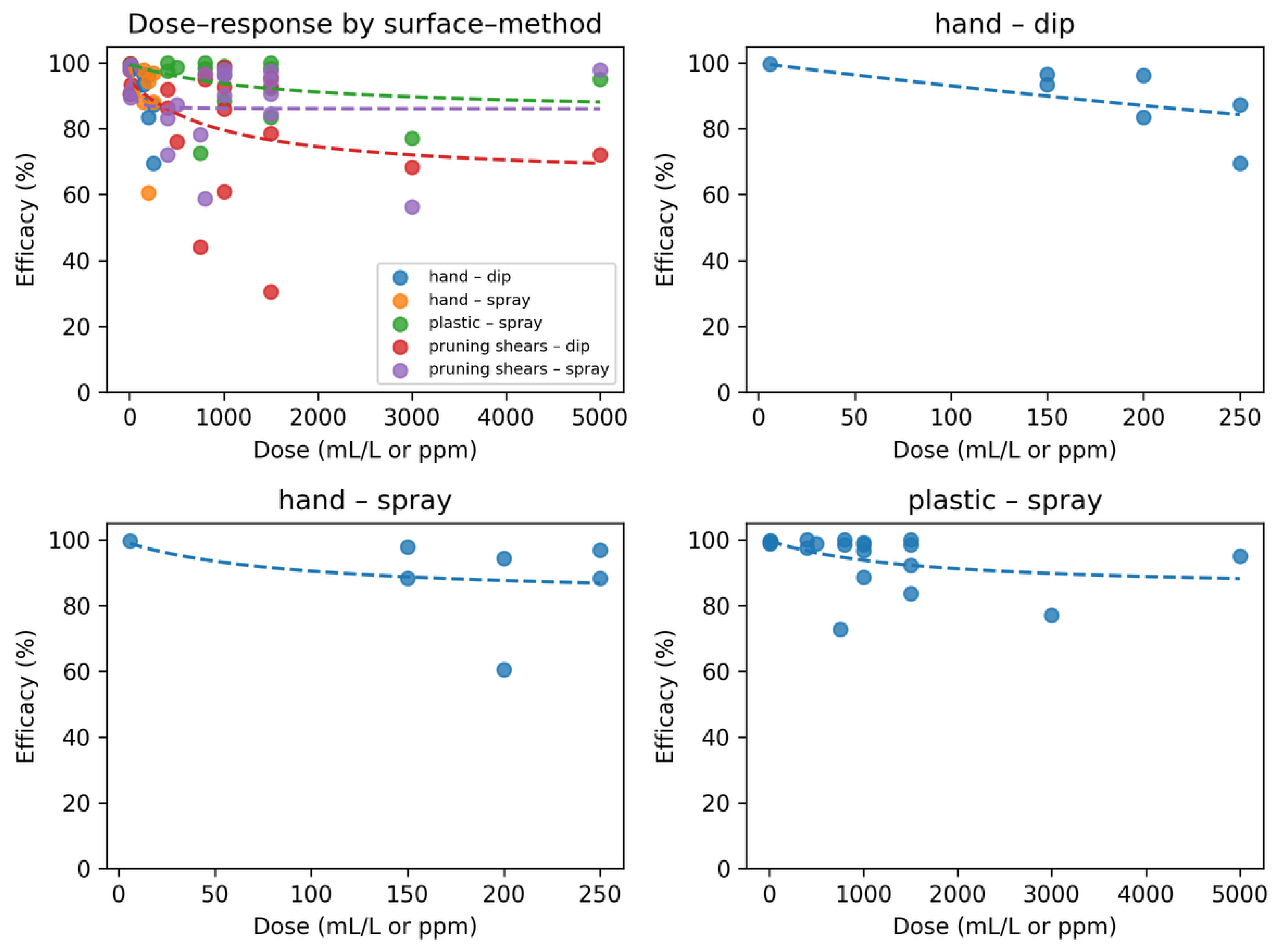

Finally, to disentangle chemical inactivation from dose-mediated effects and to explore potential nonlinearities in virucidal responses, a nonlinear Emax dose–response model was fitted for each disinfectant–surface–method combination. This model estimates two key parameters: the maximum achievable efficacy (Emax) and the doses required to reach 50% and 90% of this maximum (ED₅₀ and ED₉₀, respectively). The fitted curves revealed distinct yet generally shallow dose–response patterns across the evaluated combinations. In all spray-based applications, including hand–spray, plastic–spray, and pruning shears–spray—the estimated Emax values approached 90–100%, with ED₅₀ values falling within a very low dose range (typically <50 mL/L). These results indicate that near-complete inactivation of ToBRFV is largely dose-independent under spray application, reflecting rapid saturation of virucidal activity at minimal concentrations.In contrast, the pruning shears–dip condition displayed a flatter and consistently lower response curve, characterized by an Emax below that of spray applications and a noticeably higher ED₅₀. This pattern reflects a reduced inactivation efficiency on metallic surfaces when disinfectants are applied by immersion, consistent with the known challenges of achieving uniform liquid–surface contact on metal. Notably, efficacy declined slightly at intermediate doses, suggesting a weak nonmonotonic pattern likely driven by surface heterogeneity, micro-residue interactions, or irregular wetting dynamics.

From an operational perspective, the dose–response analysis (

Figure 9) showed that complete or near-complete inactivation was already observed at the lowest experimentally tested concentrations (5–7.5 mL/L) across all spray applications. The model-based curves support this empirical finding: increasing concentration beyond this range produced minimal additional gains in efficacy. By contrast, dip-based disinfection of metallic tools showed more variability and a lower maximal response, indicating that immersion requires either higher doses, longer contact times, or mechanical assistance to achieve comparable virucidal performance.

The combined interpretation of GLM and Emax results reinforces that disinfectant performance is not dictated solely by chemical formulation but emerges from the interacting effects of chemistry, surface material, dose, and method of application. Fourth- and fifth-generation quaternary ammonium compounds remained the most consistently effective across surfaces and methods, whereas glutaraldehyde and hydrogen peroxide exhibited greater variability, likely associated with oxidative reactivity, volatility, and sensitivity to organic residues [

32,

33].

In summary, the complementary use of NB-GLM and Emax modeling provided convergent statistical and biological insights into disinfectant performance against ToBRFV. Whereas the GLM highlighted surface–method interactions that reduce virucidal effectiveness, the Emax analysis quantified the practical limits of dose responsiveness and demonstrated early saturation under spray application. Together, these results underscore the importance of tailoring sanitation protocols to operational contexts: spray-based applications on smooth surfaces provide high and dose-stable inactivation, whereas metallic tools disinfected by immersion require additional considerations to ensure complete virus inactivation.

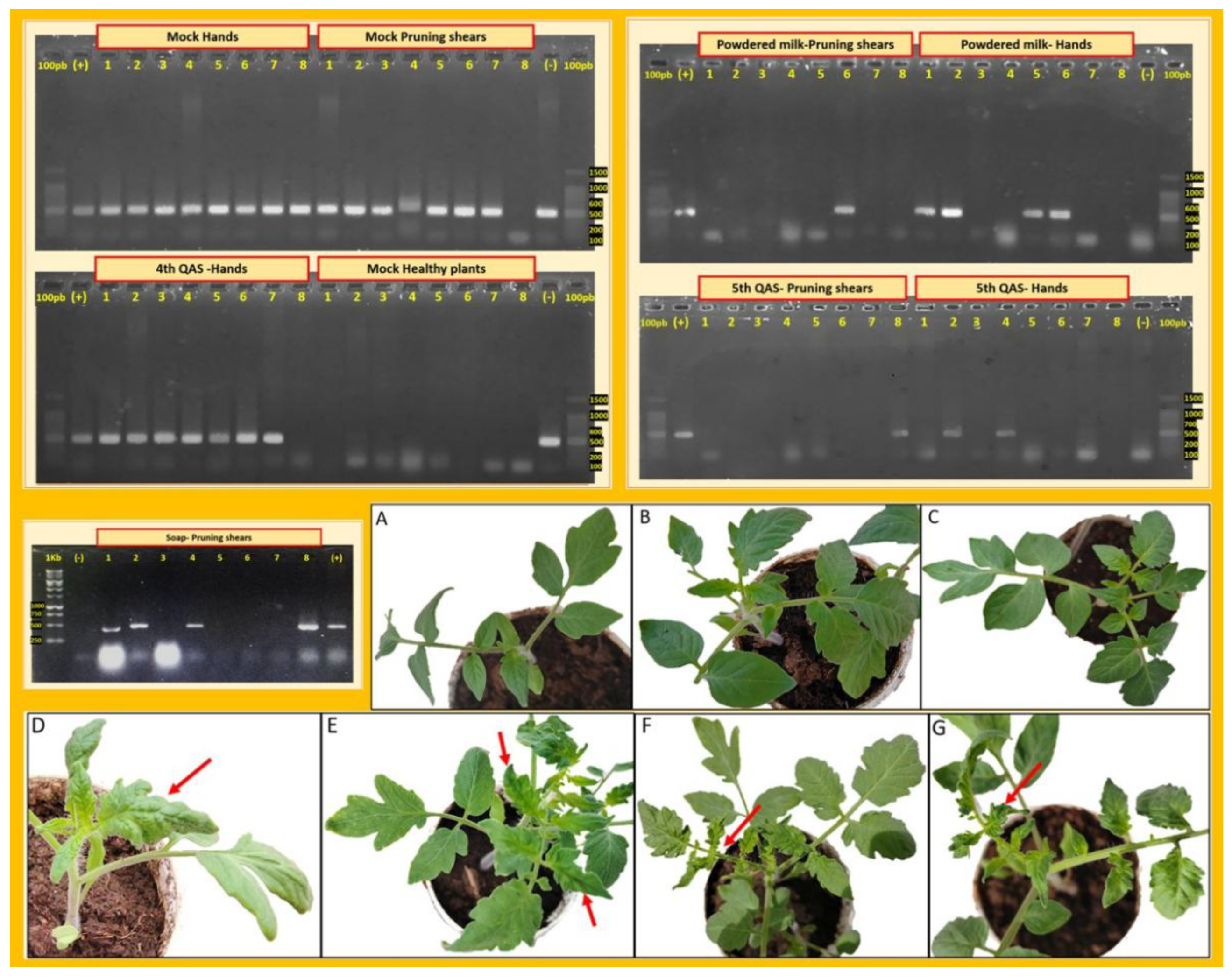

3.4. Bioassays to Evaluate the Efficacy of Disinfectant Products on Tomato Plants

Building on the lesion analyses in

Nicotiana rustica, we next assessed whether the reductions in local infection observed on indicator leaves translated into effective interruption of systemic transmission in a crop host. To this end, a subset of the most representative disinfectant–surface combinations was selected for greenhouse bioassays on tomato plants. These experiments were designed to mirror the mechanical transmission routes modeled in

N. rustica contaminated hands and pruning shears but using ToBRFV-susceptible tomato as the biologically relevant endpoint. Symptom progression and RT-PCR detection in tomato therefore provide an integrated readout of residual infectivity after disinfection, allowing us to validate and refine the risk estimates inferred from the lesion-count models. Tomato plants from the infected mock-treated controls developed ToBRFV symptoms earliest, with chlorotic mosaic and leaf deformation appearing at 6 dpi on hands and 7 dpi on pruning shears. In contrast, all disinfectant-treated groups exhibited a delay in symptom onset to approximately 11 dpi, indicating a reduced viral load or partial interruption of mechanical transmission (

Figure 10).

By 25 dpi, RT-PCR analysis confirmed marked differences in transmission efficiency across treatments (

Table 4). The 5°QAS, 400 ppm applied to pruning shears was the most effective treatment, with only 1 of 8 plants testing positive. Similarly, 5°QAS at 150 ppm on hands and powdered milk (6%) applied to either hands or pruning shears reduced infection to 2–3 infected plants per treatment, indicating partial but significant protective effects. However, this effect is interpreted as a physical interference with viral adsorption or particle stabilization rather than direct virucidal activity [

30,

31] since its performance was less consistent when transmission to tomato plants was assessed. In this context, its mode of action is likely based on physical adsorption and interference with virion mobility rather than true virucidal activity emphasizing the need for surface-specific disinfection protocols rather than generalized dose escalation or reliance on empirical products such as milk.

In contrast, 4°QAS at 150 ppm (hands) showed no reduction in infection (8/8 RT-PCR positive), performing equivalently to the untreated controls. Likewise, soap (15 mL/L) on pruning shears showed only moderate protection (4/8 positive). This suggests that certain formulations, despite being commonly used in greenhouse sanitation, are insufficient to prevent ToBRFV transmission, particularly when applied to metal tools.

These findings demonstrate that the disinfectant-driven reductions in local lesion formation observed in Nicotiana rustica are biologically meaningful and extend to a more stringent test the prevention of systemic ToBRFV infection in tomato. Whereas Nicotiana provided a sensitive, quantitative indicator of residual viral load, the tomato bioassays revealed whether that remaining inoculum was sufficient to establish a full systemic infection in a crop host. Treatment efficacy, however, varied substantially. Success depended not only on the chemical formulation but also on the surface to which it was applied. In particular, metallic pruning shears already identified in Nicotiana as having the highest IRRs again proved the most difficult to disinfect, fully consistent with their well-documented role as major mechanical vectors in greenhouse production systems.

4. Discussion

This study integrates lesion-based assays, multivariate modeling, nonlinear dose–response analyses, and systemic transmission tests to provide a multi-scale evaluation of disinfectant performance against ToBRFV. Overall, the results show that disinfectant efficacy is not determined solely by chemical formulation, but emerges from the interplay between product chemistry, surface type, and application method. Nicotiana rustica proved to be a reliable and sensitive indicator of residual infectivity, revealing consistent surface- and method-dependent differences that aligned with systemic infection outcomes in tomato. Across analyses, spray applications on plastic surfaces were the most consistently effective, whereas metallic pruning shears represented the most failure-prone scenario, even under otherwise potent chemistries. The convergence of GLM-derived IRR patterns, Emax dose–response efficiencies, and tomato bioassay outcomes highlights that sanitation protocols must be surface-specific and method-optimized to prevent mechanical transmission of ToBRFV. These integrated findings lay the foundation for a mechanistic, evidence-based discussion on the operational constraints and practical implications for greenhouse disinfection strategies.

4.1. Glutaraldehyde and 5QACs Achieve the Highest ToBRFV Inactivation, Driven by Surface and Application Method

Glutaraldehyde and 5QACs consistently exhibited the highest virucidal activity against ToBRFV across all assays, particularly in combinations involving spray application on polyethylene surfaces. These findings are consistent with prior work demonstrating that glutaraldehyde, Virkon™ S, and high-generation QAC formulations are capable of inactivating tobamoviruses, including ToBRFV, TMV, and ToMV, with high reliability under greenhouse conditions [

7,

10,

14]. The biochemical basis of this high efficacy is well understood: glutaraldehyde functions as a potent protein cross-linker, covalently modifying amino and thiol groups on capsid proteins and sometimes nucleic acids, thereby disrupting virion stability and preventing genome release during host infection [

33,

34]. Similarly, QACs maintain strong antiviral activity even against non-enveloped viruses by promoting capsid disruption, destabilizing electrostatic interactions, and interfering with virion adsorption and retention on host tissue [

13,

35]. A central mechanistic insight from this study is that disinfectant performance is not governed by chemical formulation alone: surface type and application method strongly modulate virion inactivation. Across nearly all products, the plastic–spray condition yielded the lowest lesion counts and IRR values. Polyethylene surfaces are chemically inert, non-porous, and exhibit negligible organic residue interference, enabling more consistent disinfectant–virion contact. Similar trends have been reported for tobamovirus inactivation on polymeric greenhouse films [

14,

36]. In contrast, pruning shears—especially under dip applications—were consistently the most difficult surface to disinfec

t, regardless of the chemical used. Metal tools accumulate oxidized plant sap films, micro-abrasions, and metallic ions that adsorb or neutralize disinfectant molecules and physically shield virions from contact [

12,

14,

25,

37]. Organic residues in particular are known to impair the effectiveness of aldehydes, QACs, and oxidizing agents, reducing their virucidal capacity under immersion conditions where contact with contaminated metal surfaces accelerates chemical degradation [

7,

34,

38]. These mechanisms are directly reflected in the IRR results of this study, where pruning-shears–dip produced IRR values as high as 18.7, indicating markedly greater residual infectivity relative to plastic–spray. Spray applications demonstrated intermediate levels of efficacy—often comparable to plastic–dip but less predictable on irregular surfaces. This is consistent with observations by Rodríguez-Díaz et al. (2022) [

25], who noted that although spraying improves surface coverage, incomplete wetting and reduced contact time can compromise virucidal performance, especially on textured or contaminated surfaces. Conversely, soap (alkaline hydroxide) and powdered milk (6%) showed limited virucidal activity. These treatments rely primarily on mechanical removal or protein adsorption, rather than irreversible inactivation of virions. Tobamoviruses possess extremely stable rod-shaped capsids that resist denaturation even under alkaline conditions, contributing to their environmental persistence [

39]. Casein proteins in milk may even stabilize virions by forming protective micelle–virion complexes, a phenomenon extensively documented in early virology studies [

40,

41]. The variability and lack of consistent IRR significance among these treatments are aligned with earlier reports describing their inconsistent or anecdotal efficacy [

10]. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that effective ToBRFV inactivation requires the right combination of disinfectant chemistry, surface characteristics, and application method. Operationally, this translates into three practical recommendations: (1) prioritize high-efficacy virucides such as glutaraldehyde and fifth-generation QACs; (2) apply disinfectants to clean, non-porous surfaces using spray methods that maximize chemical contact; and (3) avoid immersion disinfection of metallic tools unless preceded by mechanical cleaning or supplemented with higher concentrations and extended contact times.

4.2. Dose–Response Analysis Reveals Rapid Saturation for Glutaraldehyde and QACs with Extremely Low ED₅₀ Values

The dose–response analyses revealed that ToBRFV inactivation did not follow a linear, concentration-dependent trend. Instead, a saturation-type pattern emerged for the most effective disinfectants, with low to intermediate doses of glutaraldehyde and QACs already achieving near-maximal reductions in lesion incidence. Higher doses conferred minimal additional benefit, reflecting a plateau phenomenon similar to that reported in previous disinfection studies involving tobamoviruses and other non-enveloped plant viruses [

7,

17]. Mechanistically, this behavior is consistent with Emax pharmacodynamic models, where efficacy approaches a biological ceiling once virion capsid proteins have been sufficiently cross-linked, denatured, or otherwise chemically modified [

34]. Once these reactive sites are saturated, additional disinfectant may either be degraded, neutralized by organic matter, or unable to reach virions shielded within surface residues. The extremely low ED₅₀ values obtained for plastic–spray and pruning shears–spray (0.07–0.08 mL L⁻

1) highlight the rapid virion inactivation that occurs at minimal concentrations when surfaces are smooth and chemical contact is efficient. Conversely, the significantly higher ED₅₀ observed for pruning shears–dip (1.02 mL L⁻

1) confirms the inefficiency of immersion-based disinfection on metal surfaces, echoing previous findings for TMV, PepMV, and CGMMV on metallic tools and contaminated greenhouse equipment [

14,

17]. The absence of a clear dose–response signature for soap and powdered milk supports the interpretation that these treatments rely primarily on physical removal rather than chemical inactivation. Their lack of saturation behavior and variable performance reinforce the conclusion that these agents are unreliable for controlling ToBRFV spread in greenhouse environments. From a practical standpoint, identifying minimum effective dose (MED) values enables growers to avoid over-application of disinfectants, ultimately reducing costs and minimizing risks associated with phytotoxicity, worker exposure, and chemical residues. With increasing attention to maximum residue limits (MRLs) and reduced chemical inputs in intensive horticultural systems [

42], implementing MED-based sanitation protocols aligns with regulatory expectations and sustainable disease management goals. In summary, the dose–response findings indicate that optimizing disinfectant concentration—rather than maximizing it—is the most effective strategy for robust, economical, and environmentally conscious control of ToBRFV in protected tomato production.

4.3. Concordant Outcomes in Nicotiana rustica and Tomato Demonstrate Strong Predictive Power for Systemic ToBRFV Infections

The combined use of

Nicotiana rustica and tomato bioassays provided a multi-tiered, biologically grounded assessment of disinfectant efficacy against ToBRFV. Although both hosts are mechanically transmissible and highly permissive to tobamovirus infection, they capture different epidemiological scales. Local-lesion development in

N. rustica acts as a sensitive, quantitative indicator of residual inoculum [

43], whereas tomato reflects the ability of virions to establish systemic infection, the critical endpoint for outbreak risk in commercial production [

5,

39]. A major finding of this study is the high concordance between lesion-based outcomes in N. rustica and systemic infection in tomato. Treatments that generated low lesion counts, low IRRs, and high Emax values in

N. rustica—particularly glutaraldehyde, 5°QACs, and powdered milk also minimized systemic infection in tomato. The strong performance of 5°QAS at 400 ppm, which yielded only 1 infected tomato plant out of 8, is consistent with its near-complete local inactivation pattern in

N. rustica, mirroring earlier studies showing that small reductions in lesion number are often sufficient to prevent systemic spread [

7,

10,

14]. Conversely, treatments that performed poorly in

N. rustica, including 4°QAS and soap on metal surfaces, produced high tomato infection rates, matching historical data showing that even minimal inoculum of tobamoviruses can trigger systemic disease [

44,

45].

These results reinforce long-standing evidence that tobamoviruses possess extremely low infectious dose thresholds (ID₅₀) in both local-lesion hosts and crop species [

46]. Thus, the quantitative readouts from

N. rustica are highly predictive of systemic infection potential, validating their use as proxy assays for greenhouse sanitation research. Critically, the

effect of surface type was conserved across hosts. Metallic pruning shears produced the highest lesion counts, the highest IRRs (up to 18.7), the highest ED₅₀ values in Emax models, and ultimately the highest tomato transmission rates (up to 8/8 positive). This cross-host consistency mirrors reports that metal tools act as particularly resilient reservoirs of tobamovirus inoculum due to the strong adhesion of virions to steel surfaces, microscopic abrasions, sap residues, and oxidized films that protect particles from chemical inactivaton [

12,

38,

47]. Tobamovirus particles, which are rod-shaped and exceptionally stable [

39,

48], can remain infectious for months or even years on greenhouse equipment [

5,

46], and metal substrates provide ideal microenvironments for long-term viral persistence. The consistency of the pruning-shears effect across both hosts also aligns with findings that organic matter radically reduces the efficacy of aldehydes and QACs by neutralizing active molecules or preventing full contact with virions [

13,

34,

38]. Immersion (dip) treatments worsen this limitation by prolonging exposure of the disinfectant to organic debris, accelerating chemical degradation—an effect well documented for TMV, CGMMV, and ToBRFV [

7,

10,

14]. In contrast, plastic surfaces consistently showed low lesion counts in

N. rustica and low systemic infection rates in tomato, confirming decades of evsidence that smooth, inert, non-porous materials support greater disinfection efficiency [

25,

36]. This reinforces polyethylene greenhouse film as an ideal substrate for spray sanitation, providing predictable chemical–surface interactions and minimal organic interference. Despite physiological differences between

N. rustica (local lesions) and tomato (systemic mosaic and deformation), the epidemiological relationship between residual inoculum and infection outcome was stable across species. Minor differences in lesion incidence translated into meaningful differences in systemic infection likelihood, illustrating the sensitivity of tomato infection dynamics to even trace amounts of virus—a property emphasized previously for ToBRFV and related tobamoviruses [

5,

49].

Together, the comparative evidence strongly supports the conclusion that N. rustica lesion assays coupled with IRR and Emax modeling provide reliable predictors of systemic infection risk in tomato. The alignment of these multi-layered assays emphasizes the need to prevent even minimal virion carryover, particularly on metallic tools used in pruning, deleafing, and grafting. These findings provide a robust, biologically coherent foundation for designing surface-specific, application-specific sanitation strategies to mitigate ToBRFV transmission in greenhouse production systems.

4.4. Effective ToBRFV Control Requires Surface- and Method-Specific Sanitation Strategies in Greenhouse Systems

The combined findings from

Nicotiana rustica lesion assays and tomato systemic infection experiments clearly indicate that ToBRFV disinfection cannot rely on a single standardized protocol. Instead, effective sanitation requires surface-specific and method-specific approaches supported by the chemical properties of each disinfectant. High-efficacy virucides such as glutaraldehyde and 5°QAS consistently performed well across assays, even at low concentrations, aligning with prior reports on tobamovirus inactivation [

7,

10,

14]. By contrast, metallic pruning shears repeatedly emerged as the most failure-prone surface due to virion adsorption, organic interference, and the chemical reactivity of metal surfaces [

12,

25]. These results emphasize that greenhouse sanitation programs must integrate tool-specific cleaning steps, mechanical removal of residues, and validated virucidal chemistries to prevent inadvertent spread of ToBRFV during pruning, deleafing, or harvesting. This study focused on controlled greenhouse simulations and a limited set of disinfectant products. Natural variability in field conditions—including fluctuating temperatures, humidity, organic load, and worker handling practices—may affect virucidal performance in commercial settings [

17]. Additionally, the study did not assess long-term phytotoxicity, residue persistence, or the impacts of repeated disinfectant use on tool corrosion or worker safety. While

Nicotiana rustica provides a sensitive bioindicator of mechanical transmission, extending evaluations to additional hosts or environmental matrices (e.g., water, soil, substrates) would further strengthen applicability. Future work should validate these findings under commercial production conditions and incorporate real-world sanitation workflows, including contact-time optimization, tool material engineering, and combined mechanical–chemical cleaning strategies. Comparative testing of novel disinfectants, oxidizing formulations, and emerging green chemistries—such as peroxyacids, stabilized chlorine dioxide, or plant-derived biocidal compounds—may provide safer and more sustainable alternatives to aldehydes and QACs [

13]. Integrating environmental monitoring tools such as surface swabbing, qPCR-based sanitation audits, and digital decision-support systems could enable real-time assessment of ToBRFV contamination and guide adaptive disinfection strategies. Ultimately, efforts to reduce ToBRFV spread will benefit from a systems-level approach that couples effective sanitation, worker hygiene training, and early detection technologies across the greenhouse production chain.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the success of ToBRFV disinfection relies on the combined effects of disinfectant chemistry, surface characteristics, and application method. High-efficacy compounds such as glutaraldehyde and 5°QAS consistently outperformed lower-efficacy formulations, confirming their suitability for greenhouse sanitation. However, disinfectant performance declined markedly on metallic tools, highlighting pruning shears as a critical point of failure in the mechanical transmission pathway. Multivariate modeling and dose–response analyses further showed that effective inactivation is not driven by concentration alone but instead reflects the quality of chemical–surface interactions. Thus, sanitation strategies for ToBRFV should prioritize potent virucides, ensure adequate surface preparation, and reinforce tool-specific disinfection procedures. When integrated with vigilant crop hygiene, certified plant material, and rapid removal of infected plants, these measures provide a practical and robust framework for reducing ToBRFV spread in protected tomato production systems.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, KAP, EJZM and MEIM; methodology, MDCL, KAP, EJZM, RVC; software, ECC; validation ECC, EJZM and KAP; formal analysis, KAP, ECC; investigation RVC and MDCL; resources RVC, MDCL ; data curation ECC, KAP; writing—original draft preparation, KAP, EJZM, ECC; writing—review and editing, KAP. EJZM; visualization, KAP, ECC, EJZM; supervision, KAP; project administration, ZMEJ, MEIM; funding acquisition EJZM, MEIM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

KAP (CVU 227919) and ECC (CVU 412653) received a fellowship from Secihti Mexico. The APC was funded by AMERICAN PHARMA SA DE CV.

Data Availability Statement

All analysis scripts are available at https://github.com/kap8416/DisinfectantsToBRFV.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Rosemarie Hammond for providing the BioRender license used to create the figures included in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of the study.

References

- Salem, N.; Mansour, A.; Ciuffo, M.; Falk, B. W.; Turina, M. A new tobamovirus infecting tomato crops in Jordan. Arch. Virol. 2016, 161, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fidan, H.; Pelin, S.; Kübra, Y.; Bengi, T.; Gözde, E.; Özer, C. Robust molecular detection of the new Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in infected tomato and pepper plant from Turkey. J. Integr. Agric. 2020, 19, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzo, D.; Da L., D.; Panattoni, A.; Salemi, C.; Cappellini, G.; Bartolini, L.; et al. Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus in Tomato and Pepper Seeds by RT-LAMP (real-time and visual) and Comparison with RT-PCR end-point and RT-qPCR methods. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 640932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambrón-Crisantos, J. M.; Rodríguez-Mendoza, J.; Valencia-Luna, J. B.; Alcasio-Rangel, S.; García-Ávila, C. J.; López-Buenfil, J. A.; Ochoa-Martínez, D. L. Primer reporte de Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) en Michoacán, México. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. 2019, 37, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, N. M.; Sulaiman, A.; Samarah, N.; Turina, M.; Vallino, M. Localization and Mechanical Transmission of Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus in Tomato Seeds. Plant Dis. 2022, 106, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Mejía, P.; Rodríguez-Gómez, G.; Salas-Aranda, D. A.; et al. Identification and management of tomato brown rugose fruit virus in greenhouses in Mexico. Arch. Virol. 2023, 168, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, A.; Frew, L.; Ward, R.; Hodgson, R.; Forde, S.; McDonough, S.; Webster, G.; Chisnall, K.; Mynett, M.; Buxton-Kirk, A.; Fowkes, A. R.; Weekes, R.; Fox, A. Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus: Survival and Disinfection Efficacy on Common Glasshouse Surfaces. Viruses 2023, 15, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, F. H. H.; Becker, B.; Todt, D.; Steinmann, E.; Steinmann, J. Virucidal efficacy of glutaraldehyde for instrument disinfection. GMS Hyg. Infect. Control 2020, 15, Doc34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandie, C. E.; Ogunniyi, A. D.; Ferro, S.; Hall, B.; Drigo, B.; Chow, C. W. K.; Venter, H.; Myers, B.; Deo, P.; Donner, E.; Lombi, E. Disinfection options for irrigation water: Reducing the risk of fresh produce contamination with human pathogens. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, J.; Nourinejhad Zarghani, S.; Kroschewski, B.; Büttner, C.; Bandte, M. Decontamination of Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus (ToBRFV) on shoe soles: efficacy of cleaning and disinfectant measures. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springthorpe, V. S.; Sattar, S. A. Carrier tests to assess microbicidal activities of chemical disinfectants for use on medical devices and environmental surfaces. J. AOAC Int. 2005, 88, 182–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Q.; Lim, J. Y. C.; Xue, K.; Yew, P. Y. M.; Owh, C.; Chee, P. L.; Loh, X. J. Sanitizing agents for virus inactivation and disinfection. View 2020, 1, e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, K.-S.; Gilliard, A. C.; Zia, B. Disinfectants Useful to Manage the Emerging Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus in Greenhouse Tomato Production. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanda, B.; Shamimuzzaman, M.; Gilliard, A. C.; Ling, K.-S. Effectiveness of Disinfectants against the Spread of Tobamoviruses: Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus and Cucumber Green Mottle Mosaic Virus. Virol. J. 2021, 18, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoo, J.-H. Review of Disinfection and Sterilization – Back to the Basics. Infect. Chemother. 2018, 50, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kchaou, M.; Abuhasel, K.; Khadr, M.; Hosni, F.; Alquraish, M. Surface Disinfection to Protect against Microorganisms: Overview of Traditional Methods and Issues of Emergent Nanotechnologies. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panno, S.; Caruso, G. A.; Stefano, B.; Lo Bosco, G.; Ezequiel, R. A.; Salvatore, D. Spread of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in Sicily and evaluation of the spatiotemporal dispersion in experimental conditions. Agronomy 2020, 10, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehle, N.; Bačnik, K.; Bajde, I.; et al. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus in aqueous environments — survival and significance of water-mediated transmission. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1187920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Gilliard, A. C.; Ling, K.-S. Tomato Brown Rugose Fruit Virus Is Transmissible through a Greenhouse Hydroponic System but May Be Inactivated by Cold Plasma Ozone Treatment. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelshafy, A. M.; et al. Antimicrobial activity of hydrogen peroxide for application against norovirus and other pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1456213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copes, W. E.; et al. A systematic review of quaternary ammonium compounds in plant production systems. Crop Prot. 2023, 164, 106172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; et al. Quaternary ammonium disinfectants: Current practices and future perspective. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2024, 136, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabenau, H. F.; Steinmann, J.; Rapp, I.; Schwebke, I.; Eggers, M. Evaluation of a virucidal quantitative carrier test for surface disinfectants. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarka, P.; Nitsch-Osuch, A. Evaluating the Virucidal Activity of Disinfectants According to European Union Standards. Viruses 2021, 13, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Díaz, C. I.; Zamora-Macorra, E. J.; Ochoa-Martínez, D. L.; González Garza, R. Disinfectants effectiveness in Tomato brown rugose fruit virus (ToBRFV) transmission in tobacco plants. Rev. Mex. Fitopatol. 2022, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora-Macorra, E. J.; Ochoa-Martínez, D. L.; Chavarín-Camacho, C. Y.; Hammond, R. W.; Aviña-Padilla, K. Genomic insights into host-associated variants and transmission features of a ToBRFV isolate from Mexico. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1580000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bankhead, P.; et al. QuPath: Open source software for digital pathology image analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, C. A.; Rasband, W. S.; Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wintermantel, W. M. A comparison of disinfectants to prevent spread of potyviruses in greenhouse tomato production. Plant Health Prog. 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Baysal-Gurel, F.; Abdo, Z.; et al. Evaluation of disinfectants to prevent mechanical transmission of viruses and a viroid in greenhouse tomato production. Virol. J. 2015, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, I.; Silva, M.; Grácio, M.; Pedroso, L.; Lima, A. Milk Antiviral Proteins and Derived Peptides against Zoonoses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuladhar, E.; Terpstra, P.; Koopmans, M.; Duizer, E. Virucidal efficacy of hydrogen peroxide vapour disinfection. J. Hosp. Infect. 2012, 80, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, A.; Pușcaș, C.; Patrascu, I.; et al. Stability of Glutaraldehyde in Biocide Compositions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonnell, G.; Russell, A. D. Antiseptics and disinfectants: activity, action, and resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12, 147–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerba, C. P. Disinfection. In Environmental Microbiology, 3rd ed.; Pepper, I. L., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, NL, 2015; pp. 645–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R. E.; Thomas, B. C.; Conly, J.; Lorenzetti, D. Cleaning and disinfecting surfaces in hospitals and long-term care facilities for reducing hospital- and facility-acquired bacterial and viral infections: a systematic review. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 122, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. J.; Choi, D. H.; Choi, H. J.; Park, D. H. Risk of Erwinia amylovora transmission in viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state via contaminated pruning shears. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 165, 433–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampf, G. Efficacy of ethanol against viruses in hand disinfection. J. Hosp. Infect. 2018, 98, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanssen, I.M.; Lapidot, M.; Thomma, B.P.H.J. Emerging viral diseases of tomato crops. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 2010, 23, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cunliffe, H. R.; Blackwell, J. H. Survival of Foot-and-Mouth Disease Virus in Casein and Sodium Caseinate Produced from the Milk of Infected Cows. J. Food Prot. 1977, 40, 389–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazimierska, K.; Kalinowska-Lis, U. Milk Proteins—Their Biological Activities and Use in Cosmetics and Dermatology. Molecules 2021, 26, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Pesticide residues in food: Joint FAO/WHO Meeting on Pesticide Residues — Report 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240090187 (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Holmes, F.O. Local Lesions in Tobacco Mosaic. Botanical Gazette 1929, 87, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, L. Epidemiology and control of Tomato mosaic virus. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 1976, 14, 75–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitzky, N.; Smith, E.; Lachman, O.; Luria, N.; Mizrahi, Y.; Bakelman, H.; Sela, N.; Laskar, O.; Milrot, E.; Dombrovsky, A. The bumblebee Bombus terrestris carries a primary inoculum of Tomato brown rugose fruit virus contributing to disease spread in tomatoes. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0210871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hull, R. Plant Virology, 5th ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-12-384871-0. [Google Scholar]

- Caruso, A. G.; Bertacca, S.; et al. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus: a pathogen that is changing the tomato. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2022, 180, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendlandt, T.; Britz, B.; Kleinow, T.; Hipp, K.; Eber, F.J.; Wege, C. Getting Hold of the Tobamovirus Particle—Why and How? Purification Routes over Time and a New Customizable Approach. Viruses 2024, 16, 884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Griffiths, J.; Marchand, G.; Bernards, M.; Wang, A. Tomato brown rugose fruit virus: An emerging and rapidly spreading plant RNA virus that threatens tomato production worldwide. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 23, 1262–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Diagram of the workflow used for calculating the severity of injuries and for calculating injury and severity statistics prior to tomato host bioassays. Image created with

www.biorender.com.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the workflow used for calculating the severity of injuries and for calculating injury and severity statistics prior to tomato host bioassays. Image created with

www.biorender.com.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the experimental workflow used to evaluate disinfectant efficacy against ToBRFV on different surfaces. (1) Preparation of ToBRFV-positive inoculum by macerating infected tissue in phosphate buffer (1:10, w/v). (2) Artificial inoculation of surfaces: human hands, greenhouse plastic, and pruning shears by immersion in the inoculum. (3) Application of disinfectant treatments via backpack spraying or immersion. (4) Recovery of viral particles from treated surfaces using phosphate-buffered swabs. (5) Mechanical inoculation of

Nicotiana rustica leaves with collected swabs, using carborundum as an abrasive. (6) Quantification of local lesions at 8 dpi. Image created with

www.biorender.com.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the experimental workflow used to evaluate disinfectant efficacy against ToBRFV on different surfaces. (1) Preparation of ToBRFV-positive inoculum by macerating infected tissue in phosphate buffer (1:10, w/v). (2) Artificial inoculation of surfaces: human hands, greenhouse plastic, and pruning shears by immersion in the inoculum. (3) Application of disinfectant treatments via backpack spraying or immersion. (4) Recovery of viral particles from treated surfaces using phosphate-buffered swabs. (5) Mechanical inoculation of

Nicotiana rustica leaves with collected swabs, using carborundum as an abrasive. (6) Quantification of local lesions at 8 dpi. Image created with

www.biorender.com.

Figure 3.

Experimental workflow for evaluating the efficacy of selected disinfectants in preventing ToBRFV mechanical transmission to tomato plants. (1) Symptomatic ToBRFV-infected tomato plants were used as the virus source. (2) Inoculum was transferred through mechanical contact via pruning tools or direct hand handling. (3) Disinfectant treatments were applied by spraying. (4) Healthy tomato plants (

Solanum lycopersicum, saladette type) were inoculated by cutting with contaminated pruning shears or by manual handling. (5) Symptom development was monitored, and leaf samples were collected at 25 dpi for RNA extraction. (6) RT-PCR detection of ToBRFV was performed, followed by agarose gel electrophoresis for amplicon visualization. Image created with

www.biorender.com.

Figure 3.

Experimental workflow for evaluating the efficacy of selected disinfectants in preventing ToBRFV mechanical transmission to tomato plants. (1) Symptomatic ToBRFV-infected tomato plants were used as the virus source. (2) Inoculum was transferred through mechanical contact via pruning tools or direct hand handling. (3) Disinfectant treatments were applied by spraying. (4) Healthy tomato plants (

Solanum lycopersicum, saladette type) were inoculated by cutting with contaminated pruning shears or by manual handling. (5) Symptom development was monitored, and leaf samples were collected at 25 dpi for RNA extraction. (6) RT-PCR detection of ToBRFV was performed, followed by agarose gel electrophoresis for amplicon visualization. Image created with

www.biorender.com.

Figure 4.

Digital–assisted comparison of disinfectant performance against ToBRFV on Nicotiana rustica leaves. Leaves were mechanically inoculated using surfaces previously contaminated with the virus and treated with the evaluated disinfectants. The figure compares the best and worst performing treatments for each surface type (hands, pruning shears, and greenhouse plastic) and application method (spraying or dipping). Panels (a) show the original leaf images, (b) display lesion segmentation performed with QuPath 0.6.0, and (c) illustrate quantitative lesion area analysis obtained with ImageJ.

Figure 4.

Digital–assisted comparison of disinfectant performance against ToBRFV on Nicotiana rustica leaves. Leaves were mechanically inoculated using surfaces previously contaminated with the virus and treated with the evaluated disinfectants. The figure compares the best and worst performing treatments for each surface type (hands, pruning shears, and greenhouse plastic) and application method (spraying or dipping). Panels (a) show the original leaf images, (b) display lesion segmentation performed with QuPath 0.6.0, and (c) illustrate quantitative lesion area analysis obtained with ImageJ.

Figure 5.

Average number of lesions and severity of injuries per disinfectant dose.(A) Mean number of lesions per treatment dose (± SD). (B) Mean severity of injuries (± SD) observed on Nicotiana rustica leaves after mechanical inoculation with ToBRFV-contaminated surfaces treated with different disinfectant formulations. Treatments varied in concentration and application type (hands, pruning shears, or plastic film). Bars represent mean values across replicates, and error bars indicate standard deviations. Higher lesion number and severity values correspond to increased ToBRFV infection and lower disinfectant efficacy.

Figure 5.

Average number of lesions and severity of injuries per disinfectant dose.(A) Mean number of lesions per treatment dose (± SD). (B) Mean severity of injuries (± SD) observed on Nicotiana rustica leaves after mechanical inoculation with ToBRFV-contaminated surfaces treated with different disinfectant formulations. Treatments varied in concentration and application type (hands, pruning shears, or plastic film). Bars represent mean values across replicates, and error bars indicate standard deviations. Higher lesion number and severity values correspond to increased ToBRFV infection and lower disinfectant efficacy.

Figure 6.

Distribution of ToBRFV-induced lesions and injury severity across disinfectant treatments and doses.(A) Boxplot showing the distribution of lesion numbers per treatment and dose on Nicotiana rustica leaves after mechanical inoculation with ToBRFV-contaminated surfaces. (B) Corresponding percentage distribution of injury severity for each treatment and dose. Disinfectant formulations included soap, glutaraldehyde, hydrogen peroxide, quaternary ammonium salts (4 th and 5°generation), and powdered milk. Boxes represent interquartile ranges, horizontal lines indicate medians, whiskers show variability outside the upper and lower quartiles, and dots denote outliers. Treatments with lower lesion counts and severity values indicate higher antiviral efficacy.

Figure 6.

Distribution of ToBRFV-induced lesions and injury severity across disinfectant treatments and doses.(A) Boxplot showing the distribution of lesion numbers per treatment and dose on Nicotiana rustica leaves after mechanical inoculation with ToBRFV-contaminated surfaces. (B) Corresponding percentage distribution of injury severity for each treatment and dose. Disinfectant formulations included soap, glutaraldehyde, hydrogen peroxide, quaternary ammonium salts (4 th and 5°generation), and powdered milk. Boxes represent interquartile ranges, horizontal lines indicate medians, whiskers show variability outside the upper and lower quartiles, and dots denote outliers. Treatments with lower lesion counts and severity values indicate higher antiviral efficacy.

Figure 7.

Relationship between disinfectant dose and ToBRFV infection parameters.(A) Spearman correlation between disinfectant dose and the average number of lesions observed on Nicotiana rustica leaves. (B) Spearman correlation between disinfectant dose and the average percentage of lesion severity. Each point represents the mean value for a given treatment and dose, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence intervals of the regression model. Although higher doses tended to slightly reduce the number and severity of lesions, the response varied depending on the active compound, with quaternary ammonium salts and powdered milk showing the most consistent dose-dependent protection.

Figure 7.

Relationship between disinfectant dose and ToBRFV infection parameters.(A) Spearman correlation between disinfectant dose and the average number of lesions observed on Nicotiana rustica leaves. (B) Spearman correlation between disinfectant dose and the average percentage of lesion severity. Each point represents the mean value for a given treatment and dose, with shaded areas indicating the 95% confidence intervals of the regression model. Although higher doses tended to slightly reduce the number and severity of lesions, the response varied depending on the active compound, with quaternary ammonium salts and powdered milk showing the most consistent dose-dependent protection.

Figure 8.

Forest plot showing Incidence Rate Ratios (IRR) for ToBRFV lesion formation across disinfectant products, surface types, and application methods relative to the plastic–spray baseline. IRR estimates were obtained from a negative binomial generalized linear model (NB-GLM), using plastic–spray as the reference category (IRR = 1; vertical dashed line). Each point represents the estimated IRR for a specific product × surface × method combination, with 95% confidence intervals shown as horizontal bars. Blue markers indicate statistically significant increases in lesion incidence relative to the baseline (CI excluding 1), whereas gray markers denote non-significant contrasts.

Figure 8.

Forest plot showing Incidence Rate Ratios (IRR) for ToBRFV lesion formation across disinfectant products, surface types, and application methods relative to the plastic–spray baseline. IRR estimates were obtained from a negative binomial generalized linear model (NB-GLM), using plastic–spray as the reference category (IRR = 1; vertical dashed line). Each point represents the estimated IRR for a specific product × surface × method combination, with 95% confidence intervals shown as horizontal bars. Blue markers indicate statistically significant increases in lesion incidence relative to the baseline (CI excluding 1), whereas gray markers denote non-significant contrasts.

Figure 9.

Emax dose–response modeling of efficacy (%) across surface and application method combinations. Panel (A) shows all combinations together (plastic–spray, pruning shears–dip, pruning shears–spray), while panels (B), (C), and (D) display the individual fits for plastic–spray, pruning shears–dip, and pruning shears–spray, respectively. Dots represent observed efficacy values, and dashed lines represent the fitted Emax curves.

Figure 9.

Emax dose–response modeling of efficacy (%) across surface and application method combinations. Panel (A) shows all combinations together (plastic–spray, pruning shears–dip, pruning shears–spray), while panels (B), (C), and (D) display the individual fits for plastic–spray, pruning shears–dip, and pruning shears–spray, respectively. Dots represent observed efficacy values, and dashed lines represent the fitted Emax curves.

Figure 10.