1. Introduction

Sodium (Na) plays a central role in maintaining body homeostasis, as it is the predominant extracellular cation. Together with accompanying anions, sodium accounts for nearly 90% of extracellular fluid osmolality [

1]. It contributes to the regulation of fluid balance, blood pressure, and the electrical excitability of both nerve and muscle cells.

Maintaining total body sodium within a narrow range is essential for physiological stability [

2]. Sodium homeostasis is primarily achieved by the kidneys, which regulate sodium reabsorption and excretion along different nephron segments. Sodium is freely filtered at the glomerulus, and approximately 65–70% of the filtered amount is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule. Further reabsorption occurs in the loop of Henle, distal convoluted tubule, and collecting ducts. This process is under hormonal and neural control, mainly involving the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, antidiuretic hormone, natriuretic peptides, and the sympathetic nervous system [

2,

3].

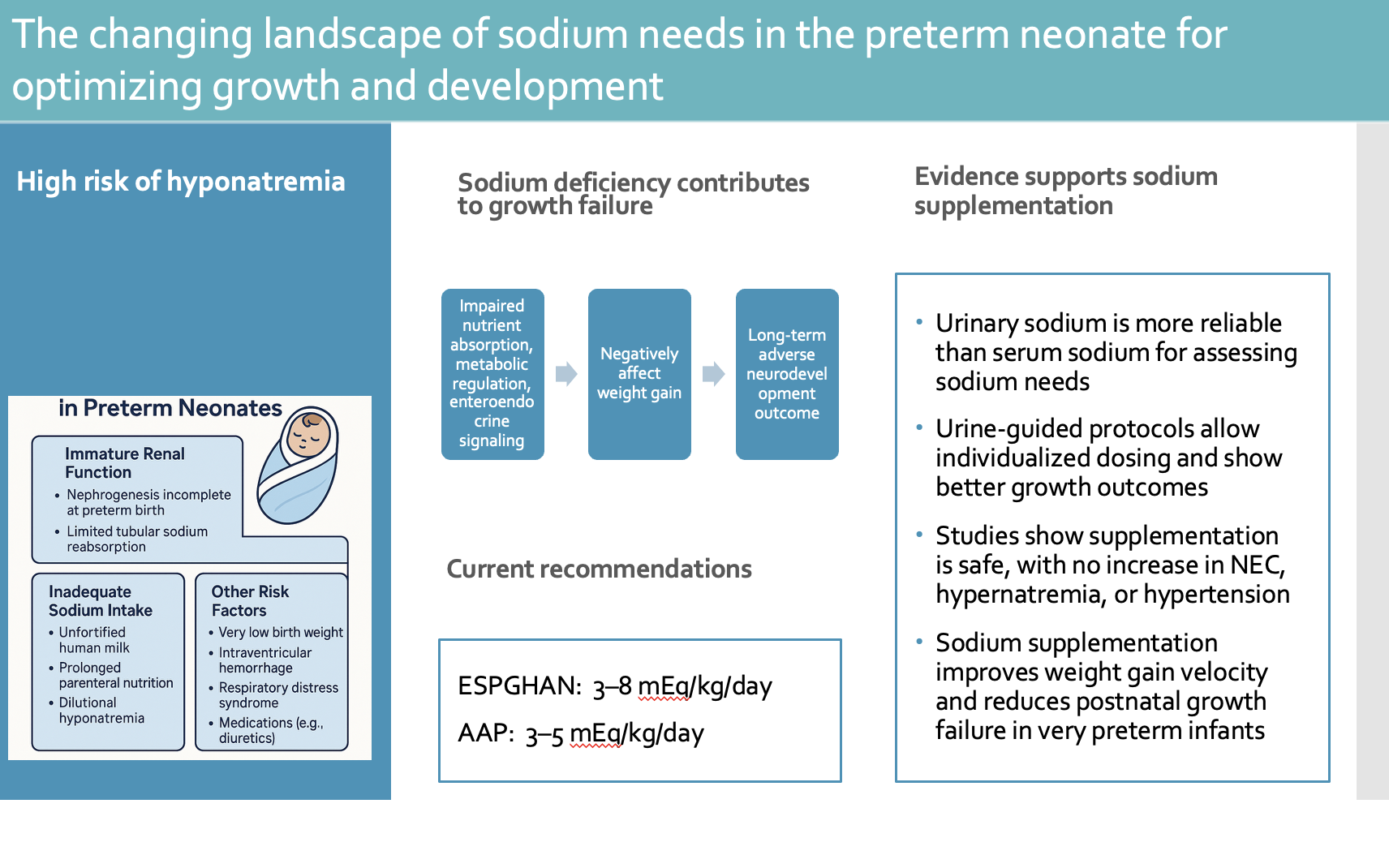

Preterm infants are particularly susceptible to dysnatremia, with early hypernatremia and later hyponatremia being the most frequent disturbances [

4]. Hyponatremia in the first 4–5 days of life is typically due to excess total body water rather than sodium loss, most often from overhydration or, less commonly, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone [

5,

6]. Beyond this period, hyponatremia usually reflects true sodium depletion resulting from immature tubular function and inadequate replacement of ongoing renal sodium losses [

7]. Hypernatremia generally arises from excessive water loss or insufficient fluid replacement, often presenting as excessive postnatal weight loss. When hypernatremia occurs without dehydration, iatrogenic sodium overload (from parenteral fluids, medications, or transfusions) should be considered [

7,

8].

Hyponatremia after the first 5 days of life is common in very preterm infants. Early studies demonstrated that negative sodium balance occurred in all infants born <30 weeks’ gestation, in 70% of those born at 30–32 weeks, 46% at 33–35 weeks, and none after 36 weeks [

9]. In very low birth weight (VLBW) infants, the incidence of hyponatremia (<130 mmol/L) increased from 25% in the first week to 65% thereafter [

10,

11]. In a retrospective cohort of 126 preterm infants born before 36 weeks of gestation, hyponatremia defined as a sodium level ≤ 132 mEq/L or 133-135 mEq/L with oral sodium supplementation, was found to 29.4% of the infants [

12].

Sodium balance is closely linked to growth and neurodevelopment in preterm infants. Without adequate supplementation, persistent renal sodium losses often lead to negative sodium balance, growth restriction, and potentially adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes [

4,

13]. Optimal intake of macronutrients and sodium in the first postnatal month is therefore crucial to support weight gain and brain development, particularly in very preterm neonates [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Even with modern nutritional strategies, nearly 50% of very low birth weight infants still experience postnatal growth failure, a problem likely influenced by sodium depletion secondary to renal losses [

18]. Current international guidelines vary regarding the recommended sodium intake for preterm infants. The ESPGHAN recently increased its suggested range to 3–8 mmol/kg/day, whereas the AAP maintains more conservative recommendations, which recommends a Na intake of 3–5 mEq/kg/day for clinically stable preterm infants with birth weight <1500 grams [

19].

This narrative review aims to synthesize current and emerging evidence on sodium requirements and supplementation in preterm neonates, to propose practical clinical strategies, and to highlight the need for further research to refine evidence-based nutritional guidelines.

2. Risk Factors for Hyponatremia in Preterm Neonates

Nephrogenesis begins around the fifth week of gestation and continues until approximately 34–36 weeks, after which no new nephrons are formed [

20]. Consequently, preterm birth interrupts this developmental process, leading to fewer nephrons at birth and potentially suboptimal renal function that may persist throughout life [

21].

In the fetus, sodium homeostasis is maintained through placental transfer and efficient renal conservation. During gestation the fetus accumulates Na at an estimated rate of 1.6–2.1 mmol/kg/day between 27 and 34 weeks of gestation [

22]. After birth, preterm infants are generally able to absorb sodium efficiently from the gastrointestinal tract, as they typically lose less than 10% of their intake through fecal excretion [

23].

Preterm infants are particularly prone to developing negative sodium balance and hyponatremia due to their limited renal tubular sodium reabsorption and the high sodium losses that occur after birth [

3,

9,

24,

25,

26]. Extremely preterm neonates (25–30 weeks’ gestation) typically show elevated urinary sodium excretion during the first week of life, which gradually decreases over the following weeks but often remains higher than that of term infants. This increased natriuresis, combined with higher aldosterone levels and reduced tubular responsiveness, contributes to substantial sodium losses and negative sodium balance, especially in very low birth weight infants (<1500 g) [

3,

9,

24,

25,

27]. Conditions common among preterm infants—such as respiratory distress syndrome, patent ductus arteriosus, and exposure to diuretics or other medications—can further worsen sodium wasting. These factors contribute to persistent renal sodium wasting during the first weeks of life [

3,

28].

One study in preterm infants reported urinary sodium losses of 5.4–7 mEq/kg/day at 2 weeks of age, decreasing to 3.5–4 mEq/kg/day by 8 weeks in infants born between 23 and 29 weeks’ gestation. The investigators also noted that urinary sodium losses declined progressively with increasing gestational age and postnatal maturity [

29]. Elevated fractional excretion of sodium (FENa) provides evidence of impaired tubular reabsorption. Both FENa and urinary sodium excretion (UNaV) are inversely correlated with gestational age and postnatal age, confirming maturational improvements in renal sodium handling [

30,

31].

Reported risk factors for hyponatremia include extreme prematurity, birth weight <1000 g, feeding with fortified human milk, and the presence of intraventricular hemorrhage [

32,

33].

For preterm infants, maternal milk alone does not provide sufficient sodium to support optimal growth. Although breast milk remains the preferred source of nutrition for premature infants [

34], its sodium content declines rapidly during the first few days after birth and is influenced by both the method of milk expression and the maternal serum sodium concentration [

35,

36,

37]. Evidence from recent studies confirms that fortified human milk, although nutritionally enhanced, still fails to meet the complete sodium and nutrient requirements of preterm infants [

38,

39]. The ESPGHAN guidelines similarly emphasize that breast milk, even when fortified, may not provide adequate sodium to meet the needs of this population [

37]. Likewise, donor human milk, even when supplemented with commercial fortifiers, is often insufficient to achieve recommended sodium intakes [

40].

Moreover, common pharmacologic interventions such administration of diuretics, indomethacin, aminoglycosides (especially Gentamicin) [

41,

42] and vancomycin further exacerbate renal sodium loss and hyponatremia [

43]. Low phosphate levels a common condition in the preterm neonate also leads to increased sodium and calcium tubular excretion as these to ions are associated in the level of proximal tubule [

44]. The combination of prematurity with in utero retardation (IUGR) renders the kidney to higher electrolytes loses among which sodium [

45]. Beyond these pathophysiological mechanisms, sodium also serves as a critical substrate for growth. Thus, preterm infants not only experience increased sodium losses but also possess elevated sodium requirements to support active cellular growth and tissue development in the early postnatal period. The summary of the risk factors for hyponatremia in preterm infants is shown in

Table 1.

3. Hyponatremia and Growth Failure

Chronic total body sodium depletion has been shown to adversely affect somatic growth in both infants and children [

46,

47]. Furthermore, poor postnatal growth during the first months of life is associated with impaired short- and long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes [

48,

49]. The mechanisms linking sodium deficiency to growth impairment are not yet fully elucidated. One proposed explanation is that extracellular sodium depletion disrupts hydrogen ion extrusion, leading to intracellular acidosis and reduced activity of growth-related receptors [

50]. Another mechanism involves the enteroendocrine function of the intestine. Intestinal glucose absorption depends largely on sodium–glucose co-transporters (SGLT-1); thus, insufficient sodium intake diminishes glucose absorption, reducing stimulation of enteroendocrine cells and consequently lowering growth factor production. In addition, impaired carbohydrate absorption may contribute to intestinal dysbiosis, further compromising growth [

13,

51]. Collectively, these mechanisms underscore the critical role of sodium in nutrient absorption, metabolic regulation, and overall growth homeostasis in the preterm infant.

4. Current Recommendations for Sodium Intake in Preterm Neonates

Preventing sodium imbalance in preterm infants requires careful management of both fluid and sodium intake [

4]. Sodium intake in this population is derived from a combination of parenteral and enteral sources. Sodium intake in preterm infants is from a combination of parenteral and enteral sources. The American Academy of Pediatrics currently recommends a Na intake of 3–5 mEq/kg/day for clinically stable preterm infants with birth weight <1500 grams [

19]. However, accumulating evidence indicates that many preterm infants require higher sodium intakes to compensate for substantial urinary sodium losses [

29,

52,

53]. Reflecting these findings, the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Committee on Nutrition has updated its guidance, recommending 3–8 mEq/kg/day in infants receiving high energy and protein intakes or experiencing notable sodium losses [

37].

5. Sodium Assessment and Supplementation in Preterm Neonates

Serum sodium concentration is often used as a clinical indication for initiating sodium supplementation in neonates. However, serum sodium primarily reflects the balance between sodium and water rather than the absolute total body sodium content. Evidence from in vivo studies indicates that serum sodium is a relatively poor indicator of overall sodium status [

54,

55]. In contrast, urinary sodium concentration provides more useful information for assessing sodium depletion and guiding supplementation strategies [

16]. In preterm infants, a low urinary sodium concentration (<30–40 mEq/L) generally suggests, though does not definitively confirm, depletion of total body sodium stores [

56]. Therefore, routine urine sodium monitoring may allow earlier and more precise correction of sodium deficits than reliance on serum levels alone.

A 2023 meta-analysis including nine studies of preterm infants born before 37 weeks’ gestation or with birth weight <2500 g found that higher late sodium intake reduced the incidence of hyponatremia (<130 mmol/L). However, only one small study reported that increased late sodium intake was associated with a lower incidence of postnatal growth failure [

4].

Across more than a dozen studies spanning several decades [

17,

29,

52,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63,

64,

65], the evidence consistently demonstrates that sodium supplementation in preterm infants—particularly those born very preterm or with very low birth weight—is associated with improved growth outcomes without significant safety concerns. The studies conducted regarding sodium supplementation in preterm infants are shown in

Table 2. Earlier studies have shown that very preterm neonates fail to achieve adequate weight gain when sodium supplementation is not given [

9,

61]. In contrast, enhanced enteral sodium intake has been shown to promote improved growth outcomes [

17,

29,

52,

60,

65]. While evidence supports sodium supplementation for biochemical stability, data on its long-term growth benefits remain limited and warrant further trials.

Randomized controlled trials, including recent high-quality modern studies, demonstrate that sodium intakes of approximately 3–5 mEq/kg/day improve weight gain velocity, reduce postnatal growth failure, and support better early fluid balance. In a randomized controlled trial, Isemann et al. supplemented preterm infants born at <32 weeks’ gestation with 4 mEq/kg/day of sodium. Infants in the intervention group had fewer instances of serum sodium <135 mmol/L and demonstrated greater weight gain velocity during the first six weeks of life, though length and head circumference growth did not differ significantly between groups [

52].

Studies using urine sodium–based algorithms (Segar et al.; Stalter et al.) show that structured, physiology-driven protocols can identify infants with sodium deficiency early and safely increase sodium intake [

17,

29]. Segar et al. supplemented preterm infants with 4 mEq/kg/day above standard sodium intake, increasing supplementation by an additional 2 mEq/kg/day if urine sodium remained below target. Urinary sodium was assessed every two weeks beginning at two weeks of age. Infants receiving supplementation showed greater mean weight and weight gain at both 2 and 8 weeks compared with controls [

29]. A similar protocol was followed by Stalter et al. in which sodium supplementation was initiated when spot urine sodium was below the expected range for gestational and postnatal age or when serum sodium ≤132 mEq/L from two weeks postnatal age. Infants <30 weeks’ gestation received 4 mEq/kg/day of sodium above dietary intake, with weekly adjustments for growth. Among infants born at 26–29 weeks’ gestation, supplementation was associated with a higher mean body weight z-score at 8 weeks, greater head circumference z-score at 16 weeks, and reduced time on mechanical ventilation, while no growth effects were observed in infants ≥30 weeks’ gestation [

17].

A double-blind randomized controlled trial enrolled neonates born between 25 and 30+6 weeks and provided Na supplementation of 4 mEq/kg/day orally. The authors concluded that early postnatal sodium supplementation significantly enhances in-hospital weight and linear growth, with untreated infants requiring an additional eight days to achieve equivalent monthly weight gain [

64]. Petersen et al. reported that sodium-supplemented infants were smaller and less mature at baseline but exhibited improved serum sodium levels, weight gain, and head circumference growth without an increase in hypernatremia [

65]. These findings highlight early sodium supplementation as a practice guided by gestational age and urinary sodium, which appears both safe and effective in promoting growth among the most immature infants.

6. Complications from Na Supplementation

Rapid fluctuations in serum sodium concentration during the first month of life have been associated with adverse long-term neurological outcomes [

10]. Potential complications of excessive sodium supplementation include hypernatremia, which may lead to fluid retention, hypertension, respiratory compromise, intraventricular hemorrhage, seizures, and thrombosis [

66]. Conversely, sodium depletion has been linked to both growth failure and impaired neurodevelopmental outcomes [

67].

Concerns have been raised regarding the risk of hyperosmolar feeds contributing to necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC); however, in studies sodium supplementation has not been associated with feed intolerance, NEC, hyponatremia, or hypernatremia or an increase in common prematurity-related morbidities [

64,

68,

69] [

17,

52,

63]. No infant required sodium supplementation to be discontinued due to hypernatremia (serum sodium concentration > 144 mEq/L) [

29]. Overall, current evidence supports the safety of sodium supplementation when dosing and monitoring are carefully adjusted to the infant’s gestational age and renal function

7. Conclusions and Future Directions

Despite decades of investigation, optimal sodium management in preterm infants remains an evolving field. Current evidence clearly demonstrates that immature renal function, high urinary sodium losses, and insufficient sodium content in human milk collectively place very preterm infants at substantial risk for negative sodium balance, hyponatremia, and postnatal growth failure. Although both observational studies and randomized trials consistently show that sodium supplementation improves biochemical stability and supports early growth, several important gaps remain.

First, the physiological variability in sodium handling among preterm infants of different gestational ages suggests that a “one-size-fits-all” supplementation strategy may be inadequate. Emerging data support the use of individualized, physiology-based approaches, particularly algorithms incorporating urine sodium concentrations to guide supplementation. However, these strategies have not yet been validated in large, multicenter prospective trials. A major future priority is determining whether routine, longitudinal urine sodium monitoring improves growth, reduces morbidity, or affects long-term neurodevelopment compared with traditional serum-based approaches.

Second, although short-term growth outcomes appear to benefit from higher sodium intake, there is limited evidence on long-term growth, cardiovascular, and neurodevelopmental effects. This is particularly relevant given concerns about potential risks of excessive supplementation, including hypertension or abnormal fluid balance, despite current studies showing reassuring safety profiles. Future research should clarify the upper safe limit of sodium intake in extremely preterm infants and assess whether early sodium supplementation has long-term beneficial effects.

Third, nutritional practices have evolved considerably, including increased use of donor human milk and standardized fortifiers. As these feeding strategies inherently provide lower sodium than maternal milk, reevaluation of sodium recommendations in the context of contemporary nutrition is urgently needed. Studies should also explore how sodium interacts with other growth-limiting factors, such as protein intake, phosphate deficiency, diuretic exposure, and intrauterine growth restriction, to influence growth and metabolic outcomes.

Finally, research is needed to further elucidate how sodium depletion affects cellular growth pathways, intestinal function, microbiome development, and brain maturation. Understanding these mechanisms may help refine optimal sodium targets and identify infants who may benefit most from supplementation.

In summary, while current evidence supports the safety and efficacy of sodium supplementation in very preterm infants, substantial opportunities remain to refine assessment methods, personalize supplementation strategies, and evaluate long-term outcomes. Future studies should focus on integrating physiological markers with modern nutritional practices to develop clear, evidence-based guidelines that optimize sodium balance, support healthy growth, and improve long-term development in this highly vulnerable population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.G. and M.B.; methodology, C.K.; formal analysis, C.K., N.D., CM.T..; investigation, C.K. and M.B..; resources, M.B. and CM.T.; writing—original draft preparation, C.K., N.D. and CM.T.; writing—review and editing, V.G. and M.B.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Na |

Sodium |

| ADH |

Antidiuretic Hormone |

| SIADH |

Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone secretion |

| VLBL |

Very low birthweight infants |

References

- Bie, P. Mechanisms of sodium balance: total body sodium, surrogate variables, and renal sodium excretion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2018, 315, R945–r962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernal, A.; Zafra, M.A.; Simón, M.J.; Mahía, J. Sodium Homeostasis, a Balance Necessary for Life. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segar, J.L. Renal adaptive changes and sodium handling in the fetal-to-newborn transition. Seminars in Fetal and Neonatal Medicine 2017, 22, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diller, N.; Osborn, D.A.; Birch, P. Higher versus lower sodium intake for preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnikendam, C.S.; Mu, T.S.; Aden, J.K.; Lefkowitz, W.; Carr, N.R.; Aune, C.N.; Ahmad, K.A. Dysnatremia in extremely low birth weight infants is associated with multiple adverse outcomes. J Perinatol 2019, 39, 842–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rees, L.; Brook, C.G.; Shaw, J.C.; Forsling, M.L. Hyponatraemia in the first week of life in preterm infants. Part I. Arginine vasopressin secretion. Arch Dis Child 1984, 59, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Späth, C.; Sjöström, E.S.; Ahlsson, F.; Ågren, J.; Domellöf, M. Sodium supply influences plasma sodium concentration and the risks of hyper- and hyponatremia in extremely preterm infants. Pediatr Res 2017, 81, 455–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eibensteiner, F.; Laml-Wallner, G.; Thanhaeuser, M.; Ristl, R.; Ely, S.; Jilma, B.; Berger, A.; Haiden, N. ELBW infants receive inadvertent sodium load above the recommended intake. Pediatr Res 2020, 88, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dahhan, J.; Haycock, G.B.; Chantler, C.; Stimmler, L. Sodium homeostasis in term and preterm neonates. I. Renal aspects. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1983, 58, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraton, L.; Ancel, P.Y.; Flamant, C.; Orsonneau, J.L.; Darmaun, D.; Rozé, J.C. Impact of Changes in Serum Sodium Levels on 2-Year Neurologic Outcomes for Very Preterm Neonates. Pediatrics 2009, 124, e655–e661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kloiber, L.L.; Winn, N.J.; Shaffer, S.G.; Hassanein, R.S. Late hyponatremia in very-low-birth-weight infants: incidence and associated risk factors. J Am Diet Assoc 1996, 96, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.K. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Hyponatremia in Preterm Infants. Open Access Maced J Med Sci 2019, 7, 3201–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steflik, H.J.; Pearlman, S.A.; Gallagher, P.G.; Lakshminrusimha, S. A pinch of salt to enhance preemie growth? Journal of Perinatology 2025, 45, 295–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentine, C.J.; Fernandez, S.; Rogers, L.K.; Gulati, P.; Hayes, J.; Lore, P.; Puthoff, T.; Dumm, M.; Jones, A.; Collins, K.; et al. Early amino-acid administration improves preterm infant weight. Journal of Perinatology 2009, 29, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, B.E.; Walden, R.V.; Gargus, R.A.; Tucker, R.; McKinley, L.; Mance, M.; Nye, J.; Vohr, B.R. First-Week Protein and Energy Intakes Are Associated With 18-Month Developmental Outcomes in Extremely Low Birth Weight Infants. Pediatrics 2009, 123, 1337–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, B.R.; Ziegler, A.A.; Grobe, C.C.; Grobe, J.L.; Segar, J.L. Sodium and Growth in Preterm Infants: A Review. Newborn (Clarksville) 2023, 2, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalter, E.J.; Verhofste, S.L.; Dagle, J.M.; Steinbach, E.J.; Ten Eyck, P.; Wendt, L.; Segar, J.L.; Harshman, L.A. Somatic growth outcomes in response to an individualized neonatal sodium supplementation protocol. J Perinatol 2025, 45, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, I.J.; Tancredi, D.J.; Bertino, E.; Lee, H.C.; Profit, J. Postnatal growth failure in very low birthweight infants born between 2005 and 2012. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2016, 101, F50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, R.E.; Greer, F.R. Pediatric nutrition, 8th edition. ed.; American Academy of Pediatrics: Itasca, IL, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Allegaert, K.; Flint, R.B.; Simons, S.H.P.; Krekels, E.H.J.; Knibbe, C.A.J.; Völler, S. Prediction of glomerular filtration rate maturation across preterm and term neonates and young infants using inulin as marker. Aaps j 2022, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aperia, A.; Broberger, O.; Herin, P.; Thodenius, K.; Zetterström, R. Postnatal control of water and electrolyte homeostasis in pre-term and full-term infants. Acta Paediatr Scand Suppl 1983, 305, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, E.E.; O'Donnell, A.M.; Nelson, S.E.; Fomon, S.J. Body composition of the reference fetus. Growth 1976, 40, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fusch, C.; Jochum, F. Water, Sodium, Potassium and Chloride. Nutritional Care of Preterm Infants: Scientific Basis and Practical Guidelines 2014, 110, 0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stritzke, A.; Thomas, S.; Amin, H.; Fusch, C.; Lodha, A. Renal consequences of preterm birth. Molecular and Cellular Pediatrics 2017, 4, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aperia, A.; Broberger, O.; Elinder, G.; Herin, P.; Zetterström, R. Postnatal development of renal function in pre-term and full-term infants. Acta Paediatr Scand 1981, 70, 183–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, M.G.; Hey, E.N. Effect of varying water intake on renal function in healthy preterm babies. Arch Dis Child 1985, 60, 614–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulthard, M.G. Maturation of glomerular filtration in preterm and mature babies. Early Hum Dev 1985, 11, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubhaju, L.; Sutherland, M.R.; Horne, R.S.; Medhurst, A.; Kent, A.L.; Ramsden, A.; Moore, L.; Singh, G.; Hoy, W.E.; Black, M.J. Assessment of renal functional maturation and injury in preterm neonates during the first month of life. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2014, 307, F149–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segar, D.E.; Segar, E.K.; Harshman, L.A.; Dagle, J.M.; Carlson, S.J.; Segar, J.L. Physiological Approach to Sodium Supplementation in Preterm Infants. Am J Perinatol 2018, 35, 994–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueva, A.; Guignard, J.P. Renal function in preterm neonates. Pediatr Res 1994, 36, 572–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, S.R.; Oh, W. Renal function as a marker of human fetal maturation. Acta Paediatr Scand 1976, 65, 481–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mannan, M.A.; Shahidulla, M.; Salam, F.; Alam, M.S.; Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, M. Postnatal development of renal function in preterm and term neonates. Mymensingh Med J 2012, 21, 103–108. [Google Scholar]

- Kloiber, L.L.; Winn, N.J.; Shaffer, S.; Hassanein, R. Late Hyponatremia in Very-Low-Birth-Weight Infants: Incidence and Associated Risk Factors. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 1996, 96, 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gates, A.; Marin, T.; De Leo, G.; Waller, J.L.; Stansfield, B.K. Nutrient composition of preterm mother's milk and factors that influence nutrient content. Am J Clin Nutr 2021, 114, 1719–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ertl, T.; Sulyok, E.; Németh, M.; Tényi, I.; Csaba, I.F.; Varga, F. Hormonal control of sodium content in human milk. Acta Paediatr Acad Sci Hung 1982, 23, 309–318. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, G.E.; Smith, H.A.; Cooney, F. Methods of milk expression for lactating women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016, 9, Cd006170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embleton, N.D.; Jennifer Moltu, S.; Lapillonne, A.; van den Akker, C.H.P.; Carnielli, V.; Fusch, C.; Gerasimidis, K.; van Goudoever, J.B.; Haiden, N.; Iacobelli, S.; et al. Enteral Nutrition in Preterm Infants (2022): A Position Paper From the ESPGHAN Committee on Nutrition and Invited Experts. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2023, 76, 248–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudehope, D.I. Human Milk and the Nutritional Needs of Preterm Infants. The Journal of Pediatrics 2013, 162, S17–S25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maas, C.; Wiechers, C.; Bernhard, W.; Poets, C.F.; Franz, A.R. Early feeding of fortified breast milk and in-hospital-growth in very premature infants: a retrospective cohort analysis. BMC Pediatrics 2013, 13, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrin, M.T.; Friend, L.L.; Sisk, P.M. Fortified Donor Human Milk Frequently Does Not Meet Sodium Recommendations for the Preterm Infant. J Pediatr 2022, 244, 219–223.e211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giapros, V.I.; Andronikou, S.; Cholevas, V.I.; Papadopoulou, Z.L. Renal function in premature infants during aminoglycoside therapy. Pediatr Nephrol 1995, 9, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giapros, V.I.; Andronikou, S.K.; Cholevas, V.I.; Papadopoulou, Z.L. Renal function and effect of aminoglycoside therapy during the first ten days of life. Pediatr Nephrol 2003, 18, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, J.A.; Oh, S.; Choi, C.W.; Kim, E.-K.; Kim, H.-S.; Kim, B.I.; Choi, J.-H. Risk Factors for Late-onset Hyponatremia and Its Influence on Neonatal Outcomes in Preterm Infants. J Korean Med Sci 2015, 30, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giapros, V.I.; Cholevas, V.I.; Andronikou, S.K. Acute effects of gentamicin on urinary electrolyte excretion in neonates. Pediatr Nephrol 2004, 19, 322–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giapros, V.; Papadimitriou, P.; Challa, A.; Andronikou, S. The effect of intrauterine growth retardation on renal function in the first two months of life. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007, 22, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, F.; Petersen, D.; De Coppi, P.; Eaton, S. Effect of sodium deficiency on growth of surgical infants: a retrospective observational study. Pediatr Surg Int 2014, 30, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knepper, C.; Ellemunter, H.; Eder, J.; Niedermayr, K.; Haerter, B.; Hofer, P.; Scholl-Bürgi, S.; Müller, T.; Heinz-Erian, P. Low sodium status in cystic fibrosis-as assessed by calculating fractional Na(+) excretion-is associated with decreased growth parameters. J Cyst Fibros 2016, 15, 400–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrenkranz, R.A.; Dusick, A.M.; Vohr, B.R.; Wright, L.L.; Wrage, L.A.; Poole, W.K. Growth in the neonatal intensive care unit influences neurodevelopmental and growth outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2006, 117, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sammallahti, S.; Kajantie, E.; Matinolli, H.M.; Pyhälä, R.; Lahti, J.; Heinonen, K.; Lahti, M.; Pesonen, A.K.; Eriksson, J.G.; Hovi, P.; et al. Nutrition after preterm birth and adult neurocognitive outcomes. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0185632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haycock, G.B. The influence of sodium on growth in infancy. Pediatric Nephrology 1993, 7, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCauley, H.A. Enteroendocrine Regulation of Nutrient Absorption. The Journal of Nutrition 2020, 150, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isemann, B.; Mueller, E.W.; Narendran, V.; Akinbi, H. Impact of Early Sodium Supplementation on Hyponatremia and Growth in Premature Infants: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2016, 40, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segar, J.L.; Grobe, C.C.; Grobe, J.L. Maturational changes in sodium metabolism in periviable infants. Pediatr Nephrol 2021, 36, 3693–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fine, B.P.; Ty, A.; Lestrange, N.; Levine, O.R. Sodium deprivation growth failure in the rat: alterations in tissue composition and fluid spaces. J Nutr 1987, 117, 1623–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohrscheib, M.; Sam, R.; Raj, D.S.; Argyropoulos, C.P.; Unruh, M.L.; Lew, S.Q.; Ing, T.S.; Levin, N.W.; Tzamaloukas, A.H. Edelman Revisited: Concepts, Achievements, and Challenges. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021, 8, 808765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattineni, J.; Baum, M. Developmental changes in renal tubular transport-an overview. Pediatr Nephrol 2015, 30, 2085–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dahhan, J.; Haycock, G.B.; Nichol, B.; Chantler, C.; Stimmler, L. Sodium homeostasis in term and preterm neonates. III. Effect of salt supplementation. Archives of Disease in Childhood 1984, 59, 945–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EKBLAD, H.; KERO, P.; TAKALA, J.; KORVENRANTA, H.; VÄLIMÄKI, I. Water, Sodium and Acid-Base Balance in Premature Infants: Therapeutical Aspects. Acta Paediatrica 1987, 76, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffer, S.G.; Meade, V.M. Sodium balance and extracellular volume regulation in very low birth weight infants. The Journal of Pediatrics 1989, 115, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayisi, R.K.; Mbiti, M.J.; Musoke, R.N.; Orinda, D.A. Sodium supplementation in very low birth weight infants fed on their own mothers milk I: Effects on sodium homeostasis. East Afr Med J 1992, 69, 591–595. [Google Scholar]

- Vanpée, M.; Herin, P.; Broberger, U.; Aperia, A. Sodium supplementation optimizes weight gain in preterm infants. Acta Paediatrica 1995, 84, 1312–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnoll, G.; Bétrémieux, P.; Modi, N. Randomised controlled trial of postnatal sodium supplementation on body composition in 25 to 30 week gestational age infants. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2000, 82, F24–F28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, C.; Castillo, D.; Valdés, B.D.; Castañeda, F. Effect of High Sodium Intake (5 mEq/kg/day) in Preterm Newborns (<35 Weeks Gestation) During the Initial 24 Hours of Life: A Non-Blinded Randomized Clinical Trial. Indian Pediatr 2023, 60, 146–148. [Google Scholar]

- Amiti, A.; Balakrishnan, U.; Devi, U.; Amboiram, P.; Salahudeen, A.G. Effect of early sodium supplementation on weight gain of very preterm infants: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Paediatr Open 2025, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, R.Y.; Clermont, D.; Williams, H.L.; Buchanan, P.; Hillman, N.H. Oral sodium supplementation on growth and hypertension in preterm infants: an observational cohort study. J Perinatol 2024, 44, 1515–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unal, S.; Arhan, E.; Kara, N.; Uncu, N.; Aliefendioğlu, D. Breast-feeding-associated hypernatremia: Retrospective analysis of 169 term newborns. Pediatrics International 2008, 50, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Dahhan, J.; Jannoun, L.; Haycock, G.B. Effect of salt supplementation of newborn premature infants on neurodevelopmental outcome at 10–13 years of age. Archives of Disease in Childhood - Fetal and Neonatal Edition 2002, 86, F120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, D.D.; Kuzmov, A.; Clausen, D.; Siu, A.; Robinson, C.A.; Kimler, K.; Meyers, R.; Shah, P. Osmolality of Commonly Used Oral Medications in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. The Journal of Pediatric Pharmacology and Therapeutics 2021, 26, 172–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latheef, F.; Wahlgren, H.; Lilja, H.E.; Diderholm, B.; Paulsson, M. The Risk of Necrotizing Enterocolitis following the Administration of Hyperosmolar Enteral Medications to Extremely Preterm Infants. Neonatology 2021, 118, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Risk factors for hyponatremia in preterm neonates.

Table 1.

Risk factors for hyponatremia in preterm neonates.

| Risk factor |

Comment |

| Prematurity |

|

| Inadequate Na intake |

Exclusive feeding with unfortified human milk Donor human milk or fortified breast milk still insufficient in sodium content Prolonged parenteral nutrition without adequate sodium supplementation |

| Fluid overload or excessive free water administration |

|

| Intraventricular hemorrhage |

|

| Sepsis, respiratory distress syndrome, or asphyxia |

|

| Necrotizing enterocolitis |

|

| Medications or other metabolic disturbances (diuretics, indomethacin, aminoglycosides, vancomycin, low serum phosphate) |

|

Table 2.

Sodium Supplementation Studies in Preterm Infants shown in chronological order.

Table 2.

Sodium Supplementation Studies in Preterm Infants shown in chronological order.

| Study |

Study Type |

GA (weeks) |

Population

(supplemented vs controls) |

Sodium Evaluation |

Sodium Supplementation |

Impact on Weight/Growth |

Complications/Safety |

| Al-Dahhan et al., 1984 |

Observational |

27–34 |

22 vs 24 |

Urine, serum, stool |

4–5 mEq/kg/day (day 4–14) |

Less weight loss; earlier regain |

No edema/hypernatremia; less hyponatremia |

| Ekblad et al., 1987 |

RCT |

<34 |

10 vs 10 |

Serum |

4 mEq/kg/day |

Similar early weight loss |

No complications |

| Shaffer et al., 1989 |

RCT |

700–1500 g |

N=20 |

Serum |

3 vs 1 mEq/kg/day |

No weight difference |

No complications |

| Ayisi et al., 1992 |

RCT |

VLBW 1001–1500 g |

41 vs 25 |

Serum, urine |

3 mEq/kg/day |

Increased weight, length, head circumference growth |

No hypernatremia |

| Vanpee et al., 1995 |

RCT |

29–34 |

10 vs 10 |

Urine |

4 mEq/kg/day (day 4–14) |

Controls had more weight loss |

No complications |

| Hartnoll et al., 2000 |

RCT |

25–30 |

24 early vs 22 delayed |

Serum |

4 mEq/kg/day early vs delayed |

No difference in birtweight regain |

Early supplementation increased oxygen need |

| Isemann et al., 2016 |

RCT |

<32 |

27 vs 26 |

— |

4 mEq/kg/day (day 7–35) |

Decreased growth failure |

No major complications |

| Segar et al., 2018 |

Observational (historical cohort) |

26–29 |

40 vs 50 |

Urine |

4 mEq/kg/day; additionally 2 mEq/kg/day if low urine Na |

Increased weight Z-score (0.32 vs –0.01) |

No respiratory differences |

| Sanchez et al., 2023 |

RCT |

<35 |

19 vs 23 |

Serum |

5 mEq/kg/day |

Decreased weight loss 48–72h |

No significant differences between groups |

| Petersen et al., 2024 |

Observational |

22–32 |

N=821 |

Serum, urine |

Variable |

Increased weight & head circumference growth |

No increased hypertention odds |

| Amiti et al., 2025 |

Double-blind RCT |

25–30 |

52 vs 52 |

Serum |

4 mEq/kg/day |

Increased weight gain velocity (18.0 vs 14.4 g/kg/day) |

No adverse events |

| Stalter et al., 2025 |

Retrospective cohort |

26–33 |

26-29 weeks: 225 vs 157

30-33 weeks: 157 vs 153 |

Urine |

4 mEq/kg/day; +2 mEq/kg/day if low |

Increased weight Z-score (26–29 wks)

No impact on growth on 30–33 wks |

No increased hypertension, NEC, bronchopulmonary dysplasia |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).