Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Circadian Emission of VOC in Flowers of J. sambac Dominated by Terpenoids

3.2. Identifying and Cloning of Candidate TPS Genes expressed in Petals

3.3. Subcellular Localization of the Four Terpene Synthase Proteins

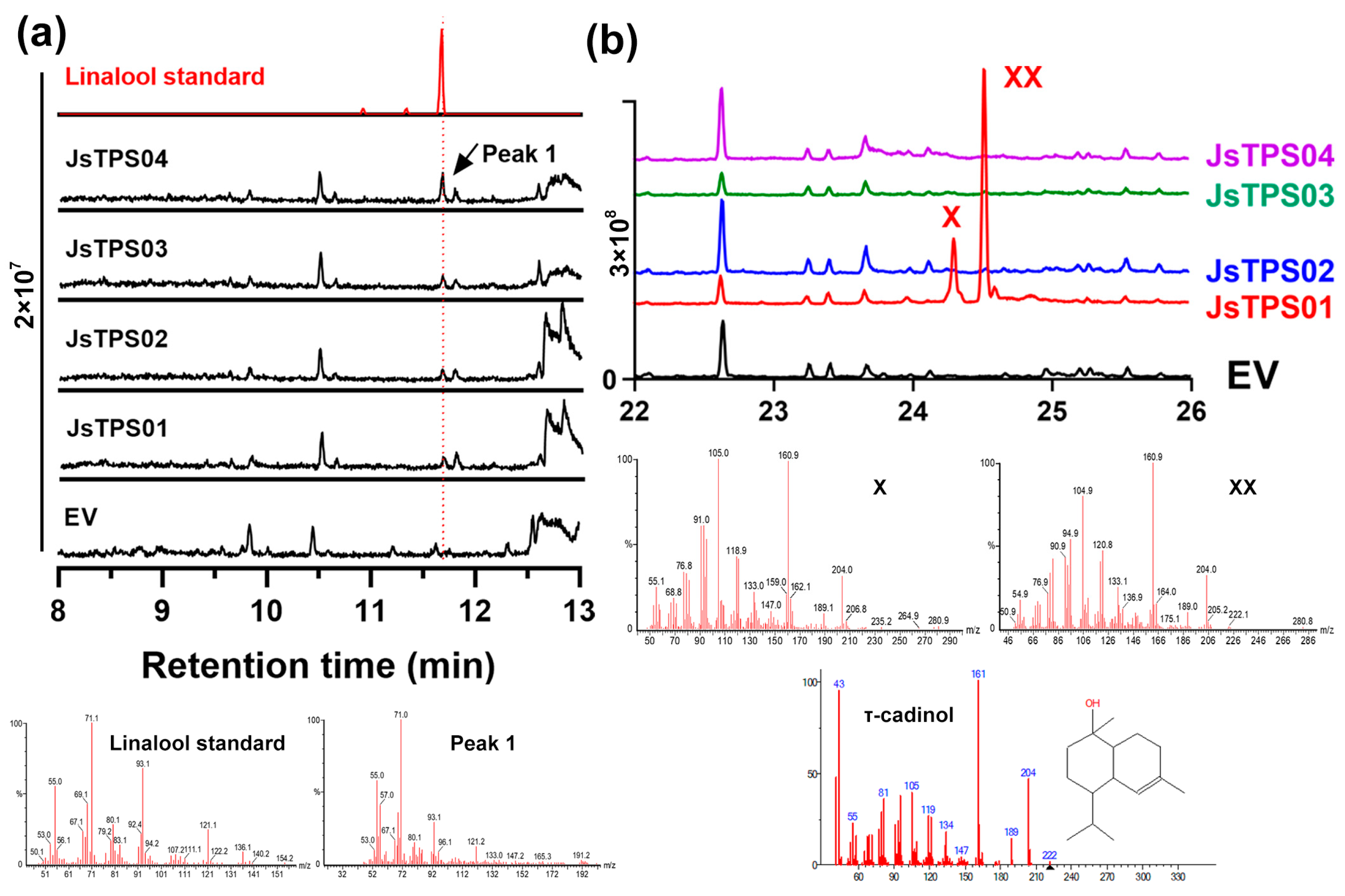

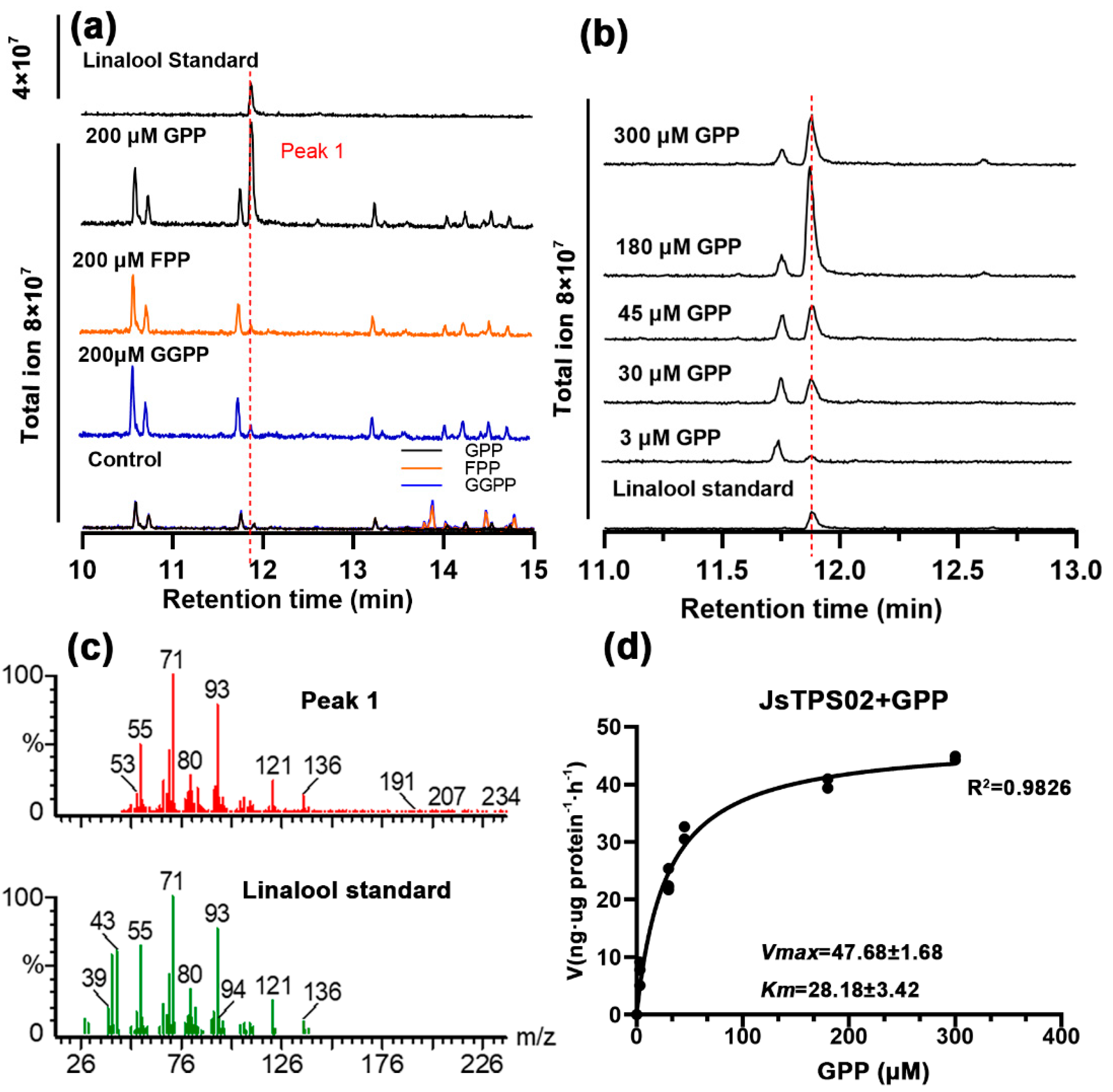

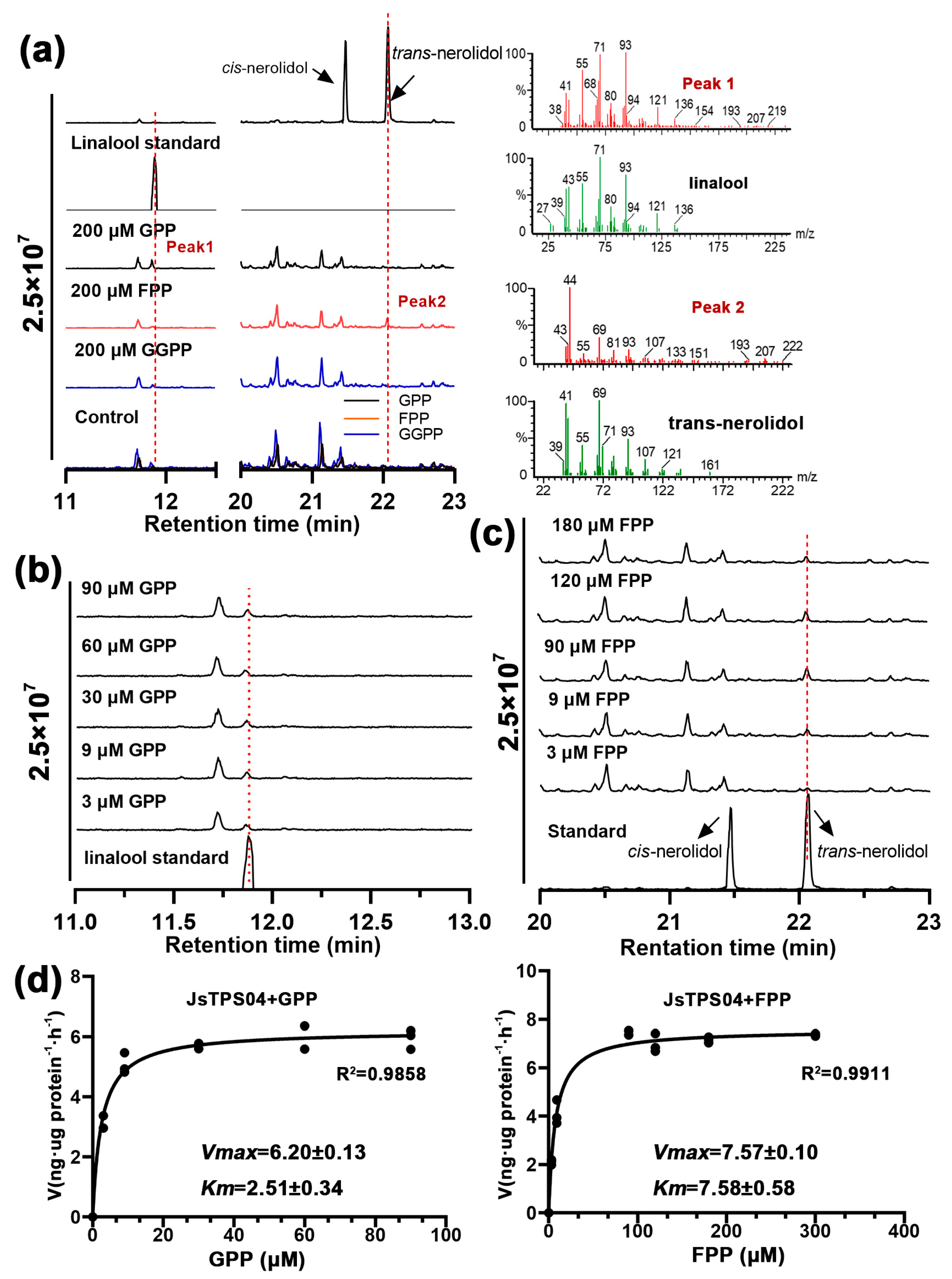

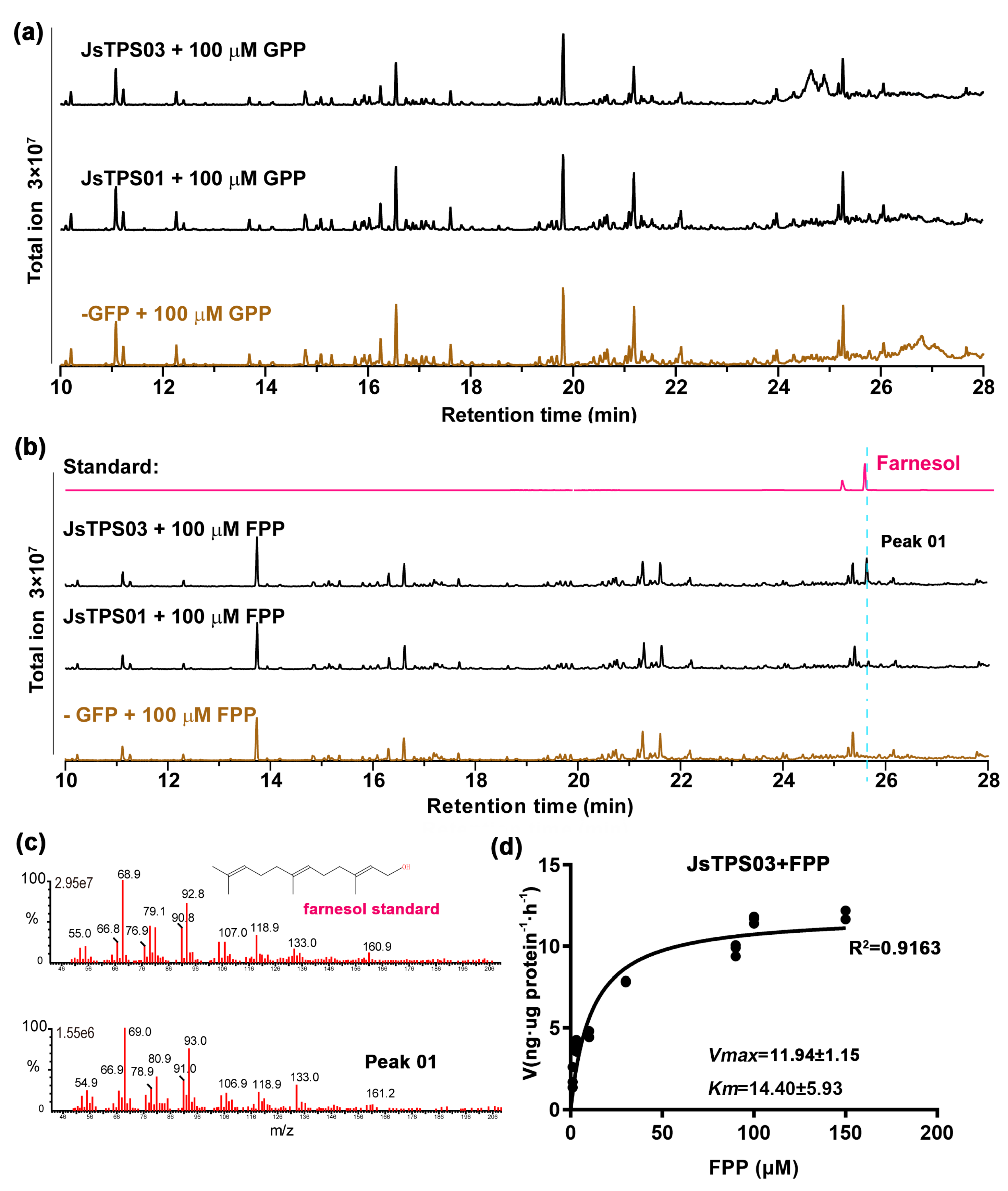

3.4. Enzyme Activities of the Four Jasminum Terpene synthase Proteins

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pichersky, E. and Lewinsohn, E., Convergent Evolution in Plant Specialized Metabolism. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2011. 62,549-566. [CrossRef]

- Mithöfer, A. and Boland, W., Plant Defense Against Herbivores: Chemical Aspects. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2012. 63,431-450. [CrossRef]

- Booij-James, I.S., Dube, S.K., Jansen, M.A., Edelman, M., and Mattoo, A.K., Ultraviolet-B radiation impacts light-mediated turnover of the photosystem II reaction center heterodimer in Arabidopsis mutants altered in phenolic metabolism. Plant Physiol 2000. 124(3),1275-84. 3. [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, J.T., Tollsten, L., and Bergström, L.G., Floral scents—a checklist of volatile compounds isolated by head-space techniques. Phytochemistry 1993. 33(2),253-280. [CrossRef]

- Amrad, A., Moser, M., Mandel, T., de Vries, M., Schuurink, R.C., Freitas, L., and Kuhlemeier, C., Gain and Loss of Floral Scent Production through Changes in Structural Genes during Pollinator-Mediated Speciation. Curr Biol 2016. 26(24),3303-3312. [CrossRef]

- Dixon, R.A. and Strack, D., Phytochemistry meets genome analysis, and beyond. Phytochemistry 2003. 62(6),815-6. 62, 6, 815–6. [CrossRef]

- Milo, R. and Last, R.L., Achieving Diversity in the Face of Constraints: Lessons from Metabolism. Science 2012. 336(6089),1663-1667. [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.-K., Philippe, R.N., and Noel, J.P., The Rise of Chemodiversity in Plants. Science 2012. 336(6089),1667-1670. [CrossRef]

- Leong, B.J. and Last, R.L., Promiscuity, impersonation and accommodation: evolution of plant specialized metabolism. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2017. 47,105-112. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., Honzatko, R.B., and Peters, R.J., Terpenoid synthase structures: a so far incomplete view of complex catalysis. Natural Product Reports 2012. 29(10),1153-1175. 10. [CrossRef]

- Christianson, D.W., Structural and Chemical Biology of Terpenoid Cyclases. Chem Rev 2017. 117(17),11570-11648. 17.

- Takahashi, S. and Koyama, T., Structure and function of cis-prenyl chain elongating enzymes. The Chemical Record 2006. 6(4),194-205. 4.

- Hemmerlin, A., Harwood, J.L., and Bach, T.J., A raison d’être for two distinct pathways in the early steps of plant isoprenoid biosynthesis? Progress in Lipid Research 2012. 51(2),95-148. 2. [CrossRef]

- Liang, P.-H., Ko, T.-P., and Wang, A.H.J., Structure, mechanism and function of prenyltransferases. European journal of biochemistry 2002. 269(14),3339-3354. 14.

- Kharel, Y. and Koyama, T., Molecular Analysis of cis-Prenyl Chain Elongating Enzymes. ChemInform 2003. 34(17). [CrossRef]

- Hamberger, B. and Bak, S., Plant P450s as versatile drivers for evolution of species-specific chemical diversity. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2013. 368(1612),20120426. [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, A. and Hamberger, B., P450s controlling metabolic bifurcations in plant terpene specialized metabolism. Phytochem Rev 2018. 17(1),81-111. [CrossRef]

- Karunanithi, P.S. and Zerbe, P., Terpene Synthases as Metabolic Gatekeepers in the Evolution of Plant Terpenoid Chemical Diversity. Frontiers in Plant Science 2019. Volume 10 - 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pichersky, E. and Gershenzon, J., The formation and function of plant volatiles: perfumes for pollinator attraction and defense. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2002. 5(3),237-243. [CrossRef]

- Magnard, J.-L., Roccia, A., Caissard, J.-C., Vergne, P., Sun, P., Hecquet, R., Dubois, A., Hibrand-Saint Oyant, L., Jullien, F., Nicolè, F., Raymond, O., Huguet, S., Baltenweck, R., Meyer, S., Claudel, P., Jeauffre, J., Rohmer, M., Foucher, F., Hugueney, P., Bendahmane, M., and Baudino, S., Biosynthesis of monoterpene scent compounds in roses. Science 2015. 349(6243),81-83. [CrossRef]

- Boutanaev, A.M., Moses, T., Zi, J., Nelson, D.R., Mugford, S.T., Peters, R.J., and Osbourn, A., Investigation of terpene diversification across multiple sequenced plant genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015. 112(1),E81-8. [CrossRef]

- Beran, F., Rahfeld, P., Luck, K., Nagel, R., Vogel, H., Wielsch, N., Irmisch, S., Ramasamy, S., Gershenzon, J., Heckel, D.G., and Köllner, T.G., Novel family of terpene synthases evolved from trans-isoprenyl diphosphate synthases in a flea beetle. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016. 113(11),2922-2927. 11. [CrossRef]

- Jia, Q., Li, G., Köllner, T.G., Fu, J., Chen, X., Xiong, W., Crandall-Stotler, B.J., Bowman, J.L., Weston, D.J., Zhang, Y., Chen, L., Xie, Y., Li, F.-W., Rothfels, C.J., Larsson, A., Graham, S.W., Stevenson, D.W., Wong, G.K.-S., Gershenzon, J., and Chen, F., Microbial-type terpene synthase genes occur widely in nonseed land plants, but not in seed plants. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016. 113(43),12328-12333. [CrossRef]

- Alicandri, E., Paolacci, A.R., Osadolor, S., Sorgonà, A., Badiani, M., and Ciaffi, M., On the Evolution and Functional Diversity of Terpene Synthases in the Pinus Species: A Review. J Mol Evol 2020. 88(3),253-283. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F. and Pichersky, E., The complete functional characterisation of the terpene synthase family in tomato. New Phytologist 2020. 226(5),1341-1360. [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N., & Pichersky, E, Biology of Floral Scent. 1st Edition ed. 2006, Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Dudareva, N., Klempien, A., Muhlemann, J.K., and Kaplan, I., Biosynthesis, function and metabolic engineering of plant volatile organic compounds. New Phytol 2013. 198(1),16-32. 1. [CrossRef]

- Schiestl, F.P., Ecology and evolution of floral volatile-mediated information transfer in plants. New Phytologist 2015. 206(2),571-577. 2.

- Sas, C., Müller, F., Kappel, C., Kent, T.V., Wright, S.I., Hilker, M., and Lenhard, M., Repeated Inactivation of the First Committed Enzyme Underlies the Loss of Benzaldehyde Emission after the Selfing Transition in Capsella. Current Biology 2016. 26(24),3313-3319. 24. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Tholl, D., D'Auria, J.C., Farooq, A., Pichersky, E., and Gershenzon, J., Biosynthesis and emission of terpenoid volatiles from Arabidopsis flowers. Plant Cell 2003. 15(2),481-94.

- Tholl, D. and Lee, S., Terpene Specialized Metabolism in Arabidopsis thaliana. The Arabidopsis book / American Society of Plant Biologists 2011. 9,e0143. [CrossRef]

- Tholl, D., Chen, F., Petri, J., Gershenzon, J., and Pichersky, E., Two sesquiterpene synthases are responsible for the complex mixture of sesquiterpenes emitted from Arabidopsis flowers. The Plant Journal 2005. 42(5),757-771. [CrossRef]

- Falara, V., Akhtar, T.A., Nguyen, T.T.H., Spyropoulou, E.A., Bleeker, P.M., Schauvinhold, I., Matsuba, Y., Bonini, M.E., Schilmiller, A.L., Last, R.L., Schuurink, R.C., and Pichersky, E., The Tomato Terpene Synthase Gene Family. Plant Physiology 2011. 157(2),770-789. [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N., Raguso, R.A., Wang, J., Ross, J.R., and Pichersky, E., Floral scent production in Clarkia breweri. III. Enzymatic synthesis and emission of benzenoid esters. Plant Physiol 1998. 116(2),599-604.

- Lücker, J., Bouwmeester, H.J., Schwab, W., Blaas, J., Van Der Plas, L.H.W., and Verhoeven, H.A., Expression of Clarkia S-linalool synthase in transgenic petunia plants results in the accumulation of S-linalyl-β-d-glucopyranoside. The Plant Journal 2001. 27(4),315-324.

- Tholl, D., Kish, C.M., Orlova, I., Sherman, D., Gershenzon, J., Pichersky, E., and Dudareva, N., Formation of Monoterpenes in Antirrhinum majus and Clarkia breweri Flowers Involves Heterodimeric Geranyl Diphosphate Synthases. The Plant Cell 2004. 16(4),977-992. 4. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, J., Mühlemann, J.K., Ruiz-Hernández, V., Dudareva, N., and Egea-Cortines, M., Phenotypic Space and Variation of Floral Scent Profiles during Late Flower Development in Antirrhinum. Frontiers in Plant Science 2016. Volume 7 - 2016. [CrossRef]

- Xu, H., Bohman, B., Wong, D.C.J., Rodriguez-Delgado, C., Scaffidi, A., Flematti, G.R., Phillips, R.D., Pichersky, E., and Peakall, R., Complex Sexual Deception in an Orchid Is Achieved by Co-opting Two Independent Biosynthetic Pathways for Pollinator Attraction. Current Biology 2017. 27(13),1867-1877.e5. [CrossRef]

- Chuang, Y.C., Hung, Y.C., Tsai, W.C., Chen, W.H., and Chen, H.H., PbbHLH4 regulates floral monoterpene biosynthesis in Phalaenopsis orchids. J Exp Bot 2018. 69(18),4363-4377. 18. [CrossRef]

- Ramya, M., Jang, S., An, H.-R., Lee, S.-Y., Park, P.-M., and Park, P.H., Volatile Organic Compounds from Orchids: From Synthesis and Function to Gene Regulation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2020. 21(3),1160. [CrossRef]

- Pichersky, E. and Raguso, R.A., Why do plants produce so many terpenoid compounds? New Phytologist 2018. 220(3),692-702. 3. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D. and Dommée, B., Sequential variation in the components of reproductive success in the distylous Jasminum fruticans (Oleaceae). Oecologia 1993. 94(4),480-487. 4. [CrossRef]

- QixiangYu, LixinRu, ChenshuangShuang, Fengjing, ChenhuiJie, LiuxinTong, JinyuYan, and DengyanMing, Identification of the FLA Gene Family and Functional Analysis ofJsFLA2 in Jasminum sambac. Scientia Agricultura Sinica 2025. 58(17),3516-3530.

- Bera, P., Kotamreddy, J.N., Samanta, T., Maiti, S., and Mitra, A., Inter-specific variation in headspace scent volatiles composition of four commercially cultivated jasmine flowers. Nat Prod Res 2015. 29(14),1328-35. [CrossRef]

- Bera, P., Mukherjee, C., and Mitra, A., Enzymatic production and emission of floral scent volatiles in Jasminum sambac. Plant Science 2017. 256,25-38. [CrossRef]

- Pragadheesh, V.S., Chanotiya, C.S., Rastogi, S., and Shasany, A.K., Scent from Jasminum grandiflorum flowers: Investigation of the change in linalool enantiomers at various developmental stages using chemical and molecular methods. Phytochemistry 2017. 140,83-94. [CrossRef]

- Barman, M. and Mitra, A., Temporal relationship between emitted and endogenous floral scent volatiles in summer- and winter-blooming Jasminum species. Physiologia Plantarum 2019. 166(4),946-959. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Mostafa, S., Lu, Z., Du, R., Cui, J., Wang, Y., Liao, Q., Lu, J., Mao, X., Chang, B., Gan, Q., Wang, L., Jia, Z., Yang, X., Zhu, Y., Yan, J., and Jin, B., The Jasmine (Jasminum sambac) Genome Provides Insight into the Biosynthesis of Flower Fragrances and Jasmonates. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics 2023. 21(1),127-149. [CrossRef]

- Qi, X., Wang, H., Liu, S., Chen, S., Feng, J., Chen, H., Qin, Z., Chen, Q., Blilou, I., and Deng, Y., The chromosome-level genome of double-petal phenotype jasmine provides insights into the biosynthesis of floral scent. Horticultural Plant Journal 2024. 10(1),259-272. [CrossRef]

- Fan, W., Liao, Z., Gu, M., Zhang, Y., Lei, W., Zhang, Y., Li, H., Yan, J., Xiao, Y., Lin, H., Jin, S., Yu, Y., Fang, J., Ye, N., and Wang, P., Pan-Genome of Jasminum sambac Reveals the Genetic Diversity of Different Petal Morphology and Aroma-Related Genes. Mol Ecol Resour 2025. 25(7),e70013. [CrossRef]

- Qi, X., Wang, H., Chen, S., Feng, J., Chen, H., Qin, Z., Blilou, I., and Deng, Y., The genome of single-petal jasmine (Jasminum sambac) provides insights into heat stress tolerance and aroma compound biosynthesis. Frontiers in Plant Science 2022. Volume 13 - 2022. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S., Ding, Y., Sun, J., Zhang, Z., Wu, Z., Yang, T., Shen, F., and Xue, G., A high-quality genome assembly of Jasminum sambac provides insight into floral trait formation and Oleaceae genome evolution. Molecular Ecology Resources 2022. 22(2),724-739. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Fang, J., Lin, H., Yang, W., Yu, J., Hong, Y., Jiang, M., Gu, M., Chen, Q., Zheng, Y., Liao, Z., Chen, G., Yang, J., Jin, S., Zhang, X., and Ye, N., Genomes of single- and double-petal jasmines (Jasminum sambac) provide insights into their divergence time and structural variations. Plant Biotechnol J 2022. 20(7),1232-1234. [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Mostafa, S., Lu, Z., Du, R., Cui, J., Wang, Y., Liao, Q., Lu, J., Mao, X., Chang, B., Wang, L., Jia, Z., Yang, X., Zhu, Y., Yan, J., and Jin, B., The jasmine ( Jasminum sambac ) genome and flower fragrances. bioRxiv 2020.

- Hong Ya-ping, Chen Xue-jin, Wang Peng-jie, GU Meng-ya, GAO Ting, YE Nai-xing. Transcriptome Identification of Terpenoid Synthase Genes in Jasminum sambac and Their Expressions Responding to Exogenous Hormones[J]. Biotechnology Bulletin, 2022, 38(3): 41-49.

- Kim, D., Langmead, B., and Salzberg, S.L., HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods 2015. 12(4),357-60. [CrossRef]

- Wu, T., Hu, E., Xu, S., Chen, M., Guo, P., Dai, Z., Feng, T., Zhou, L., Tang, W., Zhan, L., Fu, X., Liu, S., Bo, X., and Yu, G., clusterProfiler 4.0: A universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. The Innovation 2021. 2(3),100141. [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M., Inze, D., and Depicker, A., GATEWAY vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends in plant science 2002. 7(5),193-5. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., Liu, Z., Lyu, M., Yuan, Y., and Wu, B., Characterization of JsWOX1 and JsWOX4 during Callus and Root Induction in the Shrub Species Jasminum sambac. Plants (Basel, Switzerland) 2019. 8(4). [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Li, M., Knyaz, C., and Tamura, K., MEGA X: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis across Computing Platforms. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2018. 35(6),1547-1549. [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D. and Livak, K.J., Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nature Protocols 2008. 3(6),1101-1108. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P., Wei, P., Niu, F., Liu, X., Zhang, H., Lyu, M., Yuan, Y., and wu, B., Cloning and Functional Assessments of Floral-Expressed SWEET Transporter Genes from Jasminum sambac. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019. 20,4001. [CrossRef]

- Wu, B., Rambow, J., Bock, S., Holm-Bertelsen, J., Wiechert, M., Soares, A.B., Spielmann, T., and Beitz, E., Identity of a Plasmodium lactate/H+ symporter structurally unrelated to human transporters. Nature Communications 2015. 6(1),6284. [CrossRef]

- Gietz, R.D. and Schiestl, R.H., High-efficiency yeast transformation using the LiAc/SS carrier DNA/PEG method. Nat Protoc 2007. 2(1),31-4.

- Whittington, D.A., Wise, M.L., Urbansky, M., Coates, R.M., Croteau, R.B., and Christianson, D.W., Bornyl diphosphate synthase: Structure and strategy for carbocation manipulation by a terpenoid cyclase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002. 99(24),15375-15380. [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, D.C., Youn, B., Zhao, Y., Santhamma, B., Coates, R.M., Croteau, R.B., and Kang, C., Structure of limonene synthase, a simple model for terpenoid cyclase catalysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007. 104(13),5360-5365. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.-Y., Jin, J., Sarojam, R., and Ramachandran, S., A Comprehensive Survey on the Terpene Synthase Gene Family Provides New Insight into Its Evolutionary Patterns. Genome Biology and Evolution 2019. 11(8),2078-2098. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T., Nagasawa, N., Iwamatsu, A., Bogaki, T., Tamai, Y., and Hamachi, M., Molecular cloning, sequence analysis, and expression of the yeast alcohol acetyltransferase gene. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 1994. 60(8),2786-2792. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.S., Wu, C.L., Chang, H.T., Kao, Y.T., and Chang, S.T., Antitermitic and antifungal activities of essential oil of Calocedrus formosana leaf and its composition. J Chem Ecol 2004. 30(10),1957-67. [CrossRef]

- Ren, F., Mao, H., Liang, J., Liu, J., Shu, K., and Wang, Q., Functional characterization of ZmTPS7 reveals a maize τ-cadinol synthase involved in stress response. Planta 2016. 244(5),1065-1074. [CrossRef]

- Gennadios, H.A., Gonzalez, V., Costanzo, L.D., Li, A., and Christianson, D.W., Crystal Structure of (+)-δ-Cadinene Synthase from Gossypium arboreum and Evolutionary Divergence of Metal Binding Motifs for Catalysis. Biochemistry 2009. 48(26),6175-6183. [CrossRef]

- Jullien, F., Moja, S., Bony, A., Legrand, S., Petit, C., Benabdelkader, T., Poirot, K., Fiorucci, S., Guitton, Y., Nicolè, F., Baudino, S., and Magnard, J.-L., Isolation and functional characterization of a τ-cadinol synthase, a new sesquiterpene synthase from Lavandula angustifolia. Plant Molecular Biology 2014. 84(1),227-241. [CrossRef]

- Raguso, R.A. and Pichersky, E., New Perspectives in Pollination Biology: Floral Fragrances. A day in the life of a linalool molecule: Chemical communication in a plant-pollinator system. Part 1: Linalool biosynthesis in flowering plants. Plant Species Biology 1999. 14(2),95-120. [CrossRef]

- Farré-Armengol, G., Fernández-Martínez, M., Filella, I., Junker, R.R., and Peñuelas, J., Deciphering the Biotic and Climatic Factors That Influence Floral Scents: A Systematic Review of Floral Volatile Emissions. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020. Volume 11 - 2020. [CrossRef]

- Dudareva, N., Cseke, L., Blanc, V.M., and Pichersky, E., Evolution of floral scent in Clarkia: novel patterns of S-linalool synthase gene expression in the C. breweri flower. Plant Cell 1996. 8(7),1137-48. [CrossRef]

- Aprotosoaie, A.C., Hăncianu, M., Costache, I.-I., and Miron, A., Linalool: a review on a key odorant molecule with valuable biological properties. Flavour and Fragrance Journal 2014. 29(4),193-219.

- Yang, T., Stoopen, G., Thoen, M., Wiegers, G., and Jongsma, M.A., Chrysanthemum expressing a linalool synthase gene ‘smells good’, but ‘tastes bad’ to western flower thrips. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2013. 11(7),875-882. 7.

- Green, S., Friel, E.N., Matich, A., Beuning, L.L., Cooney, J.M., Rowan, D.D., and MacRae, E., Unusual features of a recombinant apple α-farnesene synthase. Phytochemistry 2007. 68(2),176-188. [CrossRef]

- Manczak, T. and Simonsen, H.T., Insight into Biochemical Characterization of Plant Sesquiterpene Synthases. Anal Chem Insights 2016. 11(Suppl 1),1-7. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S.R., Bhat, W.W., Sadre, R., Miller, G.P., Garcia, A.S., and Hamberger, B., Promiscuous terpene synthases from Prunella vulgaris highlight the importance of substrate and compartment switching in terpene synthase evolution. New Phytologist 2019. 223(1),323-335. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).