Research in Context

Evidence Before this Study

We searched PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar for studies published between Jan 1, 2000, and Dec 31, 2024, using the terms “menopause”, “perimenopause”, “Malaysia”, “Asia”, “qualitative”, and “women’s health”. Previous research in Malaysia has largely been cross-sectional, focusing on symptom prevalence, age of onset, or use of complementary medicine. While some studies have highlighted ethnic differences in symptom expression, there remains little understanding of how sociocultural norms, language, and workplace structures shape women’s experiences. Crucially, few studies have examined the colloquial ways women articulate their symptoms or explored how these affect care-seeking behaviour and policy engagement.

Added Value of this Study

To our knowledge, this is the first qualitative study to apply an equity-oriented framework to menopause in Malaysia. By incorporating narratives from Malay, Chinese, Indian, and Indigenous women, the MARIE WP2a chapter highlights how symptoms are not only biological but filtered through cultural interpretations, religious practice, and linguistic expression. Colloquial terms such as “rasa panas mendadak” (sudden heat) and “susahlah tidur” (can’t sleep) demonstrate how women describe menopause in everyday contexts, often in ways that remain invisible in biomedical discourse. The study reveals that workplace stigma, cost constraints, and policy gaps exacerbate inequities, while women’s strong self-management capacity reflects resilience in the face of systemic under-provision.

Implications of All the Available Evidence

These findings suggest that menopause care in Malaysia requires a paradigm shift from biomedical symptom management towards culturally sensitive, equity-driven strategies. National guidelines should be expanded to include faith-sensitive counselling, multilingual resources, and greater involvement of primary-care providers in initiating treatment such as HRT. At the workplace level, menopause must be recognised as a legitimate occupational health issue warranting supportive policies. Public education efforts should draw on everyday language to improve reach and relevance. Ultimately, embedding women’s lived experiences into clinical practice, health systems, and policy frameworks will be essential to ensuring that the growing population of post-menopausal women in Malaysia can achieve equitable health and quality of life.

Introduction

Menopause marks a key stage in a woman’s life course, defined clinically by the permanent cessation of menstruation for twelve consecutive months in the absence of other causes1,2. It is preceded by perimenopause, a phase characterised by irregular cycles and fluctuating symptoms, and followed by post-menopause, during which long-term health risks emerge3,4. Globally, the average age at natural menopause is between 49 and 52 years, while in Malaysia, current data suggests a mean age of approximately 50 years5,6. With female life expectancy exceeding 77 years, many Malaysian women will spend one-third of their lives beyond menopause7. The impact of declining ovarian function extends far beyond reproduction, affecting cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, cognitive, and psychosocial health8. As such, the menopausal transition represents not only a biological milestone but also a stage of significant clinical and public health relevance.

The manifestations of perimenopause and menopause are highly variable, reflecting the interplay between hormonal decline, genetic predisposition, lifestyle and environmental influences. Vasomotor symptoms such as hot flushes and night sweats remain the most commonly reported globally, while mood changes, anxiety, irritability, and sleep disturbance, can substantially impair quality of life9,10. Urogenital atrophy leads to sexual dysfunction and urinary complaints, while reduced oestrogen accelerates risks of osteoporosis and cardiovascular diseases in later life11,12. However, cross-cultural differences shape both experience and interpretation. In Malaysia, the multi-ethnic composition has meant Malay, Chinese, Indian, and indigenous groups shape both symptom expression and the meanings attached to menopause often differently13-15. Cultural interpretations can frame menopause as natural and liberating or, conversely, as a marker of social decline, influencing whether women seek medical support, turn to complementary therapies, or remain silent about their symptoms.

Despite its widespread impact, menopause has received limited policy or service attention in Malaysia. Uptake of hormone replacement therapy (HRT), an effective treatment for vasomotor and urogenital symptoms, remains low due to fears of side effects, inconsistent counselling, and variability in clinician expertise16-18. Access to specialist care is uneven, leaving rural and indigenous communities at a particular disadvantage. Workplace recognition of menopause is minimal, leaving many women unsupported as symptoms affect productivity, attendance and career progression. Stigma and cultural taboos surrounding reproductive health reinforce silence in families, workplaces, and healthcare settings. National epidemiological data on symptom prevalence and care-seeking remain scarce, and little is known about how socioeconomic status, co-morbid conditions such as diabetes and hypertension, or geographical disparities shape the lived experience of menopause in Malaysia.

Rationale

Addressing the gaps in menopause research in Malaysia requires moving beyond epidemiological survey to explore women’s lived experiences, across diverse ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic settings. While the MARIE Malaysia chapter has provided valuable insights into age of onset and symptom prevalence, they do not reveal the social meanings, structural barriers, and cultural adaptations that shape how menopause is experienced and negotiated in daily life. The qualitative approach within the current work-package (WP2a) is therefore essential to understand how women articulate their symptoms, navigate between biomedical and traditional treatments, and encounter challenges in healthcare access and workplace equity. In Malaysia’s context, where cultural pluralism intersects with uneven health system distribution, such insights are vital to inform policy, design responsive clinical pathways, and shape public health messaging. Embedding women’s narratives at the centre of the MARIE Malaysia study ensures that the voices of women themselves guide the development of evidence-based, culturally sensitive strategies to improve menopausal care and equity across the life course.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

We conducted a qualitative study as part of the Malaysian arm of the MARIE WP2a project, a multi--country investigation into perimenopausal, menopausal, and post--menopausal health. The Malaysian context is characterised by a multi--ethnic and multi--religious population, comprising Malay, Chinese, Indian, and Indigenous groups, with diverse sociocultural beliefs influencing health--seeking behaviours. Healthcare is delivered through a mixed public–private system, with substantial urban–rural disparities in access, cost, and continuity of care.

Participants and Recruitment

Participants were biologically adult females above 18 years, and had experienced perimenopause, menopause, or post--menopause, whether natural, surgical, or medically induced. We sought diversity across age, ethnicity, religion, menopausal stage, geographical location, employment sector, and comorbidity status. Recruitment used purposive and snowball sampling via healthcare providers, community networks, and social media outreach. Eligible individuals provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Data Collection

Semi--structured interviews were conducted in English, Malay, or Mandarin, either face--to--face or via secure Microsoft Teams. An interview guide explored symptom experiences, health--seeking behaviours, healthcare interactions, workplace impact, social and family dynamics, and perceptions of policy support. Interviews lasted 45 to 90 minutes, were audio--recorded, transcribed verbatim, and translated into English where necessary. Field notes captured contextual observations, non--verbal cues, and reflexive insights.

Analytical Framework

Data were analysed using the Delanerolle & Phiri equity--oriented framework

19 in conjunction with reflexive thematic analysis (

Table 1). The framework comprises four stages as indicated in

Table 1.

Coding was conducted reflexively and iteratively using a structured codebook, auditable coding matrices, and version-controlled documents to maintain a transparent decision trail (including analytic memos and code–quote linkages). Peer debriefs were held at regular intervals to test alternative explanations and enhance credibility. A reflexivity statement documented researchers’ positionalities and how these might have influenced interpretation. All quotes were anonymised and tagged by participant ID.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval was granted by Medical Research & Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR ID 23-03581-PO8 (IIR)). All participants received study information sheets and provided written informed consent for participation and publication of anonymised quotes. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

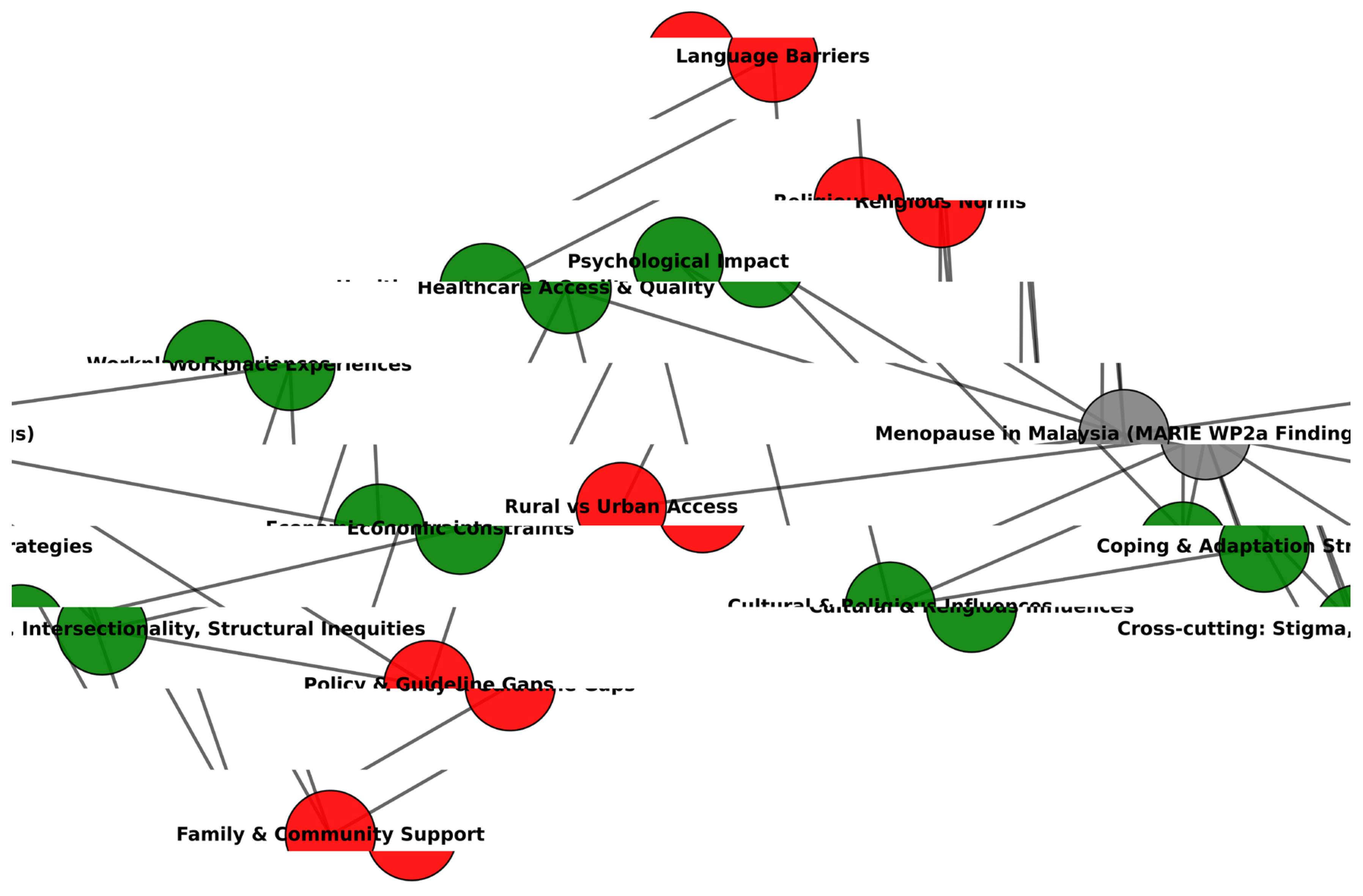

Eleven participants provided findings that illustrate menopause is shaped by intersecting cultural, social, and systemic factors rather than symptom biology alone (

Table 2). Women’s experiences reflected coping strategies such as prayer, exercise, and herbal remedies, alongside barriers in healthcare access, workplace recognition, and policy provision, as indicated in the thematic

Table 3. Economic constraints, language barriers, and rural-urban disparities compounded inequities, while religious and cultural norms strongly influenced how symptoms were understood, disclosed, and managed. These insights underscore the need for culturally competent counselling, workplace policies, and equity-focused national strategies to ensure menopause care is both accessible and meaningful in the Malaysian context.

Symptom Experiences and Trajectories

Across the sample, menopause was experienced along a continuum from minimal disruption to significant physical and psychological burden. Women with natural menopause commonly reported vasomotor symptoms such as hot flushes, night sweats, sleep disturbance, mood fluctuation, and musculoskeletal discomfort. In several accounts, genitourinary syndrome of menopause (GSM), including vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, urinary leakage, and vulval irritation, emerged as a persistent, often untreated concern. Surgical menopause cases described a more abrupt onset, with compounded fatigue, cognitive decline, and palpitations following hysterectomy and oophorectomy. Symptom severity often reflected underlying health conditions; multimorbidity, such as diabetes, hypertension, post-stroke sequelae, shaped functional capacity and care priorities. Notably, several participants reported that symptoms resolved or became less intrusive over time, but unaddressed sexual health changes, sleep problems, and joint pain remained.

“Stress about hot flushes.” (PID1)

“Sometimes… feeling hot at night.” (PID4)

“Kurang… lendir… rasa tidak selesa… ada sakit.” [Less… lubrication… not feeling comfortable… got pain.] (PID8)

“Now I have diabetes and hypertension… I’ve had laser treatment [for diabetic retinopathy].” (PID7)

“I didn’t really feel menopausal… just normal.” (PID10)

Coping Strategies and Self-Management

Coping responses were strongly shaped by personal beliefs, health literacy, and affordability. Many women adopted self-directed approaches, including exercise such as walking, Zumba, and dietary supplements, such as evening primrose oil and herbal remedies. In addition, religious practices such as zikir, prayer, scriptural reading, and seeking digital information were also used. Several avoided pharmacological interventions, particularly HRT, due to perceived cancer risks, cultural framing of hormones as “chemical,” or a view that mild symptoms did not warrant medical treatment. Cost was a determinant of discontinuing supplements for some, particularly post-retirement. Religious coping provided psychological stability for Muslim and Christian participants, while social and leisure activities mitigated isolation. Coping through selective emotional disclosure was common, reflecting workplace norms and cultural boundaries.

“Self-talk… Self-motivation… Zumba sometimes.” (PID1)

“When I feel stressed… I do zikir. It has helped a lot this past year.” (PID11)

“I don’t take anything at all.” (PID6)

“We used KY Jelly before… it helped.” (PID10)

“Saya tak suka ambil bahan kimia… teh herba chamomile… sangat membantu.” [I don’t like taking chemicals… chamomile herbal tea… really helps.] (PID8)

Community and Workplace Contexts

Community and workplace environments played pivotal roles in shaping menopause experiences. Supportive colleagues, particularly in smaller teams, offered flexibility, understanding, and rest breaks. However, workplace menopause policies were absent across sectors, and occupational adaptations depended on informal goodwill rather than formal entitlements. Women in healthcare roles often reported a lack of leadership awareness about menopause and limited organisational training. In some workplaces, menopausal symptoms intersected with corporate restructuring, relocation, or pandemic-related disruptions, amplifying stress and undermining morale. Ageist and gendered stereotypes, particularly in Chinese corporate settings, framed menopausal women as “difficult,” reinforcing stigma and discouraging disclosure. Beyond work, family played mixed roles: some provided emotional reciprocity and companionship; others avoided engagement when participants were “in a bad mood.”

“If they see I’m stressed… they tell me to rest first.” (PID11)

“Support is fine… but more humane… give us some leaves.” (PID4)

“Nobody talked about it openly.” (PID2)

“Ketua Unit pun tidak memahami… sepatutnya… mereka kena faham.” [Unit Heads don’t understand…supposedly …. they have to understand.] (PID8)

“Like an orphan” [during workplace restructuring]. (PID6)

Health System Interactions and Service Gaps

Healthcare engagement was typically reactive and symptom-triggered rather than preventive. Few participants reported being proactively asked about menopause in clinical settings, even when attending for chronic disease management. Menopause-specific services were rare; surgical cases described good oncology follow-up but no integrated menopause care. GSM and sexual health concerns were often undiscussed with clinicians, due to embarrassment, perceived triviality, or cultural modesty. Primary care rarely offered or discussed HRT, and several participants reported learning about menopause only after experiencing symptoms. Positive care experiences centred on trusted providers who offered advice or symptom relief. Structural barriers included incompatible clinic hours for working women, appointment booking requirements, regional inequities in surgical practice, and the absence of multidisciplinary menopause teams.

“No” [to receiving needed support from primary care]. (PID1)

“I only learned about it after experiencing it myself.” (PID11)

“We treat women in their 50s… but don’t ask about menopause.” (PID7)

“Everybody Googles… maybe it’s the right kind of information.” (PID2)

“Ubat ni (i.e., HRT) tak digunakan… dan tidak… dibincangkan.” [This medicine isn’t used… and it’s not… discussed.] (PID8)

Policy Awareness and Advocacy

Participants consistently expressed a desire for systemic change. At the policy level, they called for public awareness campaigns, community-level education, workplace menopause policies, and integration of menopause into chronic disease care. Recommendations included dedicated menopause clinics in both public and private sectors, multidisciplinary teams incorporating mental health professionals, targeted courses for women in midlife, and mass media outreach to help partners and families understand menopause. Digital peer-support platforms were suggested as accessible, stigma-reducing spaces. Women in healthcare roles emphasised the need for continuing medical education (CME) for managers and clinicians to improve menopause literacy and patient–provider communication. Policy advocacy was grounded in equity concerns, ensuring that women with low education, rural residence, or limited health literacy could access tailored support.

“Give awareness talk.” (PID1)

“Arrange a course to help them better understand their menopausal condition.” (PID3)

“Helpful to have some articles in the newspaper so that more women can gain awareness.” (PID4)

“Emotional support is very important… if our emotions are okay, we can work.” (PID11)

“Clinics should tell clients about menopause so they are ready.” (PID6)

Cross-Cutting Equity Themes

Analysis through the Delanerolle & Phiri equity-oriented framework revealed intersecting determinants across all domains. There is a constellation of intersecting determinants that extend beyond the biological manifestations of menopause, underscoring the importance of structural, cultural, and economic contexts in shaping women’s health outcomes.

Knowledge and information asymmetry were evident even among healthcare professionals, indicating that occupational proximity to health services does not guarantee menopause literacy. The latter aligns with global evidence that formal medical training often neglects menopause, with limited curricular emphasis on HRT safety, indications, and alternatives. Reliance on peers or the internet as primary information sources risks perpetuating misinformation, reinforcing self-management approaches that may be suboptimal or delaying care-seeking.

The cultural-religious interface illustrates how physiological changes intersect with faith-based practices and social norms. Prolonged or irregular bleeding disrupted religious rituals, especially in Islam, where menstruation affects prayer eligibility, contributing to heightened anxiety. Simultaneously, modesty norms restricted the disclosure of sexual health concerns, a pattern documented in other conservative settings. Such constraints create a dual-layered invisibility, where both the symptom and its cultural significance remain under-addressed in health encounters limiting the opportunity for culturally competent care.

Economic determinants played a subtler but important role. Public healthcare in Malaysia is heavily subsidised; however, indirect costs including loss of income from time off work to attend a congested clinic, transportation, and the purchase of over-the-counter supplements influence health decisions. Women reported discontinuing supplements or forgoing private consultations due to cost. This reflects broader findings from low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) contexts where out-of-pocket expenditure is a major determinant of health-seeking behaviour, and where menopause-related care is rarely prioritised in household health budgets.

Gender norms and marital expectations emerged as a salient driver of sexual health inequities. Dyspareunia and low libido were sometimes negotiated within frameworks of marital obligation, with women feeling unable to refuse intimacy despite discomfort. Such dynamics echo feminist analyses of reproductive health, where social scripts of marital duty constrain women’s bodily autonomy. The absence of routine enquiry about sexual function in primary care settings compounds the problem, leaving symptoms untreated and the relational dimension unaddressed.

Workplace inequities were characterised by an absence of menopause-informed leadership and policy. In practice, this meant that symptom management (e.g., coping with fatigue, sleep disruption, or vasomotor episodes) relied on the goodwill of colleagues rather than formal accommodations. This mirrors global literature showing that, in the absence of policy frameworks, women adapt at an individual level rather than organisations adapting to their needs. The lack of structural recognition contributes to presenteeism, reduced productivity, and attrition, with implications for workforce retention.

Geographic service disparities highlighted how access to surgical and specialist menopause services was concentrated in urban centres. Participants in smaller regional hospitals reported fewer options for ovarian-sparing surgery or access to dedicated menopause clinics, reflecting both infrastructure and workforce distribution imbalances. Such inequities are consistent with the Malaysian Ministry of Health’s own assessments of urban–rural service gaps and mirror patterns in other LMICs where reproductive health subspecialties are unevenly distributed.

Collectively, these determinants illustrate that menopause inequities are not simply a by-product of symptom variability but are actively shaped by socio-structural conditions. Addressing them requires multi-level interventions: embedding holistic care of menopause in medical curricula, integrating cultural and religious competence into care pathways, ensuring equitable resource distribution, and enacting workplace and public health policies that acknowledge menopause as a legitimate and significant health phase.

“Penting… ramai tak tahu… perlu beri ilmu kepada mereka.” [Important… many don’t know… need to give them knowledge.] (PID8)

“We agreed to stop… it was uncomfortable, and my husband isn’t well.” (PID10)

“Period tak berhenti, ganggu ibadah, nak solat…” [Period didn’t stop, disrupted worship, wanting to pray…] (PID8)

“No workplace policy… we didn’t get to discuss that here.” (PID4)

Integrative Interpretation

The findings reveal that menopause in Malaysia is not a uniform clinical event but a socially mediated transition shaped by intersecting biological, cultural, and systemic determinants. Women’s narratives show that while some describe the process as “just normal,” others highlight distress through colloquial terms such as

“rasa panas mendadak” (sudden feeling of heat),

“susahlah tidur” (difficult to sleep), or

“maranduttee poren” (I keep forgetting), which capture lived realities often invisible in formal health discourse (

Table 4). Such language underscores both the normalisation of symptoms and the silence surrounding intimate issues like vaginal dryness or painful sex, which remain unspoken in clinical settings due to modesty norms, embarrassment, or fear of being dismissed. The Delanerolle and Phiri equity framework highlights that these experiences are not only shaped by symptom severity but also by health literacy gaps, workplace stigma, religious expectations, and policy omissions that collectively determine whether women seek care, rely on self-management, or disengage from health services.

Despite strong self-management capacities, women’s reliance on peers, the internet, or traditional remedies reflects systemic under-provision and a lack of culturally attuned medical dialogue. Even those with multimorbidity reported menopause as absent from routine consultations, representing missed opportunities for preventive care. Workplace cultures ranged from supportive gestures of flexibility to dismissive stereotypes of women as “difficult,” with the absence of formal menopause policies reinforcing inequities. Public health communication remains fragmented, often inaccessible in colloquial Malay, Tamil, or Mandarin, leaving women to translate medicalised concepts into their own everyday language.

These insights point to an urgent need for multi-level reform. Menopause should be embedded into chronic disease care, supported by culturally competent counselling that recognises how women themselves describe and interpret symptoms. Workplace and policy interventions must move beyond token awareness to structural protections and tailored education, delivered in multiple languages and formats. Without such changes, the disproportionate burden of navigating menopause will remain on women, entrenching inequities across health, work, and daily life.

Discussion

This qualitative study of the Malaysian arm of the MARIE WP2a study demonstrates that menopause is not a uniform biological event but a socially mediated transition shaped by intersecting determinants at individual, community, health system, and policy levels. Women’s accounts revealed wide variability in symptom burden from negligible disruption to persistent, untreated genitourinary and sleep disturbances yet the trajectory of experience was consistently influenced by cultural norms, religious practices, workplace environments, and service accessibility. The Delanerolle & Phiri equity-oriented framework elucidates how structural barriers such as informational asymmetry, service gaps, and geographic disparities interact with gender norms and marital expectations to either facilitate adaptation or entrench unmet needs. Importantly, the findings challenge assumptions that healthcare workers or urban residents are insulated from menopause-related inequities; even within these groups, limited menopause literacy, reliance on informal advice, and avoidance of clinical engagement were common. All these reinforce that the drivers of menopause inequity are systemic rather than purely individual, requiring a reconfiguration of how menopause is recognised, discussed, and supported across Malaysian society.

Clinical Implications

For Malaysian women, the findings highlight critical opportunities for enhancing clinical care through earlier identification, culturally sensitive communication, and proactive symptom management. The absence of routine enquiry about menopause in chronic disease reviews represents a missed window to address GSM, sexual function, and sleep disturbance conditions that significantly affect quality of life and can be managed with accessible interventions such as vaginal moisturisers, pelvic floor therapy, and cognitive-behavioural strategies for insomnia. Clinicians must also recognise the cultural and religious dimensions of symptom experience, including the impact of menstrual irregularities on religious observance, and integrate this into counselling. The fear of HRT, often based on anecdote evidence rather than scientific, underscores the need for balanced risk-benefit discussions and shared decision-making that respect individual beliefs. Training programmes for primary care providers should incorporate menopause-specific modules, with practical guidance on discussing intimate symptoms in culturally sensitive ways. This would help bridge the knowledge gap, build trust, and ensure that treatment plans are acceptable, feasible, and aligned with women’s values and lived realities.

Sociological Implications

Malaysia’s plural society, Malay, Chinese, Indian and numerous other indigenous communities, sits within a strongly multilingual and religious landscape (Malay, Mandarin, Tamil, English; Islam 63.5%, Buddhism 18.7%, Christianity 9.1%, Hinduism 6.1%)20. Urbanisation is high (about 78–-79%), yet a sizeable minority remain in rural settings where service reach differs21. These macro-features shape how women interpret symptoms, disclose intimate concerns, and navigate care. Qualitative work with East Coast Malaysian women shows limited pre-emptive knowledge, reliance on peers, and an explicitly religious framing of the midlife phase, treating menopause as a time to deepen faith.

Chinese-heritage narratives from regional syntheses emphasise normalisation, use of traditional remedies and reticence to discuss sexual function patterns echoed locally. Together, these dynamics make information pathways, cultural modesty around genitourinary symptoms, and faith-practicalities such as ritual purity during prolonged bleeding, central to care acceptability. Traditional and complementary medicine is widely accessed, especially evening primrose oil, black cohosh, vitamins/minerals and Chinese herbal preparations, often preferred over “chemical” medicines and sometimes chosen on cost grounds22. Such choices can delay assessment of red-flag bleeding or under-treat distressing GSM unless clinicians explicitly explore beliefs and affordability.

Practice and Policy Implications

The integration of patient experiences into practice and policy design is essential to broaden the applicability and equity of menopause care in Malaysia. Workplace policies should explicitly address menopause, offering flexible scheduling, rest spaces, and temperature control, while embedding menopause awareness into leadership training to dismantle stigma and normalise discussion. At the health system level, national guidelines should mandate the inclusion of routine menopause screening questions within midlife and chronic disease consultations, supported by culturally adapted public health campaigns in multiple languages. Geographic inequities could be mitigated by expanding specialist telehealth services and training regional providers in menopause management, ensuring equitable access for rural populations. Patient narratives from this study provide a blueprint for such reforms, emphasising the need for accessible information, emotional support, and service models that account for both biological symptoms and their sociocultural framing. Embedding these voices in guideline development, CME curricula, and public education will not only improve the relevance of interventions but also affirm menopause as a legitimate and visible component of women’s health policy.

The 2022 Malaysian Clinical Practice Guideline (CPG) is methodologically strong (AGREE II-appraised as high quality overall) and provides clear, evidence-based recommendations on definitions, investigation of abnormal bleeding, indications / contraindications for menopausal hormone therapy (MHT), and GSM / long-term risk management23,24. It recognises Malaysia’s multilingual reality and explicitly calls for public awareness in three main languages. It also acknowledges scarce MHT options in peripheral facilities and proposes a Menopause Care Programme and CME.

Gaps Against Lived Realities

Applicability and reach. The primary-care appraisal notes the applicability domain scored lowest, signalling implementation weaknesses. The CPG limits initiation of MHT to specialists or trained practitioners, which, in practice, can bottleneck access outside major centres. While it observes the scarcity of MHT in peripheral clinics, it stops short of specifying procurement / financing mechanisms, after-hours models or telehealth to mitigate urban–rural gradients.

Culture, religion and modesty. Beyond multilingual awareness, the CPG offers little practical guidance on faith-sensitive counselling, such as managing prolonged bleeding that interrupts prayer, sexual-health modesty, or how to discuss dyspareunia and low libido in ways that address marital expectations and consent issues that qualitative Malaysian evidence shows are pivotal.

Work and Psychosocial Context

There is no specific section on workplace policy or occupational adjustments, such as heat control, flexible rostering, private rest spaces, signposting, despite emerging local employer initiatives and consistent reporting that informal support currently does the heavy lifting.

The MARIE WP2a findings highlight that any guideline’s real-world impact will depend on embedding explicit attention to Malaysia’s cultural-religious norms, such as faith-practice disruptions during irregular bleeding, modesty in discussing sexual health, information ecosystems, and economic realities, such as cost-related discontinuation of supplements or private consultations. In addition, the workplace context where an absence of formal menopause policies, reliance on informal support can cause staff retention at a time Malaysia’s population continues to grow at a rapid rate, alongside of a significant ageing population. Strengthening the guideline’s applicability through primary-care empowerment to initiate and manage low-risk MHT, culturally tailored counselling that addresses religious sensitivities and modesty norms, and equity monitoring to ensure measurable uptake in rural, multilingual, and lower-literacy populations would directly close the gap between the guideline’s evidence-based intent and the lived experiences of Malaysian women documented in this study. As such, we propose culturally responsive recommendations for any future guidelines in

Table 4.

Table 4.

Proposed culturally responsive and equity-oriented add-ons to strengthen future clinical practice guideline on menopause.

Table 4.

Proposed culturally responsive and equity-oriented add-ons to strengthen future clinical practice guideline on menopause.

| No. |

Recommendation |

Key Actions |

Primary Stakeholders / Sources |

| 1 |

Embed cultural & religious pragmatics into clinical pathways |

• Incorporate brief, scripted prompts and leaflets on: discussing intimacy with modesty; first-line GSM options compatible with faith practices; advice for prolonged/irregular bleeding disrupting prayer.

• Integrate clear red-flag messages and investigation triggers.

• Use the existing guideline’s abnormal uterine bleeding algorithm, but enhance it with faith-sensitive communication guidance. |

Health authorities |

| 2 |

Shift from specialist-centric to primary-care-enabled access |

• Authorise primary-care initiation of low-risk MHT under protocol, with remote specialist backup.

• Specify procurement lists for district clinics.

• Support teleconsultation for rural areas.

• Introduce clinic-level audit indicators (e.g., proportion of women 45–60 screened for vasomotor symptoms / GSM; time-to-treatment for severe vasomotor symptoms). |

PubMed; health authorities |

| 3 |

Normalise conversations where women seek information |

• Provide clinician scripts to ask explicitly about uses of supplements / TCM.

• Deliver balanced, evidence-based counselling on benefits / limits.

• Develop multilingual micro-modules and WhatsApp-sized patient explainers co-designed with major ethnic communities.

• Extend guidelines’ language recommendations to everyday communication channels. |

Helath authorities; PMC |

| 4 |

Bring the workplace into scope |

• Add occupational health annexe: symptom-aware rostering, uniform / fabric guidance, hydration and temperature access, confidential referral routes, and manager training.

• Encourage ministries and major employers to adapt annexe content. |

Ova |

| 5 |

Track equity, not just efficacy |

• Require routine reporting by ethnicity, language, and urban / rural location.

• Ensure equity metrics accompany clinical indicators for national audit.

• Use guideline’s clinical algorithms as baseline framework. |

Health authorities |

Conclusions

Menopause in Malaysia appears to be universal, but socially mediated factors, shaped by cultural, religious, and systemic contexts. Women’s accounts highlight gaps in awareness, service provision, and workplace recognition that perpetuate inequities in symptom management and support. Strengthening culturally competent clinical care, empowering primary care to deliver menopause services, and embedding workplace and public health policies are urgently required. Addressing these gaps will ensure that the national guideline translates into meaningful improvements in quality of life and equity for Malaysian women across the menopausal transition.

Author Contributions

GD developed the ELEMI program and the MARIE project. This was furthered by GD and PP. THT submitted and secured the ethics approval for the study in Malaysia. KYL, LHN, JJ, NFMN, AHA, VR, NAJ and SNA collected data. GD and JQS conducted the data analysis. GD wrote the first draft and was furthered by THT and all other authors. All authors critically appraised, reviewed and commented on all versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Medical Research & Ethics Committee, Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR ID 23-03581-PO8 (IIR)).

Informed Consent Statement

Obtained.

Data Availability Statement

The Principal Investigator and the study sponsor may consider sharing anonymous data upon reasonable a request.

Acknowledgments

MARIE Consortium: Choon-Moy Ho, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Jinn-Yinn Phang, Puong-Rui Lau, Paula Briggs, Donatella Fontana, Victoria Corkhill, Kingshuk Majumde,Heitor Cavalini, Emmanuel Chukwubuikem Egwuatu, Isaiah Chukwuebuka Umeoranefo, Chukwuemeka Chidindu Njoku, Ayyuba RABIU, Chijioke Chimbo, Eziamaka Pauline Ezenkwele, Divinefavour Echezona Malachy, Lydia Ijeoma Eleje, Chinedu Onwuka Ndukwe, Sunday Onyemaechi Oriji, Raphael Ugochukwu Chikezie, Ifeoma Bessie Enweani-Nwokelo, Nnanyelugo Chima Ezeora, Odigonma Zinobia Ikpeze, Sylvester Onuegbunam Nweze, Assumpta Chiemeka Osunkwo, Gabriel Chidera Edeh, Esther Ogechi John, Kenechukwu Ezekwesili Obi, Kingsley Emeka Ekwuaz, Ugoy Sonia Ogbonna, Halima Bashir Muhammad, Kingsley Chukwuebuka Agu, Chiamaka Perpetua Chidozie, Odili Aloysius Okoye, Chukwuemeka Chukwubuikem Okoro, Arinze Anthony Onwuegbuna, Ikechukwu Innocent Mbachu, Joseph Ifeanyichukwu Ikechebelu, Chinyere Ukamaka Onubogu, Kingsley Chidiebere Nwaogu, Nnaedozie Paul Obiegbu, Obinna Kenneth Nnabuchi, Susan Nweje, Chigozie Geoffrey Okafor, Oludolamu Oluyemesi Adedayo, Chinelo Onuegbuna Okoye, Babatunde Rufus Kumuyi, Oluwasegun Ajala Akanni, Perpetua Kelechi Enyinna, Yusuf Alfa, Theresa Nneoma Otis, Michael Nnaa Otis, Chidiebere Agbo, Francis Chibuike Anigwe, Chidimma Judith Anyaeche, Olisaemeka Nnaedozie Okonkwo, Bethel Chinonso Okemeziem, Bethel Nnaemeka Uwakwe, Goodnews Ozioma Igboabuchi, Ifeoma Francisca Ndubuisi, Amarachi Pearl Nkemdirim, Kim-Yen Lee, Siti Nurul Aiman Ali Madinah, Nurul Amalina Jaafar, Xiu-Sing Wong, John Yen-Sing Lee, Yee-Theng Lau, Alyani Mohamad Mohsin, Nor Fareshah Mohd Nasir, Diana Suk-Chin Lau, Farhawa Zamri, Artini Abidin, Aini Hanan Azmi, Rosdina Abd Kahar, Fatin Imtithal Adnan, Puong Rui-Lau, Xin-Sheng Wong, Geok-Seim Lim, Eunice Yien-Mei Sim, Karen Kristelle, Asma’ Mohd Haslan, Noorhazliza Abdul Patah, Vaitheswariy Rao Nalathambi, Juhaida Jaafar, Jinn-Yinn Phang, Lee Leong Wong, Nurfauzani Ibrahim, Siew-Yew Ting, Susan Chen-Ling Lo, Norhazura Hamdan, Min-Huang Ngu, Choon-Moy Ho, Safilah Dahian, Daniel Leong-Hoe Ngu, Sing-Yee Khoo, Kamilah Dahian, Jeffrey Soon-Yit Lee, Shubashini Kanagaratnam, Amirah Fazira Zulkifli, Manisha Mathur, Rukshini Puvanendran, Farah Safdar, Rajeswari Kathirvel, Raksha Aiyappan, Ganesh Dangal, Puja Lam, Thamudi Sundarapperuma, Prasanna Herath, Damayanthi Dassnayake, Chandrani Herath, Nimesha Wijayamuni, Cristina Laguna Benetti-Pinto, Renan Massao Nakamura, Daniela Angerame Yela, Gabriela Pravatta Rezende, Renan Massao Nakamura, Isaac Lartey Narh, Kwasi Eba-Polley, Catherine Narh Menka, Prince Osei, Nana Osei, Lemuel Lartey, Bernard Bortieh, Cletus Kumi, Elijah Boafo, Janet Ayorkor Anyetei, Edel Issabella Arthur, Horatio King Glover, Fredrick Amoah, Ethel Larteley Boye, Zerish Lamptey, Laurinda Gyan, Bharat Prasad, Shaziya Noor, Kumari Shilpa, Poonam Singh, Usha Jha, Manu Chatterjee, Oscar Mahinyila, Alosisia Shemdoe, Kornelio Mpangala, Filbert Ilaza , Zepherine Pembe, Mpoki Kaminyoge, Thomas Alon.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors report no conflict of interest. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the National Institute for Health Research, the Department of Health and Social Care or the Academic institutions.

References

- Delanerolle G, Phiri P, Elneil S, et al. Menopause: a global health and wellbeing issue that needs urgent attention. The Lancet Global Health 2025, 13, e196–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra GD, Chung H-F. Menopause, A stage in the Life of Women. Menopause: a comprehensive approach: Springer, 2025: 3-10.

- McCarthy M, Raval AP. The peri-menopause in a woman’s life: a systemic inflammatory phase that enables later neurodegenerative disease. Journal of neuroinflammation 2020, 17, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis SR, Pinkerton J, Santoro N, Simoncini T. Menopause—Biology, consequences, supportive care, and therapeutic options. Cell 2023, 186, 4038–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appiah D, Nwabuo CC, Ebong IA, Wellons MF, Winters SJ. Trends in age at natural menopause and reproductive life span among US women, 1959-2018. Jama 2021, 325, 1328–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu D, Chung H-F, Dobson AJ, et al. Type of menopause, age of menopause and variations in the risk of incident cardiovascular disease: pooled analysis of individual data from 10 international studies. Human Reproduction 2020, 35, 1933–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nalliah, S. The Menopause and Beyond: Xlibris Corporation; 2013.

- Panay N, Anderson R, Nappi R, et al. Premature ovarian insufficiency: an international menopause society white paper. Climacteric 2020, 23, 426–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nappi RE, Siddiqui E, Todorova L, Rea C, Gemmen E, Schultz NM. Prevalence and quality-of-life burden of vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: A European cross-sectional survey. Maturitas.

- Nappi RE, Kroll R, Siddiqui E, et al. Global cross-sectional survey of women with vasomotor symptoms associated with menopause: prevalence and quality of life burden. Menopause 2021, 28, 875–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M. The urogenital system. The Biology of Ageing: CRC Press; 2022: 147-56.

- Samsioe, B. Urogenital aging—a hidden problem. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1998, 178, S245–S9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackey S, Teo SSH, Dramusic V, Lee HK, Boughton M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices associated with menopause: a multi-ethnic, qualitative study in Singapore. Health care for women international 2014, 35, 512–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabir MR, Chan K. Menopausal experiences of women of Chinese ethnicity: A meta-ethnography. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0289322. [Google Scholar]

- Damodaran P, Ng BK, Azmi AH. Menopausal symptoms among multi-ethnic working women in Malaysia. Climacteric.

- Barber K, Charles A. Barriers to accessing effective treatment and support for menopausal symptoms: a qualitative study capturing the behaviours, beliefs and experiences of key stakeholders. Patient preference and adherence.

- Rodrigues MAH, Reis ZSN, Verona APdA, et al. Climacteric women’s perspectives on menopause and hormone therapy: Knowledge gaps, fears, and the role of healthcare advice. PLoS One 2025, 20, e0316873. [Google Scholar]

- Nappi RE, Cucinella L, Martini E, Cassani C. The role of hormone therapy in urogenital health after menopause. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism 2021, 35, 101595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delanerolle, G. The Delanerolle and Phiri Theory: The Basis to the Novel Culturally Informed ELEMI Qualitative Framework for Women’s Health Research. 2025.

- Mohiuddin, A. Malaysia’s Minority Mosaic: Struggles and Triumphs in a Diverse Nation. Human Rights Law in Egypt and Malaysia: Minorities and Gender Equality, Volume 2: Springer, 2024: 113-72.

- Ibrahim R, Tan J-P, Hamid TA, Ashari A. Cultural, demographic, socio-economic background and care relations in Malaysia. Care Relations in Southeast Asia: Brill; 2018: 41-98.

- Kass-Annese, B. Alternative therapies for menopause. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology 2000, 43, 162–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee WK, Ooi NZM, Goh SL. Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Menopause in Malaysia 2022: A review from a primary care perspective. Malaysian Family Physician: the Official Journal of the Academy of Family Physicians of Malaysia.

- Ong TIW, Lim LL, Chan SP, et al. A summary of the Malaysian Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis, 2022. Osteoporosis and Sarcopenia 2023, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).