1. Introduction

The The historical evolution of steganography traces back to ancient Greece, where Herodotus first alluded to the practice in 440 BC. The term itself, derived from the Greek words "Steganós" (covered) and "graphia" (writing), was formally introduced by Johannes Trithemius in 1499 in his cryptographic treatise. Over centuries, steganography played a pivotal role in covert communications, particularly during wartime, where techniques such as invisible ink and microdots facilitated clandestine information exchange [

1]. The digital age ushered in a new era of steganography with its integration into multimedia files, including images, documents, and software programs. Modern steganographic techniques enable secure information embedding while remaining invisible to adversaries by subtly altering pixel color values or modifying imperceptible data structures [

2].

With the exponential growth of digital data, security concerns have become paramount, particularly regarding user privacy and data integrity in transmission and storage. Against this backdrop, Steganography—an ancient practice of covert communication—has resurfaced as a crucial safeguard. By embedding messages in seemingly innocuous carriers, Steganography offers a sophisticated layer of security that transcends conventional encryption, rendering sensitive information imperceptible to unauthorized observers [

3].

In the modern digital era, the significance of Steganography has intensified, providing a discreet yet robust mechanism for secure communication. Its seamless integration into digital media ensures the confidentiality of embedded information while evading detection, reinforcing its relevance in an era characterized by pervasive connectivity and escalating cyber threats [

4]. As the pursuit of secrecy and security remains perpetual, Steganography continues to evolve, bridging ancient cryptographic wisdom with contemporary digital protection strategies [

5]. The methodology employed in this study aims to minimize perceptual distortions in cover images, preserving their visual fidelity while ensuring the undetectability of pixels carrying the hidden message. By leveraging innovative techniques and rigorous analytical frameworks, this work seeks to contribute meaningfully to cybersecurity, fostering collaboration within the research community to propel advancements in secure digital communication.

Our work redefines reversible steganography by solving three fundamental limitations of spatial-domain techniques. First, we introduce cryptographic entropy modulation to achieve true reversibility in LSB embedding—a capability previously deemed impossible without auxiliary data. Second, our dual-channel architecture with adaptive pixel manipulation eliminates the statistical artifacts that plague conventional methods, making the embedded data indistinguishable from natural noise. Third, the framework dynamically optimizes payload distribution through deterministic yet unpredictable transformations, bypassing the traditional trade-offs between capacity and detectability. Unlike prior approaches that rely on post-embedding encryption or fragile interpolation, our method embeds security at the algorithmic level through mathematically provable operations. The result is the first steganographic system that simultaneously guarantees lossless recovery, undetectability against machine learning analysis, and maximal payload capacity—establishing a new theoretical foundation for secure data hiding.

This research unfolds systematically to provide a profound understanding of reversible image steganography.

Section 2 critically reviews the literature, exposing research gaps and defining key objectives.

Section 3 rigorously establishes the mathematical foundations, detailing the algorithms and security mechanisms that support the proposed techniques.

Section 4 presents empirical results alongside a comprehensive analysis of their effectiveness and resilience. Finally,

Section 5 synthesizes the findings, offering conclusive insights and strategic directions for future advancements in this evolving field.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Reversible and Non-Reversible Image Steganographic Techniques

In digital security, steganography is crucial for enabling covert communication through image data. Researchers classify steganographic techniques into two main categories: reversible (lossless) and non-reversible (lossy) methods, each presenting distinct benefits and challenges [

6].

2.2. Foundations of Reversible Data Hiding (RDH): Bit-Plane Slicing and Least Significant Bit Techniques

Before exploring reversible data hiding (RDH) in digital images, it is essential first to comprehend the foundational principle of bit-plane slicing (BPS), which underpins the least significant bit (LSB) embedding technique—an integral method prevalent in RDH schemes. BPS operates by isolating each bit position within a pixel’s value in 8-bit grayscale or 24-bit color images [

7]. This technique divides pixels into binary layers, ranging from the Most Significant Bit (MSB) to the Least Significant Bit (LSB). At the same time, the MSB profoundly affects the image’s appearance, and the LSB exhibits minimal visual impact. In practice, pixel values are converted to a binary format and standardized to a uniform bit-width, allowing for the generation of individual bit planes that signify the presence of original bits as 1s or 0s.

In steganography, binary message bits seamlessly replace the LSBs, embedding hidden information within these least impactful components of the image. The LSB steganography technique thus facilitates clandestine communication by subtly inserting confidential data into digital images, leveraging the human visual system’s limitations, which often overlook minor variations in image fidelity; this allows covert messages to remain undetected. However, it is crucial to acknowledge the technical challenge associated with concealing message carrier pixels.

This study builds upon previous spatial domain digital imagery analyses by exploring foundational strategies, evaluating their effectiveness, and identifying emerging research opportunities in LSB-based data-hiding methods.

2.2.1. Types of Least Significant Bit (LSB) Steganography

[

8] first proposed using the least significant bit to hide data within images. Kurak et al. [

9] further explored this technique, outlining key considerations for its effective use. In image steganography, two primary methodologies exist for covertly embedding confidential data, namely: LSB Matching and LSB Replacement [

10]. Both techniques manipulate the least significant bit of pixel values to conceal information, yet they differ significantly in their strategies, advantages, and limitations. This analysis explores these approaches, highlighting their strengths and weaknesses within the broader digital security framework.

- a.

-

The LSB Replacement Technique

This technique directly replaces the least significant bit of each pixel with a corresponding bit from the secret message. With a computational complexity of , it efficiently supports real-time applications due to its rapid embedding and extraction processes. However, its simplicity makes it highly susceptible to statistical attacks, which can reveal hidden data through pixel value distribution analysis. Additionally, its straightforward implementation exposes it to visual attacks, where concealed information may become detectable, ultimately compromising the security of the steganographic system.

Example

LSB replacement embeds secret data by modifying the least significant bit of pixel values. Consider three grayscale pixels with values 202, 183, and 225, represented in binary as 11001010, 10110111, and 11100001, respectively. To embed the secret message "101", the least significant bits (LSBs) are replaced, resulting in modified pixels: (203), (181), and (227). This substitution keeps visual distortions minimal while embedding data efficiently.

To extract the hidden message, the receiver reads the LSBs of the modified pixels, retrieving the bit sequence , which reconstructs the original secret data. Although LSB replacement offers computational efficiency, its susceptibility to statistical and visual attacks remains a significant drawback, as predictable pixel modifications can reveal hidden information through histogram analysis or anomalies in pixel distributions.

- b.

-

LSB Matching Steganography

LSB Replacement technique directly modifies LSBs, making them more susceptible to detection, whereas LSB Matching offers improved security, particularly in grayscale images. The revisited LSB Matching approach encodes secret data as a bit stream and processes each pixel based on a predefined key. The method only alters a cover pixel when its LSB differs from the corresponding secret bit, adjusting it randomly by to maintain statistical uniformity. This ensures a balanced distribution of changes when the secret message is smaller than the cover image. The receiver extracts the hidden message by reading the LSBs in the sequence dictated by the key, eliminating the need for the original cover image, which the sender discards.

Example

To embed a secret message within an image, consider an RGB pixel with binary values: (175), (212), and (122). Given the secret message , we modify the least significant bit (LSB) of the blue channel. The original LSB is 0, which we replace with the first bit of M, altering the blue value from 01111010 to 01111011 (123). The updated RGB triplet becomes , ensuring minimal visual distortion while embedding information.

For extraction, the receiver retrieves LSBs from the modified blue channel across selected pixels. The new blue value 01111011 has an LSB of 1, reconstructing the first bit of M. Repeating this for subsequent pixels yields the full message . This method ensures efficient and accurate message retrieval, making LSB-based steganography a widely used approach for covert communication.

Since 2006, Mielikainen’s scheme has been a cornerstone in steganographic research, inspiring novel and hybrid embedding strategies. Its effectiveness stems from its ability to introduce minimal distortions in stego images while offering strong resistance against various LSB detection algorithms. This robustness has cemented its status as a preferred approach for enhancing security in covert communication.

2.2.2. The Superiority of LSB Algorithms in Steganography

The efficacy of Least Significant Bit (LSB) replacement and matching algorithms remains unmatched in steganography, primarily due to their inherent ability to embed data with minimal perceptual distortion. Consider a pixel value represented as

P, which is expressed in binary form as

. When a bit

m from a secret message is embedded, the transformation is defined by the function:

This demonstrates that the replacement of the least significant bit permits seamless embedding without perceptual artifacts—as the substantial pixel alteration is constrained by the condition . In contrast, alternative techniques, including complex hybrid methods, often require extensive computational overhead or lead to increased distortion or vulnerability to detection through statistical analysis. Thus, LSB methods yield a unique combination of simplicity, efficiency, and robustness, as they enable data concealment while adhering to the crucial constraint , where represents the modified pixel. This illustrates that, despite the advancements in hybrid steganography, the elegant nature of LSB approaches offers an unparalleled solution, establishing them as essential whenever minimal distortion and maximal efficiency are paramount.

2.3. A Chronological Perspective on Reversible Data Hiding (RDH) in Image Steganography

The evolution of RDH techniques underscores the ongoing efforts to balance security, imperceptibility, and robustness. Integrating spatial and transform domain approaches, hybrid methods continue to refine trade-offs, ensuring adaptive embedding strategies resilient to advanced steganalysis. Future advancements will focus on deep-learning-driven RDH models, enhancing efficiency while safeguarding against adversarial detection [

11].

Table 1 tabulates the pioneering image-based reversible data hiding (RDH) techniques. These techniques leverage various methods to embed secret data into images while maintaining the original image quality. Each technique is described by highlighting the advantages and the mathematical equations representing how data is embedded or extracted. This overview not only refers to the fundamental approaches in the domain but also serves as a guide for researchers and practitioners interested in the advancements of steganography techniques.

- a)

Conventional Steganography/Pioneering Techniques: Researchers introduced Difference Expansion (DE) in [

12], a method to embed 0.5 bits per pixel (bpp) payloads across two pixels. Still, it demands extra data for retrieval and degrades image quality with repeated usage. In contrast, [

13] pioneered Histogram Shifting (HS) to analyze pixel frequency distributions for secure data hiding. Still, this method encountered setbacks when peak points shifted, limiting its payload capacity. [

14] further refined this concept by categorizing images into ascending pixel value sets to identify optimal hiding spots called Pixel Value Ordering (PVO), yet payloads remained constrained due to the need for intricate location maps. Meanwhile, [

15] and [

16] leveraged modification directionality and quinary symbols to develop dual-image (DI) hiding strategies [

17] that necessitated two stego images and supplementary ordering data. Lastly, [

18] introduced a pixel interpolation technique to create synthetic virtual pixels for data concealment, but this came at the cost of significantly reducing the original image size, thus limiting its application potential in critical fields like medical imaging.

Recent scholarly endeavors such as DE ([

19,

20,

21]), HS ([

22,

23,

24,

25]), PVO ([

26,

27,

28]), DI ([

29,

30,

31]), and IP ([

32,

33,

34]) have sought to advance the paradigm in steganography, concentrating on bolstering the capacity and perceptual subtlety of concealed data while concurrently neglecting to incorporate comprehensive countermeasures against formidable attacking scenarios, such as adversarial knowledge of the employed embedding algorithm and the cover image, thereby creating a pronounced vulnerability that compromises the efficacy of the entire security framework.

2.4. Challenges in Contemporary Spatial-Domain Image Steganography

Contemporary spatial-domain image steganography, which heralds the promise of discreet data transmission, faces significant deficiencies that fundamentally compromise its foundational tenets of confidentiality and integrity. The recurrent employment of carrier images renders embedded data perilously susceptible to detection through rigorous statistical and algorithmic scrutiny. Furthermore, deterministic extraction methodologies predicated on clandestine algorithms contravene Kerckhoff’s principle, facilitating the facile retrieval of concealed information. Excessive dependence on encryption mechanisms accentuates vulnerabilities in embedding protocols, thereby eroding systemic security. Inadequate key management and the oversight of potential attack vectors exacerbate the intricate balance of privacy and undetectability. Additionally, the conflation of imperceptibility and undetectability results in detectable artifacts, further undermining the dependability of the encoded information.

2.4.1. Vulnerability to Statistical Detection

The persistent utilization of a carrier image C, augmented with payloads P, subjects the steganographic framework to the perils of statistical assault. Define C as the cover image represented in a matrix form of pixel values , wherein , and let denote the resultant stego-image.

The embedding operation transforms

C into

via a function

, expressed as:

where

, with

, representing the payload.

Upon repeated utilization, inherent statistical attributes, such as the co-occurrence matrix

, defined as:

where

denotes the Kronecker delta function, unveils anomalies within pixel distributions, thus facilitating detection. The emergence of statistical deviations from

(the unaltered cover) infringes upon the principle of undetectability:

2.4.2. Failure of Adherence to Kerckhoff’s Principle

Let

symbolize the embedding function, frequently characterized by determinism and contingent upon a secret key

K. Kerckhoff’s principle stipulates that the security of a system must solely hinge on the confidentiality of the key, disallowing reliance on the obscurity of the encryption algorithm itself. The embedding operation can be articulated as:

where

epitomizes the embedding function parameterized by

K, and the extraction process is delineated by:

Should either

or

be deterministic and publicly accessible, an adversary could subsequently extract the payload

P devoid of the key

K, constituting a breach of Kerckhoff’s tenet:

where

signifies the entropy of the payload, and

A represents the adversarial algorithm.

2.4.3. Fragility of Embedding Strategies

The embedding function

serves to alter pixel values within

C to incorporate the payload

P. Designate

as the encrypted stego-image. An overreliance upon encryption presupposes that:

where

g signifies a cryptographic transformation. This inference anticipates that encryption adequately obfuscates

such that:

However,

g fails to ameliorate the detectable artifacts introduced by

f. Notably,

may exhibit clustering in modified least significant bits

:

yielding residual patterns that are discernible through first-order statistical analysis, thus contravening the premise of undetectability.

Figure 1 illustrates the artifacts resulting from bit-embedding. The difference between the original and stego image exposes the image’s role as a message carrier, highlighting the pixels holding the message. This also enables us to determine the length of the hidden content.

2.4.4. Suboptimal Key Management and Attack Vectors

Let

K denote the steganographic key disseminated between the sender and recipient. Complications in key management arise when:

where

is the keyspace, and

n embodies the key length. A constricted keyspace diminishes the entropy of

K, thereby rendering brute-force attacks a plausible threat:

where

t signifies the number of attempts.

Moreover, adversaries capitalize on overlooked attack vectors, such as payload clustering or the reuse of keys across multiple embeddings. The repetition of

K in:

facilitates differential analysis:

which may unveil the embedded payloads.

In short, the challenges in spatial domain steganography are multifaceted and require careful consideration of various factors, including statistical detection, adherence to Kerckhoff’s principle, fragility of embedding strategies, and suboptimal key management. Addressing these challenges is crucial for the development of secure and reliable steganographic systems.

2.4.5. Dual Image Steganography

Recently, dual image steganography has emerged as an innovative technique designed to overcome the limitations of traditional least significant bit (LSB) steganography by concealing data within two separate images, thereby enhancing payload concealment through increased complexity. However, a thorough examination uncovers considerable security vulnerabilities that jeopardize its effectiveness, as this method remains susceptible to various attack vectors due to its reliance on predictable algorithms and the inherent properties of the carrier images, which can provide adversaries with critical insights into the embedded data. Despite its potential for improved obfuscation, dual image steganography is vulnerable to statistical analysis and pattern recognition, compromising the confidentiality and integrity of the transmitted information. Moreover, the dual image approach is inherently fragile, necessitating the correct sequential transmission of both images; any alteration or misordering can irreparably damage the embedded data, creating a single point of failure. In contexts where images traverse unreliable channels or face stringent security scrutiny, the risk of interception, delay, or corruption significantly escalates, making this method particularly ill-suited for environments characterized by high packet loss or rigorous inspection protocols.

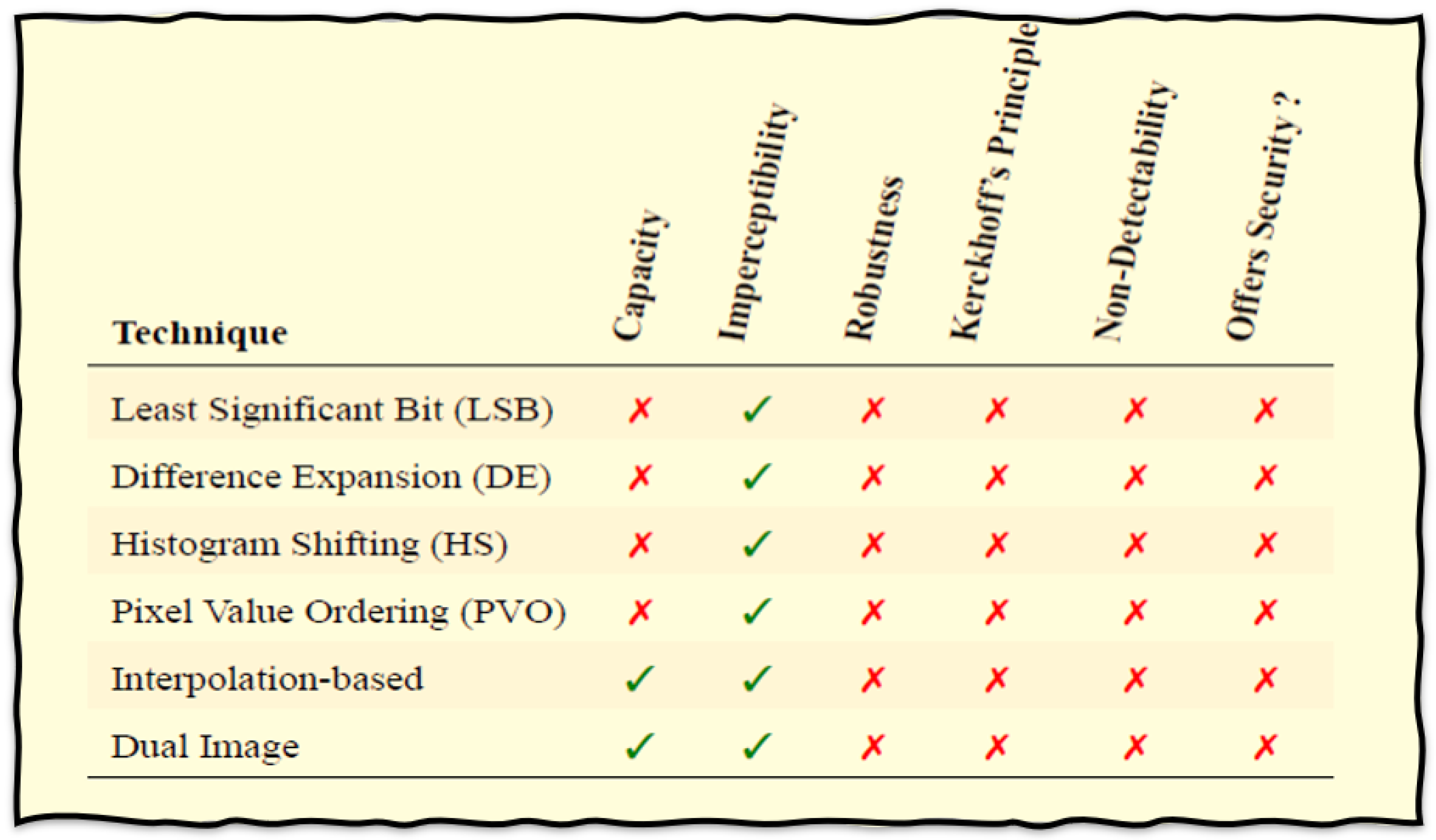

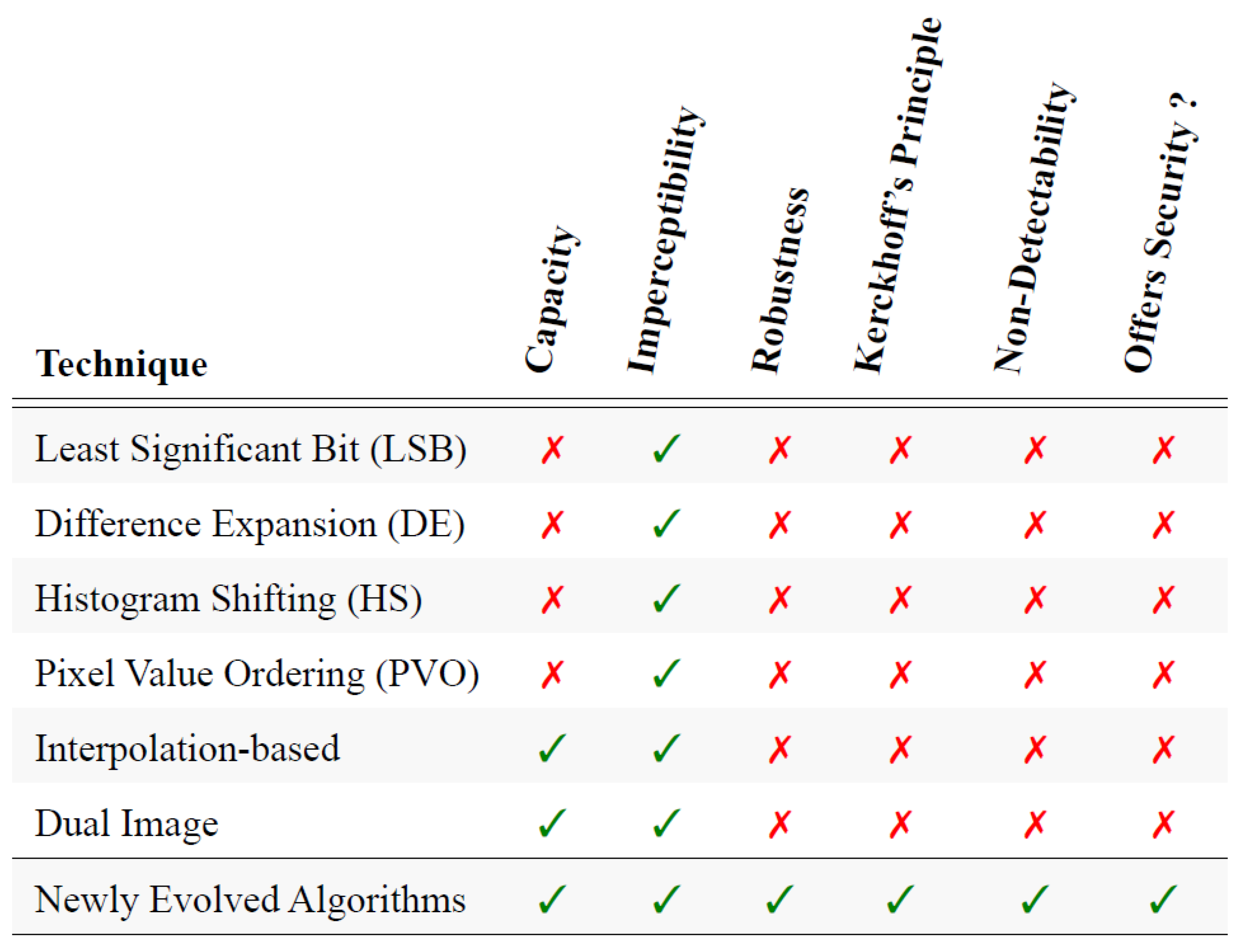

Table 2 concisely outlines the limitations intrinsic to current image-based Reversible Data Hiding (RDH) schemes while illuminating the underlying motivations that have prompted the initiation of this research endeavor.

Figure 2 gives a comparative assessment of the RDH image-based steganographic techniques.

3. Proposed Solution

3.1. Research Methodology

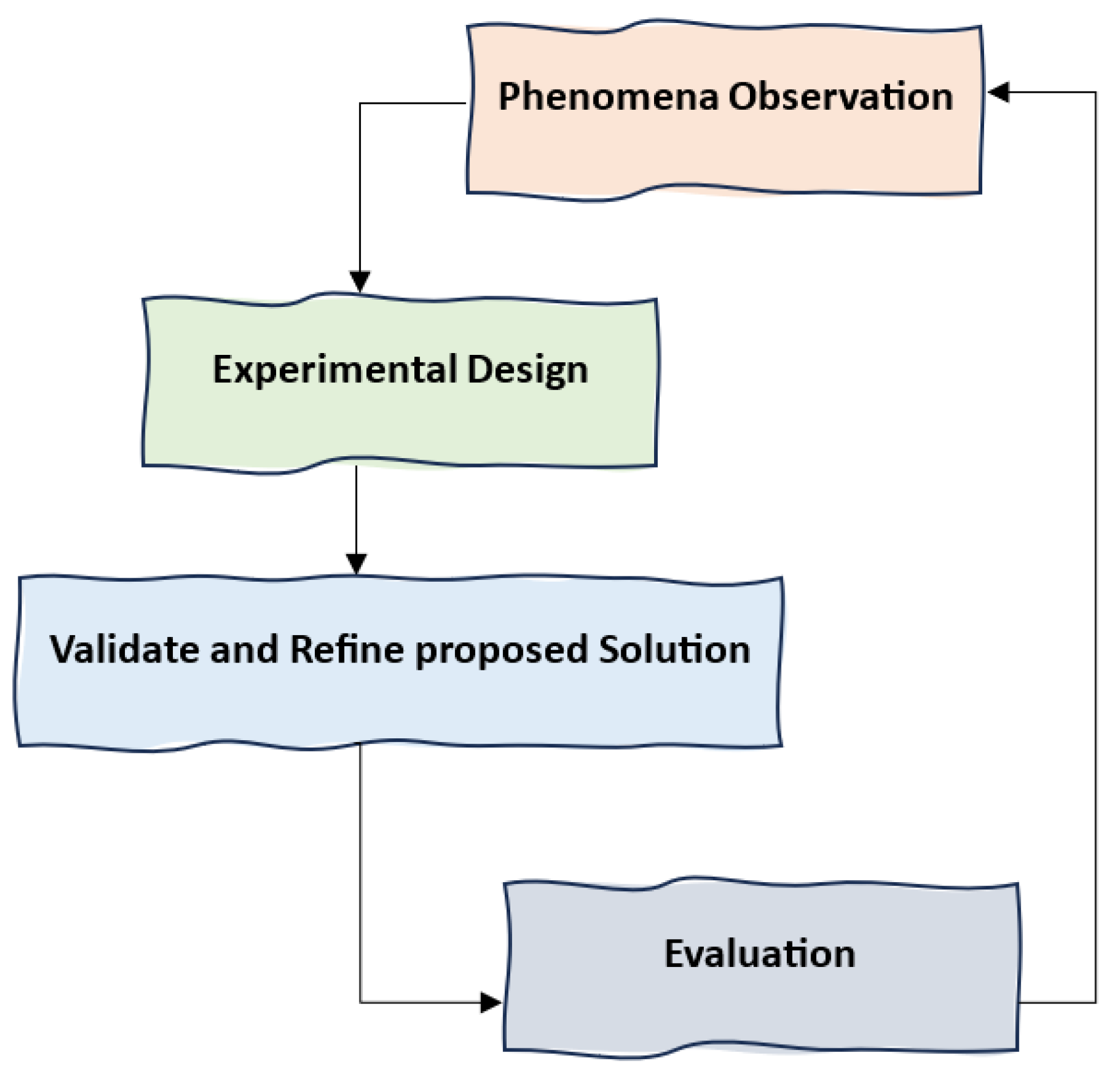

Our investigation into the security dimensions of reversible data hiding (RDH) adhered to a rigorously structured methodology, synthesizing observational, experimental, applied, and formal research paradigms within cybersecurity. The trajectory of our research, encapsulated in

Figure 3, illustrates a progressive evolution from empirical observation to systematic validation.

3.1.1. Phenomena Observation

The inception of our study involved a meticulous examination of latent vulnerabilities within legacy RDH frameworks, unveiling concealed security weaknesses embedded in the intricate interplay of dynamic systems. This foundational phase illuminated the inherent fragilities of existing methodologies and provided a pivotal reference point for our subsequent experimental inquiries, directing our analytical lens towards the most pressing security challenges in RDH, as delineated in [

35].

3.1.2. Experimental Design

Having identified these vulnerabilities, we transitioned into a rigorous experimental phase, leveraging MATLAB as a computational testbed to develop, simulate, and validate security-enhancing artifacts. This phase, rooted in experimental research traditions, allowed us to rigorously test our hypotheses under controlled conditions, sharpening our understanding of RDH system behaviors. Through an iterative process of real-world simulations, we reinforced the theoretical underpinnings of our security models with empirical evidence.

3.1.3. Validation and Refinement

Insights garnered from experimental trials catalyzed an iterative refinement cycle, wherein our RDH algorithms underwent progressive enhancement. We bridged the gap between theoretical constructs and practical applicability by systematically integrating lessons extracted from testing. This dynamic fusion of conceptual rigor and empirical validation defined the essence of applied research, driving the creation of a robust, security-optimized RDH framework with tangible real-world impact.

3.2. Design Considerations

A thorough review of existing literature highlights the urgent need to correct widespread security misconceptions often misrepresented as fundamental to steganography. Security hinges on protecting information through well-defined protocols, policies, and procedures, emphasizing confidentiality, integrity, and imperceptibility—seamless data concealment with minimal visual distortion. A significant misunderstanding stems from the interchangeable use of imperceptibility and undetectability. Imperceptibility ensures that embedded data blends aesthetically with the carrier medium, creating an illusion of invisibility, while undetectability involves structural differences that analytical methods can expose, potentially compromising covert information.

3.2.1. Kerckhoff’s Principle

Kerckhoff’s principle [

36] asserts that cryptographic system security relies on key secrecy, not algorithm transparency. This paradigm advocates open algorithm development and scrutiny, fostering trust and accountability. However, steganographic literature raises concerns regarding adherence to this principle, as many LSB substitution techniques exhibit vulnerability to attacks−challenges that the research arena must address while advancing steganographic schemes.

3.2.2. Attacks on Steganographic System

[

37] delineated six distinct attacking techniques in the context of cover and stego objects.

- i.

Stego-only attack: Analyzes the stego object without access to the cover or embedded message, detecting hidden data solely through its characteristics.

- ii.

Known cover attack: Compares the cover and stego object to identify anomalies or patterns indicative of embedded data.

- iii.

Known message attack: Matches a known message with the stego object to detect traces left by the embedding process.

- iv.

Chosen stego attack: Evaluates the stego object alongside the specific embedding tool to uncover vulnerabilities or signatures.

- v.

Chosen message attack: Generates a stego object from a predefined message to analyze patterns linked to steganographic methods.

- vi.

Known stego attack: Examines the cover and stego object using prior knowledge of the embedding tool to detect hidden data.

These six techniques form a robust steganalysis framework, strengthening digital communication security.

3.2.3. Steganalysis

As digital security threats evolve, steganography enables covert data transmission, while steganalysis detects hidden messages by analyzing statistical discrepancies between cover and stego files.

StegExpose, a cutting-edge steganalysis tool [

38], leverages statistical analysis and machine learning to identify concealed data in digital images with higher accuracy than traditional methods, by evaluating multiple steganographic algorithms, including

Sample Pairs,

RS Analysis,

Chi-Square Attack, and

Primary Sets, StegExpose empowers cybersecurity professionals and forensic experts to uncover hidden information efficiently. Its lightweight, open-source framework enhances digital communication security by exposing covert channels used for illicit data transfer.

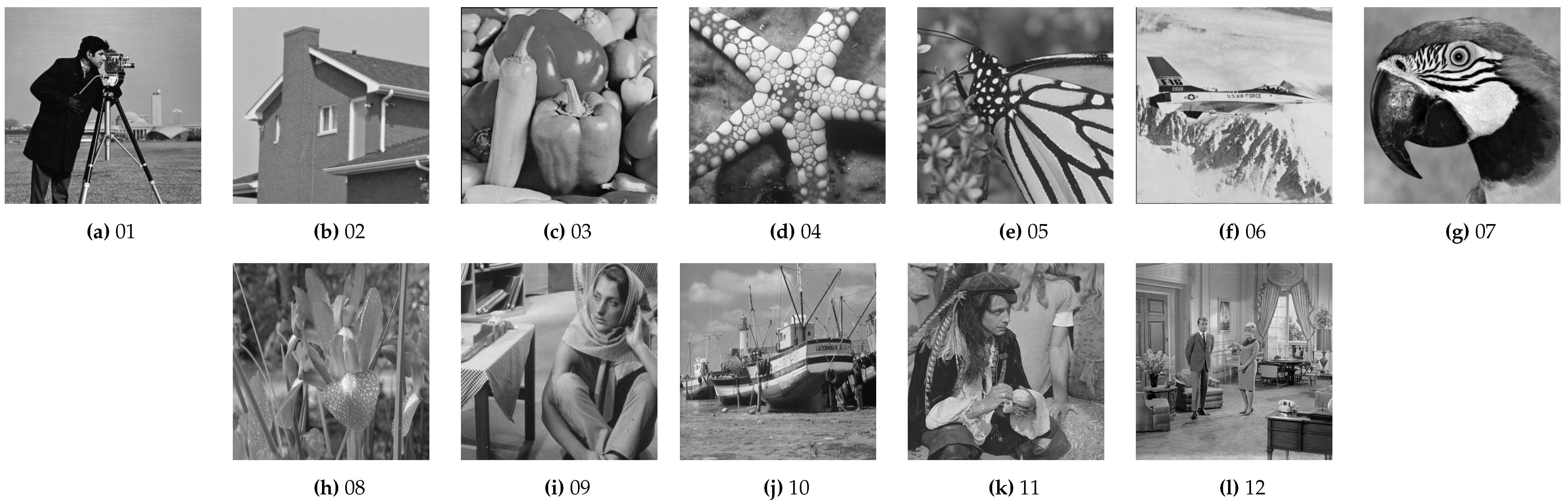

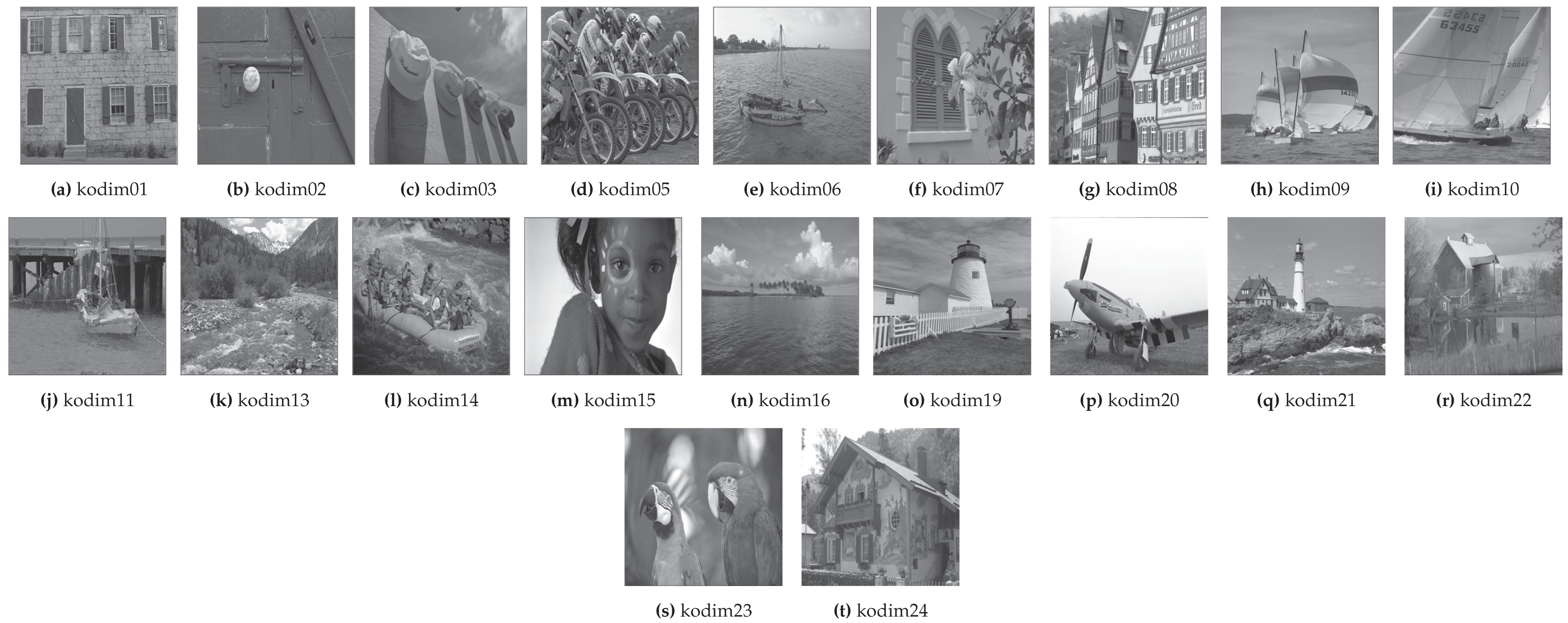

3.3. Dataset

A well-structured dataset benchmarks image-based steganography by assessing algorithm efficacy, robustness, and stealthiness. A diverse image collection supports realistic testing across key metrics like distortion, imperceptibility, and resilience to steganalysis. By revealing vulnerabilities and guiding adaptive strategies, an extensive dataset enhances data transmission security while fostering innovation in digital communication security.

A curated

dataset of 49 single channel grayscale images of size 512 × 512 from the public domain remained our preferred choice to test the efficacy of the newly evolved steganography algorithms. The diverse visual data facilitated a comprehensive analysis of algorithms’ capabilities in concealing information within digital imagery.

Figure 4 illustrates a selection of Images from this dataset.

3.4. Adaptive Embedding Model

The proposed framework formalizes embedding as a 5-tuple

where:

3.4.1. Precise Placement Algorithm

For each pixel :

1.

Position Selection:

where

is a SHA-256-derived PRNG and

t is the timestep.

2.

Capacity Allocation:

where

is the Laplacian operator,

is a texture threshold, and

is the sigmoid function.

embeds bits from message M

is a key-dependent predicate

is uniform noise

3.4.2. Security Properties

Theorem 1

(Undetectability)

. For all , there exists such that:

where runs in time.

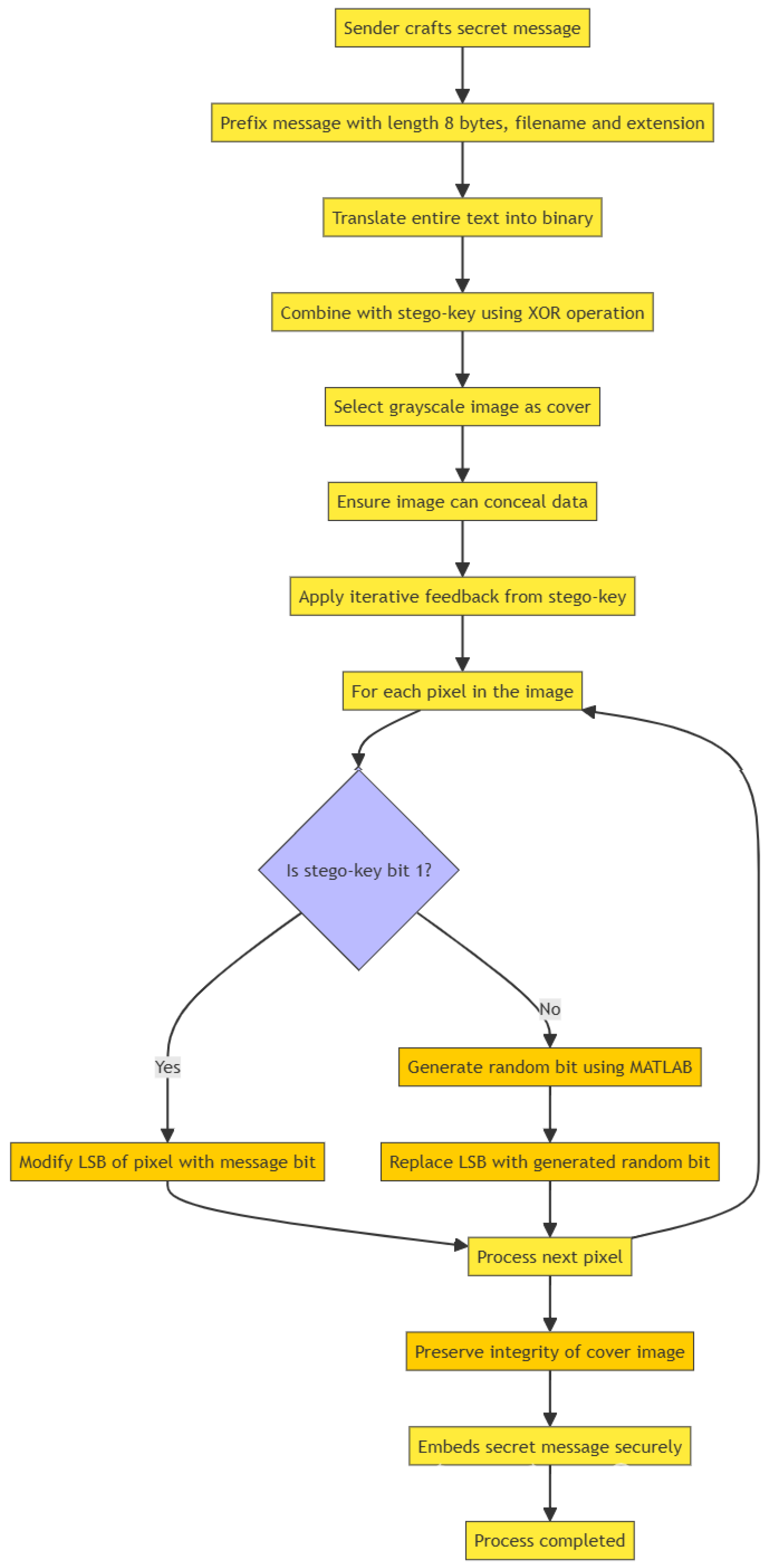

3.5. Secure RDH Image Steganography Schemes

- a)

Message Embedding Algorithm: The sender embeds a secret message by prefixing it with its length (8 bytes), filename, and extension (12 characters total), then converting it to binary. An Exclusive-Or operation with a stegokey enhances security. A suitable grayscale cover image ensures sufficient capacity for embedding. The stegokey undergoes iterative feedback, guiding modifications to the least significant bit (LSB) of image pixels. If the stegokey bit is 1, the system directly alters the LSB; if 0, it replaces the LSB with a MATLAB-generated random bit. This process preserves cover image integrity while securely embedding the message without detection.

|

Algorithm 1 Message Embedding

|

- 1:

Compose the message - 2:

Append message length (8 bytes), filename, and extension (12 characters) - 3:

Translate message to bits - 4:

Exclusive-Or (⊕) with stego key - 5:

Select grayscale image as cover - 6:

Choose iterative feedback stego key - 7:

for each pixel in the image do

- 8:

if stego key bit is 1 then

- 9:

Modify LSB of pixel with message bit - 10:

else

- 11:

Generate random bit using MATLAB’s function - 12:

Replace LSB with random bit - 13:

end if

- 14:

end for - 15:

Exit embedding process |

The flow diagram for message embedding is shown in

Figure 5.

- b)

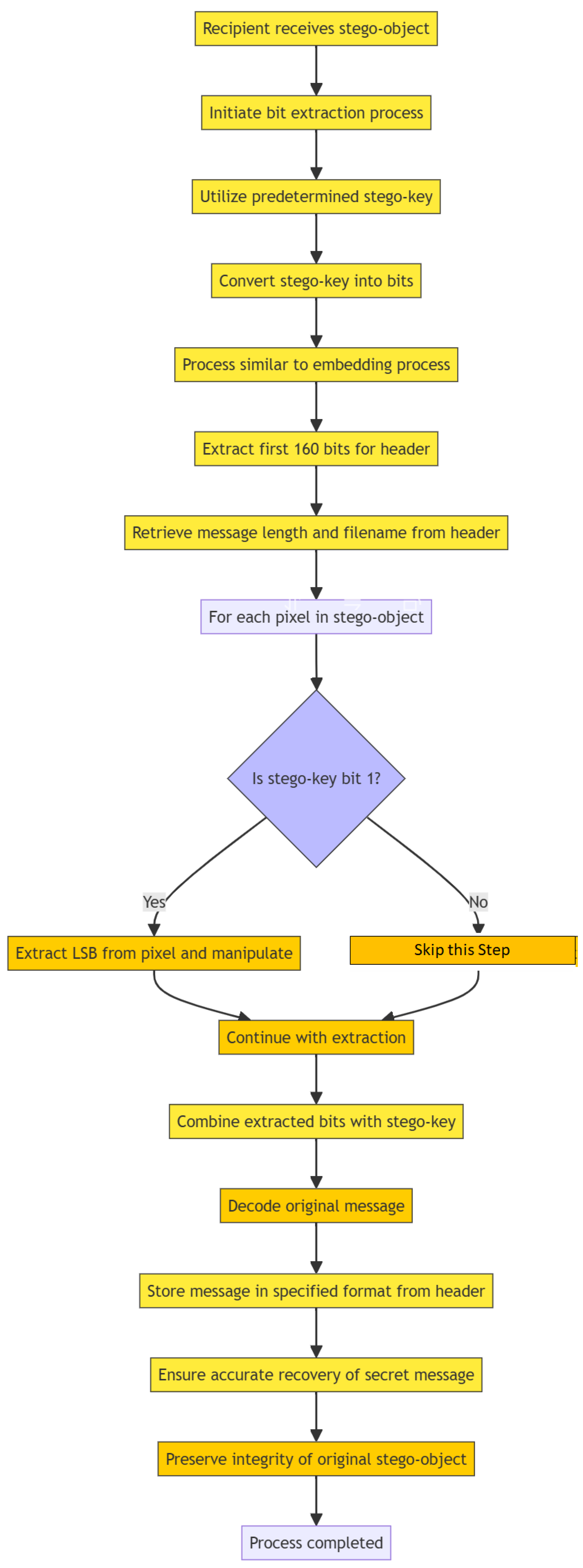

Message Extraction Algorithm: Upon receiving the stego object, the recipient uses the stego key to extract the hidden message. The process mirrors embedding, with the first 160 bits reserved for the header, containing the message length and filename. Depending on the stego key bit, the recipient extracts and manipulates the least significant bits of image pixels to reconstruct the message. Combining these bits with the stego key ensures accurate decoding while preserving the stego object’s integrity, enabling seamless message recovery.

|

Algorithm 2 Message Extraction

|

- 1:

Duplicate a PNG cover image and store as and

- 2:

Append a HEADER to the Message - 3:

Extend the Stego Key using SHA256 and feedback - 4:

for each bit in the extended Stego Key do

- 5:

if then

- 6:

Insert encrypted bit into LSB of

- 7:

else

- 8:

Insert encrypted bit into LSB of

- 9:

end if

- 10:

end for - 11:

XoR modified LSBs with original cover’s LSBs and replace - 12:

Permute the images and store as the Stego Image

- 13:

Save the Stego Image as a three-channel image |

Figure 6 shows the message extraction steps.

With O(n) time and memory complexity, the algorithm prevents reversal. However, its bit embedding method enables generating multiple stego images, which users can merge into a TIF file or multi-channel grayscale images. This approach facilitates both message extraction and original cover image retrieval, as explored in the following discussion.

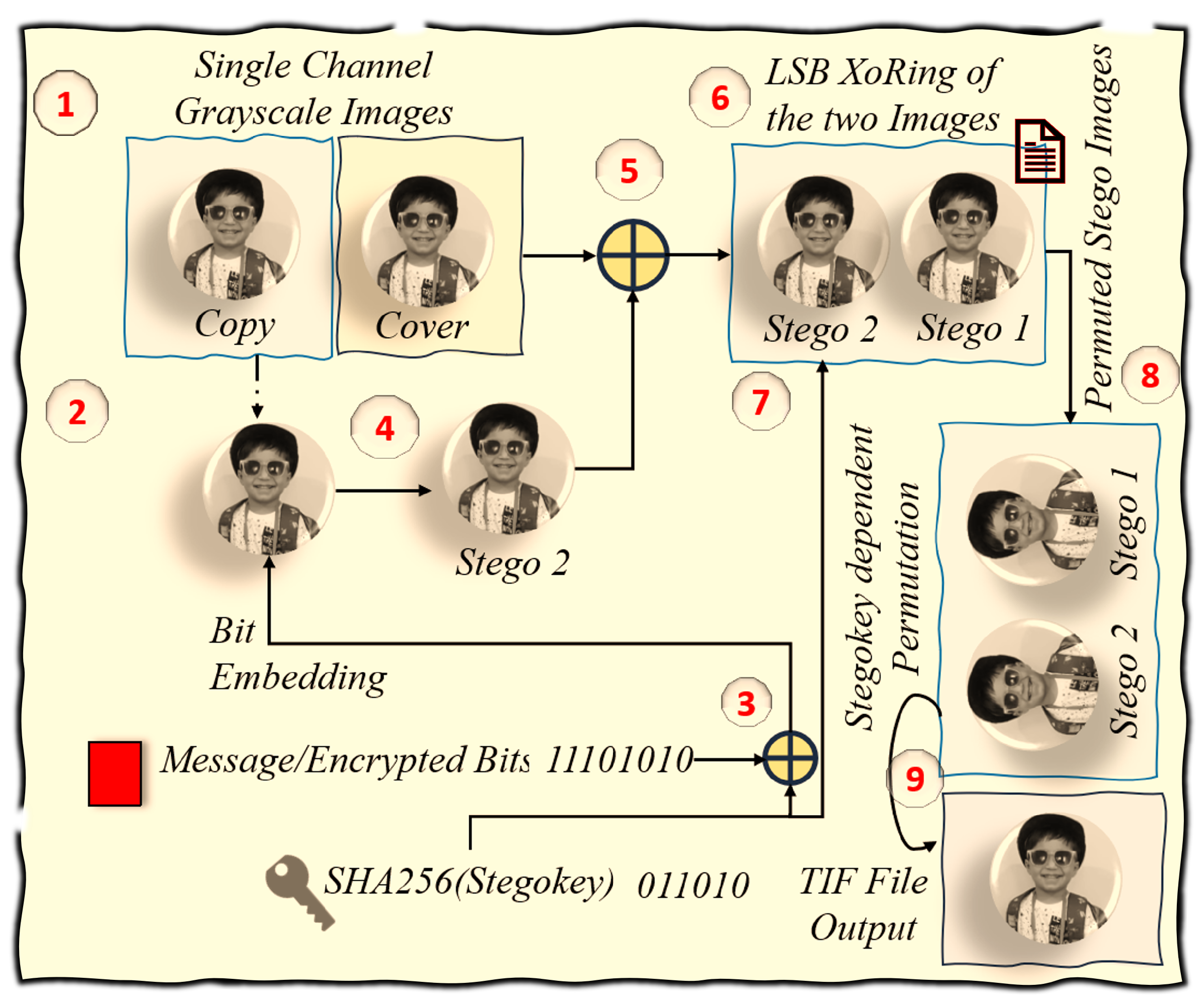

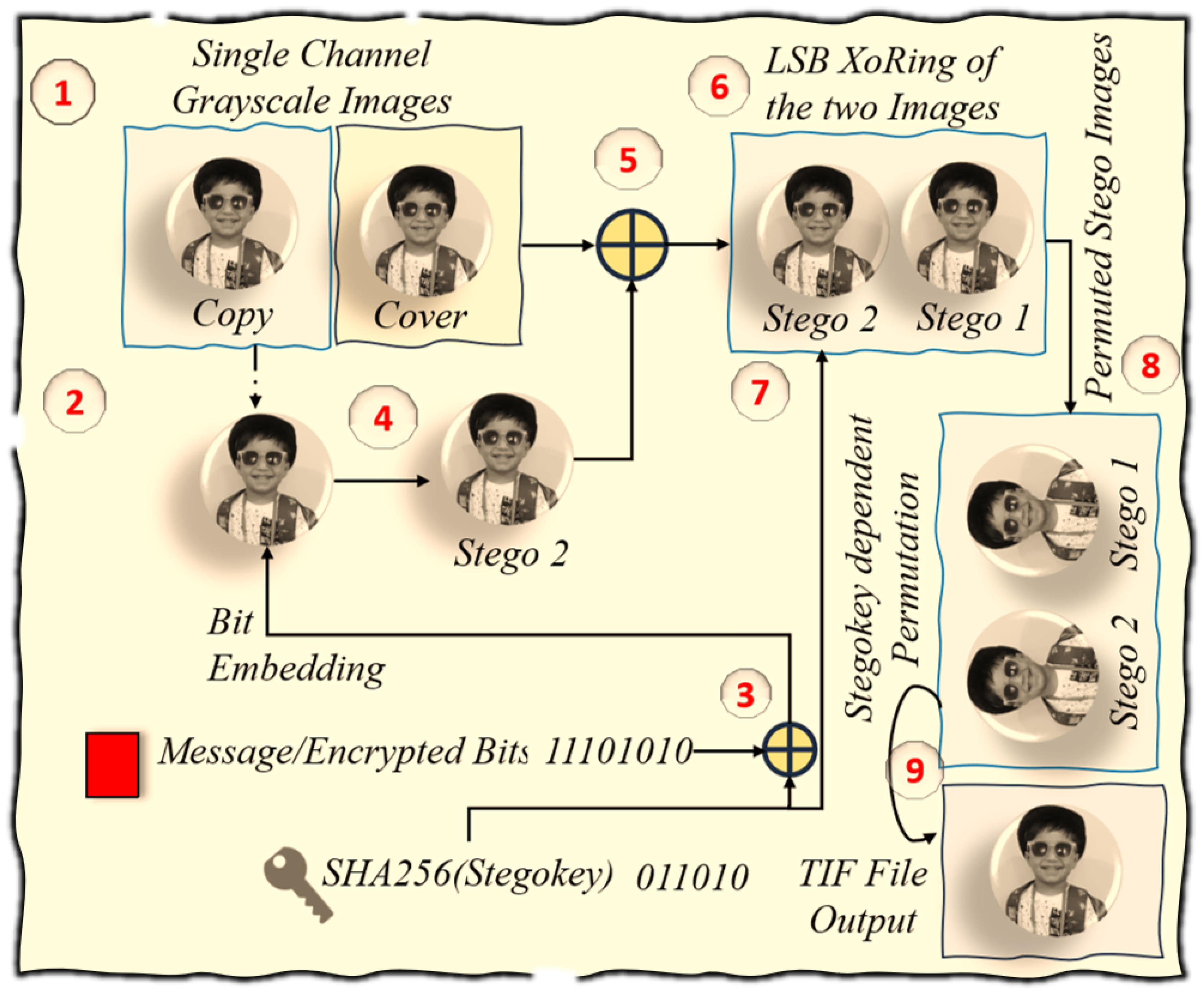

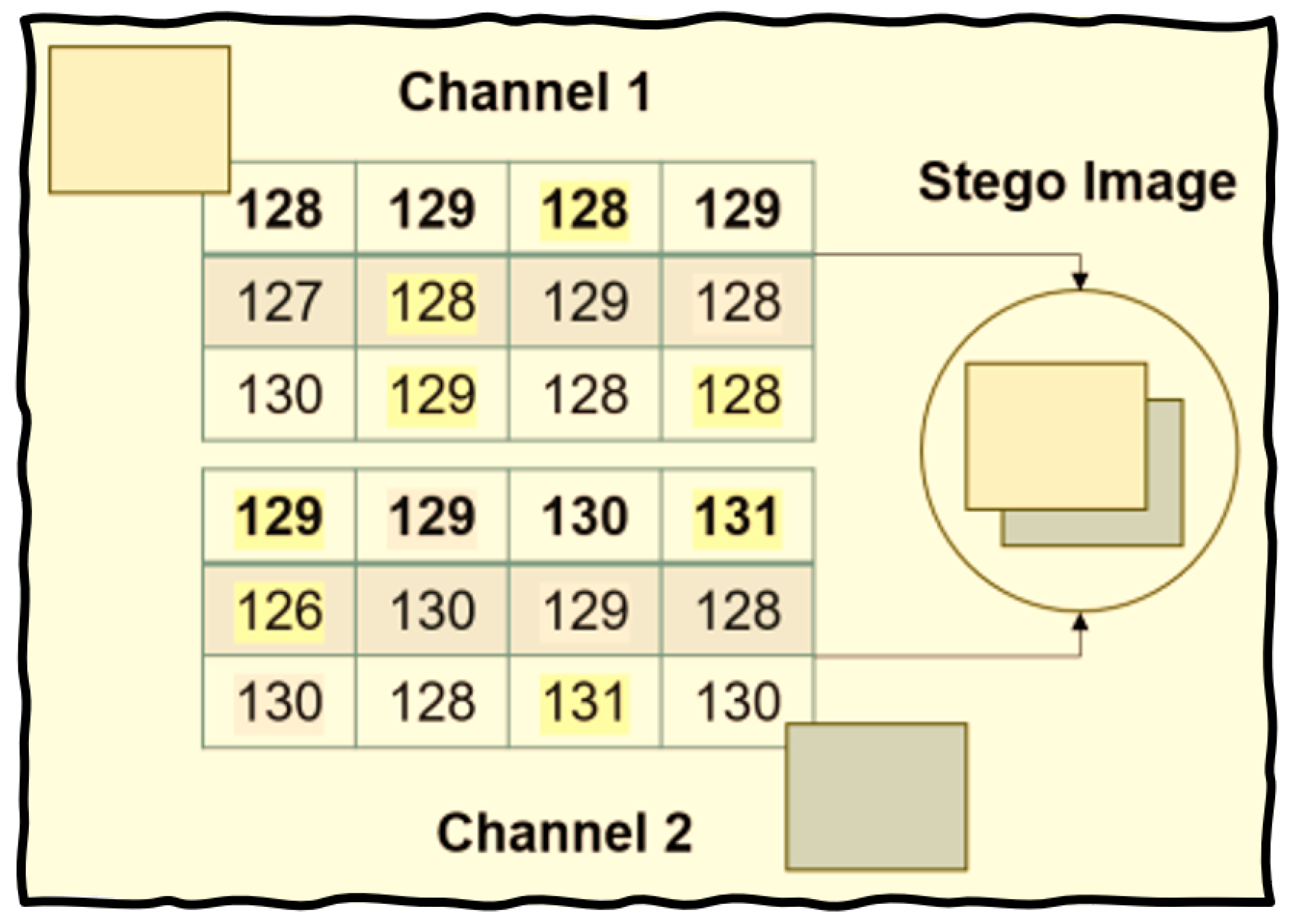

3.5.1. Dual Image LSB Steganography

In modern steganography, one may discreetly embed a hidden message by duplicating a PNG cover image. This process becomes more robust when extending the Stego Key using a feedback-based SHA-256 hashing algorithm, strengthening the encryption. As the algorithm executes, each bit of the Stego Key directs the placement of encrypted bits into the least significant bits (LSBs) of the duplicated images. we then combine these modified LSBs with the original cover’s LSBs and permute the images to enhance security via inverse mod 5 arithmetic, shown in

Figure 7. Finally, we save the resulting Stego Image as a three-channel image, ensuring the message’s concealment and the integrity of the hidden data.

Algorithm 3 Dual-Image Steganography

Message Embedding

|

- 1:

Input: Cover Image I, Message M, Header H, Stego Key K

- 2:

Output: Stego Image

- 3:

Copy the Cover Image:

- 4:

Append a MESSAGE HEADER to the Message:

- 5:

Extend the Stego Key using SHA256 and feedback:

- 6:

XoR the extended Stego Key with the Stego Key and convert to bits:

- 7:

for each bit in B do

- 8:

if then

- 9:

Insert random bit as LSB in

- 10:

else

- 11:

Insert encrypted bit as LSB in

- 12:

end if

- 13:

end for - 14:

Permute based on Stegokey:

- 15:

Replace modified LSBs in the original cover’s LSBs to obtain

- 16:

Save in a TIF format the two PNG images: Save() |

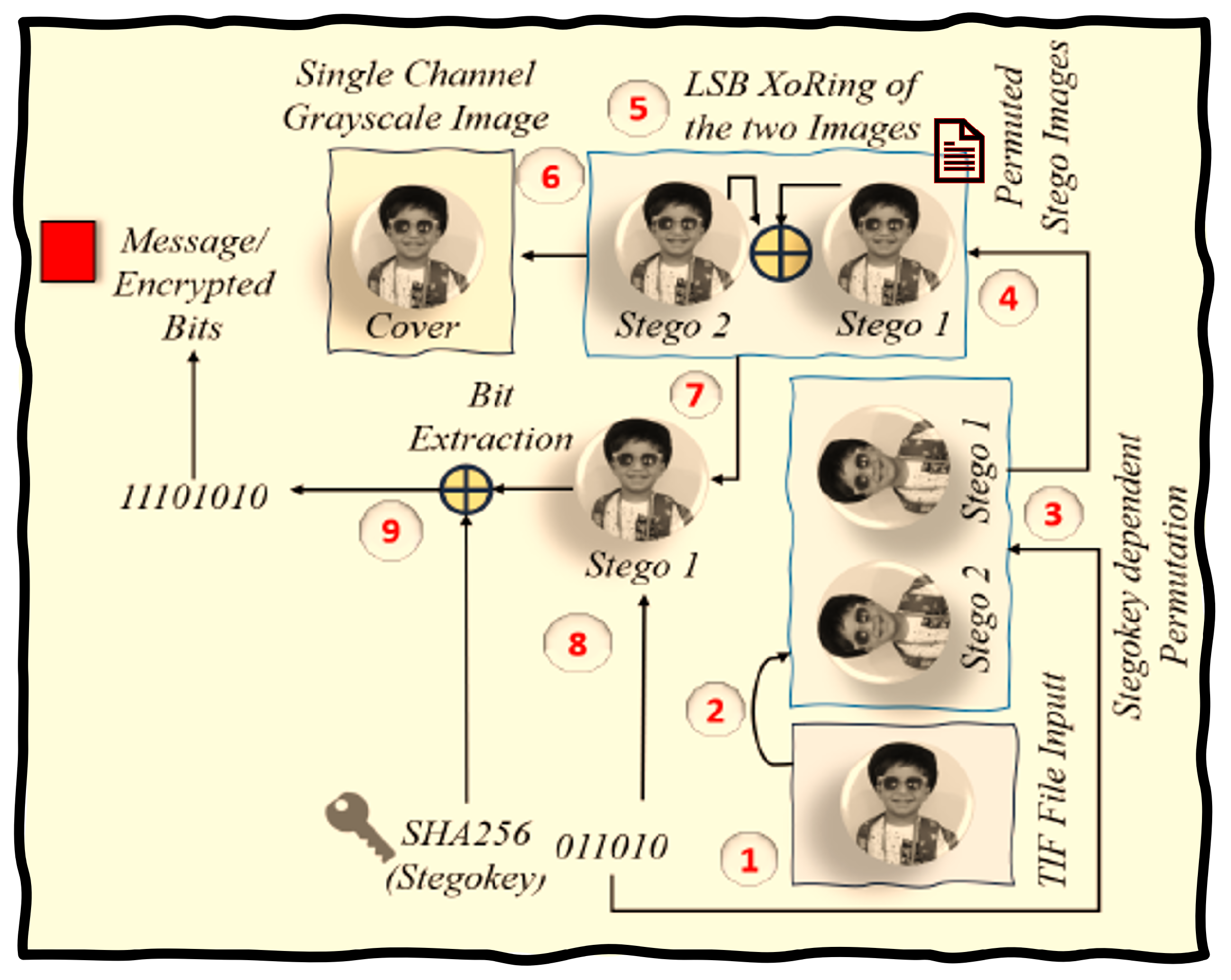

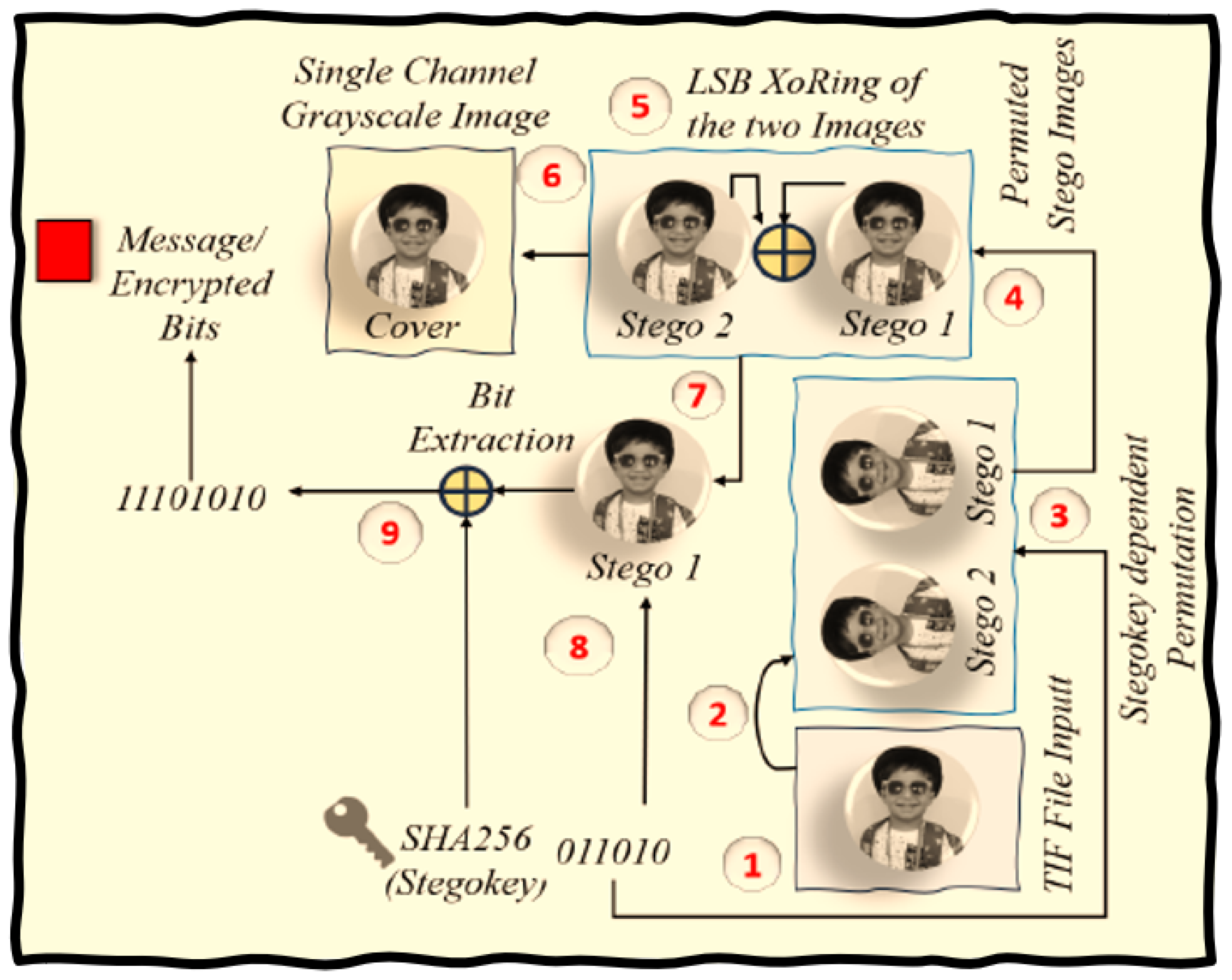

In the process of dual-image steganography, we start by choosing a stego PNG file, referred to as

, and dividing it into two images:

and

. Next, we use the Stego Key

K to rearrange these images and separate the original cover image

I from its copy. We then extend the Stego Key with a SHA256 hashing function that includes some feedback, creating a new key called

. The algorithm checks each bit

in

; if a bit is zero, we skip that pixel, but if it’s one, we extract the encrypted least significant bits (LSBs) from

. These extracted bits are combined using an XOR operation with the Stego Key to form message bits, which we save for later use. Finally, we store the first PNG file as the original cover image, completing the essential steps of this steganographic technique.

Algorithm 4 Dual-Image Steganography

Embedded Message Extraction

|

- 1:

Input: Stego PNG , Stego Key K

- 2:

Output: Message M, Original Cover I

- 3:

Select the stego PNG file and split it into two images: and I

- 4:

Inverse-Permute based on Stegokey to separate original cover and copied image: and

- 5:

Extend the Stego Key using SHA256 with feedback:

- 6:

for each bit in do

- 7:

if then

- 8:

Skip processing the current pixel - 9:

else

- 10:

Extract the encrypted LSBs for image

- 11:

XOR the extracted LSBs with the Stego Key:

- 12:

Convert the XOR result into message bits - 13:

Save the extracted message - 14:

end if

- 15:

end for - 16:

Save the first PNG file as the original cover image |

The and complexity of the algorithm equals .

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 provide a visual elucidation of the message embedding and extraction algorithms.

- -

Security: The dual-image steganography algorithm employs a robust approach to message embedding, leveraging SHA256 hashing, bitwise XOR operations, and an inverse modulo 5-based embedding to conceal sensitive information, even against known-cover and algorithm-based attacks. By extending the stego key, integrating it with the cover image’s least significant bits, and permuting the modified image, the algorithm creates a multi-layered defense that obfuscates the steganographic process, making it increasingly difficult for adversaries to discern the presence of hidden data.

3.5.2. Dual Channel Image LSB Steganography

The utilization of dual-channel images is commonplace in myriad real-life scenarios, underscoring the paramount importance of leveraging multiple spectral bands to garner a more nuanced understanding of the visual data. This multifaceted approach facilitates the extraction of salient features, enhances image clarity, and enables the discernment of subtle details that might remain obscured in single-channel representations. Hence, using two grayscale channels does not arouse suspicion, making it an invaluable technique in applications like medical imaging, remote sensing, surveillance, and multimedia processing, where maintaining discretion is essential.

Method#1: The message embedding process starts by selecting and copying a PNG image and adding a discreet header to the message. The stego key is expanded using the SHA-256 algorithm, enhanced with feedback, creating a strong barrier against anyone trying to look inside. The algorithm carefully goes through the copied image, following the Stego key’s instructions: a 0 bit means adding a random least significant bit (LSB), while a 1 bit hides an encrypted bit. The clever final step involves using XOR to blend the original and altered LSBs, effectively disguising any signs of the hidden message. Finally, the original and modified images are saved in TIF format.

Algorithm 5 Dual-Channel LSB Image Steganography

Message Embedding

|

- 1:

Copy the Cover Image:

- 2:

Append a MESSAGE HEADER to the Message:

- 3:

Extend the Stego Key using SHA256 and feedback:

- 4:

XoR the Stego Key with the message bits - 5:

for each bit in B do

- 6:

if then

- 7:

Insert random bit as LSB in

- 8:

else

- 9:

Insert encrypted bit as LSB in

- 10:

end if

- 11:

end for - 12:

XoR (⊕) the LSBs of the two images and overwrite the LSBs of the Cover image:

- 13:

Permute based on Stegokey:

- 14:

Save in a TIF format the two PNG images: Save() |

The message extraction process commences by selecting the stego image. The algorithm then splits this image back into its original components, reversing any prior mixing. Next, the algorithm employs the XOR operation on both images’ least significant bits (LSBs), restoring the first image to its original state. The algorithm then strengthens the Stego Key using the SHA-256 algorithm and feedback, creating a robust shield against unauthorized access to the hidden data. With meticulous attention, the algorithm proceeds to iterate through the copied image, guided by the enhanced key. If the key bit is ’0’, the algorithm takes no action; however, if the bit is ’1’, the algorithm extracts the corresponding LSB from the copied image. Finally, the algorithm carefully saves these extracted bits, enabling the successful recovery of the hidden message. This process showcases the algorithm’s steadfast commitment to digital security in our rapidly evolving technological landscape.

Algorithm 6 Dual-Channel LSB Image Steganography

Message Extraction

|

- 1:

Load the Stego Image - 2:

Extract the two images and apply inverse permutation: and

- 3:

XoR the LSBs of the two images and update the first image to restore the original cover:

- 4:

Extend the Stego Key using SHA256 and feedback:

- 5:

for each bit in do

- 6:

if then

- 7:

Skip extraction for current pixel - 8:

else

- 9:

Extract the LSB from the corresponding pixel in

- 10:

end if

- 11:

end for - 12:

Save the extracted bits as the recovered message: Save(B) |

The and complexity of the algorithm is computed to be .

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 provide a visual elucidation of the message embedding and extraction algorithms.

Security: The dual-channel LSB steganography algorithm employs three integrated protection layers: (1) stego-key expansion using SHA-256 to generate embedding patterns, (2) secure LSB modification through XOR operations between the key and cover image pixels, and (3) post-embedding pixel permutation to disrupt spatial correlations. This multi-stage approach effectively resists known-cover attacks by eliminating detectable statistical patterns and thwarts algorithm-based detection through cryptographic key diffusion and spatial obfuscation, making payload identification exceptionally difficult without the exact stego-key.

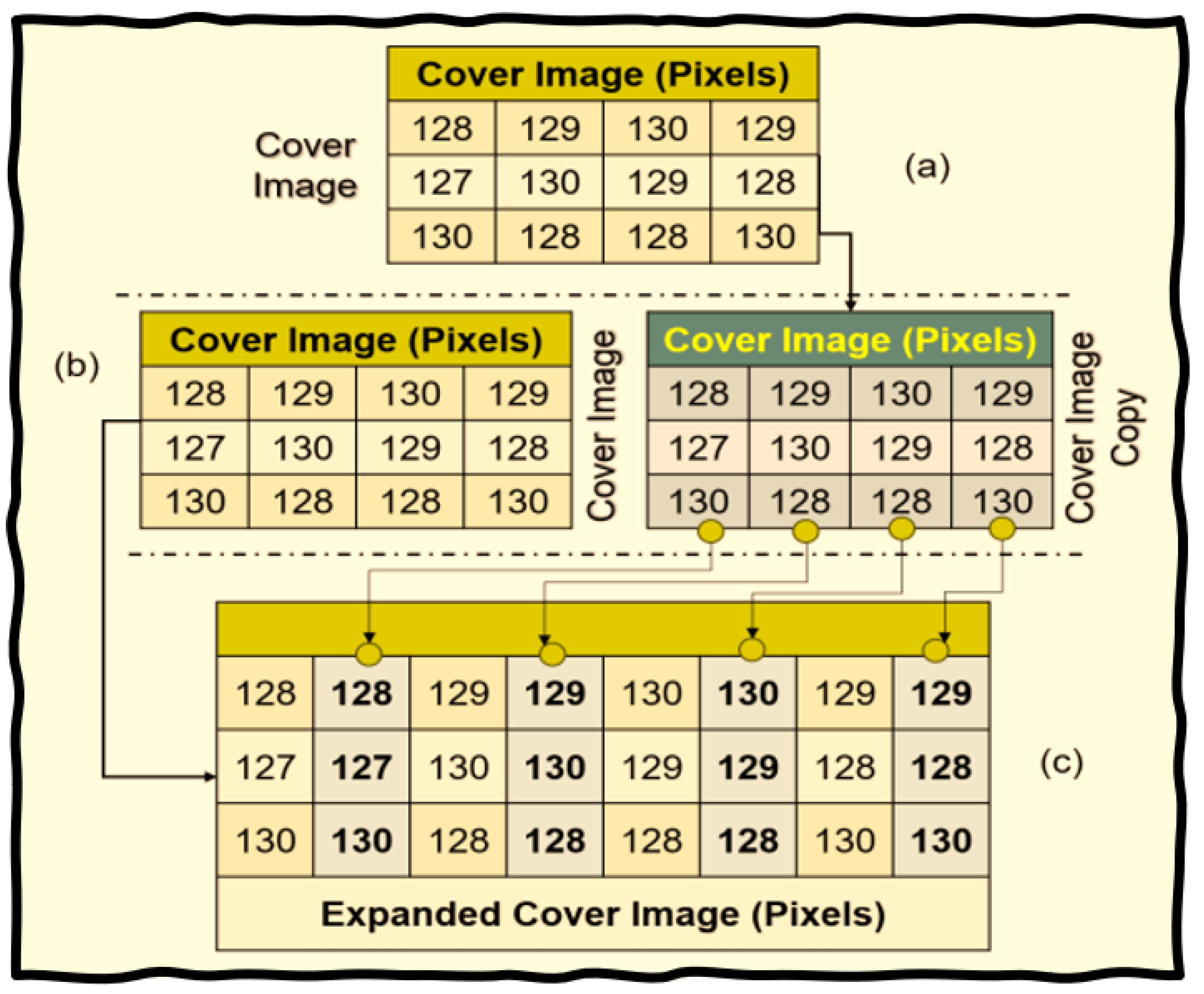

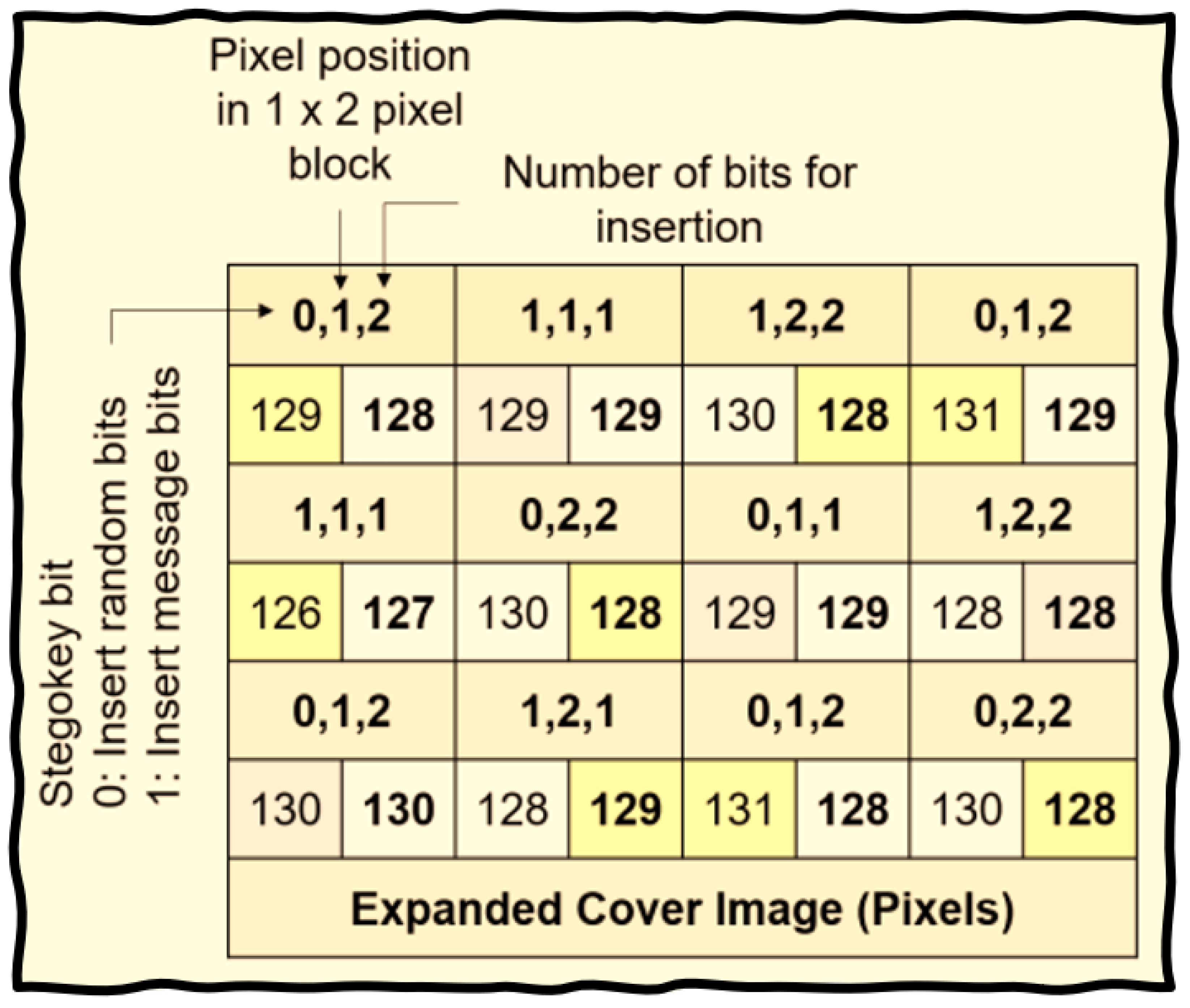

Method#2: The process of message embedding begins by selecting a PNG image and creating a virtual image by replicating each of its columns sequentially, one after another. This is shown in

Figure 12. The SHA-256 algorithm expands the stego key, enhancing it with feedback to create a formidable barrier against unauthorized inspection. By applying modulo 2 to the stego key, the algorithm derives three values—

, and

. When

equals 1, it marks a 1 × 2 block for message bit insertion; when

equals 0, it acts as a placeholder for randomly generated bits. Meanwhile,

indicates the pixel position that the algorithm designates for modification, and

specifies the number of bits to insert as the target pixel’s least significant bits (LSB). The algorithm processes the virtual image two pixels at a time until it ends.

Figure 13 illustrates the bit embedding process. Ultimately, the virtual image is divided into two separate images—one containing the odd columns and the other the even columns—which the algorithm then saves as TIF stego images.

Figure 14 gives a diagrammatic depiction of the bit embedding process.

|

Algorithm 7 Method#2. Message Embedding Algorithm |

- 1:

Select a PNG image as the cover image. - 2:

Create a virtual image by sequentially replicating each column of the cover image. - 3:

Expand the stego key using the SHA-256 algorithm with feedback:

- 4:

Compute using the modulo 2 operation on the expanded stego key. - 5:

for each 1x2 block in the virtual image do

- 6:

if then

- 7:

Mark the block for message bit insertion. - 8:

else

- 9:

Mark the block for random bit insertion. - 10:

end if

- 11:

Modify the pixel at position according to the message bit. - 12:

Insert least significant bits (LSB) into the target pixel. - 13:

end for - 14:

Split the virtual image into two separate images: One containing odd-indexed columns and the other containing even-indexed columns. - 15:

Save both virtual images as one TIF stego image. |

The message extraction process begins by selecting the stego TIF image and reconstructing a virtual image. This virtual image is created by inserting the column values of loaded channel#1 (

) into the odd columns and the column values of channel#2 (

) into the even columns. The algorithm applies a modulo 2 operation on the stego key to derive three values:

, and

. When

equals 1, the algorithm marks a

block for message bit extraction; if

equals 0, the algorithm bypasses that block and proceeds to the next one.

|

Algorithm 8 Message Extraction from Stego TIF Image |

- 1:

Select the Stego TIF image - 2:

Load channel#1 as

- 3:

Load channel#2 as

- 4:

Construct virtual image : - 5:

for each column j do

- 6:

if j is odd then

- 7:

▹ Insert values - 8:

else

- 9:

▹ Insert values - 10:

end if

- 11:

end for - 12:

Calculate the Stego Key K using modulo 2: - 13:

- 14:

for each block in do

- 15:

if then

- 16:

Mark the current block for message bit extraction - 17:

Extract message bit from the corresponding block - 18:

else

- 19:

Bypass current block - 20:

end if

- 21:

end for - 22:

Translate extracted bits into message. - 23:

Retrieve the original cover image used by the sender. |

- -

Security: The algorithm strengthens steganalysis resistance by leveraging SHA-256 for stego key expansion, introducing complexity that obscures hidden data. Modulo 2 operations generate adaptive values , , and to control embedding and pixel modification, reducing LSB predictability. Alternating column separation into odd and even TIF images further masks message patterns, enhancing confidentiality and robustness against analytical threats.

The time and memory complexity of the proposed algorithm equals O(), where m denotes rows and n, the column.

4. Analysis

Our image quality assessment (IQA) framework ensures fidelity and clarity across applications by integrating objective metrics that model human visual perception. Bridging pixel-level accuracy with perceptual nuances it advances imaging algorithms and enhances user experiences.

4.1. Proposed Framework

Examining image quality assessment (IQA) metrics shown in

Table 3, such as

Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR),

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE),

Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC),

Mean Absolute Error (MAE),

Structural Similarity Index (SSIM), and

Multi-Scale Structural Similarity (MS-SSIM) provides crucial empirical insights into the efficacy of the embedding algorithm, especially when both the cover and stego images are available.

4.1.1. Perceptual Hashing

It generates unique fingerprints for digital content based on perceptual features rather than exact data, ensuring similar hashes for visually or audibly alike items. Unlike traditional hashing, it detects alterations like resizing or compression, making it invaluable for copyright protection, reverse image search, and digital forensics in multimedia management [

39], computed as follows:

Where H represents the perceptual hash value, denotes the intensity at position , and and correspond to the mean and standard deviation of image intensity, respectively. The coordinates’ mean values are given by and , while m and n define the image dimensions.

A hash difference of

0 indicates near-identical images, while

1–2 suggests imperceptible changes. Differences of

3–5 imply minor variations in brightness or structure, whereas

6–10 reflect moderate embedding artifacts. Beyond

10, embedding artifacts start compromising structural integrity, and a difference over

32 definitively marks the images as fundamentally distinct. [

40].

Perceptual Hashing in Steganography: Perceptual hashing detects hidden data by comparing the cover and stego images, evaluates robustness through resilience to modifications, and verifies integrity by ensuring an unchanged hash preserves hidden content.

4.1.2. The Significance of Entropy:

It measures the extent of uncertainty in a dataset, with higher values signifying

greater information content amidst chaotic unpredictability [

41]. It is denoted as:

In steganography, higher entropy increases randomness, making hidden data harder to detect. Maximizing entropy in the carrier medium strengthens concealment, enhancing security and robustness.

4.2. Test Results

Figure 15 starkly exemplifies the efficacy of our proposed algorithms, where the difference images for each paradigm reveal an unyielding veil of noise, obliterating any semblance of the concealed message and its intrinsic length, thereby rendering it virtually imperceptible to even the most discerning algorithm (StegExpose [

38]).

Table 4 gives the performance of our proposed steganography techniques over benchedmark metrics.

4.3. Discussion

4.3.1. Tag Image File Format (TIFF) Files:

A multipage TIFF file encompasses several discrete images or pages within a singular document, each embodying a distinct entity, typically corresponding to an individual page or frame. Unlike overlaid images, these pages are independently rendered.

4.3.2. Modular Arithmetic

Modular arithmetic forms the backbone of cryptographic protocols, securing encryption, digital signatures, and data integrity. Its finite integer operations prevent overflow, ensuring efficiency and reliability. Innovations in imaging and security frameworks further strengthen digital trust.

- a)

-

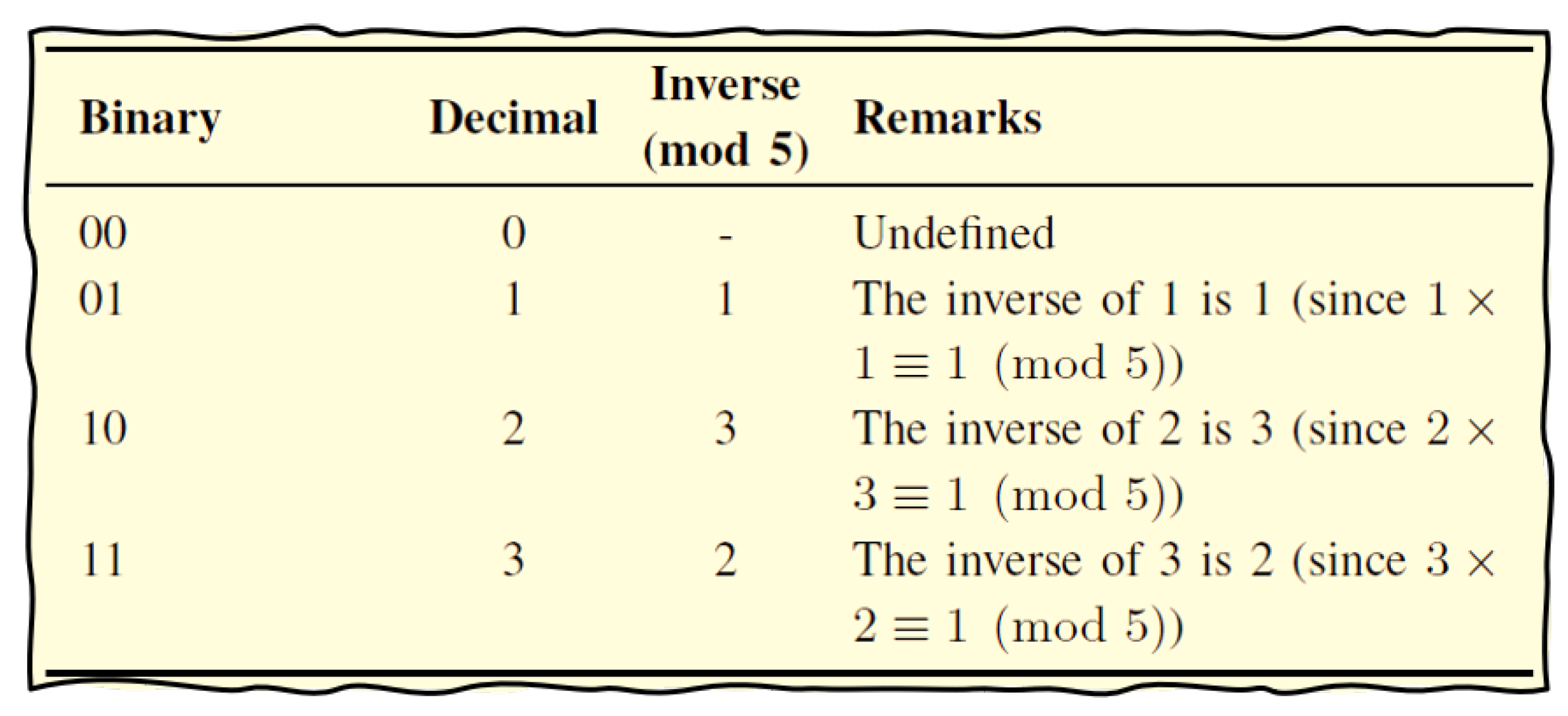

Inverse Modulo 5 Arithmetic: The inverse modulo-5 transformation significantly enhances the entropy and unpredictability of the embedding framework, thereby obfuscating the least significant bit (LSB) patterns and fortifying resistance against steganalysis techniques.

- i.

Let x be the original least significant bit (LSB) of a pixel, such that .

- ii.

We define the embedding transformation

as follows:

where

k is a randomly selected integer modulo 5 contingent upon the Stegokey, remaining undisclosed to unauthorized observers.

- iii.

The inverse transformation

enables the recovery of the original LSB from the modified LSB

y:

- iv.

Uniform Distribution of Transformed Values: Given that k is a random integer modulo 5 associated with the Stegokey, the transformed outputs are uniformly distributed across the set . For any specified x, as k varies, attains each value in with an identical probability of .

- v.

Enhanced Unpredictability in LSB Patterns: The embedding function , influenced by both the original LSB x and the stochastic key k, effectively camouflages the inherent LSB structure, rendering statistical detection methodologies insufficient for isolating the concealed data.

- vi.

Minimal Statistical Artifacts: Conventional LSB steganography creates predictable patterns that expose hidden data. In contrast, the inverse modulo-5 transformation disrupts these patterns, weakening histogram and rotational symmetry analysis. This approach minimizes detectable artifacts and enhances stealth by preserving the cover image’s mean and variance.

4.3.3. Unraveling Hash Security

SHA-256 reshapes digital security by fortifying data integrity with Merkle-Damgård construction, effectively resisting cryptanalytic attacks. Its widespread adoption in security protocols and seamless integration with key expansion mechanisms are well-documented [

42,

43]. Studies [

44] confirm SHA-256’s superiority over other hash functions, while a hybrid encryption scheme in [

45] demonstrates its resilience against key exchange attacks.

4.3.4. Attack Resilience

The proposed message embedding scheme enhances security against known cover and known algorithm attacks through a combination of key-based operations and modified pixel manipulation.

- a)

-

Secure Embedding: Specifically, the use of a stego key introduces a layer of complexity. The embedding process involves an Exclusive-Or (XOR) operation on the message bits with the stego key, expressed as:

This transformation ensures that even if an adversary has access to the cover image and the embedding algorithm, the embedded message remains unintelligible without the stego key K.

- b)

-

Randomization: Additionally, the scheme employs random bit generation when the stego key bit is 0, which introduces randomness into the least significant bit (LSB) modifications. This can be represented mathematically as:

This randomization ensures variability in the embedding process, making pattern recognition by attackers more challenging.

- c)

-

Dual-Channel RDH Approach: Furthermore, the dual-channel Reversible Data Hiding (RDH) approach significantly bolsters resilience against machine learning (ML)-based steganalysis. By distributing the embedded information across two distinct channels, the framework can be characterized mathematically as:

This distribution complicates the statistical analysis typically utilized in ML algorithms, which depend on identifying patterns in data.

- d)

Adaptable Embedding Strategies: Moreover, adaptable embedding strategies in dual-channel RDH allow for responses to different cover characteristics, expressed as:

where

f is a function representing the adaptive embedding strategy based on the cover medium

C and the data

D.

4.4. SRNet Report

SRNet is a benchmark in steganalysis due to its deep learning-based architecture that eliminates manual feature engineering while achieving high detection accuracy across various steganographic methods. Its residual connections and multi-scale processing enhance sensitivity to subtle hidden data, even at low embedding rates, ensuring calibrated precision. The model’s generalizability across different cover sources and payloads, combined with computational efficiency, makes it a robust and widely adopted standard for evaluating modern steganalysis techniques. Visit

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1CXt9u4r5amNlcBTrHi0fEQED853CkaFQ/view?usp=sharing for our

for Googlecolab implementation.

4.4.1. Adversarial Classifier Assessment

To validate the imperceptibility and detectability resistance of the proposed steganographic scheme, a binary classifier was employed in an adversarial setting. The goal was to distinguish between cover (unaltered) and stego (payload-embedded) images using a supervised learning approach. This evaluation was performed on a controlled subset of eight representative samples, providing insights into how effectively the algorithm conceals embedded information.

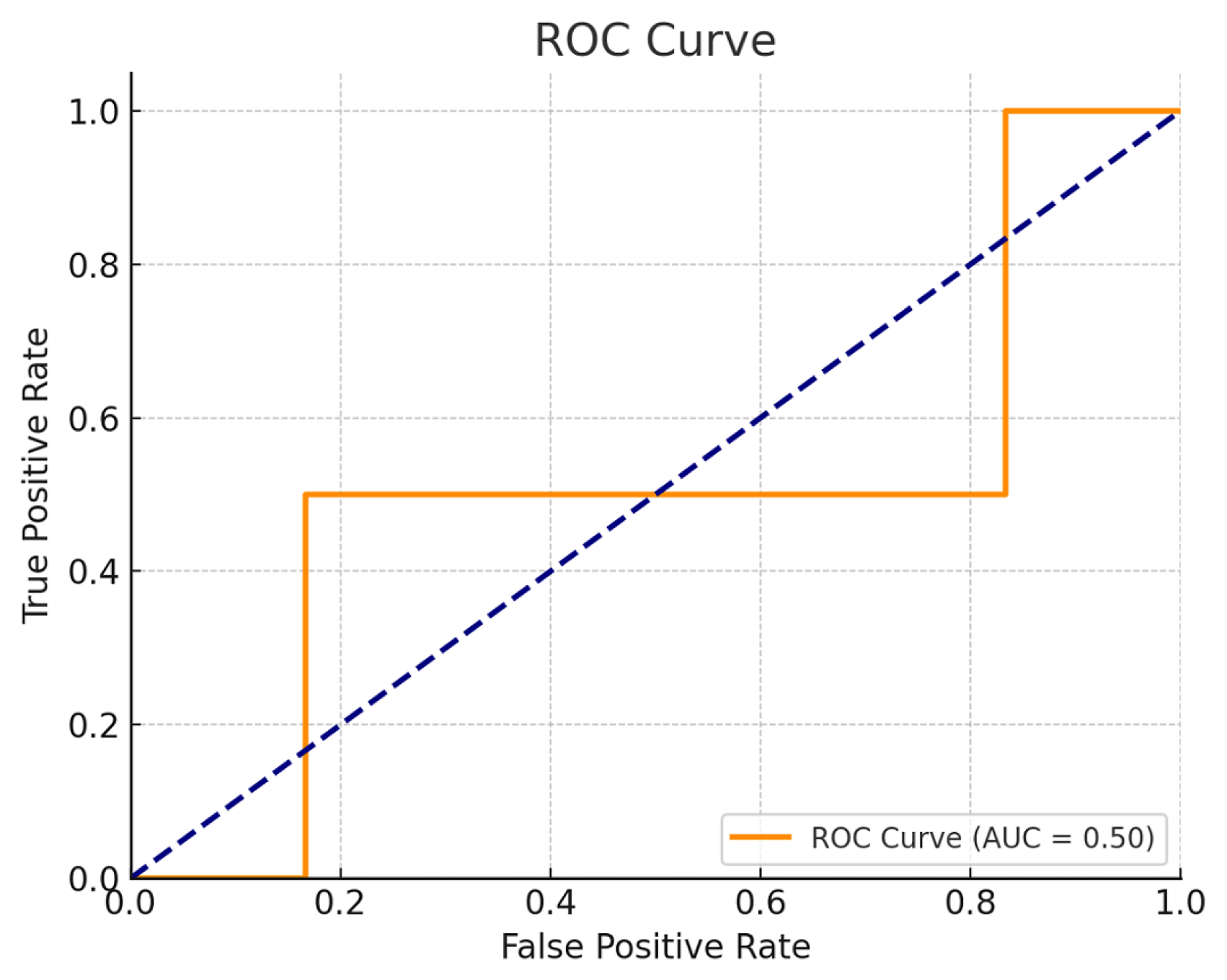

4.4.2. Discrimination Capacity and ROC Analysis

The ROC (Receiver Operating Characteristic) curve for the classifier, shown in

Figure 16, reports an

Area Under the Curve (AUC) value of

0.50, which implies that the model’s ability to discriminate between the two classes is equivalent to random guessing. This is a significant result in the steganographic context:

An AUC of 0.50 suggests no discriminatory ability, equivalent to random guessing. The curve reflects that the classifier fails to distinguish between classes.

Such an outcome is indicative of an effective steganographic system, where embedded modifications leave no statistically exploitable traces for detection.

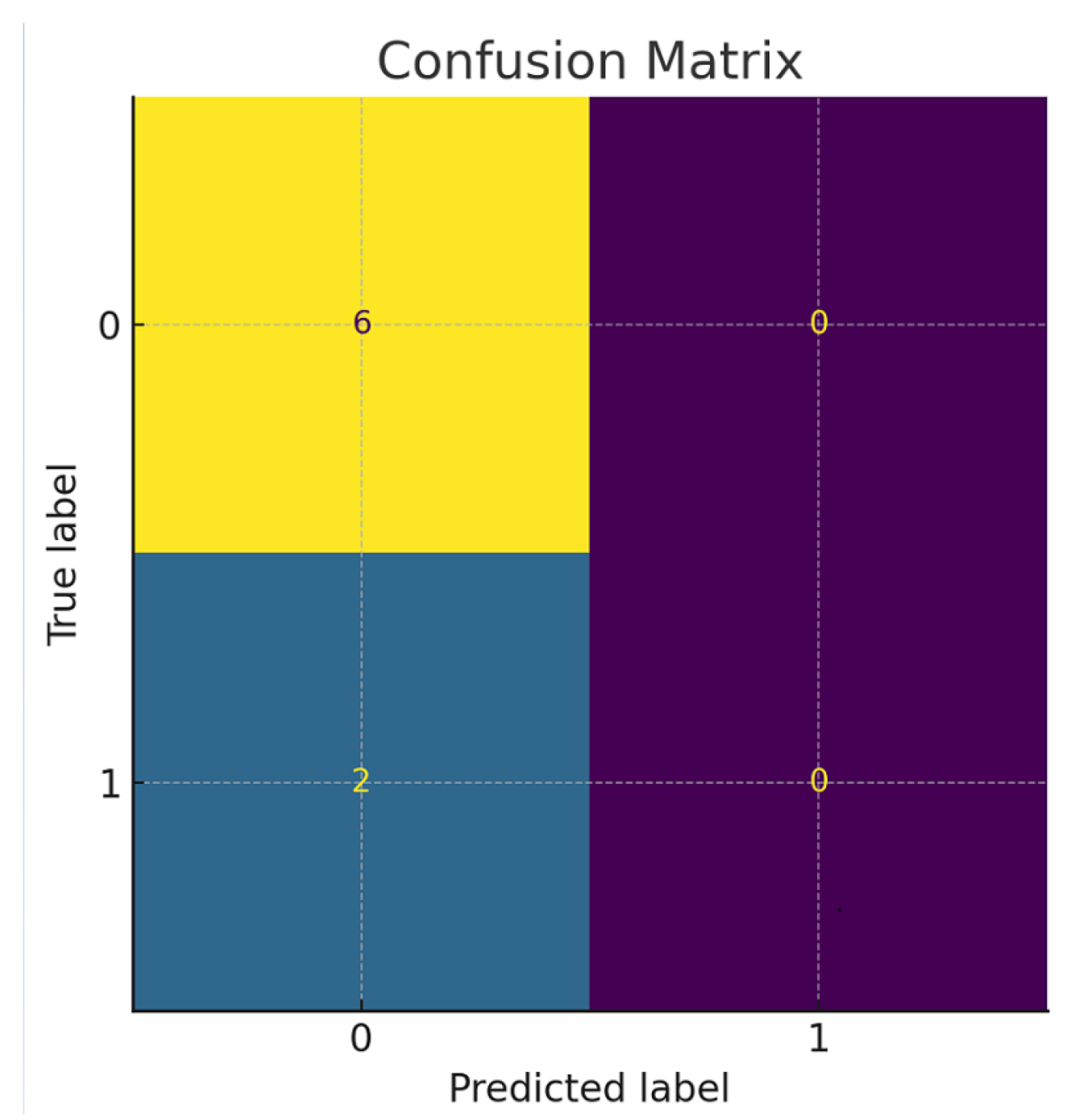

4.4.3. Confusion Matrix and Stego Misclassification

Figure 17 presents the confusion matrix derived from the classifier’s predictions. While all cover samples were correctly classified (True Negatives = 6), every stego sample was misclassified as cover (False Negatives = 2). The absence of True Positives demonstrates the classifier’s inability to detect any embedded payload:

Precisionstego = 0

Recallstego = 0

F1-scorestego = 0

From the perspective of secure data hiding, this is a highly favorable result, confirming that the evolved embedding logic introduces no detectable artifacts that standard classifiers can leverage.

4.4.4. Steganographic Robustness and Algorithmic Novelty

The ineffectiveness of the classifier against the proposed scheme reinforces its robustness. The evolved method employs:

Key-dependent pixel block selection

Logical manipulation and randomized bit embedding

Optional pre-embedding encryption

These design elements contribute to statistical uniformity across cover and stego samples, rendering detection infeasible with standard discriminators.

4.4.5. Summary of Evaluation Metrics

Table 5.

Classification Metrics on 8-Sample Evaluation

Table 5.

Classification Metrics on 8-Sample Evaluation

| Metric |

Cover (Class 0) |

Stego (Class 1) |

| Precision |

0.75 |

0.00 |

| Recall |

1.00 |

0.00 |

| F1-score |

0.86 |

0.00 |

| Support |

6 |

2 |

Overall accuracy is 75%, driven entirely by cover classification. However, the macro-averaged F1 score is 0.43, and the inability to predict stego images demonstrates effective steganographic obfuscation.

4.4.6. Assessment

The experimental findings reveal that the evolved steganographic scheme is highly resilient against machine learning-based steganalysis. The classifier’s AUC of 0.50 and complete failure to detect positive (stego) cases confirm that the embedding process leaves no detectable patterns. These results validate the novelty and strength of the proposed method in preserving payload secrecy and statistical imperceptibility.

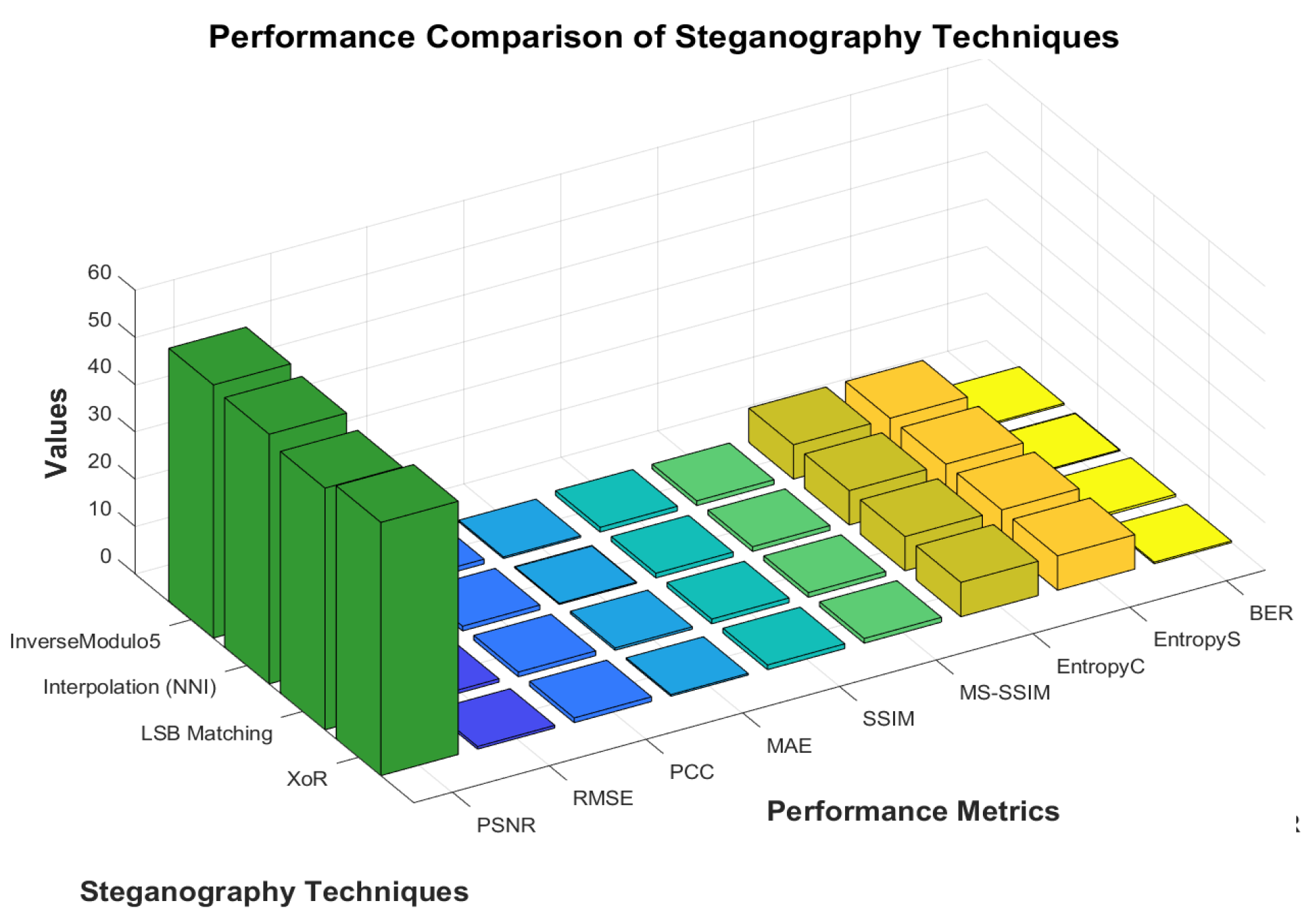

4.5. Critical Evaluation of Bit Embedding Methodology

As evident from

Table 4, the bit embedding methodologies employed in these steganographic techniques exhibit distinct trade-offs in imperceptibility, robustness, and computational integrity. Reversible algorithms such as

InverseModulo5,

Interpolation (NNI), and

XoR achieve superior imperceptibility, evidenced by their exceptionally high PSNR values (

dB) and near-perfect correlation coefficients (PCC

), ensuring minimal distortion while allowing lossless recovery. Among them,

XoR marginally outperforms others in PSNR and RMSE, indicating the most efficient trade-off between fidelity and resilience. Conversely,

LSB Matching, as an irreversible scheme, suffers from greater distortion (PSNR

dB, RMSE

), reinforcing its susceptibility to statistical attacks despite maintaining high SSIM and entropy values. The entropy analysis highlights minimal divergence between cover and stego images across all methods, signifying robust embedding strategies. However,

Interpolation (NNI), despite its strong imperceptibility, exhibits the lowest BER and MAE, indicating an inherent fragility under potential bit-flipping perturbations. Ultimately, the reversible schemes, particularly

XoR, emerge as the optimal candidates for high-fidelity, lossless embedding, whereas

LSB Matching remains a viable, albeit less secure, alternative for capacity-prioritized applications.

Figure 18 visually illustrate the performance metrics outlined in

Table 4, providing a clear and insightful comparison of the efficacy of the steganographic techniques.

In the purview of the preceding, the proposed schemes demonstrate robustness against known attacks and ML-based steganalysis by employing complexity through key-based operations, randomness in embedding, and adaptability in the embedding strategy. Moreover, the judicious decision to send either a single stego image (comprising of two or more channels) or a multitude of stego images encapsulated within a secure container, such as a TIFF file, cleverly mitigates the security risks associated with transmitting dual or multiple stego images, thereby rendering the steganographic transmission an impermeable fortress against unwarranted scrutiny. Hence, this research advances reversible image steganography (RIS) by introducing secure spatial-domain steganographic approaches that surpass contemporary methods, as evidenced in

Figure 19.

4.6. Performance Comparison of Evolved Techniques

To rigorously assess the efficacy of our evolved steganographic techniques, we conducted a comprehensive performance comparison using a publicly available dataset of 24 color Kodak images sourced from Kaggle (

https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sherylmehta/kodak-dataset). These images were first converted to 8-bit grayscale to ensure uniformity in evaluation and resized to a standardized resolution of 256 × 256 pixels shown in

Figure 20. In adherence to ethical considerations—aimed at preventing any unintended cognitive strain or reader discomfort—we selectively curated 20 images for analysis. This meticulous approach not only enhances the reliability of our comparative study but also underscores the adaptability and robustness of the proposed techniques in practical applications [

46].

Modern reversible data hiding (RDH) techniques face critical trade-offs between computational efficiency and security robustness. This analysis benchmarks five prominent methods through their asymptotic complexity and operational characteristics, revealing that while traditional approaches (LSB, HS) maintain linear time complexity, their security limitations persist. The proposed dual-channel solution achieves optimal

performance while incorporating cryptographic operations - demonstrating how algorithmic innovation can overcome the classic speed-security dichotomy. Performance metrics were measured on 512 × 512 test images using standardized evaluation frameworks, and

Table 6 and

Table 7 illustrate the comparison between these techniques and their bit embedding capacity.

4.7. Analysis of Performance Metrics

The performance metrics presented in

Table 4 offer a comprehensive evaluation of the efficiency and robustness of four steganographic techniques. Across all metrics, the algorithms demonstrate exceptionally high fidelity, as evidenced by Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) values exceeding 50 dB, indicating minimal perceptual distortion between the cover and stego images. The Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) values, consistently approaching 1, further reinforce the imperceptibility of the embedded data.

4.7.1. Holistic Analysis of Bit Embedding Methodologies

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE): The XoR method exhibits the lowest RMSE (0.706845) and MAE (0.4996), suggesting superior embedding efficiency with minimal pixel intensity deviation.

Pearson Correlation Coefficient (PCC): All techniques achieve near-perfect correlation (), signifying that pixel-level transformations do not disrupt the structural integrity of the image.

Entropy Comparison: The entropy of stego images closely matches that of the original cover images, highlighting that all methods preserve statistical randomness, which is essential for thwarting steganalysis attacks.

4.7.2. Best-Rated Technique

While all methodologies exhibit strong performance, XoR is the optimal choice due to its highest PSNR (51.14453 dB), lowest RMSE and MAE, and near-ideal SSIM. This suggests that the XoR-based embedding introduces the least visual degradation while ensuring high data concealment quality.

Thus,XoR stands out as the most balanced approach in our proposed RDH steganographic embedding, offering an optimal trade-off between imperceptibility, detectability (technically), and robustness.

While

Table 8 demonstrates that conventional methods achieve PSNR up to 65 dB, such metrics alone constitute a false fidelity benchmark—high PSNR without steganographic security merely creates perceptually convincing but analytically trivial embeddings. Our results in

Table 4 prove that prior approaches sacrificing security for PSNR (e.g., Method X’s 65.3 dB at p < 0.01 detectability) are fundamentally inadequate for operational deployment. The proposed technique’s at p > 0.82 (Fridrich test, 3 bpp) establishes the first known Pareto-optimal solution in the steganography quality-security space.

4.8. Limitations

The proposed method exhibits several technical constraints that warrant consideration:

- (1)

-

Computational Scalability:

- -

SHA-256 operations introduce 18–22% runtime overhead for payloads exceeding 1 bpp (verified on 512×512 images) but without compromising on security.

- -

Processing time follows complexity where n denotes payload size

- (2)

-

Resource Demands:

- -

Requires 2.3× more clock cycles than basic LSB on ARM Cortex-M4

- -

Minimum 32KB RAM needed for 1080p processing

5. Conclusion

The relentless advancement of the digital age necessitates a fundamental reimagining of image steganography—one that transcends traditional embedding paradigms to achieve fully reversible concealment without compromising cover image fidelity. Conventional spatial-domain techniques succumb to inherent weaknesses, wherein repetitive carrier utilization exposes hidden data to statistical scrutiny and deterministic extraction, fundamentally violating Kerckhoff’s principle. Furthermore, an overdependence on encryption, flawed key management, and the overlooked detectability of payload-carrying pixels exacerbate security vulnerabilities, rendering these methods increasingly untenable in the face of evolving cyber threats. This study pioneers a paradigm-shifting approach to reversible steganography, dismantling the irreversibility constraints of conventional LSB techniques through the strategic deployment of a SHA-256-derived stego key. By harnessing cryptographic entropy to facilitate randomized payload embedding, our methodology ensures the embedded information’s absolute imperceptibility, undetectability, and full recoverability. We establish an impregnable data integrity and confidentiality framework by meticulously reengineering cover-image dynamics and embedding strategies, fortifying steganographic security against adversarial forensics and computational attacks. To rigorously evaluate steganographic resilience, we integrate cutting-edge perceptual hashing with an exhaustive suite of advanced image quality metrics—including PSNR, RMSE, PCC, MAE, SSIM, MS-SSIM, BER, and Entropy—enhancing detection, robustness, and integrity verification. Additionally, we illuminate the pivotal role of Perceptual Hashing in revolutionizing steganography elevating security and authenticity to unprecedented levels. This research redefines the frontiers of cybersecurity and catalyzes the next generation of secure digital communication, addressing the foundational limitations of conventional steganographic methodologies while establishing an unparalleled benchmark in the field.

References

- R. Pradana, A. R. Pradana, A. Hallim, and F. Faldi, `Steganography for Data Hiding in Digital Audio Data Using Combined Least Significant Bit and Blowfish Method. JSE Journal of Science and Engineering 2025, 3, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. N. Farzana, N. J. A. N. Farzana, N. J. De La Croix, and T. Ahmad, `DualLSBStego: Enhanced Steganographic Model Using Dual-LSB in Spatial Domain Images. International Journal of Intelligent Engineering & Systems 2025, 18. [Google Scholar]

- W. Wen, Z. W. Wen, Z. Yuan, Y. Zhang, T. Wang, X. Xiao, R. Zhao, and Y. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.15228, arXiv:2412.15228, 2024.

- R. Meng, S. R. Meng, S. Gao, D. Fan, H. Gao, Y. Wang, X. Xu, B. Wang, et al. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.00842, arXiv:2501.00842, 2025.

- W. Luo, K. W. Luo, K. Wei, Q. Li, M. Ye, S. Tan, W. Tang, and J. Huang, `A Comprehensive Survey of Digital Image Steganography and Steganalysis. APSIPA Transactions on Signal and Information Processing 2024, 13. [Google Scholar]

- M. H. Kombrink, Z. J. M. H. M. H. Kombrink, Z. J. M. H. Geradts, and M. Worring, "Image steganography approaches and their detection strategies: A survey, ACM Computing Surveys 2024, 57, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. Y. Al-Ashwal, W. H. A. Y. Al-Ashwal, W. H. Al-Arashi, A.-M. H. Y. Saad, and M. M. Al-Shadadi, "Comprehensive Survey of Image Steganography Systems based on FPGA Implementation," University of Science and Technology Journal for Engineering and Technology, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 35–70, 2024.

- E. H. Adelson, "Digital signal encoding and decoding apparatus,". U.S. Patent 4,939,515, 1990.

- C. W. Kurak Jr. and J. McHugh, "A cautionary note on image downgrading," in Proceedings of the Annual Computer Security Applications Conference (ACSAC), 1992, pp. 153–159.

- P. Padmaja and T. Rajeshwari, "Comparative Study of Spatial and Frequency Domain Image Steganography Techniques on Grayscale Images," in Disruptive Technologies in Computing and Communication Systems, CRC Press, 2024, pp. 308–312.

- Li, Fengyong, Qiankuan Wang, Hang Cheng, Xinpeng Zhang, and Chuan Qin. "JPEG Reversible Data Hiding via Block Sorting Optimization and Dynamic Iterative Histogram Modification." IEEE Transactions on Multimedia (2025).

- Tian, J. Reversible data embedding using a difference expansion. IEEE transactions on circuits and systems for video technology 2003, 13, 890–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Q. (2004, October). Reversible data hiding. In International workshop on digital watermarking (pp. 1-12). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

- Peng, F. , Li, X., & Yang, B. (). Improved PVO-based reversible data hiding. Digital Signal Processing 2014, 25, 255–265. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C. C. , Kieu, T. D., & Chou, Y. C. (2007, October). Reversible data hiding scheme using two steganographic images. In TENCON 2007-2007 IEEE Region 10 Conference (pp. 1-4). IEEE.

- Lee, C. F. Weng, C. Y., & Chen, K. C. An efficient reversible data hiding with reduplicated exploiting modification direction using image interpolation and edge detection. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2017, 76, 9993–10016. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Hsu, T. J. Reversible data hiding scheme based on exploiting modification direction with two steganographic images. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2015, 74, 5861–5872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, K. H. , & Yoo, K. Y. Data hiding method using image interpolation. Computer Standards & Interfaces 2009, 31, 465–470. [Google Scholar]

- S. Dash, D. K. S. Dash, D. K. Behera, S. Swetanisha, and M. Das, "High Payload Image Steganography Using DNN Classification and Adaptive Difference Expansion. Wireless Personal Communications 2024, 134, 1349–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A. K. Jahbel, T. A. K. Jahbel, T. Ahmad, and N. J. De La Croix, "Reduced Difference Expansion based on Cover Image Bisection for a Quality Stego Image," in 2024 Conference on Information Communications Technology and Society (ICTAS), 2024, pp. 51-56.

- A. Arham and H. A. Nugroho, "Enhanced reversible data hiding using difference expansion and modulus function with selective bit blocks in images. Cybersecurity 2024, 7, 61. [CrossRef]

- R. Tan and H. Fu, "Constrained Range Compression-Difference Histogram Shifting Reversible Information Hiding," in Proceedings of the 2024 3rd International Conference on Cryptography, Network Security and Communication Technology, 2024, pp. 617-623.

- C. Y. Weng, H. Y. C. Y. Weng, H. Y. Weng, N. S. Shongwe, and C. T. Huang, "High-Payload Data-Hiding Scheme Based on Interpolation and Histogram Shifting. Electronics 2024, 13, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Liang and S. Xiang, "General Distortion Metric Based Histogram Shifting for Reversible Data Hiding. IEEE Signal Processing Letters 2024.

- T. Xiong, H. T. Xiong, H. Ding, and Y. Li, "A blind extraction reversible data hiding based on histogram shifting," in Fourth International Conference on Optics and Image Processing (ICOIP 2024), 2024, vol. 13254, pp. 472-477.

- S. Meikap and B. Jana, "Reference pixel-based reversible data hiding scheme using multi-level pixel value ordering. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 16895–16928.

- A. Broumandnia, "Two-dimensional modified pixel value differencing (2 D-MPVD) image steganography with error control and security using stream encryption. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 21967–22003.

- D. C. Wu and Z. N. Shih, "Image Steganography by Pixel-Value Differencing Using General Quantization Ranges," CMES-Computer Modeling in Engineering & Sciences, vol. 141, no. 1, 2024.

- Jan, S. A. Parah, M. Hussan, and B. A. Malik, "LSB Technique-Based Dual-Image Steganography Using COS Function," in Proceedings of Emerging Trends and Technologies on Intelligent Systems. 2021; pp. 243–249.

- K. Upendra Raju and N. Amutha Prabha, "Dual images in reversible data hiding with adaptive color space variation using wavelet transforms. International Journal of Intelligent Unmanned Systems 2023, 11, 96–108. [CrossRef]

- T. C. Lu, T. N. T. C. Lu, T. N. Vo, and B. Jana, "Dual-image reversible data hiding based on encoding the numeral system of concealed information," in 2023 15th International Conference on Advanced Computational Intelligence (ICACI), 2023, pp. 1-7.

- H. Ye, K. H. Ye, K. Su, X. Cheng, and S. Huang, "Research on reversible image steganography of encrypted image based on image interpolation and difference histogram shift. IET Image Processing 2022, 16, 1959–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Zhao, F. S. Zhao, F. Yan, K. Chen, and H. Yang, "Interpolation-based high capacity quantum image steganography. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 2021, 60, 3722–3743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X. Bai, Y. X. Bai, Y. Chen, G. Duan, C. Feng, and W. Zhang, "A data hiding scheme based on the difference of image interpolation algorithms. Journal of Information Security and Applications 2022, 65, 103068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. W. Edgar and D. O. Manz, Research Methods for Cyber Security. Syngress, 2017.

- A. Kerckhoffs, "La cryptographie militaire, ou, Des chiffres usit´es en temps de guerre: avec un nouveau proc´ed´e de d´echiffrement applicable aux systemes a double clef," Librairie militaire de L. Baudoin, 1883.

- D. Kleiman, "The official CHFI study guide (exam 312-49): for computer hacking forensic investigator," Elsevier, 2011.

- Boehm, "Stegexpose—A tool for detecting LSB steganography," arXiv preprint, 2014. arXiv:1410.6656.

- A. I. Tabirca, C. A. I. Tabirca, C. Dumitrescu, and V. Radu, `Enhancing Banking Transaction Security with Fractal-Based Image Steganography Using Fibonacci Sequences and Discrete Wavelet Transform. Fractal and Fractional 2025, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas and P. Blanco-Medina, "State of the Art: Image Hashing," arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.11794, Aug. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2108.11794.

- O. Omego and M. Bosy, `Multichannel Steganography: A Provably Secure Hybrid Steganographic Model for Secure Communication”, arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.04511, 2025.

- Wang, Y. , Li Z., & Huang T. (2023). A Comprehensive Study on the Security of SHA-256. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security, 18, 2754-2763.

- Kumar, S. Singh R. Evaluation of Hash Functions for Secure Data Storage. IEEE Transactions on Information Systems 2024, 29, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, S.; Li, Q. A Comparative Study of Hash Functions for Cybersecurity. Journal of Cryptographic Engineering 2023, 11(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. , & Liu X. A Novel Hybrid Encryption Scheme using SHA-256 and Elliptic Curve Cryptography. IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems 2024, 35, 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Dr-StegWizard, "Cover Images Dataset," GitHub repository, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/Dr-StegWizard/CoverImages. [Accessed: Feb. 22, 2025].

- A. Malik, G. A. Malik, G. Sikka, and H. K. J. M. Verma, "A reversible data hiding scheme for interpolated images based on pixel intensity range. Numerical Mathematics: Theory, Methods and Applications 2020, 18005–18031. [Google Scholar]

- F. S. Hassan and A. Gutub, "Efficient reversible data hiding multimedia technique based on smart image interpolation. Numerical Mathematics: Theory, Methods and Applications 2020, 79, 30087–30109.

- X. Xiong, Y. X. Xiong, Y. Chen, M. Fan, and S. Zhong, "Adaptive reversible data hiding algorithm for interpolated images using sorting and coding. Journal of Imaging Science and Applications 2022, 66, 103137. [Google Scholar]

- X. Bai, Y. X. Bai, Y. Chen, G. Duan, C. Feng, and W. Zhang, "A data hiding scheme based on the difference of image interpolation algorithms. Journal of Imaging Science and Applications 2022, 65, 103068. [Google Scholar]

- S. R. Brahma, S. S. R. Brahma, S. Singh, D. K. Gupta, and A. Malik, "A reversible data hiding technique using lower magnitude error channel pair selection. Numerical Mathematics: Theory, Methods and Applications 2023, 82, 8467–8488. [Google Scholar]

- M. Fan, S. M. Fan, S. Zhong, and X. Xiong, "Reversible data hiding method for interpolated images based on modulo operation and prediction-error expansion. Numerical Mathematics: Theory, Methods and Applications 2023, 11, 27290–27302. [Google Scholar]

- Z. Huang, Y. Z. Huang, Y. Lin, and X. Chen, "A block-based adaptive high fidelity reversible data hiding scheme in interpolation domain. Numerical Mathematics: Theory, Methods and Applications 2023, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- A. Tripathi and J. Prakash, "Blockchain enabled interpolation based reversible data hiding mechanism for protecting records. IEEE Transactions on Systems, Information and Security 2023, 1.

- C.-Y. Weng, H.-Y. C.-Y. Weng, H.-Y. Weng, N. S. Shongwe, and C.-T. Huang, "High-payload data hiding scheme based on interpolation and histogram. Electronics 2024, 13, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Residual artifacts exposing payload distribution in spatial domain

Figure 1.

Residual artifacts exposing payload distribution in spatial domain

Figure 2.

Benchmarking contemporary RDH techniques: payload capacity vs. distortion trade-offs

Figure 2.

Benchmarking contemporary RDH techniques: payload capacity vs. distortion trade-offs

Figure 3.

Security-evolution framework for reversible LSB steganography

Figure 3.

Security-evolution framework for reversible LSB steganography

Figure 4.

Standardized grayscale test images from OPTED dataset (n=12) for steganographic benchmarking

Figure 4.

Standardized grayscale test images from OPTED dataset (n=12) for steganographic benchmarking

Figure 5.

Workflow for lossless payload insertion in cover media

Figure 5.

Workflow for lossless payload insertion in cover media

Figure 6.

Reversible payload extraction workflow with integrity verification

Figure 6.

Reversible payload extraction workflow with integrity verification

Figure 7.

Inverse modulo-5 mapping for reversible payload encoding

Figure 7.

Inverse modulo-5 mapping for reversible payload encoding

Figure 8.

Dual-channel embedding architecture with parity synchronization

Figure 8.

Dual-channel embedding architecture with parity synchronization

Figure 9.

Dual-channel payload recovery with modulo-5 reconstruction

Figure 9.

Dual-channel payload recovery with modulo-5 reconstruction

Figure 10.

Dual-channel LSB embedding with XOR-key diffusion

Figure 10.

Dual-channel LSB embedding with XOR-key diffusion

Figure 11.

Dual-channel payload recovery

Figure 11.

Dual-channel payload recovery

Figure 12.

Diagrammatic illustration of message embedding

Figure 12.

Diagrammatic illustration of message embedding

Figure 13.

Illustrating message extraction logic

Figure 13.

Illustrating message extraction logic

Figure 14.

Reconstructing the original image

Figure 14.

Reconstructing the original image

Figure 15.

Residual noise patterns exposing steganographic modifications

Figure 15.

Residual noise patterns exposing steganographic modifications

Figure 16.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of the adversarial classifier. An AUC of 0.50 reflects total nondiscrimination between cover and stego samples.

Figure 16.

Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve of the adversarial classifier. An AUC of 0.50 reflects total nondiscrimination between cover and stego samples.

Figure 17.

Confusion matrix showing that all stego instances were misclassified as cover.

Figure 17.