Submitted:

21 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

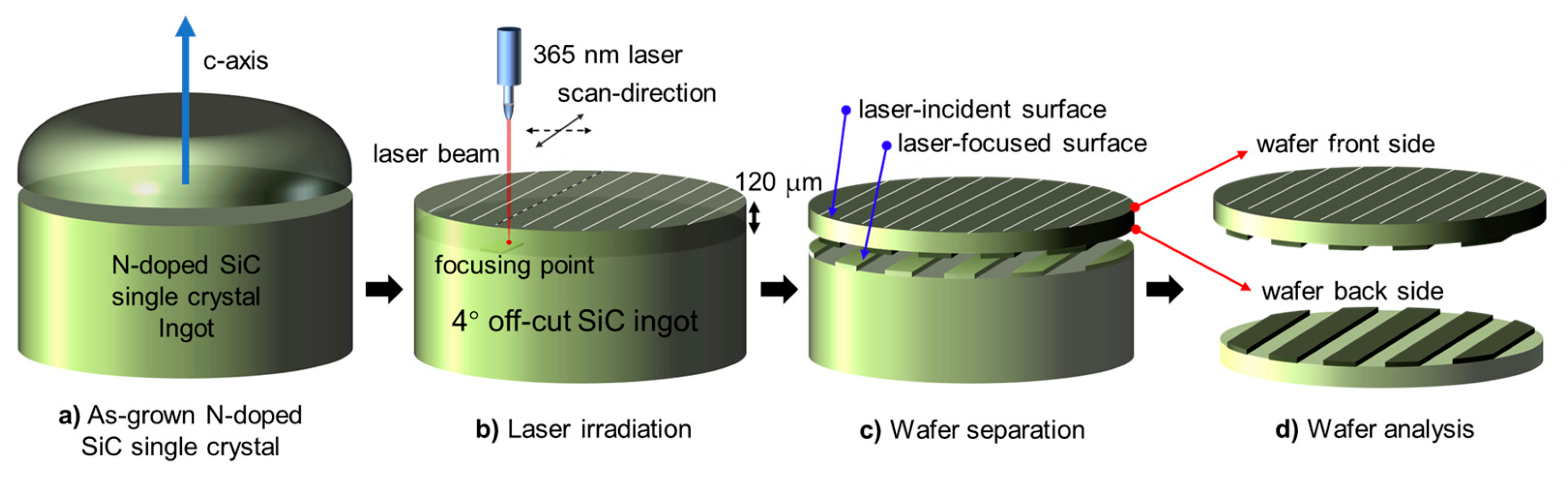

2. Experimental Method

2.1. The Laser System

2.2. Materials and Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

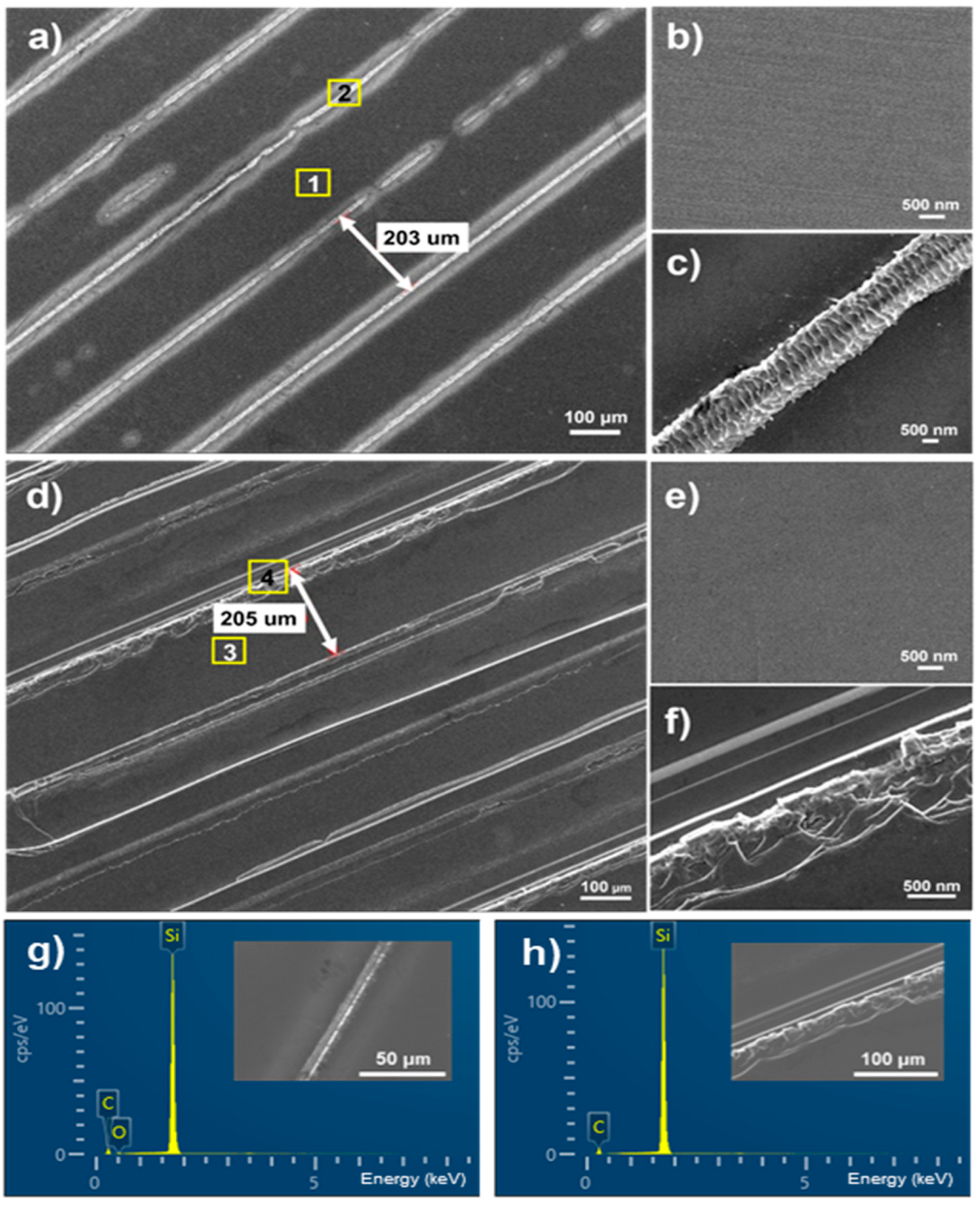

3.1. Surface Morphology

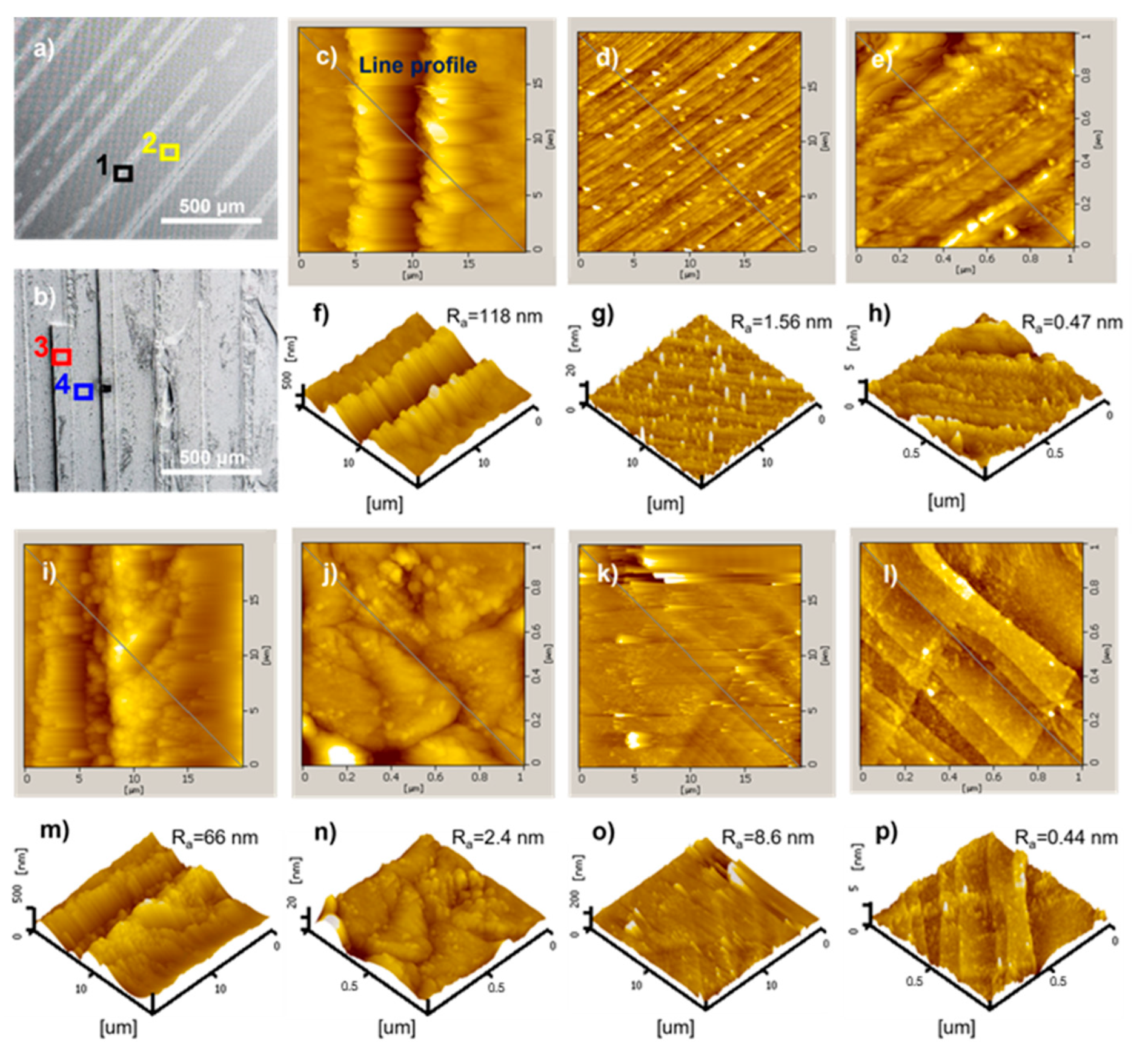

3.2. Surface Roughness

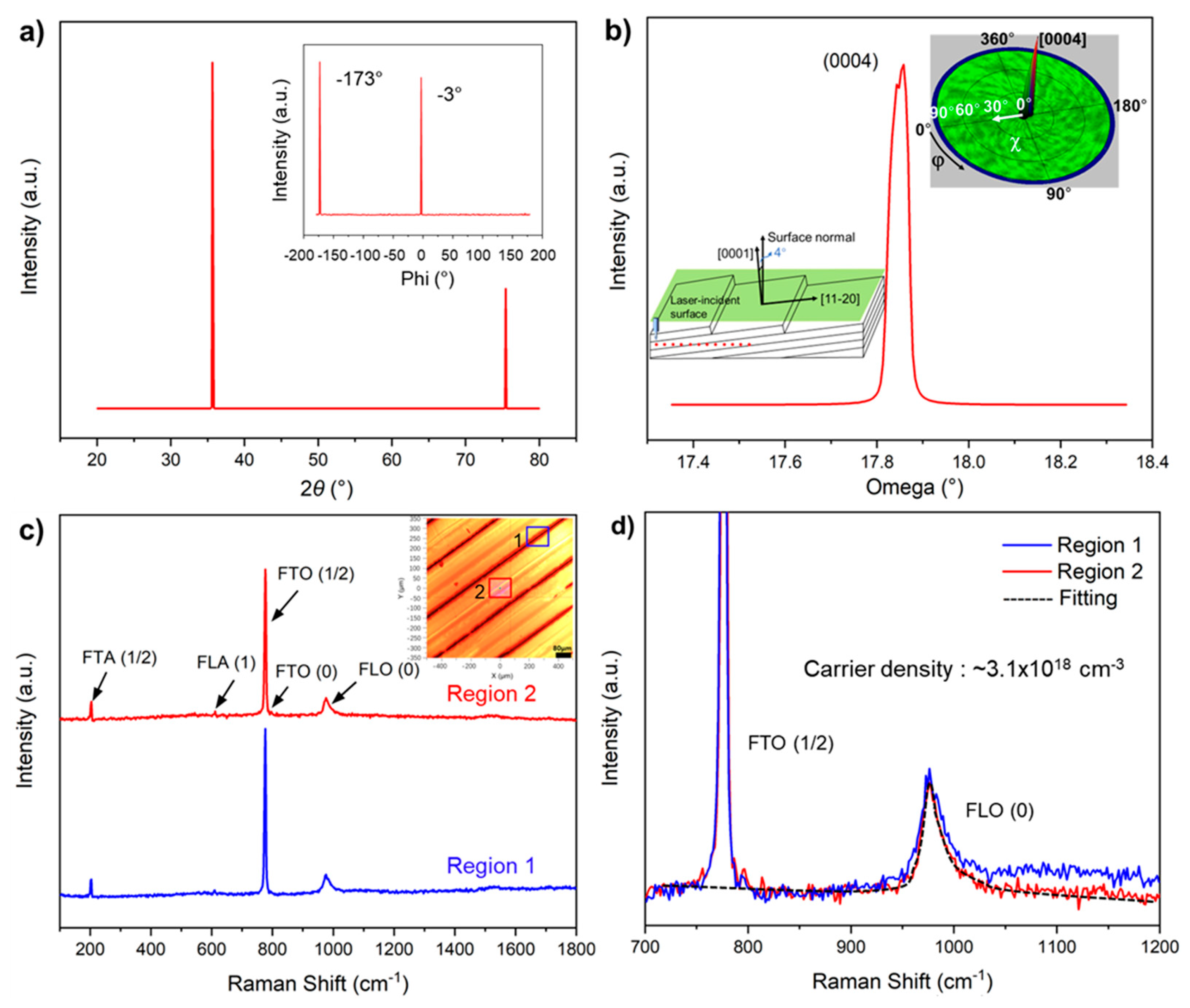

3.3. Structural Phase Transformation

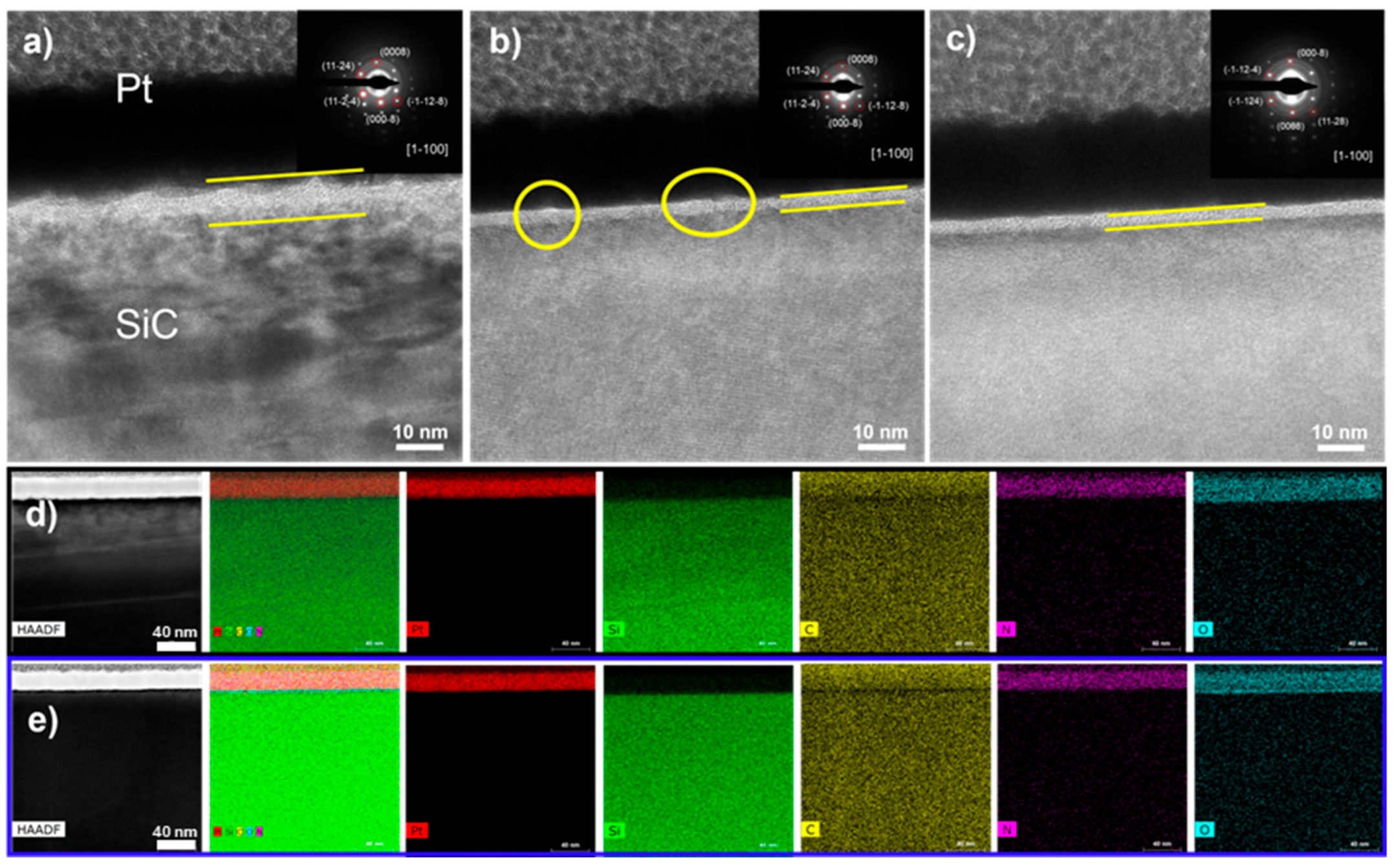

3.4. Nanoscale Morphology and Phase Architecture

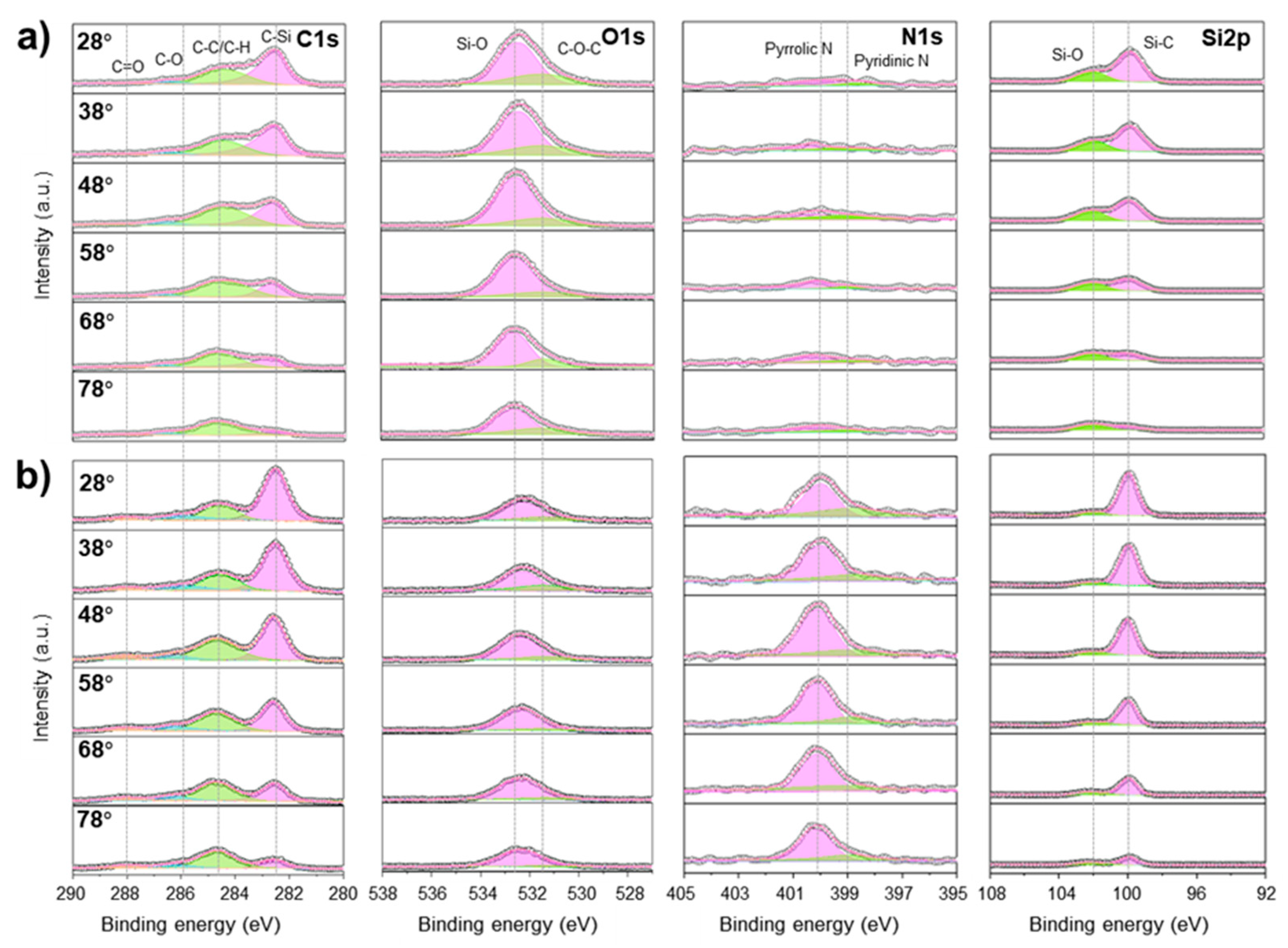

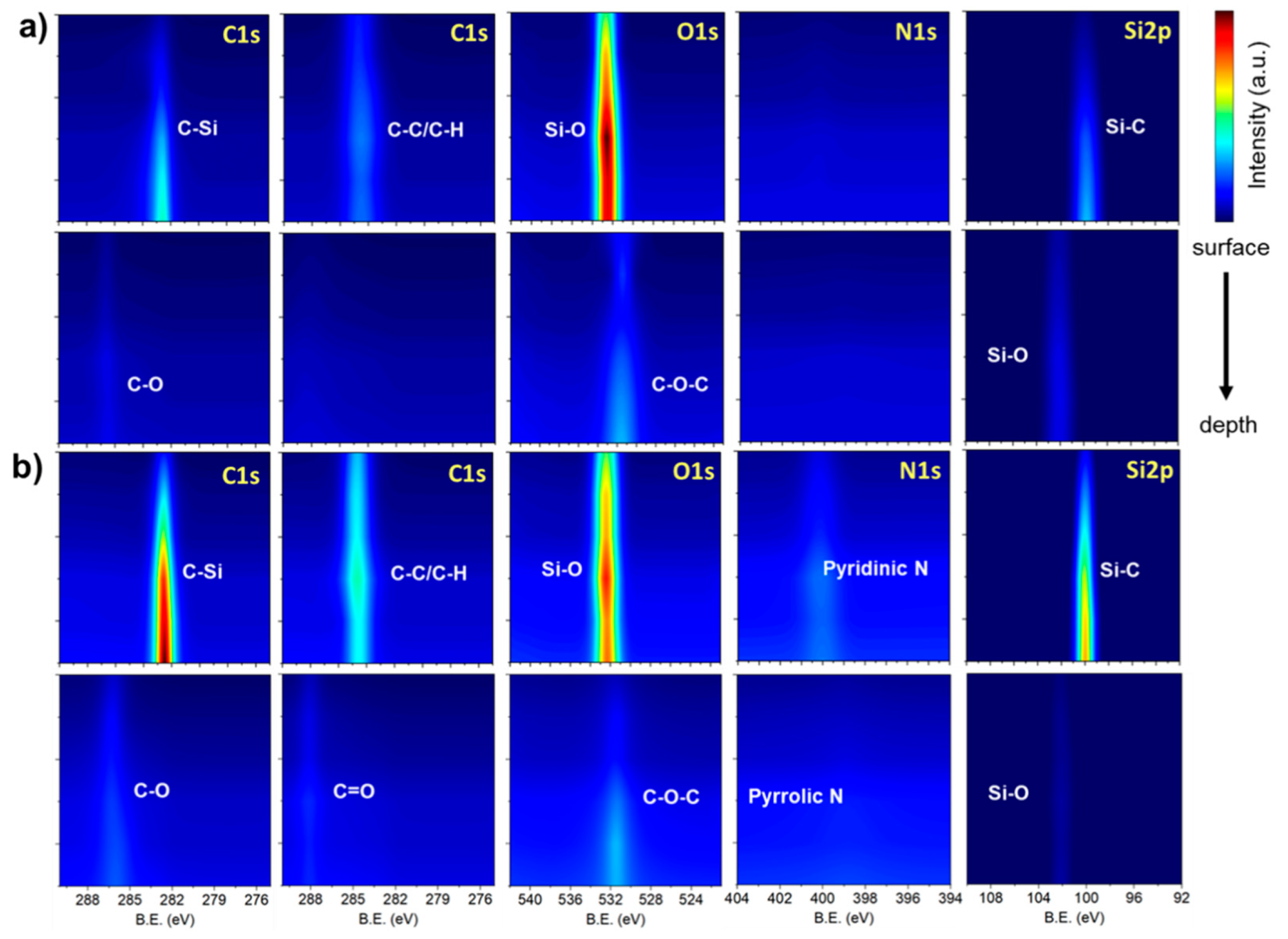

3.5. Surface Chemistry and Bonding Characteristic

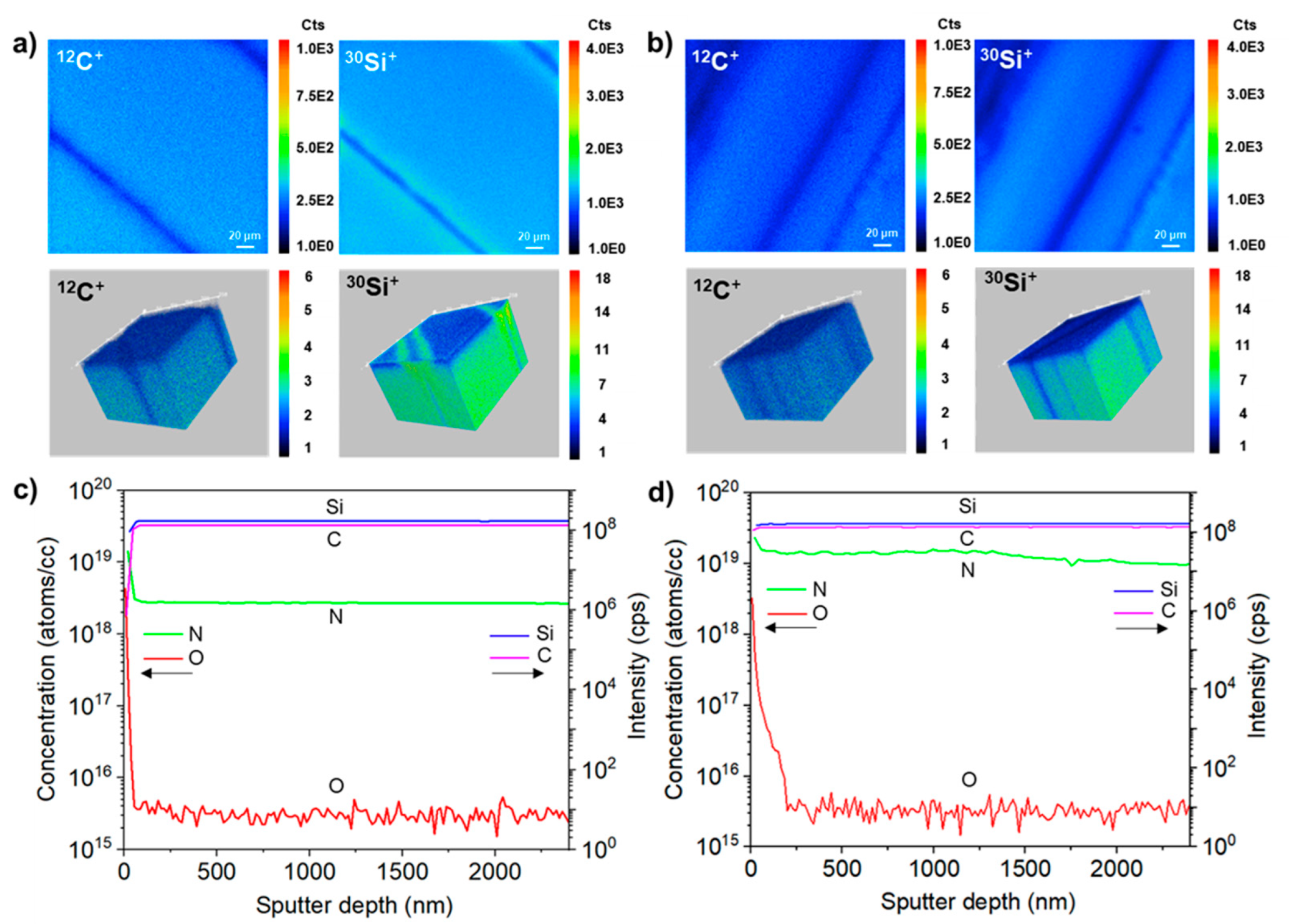

3.6. Elemental Distribution and Interface Evolution

3.7. Surface Features of UV Laser-Sliced SiC Wafers

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SiC | Silicon Carbide |

| XPS | X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| SIMS | Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry |

| FIB | Focused Ion Beam |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| SAED | Selected Area Electron Diffraction |

| AFM | Atomic Force Microscopy |

| ARXPS | Angle-Resolved X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy |

| FTO | Folded Transverse Optical |

| LOPC | Longitudinal Optical-Phonon Coupled |

| FWHM | Full Width at Half Maximum |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| CMP | Chemical Mechanical Planarization |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

References

- Ohno, T.; Haider, M.; Mirić, S. Performance review of state-of-the-art 1.2 kV SiC devices based on experimental figures-of-merit. e+i Elektrotechnik und Informationstechnik 2025, 142, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninh, D.G.; Hoang, M.T.; Wang, T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, T.K.; Streed, E.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Nguyen, N.T.; Dau, V.; Dao, D.V. Giant photoelectric energy conversion via a 3C-SiC Nano-Thin film double heterojunction. Chemical Engineering Jounal 2024, 496. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Nie, M.; Dong, Q.; Liu, H.; Jia, P.; Li, Z.; Fang, Y. Applicability Analysis of High-Voltage Transmission and Substation Equipment Based on Silicon Carbide Devices. Micromachines 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, A.Q. Extreme high efficiency enabled by silicon carbide (SiC) power devices. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2024, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Zhang, R.; Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Jia, Z.; Wang, J. An investigation of recast behavior in laser ablation of 4H-silicon carbide wafer. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2020, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wang, H.; Peng, S.; Cao, Q. Precision Layered Stealth Dicing of SiC Wafers by Ultrafast Lasers. Micromachines (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Huang, C.; Wang, J.; Jia, Z. Surface quality evaluation of single crystal 4H-SiC wafer machined by hybrid laser-waterjet: Comparing with laser machining. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2019, 93, 238–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, S.-F.; Luo, C.-X.; Hsiao, W.-T. Characterization analysis of 355 nm pulsed laser cutting of 6H-SiC. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2023, 130, 3133–3147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Fu, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, K.; Cao, L.; Hu, C. Material Removal Mechanisms of Polycrystalline Silicon Carbide Ceramic Cut by a Diamond Wire Saw. Materials (Basel) 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Gao, Y.; Huang, W. Prediction of excess kerf loss in diamond wire sawing based on vibration source signal measurement and processing. Measurement 2026, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefene, E.M.; Chen, C.-C.A.; Tsai, Y.-H. A comprehensive review of diamond wire sawing process for single-crystal hard and brittle materials. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2024, 131, 1466–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Gao, Y.; Yang, C. Research progress on subsurface microcrack damage of silicon wafer cut by diamond wire saw: a review. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics 2025, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Yu, H.; He, C.; Zhao, S.; Ning, C.; Jiang, L.; Lin, X. Laser slicing of 4H-SiC wafers based on picosecond laser-induced micro-explosion via multiphoton processes. Optics & Laser Technology 2022, 154. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Chen, Q.; Yao, Y.; Che, L.; Zhang, B.; Nie, H.; Wang, R. Influence of Surface Preprocessing on 4H-SiC Wafer Slicing by Using Ultrafast Laser. Crystals 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Lu, X.; Li, L.; Yan, Y.; Guo, W. Micro-nanoscale laser subsurface vertical modification of 4H-SiC semiconductor materials: mechanisms, processes, and challenges. Discov Nano 2025, 20, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, R.; Chen, Q.; Duan, R. A Review of Femtosecond Laser Processing of Silicon Carbide. Micromachines (Basel) 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, F.; Xu, J.; Yan, S.; Zhang, Y. Mechanism and regulation of thermal damage on picosecond laser modification dicing of SiC wafer. Chemical Engineering Journal 2024, 493. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, W.; Shao, Q.; Pei, Y.; Wang, R. Slicing of 4H-SiC Wafers Combining Ultrafast Laser Irradiation and Bandgap-Selective Photo-Electrochemical Exfoliation. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, S.F.; Farshidianfar, A.; Dalir, H. An applicable review on recent laser beam cutting process characteristics modeling: geometrical, metallurgical, mechanical, and defect. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2023, 130, 2159–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, L.; Feng, G.; Xi, K.; Algadi, H.; Dong, M. Laser technologies in manufacturing functional materials and applications of machine learning-assisted design and fabrication. Advanced Composites and Hybrid Materials 2024, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Lu, X.; Jiang, L.; Han, S.; Li, X.; Yu, H.; Zhao, S.; Lin, X. Suppressing kerf loss based on multi-focal approach for 4H-SiC laser slicing. Opt Express 2025, 33, 34267–34280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, S.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Gao, P. Numerical Simulation and Experimental Study on Picosecond Laser Polishing of 4H-SiC Wafer. Micromachines (Basel) 2025, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Chen, T.; Ma, G.; Zhang, W.; Huang, L. Influence of Pulse Energy and Defocus Amount on the Mechanism and Surface Characteristics of Femtosecond Laser Polishing of SiC Ceramics. Micromachines (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, X.; Huang, Y.; Hu, W.; Long, J. Internal modified structure of silicon carbide prepared by ultrafast laser for wafer slicing. Ceramics International 2023, 49, 5249–5260. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Zhao, S.; Du, J.; Jiang, L.; Han, S.; Yu, H.; Li, X.; Lin, X. Laser double-layer slicing of SiC wafers by using axial dual-focus. Opt Express 2025, 33, 9775–9789. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, W.; Qi, X.; Wang, A.; Grojo, D.; Li, X. High-precision laser slicing of silicon carbide using temporally shaped ultrafast pulses. Light: Advanced Manufacturing 2025, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Xiangfu, L.; Minghui, H. Micro-cracks generation and growth manipulation by all-laser processing for low kerf-loss and high surface quality SiC slicing. Opt Express 2024, 32, 38758–38767. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Gao, T. Ab initio study of the lattice stability of β-SiC under intense laser irradiation. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2015, 645, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, W.H.; Boning, D.; Welsch, R. Multi-strata subsurface laser die singulation to enable defect-free ultra-thin stacked memory dies. AIP Advances 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Feng, L.; Zheng, H.; Cheng, G.J. Ultrafast pulsed laser stealth dicing of 4H-SiC wafer: Structure,evolution and defect generation. Journal of Manufacturing Processes 2022, 81, 562–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Wen, Z.; Shi, H.; Zhang, K.; Li, M.; Zhang, Z.; Hou, Y.; Song, Z. Investigation on the Processing Quality of Nanosecond Laser Stealth Dicing for 4H-SiC Wafer. ECS Journal of Solid State Science and Technology 2023, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.; Xiong, H.; Lv, K.; He, Z.; Zeng, H.; Huan, Y. Low-damage precision slicing of SiC by simultaneous dual-beam laser-driven crack expansion of silicon carbide. Optics & Laser Technology 2025, 192. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Liu, J.; Tang, J.; Li, J.; Ma, Z.M.; Cao, H.; Zhao, R.; Zhiwei, K.; Huang, K.; Gao, J.; Hou, T. UV nanosecond laser machining and characterization for SiC MEMS sensor application. Sensors and Actuators A: Physical 2018, 276, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouhani, M.; Metla, S.B.S.; Hobley, J.; Karnam, D.; Hung, C.H.; Lo, Y.L.; Jeng, Y.R. A complete phase distribution map of the laser affected zone and ablation debris formed by nanosecond laser-cutting of SiC. Journal of Materials Processing Technology 2025, 338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Xu, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, X.; Hartmaier, A.; Liu, B.; Le, S.; Luo, X. In situ investigation of nanometric cutting of 3C-SiC using scanning electron microscope. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology 2021, 115, 2299–2312. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Song, Q.; Shi, H.; Hou, Y.; Yue, S.; Wang, R.; Cai, S.; Zhang, Z. Surface micromorphology and nanostructures evolution in hybrid laser processes of slicing and polishing single crystal 4H-SiC. Journal of Materials Science & Technology 2024, 184, 235–244. [Google Scholar]

- Tóth, S.; Péter, N.; Péter, R.; László, H.; Péter, D.; Margit, K. Silicon carbide nanocrystals produced by femtosecond laser pulses. Diamond and Related Materials 2018, 81, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fu, Y.; Yu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, J.; Xu, J. Subsurface deformation and crack propagation between 3C-SiC/6H-SiC interface by applying in-situ laser-assisted diamond cutting RB-SiC. Materials Letters 2023, 336. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C.; Yang, Y.; Huang, Z.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, F.; Wei, Y.; Jiao, Z. Investigation on the laser ablation of SiC ceramics using micro-Raman mapping technique. Journal of Advanced Ceramics 2016, 5, 253–261. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.; Sun, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Pang, Y.; Sun, W.; Monka, P.P. Research on the ablation mechanism and feasibility of UV laser drilling to improve the machining quality of 2.5D SiC/SiC composites. Optics & Laser Technology 2025, 181. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Zhao, S.; Han, S.; Liang, H.; Du, J.; Yu, H.; Lin, X. CW laser-assisted splitting of SiC wafer based on modified layer by picosecond laser. Optics & Laser Technology 2024, 174. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Kurokawa, S.; Doi, T.; Yuan, J.; Fan, L.; Mitsuhara, M.; Lu, H.; Yao, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K. SEM, AFM and TEM Studies for Repeated Irradiation Effect of Femtosecond Laser on 4H-SiC Surface Morphology at Near Threshold Fluence. ECS Journal of Solid State Science and Technology 2018, 7, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Tang, F.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X. Accelerated ICP etching of 6H-SiC by femtosecond laser modification. Applied Surface Science 2019, 488, 853–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Ha, J.; Jeong, J.; Park, J.; Park, J.; Kang, S.; Kim, D. X-ray Diffraction Analysis of Damaged Layer During Polishing of Silicon Carbide. International Journal of Precision Engineering and Manufacturing 2022, 24, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C.H.; Chang, C.Y.; Hsiao, Y.K.; Chen, C.C.A.; Tu, C.C.; Kuo, H.C. Recent Advances In Silicon Carbide Chemical Mechanical Polishing Technologies. Micromachines (Basel) 2022, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, H.Y.; Lin, Y.H.; Huang, K.C.; Lee, C.J.; Yeh, J.A.; Yang, Y.; Ding, C.-F. Precision material removal and hardness reduction in silicon carbide using ultraviolet nanosecond pulse laser. Applied Physics A 2025, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Chen, Q.; Yao, Y.; Che, L.; Fan, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Wang, R. A review of laser-assisted SiC wafer manufacture: green and sustainable slicing and planarization for integrated applications. Materials Today Communications 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Wei, M.; Li, X.; Yuan, J.; Hang, W.; Han, Y. Atmospheric Plasma Etching-Assisted Chemical Mechanical Polishing for 4H-SiC: Parameter Optimization and Surface Mechanism Analysis. Processes 2025, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ji, P.; Shi, C.; Hao, D.; Zhang, Y.; Moro, R.; Ma, Y.; Ma, L. Hydrogen etching of 4H–SiC(0001) facet and step formation. Materials Science in Semiconductor Processing 2022, 149. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, M.A.; Graves, A.R.; Boris, D.R.; Walton, S.G.; Stinespring, C.D. Plasma assisted remediation of SiC surfaces. Journal of Applied Physics 2024, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z.; He, Y.; Sun, X.; Wen, Q. UV-TiO2 photocatalysis-assisted chemical mechanical polishing 4H-SiC wafer. Materials and Manufacturing Processes 2017, 33, 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Wang, W.; Liu, W.; Song, Z. Polishing Mechanism of CMP 4H-SiC Crystal Substrate (0001) Si Surface Based on an Alumina (Al(2)O(3)) Abrasive. Materials (Basel) 2024, 17. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, L.; Wu, J.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Chuai, S.; Wang, Z. Optimization of polishing fluid composition for single crystal silicon carbide by ultrasonic assisted chemical-mechanical polishing. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 26056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitta, H.; Isobe, A.; Hong, J.; Hirao, T. Research on Reaction Method of High Removal Rate Chemical Mechanical Polishing Slurry for 4H-SiC Substrate. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics 2011, 50. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Q.; Lu, J.; Tian, Z.; Jiang, F. Controllable material removal behavior of 6H-SiC wafer in nanoscale polishing. Applied Surface Science 2021, 562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Pauw, L. J. A Method of Measuring Specific Resistivity and Hall Effect of Discs of Arbitrary Shape. Philips Research Reports 1958, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, A. Phonon-plasmon coupled modes in GaN. J Phys Condens Matter 2009, 21, 174204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakashima, S.; Harima, H. Raman Investigation of SiC Polytypes. physica status solidi (a) 1997, 162, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).