Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

24 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Construction of Target Performance Index System for AAFC

2.1. Determination of Target Performance Indicators and Parameters

- (1)

- Dry Density and Mechanical Properties

- (2)

- Thermal Performance

- (3)

- Fire Resistance and Water Resistance

- (5)

- Frost Resistance

2.2. Target Performance Indexes of AAFC

3. Mix Proportion Design Method for AAFC

3.1. Basic Principles

3.2. Design Steps and Calculation Methods for Mix Proportion

- (1)

- The mass of each precursor component and other curable materials was determined according to the target dry density of the AAFC.

- (2)

- Determine the water-to-binder ratio, activator dosage, and additional water amount, based on the precursor dosage.

- (3)

- The volume of each constituent material in the slurry was calculated to determine the foam volume.

- (4)

- The foam mass was determined using the calculated foam volume and foam density.

- (5)

- The required foaming agent mass was calculated based on its dilution ratio and foam mass.

3.3. Test Raw Materials and

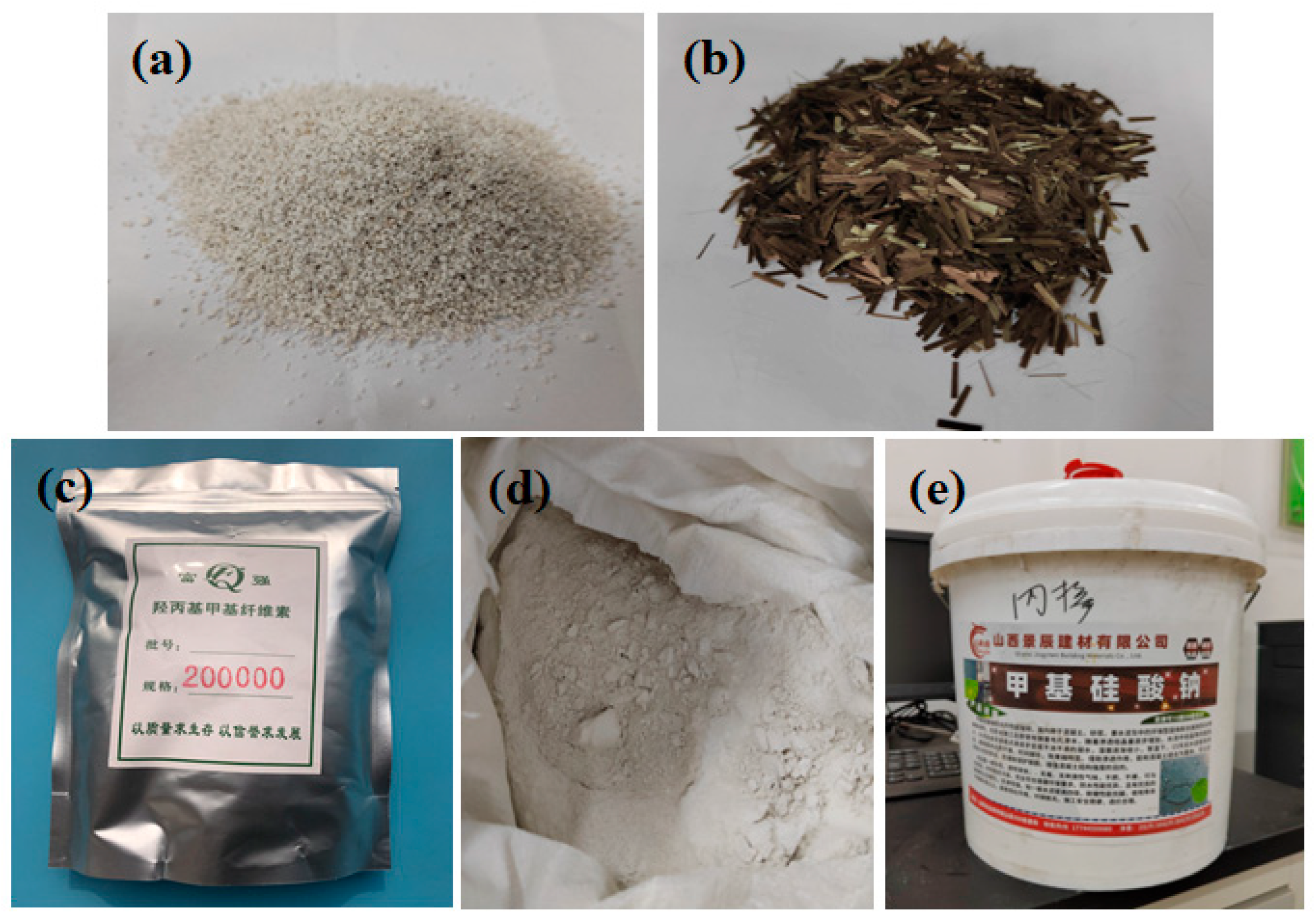

- (1)

- FA and activators

- (2)

- Foaming Agents

- (3)

- Lightweight Aggregate—Vitrified Microspheres

- (4)

- Basalt Fiber

- (5)

- Foam stabilizers.

- (6)

- Calcium Hydroxide

- (7)

- Waterproofing agents.

- (8)

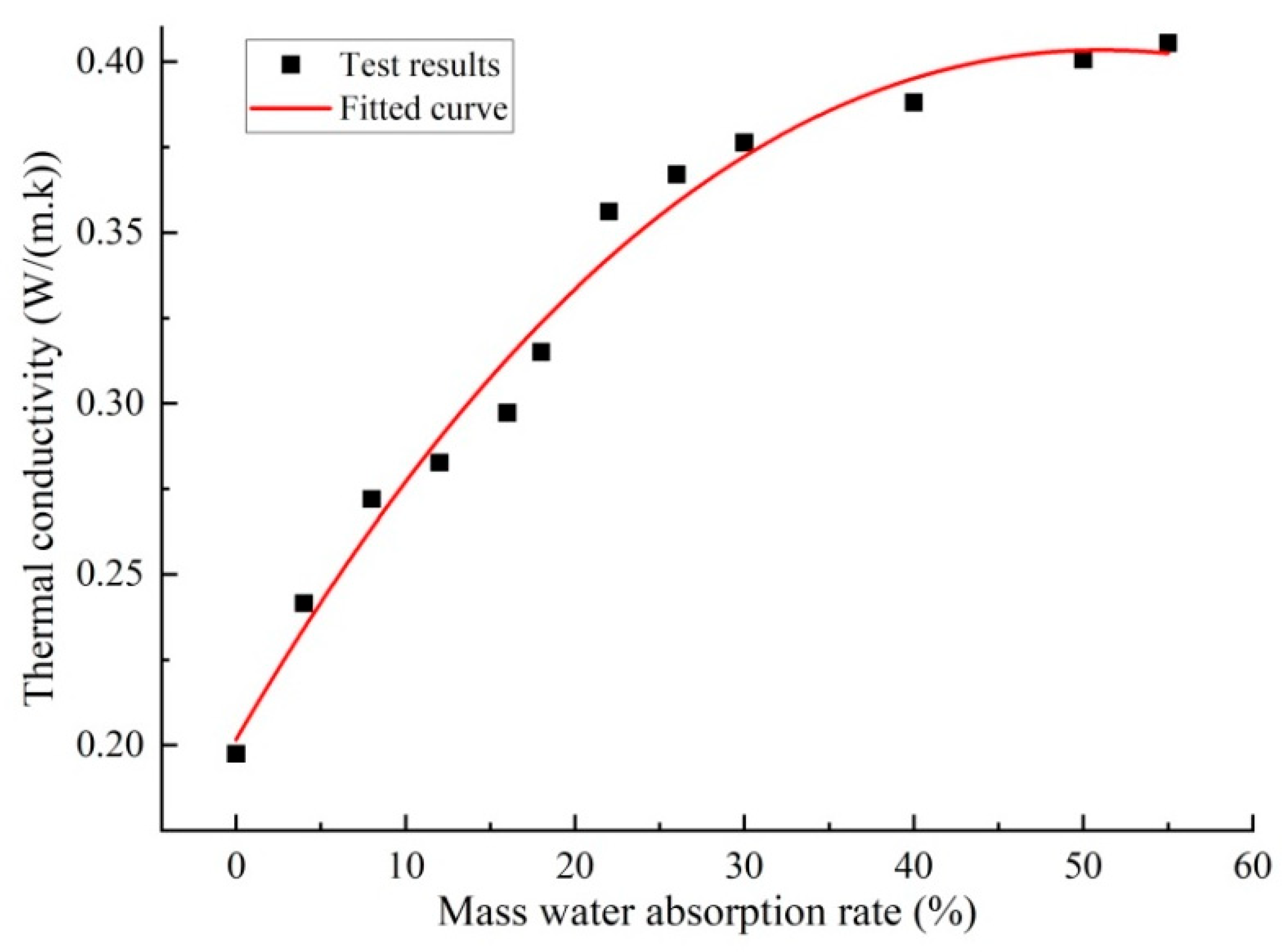

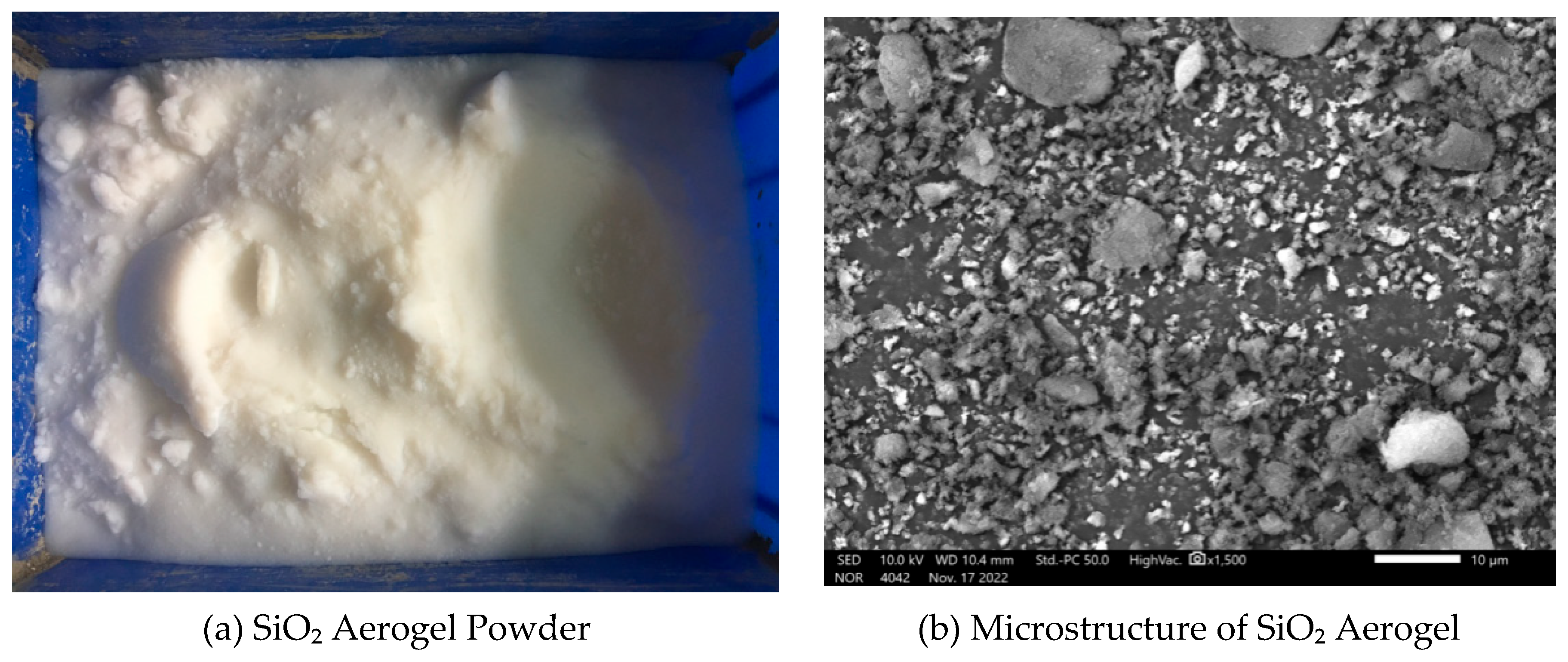

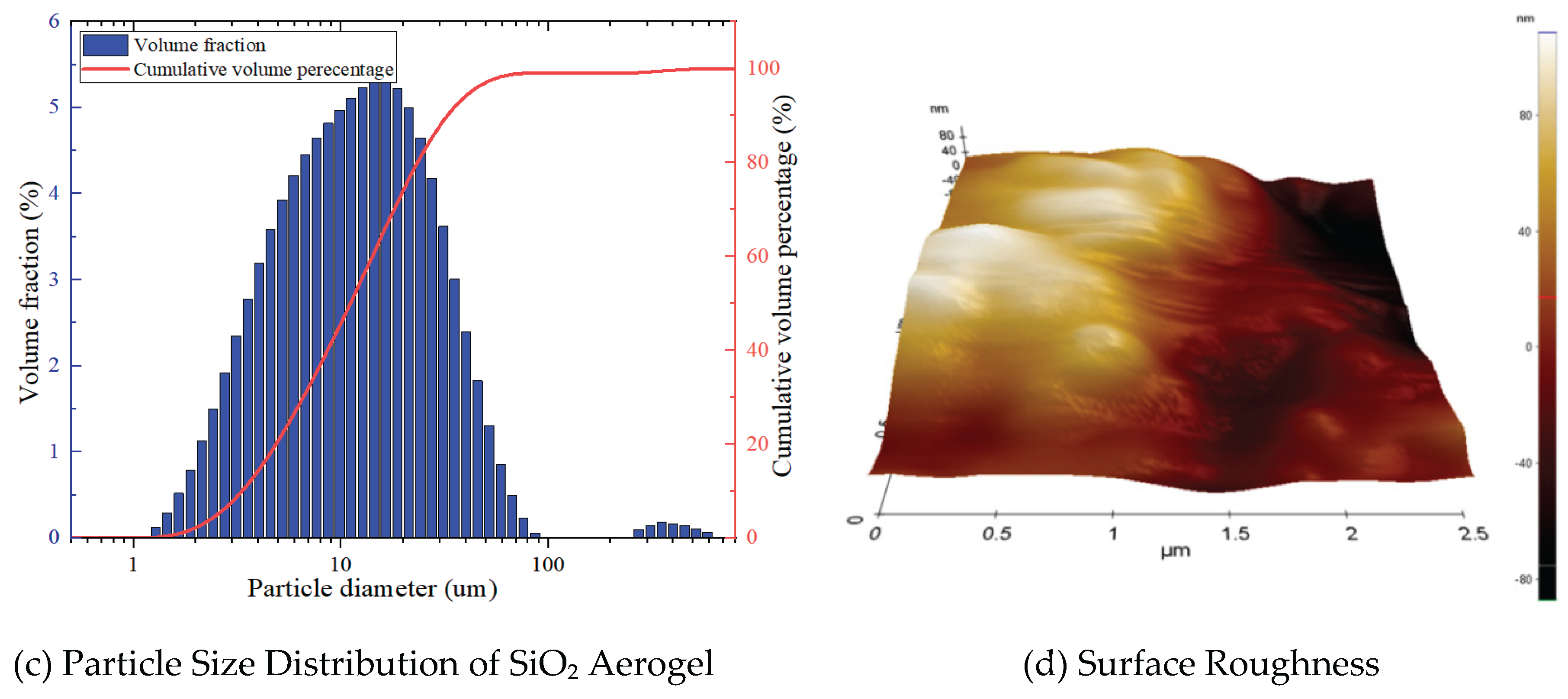

- SiO₂ Aerogel

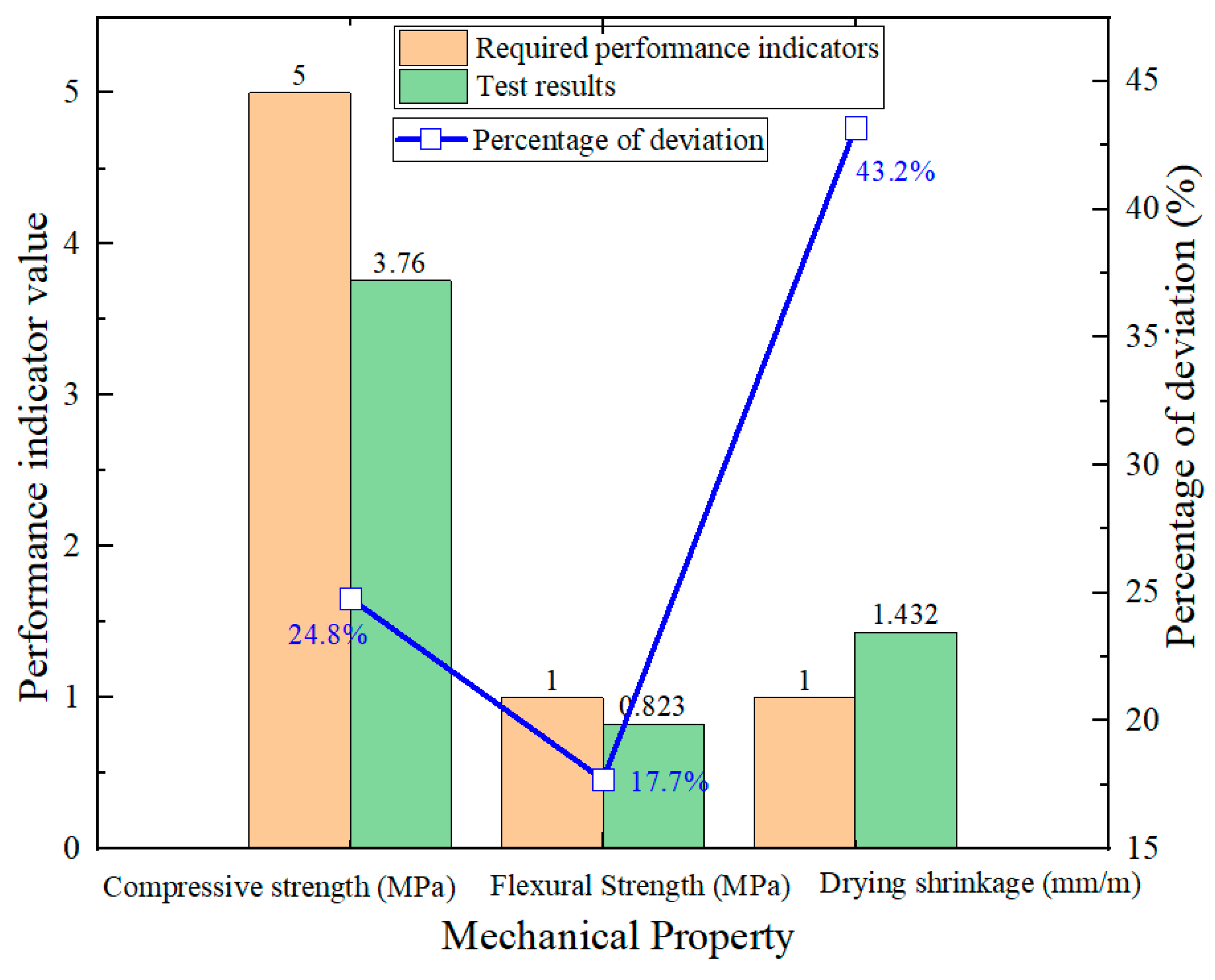

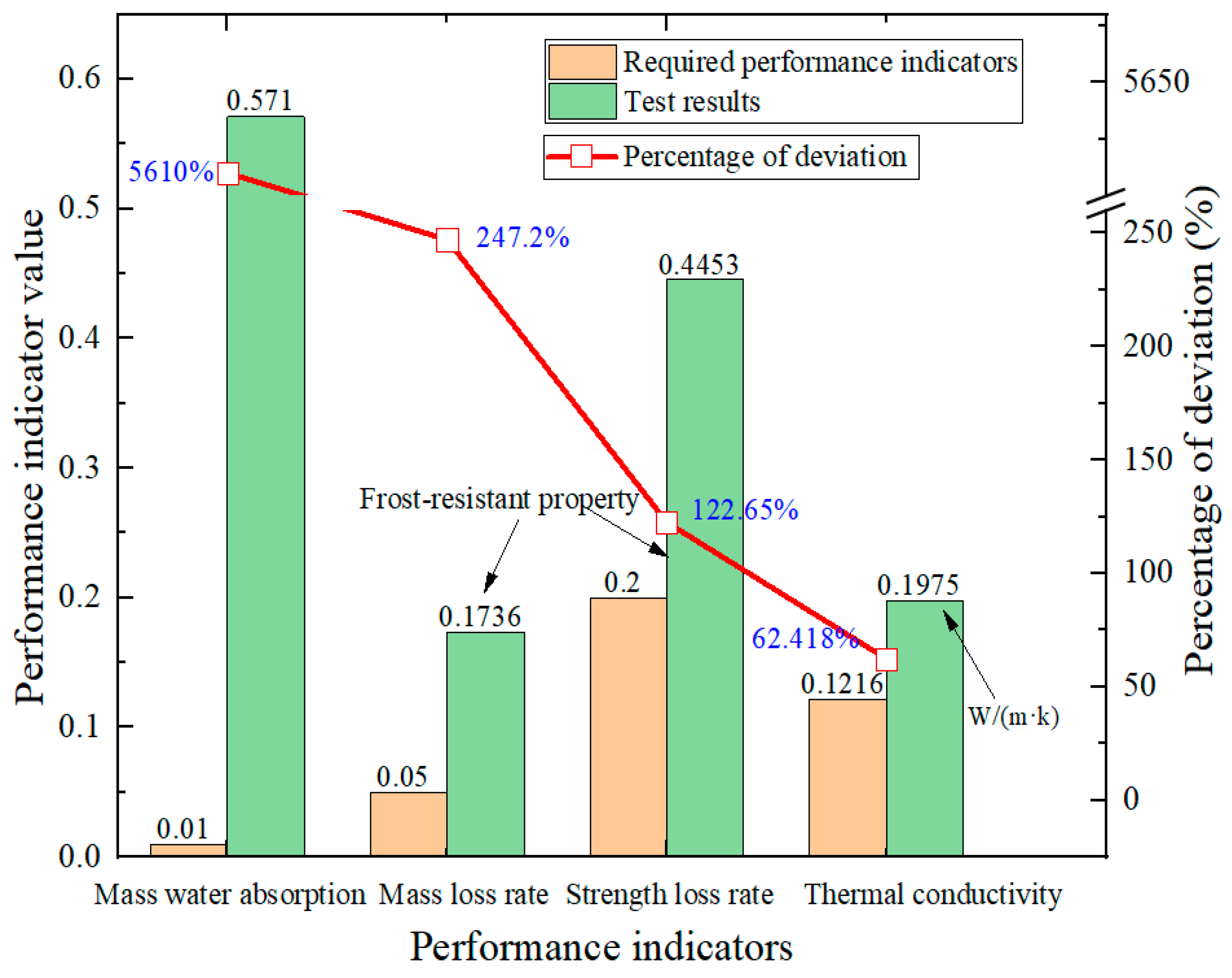

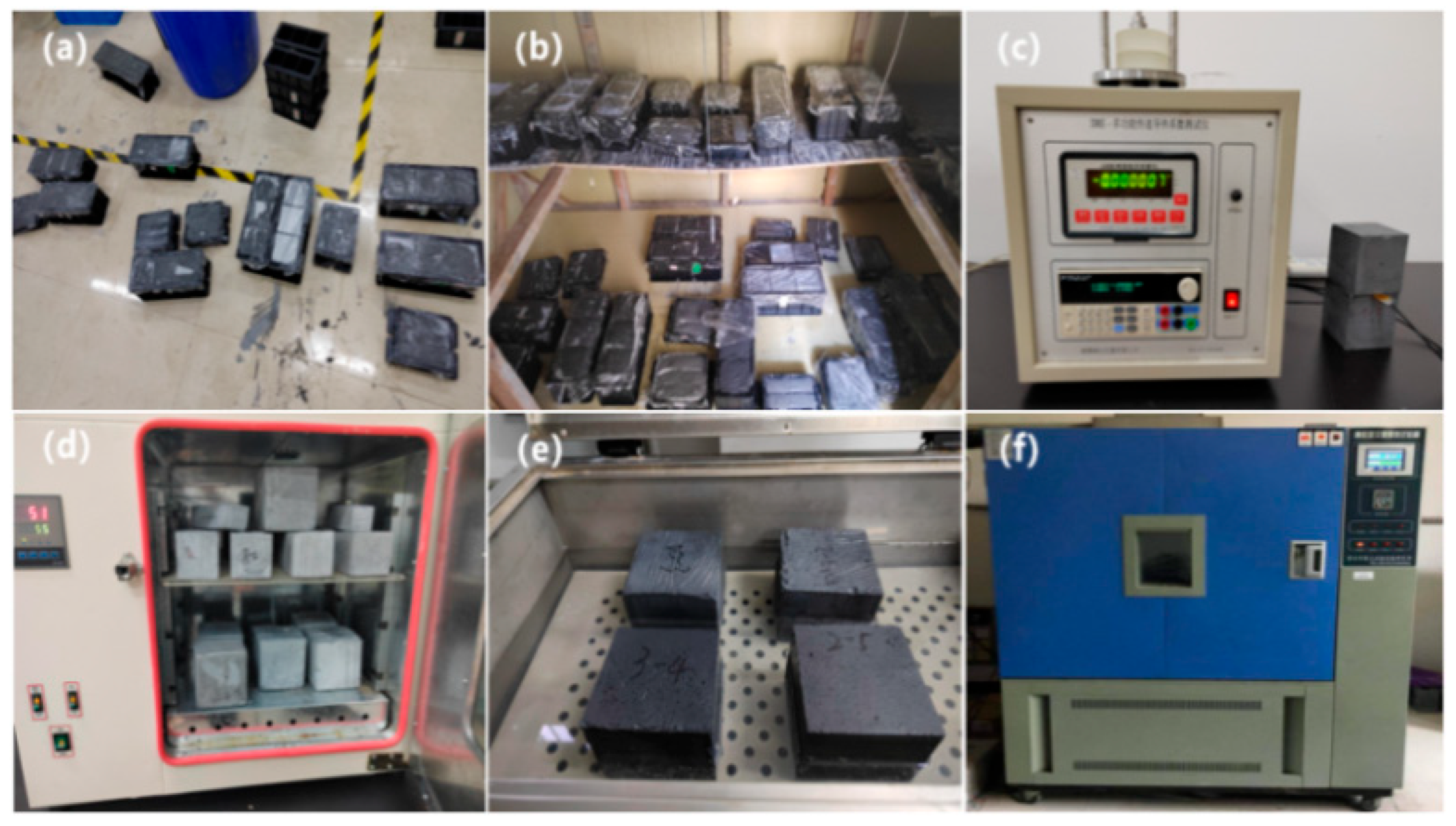

3.4. Experimental Verification of Mix Proportion Design Method and Preliminary Mix Design

3.5. Testing and Results Analysis

4. Performance Optimization of AAFC Based on Orthogonal Experimental Design

4.1. Performance Optimization Methods and Schemes

| Level | Factors | |||||||

| Alkali Equivalent (A) | Activator Modulus (B) | Water-to-Binder Ratio (C) | Foam Dosage (D) | Foam Stabilizer Dosage (E) | Aerogel Dosage (F) | Calcium Hydroxide Dosage (G) | Waterproofing Agent Dosage (H) | |

| 1 | 0.08 | 0.9 | 0.40 | 3.0 | 1% | 2 | 5% | 1.5% |

| 2 | 0.09 | 1.1 | 0.45 | 3.5 | 1.5% | 4 | 10% | 3% |

| 3 | 0.10 | 1.3 | 0.55 | 4.0 | 2.5% | 6 | 15% | 4.5% |

| 4 | 0.11 | 1.5 | 0.60 | 4.5 | 3.5% | 8 | 20% | 5.5% |

4.2. Orthogonal Experimental Design

| NO. | Factors | ||||||||

| Alkali Equivalent (A) | Activator Modulus (B) | Water-to-Binder Ratio (C) | Foam Dosage (D) | Foam Stabilizer Dosage (E) | Aerogel Dosage (F) | Calcium Hydroxide Dosage (G) | Waterproofing Agent Dosage (H) | Empty Column (J) | |

| 1 | 1 (0.08) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.40) | 1 (3.0) | 1 (1%) | 1 (2) | 1 (5%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 (0.45) | 2 (3.5) | 4 (3.5%) | 4 (8) | 3 (15%) | 3 (4.5%) | 2 |

| 3 | 1 | 2 (1.1) | 3 (0.55) | 4 (4.5) | 1 | 2 (4) | 3 | 4 (5.5%) | 3 |

| 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 (0.60) | 3 (4.0) | 4 | 3 (6) | 1 | 2 (3%) | 4 |

| 5 | 1 | 3 (1.3) | 1 | 3 | 2 (1.5%) | 4 | 2 (10%) | 4 | 4 |

| 6 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 (2.5%) | 1 | 4 (20%) | 2 | 3 |

| 7 | 1 | 4 (1.5) | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 8 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 9 | 2 (0.09) | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| 10 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 11 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| 12 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 13 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| 14 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 15 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 16 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 17 | 3 (0.10) | 1 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| 18 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| 19 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| 20 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 21 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| 22 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 23 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| 24 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| 25 | 4 (0.11) | 1 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| 26 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| 27 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 28 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 29 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| 30 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| 31 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| 32 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

4.3. Analysis of Influences of Different Factors on Performance

4.3.1. Range Analysis of Test Results

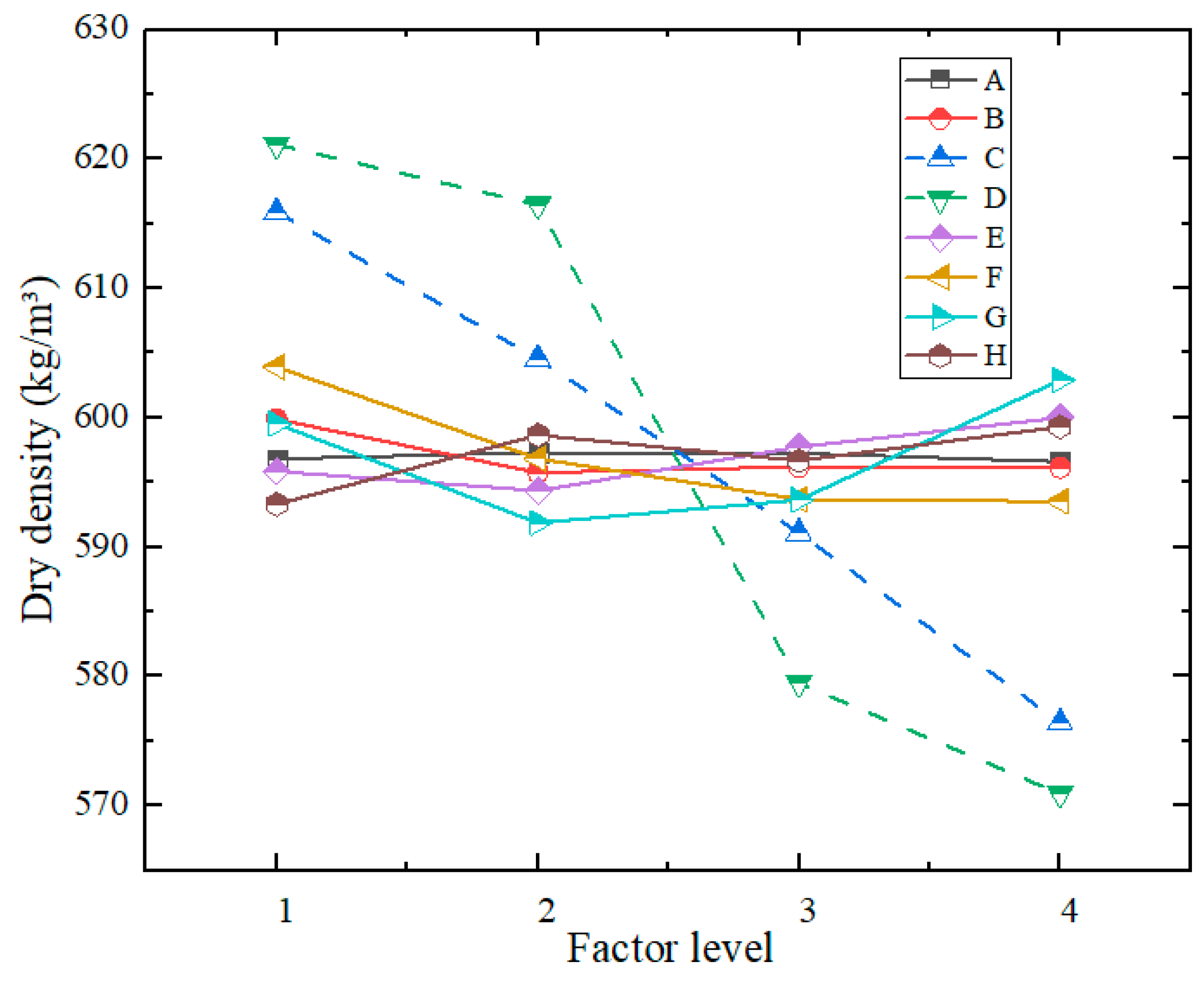

- (1)

- Range Analysis of Dry Density

| Index | Factors | |||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | Empty Column | ||

| Dry Density (kg/m³) | K11 | 4774.53 | 4798.98 | 4927.13 | 4968.90 | 4766.83 | 4831.29 | 4796.23 | 4746.49 | 4790.03 |

| K12 | 4778.42 | 4766.03 | 4836.45 | 4931.66 | 4754.90 | 4774.60 | 4735.01 | 4789.31 | 4789.73 | |

| K13 | 4777.99 | 4769.53 | 4728.79 | 4635.85 | 4781.93 | 4749.58 | 4749.11 | 4773.36 | 4795.16 | |

| K14 | 4772.68 | 4769.08 | 4611.25 | 4567.21 | 4799.96 | 4748.15 | 4823.27 | 4794.46 | 4789.77 | |

| k11 | 596.82 | 599.87 | 615.89 | 621.11 | 595.85 | 603.91 | 599.53 | 593.31 | 598.75 | |

| k12 | 597.30 | 595.75 | 604.56 | 616.46 | 594.36 | 596.83 | 591.88 | 598.66 | 598.72 | |

| k13 | 597.25 | 596.19 | 591.10 | 579.48 | 597.74 | 593.70 | 593.64 | 596.67 | 599.40 | |

| k14 | 596.59 | 596.14 | 576.41 | 570.90 | 600.00 | 593.52 | 602.91 | 599.31 | 598.72 | |

| R | 0.72 | 4.12 | 39.49 | 50.21 | 5.63 | 10.39 | 11.03 | 6.00 | 0.68 | |

| Optimal Level |

2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 4 | ||

- (2)

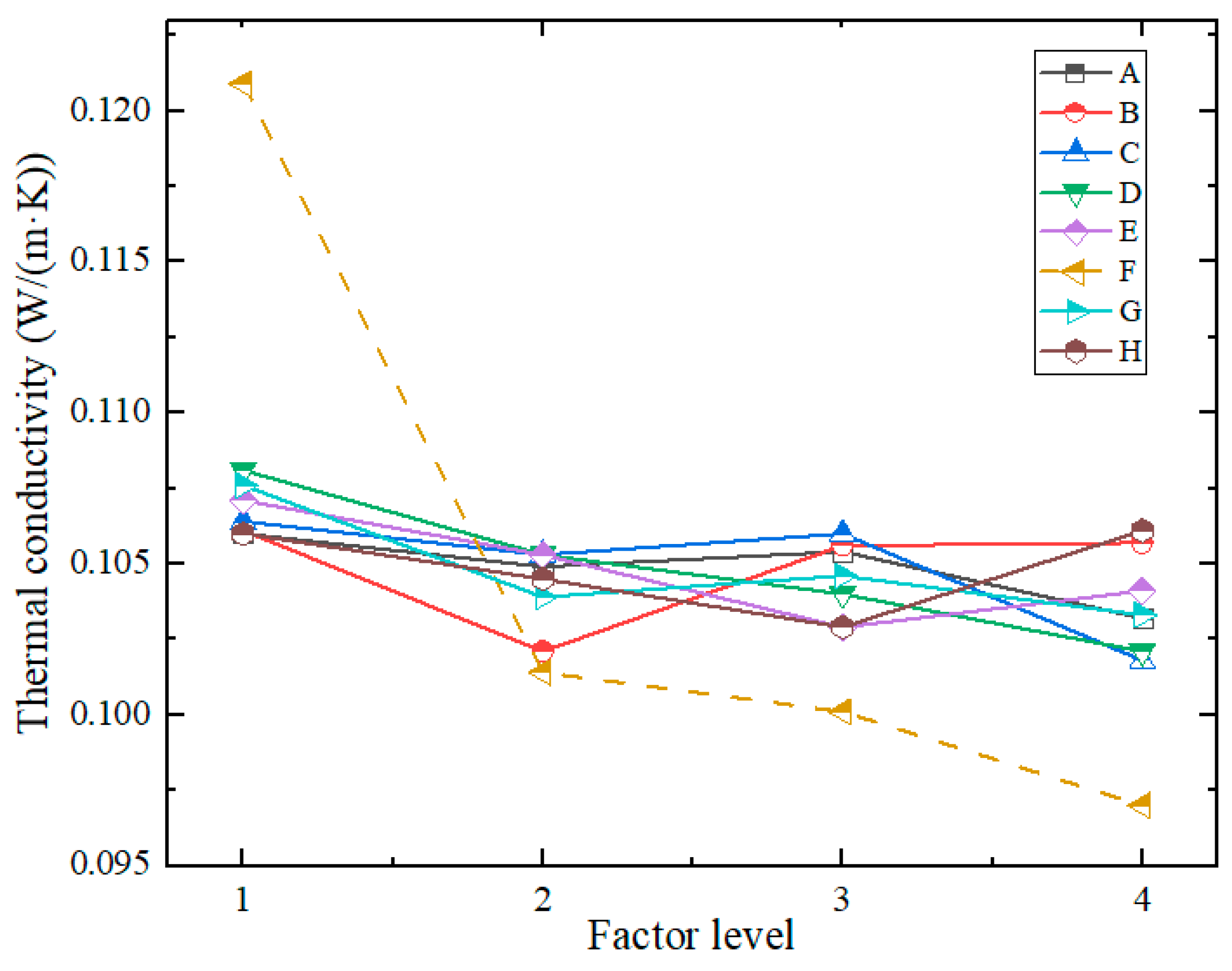

- Range Analysis of Thermal Conductivity

| Index | Factors | |||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | Empty Column | ||

| Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·K)) | K21 | 0.8484 | 0.8486 | 0.8510 | 0.8645 | 0.8564 | 0.9671 | 0.8610 | 0.8478 | 0.8035 |

| K22 | 0.8388 | 0.8169 | 0.8421 | 0.8422 | 0.8426 | 0.8113 | 0.8310 | 0.8358 | 0.7887 | |

| K23 | 0.8430 | 0.8447 | 0.8484 | 0.8319 | 0.8236 | 0.8010 | 0.8371 | 0.8233 | 0.8049 | |

| K24 | 0.8254 | 0.8454 | 0.8141 | 0.8170 | 0.8330 | 0.7761 | 0.8265 | 0.8486 | 0.7885 | |

| k21 | 0.1060 | 0.1061 | 0.1064 | 0.1081 | 0.1071 | 0.1209 | 0.1076 | 0.1060 | 0.1004 | |

| k22 | 0.1049 | 0.1021 | 0.1053 | 0.1053 | 0.1053 | 0.1014 | 0.1039 | 0.1045 | 0.0986 | |

| k23 | 0.1054 | 0.1056 | 0.1060 | 0.1040 | 0.1029 | 0.1001 | 0.1046 | 0.1029 | 0.1006 | |

| k24 | 0.1032 | 0.1057 | 0.1018 | 0.1021 | 0.1041 | 0.0970 | 0.1033 | 0.1061 | 0.0986 | |

| R | 0.0029 | 0.0040 | 0.0046 | 0.0059 | 0.0041 | 0.0239 | 0.0043 | 0.0032 | 0.0021 0.0021 |

|

| Optimal Level |

4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | ||

- (3)

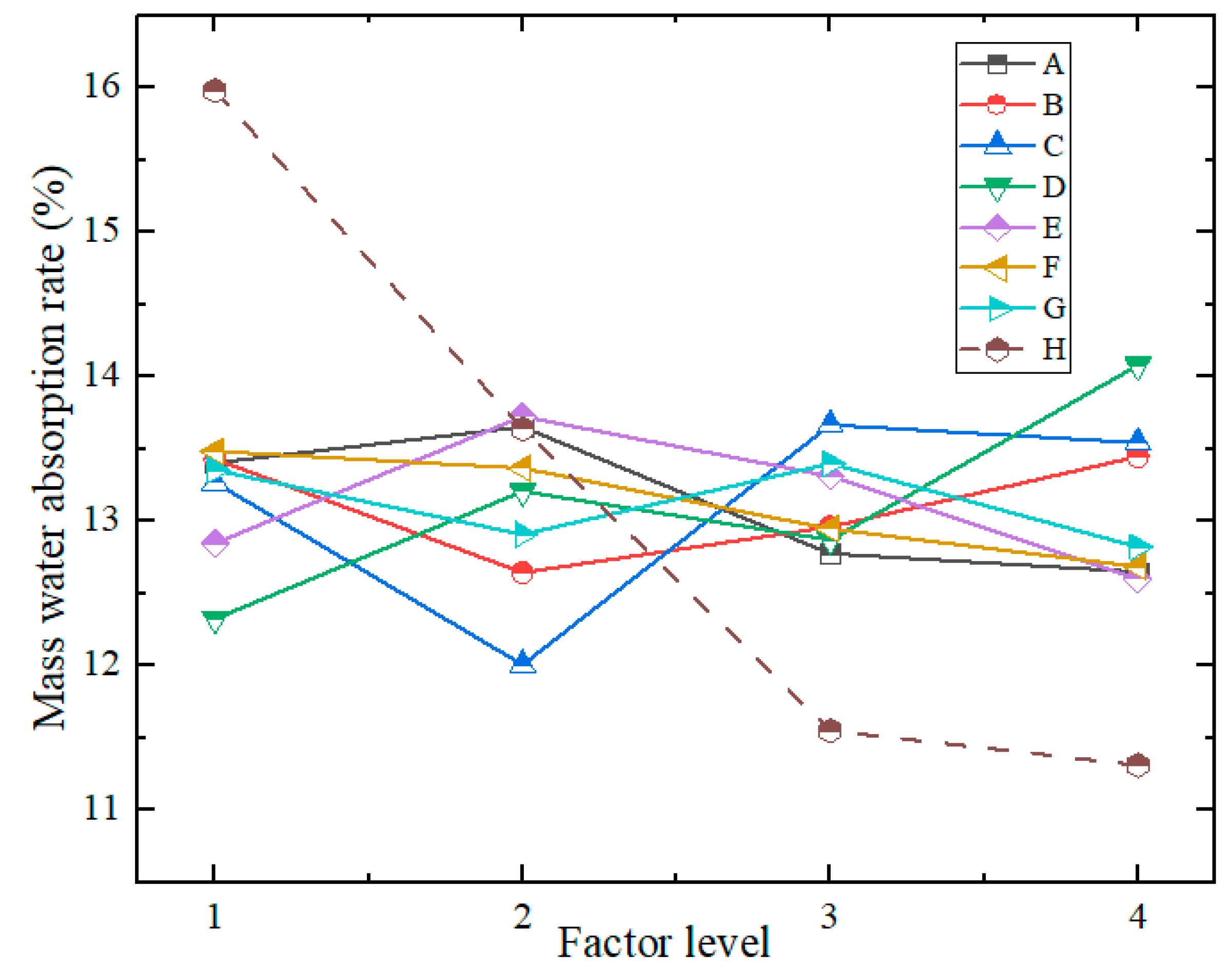

- Mass Water Absorption Rate

| Index | Factors | |||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | Empty Column | ||

| Mass Water Absorption Rate(%) | K31 | 107.210 | 107.416 | 106.121 | 98.576 | 102.751 | 107.851 | 106.806 | 127.835 | 108.301 |

| K32 | 109.207 | 101.146 | 96.030 | 105.642 | 109.775 | 106.910 | 103.246 | 109.090 | 103.271 | |

| K33 | 102.181 | 103.661 | 109.311 | 102.950 | 106.476 | 103.552 | 107.170 | 92.385 | 106.46 | |

| K34 | 101.185 | 107.560 | 108.321 | 112.615 | 100.781 | 101.470 | 102.561 | 90.473 | 101.751 | |

| k31 | 13.401 | 13.427 | 13.265 | 12.322 | 12.844 | 13.481 | 13.351 | 15.979 | 13.538 | |

| k32 | 13.651 | 12.643 | 12.004 | 13.205 | 13.722 | 13.364 | 12.906 | 13.636 | 12.909 | |

| k33 | 12.773 | 12.958 | 13.664 | 12.869 | 13.310 | 12.944 | 13.396 | 11.548 | 13.308 | |

| k34 | 12.648 | 13.445 | 13.540 | 14.077 | 12.598 | 12.684 | 12.820 | 11.309 | 12.719 | |

| R | 1.003 | 0.802 | 1.660 | 1.755 | 1.124 | 0.798 | 0.576 | 4.670 | 0.819 | |

| Optimal Level |

4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

- (4)

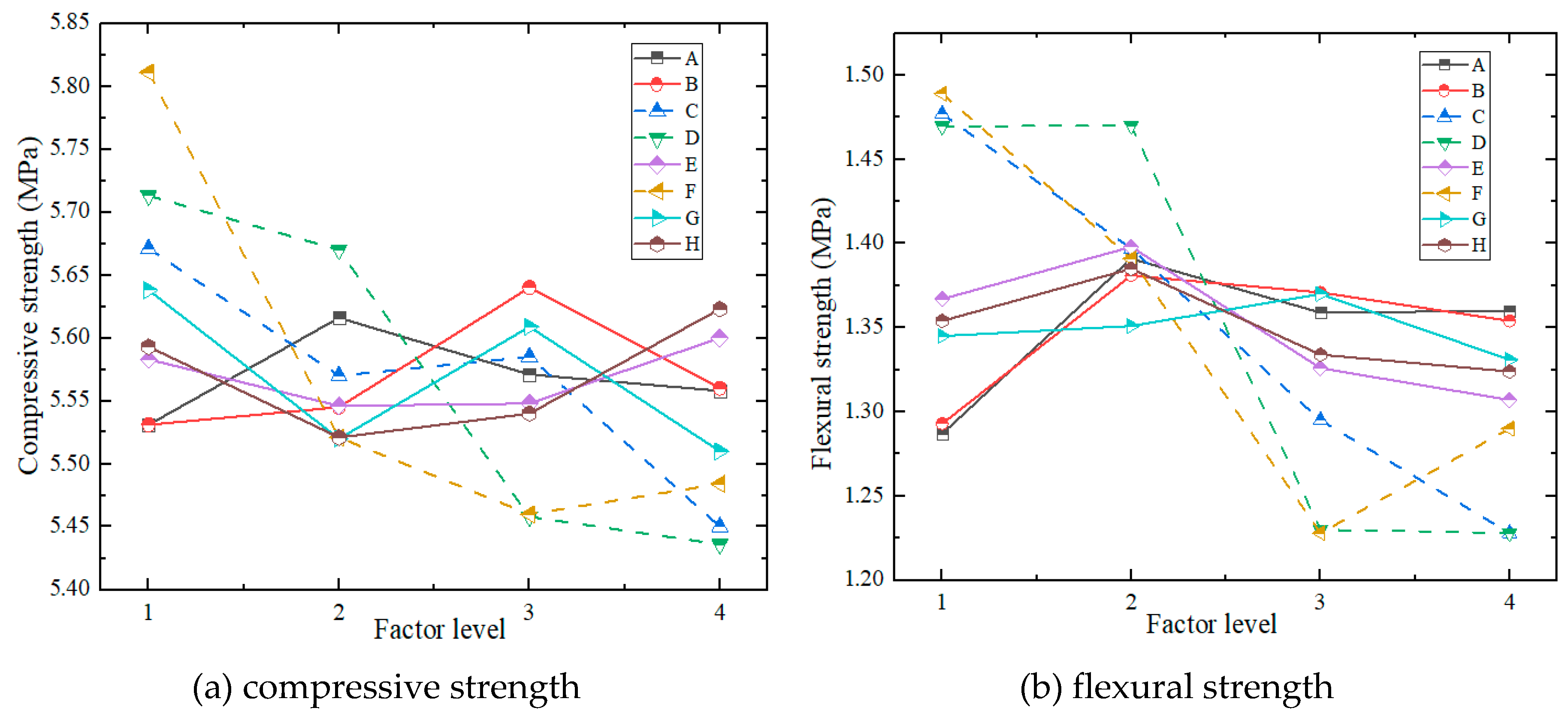

- Mechanical Properties

- (5)

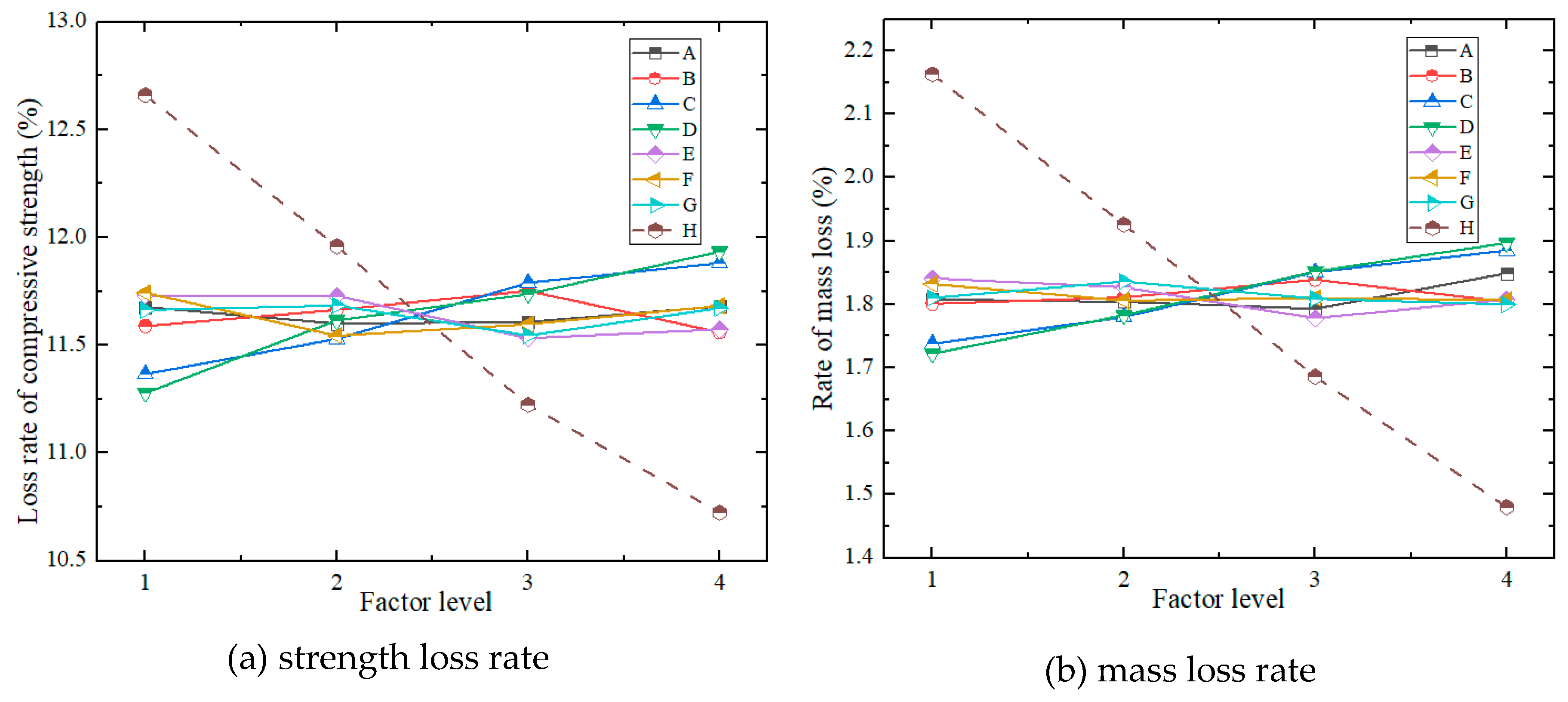

- Frost Resistance

4.3.2. Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) of Test Results

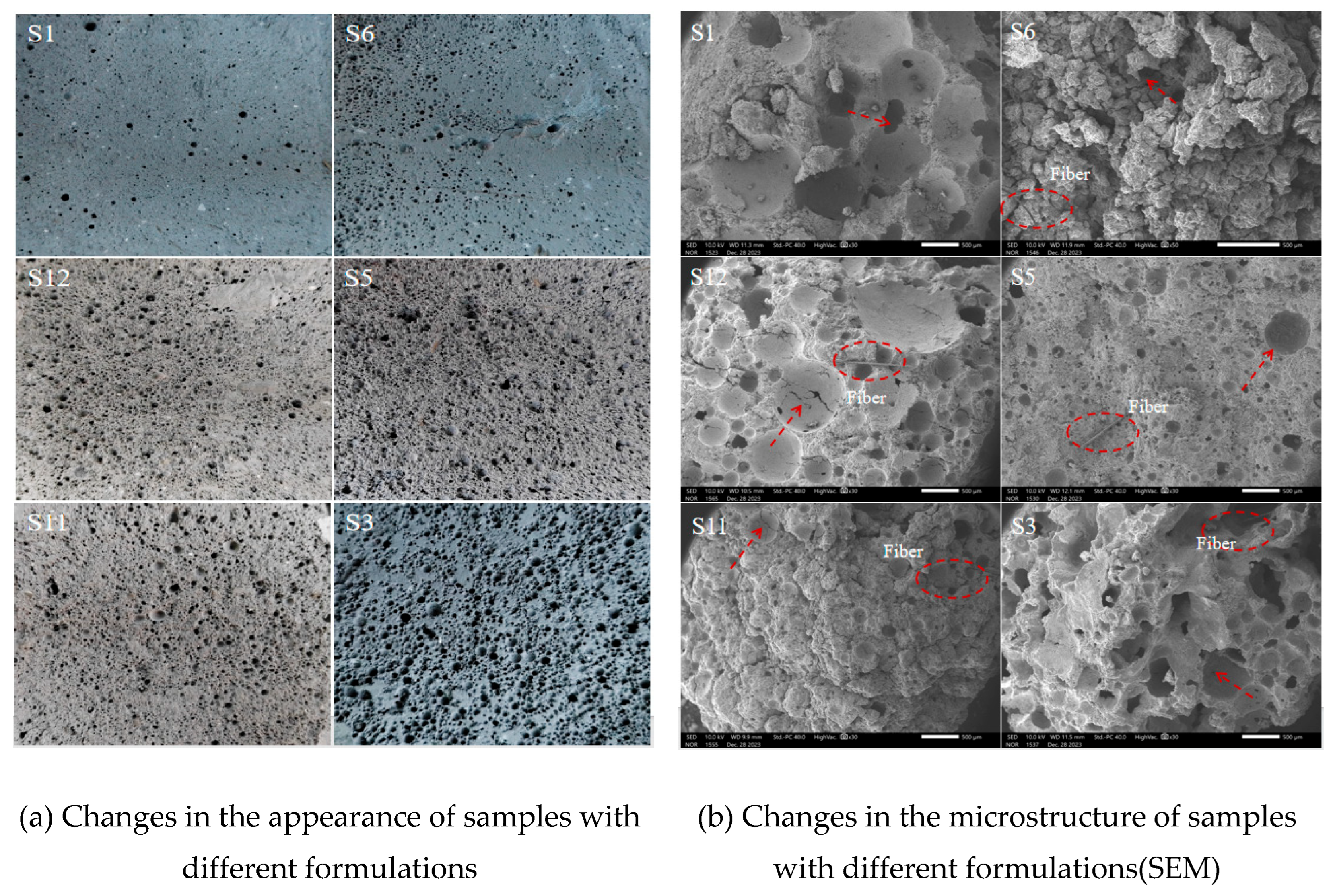

4.3.3. Microscopic Analysis

- (1)

- SEM

- (2)

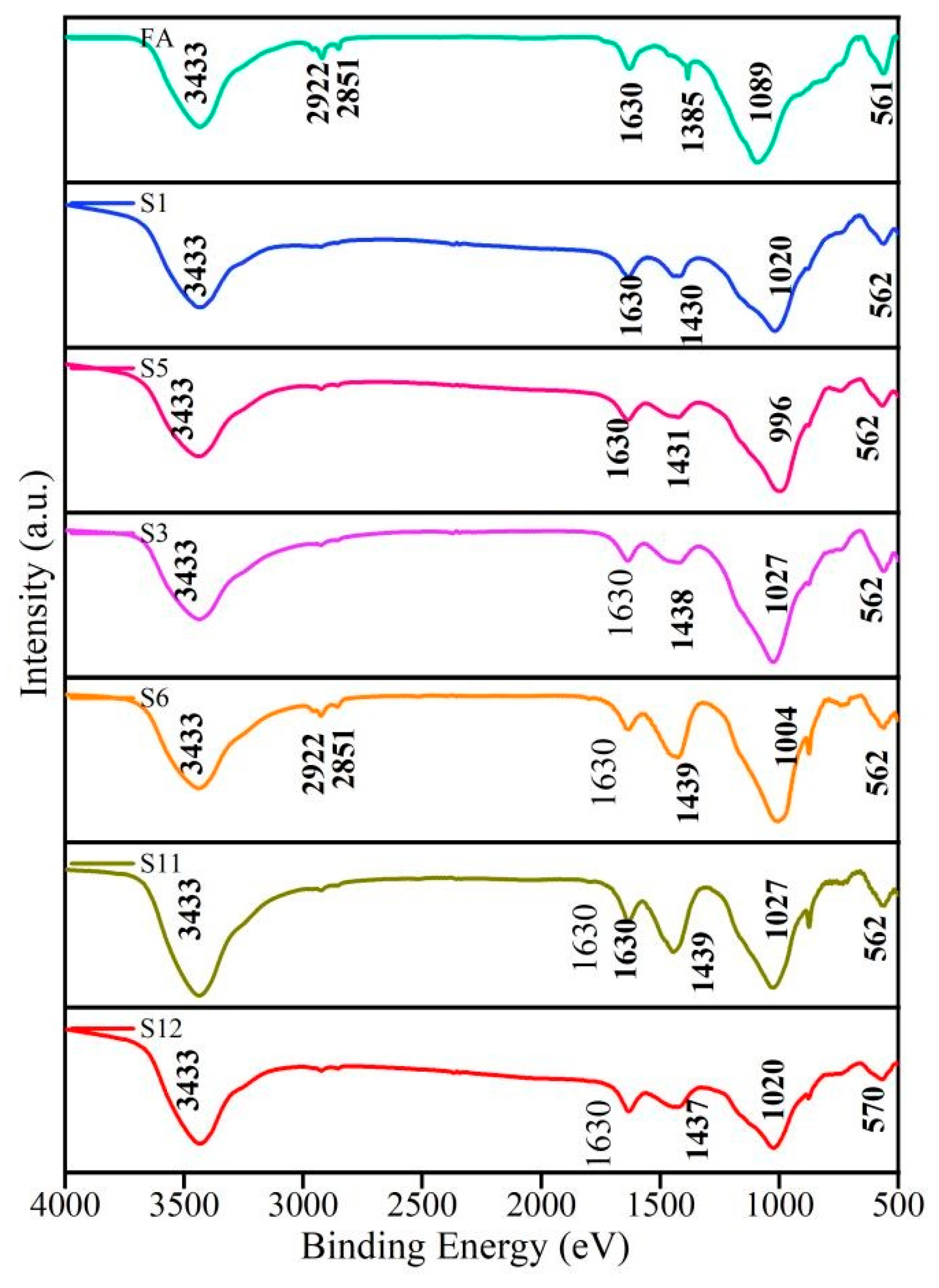

- FTIR

4.4. Determination of Optimal Mix Proportion for AAFC

4.4.1. Mix Proportion Optimization Method

| Index Layer | Performance Indicators | ||||||||||||

| Factor Layer | Factor A | Factor B | ⋅⋅⋅ | Factor H | |||||||||

| Level Layer | A1 | A2 | ⋅⋅⋅ | A4 | B1 | B2 | ⋅⋅⋅ | B4 | ⋅⋅⋅ | H1 | H2 | ⋅⋅⋅ | H4 |

4.4.2. Analysis and Determination of Optimal Mix Proportion

| Factors | ρ | λ | Wr | f | Rf | ε | Fc | Mm | Total Weight Weight |

| A1 | 0.001406 | 0.001355 | 0.019789 | 0.015929 | 0.021806 | 0.007451 | 0.005086 | 0.011342 | 0.010521 |

| A2 | 0.001405 | 0.001371 | 0.019427 | 0.016174 | 0.023565 | 0.007413 | 0.005119 | 0.011370 | 0.010731 |

| A3 | 0.001405 | 0.001364 | 0.020763 | 0.016044 | 0.023033 | 0.007567 | 0.005116 | 0.011436 | 0.010841 |

| A4 | 0.001407 | 0.001393 | 0.020967 | 0.016004 | 0.023050 | 0.007459 | 0.005084 | 0.011093 | 0.010807 |

| B1 | 0.008032 | 0.001869 | 0.015798 | 0.020380 | 0.018552 | 0.015159 | 0.012301 | 0.007790 | 0.012485 |

| B2 | 0.008087 | 0.001941 | 0.016777 | 0.020430 | 0.019814 | 0.015119 | 0.012222 | 0.007748 | 0.012767 |

| B3 | 0.008081 | 0.001878 | 0.016370 | 0.020780 | 0.019673 | 0.014684 | 0.012131 | 0.007629 | 0.012653 |

| B4 | 0.008082 | 0.001876 | 0.015777 | 0.020485 | 0.019428 | 0.015297 | 0.012332 | 0.007776 | 0.012632 |

| C1 | 0.074948 | 0.002170 | 0.033044 | 0.042511 | 0.059972 | 0.058656 | 0.033702 | 0.031382 | 0.042048 |

| C2 | 0.076354 | 0.002193 | 0.036516 | 0.041752 | 0.056736 | 0.053662 | 0.033227 | 0.030637 | 0.041385 |

| C3 | 0.078092 | 0.002177 | 0.032080 | 0.041865 | 0.052582 | 0.052590 | 0.032492 | 0.029458 | 0.040167 |

| C4 | 0.080083 | 0.002269 | 0.032373 | 0.040853 | 0.049872 | 0.050538 | 0.032240 | 0.028928 | 0.039645 |

| D1 | 0.094436 | 0.002759 | 0.037616 | 0.053465 | 0.058186 | 0.114342 | 0.043226 | 0.037643 | 0.055209 |

| D2 | 0.095149 | 0.002832 | 0.035100 | 0.053067 | 0.058202 | 0.128440 | 0.041975 | 0.036368 | 0.056392 |

| D3 | 0.101221 | 0.002867 | 0.036018 | 0.051078 | 0.048713 | 0.150061 | 0.041536 | 0.035001 | 0.058312 |

| D4 | 0.102742 | 0.002919 | 0.032927 | 0.050880 | 0.048599 | 0.167893 | 0.040850 | 0.034166 | 0.060122 |

| E1 | 0.011058 | 0.001923 | 0.023148 | 0.010166 | 0.020177 | 0.012008 | 0.012556 | 0.012551 | 0.012948 |

| E2 | 0.011085 | 0.001954 | 0.021667 | 0.010100 | 0.020630 | 0.012173 | 0.012558 | 0.012643 | 0.012851 |

| E3 | 0.011023 | 0.001999 | 0.022339 | 0.010102 | 0.019567 | 0.012415 | 0.012772 | 0.012991 | 0.012901 |

| E4 | 0.010981 | 0.001977 | 0.023601 | 0.010198 | 0.019295 | 0.012184 | 0.012728 | 0.012774 | 0.012967 |

| F1 | 0.001905 | 0.011869 | 0.016304 | 0.064976 | 0.052377 | 0.008781 | 0.012750 | 0.005270 | 0.021779 |

| F2 | 0.001895 | 0.011718 | 0.015792 | 0.065705 | 0.059349 | 0.008681 | 0.012808 | 0.005282 | 0.022654 |

| F3 | 0.001873 | 0.009831 | 0.015654 | 0.069156 | 0.063528 | 0.008829 | 0.012591 | 0.005207 | 0.023334 |

| F4 | 0.001906 | 0.012250 | 0.016638 | 0.065258 | 0.055032 | 0.008621 | 0.012657 | 0.005279 | 0.022205 |

| G1 | 0.001637 | 0.002063 | 0.011381 | 0.024228 | 0.008808 | 0.008058 | 0.008951 | 0.007552 | 0.009085 |

| G2 | 0.001642 | 0.002078 | 0.011814 | 0.023845 | 0.008684 | 0.008135 | 0.008845 | 0.007438 | 0.009060 |

| G3 | 0.001621 | 0.002006 | 0.011420 | 0.024352 | 0.008646 | 0.008129 | 0.008861 | 0.007547 | 0.009073 |

| G4 | 0.001612 | 0.002090 | 0.011893 | 0.023801 | 0.008555 | 0.007959 | 0.008854 | 0.007590 | 0.009044 |

| H1 | 0.001672 | 0.001500 | 0.075879 | 0.019184 | 0.013437 | 0.004420 | 0.113216 | 0.114664 | 0.042996 |

| H2 | 0.001657 | 0.001521 | 0.088917 | 0.018940 | 0.013747 | 0.004415 | 0.119851 | 0.128726 | 0.047222 |

| H3 | 0.001662 | 0.001545 | 0.104995 | 0.019004 | 0.013241 | 0.004457 | 0.127713 | 0.147112 | 0.052466 |

| H4 | 0.001655 | 0.001498 | 0.107214 | 0.019287 | 0.013144 | 0.004403 | 0.133648 | 0.167607 | 0.056057 |

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- China Association of Building Energy Efficiency, Chongqing University. Research Report on Carbon Emissions in China's Urban and Rural Construction Sector (2024 Edition) [R]. Beijing: China Association of Building Energy Efficiency, 2025.

- Gencel, O., Yavuz Bayraktar, O., Kaplan, G., et al. Lightweight foam concrete containing expanded perlite and glass sand: Physico-mechanical, durability, and insulation properties. Construction and Building Materials, 320, 126187. [CrossRef]

- Zhang W, Yu H, Yin B, et al. Effects of recycled carbon fibers on mechanical and piezoresistive properties and environmental impact in alkali-activated cementitious materials[J].Journal of Cleaner Production,2024,450141902-. [CrossRef]

- Hore S, Shiuly A. Study of thermal conductivity of different types of alkali-activated concrete:a comprehensive review[J] Environment Development and Sustainability,2023,27(3):1-48. [CrossRef]

- Yılmazoğlu U M, Kara O H, Benli A, et al. Sustainable alkali-activated foam concrete with pumice aggregate: Effects of clinoptilolite zeolite and fly ash on strength, durability, and thermal performance[J].Construction and Building Materials, 2025,464140160-140160. [CrossRef]

- Bayraktar Y O, Özel B H, Benli A, et al. Sustainable foam concrete development: Enhancing durability and performance through pine cone powder and fly ash incorporation in alkali-activated geopolymers[J].Construction and Building Materials,2024,457139422-139422. [CrossRef]

- Juntao D, Xiaosong T, Jianzhuang X, et al. Influence of alkaline activator and precursor on the foam characterization and alkali-activated foamed concrete properties[J]. Cement and Concrete Composites, 2024,145. [CrossRef]

- Dang J, Tang X, Xiao J, et al. Role of recycled brick powder and alkaline solution on the properties of eco-friendly alkali-activated foam concrete[J].Journal of Cleaner Production,2024,436140381-. [CrossRef]

- Benli A. Sustainable use of waste glass sand and waste glass powder in alkali-activated slag foam concretes: Physico-mechanical, thermal insulation and durability characteristics[J].Construction and Building Materials,2024, 438137128-137128. [CrossRef]

- Xiong Y, Zhang Z, Huo B, et al. Uncovering the influence of red mud on foam stability and pore features in hybrid alkali-activated foamed concrete[J].Construction and Building Materials,2024,416135309-. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Jiang T, Li C, et al. Effect of Precursor Blending Ratio and Rotation Speed of Mechanically Activated Fly Ash on Properties of Geopolymer Foam Concrete[J].Buildings,2024,14(3):. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Wang Z, Wang Y, et al. Preparation and properties of alkali activated metakaolin-based geopolymer[J].Materials,2016,9(9):767-767. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Li H, Zou S, et al. Experimental research on a feasible rice husk/geopolymer foam building insulation material[J].Energy and Buildings, 2020,226(7):110358. [CrossRef]

- Shakouri S, Bayer Z, Erdoan T S. Development of silica fume-based geopolymer foams[J].Construction and Building Materials,2020,260:120442. [CrossRef]

- N. A B, M. E S, A. S S, et al. Improved Fly Ash Based Structural Foam Concrete with Polypropylene Fiber[J].Journal of Composites Science,2023,7(2):76-76. [CrossRef]

- Cui B L, Liu J, Li S, et al. Study on preparation and properties of cement-based/ geopolymer-polystyrene composite building exterior wall insulation materials[J]. Science of advanced materials, 2018, 10(11):1636-1645. [CrossRef]

- Horvat B, Knez N, Hribar U, et al. Thermal insulation and flammability of composite waste polyurethane foam encapsulated in geopolymer for sustainable building envelope[J].Journal of Cleaner Production,2024,446141387-. [CrossRef]

- Huiskes D, Keulen A, Yu Q, et al. Design and performance evaluation of ultra-lightweight geopolymer concrete[J].Materials Design,2016,89:516-526. [CrossRef]

- Yifei H, Guangzhao Y, Kaikang L. Development of fly ash and slag based high-strength alkali-activated foam concrete[J].Cement and Concrete Composites,2022,104447-. [CrossRef]

- Masi G, Tugnoli A, Bignozzi C M. Lightweight alkali activated composites by direct foaming based on ceramic tile waste and fly ash[J].Ceramics International,2024,50(24PC):55410-55420. [CrossRef]

- Siti A F, Liew M Y, Mohd A B A M, et al. Mechanical Properties and Thermal Conductivity of Lightweight Foamed Geopolymer Concretes[J].IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering,2019,551:012089-. [CrossRef]

- Jaya A N, Yun-Ming L, Cheng-Yong H, et al. Correlation between pore structure, compressive strength and thermal conductivity of porous metakaolin geopolymer[J].Construction and Building Materials,2020,247:118641-. [CrossRef]

- SU L.J., FU G.S., LI F.Y., et al. Preparation and mechanical properties of coal gangue-based foamed geopolymer[J].Bulletin of the Chinese Ceramic Society, 2020, 39(11): 3549-3556. [CrossRef]

- Gao H, Liu H, Liao L, et al. A bifunctional hierarchical porous kaolinite geopolymer with good performance in thermal and sound insulation[J]. Construction and Building Materials, 2020, 251(9):118888-.. [CrossRef]

- BERKOUCHE A, BELKADI A A, NOUI A, et al. Modeling and optimization of eco-friendly cellular foam geopolymer with recycled concrete and glass wastes using Box-Behnken design[J].Structures,2025,76109054-109054. [CrossRef]

- Xian R, Xiang Z, Jianxin Z, et al. Study on mechanical and thermal properties of alkali-excited fly ash aerogel foam concrete[J].Construction and Building Materials,2023,408. [CrossRef]

- Pan P, Yang W, Guo Z. Improvement of thermal properties of foam concrete by incorporating silica aerogel particles[J].Construction and Building Materials,2025,478141450-141450.. [CrossRef]

- Yong cheng J, Qijun S. The Stabilizing Effect of Carboxymethyl Cellulose on Foamed Concrete[J].International Journal of Molecular Sciences,2022,23(24):15473-15473. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China. JGJ/T 341-2014 Technical specification for application of foamed concrete[S]. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press, 2014.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China. JGJ/T 323-2014 Technical specification for application of self-insulation concrete compound block walls[S]. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press, 2014.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China. GB 50574-2010 Technical specification for unified application of wall materials[S]. Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press, 2011.

- Jiangsu Provincial Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. Technical guidelines for ultra-low energy residential buildings (trial implementation)[S]. Nanjing: Jiangsu Provincial Department of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, 2020.

- Shanghai Municipal Housing and Urban-Rural Development Administration. Technical guidelines for ultra-low energy buildings (trial implementation)[S]. Shanghai: Shanghai Municipal Housing and Urban-Rural Development Administration, 2019.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China. GB/T 51350-2019 Technical standard for nearly zero energy buildings[S]. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press, 2019.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China. GB 50176-2016 Code for thermal design of civil buildings[S]. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press, 2017.

- Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the People's Republic of China. GB 50574-2010 Uniform technical code for wall materials used in buildings[S]. Beijing: China Architecture and Building Press, 2010.

- China Building Materials Federation. JC/T 2199-2013 Foaming agent for foamed concrete[S]. Beijing: China Building Materials Industry Press, 2013.

- Taohua Y, Jianzhuang X, Zhenhua D, et al. Geopolymers made of recycled brick and concrete powder-A critical review[J].Construction and Building Materials,2022,330. [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud A A, Johnson U A, Sumiani Y, et al. Engineering performance of sustainable geopolymer foamed and non-foamed concretes[J].Construction and Building Materials,2022,316. [CrossRef]

- Gu G, Xu F, Huang X, et al. Foamed geopolymer: The relationship between rheological properties of geopolymer paste and pore-formation mechanism[J].Journal of Cleaner Production,2020,277. [CrossRef]

- Ryu S G, Lee B Y, Koh T K, et al. The mechanical properties of fly ash-based geopolymer concrete with alkaline activators[J].Construction and Building Materials, 2013,47409-418. [CrossRef]

- Burak B, Yavuz O B, Ahmet B, et al. Effect of using wastewater from the ready-mixed concrete plant on the performance of one-part alkali-activated GBFS/FA composites: Fresh, mechanical and durability properties[J].Journal of Building Engineering,2023,76.. [CrossRef]

- K. S J, Yashida N, K. G. Effect of source materials, additives on the mechanical properties and durability of fly ash and fly ash-slag geopolymer mortar: A review[J].Construction and Building Materials,2021,280. [CrossRef]

- D. C W, Ranjani S I G. Investigations on the performance of xanthan gum as a foam stabilizer and assessment of economic and environmental impacts of foam concrete production[J].Journal of Building Engineering,2024,82108286-. [CrossRef]

- Oguzhan B Y, Gokhan K, Osman G, et al. Physico-mechanical, durability and thermal properties of basalt fiber reinforced foamed concrete containing waste marble powder and slag[J].Construction and Building Materials,2021,288. [CrossRef]

- Chao-Lung H, Damtie M Y, Duy-Hai V, et al. Performance evaluation of alkali activated mortar containing high volume of waste brick powder blended with ground granulated blast furnace slag cured at ambient temperature[J].Construction and Building Materials,2019,223657-667. [CrossRef]

- Youjie S, Yunchuan P ,Shanwen Z, et al. Thermal stability of foams stabilized by fluorocarbon and hydrocarbon surfactants in presence of nanoparticles with different specific surface areas[J].Journal of Molecular Liquids,2022,365. [CrossRef]

- Liu X, Wu Y, Li M, et al. Effects of graphene oxide on microstructure and mechanical properties of graphene oxide-geopolymer composites[J]. Construction and Building Materials,2020,247118544-118544. [CrossRef]

- Lijuan S, Guosheng F, Bing L, et al. Working performance and microscopic mechanistic analyses of municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) fly ash-based self-foaming filling materials[J]. Construction and Building Materials,2022,361. [CrossRef]

- Pasupathy K, Ramakrishnan S, Sanjayan J. Enhancing the mechanical and thermal properties of aerated geopolymer concrete using porous lightweight aggregates[J].Construction and Building Materials,2020,264. [CrossRef]

- Yu P, Kirkpatrick R J, Poe B, et al. Structure of calcium silicate hydrate (C-S-H): Near-, Mid-, and far-infrared spectroscopy[J].Journal of the American Ceramic Society, 2010, 82(3):742-748. [CrossRef]

| First-level Indicator Type | Second-level Indicator Name | Target Value |

| Bulk Density | Dry Density ρ | A06 (≤650 kg/m3) |

| Thermal Performance | Thermal Transmittance K | Wall Thickness 300mm,≤0.4 W/m2·K |

| Thermal Conductivity λ | ≤0.1216W/(m·K) | |

| Fire Resistance | Combustion Performance Rating FRL | Class A (Non-Combustible Material) |

| Water Resistance | Mass Water Absorption Wr | ≤5% |

| Mechanical Properties | Compressive Strength f | ≥5 MPa |

| Flexural Strength Rf | ≥1.0 MPa | |

| Drying Shrinkage ε | ≤1 mm/m | |

| Frost Resistance(F25) | Strength Loss Rate Fc | ≤25% |

| Mass Loss Rate Mm | ≤5% |

| Project | Foaming Agent Multiple n | 1-hour sedimentation distance (mm) |

Sedimentation distance (cm/h) | ||

| First-class product | Qualified Product | First-class product | Qualified Product | ||

| Indicator | 15~30 | ≤50 | ≤70 | ≤70 | ≤80 |

| Test Results | 28 | 41.1 | 59.6 | ||

| Particle size(mm) | Bulk density (kg/m3) | Cylinder pressure strength (MPa) | Thermal conductivity (W/(m⋅K)) | Water absorption rate(%) | Floating rate(%) | Surface vitrification closed-cell rate (%) | Linear shrinkage rate (%) |

| 1~3 | 116 | 0.52 | 0.049 | 30 | ≥80 | ≥80 | 0.29 |

| Fiber length mm | Relative density g/cm3 | Diameter μm | Elastic modulus GPa | Tensile strength MPa | Ultimate elongation % |

| 6 | 2.65 | 17 | 7.6 | 1050 | 3 |

| Particle size μm | Bulk density kg/m3 |

Pore diamete rnm | Porosity % |

Specific surface area m2/g | Thermal conductivity W/(m·K) | Surface properties |

| 15~50 | 40~60 | 20~50 | >90 | 500~800 | <0.013 | Hydrophobic |

| FA (kg/m3) | Sodium silicate (kg/m3) | Sodium hydroxide (kg/m3) | Foam dosage (m3/m3) | Water-to-binder Ratio | Additional water dosage (kg/m3) |

| 396.73 | 213.45 | 27.689 | 0.646 | 0.4 | 21.04 |

| Dry density | Thermal conductivity | Mass water absorption rate | Mechanical properties | Frost resistance (F25) | |||

|

ρ (kg/m3) |

λ (W/(m·K)) |

Wr (%) |

f (MPa) |

Rf (MPa) |

ε (mm/m) |

Fc (%) |

Mm (%) |

| 632.5 | 0.1975 | 57.1% | 3.76 | 0.823 | 1.432 | 44.53% | 17.36% |

| Index | Bulk Density | Thermal Performance | Water Resistance | Mechanical Properties | Frost Resistance(F25) | |||

| NO. |

ρ kg/m3 |

λ W/(m·K) |

Wr % |

f MPa |

Rf MPa |

ε mm/m |

Fc % |

Mm % |

| 1 | 654.82 | 0.1377 | 6.50 | 6.12 | 1.77 | 0.849 | 12.136 | 2.028 |

| 2 | 633.58 | 0.0990 | 4.41 | 5.47 | 1.21 | 0.841 | 11.124 | 1.623 |

| 3 | 568.23 | 0.1001 | 4.55 | 5.55 | 1.32 | 0.653 | 11.087 | 1.597 |

| 4 | 568.34 | 0.0994 | 5.50 | 5.23 | 1.01 | 0.747 | 12.391 | 2.016 |

| 5 | 581.37 | 0.0977 | 4.51 | 5.47 | 1.24 | 0.657 | 10.553 | 1.403 |

| 6 | 587.38 | 0.1138 | 5.74 | 5.62 | 1.38 | 0.623 | 12.245 | 1.981 |

| 7 | 592.23 | 0.1011 | 7.21 | 5.48 | 1.26 | 0.841 | 12.743 | 2.117 |

| 8 | 588.58 | 0.0996 | 4.46 | 5.31 | 1.11 | 0.933 | 11.135 | 1.701 |

| 9 | 563.62 | 0.0980 | 7.39 | 5.34 | 1.15 | 0.641 | 13.112 | 2.243 |

| 10 | 578.95 | 0.1137 | 4.69 | 5.58 | 1.37 | 0.738 | 11.653 | 1.781 |

| 11 | 655.77 | 0.1015 | 4.41 | 5.62 | 1.39 | 0.873 | 10.127 | 1.283 |

| 12 | 624.32 | 0.1022 | 5.33 | 6.11 | 1.85 | 0.822 | 11.753 | 1.887 |

| 13 | 618.79 | 0.1274 | 4.61 | 5.56 | 1.36 | 0.847 | 11.213 | 1.581 |

| 14 | 580.13 | 0.0968 | 5.55 | 5.64 | 1.42 | 1.025 | 11.873 | 1.904 |

| 15 | 588.27 | 0.1002 | 6.89 | 5.68 | 1.44 | 0.621 | 12.032 | 2.104 |

| 16 | 568.57 | 0.0990 | 4.81 | 5.4 | 1.15 | 0.608 | 11.038 | 1.647 |

| 17 | 621.65 | 0.1023 | 5.11 | 5.55 | 1.34 | 0.929 | 11.214 | 1.724 |

| 18 | 586.41 | 0.0988 | 4.64 | 5.46 | 1.18 | 0.841 | 10.876 | 1.549 |

| 19 | 579.69 | 0.1111 | 4.86 | 5.72 | 1.47 | 0.537 | 11.239 | 1.673 |

| 20 | 577.63 | 0.0970 | 4.77 | 5.24 | 1.08 | 0.718 | 13.037 | 2.221 |

| 21 | 574.29 | 0.1012 | 4.66 | 5.46 | 1.20 | 0.703 | 11.214 | 1.732 |

| 22 | 556.83 | 0.1028 | 7.41 | 5.33 | 1.14 | 0.704 | 13.463 | 2.362 |

| 23 | 643.22 | 0.0994 | 4.94 | 5.78 | 1.68 | 0.715 | 11.463 | 1.734 |

| 24 | 638.27 | 0.1304 | 4.49 | 6.03 | 1.78 | 0.903 | 10.357 | 1.352 |

| 25 | 578.61 | 0.0992 | 5.77 | 5.26 | 1.11 | 0.554 | 12.154 | 2.032 |

| 26 | 581.34 | 0.0999 | 4.45 | 5.47 | 1.21 | 0.694 | 10.443 | 1.427 |

| 27 | 604.32 | 0.0954 | 4.50 | 5.66 | 1.44 | 0.918 | 11.154 | 1.683 |

| 28 | 587.73 | 0.1102 | 6.55 | 5.78 | 1.49 | 0.835 | 12.522 | 2.124 |

| 29 | 645.38 | 0.1042 | 4.57 | 5.72 | 1.72 | 0.803 | 11.223 | 1.645 |

| 30 | 625.36 | 0.1008 | 4.41 | 5.77 | 1.52 | 0.922 | 12.231 | 2.102 |

| 31 | 585.66 | 0.1228 | 5.70 | 5.53 | 1.29 | 0.724 | 12.576 | 2.133 |

| 32 | 564.28 | 0.0929 | 4.52 | 5.27 | 1.11 | 0.687 | 11.137 | 1.644 |

| Index | Factors | |||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | Empty Column | ||

| Compressive Strength (MPa) | K41 | 44.25 | 44.25 | 45.37 | 45.7 | 44.66 | 46.49 | 45.1 | 44.74 | 45.15 |

| K42 | 44.93 | 44.36 | 44.56 | 45.36 | 44.37 | 44.17 | 44.16 | 44.17 | 45.44 | |

| K43 | 44.57 | 45.12 | 44.68 | 43.66 | 44.38 | 43.68 | 44.87 | 44.32 | 45.51 | |

| K44 | 44.46 | 44.48 | 43.6 | 43.49 | 44.8 | 43.87 | 44.08 | 44.98 | 45.12 | |

| k41 | 5.531 | 5.531 | 5.671 | 5.713 | 5.583 | 5.811 | 5.638 | 5.593 | 5.644 | |

| k42 | 5.616 | 5.545 | 5.570 | 5.670 | 5.546 | 5.521 | 5.520 | 5.521 | 5.680 | |

| k43 | 5.571 | 5.640 | 5.585 | 5.458 | 5.548 | 5.460 | 5.609 | 5.540 | 5.689 | |

| k44 | 5.558 | 5.560 | 5.450 | 5.436 | 5.600 | 5.484 | 5.510 | 5.623 | 5.640 | |

| R | 0.085 | 0.109 | 0.221 | 0.276 | 0.054 | 0.351 | 0.128 | 0.101 | 0.049 | |

| Optimal Level |

2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | ||

| Index | Factors | |||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | Empty Column | ||

| Flexural Strength (MPa) | K51 | 10.30 | 10.34 | 11.82 | 11.76 | 10.94 | 11.91 | 10.76 | 10.83 | 11.21 |

| K52 | 11.13 | 11.04 | 11.18 | 11.76 | 11.18 | 11.13 | 10.81 | 11.08 | 11.31 | |

| K53 | 10.88 | 10.97 | 10.36 | 9.84 | 10.61 | 9.82 | 10.96 | 10.67 | 11.33 | |

| K54 | 10.88 | 10.83 | 9.83 | 9.82 | 10.46 | 10.32 | 10.65 | 10.60 | 10.99 | |

| k51 | 1.287 | 1.293 | 1.477 | 1.469 | 1.367 | 1.489 | 1.345 | 1.354 | 1.401 | |

| k52 | 1.391 | 1.381 | 1.397 | 1.4701 | 1.398 | 1.391 | 1.351 | 1.385 | 1.414 | |

| k53 | 1.359 | 1.371 | 1.295 | 1.230 | 1.326 | 1.228 | 1.370 | 1.334 | 1.416 | |

| k54 | 1.360 | 1.354 | 1.228 | 1.228 | 1.307 | 1.290 | 1.331 | 1.324 | 1.373 | |

| R | 0.104 | 0.088 | 0.249 | 0.243 | 0.090 | 0.261 | 0.039 | 0.061 | 0.043 | |

| Optimal Level |

2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | ||

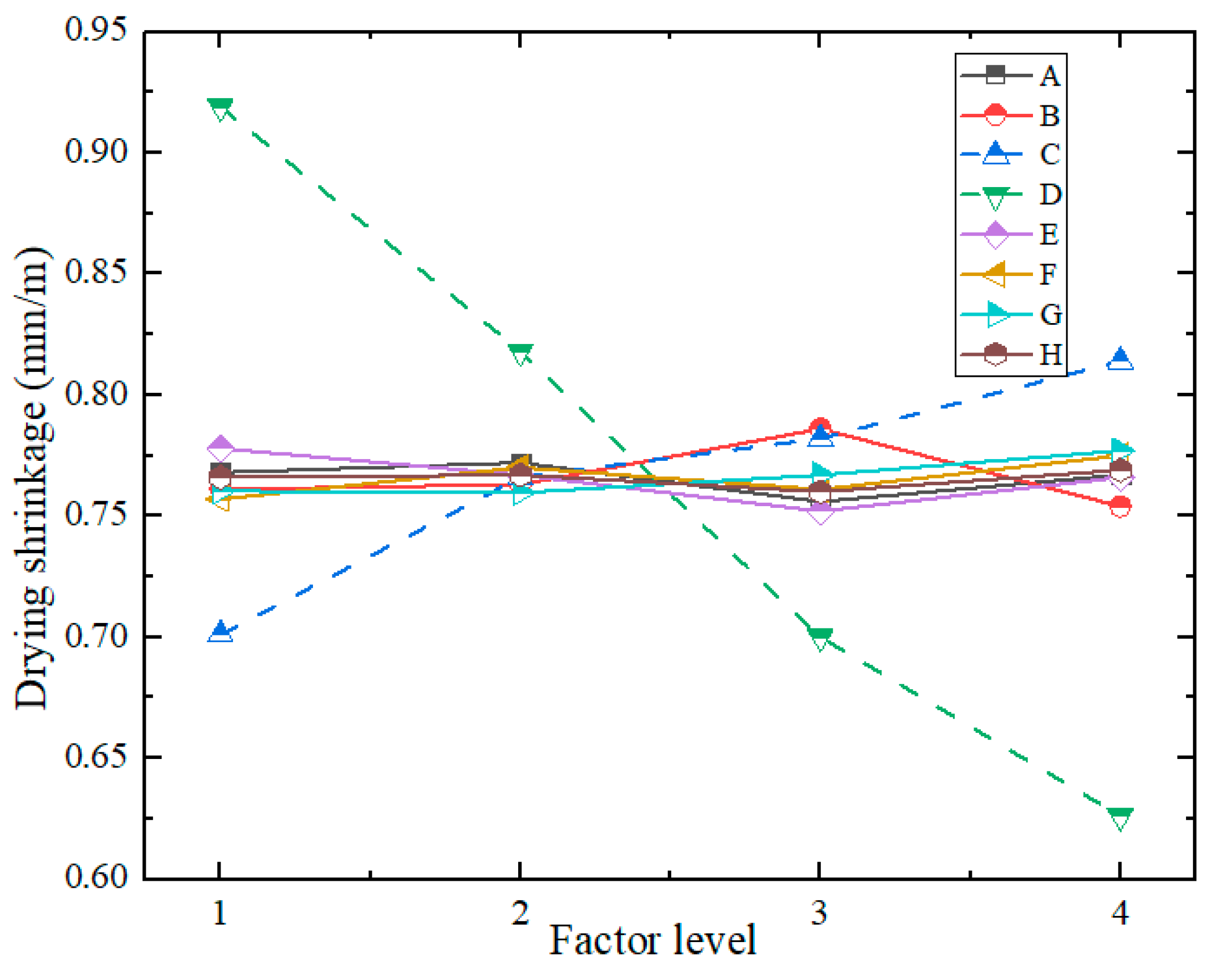

| Index | Factors | |||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | Empty Column | ||

| Drying Shrinkage (mm/m) | K61 | 6.144 | 6.087 | 5.609 | 7.352 | 6.221 | 6.056 | 6.082 | 6.131 | 6.11 |

| K62 | 6.175 | 6.103 | 6.131 | 6.545 | 6.137 | 6.159 | 6.077 | 6.139 | 6.103 | |

| K63 | 6.05 | 6.284 | 6.256 | 5.602 | 6.017 | 6.089 | 6.135 | 6.081 | 6.105 | |

| K64 | 6.137 | 6.032 | 6.51 | 5.007 | 6.131 | 6.202 | 6.212 | 6.155 | 6.049 | |

| k61 | 0.768 | 0.761 | 0.701 | 0.919 | 0.778 | 0.757 | 0.7603 | 0.766 | 0.764 | |

| k62 | 0.772 | 0.763 | 0.766 | 0.818 | 0.767 | 0.770 | 0.7596 | 0.767 | 0.763 | |

| k63 | 0.756 | 0.786 | 0.782 | 0.700 | 0.752 | 0.761 | 0.767 | 0.760 | 0.763 | |

| k64 | 0.767 | 0.754 | 0.814 | 0.626 | 0.766 | 0.775 | 0.777 | 0.769 | 0.756 | |

| R | 0.016 | 0.031 | 0.113 | 0.293 | 0.026 | 0.018 | 0.017 | 0.009 | 0.008 | |

| Optimal Level |

3 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Index | Factors | |||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | Empty Column | ||

| Strength Loss Rate (%) | K71 | 93.414 | 92.712 | 90.927 | 90.227 | 93.846 | 93.941 | 93.301 | 101.276 | 93.958 |

| K72 | 92.801 | 93.310 | 92.228 | 92.917 | 93.830 | 92.350 | 93.475 | 95.669 | 93.409 | |

| K73 | 92.863 | 94.015 | 94.313 | 93.899 | 92.261 | 92.774 | 92.363 | 89.780 | 93.333 | |

| K74 | 93.440 | 92.481 | 95.050 | 95.475 | 92.581 | 93.453 | 93.379 | 85.793 | 93.818 | |

| k71 | 11.677 | 11.589 | 11.366 | 11.278 | 11.731 | 11.743 | 11.663 | 12.660 | 11.745 | |

| k72 | 11.600 | 11.664 | 11.529 | 11.615 | 11.729 | 11.544 | 11.684 | 11.959 | 11.676 | |

| k73 | 11.608 | 11.752 | 11.789 | 11.737 | 11.533 | 11.597 | 11.545 | 11.223 | 11.667 | |

| k74 | 11.680 | 11.560 | 11.881 | 11.934 | 11.573 | 11.682 | 11.672 | 10.724 | 11.727 | |

| R | 0.080 | 0.192 | 0.515 | 0.656 | 0.198 | 0.199 | 0.139 | 1.935 | 0.078 | |

| Optimal Level |

2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Index | Factors | |||||||||

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | Empty Column | ||

| Mass Loss Rate (%) | K81 | 14.466 | 14.407 | 13.902 | 13.777 | 14.724 | 14.653 | 14.478 | 17.301 | 14.523 |

| K82 | 14.43 | 14.484 | 14.24 | 14.26 | 14.617 | 14.447 | 14.691 | 15.411 | 14.556 | |

| K83 | 14.347 | 14.71 | 14.81 | 14.817 | 14.225 | 14.478 | 14.468 | 13.485 | 14.308 | |

| K84 | 14.79 | 14.432 | 15.081 | 15.179 | 14.467 | 14.455 | 14.396 | 11.836 | 14.377 | |

| k81 | 1.808 | 1.801 | 1.738 | 1.722 | 1.841 | 1.832 | 1.810 | 2.163 | 1.815 | |

| k82 | 1.804 | 1.811 | 1.780 | 1.783 | 1.827 | 1.806 | 1.836 | 1.926 | 1.820 | |

| k83 | 1.793 | 1.839 | 1.851 | 1.852 | 1.778 | 1.810 | 1.809 | 1.686 | 1.789 | |

| k84 | 1.849 | 1.804 | 1.885 | 1.897 | 1.808 | 1.807 | 1.800 | 1.480 | 1.797 | |

| R | 0.055 | 0.038 | 0.147 | 0.175 | 0.062 | 0.026 | 0.037 | 0.683 | 0.031 | |

| Optimal Level |

3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Index | Source of variance | Sum of squared deviations | Degree of freedom | Mean square Ms | F Value | Significance | |

| Dry Density (kg/m³) | A | SSA | 2.870 | 3 | 0.957 | 0.044 | |

| B | SSB | 89.649 | 3 | 29.883 | 1.365 | ||

| C | SSC | 6983.224 | 3 | 2327.741 | 106.320 | ** | |

| D | SSD | 15584.462 | 3 | 5194.821 | 237.275 | ** | |

| E | SSE | 142.314 | 3 | 47.438 | 2.167 | ||

| F | SSF | 566.568 | 3 | 188.856 | 8.626 | (*) | |

| G | SSG | 630.865 | 3 | 210.288 | 9.605 | * | |

| H | SSH | 174.463 | 3 | 58.154 | 2.656 | ||

| Error E | SSE | 65.681 | 3 | 21.894 | |||

| Sum | SST | 24240.096 | 31 | ||||

| Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·K)) | A | SSA | 3.59384E-05 | 3 | 1.198E-05 | 2.7289 | |

| B | SSB | 8.13828E-05 | 3 | 2.713E-05 | 6.1796 | (*) | |

| C | SSC | 0.000107308 | 3 | 3.577E-05 | 8.1481 | (*) | |

| D | SSD | 0.000149903 | 3 | 4.997E-05 | 11.3825 | * | |

| E | SSE | 7.37212E-05 | 3 | 2.457E-05 | 5.5978 | (*) | |

| F | SSF | 0.002821489 | 3 | 0.0009405 | 214.2426 | ** | |

| G | SSG | 8.81847E-05 | 3 | 2.939E-05 | 6.6961 | (*) | |

| H | SSH | 5.35474E-05 | 3 | 1.785E-05 | 4.0660 | ||

| Error E | SSE | 1.32E-05 | 3 | 4.39E-06 | |||

| Sum | SST | 0.003425 | 31 | ||||

| Mass Water Absorption Rate (%) | A | SSA | 18.2856 | 3 | 6.0952 | 8.5416 | (*) |

| B | SSB | 16.3877 | 3 | 5.4626 | 7.6550 | (*) | |

| C | SSC | 45.2873 | 3 | 15.0958 | 21.1547 | * | |

| D | SSD | 57.3406 | 3 | 19.1135 | 26.7850 | * | |

| E | SSE | 31.0806 | 3 | 10.3602 | 14.5184 | * | |

| F | SSF | 12.6851 | 3 | 4.2284 | 5.9255 | (*) | |

| G | SSG | 9.5971 | 3 | 3.1990 | 4.4830 | ||

| H | SSH | 80.2010 | 3 | 26.7337 | 37.4636 | ** | |

| Error E | SSE | 2.141 | 3 | 0.714 | |||

| Sum | SST | 273.0056 | 31 | ||||

| Compressive Strength (MPa) | A | SSA | 0.0335 | 3 | 0.0112 | 9.8946 | * |

| B | SSB | 0.0436 | 3 | 0.0145 | 12.8866 | * | |

| C | SSC | 0.2581 | 3 | 0.0860 | 76.2713 | ** | |

| D | SSD | 0.3975 | 3 | 0.1325 | 117.4714 | ** | |

| E | SSE | 0.0165 | 3 | 0.0055 | 4.8859 | ||

| F | SSF | 0.4868 | 3 | 0.1623 | 143.8448 | ** | |

| G | SSG | 0.0281 | 3 | 0.0094 | 8.3063 | (*) | |

| H | SSH | 0.0304 | 3 | 0.0101 | 8.9712 | (*) | |

| Error E | SSE | 0.0034 | 3 | 0.0011 | |||

| Sum | SST | 1.2979 | 31 | ||||

| Flexural Strength (MPa) | A | SSA | 0.2966 | 3 | 0.0989 | 29.0104 | * |

| B | SSB | 0.1443 | 3 | 0.0481 | 14.1092 | * | |

| C | SSC | 0.3822 | 3 | 0.1274 | 37.3773 | ** | |

| D | SSD | 0.3745 | 3 | 0.1248 | 36.6244 | ** | |

| E | SSE | 0.2225 | 3 | 0.0742 | 21.7644 | * | |

| F | SSF | 0.4065 | 3 | 0.1355 | 39.7534 | ** | |

| G | SSG | 0.0900 | 3 | 0.0300 | 8.7988 | (*) | |

| H | SSH | 0.0943 | 3 | 0.0314 | 9.2191 | (*) | |

| Error E | SSE | 0.0102 | 3 | 3.41E-03 | |||

| Sum | SST | 2.0210 | 31 | ||||

| Drying Shrinkage (mm/m) | A | SSA | 0.0349 | 3 | 0.0116 | 2.0999 | |

| B | SSB | 0.1196 | 3 | 0.0399 | 7.2035 | (*) | |

| C | SSC | 0.1311 | 3 | 0.0437 | 7.8952 | (*) | |

| D | SSD | 0.4267 | 3 | 0.1422 | 25.6941 | * | |

| E | SSE | 0.0486 | 3 | 0.0162 | 2.9261 | ||

| F | SSF | 0.0413 | 3 | 0.0138 | 2.4885 | ||

| G | SSG | 0.0382 | 3 | 0.0127 | 2.3019 | ||

| H | SSH | 0.0295 | 3 | 0.0098 | 1.7760 | ||

| Error E | SSE | 0.0166 | 3 | 0.0055 | |||

| Sum | SST | 0.8866 | 31 | ||||

| Strength Loss Rate (%) | A | SSA | 7.2638 | 3 | 2.4213 | 5.0263 | |

| B | SSB | 11.8639 | 3 | 3.9546 | 8.2094 | (*) | |

| C | SSC | 20.5288 | 3 | 6.8429 | 14.2052 | * | |

| D | SSD | 21.6072 | 3 | 7.2024 | 14.9514 | * | |

| E | SSE | 14.2014 | 3 | 4.7338 | 9.8269 | * | |

| F | SSF | 12.1380 | 3 | 4.0460 | 8.3990 | (*) | |

| G | SSG | 9.3936 | 3 | 3.1312 | 6.5000 | (*) | |

| H | SSH | 45.0139 | 3 | 15.0046 | 31.1481 | ** | |

| Error E | SSE | 1.4452 | 3 | 0.4817 | |||

| Sum | SST | 143.4557 | 31 | ||||

| Mass Loss Rate (%) | A | SSA | 0.2816 | 3 | 0.0939 | 8.4316 | (*) |

| B | SSB | 0.2977 | 3 | 0.0992 | 8.9154 | (*) | |

| C | SSC | 0.9241 | 3 | 0.3080 | 27.6718 | * | |

| D | SSD | 1.0934 | 3 | 0.3645 | 32.7423 | ** | |

| E | SSE | 0.3931 | 3 | 0.1310 | 11.7724 | * | |

| F | SSF | 0.1694 | 3 | 0.0565 | 5.0716 | ||

| G | SSG | 0.2258 | 3 | 0.0753 | 6.7621 | (*) | |

| H | SSH | 1.9874 | 3 | 0.6625 | 59.5113 | ** | |

| Error E | SSE | 0.3339 | 3 | 0.1113 | |||

| Sum | SST | 5.7064 | 31 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).