Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

21 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Description and Sampling Conditions

2.2. Experimental Design and Control Groups

2.3. Measurement Methods and Quality Control

2.4. Data Analysis and Model Equations

2.5. Error Assessment and Data Reliability

3. Results and Discussion

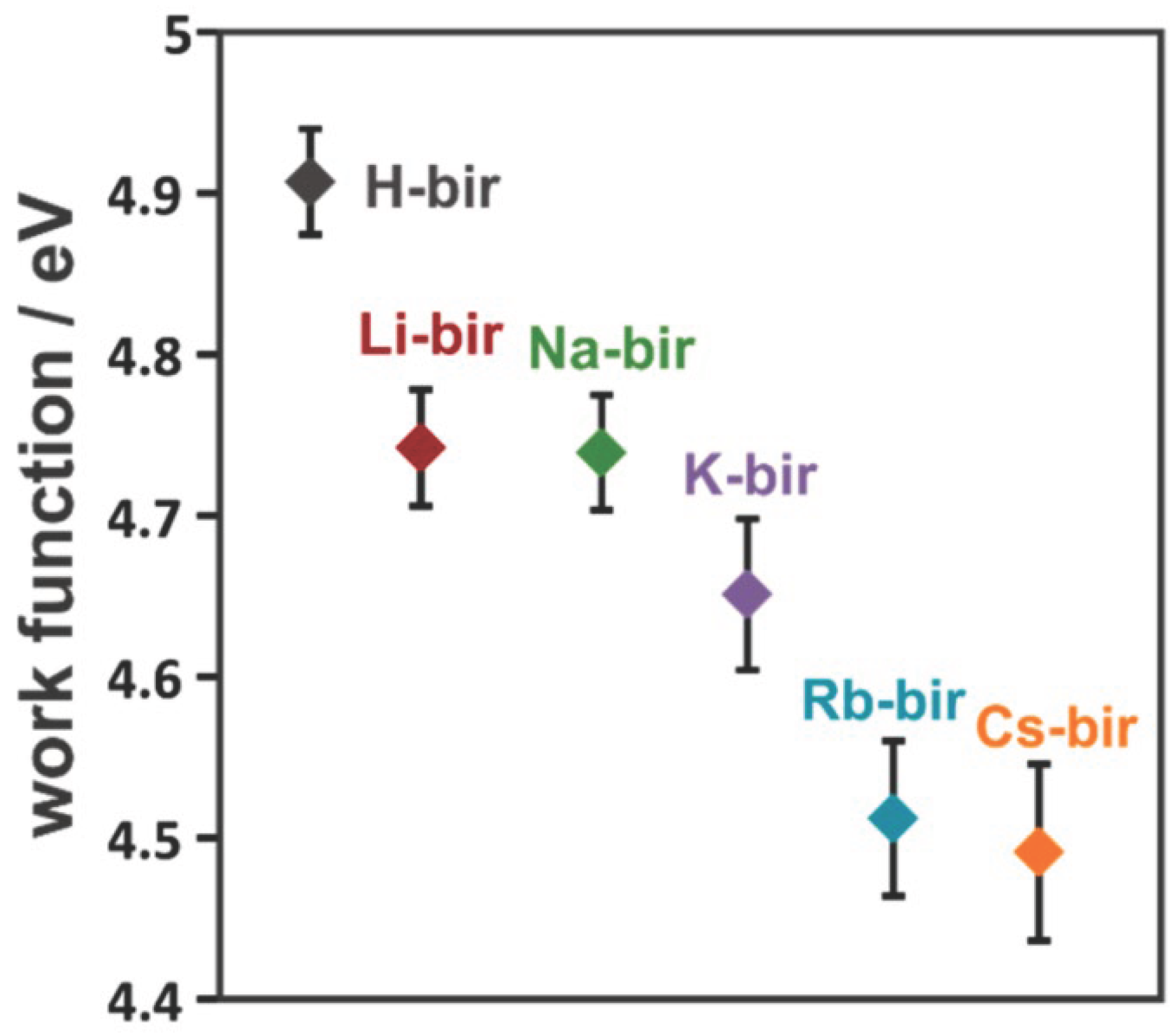

3.1. Variation of Electron Affinity Among Samples

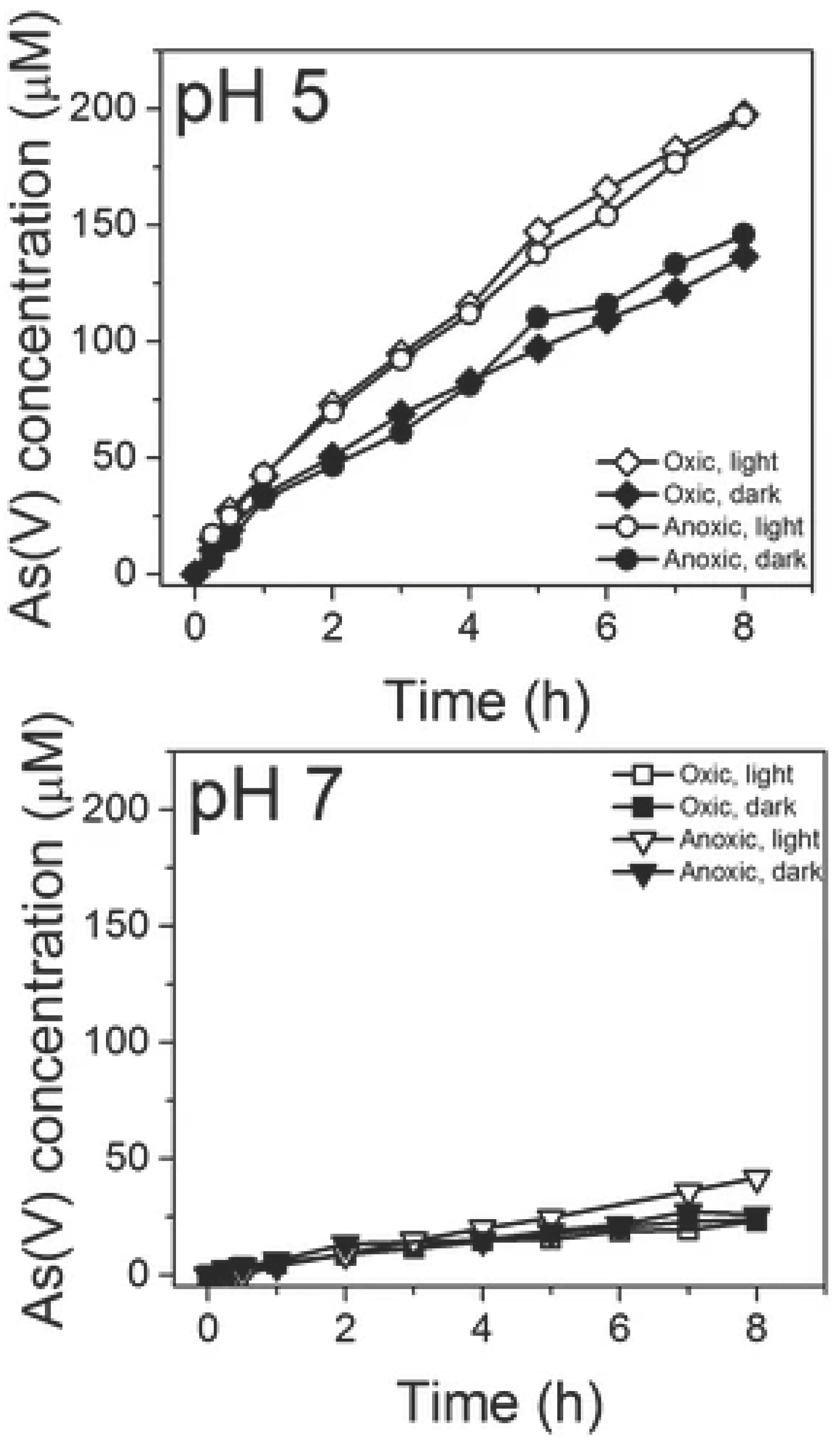

3.2. Relationship Between Electron Affinity and Oxidation Rate

3.3. Surface Changes During Reaction and Passivation Effects

3.4. Mechanistic Understanding and Implications

4. Conclusions

References

- Li, Q. , & Hausladen, D. M. (2025). Impact of organic carbon-Mn oxide interactions on colloid stability and contaminant metals in aquatic environments. Water Research, 280, 123445. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. , Li, J., Jiang, C., Zhou, P., Zhang, P., & Yu, J. (2017). The effect of manganese vacancy in birnessite-type MnO2 on room-temperature oxidation of formaldehyde in air. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, 204, 147-155. [CrossRef]

- Cai, J. , Liu, J., & Suib, S. L. (2002). Preparative parameters and framework dopant effects in the synthesis of layer-structure birnessite by air oxidation. Chemistry of Materials, 14(5), 2071-2077. [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, M. , Escobar-Quiroz, I. N., & Salazar-Camacho, C. (2014). The influence of particle size and structure on the sorption and oxidation behavior of birnessite: I. Adsorption of As (V) and oxidation of As (III). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 125, 564-581. [CrossRef]

- Boyd, S. Ganeshan, K., Tsai, W. Y., Wu, T., Saeed, S., Jiang, D. E., ... & Augustyn, V. (2021). Effects of interlayer confinement and hydration on capacitive charge storage in birnessite. Nature Materials. 20(12), 1689–1694. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C. , Smieszek, N., & Chakrapani, V. (2021). Unusually high electron affinity enables the high oxidizing power of layered birnessite. Chemistry of Materials. 33(19), 7805–7817. [CrossRef]

- Xu, K. , Xu, X., Wu, H., & Sun, R. (2024). Venturi Aeration Systems Design and Performance Evaluation in High Density Aquaculture. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C. M. , Pinto, I. S., Soares, E. V., & Soares, H. M. (2015). (Un) suitability of the use of pH buffers in biological, biochemical and environmental studies and their interaction with metal ions–a review. Rsc Advances, 5(39), 30989-31003. [CrossRef]

- Li, C. , Yuan, M., Han, Z., Faircloth, B., Anderson, J. S., King, N., & Stuart-Smith, R. (2022). Smart branching. In Hybrids and Haecceities-Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference of the Association for Computer Aided Design in Architecture, ACADIA 2022 (pp. 90-97). ACADIA.

- Najafpour, M. M. , Renger, G., Hołynska, M., Moghaddam, A. N., Aro, E. M., Carpentier, R.,... & Allakhverdiev, S. I. (2016). Manganese compounds as water-oxidizing catalysts: from the natural water-oxidizing complex to nanosized manganese oxide structures. Chemical reviews, 116(5), 2886-2936. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. , Li, S., Liang, H., Xu, P., & Yue, L. (2025). Optimization Study of Thermal Management of Domestic SiC Power Semiconductor Based on Improved Genetic Algorithm.

- Peng, H. , Dong, N., Liao, Y., Tang, Y., & Hu, X. (2024). Real-Time Turbidity Monitoring Using Machine Learning and Environmental Parameter Integration for Scalable Water Quality Management. Journal of Theory and Practice in Engineering and Technology, 1(4), 29-36.

- Wang, C. & Chakrapani, V. (2023). Environmental Factors Controlling the Electronic Properties and Oxidative Activities of Birnessite Minerals. ACS Earth and Space Chemistry. 7(4), 774–787. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, L. , Gao, B., Li, F., Liu, K., & Chi, J. (2022). The nature of metal atoms incorporated in hematite determines oxygen activation by surface-bound Fe (II) for As (III) oxidation. Water Research, 227, 119351. [CrossRef]

- Wu, C. , Zhang, F., Chen, H., & Zhu, J. (2025). Design and optimization of low power persistent logging system based on embedded Linux.

- Wiechen, M. , Zaharieva, I., Dau, H., & Kurz, P. (2012). Layered manganese oxides for water-oxidation: alkaline earth cations influence catalytic activity in a photosystem II-like fashion. Chemical Science, 3(7), 2330-2339. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).