1. Introduction

In Serbia, forest fires represent a severe ecological and economic problem. Nevertheless, in terms of forest fires, Serbia does not belong to the most threatened countries in Europe, such as Portugal, Spain, France, Italy, and Greece [

1]. Of the total area under forests in Serbia (2,252,400 ha), only 9.3% is under conifer stands [

2]. Regardless of the relatively small presence of conifer species threatened by fire, the affected wood mass can be measured in tens of thousands of m

3.

Research on the connection between climate and forest fires in Serbia in recent years was mainly based on the influence of temperature and precipitation [

3], drought [

4], humidity [

5,

6], as well as extreme climatic conditions [

7], but there is little research dealing with the influence of teleconnections. In general, the term teleconnection denotes the link between weather patterns and changes occurring in widely separated regions of the globe [

8]. El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) teleconnections are an important predictability source for extratropical seasonal climate forecasts [

9]. The link between ENSO and forest fires has been confirmed, among other regions, for Florida, USA [

10], southeast Australia [

11], Indonesia [

12], and Chile [

13]. As for other teleconnections, the Arctic Oscillation (AO) induces higher fire risk in northern Eurasia and central North America, and the Pacific-North American pattern (PNA) increases the fire danger across southern Asia and western North America [

14]. It has been determined that there is a positive correlation between the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) and national time series of extensive fires (≥10,000 ha), wildfire-related evacuations, and fire suppression expenditures in Canada (1975−2007). Still, there were also influences of AO and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation (PDO) [

15]. In Europe, the connection between AMO and forest fires has been confirmed for France [

16] and Portugal [

17]. In Finland, there is a connection between the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and forest fires [

18]. In Romania, the influence of the Mediterranean Oscillation (MO) on forest fires has been confirmed [

19].

Bearing in mind the above, the main goal of this research was to determine the impact of teleconnections on forest fires in Serbia. This type of connection has already been confirmed for some areas in Serbia. For Deliblatska peščara, a connection between AMO and the annual number of fires was determined [

20]. The results of the research on the connection between teleconnections and forest fires may find application in fire hazard prediction [

14,

21,

22].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The research covers the period 1970-2022 and refers to the territory of the Republic of Serbia without the autonomous province of Kosovo and Metohija (there are no data after 1998).

The area under forest in Serbia amounts to 2,252,400 ha (78.3% hardwood, 9.3% conifers and 2.4% mixed hardwood-conifers stands). The most common tree species are beech –

Fagus sylvatica (29.3%) and Turkey oak –

Quercus cerris (15.3%). Of the conifers, the most common are pines –

Pinus spp. (5.6%), while spruce –

Picea abies accounts for 3.8% [

2]. These data refer to the year 2007 when the forest cover in Serbia was close to 30%. According to the most recent data (2023), forest coverage reached 40% [

23]. The largest areas under forest are in the central, western, eastern, and southern parts, while in the northern lowland areas (autonomous province of Vojvodina), the forests are less represented.

2.2. Data

The data on forest fires in Serbia include the total annual burned area (ha), as well as the total annual damage to wood mass (m

3). The data source is the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia [

24].

Monthly and seasonal values of the teleconnections were used in the research. It included the values for the same year (January to August) as well as for the previous year (June to December). Following teleconnections (climate indices) were used in the research:

NAO – North Atlantic Oscillation [

25,

26];

AO – Arctic Oscillation [

27];

AMO – Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation [

28];

MOI – Mediterranean Oscillation Index [

29,

30];

EA/WR – Eastern Atlantic/Western Russia [

31];

TNA – Tropical Northern Atlantic Index [

32];

AMM – Atlantic Meridional Mode [

33].

Two different datasets were used for the NAO index. The first one, marked as NAO1, was calculated based on the difference in sea surface air pressure between the Island (low air pressure) and the Azores (high) [

34]. The other one (NAO2 or NAO Jones) is defined as the normalized pressure difference between Gibraltar and Reykjavik (Iceland) [

35].

The AMO is calculated on the basis of a natural variation in SST (sea surface tem-perature) in the northern Atlantic Ocean [

36].

There were also two datasets for MOI. The first one, MOI1 is established as the normalized pressure difference between Algiers and Cairo [

37]. The other one, MOI2, is calculated from Gibraltar's Northern Frontier and Lod Airport in Israel [

38].

2.3. Methods

Linear trends were determined for the total annual burned area (ha), as well as the total annual damage to wood mass (m

3). Statistical significance was determined for the number of elements (n−2) and the determination coefficient (R

2). In the research t-test was used:

Pearson correlation coefficient (r) was used for the calculation of the correlation between forest fire data (total annual burned area and the total annual damage to wood mass) and teleconnection indices. The statistical significance was tested on p ≤ .05 and p ≤ .01.

3. Results

In Serbia, in the period 1970-2022, forest fires covered a total area of 82,274 ha (yearly average 1,789 ha). The maximum was recorded in 2007 when 22,000 ha were burned, and the minimum was in 2005 (52 ha). A statistically non-significant increasing trend of the total annual burned area was recorded (

Figure 1).

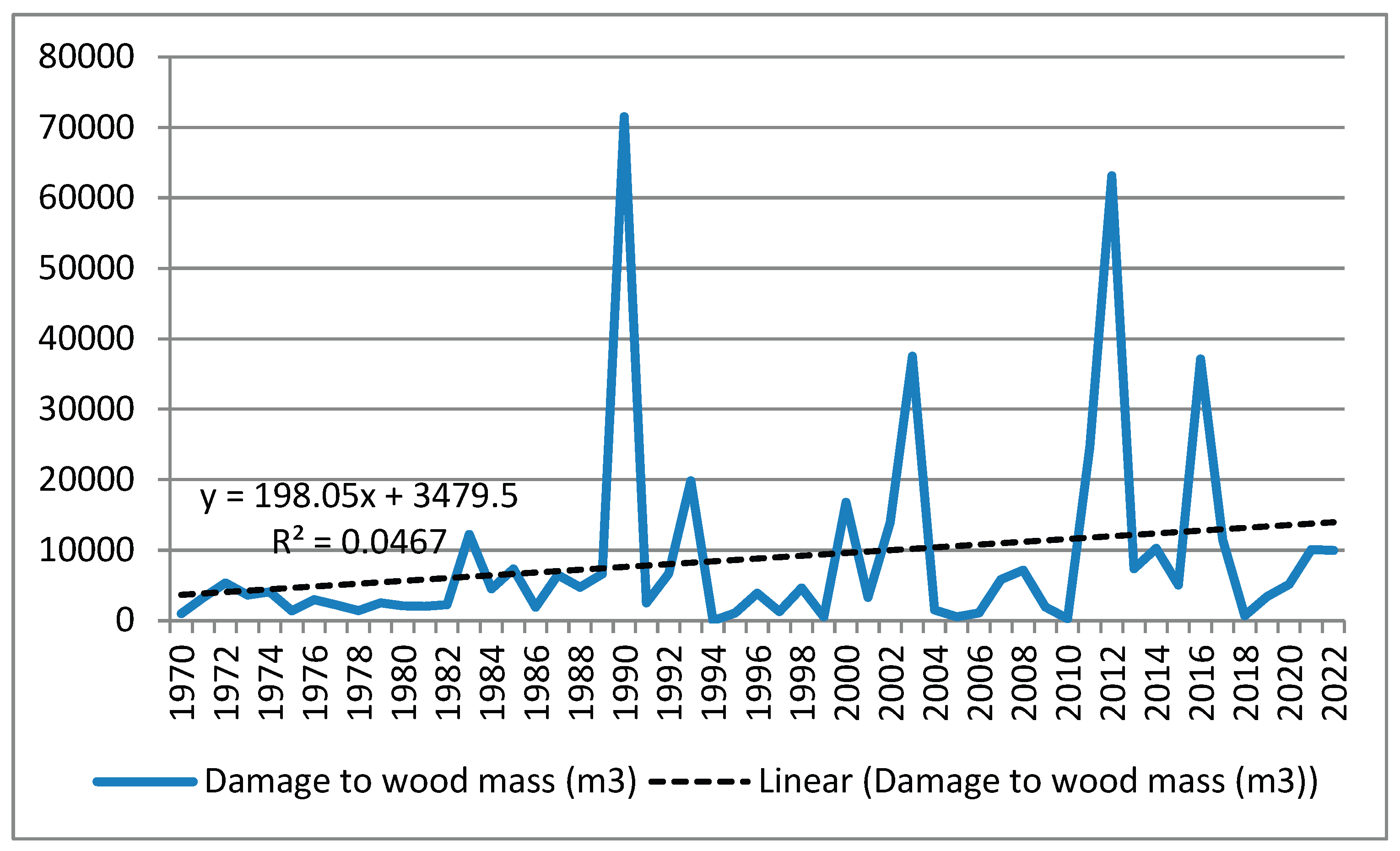

At the same time, the total damage to the wood mass amounted to 467,821 m

3 (yearly average 8,827 m

3). The maximum was recorded in 1990 (71,528 m

3), and the minimum in 2005 (528 m

3). A statistically non-significant increasing trend was also recorded (

Figure 2).

In calculating the correlation between forest fire data and climate indices, statistically significant values were recorded for NAO, AO, and MO. For other indices (AMO, EA/WR, TNA, and AMM), there were no statistically significant values.

In the case of NAO1, statistically significant values were obtained for NAO1 March and burned area (0.277, p ≤ .05), NAO1 March and damage to wood mass (0.294, p ≤ .05), and NAO1 April and damage to wood mass (0.316, p ≤ .05).

Statistically significant values were also obtained for NAO2 (NAO Jones): NAO2 summer and burned area (-0.287, p ≤ .05), NAO2 August of the previous year and burned area (-0.303, p ≤ .05), NAO2 February and damage to wood mass (0.337, p ≤ .05) and NAO2 winter and damage to wood mass (0.298, p ≤ .05).

As for AO, statistically significant values were for AO December of the previous year and burned area (0.279, p ≤ .05), AO February, and damage to wood mass (0.316, p ≤ .05), the same with AO March (0.353, p ≤ .05) and AO spring (0.378, p ≤ .01).

All obtained values for MOI1 were statistically significant for p ≤ .05: MOI1 February and damage to wood mass (0.273), the same for MOI1 March (0.292) and MOI1 August (0.279).

Statistically significant values obtained for MOI2 were: MOI2 May and burned area (0.294, p ≤ .05), the same for MOI2 June (0.274, p ≤ .05), MOI2 February and damage to wood mass (0.365, p ≤ .01), MOI2 July of the previous year and damage to wood mass (-0.344, p ≤ .05) and the same for MOI2 summer of the previous year (-0.323, p ≤ .05).

4. Discussion

The correlation coefficient values obtained in these studies were weaker than expected. It primarily refers to the calculations with AMO in which no statistically significant values were recorded (p ≤ .01, p ≤ .05). This can be explained by the fact that the research used data on the burned area and damage to the wood mass, but not data on the number of fires. In the research of forest fires in Deliblatska peščara in the period 1948-2017, statistically significant correlations with AMO were obtained for the number of fires, which was not the case with the burned area and the intensity of the fire [

20]. A significant influence of AMO on the burned area and fire intensity was determined for France [

16] and Portugal [

17], which can be explained by a strong influence of AMO on the temperature in the northern part of the Atlantic basin (Europe and North America) [

36].

In the research on the impact of the NAO (NAO1 and NAO2), all statistically significant values were for p ≤ .05 (no p ≤ .01 was recorded). Positive and negative phases characterize NAO. In southern Europe, strong positive phases of NAO are associated with below-average temperatures and below-average precipitation. Strong negative phases of NAO are typically connected with the opposite patterns [

34]. Positive and negative phases also characterize AO. Positive phases are often associated with higher temperatures and negative phases with lower temperatures [

39]. The AO spring calculations (0.378, p ≤ .01) and AO March calculations (0.353, p ≤ .05) show elevated temperatures, which pose a risk of fire.

As for MO, the highest correlation coefficient value was recorded for MOI2 February and damage to wood mass (0.365), the only case significant at p ≤ .01. This can most likely be explained by less rainfall and higher temperature, which favor the formation of a large amount of dry fuel at the end of winter and beginning of spring. This implies the absence of a snow cover under which the decay of fuel (primarily dry grass from the previous vegetation) takes place.

The results obtained could be used to forecast forest fires in Serbia. However, more detailed research would be necessary, in which other climate indices would have to be included. The joint effect of several climate indices, as well as their positive and negative phases, should be taken into account. There are correlations between individual telecommunications, e.g., NAO and AO [

40,

41], which should also be kept in mind.

Studies that show the connection between solar activity and teleconnections are of particular importance. The connection between NAO and solar activity has been confirmed in several studies [

42,

43,

44,

45]. The connection between winter NAO and AO with geomagnetic activity, solar wind, and solar proton events has also been determined [

46].

In addition, a direct link between solar activity and forest fires was established. According to this new theory, forest fires are caused by the action of high-energy solar wind particles that reach the Earth's surface under particular conditions. So far, the connection between the solar wind and forest fires has been established in Europe [

47], Serbia (Deliblatska peščara) [

48], the USA [

49,

50], Portugal [

51,

52] and an analysis was made for fires in the USA (California), Portugal and Greece [

53]. The results of the research above clearly indicate the possibilities of forest fire forecasting. In doing so, it would be necessary to take into account the influence of teleconnections, which may be important for long-term fire risk forecasting.

A more accurate and detailed database on forest fires in Serbia would provide a better basis for future research. The database used in this research only contains annual data and monthly data should be collected in the future. For each fire in Serbia, the following should be determined: the exact location (precisely defined boundaries of burned area), cause of the fire, type of fire, type of vegetation, species of trees and bushes, experience in extinguishing, engaged personnel, and equipment, etc. There is a need for a central register of forest fires that should be available for scientific research. Basic terms should also be defined more precisely. The term "forest fires", used in this article, means fire in areas managed by forestry organizations (including national parks). Areas affected by grass vegetation fires, on the one hand, and tree and bush fires, on the other, should be clearly separated. The term "damage to wood mass" should also be more clearly defined, since much of wood can be used after fire.

5. Conclusions

In Serbia, from 1970 to 2022, forest fires covered an average of 1,789 ha per year, while the average annual damage to wood mass amounted to 8,827 m3. In both cases, the trends are increasing, but they are not statistically significant.

In the calculation of the correlation with forest fire data, statistically significant val-ues (p ≤ .05 and p ≤ .01) of Pearson correlation coefficient (r) were recorded for NAO, AO, and MO. For AMO, EA/WR, TNA, and AMM, there were no statistically significant values.

In the case of NAO1 (on the basis of the difference in sea surface air pressure between Island - low air pressure and the Azores - high), the highest correlation was obtained for NAO1 April and damage to wood mass (0.316, p ≤ .05). As for NAO2 (NAO Jones - the normalized pressure difference between Gibraltar and Reykjavik), the highest value was for NAO2 February and damage to wood mass (0.337, p ≤ .05).

In the calculation with AO, the highest values were also for damage to wood mass: AO March (0.353, p ≤ .05) and AO spring (0.378, p ≤ .01).

The results for MO were better with MOI2 (Gibraltar's Northern Frontier and Lod Airport in Israel) than with MOI1 (Algiers and Cairo). The important value was for MOI2 February and damage to wood mass (0.365, p ≤ .01).

The obtained results are weaker than expected, but further and more detailed re-search is necessary to assess the possibilities of using teleconnections in forest fire fore-casting in Serbia.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D. and M.M.; methodology, A.D. and M.M.; software, S.S.; validation, A.D., M.M. and V.B.; formal analysis, M.M. and S.D.; investigation, M.M. and S.D.; resources, S.D. and S.S.; data curation, S.D. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D., M.M. and V.B.; writing—review and editing, A.D., M.M. and V.B.; visualization, S.D.; supervision, A.D.; project administration, S.D. and S.S.; funding acquisition, S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia, grant numbers 451-03-65/2024-03/200169 and 451-03-66/2024-03/200172.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Boško Krstović and Velibor Lazarević from the Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia for providing us with data and information on forest fires.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AMM |

Atlantic Meridional Mode |

| AMO |

Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation |

| AO |

Arctic Oscillation |

| EA/WR |

Eastern Atlantic/Western Russia |

| ENSO |

El Niño-Southern Oscillation |

| MO |

Mediterranean Oscillation |

| MOI |

Mediterranean Oscillation Index |

| MOI1 |

MOI - normalized pressure difference between Algiers and Cairo |

| MOI2 |

MOI - Gibraltar's Northern Frontier and Lod Airport in Israel |

| NAO |

North Atlantic Oscillation |

| NAO1 |

NAO Index based on the difference in sea surface air pressure the Island and the Azores |

| NAO2 |

NAO Index - normalized pressure difference between Gibraltar and Reykjavik |

| PDO |

Pacific Decadal Oscillation |

| PNA |

Pacific-North American pattern |

References

- San-Miguel-Ayanz, J.; Durrant, T.; Boca, R.; Maianti, P.; Liberta, G.; Jacome Felix Oom, D.; Branco, A.; De Rigo, D.; Suarez-Moreno, M.; Ferrari, D.; Roglia, E.; Scionti, N.; Broglia, M.; Onida, M.; Tistan, A.; Loffler, P. Forest Fires in Europe, Middle East and North Africa 2022; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg City, Luxembourg, 2023; JRC135226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Forestry in the Republic of Serbia. 2022. Available online: https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2023/PdfE/G20235697.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2024).

- Živanović, S.; Ivanović, R.; Nikolić, M.; Đokić, M.; Tošić, I. Influence of air temperature and precipitation on the risk of forest fires in Serbia. Meteorol. Atmos. Phys. 2020, 132, 869–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živanović, S. Impact of drought in Serbia on fire vulnerability of forests. Int. J. Bioautomation 2017, 21, 217–226, https://biomed.bas.bg/bioautomation/2017/vol_21.2/files/21.2_06.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Živanović, S. Influence of forest humidity on the distribution of forest fires in the territory of Serbia. Disaster Adv. 2021, 14, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Živanović, S.; Gocić, M. Forest fires in Serbia—influence of humidity conditions. J. Geogr. Inst. Jovan Cvijić SASA 2022, 72, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tošić, I.; Živanović, S.; Tošić, M. Influence of extreme climate conditions on the forest fire risk in the Timočka Krajina region (Northeastern Serbia). Idojaras 2020, 124, 331–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earth Data. Available online: https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/topics/climate-indicators/atmospheric-ocean-indicators/teleconnections (accessed on 5 Septmber 2024).

- Beniche, M.; Vialard, J.; Lengaigne, M.; Voldoire, A.; Srinivas, G.; Hall, N.M.J. A distinct and reproducible teleconnection pattern over North America during extreme El Niño events. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M. Understanding and visualizing and ENSO-based fire climatology in Florida, USA: A case method using cluster analysis. Southeast. Geogr. 2013, 53, 381–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, M.; Fletcher, M.-S.; Holz, A.; Nyman, P. ENSO controls interannual fire activity in southeast Australia. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 10891–10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurdiati, S.; Bukhari, F.; Julianto, M.T.; Sopaheluwakan, A.; Aprilia, M.; Fajar, I.; Septiawan, P.; Najib, M.K. The impact of El Niño southern oscillation and Indian Ocean Dipole on the burned area in Indonesia. TAO 2022, 33, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero, R.R.; Feron, S.; Damiani, A.; Carrasco, J.; Karas, C.; Wang, C.; Kraamwinkel, C.T.; Beaulieu, A. Extreme fire weather in Chile driven by climate change and El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Justino, F.; Bromwich, D.H.; Schumacher, V.; daSilva, A.; Wang, S.-H. Arctic Oscillation and Pacific-North American pattern dominated-modulation of fire danger and wildfire occurrence. npj. Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beverly, J.L.; Flannigan, M.D.; Stocks, B.J.; Bothwell, P. The association between Northern Hemisphere climate patterns and interannual variability in Canadian wildfire activity. Can. J. For. Res. 2011, 41, 2193–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, M.; Ducić, V.; Burić, D.; Lazić, B. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) and the forest fires in France in the period 1980–2014. J. Geogr. Inst. “Jovan Cvijić” SASA 2016, 66, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, M.; Yamashkin, A.; Ducić, V.; Babić, V.; Govedar, Z. Forest fires in Portugal — the connection with the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO). J. Geogr. Inst. “Jovan Cvijić” SASA 2017, 67, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, M.; Ducić, V.; Mihajlović, J.; Burić, D.; Babić, V. Forest fires in Finland – the influence of atmospheric oscillations. J. Geogr. Inst. "Jovan Cvijic" SASA 2019, 69, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, M.; Ducić, V.; Babić, V. The Mediterranean Oscillation (MOI) and the Forest Fires in Romania in the Period 1986–2014. Forum Geogr. 2016, 15, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, M.; Ducić, V.; Obradović, D.; Dedić, A.; Burić, D. Climatic and anthropogenic impacts on forest fires in conditions of extreme fire danger on sandy soils. J. Geogr. Inst. “Jovan Cvijić” SASA 2023, 73, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, S.; Nicholls, N.; Tapper, N. Forecasting fire activity in Victoria, Australia, using antecedent climate variables and ENSO indices. Int. J. Wildland Fire 2014, 23, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; van Kooten, G.C. The El Niño Southern Oscillation index and wildfire prediction in British Columbia. For. Chron. 2014, 90, 592–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Serbia, Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management. Available online: http://www.minpolj.gov.rs/sumovitost-srbije-dostigla-40-odsto/?script=lat (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Available online: https://www.stat.gov.rs/sr-cyrl/oblasti/poljoprivreda-sumarstvo-i-ribarstvo/sumarstvo/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Physical Sciences Laboratory. Available online: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/correlation/nao.data (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Physical Sciences Laboratory. Available online: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/correlation/jonesnao.data (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Physical Sciences Laboratory. Available online: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/correlation/ao.data (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Physical Sciences Laboratory. Available online: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/correlation/amon.us.data (accessed on 3 September 2024).

- University of East Anglia. Available online: https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/moi/moi1.output.dat (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- University of East Anglia. Available online: https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/moi/moi2.output.dat (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Physical Sciences Laboratory. Available online: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/correlation/ea.data (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Physical Sciences Laboratory. Available online: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/correlation/tna.data (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Physical Sciences Laboratory. Available online: https://psl.noaa.gov/data/timeseries/monthly/AMM/ammsst.data (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- National Weather Service, Climate Prediction Center. Available online: https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/data/teledoc/nao.shtml (accessed on 4 September 2024).

- Jones, P.D.; Jonsson, T.; Wheeler, D. Extension to the North Atlantic Oscillation Using Early Instrumental Pressure Observations from Gibraltar and South-West Iceland. Int. J. Climatol. 1997, 17, 1433–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lee, S.-K.; Enfield, D.B. Atlantic Warm Pool acting as a link between Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation and Atlantic tropical cyclone activity. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2008, 9, Q05V03. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.; Giuffrida, A.; Tedesco, S. The Mediterranean Oscillation, impact on precipitation and hydrology in Italy. In Proceedings of the Conference on Climate, Water; Academy of Finland: Helsinki, Finland, 1989; pp. 121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Palutikof, J.P. Analysis of Mediterranean climate data: measured and modelled. In Mediterranean climate: Variability and trends; Bolle, H.J., Ed.; Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2003; pp. 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Available online: https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-variability-arctic-oscillation (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Ambaum, M.H.P.; Hoskins, B.J.; Stephenson, D.B. Arctic Oscillation or North Atlantic Oscillation? J. Climate 2001, 14, 3495–3507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Derome, J.; Greatbatch, R.J.; Peterson, K.A.; Lu, Ji. Tropical links of the Arctic Oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2002, 29, 4.1–4.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boberg, F.; Lundstedt, H. Solar wind variations related to fluctuations of the North Atlantic Oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2002, 29, 13.1–13.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boberg, F.; Lundstedt, H. Solar wind electric field modulation of the NAO: A correlation analysis in the lower atmosphere. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2003, 30, 8.1–8.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukianova, R.; Alekseev, G. Long-term correlation between the NAO and solar activity. Sol. Phys. 2004, 224, 445–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahab, M.A.; Shaltoot, M.M.; Youssef, S.; Hussein, M.M. Interrelationship between the North Atlantic Oscillation and Solar cycle. Int. J. of Adv. Res. 2016, 4, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Vencloviene, J.; Kiznys, D.; Zaltauskaite, J. Statistical associations between geomagnetic activity, solar wind, solar proton events, and winter NAO and AO indices. Earth Space Sci. 2022, 9, e2021EA002179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, M. Forest fires in Europe from July 22-25, 2009. Arch. Biol. Sci. 2010, 62, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenković, M.; Radovanović, M.; Ducić, V. The impact of solar activity on the greatest forest fires of Deliblatska peščara (Serbia). Forum Geogr. 2011, 10, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, M.; Vyklyuk, Y.; Jovanović, A.; Vuković, D.; Milenković, M.; Stevančević, M.; Matsiuk, N. Examination of the correlations between forest fires and solar activity using Hurst index. J. Geogr. Institute “Jovan Cvijić” SASA 2013, 63, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, M.M.; Vyklyuk, Y.; Milenković, M.; Vuković, D.B.; Matsiuk, N. Application of adaptive neuro-fuzzy interference system models for prediction of forest fires in the USA on the basis of solar activity. Therm. Sci. 2015, 19, 1649–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, M.; Pereira Gomes, J.F.; Yamashkin, A.A.; Milenković, M.; Stevančević, M. Electrons or protons: What is the cause of forest fires in Western Europe on June 18, 2017? J. Geogr. Inst. “Jovan Cvijić” SASA 2017, 67, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radovanović, M.M.; Vyklyuk, Y.; Stevančević, M.T.; Milenković, M.Đ.; Jakovljević, D.M.; Petrović, M.D.; Malinović-Milićević, S.B.; Vuković, N.; Vujko, A.Đ.; Yamashkin, A.; Sydor, P.; Vuković, D.B.; Škoda, M. Forest fires in Portugal - case study, 18 June 2017. Therm. Sci. 2019, 23, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyklyuk, Y.; Radovanović, M.M.; Stanojević, G.; Petrović, M.D.; Ćurčić, N.B.; Milenković, M.; Malinović Milićević, S.; Milovanović, B.; Yamashkin, A.A.; Milanović Pešić, A.; Lukić, D.; Gajić, M. Connection of solar activities and forest fires in 2018: Events in the USA (California), Portugal and Greece. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).