Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Growth Function

3. FSFS and SFS as Dynamical Dark Energy Candidates

4. Data and Methodology

4.1. Fiducial Cosmological Background

4.2. Compilation of Current Measurements

4.3. Geometrical Rescaling and Definition

5. Results and Conclusions

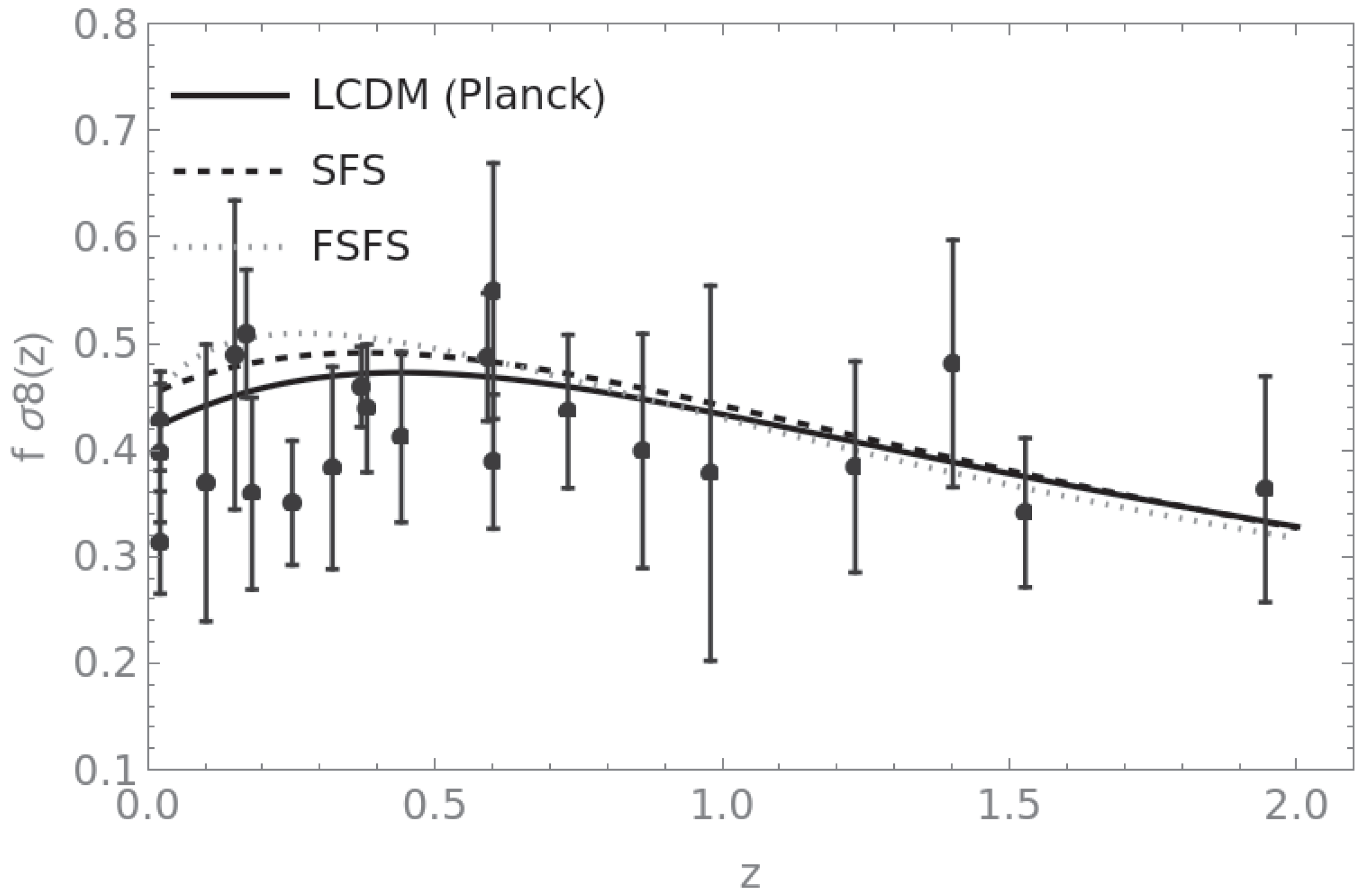

- (i)

- For the particular fixed parameter sets considered in this work, the SFS and FSFS benchmarks are disfavoured to different degrees with respect to the Planck-2018–calibrated CDM reference model once model complexity is taken into account.

- (ii)

- The FSFS benchmark considered here yelds a poorer fit to the data than PlanckCDM and is disfavoured by the information criteria, but it is not decisively ruled out by growth measurements.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDM | Lambda Cold Dark Matter |

| SFS | Sudden Future Singularity |

| FSFS | Finite Scale Factor Singularity |

| DESI | Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument |

| CMB | Cosmic Microwave Background |

| BAO | Baryon Acoustic Oscillations |

| SNeIa | Type Ia Supernovae |

| LSS | Large-Scale Structure |

References

- Riess, A.G.; et al. Observational Evidence from Supernovae for an Accelerating Universe and a Cosmological Constant. AJ 1998, 116, 1009–1038, [astro-ph/9805201]. [CrossRef]

- Perlmutter, S.; et al. Measurements of Ω and Λ from 42 High-Redshift Supernovae. APJ 1999, 517, 565–586, [astro-ph/9812133]. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, N.; et al. The Hubble Space Telescope Cluster Supernova Survey: V. Improving the Dark Energy Constraints Above z>1 and Building an Early-Type-Hosted Supernova Sample. Astrophys. J. 2012, 746, 85, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1105.3470]. [CrossRef]

- Betoule, M.; et al. Improved Photometric Calibration of the SNLS and the SDSS Supernova Surveys. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 552, A124, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1212.4864]. [CrossRef]

- Eisenstein, D.J.; et al. Detection of the Baryon Acoustic Peak in the Large-Scale Correlation Function of SDSS Luminous Red Galaxies. APJ 2005, 633, 560–574, [astro-ph/0501171]. [CrossRef]

- Bassett, B.A.; Hlozek, R. Baryon Acoustic Oscillations. arxiv 2009, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/0910.5224].

- Alam, S.; Ata, M.; Bailey, S.; Beutler, F.; Bizyaev, D.; Blazek, J.A.; Bolton, A.S.; Brownstein, J.R.; Burden, A.; Chuang, C.H.; et al. The clustering of galaxies in the completed SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: cosmological analysis of the DR12 galaxy sample. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2017, 470, 2617–2652. [CrossRef]

- Aghanim, N.; et al. Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1807.06209]. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; et al. The Completed SDSS-IV extended Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: Cosmological Implications from two Decades of Spectroscopic Surveys at the Apache Point observatory 2020. [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2007.08991].

- Bond, J.R.; Efstathiou, G.; Tegmark, M. Forecasting Cosmic Parameter Errors from Microwave Background Anisotropy Experiments. Mon.Not.Roy.Astron.Soc.291:L33-L41,1997 1997, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/9702100v2].

- Wang, Y.; Mukherjee, P. Observational Constraints on Dark Energy and Cosmic Curvature. Phys. Rev. 2007, D76, 103533, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0703780]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dai, M. Exploring uncertainties in dark energy constraints using current observational data with Planck 2015 distance priors. Phys. Rev. 2016, D94, 083521, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1509.02198]. [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, D.H.; Mortonson, M.J.; Eisenstein, D.J.; Hirata, C.; Riess, A.G.; Rozo, E. Observational Probes of Cosmic Acceleration. Phys. Rept. 2013, 530, 87–255, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1201.2434]. [CrossRef]

- Salzano, V.; Rodney, S.A.; Sendra, I.; Lazkoz, R.; Riess, A.G.; Postman, M.; Broadhurst, T.; Coe, D. Improving Dark Energy Constraints with High Redshift Type Ia Supernovae from CANDELS and CLASH. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 557, A64, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1307.0820]. [CrossRef]

- Lazkoz, R.; Alcaniz, J.; Escamilla-Rivera, C.; Salzano, V.; Sendra, I. BAO cosmography. JCAP 2013, 1312, 005, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1311.6817]. [CrossRef]

- Ade, P.A.R.; et al. Planck 2015 results. XIII. Cosmological parameters. arxiv 2015, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1502.01589].

- Alam, S.; Ho, S.; Silvestri, A. Testing deviations from LCDM with growth rate measurements from six large-scale structure surveys at z = 0.06–1. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2016, 456, 3743–3756, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1509.05034]. [CrossRef]

- Albarran, I.; Bouhmadi-López, M.; Morais, J. Cosmological perturbations in an effective and genuinely phantom dark energy Universe. Physics of the Dark Universe 2017, 16, 94–108. [CrossRef]

- Sagredo, B.; Nesseris, S.; Sapone, D. Internal robustness of growth rate data. Physical Review D 2018, 98, 083543. [CrossRef]

- Nesseris, S.; Pantazis, G.; Perivolaropoulos, L. Tension and constraints on modified gravity parametrizations of Geff(z) from growth rate and Planck data. Physical Review D 2017, 96, 023542. [CrossRef]

- Tsujikawa, S.; Gannouji, R.; Moraes, B.; Polarski, D. The dispersion of growth of matter perturbations in f(R) gravity. Phys.Rev.D80:084044,2009 2009, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/0908.2669v1]. [CrossRef]

- Gannouji, R.; Moraes, B.; Polarski, D. The growth of matter perturbations in f(R) models. JCAP 0902:034,2009 2009, [arXiv:astro-ph/0809.3374v2]. [CrossRef]

- Linder, E.V.; Cahn, R.N. Parameterized Beyond-Einstein Growth. Astropart.Phys.28:481-488,2007 2007, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0701317v2]. [CrossRef]

- Bamba, K.; Lopez-Revelles, A.; Myrzakulov, R.; Odintsov, S.D.; Sebastiani, L. Cosmic history of viable exponential gravity: Equation of state oscillations and growth index from inflation to dark energy era. Class. Quant. Grav. 2013, 30, 015008, [arXiv:gr-qc/1207.1009]. [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D. Sudden future singularities. Class. Quant. Grav. 2004, 21, L79–L82, [arXiv:gr-qc/gr-qc/0403084]. [CrossRef]

- Barrow, J.D.; Tsagas, C.G. Structure and stability of the Lukash plane-wave spacetime. Class. Quant. Grav. 2005, 22, 825–840, [arXiv:gr-qc/gr-qc/0411070]. [CrossRef]

- Dabrowski, M.P. Inhomogenized sudden future singularities. Phys. Rev. 2005, D71, 103505, [arXiv:gr-qc/gr-qc/0410033]. [CrossRef]

- Nojiri, S.; Odintsov, S.D. Inhomogeneous equation of state of the universe: Phantom era, future singularity and crossing the phantom barrier . Phys.Rev. D72 (2005) 023003 2005, D72, 023003, [arXiv:hep-th/hep-th/0505215]. [CrossRef]

- Da̧browski, M.P.; Denkiewicz, T. Exotic-singularity-driven dark energy, 2009, [arXiv:gr-qc/0910.0023v1].

- Da̧browski, M.P.; Denkiewicz, T. Barotropic index w-singularities in cosmology. Phys. Rev. D 79, 063521 (2009) 2009, [arXiv:gr-qc/0902.3107v3]. [CrossRef]

- Levi, M.; et al. The DESI Experiment, a whitepaper for Snowmass 2013. arxiv 2013, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1308.0847].

- Cimatti, A.; Laureijs, R.; Leibundgut, B.; Lilly, S.; Nichol, R.; Refregier, A.; Rosati, P.; Steinmetz, M.; Thatte, N.; Valentijn, E. Euclid Assessment Study Report for the ESA Cosmic Visions. arxiv 2009, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/0912.0914].

- Refregier, A.; Amara, A.; Kitching, T.D.; Rassat, A.; Scaramella, R.; Weller, J. Euclid Imaging Consortium Science Book. arxiv 2010, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/1001.0061].

- Laureijs, R.; et al. Euclid Definition Study Report. arxiv 2011, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1110.3193].

- Amendola, L.; et al. Cosmology and Fundamental Physics with the Euclid Satellite. arxiv 2016, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1606.00180].

- Collaboration, P.; Andre, P.; et al. PRISM (Polarized Radiation Imaging and Spectroscopy Mission): A White Paper on the Ultimate Polarimetric Spectro-Imaging of the Microwave and Far-Infrared Sky, 2013, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1306.2259v1].

- Collaboration, T.C.; Armitage-Caplan, C.; et al. COrE (Cosmic Origins Explorer) A White Paper, 2011, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1102.2181v2].

- Errard, J.; Feeney, S.M.; Peiris, H.V.; Jaffe, A.H. Robust forecasts on fundamental physics from the foreground-obscured, gravitationally-lensed CMB polarization. JCAP 2016, 1603, 052, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1509.06770]. [CrossRef]

- Valentino, E.D.; Brinckmann, T.; Gerbino, M.; Poulin, V.; Bouchet, F.; Lesgourgues, J.; Melchiorri, A.; Chluba, J.; Clesse, S.; Delabrouille, J.; et al. Exploring cosmic origins with CORE: Cosmological parameters. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2018, 2018, 017–017. [CrossRef]

- Adame, A.; Others. DESI 2024 VI: Cosmological Constraints from the Measurements of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations. journal = "JCAP 2024. [CrossRef]

- Adame, A.G.; et al. DESI 2024 V: Full-Shape Galaxy Clustering from Galaxies and Quasars. JCAP 2025, 2025, 008, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2411.12021]. [CrossRef]

- Adame, A.G.; et al. DESI 2024 VII: Cosmological Constraints from the Full-Shape Modeling of Clustering Measurements. JCAP 2025, 2025, 028, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2411.12022]. [CrossRef]

- Atek, H.; et al. Euclid: Early Release Observations – A preview of the Euclid era through a galaxy cluster magnifying lens. Astronomy and Astrophysics 2025, 697, A15. [CrossRef]

- Aussel, H.; et al. Euclid Quick Data Release (Q1) – Data release overview. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/2503.15302]. in press.

- Quilley, L.; et al. Euclid Quick Data Release (Q1). Exploring galaxy morphology across cosmic time through S’ersic fits. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/2503.15309]. in press.

- Euclid Quick Release Q1. ESA Euclid mission data release, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Denkiewicz, T.; Salzano, V. Testing scale-dependent perturbations in ΛCDM with future galaxy surveys. Physics of the Dark Universe 2019, 25, 100319. [CrossRef]

- Dent, J.B.; Dutta, S. On the dangers of using the growth equation on large scales in the Newtonian gauge, 2009, [arXiv:astro-ph/0808.2689v4]. [CrossRef]

- Dent, J.B.; Dutta, S.; Perivolaropoulos, L. New Parametrization for the Scale Dependent Growth Function in General Relativity. Phys.Rev.D80:023514,2009 2009, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/0903.5296v2]. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Steinhardt, P.J. Cluster Abundance Constraints on Quintessence Models. Astrophys.J.508:483-490,1998 1998, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/9804015v1]. [CrossRef]

- Linder, E.V. Cosmic Growth History and Expansion History. Phys.Rev.D72:043529,2005 2005, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0507263v2]. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, A.; Blake, C.; Dossett, J.; Koda, J.; Parkinson, D.; Joudaki, S. Searching for Modified Gravity: Scale and Redshift Dependent Constraints from Galaxy Peculiar Velocities. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2016, 458, 2725–2744, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1504.06885]. [CrossRef]

- Perivolaropoulos, L. Consistency of LCDM with Geometric and Dynamical Probes, 2010, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1002.3030v1]. [CrossRef]

- Ishak, M.; Dossett, J. Contiguous redshift parameterizations of the growth index. Phys.Rev.D80:043004,2009 2009, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/0905.2470v2]. [CrossRef]

- Gannouji, R.; Polarski, D. The growth of matter perturbations in some scalar-tensor DE models. JCAP 0805:018,2008 2008, [arXiv:astro-ph/0802.4196v4]. [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y. Growth factor parametrization and modified gravity. Phys.Rev.D78:123010,2008 2008, [arXiv:astro-ph/0808.1316v2]. [CrossRef]

- Denkiewicz, T. Dark energy and dark matter perturbations in singular universes. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics 2015, 37, 037, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1411.6169v2]. [CrossRef]

- Abramo, L.R.; Batista, R.C.; Liberato, L.; Rosenfeld, R. Physical approximations for the nonlinear evolution of perturbations in dark energy scenarios. Phys.Rev.D79:023516,2009 2008, [arXiv:astro-ph/0806.3461v1]. [CrossRef]

- Sapone, D.; Kunz, M. Fingerprinting dark energy. Phys.Rev.D80:083519,2009 2009, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/0909.0007v2]. [CrossRef]

- Batista, R.C.; Pace, F. Structure formation in inhomogeneous Early Dark Energy models. JCAP 1306 (2013) 044 2014, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1303.0414v2]. [CrossRef]

- Da̧browski, M.P.; Denkiewicz, T.; Hendry, M.A. How far is it to a sudden future singularity of pressure? Phys.Rev.D75:123524,2007 2007, [arXiv:astro-ph/0704.1383v2]. [CrossRef]

- Da̧browski, M.P.; Denkiewicz, T.; Martins, C.J.A.P.; Vielzeuf, P.E. Variations of the fine-structure constant α in exotic singularity models. Phys. Rev. D 89, 123512 (2014) 2014, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1406.1007v1].

- Beutler, F.; Saito, S.; Seo, H.J.; Brinkmann, J.; Dawson, K.S.; Eisenstein, D.J.; Font-Ribera, A.; Ho, S.; McBride, C.K.; Montesano, F.; et al. The clustering of galaxies in the SDSS-III Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey: Testing gravity with redshift-space distortions using the power spectrum multipoles. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2014, 443, 1065–1089, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1312.4611]. [CrossRef]

- Denkiewicz, T. Observational constraints on finite scale factor singularities, 2012, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1112.5447v3]. [CrossRef]

- Denkiewicz, T.; Da̧browski, M.P.; Ghodsi, H.; Hendry, M.A. Cosmological tests of sudden future singularities. Phys.Rev.D85:083527,2012 2013, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1201.6661v3]. [CrossRef]

- Denkiewicz, T.; Da̧browski, M.P.; Martins, C.J.A.P.; Vielzeuf, P. Redshift drift test of exotic singularity universes. Phys. Rev. D 89, 083514 (2014) 2014, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1402.0520v2]. [CrossRef]

- Ghodsi, H.; Hendry, M.A.; Da̧browski, M.P.; Denkiewicz, T. Sudden Future Singularity models as an alternative to Dark Energy?, 2011, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1101.3984v4]. [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | In practice, the fiducial cosmology for each data point may include additional parameters beyond , but the dominant effect on the RSD observable is captured by the simple geometrical rescaling described below. |

| 5 |

| h | w | r | |||||||||||

| 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).