Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

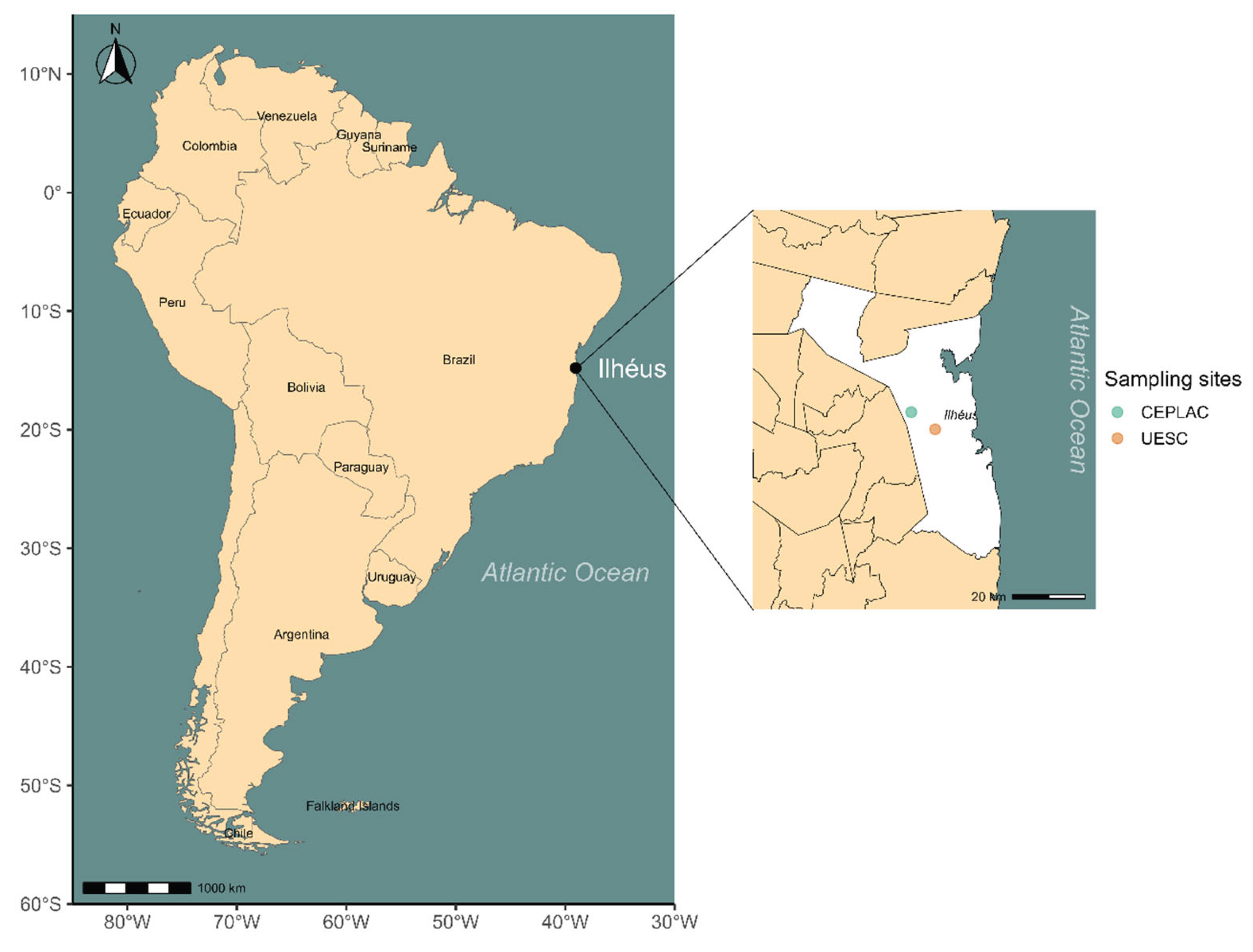

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Experimental Design

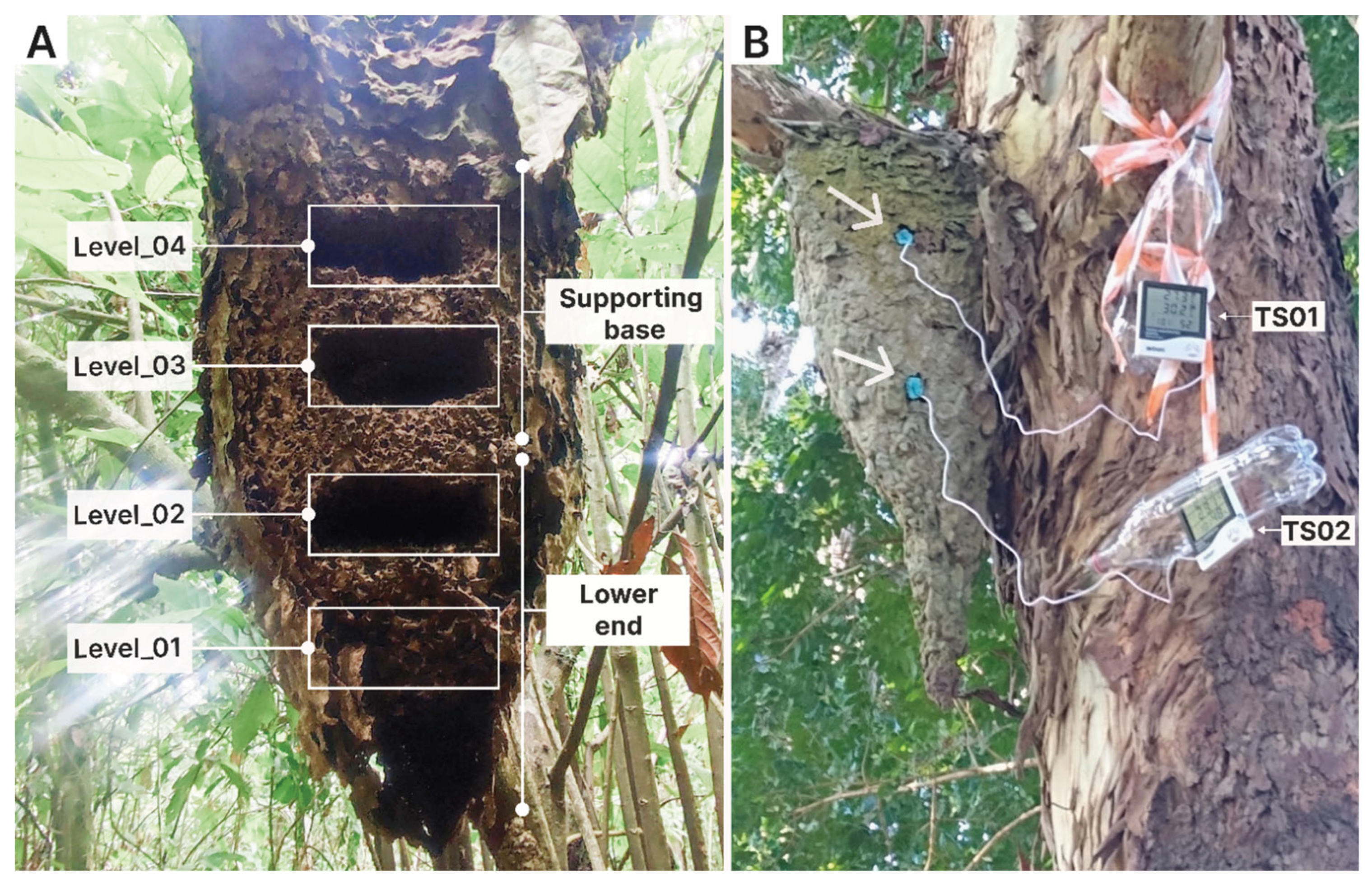

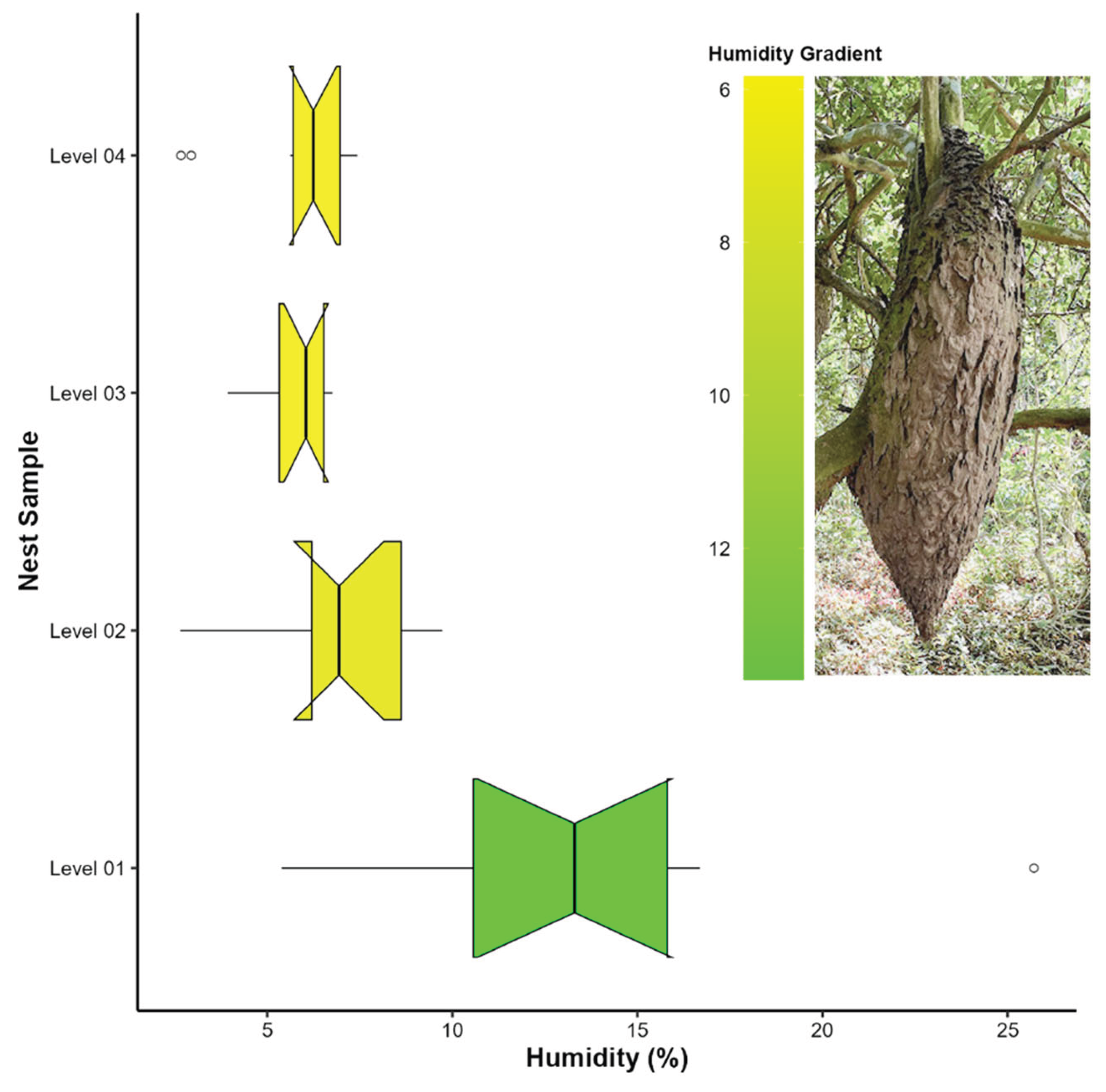

2.2.1. Phase I: Internal Nest Humidity Patterns

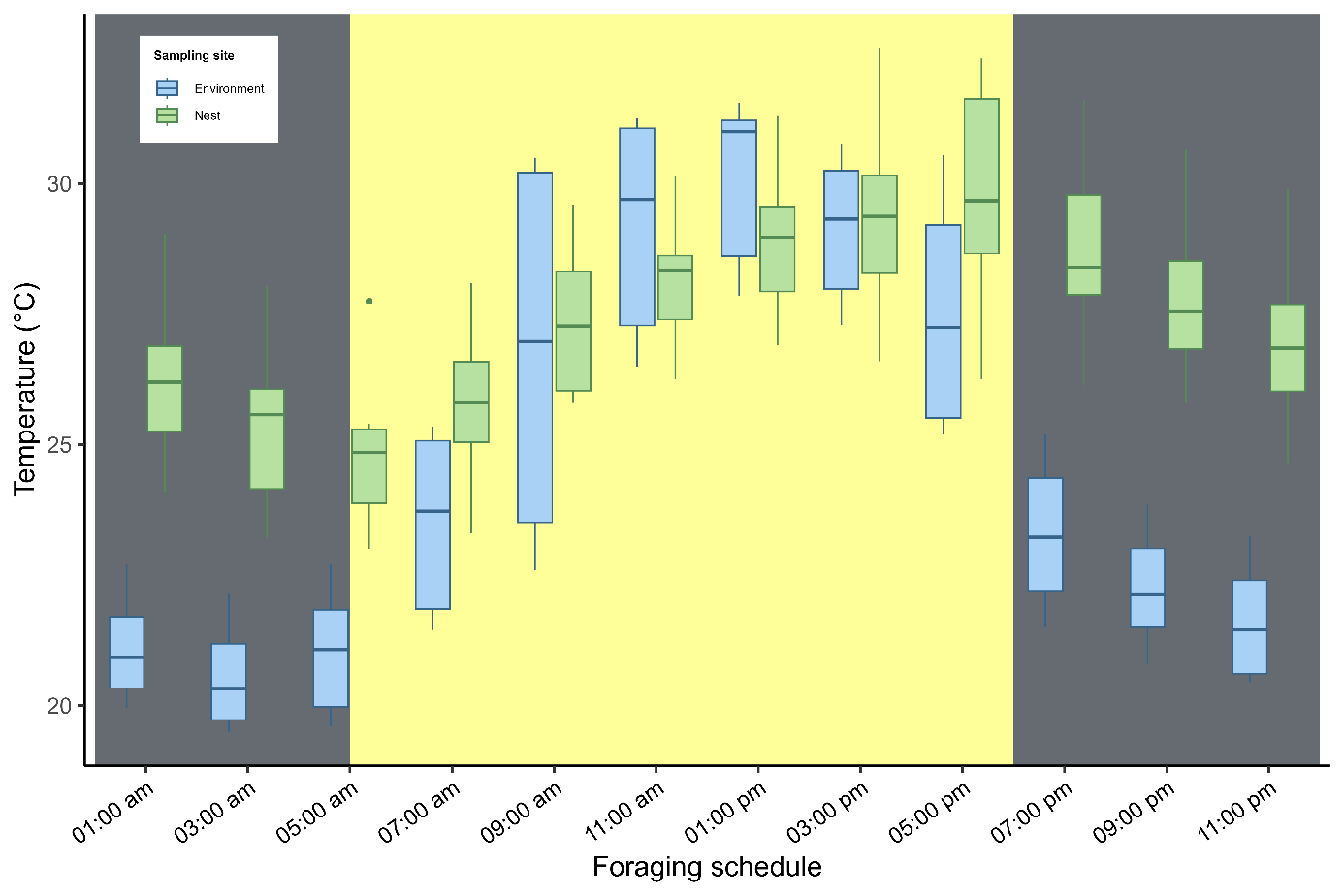

2.2.2. Phase II: Thermal Ecology and Worker Morphometry

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Phase I: Internal Nest Humidity Patterns

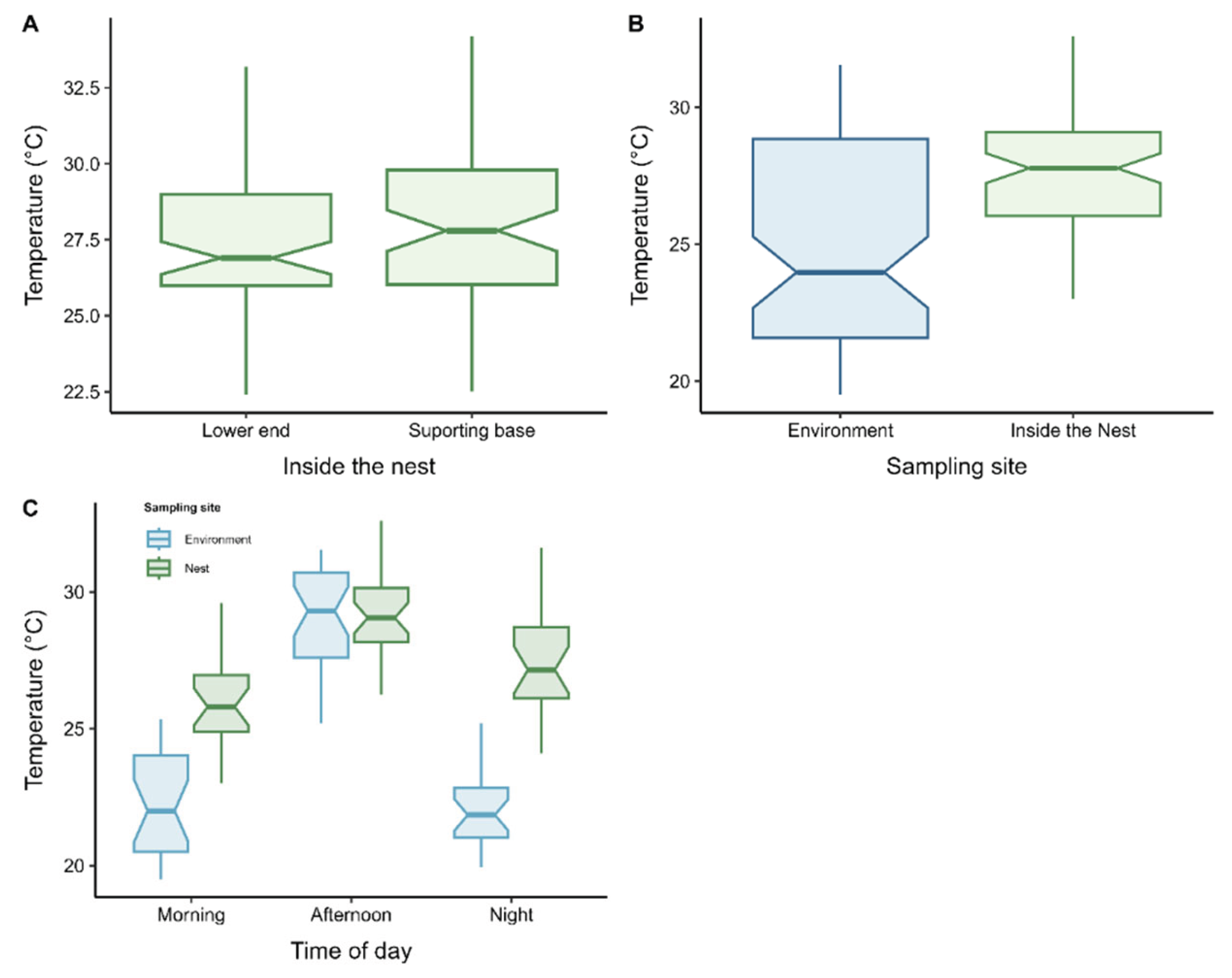

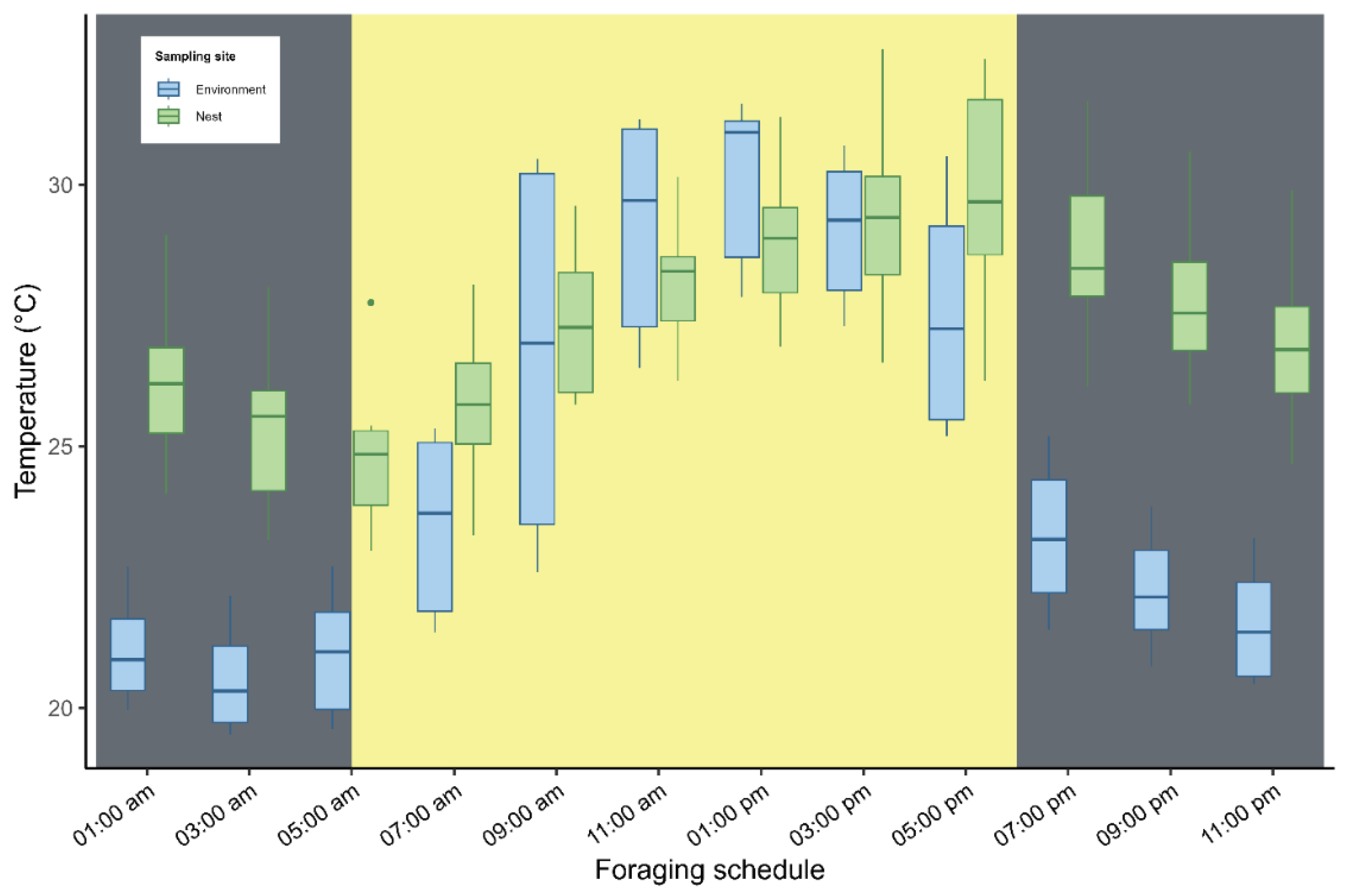

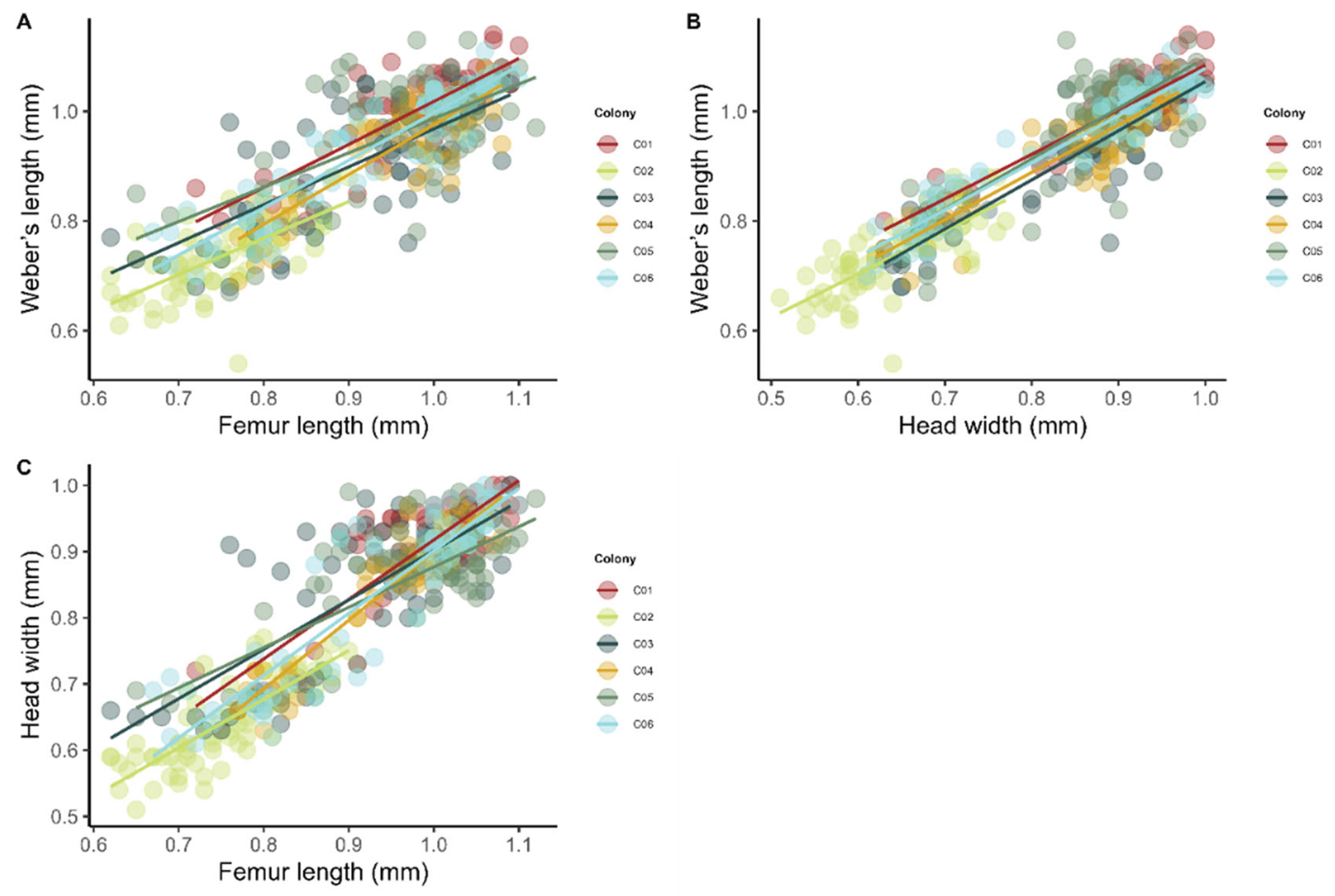

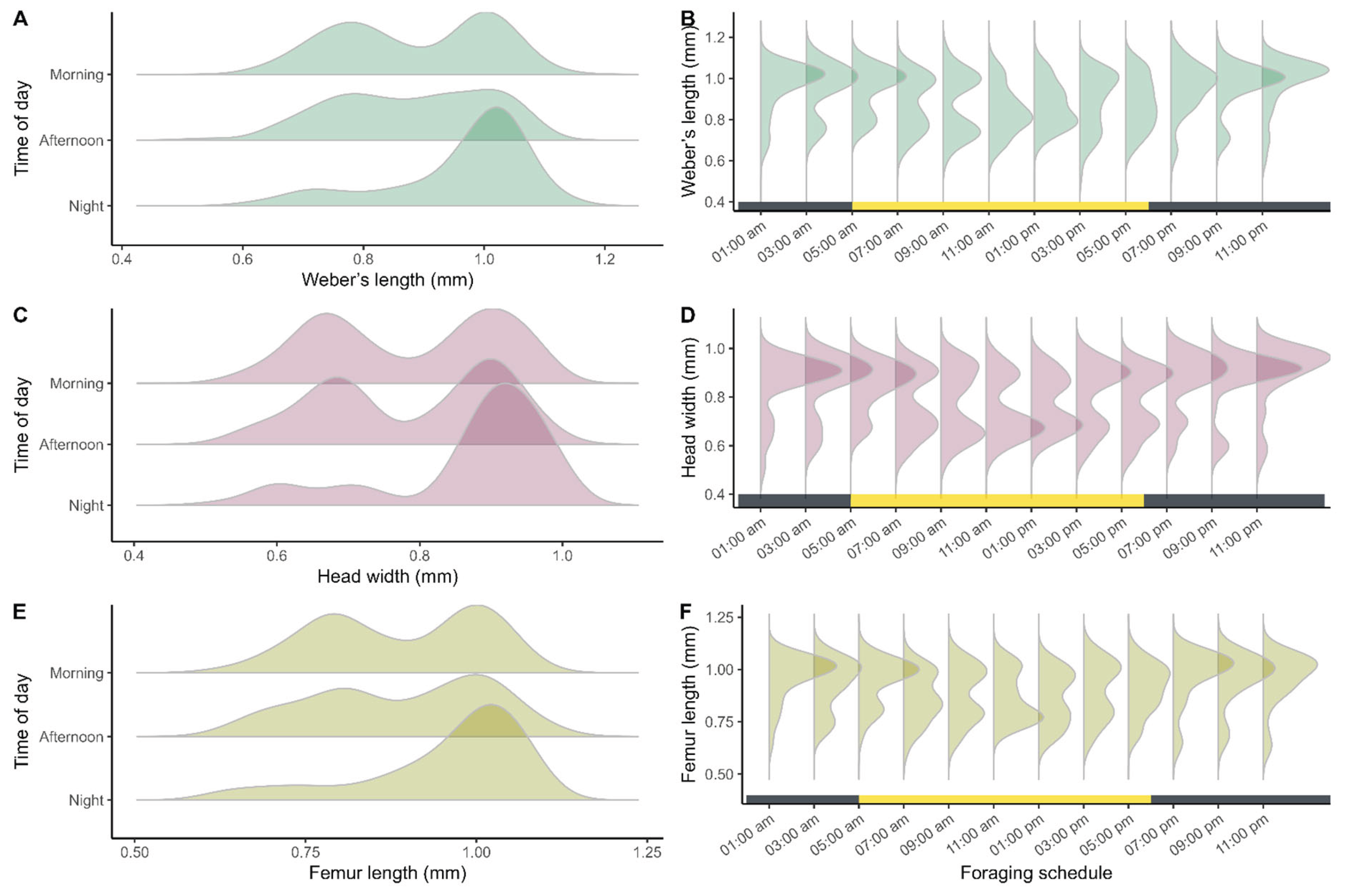

3.2. Phase II: Thermal Ecology and Worker Morphometry

4. Discussion

4.1. Phase I: Internal Nest Humidity Patterns

4.2. Phase II: Thermal Ecology and Worker Morphometry

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hölldobler, B.; Wilson, E.O. The Ants. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard Univ. Press 1990, xii +-732.

- Passera, L.; Aron, S. Les Fourmis: Comportement, Organisation Sociale et Évolution; 2005; ISBN 066097021X.

- Jones, J.C.; Oldroyd, B.P. Nest thermoregulation in social insects. In Advances in Insect Physiology; 2006; Vol. 33, pp. 153–191.

- Kadochová, Š.; Frouz, J. Thermoregulation strategies in ants in comparison to other social insects, with a focus on red wood ants (Formica rufa group). F1000Research 2014, 2, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankovitz, M.; Purcell, J. Ant nest architecture is shaped by local adaptation and plastic response to temperature. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 23053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penick, C.A.; Tschinkel, W.R. Thermoregulatory brood transport in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Insectes Soc. 2008, 55, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollazzi, M.; Roces, F. The thermoregulatory function of thatched nests in the South American grass-cutting ant, Acromyrmex heyeri. J. Insect Sci. 2010, 10, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, N.R. Thermoregulation in army ant bivouacs. Physiol. Entomol. 1989, 14, 397–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapointe, S.L.; Serrano, M.S.; Jones, P.G. Microgeographic and vertical distribution of Acromyrmex landolti (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) nests in a Neotropical savanna. Environ. Entomol. 1998, 27, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollazzi, M.; Kronenbitter, J.; Roces, F. Soil temperature, digging behaviour, and the adaptive value of nest depth in South American species of Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants. Oecologia 2008, 158, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García Ibarra, F.; Jouquet, P.; Bottinelli, N.; Bultelle, A.; Monnin, T. Experimental evidence that increased surface temperature affects bioturbation by ants. J. Anim. Ecol. 2024, 93, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolay, S.; Boulay, R.; D’Ettorre, P. Regulation of ant foraging: A review of the role of information use and personality. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, X. Behavioural and physiological traits to thermal stress tolerance in two Spanish desert ants. Etologia 2001, 9, 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jayatilaka, P.; Narendra, A.; Reid, S.F.; Cooper, P.; Zeil, J. Different effects of temperature on foraging activity schedules in sympatric Myrmecia ants. J. Exp. Biol. 2011, 214, 2730–2738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujan, J.; Yanoviak, S.P. Behavioral response to heat stress of twig-nesting canopy ants. Oecologia 2022, 198, 947–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roeder, D. V.; Paraskevopoulos, A.W.; Roeder, K.A. Thermal tolerance regulates foraging behaviour of ants. Ecol. Entomol. 2022, 47, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalta, I.; Oms, C.S.; Angulo, E.; Molinas-González, C.R.; Devers, S.; Cerdá, X.; Boulay, R. Does social thermal regulation constrain individual thermal tolerance in an ant species? J. Anim. Ecol. 2020, 89, 2063–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, S.D. Impact of temperature on colony growth and developmental rates of the ant, Solenopsis invicta. J. Insect Physiol. 1988, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipyatkov, V.E.; Lopatina, E.B.; Imamgaliev, A.A.; Shirokova, L.A. Effect of temperature on rearing of the first brood by the founder females of the ant Lasius niger (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) : Latitude-dependent variability of the response norm. J. Evol. Biochem. Physiol. 2004, 40, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidenmüller, A.; Mayr, C.; Kleineidam, C.J.; Roces, F. Preimaginal and adult experience modulates the thermal response behavior of ants. Curr. Biol. 2009, 19, 1897–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penick, C.A.; Diamond, S.E.; Sanders, N.J.; Dunn, R.R. Beyond thermal limits: comprehensive metrics of performance identify key axes of thermal adaptation in ants. Funct. Ecol. 2017, 31, 1091–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, N.R.; Hart, R.A.; Jung, M.P.; Hemmings, Z.; Terblanche, J.S. Can temperate insects take the heat? A case study of the physiological and behavioural responses in a common ant, Iridomyrmex purpureus (Formicidae), with potential climate change. J. Insect Physiol. 2013, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspari, M.; Clay, N.A.; Lucas, J.; Yanoviak, S.P.; Kay, A. Thermal adaptation generates a diversity of thermal limits in a rainforest ant community. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2015, 21, 1092–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujan, J.; Roeder, K.A.; Yanoviak, S.P.; Kaspari, M. Seasonal plasticity of thermal tolerance in ants. Ecology 2020, 101, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roeder, K.A.; Bujan, J.; de Beurs, K.M.; Weiser, M.D.; Kaspari, M. Thermal traits predict the winners and losers under climate change: An example from North American ant communities. Ecosphere 2021, 12, e03645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, A. a; Bispo, P.C.; Zanzini, A.C. Efeito do turno de coleta sobre comunidades de formigas epigéicas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) em áreas de Eucalyptus cloeziana e de cerrado. Neotrop. Entomol. 2008, 37, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Robledo, C.; Chuquillanqui, H.; Kuprewicz, E.K.; Escobrar-Sarria, F. Lower thermal tolerance in nocturnal than in diurnal ants: A Challenge for nocturnal ectotherms facing global warming. Ecol. Entomol. 2018, 43, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, X.; Retana, J.; Cros, S. Critical thermal limits in mediterranean ant species: Trade-off between mortality risk and foraging performance. Funct. Ecol. 1998, 12, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard, J.-P.; Dunn, R.R.; Sanders, N.J. Temperature-mediated coexistence in temperate forest ant communities. Insectes Soc. 2009, 56, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuble, K.L.; Rodriguez-Cabal, M.A.; McCormick, G.L.; Juric, I.; Dunn, R.R.; Sanders, N.J. Tradeoffs, competition, and coexistence in eastern deciduous forest ant communities. Oecologia 2013, 171, 981–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruano, F.; Tinaut, A.; Soler, J.J. High surface temperatures select for individual foraging in ants. Behav. Ecol. 2000, 11, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oudenhove, L.; Billoir, E.; Boulay, R.; Bernstein, C.; Cerdá, X. Temperature limits trail following behaviour through pheromone decay in ants. Naturwissenschaften 2011, 98, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobua-Behrmann, B.E.; Lopez De Casenave, J.; Milesi, F.A.; Farji-Brener, A. Coexisting in harsh environments: temperature-based foraging patterns of two desert leafcutter ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Attini). Myrmecological News 2017, 25, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Banschbach, V.S.; Levit, N.; Herbers, J.M. Nest temperatures and thermal preferences of a forest ant species: is seasonal polydomy a thermoregulatory mechanism ? Insectes Soc. 1997, 44, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, B.D.; Powell, S.; Rivera, M.D.; Suarez, A. V. Correlates and consequences of worker polymorphism in ants. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2018, 63, 575–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busher, C.E.; Calabi, P.; Traniello, J.F.A. Polymorphism and division of labor in the Neotropical ant Camponotus sericeiventris Guerin (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 1985, 78, 221–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, R.H.; Newey, P.S.; Schlüns, E.A.; Robson, S.K.A. A masterpiece of evolution Oecophylla weaver ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Myrmecological News 2009, 13, 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kamhi, J.F.; Nunn, K.; Robson, S.K.A.; Traniello, J.F.A. Polymorphism and division of labour in a socially complex ant: neuromodulation of aggression in the australian weaver ant, Oecophylla smaragdina. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2015, 282, 20150704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narendra, A.; Reid, S.F.; Raderschall, C.A. Navigational efficiency of nocturnal Myrmecia ants suffers at low light levels. PLoS One 2013, 8, e58801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kay, J.; Menegazzi, P.; Mildner, S.; Roces, F.; Helfrich-Förster, C. The circadian clock of the ant Camponotus floridanus is localized in dorsal and lateral neurons of the brain. J. Biol. Rhythms 2018, 33, 255–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libbrecht, R.; Nadrau, D.; Foitzik, S. A role of histone acetylation in the regulation of circadian rhythm in ants. iScience 2020, 23, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Lone, S.; Goel, A.; Chandrashekaran, M.K. Circadian consequences of social organization in the ant species Camponotus compressus. Naturwissenschaften 2004, 91, 386–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspari, M. Body Size and microclimate use in Neotropical granivorous ants. Oecologia 1993, 96, 500–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, Y.; Morimoto, Y.; Widodo, E.S.; Mohamed, M.; Fellowes, J.R. Vertical habitat use and foraging activities of arboreal and ground ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a Bornean tropical rainforest. Sociobiology 2010, 56, 435–448. [Google Scholar]

- Stark, A.Y.; Adams, B.J.; Fredley, J.L.; Yanoviak, S.P. Out on a limb: Thermal microenvironments in the tropical forest canopy and their relevance to ants. J. Therm. Biol. 2017, 69, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leahy, L.; Scheffers, B.R.; Williams, S.E.; Andersen, A.N. Arboreality drives heat tolerance while elevation drives cold tolerance in tropical rainforest ants. Ecology 2022, 103, e03549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devarajan, K. The antsy social network: Determinants of nest structure and arrangement in Asian weaver ants. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0156681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langshiang, E.S.; Hajong, S.R. Determination of structural features of the nest material of Crematogaster rogenhoferi (Mayr, 1879) (Hymenoptera: Myrmicinae). J. Entomol. Zool. Stud. 2018, 6, 1626–1631. [Google Scholar]

- Spicer, M.E.; Stark, A.Y.; Adams, B.J.; Kneale, R.; Kaspari, M.; Yanoviak, S.P. Thermal constraints on foraging of tropical canopy ants. Oecologia 2017, 183, 1007–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuble, K.L.; Pelini, S.L.; Diamond, S.E.; Fowler, D.A.; Dunn, R.R.; Sanders, N.J. Foraging by forest ants under experimental climatic warming: A test at two sites. Ecol. Evol. 2013, 3, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarenhas, H.P. Utilidade das formiguinhas de S. Mateus. Rev. Agr. Imp. Inst. Flum. Agric. 1883, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, H.G.; Medeiros, M.A.; Delabie, J.H.C. Carton Nest allometry ans spatial patterning of the arboreal ant Azteca chartifex spiriti ( Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Rev. Bras. Entomol. 1996, 40, 337–339. [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni, K.G.; Borkar, V.D. Architecture of arboreal nests of Crematogaster ants. In: Sediment Organism Interactions. A Multifaceted Ichnology; SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology, 2007; Vol. 88, pp. 373–377.

- Jiménez-Soto, E.; Cruz-Rodríguez, J.A.; Vandermeer, J.; Perfecto, I. Hypothenemus hampei (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) and its interactions with Azteca instabilis and Pheidole synanthropica (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a shade coffee agroecosystem. Environ. Entomol. 2013, 42, 915–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delabie, J.C. The ant problems of cocoa farms in Brazil. In: Applied Myrmecology: A World Perspective. Vander Meer, R.K., Jaffé, K., Cedeño, A., Eds., Boulder, Colorado, USA, 1990, 555-569.

- Delabie, J.H.C.; Benton, F.P.; Medeiros, M.A. La polydomie chez les Formicidae arboricoles dans les cacaoyères du Brésil: Optimisation de l’occupation de l’espace ou strategie défensive? Actes Coll. Insectes Soc. 1991, 7, 173–178. [Google Scholar]

- Delabie, J.H.C. Trophobiosis between Formicidae and Hemiptera (Sternorrhyncha and Auchenorrhyncha): An overview. Neotrop. Entomol. 2001, 30, 501–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, V.L.; Koch, E.; Delabie, J.H.C.; Bomfim, L.; Padre, J.; Mariano, C. Nest spatial structure and population organization in the Neotropical ant Azteca chartifex spiriti Forel, 1912 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae: Dolichoderinae). Ann. Soc.Entomol. Fr. 2021, 57, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer, J.D.; Delabie, J.H.C.; Smith, M.R.B. Arboreal ant community patterns in Brazilian cocoa farms. Biotropica 1994, 26, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, G.R.; Anjos, D. V.; da Costa, F.V.; Lourenço, G.M.; Campos, R.I.; Ribeiro, S.P. Positive effects of ants on host trees are critical in years of low reproduction and not influenced by liana presence. Basic Appl. Ecol. 2022, 63, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, G.R.; Lourenço, G.M.; Costa, F. V.; Lopes, I.; Felisberto, B.H.; Pinto, V.D.; Campos, R.I.; Ribeiro, S.P. Territory and trophic cascading effects of the ant Azteca chartifex (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in a tropical canopy. Myrmecological News 2022, 32, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delabie, J.H.C.; Mariano, C.S.F. Papel das formigas (Insecta: Hymenoptera : Formicidae) no controle biológico das pragas do cacaueiro na Bahia: síntese e limitações. In Proceedings of the International Cocoa Research Conference; Kota Kinabalu, Sabah, Malaysia, 2000; pp. 725–731.

- Medeiros, M.A. De; Fowler, H.G.; Delabie, J.H.C. O mosaico de formigas (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) em cacauais do Sul da Bahia. Cientifica 1995, 23, 291–300. [Google Scholar]

- Gouvea, J.B.S.; Silva, L.A.M.; Hori, M. 1. Fitogeografia. 2. Recursos Florestais. 3. Principais Vegetais Úteis. Comissão Executiva do Plano da Lavoura Cacaueira. Ilhéus. Ceplac/IICA. Diagnóstico Sócio-Econômico da Região Cacaueira; Ilheus, 1976; Vol. 7, 246 pp.

- Cassano, C.R.; Schroth, G.; Faria, D.; Delabie, J.H.C.; Bede, L. Landscape and farm scale management to enhance biodiversity conservation in the cocoa producing region of Southern Bahia, Brazil. Biodivers. Conserv. 2009, 18, 577–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, T.R.; Robertson, M.P.; van Rensburg, B.J.; Parr, C.L. Contrasting species and functional beta diversity in montane ant assemblages. J. Biogeogr. 2015, 42, 1776–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspari, M.; Weiser, M.D. The size–grain hypothesis and interspecific scaling in ants. Funct. Ecol. 1999, 13, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakeham-Dawson, A. Ant architecture: The wonder, beauty and science of underground nests. Entomol. Mon. Mag. 2021, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römer, D.; Bollazzi, M.; Roces, F. Carbon dioxide sensing in an obligate insect-fungus symbiosis: CO2 preferences of leaf-cutting ants to rear their mutualistic fungus. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0174597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longino, J.T. Ants provide substrate for epiphytes. Selbyana 1986, 9, 100–103. [Google Scholar]

- Santos, J.C.; Del-Claro, K. Ecology and behaviour of the weaver ant Camponotus (Myrmobrachys) senex. J. Nat. Hist. 2009, 43, 1423–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tranter, C.; Hughes, W.O.H. A preliminary study of nest structure and composition of the weaver ant Polyrhachis (Cyrtomyrma) delecta (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). J. Nat. Hist. 2016, 50, 1197–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martius, C. Nest architecture of Nasutitermes termites in a white water floodplain forest in Central Amazonia, and a field key to species (Isoptera, Termitidae). Andrias 2001, 15, 163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Henrique-Simões, M.; Cuozzo, M.D.; Frieiro-Costa, F.A. Social wasps of Unilavras/Boqueirão Biological Reserve, Ingaí, state of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Check List 2011, 7, 656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmolz, E.; Brüders, N.; Daum, R.; Lamprecht, I. Thermoanalytical investigations on paper covers of social wasps. Thermochim. Acta 2000, 361, 121–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klingner, R.; Richter, K.; Schmolz, E.; Keller, B. The role of moisture in the nest thermoregulation of social wasps. Naturwissenschaften 2005, 92, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frouz, J. The effect of nest moisture on daily temperature regime in the nests of Formica polyctena wood ants. Insectes Soc. 2000, 47, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coenen-Stass, D.; Schaarschmidt, B.; Lamprecht, I. Temperature distribution and calorimetric determination of heat production in the nest of the wood ant, Formica polyctena (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Ecology 1980, 61, 238–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosengren, R.; Fortelius, W.; Lindstrom, K.; Luther, A. Phenology and causation of nest heating and thermoregulation in red wood ants of the Formica rufa group studied in coniferous forest habitats in Southern Finland. Ann. Zool. Fennici 1987, 24, 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Korb, J.; Linsenmair, K.E. Thermoregulation of termite mounds: what role does ambient temperature and metabolism of the colony play? Insectes Soc. 2000, 47, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lachaud, G.; Lachaud, J.-P. Arboreal ant colonies as ‘hot-points’ of cryptic diversity for myrmecophiles: the weaver ant Camponotus sp. aff. textor and its interaction network with its associates. PLoS One 2014, 9, e100155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lachaud, G.; Jahyny, B.J.B.; Ståhls, G.; Rotheray, G.; Delabie, J.H.C.; Lachaud, J.-P. Rediscovery and reclassification of the dipteran taxon Nothomicrodon Wheeler, an exclusive endoparasitoid of gyne ant larvae. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho-Filho, F.S.; Barbosa, R.R.; Soares, M.M.M. Brakemyia, a new neotropical jackal fly genus of Milichiidae (Insecta: Diptera) associated with carton ant nest. Zool. Stud. 2023, 62, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, E. Polymorphism and division of labor in Azteca chartifex laticeps (Hymenoptera : Formicidae). J. Kansas Entomol. Soc. 1986, 59, 542–548. [Google Scholar]

- Longino, J.T. A taxonomic review of the genus Azteca (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Costa Rica and a global revision of the Aurita group. Zootaxa 2007, 1491, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clémencet, J.; Cournault, L.; Odent, A.; Doums, C. Worker thermal tolerance in the thermophilic ant Cataglyphis cursor (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Insectes Soc. 2010, 57, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donnell, S.; Bulova, S.; Caponera, V.; Oxman, K.; Giladi, I. Species differ in worker body size effects on critical thermal limits in seed-harvesting desert ants (Messor ebeninus and M. arenarius). Insectes Soc. 2020, 67, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnan, X.; Lázaro-González, A.; Beltran, N.; Rodrigo, A.; Pol, R. Thermal physiology, foraging pattern, and worker body size interact to influence coexistence in sympatric polymorphic harvester ants (Messor spp.). Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2022, 76, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, R.; Benbachir, M.; Decroo, C.; Mascolo, C.; Wattiez, R.; Aron, S. Cataglyphis desert ants use distinct behavioral and physiological adaptations to cope with extreme thermal conditions. J. Therm. Biol. 2023, 111, 103397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).