Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

The Current Study

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Treatment

3. Measures

3.1. The 3-Stimulus Odd-Ball Task

3.2. Electrooculograms (Eye Blinks)

3.3. Event-Related Potentials

3.4. Mood and Arousal Measures

4. Results

4.1. Subjective Arousal and Mood Ratings

4.2. Blink Metrics (Total Rate and Variability)

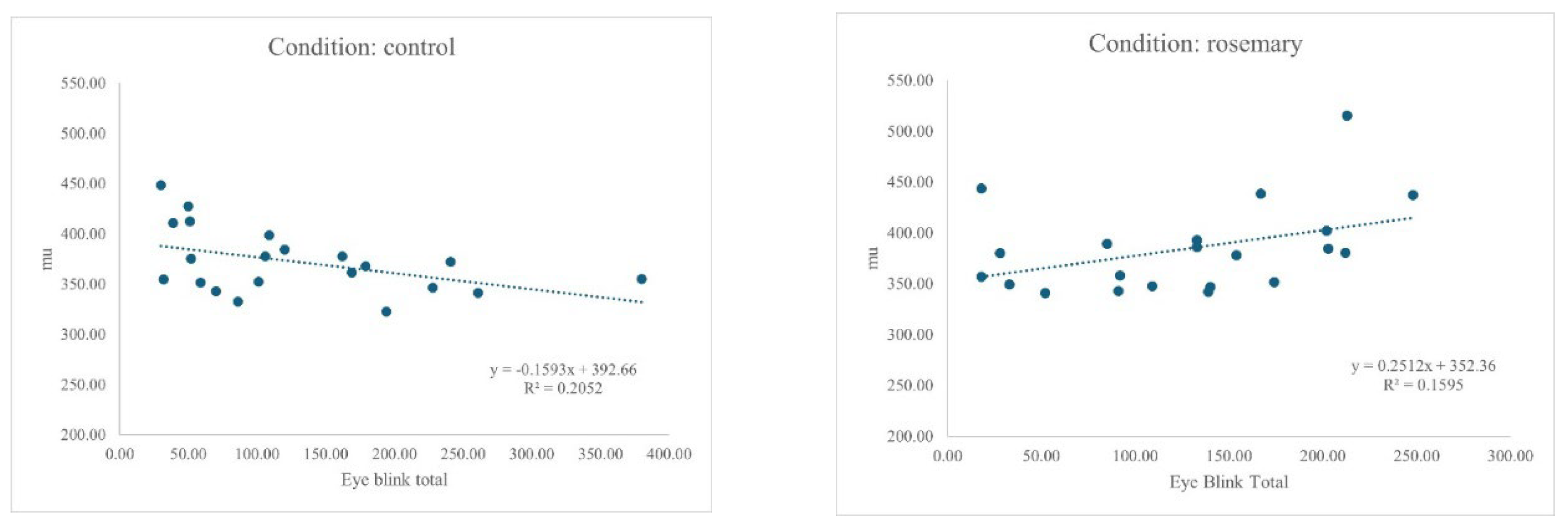

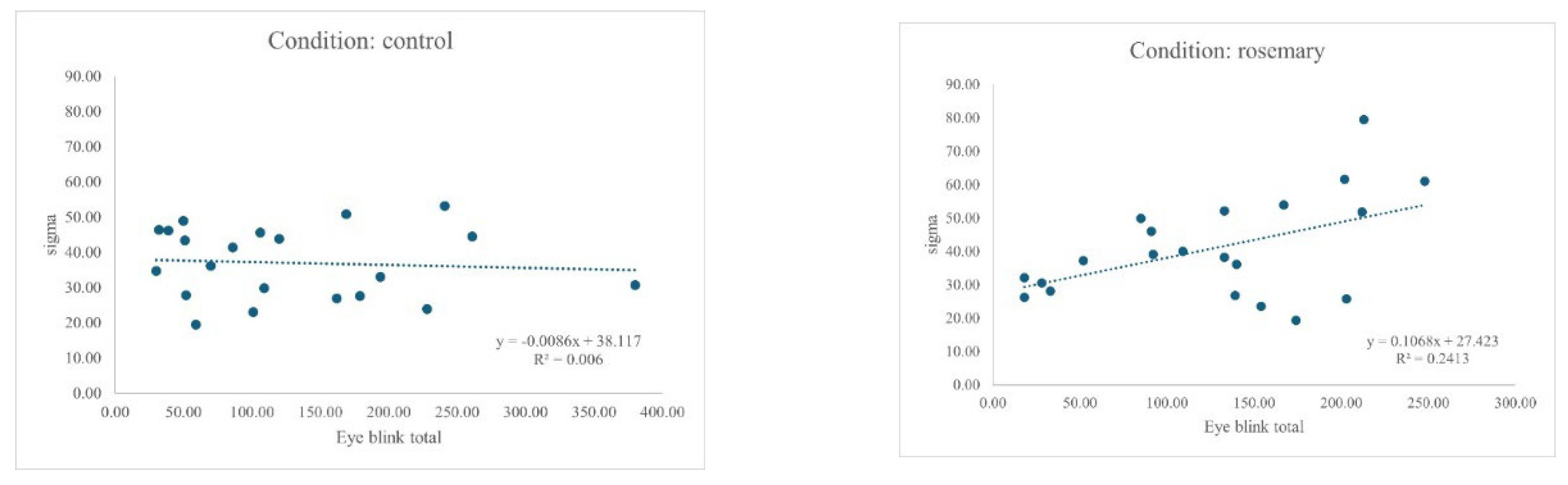

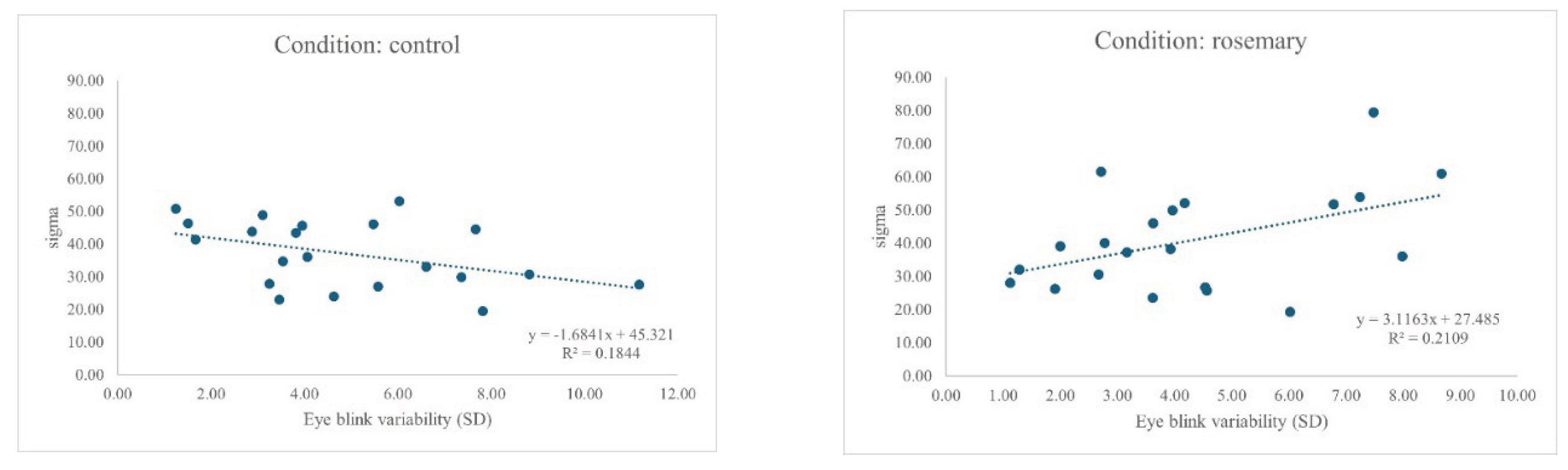

4.3. Bivariate Correlations

Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Ribeiro-Santos, R.; Carvalho-Costa, D.; Cavaleiro, C.; Costa, H.S.; Albuquerque, T.G.; Castilho, M.C.; Ramos, F.; Melo, N.R.; Sanches-Silva, A. A novel insight on an ancient aromatic plant: The rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.). Trends in Food Science & Technology 2015, 45, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, J.R. Rosemary, the beneficial chemistry of a garden herb. Science progress 2016, 99, 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Shakespeare, W. Hamlet. 1603.

- Moss, M.; Cook, J.; Wesnes, K.; Duckett, P. Aromas of rosemary and lavender essential oils differentially affect cognition and mood in healthy adults. International Journal of Neuroscience 2003, 113, 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singletary, K. Rosemary: an overview of potential health benefits. Nutrition Today 2016, 51, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hongratanaworakit, T. Simultaneous aromatherapy massage with rosemary oil on humans. Scientia Pharmaceutica 2009, 77, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasselmo, M.E. The role of acetylcholine in learning and memory. Current opinion in neurobiology 2006, 16, 710–715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mesulam, M.-M. The cholinergic innervation of the human cerebral cortex. Progress in brain research 2004, 145, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ballinger, E.C.; Ananth, M.; Talmage, D.A.; Role, L.W. Basal forebrain cholinergic circuits and signaling in cognition and cognitive decline. Neuron 2016, 91, 1199–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarter, M.; Gehring, W.J.; Kozak, R. More attention must be paid: the neurobiology of attentional effort. Brain research reviews 2006, 51, 145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Savelev, S.; Okello, E.; Perry, N.; Wilkins, R.; Perry, E. Synergistic and antagonistic interactions of anticholinesterase terpenoids in Salvia lavandulaefolia essential oil. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 2003, 75, 661–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colovic, M.B.; Krstic, D.Z.; Lazarevic-Pasti, T.D.; Bondzic, A.M.; Vasic, V.M. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: pharmacology and toxicology. Current neuropharmacology 2013, 11, 315–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duszkiewicz, A.J.; McNamara, C.G.; Takeuchi, T.; Genzel, L. Novelty and dopaminergic modulation of memory persistence: a tale of two systems. Trends in neurosciences 2019, 42, 102–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matzel, L.D.; Sauce, B. A multi-faceted role of dual-state dopamine signaling in working memory, attentional control, and intelligence. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 2023, 17, 1060786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitzianti, M.B.; Spiridigliozzi, S.; Bartolucci, E.; Esposito, S.; Pasini, A. New insights on the effects of methylphenidate in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2020, 11, 531092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanzione, A.; Melchiori, F.M.; Costa, A.; Leonardi, C.; Scalici, F.; Caltagirone, C.; Carlesimo, G.A. Dopaminergic Treatment and Episodic Memory in Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-analysis of the Literature. Neuropsychology Review 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Howes, O.D.; Kapur, S. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: version III—the final common pathway. Schizophrenia bulletin 2009, 35, 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongkees, B.J.; Hommel, B.; Kühn, S.; Colzato, L.S. Effect of tyrosine supplementation on clinical and healthy populations under stress or cognitive demands—A review. Journal of psychiatric research 2015, 70, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbardar, M.G.; Hosseinzadeh, H. Therapeutic effects of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) and its active constituents on nervous system disorders. Iranian journal of basic medical sciences 2020, 23, 1100. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy, V.C.; Patel, S.V.; Hodge, D.O.; Leavitt, J.A. Corneal sensitivity, blink rate, and corneal nerve density in progressive supranuclear palsy and Parkinson disease. Cornea 2013, 32, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riby, L.M.; Fenwick, S.K.; Kardzhieva, D.; Allan, B.; McGann, D. Unlocking the beat: Dopamine and eye blink response to classical music. NeuroSci 2023, 4, 152–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, J.; Dreisbach, G.; Brocke, B.; Lesch, K.-P.; Strobel, A.; Goschke, T. Dopamine and cognitive control: The influence of spontaneous eyeblink rate, DRD4 exon III polymorphism and gender on flexibility in set-shifting. Brain research 2007, 1131, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollander, J.; Huette, S. Extracting blinks from continuous eye-tracking data in a mind wandering paradigm. Consciousness and Cognition 2022, 100, 103303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riby, L.M.; Marr, L.; Barron-Millar, L.; Greer, J.; Hamilton, C.J.; McGann, D.; Smallwood, J. Elevated blink rates predict mind wandering: Dopaminergic insights into attention and task focus. Journal of Integrative Neuroscience 2025, 24, 26508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parris, B.A.; Dienes, Z.; Hodgson, T.L. Application of the ex-Gaussian function to the effect of the word blindness suggestion on Stroop task performance suggests no word blindness. Frontiers in psychology 2013, 4, 647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riby, L.M.; Edwards, S.; McDonald, H.; Moss, M. The impact of a rosemary containing drink on event-related potential neural markers of sustained attention. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0286113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polich, J. Updating P300: an integrative theory of P3a and P3b. Clinical neurophysiology 2007, 118, 2128–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bond, A.; Lader, M. The use of analogue scales in rating subjective feelings. British Journal of Medical Psychology 1974, 47, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayorwan, W.; Ruangrungsi, N.; Piriyapunyporn, T.; Hongratanaworakit, T.; Kotchabhakdi, N.; Siripornpanich, V. Effects of inhaled rosemary oil on subjective feelings and activities of the nervous system. Scientia pharmaceutica 2012, 81, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattayakhom, A.; Wichit, S.; Koomhin, P. The effects of essential oils on the nervous system: A scoping review. Molecules 2023, 28, 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moss, M.; Hewitt, S.; Moss, L.; Wesnes, K. Modulation of cognitive performance and mood by aromas of peppermint and ylang-ylang. International Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 118, 59–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawiset, T.; Sriraksa, N.; Somwang, P.; Inkaew, P. Effect of orange essential oil inhalation on mood and memory in female humans. Journal of Physiological and Biomedical Sciences 2016, 29, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, C.C.; Miranda, B.; Sathishkumar, M.; Dehkordi-Vakil, F.; Yassa, M.A.; Leon, M. Overnight olfactory enrichment using an odorant diffuser improves memory and modifies the uncinate fasciculus in older adults. Frontiers in Neuroscience 2023, 17, 1200448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riby, L.M. The impact of age and task domain on cognitive performance: a meta-analytic review of the glucose facilitation effect. Brain Impairment 2004, 5, 145–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongkees, B.J.; Colzato, L.S. Spontaneous eye blink rate as predictor of dopamine-related cognitive function—A review. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2016, 71, 58–82. [Google Scholar]

- Dreisbach, G.; Müller, J.; Goschke, T.; Strobel, A.; Schulze, K.; Lesch, K.-P.; Brocke, B. Dopamine and cognitive control: the influence of spontaneous eyeblink rate and dopamine gene polymorphisms on perseveration and distractibility. Behavioral neuroscience 2005, 119, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callara, A.L.; Greco, A.; Scilingo, E.P.; Bonfiglio, L. Neuronal correlates of eyeblinks are an expression of primary consciousness phenomena. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 12617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, J.; Plaska, C.R.; Gomes, B.A.; Ellmore, T.M. Spontaneous eye blink rate during the working memory delay period predicts task accuracy. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 788231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paprocki, R.; Lenskiy, A. What does eye-blink rate variability dynamics tell us about cognitive performance? Frontiers in human neuroscience 2017, 11, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rac-Lubashevsky, R.; Slagter, H.A.; Kessler, Y. Tracking real-time changes in working memory updating and gating with the event-based eye-blink rate. Scientific reports 2017, 7, 2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, G.; Iqbal, S.T.; Czerwinski, M.; Johns, P. Bored mondays and focused afternoons: the rhythm of attention and online activity in the workplace. . In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2014; pp. 3025-3034.

- Veltman, J.; Gaillard, A. Physiological workload reactions to increasing levels of task difficulty. Ergonomics 1998, 41, 656–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, E.; Riby, L.M.; Greer, J.; Smallwood, J. Absorbed in thought: the effect of mind wandering on the processing of relevant and irrelevant events. Psychol Sci 2011, 22, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dane, E. Paying attention to mindfulness and its effects on task performance in the workplace. Journal of management 2011, 37, 997–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Measure | Control M (SD) | Rosemary M (SD) | Cohen's d |

| Eye Blink Rate (EBR) | 120.24 ± 90.21 | 122.91 ± 67.77 | 0.03 |

| Blink Variability (EBV) | 4.69 ± 2.52 | 4.14 ± 2.21 | -0.23 |

| Alertness (Pre) | 35.11 ± 12.08 | 36.91 ± 11.56 | 0.15 |

| Calmness (Pre) | 30.91 ± 14.43 | 33.54 ± 17.75 | 0.17 |

| Contentedness (Pre) | 24.22 ± 9.48 | 26.67 ± 10.97 | 0.25 |

| Alertness (Post) | 38.32 ± 18.48 | 45.06 ± 18.01 | 0.37 |

| Calmness (Post) | 32.92 ± 13.99 | 32.87 ± 14.00 | -0.00 |

| Contentedness (Post) | 28.34 ± 10.94 | 30.97 ± 15.06 | 0.19 |

| Mu (μ) | 372.04 ± 32.40 | 383.98 ± 44.06 | 0.31 |

| Sigma (σ) | 37.01 ± 10.15 | 40.87 ± 15.24 | 0.30 |

| Tau (τ) | 33.86 ± 12.74 | 36.81 ± 10.61 | 0.25 |

| Hits | 75.75 ± 21.53 | 78.37 ± 14.67 | 0.13 |

| P3a Amplitude (Cz) | 4.79 ± 2.86 | 6.44 ± 2.89 | 0.63 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| 1. Eye blink total | 1 | .588** | .555** | .232 | .316 | .309 | .051 | .063 | -.453* | -.078 | .042 | -.281 | .176 |

| 2. Eye blink variability | .588** | 1 | .462* | .164 | .302 | .416* | .174 | .243 | -.138 | -.429 | -.062 | .114 | -.319 |

| 3. Alertness (pre) | .555** | .462* | 1 | -.117 | .249 | .692** | -.132 | .266 | -.296 | -.428 | .396 | .857 | .498 |

| 4. Calmness (pre) | .232 | .164 | -.117 | 1 | .237 | .048 | .220 | -.049 | .084 | -.063 | -.342 | .162 | -.086 |

| 5. Contentedness (pre) | .316 | .302 | .249 | .237 | 1 | .496* | .265 | .267 | -.312 | -.480* | -.061 | -.113 | -.040 |

| 6. Alertness (post) | .309 | .416* | .692** | .048 | .496* | 1 | -.133 | .572** | -.146 | -.234 | -.330 | -.036 | .424 |

| 7. Calmness (post) | .051 | .174 | -.132 | .220 | .265 | -.133 | 1 | .511* | -.197 | -.197 | -.438 | .205 | .446 |

| 8. Contentedness (post) | .063 | .243 | .243 | .266 | .267 | .572** | .511* | 1 | -.269 | -.104 | -.400 | -.314 | .436 |

| 9. mu (μ) | -.453* | -.138 | -.296 | .084 | -.312 | -.146 | -.197 | -.269 | 1 | .242 | .136 | .448* | -.252 |

| 10. sigma (σ) | -.078 | -.429 | -.428 | -.063 | -.480* | -.234 | -.197 | -.104 | .242 | 1 | -.002 | -.250 | .262 |

| 11. tau (τ) | .042 | -.062 | .396 | -.342 | -.061 | -.330 | -.438 | -.400 | .136 | -.002 | 1 | .046 | -.163 |

| 12. hits | -.281 | .114 | .857 | .162 | -.113 | -.036 | .205 | -.314 | .448* | -.250 | .046 | 1 | -.559* |

| 13. P3a ERP | .176 | -.319 | .498 | -.086 | -.040 | .424 | .446 | .436 | -.252 | .262 | -.163 | -.559* | 1 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| 1. Eye blink total | 1 | .776** | .228 | .201 | .158 | .056 | .092 | .077 | .399 | .491* | .118 | .001 | -.227 |

| 2. Eye blink variability | .776** | 1 | .215 | .262 | .426* | .221 | -.049 | .306 | .388 | .459* | .096 | .345 | -.310 |

| 3. Alertness (pre) | .228 | .215 | 1 | .337 | .467* | .465* | -.275 | .475* | .242 | .388 | .104 | -.091 | -.251 |

| 4. Calmness (pre) | .201 | .262 | .337 | 1 | .826** | .375 | .498* | .743** | .291 | .433 | .290 | .323 | .138 |

| 5. Contentedness (pre) | .158 | .426* | .467* | .826** | 1 | .469* | .267 | .865** | .302 | .371 | .188 | .388 | -.095 |

| 6. Alertness (post) | .056 | .221 | .465* | .375 | .469* | 1 | -.043 | .739** | -.038 | -.134 | -.117 | .195 | .015 |

| 7. Calmness (post) | .092 | -.049 | -.275 | .498* | .267 | -.043 | 1 | .241 | .041 | .155 | -.149 | -.221 | .275 |

| 8. Contentedness (post) | .077 | .306 | .475* | .743** | .865** | .739** | .241 | 1 | .023 | .182 | .182 | .318 | .019 |

| 9. mu (μ) | .399 | .388 | .242 | .291 | .302 | -.038 | .155 | .182 | 1 | .691** | -.004 | .181 | -.026 |

| 10. sigma (σ) | .491* | .459* | .388 | .433 | .371 | -.134 | .155 | .182 | .691** | 1 | .108 | .258 | -.032 |

| 11. tau (τ) | .118 | .096 | .104 | .290 | .188 | -.117 | -.149 | .182 | -.004 | .108 | 1 | .531* | -.247 |

| 12. hits | .001 | .345 | -.091 | .323 | .388 | .195 | -.221 | .318 | .181 | .258 | .531* | 1 | -.120 |

| 13. P3a ERP | -.227 | -.310 | -.251 | .138 | -.095 | .015 | .275 | .019 | -.026 | -.032 | -.247 | -.120 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).