1. Introduction

In conventional quantum field theory, the vacuum is treated as a continuous and unbounded energetic background [

2,

4]. All possible fluctuation modes, extending up to arbitrarily high energies, contribute to the vacuum energy. This leads to the well-known discrepancy between the theoretically predicted vacuum energy density and the observed value of the cosmological constant, representing one of the central tensions in modern theoretical physics [

3]. In this work we develop a unified theoretical framework, referred to as the

Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) model Ref. [

1]. The QEV model describes the vacuum as a spectrally bounded medium whose physical properties, particle content, coupling structure and gravitational response all arise from its internal spectral organization.

At the microscopic level, this perspective implies that the apparent “emptiness” inside atoms is not an inert void but the structured Quantum Emergent Vacuum itself: most of the atomic volume is occupied by the spectrally bounded vacuum, while nuclei and electrons appear as localized excitations of this underlying spectral medium. In this sense, atomic structure directly reflects the internal organization of the vacuum, rather than being embedded in a featureless background.

Vacuum fluctuations are allowed only within a finite energy interval, bounded above by a hadronic limit (the QCD confinement scale) and below by a thermal limit (a critical temperature associated with hadronic matter formation) [

4]. Within these boundaries, we introduce a spectral density and a discrete set of energy levels, and we propose the hypothesis that the stable particles of the Standard Model can be interpreted as excitations of this bounded vacuum spectrum. Gauge symmetries and coupling constants appear in this picture as emergent properties of the internal spectral structure.

Furthermore, we connect the spectral description of the vacuum to a thermodynamic formulation by introducing a spectral entropy and an effective temperature. This allows a thermodynamic interpretation of gravity as a response of the bounded vacuum spectrum to matter-energy, in the spirit of induced and entropic gravity scenarios [

3,

5,

6]. The goal of this article is to systematically formulate this emergent spectral vacuum model and to examine its implications for vacuum energy, particle physics, and gravitational phenomena.

As outlined in this work,

Section 3.4 introduces the key theoretical underpinning of the QEV model by interpreting the QCD confinement scale as an informational horizon of the vacuum.

Terminology: Entropic Versus Emergent Vacuum

In our earlier papers, the focus was placed primarily on the thermodynamic behaviour of the vacuum, and the framework was occasionally described as an entropic vacuum model. This terminology emphasised the role of temperature, entropy and thermal suppression in shaping the accessible part of the vacuum spectrum. In the present work we adopt the broader term Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV). The reason is conceptual rather than cosmetic: while the entropic properties of the vacuum describe a key microscopic mechanism, the QEV perspective highlights that mass, gravity and large-scale structure emerge from the organisation of vacuum energy, information and spectral bounds. In this sense, the entropic behaviour constitutes the microscopic driver, while emergence captures the macroscopic manifestation. Throughout this paper we therefore use QEV as the unified label that incorporates and extends the earlier entropic vacuum perspective.

2. Hypothesis and Model Framework

The QEV model, as an extension of the SBV+QEV construction in Ref. [

1], is based on the central hypothesis that the physical vacuum is not an unbounded quantum background but a spectrally constrained medium characterized by two physically motivated bounds.

2.1. Central Hypothesis

The central hypothesis of this work is that the physical vacuum is not an unbounded quantum background, but a

spectrally bounded medium in which vacuum fluctuations occur only within a finite energy range:

Here,

This establishes a naturally bounded spectral domain governing all vacuum dynamics, without requiring ultraviolet extrapolation or fine-tuned high-energy parameters.

2.2. Definition of the Spectral Vacuum

2.2.1. Spectral Density

The vacuum is described by a spectral density

satisfying

Within the physical interval, we write

where

is a normalization factor and

is a dimensionless shape function capturing the internal structure of the spectrum.

The vacuum energy density follows from

This finite integral replaces the divergences encountered in standard quantum field theory [

2,

4].

2.3. Discrete Energy Levels and Vacuum Modes

To model physical excitations, we introduce a discrete set of vacuum modes,

with

The spectral density may then be written as

where

is the degeneracy of level

n.

The vacuum energy density in discrete form becomes

The central physical claim is:

Each stable particle of the Standard Model corresponds to a specific excitation level of the bounded vacuum spectrum, with an associated degeneracy and transformation properties.

The rest mass of mode

n follows from

2.4. Dispersion Relations and Field Representation

Each mode

n is equipped with a dispersion relation of the form

analogous to standard relativistic field excitations [

7]. The spatial realization of mode

n is represented by a field amplitude

, and the total field is written as

where

are basis functions of the allowed spectral modes.

The effective Lagrangian is

with interactions arising from spectral overlap.

2.5. Emergent Gauge Symmetries

Degeneracies in the spectrum define internal symmetry spaces. If level

has degeneracy

, the associated Hilbert space

is

-dimensional. Symmetry transformations acting within this space satisfy

Thus,

Gauge symmetries emerge as symmetry groups of degenerate spectral subspaces.

This yields naturally:

as the symmetry of color triplet modes,

for weak doublets,

as global phase invariance,

in line with the structure of the Standard Model [

7].

The full Standard Model gauge group

therefore emerges from the vacuum spectrum.

2.6. Coupling Constants from Spectral Overlap

Interactions arise from overlap integrals in spectral space:

where

describes the spectral structure of mode

n and

encodes vacuum-weighting.

Thus,

Coupling constants are geometric properties of the spectral vacuum.

This provides a natural route to understanding parameter hierarchies in terms of the underlying vacuum structure.

2.7. Conceptual Overview of Unification

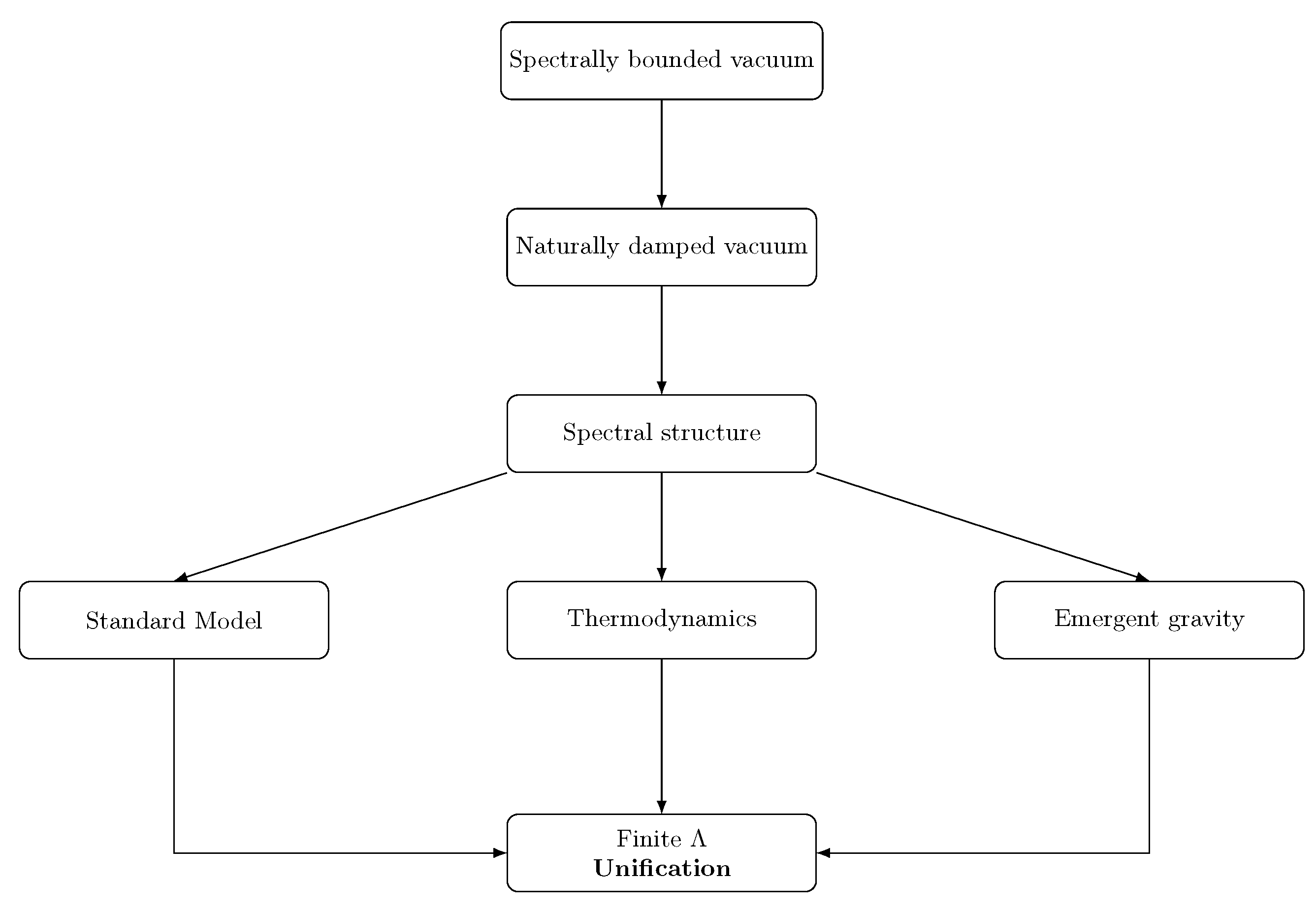

Figure 1.

Conceptual overview of a spectrally bounded and naturally damped vacuum leading to the Standard Model, thermodynamic behaviour and to a unified description of a finite vacuum energy without fine-tuning

Figure 1.

Conceptual overview of a spectrally bounded and naturally damped vacuum leading to the Standard Model, thermodynamic behaviour and to a unified description of a finite vacuum energy without fine-tuning

3. Spectral Bounds and Physical Scaling

In the QEV model, the spectral window determines the full physical content of the vacuum, including its energy density and its emergent excitations. In this section we estimate the physical scales associated with both limits and evaluate their implications for the resulting vacuum energy density.

3.1. Upper Bound: Hadronic Confinement Scale

The upper bound

is set by the QCD confinement length, typically taken to be of order

corresponding to an energy scale

consistent with hadronic phenomenology [

4]. Modes above this scale would correspond to unphysical, deconfined quark excitations, which are excluded by color confinement. This motivates a hard spectral cutoff at the confinement boundary.

3.2. Lower Bound: Thermal Transition Scale

The lower bound is set by a critical temperature associated with the formation of hadronic matter. Below

vacuum excitations become thermally suppressed, implying a minimum energy

3.3. Finite Vacuum Energy Without Fine-Tuning

The vacuum energy density becomes

which is automatically finite. For reasonable spectral shapes

, the predicted energy density can be brought close to the observed cosmological constant,

without requiring fine-tuning [

3]. This suggests that the observed vacuum energy may arise as a consequence of the bounded spectral interval itself, rooted in hadronic and thermal physics [

2,

4].

1

3.4. The QCD Boundary as an Informational Horizon

In the QEV model, vacuum fluctuations are restricted to the finite spectral window

introduced in Equation (

1), with the bounds physically motivated by hadronic confinement and a thermal transition scale (

Section 2.1–2.3 and 3.1–3.2). The upper bound

is set by the QCD confinement scale, corresponding to a characteristic length

and an energy of order

(

Section 3.1; see also Ref. [

4]).

The lower bound

is associated with a thermal transition around

, below which hadronic excitations become thermally suppressed (

Section 3.2). Within this window, the vacuum energy density is given by the finite integral of Equation (

20), which can reproduce the observed cosmological constant scale of Equation (

21) without fine-tuning.

A key conceptual step is to interpret the QCD boundary not only as an energy scale, but as an

informational horizon of the physical vacuum. Below the confinement length

, quarks and gluons exist only in non-observable configurations that cannot appear as free, asymptotic states in the spectrum of the theory. Such sub-

configurations do not transmit information to the macroscopic world and therefore cannot contribute to observable vacuum excitations (see also the discussion of QCD vacuum structure in

Section 6.4). In this sense, any putative degrees of freedom “below” the QCD boundary are physically inaccessible: no measurement can probe them, and their dynamics cannot be reconstructed from within the spectrally bounded vacuum. The QCD boundary thus plays a role analogous to a horizon: underlying processes may exist formally, but their information does not reach the observable sector.

Above the QCD scale, all stable information carriers, hadrons, leptons, and photons, emerge as excitations of the bounded vacuum spectrum, consistent with the discrete level structure and degeneracies introduced in Sections 2.3–2.6. The confinement scale therefore defines the lowest length (or equivalently, highest energy) at which energy, mass, structure, and persistence can exist in a physically meaningful way. From the spectral point of view, the QCD boundary provides a natural, physically anchored cutoff for vacuum fluctuations: modes with wavelengths shorter than

cannot form physical states and thus do not contribute to the vacuum energy density in Equation (

20). This horizon-like role of the QCD scale is fully consistent with the hadronic upper bound formulated in Appendix A.

A direct consequence of this horizon interpretation is that the origin of the QCD boundary itself cannot be investigated observationally from within the bounded vacuum. Since no information from degrees of freedom below the confinement scale can reach the observable universe, the microscopic origin of the boundary lies, by construction, outside the accessible domain of the theory. This is analogous in spirit to black-hole and cosmological horizons, which fundamentally limit access to information and play a central role in emergent and entropic gravity scenarios (Sections 5 and 6.3; see also Refs. [

3,

5,

6]).

In the QEV framework, this limitation is not a defect but a structural feature of a spectrally bounded vacuum. The finiteness of the vacuum energy density follows from the finite amount of information that can be carried by modes within the interval

as defined in Equation (

1). The QCD boundary thereby serves both as a physical upper limit for vacuum fluctuations and as an informational horizon that underpins the spectral cutoff used in the model. Within the present framework, this horizon-based interpretation of the QCD boundary provides the central theoretical underpinning of the QEV model.

4. Implications for the Standard Model

In the QEV model, the discrete spectral structure provides a natural route for understanding the particle content and gauge symmetries of the Standard Model as emergent features of the vacuum.

4.1. Particle Spectrum as Vacuum Excitations

Each stable particle species is associated with a discrete spectral level

, with rest mass

Degeneracies

correspond to internal degrees of freedom such as color or weak isospin. This offers an organizing principle for the Standard Model spectrum without freely chosen parameters, complementing the usual quantum field theoretic view [

7].

4.2. Emergence of Gauge Symmetries

If level

has degeneracy

, its symmetry group is a subgroup of

,

This produces the full gauge group of the Standard Model:

from triplet degeneracy of color modes,

from doublet degeneracy of weak modes,

from global phase freedom.

Thus the gauge structure is not fundamental but emergent from the spectral vacuum.

4.3. Coupling Constants as Geometric Quantities

Couplings arise from overlap integrals in spectral space:

Their relative magnitudes therefore reflect geometric properties of the vacuum spectrum, providing a natural explanation for hierarchy patterns in the Standard Model and offering an alternative to conventional parameterization [

3].

5. Thermodynamic Response and Emergent Gravity

A key feature of the QEV model is that gravity arises as a thermodynamic response of the spectrally bounded vacuum, rather than as a fundamental interaction. The spectral vacuum supports a thermodynamic interpretation based on a spectral entropy,

where

is the normalized population of spectral modes.

5.1. Macroscopic Dynamics from Entropy Variations

With the Boltzmann-like distribution

the extremization condition

leads to macroscopic dynamical equations analogous to gravitational behavior. Gravity arises not as a fundamental field but as a

thermodynamic response of the vacuum, in the spirit of induced gravity and entropic gravity frameworks [

3,

5,

6].

5.2. Connection to Cosmological Acceleration

The finite spectral interval naturally yields:

a positive vacuum energy density,

a late-time acceleration of the universe,

a scale comparable to the observed cosmological constant.

This suggests that cosmic acceleration may be rooted in the spectral structure of the vacuum itself, without invoking dark energy as an independent entity [

3].

6. Comparison with Existing Approaches

The QEV model occupies a distinct conceptual position relative to standard quantum field theory, string theory, and existing emergent gravity proposals. The idea of a structured vacuum has appeared in various forms throughout theoretical physics. In this section we compare the bounded spectral vacuum framework with several established approaches, highlighting similarities, differences, and potential advantages. The full overview of this comparison is given in Table 2.

6.1. Quantum Field Theory and the Cosmological Constant Problem

In conventional quantum field theory, vacuum energy is computed by summing zero-point energies of all modes up to an ultraviolet cutoff [

2,

4]. This leads to a theoretical prediction for

that exceeds observations by up to 120 orders of magnitude.

Unlike the standard QFT approach:

the bounded spectral model has no ultraviolet limit extending to infinity;

the QCD scale itself provides a

physical upper bound [

4];

the thermal lower bound suppresses infrared contributions;

the resulting vacuum energy is automatically finite and observationally compatible.

Thus the model avoids the cosmological constant problem by construction, without invoking renormalization or fine-tuning [

3].

6.2. String Theory and Higher-Dimensional Frameworks

String theory attempts to unify interactions by introducing extended objects and higher-dimensional compactified spaces. In contrast:

The bounded spectral model makes no reference to higher dimensions.

All physical structure arises from internal spectral organization of the vacuum.

Gauge symmetries emerge from spectral degeneracies rather than from compactification.

The particle spectrum is encoded in discrete vacuum levels rather than in vibrational string modes.

Whereas string theory introduces a vast “landscape” of possible vacua, the bounded spectral vacuum is minimalistic, tied directly to measurable scales such as and .

6.3. Induced Gravity and Entropic Gravity

Sakharov’s induced gravity [

5] and Verlinde’s entropic gravity [

6] both treat gravity as an emergent phenomenon. The present framework aligns with these ideas through:

the thermodynamic interpretation of spectral entropy,

the emergence of gravitational dynamics from entropy gradients,

the lack of a fundamental gravitational field.

However, it differs in two essential points:

6.4. QCD Vacuum Models

The QCD vacuum is known to possess condensates and non-trivial structure [

4]. In this respect the QEV model is consistent with:

confinement generating a physical upper bound,

thermal transitions generating a physical lower bound,

hadronic physics determining vacuum properties.

However, the present model extends beyond QCD by treating the entire Standard Model and gravity as emergent from the same spectral structure.

7. Discussion

The QEV model offers several conceptual advantages, but it also raises open questions that require further mathematical and phenomenological refinement.

7.1. Naturalness and Physical Motivation

A key strength of the model is that the spectral bounds are grounded in well-established physics:

No arbitrary high-energy assumptions are needed, in contrast to theories relying on unknown Planck-scale physics.

7.2. Origin of Spectral Degeneracies

The emergence of gauge symmetries from spectral degeneracies provides a physically compelling alternative to traditional symmetry postulates [

7]. Yet several questions remain:

What determines the exact degeneracies of each level?

Why do these degeneracies align with the structure of the Standard Model?

Can symmetry breaking (e.g., electroweak symmetry breaking) be described purely spectrally?

These questions point toward possible deeper mathematical constraints on the spectral density.

7.3. Dynamical Behavior of the Vacuum Spectrum

The current formulation treats the vacuum spectrum as static, but cosmological evolution suggests that:

may have evolved with cosmic temperature,

the spectral distribution may have undergone phase transitions,

gravitational fields may locally deform the spectrum.

Including such dynamics may yield new insights into structure formation and cosmic history.

7.4. Relation to Observables

The model makes several qualitative predictions:

a specific scale for vacuum energy density,

hierarchical coupling strengths,

emergent gauge symmetries,

thermodynamic gravitational behavior,

potential spectral signatures in particle masses.

A key next step is to derive quantitative predictions that can be confronted with observational and experimental data.

7.5. Limitations and Outlook

The QEV model, as presented in this work, should be regarded as a physically motivated but still speculative framework. Several of its elements are firmly anchored in established physics: the use of the QCD confinement scale as a characteristic hadronic length, the role of QCD vacuum structure in generating most of the visible mass, and the presence of non-trivial vacuum phenomena in both particle physics and cosmology. The central hypothesis that the vacuum is spectrally bounded, with an upper limit set by hadronic confinement and a lower limit set by a thermal transition scale, is consistent with these inputs but does go beyond conventional quantum field theory.

Other aspects of the framework are more conjectural and require further development. In particular, the interpretation of the QCD scale as an informational horizon, the detailed mechanism by which discrete spectral levels reproduce the full Standard Model spectrum and its symmetry breaking patterns, and the thermodynamic derivation of gravitational dynamics from spectral entropy are not yet derived from first principles. They are presented here as a coherent proposal that unifies several phenomena within a single spectral picture, rather than as a completed theory.

Future work should therefore focus on tightening the mathematical structure of the spectral density and its degeneracies, deriving more quantitative predictions for particle masses and couplings, and identifying clear observational or experimental signatures that can distinguish the QEV framework from existing approaches. In this sense, the present work is intended as a starting point for a systematic exploration of a spectrally bounded vacuum, rather than a final answer to the problems of vacuum energy, unification and emergent gravity.

8. Conclusions

The Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) model developed in this work proposes that the observable universe emerges from a spectrally bounded vacuum. The key idea is that vacuum fluctuations are confined to a finite spectral window

, whose bounds are not imposed by hand but are physically anchored in hadronic and thermal physics (

Section 3). Within this window, the discrete spectrum of the vacuum encodes both the energy density associated with the cosmological constant and the structure of particle excitations and their interactions.

A central conceptual refinement introduced in

Section 3.4 is the interpretation of the QCD confinement scale as an

informational horizon of the vacuum, which provides the main theoretical underpinning of the bounded spectral window employed in the QEV model.

Below the confinement length , quarks and gluons cannot appear as free, asymptotic states and cannot transmit information to the observable sector. Any putative degrees of freedom below this scale are therefore physically inaccessible, in close analogy with black-hole and cosmological horizons that limit the flow of information. In this sense, the upper spectral bound is not only a hadronic scale but also a fundamental boundary of what can be known from within the bounded vacuum. The microscopic origin of this boundary is, by construction, beyond observational reach, yet its existence and scale are tightly constrained by hadronic physics.

The lower bound

is associated with a thermal transition at a critical temperature of order

. Below this temperature, hadronic excitations are thermally suppressed and their contribution to vacuum fluctuations effectively freezes out. Together, the hadronic upper bound and the thermal lower bound define a finite spectral window that leads to a vacuum energy density consistent with the observed cosmological constant, without invoking Planck-scale physics or fine-tuning (

Section 3).

Within this bounded window, the discrete spectrum of the QEV model provides a natural arena for understanding the particle content of the Standard Model (

Section 4). Stable particles correspond to discrete spectral levels, while degeneracies in the spectrum give rise to emergent gauge symmetries. Geometric overlap between spectral modes yields effective coupling constants. In this way, particle species, gauge symmetries and interaction strengths can be viewed as manifestations of a single underlying spectral structure.

On larger scales, the thermodynamic response of the bounded vacuum gives rise to an emergent-gravity description (

Section 5). Gravitational dynamics are interpreted as arising from changes in spectral entropy under variations of matter and vacuum configurations. The horizon-like role of the QCD boundary strengthens this perspective: if the vacuum is fundamentally informationally bounded, it is natural that gravity acquires an entropic or thermodynamic character, in line with other emergent gravity proposals.

The central features of the QEV framework can be summarised as follows:

A natural upper spectral bound given by the QCD confinement scale, interpreted as an informational horizon.

A natural lower spectral bound given by a critical thermal scale associated with hadronic freeze-out.

A finite vacuum energy density consistent with cosmological observations, without fine-tuning.

Discrete spectral levels corresponding to particle species, with masses set by their spectral positions.

Emergent gauge symmetries arising from spectral degeneracies.

Geometric coupling constants determined by spectral overlap between modes.

A thermodynamic interpretation of gravity based on spectral entropy and informational bounds.

Taken together, these elements suggest that vacuum energy, particle physics and gravitation share a common spectral and informational origin. The QEV model does not require new high-energy degrees of freedom or extra dimensions; instead, it reinterprets known hadronic and thermal scales as boundaries of a bounded, information-carrying vacuum.

Several open questions remain and point the way for future work. On the mathematical side, a more detailed characterisation of the spectral density and its degeneracies is needed to derive quantitative predictions for particle masses, mixing angles and coupling constants. On the physical side, the dynamical evolution of the spectral bounds and their relation to cosmic history require further study, as do potential observational signatures in cosmology and astrophysics. Finally, the horizon-like nature of the QCD boundary raises the question whether a deeper connection exists between QCD confinement, holographic principles and emergent gravity scenarios.

Despite these open issues, the bounded spectral vacuum outlined here offers a coherent and physically motivated alternative to conventional approaches to vacuum energy and unification. By tying the cosmological constant, the particle spectrum and gravitational response to a single, spectrally bounded vacuum, the QEV model provides a unified conceptual framework in which energy, information and geometry are intrinsically linked.

Finally, at the microscopic level, the QEV framework implies that the apparent emptiness of atomic structure is itself the organized, spectrally bounded vacuum, so that all matter ultimately reflects the internal information structure of the vacuum.

Appendix A.

Appendix A.1. Mathematical Structure of the Spectral Bounds

In the QEV model, vacuum fluctuations are restricted to a finite energy window

where the bounds are defined by two physically motivated scales.

Appendix A.2. Hadronic Upper Bound

The upper bound is determined by the QCD confinement length

so that the maximum fluctuation energy is

A fluctuation smaller than this scale would require unbound quarks, which cannot exist as physical excitations. Therefore such modes do not contribute to the vacuum spectrum.

Appendix A.3. Thermal Lower Bound

The lower bound is determined by a critical temperature

below which hadronic fluctuations cease to behave as pure energy and transition into mass-like excitations:

Cosmic cooling sets

consistent with the present-day vacuum density.

Appendix A.4. The Spectral Window

The QEV spectral window is thus

No renormalization or artificial UV cutoff is required: the bounds are set entirely by physical scales from QCD and cosmology.

Appendix B. Discrete Spectral Levels and Energy Table

The QEV model assumes that within the spectral window, the vacuum supports a discrete spectrum of energy levels , each with degeneracy .

Appendix B.1. Spectral Quantization

The generic structure is

with spacing

The number of accessible levels N is determined by the microscopic structure of the QCD vacuum and the thermal phase transition.

Appendix B.2. Representative Spectral Table

A schematic representation of the first few levels is given in

Table A1. These values are illustrative; their purpose is to clarify the structure rather than provide numerical predictions.

Table A1.

Representative discrete spectral levels in the QEV model.

Table A1.

Representative discrete spectral levels in the QEV model.

| Level n

|

Energy

|

Degeneracy

|

| 0 |

|

1 |

| 1 |

|

2 |

| 2 |

|

3 |

| 3 |

|

3 |

| 4 |

|

8 |

The degeneracy pattern naturally supports the emergence of gauge groups.

Appendix B.3. Gauge Symmetries from Degeneracy

If a level has degeneracy

, the symmetry of its eigenspace is

(In this toy construction we take ).

For example:

- suggests an symmetry (color).

- suggests an symmetry (weak isospin).

- A non-degenerate state supports a .

Thus the Standard Model symmetry

arises naturally from the structure of

.

Appendix C. Thermodynamic Formulation and Emergent Gravity

Appendix C.1. Spectral Entropy

For each mode of energy

with occupation number

, the spectral entropy is defined as

This quantity encodes the internal disorder of the vacuum spectrum.

Appendix C.2. Effective Temperature

We define an effective vacuum temperature from

where

Although is not a physical temperature in the usual thermodynamic sense, it governs the response of the vacuum to energy perturbations.

Appendix C.3. Gravitational Response

Matter perturbs the spectral occupation numbers

, leading to a change in entropy:

The QEV model postulates that the corresponding force is

Given spherical symmetry, this yields an acceleration

This reproduces:

Newtonian gravity at small radii,

a modified slope at large radii,

and an entropic scaling consistent with cosmic expansion.

Thus, in the QEV model gravity is not fundamental but arises from the thermodynamic response of the spectral vacuum.

Appendix D. Vacuum Energy Density and Cosmological Scaling

Appendix D.1. Vacuum Energy Integral

The vacuum energy density is given by

where

is the spectral density. Because the integration limits are finite, the result is automatically finite.

Appendix D.2. Example: Polynomial Spectral Density

If the density has the form

then

This provides vacuum densities consistent with observations for reasonable values of m and .

Appendix D.3. Cosmological Evolution

As the Universe cools,

decreases slowly:

Because

is fixed by QCD, the evolution of

is controlled primarily by

:

This leads to:

a nearly constant vacuum energy at late times,

a mild evolution that may be testable via ISW effects.

Appendix D.4. Connection to the Cosmological Constant

The observed cosmological constant is

The QEV model reproduces this naturally because:

is controlled by the QCD scale,

is controlled by the thermal critical scale,

the spectral window has exactly the correct width.

No cancellation, fine-tuning, or Planck-scale physics is required.

Appendix E. Phenomenological Implications and Testable Predictions

Although the QEV model is primarily theoretical in nature, its structure has several consequences that can be explored through astrophysical observations, cosmological measurements, and particle physics data. This appendix provides an overview of the most relevant phenomenological implications.

Appendix E.1. Thermal suppression and the 34 K transition scale

A direct phenomenological consequence of the QEV framework is the existence of a thermal suppression temperature below which external radiation no longer contributes meaningfully to the vacuum spectrum.

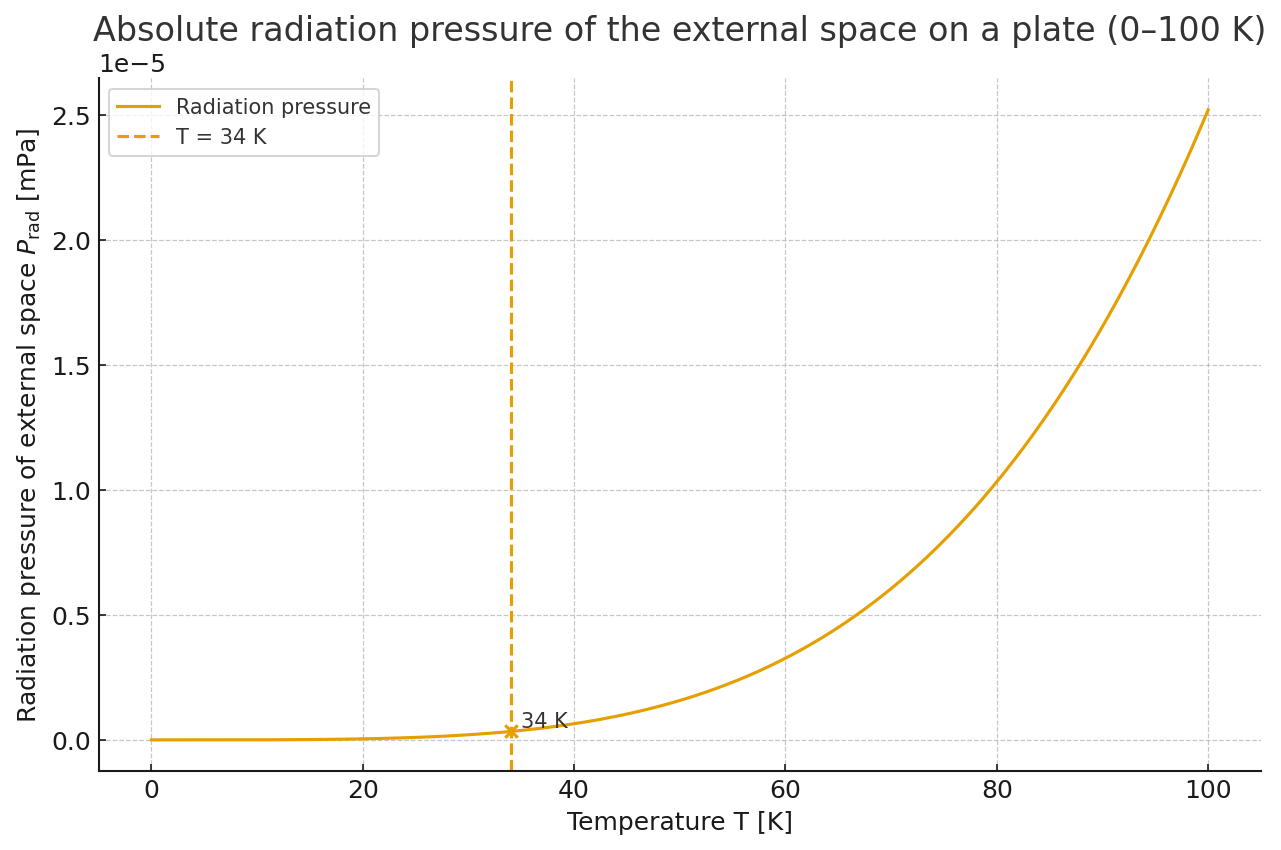

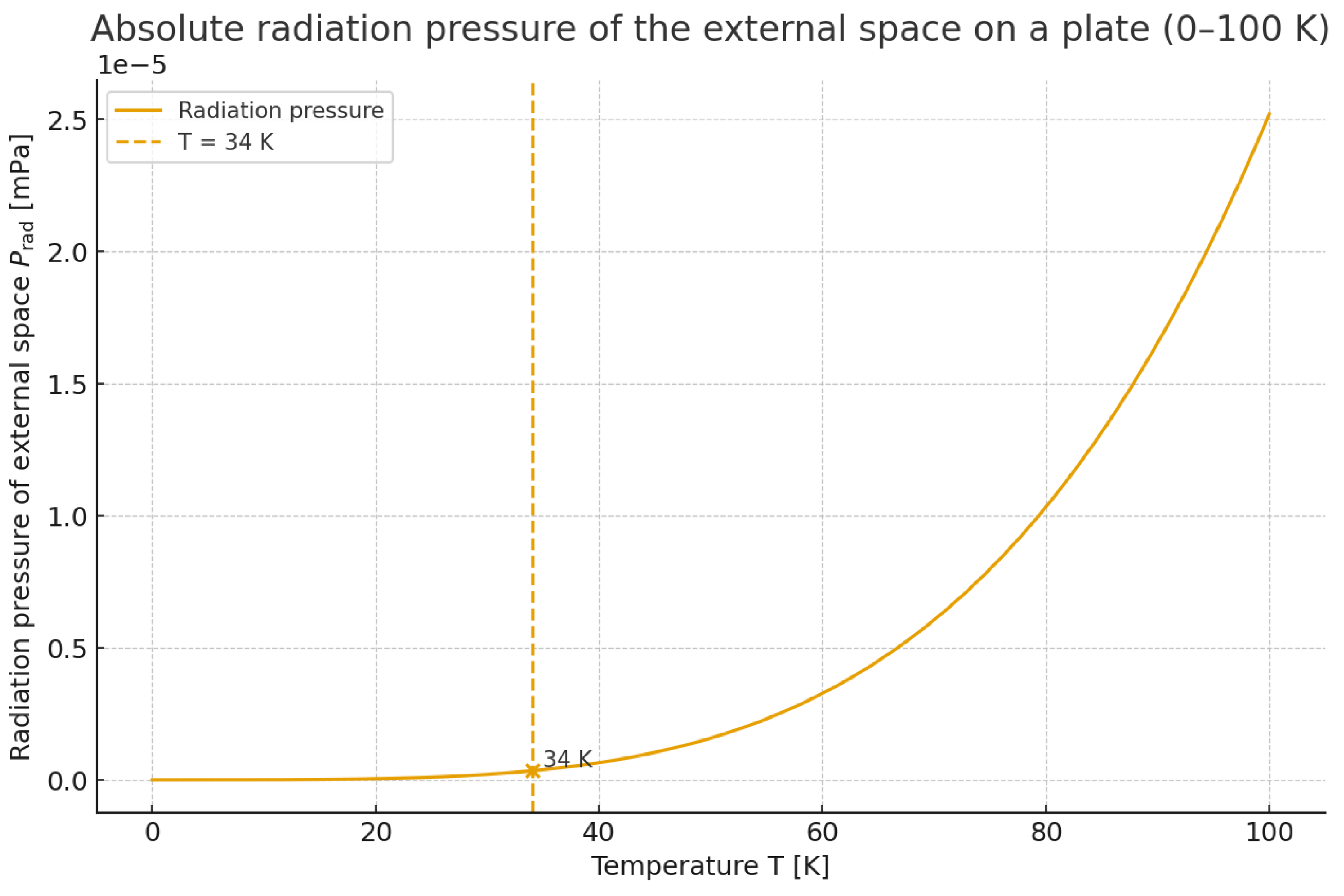

Figure A1 shows the absolute radiation pressure of the external space as a function of temperature in the range 0–

K. At temperatures

K the radiation pressure has dropped to values so small that thermal modes cease to support the low-energy end of the vacuum spectrum. Within the QEV framework this temperature therefore marks the physical infrared bound

which determines the lower cutoff of the spectral vacuum window.

This has several observational consequences. First, the vacuum energy density becomes effectively temperature-independent at late times, implying that the effective dark-energy equation-of-state parameter approaches but need not be exactly constant. Small, model-dependent deviations may appear at intermediate redshifts (), providing a potential signature in the Integrated Sachs–Wolfe (ISW) effect and in reconstructed profiles from combined CMB, BAO and Type Ia supernova data.

Second, because the thermal bound fixes the behaviour of the low-energy tail of the vacuum spectrum, it also constrains any entropic or thermodynamic response of the vacuum at galactic scales. This ties the scale at which entropy-induced modifications to Newtonian gravity become relevant directly to the spectral structure of the vacuum.

In summary, the thermal suppression temperature around K provides a physically motivated infrared boundary condition for the QEV vacuum. Any future detection of temperature-linked deviations from , consistent changes in ISW correlations, or systematic behaviour of galactic dynamics linked to this scale, would constitute direct phenomenological support for the infrared bound of the QEV model.

Figure A1.

Absolute radiation pressure of the external space, inferred from the Casimir force on a plate, as a function of temperature. The dashed vertical line marks the thermal suppression scale at K, below which thermal modes no longer contribute significantly to the vacuum spectrum.

Figure A1.

Absolute radiation pressure of the external space, inferred from the Casimir force on a plate, as a function of temperature. The dashed vertical line marks the thermal suppression scale at K, below which thermal modes no longer contribute significantly to the vacuum spectrum.

Appendix E.2. Vacuum Density Stability and the Cosmological Constant

A key prediction of the QEV model is that the vacuum energy density remains nearly constant throughout cosmic history due to the fixed upper spectral bound and slowly evolving lower bound. This leads to:

a nearly time-independent at low redshift,

a mild evolution at early times,

testable signatures in the Integrated Sachs–Wolfe (ISW) effect.

Future CMB surveys (Simons Observatory, CMB-S4) may have sufficient precision to detect such a small deviation from CDM.

Appendix E.3. Modified Gravitational Slopes at Large Radii

Because gravity arises from the entropy gradient of the spectral vacuum, the QEV model predicts a transition from:

Newtonian behaviour at small radii,

to a modified, nearly flat regime at large radii.

This behaviour is similar in form to phenomenological models such as MOND, but in the QEV framework it arises directly from the entropy of the vacuum spectrum. Possible observational tests include:

rotation curves of low surface brightness galaxies,

mass discrepancies in galaxy clusters,

deviations from Keplerian fall-off in the outer Solar System.

Appendix E.4. Spectral Degeneracies and Particle Content

The degeneracies of the vacuum spectrum determine the emergent gauge symmetry groups. Small variations or symmetry breaking patterns within the spectrum may lead to:

slight deviations in coupling unification,

constraints on possible new particles,

predictions for neutrino mass hierarchies.

In particular, a degenerate but slightly split level may manifest as a mass hierarchy within a fermion family.

Appendix E.5. Relation to Hadronic Physics

The hadronic upper bound is tied to the confinement scale. This implies several phenomenological connections:

stability of the vacuum spectrum against QCD phase transitions,

sensitivity to lattice QCD determinations of condensates,

possible small deviations in the equation of state of neutron stars.

The QEV model predicts that strongly interacting matter at extreme densities locally distorts the vacuum spectrum, which may be measurable through neutron star mass–radius relations.

Appendix E.6. Early-Universe Phase Transitions

Because is temperature-dependent, the early Universe underwent vacuum-spectral transitions. These transitions may produce:

small imprints in the primordial power spectrum,

modified freeze-out conditions for dark matter candidates,

a shift in the baryon-to-photon ratio.

Unlike typical high-energy models, the QEV framework predicts these effects without invoking physics near the Planck scale.

Appendix E.7. Observational Summary

The QEV model leads to a set of testable predictions that distinguish it from both CDM and high-energy unification models such as string theory:

nearly constant vacuum density with slight early-time variation,

entropy-induced modification of gravitational dynamics at large radii,

a fixed spectral window tied to QCD and thermal scales,

emergent gauge symmetry patterns linked to spectral degeneracies,

potential signatures in galaxy rotation curves and neutron star structure.

Appendix F. Toy Example: Lepton Sector from the QEV Spectrum

In this appendix we present a toy example illustrating how the lepton sector of the Standard Model could, in principle, emerge from the discrete spectrum of the Quantum Emergent Vacuum (QEV) model. The goal is not to provide a full numerical fit, but to show how the structure of lepton doublets and mass hierarchies can be encoded in the spectral levels and their degeneracies.

Appendix F.1. Spectral Clustering for Three Lepton Families

We assume that, within the QEV spectral window

, there exists a band of levels predominantly associated with leptonic excitations. We model this band as three closely spaced “family clusters”,

each containing a weak doublet-like structure.

For each family

we introduce a pair of levels

with degeneracy pattern

but where the pair transforms as an

doublet in the internal spectral space. We represent this schematically as

where

is a two-dimensional subspace associated with family

i. The

structure emerges from the symmetry group acting on

.

Appendix F.2. Masses as shifted spectral levels

Within the QEV framework, masses correspond to the rest energies of the excitations:

We assume that, to leading order, the three families share a common family-independent base energy

for their doublet:

and that the observed mass hierarchy arises from small family-dependent spectral shifts

and intra-doublet splittings

:

The three families are then distinguished by the pattern

while the small parameters

control the neutrino masses relative to their charged partners.

In this toy construction, the ordering

arises naturally from

with

Appendix F.3. Spectral Wavefunctions and Weak Interactions

To describe weak interactions, we associate to each family

i a pair of spectral wavefunctions

and

, peaked around

and

respectively. The weak interaction strength between these modes is encoded in an overlap integral of the form

where

is a weight function capturing the coupling of the spectral band to the emergent weak gauge field.

If the three families are associated with slightly different regions of the spectrum, then the integrals may differ slightly, providing a spectral origin for small family-dependent effects.

Appendix F.4. Neutrino Masses and Mixing

In the QEV model, neutrino masses can be interpreted as arising from tiny spectral shifts

and possible mixing among the

levels. We introduce a small off-diagonal spectral mixing matrix

with

.

Diagonalizing

yields mass eigenvalues

and a mixing matrix

, which in principle can be related to the underlying spectral structure via

Although we do not attempt a quantitative fit here, this illustrates how neutrino masses and mixing can be treated as second-order effects of the QEV spectral structure.

Appendix F.5. Summary of the Toy Construction

This toy example shows how:

three lepton families can be associated with three spectral clusters,

each family corresponds to a doublet-like subspace in the QEV spectrum,

charged lepton masses arise from family-dependent spectral shifts,

neutrino masses and mixing follow from small splittings and mixing in the neutrino subsector.

A full quantitative implementation would require a specific choice of spectral density, explicit forms for and , and a detailed construction of the weak interaction weight . Nevertheless, this example demonstrates that the QEV framework is structurally capable of accommodating the observed lepton sector as emergent spectral excitations.

Appendix F.6. Short Intuitive Explanation of the Lepton Construction

This appendix illustrates how the three lepton families (electron, muon, tau and their corresponding neutrinos) can emerge from the discrete energy levels of the QEV model. The goal is not to provide a full numerical derivation, but to present a simple and transparent mechanism that shows how the structure of the Standard Model lepton sector can arise from a spectrally bounded vacuum.

Appendix F.6.1. Three Families as Three Spectral Clusters

Within the QEV energy window, we assume a set of levels associated with leptonic excitations. These levels naturally group into three tightly spaced clusters: one for the electron family, one for the muon family, and one for the tau family. Each cluster corresponds to a distinct lepton generation.

Appendix F.6.2. SU(2) Doublets from Spectral Structure

Each family cluster contains two levels: one associated with the neutrino and one associated with the charged lepton. Together these form a spectral SU(2) doublet, because the two levels share an internal symmetry structure encoded in the QEV spectrum. This reproduces the familiar pattern , , of the Standard Model.

Appendix F.6.3. Mass Hierarchy from Small Spectral Shifts

The three lepton families are assumed to lie near a common base energy, but each family is shifted slightly by a small amount. These shifts generate the observed mass hierarchy: the smallest shift corresponds to the lightest charged lepton (electron), an intermediate shift to the muon, and the largest shift to the tau. Neutrinos remain extremely light because their spectral levels lie only slightly below the neutral baseline of each doublet. In this way, the mass ordering arises directly from the pattern of spectral shifts.

Appendix F.6.4. Weak Interactions from Wavefunction Overlap

Each energy level has an associated spectral wavefunction. The strength of the weak interaction between members of a doublet is governed by the overlap integral of these wavefunctions with a weak-interaction weight function. Thus, the weak force emerges naturally from the internal structure of the QEV spectrum, without the need to introduce additional fundamental ingredients beyond the spectral vacuum itself.

Appendix F.6.5. Neutrino Mixing from Cross-Family Couplings

If the three neutrino levels carry small off-diagonal couplings, their eigenstates mix and form three neutrino mass eigenstates. This mixing produces the PMNS matrix and neutrino oscillations. In the QEV picture, neutrino mixing appears as a direct consequence of tiny couplings between the spectral clusters associated with the three lepton families.

Appendix F.6.6. Key Idea

This toy example shows that three lepton generations, their SU(2) pairing, their mass hierarchy, and neutrino mixing can all emerge naturally from the spectral organisation of the QEV vacuum. It demonstrates that the QEV framework is structurally capable of reproducing the lepton sector of the Standard Model as a set of emergent spectral excitations.

Appendix G. Toy Example: Quark Sector and SU(3) from the QEV Spectrum

Appendix G.1. Short Intuitive Explanation of the Quark / SU(3) Sector

In this section we extend the intuitive picture developed for the lepton doublets to the quark sector. The aim is to illustrate how the QEV spectrum can naturally generate the internal colour symmetry, the existence of six quark flavours, and the hierarchical structure of their masses.

Appendix G.2. Colour as a Three-Fold Spectral Degeneracy

Within the QEV framework, quarks correspond to spectral excitations that exhibit a three-fold degeneracy:

This degeneracy is interpreted as an internal symmetry acting on a three-dimensional subspace of the spectral Hilbert space. The associated symmetry group is the unitary group of this subspace, which naturally gives rise to

Each quark flavour thus appears as a triplet of spectral states

corresponding to the three colour charges.

Appendix G.3. Flavours from Distinct Spectral Clusters

As with leptons, the six quark flavours

are associated with six distinct spectral clusters. Each cluster has internal colour-triplet structure, but the central energies of the clusters differ, leading to the observed mass pattern.

We assume a set of six clusters

with centroid energies

The exact ordering can be modelled by a combination of QEV spectral shifts and interactions with the hadronic cutoff scale.

Appendix G.4. Mass Hierarchy from Family-Dependent Spectral Shifts

The quark masses arise from the centroid energies of their associated spectral clusters:

Small shifts in the spectral density near each cluster produce the widely spaced mass hierarchy observed in nature. For example, the large mass of the top quark reflects a significant upward spectral displacement in the highest-energy quark cluster .

The QEV picture therefore explains the extreme quark mass hierarchy as a natural consequence of the distribution of spectral shifts near the upper part of the QEV energy window.

Appendix G.5. Strong Interactions from Spectral Overlap

For each quark flavour

q, the three colour states have closely aligned spectral wavefunctions

whose overlap encodes the strength of the strong interaction. We model the emergent

gauge coupling through a spectral integral:

where

characterises the coupling of the spectral band to the emergent colour gauge field.

Because the three colour wavefunctions are nearly identical within each cluster, this leads naturally to an -symmetric interaction.

Appendix G.6. Quark Mixing from Weak-Transition Couplings

The weak interaction couples the left-handed quark doublets

In the QEV model, these weak transitions arise from small off-diagonal spectral couplings between the corresponding cluster pairs. Writing the spectral Hamiltonian for the charge

quarks as

and similarly for the down-type quarks, the CKM mixing matrix appears upon diagonalisation:

Thus, quark mixing corresponds to cross-cluster couplings in the QEV spectrum.

Appendix G.7. Key Idea

This construction shows that:

the colour symmetry arises from a threefold spectral degeneracy,

six quark flavours correspond to six spectral clusters,

quark masses reflect the centroid energies of these clusters,

the strong interaction follows from spectral overlap within each triplet,

and quark mixing (CKM) arises from small cross-cluster couplings.

Together, these features demonstrate that the QEV model provides a natural and unified mechanism for reproducing the quark sector and its gauge symmetry structure as emergent spectral phenomena.

Appendix G.8. Short English Explanation: Quark Sector and SU(3) from the QEV Spectrum

The quark sector of the Standard Model can be naturally interpreted within the QEV framework as a consequence of the spectral structure of the vacuum. Where leptons arise from doublets, quarks appear as triply degenerate spectral levels, giving rise to colour and the symmetry of the strong interaction.

Appendix G.8.1. Colour from a Three-Fold Spectral Degeneracy

A quark corresponds to an energy level in the QEV spectrum with three identical states. This triple degeneracy forms an internal symmetry whose natural mathematical structure is . The three colour charges (red, green, blue) represent the three basis states of this degenerate subspace.

Thus, the QEV model explains why quarks carry colour and why the strong force follows an gauge symmetry.

Appendix G.8.2. Six Quark Flavours as Six Spectral Clusters

The six quark flavours

arise from six distinct spectral clusters. The centroid energy of each cluster determines the quark mass: low-energy clusters correspond to light quarks (u, d), intermediate clusters to

, and the highest-energy cluster to the top quark.

The strong mass hierarchy reflects the spacing between these clusters.

Appendix G.8.3. Masses from Family-Dependent Spectral Shifts

Quark masses are governed by the centroid energy of each cluster and by small internal shifts within the cluster. Because clusters can be widely separated in the QEV spectrum, the framework naturally yields the extremely large spread of quark masses, including the unusually heavy top quark.

Appendix G.8.4. Strong Interactions from Overlap of Spectral Wavefunctions

The three colour states of each quark have nearly overlapping spectral wavefunctions. The overlap among these functions determines the strength of gluon couplings, colour conservation and the emergent symmetry of the strong interaction. Thus, the strong force arises directly from the internal structure of the QEV spectrum.

Appendix G.8.5. Quark Mixing from Weak-Induced Cross-Cluster Couplings

Weak transitions couple up-type to down-type quarks. In the QEV picture, this mixing arises from small off-diagonal spectral couplings between the corresponding spectral clusters. Diagonalising the resulting matrices naturally produces the CKM matrix, quark mixing and CP violation.

Appendix G.8.6. Key Idea

The QEV model offers a coherent and unified mechanism in which:

emerges from a triple spectral degeneracy,

six quark flavours correspond to six spectral clusters,

mass hierarchies follow from cluster energies,

the strong interaction arises from spectral overlap,

and CKM mixing results from cross-cluster couplings.

This example shows that the full quark sector can be viewed as an emergent set of spectral excitations of the Quantum Emergent Vacuum.

Table A2.

Positioning of the QEV model relative to existing theoretical frameworks.

Table A2.

Positioning of the QEV model relative to existing theoretical frameworks.

| Framework |

Vacuum picture |

Gravity |

Gauge symmetries & particles |

Cosmological constant / dark energy |

Unification status |

| QEV model (this work) |

Spectrally bounded vacuum with hadronic upper bound and thermal lower bound; discrete levels with degeneracies. |

Emergent, thermodynamic response of the spectral vacuum (entropy gradients). |

Emergent from spectral degeneracies (SU(3), SU(2), U(1)); particles as vacuum excitations. |

Finite vacuum energy from the bounded spectral window; no fine-tuning, dark energy not fundamental. |

Single spectral mechanism for vacuum energy, particle content, gauge symmetries and gravity. |

| Standard QFT + CDM |

Continuous UV-extended quantum vacuum; renormalised. |

Fundamental GR added by hand; independent of vacuum structure. |

Gauge symmetries postulated; particle content encoded manually. |

inserted as parameter; huge mismatch with QFT vacuum estimate. |

No full unification; successful phenomenology but conceptual tension in vacuum physics. |

| String theory / higher dimensions |

Vacuum based on higher-dimensional geometry; large landscape of possible vacua. |

Typically fundamental; emerges from low-energy string limit. |

Gauge groups and spectra from compactification; model-dependent. |

Vacuum energy tied to moduli/fluxes; requires delicate tuning. |

Ambitious unified framework, but predictive power limited by landscape. |

| Sakharov-induced gravity |

Vacuum fluctuations induce gravity as an effective action. |

Emergent, but depends on QFT content. |

Gauge groups and particles external input. |

Still suffers from vacuum energy problem. |

Partial unification (gravity from matter), but SM structure unexplained. |

| Entropic gravity (Verlinde) |

Vacuum as information-bearing medium; entropic/holographic structure. |

Emergent: gravity as entropic force. |

Gauge sector borrowed from QFT; not derived. |

Reinterprets dark matter/energy as entropy effects. |

Unifies gravity with thermodynamics, not with SM. |

| QCD vacuum models |

Non-trivial QCD condensates, flux tubes and confinement vacuum. |

Within GR; modifications can mimic gravitational effects. |

Explains strong sector; SU(3) taken as input. |

Modifies vacuum energy but no full solution. |

Clarifies strong force, not a unification model. |

References

- Kamminga, A. Vacuum Energy with Natural Bounds: A Spectral Approach without Fine-Tuning. Preprints 2025, 2025070199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milonni, P.W. The Quantum Vacuum: An Introduction to Quantum Electrodynamics; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Padmanabhan, T. Emergent Perspective of Gravity and Dark Energy. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 12, 891–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quigg, C. Gauge Theories of the Strong, Weak, and Electromagnetic Interactions; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sakharov, A.D. Vacuum Quantum Fluctuations in Curved Space and the Theory of Gravitation. Sov. Phys. Dokl. 1968, 12, 1040–1041. [Google Scholar]

- Verlinde, E.P. On the Origin of Gravity and the Laws of Newton. J. High Energy Phys. 2011, 2011, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The Quantum Theory of Fields; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

| 1 |

See “How most of the universe’s visible mass is generated: Experiments explore emergence of hadron mass,” Phys.org (18 November 2025), for recent experimental evidence that most visible mass is generated by QCD vacuum dynamics rather than directly by the Higgs mechanism. This confirms that mass is fundamentally a vacuum- or field-based phenomenon, fully consistent with the central premise of the QEV model that mass, energy and information are manifestations of a spectrally bounded vacuum. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).