Submitted:

20 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Self-Repeating Morphologies

1.2. Utility and Resilience

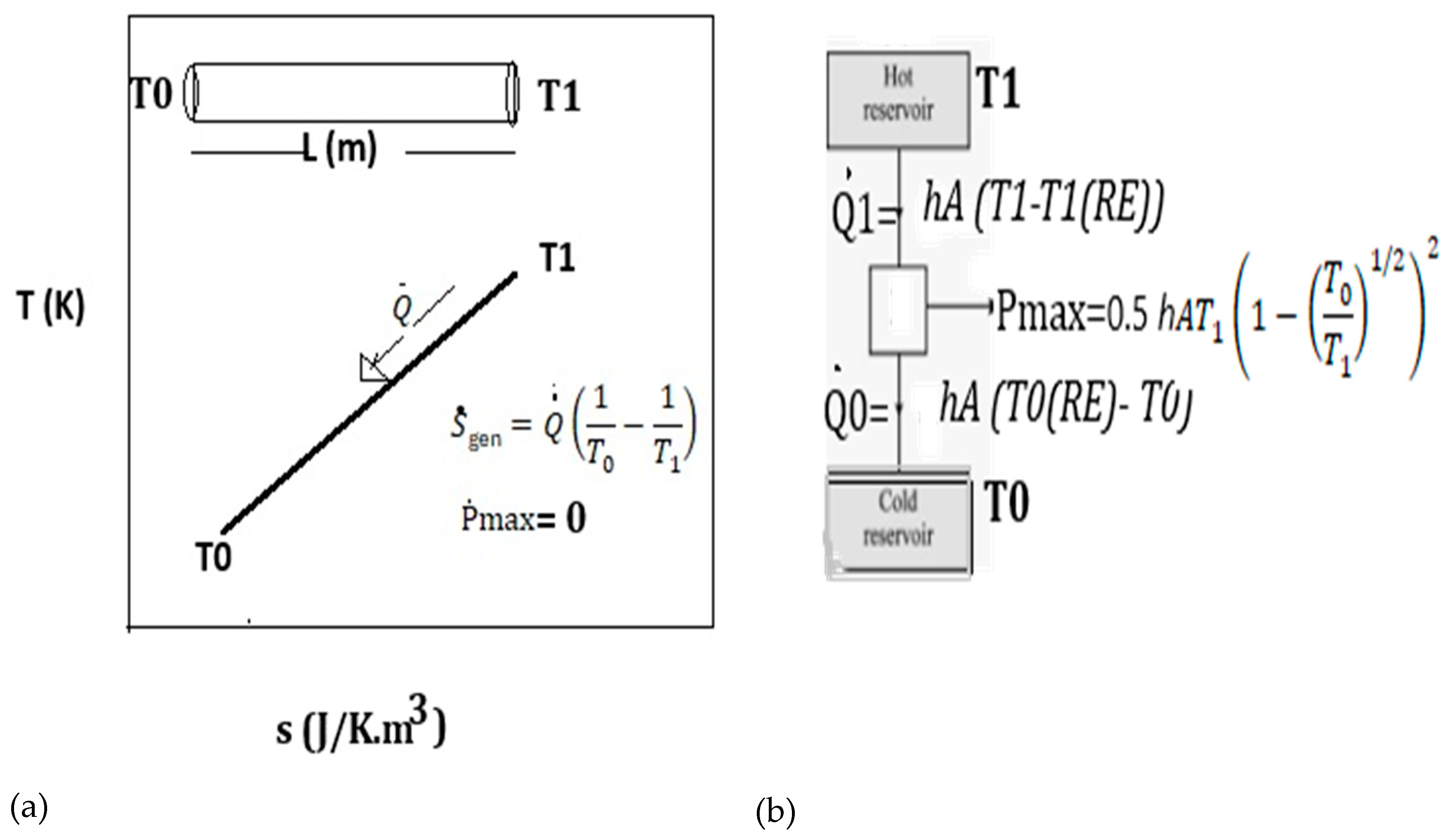

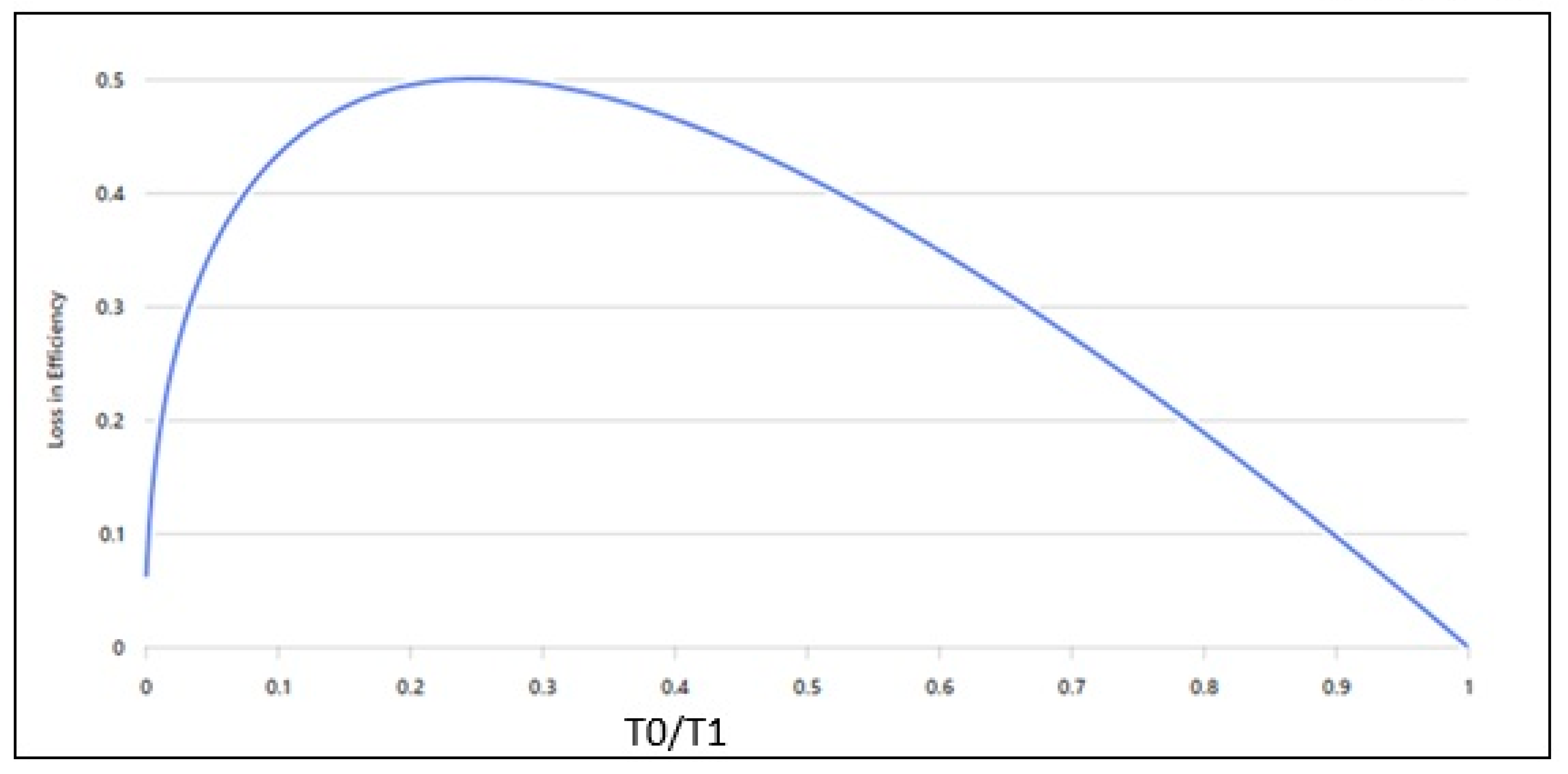

2. Insights into Irreversible Processes, Work, and the Entropy Generation Rate in Classical Thermodynamic Formulations

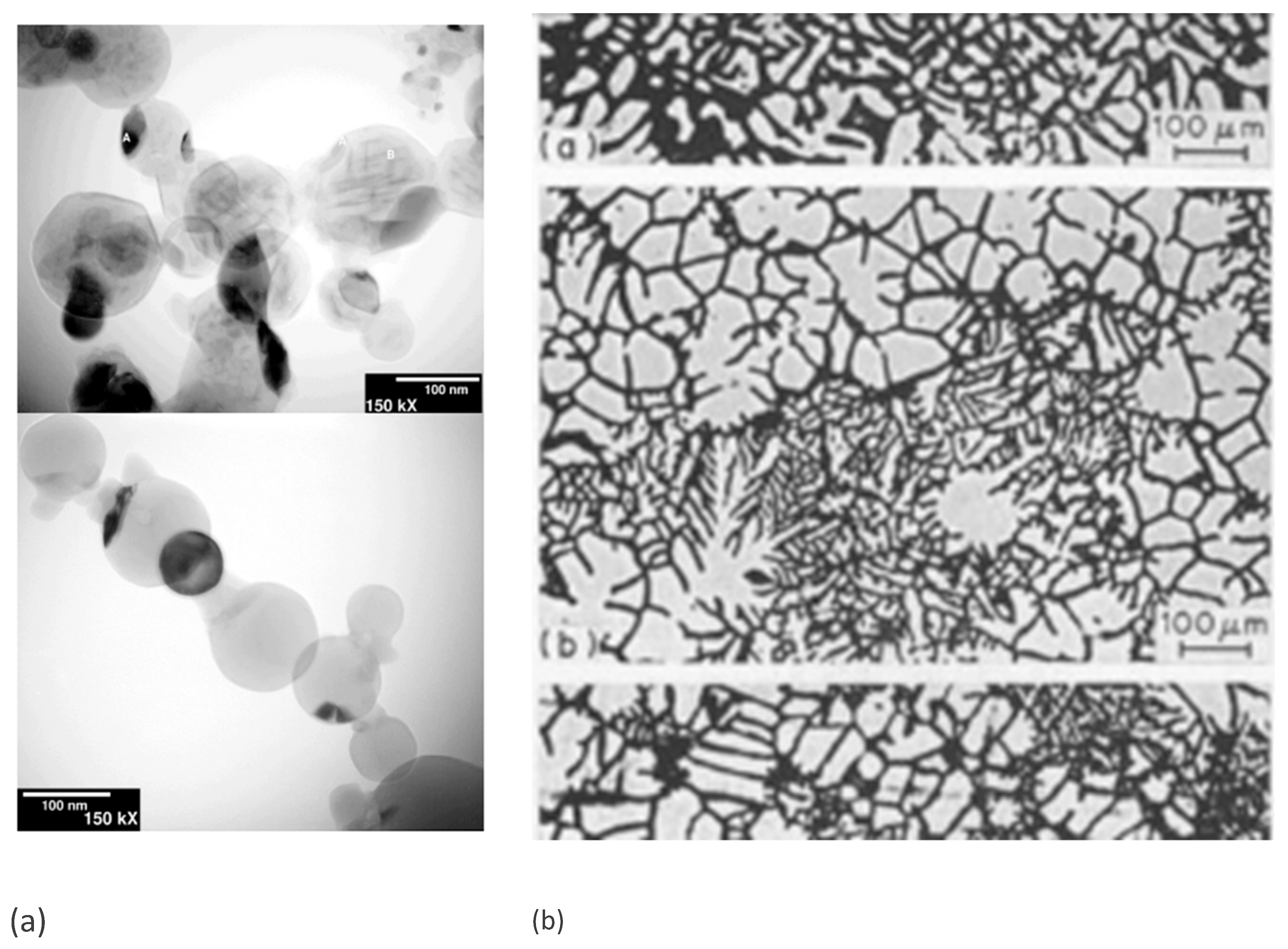

3. Validations MEPR (Maximum Entropy Production Rate) for Self-Organization, Entropy Generation Rate, and Boundary Defects: Fluid Eddies, Solidification, Microstructure, and Particle Sintering Behavior

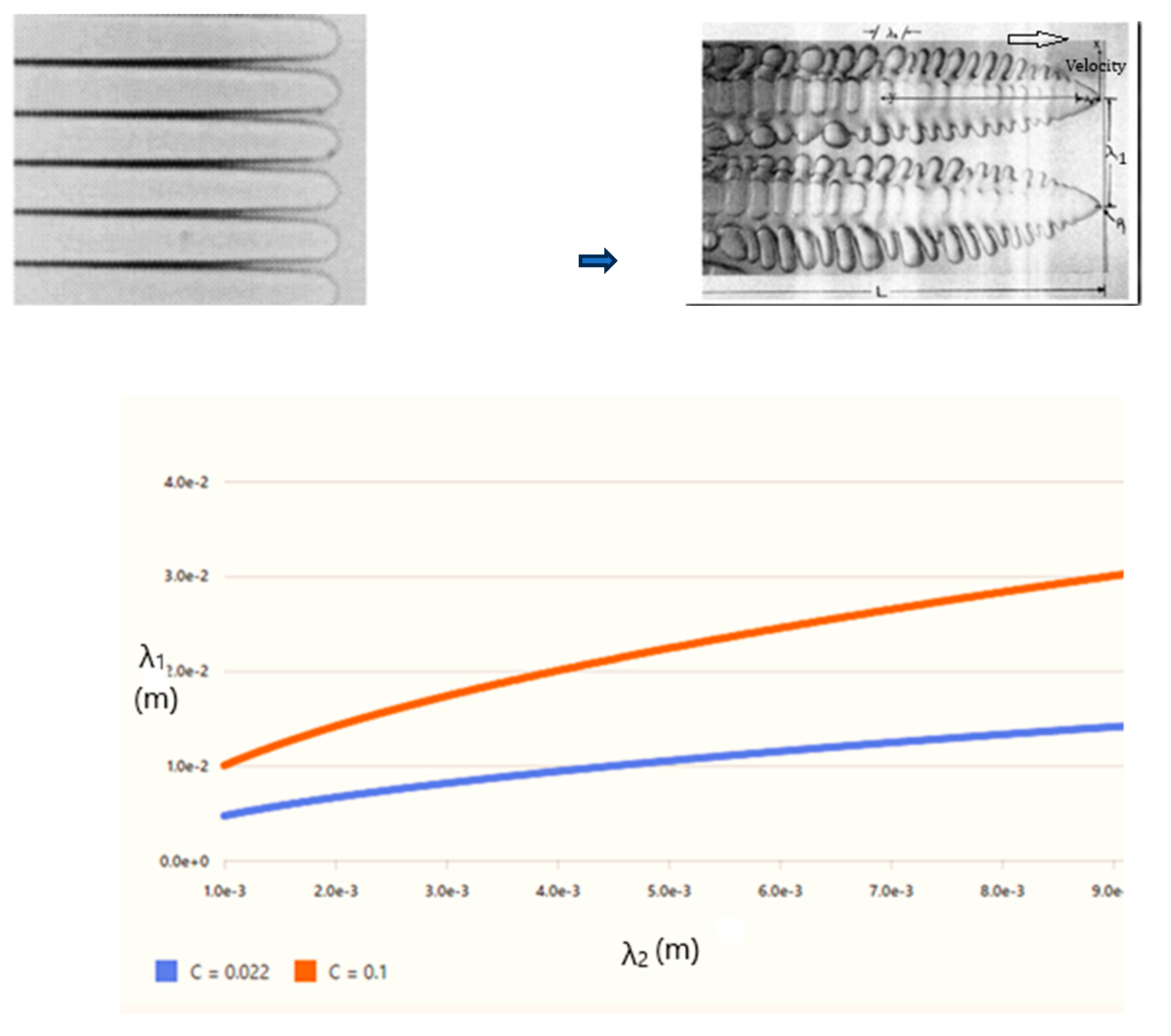

3.1. Minimum Size for Turbulent Eddies and Solidification Morphologies

3.2. Sintering and Densification

4.0. Ease of Computation with the MEPR Condition for Steady State and Non-Steady State Self-Organization

4.1. Morphological Transition Modeling at Steady State

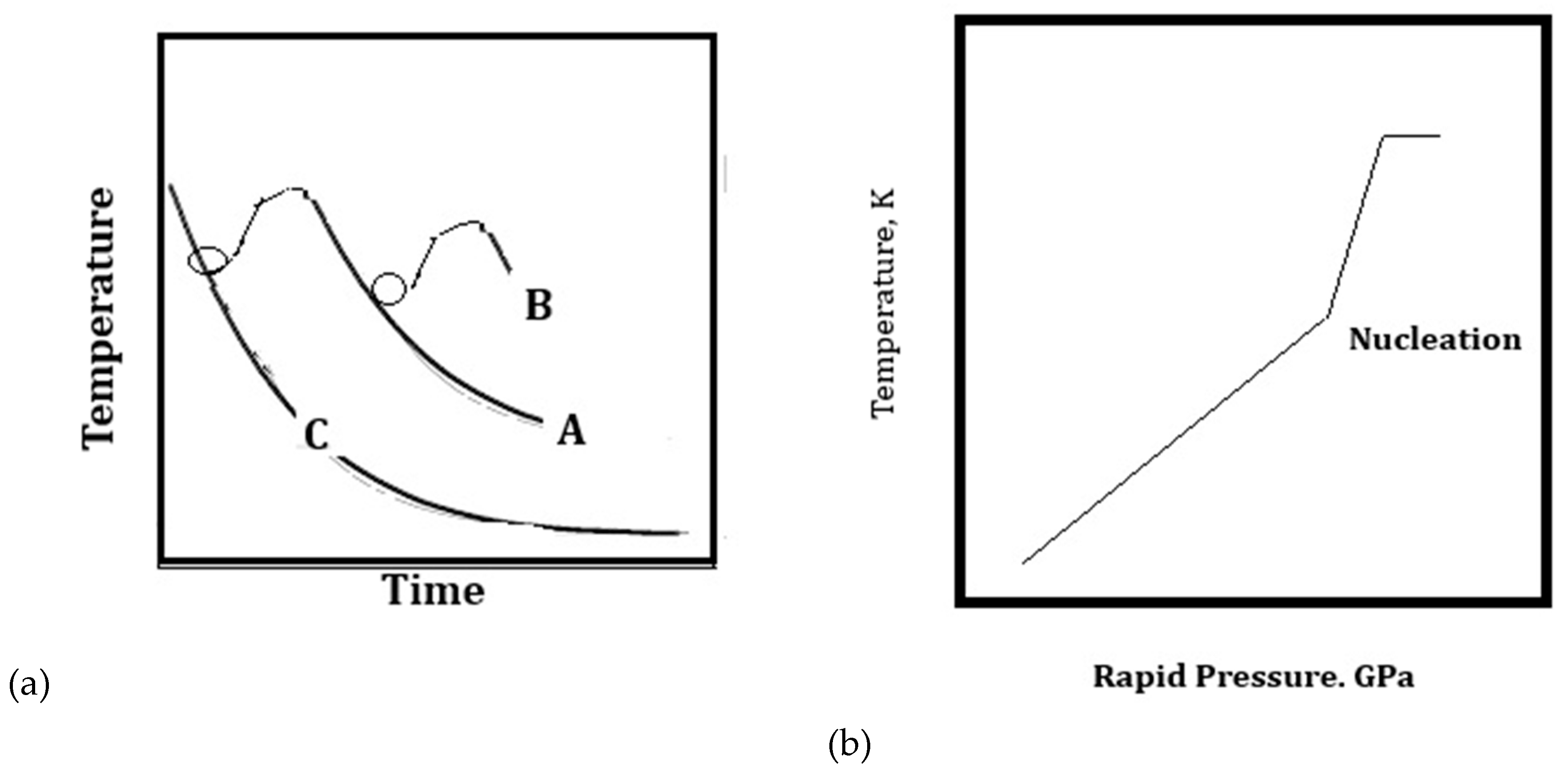

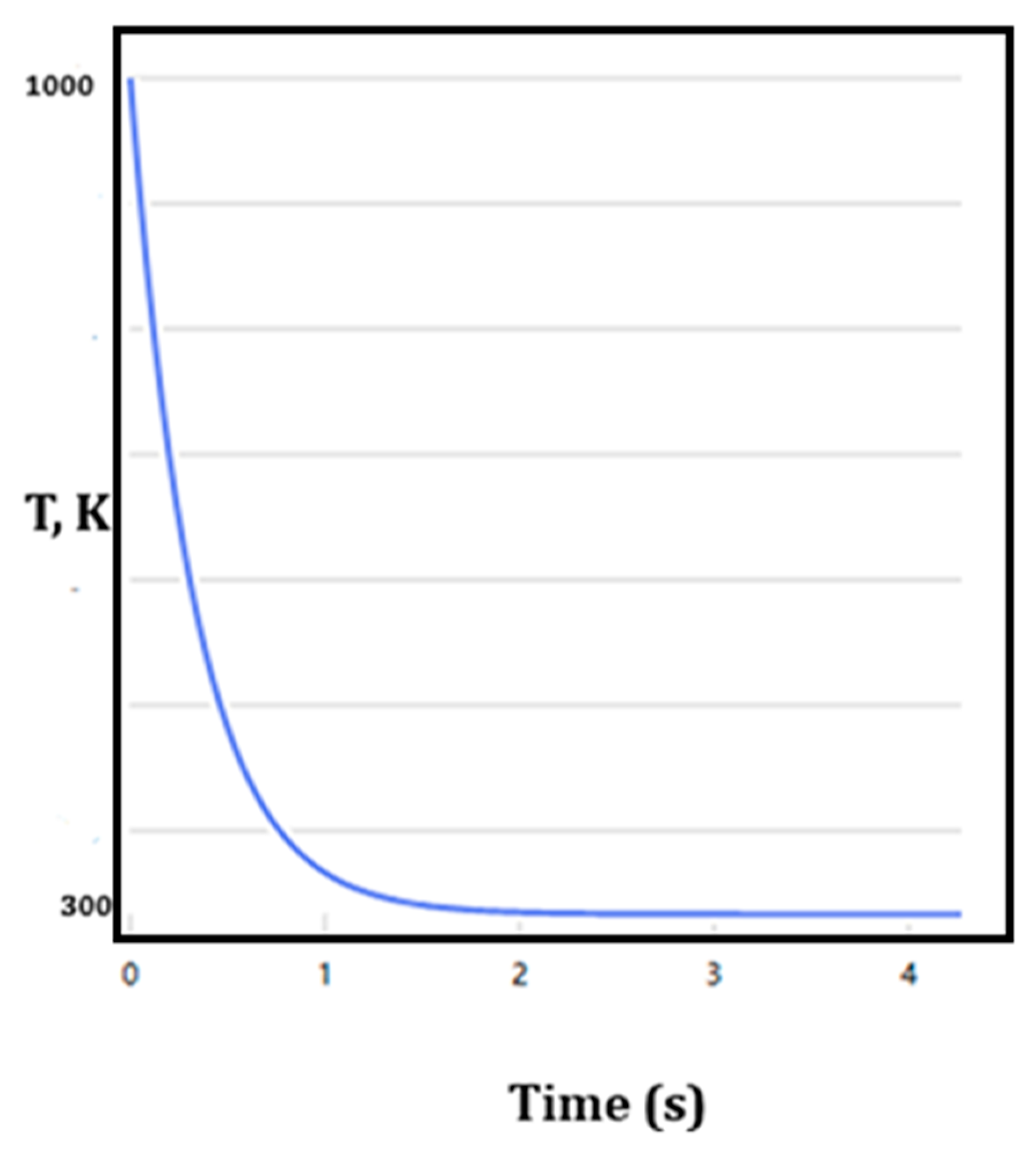

4.2. Non-Steady-State Solidification

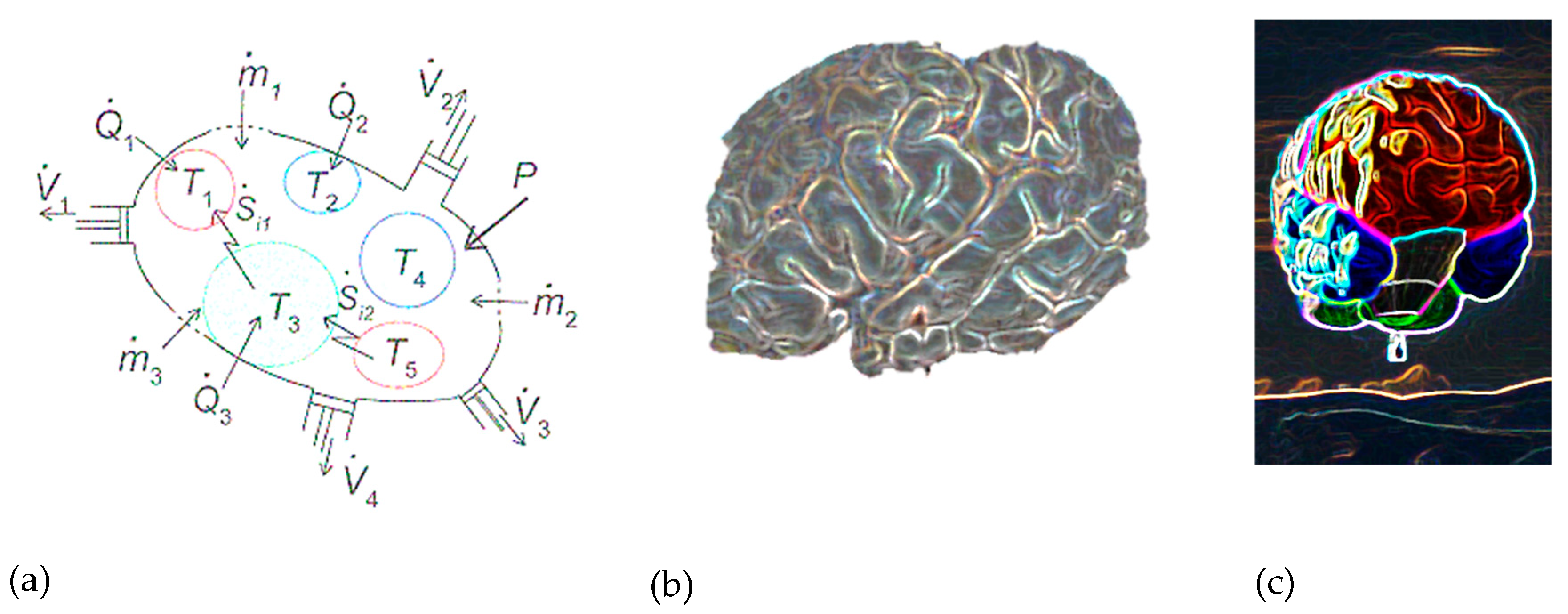

5. Sub-Regions and Sub-Boundary Regions for Energy Storage

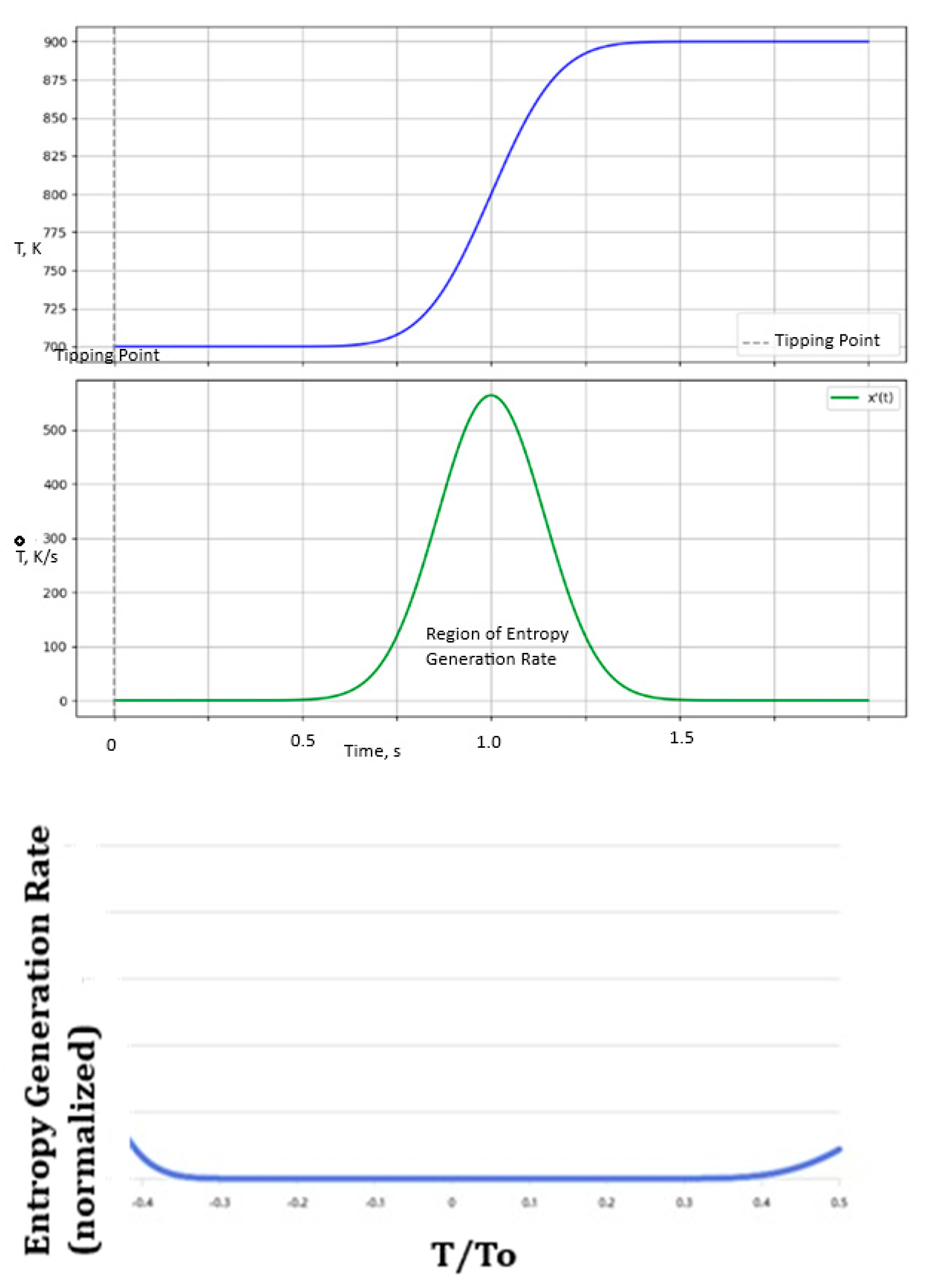

6. The Significance of Sigmoidal-Shaped Curves (S-Curves) for Complex Self-Organization

- (a)

- The PDF/CDF ratio is always positive, as is required for the Sgen and Sgen rate.

- (b)

- An asymptote is noted at infinity (), because the CDF approaches 0, and the PDF also approaches 0, but the ratio approaches a very large, positive value.

- (c)

- The PDF/CDF is related to the entropy generation rate (example Ṫ/T from Figure 8 or after applying the MEPR condition to Equation (3.6)). Typically, after an initial establishment of entropy generation, the rate remains relatively constant during a sigmoidal transformation (self-organization).

- (d)

- At the mean (, The PDF is at its peak (approximately 0.3989), and the CDF is 0.5 for a normal distribution with mean 0 and standard deviation 1. The ratio is ≈ 0.798. There is a relatively stable point of entropy generation across the central part of any such process.

- (e)

- As the PDF/CDF ratio approaches positive infinity (), the CDF approaches 1, while the PDF approaches 0. The ratio, therefore, approaches 0.

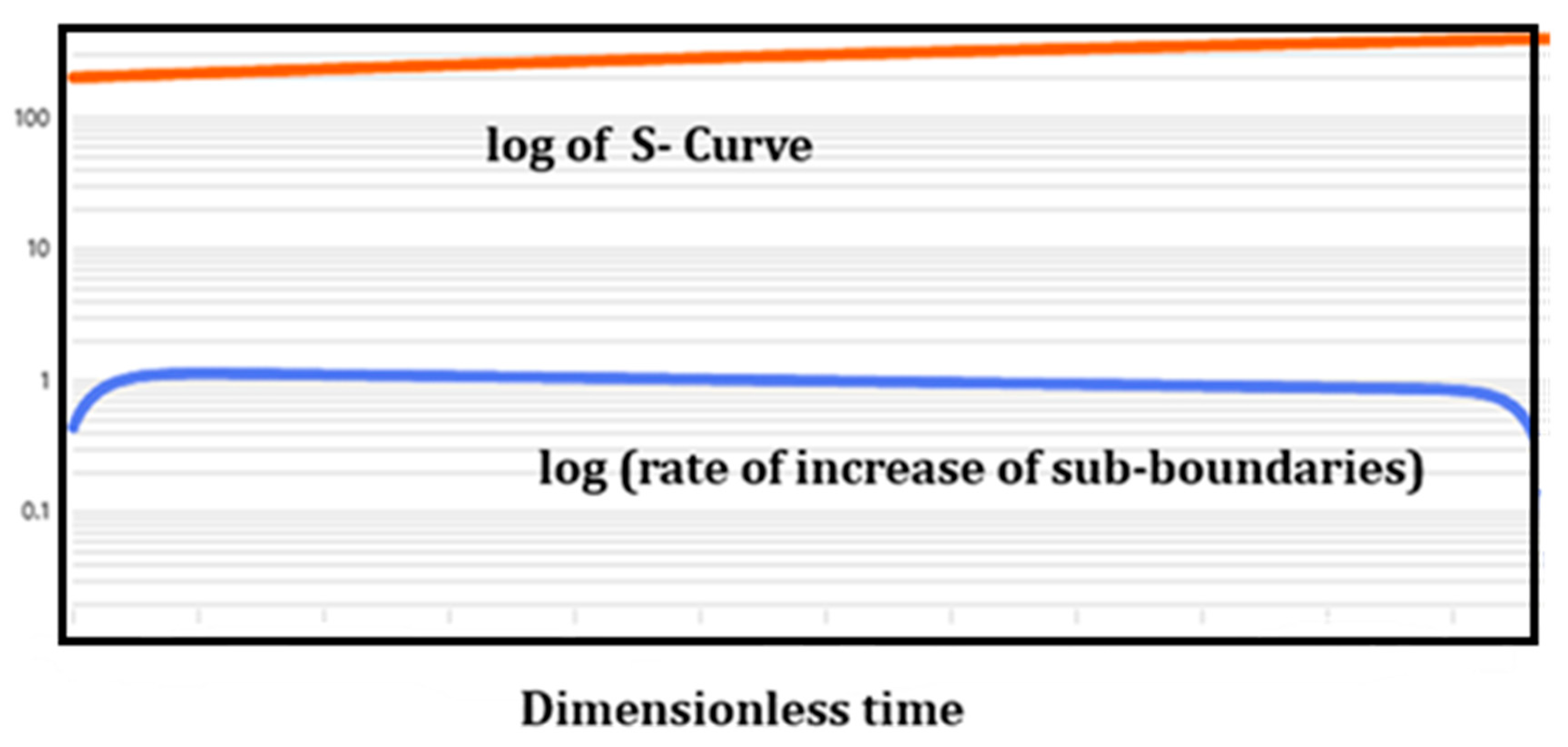

6.1. Groups of Self-Organized sub-Regions Inside a Control Volume

7. Summary and Concluding Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Paltridge, G.W. The steady-state format of global climate. Quart. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 1978, 104, 927–945. [CrossRef]

- Louise K. Comfort, Self-Organization in Complex Systems. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, J-PART, 4(1994):3:393-410.

- Kondepudi, D.; Prigogine, I. Modern Thermodynamics: From Heat Engines to Dissipative Structures; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN-10:0471973947.

- Sekhar, J.A. The description of morphologically stable regimes for steady state solidification based on the maximum entropy production rate postulate. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 6172–6190. [CrossRef]

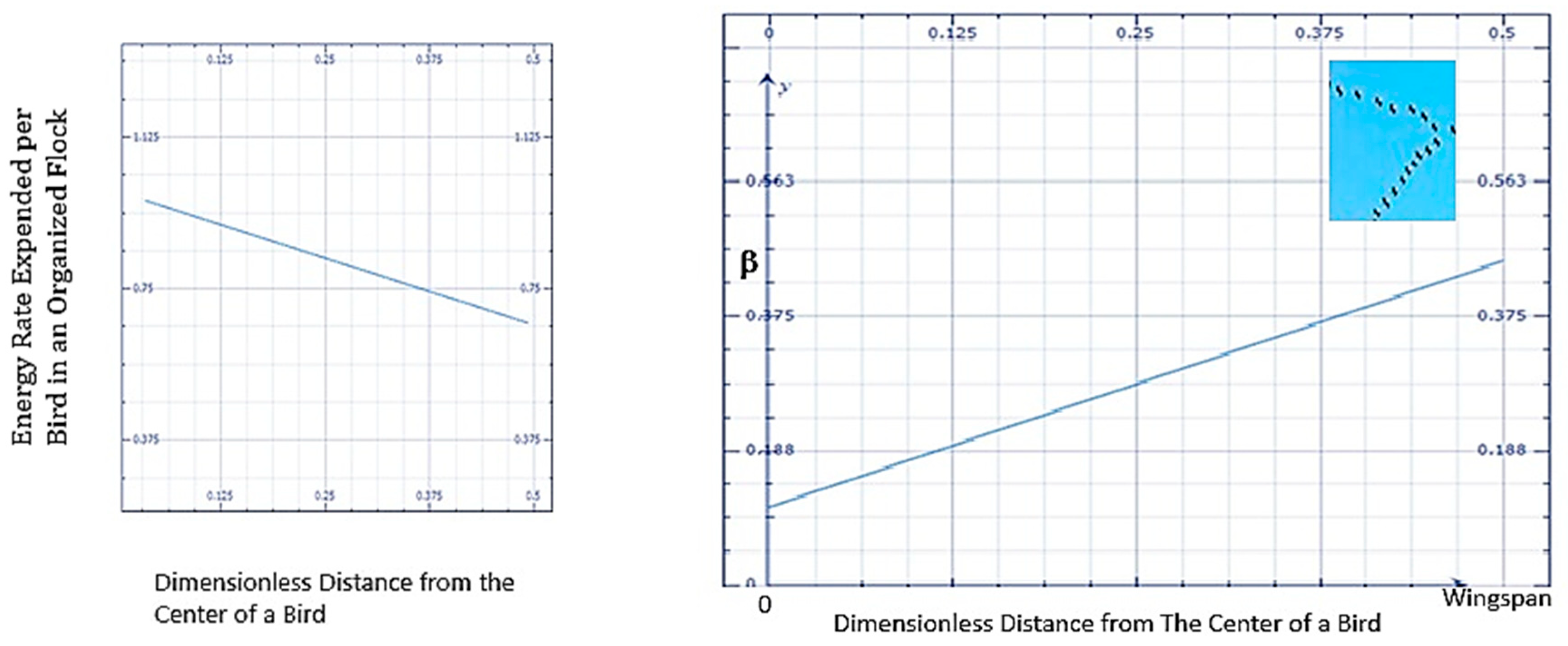

- Sekhar, J.A. An Entropic Model for Assessing Avian Flight Formations. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2204.03102.

- Martyushev, L.M. Maximum entropy production principle: History and current status. Uspekhi Fiz. Nauk 2021, 64, 586–613. [CrossRef]

- Tzafestas, S.G. Energy, Information, Feedback, Adaptation, and Self-Organization, Intelligent Systems, Control and Automation: Science and Engineering 90; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018.

- Pave, A.; Schmidt-Lainé, C. Integrative Biology: Modelling and Simulation of the Complexity of Natural Systems. Biol. Int. 2004, 44, 13–24.

- Fath, B. Encyclopedia of Ecology, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019.

- Niven, RK. Simultaneous Extrema in the Entropy Production for Steady-State Fluid Flow in Parallel Pipes. arXiv 2009, arXiv:0911.5014.

- Endres, R.G. Entropy production selects non-equilibrium states in multistable systems. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14437.

- Wei, Y.; Shen, P.; Wang, Z.; Liang, H.; Qian, Y. Time Evolution Features of Entropy Generation Rate in Turbulent Rayleigh-Bernard Convection with Mixed Insulating and Conducting Boundary Conditions. Entropy 2020, 22, 672. [CrossRef]

- Nicolis G, Prigogine I., Self-organization in non-equilibrium systems. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1977.

- Vita, A. Beyond Linear Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics. In Non-Equilibrium Thermodynamics; Lecture Notes in Physics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1007.

- Dyke, J.; Kleidon, A. The Maximum Entropy Production Principle: Its Theoretical Foundations and Applications to the Earth System. Entropy 2010, 12, 613-630. [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.H. Use and validity of principles of extremum of entropy production in the study of complex systems. Ann. Phys. 2014, 346, 22–27. [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, J. Thermodynamics, Irreversibility and Beauty. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/9548 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Ballufi, R.W.; Allen, M.A.; Carter, W.C. Kinetics of Materials; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005.

- Wikipedia. Differential Entropy. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Differential_entropy (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Martyushev, L.M.; Zubarev, S.N. Entropy production of stars. Entropy 2015, 17, 3645–3655.

- Martyushev, L.M.; Birzina, A. Entropy production and stability during radial displacement of fluid in Hele-Shaw cell. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2008, 20, 465102. [CrossRef]

- Turing, A.M. The molecular basis of morphogenesis. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 1952, 37, 237.

- Bensah, Y.D.; Sekhar, J.A. Solidification Morphology and Bifurcation Predictions with the Maximum Entropy Production Rate Model. Entropy 2020, 22, 40. [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F. The Science of Self-Organization and Adaptivity, Center; Free University of Brussels: Brussels, Belgium, 2001; p. 9.

- H. Reuter, F. Jopp, J. M. Blanco-Moreno, C. Damgaard, Y. Matsinos, and D.L. DeAngelis, Ecological hierarchies and self-organisation - Pattern analysis, modelling and process integration across scales. [CrossRef]

- Lucia, U. Maximum entropy generation and K-exponential model. Phys. A Stat. Mech. Appl. 2010, 389, 4558–4563. [CrossRef]

- Hill, A. Entropy production as the selection rule between different growth morphologies. Nature 1990, 348, 426–428. [CrossRef]

- Ziman, J.M. The general variational principle of transport theory. Can. J. Phys. 1956, 35, 1256. [CrossRef]

- Kirkaldy, J.S. Entropy criteria applied to pattern selection in systems with free boundaries. Metall. Trans. A 1985, 16, 1781–1796. [CrossRef]

- Guggenheim, E.A. (1985). Thermodynamics. An Advanced Treatment for Chemists and Physicists, seventh edition, North Holland, Amsterdam, ISBN 0-444-86951-4.

- Ziegler, H.; Wehrli, C. On a principle of maximal rate of entropy production. J. Non-Equilib. Therm. 1978, 12, 229. [CrossRef]

- Pave, A.; Schmidt-Lainé, C. Integrative Biology: Modelling and Simulation of the Complexity of Natural Systems. Biol. Int. 2004, 44, 13–24.

- Pal, R. (2019). Teaching Fluid Mechanics and Thermodynamics Simultaneously through Pipeline Flow Experiments. Fluids, 4(2), 103. [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. Differential Entropy. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Differential_entropy (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Martyushev, L.M.; Zubarev, S.N. Entropy production of stars. Entropy 2015, 17, 3645–3655. [CrossRef]

- Heylighen, F. The Science of Self-Organization and Adaptivity, Center; Free University of Brussels: Brussels, Belgium, 2001; p. 9.

- Sánchez-Gutiérrez D. Tozluoglu M., Barry J.D., Pascual A.; Mao Y., Escuder L.M., Fundamental physical cellular constraints drive self-organization of tissues. EMBO J. 2016, 35, 77–88.

- Hill, A. Entropy production as the selection rule between different growth morphologies. Nature 1990, 348, 426–428.

- Martyushev, L.M.; Seleznev, V.D.; Kuznetsova, I.E. Application of the Principle of Maximum Entropy production to the analysis of the morphological stability of a growing crystal. Zh. Éksp. Teor. Fiz. 2000, 118, 149.

- Onsager, Lars (1931-02-15). "Reciprocal Relations in Irreversible Processes. I." Physical Review. 37 (4). American Physical Society (APS): 405–426. Bibcode:1931PhRv...37..405O ISSN 0031-899X. [CrossRef]

- Miller, Donald G. (1960). "Thermodynamics of Irreversible Processes. The Experimental Verification of the Onsager Reciprocal Relations". Chemical Reviews. 60 (1). American Chemical Society (ACS): 15–37. ISSN 0009-2665. [CrossRef]

- Crosato, E., Spinney R.E., Nigmatullin, R., Lizier, J.T., Prokopenko M. Thermodynamics and computation during collective motion near criticality. Phys. Rev. E 2018, 97, 012120. [CrossRef]

- Joardar J., Lele S., Rama Roa P. Notes on Thermodynamics of Materials, T.R. Anantharaman Education and Research Foundation (www.tra-erf.org); First Edition (1 January 2016).

- J A. Sekhar An Entropy Generation Rate Model for Tropospheric Behavior That Includes Cloud Evolution, Entropy 2023, 25(12),1625. [CrossRef]

- Gibbins, G.; Haigh, J.D. Entropy Production Rates of the Climate. J. Atmos. Sci. 2022, 77, 3551–3566. [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Liu, Y. Radiation entropy flux and entropy production of the Earth system. Rev. Geophys. 2010, 48, 2008RG000275. [CrossRef]

- Kurz W, Fisher TJ (2003) Solidification. Trans Tech Publications, Switzerland.

- Chalmers B (1964) Principles of solidification. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

- Flemings MC (1974) Solidification processing. McGraw-Hill, New York.

- J.A. Sekhar, H.P. Li, G.K. Dey, Decay-dissipative Belousov–Zhabotinsky nanobands and nanoparticles in NiAl Acta Materialia, Volume 58, Issue 3, February 2010, Pages 1056-1073.

- Kohler JM, Muller SC. J Phys Chem 1995;99:980–3.

- Sekhar, J.A. Self-Organization, Entropy Generation Rate, and Boundary Defects: A Control Volume Approach. Entropy 2021, 23, 1092. [CrossRef]

- Jonathan H. McCoy*, Will Brunner, Werner Pesch, Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 254102. [CrossRef]

- Fabietti, L.M., Sekhar, J.A. Planar to equiaxed transition in the presence of an external wetting surface. Metall Trans A 23, 3361–3368 (1992). [CrossRef]

- Bruce E. Shaw. (accessed on 27 October 2025). [CrossRef]

- P. R. Hiesinger, The Self-Assembling Brain: How Neural Networks Grow Smarter, ISBN 9780691181226, Princeton University Press, 2021.

- I.M. De La Fuente, L. Martínez, A. L. Pérez-Samartín, L. Ormaetxea, C. Amezaga, A. Vera-López, Global Self-Organization of the Cellular Metabolic Structure. PLoS ONE 2008, 3(8): e3100. [CrossRef]

- L. A. Blumenfeld and H. Haken (Eds), Problems of Biological Physics, Springer Berlin Heidelberg, ISBN 9783642678530, 2016.

- 59. K. Somboonsuk, J.T. Mason, and R. Trivedi: Metall. Trans. A, vol. 15A, pp. 967–75, 1984. See also R. Trivedi and K. Somboonsuk, Constrained Dendritic Growth and Spacing, Materials Science and Engineering, 65, pp. 65-74,1984. [CrossRef]

- Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Rapid Solidification Processing, eds R. Mehrabian, B. H. Kear and M. Cohen, Claitor’s Publishing Division, Baton Rouge, LA., Reston, VA, pp. 153–164, 1980.

- R. Nigmatullin and M. Prokopenko, Thermodynamic Efficiency of Interactions in Self-Organizing Systems. Entropy, 23, 757, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bensah, Y.D.; Sekhar, J.A. Interfacial instability of a planar interface and diffuseness at the solid-liquid interface for pure and binary materials. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.05005.

- Bensah, Y.D.; Sekhar, J.A. Morphological assessment with the maximum entropy production rate (MEPR) postulate. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2014, 3, 91–98. [CrossRef]

- Li H.P., Dissipative Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction in unstable micropyretic synthesis, Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering, Volume 3, February 2014, Pages 1-6. [CrossRef]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fractal (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Mandelbrot, Benoît B. (1983). The fractal geometry of nature. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7167-1186-5.

- Gouyet, Jean-François (1996). Physics and fractal structures. Paris/New York: Masson Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-94153-0.

- Chen Y., Equivalent relation between normalized spatial entropy and fractal dimension, Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, Volume 553, 2020, 124627, ISSN 0378-4371. [CrossRef]

- Sekhar J. A. (2018). Tunable Coefficient of Friction with Surface Texturing in Materials Engineering and Biological Systems.Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering, 19,94.

- Sekhar, J.A., Mantri, A.S., Yamjala, S. et al. Ancient Metal Mirror Alloy Revisited: Quasicrystalline Nanoparticles Observed. JOM 67, 2976–2983 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Cengel Y, and Boles, Thermodynamics, McGraw-Hill Seventh Edition, ISBN 9780073529325, 2011.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patterns_in_nature (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minimal_surface (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- J. A. Sekhar A. S. Mantri, Sabyasachi Saha, R. Balamuralikrishnan, P. Rama Rao, Trans Indian Inst Met. [CrossRef]

- Sekhar, J.A.; Mohan, M.; Divakar, C.; Singh, A.K., Rapid solidification by high-pressure application. Scr. Metall. 1984, 18, 1327–1330.

- Levi, C.G.; Mehrabian, R. Heat flow during rapid solidification of undercooled metal droplets. Metall. Trans. A 1982, 13A, 221–234. [CrossRef]

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=axEExcI5k4E (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Garfinkel A, Tintut Y, Petrasek D, Boström K, Demer LL. Pattern formation by vascular mesenchymal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004 Jun 22;101(25):9247-50. Epub 2004 Jun 14. PMID: 15197273; PMCID: PMC438961. [CrossRef]

- Sekhar J. A., and Sivakumar R., 1985, On the improvement of fatigue resistance of Ti-4A-6V castings, Journal of Materials Research, volume 4, 1985, pp. 144- 146.

- Bhaduri, S., Sekhar, J. Mechanical properties of large quasicrystals in the Al–Cu–Li system. Nature 327, 609–610 (1987). [CrossRef]

- Bejan A. Advanced engineering thermodynamics. John Wiley & Sons; 2016 Sep 19.

- Carteret, H.; Rose, K.; Kauffman, S. Maximum Power Efficiency and Criticality in Random Boolean Networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 218702.

- Barato, A.; Hartich, D.; Seifert, U. Efficiency of cellular information processing. New J. Phys. 2014, 16, 103024.

- Kempes, C.; Wolpert, D.; Cohen, Z.; Pérez-Mercader, J. The thermodynamic efficiency of computations made in cells across the range of life. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2017, 375. [CrossRef]

- M. Luebbe et al., Microstructural Evolution in a Precipitate-Hardened (Fe0.3Ni0.3Mn0.3Cr0.1)94Ti2Al4 Multi-Principal Element Alloy during High-Pressure Torsion, Journal of Materials Science, vol. 59, no. 28, pp. 13200 - 13217, Springer, Jul 2024.

- Dey GK, Sekhar JA (1997), Micropyretic synthesis of tough NiAl alloys. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 28(5):905–918.

- Begehr, H., & Wang, D. (2025). Beauty in/of mathematics: tessellations and their formulas. Applicable Analysis, 104(14), 2826–2872. [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.T., Cheng, C.J. & Sekhar, I.A. Solidification microporosity in directionally solidified multicomponent nickel aluminide. Metall Trans A 22, 225–234 (1991). [CrossRef]

- Trivedi R., Directional solidification of alloys. Principles of Solidification and Materials Processing. New Delhi: Oxford and IBH Publishers; 1988. p. 3–65.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kolmogorov_microscales.

- Roberto Benzi, Federico Toschi, 2023, Lectures on Turbulence, Physics Reports, 1021, P1-106. [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.B.; Stewart, W.E.; Lightfoot, E.N. Transport Phenomena, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2007.

- Sekhar JA, Journal of Crystal Growth, Volume 109, Issues 1–4, 2 February 1991, Pages 113-119.

- Trivedi RK., Sekhar JA., Seetharaman V. Metallurgical Transactions A, Volume 20A, April 1989, page 769.

- Douglas Gouvêa, 2024, Thermodynamics of solid-state sintering: Contributions of grain boundary energy, Journal of the European Ceramic Society, Volume 44, Issue 14.

- Hoge Ce, Pask JA, 1977, Ceramurgia International, Volume 3, Issue 3, July–September 1977, Pages 95-99.

- Pozzoli VA, Ruiz MS, Kingston D.,Razzitte AC., Procedia Materials Science 8 (2015), 1073 – 1078.

- Non-negligible entropy effect on sintering of supported nanoparticles, https://arxiv.org/pdf/2204.00812 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Vissa, A. A., & Sekhar, J. A. (2025). Technical Trends, Radical Innovation, and the Economics of Sustainable, Industrial-Scale Electric Heating for Energy Efficiency and Water Savings. Sustainability, 17(13), 5916. [CrossRef]

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entropy_production(accessed on 17 November 2025).

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_brain (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- https://montanaballoon.com/fun-and-colorful-shaped-hot-air-balloons.php (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Schobeiri, M.T. (2022). Turbulent Flow, Modeling. In: Advanced Fluid Mechanics and Heat Transfer for Engineers and Scientists. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Sekhar JA., 2020 Rapid solidification and surface topography for additive manufacturing with beam surface heating, Current Opinion in Chemical Engineering, Volume 28, June 2020, Pages 10-20.

- T. C. Wiiliams, T. J. Klonowski and P. Berkely, The Auk 93, pg. 554-559, 1976.

- https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Canada_Goose/id last accessed December 28, 2022.

- P. B. Lissaman and C. A. Shollenberger, Formation Flight of Birds, Science vol. 168, 1970 pg. 1003-1005.

- Noether, E. Invariante Variations probleme. Nachr. d. König. Gesellsch. d. Wiss. zu Göttingen, Math.-Phys. Klasse 235 (1918). English translation by Tavel, M. A. Invariant variation problems. Transp. Theo. Stat. Phys. 1, 186 (1971).

- Hermann, S., Schmidt, M. Noether’s theorem in statistical mechanics. Commun Phys 4, 176 (2021). [CrossRef]

- L. Luke et. Al., Architectural immunity: Ants alter their nest networks to prevent epidemics, Science, 390,266-271(2025). [CrossRef]

- Brandon Shuck, Brian Boston, Suzanne M. Carbotte, Shuoshuo Han, Anne Bécel, Nathaniel C. Miller, J. Pablo Canales, Jesse Hutchinson, Reid Merrill, Jeffrey Beeson, Pinar Gurun, Geena Littel, Mladen R. Nedimović, Genevieve Savard, Harold Tobin. Slab tearing and segmented subduction termination driven by transform tectonics. Science Advances, 2025; 11 (39). [CrossRef]

- ScienceDaily, 25 October 2025. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/10/251025084616.htm. Last accessed October 24, 2025.

- V. K. Vasudevan and J. A. Sekhar, "Transformation Behavior in Nanoscale Binary Aluminum Alloys," in: Advances in the Metallurgy of Aluminum Alloys, TMS, Warrendale, PA, pp. 398- 405 (2001). Reproduced at the repostiary https://mhi-inc.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Nano-aluminum-alloys-sponsored-by-MHI.pdf.

- N. Dey, J.A. Sekhar Interface configurations during the directional growth of Salol—I. Morphology, Acta Metallurgica et Materialia, Volume 41, Issue 2,1993, Pages 409-424. [CrossRef]

- R. Cheese and B. Cantor, Mater. Sci. Eng, 45, 83 (1980).

- Ye, P.; Yang, C.; Li, Z.; Bao, S.; Sun, Y.; Ding, W.; Chen, Y. Texture and High Yield Strength of Rapidly Solidified AZ31 Magnesium Alloy Extruded at 250 °C. Materials 2023, 16, 2946. [CrossRef]

- Bejan, A., Lorente, S., Yilbas, B. et al. Why solidification has an S-shaped history. Sci Rep 3, 1711 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Szyszka, T.N., Wijaya, D.S., Siddiquee, R. et al. Reprogramming encapsulins into modular carbon-fixing nanocompartments. Nat Commun 16, 9493 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H., Tian, F., Zhang, C. et al. A universal entropic pulling force caused by binding. Nat Commun 16, 9604 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Romanenko, A.; Vanchurin, V. Quasi-Equilibrium States and Phase Transitions in Biological Evolution. Entropy 2024, 26, 201. [CrossRef]

- Connelly, Michael C. & Sekhar, J.A., 2012. "U. S. energy production activity and innovation," Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Elsevier, vol. 79(1), pages 30-46.

- Joseph Swift, Leonie H. Luginbuehl, Lei Hua, Tina B. Schreier, Ruth M. Donald, Susan Stanley, Na Wang, Travis A. Lee, Joseph R. Nery, Joseph R. Ecker, Julian M. Hibberd. Exaptation of ancestral cell-identity networks enables C4 photosynthesis. Nature, 2024. [CrossRef]

- www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/11/251109032410.htm (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Bhaduri, S., Sekhar, J. Mechanical properties of large quasicrystals in the Al–Cu–Li system. Nature 327, 609–610 (1987). [CrossRef]

- https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Birgitte-Andersen-2/publication/24058325_The_hunt_for_S-shaped_growth_paths_in_technological_innovation_A_patent_study/links/00b49526a2fddc408c000000/The-hunt-for-S-shaped-growth-paths-in-technological-innovation-A-patent-study.pdf (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Vellei, M., Pigliautile, I. & Pisello, A.L. Effect of time-of-day on human dynamic thermal perception. Sci Rep 13, 2367 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Huus, L. M., & Ley, R. E. (2021). Blowing Hot and Cold: Body Temperature and the Microbiome. mSystems, 6(5), e00707-21.

- Ali Asgary. https://medium.com/@ali.asgary/can-we-sharpen-the-recovery-curve-48e45111922a.

- https://neurosciencenews.com/brain-termperature-20816.

- Gales, J., Bisby, L.A., and Strafford, T (2012) New Parameters to Describe High Temperature Deformation of Prestressing Steel determined using Digital Image Correlation. StructuralEngineering International. 22 (4). 476-486. [CrossRef]

- Reed-Hill RE, Abbaschian R (1994) Physical metallurgy principles, 3rd edn. PWS Publishing Company, Boston.

- Jones, David R. H., and Michael F. Ashby. 2019. Engineering Materials 1: An Introduction to Properties, Applications and Design. 5th ed. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann/Elsevier.

- Bialystok, Ellen et al., 2012, Trends in Cognitive Sciences, Volume 16, Issue 4, 240 - 250.

- Silva, A.B., Liu, J.R., Metzger, S.L. et al. A bilingual speech neuroprosthesis driven by cortical articulatory representations shared between languages. Nat. Biomed. Eng 8, 977–991 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Dierk Raabe, 2014 Chapter 23 - Recovery and Recrystallization: Phenomena, Physics, Models, Simulation, Eds., David E. Laughlin, Kazuhiro Hono, Physical Metallurgy (Fifth Edition), Elsevier, Pages 2291-2397.

- Rest, J, 2012, Comprehensive Nuclear Materials Volume 3, Pages 579-627.

- Kumar A, Muthuramalingam P, Kumar R, Tiwari S, Verma L, Park S, Shin H. Adapting Crops to Rising Temperatures: Understanding Heat Stress and Plant Resilience Mechanisms. Int J Mol Sci. 2025 Oct 27;26(21):10426. PMID: 41226465; PMCID: PMC12608908. [CrossRef]

- Rao, PV, and Sekhar JA, April 1985, Materials Letters 3(5-6):216-218. [CrossRef]

- P. D. S. de Lima et al, Self-assembled clusters of mutually repelling particles in confinement, Physical Review E (2025). On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2506.19772. [CrossRef]

- Wei Deng, Zihao Wang, Jingmin Wang, Tao Hu, Xiao Wang, Xuemei Li, Jun Yin, Wanlin Guo. Floating droplet electricity generator on water. National Science Review, 2025; 12 (11). [CrossRef]

- Wenchao Hu, Xueliang Zhang, Siyuan Yi, Haijun Wang, Bangchun Wen, Self-synchronization and self-balancing characteristics of a space two rotor system, International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, Volume 303,2025,110673.

- https://youtu.be/_uTPiBlcZpg accessed November 17, 2025.

- Reddy G.S., and Sekhar J. A., Moderate pressure solidification: Undercooling at moderate cooling rates, 1989, Acta Metallurgica 37(5):1509-1519. [CrossRef]

- Allen Institute. "Supercomputer creates the most realistic virtual brain ever." ScienceDaily. www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/11/251118212037.htm (accessed November 18, 2025).

| Characteristics | Relation | Measurement range and MEPR assessment | MEPR validations and assessments. |

| Energy Conservation | Bird Angle for V formation flights of Canadian Geese (5) | The observed V angle is ~ (110-130degrees for a small flock of Canadian geese (05, 06, 107). See Table 2. | The angel for the V formation = 2.tan-1 (Wingspan/Length). The median length/wingspan for Canadian Gesse, based on bird dimensions shown in Table 2 below, with MEPR analysis (5) is: 113-116 degrees. |

| Physical Constants | Diffusion Constants (62) |

Pb-0.01 wt% Sn Experimental: 1.656 x 10-9 m2/s From MEPR: (2.3 – 4.619) x 10-9 m2/s |

Pb-15 wt% % Sn Experimental: 1.656 x 10-9 m2/s From MEPR: (1-67 – 73.54) x 10-9 m2/s (the lower value corresponds to a modified partition coefficient. |

| Bifurcations | Dilute Alloys. Critical tipping point predictions. | Plane Front to Non-faceted Perturbations. The symbols are defined in [47,61,62,476] |

Plane front to Faceted Perturbations ηG is equal to one, and the highest density planes are oriented for growth (4) |

| Climate Sciences | Upward velocity is measured for non-equilibrium thunderclouds that can produce rain (44). | Recorded measurements are to 10 m/s for cumulonimbus clouds (reported in [44]. | MEPR calculated: Depends on For thickness between 1 km and 24 km, the velocity can be 6 m/s to 11 km/s |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).