Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

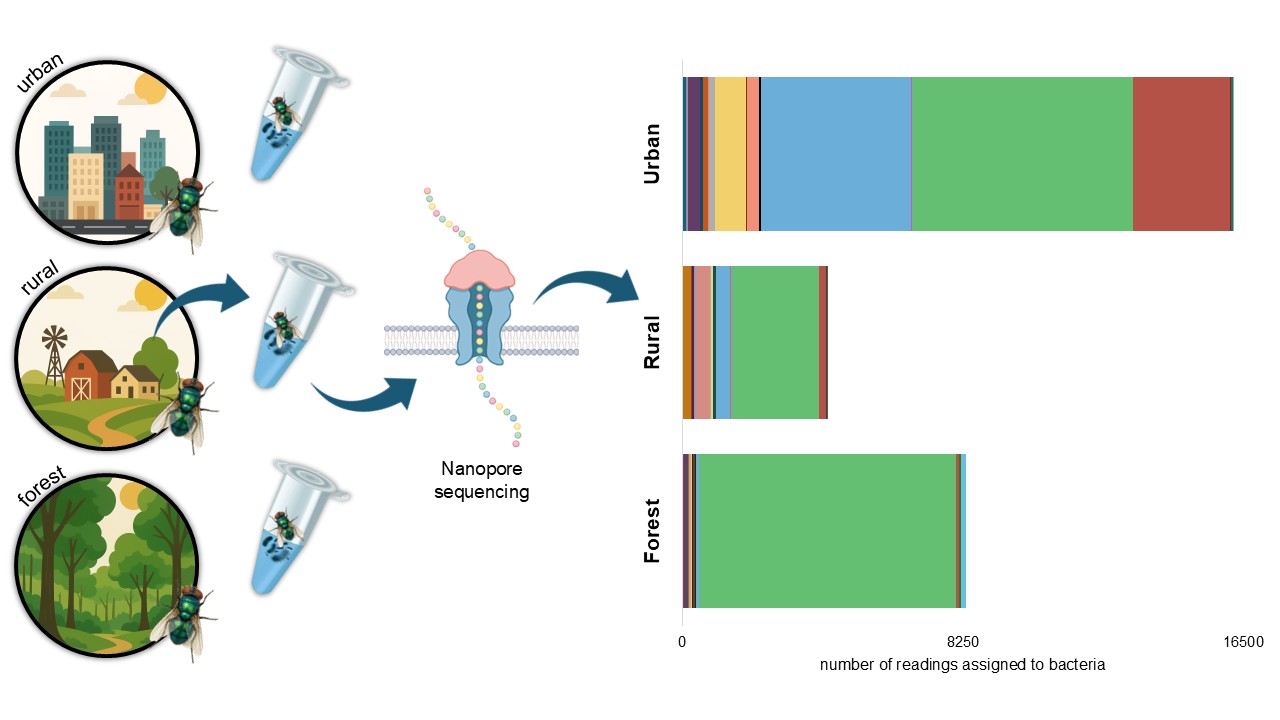

Chrysomya megacephala is a synanthropic fly with a high potential to act as a mechanical vector of pathogenic bacteria, surpassing Musca domestica in both bacterial load and diversity. Native to Asia and Africa, it has become a cosmopolitan species, successfully adapting to a wide range of environments, including natural ecosystems. In Colombia, studies on its role as a vector are limited and have largely relied on traditional culturing methods. This study aimed to characterize the pathogenic bacterial microbiota associated with C. megacephala using 16S rRNA gene sequencing in urban, rural, and forest settings of a coastal tourist city. Flies were collected using Van Someren Rydon traps with attractants and sterile materials. Bacterial identification was performed through Oxford Nanopore MinION sequencing. A total of 49 bacterial species were identified, with urban environments showing the highest richness and abundance. In forest environments, Vagococcus carniphilus was the dominant species. Notably, 20 bacterial species of public health relevance were detected, including Clostridium botulinum, Clostridium perfringens, Ignatzschineria ureiclastica, Escherichia coli, and Streptococcus agalactiae. These findings indicate that bacterial community composition varies by environment and underscore the potential role of C. megacephala as a mechanical vector, highlighting the importance of surveillance for its public health implications.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

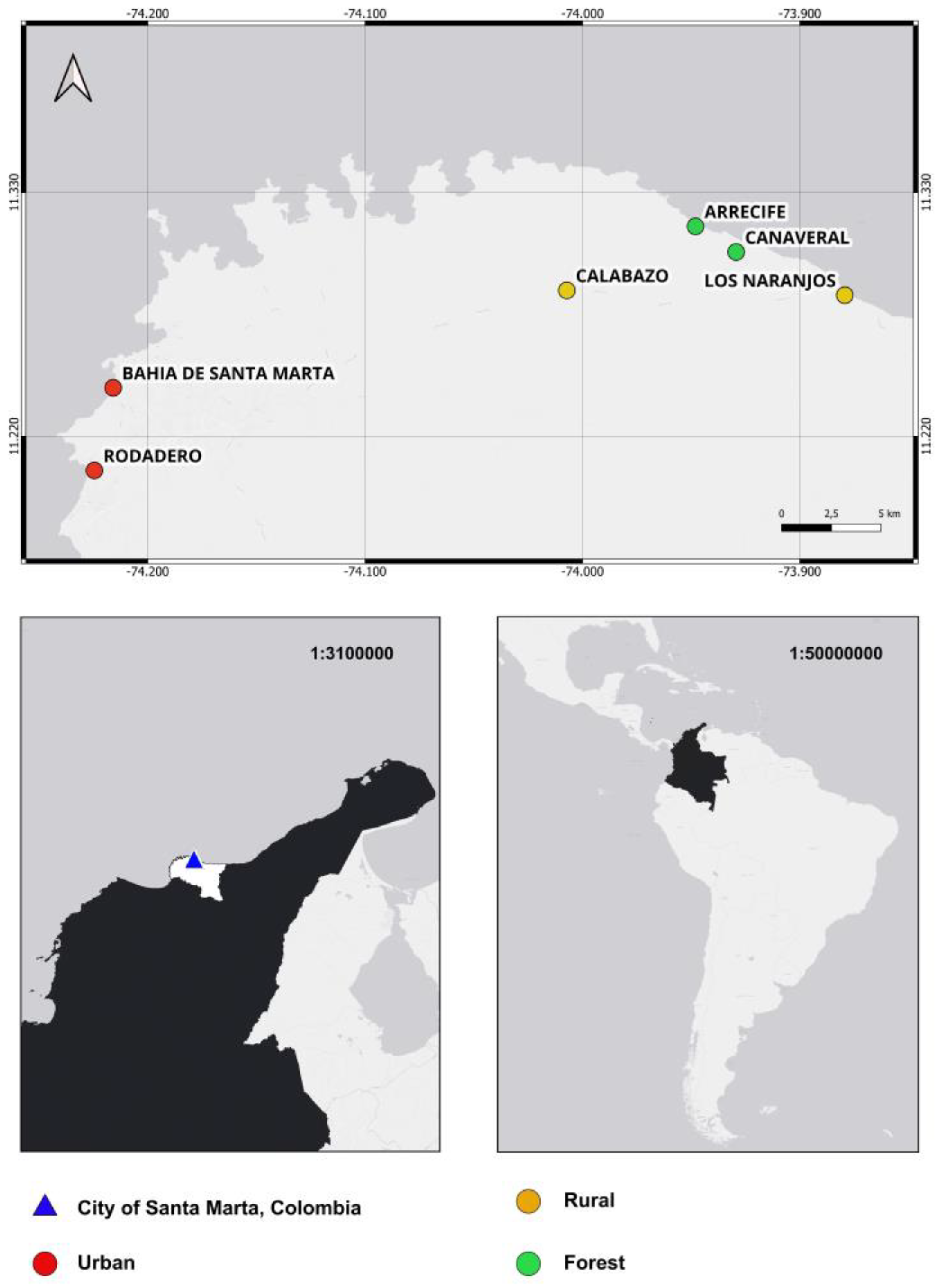

2.1. Study Area and Fly Collection

2.2. Molecular Procedures

2.3. Bioinformatic Analyses

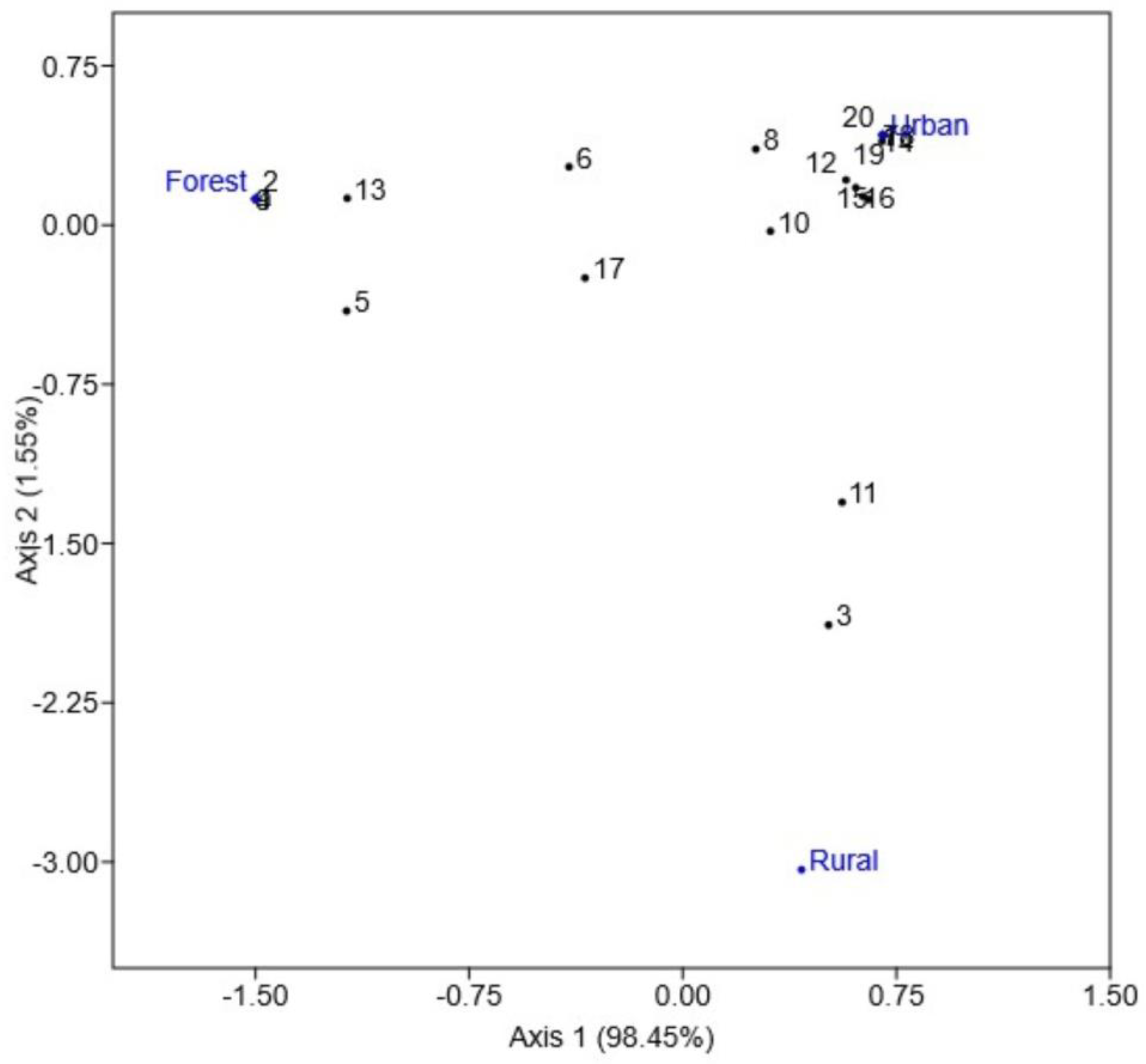

2.4. Bacterial Diversity Analyses

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sukontason, K.L.; Bunchoo, M.; Khantawa, B.; Piangjai, S.; Rongsriyam, Y.; Sukontason, K. Comparison between Musca domestica and Chrysomya megacephala as carriers of bacteria in northern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health 2007, 38(1), 38. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiwong, T.; Srivoramas, T.; Sueabsamran, P.; Sukontason, K.; Sanford, M.R.; Sukontason, K.L. The blow fly, Chrysomya megacephala, and the house fly, Musca domestica, as mechanical vectors of pathogenic bacteria in Northeast Thailand. Trop Biomed. 2014, 31(2), 336–46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Junqueira, A.C.M.; Ratan, A.; Acerbi, E.; Drautz-Moses, D.I.; Premkrishnan, B.N.; Costea, P.I.; et al. The microbiomes of blowflies and houseflies as bacterial transmission reservoirs. Sci Rep. 2017, 7(1), 16324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guimarães, J.H.; Prado, A.P.; Linhares, A.X. Three newly introduced blowfly species in southern Brazil (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Rev Bras Entomol. 1978, 22, 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Vasconcelos, S.D.; Salgado, R.L. First record of six Calliphoridae (Diptera) species in a seasonally dry tropical forest in Brazil: evidence for the establishment of invasive species. Fla Entomol. 2014, 97(2), 814–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, M.; Kosmann, C. Families Calliphoridae and Mesembrinellidae. Zootaxa. 2016, 4122(1), 856–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, J.D. Chrysomya megacephala (Diptera: Calliphoridae) has reached the continental United States: review of its biology, pest status, and spread around the world. J Med Entomol. 1991, 28(3), 471–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiceno, J.; Bastidas, X.; Rojas, D.; Bayona, M. La mosca doméstica como portador de patógenos microbianos en cinco cafeterías del norte de Bogotá. Rev UDCA Actual Divulg Cienc 2010, 13(2), 23–29, Español. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, S.; Ceballos, M.T.; Vanegas, C.; Yepes, S.; Estrada, M.S.; Roncancio, G. Bacterias identificadas en la superficie de Musca domestica y su potencial patogenicidad para el humano. Hechos Microbiol. 2011, 2(2), 55–62, Español. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadavid-Sánchez, I.C.; Amat, E.; Gómez-Piñerez, L.M. Enterobacteria isolated from synanthropic flies (Diptera, Calyptratae) in Medellín, Colombia. Caldasia 2015, 37(2), 319–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, S.; McPherson, J.D.; McCombie, W.R. Coming of age: ten years of next-generation sequencing technologies. Nat Rev Genet. 2016, 17(6), 333–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitworth, T. Keys to the genera and species of blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) of the West Indies and description of a new species of Lucilia Robineau-Desvoidy. Zootaxa 2010, 2663(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khare, P.; Raj, V.; Chandra, S.; Agarwal, S. Quantitative and qualitative assessment of DNA extracted from saliva for its use in forensic identification. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2014, 6(2), 81–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimada, A.; Takeda, O. Site-Directed Mutagenesis with LA-PCR™ Technology. In The Nucleic Acid Protocols Handbook; Rapley, R., Ed.; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2000; p. 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, K.; Connell, J.; Bouras, G.; Smith, E.; Murphy, W.; Hodge, J.C.; et al. A comparison between full-length 16S rRNA Oxford nanopore sequencing and Illumina V3-V4 16S rRNA sequencing in head and neck cancer tissues. Arch Microbiol. 2024, 206(6), 248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Coster, W.; D'Hert, S.; Schultz, D.T.; Cruts, M.; Van Broeckhoven, C. NanoPack: Visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics 2018, 34(15), 2666–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wick, R.R. Porechop [Software]. GitHub. 2017. https://github.com/rrwick/Porechop.

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34(17), i884–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal 2011, 17(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewels, P.; Magnusson, M.; Lundin, S.; Käller, M. MultiQC: Summarize analysis results for multiple tools and samples in a single report. Bioinformatics 2016, 32(19), 3047–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B.; Delitte, M.; Lengrand, S.; Bragard, C.; Legrève, A.; Debode, F. PRONAME: a user-friendly pipeline to process long-read nanopore metabarcoding data by generating high-quality consensus sequences. Front Bioinform. 2024, 4, 1483255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quast, C.; Pruesse, E.; Yilmaz, P.; Gerken, J.; Schweer, T.; Yarza, P.; et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41(D1), D590–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rognes, T.; Flouri, T.; Nichols, B.; Quince, C.; Mahé, F. VSEARCH: A versatile open-source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Oh, H.S.; Park, S.C.; Chun, J. Towards a taxonomic coherence between average nucleotide identity and 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity for species demarcation of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014, 64 Pt 2, 346–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Le, S.; Li, Y.; Hu, F. SeqKit: a cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0163962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; et al. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, Ø.; Harper, D.A.T.; Ryan, P.D. PAST: Paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electron. 2001, 4, 1–9, http://palaeo-electronica.org/2001_1/past/issue1_01.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Heinäsmäki, T.; Kerttula, T. First report of bacteremia by Asaia bogorensis in a patient with a history of intravenous-drug abuse. J Clin Microbiol. 2006, 44(8), 3048–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, A.M.; Dempster, A.W.; Humphreys, C.M.; Minton, N.P. Pathogenicity and virulence of Clostridium botulinum. Virulence 2023, 14(1), 2205251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdizadeh Gohari, I.; Navarro, M.A.; Li, J.; Shrestha, A.; Uzal, F.A.; McClane, B.A. Pathogenicity and virulence of Clostridium perfringens. Virulence 2021, 12(1), 723–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samul, D.; Worsztynowicz, P.; Leja, K.; Grajek, W. Beneficial and harmful roles of bacteria from the Clostridium genus. Acta Biochim Pol. 2013, 60(4), 515–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamian, M.; Rahmati, D.; Akya, A. Clinical manifestations, associated diseases, diagnosis, and treatment of human infections caused by Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae: a systematic review. Germs. 2022, 12(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakbin, B.; Brück, W.M.; Rossen, J.W. Virulence factors of enteric pathogenic Escherichia coli: a review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(18), 9922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mada, P.K.; Khan, M.H. Hathewaya limosa empyema: a case report. Cureus 2024, 16(2), e55156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, K.; Reynolds, S.B.; Smith, C. The first case of Ignatzschineria ureiclastica/larvae in the United States presenting as a myiatic wound infection. Cureus 2021, 13(4), e14518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pot, B.; Felis, G.E.; De Bruyne, K.; Tsakalidou, E.; Papadimitriou, K.; Leisner, J.; et al. The genus Lactobacillus. In Lactic Acid Bacteria; Holzapfel, W.H., Wood, B.J.B., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Chapter 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaaslan, A.; Soysal, A.; Kepenekli Kadayifci, E.; Yakut, N.; Ocal Demir, S.; Akkoc, G.; et al. Lactococcus lactis spp. lactis infection in infants with chronic diarrhea: two case reports and literature review in children. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2016, 10(3), 304–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motta, R.G.; Martinez, A.C.; Junior, O.C.M.P.; Martins, L.D.S.A.; da Paz, J.P.; Bello, T.S.; et al. Atypical mandibular osteomyelitis in an ewe caused by coinfection of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Lactococcus raffinolactis. Acta Sci Vet. 2022, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoiu, M.; Filipescu, M.C.; Omer, M.; Borcan, A.M.; Olariu, M.C. Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides bacteremia in an immunocompromised patient with hematological comorbidities—case report. Microorganisms 2024, 12(11), 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaadi, A.; Alghamdi, A.A.; Akkielah, L.; Alanazi, M.; Alghamdi, S.; Abanamy, H.; et al. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of Morganella morganii infections: a multicenter retrospective study. J Infect Public Health 2024, 17(3), 430–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobadilla, F.J.; Novosak, M.G.; Cortese, I.J.; Delgado, O.D.; Laczeski, M.E. Prevalence, serotypes and virulence genes of Streptococcus agalactiae isolated from pregnant women with 35–37 weeks of gestation. BMC Infect Dis. 2021, 21, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, S.P.; Pighetti, G.M.; Almeida, R.A. Environmental pathogens. In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences, 2nd ed.; Fuquay, J.W., Ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zellner, A.A.; Voss, J.; Franz, A.; Roos, J.; Hischebeth, G.T.R.; Molitor, E.; et al. Musculoskeletal infections caused by Streptococcus infantarius–a case series and review of literature. Int Orthop. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anifowose, O.; Oyebola, O.O.; Ajala, A.C. Haemato-biochemical and histopathological effects of Vagococcus carniphilus infection in Clarias gariepinus (Burchell 1822) juveniles. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobo, F.; Pérez-Carrasco, V.; García-Salcedo, J.A.; Navarro-Marí, J.M. Bacteremia caused by Veillonella dispar in an oncological patient. Anaerobe 2020, 66, 102285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamboj, K.; Vasquez, A.; Balada-Llasat, J.M. Identification and significance of Weissella species infections. Front Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björkroth, J.; Dicks, L.M.T.; Endo, A. The genus Weissella. In Lactic Acid Bacteria: Biodiversity and Taxonomy; Holzapfel, W.H., Wood, B.J.B., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xi, B.D.; Qiu, Z.P.; He, X.S.; Zhang, H.; Dang, Q.L.; et al. Succession and diversity of microbial communities in landfills with depths and ages and its association with dissolved organic matter and heavy metals. Sci Total Environ. 2019, 651, 909–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shewmaker, P.L.; Steigerwalt, A.G.; Morey, R.E.; Carvalho, M.D.G.S.; Elliott, J.A.; Joyce, K.; et al. Vagococcus carniphilus sp. nov., isolated from ground beef. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004, 54 Pt 5, 1505–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngando, F.J.; Tang, H.; Zhang, X.; Yang, F.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, C.; et al. Effects of feeding sources and different temperature changes on the gut microbiome structure of Chrysomya megacephala (Diptera: Calliphoridae). Insects 2025, 16(3), 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Taxa | Urban | Rural | Forest | Total |

| No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | No (%) | |

| Acinetobacter nectaris | 109 (0.67) | 1 (0.02) | 22 (0.26) | 132 (0.46) |

| Asaia bogorensis | 21 (0.13) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 21 (0.07) |

| Bacteroides xylanisolvens | 12 (0.07) | 2 (0.05) | 0 (0) | 14 (0.05) |

| Brochothrix thermosphacta | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.02) | 2 (0.01) |

| Candidatus Kinetoplastibacterium sp. | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 22 (0.26) | 22 (0.08) |

| Catenibacterium mitsuokai | 1 (0.01) | 262 (6.16) | 0 (0) | 263 (80.91) |

| Clostridium botulinum | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.01) | 1 (0) |

| Clostridium perfringens | 2 (0.01) | 4 (0.09) | 0 (0) | 6 (0.02) |

| Clostridium sp. | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.05) | 4 (0.01) |

| Collinsella stercoris | 0 (0) | 4 (0.09) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.01) |

| Dorea formicigenerans | 2 (0.01) | 53 (1.25) | 0 (0) | 55 (0.19) |

| Enterococcus termitis | 1 (0.01) | 6 (0.14) | 18 (0.22) | 25 (0.09) |

| Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae | 0 (0) | 1 (0.02) | 5 (0.06) | 6 (0.02) |

| Escherichia coli | 1 (0.01) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.01) | 2 (0.01) |

| Faecalitalea cylindroides | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.01) | 1 (0) |

| Hathewaya limosa | 1 (0.01) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Ignatzschineria ureiclastica | 362 (2.23) | 1 (0.02) | 92 (1.1) | 455 (1.58) |

| Lactobacillus animalis | 0 (0) | 4 (0.09) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.01) |

| Lactobacillus brevis | 90 (0.56) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 90 (0.31) |

| Lactobacillus floricola | 153 (0.94) | 0 (0) | 20 (0.24) | 173 (0.6) |

| Lactobacillus gasseri | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.02) | 2 (0.01) |

| Lactobacillus helveticus | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.05) | 4 (0.01) |

| Lactobacillus kunkeei | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.05) | 4 (0.01) |

| Lactobacillus pontis | 0 (0) | 5 (0.12) | 1 (0.01) | 6 (0.02) |

| Lactobacillus sakei | 30 (0.19) | 449 (10.56) | 0 (0) | 479 (1.66) |

| Lactococcus lactis | 154 (0.95) | 25 (0.59) | 35 (0.42) | 214 (0.74) |

| Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides | 935 (5.77) | 60 (1.41) | 54 (0.65) | 1049 (3.64) |

| Ligilactobacillus ruminis | 1 (0.01) | 1 (0.02) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.01) |

| Limosilactobacillus reuteri | 4 (0.02) | 32 (0.75) | 6 (0.07) | 42 (0.15) |

| Lonsdalea britannica | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 18 (0.22) | 18 (0.06) |

| Morganella morganii | 11 (0.07) | 1 (0.02) | 69 (0.83) | 81 (0.28) |

| Neokomagataea thailandica | 2 (0.01) | 0 (0) | 9 (0.11) | 11 (0.04) |

| Olsenella sp. | 0 (0) | 37 (0.87) | 0 (0) | 37 (0.13) |

| Parolsenella catena | 0 (0) | 1 (0.02) | 0 | 1 (0) |

| Pseudolactococcus raffinolactis | 1 (0.01) | 1 (0.02) | 0 | 2 (0.01) |

| Ruminococcus sp. | 3 (0.02) | 27 (0.64) | 4 (0.05) | 34 (0.12) |

| Streptococcus agalactiae | 343 (2.12) | 3 (0.07) | 0 (0) | 346 (1.2) |

| Streptococcus equinus | 83 (0.51) | 8 (0.19) | 1 (0.01) | 92 (0.32) |

| Streptococcus infantarius | 4406 (27.19) | 405 (9.53) | 105 (1.26) | 4916 (17.08) |

| Streptococcus parauberis | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.01) | 1 (0) |

| Streptococcus sp. | 37 (0.23) | 44 (1.04) | 0 (0) | 81 (0.28) |

| Turicibacter sp. | 0 (0) | 6 (0.14) | 0 (0) | 6 (0.02) |

| Vagococcus carniphilus | 6479 (39.98) | 2575 (60.59) | 7542 (90.54) | 16596 (57.65) |

| Veillonella dispar | 7 (0.04) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (0.02) |

| Weissella cibaria | 2858 (17.64) | 220 (5.18) | 107 (1.28) | 3185 (11.06) |

| Weissella confusa | 2 (0.01) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.01) |

| Weissella ghanensis | 15 (0.09) | 1 (0.02) | 1 (0.01) | 17 (0.06) |

| Wolbachia endosymbiont sp. | 79 (0.49) | 11 (0.26) | 50 (0.6) | 140 (0.49) |

| Zymobacter palmae | 1 (0.01) | 0 (0) | 129 (1.55) | 130 (0.45) |

| Total | 16206 (100) | 4250 (100) | 8330 (100) | 28786 (100) |

| Code | Taxa | Environment | Association |

| 1 | As. bogorensis | U | Bacteremia in immunocompromised patients (28). |

| 2 | Cl. botulinum | F | It produces botulinum neurotoxin, which causes botulism (29). |

| 3 | Cl. perfringens | U, R | Infections in humans and livestock, such as gas gangrene and enterotoxemia (30). |

| 4 | Clostridium sp. | F | Some species are associated with various human and veterinary diseases (31). |

| 5 | Er. rhusiopathiae | R, F | Skin and systemic diseases in humans (32). |

| 6 | E. coli | U, F | Diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, urinary tract infection; infections in fish (33). |

| 7 | H. limosa | U | Human infections and empiema (34). |

| 8 | I. ureiclastica | U, R, F | Bacteremia associated with myiasis (infested wounds) (35). |

| 9 | Lb. gasseri | F | Infections in immunocompromised patients (36). |

| 10 | Lc. lactis | U, R, F | Infections in immunocompromised patients (37). |

| 11 | Ps. raffinolactis | U, R | Lethal coinfection associated with mandibular pyogranulomatous osteomyelitis in sheep (38). |

| 12 | Le. pseudomesenteroides | U, R, F | Bacteremia in immunocompromised patients (39). |

| 13 | M. morganii | U, R, F | Human infections (40). |

| 14 | S. agalactiae | U, R | Serious infections such as sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis (41). |

| 15 | S. equinus | U, R, F | Bovine mastitis and septicemia (42). |

| 16 | S. infantarius | U, R, F | Bacteremia, endocarditis, and musculoskeletal infections (43). |

| 17 | Va. carniphilus | U, R, F | Skin lesions and hemorrhages in fish (44). |

| 18 | Ve. dispar | U | Severe infections in humans (45). |

| 19 | We. cibaria | U, R, F | Opportunistic pathogen (46). |

| 20 | We. confusa | U | Bacteremia, endocarditis, and abscess cases in humans (47). |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).