1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has evolved from a niche technology to a ubiquitous tool structuring decision-making in various fields. Government agencies, corporations, and public institutions increasingly rely on AI-powered Decision-Support Systems (DSS) to allocate resources, assess risks, and optimize processes [

1,

2,

3]. In Kazakhstan, AI is viewed as a strategic development resource. President K.-Zh. Tokayev's Address emphasized the need to transform AI into a driver of public administration and economic modernization [

4]. In practice, such systems filter resumes, identify suspicious transactions, predict fraud in social benefits, and even support judicial reasoning by providing probabilistic assessments [

1,

5,

6].

The reference to human agency in the title reflects the central emphasis of this study: while AI-based DSSs improve efficiency and predictive accuracy, they should not diminish the autonomy and responsibility of human decision-makers. Emphasizing human agency strikes a balance between technological innovation and maintaining accountability, fairness, and democratic values.

A key debate is whether DSSs enhance human decision-making capacity or undermine autonomy by shifting power toward algorithmic inference [

7,

8,

9]. Research demonstrates that people are prone to automation bias – a psychological tendency to accept algorithmic recommendations without proper verification [

4,

5]. This biased trust, combined with organizational pressure for efficiency, creates conditions in which human agency risks being reduced to formal control rather than meaningful judgment.

At the regulatory level, the European Union adopted the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), the world's first comprehensive regulation in this area [

10,

11,

12]. The act introduces a risk-based approach by prohibiting unacceptable uses, establishing obligations for high-risk systems, and requiring transparency for limited-risk systems [

3,

12,

13]. However, empirical evidence shows that gaps in implementation remain, particularly with regard to public sector accountability and the maintenance of algorithm registries [

14,

15].

Thus, DSSs transform governance not only by increasing efficiency but also by redistributing agency and responsibility between humans and algorithms [

7,

8]. Using an interdisciplinary approach, this article analyzes the impact of DSSs on governance and proposes strategies for ensuring accountability, fairness, and democratic legitimacy.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Human-AI Interaction and Agency

The classical typology of Human-in-the-loop, Human-on-the-loop, and Human-out-of-the-loop has long framed the discussion of human-machine interaction. However, researchers note that this model does not fully capture the persuasive and probabilistic nature of DSS output [

1,

8]. In mass data processing settings such as recruitment or financial services, DSS not only provide neutral information but also guide or constrain choices by ranking candidates, calculating credit scores, or predicting risk [

1,

2,

5].

Experimental studies document the tension between automated trust bias and algorithmic rejection. For example, M. C. Horowitz et al. show that human trust in AI fluctuates depending on the context and visibility of errors: in some cases, users overtrust algorithms, while in others, they reject them after identifying errors [

8]. In the medical field, M. Abdelwanis et al. document that automated trust bias leads to clinical errors, describing the cognitive mechanisms and possible safety measures [

5]. G. Romeo also points out that this problem persists even with additional training for users to interact critically with AI [

6]. A preliminary conclusion is that DSSs restructure human agency. Instead of making meaningful decisions, people become “validators” who formally retain responsibility, but in practice most often agree with algorithmic recommendations [

7,

9].

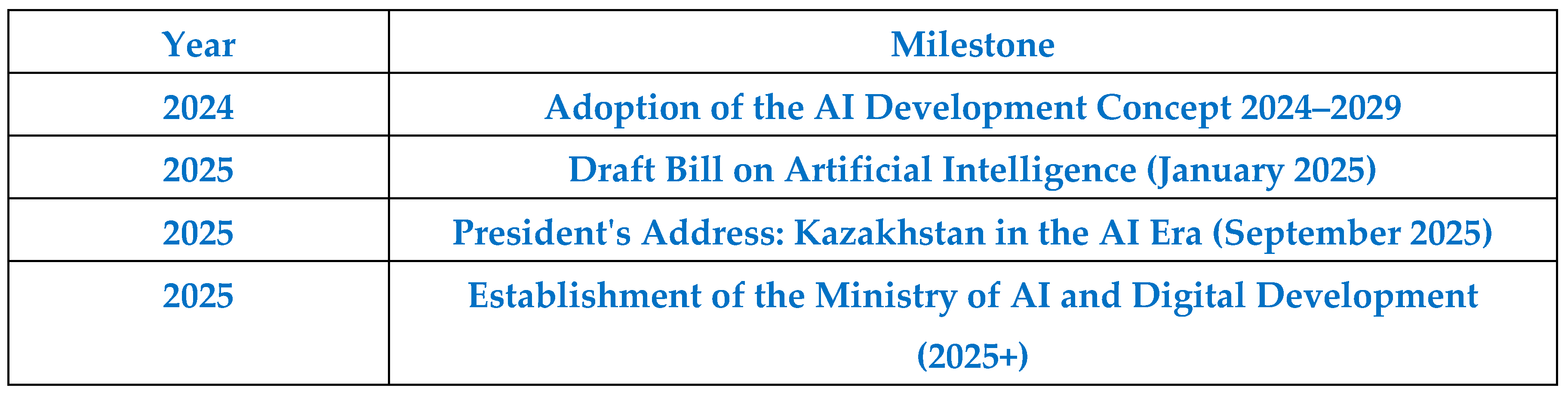

The implications of this transformation are illustrated in

Figure 1, which models the flow of information and responsibility between humans and DSS.

2.2. Accountability and the “Attribution Gap”

J. Zeiser introduces the concept of the “attribution gap” to describe the inability of legal and ethical systems to clearly assign responsibility when outcomes are generated in a hybrid manner – jointly by humans and AI [

7]. Unlike traditional tools, DSSs provide recommendations that are probabilistic, opaque, and often protected by commercial secrecy. As a result, when errors or discriminatory outcomes occur, neither developers nor end users can be easily held accountable [

5,

7].

Public sector research reveals similar problems. The Open Government Partnership (OGP) highlights that algorithmic accountability mechanisms – such as AI system registers, public consultations, and the right to appeal decisions – remain either underdeveloped or poorly implemented [

2]. An analysis by S. M. Parazzoli also demonstrates that public institutions often implement DSS without adequate transparency, undermining citizens' ability to challenge algorithm-based decisions [

14]. Audits in the UK and Australia confirm these concerns: mandatory registers of AI use in the public sector remain incomplete, and oversight mechanisms often fail to identify ethical risks [

15,

16]. At the same time, work [

17] demonstrates that DSS function not only as technical tools but also as "social partners" whose behavior is governed by relational norms. These norms, characteristic of human relationships (mentor-student, partner-advisor, controller), shape user expectations but are limited by AI's inability to empathize and exercise moral judgment. Applying a relational framework allows for a better assessment of the risks of dependency, false expectations, and the distortion of human agency. Collectively, these studies emphasize that accountability in the context of DSS is not only a technical but also an institutional challenge. Contemporary research emphasizes that human-DSS interactions extend beyond issues of accountability and transparency.

2.3. Efficiency Versus Vigilance

Organizations often implement DSS to improve efficiency, but this often comes at the expense of reducing the level of human critical evaluation. N. Spatola et al. describe this phenomenon as the “efficiency-accountability trade-off”: DSS integration allows institutions to process information faster, but simultaneously weakens human control [

9]. G. Romeo confirms that overreliance on DSS is most likely under time pressure, when decision makers lack the opportunity to thoroughly check results [

6]. Thus, a paradox arises: the very conditions that make DSS attractive (speed, scalability, limited resources) simultaneously reinforce the automation bias [

6,

8,

9]. Redistributing the cognitive load – from active analysis to passive oversight – leads to the risk of reducing the human role in decision-making to a formality.

2.4. Regulatory Framework

The EU AI Act is the most ambitious attempt to regulate DSS and AI in general. It introduces a multi-layered system of obligations: a ban on inappropriate applications (e.g., social rating), strict compliance assessment procedures for high-risk areas (e.g., employment, healthcare, law enforcement), and transparency requirements for low-risk applications. General-purpose AI is also included in the scope of regulation, reflecting concerns about model pools and systemic risks [

3,

13,

17]. Unlike the EU with its AI Act, Kazakhstan has approved the Concept for the Development of AI for 2024–2029 [

18], setting out the main regulatory principles and priority application areas. A government press release details plans for the creation of infrastructure, including supercomputers and data centers [

19].

However, critics point out that national administrations are struggling to implement these requirements. For example, The Guardian notes that the UK government has failed to maintain a comprehensive register of AI systems, undermining its transparency commitments [

11]. Similarly, the Queensland Chamber of Auditors has warned of ethical risks in public sector DSS, identifying discrepancies between regulatory principles and practical application [

15].

Researchers also emphasize that DSS influence governance structures beyond legal frameworks. For example, K. Mahroof et al. demonstrate that AI integration alters power dynamics in public administration, redistributing authority between departments and creating new mechanisms for interacting with stakeholders [

20]. Public opinion polls reveal ambivalence: some citizens perceive algorithms as more objective than humans, especially in areas where corruption or favoritism are widespread, while others consider DSS opaque and "depersonalizing" [

21].

2.5. Cognitive and Moral Dimensions

Finally, DSSs influence not only institutional practices but also cognitive and moral processes. A. Salatino et al. demonstrated that AI behavior can directly shape human moral decisions and perceptions of responsibility, raising concerns about hidden "nudges" in ethically relevant contexts [

22]. The study by J. Beck et al., "Bias in the Loop: How Humans Evaluate AI-Generated Suggestions," shows that people evaluate AI-generated suggestions differently depending on their framing, introducing new levels of bias into human-algorithm collaboration [

23]. These findings highlight that preserving human agency is not only a matter of law or governance but also a challenge related to the psychology and sociotechnical design of DSSs.

2.6. AI Policy and Regulation in Kazakhstan

The development of AI governance in Kazakhstan has accelerated significantly since 2024, when the government approved the Concept for the Development of AI for 2024–2029 [

18]. This document defined strategic directions for integrating AI into the economy, public administration, and society. The concept emphasizes the need to create a national AI ecosystem, develop digital infrastructure, and ensure ethical and legal guarantees. Thus, this is the country's first comprehensive policy document in the field of AI, aligning Kazakhstan with global trends in digitalization and AI governance.

An important step was the publication of the draft Bill of the Republic of Kazakhstan "On Artificial Intelligence" [

24] in early 2025. This draft Bill is one of the first legislative initiatives in Central Asia dedicated to AI. It enshrines principles such as the protection of human rights, transparency, accountability, and fairness in the use of AI. The draft Bill also defines the responsibilities of developers, implementers, and users of AI systems, including requirements for documentation, data quality, and risk classification. It draws on international discussions on AI governance, particularly the European AI Act, while taking into account Kazakhstan's institutional and socio-political context. In September 2025, President K.-J. Tokayev, in his Address to the Nation, presented AI as a driver of modernization, emphasizing the country's need to remain competitive in the global digital economy [

4]. He emphasized the importance of a human-centered approach, digital sovereignty, and the creation of a new Ministry of AI and Digital Development, which would coordinate the activities of government agencies. This political positioning reinforces the notion of AI not only as a technological innovation but also as a transformative tool for governance, state legitimacy, and citizen engagement.

Along with legislative initiatives and policy statements, the Kazakh government issued decrees and press releases to ensure the practical implementation of the Concept. For example, Government Resolution No. 592 of July 24, 2024, approved the Concept for the Development of AI for 2024–2029 and obligated ministries to implement its provisions [

18]. A subsequent press release [

19] emphasized practical implementation steps, including pilot projects in healthcare, education, and public administration. Media outlets such as Zakon.kz [

25] and Tribune.kz [

26] also actively engaged in the discussion, presenting AI as both an engine of economic growth and a source of public debate related to data use, privacy, and employment.

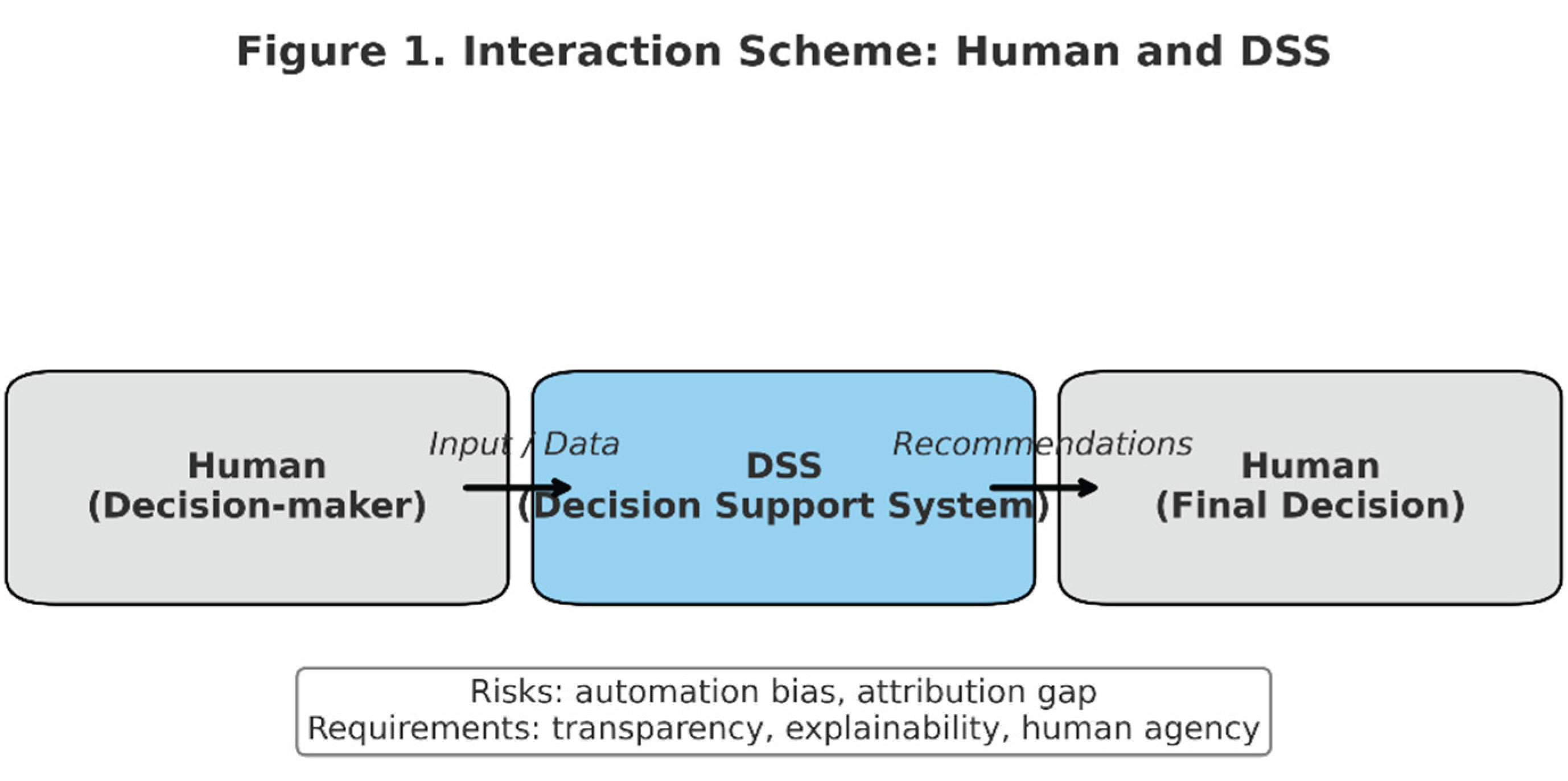

The timeline illustrates the key milestones: adoption of the AI Development Concept (2024–2029), the Draft Bill on AI (2025), and the Presidential Address (2025), highlighting the institutionalization of AI governance at the national level.

Figure 2.

Timeline of AI Policy in Kazakhstan.

Figure 2.

Timeline of AI Policy in Kazakhstan.

All these sources demonstrate Kazakhstan's commitment to building a comprehensive AI regulatory system that integrates legal norms, political will, and strategic planning. At the same time, they also reveal certain tensions: between the pursuit of digital sovereignty and dependence on global AI technologies, between stimulating innovation and protecting human rights, and between efficiency-focused reforms and maintaining accountability. In this sense, Kazakhstan represents a valuable case study of how a middle power integrates global debates on AI regulation with its own governance challenges.

3. Methodology

The study utilizes an interdisciplinary methodology that integrates legal, institutional, and sociotechnical approaches to DSS analysis. The goal is not to test a single hypothesis based on primary data, but to synthesize the latest scientific papers, case studies, and regulations to develop normative and political-legal conclusions [

1,

2,

3,

10,

11,

20].

3.1. Legal and Institutional Analysis

The first part of the methodology includes an examination of legal and regulatory instruments, with a focus on the EU AI Act [

3,

8,

9,

12]. Its multi-level requirements for intolerable, high, and limited risk provide a comparative basis for understanding accountability issues. The analysis also includes debates in the US about algorithmic accountability mechanisms [

8,

9] and governance challenges in developing economies, including issues of digital sovereignty and limited institutional capacity [

12].

3.2. Comparative Case Analysis

The second part draws on empirical examples of DSS applications in the fields of personnel selection, healthcare, financial services, and public administration. The literature on clinical DSS reveals how automated trust bias in medical decisions creates high risks, where errors directly affect human lives [

5,

21]. Personnel selection and credit scoring systems show that DSS simultaneously scale discrimination risks and offer efficiency benefits [

16,

19]. Investigative journalism and government audits reveal the gap between formal accountability frameworks and their practical implementation [

13,

17,

25].

3.3. Sociotechnical and Cognitive Approaches

The third part of the methodology draws on research in human-computer interaction, psychology, and moral philosophy. Research on automation bias and algorithm rejection demonstrates how DSSs affect user trust and vigilance [

11,

20]. Research on moral choice shows that AI can alter people's perceptions of responsibility in ethically relevant situations [

20,

21]. These findings help formulate recommendations for implementing explainability and designing interfaces that support conscious human control.

3.4. Synthesis and Normative Orientation

Bringing together all strands, the study adopts a normative orientation: DSS should be regulated in a way that enhances human agency rather than undermines it. This requires legal frameworks that mandate transparency, organizational practices that encourage critical engagement, and DSS design that minimizes automation biases [

2], [

4,

5,

10,

11,

20,

22]. Thus, the methodology provides a holistic assessment of DSS, linking technical design, institutional structures, and cognitive dynamics into a unified concept of responsible governance.

4. Result & Discussion

4.1. Transformation of Management Decisions

DSS have already transformed decision-making processes in areas such as human resources, healthcare, finance, and public administration. For example, Minister of Digital Development Zh. Madiyev noted that Kazakhstan is placing a premium on AI as a strategic technology [

25]. This reinforces the importance of DSS in public administration, where automated recommendations must be combined with human autonomy and transparency. In recruiting, algorithmic tools filter and rank thousands of resumes in seconds, determining who will even be considered by recruiters [

21,

26]. In finance, DSSs assess creditworthiness using behavioral data, creating risk scores that directly impact access to credit and insurance [

21]. In healthcare, clinical DSSs provide diagnostic recommendations, sometimes outperforming physicians in specific tasks, but creating new risks of automated trust bias when errors go undetected [

5,

23].

As shown in

Table 2, the strategic priorities outlined in Kazakhstan’s AI policy framework are closely linked to the functions of DSS in governance and public administration.

Table 1.

Priority Areas of AI in Kazakhstan and the Role of DSS.

Table 1.

Priority Areas of AI in Kazakhstan and the Role of DSS.

| Priority Area |

AI Applications |

Role of DSS |

| Public Administration |

Smart government services, predictive analytics, digital platforms |

Support decision-making for policy and service delivery |

| Healthcare |

Medical diagnostics, personalized treatment, hospital management systems |

Assist doctors with diagnostics and treatment recommendations |

| Education |

Adaptive learning systems, AI-driven curricula, e-learning platforms |

Help educators personalize learning strategies |

| Agriculture |

Precision farming, monitoring of crops and livestock, forecasting yields |

Guide farmers with data-driven agricultural practices |

| Energy & Environment |

Energy optimization, smart grids, climate monitoring |

Provide recommendations for energy efficiency and sustainability |

| Transport & Logistics |

Traffic management, autonomous transport, supply chain optimization |

Optimize logistics planning and ensure safety in transport systems |

The table illustrates the connection between AI priorities and DSS, setting the stage for a deeper discussion of their role in governance.

The main effect of DSS lies not only in speeding up processes but also in restructuring the procedures themselves. Instead of a comprehensive analysis of evidence, decision makers often receive probabilistic estimates or ranked results. Thus, the human role shifts from active analysis to passive validation, as noted in numerous case studies [

6,

7,

8]. While this increases efficiency, it also reduces the meaningful role of human judgment. From a public administration perspective, DSSs function not as neutral instruments but as sociotechnical actors [

2,

20]. By shaping how information is presented, they shape the framework for acceptable decisions. For example, a DSS in a social security system that labels an applicant as "high-risk" pre-emptively shapes the social worker's perception of the client [

21]. Even if the decision formally remains with the individual, the system's influence on perceptions of the situation is significant [

23,

26]. Thus, DSSs do not simply accelerate processes; they change the architecture of management decisions, which creates a dilemma: increased efficiency is accompanied by a shift in human agency.

4.2. Human Agency and Autonomy

Human agency in DSS-mediated control is undermined by several mechanisms. First, automated trust bias leads people to accept algorithmic recommendations without proper verification [

5,

6,

8]. This tendency is exacerbated by time pressure, cognitive overload, or when users lack sufficient competence to interpret probabilistic inferences [

6]. In practice, the "human in the loop" often becomes a mere rubber-stamp, formally confirming DSS decisions without subjecting them to critical analysis [

7,

17]. Second, DSS results are probabilistic, not deterministic. They are expressed as probabilities or confidence coefficients, requiring statistical literacy for correct interpretation [

6]. Many officials and professionals lack such training, leading to either overreliance on the system or misinterpretation of its findings [

8]. This limits autonomy, as the ability to make independent decisions is reduced. Third, sociotechnical research shows that DSSs affect not only cognitive load but also moral judgment. A. Salatino et al. demonstrate that AI recommendations can bias people's perceptions of responsibility in ethically relevant situations, effectively prompting a change in moral agency. Other experiments show that people evaluate AI proposals differently depending on their framing, increasing the risk of bias [

23]. Thus, autonomy in DSS settings is determined not only by legal or institutional frameworks but also by psychological factors. Unless DSS are specifically designed to support critical reflection, human agency risks becoming a legal fiction that exists only formally [

2,

4,

22].

4.3. Accountability and Legal Risks

Accountability is one of the most pressing challenges associated with the use of DSS. Traditional legal and administrative systems assume a direct line of responsibility between a decision and the person who made it. DSS blur this connection. When an error occurs, it remains unclear who is responsible: the programmer, the implementing organization, or the person who formally approved the result [

7,

17]. This is what J. Zeiser defines as the "attribution gap" [

7]. Accountability is one of the most pressing challenges associated with the use of DSS. An "attribution gap" arises when the distribution of responsibility between developers, organizations, and users becomes blurred [

2,

7].

For a comparison of the challenges of DSS and the solutions proposed in the draft Bill of the Republic of Kazakhstan "On artificial intelligence" (2025), see

Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis: DSS and the Draft Bill the Republic of Kazakhstan on AI (2025).

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis: DSS and the Draft Bill the Republic of Kazakhstan on AI (2025).

| Challenges of DSS (literature) |

Solutions in the Draft Bill on AI (2025) |

|

Attribution gap – it is difficult to determine who bears responsibility for DSS errors: developer, operator, or user [7,17].

|

The Bill establishes distributed responsibility at all stages of the system’s life cycle (development, deployment, operation). Developers, owners, and users bear responsibility within their role. |

|

Automation bias – the risk that humans accept DSS outputs uncritically [5,6,8].

|

Art. 9: priority of human autonomy and free will. Systems must not replace human decision-making, and users have the right to refuse. |

|

Opacity problem (‘black box’) – DSS algorithms are often inexplicable [3,11].

|

Art. 7: users have the right to know the principles of system operation and to receive explanations of decisions. Transparency and explainability are mandatory. |

|

Lack of traceable accountability – impossibility of auditing DSS decisions [9,14].

|

Obligation to maintain documentation depending on the risk level and system impact. This ensures verifiability and auditability of DSS. |

|

Risk of human manipulation – DSS may use behavioral and emotional data [1,22].

|

Ban on the use of subconscious manipulation methods, emotion recognition without consent, and real-time remote biometric identification. |

|

Discrimination and social inequality – DSS may reproduce biases in data [21,25,26].

|

Principle of fairness and equality introduced. Systems that classify people by personal characteristics (e.g., ‘social scoring’) are prohibited. |

|

Dependence of DSS on data quality – errors and bias in input data lead to distorted outcomes [21,23].

|

Creation of a National AI platform and data libraries accessible to DSS. Standards for data quality and control are established. |

|

Lack of user rights – citizens cannot appeal algorithm-based decisions [10,11,12].

|

Users are granted the right to appeal AI-based decisions and to demand explanations. This strengthens procedural safeguards. |

Thus, DSSs can become tools for fairer and more effective governance if their integration is based on principles of fairness, accountability, and respect for human agency.

The situation is exacerbated by the opacity of DSSs. Many systems operate as "black boxes" – either due to the complexity of their machine-learning algorithms or due to commercial secrecy [

10,

11]. This opacity makes it impossible to provide victims with clear reasons for decisions, undermining their right to appeal. Legal frameworks are only beginning to respond to these challenges. The EU AI Act introduces requirements for transparency, documentation, and certification of high-risk systems [

10,

11,

12]. However, as audits and investigative journalism show, gaps remain: government agencies often fail to maintain mandatory registers of AI systems, and oversight bodies lack sufficient resources to ensure compliance. Evidentiary difficulties also arise in court. Unlike a human expert, a DSS cannot be cross-examined. If an algorithm labels a social security applicant as “high-risk” without explanation, the citizen has virtually no recourse to defend their rights [

10]. This undermines procedural fairness and reduces trust in institutions. Accountability under DSS is thus dispersed across multiple actors, with no single actor fully accountable. Without stronger mechanisms for traceable accountability, DSS have the potential to erode the foundations of democratic governance [

9,

14,

20].

4.4. Social and Political Consequences

Integrating DSS into public administration processes has far-reaching social and political implications. On the one hand, they promise efficiency, consistency, and predictive accuracy. On the other, they pose risks of undermining legitimacy and fairness. First, DSS can perpetuate or reinforce existing social biases. Credit scoring, recruitment, and predictive policing systems have already been shown to often disproportionately disadvantage vulnerable groups [

21,

26]. Algorithmic discrimination undermines public trust and exacerbates social inequality [

25]. Second, public perceptions of DSS remain controversial. Some citizens perceive algorithmic decisions as more objective than human ones, especially in contexts where corruption or favoritism are widespread [

26]. However, others view DSS as impersonal, opaque, and unaccountable [

20]. This ambivalence means that DSS can either strengthen or weaken institutional legitimacy, depending on their design, context, and level of transparency. Third, DSS expand the state's ability to monitor and regulate the population. Governments can use AI to track online activity, distribute social benefits, or enforce legislation [

3,

12]. While this enhances administrative capacity, it also raises concerns about surveillance, concentration of power, and potential abuse [

15,

20]. The risk stems not only from technical failures but also from a potential authoritarian bias, where arguments about efficiency serve to justify excessive control.

Finally, DSSs alter power relations within governance structures. K. Mahroof et al. demonstrate that AI integration redistributes authority across departments, sometimes strengthening the influence of technocratic actors at the expense of democratic deliberation [

20]. This can weaken pluralism in the political process and shift decision-making toward less transparent mechanisms. As a result, DSSs act as ambivalent instruments: they provide benefits in the form of efficiency and predictability, but without proper regulation, they can undermine fairness, accountability, and democratic legitimacy [

2], [

9,

10,

14,

20]. At the same time, public perceptions of the technologies remain ambivalent. The media note both high expectations for AI implementation and concerns regarding data protection and trust in algorithms.

5. Conclusions

Thus, DSSs embody the dual nature of artificial intelligence: on the one hand, they can enhance human capabilities by increasing efficiency, forecast accuracy, and decision consistency; on the other, they carry the risk of undermining autonomy, accountability, and democratic legitimacy. Kazakhstan's AI strategy balances ambitious digital transformation goals with the challenges of social trust and the need to ensure human agency.

The analysis revealed that DSSs are transforming governance in four key ways. The restructuring of decision-making processes shifts the human role from active analysis to passive validation of algorithmic results. Challenges to human agency – automated trust bias, the probabilistic nature of conclusions, and the cognitive impact of DSSs – reduce the potential for meaningful autonomy. Accountability issues – an "attribution gap" arises when the distribution of responsibility between developers, organizations, and users becomes blurred. Social and political consequences – DSS can increase discrimination, alter public perceptions of fairness, and expand state control mechanisms, which simultaneously strengthens and weakens institutional legitimacy.

The study's findings confirm that DSS are not neutral tools, but sociotechnical actors that redistribute agency and power within governance systems. To overcome these challenges, three strategies are needed: a) Preserving human agency – humans must remain critical evaluators of decisions, not their formal "validators"; b) Transparency and explainability – algorithmic conclusions must be understandable and contestable for affected individuals; c) Mechanisms for traceable accountability – responsibility must be shared between developers, implementing organizations, and end users.

Thus, DSS can become tools for more just and effective governance if their integration is based on principles of fairness, accountability, and respect for human agency. The challenge for policymakers, technologists, and institutions is not to resist DSS, but to guide their development in ways that strengthen, rather than undermine, democratic governance.

Funding

This research was funded by the Committee of Science of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan, grant number AP19678623.

References

- M. Tretter, “Equipping AI decision-support systems with emotional capabilities? Ethical perspectives,” Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 7, art. 1398395, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3389/frai.2024.1398395.

- Open Government Partnership, Algorithmic Accountability for the Public Sector: Learning from the First Wave of Policy Implementation, Aug. 2021. [Online]. Available: https://www.opengovpartnership.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/algorithmic-accountability-public-sector.pdf.

- Future of Life Institute, High-level Summary of the AI Act, Nov. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Future-of-Life-InstituteAI-Act-overview-30-May-2024.pdf.

- K.-Zh. Tokayev, Address of the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan “Kazakhstan in the Era of Artificial Intelligence: Current Tasks and Their Solutions through Digital Transformation,” Astana, Sep. 8, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=32373963.

- M. Abdelwanis, H. K. Alarafati, M. M. S. Tammam, and M. C. E. Simsekler, “Exploring the risks of automation bias in healthcare artificial intelligence applications: A Bowtie analysis,” Journal of Safety Science and Resilience 5, no. 4, pp. 460–469, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jnlssr.2024.06.001.

- G. Romeo and D. Conti, “Exploring automation bias in human–AI collaboration: a review and implications for explainable AI,” AI & Society, Jul. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-025-02422-7.

- J. Zeiser, “Owning decisions: AI decision-support and the attributability-gap,” Science and Engineering Ethics 30, no. 4, art. 27, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-024-00485-1.

- M. C. Horowitz and L. Kahn, “Bending the automation bias curve: A study of human and AI-based decision making in national security contexts,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.16507, Jun. 2023. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2306.16507.

- N. Spatola, “The efficiency-accountability tradeoff in AI integration: Effects on human performance and over-reliance,” Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans 2, no. 2, art. 100099, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2024.100099.

- “Article 6: Classification Rules for High-Risk AI Systems,” ArtificialIntelligenceAct.eu, 2024/2025. [Online]. Available: https://artificialintelligenceact.eu.

- European Commission, “AI Act | Shaping Europe’s digital future,” 2025. [Online]. Available: https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu.

- European Parliament, “EU AI Act: first regulation on artificial intelligence,” Feb. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.europarl.europa.eu.

- F. Y. Chee, “EU sticks with timeline for AI rules,” Reuters, Jul. 4, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.reuters.com/.

- S. M. Parazzoli, “Towards Algorithmic Accountability in the Public Sector,” presented at Data for Policy 2024, Sep. 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.isi.it/press-coverage/2024-09-simone_parazzoli_research/.

- The Guardian, “UK government failing to list use of AI on mandatory register,” Nov. 28, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.theguardian.com.

- The Australian, “Audit report warns of unethical AI risks in public service,” Sep. 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.theaustralian.com.au.

- B. D. Earp, S. P. Mann, M. Aboy, M. S. Clark, et al., “Relational Norms for Human-AI Cooperation,” ResearchGate, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389089043_Relational_Norms_for_Human-AI_Cooperation.

- Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan, On the Approval of the Concept for the Development of Artificial Intelligence for 2024–2029, Decree No. 592, Jul. 24, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://adilet.zan.kz/rus/docs/P2400000592.

- Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan, Adoption of the AI Development Concept 2024–2029 (Press Release), PrimeMinister.kz, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://primeminister.kz/ru/news/pravitelstvom-prinyata-kontseptsiya-po-razvitiyu-iskusstvennogo-intellekta-na-2024-2029-gody-28786.

- K. Mahroof, V. Weerakkody, Z. Hussain, and U. Sivarajah, “Navigating power dynamics in the public sector through AI-driven algorithmic decision-making,” Government Information Quarterly 42, no. 3, art. 102053, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giq.2025.102053.

- M. Eslami, S. Fox, H. Shen, B. Fan, Y.-R. Lin, R. Farzan, and B. Schwanke, “From margins to the table: Charting the potential for public participatory governance of algorithmic decision making,” in Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’25), pp. 2657–2670, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1145/3715275.3732173.

- A. Salatino, A. Prével, E. Caspar, and S. Lo Bue, “Influence of AI behavior on human moral decisions, agency, and responsibility,” Scientific Reports 15, art. 12329, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-95587-6.

- J. Beck, S. Eckman, C. Kern, and F. Kreuter, “Bias in the loop: How humans evaluate AI-generated suggestions,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.08514, Sep. 2025.

- Dossier on the Draft Bill of the Republic of Kazakhstan “On Artificial Intelligence” (January 2025), Online.zakon.kz, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=34868071.

- “Kazakhstan Bets on AI: Industry Growth and Strategy until 2029,” Zakon.kz, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.zakon.kz/tekhno/6489590-kazakhstan-delaet-stavku-na-ii-rost-otrasli-i-strategiya-do-2029-goda.html.

- “How Kazakhstan Implements Artificial Intelligence and What Society Thinks About It,” Tribune.kz, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://tribune.kz/tsifrovaya-revolyutsiya-kak-kazahstan-vnedryaet-iskusstvennyj-intellekt-i-chto-ob-etom-dumaet-obshhestvo.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).