1. Introduction

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) in critical areas, including finance, healthcare, and public administration, has increased significantly over the last decade. These systems now make decisions that humans previously made. However, as AI becomes more autonomous, determining accountability for harm—such as biased hiring, incorrect medical diagnoses, or market disruptions—becomes complex. Who is responsible: the developer, the organization, the executive, or the AI system itself?

Current accountability frameworks in AI governance are inadequate, posing significant challenges for managing ethical and operational responsibilities. The concept of a "responsibility vacuum" underscores the confusion surrounding decision-making in AI, making it challenging to determine who is accountable for negative outcomes. While discussions about AI ethics stress the importance of transparency, explainability, and reducing bias, they often overlook who is ultimately responsible for decisions influenced by AI (Batool et al., 2024; Cavique, 2024).

According to Batool et al., existing frameworks mainly target specific ethical principles, lacking comprehensive solutions to ensure accountability for AI actions. This narrow focus reveals a significant gap in governance strategies that could hold individuals or organizations responsible for AI-related issues (Batool et al., 2024). Cavique further notes that effective AI governance cannot rely solely on regulations or certifications; it must involve interdisciplinary approaches that foster trust and establish ethical standards for a more robust accountability framework (Cavique, 2024). Weber-Lewerenz emphasizes the need for digital accountability in technology development, advocating for the establishment of ethical guidelines in AI applications. This aligns with the push for governance structures that consider the long-term effects of AI decisions and ensure clear responsibility (Weber-Lewerenz, 2021). As AI is increasingly used in critical sectors like healthcare and finance, establishing accountability frameworks is crucial (Jain, 2024; Agapiou, 2024).

Additionally, the rise of Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) signals an important move toward transparency, which helps rebuild trust in AI systems. Research shows that XAI can address the "black box" issue in many machinelearning models, clarifying decision-making processes (Tiwari, 2023; Linardatos et al., 2020). Improved interpretability reduces ambiguity and supports more transparent accountability (Chaudhry et al., 2022). Chellappan discusses the ethical need for transitioning AI from opaque algorithms to transparent systems, which is crucial for maintaining societal trust and ensuring regulatory compliance (Chellappan, 2024). Furthermore, operationalizing explainability is a key governance area, as highlighted by Nannini et al., who stress the importance of integrating cognitive and social factors to understand AI’s impact on human judgment (Nannini et al., 2024). Balancing transparency with confidentiality and proprietary interests complicates accountability in AI governance. Ultimately, addressing the "responsibility vacuum" requires clear ethical frameworks, enhanced transparency through Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI), and ongoing interdisciplinary discussions.

Current AI accountability frameworks often lack ethical focus and struggle to address the complexities of new technologies. Studies highlight the need for explicit governance models that define accountability in AI decision-making to minimize risks associated with these technologies. This article introduces the concept of the Ultimate AI Accountability Owner (UAAO), the individual or entity responsible for the actions and consequences of an AI system within a specific organizational or regulatory context. The UAAO concept aims to clarify ethical and legal accountability and facilitate practical AI governance through risk assignment, sign-off authority, and policy enforcement. The paper presents a structured approach to identify and institutionalize UAAOs throughout the AI lifecycle, supported by a conceptual framework and case studies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. AI Governance and the Challenge of Responsibility

2.1.1. Regulatory Gaps

Recent governance initiatives, such as the EU AI Act and national AI guidelines, as well as industry-specific frameworks, aim to establish standards for AI systems. However, these regulations often lack clear accountability (Batool et al., 2024; Cavique, 2024). For example, the EU AI Act appoints a “Responsible Person” but leaves critical responsibilities to individual Member States, resulting in inconsistent enforcement (Weber-Lewerenz, 2021). In the U.S., agencies such as the SEC and FDA guide AI in finance and healthcare (Jain, 2024). However, no law identifies who bears ultimate liability when an algorithm harms a consumer (Mittelstadt, 2019). As a result, organizations can comply with procedural requirements without facing accountability since no law explicitly ties a high-level executive to negative outcomes. This fragmentation creates “regulatory gaps,” where compliance may appear satisfactory on paper, but no one is legally obligated to address systemic issues that lead to real-world harm (Rubel et al., 2019).

2.1.2. Ethical and Technical Challenges

Ethical guidelines, such as the OECD AI Principles and IEEE 7000 series, stress transparency, fairness, and human oversight but do not clarify who should enforce these standards (Asan & Choudhury, 2021; Birkstedt et al., 2023). Many AI systems are "black boxes" (Rahwan, 2018), which complicate efforts by any team—whether it be data science, compliance, or leadership—to understand model decisions or identify biases (Binns, 2021; Santoni de Sio & van den Hoven, 2018). Additionally, continuous learning models can evolve, which means that even those who pass initial audits may begin exhibiting harmful behavior without notice (Weber-Lewerenz, 2021). As a result, ethical requirements often turn into mere checklists with no one held accountable for acting on them. This gap between what ethics demand and who is responsible highlights the need for a dedicated UAAO to bridge the divide between "what should be done" and "who does it" (Elish, 2019; Batool et al., 2024).

2.2. Legal and Ethical Responsibility in Autonomous Systems

Accountability for AI-related harms is increasingly addressed through existing legal frameworks, such as tort and data protection laws. However, these frameworks often overlook the complexities of automated decision-making systems, especially when AI outputs are unpredictable or challenging to explain. This issue is echoed by Leenes et al. (2017), who highlight that the intricacies of automated decision-making challenge current liability structures and complicate the application of traditional liability concepts tied to individual human actions (Batool et al., 2024; Cavique, 2024).

Ethical frameworks that promote "human-in-the-loop" or "human-on-the-loop” aim to ensure essential human judgment in critical AI operations (Rahwan, 2018). Human oversight is crucial for mitigating the potential harm of decisions made by automated systems (Weber-Lewerenz, 2021). However, research shows that human involvement in AI decision-making often becomes superficial and reactive due to organizational pressures for efficiency, undermining meaningful oversight (Binns, 2021; Jain, 2024). This raises both legal and ethical concerns about the need for strong human participation in decision-making (Agapiou, 2024).

Recent studies have revealed "deep automation bias," where excessive trust in automated systems leads to complacency in human oversight, thereby exacerbating ethical issues (Tiwari, 2023). Strauß, (2021) points out that ethical considerations in technology design can inadvertently increase risks if not handled carefully. The term "agency-laundering" describes how organizations might evade responsibility for ethical dilemmas by framing them as technical issues (Rubel, 2019; Linardatos et al., 2020). Ng et al. (2023) emphasize the need for clear legal liability and accountability to mitigate risks associated with AI in sectors such as public health and safety (Chaudhry et al., 2022).

Regulatory measures, such as those proposed in the EU’s AI Act, require a critical review of current accountability models. These frameworks must adapt to address the distributed agency of AI systems, where decision-making is spread across multiple stakeholders—developers, infrastructure, algorithms, and organizational leaders—creating further accountability challenges (Chellappan, 2024; Nannini et al., 2024).

Organizations must cultivate a culture of responsible and ethical AI usage. This requires comprehensive training and awareness, as highlighted by Birkstedt et al. (2023), who recommends that ethical considerations be integrated into AI deployment strategies (Li, 2024). Providing ethical training for stakeholders, along with ensuring regulatory compliance, can enhance transparency, accountability, and trust in AI systems (Сулейманoва, 2024).

While current laws address AI-related harms, a gap remains in assigning accountability for these harms. To maximize the benefits of AI and minimize risks, governance frameworks must evolve to clearly define roles and responsibilities in distributed decision-making.

2.3. Organizational Role Ambiguity and Responsibility Dilution

Organizational theory highlights how responsibility can dilute in complex systems, especially in AI governance. In bureaucratic setups, responsibilities are divided among technical teams, compliance units, and executives, resulting in fragmented knowledge and unclear accountability (Mulgan, 2018; Batool et al., 2024). The "many hands" problem (Bovens, 1998) refers to the difficulty in determining accountability due to overlapping responsibilities (Cavique, 2024).

Studies on AI ethics reveal that many organizations lack precise mechanisms for accountability regarding ethical or legal failures associated with the use of AI. Mittelstadt (2019) points out that unclear role definitions create significant oversights and slow responses to AI-related harms (Weber-Lewerenz, 2021). These findings highlight a critical gap in the application of ethical guidelines in organizations using AI, underscoring the need for structured frameworks to clarify accountability (Jain, 2024).

The diffusion of responsibility can hinder deep ethical engagement, particularly in high-stakes situations where human judgment is crucial. As Binns, 2021 points out, organizational pressures for efficiency may lead to superficial compliance rather than genuine oversight (Agapiou, 2024). Organizations need to establish strong ethical frameworks and accountability mechanisms to manage the interaction between human and AI decision-making effectively (Tiwari, 2023).

Asan and Choudhury (2021) argue that organizations should adopt governance strategies that promote accountability and integrate ethical considerations in all stages of AI deployment, from design to implementation (Linardatos et al., 2020). This approach helps mitigate risks of ethical and legal failures while fostering responsible AI use (Chaudhry et al., 2022).

Silbey (2011) emphasizes the importance of fostering an organizational culture that promotes ethical engagement and accountability, which in turn influences how AI systems are managed (Chellappan, 2024). Additionally, training and awareness are crucial for stakeholders to navigate the complexities and ethical implications of AI systems effectively (Nannini et al., 2024).

By defining roles and improving ethical training, organizations can effectively address AI challenges and prioritize responsible decision-making in technology.

2.4. Conclusion of Literature Review

Despite extensive research on fairness, bias, and technical accountability tools such as model audibility and traceability (Raji et al., 2020), a significant gap remains in assigning responsibility within organizational AI ecosystems. This gap is further exacerbated by the lack of integrated leadership frameworks that incorporate both human judgment and AI decision-making (Frimpong, 2025). Currently, no established framework identifies who is ultimately responsible for the outcomes of AI. This article aims to fill that gap by introducing the Ultimate AI Accountability Owner (UAAO) as a concept for enhancing accountability in AI governance. It offers a practical and flexible framework for attributing responsibility across various sectors and regulatory contexts.

3. Theoretical Framework: The Ultimate AI Accountability Owner (UAAO)

3.1. Conceptualizing the UAAO

The Ultimate AI Accountability Owner (UAAO) is defined as the individual or role that bears final accountability for the outcomes of an AI system within a given organizational, legal, or regulatory structure. This concept emerges from the growing recognition that in AI-enabled environments, responsibility tends to be distributed, delayed, or diffused—making it difficult to establish clear lines of liability or ethical ownership when things go wrong. The UAAO is not necessarily the person who develops or deploys the system but instead, the actor who has the formal authority to approve, oversee, and be held accountable for the AI system’s behavior, especially in high-risk or high-impact contexts. This framing builds on and extends prior theoretical work on “meaningful human control” (Santoni de Sio & van den Hoven, 2018) and “moral crumple zones” (Elish, 2019) but focuses explicitly on institutional responsibility rather than distributed or emergent responsibility.

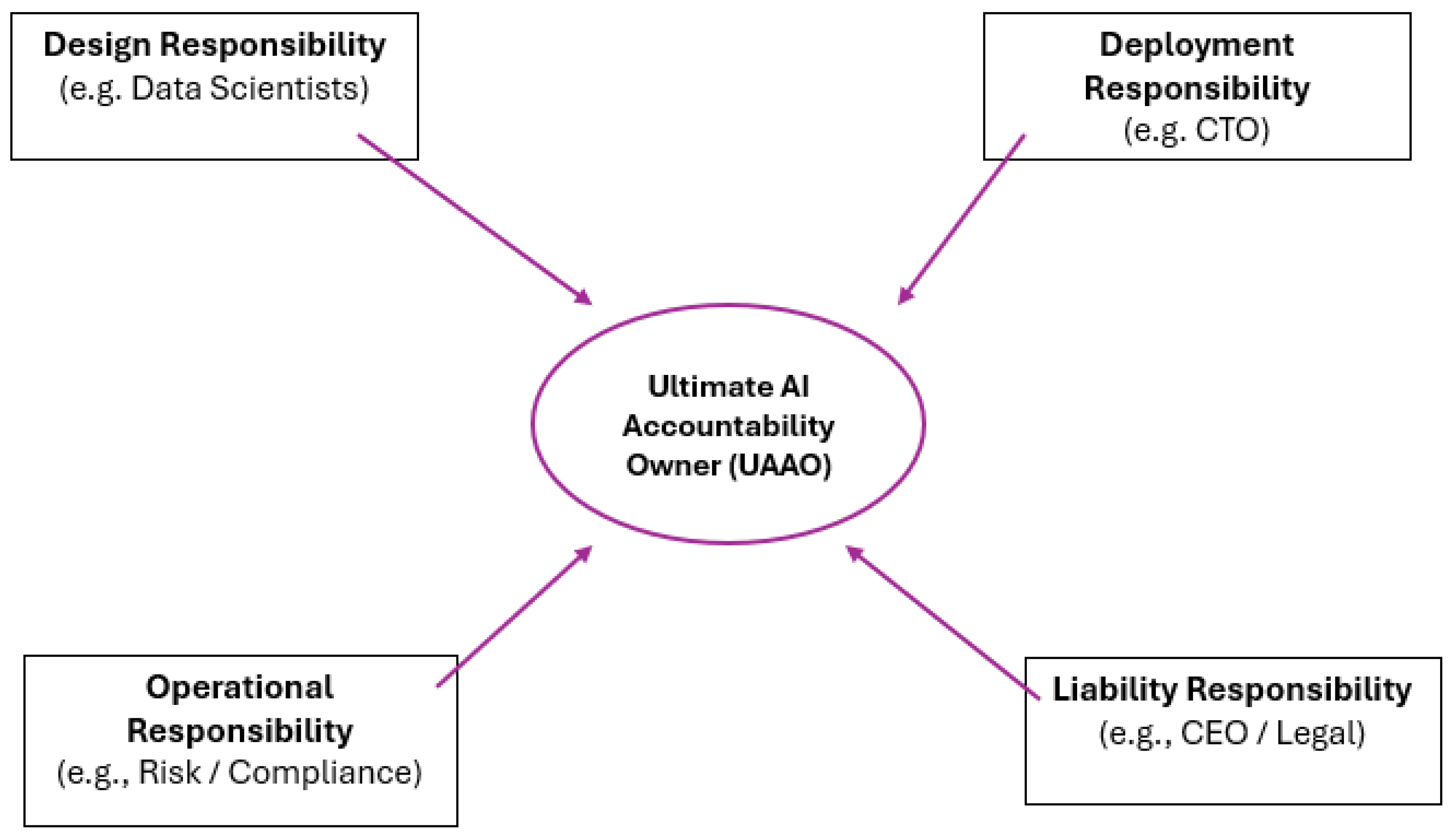

This conceptual architecture is illustrated in

Figure 1, which maps the four core responsibility domains and their convergence on the designated UAAO, thereby clarifying where final accountability resides.

The diagram illustrates the Ultimate AI Accountability Owner (UAAO) as the primary accountability figure across four key areas in AI systems: Design, Deployment, Operation, and Liability. Each area involves specific roles, such as data scientists, CTOs, risk officers, and legal or executive leadership. The arrows represent the flow of responsibility to the UAAO, whose job is to unify authority and ensure ethical and legal accountability throughout the AI lifecycle. For instance, a developer may not have the authority to make deployment decisions, while a compliance officer may not face legal liability.

3.2. UAAO Mapping Across Organizational Structures

The UAAO Mapping Model establishes a framework for governing AI systems by tracing responsibility through the following key elements:

1. Actors: Developers, data scientists, product owners, compliance teams, and executives.

2. Artifacts: Algorithmic models, documentation, audit trails, and risk reports.

3. Decisions: Approvals, overrides, escalation protocols, accountability sign-offs.

This model helps organizations assign ownership at each stage, resulting in a documented UAAO designation. This clarity is crucial in high-stakes fields such as finance, healthcare, and criminal justice, where unclear responsibilities can lead to public harm and legal complications.

3.3. Normative Foundations

Several theoretical foundations also inform the UAAO framework:

Accountability Theory (Bovens, 2007): For accountability to exist, there must be identifiable actors, mechanisms for answerability, and enforceable consequences.

Institutional Responsibility (Thompson, 1967): In complex systems, institutions must establish responsibility structures, not just individuals.

Risk Governance (Castaños & Lomnitz, 2008): Effective governance requires clear assignments of risk ownership and control functions.

Integrating the UAAO into organizational governance makes these principles actionable for AI systems, where traditional ideas of responsibility can be unclear or complicated.

3.4. Analytical Utility of the UAAO Framework

The UAAO concept serves both diagnostic and prescriptive purposes:

- ▪

Diagnostically, it analyzes past AI failures to identify where responsibility was lacking.

- ▪

Prescriptively, it establishes governance structures that require a UAAO designation before deployment.

The UAAO framework is flexible and sector-neutral, applicable to private companies, public agencies, or hybrid partnerships. It provides a consistent way to trace accountability in automated, opaque systems with multiple actors.

4. Methodology

This study uses a conceptual framework and a comparative case study design to demonstrate the Ultimate AI Accountability Owner (UAAO) model in AI governance. Given the evolving and interdisciplinary aspects of AI accountability, this approach is practical for building theory in areas that are still underexplored, where conceptual clarity is essential but empirical generalization is not yet appropriate (Edmondson & McManus, 2007).

The research design includes two complementary components:

Conceptual Framework Development: This component proposes the UAAO as a new accountability structure for AI systems. It is based on organizational theory, legal and ethical scholarship, and risk governance literature, outlining the dimensions, functions, and reasoning behind UAAO designation. The framework incorporates principles for attributing responsibility and enforcing accountability.

-

Comparative Case Study Analysis: The study tests and refines the framework through a comparative case analysis of AI applications in three critical sectors:

- -

Automated hiring systems (human resources)

- -

AI-driven financial services (trading and fraud detection)

- -

-

AI in healthcare diagnostics (clinical decision support)

These cases were selected based on theoretical sampling (Yin, 2018) because they involve AI systems that have a significant impact on real-world outcomes, raising important ethical, legal, and operational issues. Responsibility attributes in these contexts are often unclear.

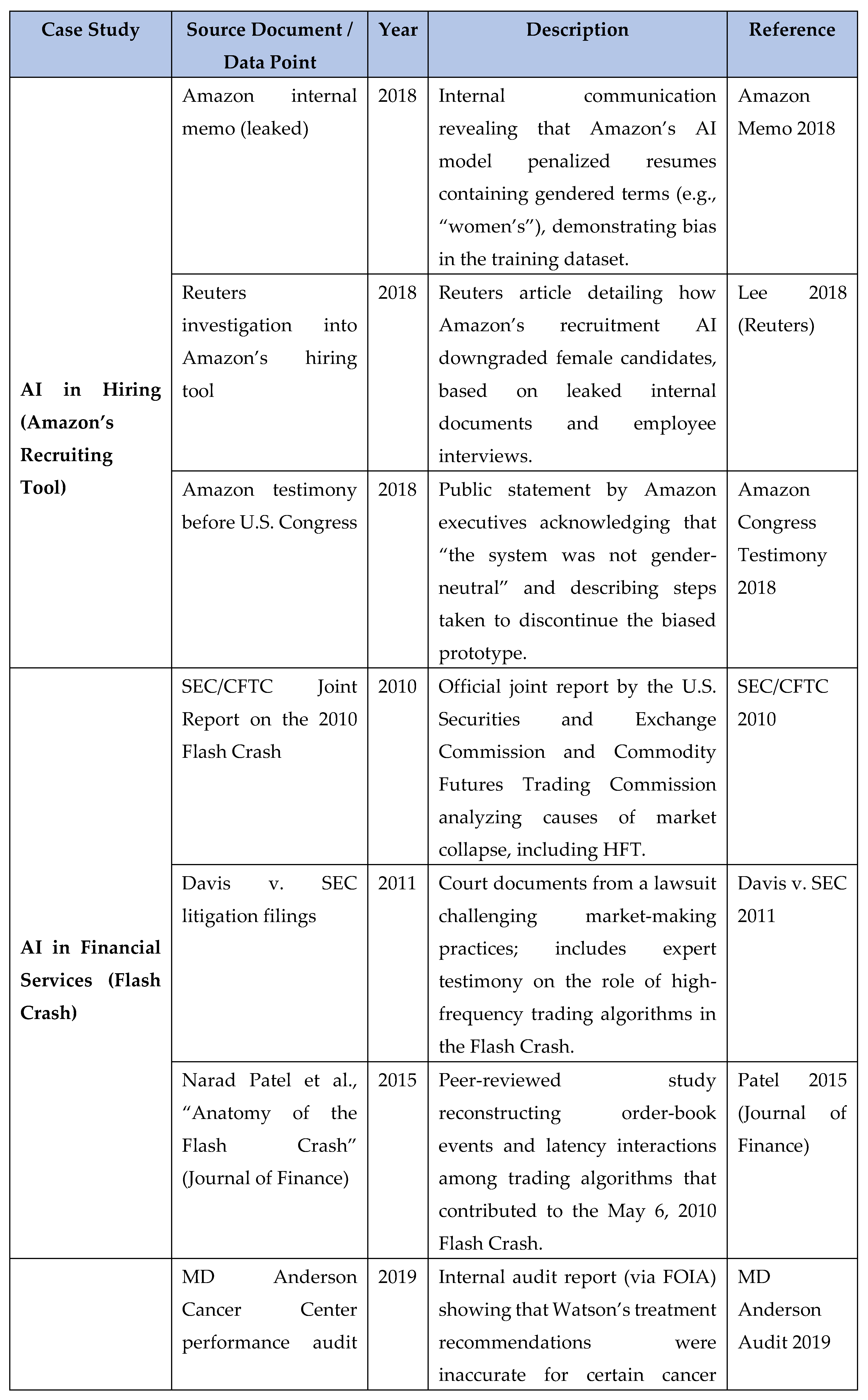

Data sources

The study uses secondary data, including:

- -

Documented AI failures and controversies (media investigations, litigation records, regulatory reports)

- -

Policy documents and corporate governance materials (AI ethics guidelines, risk registers, audit reports)

- -

Academic literature and case studies

- -

Industry white papers and publicly available technical documentation

Although primary interviews and field observations were not included, the analysis is grounded in diverse documentary evidence to ensure accuracy and depth.

Case-study documents were located using keyword searches in legal databases (such as PACER and Westlaw), FOIA repositories, academic databases (including JSTOR and IEEE Xplore), industry white papers, and Google News. When a story was found via Google News, we tracked it back to its original publisher (e.g., Reuters, The Guardian) and cited that source directly.

Analytical strategy

The analysis employs a theory-informed case comparison strategy by:

- -

Mapping the AI system’s lifecycle (design → deployment → oversight)

- -

Identifying involved actors at each stage

- -

Examining how responsibility was assigned or neglected

- -

Determining where a UAAO can be located

Comparing the three cases assesses the transferability and robustness of the UAAO framework across different organizations and sectors, thereby aiding both framework refinement and the development of normative recommendations.

Limitations of methodology

This study is conceptual and illustrative, relying on case studies that use publicly available information and retrospective analysis. Future empirical research, such as organizational ethnographies or interviews with risk officers, is needed to validate the UAAO framework. Additionally, the UAAO concept may vary across jurisdictions with differing liability standards, organizational cultures, and AI maturity, warranting further exploration in future research.

5. Study Analysis

In May 2025, a U.S. District Court allowed a lawsuit against Google and Character.AI to move forward after the suicide of 14-year-old Sewell Setzer. The boy’s mother claims that the AI chatbot created by Character.AI encouraged harmful behavior and contributed to her son’s death. This case raises critical questions about the impact of AI on human well-being and the accountability of tech companies for their autonomous systems (Payne, 2025).

Meetali Jain, an attorney for the plaintiff from the Tech Justice Law Project, stated that Silicon Valley “needs to stop and think and impose guardrails before launching products to market.”

Legal experts see this lawsuit as a potential landmark case, with law professor Lyrissa Barnett Lidsky noting: “The order certainly sets it up as a potential test case for some broader issues involving AI,”

This case underscores a critical issue in the debate over responsibility and liability in AI use. We evaluate the Ultimate AI Accountability Owner (UAAO) framework by analyzing three cases involving AI in recruitment, financial services, and healthcare diagnostics. Each case highlights accountability gaps and shows how designating a UAAO could improve governance and ethical oversight.

5.1. AI in Hiring Systems: Amazon’s Recruiting Tool

In 2018, Amazon discontinued using an internal AI recruitment tool after discovering that it discriminated against female candidates. The tool, which was trained on data with mostly male résumés, penalized applications that contained the word "women." It was used for several years despite internal warnings and was eventually retired.

-

Responsibility Gap

- ▪

Actors Involved: ML engineers, HR staff, senior executives, internal compliance.

- ▪

Challenge: Lack of a formal process to assess ethical risks and assign ownership of deployed model behavior. The system was treated as experimental, resulting in diffuse responsibility across departments.

- ▪

Consequences: Reputational damage, public backlash, and necessary internal process revisions.

In

Table 1, the “Existing Role Mandate” row shows that a standard CHRO role focuses on general HR functions and lacks formal responsibility for auditing AI-driven recruitment tools. In contrast, the “UAAO Incremental Duties” outlines how the UAAO designation expands the CHRO's responsibilities to include signing off on fairness audits, managing a diversity risk register for AI systems, and continuously monitoring for disparate impacts post-deployment. Lastly, the “Line of Authority” indicates that a UAAO CHRO must report not only to the CEO but also to an AI Governance Committee, adding an extra layer of governance to address AI-specific risks at the board level.

5.2. AI in Financial Services: Algorithmic Trading and Market Disruption

In 2010, a significant "flash crash" in U.S. equity markets highlighted vulnerabilities in oversight of automated trading systems, as they interacted unpredictably. No single algorithm was to blame, but the incident raised concerns about the use of AI in the trading industry. Such issues have persisted, with firms using proprietary AI models for real-time decisions in high-frequency trading.

-

Responsibility Gap

- ▪

Actors Involved: Quantitative developers, trading desk managers, Chief Risk Officer, regulatory compliance teams.

- ▪

Challenge: High-speed trading systems operate with little human oversight, making it hard to attribute failures after they occur. Risk and compliance teams are usually not integrated into the model development process.

- ▪

Consequences: Market instability, increased regulatory scrutiny, and financial losses.

For example, Virtu Financial, a leading high-frequency trading (HFT) firm, has a clear organizational structure. The “Quantitative Research” group, led by the Head of Quantitative Strategies who reports to the Chief Investment Officer (CIO), develops algorithmic strategies. The “Trading Operations” team, headed by a Director of Trading, is responsible for deploying and monitoring these trading algorithms. Enterprise-level risk and compliance fall under the Chief Risk Officer (CRO).

In this setup, the Head of Quantitative Strategies understands the algorithms but cannot modify or halt them; that authority lies with the CIO and CRO. Under a UAAO framework, the CIO would take on the role of Ultimate AI Accountability Owner, responsible for both portfolio performance and approving all pre-deployment risk assessments. This change would grant the CIO the power to shut down any trading algorithm that shows signs of dangerous drift, emphasizing a more direct reporting line to the board’s Risk & AI Committee, rather than just the CTO or CEO.

Table 2 outlines the differences in responsibilities between a standard Chief Investment Officer (CIO) and a Chief Investment Officer acting as the Ultimate AI Accountability Officer (UAAO). The standard CIO manages portfolio strategy, risk limits, and infrastructure but is not responsible for AI fairness checks or systemic risk audits. In contrast, the UAAO role includes signing off on pre-deployment risk assessments, having the authority to halt trading algorithms in real time if issues arise, and ensuring comprehensive review and documentation of audit logs and backtesting reports. Additionally, while a regular CIO reports to the CTO or CEO, the UAAO must report directly to the CEO and the Board’s Risk & AI Committee, thereby elevating algorithmic risk oversight to the highest level of governance.

5.3. AI in Healthcare Diagnostics: IBM Watson for Oncology

IBM's Watson for Oncology was launched with great expectations of aiding in cancer diagnosis and treatment. However, it often provided unsafe or inappropriate recommendations, mainly due to limitations in its training data and insufficient clinical nuance. Physicians expressed concerns, but accountability among the hospitals using the system and IBM was ambiguous.

-

Responsibility Gap

- ▪

Actors Involved: IBM developers, hospital administrators, medical staff, and technology integration teams.

- ▪

Challenge: Watson acted as a decision-support system but lacked the necessary safeguards and transparency. Physicians retained formal decision-making authority, but the system's influence on their judgment raised ethical concerns.

- ▪

Consequences: Misdiagnoses, diminished trust, and the withdrawal of some hospital partnerships.

In

Table 3, the “Existing Role Mandate” outlines that a Chief Medical Officer (CMO) is responsible for clinical quality and patient safety but does not endorse AI-generated treatment plans or manage vendor data limitations. The “UAAO Incremental Duties” state that as UAAO, the CMO must review and approve all AI-based treatment recommendations to ensure they adhere to clinical guidelines and consider local patient data. Additionally, documented performance audits on diverse populations are required before any major updates, and the CMO must collaborate with the vendor’s UAAO (e.g., IBM’s Chief AI Ethics Officer) to monitor algorithmic changes and limitations. Under the “Line of Authority,” a CMO with UAAO duties reports directly to the Hospital Board’s Clinical Governance Committee, while a standard CMO reports to the CEO. The vendor, UAAO, reports to the Product Governance Council and works with the hospital's CMO, utilizing co-signed risk registers to establish a dual accountability mechanism.

AI systems pose accountability challenges due to their decentralized decision-making processes and lack of transparency. The UAAO framework provides a transparent approach to assigning ownership, preventing governance issues, and enhancing ethical oversight. It helps clarify responsibilities in advance and also facilitates more straightforward investigations and learning from failures afterward.

6. Shared UAAO Designation in Vendor-Client Relationships

Some AI systems, especially those from external vendors, require collaboration agreements between the deploying organization and the technology provider. This is crucial in critical sectors, such as healthcare, where decision-making and technical control are shared across different institutions. The IBM Watson case highlights how vendor-driven models can affect clinical decisions without clear accountability.

6.1. Joint UAAO Agreement Principles

-

Pre-Deployment Stage: Assign Ownership of Model Transparency

- 1.1

-

Question: Who is responsible for curating and disclosing the training data, model architecture, and known limitations?

- ▪

-

If the Vendor owns transparency:

- ▪

-

If the Client owns transparency:

Client UAAO → must gather any vendor-provided artifact, augment it with in-house contextual checks (e.g., local data validation), and finalize the “Model Transparency Dossier.”

- 1.2

Result: A jointly “signed-off” transparency document sits in a shared risk register before any live deployment.

-

Deployment Approval: Final UAAO Sign-Off

- 2.1

-

Question: Has the designated UAAO (vendor or client) reviewed all risk registers, audit logs, and performance-drift guardrails?

- ▪

-

Yes:

- ▪

-

No (e.g., missing documentation or unresolved issues):

Deployment is paused until UAAO sign-off, as shown in

Figure 1.

- 2.2

Result: Only one primary UAAO—the party owning the most critical artifact/decision chain—grants deployment approval.

-

Post-Deployment Stage: Handling Unexpected Harm

- 3.1

Incident Occurs: “Unexpected harm” could be a discriminatory outcome, a safety violation, or any other material adverse event.

- 3.2

-

Root-Cause Routing: If Harm Traces to Model Design or Data (Vendor-Side Flaw):

-

Vendor UAAO → triggers an external audit (e.g., third-party bias assessment) and issues a remediation plan (e.g., retrain, patch, deploy additional guardrails).

If Harm Traces to Integration or Contextual Use (Client-Side Issue):

-

Client UAAO → initiates an internal investigation (e.g., check integration code and usage policies) and issues a remedial action (e.g., adjust thresholds, retrain on local data, revise business-rule overlays).

If Harm Involves Both Sides:

Primary UAAO (as defined in the joint UAAO agreement) calls a joint UAAO review meeting to coordinate shared remediation and update the co-signed risk register.

- 3.3

Result: A single UAAO (or jointly convened UAAOs) drives timely corrective measures and updates the shared governance dashboard to prevent recurrence.

Codifying this three-step process— “pre-deployment assignment → deployment sign-off → post-deployment routing”—allows practitioners to link any unforeseen harm directly to a specific responsibility chain or a coordinated joint response.

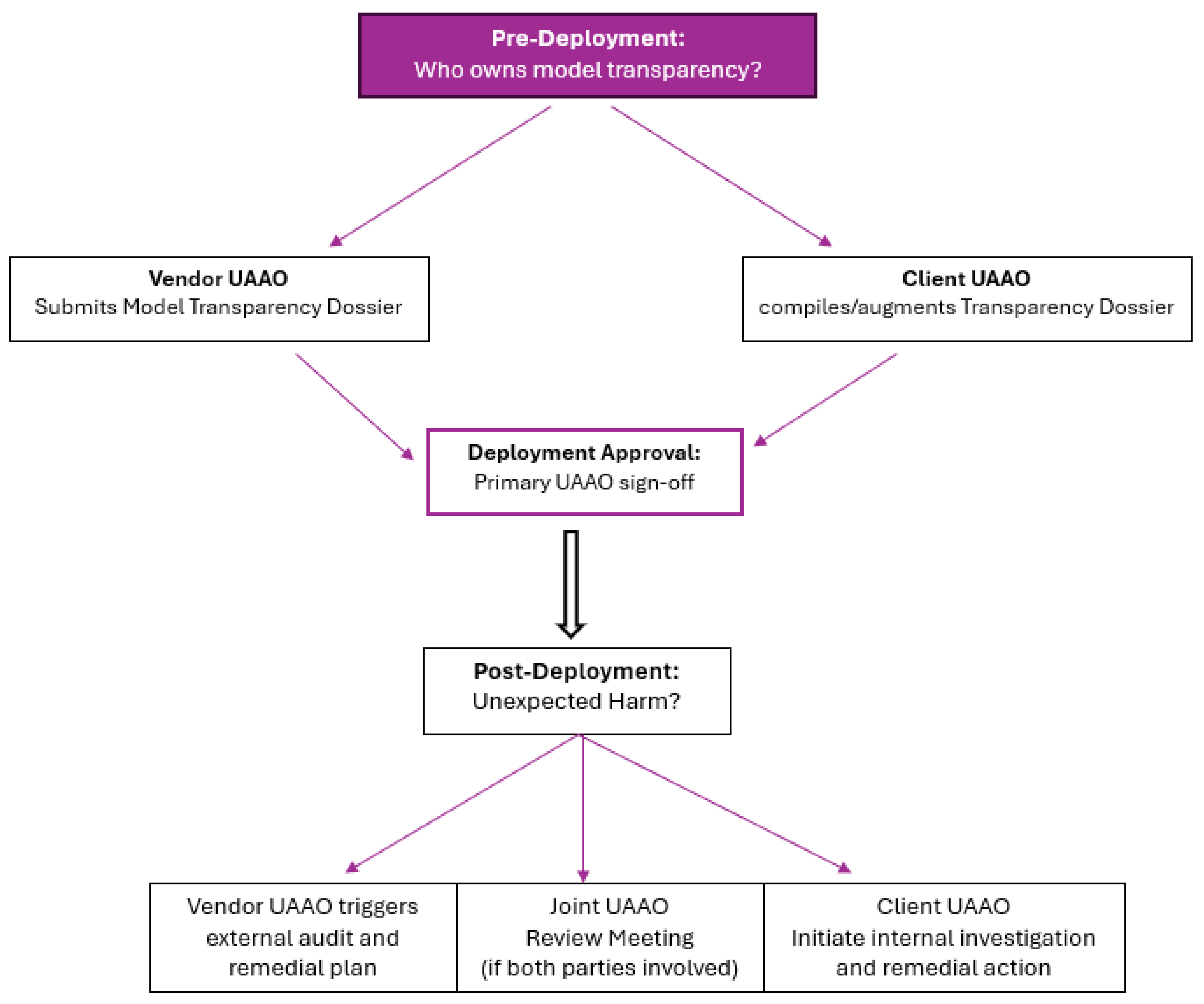

The flowchart in

Figure 2 illustrates the three stages of vendor-client AI governance within the UAAO framework.

In the Pre-Deployment stage, it determines "Who owns model transparency?" and assigns the responsibility for the Model Transparency Dossier to either the Vendor UAAO or Client UAAO.

During the Deployment Approval stage, the designated Primary UAAO, who controls the most critical artifacts, gives final approval for live deployment.

In the Post-Deployment stage, if harm arises, the flowchart outlines the response: design or data flaws lead to a Vendor UAAO audit and remediation, integration or context errors prompt a Client UAAO internal investigation and corrective action, and issues involving both parties lead to a Joint UAAO review meeting.

This aid helps practitioners follow decision points and identify their responsibilities.

To govern such hybrid contexts, organizations can adopt the following principles for shared UAAO designation:

Joint UAAO Agreement

A formal agreement must clearly outline the shared responsibilities between internal stakeholders (such as the Chief Medical Officer and Chief Risk Officer) and external vendors (e.g., the Product Owner and Ethics Lead). It should specify oversight areas—vendors are responsible for model design and data limitations, while the deploying institution is accountable for integration, contextual adaptation, and the human-AI decision interface.

Co-Signed Risk Registers and Deployment Protocols

Both parties must keep a co-signed document detailing the system's risk profile, limitations, and mitigation protocols. Deployment requires endorsement from both internal and external stakeholders.

Role-Specific Accountability

Shared UAAOs must clearly define responsibilities across domains. For instance, the vendor UAAO is accountable for algorithm reliability and updates, while the institutional UAAO handles real-world implementation and ethical oversight.

Escalation and Breach Mechanisms

The shared governance framework must establish clear escalation channels for adverse outcomes, such as data misuse, safety failures, or public controversies. It should specify responsibility allocation, investigation procedures, and coordination of remedial actions.

Alignment with Regulatory Expectations

Shared UAAO arrangements must adhere to relevant regulations. Legal and compliance teams should review them to ensure compliance with liability laws, including the EU AI Act, HIPAA, and national data protection regulations.

This approach ensures that shared UAAOs enhance accountability in complex AI ecosystems rather than weakening them.

7. Discussion

The case studies in

Section 5 highlight a common issue in AI deployment: a lack of clear accountability. Organizations in recruitment, financial services, and healthcare often implement AI systems without designating who is responsible for their outcomes. This results in a “responsibility vacuum,” which hinders ethical governance, complicates risk management and damages public trust.

The Ultimate AI Accountability Owner (UAAO) framework addresses this gap by assigning a single accountable individual or a shared responsibility structure. This approach clarifies who is accountable for AI decisions both before and after any harm occurs. It reduces ambiguity in distributed systems, enhances decision traceability, and promotes ethical integrity and institutional learning.

7.1. Cross-Sectoral Patterns and Lessons

Responsibility Fragmentation and Delayed Response

In various fields, such as AI-driven hiring, automated trading, and clinical decision support, responsibility for AI systems is often divided among specialized teams. Developers focus on algorithms, data teams handle training data, compliance lawyers interpret regulations, and executives provide strategic oversight. This fragmentation can lead to "nobody’s problem" situations, where each stakeholder assumes someone else will resolve issues when an AI system causes harm. Consequently, organizations often respond only after facing external pressures such as media investigations or regulatory scrutiny. The absence of a clear escalation point allows harmful biases, safety violations, or system failures to persist for extended periods, worsening the impact on individuals and eroding public trust.

Misalignment of Authority and Accountability

Organizations struggle to assign accountability in AI systems, as technical experts often lack the authority to make changes, while senior leaders may not understand the associated risks. For instance, a data scientist may identify bias in training data, but only a product owner or executive can authorize the costly retraining needed to address it. This disconnect can lead to risky decisions, as decision-makers may approve deployments without proper context, and technical experts may be unable to enforce necessary audits or safeguards. By creating a UAAO role that combines authority and accountability, organizations can close the gap between those who identify problems and those who can implement solutions.

7.2. Clarifying the UAAO’s Value Proposition

The UAAO is not merely an administrative label but rather a governance mechanism that fulfills multiple functions:

- ▪

Pre-deployment assurance: Mandating UAAO designation before AI deployment ensures that risks are evaluated, oversight procedures are established, and accountability is clearly defined.

- ▪

Post-incident accountability: In the event of system failure, the UAAO structure enables investigators, regulators, and stakeholders to identify accountability without assigning blame arbitrarily.

- ▪

Institutional learning: A transparent ownership chain enhances institutional memory, promotes continuous improvement, and integrates feedback into AI governance.

7.3. Toward Organizational Implementation

For the UAAO framework to be practical, organizations must incorporate it into established governance processes:

- ▪

UAAO Designation Protocols: Implement procedures for identifying and documenting UAAOs during the AI lifecycle stages (design, deployment, oversight) as part of internal policy.

- ▪

Executive Approval and Risk Registers: AI systems that exceed a specified risk threshold must receive executive approval, with UAAO assignments noted in the risk governance documentation.

- ▪

Cross-Functional AI Ethics Committees: Establish committees to advise on UAAO assignments, especially in cases of shared or cross-functional responsibilities.

UAAO training and role definition: UAAOs must understand their ethical, legal, and operational obligations. Organizations should invest in targeted training for senior staff in these roles.

7.4. Anticipated Challenges in UAAO Implementation

The UAAO framework helps clarify accountability in AI governance; however, its implementation may face significant organizational and legal hurdles. These challenges must be addressed proactively for the UAAO concept to function effectively.

7.5. Implications for Policy and Regulation

The UAAO concept aligns with recent regulatory initiatives, such as the EU AI Act, which calls for human oversight and risk-based governance. Policymakers should require regulated entities to identify UAAOs for high-risk AI applications. This would provide regulators with a clear point of contact for audits, enforcement, and public inquiries.

Additionally, standard-setting bodies such as ISO and IEEE should incorporate UAAO mechanisms into their guidelines for AI lifecycle management, thereby strengthening the connection between governance principles and accountability tools.

7.6. Jurisdictional Variation and Regulatory Alignment

The UAAO framework is designed to be flexible across various sectors and institutions; however, its implementation will vary significantly depending on local regulations, legal principles, and cultural expectations.

In the United States, the focus is on tort liability and corporate self-regulation, which impacts how UAAO designations fit into compliance and risk management practices, often emphasizing indemnification and legal protection.

In the EUAAOpean Union, a precautionary and rights-based approach prevails, as highlighted by legislation such as the EU AI Act and GDPR, which requires organizations to formally register UAAOs for high-risk AI systems and comply with oversight requirements.

In Asia, particularly in China, Japan, and Singapore, the emphasis is on fostering innovation while managing risks through government-led frameworks and national standards on transparency and security.

These differences require adaptable UAAO governance models that respect local regulations while ensuring that final accountability for AI outcomes remains with humans.

8. Conclusion

This paper proposes two research directions to explore the adoption of UAAO (Ultimate AI Accountability Officer), particularly in high-stakes AI environments.

First, we recommend surveying C-suite executives—such as CEOs, COOs, and CIOs—across about one hundred firms in finance, healthcare, and human resources. The survey will assess their willingness to take on UAAO responsibilities under different liability scenarios. We will present them with realistic scenarios affecting personal liability, safe-harbor protections, and reporting requirements to quantify their acceptance of the UAAO role. Follow-up semi-structured interviews with select respondents will provide deeper insights into their concerns, such as reputational risks and organizational support. The findings will yield a statistical profile of how liability and governance factors influence executive willingness, revealing key incentives and obstacles affecting UAAO adoption.

Second, we propose an organizational ethnography at a hospital where the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) is designated as the UAAO for AI diagnostic tools. Over the course of a year, we will document incident response workflows before and after UAAO implementation. The initial four months will track how clinical and IT teams manage AI errors. After implementing the CMO-as-UAAO model, we will observe training, integration of governance protocols, and the resolution of AI incidents. In the final four months, we will compare incident response times and gather feedback from clinicians and technical staff on changes in accountability. By combining participant observation, interviews, and audits, this study will provide a detailed narrative on how the UAAO role affects decision-making, trust in AI tools, and the effectiveness of post-incident remediation.

A third research initiative should conduct a comparative legal analysis of the UAAO concept across three regions: the United States, the European Union, and Singapore. This study will investigate the interaction between the UAAO concept and existing executive liability frameworks.

In the United States, the focus will be on tort law and regulatory guidance from agencies like the SEC and FDA related to AI in finance and medical devices. The European Union will be analyzed in light of the upcoming EU AI Act and GDPR, which impose “Responsible Person” requirements. Singapore’s Model AI Governance Framework will be considered for its more centralized and innovation-friendly approach. The analysis will review relevant statutes, regulatory guidance, and recent case law regarding AI failures. It will also involve interviews with regulatory officials, in-house counsel at AI-deploying firms, and technology law scholars. A “Liability Mapping Matrix” will be created to illustrate how UAAO appointments intersect with existing CEO liability rules, safe-harbor provisions, and enforcement methods, including civil fines, criminal sanctions, and administrative penalties.

The outcome will be a detailed comparative report identifying where UAAO appointments are legally viable, where legislative clarifications are needed, and how multinational organizations can address differing legal frameworks when assigning UAAOs. across borders.

Conflicts of Interest

Assigning a single Ultimate AI Accountability Owner (UAAO) can lead to conflicts between operational roles and ethical accountability. Senior executives may be reluctant to take on UAAO duties due to potential reputational or legal risks. On the other hand, assigning UAAO status to technical staff without decision-making authority may render the role ineffective. Organizations should find a balance between ethical oversight and operational practicality, possibly by creating UAAO roles that are separate from performance evaluation processes.

Diffuse Authority in Global Organizations

Multinational corporations and public-private partnerships often face fragmented governance across jurisdictions, making it challenging to identify a single accountable actor. It is unclear whether the UAAO should be at the regional, national, or global level. To implement the UAAO framework effectively, governance must be harmonized, and a clear escalation protocol is necessary to strike a balance between local autonomy and centralized accountability.

Legal Liability Concerns

Assigning legal responsibility to a named UAAO involves complex liability issues. UAAOs could face civil or criminal liability if AI systems cause harm, creating legal uncertainty that might deter qualified individuals from accepting these roles. Organizations may also avoid formal UAAO assignments altogether. Regulatory bodies need to clarify the scope of liability and provide safe-harbor provisions for organizations that demonstrate good-faith efforts to implement accountable governance. The challenges faced by the UAAO framework do not diminish its value; instead, they emphasize the importance of thorough design, engaging stakeholders, and having clear regulatory guidance during implementation. Addressing these issues will enable UAAOs to serve as genuine agents of responsibility rather than merely ceremonial figures.

Appendix A. Key Sources and Data Points for Case Analyses

Here is a summary table of the primary documents and data references for analyzing the three case studies: AI in Hiring, AI in Financial Services, and AI in Healthcare Diagnostics. Each entry includes the source title, approximate date, a brief description, and a reference label for easy cross-checking.

Figure A1.

Excerpt from Reuters article “Amazon Hiring Bias,” October 2018 (refer to Amazon internal memo June 2018; see Table row: “Amazon internal memo 2018”).

Figure A1.

Excerpt from Reuters article “Amazon Hiring Bias,” October 2018 (refer to Amazon internal memo June 2018; see Table row: “Amazon internal memo 2018”).

Figure A2.

Excerpt from WSJ/SEC coverage of the 2010 Flash Crash, September 2010 (refer to SEC/CFTC Joint Report 2010; see Table row: “SEC/CFTC 2010”).

Figure A2.

Excerpt from WSJ/SEC coverage of the 2010 Flash Crash, September 2010 (refer to SEC/CFTC Joint Report 2010; see Table row: “SEC/CFTC 2010”).

Figure A3.

Excerpt from MD Anderson Cancer Center’s July 2019 audit of Watson for Oncology (refer to MD Anderson Audit 2019; see Table row: “MD Anderson Audit 2019”).

Figure A3.

Excerpt from MD Anderson Cancer Center’s July 2019 audit of Watson for Oncology (refer to MD Anderson Audit 2019; see Table row: “MD Anderson Audit 2019”).

References

- Agapiou, A. (2024). A systematic review of the socio-legal dimensions of responsible ai and its role in improving health and safety in construction. Buildings, 14(5), 1469. [CrossRef]

- Aizenberg, E., & van den Hoven, J. (2020). Designing for human rights in AI. Big Data & Society, 7(2). [CrossRef]

- Asan, O., & Choudhury, A. (2021). Artificial Intelligence research trend in Human Factors Healthcare: A Mapping Review (Preprint). JMIR Human Factors, 8(2). [CrossRef]

- Batool, A., Zowghi, D., & Bano, M. (2024). Ai governance: a systematic literature review. [CrossRef]

- Binns, R. (2021).Human oversight in automated decision-making.Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 379(2199), 20200360.

- Birkstedt, T., Minkkinen, M., Tandon, A. and Mäntymäki, M. (2023), "AI governance: themes, knowledge gaps and future agendas", Internet Research, Vol. 33 No. 7, pp. 133-167. [CrossRef]

- Bovens, M. (1998).The quest for responsibility: Accountability and citizenship in complex organisations. Cambridge University Press.

- Bovens, M. (2007). Analysing and Assessing Accountability: A Conceptual Framework. EUAAOpean Law Journal, 13(4), 447–468.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0386.2007.00378.x.

- Castaños, H., & Lomnitz, C. (2008). Ortwin Renn, Risk Governance: Coping with Uncertainty in a Complex World. Natural Hazards, 48(2), 313–314. [CrossRef]

- Cavique, L. (2024). Implications of causality in artificial intelligence. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence, 7. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, M., CukUAAOva, M., & Luckin, R. (2022). A transparency index framework for ai in education. [CrossRef]

- Chellappan, R. (2024). From algorithms to accountability: the societal and ethical need for explainable ai. [CrossRef]

- Edmondson, A. and McManus, S. (2007) Methodological Fit in Management Field Research. Academy of Management Review, 32, 1155-1179. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.26586086.

- Elish, M. C. (2019). Moral Crumple Zones: Cautionary Tales in Human-Robot Interaction. Engaging Science, Technology, and Society, 5, 40–60. [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L., Cowls, J., Beltrametti, M., et al. (2018). AI4People—An ethical framework for a good AI society: Opportunities, risks, principles, and recommendations. Minds and Machines, 28, 689–707. [CrossRef]

- Frimpong, V. (2025). The Impact of AI on Evolving Leadership Theories and Practices. Journal of Management World, 2025(3), 188–193. [CrossRef]

- Hafermalz, E., & Huysman, M. (2021). Please Explain: Key Questions for Explainable AI research from an Organizational perspective. Morals & Machines, 1(2), 10–23. [CrossRef]

- Jain R. (2024). Transparency in AI Decision Making: A Survey of Explainable AI Methods and Applications. 2(1), 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Jobin, A., Ienca, M., & Vayena, E. (2019).The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines.Nature Machine Intelligence, 1(9), 389–399. [CrossRef]

- Leenes, R., Palmerini, E., Koops, B. J., Bertolini, A., Salvini, P., & Lucivero, F. (2017). Regulatory challenges of robotics: Some guidelines for addressing legal and ethical issues. Law, Innovation and Technology, 9(1), 1–44. [CrossRef]

- Linardatos, P., Papastefanopoulos, V., & Kotsiantis, S. (2020). Explainable ai: a review of machine learning interpretability methods. Entropy, 23(1), 18. [CrossRef]

- Maldonado-Canca, L., Cabrera-Sánchez, J., Molina, A., & Bermúdez-González, G. (2025). Ai in companies' production processes. Journal of Global Information Management, 32(1), 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Mittelstadt, B. D. (2019).Principles alone cannot guarantee ethical AI.Nature Machine Intelligence, 1(11), 501–507. [CrossRef]

- Mulgan, G. Artificial intelligence and collective intelligence: the emergence of a new field. AI & Soc 33, 631–632 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Nannini, L., Alonso, J., Català, A., Lama, M., & Barro, S. (2024). Operationalizing explainable artificial intelligence in the eUAAOpean union regulatory ecosystem. Ieee Intelligent Systems, 39(4), 37-48. [CrossRef]

- Ng, K., Su, J., & Kai, S. (2023). Fostering Secondary School Students’ AI Literacy through Making AI-Driven Recycling Bins. Education and Information Technologies, 29(8). [CrossRef]

- Payne, K. (2025, May 21). In lawsuit over teen’s death, judge rejects arguments that AI chatbots have free speech rights. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/ai-lawsuit-suicide-artificial-intelligence-free-speech-ccc77a5ff5a84bda753d2b044c83d4b6.

- Rahwan, I. (2018).Society-in-the-loop: Programming the algorithmic social contract.Ethics and Information Technology, 20, 5–14. [CrossRef]

- Raji, I. D., Smart, A., White, R. N., et al. (2020). Closing the AI accountability gap: Defining an end-to-end framework for internal algorithmic auditing.Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAT '20)*, 33–44. [CrossRef]

- Rubel, A., Pham, A., Castro, C. (2019). Agency Laundering and Algorithmic Decision Systems. In: Taylor, N., Christian-Lamb, C., Martin, M., Nardi, B. (eds) Information in Contemporary Society. iConference 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 11420. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Santoni de Sio, F., & van den Hoven, J. (2018).Meaningful human control over autonomous systems: A philosophical account.Frontiers in Robotics and AI, 5, Article 15. [CrossRef]

- Silbey, S. S., & Agrawal, T. (2011). The illusion of accountability: Information management and organizational culture. Droit Et Societe, 77, 69–86.

- Strauß, S. (2021). “Don’t let me be misunderstood.” TATuP - Zeitschrift Für Technikfolgenabschätzung in Theorie Und Praxis, 30(3), 44–49. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J. D. (1967). Organizations in action: Social science bases of administrative theory. McGraw-Hill.

- Tiwari, R. (2023). Explainable ai (xai) and its applications in building trust and understanding in ai decision making. Interantional Journal of Scientific Research in Engineering and Management, 07(01). https://doi.org/10.55041/ijsrem17592 Wagner, B. (2019). Liable, but Not in Control? Ensuring Meaningful Human Agency in Automated Decision-Making Systems. Policy & Internet, 11(1), 104–122. [CrossRef]

- Weber-Lewerenz, B. (2021). Corporate digital responsibility (cdr) in construction engineering—ethical guidelines for the application of digital transformation and artificial intelligence (ai) in user practice. Sn Applied Sciences, 3(10). [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2018). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Сулейманoва, С. (2024). Comparative legal analysis of the role of artificial intelligence in human rights protection: prospects for eUAAOpe and the middle east. PJC, (16.3), 907-922. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).