1. Introduction

The regulations that govern the way entities interact with each other are a fundamental aspect of modern business practice and determine the allocation of rights and responsibilities among the various stakeholders consisting of shareholders, managers, banks, employees, suppliers, and regulators. The classical governance model focuses on mitigating agency problems caused by information asymmetry and conflicting interests, as described by Shleifer and Vishny (1997). Advanced artificial intelligence (AI) for high-level decision-making is, however, disrupting the modern business world, reshaping corporate governance interactions, and introducing a new agent.

AI has transcended its role as a mere auxiliary tool that assists humans in decision-making and has evolved into an autonomous entity capable of making highly sophisticated decisions independently, optimizing corporate strategies, and reshaping the established governance mechanisms that have governed corporate behavior over time, as noted by Agrawal et al. (2018). The ability of AI to process and analyze big data, execute predictive analyses, and engage in continual upgrades through advanced machine learning techniques presents unprecedented challenges and opportunities to existing governance frameworks. While AI itself does not possess self-interest in the same manner that human agents do, its decision-making processes can still be influenced by biases that are inherent in the data upon which it is trained, as well as the opaque algorithmic structures that guide its operations, as discussed by Binns (2018).

This paper broadens the conventional governance framework by critically evaluating AI's status as an autonomous agent and exploring its complex relationship with traditional corporate governance stakeholders. It provides deeper insights into the evolving dynamics of corporate governance.

Corporate governance mechanisms fundamentally operate in response to agency problems, as highlighted by Shleifer and Vishny (1997). Managers who act as agents may pursue their interests at the expense of maximizing value for shareholders, who are considered the principals in this relationship.

These governance mechanisms traditionally have included legal protections, board oversight, executive incentives, and market forces. However, they were built with human actors in mind, and there is no analytical framework for dealing with AI-driven decision-making.

Technological developments also indicate that AI is not just a tool for automating managerial tasks but can affect strategic decisions, frequently operating outside universal oversight systems (Zeng et al., 2022). This pattern requires reshaping the governance frameworks to establish AI's responsibility, transparency, and ethical utilization.

2. Literature Review

Traditionally, corporate governance has been established to resolve agency conflicts (Kostyuk et al., 2018), and governance mechanisms were defined as protective measures against managerial opportunism (Shleifer & Vishny, 1997). These involve board oversight, legal protections, and executive incentives designed to make managers act in shareholders' best interests. Yet, the emergence of AI poses profound challenges to traditional governance institutions. This paper contributes to the conversation by analyzing AI as a self-governing authority stakeholder.

AI has been extensively studied in relation to organizational automation, efficiency gains, and predictive analytics (Agrawal et al., 2018; Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2017). AI's ability to process large data sets, conduct high-frequency trading, and optimize supply chains has transformed business operations. However, this paper goes beyond operational improvements, examining AI's systemic implications for governance, which are still vastly underexplored.

Transitioning from human decision-making to automated AI-based systems brings with it promises but also a great deal of risk. Crawford and Calo (2016) examine concerns over AI's opacity and its implications for accountability. Burrell (2016) makes a similar point about the opacity of AI decision-making, which makes it harder for regulators to oversee it. The studies, however, do not elucidate a possible regulatory mechanism to incorporate AI in governance frameworks; this paper intends to fill that gap.

Algorithmic bias and discrimination have also been deeply concerned due to the increasing involvement of AI in governance. O'Neill (2016) illustrates how credit scoring systems left to machines have perpetuated historical inequality, and Dastin (2018) documents instances of AI recruitment tools developing gender biases. The governance implications for these biases are important, with a need for algorithmic transparency and regulatory oversight (Veale & Binns, 2017). Current literature, however, is largely limited to ethical considerations and fails to address the alternative role of governance mechanisms. This paper fills the gap by proposing AI-specific governance structures like ethics committees and accountability mandates.

Moreover, Harari (2024) cautions against AI's rising autonomy and its corresponding capacity to consolidate power in economic and political structures. AI's role as a factor in shareholders' decisions, automation of managers' tasks, and control of financial transactions indicates a realignment of the balance of power in corporations. In contrast to prior studies that emphasize AI primarily as a tool (Baker & Wurgler, 2021; Ivanov & Dolgui, 2020), this paper advances AI as a governance agent capable of reinventing corporate hierarchies.

Traditional governance mechanisms assume humans have an interest in maximizing their utility; however, AI impartially uses optimization algorithms that do not have self-interest (Zeng et al., 2022). Such scenarios can give rise to different types of agency issues, where an AI strategy may be out of alignment with corporate goals. Almashhadani & Almashhadani (2022) discuss corporate governance, but they do not capitalize on AI decision-making paradigms. By comparison, the present paper uses these theories as a point of departure in order to include AI in the governance picture and reimagine hybrid governance schemes where human supervision would lend AI efficiency and the safety that it requires.

Much of the existing literature has been limited to AI-related impacts on employment (Frey & Osborne, 2017) or its role in financial risk estimation (Bussmann, 2021). However, AI's impact on the governance mechanisms themselves attracted scant attention. This study offers novel insights into AI's relationship with key stakeholders comprised of shareholders, managers, employees, and regulators, paving the way for adaptive governance regimes.

This paper contributes to the corporate governance literature:

Rethinking AI as a governance agent: While earlier works depict AI as a managerial tool used to supplement human decisions, we propose that AI emerges as a stand-alone governance actant, altering organizations in layers and subsystems.

Examining governance and regulation: In the tradition of Burrell (2016) and Veale & Binns (2017), we explore regulatory frameworks as mitigation strategies for governance risks (AI ethics committees; algorithmic transparency mandates).

Questioning the authority and role of human experts: Harari (2024) presents a future in which AI has the potential to dismantle human authorities that govern society, yet our contribution seeks to propose actual hybrid governance systems where mutual benefit between humans and AI is achieved.

Corporate strategic management to disrupt the nexus of politics and corporate power is a further research branch. Works in this stream have focused on governance (Shleifer & Vishny, 1997; O'Neil, 2016; World Bank 2019; Upor et al., 2019), corporate governance (Arora, 2016) or AI-specific ethical dilemmas (again, O'Neil, 2016).

This paper helps move from a people-centric model of governance by scrutinizing AI under governance structures. As AI becomes further integrated into corporate decision-making, it is critical to adjust governance mechanisms to include ethical oversight and accountability.

3. AI as a New Governance Agent

AI is emerging as an independent agent in corporate decision-making. AI is not merely a tool or a technological device that needs to be ignited by human action. It has become a self-operating system that makes strategic decisions, optimizes processes, and dictates the governance framework. This sequential pattern resonates with Harari (2024), who points out that since AI systems could take on roles previously held by human decision-makers, human leaders may become less relevant while corporations increase their efficiency.

The potential of AI to be an autonomous force of history, shaping economic, political, and social structures. AI can:

Influence decision-making: AI predictive power can help analyze and deduce from a wide range of data, often producing better decision-making outcomes than human agents.

Build Wealth: AI-empowered organizations can amass economic and political clout, siphoning it away from traditional human leaders.

AI lacks the intentions that make humans unique. It does not inherently have emotions, intent, or motives. It only acts based on the optimization of algorithms, leading to unexplored issues of governance and ethics.

Parallels with traditional corporate governance have the following implications:

The challenge of traditional corporate oversight of autonomous decision-making (e.g., trading and risk assessment);

Self-learning models evolve and sometimes magnify bias, creating governance risks;

Algorithmic opacity complicates the oversight of AI-powered decision-making, which is not unlike Harari, who finds AI manipulating public perception.

Consistently with these concerns, Harari (2024) sounds the alarm for strict governance of AIs, proposing:

AI Ethics Committees;

Requires Disclosure of Algorithmic Processes;

AI Accountability Mechanisms;

Hybrid Models of Human-AI Governance.

AI is a stand-alone entity engaged in executing strategies and optimizing organizational plans. It is shifting from a passive tool to an active force in human decision-making, and it may be undermining human agency in governance at corporate and political levels.

The rise of AI's influence in corporate governance signals a profound shift of power, and it inspires fears of an unchecked economic concentration driven by AI.

Even with this absence of human intent, AI is not exempt from its governance risks.

There may be, for instance:

AI-led fortification of ideological or economic injustices;

self-learning models that exacerbate these processes on a scale;

Algorithmic opacity that subverts accountability and scrutiny. For instance, healthcare AI can influence a clinician's judgment without obvious supervision.

AI systems are being increasingly used in corporate strategy, investment decisions, risk management, and regulatory compliance. With the advent of decentralized, emergent multi-agent systems that can autonomously conduct high-frequency trading, evaluate credit risk, and optimize supply chains, the pace of technological advancement has overtaken our capacity for traditional methods of governance (Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2017). AI "is not a man and does not have human intent like traditional agents, but it does have autonomous decision-making skills," raising fundamental governance issues of control and liability (Crawford & Calo, 2016).

AI also self-learns through machine learning, in which it constantly improves its decision-making processes through past data. This self-improvement ability also brings risks, as AI-based models can exacerbate systemic biases or evolve beyond human interpretability (Rudin, 2019). Therefore, corporate governance - which encompasses everything without controlling everything - should include dynamic oversight mechanisms for the ongoing learning processes unfolding in AI.

Algorithmic black boxes, with their undetectable information asymmetries, present a huge challenge to AI governance. Black-box models, especially in the case of deep learning, obscure how AI-driven outcomes related to a firm get derived, shielding them from scrutiny from shareholders and regulators alike (Burrell, 2016). In the absence of explainability, AI-based governance tools may amplify asymmetries rather than curtail them.

While AI itself has no self-interest, it has the potential to create novel forms of agency problems, especially when its optimization goals drift away from shared corporate objectives, such as market value maximization. Yet, in financial services, AI has been shown to reinforce credit discrimination when trained on biased historical data. (O'Neil, 2016). This has created a need for strong algorithmic auditing and fluid governance structures to address these challenges.

4. AI's Interaction with Corporate Governance Stakeholders

Algorithmic trading and AI-driven investment strategies (Baker & Wurgler, 2021) have transformed shareholder engagement. However, the opacity of AI-generated financial models makes shareholder oversight more difficult. The AI model has the potential to cause distortions in the financial market, so governance frameworks should ensure that there are transparent rules for AI-driven asset management.

AI is already automating the most basic managerial tasks, from strategy formulation to risk assessment to performance appraisal, raising existential quandaries around executive accountability. If AI-generated decisions result in corporate failures, then legal frameworks should clarify how liability is attributed (Arora et al., 2020). Companies need hybrid governance structures that pair human responsibility with AI efficiency.

The wave of job loss and disruption due to AI-driven automation demands that corporations adopt comprehensive workforce re-skilling and adaptation policies (Frey & Osborne, 2017). Implementing transparent AI is also necessary for ethical governance so that efficiency gains can be balanced with social responsibility. AI in hiring and performance evaluations also requires oversight to avoid discrimination and abuse of workers (Dastin, 2018).

A key feature of AI-powered supply chain management is predictive analytics that minimizes inefficiencies in procurement.

While AI-led customization boosts customer interaction, it also poses ethical questions about data privacy and algorithm bias (Zarsky, 2016). Governance mechanisms should ensure algorithmic accountability and abide by consumer privacy laws that protect against behavioral analytics manipulation through targeted marketing techniques.

Data needs vary, but some common challenges include integrating AI-based credit risk assessments for efficiency with fairness and long-term regulatory compliance (Bussmann, 2021), ensuring responsible management of financial data, especially transaction histories, to build trust between end-users and data collectors, and managing systemic relations between traditional, legacy `first tier' infrastructure systems with newer AI technologies (Heidarzadeh et al. 2022). Governance frameworks that can ensure that lending decisions based on AI are compliant with the anti-discrimination laws and the ethics of financial services must be decreed.

Regulators are increasingly using AI to monitor corporate compliance. Yet, responding to new AI paradigms and providing timely solutions is challenging due to the rapid evolution and deployment of AI systems before the existing laws for their governance are complete and capable of offering viable solutions (Veale & Binns, 2017). Policymakers need to work with AI ethicists to create guidelines on how companies use AI.

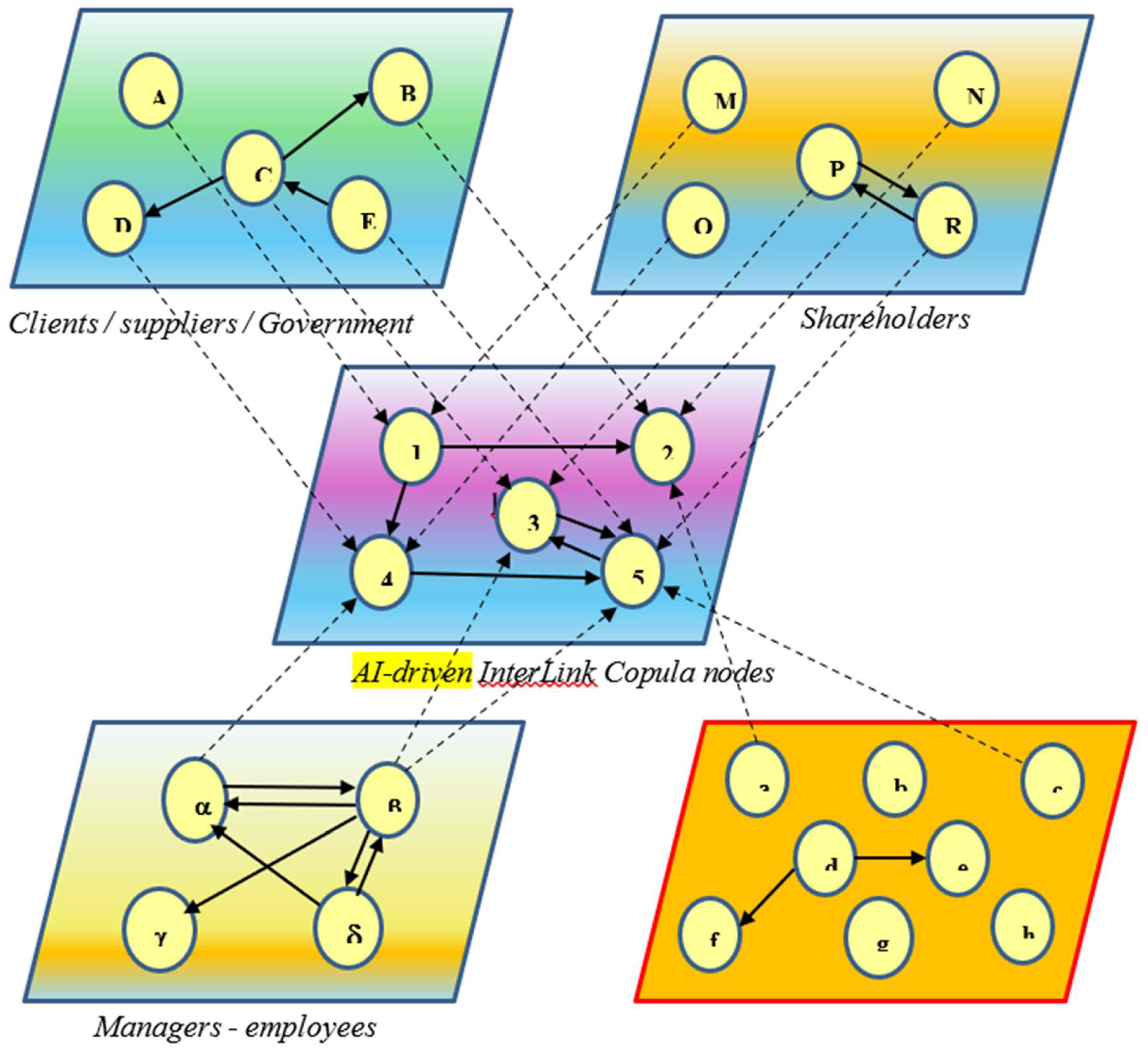

Figure 1 describes AI's interactions as an agent with other stakeholders through multilayer networks and connecting copula nodes.

5. Toward an AI-Integrated Governance Framework

With AI systems' growing role in corporate decision-making, there is an urgent need to establish a governance framework that enables transparency, accountability, and ethical governance. Though AI scaffolds efficiency and prediction capacity in corporate frameworks, its opacity and potential for unintended biases—including in hiring and other HR processes—create no small challenges, too. A contemporary governance framework needs to include AI-specific oversight mechanisms to meet these challenges.

To ensure that humans govern the machines, we need to organize ourselves. AI Ethics Committees can be created at the corporate level to oversee AI-driven policies for adherence to ethical and legal standards. These committees would have the following responsibilities:

Reviewing AI algorithms for bias and fairness.

Ensuring that AI is used ethically to make decisions — including in fields like hiring and lending and risk assessment.

Implement responsible AI strategies as advisors to corporate boards and executives.

State data to comply with changing AI governance rules

AI Ethics Committees can serve as a systemic safeguard against unethical practices and help build trust among stakeholders by creating independent oversight bodies within private organizations.

Decision-making processes powered by AI should fall under disclosure requirements that are broad enough to allow for understanding and auditing. Many present-day black-box models obfuscate decision-making processes, complicating challenges and stakeholders' comprehension of outcomes (Burrell, 2016).

Governance frameworks should require the following:

Explainability standards should govern AGI: AI models must be developed to deliver understandable rationale for their decisions, especially for high-stakes decisions across finance, hiring, healthcare, and others.

Regular AI Audits: Corporations should be mandated to undergo independent audits of AI-driven decision-making processes to detect biases and any unintended consequences.

Public disclosure: Organizations must publish transparency reports on how their AI systems work and which safety systems have been designed and validated, especially if AI systems affect large-scale decision-making (e.g., financial markets, credit scoring, public services).

Algorithmic transparency can also help ensure that AI decisions are still accountable and have not been biased in favor of certain stakeholders over others.

With increased autonomy in corporate governance comes the need to clearly define accountability frameworks around AI systems in organizations to clarify responsibility for potential errors they may generate. Traditional governance mechanisms had human executives and managers who were accountable for the decisions they made, but AI creates a more complex problem regarding liability.

Accountability measures should include holding organizations that deploy AI responsible for harm caused by AI-driven decisions (e.g., financial losses, discrimination, misinformation).

AI Decision Appeals Process AI decisions can be appealed. Those affected by AI decisions (e.g., employees and customers) will have a process to appeal and challenge the decisions made.

So, by enacting crystal-clear accountability criteria, organizations can ensure that AI aligns with the company's goals and the interests of the stakeholders.

Harari (2024) advocates for a hybrid AI governance model that allows human demands to perpetually counterbalance the efficiency of corporate AI decision-making with ethical corporate decisions. Such a roadmap would ensure that AI does not run amok but rather becomes integrated into pre-existing governance matrices with proper safeguards in place.

We should make sure that a hybrid model consists of the following:

Human-in-the-loop (HITL) Systems: AI should augment rather than replace human decision-making in high-stakes governance domains.

Designing AI for Ethics: AI should be able to operate within ethical limits defined by both corporate culture and regulatory environments.

AI governance frameworks must also be adaptive to rapidly changing technology, which means corporate governance frameworks built on developing and implementing AI must adapt to new technology.

By balancing AI's efficiency with humans' ethical oversight, corporations can develop governance frameworks that maximize AI's benefits while minimizing its risks.

A notable challenge in AI corporate governance is the regulatory lag in catching up to AI's rapid growth. There is a governance gap because political and economic institutions have shown themselves historically resistive to the adaptive demands of technological disruption.

AI regulations need to be coordinated internationally to avoid regulatory arbitrage, whereby companies take advantage of differences between jurisdictions.

Companies deploying AI in governance should be obliged to carry out regular impact assessments, similar to the environmental impact assessments countries conduct before proceeding with mega infrastructure projects. These assessments would consider the ethical effects, financial factors, and social consequences of decision-making algorithms.

Organizations must comply with AI governance mandates, and regulatory agencies must have the authority to sanction those who disregard compliance requirements. By closing regulatory gaps, policymakers will ensure that AI's potential in corporate governance is harnessed and used for the good of society.

The broader application of AI in corporate governance creates systemic risks that necessitate proactive governance measures. Regulating AI is a complex endeavor, requiring a balance between fostering innovation and safeguarding the financial system from potential disruptions driven by AI, including financial instability, market manipulation, and the reduction of human oversight in corporate decision-making processes.

AI governance frameworks need to be risk-based, especially if they concern high-risk AI applications (e.g., financial trading algorithms, credit scoring models, and corporate decision-making tools)

Rather than retrofitting ethics frameworks post-AI deployment, organizations should design with ethical implications in consideration from the outset.

Given the rapid evolution of AI governance challenges, companies need to trial innovative governance models, such as AI-enabled advisory panels for boards or stakeholder-inclusive AI oversight entities.

A proactive approach to AI governance helps ensure that corporate governance frameworks are flexible enough to adapt to the requirements of AI-driven business transformations.

With AI emerging as a predominant force in corporate decision-making, governance frameworks must evolve to meet the specific challenges posed by AI. Such a governance framework that keeps pace with AI integration will have to encompass the establishment of ethics committees, algorithmic transparency mandates, accountability mechanisms that will cover the question of liability in these systems, etc.

Additionally, a hybrid governance model that achieves a balance between AI efficiency and human oversight is paramount in preventing unchecked power from accumulating in AI systems. AI governance cannot be left behind as the technology innovates—there needs to be a trailing reaction so they can work properly together. It accomplishes this through global AI standards, compulsory impact assessments, and enforceable mechanisms to curb the risks of AI-based decision-making.

In short, we must establish rules for AI so that humans retain overall control and systemic risks can be mitigated through proactive systems of governance.

6. Discussion

The paper explores the relationship of AI within corporate governance, suggesting that AI is more than a tool but a new stakeholding agent. This paper has made substantial contributions to a number of areas but also has left certain limitations and directions for future work.

The radical departure from the human-centric governance model is the introduction of AI as its autonomous governance agent, which is what the paper is all about. This study challenges prior studies that depict AI as an adjunct to managerial decision-making (e.g., Agrawal, Gans, & Goldfarb, 2018; Brynjolfsson & McAfee, 2017) that are essentially managerial-centric as AI actively shapes decision tools and processes, which in turn shapes power and agency relations in the corporation. In doing so, this extends the Shleifer and Vishny (1997) framework that was designed for human agents to an AI-centric corporate world. This has prompted the need for AI-specific governance mechanisms that respond to concerns about the dangers of algorithmic opacity and regulatory lag flagged by scholars such as Burrell (2016) and Veale & Binns (2017).

The paper steps away from a theoretical discussion to provide practical governance solutions that can be implemented in reality, and that can be useful but not limited to policymakers and corporate leaders.

The paper considers ethical concerns in the governance discussion, including the threats of algorithmic bias (O'Neil, 2016) and unintended consequences in automated decision-making (Crawford & Calo, 2016). The study's emphasis on the intersection of AI governance and wider ethical considerations further highlights the necessity of flexible, context-sensitive regulatory mechanisms, in line with recent appeals for corporate accountability in the AI landscape (Harari, 2024).

The paper connects corporate governance, AI, ethics, and regulatory policy. This study differs from previous research, which addresses these topics in isolation (Frey & Osborne, 2017; Baker & Wurgler, 2021), as it draws upon insights across disciplines, spanning finance, management, and technology studies. Such a comprehensive view enhances the significance and relevance of the paper.

The paper provides an innovative theoretical ground but no data to back its arguments. If there are case studies or examples of corporations using AI to impact major decisions like acquisitions or who makes it to the Boardroom table, then such a discussion would only have been enriched. For example, Ivanov & Dolgui (2020) and Bussmann (2021) have demonstrated how AI is a source of research for financial risk assessment and the food supply chain. However, the paper lacks specific examples of firms adopting new AI-supported governance structures.

Likely, the claim that AI acts as a fully autonomous governance agent may be exaggerated. Though machine learning algorithms may shape future decisions, they are ultimately merely a system designed and governed by other actors. This raises an important and interesting discussion that the paper could go further into with regard to the extent to which AI is able to act independently in heavily regulated industries. This autonomy is still very much limited by various regulatory, technical, and ethical limitations (Almashhadani & Almashhadani, 2022; Naciti, Cesaroni, & Pulejo, 2022).

While the paper offers AI-specific governance solutions, it fails to fully grapple with the barriers to implementing these frameworks. While algorithmic transparency mandates and AI ethics commissions are welcome additions to the digital architecture, there is also a need for coordination and enforcement across jurisdictions with vastly different legislation, which is challenging at best. A more in-depth analysis of regulatory feasibility, for instance, drawing on literature on business and securities law (K22), would contribute to the paper's practical relevance.

AI can help improve decision-making and enhance features of decision-making efficiency, less human bias, and better stakeholder engagement (Baker & Wurgler, 2021). There is a way for more nuance between the risk and reward associated with the use of AI in governance.

To overcome the limitations above, future research should:

refer to case studies and quantitative analyses to validate the importance of AI in corporate governance.

Explore industry-specific differences in AI governance, given that AI could have a disparate impact on sectors such as finance, health care, and manufacturing.

investigate cross-jurisdictional challenges in the regulation of ethical AI and suggest pathways for capitalizing on existing norms.

analyze the long-term impact of AI on corporate decision-making, especially around shareholder rights and management responsibility.

By reconceptualizing AI as an autonomous governance agent and developing new regulatory paradigms around it, this paper adds to the growing conversation around AI and corporate governance. Yet criticisms surrounding its underside of slight empirical basis, possible overemphasis on the autonomy relevant to AI, and limited depth of discussion on regulatory feasibility reveal opportunities for further refinement. Future studies can expand on real-life case studies that demonstrate provisions for AI-specific governance mechanisms. As limited as it is, the study is an important first step in figuring out how to adapt corporate governance to the era of AI.

7. Conclusion

The current corporate governance framework is now being undermined by the entrance of AI and machine learning, which alters the entire equation of this model by promoting AI and tech performance and optimization as the main drivers of corporate input and outcome. We will argue here that AI is not only an auxiliary tool but an emerging governance agent that can influence corporate decision-making, affect stakeholder interactions, and alter the dynamics of economic power. Still, with no self-interest but trending towards self-automation by optimizing strategies, evaluating risks, and executing high-frequency transactions, calls for new governance mechanisms that foster accountability, ethical oversight, and transparency.

A significant contribution of this research is building on classical corporate governance theories to support AI-driven decision-making. While previous literature tends to portray AI as a management production tool for greater efficiency, this paper provides an alternative perspective by which AI can be seen as an entity engaging traditional governance stakeholders in ways that were once the sole purview of human actors. Hence, hybrid governance models need to be devised to blend human oversight with AI-led decision-making procedures so that these processes remain in alignment with overarching corporate goals and ethical values.

The study emphasizes the need for AI-specific frameworks of governance, which include:

Corporate AI deployments to be overseen by ethics committees;

Transparency by design to mitigate the risks of black-box decision-making;

Regulatory oversight levers to determine fairness in AI-based financial and employment decisions;

This may happen when hybrid governance models are developed that blend the efficiency of the AI mind with the ethical and social judgment of the human mind.

However, the paper outlines some important challenges that still need to be worked out. AI systems create open-ended self-learning capabilities, which leads to increased uncertainty, liability, and regulatory difficulties. However, AI's efficiency-enhancing powers could also be implemented in governance structures, which could suffer from bias, opacity, and unexpected shifts in power. This again addresses a very recently politicized and addressed topic, and the practical realization of AI governance mechanisms remains an open challenge, especially across the global legal and regulatory landscape.

Future research could utilize empirical validation of AI's role in governance through case studies and industry-specific analyses. As AI continues to evolve, it will be important to analyze its long-term impact on corporate decision-making, shareholder engagement, and labor markets. Timely response to the challenges entails co-creating adaptive regulatory structures that facilitate the co-evolution of progress and ethics.

The integration of AI into corporate governance is an area of great potential transformation. Still, it also introduces a complex set of risks that will require a proactive governance approach to navigate. That evolution will require an interdisciplinary approach that unites technology, regulatory, and ethical discussions, aligning AI-powered decisions and larger corporate and societal objectives. Governance will not be about AI supplanting human judgment; instead, it will be a finely-tuned partnership between AI productivity and human supervision (Moro-Visconti, 2024) - a relationship that will determine the next era of corporate decision-making.

References

- Agrawal, A., Gans, J., & Goldfarb, A. (2018). Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence. Harvard Business Review Press.

- Aguilera, R.V.; Aragón-Correa, J.A.; Marano, V.; Tashman, P.A. The Corporate Governance of Environmental Sustainability: A Review and Proposal for More Integrated Research. J. Manag. 2021, 47, 1468–1497. [CrossRef]

- Almashhadani, H. A., & Almashhadani, M. (2022). An overview of recent developments in corporate governance. International Journal of Business and Management Invention, 11(5), 39-44.

- Arora, A., Branstetter, L., & Drev, M. (2020). The Changing Economics of Knowledge Production. Research Policy, 49(2), 103865.

- Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2017). Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Burrell, J. How the machine ‘thinks’: Understanding opacity in machine learning algorithms. Big Data Soc. 2016, 3. [CrossRef]

- Dastin, J. (2018). Amazon Scraps AI Recruiting Tool That Showed Bias Against Women. Reuters.

- Ellili, N.O.D. Bibliometric analysis on corporate governance topics published in the journal ofCorporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society. Corp. Governance: Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2022, 23, 262–286. [CrossRef]

- Frey, C. B., & Osborne, M. A. (2017). The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation? Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 114, 254-280.

- Gillan, S.L. Recent Developments in Corporate Governance: An Overview. J. Corp. Financ. 2006, 12, 381–402. [CrossRef]

- Harari, Y. N. (2024). Nexus: A brief history of information networks from the Stone Age to AI. Vintage Publishing.

- Kostyuk, A.; Mozghovyi, Y.; Govorun, D. Corporate governance, ownership, and control: A review of recent scholarly research. Kostyuk, A., Mozghovyi, Y., & Govorun, D.(2018). Corporate governance, ownership, and control: A review of recent scholarly research. Corp. Board: Role, Duties Compos. 2018, 14, 50–56. [CrossRef]

- Moro-Visconti, R. Natural and Artificial Intelligence Interactions in Digital Networking: A Multilayer Network Model for Economic Value Creation. J. Compr. Bus. Adm. Res. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Naciti, V.; Cesaroni, F.; Pulejo, L. Corporate governance and sustainability: a review of the existing literature. J. Manag. Gov. 2021, 26, 55–74. [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. The journal of finance, 52(2), 737-783.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).