Submitted:

19 November 2025

Posted:

20 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

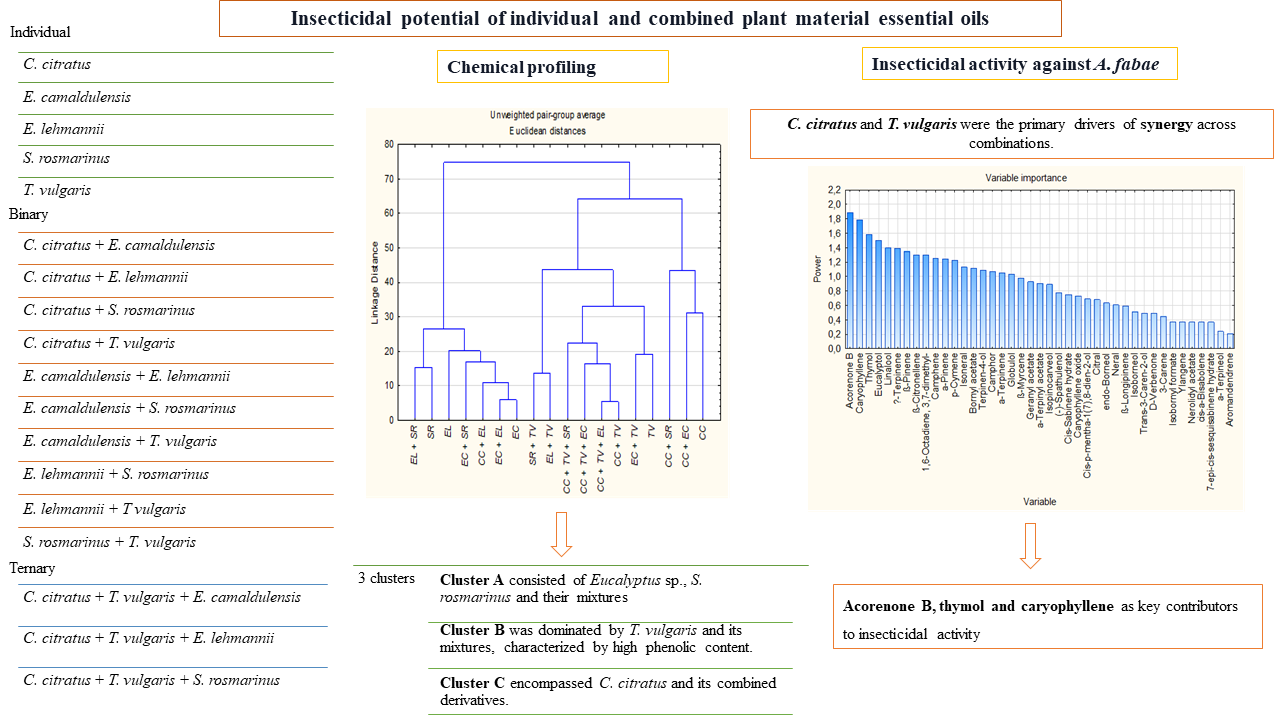

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Chemical Composition of Individual and Combined Plant Material Essential Oils

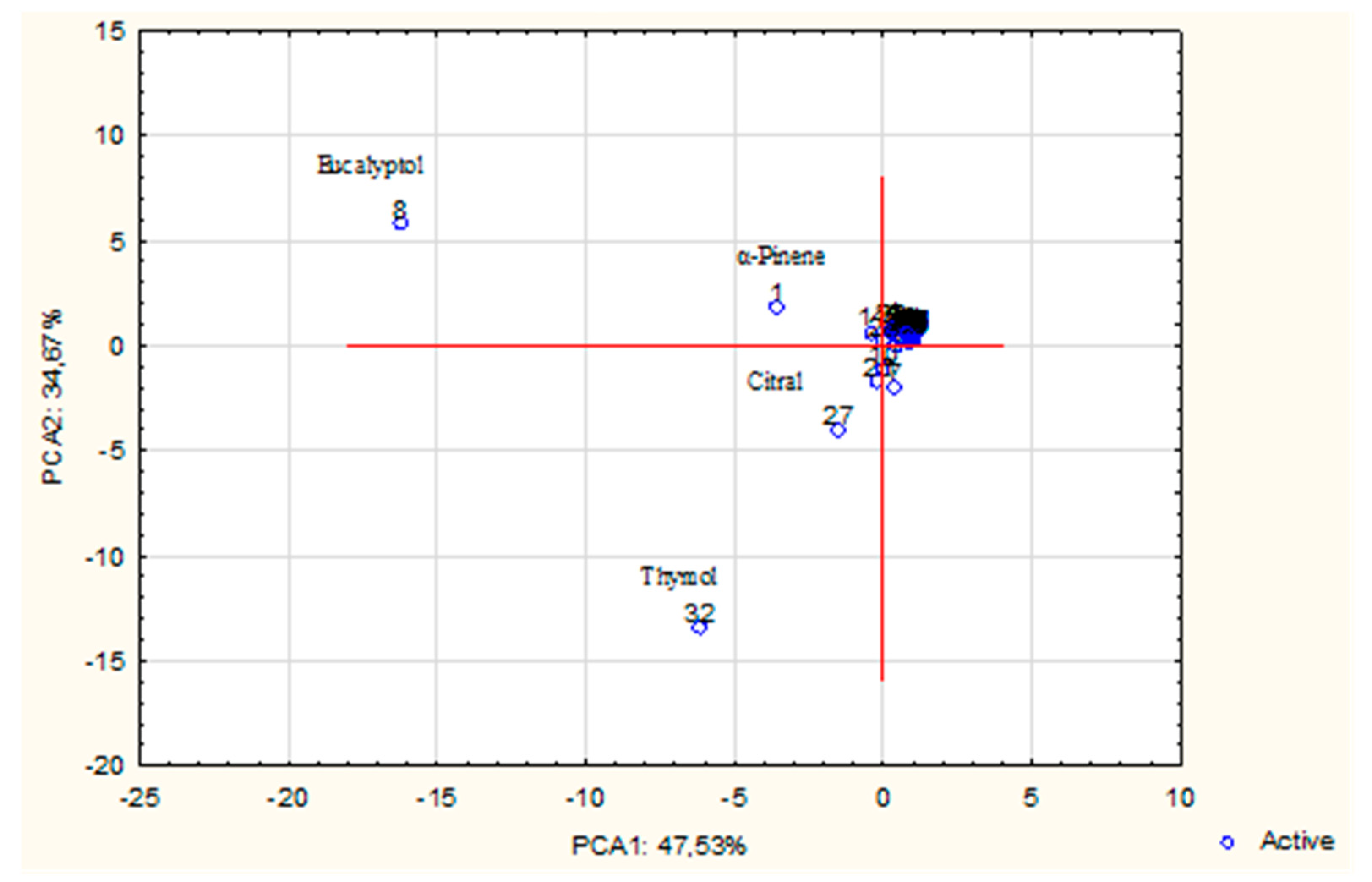

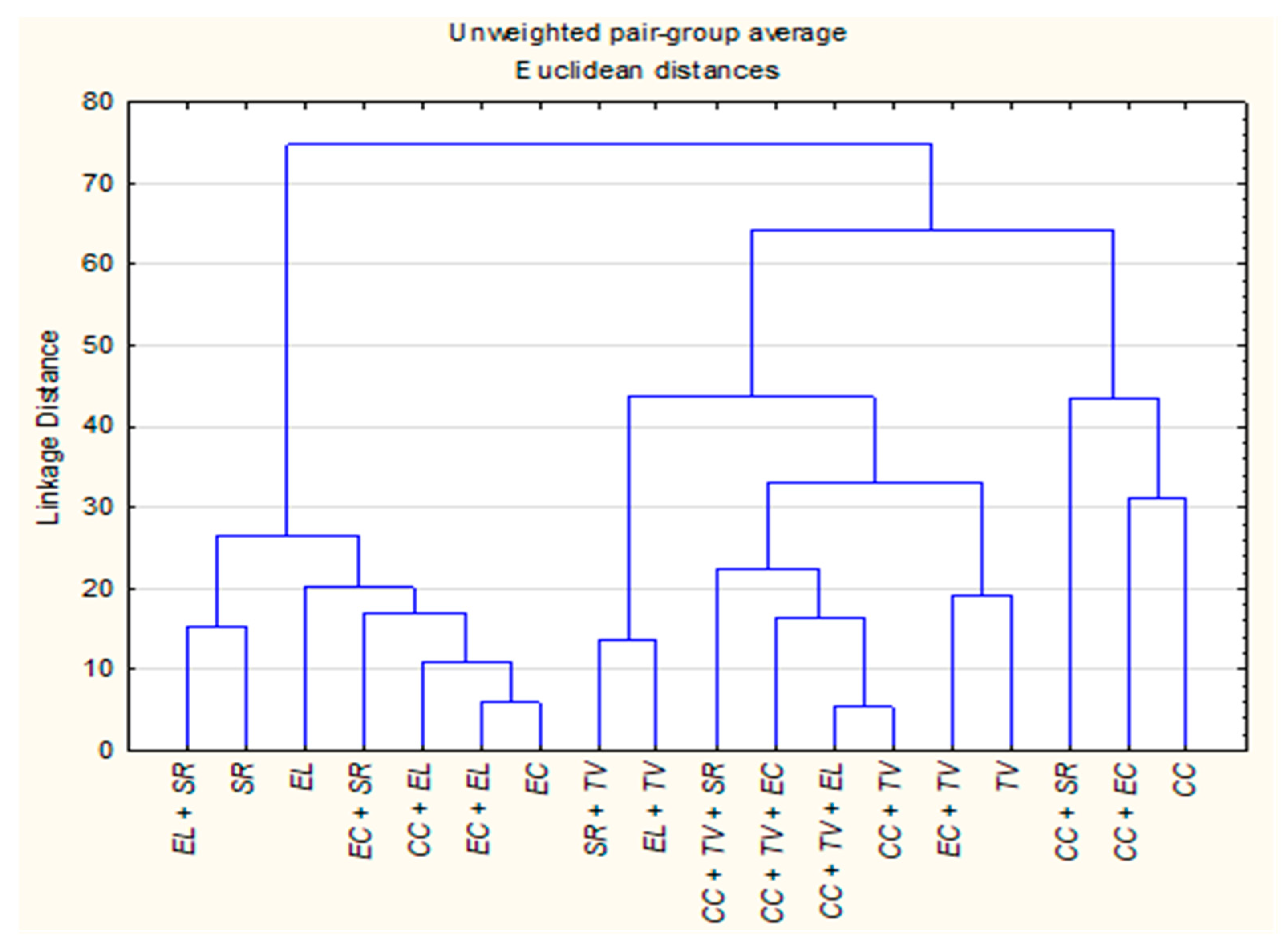

2.2. Multivariate Analysis of Essential Oil Compositions

2.2.1. Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

2.2.2. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA)

2.3. Insecticidal Activity

2.3.1. Probit Analysis of Individual and Combined Plant Material Essential Oils

2.3.2. Assessment of Synergistic Interactions Using Co-Toxicity Coefficient and Synergistic Factors

2.3.3. Correlation and Regression Analysis Based on LC50

Pearson Correlation Between Major Constituents and LC50 Values

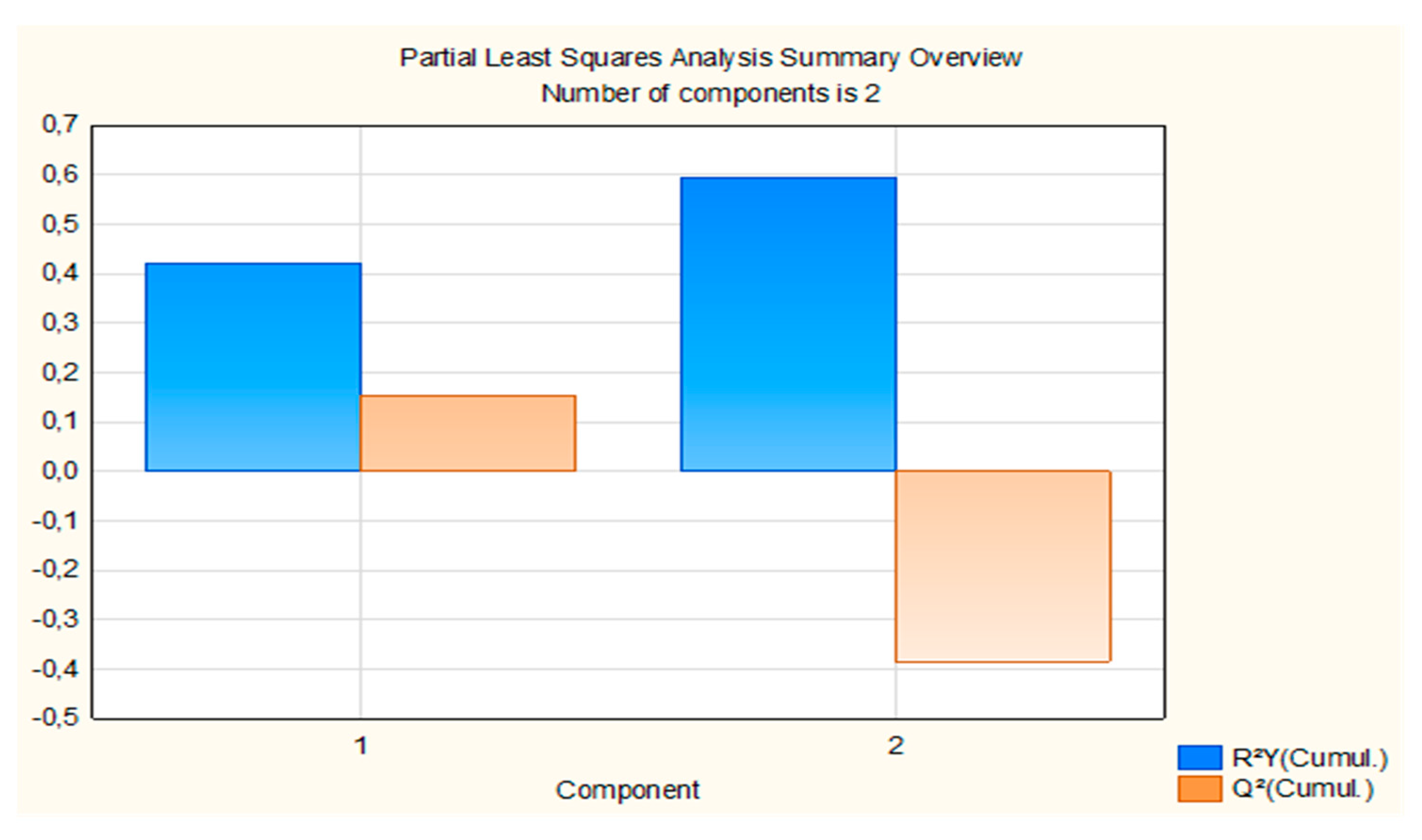

Partial Least Square Regression Modeling

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Essential oil Extraction and Combinations

4.3. Gas Chromatography Mass Spectrometric (GC-MS) Analysis

4.4. Insecticidal Activity

4.4.1. Aphid Sampling and Rearing

4.4.2. Contact Toxicity Bioassay

4.4.3. Interaction Assessment

4.5. Statistical and Chemometric Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Loukili, E.H. , Fadil, M., Elrherabi, A., Er-Rajy, M., Taibi, M., Azzaoui, K., Salghi, R., Sabbahi, R., Alanazi, M.M., Rhazi, L., Széchenyi, A., Siaj, M., Hammouti, B. Inhibition of carbohydrate digestive enzymes by a complementary essential oil blend: in silico and mixture design approaches. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1522124. [Google Scholar]

- Nebié, B. , Dabiré, C.M., Bationo, R.K., Soma, D.D., Namountougou, M., Sosso, S., Nebié, R.C.H., Dabiré, R.K., Palé, E., Duez, P. Investigation on chemical composition and insecticidal activity against Anopheles gambiae of essential oil obtained by co-distillation of Cymbopogon citratus and Hyptis suaveolens from western Burkina Faso. Malar. J. 2024, 23, 339. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Soulaimani, B. Comprehensive review of the combined antimicrobial activity of essential oil mixtures and synergism with conventional antimicrobials. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2025, 20, 1934578 × 251328241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N. Synergy, additive effects, and antagonism of drugs with plant bioactive compounds. Drugs and Drug Candidates 2025, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seukep, A.J. , Ojong, O.C.G., Mbuntcha, H.G., Matieta, V.Y., Zeuko’o, E.M., Kouam, A.F., Kuete, V., Ndip, L.A. In vitro antibacterial potential of herbal beverage extracts from cinnamon, clove, and thyme and their interactive antimicrobial profile with selected antibiotics against drug-resistant clinical pathogens. J. Trop. Med. 2025, 9916282. [Google Scholar]

- Shahin, H.H. , Baroudi, M., Dabboussi, F., Ismail, B., Salma, R., Osman, M., El Omari, K. Synergistic Antibacterial Effects of Plant Extracts and Essential Oils Against Drug-Resistant Bacteria of Clinical Interest. Pathogens 2025, 14, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elaissi, A. , Moumni, S., Derbali, Y., Khouja, M., Abid, N., Jlasssi, I., Khaloud, M.A., Frederic, L., Khouja, M.L. Chemical compositions of Eucalyptus sp. essential oils and the evaluation of their combinations as a promising treatment against ear bacterial infections. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2024, 24, 220. [Google Scholar]

- Nebié, B. , Dabire, C.M., Bonzi, S., Soma, D.D., Bationo, R.K., Sosso, S., Namountougou, M., Nebie, R.C.H., Somda, I., Pale, E., Dabire, R.K., Duez, P. Chemical constituents and pesticide efficacy of two essential oil combinations of Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf and Mentha piperita L. from western Burkina Faso. Mediterr. J. Chem. 2024, 14, 79–87. [Google Scholar]

- Nebié, B. , Dabiré, C.M., Bonzi, S., Bationo, R.K., Sosso, S., Nebi, R.C. Chemical composition and antifungal activity of the essential oil obtained by co-distillation of Cymbopogon citratus and Eucalyptus camaldulensis from Burkina Faso. J Pharmacogn Phytochem 2023, 12, 43–8. [Google Scholar]

- Danzi, D. , Thomas, M., Cremonesi, S., Sadeghian, F., Staniscia, G., Andreolli, M., Bovi, M., Polverari, A., Tosi, L., Bonaconsa, M., Lampis, S., Spinelli, F., Vandelle, E. Essential oil-based emulsions reduce bacterial canker on kiwifruit plants acting as antimicrobial and antivirulence agents against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Chem. biol. technol. agric. 2025, 12, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Nafis, A. , Kasrati, A., Jamali, C.A., Custódio, L., Vitalini, S., Iriti, M., Hassani, L. A comparative study of the in vitro antimicrobial and synergistic effect of essential oils from Laurus nobilis L. and Prunus armeniaca L. from Morocco with antimicrobial drugs: New approach for health promoting products. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 140. [Google Scholar]

- Kachkoul, R. , Benjelloun Touimi, G., Bennani, B., El Habbani, R., El Mouhri, G., Mohim, M., Houssaini T.S., Chebaibi, M., Koulou, A., Lahrichi, A. The synergistic effect of three essential oils against bacteria responsible for the development of Lithiasis infection: An optimization by the mixture design. Evid. Based Complement Alternat. Med. 2021, 1305264. [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylova, S. , Tsvetkova, A., Stamova, S., Ermenlieva, N., Tsankova, G., Georgieva, E., Peycheva, K.; Panayotova, V.; Voynikov, Y. Antibacterial effects of Bulgarian oregano and thyme essential oils alone and in combination with antibiotics against Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 843. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N. , Fatima, S., Sadiq, M.B. Innovative antifungal and food preservation potential of Eucalyptus citriodora essential oil in combination with modified potato Peel starch. Foods 2025, 14, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratini, F. , Pecorini, C., Resci, I., Copelotti, E., Nocera, F.P., Najar, B., Mancini, S. Evaluation of the synergistic antimicrobial activity of essential oils and cecropin a natural peptide on gram-negative bacteria. Animals 2025, 15, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aungtikun, J. , Soonwera, M., Sittichok, S. Insecticidal synergy of essential oils from Cymbopogon citratus (Stapf.), Myristica fragrans (Houtt.), and Illicium verum Hook. f. and their major active constituents. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2021, 164, 113386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejenaru, L.E. , Segneanu, A.E., Bejenaru, C., Biţă, A., Tuţulescu, F., Radu, A., Ciocîlteu, M.V.; Mogosanu, G.D. Seasonal variations in chemical composition and antibacterial and antioxidant activities of Rosmarinus officinalis L. essential oil from southwestern Romania. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, N. , Wang, J., Jia, Y., Duan, J., Wang, X., Li, J., Zhou, P., Xie, Y., Shi, H., Zhao, C., Zou, J., Guo, D., Shi, Y., Li, H., Wu, Z., Yang, M., Chang, X., Sun, J., Zhang, X. Optimization of the process of extracting essential oil of rosemary by hydro distillation with different auxiliary methods. LWT 2025, 215, 117266. [Google Scholar]

- Khodaei, N. , Houde, M., Bayen, S., Karboune, S. Exploring the synergistic effects of essential oil and plant extract combinations to extend the shelf life and the sensory acceptance of meat products: multi-antioxidant systems. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 679–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alami, A. , Ez zoubi, Y., Fadil, M., Annemer, S., Bassouya, M., Moustaid, W., Farah, A. Exploring ternary essential oil mixtures of Moroccan Artemisia species for larvicidal effectiveness against Culex pipiens mosquitoes: A mixture design approach. J. Parasitol. Res. 2025, 2025, 2379638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meradsi, F. , Lekbir, A., Bensaci, O. A., Tifferent, A., Abbasi, A., Djemoui, A., Rebouh, N.Y., Hashem, A., Avila-Quezada, G.D., Almutairi, K.F., Abd Allah, E.F. Detection of the early sensitive stage and natural resistance of broad bean (Vicia faba L.) against black bean and cowpea aphids. Insects 2025, 16, 817. [Google Scholar]

- Boukhris-Bouhachem, S. , Souissi, R., Turpeau, E., Rouzé-Jouan, J., Fahem, M., Brahim, N.B., Hulle, M. Aphid (Hemiptera: Aphidoidea) diversity in Tunisia in relation to seed potato production. In Annales de la Société Entomologique de France; Taylor & Francis Group, 2007; p. 311–318.

- Baş, F.H. , Özgökçe, M.S. Life tables and predation rates of Hippodamia variegata (Goeze) and Adalia fasciatopunctata revelieri (Mulstant) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) on Aphis fabae (Scopoli) (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Phytoparasitica 2025, 53, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaili, S.J. , Kabiraj, U.K., Mahedi, M. Fungal biocontrol in agriculture: A sustainable alternative to chemical pesticides–A comprehensive review. World J. Adv. Res. Rev. 2025, 26, 2305–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.A. , Mohamed, A.M., Sharaky, M., Diab, Y.M., Abdelbaky, A.S. Evaluation of antioxidant, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic effects of Cymbopogon citratus essential oil. Fayoum j. Agr. res. dev. 2025, 39, 372–382. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, D.L.D. , Bandeira, M.A.M., Soares, I.L., Duque, B.R., Costa, M.D.R.D., Viana, G.D.A., Magalhães, E.P., de Menezes R.R.P.P.B., Sampaio, T.L., Marinho, M.M., Martins, A.M.C. Cymbopogon citratus essential oil protects tubular renal cells against Ischemia/Reoxygenation injury-involvement Nrf2/Keap1 pathway. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2025, 68, e25240758. [Google Scholar]

- Khasanah, L.U. , Ariviani, S., Purwanto, E., Praseptiangga, D. Chemical composition and citral content of essential oil of lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus (DC.) Stapf) leaf waste prepared with various production methods. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 19, 101570. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, G. , Schweitzer, B., Steinbach, A.S., Hodován, Á.S., Horváth, M., Bakó, E., Mayer, A.; Pál, S. The therapeutic potential of west indian Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus) essential oil-based ointment in the treatment of pitted Keratolysis. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margarita, V. , Nguyen, T.H.T., Petretto, G.L., Congiargiu, A., Ligas, A., Diaz, N., Ton Nu, P.A., Pintore, G., Rappelli, P. Effect of essential oils from Cymbopogon citratus, Citrus grandis, and Mentha arvensis on Trichomonas vaginalis and role of its symbionts Mycoplasma hominis and Ca. Mycoplasma girerdii. Front. parasitol. 2025, 4, 1610965. [Google Scholar]

- Ammar, H. , M’Rabet, Y., Hassan, S., Chahine, M., de Haro-Marti, M., Soufan, W., Andres, S., López, S., Hosni, K. Chemodiversity and antimicrobial activities of Eucalyptus spp. essential oils. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2383318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Pimienta, J. , Espino, J., Martillanes, S., Delgado-Adámez, J. Essential oils as nature’s dual powerhouses for agroindustry and medicine: Volatile composition and bioactivities—Antioxidant, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic. Separations 2025, 12, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedhri, S. , Polito, F., Caputo, L., Khammassi, M., Dhaouadi, F., Amri, I., Hamrouni, L., Mabrouk, Y., Fratianni, F., Nazzaro, F., De Feo, V. Antimicrobial, herbicidal and pesticidal potential of Tunisian Eucalyptus species: Chemoprofiling and biological evaluation. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M. , Mazzafera, P. Essential oils from Eucalyptus species: a review of their activities, applications, and the Brazilian market. Acta Bot. Bras. 2025, 39, e20240111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, S. , Nalbantova, V., Benbassat, N., Dzhoglova, V., Dzhakova, Z., Koleva, N., Vasilev, V., Grekova-Kafalova, D., Ivanov, K. Comparison between the chemical composition of essential oils isolated from biocultivated Salvia rosmarinus Spenn. (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) and some commercial products. Pharmacia 2025, 72, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Jaïdi, A. , Boukhris, M., Aydın, B., Aytar, E. C., Ayouni, W., Salem, R. B., & Rigane, G. Chemical Composition, antioxidant activities, and molecular docking analysis of essential oils and hydrolates from two varieties of Salvia rosmarinus (laxiflorus and troglodytorum) growing in southern Tunisia. Chem. Biodiversity. 2025, e01266. [Google Scholar]

- Nasraoui, S. , Mechergui, K., Chargui, A., Kammoun, M., Ameur, M., Melki, M., Fauconnier, M.L., Ammari, Y. Comparative analysis of essential oils, phenolic compounds, and bioactivity in wild and cultivated Salvia rosmarinus, Thymbra capitata, and Artemisia herba-alba under semi-arid Tunisian conditions. Chemoecology 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.F. , Sofi, A.B., Ganaie, K.A., Shah, S.Q., Nazir, R., Shakir, P.S., Qazi, P.H. Chemical composition and antimicrobial potential of essential oils from morphologically distinct Salvia rosmarinus (Spenn.) cultivars from Kashmir, India. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1579383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. , Wang, Y.M., Yu, G.F., Chen, Z.H., Ma, M.M., Zhang, K.Y., Zhang, Y.F., Che, Z.P., Hu, Z.J., Chen, G.Q., Liu, S.M., Deng, S.Z. Exploitation of Rosmarinus officinalis ct. verbenone essential oil as potential and eco-friendly attractant for Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel). Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2025, 300, 118452. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, T. , Cerasa, G., Marotta, I., Conte, M., Orlando, S., Salamone, A., Mammano, M.M., Greco C., Tsolakis, H. Toxicity of essential oils of Origanum vulgare, Salvia rosmarinus, and Salvia officinalis Against Aculops lycopersici. Plants 2025, 14, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toso, F. , Buldain, D., Retta, D., Di Leo Lira, P., Marchetti, M. L., & Mestorino, N. Antimicrobial activity of Origanum vulgare L. And Salvia rosmarinus Spenn (syn Rosmarinus officinalis L.) essential oil combinations against Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium isolated from poultry. Processes 2025, 13, 2856. [Google Scholar]

- Ait Melloul, A. , Abbad, I. , Barakate, M. Efficacy of Thymus vulgaris, Syzygium aromaticum, and Marrubium vulgare essential oils against multi-drug resistant uropathogenic bacteria. In. E3S Web of Conferences 2025, 632, 01001. [Google Scholar]

- Alibeigi, Z. , Rakhshandehroo, E., Saharkhiz, M. J., Alavi, A. M. The acaricidal and repellent activity of the essential and nano essential oil of Thymus vulgaris against the larval and engorged adult stages of the brown dog tick, Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acari: Ixodidae). BMC Vet. Res. 2025, 21, 135. [Google Scholar]

- Veshareh, A.A. , Mohammadi, P., Ahmadi, S. Hydrogels containing Thymus vulgaris essential oil as a novel approach for cleaning monument glazed tiles. Herit. Sci. 2025, 13, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galgano, M. , Pellegrini, F., Mrenoshki, D., Addante, L., Sposato, A., Del Sambro, L., Capozzi, L., Catalano, E., Solito, M., D’Amico, F., Messina, D., Parisi, A., Pratelli, A., Capozza, P. Inhibition of biofilm production and determination of in vitro time-kill Thymus vulgaris L. essential oil (TEO) for the control of Mastitis in small ruminants. Pathogens 2025, 14, 412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Yaovi, A.B. , Das, A., Behera, R.N., Azokpota, P., Farougou, S., Baba-Moussa, L., Michels, F., Fauconnier M.L., Ambatipudi, K., Sessou, P. Antibacterial activity of Cinnamomum verum and Thymus vulgaris essential oils on multidrug-resistant zoonotic bacteria isolated from dogs in southern Benin. Access Microbiol. 2025, 7, 000975–v3. [Google Scholar]

- Jilani, S. , Ferjeni, M., Al-Shammery, K., Rashid Mohammed AlTamimi, H., Besbes, M., Ahmed Lotfi, S., Farouk, A., Ben Selma, W. The synergistic effect of Thymus vulgaris essential oil and carvacrol with imipenem against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: In vitro, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2025, 16, 1582102. [Google Scholar]

- Capdevila, S. , Grau, D., Cristóbal, R., Moré, E., & De las Heras, X. Chemical composition of wild populations of Thymus vulgaris and Satureja montana in central Catalonia, Spain. JSFA reports 2025, 5, 234–246. [Google Scholar]

- Taibi, M. , Elbouzidi, A., Bentouhami, N.E., Haddou, M., Baraich, A., Hammouti, Y., Belbachir, Y., Bellaouchi, R., Mothana, R.A., Hawwal M.F., Asehraou, A., Karboune, S., Addi, M., El Guerrouj, B., Chaabane, K., Chaabane, K. Evaluation of the dermatoprotective properties of Clinopodium nepeta and Thymus vulgaris Essential Oils: Phytochemical analysis, anti-elastase, anti-tyrosinase, photoprotective activities, and antimicrobial potential against dermatopathogenic strains. Ski. Res. Technol. 2025, 31, e70191. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Velandia, J.E. , Gallego-Villada, L.A., Mäki-Arvela, P., Sidorenko, A., Murzin, D.Y. Upgrading biomass to high-added value chemicals: Synthesis of monoterpenes-based compounds using catalytic green chemical pathways. Catal. Rev. 2025, 67, 371–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sell, C. Chemistry of essential oils. In Handbook of essential oils; CRC Press, 2020, pp. 161–189.

- Sadgrove, N.J. , Padilla-González, G.F., Phumthum, M. Fundamental chemistry of essential oils and volatile organic compounds, methods of analysis and authentication. Plants 2022, 11, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, E.P. , Souza, E.J.D., Pail, G.L., Siebeneichler, T.J., Fonseca, L.M., Rombaldi, C.V., Zavareze, E.R., Dias, A.R.G. Sweet orange and sour orange essential oils: A review of extraction methods, chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities, and applications in innovative food technologies. Food Biophys. 2025, 20, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Mugao, L. Factors influencing yield, chemical composition and efficacy of essential oils. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. Growth Eval 2024, 5, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedayati, S. , Tarahi, M., Madani, A., Mazloomi, S.M., Hashempur, M.H. Towards a greener future: Sustainable innovations in the extraction of lavender (Lavandula spp.) essential oil. Foods 2025, 14, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmohsen, U.R. , Elmaidomy, A.H. Exploring the therapeutic potential of essential oils: A review of composition and influencing factors. Front. Nat. Prod. 2025, 4, 1490511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, H., Joshi, P. Conventional techniques for extracting essential Oil: Steam distillation and hydrodistillation. In Essential oil extraction from food by-products; Humana: New York, NY, 2025; pp. 21–41.

- Akdağ, A. , Öztürk, E. Distillation methods of essential oils. S.U.F.E.F.D. 2019, 45, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rani, N. , Kumar, V., Chauhan, A. Exploring essential oils: Extraction, biological roles, and food applications. J. Food Qual. 2025, 2025, 9985753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souiy, Z. Essential oil extraction process. In Essential oils-recent advances, new perspectives and applications; IntechOpen, 2023.

- Fatima, A. , Ayub, M.A., Choobkar, N., Zubair, M., Thomspon, K.D., Hussain, A. The effect of different extraction techniques on the bioactive characteristics of dill (Anethum graveolens) essential oil. Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakab, E. , Blazsó, M., Barta-Rajnai, E., Babinszki, B., Sebestyén, Z., Czégény, Z., Nicol, J.; Clayton, P., McAdam, K., Liu, C. Thermo-oxidative decomposition of lime, bergamot and cardamom essential oils. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2018, 134, 552–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltanbeigi, E. , Maral, H. Volatile oil content and composition in fresh and dried Lavandula species: The impact of distillation time. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 2025, 123, 105066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y. , Zhang, L., Wu, W., Xie, J., Gao, B., Xiao, Y., & Zhu, D. Sustainable and green extraction of citrus peel essential oil using intermittent solvent-free microwave technology. B.I.O.B. 2025, 12, 48. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, R.N. , Soares, R.D.P., Cassel, E. Fractionation process of essential oils by batch distillation. Braz. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 35, 1129–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, M.H.B. , Ahmed, M.M., Mia, M.S., Islam, S., Zzaman, W. Essential oils: Advances in extraction techniques, chemical composition, bioactivities, and emerging applications. Food Chem. Adv. 2025, 8, 101048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lainez-Cerón, E. , Jiménez-Munguía, M.T., López-Malo, A., Ramírez-Corona, N. Effect of process variables on heating profiles and extraction mechanisms during hydrodistillation of Eucalyptus essential oil. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedhri, S. , Khammassi, M., Boukhris, B.S., Pieracci, Y., Flamini, G., Gargouri, S., Amri, I., Hamrouni, L. Tunisian Eucalyptus essential oils: exploring their potential for biological applications. Plant Biosyst. 2024, 158, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedhri, S. , Khammassi, M., Boukhris, B.S., Pieracci, Y., Mabrouk, Y., Seçer, E., Amri, I., Flamini, G., Hamrouni, L. Metabolite profiling of four Tunisian Eucalyptus essential oils and assessment of their insecticidal and antifungal activities. Heliyon 2023, 9, e22713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaled-Gasmi, W. , Hamouda, A.B., Chaieb, I., Souissi, R., Ascrizzi, R., Flamini, G., Boukhris, B.S. Natural repellents based on three botanical species essential oils as an eco-friendly approach against aphids. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 141, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, A.V. , Pinheiro, P.F., Rondelli, V.M., de QUEIROZ, V.T., Tuler, A.C., Brito, K.B., Stinguel P., Pratissoli, D. Cymbopogon citratus (poaceae) essential oil on frankliniella schultzei (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) and Myzus persicae (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Biosci. J. 2013, 29, 1840–1847. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. , Liu, R., He, J., Ma, Z., Zhang, X. Chemical compositions of Ligusticum chuanxiong oil and lemongrass oil and their joint action against Aphis citricola Van Der Goot (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Molecules 2016, 21, 1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sjam, S. , Dewi, V.S., Pujiati, W. Mortality and repellency of aphids (Aphis gossypii G) to orange peel extract (Citrus sinensis L.) and lemongrass emulsion oil (Cymbopogon citratus). In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, IOP Publishing, 2025; p. 012029.

- Jan, A. , Ali, T., Chirag, S., Ahmed, S., Ali, M., Wali, S., Basit, A., Ibrahim, M., Ullah, K. Eco-friendly management of insect pests and plant diseases using botanical extracts. G.R.J.N.S.T. 2025.

- Ouknin, M. , Alahyane, H., Ait Aabd, N., Elgadi, S., Lghazi, Y., Majidi, L. Comparative analysis of five Moroccan thyme species: Insights into chemical composition, antioxidant potential, anti-enzymatic properties, and insecticidal effects. Plants 2025, 14, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas, J.L. , López Santos-Olmo, M., Sagarduy-Cabrera, A., Marcos-García, M.Á. Evaluation of selected plant essential oils for aphid pest control in integrated pest management. Insects 2025, 16, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celaya, L.S. , Le Vraux, M.A., Heit, C.I., Viturro, C.I., Martina, P.F. Phytochemical and biological profile of essential oils of Elionurus muticus (Spreng.) growing in Northeastern Argentina. Chem. Biodiversity 2023, 20, e202201105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bora, D. , Agrahari, J., Phukan, A., Kakoti, B., Chhetry, S., Puzari, K., Saikia, I., Bardhan, S., Borah, H. Synergistic action of essential oil of Ageratum conyzoides, Cymbopogon citratus, Eucalyptus globulus, and synthetic insecticides against the mosquito vector, Aedes albopictus Skuse (Diptera: Culicidae). J Basic Appl Zool. 2025, 86, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Galeano, L.J.N. , Prieto-Rodríguez, J. A., Patiño-Ladino, O.J. Synergistic insecticidal activity of plant volatile compounds: Impact on neurotransmission and detoxification enzymes in Sitophilus zeamais. Insects 2025, 16, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Et-Tazy, L. , Lamiri, A., Krimi Bencheqroun, S., Errati, H., Hashem, A., Avila-Quezada, G. D., Abd-Allah E.F., Satrani, B., Essahli, M., Satia, L. Exploring synergistic insecticidal effects of binary mixtures of major compounds from six essential oils against Callosobruchus maculatus. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15180. [Google Scholar]

- Afrazeh, Z. , Sendi, J.J. Eco-friendly control of Helicoverpa armigera using synergistic mixtures of thymol and eucalyptol. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 26974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J. , Tak, J. H. Utilization and validation of the polynomial models to predict insecticidal synergy in the essential oils of Thymus vulgaris L. and Thymus zygis L. against Musca domestica L. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2025, 233, 121405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, S. , Abbate, L., Arif, M.A., Peri, E. Insecticidal activity of single essential oil constituents against two stored-products insect pests. Int. J. Trop. Insect Sci. 2025, 45, 185–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamunkar, R. , Sinha, D., Shrivas, K., Patle, T. K., Kumar, A., Tandey, K., Singh, T. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and RP-HPLC quantification of β-caryophyllene in plant essential oils: Separation efficiency and insecticidal activity. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1335, 141882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lhaosudto, S. , Sathantriphop, S., Kongmee, M., Karpkird, T., Leepasert, T., Ngoen-Klan, R., Chareonviriyaphap, T. Comparative behavioral responses of β-caryophyllene against Anopheles mosquito species, potential vectors of malaria in Thailand. J. Am. Mosq. Control. Assoc. 2025, 41, 156–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.S. , Feng, Y., Wang, Y., Li, J., Zou, K., Liu, H., Hu Y., Xue, Y., Yang, L., Du, S., Wu, Y. α-Pinene, caryophyllene and β-myrcene from Peucedanum terebinthaceum essential oil: Insecticidal and repellent effects on three stored-product insects. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2020, 14, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chohan, T.A. , Chohan, T.A., Mumtaz, M.Z., Alam, M.W., Naseer, I., Riaz, A., Tayyeba, N., Areeba, I., Ali, N., Dur, E., Mubashir, H., Ali, H.M. Insecticidal Potential of α-Pinene and β-caryophyllene against Myzus persicae and their impacts on gene expression. Phyton 2023, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Usman, L.A. , Akpan, E.D., Ojumoola, O.A., Ismaeel, R.O., Simbiat, A.B. Phytochemical profile and insecticidal potential of leaf essential oil of Psidium guajava growing in north central Nigeria. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 2025, 480–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadgrove, N.J. , Padilla-González, G.F., Phumthum, M. Fundamental chemistry of essential oils and volatile organic compounds, methods of analysis and authentication. Plants 2022, 11, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Q.Y. A method for evaluating the toxicity interaction of binary mixtures. MethodsX 2020, 7, 101029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyanasundaram, M. , Das, P.K. Larvicidal and synergistic activity of plant extracts for mosquito control. Indian J. Med. Res. 1985, 82, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

| Yield (%) | CPM-EOs | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Binary | Ternary | |||||||||||||||||||

| No | Compounds | RI* | Formula | CC | EC | EL | SR | TV |

CC + EC |

CC + EL |

CC + SR |

CC + TV |

EC + EL |

EC + SR |

EC + TV |

EL + SR |

EL + TV |

SR + TV |

CC + TV + EC |

CC + TV + EL |

CC + TV + SR |

| 1 | α-Pinene | 7.796 | C10H16 | - | 24.38 | 24.18 | 9.06 | 1.11 | 0.8 | 16.9 | 3.5 | 0.66 | 23.39 | 9 | 1.88 | 13.77 | 11.97 | 5.09 | 0.77 | 0.71 | 1.57 |

| 2 | Camphene | 8.241 | C10H16 | - | - | - | 4.85 | - | - | - | 2.28 | - | - | 2.95 | - | 4.54 | - | 3.09 | - | - | 0.82 |

| 3 | β-Pinene | 9.095 | C10H16 | - | 1.21 | - | 6.64 | - | - | - | 2.9 | - | - | 2.78 | - | 2.98 | 0.39 | 3.37 | - | - | 0.98 |

| 4 | β-Myrcene | 9.582 | C10H16 | 9.59 | - | - | 2.39 | 1.25 | 5.91 | - | 2.93 | 2.34 | - | 0.9 | 1.09 | 1.51 | 0.75 | 2.23 | 1.03 | 2.19 | 1.7 |

| 5 | 3-Carene | 10.102 | C10H16 | - | 0.45 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 6 | α-Terpinene | 10.462 | C10H16 | - | - | - | - | 0.97 | - | - | - | 0.53 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.79 | - | 0.54 | - |

| 7 | p-Cymene | 10.847 | C10H14 | - | - | - | - | 11.01 | 19.14 | - | - | 2.92 | - | - | 20.52 | - | - | - | 16.81 | 3.68 | - |

| 8 | Eucalyptol | 10.856 | C10H18O | - | 66.51 | 56.99 | 46.56 | - | - | 73.62 | 26.13 | - | 71.27 | 64.35 | - | 49.62 | 35.09 | 29.02 | - | - | 10.67 |

| 9 | Trans-3-Caren-2-ol | 11.755 | C10H16O | - | - | - | - | - | 4.07 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 10 | γ-Terpinene | 11.825 | C10H16 | - | - | - | - | 7.73 | - | - | - | 3.57 | - | - | 10.11 | - | 7.96 | 6.01 | 3.38 | 3.85 | 4.94 |

| 11 | Cis-Sabinene hydrate | 12.610 | C10H18O | - | - | 12.39 | 1.25 | - | - | - | 0.52 | - | - | - | - | 9.42 | 0.78 | 1.18 | - | - | - |

| 12 | D-Verbenone | 13.115 | C10H14O | - | - | - | - | - | 0.73 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 13 | Linalool | 13.642 | C10H18O | - | - | - | - | 2.71 | 0.92 | - | 1.31 | 2.01 | - | - | 1.27 | - | - | - | 0.57 | 1.84 | 1.22 |

| 14 | Camphor | 14.587 | C10H16O | - | - | - | 7.44 | - | - | - | 9.39 | - | - | 4.04 | - | 6.28 | - | 5.99 | - | - | 3.99 |

| 15 | Cis-p-mentha-1(7),8-dien-2-ol | 14.636 | C10H16O | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.83 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 16 | Isopinocarveol | 15.142 | C10H16O | - | 0.72 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.06 | - | - | - | - |

| 17 | β-Citronellene | 15.245 | C10H18 | 0.91 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 18 | 1,6-Octadiene, 3,7-dimethyl- | 15.693 | C10H18 | 2.8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 19 | Isoneral | 15.859 | C10H16O | - | - | - | - | - | 2.68 | - | - | 2.45 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.45 | - |

| 20 | endo-Borneol | 15.972 | C10H18O | - | - | - | 11.35 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2.41 | - | 4.93 | - | - | 10.13 |

| 21 | Terpinen-4-ol | 16.045 | C10H18O | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.52 | - | - | - | 0.72 | - | - |

| 22 | Isoborneol | 16.084 | C10H18O | - | - | - | - | 3.01 | - | - | 5.02 | - | - | 2.79 | - | - | 1.46 | 2.82 | - | - | - |

| 23 | Isobornyl formate | 16.621 | C11H18O2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 3.23 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 24 | α-Terpineol | 16.853 | C10H18O | - | - | 2.66 | - | - | 2.57 | 0.59 | - | - | 1.9 | 3.9 | 3.81 | 3.59 | 2.29 | - | 1.49 | - | - |

| 25 | Neral | 17.741 | C10H16O | 29.14 | - | - | - | - | 17.23 | 2.69 | 9.8 | 12.34 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 6.43 | 10.7 | 7.68 |

| 26 | Bornyl acetate | 18.429 | C12H20O2 | - | - | - | 2.12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.88 | - | 0.68 | - | 1.9 | - | ||

| 27 | Citral | 18.699 | C10H16O | 53.11 | - | - | - | - | 33.2 | 5.11 | 21.45 | 24.12 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 16.97 | 20.9 | 15.95 |

| 28 | α-Terpinyl acetate | 20.403 | C12H20O2 | - | 3.56 | 2.41 | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | 1.65 | 1.63 | - | 1.36 | 1.36 | - | - | - | - |

| 29 | Ylangene | 20.838 | C15H24 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.33 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 30 | Nerolidyl acetate | 21.165 | C17H28O2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.99 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 31 | Geranyl acetate | 21.213 | C12H20O2 | 4.43 | - | - | - | - | 6.84 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 32 | Thymol | 21.69 | C10H14O | - | - | - | - | 70.84 | - | - | - | 45.78 | - | - | 55.69 | - | 35.77 | 33.56 | 50.46 | 49.67 | 37.64 |

| 33 | Caryophyllene | 22.122 | C15H24 | - | - | - | 8.34 | - | - | - | 4.35 | - | - | 2.88 | - | 3.17 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 34 | Aromandendrene | 22.665 | C15H24 | - | - | - | - | - | 1.4 | - | - | - | - | 0.85 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 35 | cis-α-Bisabolene | 23.041 | C15H24 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.75 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 36 | β-Longipinene | 23.121 | C15H24 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.63 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 37 | 7-epi-cis-sesquisabinene hydrate | 23.631 | C15H26O | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.69 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 38 | Acorenone B | 24.174 | C15H24O | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.76 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.9 | 1.24 |

| 39 | Caryophyllene oxide | 26.789 | C15H24O | - | - | - | - | 1.36 | - | - | 2.42 | 1.5 | - | - | - | - | 1.1 | - | - | 1.5 | 1.46 |

| 40 | Globulol | 26.989 | C15H26O | - | - | - | - | - | 2.97 | - | - | - | - | - | 3.2 | - | - | - | 1.3 | - | - |

| 41 | (-)-Spathulenol | 27.064 | C15H24O | - | 3.09 | 0.37 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1.77 | 3.02 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Monoterpene hydrocarbons % | 13.3 | 26.04 | 24.78 | 22.92 | 22.07 | 25.85 | 16.9 | 11.6 | 10.02 | 23.39 | 15.63 | 33.6 | 22.8 | 21.07 | 20.58 | 21.99 | 10.97 | 10.01 | |||

| Oxygenated monoterpenes % | 86.68 | 70.79 | 74.45 | 68.72 | 76.56 | 68.24 | 83.01 | 76.85 | 86.7 | 74.82 | 77.59 | 63.12 | 73.36 | 77.81 | 79.4 | 76.64 | 85.56 | 87.28 | |||

| Sesquiterpene hydrocarbons % | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8.34 | 0 | 1.4 | 0 | 6.43 | 0 | 0 | 3.73 | 0 | 3.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Oxygenated sesquiterpenes % | 0 | 3.09 | 0.37 | 0 | 1.36 | 2.97 | 0 | 5.1 | 3.26 | 1.77 | 3.02 | 3.2 | 0 | 1.1 | 0 | 1.3 | 3.4 | 2.7 | |||

| Total identified % | 99.98 | 99.92 | 99.6 | 99.98 | 99.99 | 98.46 | 99.91 | 99.98 | 99.98 | 99.98 | 99.97 | 99.92 | 99.96 | 99.98 | 99.98 | 99.93 | 99.93 | 99.99 | |||

| EO Species/Combinations | LC50 (µL mL−1) | Intercept ± SE | Slope ± SE | χ2 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. citratus | 3.24 | 2.044 ± 0.463 | –0.631 ± 0.126 | 25.24 | 0.000001 |

| E. camaldulensis | 2.45 | 0.333 ± 0.229 | –0.136 ± 0.035 | 14.90 | 0.000114 |

| E. lehmannii | 2.90 | 0.580 ± 0.240 | –0.200 ± 0.041 | 24.32 | 0.000001 |

| S. rosmarinus | 4.41 | 1.122 ± 0.257 | –0.133 ± 0.034 | 15.24 | 0.000095 |

| T. vulgaris | 3.71 | 0.837 ± 0.250 | –0.226 ± 0.042 | 29.19 | <0.000001 |

| C. citratus + E. camaldulensis | 1.75 | 1.608 ± 0.468 | –0.917 ± 0.220 | 17.32 | 0.000032 |

| C. citratus + E. lehmannii | 2.35 | 2.307 ± 0.627 | –0.981 ± 0.240 | 16.64 | 0.000045 |

| C. citratus + S. rosmarinus | 2.38 | 1.494 ± 0.389 | –0.628 ± 0.131 | 23.01 | 0.000002 |

| C. citratus + T. vulgaris | 1.75 | 1.608 ± 0.468 | –0.917 ± 0.22 | 17.32 | 0.000032 |

| E. camaldulensis + E. lehmannii | 3.28 | 0.905 ± 0.263 | –0.276 ± 0.050 | 30.88 | <0.000001 |

| E. camaldulensis + S. rosmarinus | 2.87 | 1.243 ± 0.320 | –0.433 ± 0.082 | 28.09 | <0.000001 |

| E. camaldulensis + T. vulgaris | 1.39 | 1.352 ± 0.435 | –0.972 ± 0.242 | 16.12 | 0.000060 |

| E. lehmannii + S. rosmarinus | 2.82 | 0.777 ± 0.260 | –0.276 ± 0.052 | 28.61 | <0.000001 |

| E. lehmannii + T. vulgaris | 1.51 | 1.430 ± 0.443 | –0.945 ± 0.232 | 16.54 | 0.000048 |

| S. rosmarinus + T. vulgaris | 1.63 | 1.515 ± 0.454 | –0.927 ± 0.225 | 16.97 | 0.000038 |

| C. citratus + T. vulgaris + E. camaldulensis | - | - | - | - | - |

| C. citratus + T. vulgaris + E. lehmannii | - | - | - | - | - |

| C. citratus + T. vulgaris + S. rosmarinus | - | - | - | - | - |

| EO Species/Combination | LC50 (µL mL−1) | Expected LC50 (µL mL−1) | CTC | SF vs. A | SF vs. B | Effect Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. citratus + E. camaldulensis | 1.75 | 2.85 | 162.57 | 1.85 | 1.40 | Strong synergism |

| C. citratus + E. lehmannii | 2.35 | 3.07 | 130.64 | 1.38 | 1.23 | Strong synergism |

| C. citratus + S. rosmarinus | 2.38 | 3.83 | 160.71 | 1.36 | 1.85 | Strong synergism |

| C. citratus + T. vulgaris | 1.75 | 3.48 | 198.57 | 1.85 | 2.12 | Strong synergism |

| E. camaldulensis + E. lehmannii | 3.28 | 2.68 | 81.58 | 0.75 | 0.88 | Additive/Slight antagonism |

| E. camaldulensis + S. rosmarinus | 2.87 | 3.43 | 119.52 | 0.85 | 1.54 | Additive to moderate synergism |

| E. camaldulensis + T. vulgaris | 1.39 | 3.08 | 221.58 | 1.76 | 2.67 | Strong synergism |

| E. lehmannii + S. rosmarinus | 2.82 | 3.66 | 129.47 | 1.03 | 1.56 | Strong synergism |

| E. lehmannii + T. vulgaris | 1.51 | 3.31 | 218.81 | 1.92 | 2.46 | Strong synergism |

| S. rosmarinus + T. vulgaris | 1.63 | 4.06 | 249.08 | 2.71 | 2.27 | Strong synergism |

| C. citratus + T. vulgaris + E. camaldulensis | - | - | - | - | - | Strong synergism* |

| C. citratus + T. vulgaris + E. lehmannii | - | - | - | - | - | Strong synergism* |

| C. citratus + T. vulgaris + S. rosmarinus | - | - | - | - | - | Strong synergism* |

| Chemical Compound | r | p-value | Signifiance |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Pinene | 0.3942 | 0.105 | NS |

| Camphene | 0.3829 | 0.117 | NS |

| β-Pinene | 0.4248 | 0.079 | NS |

| β-Myrcene | 0.0837 | 0.741 | NS |

| 3-Carene | 0.0514 | 0.839 | NS |

| α-Terpinene | -0.0325 | 0.898 | NS |

| p-Cymene | -0.3312 | 0.179 | NS |

| Eucalyptol | 0.4664 | 0.051 | NS |

| Trans-3-Caren-2-ol | -0.1043 | 0.680 | NS |

| γ-Terpinene | -0.4387 | 0.069 | NS |

| Cis-Sabinene hydrate | 0.2340 | 0.350 | NS |

| D-Verbenone | -0.1043 | 0.680 | NS |

| Linalool | -0.2652 | 0.287 | NS |

| Camphor | 0.2265 | 0.366 | NS |

| Cis-p-mentha-1(7),8-dien-2-ol | -0.1845 | 0.464 | NS |

| Isopinocarveol | -0.1045 | 0.680 | NS |

| β-Citronellene | 0.2272 | 0.364 | NS |

| 1,6-Octadiene, 3,7-dimethyl- | 0.2272 | 0.364 | NS |

| Isoneral | -0.3578 | 0.145 | NS |

| endo-Borneol | 0.0884 | 0.727 | NS |

| Terpinen-4-ol | -0.3383 | 0.170 | NS |

| Isoborneol | 0.1521 | 0.547 | NS |

| Isobornyl formate | 0.0359 | 0.888 | NS |

| α-Terpineol | 0.0019 | 0.994 | NS |

| Neral | -0.1616 | 0.522 | NS |

| Bornyl acetate | 0.3534 | 0.150 | NS |

| Citral | -0.2101 | 0.403 | NS |

| α-Terpinyl acetate | 0.2596 | 0.298 | NS |

| Ylangene | 0.0359 | 0.888 | NS |

| Nerolidyl acetate | 0.0359 | 0.888 | NS |

| Geranyl acetate | 0.0370 | 0.884 | NS |

| Thymol | -0.5018 | 0.034 | * |

| Caryophyllene | 0.5267 | 0.025 | * |

| Aromandendrene | -0.0144 | 0.955 | NS |

| cis-α-Bisabolene | 0.0359 | 0.888 | NS |

| β-Longipinene | 0.1338 | 0.597 | NS |

| 7-epi-cis-Sesquisabinene hydrate | 0.0359 | 0.888 | NS |

| Acorenone B | -0.5119 | 0.030 | * |

| Caryophyllene oxide | -0.2312 | 0.356 | NS |

| Globulol | -0.3233 | 0.191 | NS |

| (-)-Spathulenol | 0.2442 | 0.329 | NS |

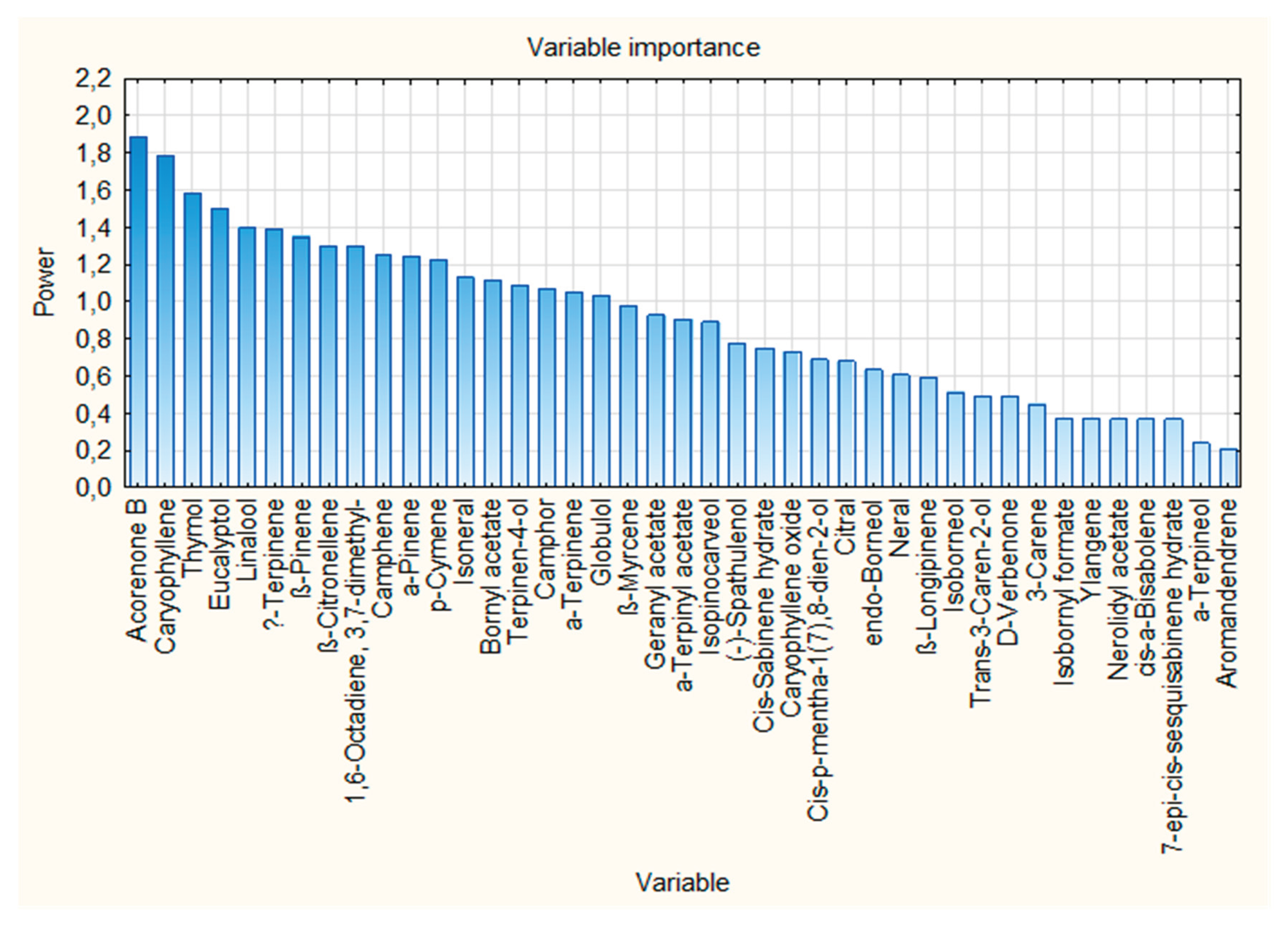

| Rank | Variable number | Chemical compound | VIP score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 38 | Acorenone B | 1.886 |

| 2 | 33 | Caryophyllene | 1.785 |

| 3 | 32 | Thymol | 1.580 |

| 4 | 8 | Eucalyptol | 1.498 |

| 5 | 13 | Linalool | 1.394 |

| 6 | 10 | γ-Terpinene | 1.388 |

| 7 | 3 | ß-Pinene | 1.345 |

| 9 | 17 | ß-Citronellene | 1.297 |

| 9 | 18 | 1,6-Octadiene, 3,7-dimethyl- | 1.297 |

| 10 | 2 | Camphene | 1.249 |

| 11 | 1 | α-Pinene | 1.243 |

| 12 | 7 | p-Cymene | 1.224 |

| 13 | 19 | Isoneral | 1.127 |

| 14 | 26 | Bornyl acetate | 1.114 |

| 15 | 21 | Terpinen-4-ol | 1.085 |

| 16 | 14 | Camphor | 1.069 |

| 17 | 6 | α-Terpinene | 1.045 |

| 18 | 40 | Globulol | 1.028 |

| Species | Used part | Harvesting period | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. citratus | Leaves | March-April/2025 |

Kairouan |

| E. camaldulensis | Leaves | Zarniza arboreta | |

| E. lehmannii | Leaves | Babbouche, Ain drahem | |

| S. rosmarinus | Aerial parts | Tborsok, Beja |

|

| T. vulgaris | Aerial parts |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).