1. Introduction

The geomagnetic field (GMF, with intensity value 25–65 μT at present) could protect organisms from solar wind and other cosmic radiations to keep the earth hospitable for living on as well as it is used for orientation and long-distance navigation in many species of animals (Johnsen & Lohmann,2008; Hong,1995). The GMF is closely linked to the growth and development of organisms (Able, 1994; Alerstam, 2003; Xu et al., 2013; Gao and Zhai, 2010; Wan et al., 2020), e.g., insects cultured in a near-zero magnetic space produce certain biological effects (Wan et al., 2014; Yan et al., 2021). Hypomagnetic fields (HMF) could affect microbial growth and antibiotic resistance, plant germination and growth, animal metabolism, development and cognitive behavior (Steinhilber et al., 2010; Xue et al., 2021; Grinberg and Vodeneev, 2025; Tian et al., 2022; Luo et al., 2022; Sizova et al., 2023). It was found that exposure to transient hypomagnetic fields resulted in increased sensitivity of first optic ganglion cells in Drosophila retina, delayed sperm aging, and stimulated sperm swimming (Creanga et al., 2002; Ogneva et al., 2020). Drosophila flies cultured in a hypomagnetic environment for more than 10 generations exhibited a loss of learning memory and recovered it after several generations of restoration to a geomagnetic environment (Zhang et al., 2004). Furthermore, hypomagnetic field significantly enhanced the phototaxis of the migratory insect, Sogatella furcifera, and affected the flight ability of S. furcifera in a sex-differentiated manner (Wan et al., 2016). The oriental armyworm Mythimna separata was easily disoriented in hypomagnetic fields, while its flight orientation in a deflected geomagnetic field varied regularly with the direction of the magnetic field (Xu et al., 2017). So far, HMF can lead to various biological effects including increased oxidative stress, abnormal neurological functions and developmental disorders (Zadeh-Haghighi and Simon, 2023; Wan et al., 2015; Marley et al., 2014; Sinčák and SedlakovaKadukova, 2023; Navarro et al., 2016).

Previously, we investigated the effects of magnetic fields on phototaxis of migratory insect, rice brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens, and found that the expression level of frataxin in N. lugens was downregulated by changed magnetic field. As a nuclear-encoded mitochondrial protein, frataxin is widespread in prokaryotes and eukaryotes with highly conserved structure. In eukaryotes, it primarily provides biological iron to mitochondria and is involved in the biosynthesis of intracellular iron-sulfur cluster proteins (Gibson et al., 1996; Campuzano et al., 1996; Koutnikova et al., 1997; Busi and Gomez-Casati, 2012). In yeast, frataxin interacts directly with the co-protein Isu in an iron-dependent manner and facilitates the transport of iron to Isu during the assembly of Fe-S clusters, and is therefore considered as a molecular chaperone of iron in mitochondria (Seguin et al., 2015). In Drosophila, the central role of frataxin is to maintain mitochondrial Fe-S cluster synthesis and iron metabolism homeostasis, and its absence leads to impaired energy metabolism, oxidative stress, and neurodegenerative phenotypes (Anderson et al., 2005;Runko et al., 2008;Calap-Quintana et al., 2018; Cabiscol et al., 2000; Llorens et al., 2007;Edenharter et al., 2017;Navarro et al., 2010). The knockdown or mutation of dFh leads to elevated ROS and triggers apoptosis, especially in neural and muscular tissues (Edenharter et al., 2018). dFh-deficient Drosophila exhibits dyskinesia, shortened lifespan, and neurodegeneration (Chen et al., 2016; Bekenstein et al., 2011; Apolloni et al., 2022). Complete deletion of dFh is lethal, suggesting the critical role of frataxin in the early development of Drosophila.

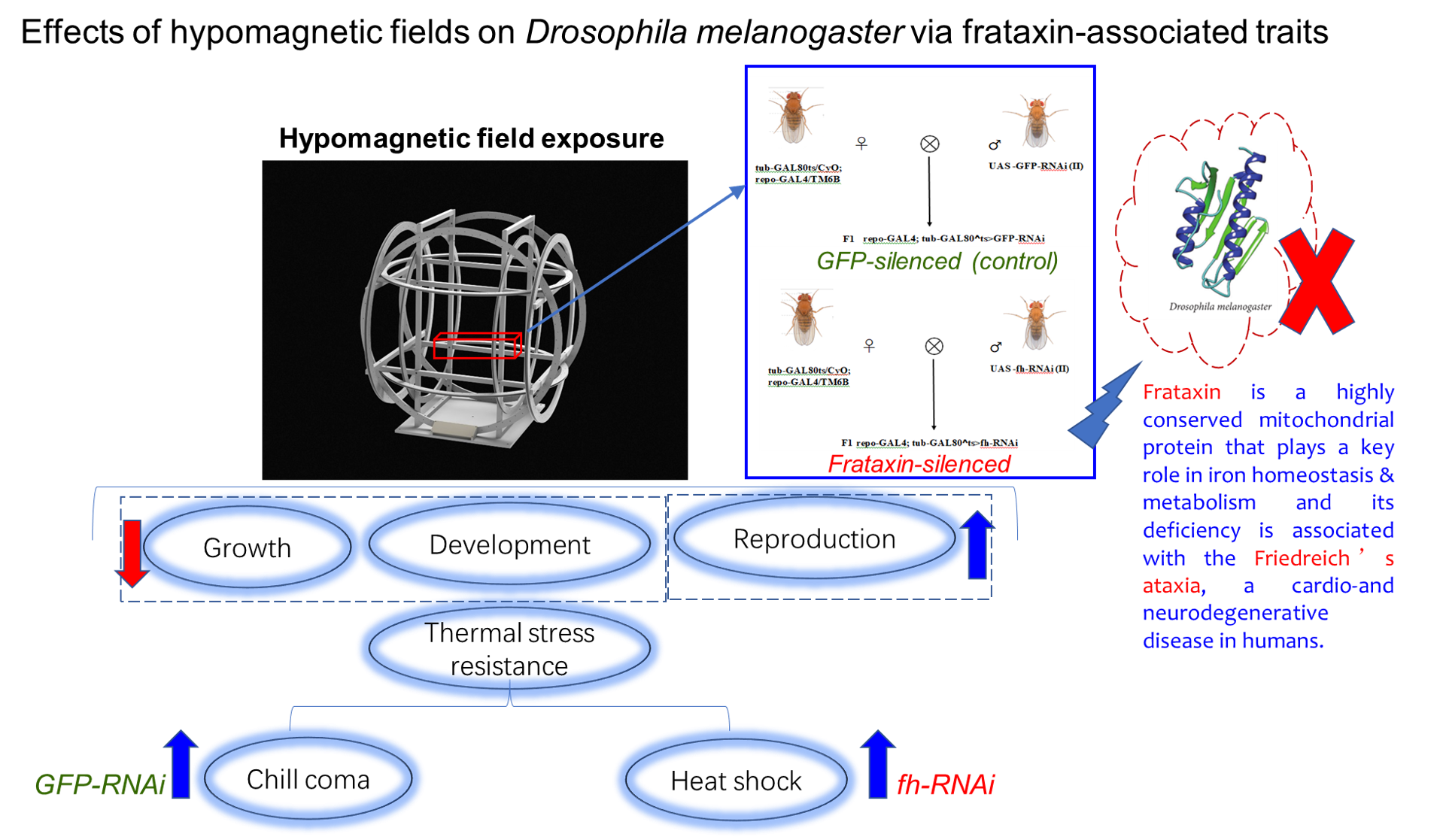

Based on the established roles of above-mentioned factors, a compelling rationale for coupling HMF with frataxin deficiency emerges. Frataxin is crucial for mitochondrial iron homeostasis and Fe-S cluster synthesis, and its deficiency leads to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neurodegeneration. Separately, HMF exposure is known to induce oxidative stress and cause neurological and developmental abnormalities. We therefore hypothesize that HMF acts as an environmental stressor that exacerbates the inherent metabolic vulnerabilities in frataxin-deficient flies. The mitochondrial dysfunction and heightened oxidative stress from dFh knockdown likely create a sensitized background, making the flies more susceptible to the additional metabolic perturbation imposed by HMF. In this study, the bio-effects of HMF on growth, development, reproduction and temperature stress resistance of frataxin-silenced Drosophila melanogaster were investigated. The GAL4/UAS system was employed to induce post-transcriptional silencing of Drosophila frataxin gene (fh) through transgenic double-stranded RNA interference (RNAi). It is supposed that exposure to HMF would affect multiple traits of Drosophila melanogaster via its effects on dFh knockdown.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Drosophila Lines, Cultivation and Diets

The Gal4-UAS system was utilized for tissue-specific gene expression. The tub-GAL80^ts/CyO;epo-GAL4/TM6B lines, obtained from China Agricultural University, were used to drive RNAi expression. The RNAi lines used in this work are as follows: UAS-fh RNAi (Bloomington Line Center, BDSC 24620), UAS-GFP RNAi (Tsing Hua Fly Center, TH00871.S). All lines were cultivated at 25±1°C, with relative humidity 60%±5% and 12: 12 h light: dark cycle, and the environmental conditions of the chambers was the same in the entire experiment. Standard regular diet (RD): agar 20 g/L sucrose 80 g/L, active dry yeast 5 g/L, calcium chloride dihydrate 1.6 g/L, ferrous sulfate heptahydrate 1.6 g/L, sodium potassium tartrate tetrahydrate 8 g/L, sodium chloride 0.5 g/L, manganese chloride tetrahydrate 0.5 g/L, and nipagin 5.3 mL/L (Villanueva et al., 2019).

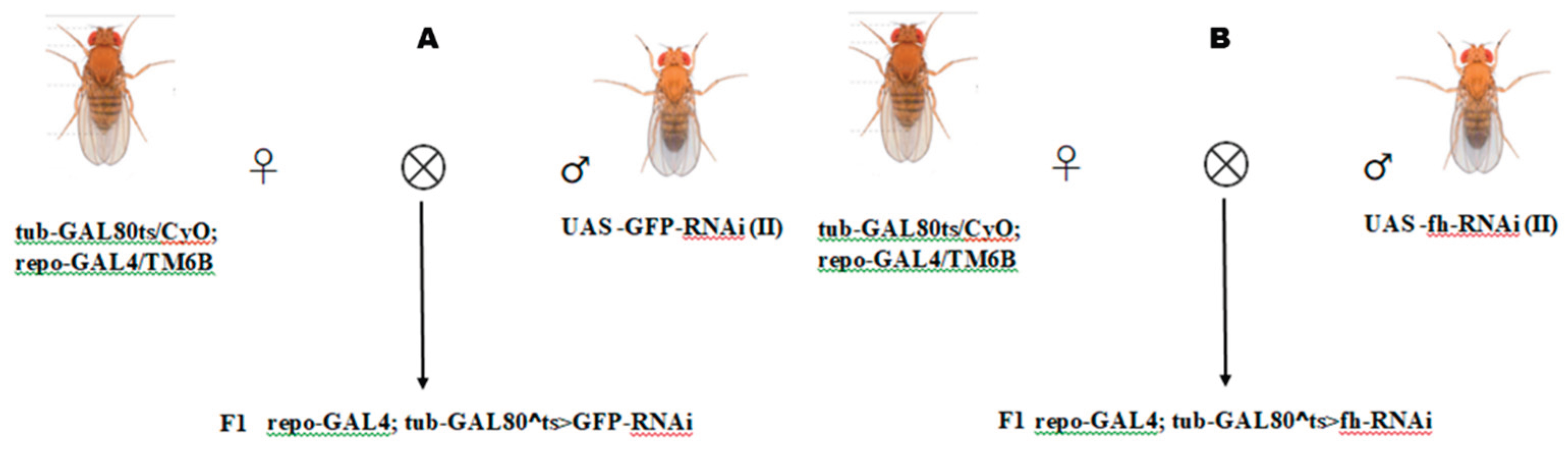

2.2. Construction of Frataxin-Silenced Drosophila Mutants Using RNAi

To achieve time-controlled silencing of frataxin (fh) (repo-GAL4; tub-GAL80^ts> fh-RNAi) in glial cells, we employed the GAL4/UAS system combined with tub-GAL80^ts. The genetic control was a strain silencing GFP in glial cells (repo-GAL4; tub-GAL80^ts>GFP-RNAi), treated under identical protocols (Zúñiga-Hernández et al.,2023; Bosch et al.,2016). First, hybridization experiments were conducted to generate F1 generations with silenced frataxin (repo-GAL4;tub-GAL80^ts>fh-RNAi, abbreviated as fh-RNAi) (

Figure 1A) and silenced GFP (repo-GAL4;tub-GAL80^ts>GFP-RNAi, abbreviated as GFP-RNAi) (

Figure 1B) in glial cells. For all crosses involving GAL80^ts, both parents and their developmental-stage offspring were reared at 18°C to suppress GAL4 activity. To induce target gene silencing, F1 offspring were transferred to 29°C post-eclosion. Upon reaching adulthood, F1 individuals were sorted for specific phenotypes to establish the silencing model.

2.3. Determination of Frataxin Silencing Efficiency and Quantitative PCR of CAT and HSP26 Genes

Total RNA was extracted from the heads of 3 to 8-day-old male Drosophila melanogaster according to Invitrogen’s Trizol reagent manual, and RNA quality was assessed by electrophoresis. RNA samples were treated with an RNase-free DNase set and purified using the NucleoSpin RNA Clean-up XS kit (Macherey-Nagel). Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa Bio Inc.) was used with 100 ng cDNA on an ABI 7500 PCR system (Applied Biosystems). The extracted RNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Based on the concentration measured by UV spectrophotometry, the volume corresponding to 1 µg RNA was calculated, and the appropriate volume of RNA solution was used for reverse transcription. The reverse-transcription product was then used to amplify intermediate fragments. Reverse-transcription procedures were performed strictly following the kit manual. A total of 1 µg RNA was used for reverse transcription to generate templates for quantitative PCR. To ensure accurate results, total RNA samples were treated with DNase I to remove residual genomic DNA.

Based on the CDS region of the obtained full-length gene cDNA sequence, qPCR primers were designed using NCBI software, with ribosomal protein 49 (Rp49) serving as the internal control gene. Real-time quantitative PCR was performed using an ABI kit to detect target gene expression in head of flies. Gene expression levels were normalized against the internal control using the quantitative Ct method for relative quantification, with results plotted as relative mRNA expression. Each experiment comprised three independent biological replicates. In addition, two genes of Cat (associated with ROS) and Hsp26 (associated with thermal stress) were chosen for a better understanding of the mechanism involved in the effects of HMF. The genes and primer pairs analyzed are as follows (

Table 1):

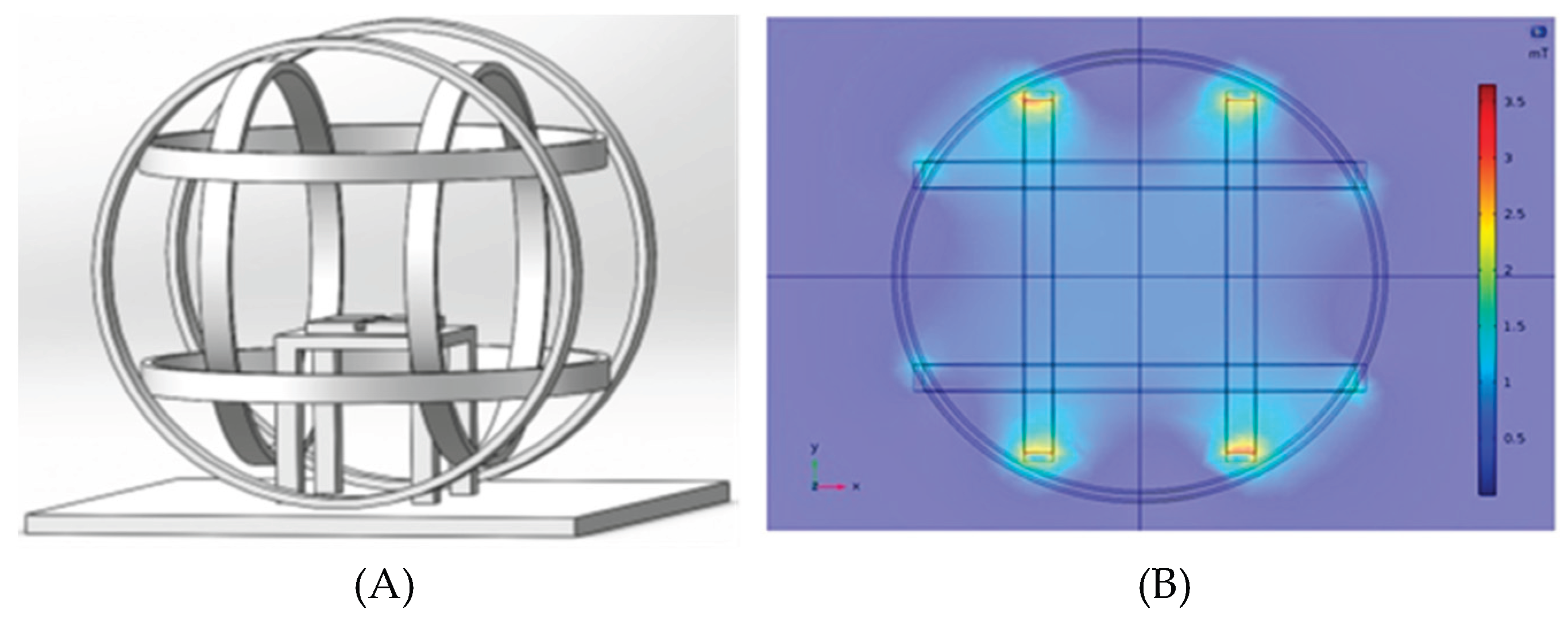

2.4. Magnetic Field Generation System and Insect Exposures

The experiment was conducted in a laboratory in Beijing (39°59′14″N, 116°19′21″E), where the local geomagnetic field (GMF) has an intensity of 52,487±841 nT, a declination of 5.30±0.59°, and an inclination of 56°29′±1.02°. To create a hypomagnetic field (HMF), we employed three sets of Helmholtz coils, each powered independently to generate an artificial field that precisely opposed and offset each vector component of the local GMF. This setup produced a spherical hypomagnetic environment of 300 × 300 × 300 mm³ with an average residual intensity <500 nT (

Figure 2). A fluxgate magnetometer (Honor Top model 191A, sensitivity ±1 nT) was used to calibrate and verify the HMF intensity twice daily, both before and after experimental sessions.

For the biological component of the study, we used 3- to 8-day-old Drosophila from two silenced strains: repo-GAL4;tub-GAL80^ts>GFP-RNAi and repo-GAL4;tub-GAL80^t s>fh-RNAi. The flies were housed in groups of 20 per tube, with three replicate groups per condition. Each experimental cycle consisted of a 72-hour exposure to either the HMF or the normal GMF, under a light-dark regimen of 36 hours of light followed by 36 hours of darkness.

2.5. Measurements of Developmental Duration, Adult Weight and Offspring Fecundity

Four experimental groups were established: GMF and HMF controls (repo-GAL4; tub-GAL80^ts > GFP-RNAi), and GMF and HMF experimental groups (repo-GAL4; tub-GAL80^ts > fh-RNAi). The Helmholtz coil system was used to generate HMF for the exposure groups, while the controls were maintained in a GMF within an artificial climate chamber. After three days of consecutive exposure, the parental flies were removed, and the eggs developed under their respective conditions until eclosion. The developmental duration of egg to adult and pupae were recorded every 8 hours, and the number of pupae and offspring flies per life cycle were counted for each vial. Furthermore, the body weight of six 3 to 8-day-old virgin flies from each group was measured, segregated by sex and line. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

2.6. Chill Coma and Heat Shock Recovery Assays

For chill coma recovery assay, twenty 3 to 7-day-old male flies from each line were transferred without anesthesia to empty vials and maintained at 4 °C for one hour. Following this, flies were returned to room temperature, and the recovery time–defined as the duration from coma to the ability to stand upright for more than two seconds–was recorded. For heat shock recovery assay, twenty 3 to 8-day-old male flies of each genotype were placed in individual glass tubes (24 × 15 mm). The tubes were submerged in a 39 °C water bath until all flies entered a heat-induced coma. They were then transferred to room temperature, and the recovery time was recorded using the same criterion.

2.7. Data Analysis

All data were analyzed using SPSS 20.0 (IBM Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). One-way ANOVA with Welch t-test for post-hoc comparisons was used to analyze the relative transcript levels of GFP and Drosophila frataxin in repo-GAL4;tub-GAL80^ts>GFP-RNAi and repo-GAL4;tub-GAL80^ts>fh-RNAi lines. A two-way ANOVA was used to assess the effect of magnetic field (HMF vs. GMF) on the following: egg-to-adult developmental duration, pupa developmental duration, and offspring fecundity. Sample sizes were as follows: for egg to adult developmental duration, 89 (HMF) and 32 (GMF) eggs for the GFP-RNAi control, and 101 (HMF) and 31 (GMF) for the frataxin-knockdown; for pupa developmental duration, 58 (HMF) and 32 (GMF) larvae for the control, and 92 (HMF) and 30 (GMF) for the frataxin-knockdown; for offspring fecundity, 15 pairs of female and male adults per genotype with magnetic field condition. Adult body weight was analyzed using a two-way ANOVA, with magnetic field and sex as factors (n=6 per sex per group). Recovery time from chill coma or heat shock was jointly analyzed using a three-way ANOVA with magnetic field (GMF vs HMF), genotype (GFP RNAi vs frataxin RNAi), and stress (heat vs chill) as factors. For all ANOVAs, when significant main effects or interactions were found (P<0.05), Tukey’s post-hoc test was further used for pairwise comparisons (P<0.05). Time to recovery was analyzed as a survival outcome (not yet recovered) using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared the four MF × genotype groups with a k-sample log-rank test; pairwise contrasts used log-rank with Holm adjustment. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test was used to analyze the relative transcript levels of Cat and Hsp26 in repo-GAL4;tub-GAL80^ts>fh-RNAi lines between HMF and GMF.

3. Results

3.1. GFP and Frataxin Silencing Efficiency Under GMF

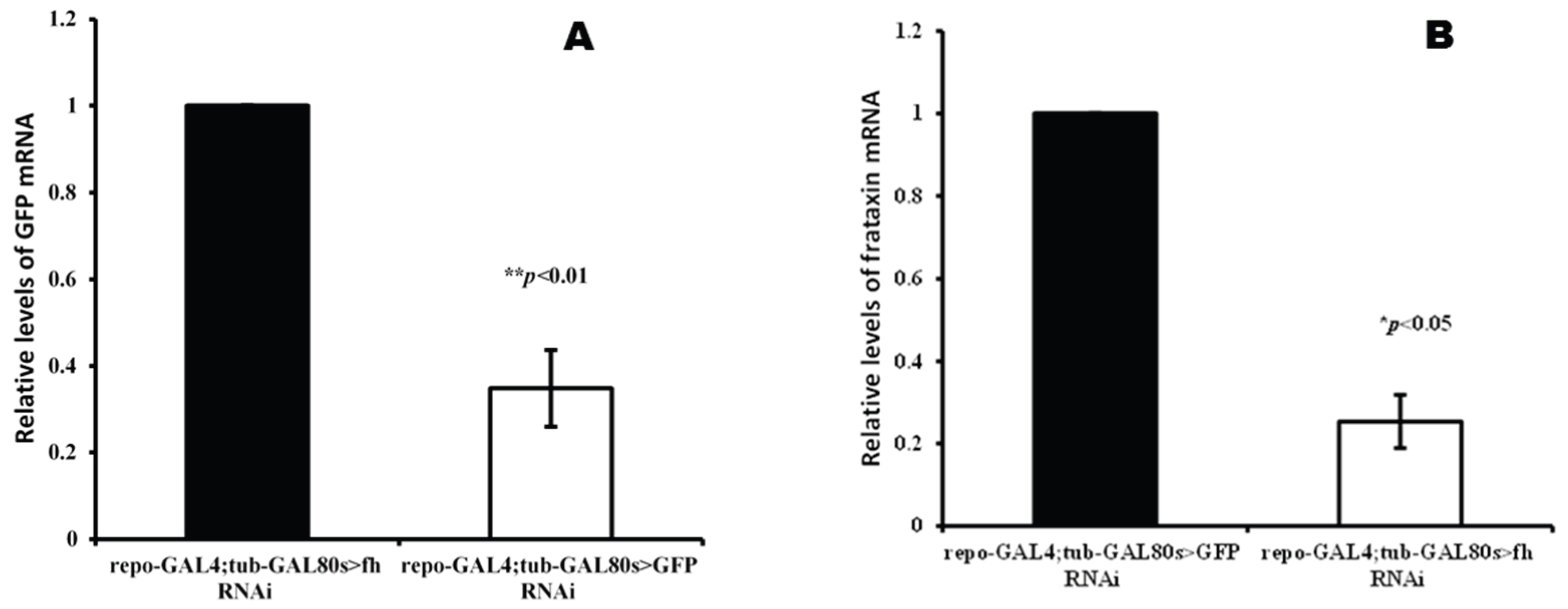

One-way ANOVA indicated that GFP and fh genes expression were significantly decreased in GFP-RNAi (F=133.31,

P<0.001) and fh-RNAi flies (F=54.12,

P=0.0018), respectively (

Figure 3). The target gene silencing efficiency showed that both lines of UAS-fh-RNAi and UAS-GFP-RNAi could achieve effective silencing without affecting non-target genes. The silencing efficiency of the UAS-GFP-RNAi line is 65% (

Figure 3A) and the UAS-fh-RNAi line is approximately 75% (

Figure 3B).

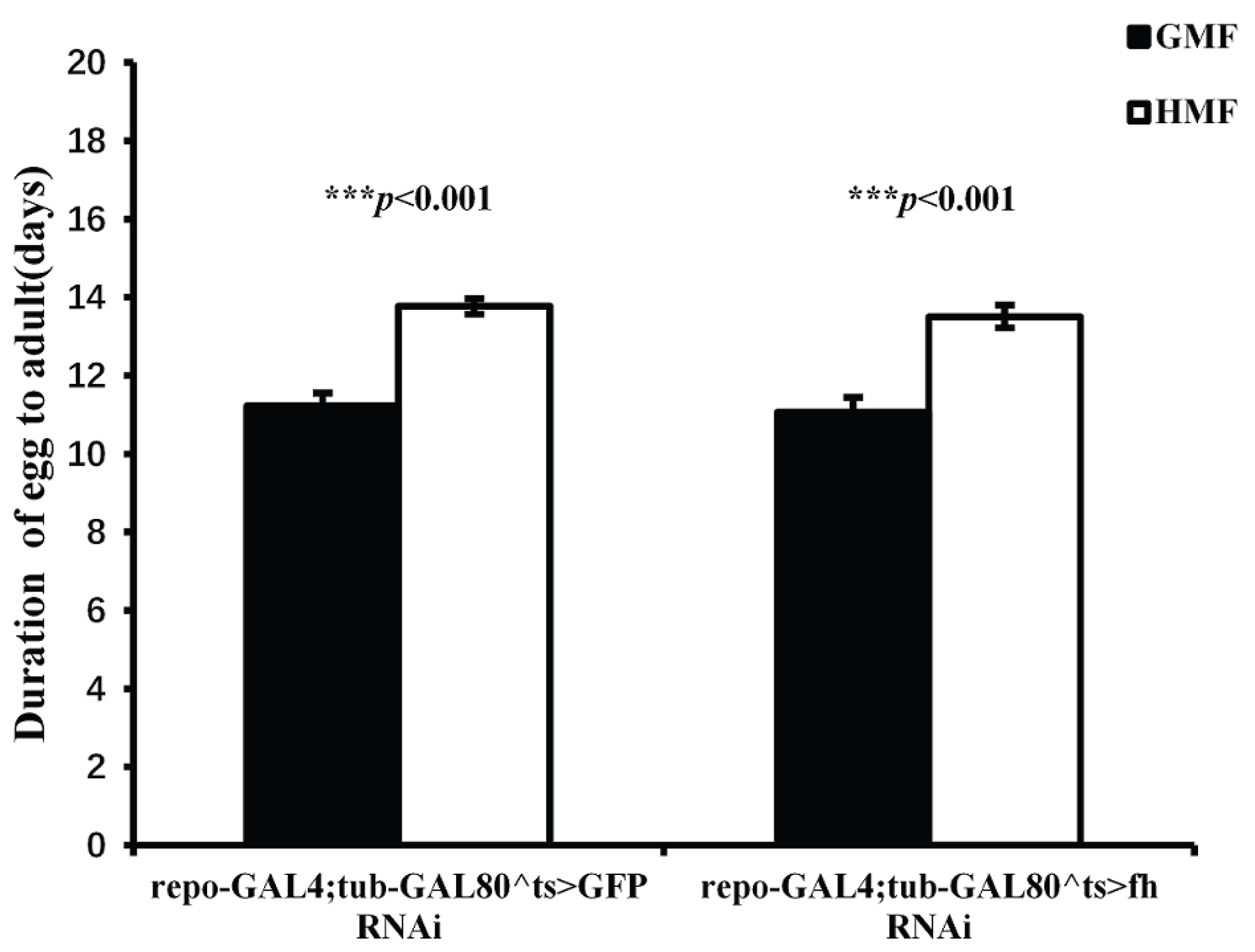

3.2. Hypomagnetic Field Exposure Extended Egg to Adult Developmental Duration in GFP-RNAi and fh-RNAi Flies

HMF significantly increased the egg to adult developmental duration of GFP-RNAi (

P<0.001) and fh-RNAi flies(

P<0.001) (

Figure 4). Compared with GMF, HMF significantly extended the egg to adult developmental duration of GFP-RNAi and fh-RNAi by a mean value of 22.69% and 22.13%, respectively (

P<0.05). A two-way ANOVA with genotype (repo-GAL4;tub-GAL80^ts>GFP-RNAi

vs repo-GAL4;tub-GAL80^ts>fh-RNAi) and field (GMF

vs HMF) showed a significant main effect of field (F=115.51,

P<0.001), but no significant main effect of genotype(F=1.41,

P=0.235>0.05) and no genotype × field interaction (F=0.045,

P=0.832>0.05).

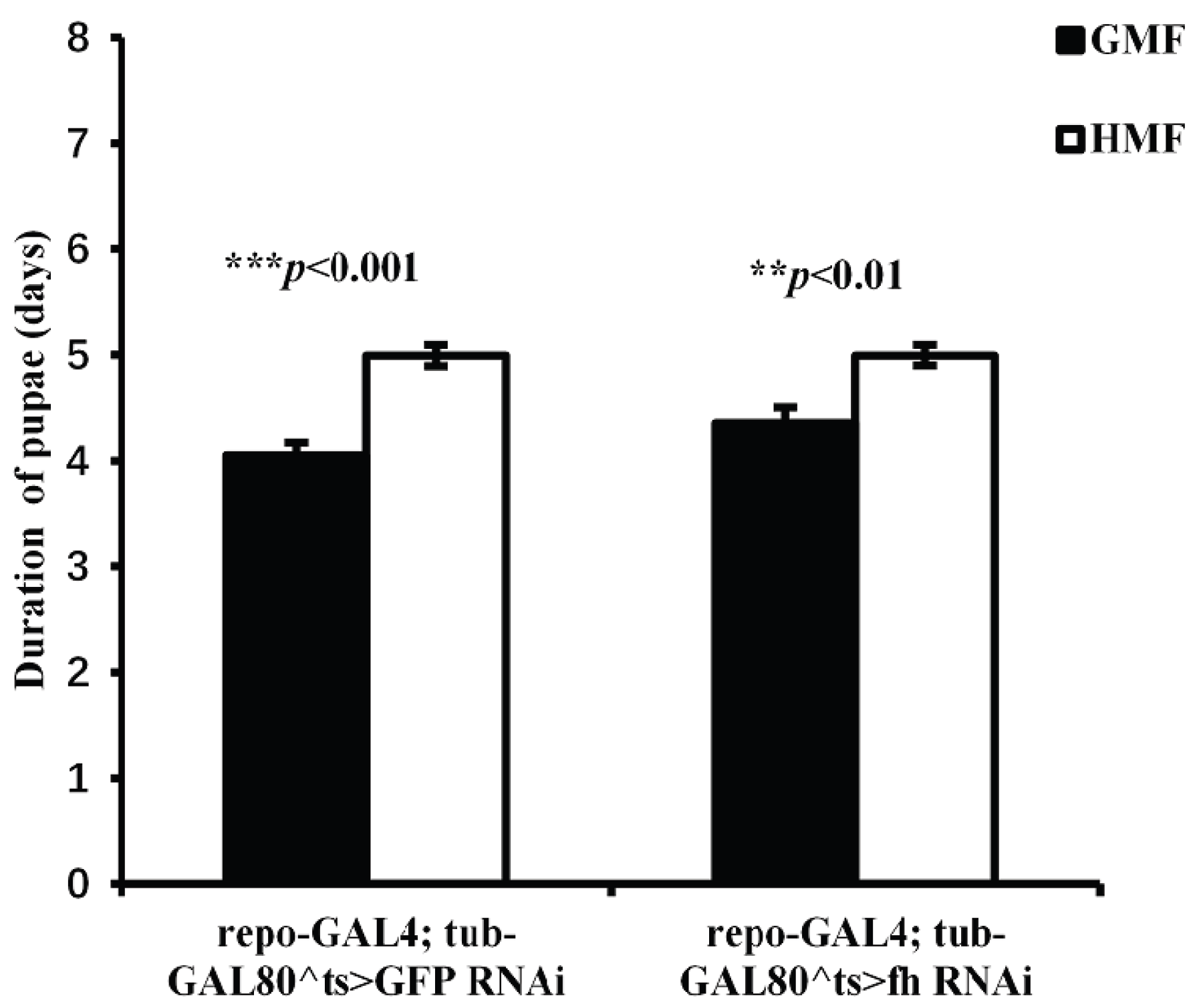

3.3. Hypomagnetic Field Exposure Enhanced Pupal Developmental Duration in GFP-RNAi and fh-RNAi flies

Exposure to HMF significantly extended the pupal developmental duration in both GFP-RNAi (

P<0.001) and fh-RNAi flies (

P<0.01) compared to GMF. The mean prolongation was 23.15% for GFP-RNAi and 14.70% for fh-RNAi flies (

P<0.05) (

Figure 5). A two-way ANOVA for genotype (repo-GAL4;tub-GAL80^ts>GFP-RNAi

vs repo-GAL4;tub-GAL80^ts>fh-RNAi) × magnetic field (GMF

vs HMF) revealed a significant main effect of magnetic field (F=36.51,

P<0.001), while the main effect of genotype (F=0.627, P=0.429) and the genotype × magnetic field interaction (F=1.32, P=0.252) were not significant.

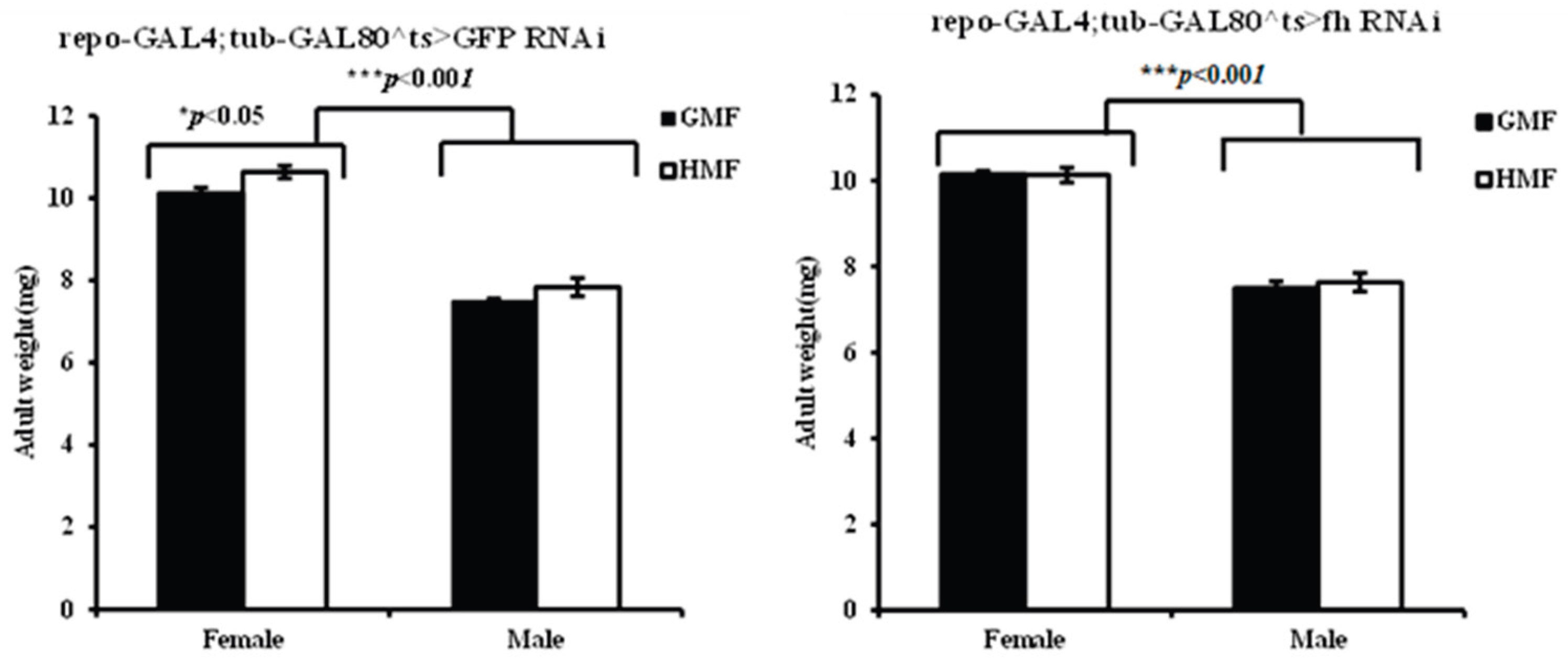

3.4. Hypomagnetic Field Exposure Shows No Significant Effect on Adult Weight of fh-RNAi Flies

For GFP-RNAi flies, we found a significant effect of magnetic fields (F=4.98,

P<0.05) and a strong effect of sex (F=201.51,

P<0.001) on adult weight, but no significant interaction between these factors (F=0.23,

P>0.05) (

Figure 6). In contrast, magnetic fields had no significant effect on the weight of fh-RNAi flies (F=0.13,

P>0.05), although a strong sexual dimorphism was still present (F=245.45,

P<0.001). Similarly, no significant interaction between magnetic fields and sex was observed in the fh-RNAi group (F=0.21,

P>0.05).

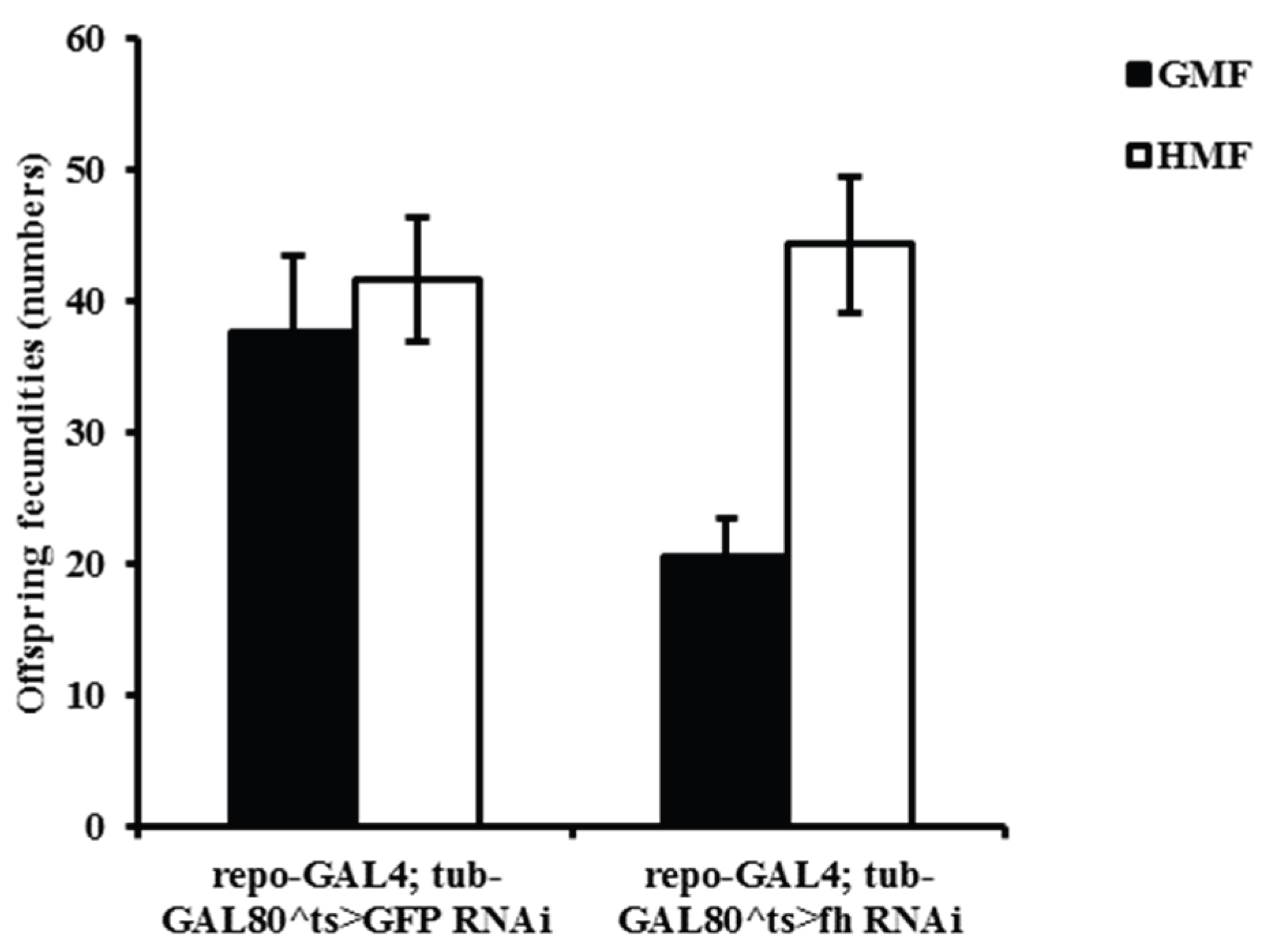

3.5. Hypomagnetic Field Exposure Increased Offspring Fecundity in Drosophila Flies

Magnetic fields significantly affected the offspring fecundity of fh-RNAi flies. Under HMF, the number of offspring increased by a mean of 10.60% (

P=0.9325, not significant) in control flies (GFP-RNAi) and by 114.52% in fh-RNAi (

P<0.05) flies compared to GMF (

Figure 7). A two-way ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of magnetic field (F=8.31,

P<0.05) on offspring fertility, but no significant main effect of genotype (F=2.23,

P=0.17). The genotype × magnetic Field interaction showed a non-significant trend (F=4.20,

P=0.07).

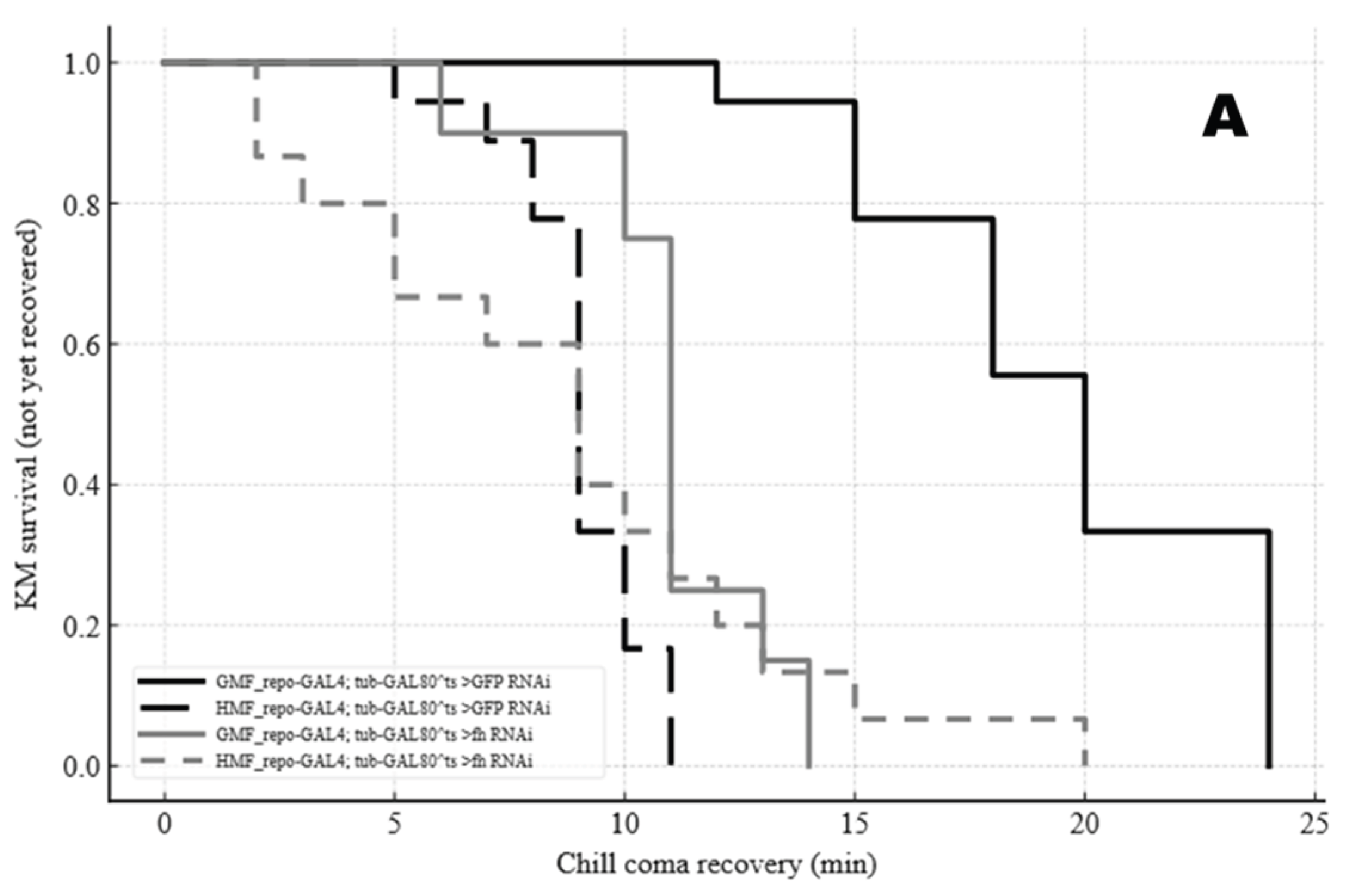

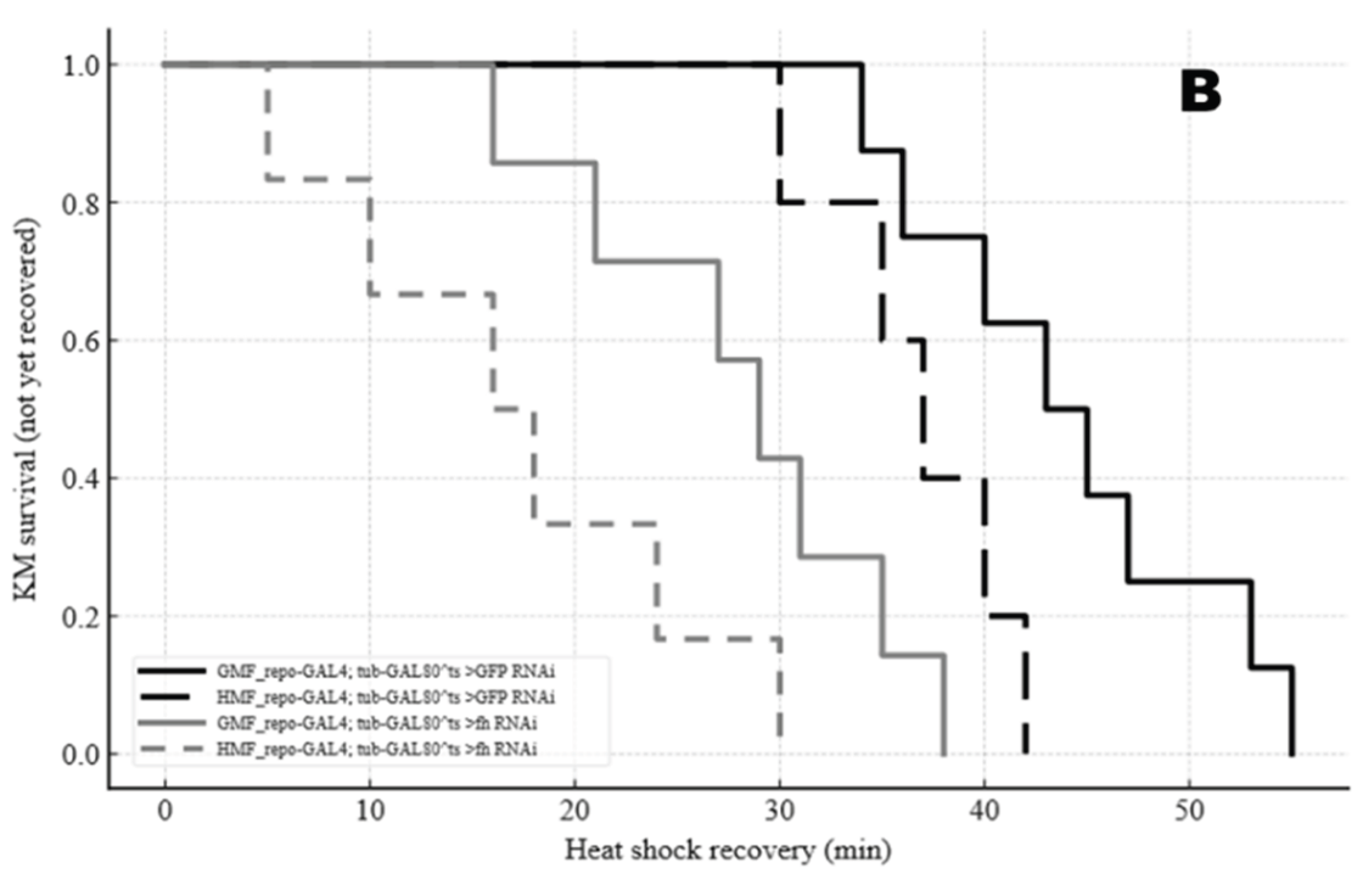

3.6. Hypomagnetic Field Modulated the Response of Drosophila Flies to Temperature Stress

During recovery from chill coma stress, flies generally recovered faster in the HMF than in the GMF, and those with frataxin silencing (fh-RNAi) recovered faster than the GFP-RNAi controls. The effect of the genotype was more pronounced under GMF conditions, where the difference was significant, than under HMF, where it was not (

Figure 8A). A similar pattern was observed during heat shock recovery, with HMF and fh-RNAi each conferring a faster recovery, and a significant interaction between magnetic field and genotype (

Figure 8B).

Statistical analysis confirmed significant main effects of MF (F=55.74, P<0.001), genotype (F=72.43, P<0.001), and stress (F=324.41, P<0.001). Significant MF × genotype (F=7.23, P=0.0086) and genotype × stress (F=33.63, P<0.001) interactions, as well as a significant three-way interaction (MF × genotype × stress)(F=7.53, P=0.0073) were observed , indicating that the magnitude of the MF effect depends on both genotype and the type of thermal stress.

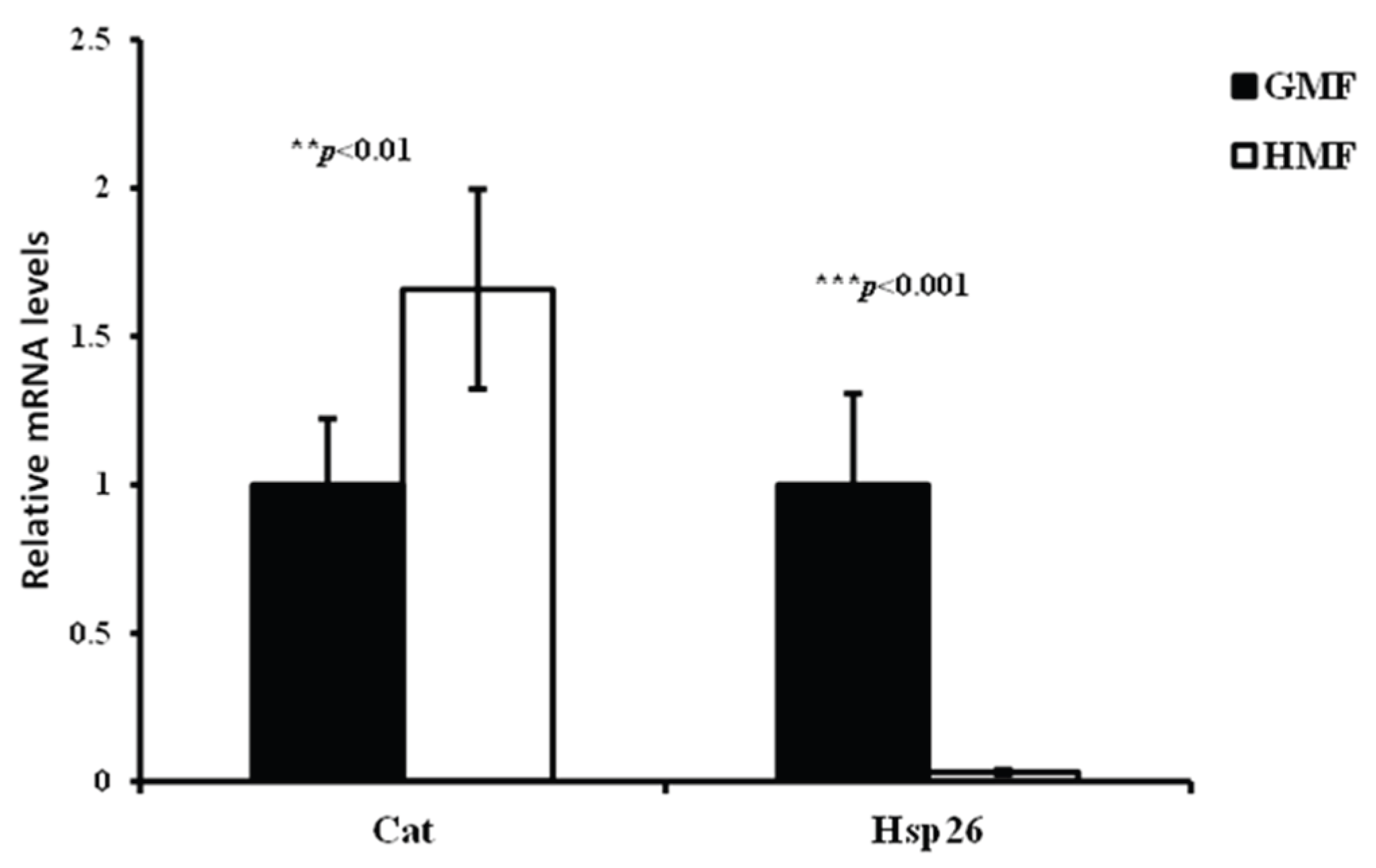

3.7. The Relative Cat and Hsp26 Transcript Levels of fh-RNAi Flies Between HMF and GMF

One-way ANOVA indicated that magnetic fields significantly affected Cat (F=12.43297, P<0.01) and Hsp26 (F=58.7924, P<0.001) genes expression levels in fh-RNAi flies. Compared with GMF, HMF increased the relative Cat transcript level by 66% in fh-RNAi flies, while it significantly decreased the relative Hsp26 transcript level by 96.8% in fh-RNAi flies.

Figure 9.

Quantification of Cat and Hsp26 transcripts under GMF and HMF. qRT-PCRs were performed on whole RNA extracts of 3 to 8 days-old adult heads (3 samples of 30 heads per genotype). Significant differences are shown at **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 (One-way ANOVA with Welch t-test performed for each group). The columns represent averages with vertical bars indicating SE.

Figure 9.

Quantification of Cat and Hsp26 transcripts under GMF and HMF. qRT-PCRs were performed on whole RNA extracts of 3 to 8 days-old adult heads (3 samples of 30 heads per genotype). Significant differences are shown at **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 (One-way ANOVA with Welch t-test performed for each group). The columns represent averages with vertical bars indicating SE.

4. Discussion

This study provides the first evidence of the multidimensional effects of hypomagnetic field on frataxin-deficient Drosophila melanogaster. Notably, while HMF exposure extended developmental duration and increased offspring fecundity of Drosophila flies, it unexpectedly increased their responses to temperature stress, implying that the absence of geomagnetic field may reshape energy allocation strategies by interfering with frataxin-related pathways for sacrificing growth rates to enhance stress defenses. Interestingly, the present study found increased offspring fecundity in frataxin-deficient flies under HMF exposure, suggesting the role of frataxin in the reproduction of Drosophila flies with changed magnetic field.

Generally, the early stages of development with periods of cell differentiation are most sensitive to the exposure of magnetic fields. Compared with GMF, HMF significantly increased the egg to adult duration of both GFP control and frataxin-deficient flies by a mean value of 22.69% and 22.13%, respectively. The circumstance is quite similar with the effects observed on brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens, except a smaller mean egg duration of 7.42% for N. lugens. It is reported that strong magnetic fields can also prolong the duration of egg to adult development (Pan, 1996; Pan, 2004), implying a common primary physical mechanism of magnetic effects on embryonic development. Two-way ANOVAs indicated that magnetic fields significantly affected offspring fecundity of fh-RNAi flies. Compared with GMF, HMF increased the number of offspring of GFP-RNAi and fh-RNAi flies, which was in contrast with decreased fertility observed in small planthopper Laodelphax striatellus and brown planthopper N. lugens, as well as no significant effects were observed on the fecundity of macropterous female adults mated with macropterous male adults of white-backed planthopper, Sogatella furcifera under HMF (Wan et al.,2015). It is noted that compared with GMF, HMF showed no significant effects on adult weight of fh-RNAi flies, while increased adult weight was observed in GFP-RNAi flies.

On the other hand, the effects of HMF are jointly modulated by genotype and temperature paradigm. During chill coma recovery, a significant MF × genotype interaction was observed: HMF significantly shortened recovery in the GFP background, whereas this contrast was non-significant in the frataxin gene-silenced background. Conversely, during heat recovery, MF and genotype both significantly shortened recovery time independently—HMF and frataxin gene silencing each exerted this effect. While HMF and frataxin silencing each shorten recovery time, the magnitude of the HMF effect is context-dependent: it is large in GFP-RNAi controls during chill coma recovery, more modest in fh-RNAi flies during chill coma, and consistently beneficial during heat shock. Collectively, whether and to what extent HMF accelerates recovery depends on genotype and stress paradigm, reflecting the context-dependent nature of magnetic field effects.

Chill coma recovery and heat shock recovery depend on the rapid re-establishment of ionic homeostasis, a process that requires adequate mitochondrial functionality (Jonas et al.,2015; MacMillan et al., 2012; Franco-Obregón, 2023). It has been proposed that loss of mitochondrial frataxin triggers a hypoxia-like, iron starvation process and causally involved ROS production that directly contributes to cellular toxicity (Al-Mahdawi et al., 2006; Anderson et al., 2008; Calabrese et al., 2005; Schulz et al., 2000). In our study, the Cat transcript was increased and Hsp26 transcript was decreased under HMF exposure, indicating the close associations between ROS & thermal stress and HMF. However, at the least level of HMF exposure, frataxin deficiency did not render more toxicity to adult flies as the temperature stress resistance was enhanced rather than decreased. In addition, differences in response to HMF between GFP-RNAi and fh-RNAi flies support the role of frataxin in magnetic field sensitivity (Calap-Quintana et al.,2018; Shan et al.,2013; Guo et al.,2021; Zadeh-Haghighi et al., 2023). Nevertheless, current experiments have only focused on acute HMF exposure (1-2 generations), failing to reflect epigenetic changes after multi-generational acclimatization.

5. Conclusions

In this study, hypomagnetic fields extended egg to adult and pupa developmental durations and increased the offspring fecundity of both GFP-RNAi and fh-RNAi flies, while showing no significant effects on adult weight of fh-RNAi flies compared to those reared under GMF. The impact of HMF on temperature stress resistance was particularly specific: it enhanced recovery from chill coma in control (GFP-RNAi) flies, while it accelerated recovery from heat shock in frataxin-silenced (fh-RNAi) flies. Our findings suggest that hypomagnetic fields are adverse for the growth and development but in favor of the reproduction and temperature stress resistance to certain extent in frataxin silencing Drosophila flies. Further studies are needed to better understand the mechanisms by which HMF affects the frataxin-associated traits at the primary physical level through the life span of Drosophila flies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Weidong Pan and Huiming Kang; methodology, Huiming Kang and Junzheng Zhang; formal analysis, Huiming Kang; investigation, Huiming Kang; resources, Junzheng Zhang; data curation, Huiming Kang; writing—original draft preparation, Huiming Kang; writing—review and editing, Weidong Pan and Guijun Wan; supervision, Weidong Pan; project administration, Weidong Pan; funding acquisition, Weidong Pan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32271286, 32172414), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20221510).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32271286, 32172414), and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20221510). We thank our technical group for their assistance with the exposure equipment.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| fh |

Frataxin |

| GFP |

Green fluorescent protein |

| CAT |

Catalase |

| HSP26 |

Heat shock protein 26 |

References

- Able, K.P. 1994. Magnetic orientation and magnetoreception in birds. Prog. Neurobiol. 42: 449-473. [CrossRef]

- Alerstam, T. 2003. Animal behavior: the lobster navigators. Nature 421:27-28. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mahdawi, S. R.M. Pinto, D. Varshney, L. Lawrence, M.B. Lowrie, S. Hughes, Z. Webster, J. Blake, J.M. Cooper, R. King, and M.A. Pook. 2006. GAA repeat expansion mutation mouse models of Friedreich ataxia exhibit oxidative stress leading to progressive neuronal and cardiac pathology. Genomics 88:580-590. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.R. , K. Kim, A. J. Hilliker, and J. P. Phillips. 2005. RNAi-mediated suppression of the mitochondrial iron chaperone, frataxin, in Drosophila. Human molecular genetics 14(22): 3397-3405. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, P.R. , K. Kirby, W.C. Orr, A.J. Hilliker, and J.P. Phillips. 2008. Hydrogen peroxide scavenging rescues frataxin deficiency in a Drosophila model of Friedreich’s ataxia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105:611-616. [CrossRef]

- Apolloni, S. , M. Milani, and N. D’Ambrosi. 2022. Neuroinflammation in Friedreich’s ataxia. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23(11):6297. [CrossRef]

- Bekenstein, U. , & Kadener, S. 2011. What can Drosophila teach us about iron-accumulation neurodegenerative disorders ? Journal of neural transmission (Vienna, Austria: 1996), 118(3), 389–396. [CrossRef]

- Bosch, J. A. , Sumabat, T. M., & Hariharan, I. K. 2016. Persistence of RNAi-Mediated Knockdown in Drosophila Complicates Mosaic Analysis Yet Enables Highly Sensitive Lineage Tracing. Genetics 203(1), 109–118. [CrossRef]

- Busi, M.V. , and D.F. Gomez-Casati. 2012. Exploring frataxin function. IUBMB Life 64:56-63. [CrossRef]

- Cabiscol, E., Tamarit, J., & Ros, J. 2000. Oxidative stress in bacteria and protein damage by reactive oxygen species. International microbiology: the official journal of the Spanish Society for Microbiology, 3(1), 3–8.

- Calabrese, V. , R. Lodi, C. Tonon, V. D’Agata, M. Sapienza, G. Scapagnini, A. Mangiameli, G. Pennisi, A.M. Stella, and D.A. Butterfield. 2005. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular stress response in Friedreich’s ataxia. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 233:145-162. [CrossRef]

- Calap-Quintana, P. , J.A. Navarro, J. González-Fernández, M. J. Martínez-Sebastián, M. D. Moltó, and J. V Llorens. 2018. Drosophila melanogaster models of Friedreich’s ataxia. BioMed Research International 2018: 5065190. [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, V. , L. Montermini, M.D. Molto, L. Pianese, M. Cossee, F. Cavalcanti, E. Monros, F. Rodius, F. Duclos, and A. Monticelli. 1996. Friedreich’s ataxia: autosomal recessive disease caused by an intronic GAA triplet repeat expansion. Science 271:1423-1427. [CrossRef]

- Chen, K. , G. Lin, N.A. Haelterman, T.S. Ho, T. Li, Z. Li, L. Duraine, B. H. Graham, M. Jaiswal, S. Yamamoto, et al. 2016. Loss of Frataxin induces iron toxicity, sphingolipid synthesis, and Pdk1/Mef2 activation, leading to neurodegeneration. ELife 5: e16043. [CrossRef]

- Creanga, D.E. , V. V. Morariu, and R.M. Isac. 2002. Life in zero magnetic field. IV. Investigation of developmental effects on fruitfly vision. Electromagnetic biology and medicine 21(1): 31-41. [CrossRef]

- Edenharter, O. , J. Clement, S. Schneuwly, and J. A. Navarro. 2017. Overexpression of Drosophila frataxin triggers cell death in an iron-dependent manner. Journal of neurogenetics 31(4):189-202. [CrossRef]

- Edenharter, O. , S. Schneuwly, and J. A. Navarro. 2018. Mitofusin-dependent ER Stress triggers glial dysfunction and nervous system degeneration in a Drosophila model of Friedreich’s ataxia. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 11:38. [CrossRef]

- Franco-Obregón, A. 2023. Harmonizing magnetic mitohormetic regenerative strategies: developmental implications of a calcium-mitochondrial axis invoked by magnetic field exposure. Bioengineering (Basel, Switzerland), 10(10), 1176.

- Gao, Y.B., and B.P. Zhai. 2010. Progress in the mechanisms of insect orientation. Chin. Bull. Entomol. 47(6):1055-1065. (In Chinese).

- Gibson, T. J. , Koonin, E. V., Musco, G., Pastore, A., & Bork, P. 1996. Friedreich’s ataxia protein: phylogenetic evidence for mitochondrial dysfunction. Trends in neurosciences 19(11), 465–468. [CrossRef]

- Grinberg, M. , and V. Vodeneev. 2025. The role of signaling systems of plant in responding to key astrophysical factors: increased ionizing radiation, near-null magnetic field and microgravity. Planta 261(2):1-21. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z. , Xu, S., Chen, X., Wang, C., Yang, P., Qin, S., Zhao, C., Fei, F., Zhao, X., Tan, P. H., Wang, J., & Xie, C. (2021). Modulation of MagR magnetic properties via iron-sulfur cluster binding. Scientific reports, 11(1), 23941. [CrossRef]

- Hong F., T. 1995. Magnetic field effects on biomolecules, cells, and living organisms. Bio Systems, 36(3), 187–229. [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, S & Lohmann, K.J. 2008.Magnetoreception in animals. Physics Today,61(3),29-3. [CrossRef]

- Jonas, L. Andersen, Tommaso Manenti, Jesper G. Sørensen, Heath A. MacMillan,Volker Loeschcke & Johannes Overgaard. 2015.How to assess Drosophila cold tolerance: chill coma temperature and lower lethal temperature are the best predictors of cold distribution limits. Functional Ecology, 29(1),55-65. [CrossRef]

- Koutnikova, H. , V. Campuzano, F. Foury, P. Dolle, O. Cazzalini, and M Koenig. 1997. Studies of human, mouse and yeast homologues indicate a mitochondrial function for frataxin. Nat. Genet. 16:345-351. [CrossRef]

- Llorens, J.V. , J. A. Navarro, M. J. Martínez-Sebastián, M.K. Baylies, S. Schneuwly, J. A. Botella, and M.D. Moltó. 2007. Causative role of oxidative stress in a Drosophila model of Friedreich ataxia. FASEB Journal 21(2):333-344. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.K. , A. S. Zhan, Y.C. Fan, and L.X. Tian. 2022. Effects of hypomagnetic field on adult hippocampal neurogenic niche and neurogenesis in mice. Frontiers in Physics 10: 1075198. [CrossRef]

- MacMillan, H. A. , Williams, C. M., Staples, J. F., & Sinclair, B. J. (2012). Reestablishment of ion homeostasis during chill-coma recovery in the cricket Gryllus pennsylvanicus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109(50), 20750–20755.

- Marley, R. , C. N.G. Giachello, N. S. Scrutton, R.A. Baines, and A.R. Jones. 2014. Cryptochrome-dependent magnetic field effect on seizure response in Drosophila larvae. Scientific Reports 4(1): 5799. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, E.A. , C. Gomez-Perretta, and F. Montes. 2016. Low intensity magnetic field influences short-term memory: A study in a group of healthy students. Bioelectromagnetics 37(1):37-48. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, J.A. , E. Ohmann, D. Sanchez, J. A. Botella, G. Liebisch, M. D. Moltó, M.D. Ganfornina, G. Schmitz, and S. Schneuwly. 2010. Altered lipid metabolism in a Drosophila model of Friedreich’s ataxia. Human molecular genetics 19(14): 2828-2840. [CrossRef]

- Ogneva, I. V. , M. A. Usik, M. V. Burtseva, N. S. Biryukov, Y. S. Zhdankina, V. N. Sychev, and O. I. Orlov. 2020. Drosophila melanogaster sperm under simulated microgravity and a hypomagnetic field: motility and cell respiration. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21(17): 5985. [CrossRef]

- Pan, H. 1996. The effect of a 7 T magnetic field on the egg hatching of Heliothis virescens. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 14(6): 673-677. [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.J. , and X. H. Liu. 2004. Apparent biological effect of strong magnetic field on mosquito egg hatching. Bioelectromagnetics 25(2): 84-91. [CrossRef]

- Runko, A.P. , A. J. Griswold, and K.T.Min. 2008. Overexpression of frataxin in the mitochondria increases resistance to oxidative stress and extends lifespan in Drosophila. FEBS Letters 582(5): 715-719. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, J.B. , T. Dehmer, L. Schöls, H. Mende, C. Hardt, M. Vorgerd, K. Bürk, W. Matson, J. Dichgans, M.F. Beal, et al. 2000. Oxidative stress in patients with Friedreich ataxia. Neurology 55:1719-172. [CrossRef]

- Seguin, A. , V. Monnier, A. Palandri, F. Bihel, M. Rera, M. Schmitt, J. M. Camadro, H. Tricoire, and L. Emmanuel. 2015. A yeast/Drosophila screen to identify new compounds overcoming frataxin deficiency. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2015: 565140. [CrossRef]

- Shan, Y. , Schoenfeld, R. A., Hayashi, G., Napoli, E., Akiyama, T., Iodi Carstens, M., Carstens, E. E., Pook, M. A., & Cortopassi, G. A. (2013). Frataxin deficiency leads to defects in expression of antioxidants and Nrf2 expression in dorsal root ganglia of the Friedreich’s ataxia YG8R mouse model. Antioxidants & redox signaling 19(13), 1481–1493. [CrossRef]

- Sinčák, M. , and J. SedlakovaKadukova. 2023. Hypomagnetic fields and their multilevel effects on living organisms. Processes 11(1):282. [CrossRef]

- Sizova, A. A. , D. A. Sizov, and V. V Krylov. 2023. Influence of hypomagnetic conditions and changes in water salinity on production and morphometric parameters of Daphnia magna straus. Russian Journal of Ecology 54(3): 236-242. [CrossRef]

- Steinhilber, F., J. A. Abreu, J. Beer, and K. G. McCracken. 2010. Interplanetary magnetic field during the past 9300 years inferred from cosmogenic radionuclides. J. Geophys. Res. 115 (A01104). 1104. [CrossRef]

- Tian, L. , Y. Luo, A. Zhan, J. Ren, H. Qin, and Y. Pan. 2022. Hypomagnetic field induces the production of reactive oxygen species and cognitive deficits in mice hippocampus. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23(7): 3622. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, J. E. , Livelo, C., Trujillo, A. S., Chandran, S., Woodworth, B., Andrade, L., Le, H. D., Manor, U., Panda, S., & Melkani, G. C. 2019. Time-restricted feeding restores muscle function in Drosophila models of obesity and circadian-rhythm disruption. Nature communications 10(1), 2700. [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.J. , S. L. Jiang, Z.C. Zhao, J.J. Xu, X.R. Tao, G.A. Sword, Y.B. Gao, W.D. Pan, and F.J. Chen. 2014.Bio-effects of near-zero magnetic fields on the growth, development and reproduction of small brown planthopper, Laodelphax striatellus and brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens. Journal of Insect Physiology 68:7-15. [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.J. , W. J. Wang, J.J. Xu, Q.F. Yang, M.J. Dai, F.J. Zhang, G.A. Sword, W.D. Pan, and F.J. Chen. 2015. Cryptochromes and hormone signal transduction under near-zero magnetic fields: new clues to magnetic field effects in a rice planthopper. PLoS ONE 10(7): e0132966. [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.J. , R. Yuan, W.J. Wang, K.Y. Fu, J.Y. Zhao, S.L. Jiang, W.D. Pan, G.A. Sword, and F.J. Chen. 2016. Reduced geomagnetic field may affect positive phototaxis and flight capacity of a migratory rice planthopper. Anim. Behav 121: 107-116. [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.J. , S. L. Jiang, M. Zhang, J.Y. Zhao, Y.C. Zhang, W.D. Pan, and F.J. Chen. 2020. Geomagnetic field absence reduces adult body weight of a migratory insect by disrupting feeding behavior and appetite regulation. Insect Science 28(1):251-260. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.X. , S. F. Wei, Y. Lu, Y.X. Zhang, C.F. Chen, and T. Song. 2013. Removal of the local geomagnetic field affects reproductive growth in Arabidopsis. Bioelectromagnetics 34(6): 437-442. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.J. , W. Pan, Y.C. Zhang, Y. Li, G.J. Wan, F.J. Chen, G.A. Sword, and W.D. Pan. 2017. Behavioral evidence for a magnetic sense in the oriental armyworm, Mythimna separata. Biol. Open 6(3): 340-347. [CrossRef]

- Xue, X.W. , Y. F. Ali, W.R. Luo, C.R. Liu, G.M. Zhou, and N. A. Liu. 2021. Biological effects of space hypomagnetic environment on circadian rhythm. Frontiers in Physiology 12: 643943. [CrossRef]

- Yan, M.M. , L. Zhang, Y.X. Cheng, T.W. Sappington, W.D. Pan, and X.F. Jiang. 2021.Effect of a near-zero magnetic field on development and flight of oriental armyworm (Mythimna separata). Journal of Integrative Agriculture 20(5):1336-1345. [CrossRef]

- Zadeh-Haghighi, H. , & Simon, C. 2022. Magnetic field effects in biology from the perspective of the radical pair mechanism. Journal of the Royal Society, Interface 19(193), 20220325, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh-Haghighi, H. , R. Rishabh, and C. Simon. 2023. Hypomagnetic field effects as a potential avenue for testing the radical pair mechanism in biology. Frontiers in Physics 11:1026460. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B. , H. M. Lu, W. Xi, X.J. Zhou, S.Y. Xu, K. Zhang, J.C. Jiang, Y. Li, and A.K. Guo. 2004. Exposure to hypomagnetic field space for multiple generations causes amnesia in Drosophila melanogaster. Neuroscience Letters 371(2-3): 190-195. [CrossRef]

- Zúñiga-Hernández, J. M. , Olivares, G. H., Olguín, P., & Glavic, A. 2023. Low-nutrient diet in Drosophila larvae stage causes enhancement in dopamine modulation in adult brain due epigenetic imprinting. Open Biology, 13(5), 230049.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).