1. Introduction

Sepsis is a life-threatening syndrome of dysregulated host response to infection that precipitates multiorgan dysfunction and substantial mortality [

1]. It is frequently complicated by coagulopathy and endothelial dysfunction, both of which worsen outcomes. Sepsis-induced coagulopathy (SIC) reflects early, systemic activation of coagulation with endothelial perturbation and microvascular thrombosis; progression to overt disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) further amplifies the risk of organ failure and death[

2,

3]. Although coagulation disorders were traditionally viewed as late-stage complications, recent work shows that coagulation abnormalities are present across the entire course of sepsis, influencing both onset and prognosis[

3].

Several bedside scoring systems are used to identify coagulopathy in sepsis, each with important limitations. The ISTH overt-DIC criteria include hypofibrinogenemia, which is relatively uncommon in septic DIC and may reduce sensitivity [

4] The JAAM DIC score incorporates systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) elements whose relevance has diminished under Sepsis-3 definitions[

5,

6]. More recently, the SIC criteria were introduced to enable earlier recognition[

7],however, while sensitivity for early mortality is improved, specificity remains limited. Thus, current systems do not consistently capture the dynamic pathophysiology of sepsis-associated coagulopathy or provide robust prognostic discrimination.

An additional limitation is that these criteria largely omit indices of cellular injury, endogenous anticoagulants, and the fibrinolytic–antifibrinolytic balance, despite their recognized roles in sepsis-related coagulopathy[

8]. Endothelial biomarkers—such as tissue-type plasminogen activator–inhibitor complex (t-PAIC) and soluble thrombomodulin (sTM)—have been associated with organ failure and death[

8,

9]. Similarly, hemostatic molecular markers including thrombin–antithrombin (TAT) complex, plasmin–α2-plasmin inhibitor complex (PIC), and the endogenous anticoagulant antithrombin (AT) provide early mechanistic signals of dysregulated coagulation and have demonstrated prognostic relevance[

9,

10].These markers illuminate the thromboinflammatory processes that conventional scores may overlook[

8],

Accordingly, there is growing consensus that DIC should not be viewed as a static, terminal event but rather as a continuum from compensated hypercoagulability (SIC) to decompensated overt DIC[

11]. Integrating molecular markers into established frameworks may bridge the gap between pathophysiology and clinical scoring, thereby enhancing early recognition, refining risk stratification, and improving outcome prediction. In this context, the present study evaluates the prognostic value of hemostatic and endothelial markers for 28-day mortality and developed a unified, ISTH-based score that augments conventional criteria with selected molecular markers.

4. Discussion

In sepsis, coagulopathy represents a pivotal driver of morbidity and mortality, yet conventional diagnostic frameworks remain limited in their ability to capture early, dynamic changes in the coagulation system. The ISTH overt-DIC criteria,[

4], while widely adopted, primarily identify advanced stages of DIC. and the proposed two-step approach [

18] using SIC for screening followed by ISTH confirmation still overlooks endothelial injury, a central mechanism in sepsis-associated coagulopathy. This gap underscores the need to evaluate additional markers that better reflect underlying pathophysiology.

In the present study, multivariable regression analyses demonstrated that endothelial and hemostatic molecular markers, specifically t-PAIC and TAT were the strongest independent predictors of mortality, with AUCs of 0.846 and 0.845, respectively. Antithrombin activity also showed strong prognostic value (AUC 0.789), while conventional coagulation parameters such as platelet count, PT, and fibrinogen were inferior predictors of survival. These findings are consistent with prior evidence that molecular markers of coagulation and endothelial injury change earlier than global coagulation indices and are strongly linked to organ dysfunction [

9,

19,

20,

21]. Thus, our results support the view that endothelial injury and impaired anticoagulant activity are not simply downstream effects of sepsis but are critical determinants of outcome in sepsis-induced DIC. The study further revealed that increased TAT and t-PAIC and decreased AT activity could serve as early indicators for the onset of sepsis-induced DIC. Correlation analysis confirmed that TAT and t-PAIC were significantly and positively correlated with SOFA scores, while AT activity was negatively correlated. These findings suggest that all three markers can assist in identifying the occurrence of DIC. Notably, only t-PAIC correlated positively with APACHE II scores, indicating its unique potential to reflect the overall severity of a patient’s condition. Since SOFA reflects the degree of organ dysfunction and APACHE II integrates acute physiology and chronic health, the consistent associations of these molecular markers with severity scores highlight their value in both prognosis and disease monitoring.

To address the gap of current scoring frameworks, we designed a Unified scoring system that incorporates three molecular elements; t-PAIC, TAT, and AT activity into the ISTH overt-DIC criteria. Each of these markers reflects a distinct but complementary domain of coagulopathy. t-PAIC, a complex of tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) and its inhibitor PAI-1, indicates fibrinolytic shutdown and endothelial dysfunction[

22,

23]. Elevated levels of t-PAIC have been consistently associated with poor outcomes and microvascular thrombosis[

9,

24]. Zhong and colleagues reported that serum t-PAIC concentrations ≥17.9 ng/mL were strongly associated with septic shock severity and acted as an independent risk factor for mortality in adults with sepsis[

24]. Similarly, Bai et al[

25]. and Li et al[

26]. demonstrated in pediatric cohorts that t-PAIC and TAT were independent predictors of severe sepsis, and only t-PAIC was consistently elevated in pediatric sepsis-induced coagulopathy, where it correlated with DIC scores, organ dysfunction, and longer ICU stays[

25]. In our study, serum t-PAIC levels >16 ng/mL were significantly associated with reduced 28-day survival and correlated with both SOFA and APACHE II scores, confirming its role as a sensitive marker of severity. Although not yet incorporated into diagnostic systems, evidence supports t-PAIC as a sensitive prognostic and diagnostic marker, justifying its inclusion in our unified model.

TAT, a complex of thrombin and antithrombin, reflects net thrombin generation and coagulation activation. Elevated TAT signals ongoing thrombin activity, which fuels microthrombosis, endothelial damage, and organ dysfunction[

27]. Antithrombin (AT), conversely, is a natural anticoagulant that regulates thrombin and factor Xa; its depletion in sepsis results from consumption, reduced synthesis, and degradation by neutrophil elastase[

28]. Decreased AT activity has been repeatedly shown to predict poor prognosis in septic DIC, and its integration with TAT improves diagnostic accuracy, particularly in early-stage disease[

29]. Guo et al. reported that in ICU patients with an ISTH-DIC score <5, the presence of TAT ≥10.8 ng/mL, AT activity ≤58%, or a TAT/AT ratio ≥22.1 predicted progression to overt and irreversible DIC within 7 days [

30]. Similarly, modified versions of the JAAM criteria have incorporated AT <70% in place of SIRS to enhance diagnostic precision in sepsis cohorts[

31].The Japanese Society on Thrombosis and Hemostasis (JSTH) criteria[

32] have previously incorporated markers such as TAT, soluble fibrin, and AT, where validation studies confirmed that their addition improved sensitivity for diagnosing pre-DIC and enhanced prognostic stratification[

33,

34,

35]

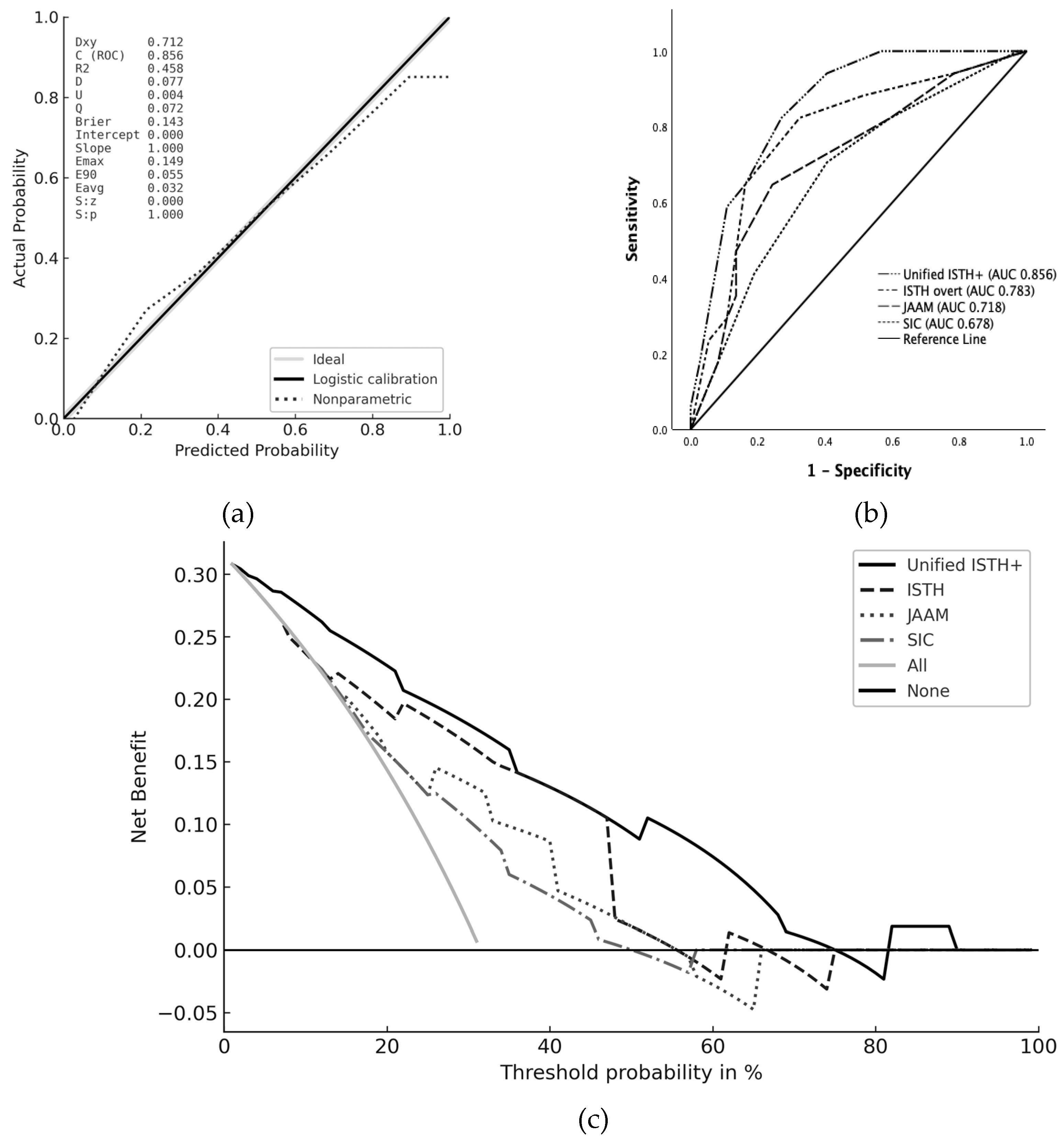

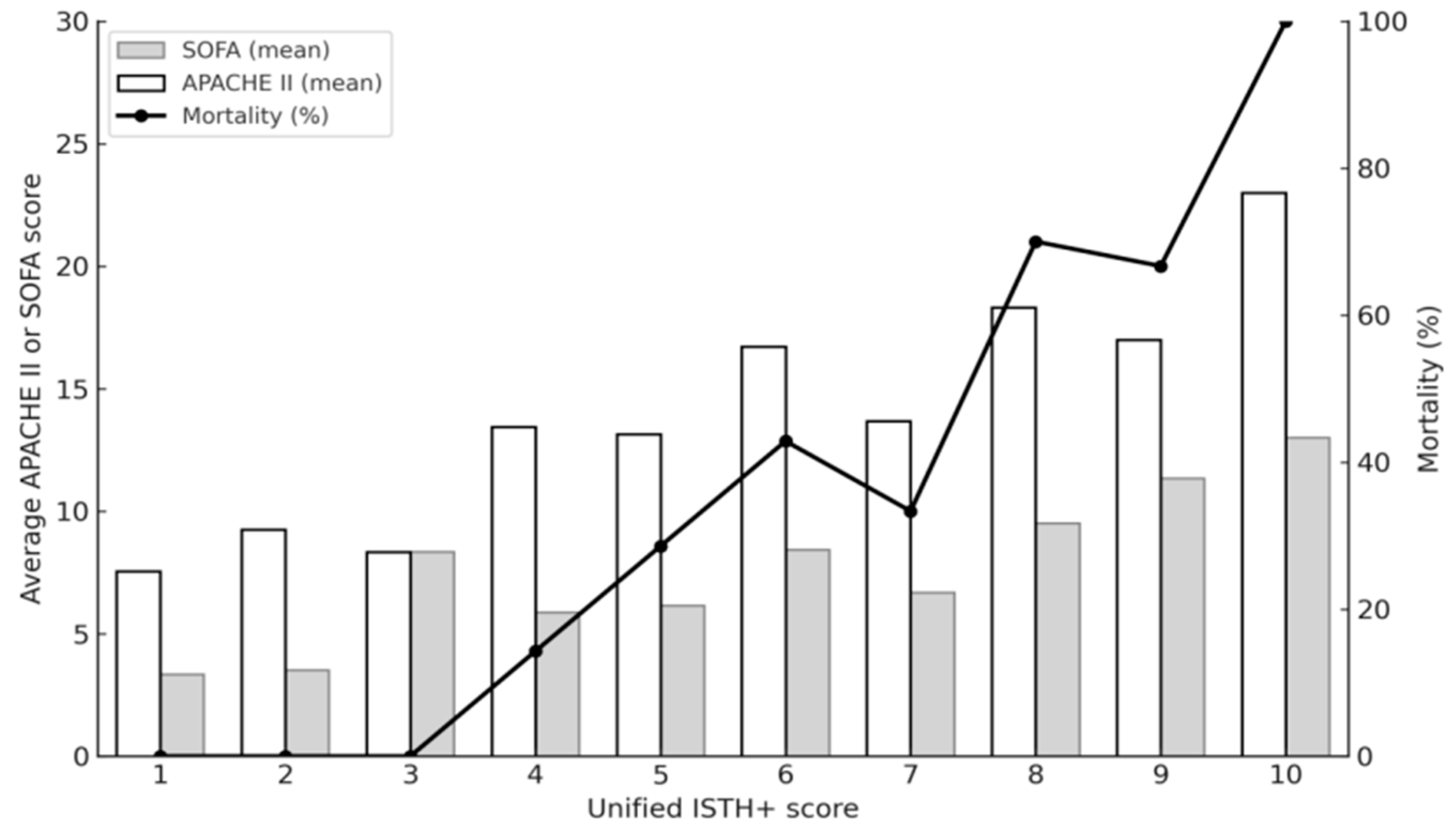

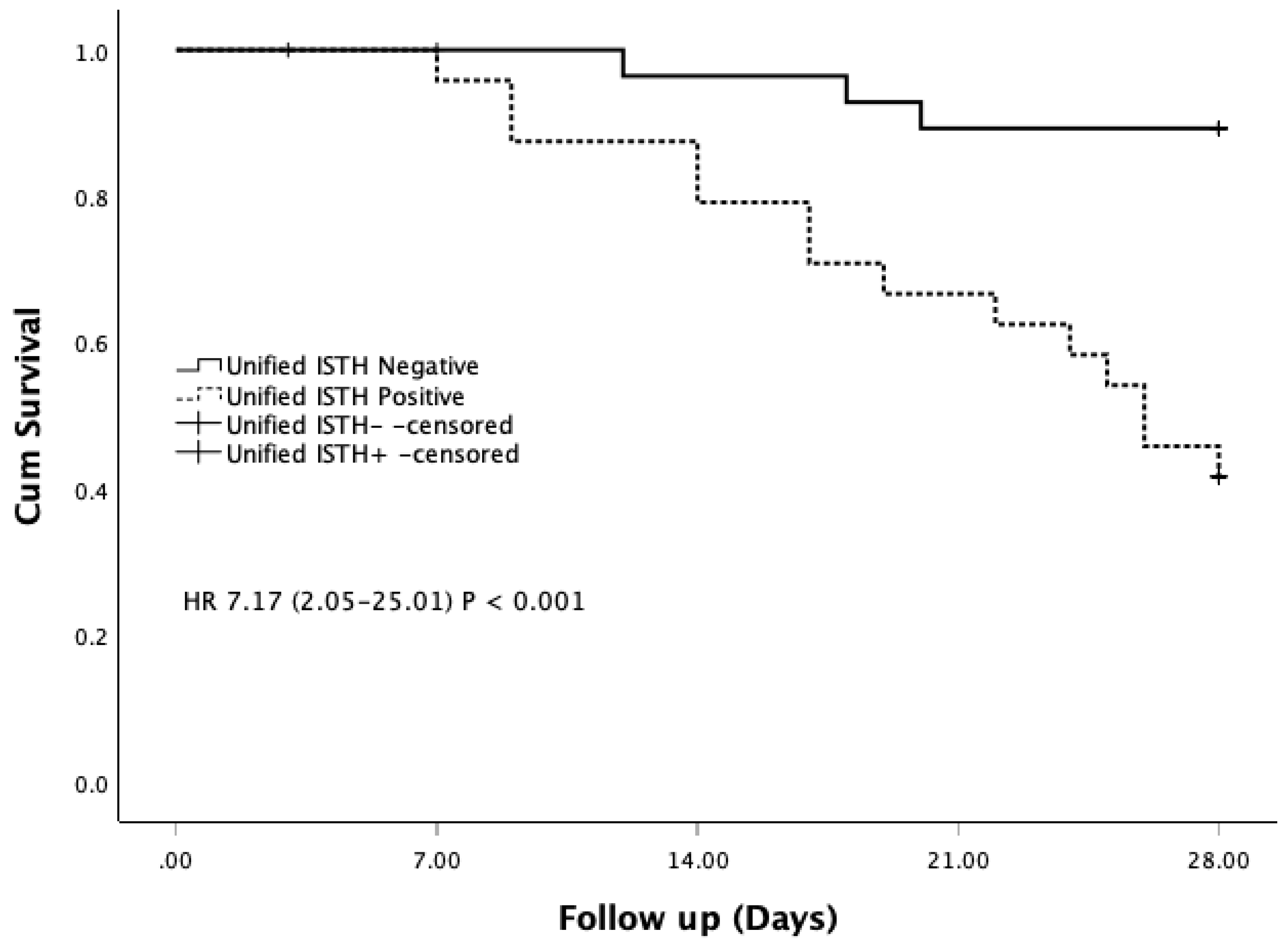

In our cohort, patients diagnosed with DIC by the Unified ISTH+ score had significantly higher APACHE II and SOFA scores, higher mortality, and greater rates of septic shock and organ dysfunction compared with non-DIC patients. These findings mirror previous studies showing that patients with DIC have more severe illness than those without [

19,

21,

36]. Importantly, the Unified ISTH+ score not only predicted mortality but also closely reflected disease severity, as shown by its correlations with SOFA and APACHE II. Compared with JAAM, SIC, and ISTH criteria, the Unified ISTH+ score demonstrated superior specificity for mortality prediction. Correlation analyses further confirmed that the Unified ISTH+ score aligned more closely with organ dysfunction scores, underscoring its improved clinical relevance. By integrating t-PAIC, TAT, and AT activity, the Unified ISTH+ system captures endothelial injury, thrombin generation, and anticoagulant depletion within one framework. This comprehensive approach offers earlier and more mechanistically anchored recognition of sepsis-associated DIC compared with conventional systems [

20,

21]. From a clinical perspective, management of sepsis-associated DIC still relies on treating the underlying infection, with the role of adjunctive anticoagulants remaining controversial[

11]. Large randomized trials of anticoagulants have not demonstrated survival benefits, likely due to patient heterogeneity [

37,

38]. Current consensus suggests anticoagulant therapy may be most beneficial in patients with confirmed sepsis-associated DIC and high severity of illness [

39,

40]. Although our study did not assess treatment according to the Unified ISTH+ score, its ability to identify patients at highest risk highlights its potential to guide earlier and more targeted therapeutic interventions.

Despite its promise, this study has several limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, and the single-center design limits generalizability. Second, only internal validation was performed; external validation across diverse cohorts is essential before the score can be widely recommended. Third, the measurement of endothelial and hemostatic molecular markers requires specialized assays not universally available and may be costly, posing barriers to routine clinical adoption. Future work should therefore focus on multicenter prospective validation, cost-effectiveness analyses, and exploration of simplified point-of-care testing strategies.