1. Introduction

COVID-19 patients face high risk of venous and arterial thrombotic events and death [

1]. Clinical trials have shown that antiplatelet therapy does not prevent thrombosis and does not reduce mortality [

2,

3,

4]. In contrast, anticoagulation therapy with low-molecular-weight heparins (LMWH) improves survival, lowers thrombosis risks, and it is recommended for all COVID-19 inpatients [

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, mortality in critically ill patients receiving LMWH remains unacceptably high and the incidence of thrombotic events can reach up to 24.1% [

9]. It has been suggested that these outcomes can be further improved by escalation of anticoagulation doses [

10,

11].

However, randomized clinical trials have shown that dose escalation does not improve survival in critically ill patients [

3,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Additionally, the effect of dose escalation on the rate of thrombotic events is unclear: some studies have shown a reduction in the thrombosis rate [

3,

13,

18], while the others do not support this [

12,

14,

15,

16,

17,

19]. It is unexpected, since critically ill patients frequently experience thrombotic events and have near-normal antithrombin III levels [

20,

21]. With uncertain benefits, escalated doses are associated with a higher rate of non-fatal bleeding in critically ill patients [

3,

13]. So, current guidelines recommend prophylactic doses for critically ill patients [

22]. In contrast, noncritically ill patients benefit from escalated doses, as they slightly improve their survival and do not increase the bleeding rates [

23,

24].

The reasons why escalated doses of anticoagulants fail to outperform prophylactic doses in preventing thrombotic complications and reducing mortality in critically ill COVID-19 patients remain poorly understood. It is possible that thrombus formation in these patients is driven by inflammation, and anticoagulation escalation does not decrease the tendency to pathological thrombus formation. However, another possibility is that escalated anticoagulation fails to prevent plasma hypercoagulability in critically ill patients and, consequently, does not reduce the risk of thrombosis and death.

Here we studied whether escalated (intermediate and therapeutic) LMWH or unfractionated heparin (UFH) prevented plasma hypercoagulability in COVID-19 patients. We also studied whether plasma hypercoagulability was associated with higher risks for thrombosis and death. We conducted a prospective multicenter study that enrolled 3860 patients, including 1654 critically ill. They received prophylactic, intermediate, and therapeutic doses of ‘heparins’ - LMWH or UFH. Coagulability parameters were assessed using activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), D-dimer, and the Thrombodynamics global plasma hemostasis assay [

25].

Previously, Thrombodynamics has been used to assess the risk of thrombotic events in septic patients, monitor heparin treatment in patients with high risks of venous thromboembolism (VTE), and correct episodic hypercoagulability in a limited cohort of COVID-19 patients [

26,

27,

28]. Thrombodynamics assay description and clinical application results are given in

Thrombodynamics.docx.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

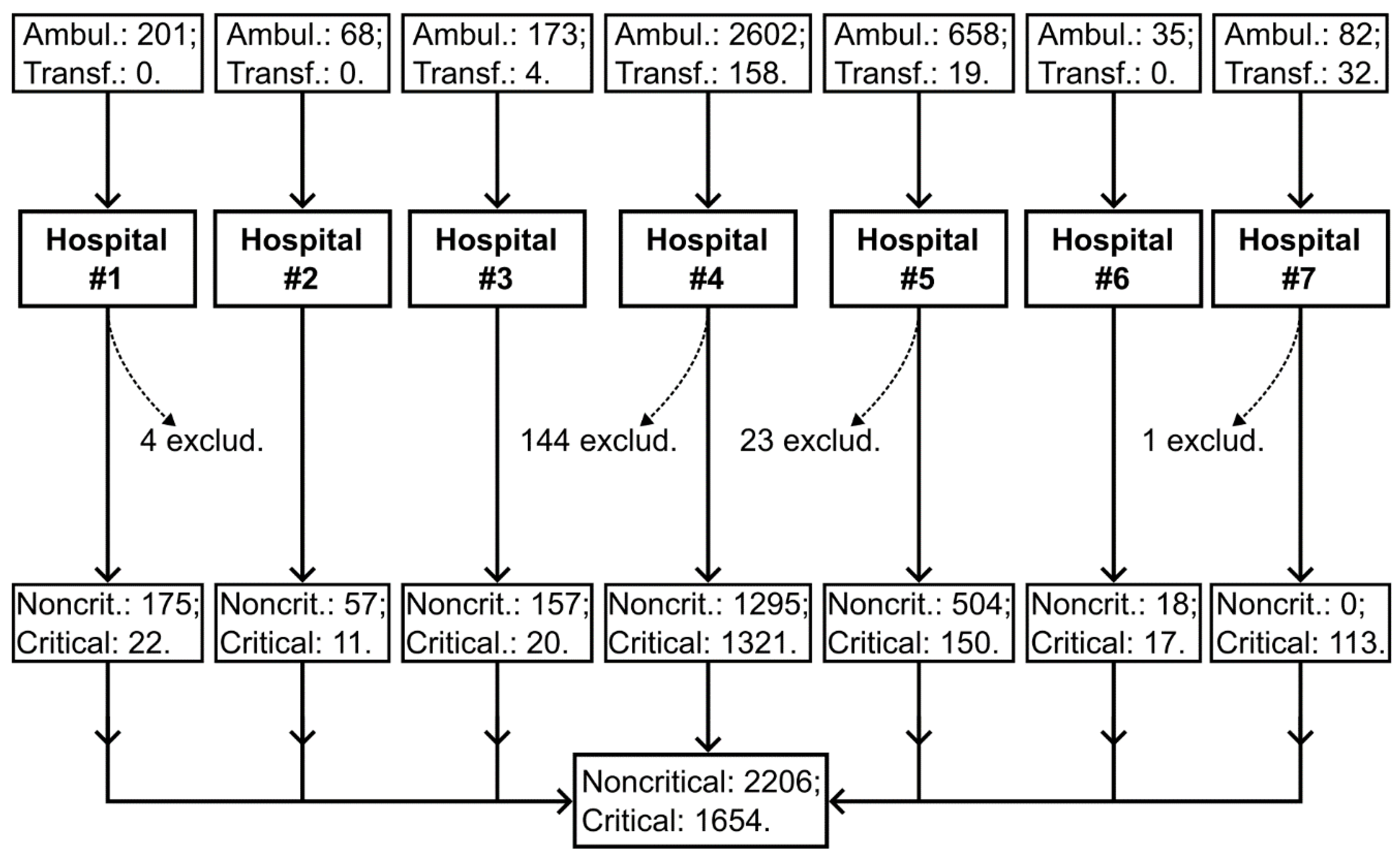

The prospective study was conducted from July 2020 to September 2021 in seven hospitals in Moscow, Russia. Patients were admitted from home via emergency medical services (ambulance) or transferred from other hospitals (

Figure 1). The participants were aged 18 and above, and COVID-19 diagnosis was confirmed through PCR. Individuals who did not meet these criteria were excluded. Patients were followed up until their in-hospital death or discharge. Their coagulability was assessed using APTT, D-dimer, and a clot growth rate in the Thrombodynamics assay (TDX-V). During the study, parameters of biochemistry and complete blood count were also assessed.

Blood samples were collected from the medial cubital vein or venous catheter. Samples for coagulability assays were collected upon admission to the hospital, before anticoagulation treatment was started. Subsequent samples were collected at the trough level of anticoagulation, at least every three days (in the morning while fasting), or daily in cases of critical illness, unless contraindications were present. For UFH infusion, where no clear trough level exists, samples were collected at least 6 hours after the bolus or after adjustment of the infusion rate.

Blood for coagulability assays was drawn into 4.5 ml plastic test tubes containing 3.2% sodium citrate (UNIVAC, Moscow, Russia). The initial 1–2 ml of blood was discarded into an empty tube.

Patients were regularly screened for thromboembolic complications or screenings were performed on an emergency basis if a thrombotic complication was suspected. Thrombotic events were identified by instrumental diagnosticians and radiologists and confirmed by the treating physicians of the patients. Computed tomography (with or without) angiography, ultrasound imaging results, or laparoscopy were used for identification. Three members of our research group reviewed these cases to determine whether they were acute events that occurred after the patients' admission to the hospital.

Electronic medical records were used to collect demographic data, treatments, assay results and outcomes. Data extraction was retrieval ensured and documented. Data were collected from August 2020 to October 2021.

All hospitalized patients were treated according to the temporary Russian Federation National Guidance for Treating COVID-19, using versions 6 to 12, which were valid during the study period (automatically translated version 12 is attached – NationalGuidance.docx). The following heparins were used during the study: prophylactic (UFH: ≤5000 IU TID s/c; dalteparin 5000 IU/day s/c; enoxaparin: 4000 IU/day s/c; nadroparin: 2850-3800 IU/day if <70 kg or 3800-5700 IU/day if ≥70 kg s/c), intermediate (UFH >5000 IU TID s/c; dalteparin 5000 IU/BID s/c; enoxaparin: 4000 IU/BID s/c; nadroparin: 3800-5700 IU/BID s/c) or therapeutic (UFH i/v infusion; dalteparin 100 IU/kg/BID s/c; enoxaparin: 100 IU/kg/BID s/c; nadroparin: 86-100 IU/kg/BID s/c).

Infusion of unfractionated heparin (UFH) began with a bolus dose of 80 units per kilogram of body weight followed by a continuous infusion of 18 units per hour per kilogram. The infusion rate was then adjusted based on APTT values (target range was 45–70 seconds; if <35 sec: 80 U/kg re-bolus and +4 U/kg/h; if 35–45 sec: 40 U/kg re-bolus and +2 U/kg/h; if 71–90 sec: –2 U/kg/h; if >90 sec: hold for one hour and then –3 U/kg/h). APTT was measured 3–4 times daily in patients receiving UFH infusion.

Patients were admitted to intensive care units (ICU) if two of the following criteria were met: 1) consciousness alterations, 2) SpO2 <92% while receiving respiratory support, 3) respiratory rate >35/min. Critical illness was defined as a requirement for admission to ICU during hospitalization.

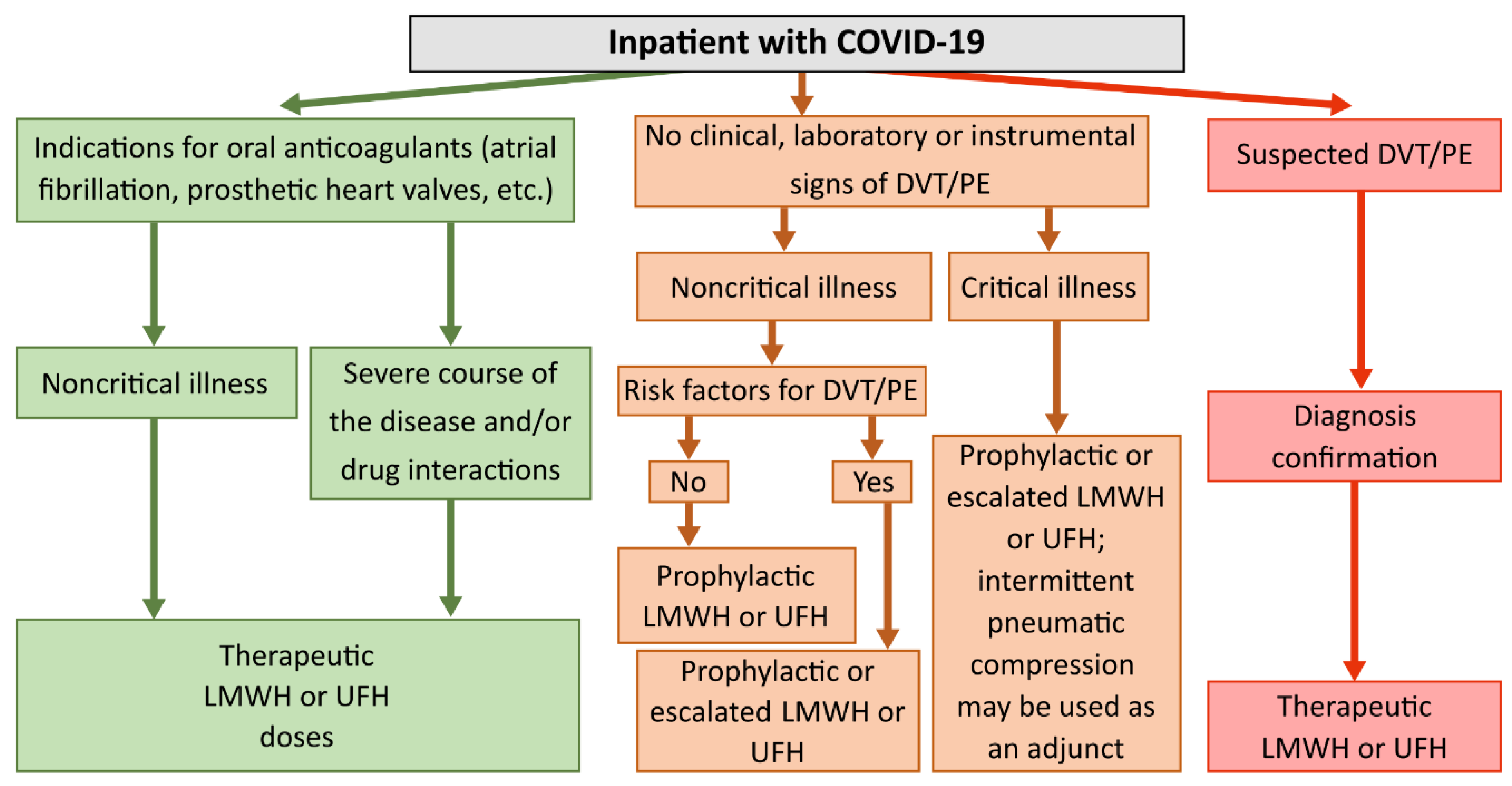

Therapeutic or intermediate doses of anticoagulants were recommended for patients in the intensive care unit (ICU), while prophylactic or intermediate doses were suggested for patients in the medical ward. Also, therapeutic doses of heparins were recommended for patients with atrial fibrillation, mechanical heart valves, or confirmed VTE/PE. Anticoagulation de-escalation was recommended for patients with kidney injury. Additionally, anticoagulant therapy could be temporarily lowered or discontinued in cases of bleeding, intubation, or surgical intervention. We did not analyze coagulability if anticoagulation was discontinued. A flowchart diagram of the algorithm for the dosing of LMWH and UFH based on the patient's history and clinical condition is given in

Figure 2.

Dosing of heparins based on patients' history and clinical condition could introduce bias into our study: e.g., it is possible that heparins effectiveness varied among critically ill patients with differing risk factors. We analyzed whether the group of critically ill patients was homogeneous in terms of Thrombodynamics clot growth rate — specifically, whether the obtained TDX-V distributions depended on the presence or absence of certain risk factors in patients. The results are described in the "Results" section (

Figures S1 and S2 of the Supplementary material – Supplement.docx).

2.2. Thrombodynamics Assay

Thrombodynamics test is used to assess plasma coagulability and monitor anticoagulation. It was conducted with a diagnostic system "Thrombodynamics Analyzer T2-F" (LLC HemaCore, Moscow, Russia) and kits provided by the manufacturer.

Briefly, this assay measures clot growth velocity (TDX-V) in platelet-free plasma initiated from a site with immobilized tissue factor (Bedford, MA, USA). A TDX-V >29 μm/min suggests hypercoagulability, a TDX-V <20 μm/min suggests hypocoagulability [

25].

An assay was performed no longer than one hour after blood collection. Blood samples were processed by centrifugation at 1600g for 15 min to obtain platelet-poor plasma. Then it was repeatedly processed by centrifugation at 10000g for 5 min to obtain platelet-free plasma, which was used for the assay. One-half milliliter of platelet-free plasma was frozen and kept at –80 °C. In the remaining platelet-free plasma, corn trypsin inhibitor (LLC Hemacore, Moscow, Russia) was added and the plasma was shaked. The plasma was then heated to 37 °C for 5 minutes, followed by the addition of calcium acetate (LLC Hemacore, Moscow, Russia), the plasma was shaked, after which the analysis was immediately performed at 37 °C.

2.3. Other Assays

Collected samples of platelet-free plasma were unfrozen at the room temperature and used for antithrombin III level measurements, which were performed according to the Liquid Antithrombin HemosIL kit protocol using an automated coagulometer ACL TOP 500 (Instrumentation Laboratory, MA, USA).

Other assays were performed in the hospitals by the staff of their clinical diagnostic laboratories using automated analyzers. The complete blood count was performed using hematological analyzers Sysmex XS-1000i (Japan) and Horiba Pentra XLR (France). The measurement of ferritin, C-reactive protein, creatinine, glucose, alanine and aspartate aminotransferases, lactate dehydrogenase, and bilirubin levels was carried out with automated biochemical analyzers Abbott Architect c4000 (USA) and ROCHE Cobas C311 (Switzerland) using the corresponding reagents. The analyses of APTT, PT, D-dimer, and fibrinogen were with automated coagulometers Sysmex CS 2100i (Sysmex Corporation, Kobe, Japan), ACL TOP 500 (Instrumentation Laboratory, MA, USA), and ACL TOP 300 (Instrumentation Laboratory, MA, USA).

2.4. Materials

Pathromtin SL (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH, Germany), SynthASil (Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA, USA), Thromborel S (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH, Germany), ThromboPlastin (Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA, USA), INR Validate (Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA, USA), INNOVANCE D-Dimer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH, Germany), D-dimer HS (Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA, USA), Dade Thrombin (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Products GmbH, Germany), QFA Fibrinogen (Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA, USA), Liquid Antithrombin HemosIL (Instrumentation Laboratory, Bedford, MA, USA).

2.5. Outcomes

The primary outcome was presence of hypercoagulability detected by Thrombodynamics clot growth rate in critically ill and noncritically ill patients (TDX-V >29 μm/min). The exposure was heparins dosage received by a patient. The collected data were used for a post-hoc analysis of association between hypercoagulability and thrombosis and death.

2.6. Ethics Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before any study-related procedures. The study protocol was approved by the Independent Ethical Committee of Dmitry Rogachev National Medical Research Center of Pediatric Hematology, Oncology, and Immunology, Ministry of Healthcare of Russia, Moscow. The study was carried out as part of the Covid-19 Associated Coagulopathy Predicted by Thrombodynamic Markers Clinical Trial (CoViTro-I; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT-05330832). All data were impersonalized prior to any statistical assessment. For data, please contact with the corresponding author.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis of continuous data was conducted using the two-sided Mann-Whitney U test. We did not check the distributions for normality. For categorical data, analysis was performed using the two-sided Fisher's exact test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Level of significance denotations: * – p-value <0.05, ** – p-value <0.01, *** – p-value <0.001. No corrections for multiple hypothesis testing were applied. Outliers were not excluded before the analysis. Density distributions were obtained using the non-parametric kernel density estimation method. No imputation methods were used to address missing data.

The Kaplan-Meier method was used to analyze time-to-event data. Continuous variables were standardized before analysis. The endpoints were death and thrombosis (venous or arterial). For each endpoint values of TDX-V, D-dimer, and APTT before the event were analyzed as independent variables. Patients who did not reach the endpoint due to discharge were right-censored. Cox regression was performed to estimate risk ratios under the assumption that risks were proportional: we found that the risks remained relatively constant in patients hospitalized up to 45 days, their data were analyzed. We also did not analyze data of patients who were hospitalized less than five days and of those, who had thrombosis before the third day of hospitalization. Data of patients with missing values were not analyzed. Patients’ age, sex, and body mass index were chosen as confounders.

ROC analysis was conducted to evaluate the specificity and sensitivity of various coagulation assays and to develop optimal models for predicting thrombosis and mortality using different combinations of coagulation markers.

3. Results

Of the 4032 patients, 3860 met the inclusion criteria (

Figure 2), 1654 of them were critically ill. Patient’s characteristics are given in

Table 1. VTE occurred in 474 patients, with deep vein thrombosis being the most common; arterial thromboembolism (ATE) occurred in 79 patients, with limb artery thrombosis being the most common (

Table 1).

3.1. Heparins Treated Baseline Hypercoagulability in the Majority of Patients

Thrombodynamics clot growth rates (TDX-V) were measured at admission before LMWH administration. On the subsequent days TDX-V were measured at the trough levels of LMWH pharmacological activity. The proportions of patients with hypercoagulability, normal coagulability, and hypocoagulability at these time points are given in

Table 2.

At admission, hypercoagulability (TDX-V >29 µm/min) was present in 75.6% of critically ill and 79.6% of noncritically ill patients. By the second day, the proportion of patients with hypercoagulability decreased to 28.0% in the group of critically ill patients and to 25.6% in the group of noncritically ill patients. At the same time, the proportion of patients with hypocoagulability (TDX-V <20 µm/min) increased from 7.1% to 53.4% in the critically ill group and from 3.1% to 42.1% in the noncritically ill group.

These changes in proportions were observed only up to the second day of hospitalization; in the subsequent days, the proportions of patients with hypercoagulability, hypocoagulability, and normal coagulability remained almost identical to those measured on day 2 (

Table 2).

This shows that LMWH exerted its entire treating effect within the first two days of hospitalization: hypercoagulability present at admission resolved in the majority of patients. However, in about one-quarter of patients, it persisted despite anticoagulation.

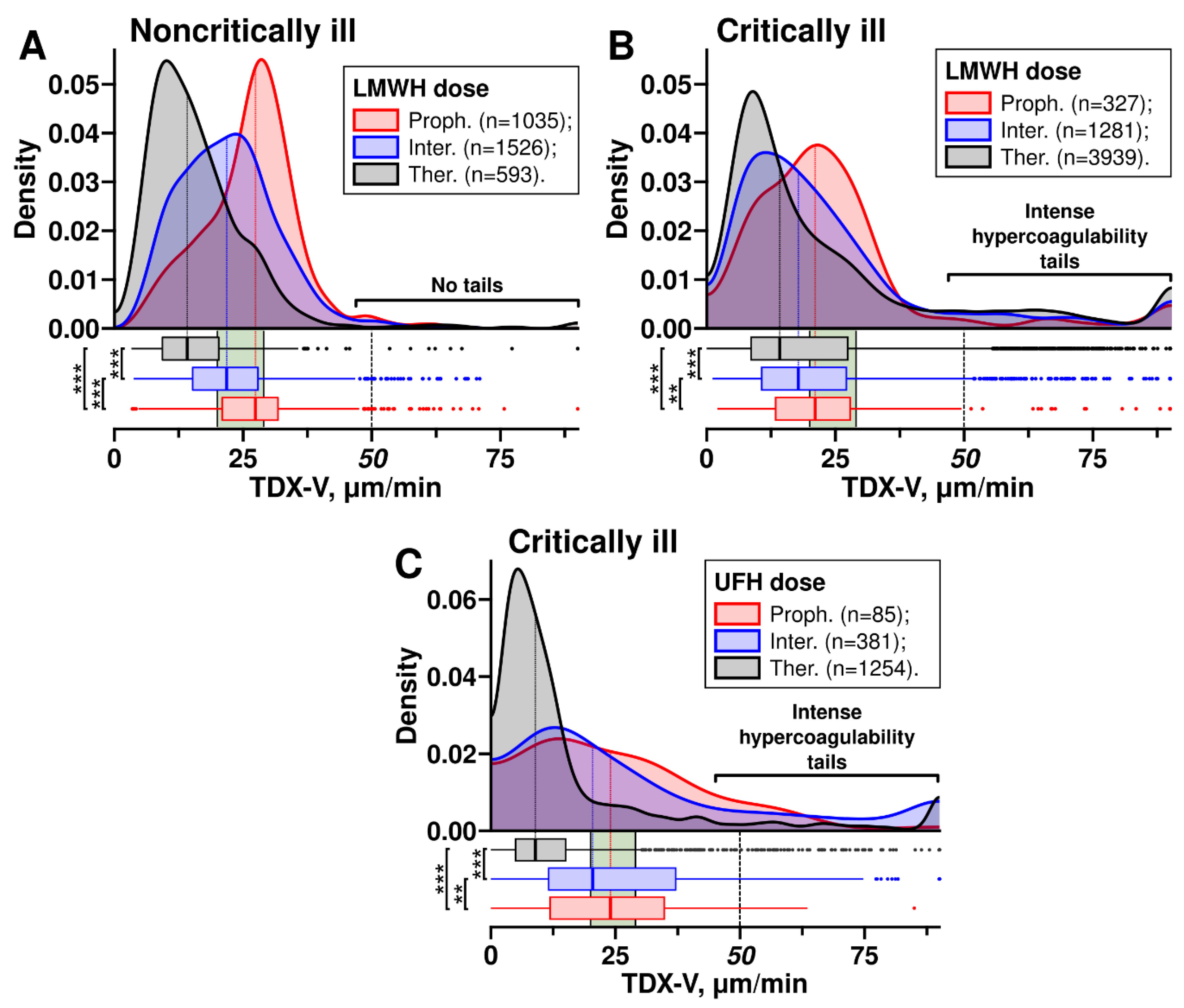

3.2. Escalated Doses of Heparins Did Not Prevent Intense Hypercoagulability in Critically Ill Patients

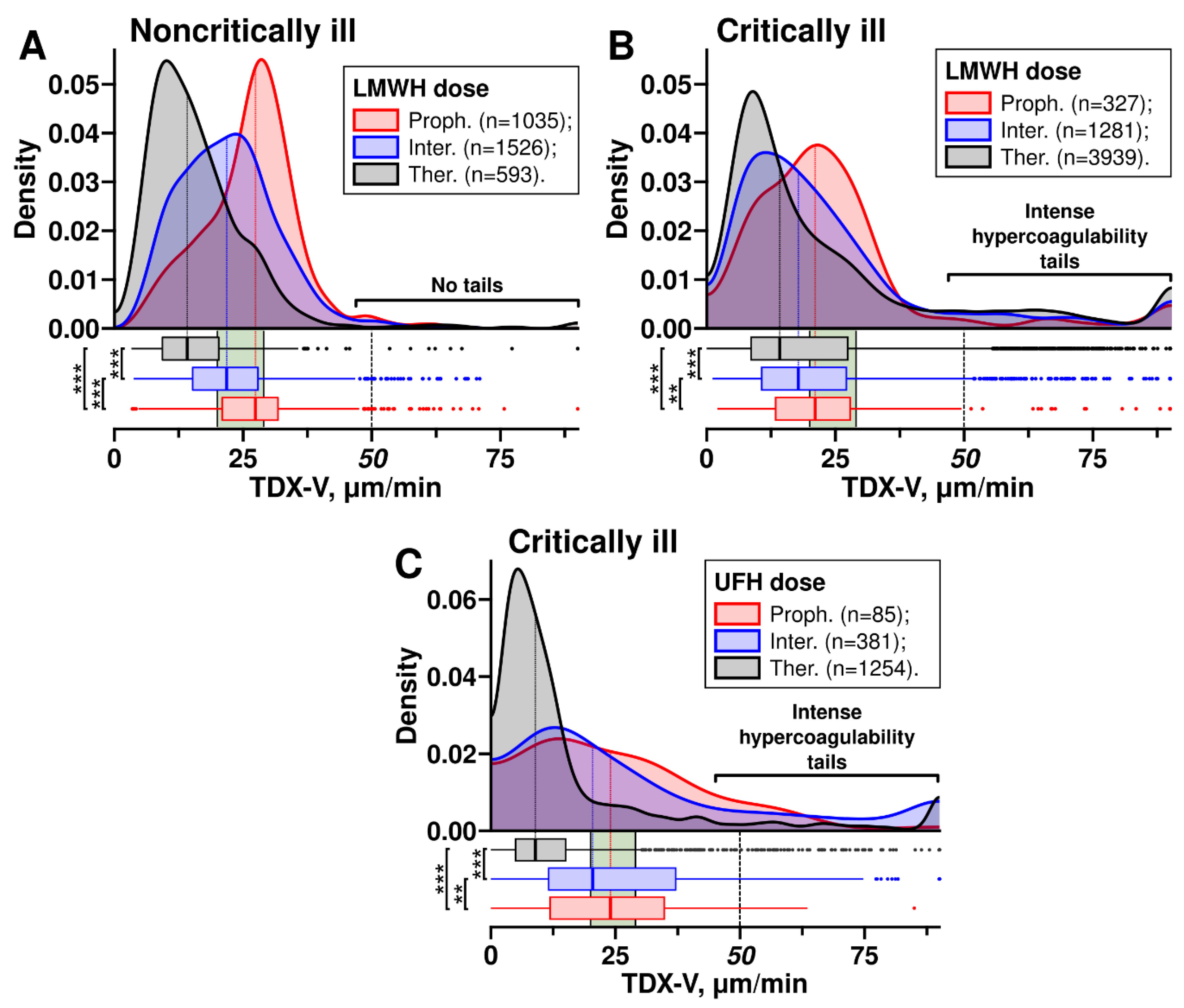

We obtained TDX-V distributions for patients receiving prophylactic, intermediate, and therapeutic doses of heparins (

Figure 3). In both critically ill and noncritically ill patients receiving LMWH, the main peaks and medians of the distributions shifted towards lower TDX-V values as the dose increased (

Figure 3AB). A similar trend was observed with UFH, where higher doses also resulted in a shift of the distributions towards lower TDX-V values (

Figure 3C).

However, the distributions of critically ill and noncritically ill patients receiving LMWH had a notable difference (

Figure 3AB): the distributions of critically ill patients had tails in the range of extremely high clot growth rates (TDX-V ≥50 µm/min). In contrast, the distributions of noncritically ill patients almost lacked such tails. Further, we refer to the range TDX-V ≥50 µm/min as

intense hypercoagulability.

As can be seen form

Figure 3B, these intense hypercoagulability tails did not shift towards lower TDX-V values and their size did not decrease when escalated LMWH were used, suggesting no reduction in the risk of intense hypercoagulability at higher doses. This contrasts with the main peaks of the distributions, which shifted towards lower TDX-V as higher LMWH doses were used. This might suggest that LMHW had a dose-dependent effect on hypercoagulability only when the TDX-V values were below 50 µm/min. In other words, LMWH reduced the risks of hypercoagulability only if it was not intense.

On the other hand, since noncritically ill patients did not have intense hypercoagulability tails, their risk of hypercoagulability decreased when LMWH doses were escalated: the escalation shifted the TDX-V distribution towards lower values.

The distributions of critically ill patients receiving UFH also had intense hypercoagulability tails (

Figure 3C). However, patients receiving UFH via infusion (therapeutic dose) had intense hypercoagulability less often than those receiving prophylactic or intermediate UFH subcutaneously, as can be seen from the sizes of the tails.

In our study 28.3% of critically ill patients had intense hypercoagulability while receiving therapeutic doses of heparins. We investigated whether it arose from some patients with particular clinical profiles. We examined the influence of demographic characteristics on the TDX-V distributions of critically ill patients receiving therapeutic doses of heparins (

Figure S1): the distributions remained almost unchanged, with intense hypercoagulability tails consistently present irrespective of hypertension, diabetes, CCI+CVD, heart failure, coronary artery disease, peripheral atherosclerosis, atrial fibrillation, cancer, sex, or CT score at admission. They also did not depend on age and BMI, although intense hypercoagulability was slightly less pronounced in patients aged 18–44. The distributions were also unaffected by the exclusion of patients transferred from other hospitals from the sample (

Figure S2).

3.3. Intense Hypercoagulability Was Temporary

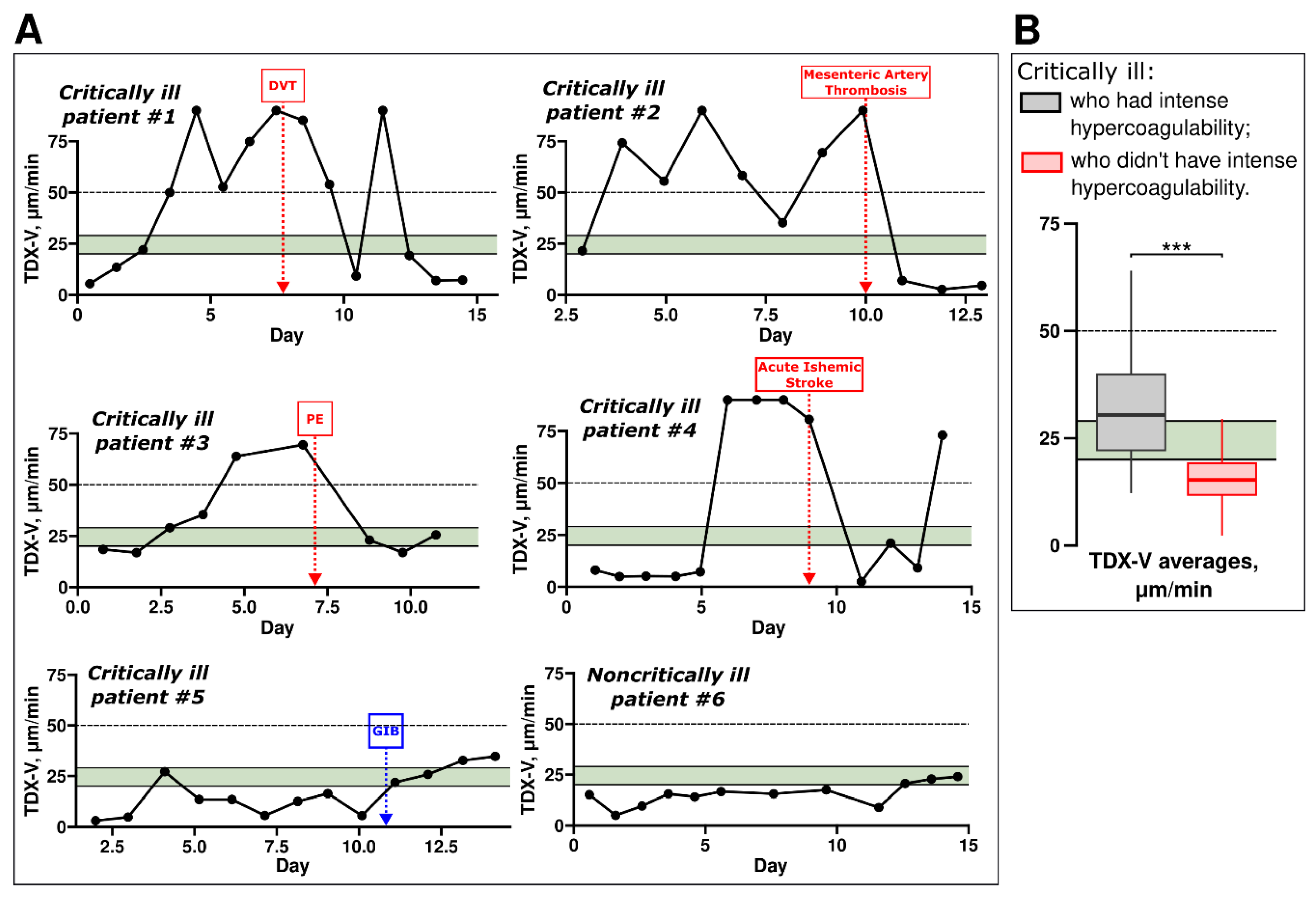

Next, analyzed individual TDX-V time-courses, typical examples are shown in

Figure 4A. The figure shows data from six patients: five critically ill (

#1-5) and one noncritically ill patient (

#6). The coagulation state of critically ill patients often evolved during treatment, sometimes abruptly (

exemplified by patients #1, 2, and 4). Patients

#1-4 also illustrate that intense hypercoagulability was often transient: their TDX-V values were ≥50 µm/min at the certain points of time (e.g., from day 3 to day 10 and on day 12 in

patient #1). During some of these periods thrombotic complications developed in these patients. However, on the other days, these same patients exhibited TDX-V values <50 µm/min, including normal or even hypocoagulable TDX-V values.

In contrast, critically ill patient #5 had more stable coagulation state and did not have intense hypercoagulability. This patient had prolonged hypocoagulability, likely contributing to the development of gastrointestinal bleeding. Noncritically ill patients usually showed little to no variation in their coagulation state throughout hospitalization, as exemplified by patient #6.

Figure 4B shows patients’ TDX-V averages for two groups of critically ill individuals: those who had periods of intense hypercoagulability (

grey box) and those who did not (

red box). Critically ill patients with periods of intense hypercoagulability had higher TDX-V averages compared to those without such periods. However, the TDX-V averages of critically ill patients with periods of intense hypercoagulability were below 50 μm/min (

the grey box is below 50 μm/min). This indicates that, on average, these patients spent a significant portion of their hospitalization time exhibiting coagulation states other than intense hypercoagulability. In other words, intense hypercoagulability was a temporary state for the majority of critically ill patients.

We did not find a correlation between intense hypercoagulability in critically ill patients and low antithrombin III plasma levels – additional examples of TDX-V and antithrombin III levels time-courses are shown in

Figure S3.

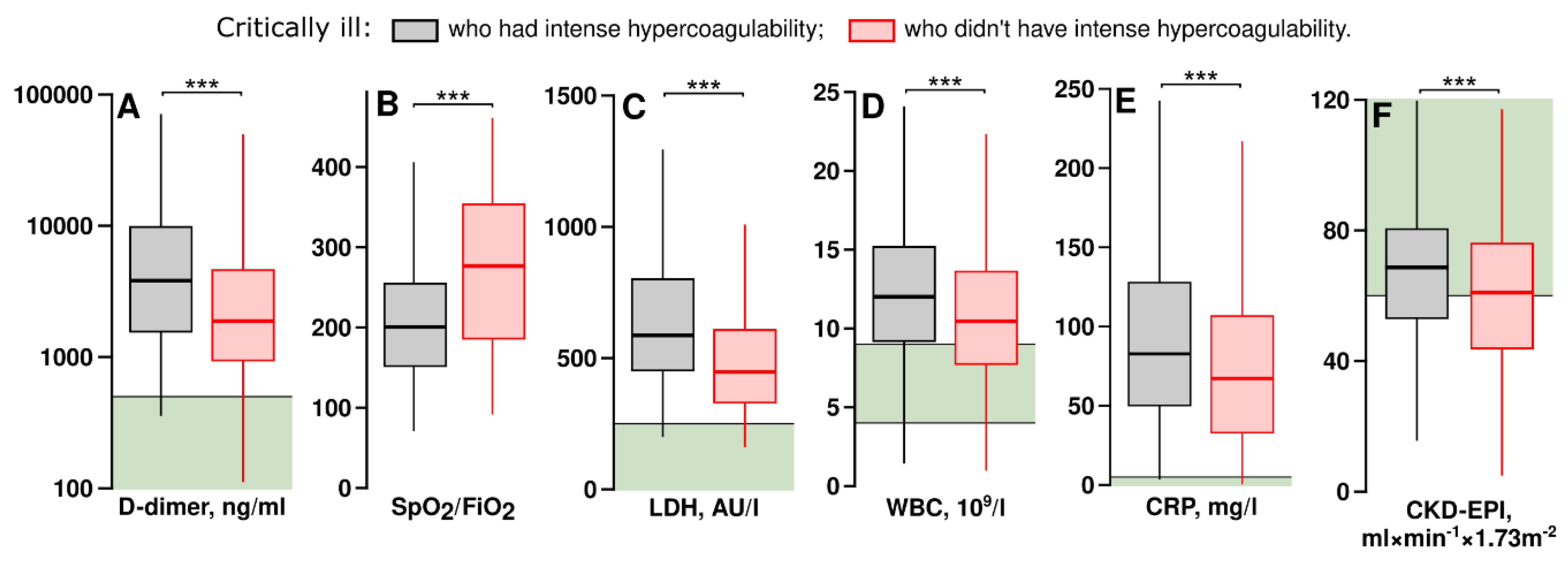

3.4. Critically Ill Patients with Intense Hypercoagulability Had Higher Levels of D-Dimer, Inflammation Markers and Better Glomerular Filtration Rates

We examined which laboratory parameters differed between critically ill patients who had intense hypercoagulability and those who did not have it. The parameters having significant differences are shown in

Figure 5.

Critically ill patients with intense hypercoagulability had higher D-dimer levels, indicating increased thrombosis rates, as well as elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase activity in plasma (LDH), C-reactive protein (CRP), and white blood cell counts (WBC). They also required higher levels of respiratory support. Interestingly, these patients had higher CKD-EPI, which may reflect more efficient clearance of heparins than in patients without hypercoagulability. Similar results were obtained using the Cockroft and Gault formula: according to it, the medians were 91.2 and 83.6 ml×min-1×1.73m-2 in patients with and without intense hypercoagulability respectively (p <0.01).

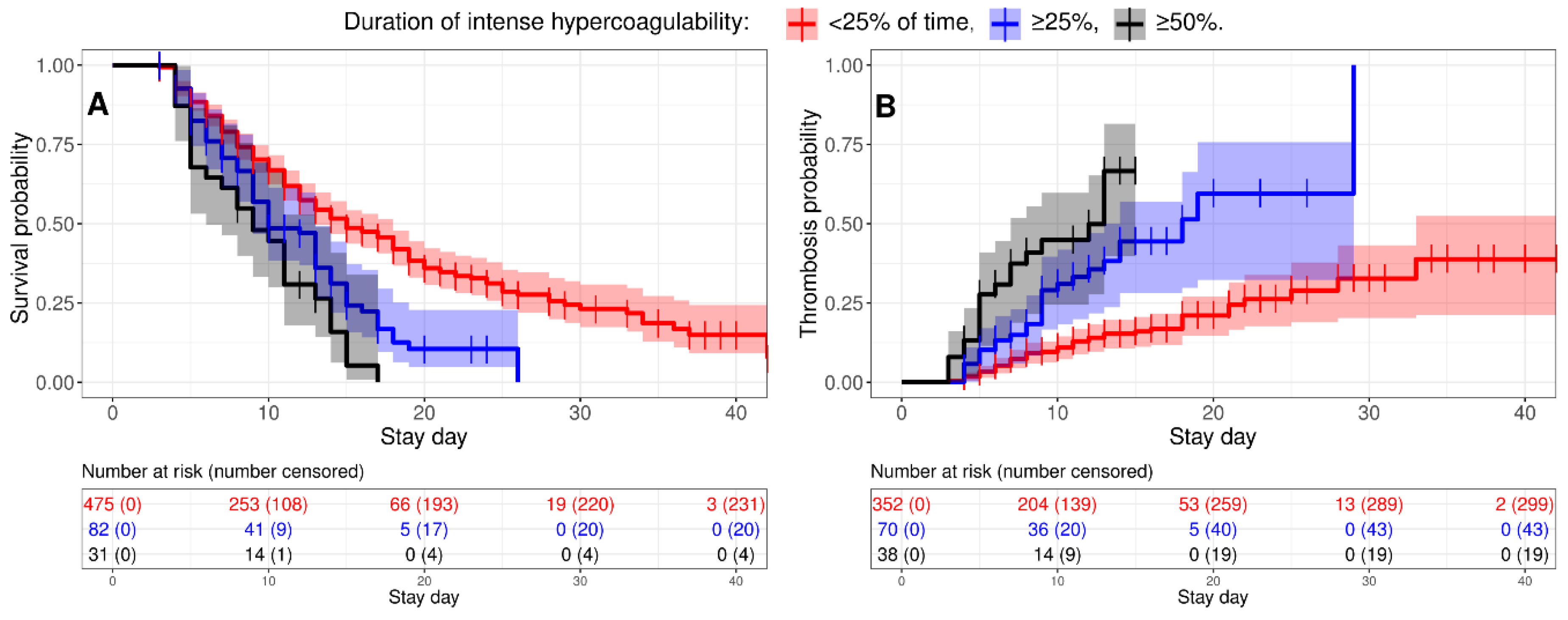

3.5. Intense Hypercoagulability Was a Risk Factor for Thrombosis and Death

We studied how intense hypercoagulability affected the risks of thrombosis and death in critically ill patients. A Kaplan-Meier analysis showed that the more persistent intense hypercoagulability was, the higher the risks of thrombotic complications and mortality (

Figure 6). A Cox regression showed that critically ill patients with intense hypercoagulability faced a 1.75-fold higher hazard rate for death and a 3.19-fold increased hazard rate for thrombosis if intense hypercoagulability persisted for more than 25% of the time prior to the event (

Table 3); these figures doubled if it persisted for more than 50% of the time prior to the event.

We performed similar analyses for D-dimer and APTT. Critically ill patients with elevated D-dimer levels (≥5000 ng/ml) had a 1.43-fold higher hazard rate for death and a 1.90-fold higher hazard rate for thrombosis if intense hypercoagulability persisted for more than 25% of the time prior to the event (

Table S1); these figures doubled if it persisted for more than 50% of the time prior to the event. On the other hand, shortened APTT (≤25.1 sec) was not associated with increased risks of thrombosis or mortality (

Table S1).

We also found that new thrombotic complications were often preceded by high levels of TDX-V and D-dimer (

Figure S4). Meanwhile, APTT was not shortened at these moments.

In our cohort, hypocoagulability preceded new thrombotic complications only in seven patients (8.2%). In three cases, platelet counts exceeded the normal range; in two cases, there was a sharp drop in platelet levels prior to thrombosis. In the remaining two cases, platelet counts were below normal.

3.6. Combining TDX-V and D-Dimer Assays Can Enhance the Accuracy of Predicting Thrombotic Events and Fatal Outcomes

Peak levels of D-dimer and TDX-V could be used to assess the risk of thrombosis: the ROC-AUC for D-dimer and TDX-V levels were 0.710 and 0.709, respectively (

Figure S5). But an index combining both TDX-V and D-dimer had higher ROC-AUC = 0.765. Nadir APTT values had no prognostic value: ROC-AUC = 0.534. Similarly, an index combining both TDX-V values and peak D-dimer levels demonstrated the best prognostic accuracy for predicting lethal outcomes with ROC-AUC = 0.831 (

Figure S6). These findings suggest that taking into account both D-dimer and Thrombodynamics data may provide more accurate assessments of the risks of thrombotic complications and fatal outcomes.

4. Discussion

We examined plasma coagulability in 2206 noncritically ill and 1654 critically ill COVID-19 patients using the APTT, D-dimer, and Thrombodynamics assays. Patients in both groups received prophylactic, intermediate and therapeutic doses of heparins.

4.1. Performance of Various Clotting Assays

We assessed how effectively the Thrombodynamics clot growth rate could be used to evaluate plasma hypercoagulability in COVID-19 patients. Peak TDX-V values had good prognostic accuracy in assessing the risks of thrombotic complications (

Figure S5) and lethal outcomes (

Figure S6). We showed that TDX-V values exceeding 50 µm/min correlated with increased risks of thrombosis and death (

Table 3). This suggests that Thrombodynamics assay accurately detects hypercoagulability in COVID-19 patients.

We evaluated the effectiveness of using D-dimer to assess hemostasis in order to compare its performance with that of TDX-V. We found that elevated D-dimer levels could also indicate high risks of thrombotic complications and fatal outcomes (

Figure S5 and S6, Table S1). The D-dimer results align well with published data [

29]. We also showed that the simultaneous consideration of Thrombodynamics and D-dimer results enhances the accuracy of assessing the risks of thrombosis and fatal outcomes (

Figures S5 and S6).

The D-dimer test has several limitations that must be considered when assessing coagulation. Firstly, elevated D-dimer levels do not necessarily indicate an ongoing risk of thrombotic complications. D-dimer levels rise following thrombus formation and the initiation of fibrinolysis. However, by this point, the patient may have already transitioned out of a hypercoagulable state and thus may no longer be at significant risk for further thrombosis. Secondly, the test cannot guide adjustments to anticoagulation therapy because it lacks sensitivity to hypocoagulable states. Thirdly, its reliability may be compromised in critically ill COVID-19 patients experiencing fibrinolysis shutdown [

30]. Therefore, it is crucial to supplement D-dimer testing with other coagulation assays that do not share these limitations.

APTT is used to monitor heparin therapy and detect deficiencies of coagulation factors. While shortening of the APTT is rare and not typically considered a marker of hypercoagulability, it can be used for this purpose in some cases [

31]. APTT in COVID-19 patients is generally within the normal range or slightly prolonged [

32]. We found that APTT shortening in critically ill patients did not indicate a higher risk of thrombosis (

Figures S4C, S5, and S6); hence it did not detect hypercoagulability. The low performance of APTT in detection of hypercoagulability is most likely associated with the high concentrations of activators used in it. As a result, it is sensitive to factor deficiencies but is poorly suited for detecting hypercoagulability.

4.2. Escalated Doses of Heparins Did Not Prevent Plasma Hypercoagulability in Some Critically Ill Patients

The randomized clinical trials have shown that dose escalation does not reduce mortality in critically ill patients, and its effect on the thrombosis rate is unclear [

3,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. We hypothesized that critically ill patients may experience plasma hypercoagulability even when receiving escalated doses of heparins. We studied the effect of various doses of heparins on plasma coagulability in critically ill and noncritically ill patients using Thrombodynamics assay.

Three key observations were made. Firstly, heparins had a dose-dependent effect on plasma coagulability in both critically ill and noncritically ill patients when TDX-V was below 50 μm/min or UFH infusion was used (

Figure 3).

Secondly, we found that some critically ill patients may exhibit extremely high clot growth rates (TDX-V ≥50 μm/min) at the trough level of pharmacological activity even if doses of LMWH were escalated. Moreover, LMWH did not exert a dose-dependent effect on intense hypercoagulability in critically ill patients. Hence, the risks of thrombosis and death were not reduced in critically ill if they had intense hypercoagulability and received escalated LMWH.

In contrast, noncritically ill patients did not have intense hypercoagulability. Dose escalation shifted their TDX-V distribution towards lower values and, therefore, their risk of hypercoagulability decreased when LMWH doses were escalated. This may explain why escalated doses were effective in noncritically ill patients and ineffective in critically ill patients [

3,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

23,

24].

Thirdly, plasma coagulability in critically ill patients was highly dynamic and the same patient could experience periods of intense hypercoagulability which evolved to other coagulation states (

Figure 4A).

Critically ill COVID-19 patients can experience a strong inflammatory process, which leads to cell-release of procoagulant extracellular vesicles [

33,

34]. This can explain episodes of intense hypercoagulability in critically ill patients with higher levels of CRP, WBC, and LHD (

Figure 5C-E). Another observation was that patients with episodes of intense hypercoagulability had better CKD-EPI (

Figure 5F). This might suggest lower trough pharmacological activity levels of heparins in them, which could allow the development of intense hypercoagulability, even if the patient received escalated doses of anticoagulation. It is possible that more frequent administration of LMWH without daily-dose escalation could be more effective in prevention of intense hypercoagulability.

In our study antithrombin III levels were generally within the normal range and were not associated with episodes of intense hypercoagulability (

Figure S3). Other studies also report almost normal antithrombin III levels [

20,

21]. We suggest that intense hypercoagulability did not result from low antithrombin III levels. Also, intense hypercoagulability was not correlated with transfusions of convalescent or fresh-frozen plasma in our study.

4.3. Study Limitations

The determination of heparin dosing based on patients' medical history and clinical status could introduce bias in our study. We performed the analysis to check whether the group of critically ill patients was homogeneous in terms of Thrombodynamics clot growth rate (

Figures S1 and S2). We found that the group of critically ill patients was homogeneous in terms of TDX-V and intense hypercoagulability did not arise due to presence of some risk factors.

The role of platelets during COVID-19 was actively studied at the beginning of the pandemic [

26,

35,

36,

37]. However, clinical trials have shown that antiplatelet therapy is ineffective during COVID-19 [

2,

3,

4], which suggests a minor role of their hyperreactivity in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Although, in our study 8.2% of venous thrombotic events occurred when TDX-V showed plasma hypocoagulability. Currently, we cannot explain this. Possibly, these events could result from platelet hyperreactivity or thrombocytosis. Hence, platelet activity assays might be necessary to get a full picture of clotting state in COVID-19 patients.

During the study we frequently saw rapid fluctuations in the coagulability state of critically ill patients (

Figure 4). Currently, we do not have an explanation of what can induce these rapid changes.

We decided to consider venous and arterial thromboses together, since TDX-V values were high before both events (

Figure S4A). Our results indicate the average risks for a thrombotic event, which can be either venous or arterial. However, the risks for venous thrombosis can differ from the risks of arterial thrombosis.

Anti-factor Xa activity is generally used to monitor the effectiveness of LMWH thromboprophylaxis, and sometimes to evaluate the risks of thrombotic and hemorrhagic complications. However, its efficacy in evaluation of these risks remains highly controversial [

38,

39]. In this study we did not monitor Anti-factor Xa activity since Thrombodynamics has similar sensitivity to UFH and LMWH [

27].

We were unable to obtain baseline TDX-V values in some patients because they received their first anticoagulation in an ambulance. This practice was introduced midway through our study, yet we had collected a necessary number of measurements by that time. We supposed that these TDX-V values correctly reflected baseline coagulability in the entire cohort. Additionally, some patients had large gaps between TDX-V measurements and were excluded from the TDX-V related analyses. However, these gaps were not associated with illness severity, hence we supposed that it did not affect our results.

Also, the study spanned over a year, encompassing beta, gamma, and delta COVID-19 variants. Additionally, whether these results are valid with the subsequent waves and the current continuous level of COVID-19 episodes is not known.

4.4. Conclusion

Pharmacological effect of LMWH at the trough level might be too low to prevent thrombosis in critically ill patients with severe inflammation and better creatinine clearance even if escalated doses are used. Thrombodynamics assay can reliably detect hypercoagulability in COVID-19 patients. Simultaneous consideration of Thrombodynamics and D-dimer results further enhances the accuracy of assessing the risks of thrombosis and fatal outcomes.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on

Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Study design: F Ataullakhanov, A Rumyantsev, S Shakhidzhanov. Data collection A Filippova, E Bovt, O Dukhin, E Melnikova, S Shakhidzhanov. Data analysis: A Filippova, E Bovt, S Shakhidzhanov. Data interpretation: F Ataullakhanov, A Filippova, E Bovt, D Zateyshchikov, E Vasilieva, S Shakhidzhanov. Resources: I Spiridonov, S Karamzin. Supervision: A Filippova, E Bovt, S Shakhidzhanov. Project administration: F Ataullakhanov, A Filippova, E Bovt, A Gubkin, G Sukhikh, S Tsarenko, A Rumyantsev, D Protsenko, D Zateyshchikov, E Vasilieva, A Kalinskaya, O Dukhin, G Novichkova, I Serebriyskiy, E Lipets, D Kopnenkova, E Melnikova, D Morozova, S Shakhidzhanov. Writing - review & editing: F Ataullakhanov, E Vasilieva, O Dukhin. Writing - original draft: S Shakhidzhanov.

Covitro investigators

6Oleg Abakumov (Supervision); 9Artem Adonin (Data collection); 10Olga An (Data collection); 11Sviatoslav Antipenkov (Data collection); 8Galina Artemyeva (Data collection); 11Akhmadbek Asadov (Data collection); 6Sergei Avdeykin (Supervision); 2Fedor Balabin (Data collection); 2Anna Balandina (Writing - review & editing); 6Zemfira Bekoeva (Supervision); 11Evgeniia Belousova (Data collection); 6Anastasia Berestovskaya (Supervision); 2Efim Bershadskiy (Data collection); 4Olga Beznoshchenko (Data collection); 2Anna Boldova (Data collection); 2Antonina Boldyreva (Data collection); 11Alexander Bovt (Data collection); 11Anna Burova (Data collection); 9Georgiy Bykov (Data collection); 6Andrey Bykov (Supervision); 11Alexey Chernov (Data collection); 11Ivan Chudinov (Data collection); 11Nelli Danchenko (Data collection); 11Elina Dayanova (Data collection); 9Anna Deputatova (Data collection); 2Ivan Dolgikh (Data collection); 11Alena Drobyazko (Data collection); 6Irina Dukhovnaya (Supervision); 11Irina Dzhumaniyazova (Data collection); 11Alexander Efremov (Data collection); 11Olesya Eliseeva (Data collection, Data analysis); 8Antonina Elizarova (Data collection); 11Maria Ershova (Data collection); 11Lyudmila Fedina (Data collection); 11Ivan Fedorov(Data collection); 1,2Olga Fedyanina (Data collection); 11Sofia Galkina (Data collection); 11Anna Gantseva (Data collection); 11Ekaterina Gantseva (Data collection); 2Andrei Kumar Garzon Dasgupta (Data collection); 8Ksenia Glebova (Data collection); 11Anastasia Gorshkova (Data collection); 1Ivan Grebennik (Data collection); 11Ekaterina Harybina (Data collection); 6Nikolai Kadichev (Supervision); 9Timur Kadyrov (Data collection); 2Valeria Kaneva (Data collection); 11Asya Kazantseva (Data collection); 2Roman Kerimov (Data collection); 6Natalia Klimova (Data collection); 1,2Larisa Koleva (Supervision); 1,2Ekaterina Koltsova (Methodology); 2Julia Jessika Korobkina (Data collection); 6Dmitry Kostin (Supervision); 2Tatiana Kovalenko (Data collection); 1,2Ilya Krauz (Data collection, Data analysis, Resources); 4Lubov Krechetova (Supervision); 1,2Anna Kuprash (Data collection); 1,2Nikita Kushnir (Data collection); 1,2Sofya Kuznetsova (Data collection); 11Polina Larionova (Data collection); 6Tatiana Lisun (Supervision); 11Varvara Loginova (Data collection); 11Maria Lyanguzova (Data collection); 11Matvei Maksimov (Data collection); 8Alexandra Maltseva (Data collection); 11Irina Markova (Data collection); 2Michael Martinov (Data collection); 1,2Alexey Martyanov (Data collection, Data analysis, Project administration, Supervision); 2Anastasia Masalceva (Data collection); 6Nikita Matiushkov (Supervision); 11Valeria Mazepa (Data collection); 6Artem Mazhorov (Project administration); 2Andrei Megalinskii (Data collection); 7Larisa Minushkina (Data analysis, Supervision); 6Ayk Mirzoyan (Supervision); 11Daria Mosalskaia (Data collection); 6Sergey Mosin (Supervision); 1,2Vadim Mustyatsa (Data collection); 11Polina Muziukina (Data collection); 11Matvey Nasonov (Data collection); 1,2Dmitry Nechipurenko (Supervision); 11Lidia Nekrasova (Data collection); 1,2Sergey Obydennyj (Data collection); 6Aregnazan Oganesyan (Data collection); 11Anna Ogloblina (Resources); 6Tatyana Padzheva (Supervision); 11Sofia Panafidina (Data collection); 8Diana Pervaya (Data collection); 11Daria Petrova (Data collection); 6Elena Pirozhnikova (Supervision); 12Alexandra Pisaryuk (Data collection, Project administration); 11Daria Pleteneva (Data collection); 11Lilia Pogodina (Data collection); 6Alexander Polyaev (Supervision); 6Ksenia Popova (Supervision); 6Kirill Poshataev (Supervision); 9Egor Pozdnyakov (Data collection); 11Anastasia Prokofieva (Data collection); 1,2Evgeniy Protasov (Data collection); 2Dmitry Prudinnik (Data collection); 4Alexey Pyregov (Supervision); 10Nadezhda Rozhkova (Data collection); 6Mikhail Ryabykin (Supervision); 13Sergey Roumiantsev (Project administration); 11Fatima Sabitova (Data collection); 8Olga Sapozhnikova (Data collection); 11Ivan Sayutkin (Data collection); 1Elena Seregina (Data collection); 6Anatoly Shchuchko (Supervision); 11Zhamilya Shermatova (Data collection); 6Sergei Sidorenko (Supervision); 11Elizaveta Siling (Data collection); 6Kirill Sofronov (Supervision); 6Alexey Sokhlikov (Supervision); 8Denis Sokorev (Data collection); 11Daria Solovyova (Data collection); 2Maria Stepanyan (Data collection, Supervision); 11Alexander Tanas (Data collection); 10Anastasia Tarakanova (Data collection); 6Arsen Tovadov (Supervision); 11Daniya Tuktarova (Data collection); 11Alexandra Valyaeva (Data collection); 11Nikita Vasilenko (Data collection); 9Varvara Vasilevskaya (Data collection); 2Tatiana Vuimo (Data analysis, Supervision); 11Ruslan Yakovlev (Data collection); 11Anna Zakirova (Data collection); 6Alexander Zhukov (Supervision).

9Lomonosov Moscow State University, Physics Faculty, 119991, Moscow, Russia.

10Federal State Autonomous Educational Institution of Higher Education I.M. Sechenov First Moscow State Medical University, 119991, Moscow, Russia.

11Volunteer.

12Vinogradov City Clinical Hospital of Moscow Healthcare Department, 117292, Moscow, Russia.

13Federal State Budgetary Institution of Healthcare Hospital, 108840, Moscow, Troitsk, Russia.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to the patients for their participation in this study. We also extend our thanks to all the medical staff who contributed to this research. We would like to acknowledge Konstantin Severinov for his valuable assistance in recruiting volunteers for this study. This work was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (22-15-00164). It was also generously supported by BostonGene, Rusnano, National Association of Experts in PID (NAEPID), individual sponsor Farid Fatrakhmanov, and contributions from a crowdfunding campaign hosted on planeta.ru.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors and COVITRO investigators have declared no competing financial interests and personal relationships that could have influenced the study.

References

- Klok, F.A.; Kruip, M.J.H.A.; Meer, N.J.M.; van der Arbous, M.S.; Gommers, D.A.M.P.J.; Kant, K.M.; Kaptein, F.H.J.; Paassen J van Stals, M.A.M.; Huisman, M.V.; Endeman, H. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res 2020, 191, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abani, O.; Abbas, A.; Abbas, F.; Abbas, M.; Abbasi, S.; Abbass, H.; Abbott, A.; Abdallah, N.; Abdelaziz, A.; Abdelfattah, M.; Abdelqader, B.; Abdul, B.; Rasheed, A.A.; Abdulakeem, A.; Abdul-Kadir, R.; Abdullah, A.; Abdulmumeen, A.; Abdul-Raheem, R.; Abdulshukkoor, N.; Abdusamad, K.; et al. Aspirin in patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 (RECOVERY): A randomised, controlled, open-label, platform trial. The Lancet 2022, 399, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohula, E.A.; Berg, D.D.; Lopes, M.S.; Connors, J.M.; Babar, I.; Barnett, C.F.; Chaudhry, S.-P.; Chopra, A.; Ginete, W.; Ieong, M.H.; Katz, J.N.; Kim, E.Y.; Kuder, J.F.; Mazza, E.; McLean, D.; Mosier, J.M.; Moskowitz, A.; Murphy, S.A.; O’Donoghue, M.L.; Park, J.-G.; et al. Anticoagulation and Antiplatelet Therapy for Prevention of Venous and Arterial Thrombotic Events in Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: COVID-PACT. Circulation 2022, 146, 1344–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, J.S.; Kornblith, L.Z.; Gong, M.N.; Reynolds, H.R.; Cushman, M.; Cheng, Y.; McVerry, B.J.; Kim, K.S.; Lopes, R.D.; Atassi, B.; Berry, S.; Bochicchio, G.; de Oliveira Antunes, M.; Farkouh, M.E.; Greenstein, Y.; Hade, E.M.; Hudock, K.; Hyzy, R.; Khatri, P.; Kindzelski, A.; et al. Effect of P2Y12 Inhibitors on Survival Free of Organ Support Among Non-Critically Ill Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022, 327, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, H.H.; Reyes-Gil, M.; Szymanski, J.; Ikemura, K.; Stahl, L.R.; Lo, Y.; Rahman, S.; Gonzalez-Lugo, J.D.; Kushnir, M.; Barouqa, M.; Golestaneh, L.; Bellin, E. Anticoagulation in COVID-19: Effect of Enoxaparin, Heparin, and Apixaban on Mortality. Thromb Haemost 2020, 120, 1691–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadkarni, G.N.; Lala, A.; Bagiella, E.; Chang, H.L.; Moreno, P.R.; Pujadas, E.; Arvind, V.; Bose, S.; Charney, A.W.; Chen, M.D.; Cordon-Cardo, C.; Dunn, A.S.; Farkouh, M.E.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Kia, A.; Kohli-Seth, R.; Levin, M.A.; Timsina, P.; Zhao, S.; Fayad, Z.A.; et al. Anticoagulation, Bleeding, Mortality, and Pathology in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020, 76, 1815–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, A.C.; Levy, J.H.; Ageno, W.; Connors, J.M.; Hunt, B.J.; Iba, T.; Levi, M.; Samama, C.M.; Thachil, J.; Giannis, D.; Douketis, J.D. The Subcommittee on Perioperative, Critical Care Thrombosis, Haemostasis of the Scientific, Standardization Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. Scientific and Standardization Committee communication: Clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost 2020, 18, 1859–1865. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, N.; Bai, H.; Chen, X.; Gong, J.; Li, D.; Sun, Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost 2020, 18, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansory, E.M.; Srigunapalan, S.; Lazo-Langner, A. Venous Thromboembolism in Hospitalized Critical and Noncritical COVID-19 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. TH Open 2021, 05, e286–e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maatman, T.K.; Jalali, F.; Feizpour, C.; Douglas, A.I.; McGuire, S.P.; Kinnaman, G.; Hartwell, J.L.; Maatman, B.T.; Kreutz, R.P.; Kapoor, R.; Rahman, O.; Zyromski, N.J.; Meagher, A.D. Routine Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis May Be Inadequate in the Hypercoagulable State of Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019. Crit Care Med 2020, 48, e783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stattin, K.; Lipcsey, M.; Andersson, H.; Pontén, E.; Bülow Anderberg, S.; Gradin, A.; Larsson, A.; Lubenow, N.; von Seth, M.; Rubertsson, S.; Hultström, M.; Frithiof, R. Inadequate prophylactic effect of low-molecular weight heparin in critically ill COVID-19 patients. J Crit Care 2020, 60, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INSPIRATION Investigators. Effect of Intermediate-Dose vs Standard-Dose Prophylactic Anticoagulation on Thrombotic Events, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Treatment, or Mortality Among Patients With COVID-19 Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: The INSPIRATION Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1620–1630. [Google Scholar]

- Therapeutic Anticoagulation with Heparin in Critically Ill Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med Massachusetts Medical Society 2021, 385, 777–789. [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, A.C.; Goldin, M.; Giannis, D.; Diab, W.; Wang, J.; Khanijo, S.; Mignatti, A.; Gianos, E.; Cohen, M.; Sharifova, G.; Lund, J.M.; Tafur, A.; Lewis, P.A.; Cohoon, K.P.; Rahman, H.; Sison, C.P.; Lesser, M.L.; Ochani, K.; Agrawal, N.; Hsia, J.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Therapeutic-Dose Heparin vs Standard Prophylactic or Intermediate-Dose Heparins for Thromboprophylaxis in High-risk Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19: The HEP-COVID Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2021, 181, 1612–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perepu, U.S.; Chambers, I.; Wahab, A.; Ten Eyck, P.; Wu, C.; Dayal, S.; Sutamtewagul, G.; Bailey, S.R.; Rosenstein, L.J.; Lentz, S.R. Standard prophylactic versus intermediate dose enoxaparin in adults with severe COVID-19: A multi-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial. J Thromb Haemost 2021, 19, 2225–2234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blondon, M.; Cereghetti, S.; Pugin, J.; Marti, C.; Darbellay Farhoumand, P.; Reny, J.-L.; Calmy, A.; Combescure, C.; Mazzolai, L.; Pantet, O.; Ltaief, Z.; Méan, M.; Manzocchi Besson, S.; Jeanneret, S.; Stricker, H.; Robert-Ebadi, H.; Fontana, P.; Righini, M.; Casini, A. Therapeutic anticoagulation to prevent thrombosis, coagulopathy, and mortality in severe COVID-19: The Swiss COVID-HEP randomized clinical trial. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2022, 6, e12712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuily, S.; Lefèvre, B.; Sanchez, O.; Empis de Vendin, O.; de Ciancio, G.; Arlet, J.-B.; Khider, L.; Terriat, B.; Greigert, H.; Robert, C.S.; Louis, G.; Trinh-Duc, A.; Rispal, P.; Accassat, S.; Thiery, G.; Montani, D.; Azarian, R.; Meneveau, N.; Soudet, S.; Le Mao, R.; et al. Effect of weight-adjusted intermediate-dose versus fixed-dose prophylactic anticoagulation with low-molecular-weight heparin on venous thromboembolism among noncritically and critically ill patients with COVID-19: The COVI-DOSE trial, a multicenter, randomised, open-label, phase 4 trial. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 60, 102031. [Google Scholar]

- Labbé, V.; Contou, D.; Heming, N.; Megarbane, B.; Razazi, K.; Boissier, F.; Ait-Oufella, H.; Turpin, M.; Carreira, S.; Robert, A.; Monchi, M.; Souweine, B.; Preau, S.; Doyen, D.; Vivier, E.; Zucman, N.; Dres, M.; Fejjal, M.; Noel-Savina, E.; Bachir, M.; et al. Effects of Standard-Dose Prophylactic, High-Dose Prophylactic, and Therapeutic Anticoagulation in Patients With Hypoxemic COVID-19 Pneumonia: The ANTICOVID Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2023, 183, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.A.; Del GIovane, C.; Colombo, R.; Dolci, G.; Arquati, M.; Vicini, R.; Russo, U.; Ruggiero, D.; Coluccio, V.; Taino, A.; Franceschini, E.; Facchinetti, P.; Mighali, P.; Trombetta, L.; Tonelli, F.; Gabiati, C.; Cogliati, C.; D’Amico, R.; Marietta, M.; ETHYCO Study Group. Low-molecular-weight heparin for the prevention of clinical worsening in severe non-critically ill COVID-19 patients: A joint analysis of two randomized controlled trials. Intern Emerg Med 2024, 19, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, D.; Manohar, S.; Goel, G.; Saigal, S.; Pakhare, A.P.; Goyal, A. Adequate Antithrombin III Level Predicts Survival in Severe COVID-19 Pneumonia. Cureus 2021, 13, e18538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Goodspeed, A.; Dronavalli, G.; Zhang, X.; Podbielski, J.M.; Patel, B.; Modis, K.; Cotton, B.A.; Wade, C.E.; Cardenas, J.C. Antithrombin Activity Is Associated with Persistent Thromboinflammation and Mortality in Patients with Severe COVID-19 Illness. Acta Haematol 2023, 146, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuker, A.; Tseng, E.K.; Schünemann, H.J.; Angchaisuksiri, P.; Blair, C.; Dane, K.; DeSancho, M.T.; Diuguid, D.; Griffin, D.O.; Kahn, S.R.; Klok, F.A.; Lee, A.I.; Neumann, I.; Pai, A.; Righini, M.; Sanfilippo, K.M.; Siegal, D.M.; Skara, M.; Terrell, D.R.; Touri, K.; et al. American Society of Hematology living guidelines on the use of anticoagulation for thromboprophylaxis for patients with COVID-19: March 2022 update on the use of anticoagulation in critically ill patients. Blood Adv 2022, 6, 4975–4982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therapeutic Anticoagulation with Heparin in Noncritically Ill Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021, 385, 790–802. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sholzberg, M.; Tang, G.H.; Rahhal, H.; AlHamzah, M.; Kreuziger, L.B.; Áinle, F.N.; Alomran, F.; Alayed, K.; Alsheef, M.; AlSumait, F.; Pompilio, C.E.; Sperlich, C.; Tangri, S.; Tang, T.; Jaksa, P.; Suryanarayan, D.; Almarshoodi, M.; Castellucci, L.A.; James, P.D.; Lillicrap, D.; et al. Effectiveness of therapeutic heparin versus prophylactic heparin on death, mechanical ventilation, or intensive care unit admission in moderately ill patients with covid-19 admitted to hospital: RAPID randomised clinical trial. BMJ 2021, 375, n2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinauridze, E.I.; Vuimo, T.A.; Tarandovskiy, I.D.; Ovsepyan, R.A.; Surov, S.S.; Korotina, N.G.; Serebriyskiy, I.I.; Lutsenko, M.M.; Sokolov, A.L.; Ataullakhanov, F.I. Thrombodynamics, a new global coagulation test: Measurement of heparin efficiency. Talanta 2018, 180, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soshitova, N.P.; Karamzin, S.S.; Balandina, A.N.; Fadeeva, O.A.; Kretchetova, A.V.; Galstian, G.M.; Panteleev, M.A.; Ataullakhanov, F.I. Predicting prothrombotic tendencies in sepsis using spatial clot growth dynamics. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2012, 23, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandina, A.N.; Serebriyskiy, I.I.; Poletaev, A.V.; Polokhov, D.M.; Gracheva, M.A.; Koltsova, E.M.; Vardanyan, D.M.; Taranenko, I.A.; Krylov, A.Y.; Urnova, E.S.; Lobastov, K.V.; Chernyakov, A.V.; Shulutko, E.M.; Momot, A.P.; Shulutko, A.M.; Ataullakhanov, F.I. Thrombodynamics—A new global hemostasis assay for heparin monitoring in patients under the anticoagulant treatment. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0199900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyanov, A.A.; Boldova, A.E.; Stepanyan, M.G.; An, O.I.; Gur’ev, A.S.; Kassina, D.V.; Volkov, A.Y.; Balatskiy, A.V.; Butylin, A.A.; Karamzin, S.S.; Filimonova, E.V.; Tsarenko, S.V.; Roumiantsev, S.A.; Rumyantsev, A.G.; Panteleev, M.A.; Ataullakhanov, F.I.; Sveshnikova, A.N. Longitudinal multiparametric characterization of platelet dysfunction in COVID-19: Effects of disease severity, anticoagulation therapy and inflammatory status. Thromb 2022, 211, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.S.; Kunichoff, D.; Adhikari, S.; Ahuja, T.; Amoroso, N.; Aphinyanaphongs, Y.; Cao, M.; Goldenberg, R.; Hindenburg, A.; Horowitz, J.; Parnia, S.; Petrilli, C.; Reynolds, H.; Simon, E.; Slater, J.; Yaghi, S.; Yuriditsky, E.; Hochman, J.; Horwitz, L.I. Prevalence and Outcomes of D-Dimer Elevation in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2020, 40, 2539–2547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nougier, C.; Benoit, R.; Simon, M.; Desmurs-Clavel, H.; Marcotte, G.; Argaud, L.; David, J.S.; Bonnet, A.; Negrier, C.; Dargaud, Y. Hypofibrinolytic state and high thrombin generation may play a major role in SARS-COV2 associated thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost 2020, 18, 2215–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipets, E.N.; Ataullakhanov, F.I. Global assays of hemostasis in the diagnostics of hypercoagulation and evaluation of thrombosis risk. Thromb J 2015, 13, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connors, J.M.; Levy, J.H. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood 2020, 135, 2033–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, A.; Havervall, S.; von Meijenfeldt, F.; Hisada, Y.; Aguilera, K.; Grover, S.P.; Lisman, T.; Mackman, N.; Thålin, C. Patients With COVID-19 Have Elevated Levels of Circulating Extracellular Vesicle Tissue Factor Activity That Is Associated With Severity and Mortality—Brief Report. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2021, 41, 878–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbi, C.; Burrello, J.; Bolis, S.; Lazzarini, E.; Biemmi, V.; Pianezzi, E.; Burrello, A.; Caporali, E.; Grazioli, L.G.; Martinetti, G.; Fusi-Schmidhauser, T.; Vassalli, G.; Melli, G.; Barile, L. Circulating extracellular vesicles are endowed with enhanced procoagulant activity in SARS-CoV-2 infection. EBioMedicine 2021, 67, 103369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, T.J.; Bilaloglu, S.; Cornwell, M.; Burgess, H.M.; Virginio, V.W.; Drenkova, K.; Ibrahim, H.; Yuriditsky, E.; Aphinyanaphongs, Y.; Lifshitz, M.; Xia Liang, F.; Alejo, J.; Smith, G.; Pittaluga, S.; Rapkiewicz, A.V.; Wang, J.; Iancu-Rubin, C.; Mohr, I.; Ruggles, K.; Stapleford, K.A.; et al. Platelets contribute to disease severity in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost 2021, 19, 3139–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Althaus, K.; Marini, I.; Zlamal, J.; Pelzl, L.; Singh, A.; Häberle, H.; Mehrländer, M.; Hammer, S.; Schulze, H.; Bitzer, M.; Malek, N.; Rath, D.; Bösmüller, H.; Nieswandt, B.; Gawaz, M.; Bakchoul, T.; Rosenberger, P. Antibody-induced procoagulant platelets in severe COVID-19 infection. Blood 2021, 137, 1061–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrottmaier, W.C.; Pirabe, A.; Pereyra, D.; Heber, S.; Hackl, H.; Schmuckenschlager, A.; Brunnthaler, L.; Santol, J.; Kammerer, K.; Oosterlee, J.; Pawelka, E.; Treiber, S.M.; Khan, A.O.; Pugh, M.; Traugott, M.T.; Schörgenhofer, C.; Seitz, T.; Karolyi, M.; Jilma, B.; Rayes, J.; et al. Platelets and Antiplatelet Medication in COVID-19-Related Thrombotic Complications. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahtera, A.; Vaara, S.; Pettilä, V.; Kuitunen, A. Plasma anti-FXa level as a surrogate marker of the adequacy of thromboprophylaxis in critically ill patients: A systematic review. Thromb Res 2016, 139, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibiasi, C.; Gratz, J.; Wiegele, M.; Baierl, A.; Schaden, E. Anti-factor Xa Activity Is Not Associated With Venous Thromboembolism in Critically Ill Patients Receiving Enoxaparin for Thromboprophylaxis: A Retrospective Observational Study. Front Med 2022, 9, 888451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

flow of participants in the study. The study was conducted in seven hospitals. The majority of patients were admitted from home via emergency medical services (ambulance, n=3819), while another group of patients was transferred from other hospitals (n=213). For 172 patients, COVID-19 was not confirmed, and they were excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

flow of participants in the study. The study was conducted in seven hospitals. The majority of patients were admitted from home via emergency medical services (ambulance, n=3819), while another group of patients was transferred from other hospitals (n=213). For 172 patients, COVID-19 was not confirmed, and they were excluded from the study.

Figure 2.

algorithm for the use of LMWH and UFH in the treatment of COVID-19 in adult patients in an inpatient setting. Anticoagulation de-escalation was recommended for patients with kidney injury. It could also be temporarily lowered or discontinued in cases of bleeding, intubation, or surgical intervention.

Figure 2.

algorithm for the use of LMWH and UFH in the treatment of COVID-19 in adult patients in an inpatient setting. Anticoagulation de-escalation was recommended for patients with kidney injury. It could also be temporarily lowered or discontinued in cases of bleeding, intubation, or surgical intervention.

Figure 3.

TDX-V distributions of noncritically ill and critically ill patients receiving different doses of heparins. The distributions show TDX-V values obtained from the second day of hospitalization (because TDX-V values at admission were obtained before a patient was given LMWH or UFH). Patients received prophylactic (Proph.), intermediate (Inter.), or therapeutic (Ther.) doses of heparins. Samples were collected at the trough level of heparins pharmacological activity (excluding UFH infusion, which were collected at least 6 hours after the bolus or the dose adjustment). Boxes under the distributions show their medians and quartiles. Green areas show the normal range (20—29 µm/min). Statistical significance was assessed with the Mann-Whitney U test; levels of significance are shown to the left of the boxes. (AB) – distributions in noncritically ill and critically ill patients receiving different doses of LMWH. (C) – distributions in critically ill patients receiving different doses of UFH. Distributions of noncritically ill patients receiving UFH are not shown due to a small number of cases.

Figure 3.

TDX-V distributions of noncritically ill and critically ill patients receiving different doses of heparins. The distributions show TDX-V values obtained from the second day of hospitalization (because TDX-V values at admission were obtained before a patient was given LMWH or UFH). Patients received prophylactic (Proph.), intermediate (Inter.), or therapeutic (Ther.) doses of heparins. Samples were collected at the trough level of heparins pharmacological activity (excluding UFH infusion, which were collected at least 6 hours after the bolus or the dose adjustment). Boxes under the distributions show their medians and quartiles. Green areas show the normal range (20—29 µm/min). Statistical significance was assessed with the Mann-Whitney U test; levels of significance are shown to the left of the boxes. (AB) – distributions in noncritically ill and critically ill patients receiving different doses of LMWH. (C) – distributions in critically ill patients receiving different doses of UFH. Distributions of noncritically ill patients receiving UFH are not shown due to a small number of cases.

Figure 4.

TDX-V of critically ill patients who experienced intense hypercoagulability. (A) – examples of TDX-V time-courses. Five critically ill (#1–5) and one noncritically ill patient (#6) are shown. Red boxes show the moments at which thrombotic complications were confirmed by instrumental methods. DVT – deep vein thrombosis, PE – pulmonary embolism. Dashed horizontal lines show the lower limit of intense hypercoagulability. Patient #5 had gastrointestinal bleeding on day 11. (B) – TDX-V averages of critically ill patients who had periods of intense hypercoagulability (grey) and those who did not have them (red). Statistical significance was assessed with the Mann-Whitney U test, n = 312 (grey box) and 492 (red box).

Figure 4.

TDX-V of critically ill patients who experienced intense hypercoagulability. (A) – examples of TDX-V time-courses. Five critically ill (#1–5) and one noncritically ill patient (#6) are shown. Red boxes show the moments at which thrombotic complications were confirmed by instrumental methods. DVT – deep vein thrombosis, PE – pulmonary embolism. Dashed horizontal lines show the lower limit of intense hypercoagulability. Patient #5 had gastrointestinal bleeding on day 11. (B) – TDX-V averages of critically ill patients who had periods of intense hypercoagulability (grey) and those who did not have them (red). Statistical significance was assessed with the Mann-Whitney U test, n = 312 (grey box) and 492 (red box).

Figure 5.

laboratory averages of critically ill patients who had intense hypercoagulability and in those without it. Values of critically ill patients receiving therapeutic doses of heparins were analyzed. Black boxes show the averages of critically ill patients who had intense hypercoagulability, red boxes show the averages of critically ill patients without intense hypercoagulability. Green areas show the normal ranges. Statistical significance was assessed with the Mann-Whitney U test. (A) – D-dimer level, the logarithmic scale is used, n=287 (grey box) and 650 (red box). (B) – SpO2 to FiO2 ratio, n=274 (grey box) and 669 (red box). (C) – lactate dehydrogenase activity, n=230 (grey box) and 549 (red box). (D) – white blood cell count, n=298 (grey box) and 735 (red box). (E) – C-reactive protein level, n=298 (grey box) and 735 (red box). (F) – chronic kidney disease-epidemiology collaborative group equation, n=298 (grey box) and 735 (red box).

Figure 5.

laboratory averages of critically ill patients who had intense hypercoagulability and in those without it. Values of critically ill patients receiving therapeutic doses of heparins were analyzed. Black boxes show the averages of critically ill patients who had intense hypercoagulability, red boxes show the averages of critically ill patients without intense hypercoagulability. Green areas show the normal ranges. Statistical significance was assessed with the Mann-Whitney U test. (A) – D-dimer level, the logarithmic scale is used, n=287 (grey box) and 650 (red box). (B) – SpO2 to FiO2 ratio, n=274 (grey box) and 669 (red box). (C) – lactate dehydrogenase activity, n=230 (grey box) and 549 (red box). (D) – white blood cell count, n=298 (grey box) and 735 (red box). (E) – C-reactive protein level, n=298 (grey box) and 735 (red box). (F) – chronic kidney disease-epidemiology collaborative group equation, n=298 (grey box) and 735 (red box).

Figure 6.

intense hypercoagulability increases the risks of death and thrombosis in critically ill patients. Kaplan-Meier curves are shown for survival (A) and thrombosis (B) probabilities in critically ill patients with different durations of intense hypercoagulability (<25% of the time before the event (death in A and thrombosis in B) – red line, ≥25% – blue, and ≥50% – black).

Figure 6.

intense hypercoagulability increases the risks of death and thrombosis in critically ill patients. Kaplan-Meier curves are shown for survival (A) and thrombosis (B) probabilities in critically ill patients with different durations of intense hypercoagulability (<25% of the time before the event (death in A and thrombosis in B) – red line, ≥25% – blue, and ≥50% – black).

Table 1.

patients’ characteristics. CT - computed tomography, CKD-EPI - chronic kidney disease-epidemiology collaborative group equation, CCI+CVD - chronic cerebral ischemia + cerebrovascular disease, ECMO - extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

Table 1.

patients’ characteristics. CT - computed tomography, CKD-EPI - chronic kidney disease-epidemiology collaborative group equation, CCI+CVD - chronic cerebral ischemia + cerebrovascular disease, ECMO - extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

| Variable |

COVID-19 patients |

p-value,

critically ill vs noncritically ill |

Total

(n=3860) |

Critically ill

(n=1654) |

Noncritically ill (n=2206) |

| Death, % (n) |

22.1 (853) |

51.6 (853) |

0 (0) |

<0.0001 |

| Age, median (Q1-Q3) |

64 (54-74) |

68 (58-79) |

62 (51-71) |

<0.0001 |

| Female, % (n) |

51.1 (1974) |

50.5 (835) |

51.6 (1139) |

0.49 |

| Referred from another hospital |

5.4 (210) |

9.9 (164) |

2.1 (46) |

<0.0001 |

Body mass index,

median (Q1-Q3) |

28.5

(25.2-33.1) |

28.8

(25.3-33.7) |

28.3

(25.2-32.3) |

0.06 |

| Length of stay in days, median (Q1-Q3) |

10 (7-15) |

13 (8-20) |

9 (7-12) |

<0.0001 |

| Vitals on admission, median (Q1-Q3) |

| SPO2, % |

94 (92-96) |

93 (90-95) |

94 (93-96) |

<0.0001 |

| Respiratory rate, 1/min |

22 (20-24) |

24 (21-26) |

22 (20-24) |

<0.0001 |

| Systolic pressure, Hg |

130 (117-140) |

129 (115-140) |

130 (119-140) |

0.95 |

| Diastolic pressure, Hg |

80 (70-87) |

78 (70-85) |

80 (70-88) |

<0.0001 |

| Heart rate, 1/min |

91 (81-101) |

92 (82-103) |

91 (81-100) |

0.016 |

| Respiratory support on admission, % (n) |

| ECMO |

0.0 (1) |

0.1 (1) |

0.0 (0) |

- |

| Invasive ventilation |

3.5 (122) |

8.2 (122) |

0.0 (0) |

<0.0001 |

| Non-invasive ventilation |

7.4 (256) |

17.0 (252) |

0.2 (4) |

<0.0001 |

| Nasal oxygen |

41.4 (1432) |

58.6 (871) |

28.4 (561) |

<0.0001 |

| No oxygen therapy |

47.7 (1649) |

16.2 (240) |

71.4 (1409) |

<0.0001 |

| Computer tomography score on admission, % (n) |

| CT0 |

8.1 (311) |

7.4 (123) |

8.5 (188) |

0.23 |

| CT1 |

36.0 (1388) |

23.7 (392) |

45.2 (996) |

<0.0001 |

| CT2 |

28.7 (1107) |

26.0 (429) |

30.8 (678) |

0.001 |

| CT3 |

20.1 (776) |

27.9 (462) |

14.2 (314) |

<0.0001 |

| CT4 |

7.1 (275) |

14.9 (247) |

1.3 (28) |

<0.0001 |

| Continued on next page |

| Laboratory on admission, median (Q1-Q3) |

TDX-V,

20-29 µm/min |

34.8

(29.7-43.8)

n=1370 |

35.3

(29.1-44.6)

n=241 |

34.7

(29.8-43.7)

n=1129 |

0.84 |

TDX-TSP,

>30 min |

21.9

(17.0-26.0)

n=545 |

22.1

(16.4-26.3)

n=103 |

21.9

(17.4-25.9)

n=442 |

0.80 |

D-dimer,

<500 ng/ml |

721

(355-1529)

n=2753 |

1256

(686-2954)

n=1145 |

487

(277-906)

n=1608 |

<0.0001 |

APTT,

25.1-36.5 sec |

30.5

(27.9-33.5)

n=3220 |

30.2

(27.0-33.6)

n=1497 |

30.7

(28.5-33.4)

n=1723 |

0.0002 |

PT,

9.4-12.5 sec |

13.2

(12.2-14.6)

n=3288 |

13.5

(12.4-14.9)

n=1508 |

13.0

(12.0-14.3)

n=1780 |

<0.0001 |

Fibrinogen,

2-4 g/l |

5.6

(4.4-6.9)

n=3074 |

6.0

(4.5-7.4)

n=1441 |

5.3

(4.3-6.6)

n=1633 |

<0.0001 |

Haemoglobin,

120-160 g/l |

136

(124-148)

n=3624 |

134

(119-147)

n=1571 |

138

(127-149)

n=2053 |

<0.0001 |

Platelet count,

180-320×109/l |

202

(156-259)

n=3625 |

191

(146-253)

n=1571 |

207

(165-264)

n=2054 |

<0.0001 |

White blood cell count,

4-9×109/l |

6.4

(4.8-9.2)

n=3624 |

7.6

(5.4-11.4)

n=1571 |

5.8

(4.5-7.8)

n=2053 |

<0.0001 |

Creatinine,

49-104 µmol/l |

95.3

(80.0-114.0)

n=3610 |

99.0

(81.7-123.8)

n=1586 |

93.0

(79.3-110.0)

n=2024 |

<0.0001 |

Glucose,

4.1-5.9 mmol/l |

6.4

(5.5-7.8)

n=3576 |

7.0

(6.0-9.1)

n=1563 |

6.0

(5.3-7.0)

n=2013 |

<0.0001 |

Alanine aminotransferase,

<50 AU/l |

29.4

(19.0-48.0)

n=3581 |

31.0

(20.0-52.0)

n=1573 |

28.0

(18.3-45)

n=2008 |

<0.0001 |

Aspartate aminotransferase,

<50 AU/l |

37.0

(26.3-56.0)

n=3583 |

45.7

(31.0-68.8)

n=1575 |

32.0

(25.0-47.0)

n=2008 |

<0.0001 |

| Continued on next page |

Lactate dehydrogenase,

<250 AU/l |

324.7

(246.4-486.4)

n=1839 |

431.2,

(298.9-610.0)

n=946 |

266.7,

(219.8-344.0)

n=893 |

<0.0001 |

Bilirubin,

5-21 µmol/l |

11.1

(8.2-15.0)

n=3548 |

11.5

(8.4-16.3)

n=1568 |

10.8

(8.1-14.1)

n=1980 |

<0.0001 |

C-reactive protein,

<5 mg/l |

60.4

(21.0-118.9)

n=3609 |

98.8

(41.1-170.1)

n=1579 |

40.1

(14.7-80.6)

n=2030 |

<0.0001 |

CKD-EPI,

>60 ml×min-1×1.73m-2

|

56.8

(43.5-69.4)

n=3606 |

53.4

(38.7-67.1)

n=1584 |

59.3

(47.3-71.1)

n=2022 |

<0.0001 |

| Medication during hospitalisation, % (n) |

| Low molecular weight heparins |

94.2 (3635) |

93.1 (1540) |

95.0 (2095) |

0.72 |

| Unfractionated heparin |

17.9 (691) |

39.4 (652) |

1.8 (39) |

<0.0001 |

| IL6/IL6R blockers |

13.3 (512) |

25.3 (418) |

4.3 (94) |

<0.0001 |

| IL17 blockers |

0.1 (4) |

0.0 (0) |

0.2 (4) |

0.14 |

| JAK inhibitors |

3.2 (125) |

2.4 (39) |

3.9 (86) |

0.008 |

| Steroids |

13.5 (520) |

25.6 (424) |

4.4 (96) |

<0.0001 |

| Antibiotics |

11.3 (437) |

14.8 (244) |

8.7 (193) |

<0.0001 |

| Statins |

10.2 (392) |

14.7 (243) |

6.8 (149) |

<0.0001 |

| Diuretics |

15.3 (592) |

20.6 (341) |

11.4 (251) |

<0.0001 |

| Antiplatelet |

3.8 (147) |

5.6 (93) |

2.4 (54) |

<0.0001 |

| Comorbidities, % (n) |

| Peripheral atherosclerosis |

4.8 (187) |

7.7 (128) |

2.7 (59) |

<0.0001 |

| Coronary artery disease |

18.1 (700) |

27.9 (461) |

10.8 (239) |

<0.0001 |

| Heart failure |

21.9 (844) |

33.1 (548) |

13.4 (296) |

<0.0001 |

| CCI+CVD |

22.2 (856) |

37.2 (615) |

10.9 (241) |

<0.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation |

14.4 (555) |

20.8 (344) |

9.6 (211) |

<0.0001 |

| Hypertension |

62.4 (2410) |

78.1 (1291) |

50.7 (1119) |

<0.0001 |

| Chronic kidney disease |

14.9 (575) |

23.6 (390) |

8.4 (185) |

<0.0001 |

| Diabetes mellitus |

23.4 (905) |

30.8 (509) |

18.0 (396) |

<0.0001 |

| Continued on next page |

| Cancer |

8.6 (333) |

12.0 (198) |

6.1 (135) |

<0.0001 |

| Acute kidney injury |

10.9 (421) |

25.3 (419) |

0.2 (5) |

<0.0001 |

| Complications, % (n) |

| Vein thromboembolism |

|

|

|

|

| Deep vein thrombosis |

10.0 (385) |

20.1 (332) |

2.4 (53) |

<0.0001 |

| Pulmonary embolism |

2.5 (98) |

5.7 (94) |

0.2 (4) |

<0.0001 |

| Superficial vein thrombosis |

2.6 (99) |

5.1 (84) |

0.7 (15) |

<0.0001 |

| Other vein thrombosis#)

|

0.2 (6) |

0.3 (5) |

0.0 (1) |

0.09 |

| Arterial thromboembolism |

|

|

|

|

| Acute ischemic stroke |

0.5 (20) |

1.2 (20) |

0.0 (0) |

<0.0001 |

| Mesenteric artery thrombosis |

0.4 (14) |

0.8 (14) |

0.0 (0) |

<0.0001 |

| Limb artery thrombosis |

0.9 (35) |

1.9 (32) |

0.1 (3) |

<0.0001 |

| Other artery thrombosis##)

|

0.2 (7) |

0.4 (7) |

0.0 (0) |

0.0026 |

Table 2.

proportions of patients with hypercoagulability, normal coagulability, and hypocoagulability at admission and in the following days.

Table 2.

proportions of patients with hypercoagulability, normal coagulability, and hypocoagulability at admission and in the following days.

| Patients |

Time |

% of patients with TDX-V |

n |

>29

µm/min |

20-29

µm/min |

<20

µm/min |

| Critically ill |

At admission#) |

75.6 |

17.3 |

7.1 |

241 |

| By day 2##)

|

28.0 |

18.6 |

53.4 |

724 |

| Average in the next days##)

|

25.3±4.4 |

14.6±1.3 |

60.1±5.4 |

2692 |

| Noncritically ill |

At admission#)

|

79.6 |

14.3 |

6.1 |

1129 |

| By day 2##)

|

25.6 |

32.3 |

42.1 |

726 |

| Average in the next days##)

|

26.8±2.3 |

33.9±5.3 |

39.3±5.9 |

1917 |

Table 3.

Cox regressions for lethal outcomes and thrombotic complications in critically ill patients. HR – hazard ratio, CI – confidence interval, BMI – body mass index.

Table 3.

Cox regressions for lethal outcomes and thrombotic complications in critically ill patients. HR – hazard ratio, CI – confidence interval, BMI – body mass index.

| Model |

N |

Variable |

Base model

HR (95% CI), p-val |

Model adjusted for age, sex and BMI

HR (95% CI), p-val |

| Death |

415 |

Intense

hypercoagulability (IH)#)

|

1.80 (1.46-2.23), *** |

1.75 (1.41-2.16), *** |

| Age |

- |

1.50 (1.29-1.73), *** |

| Male |

- |

1.13 (0.86-1.49), ns |

| BMI |

- |

1.14 (0.99-1.29), ns |

| Thrombosis |

318 |

Intense

hypercoagulability (IH) #)

|

3.16 (2.29-4.37), *** |

3.19 (2.31-4.41), *** |

| Age |

- |

0.94 (0.71-1.25), ns |

| Male |

- |

1.05 (0.62-1.77), ns |

| BMI |

- |

0.94 (0.71-1.26), ns |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).