1. Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the human coronavirus recognized as the cause of COVID-19. At first detected in China (December 2019), the disease has rapidly spread worldwide, resulting in a global pandemic. COVID-19 clinical symptoms include fever, dry cough, sore throat, dyspnea, headache, severe asthenia, and interstitial pneumonia, which can potentially progress to alveolar damage and consequent respiratory failure [i,ii].

The high mortality rate associated with COVID-19 is not only due to viral replication in lung epithelial cells but is also driven by a dysregulated host immune response defined as ‘cytokine storm syndrome’ [iii]. COVID-19 infection increases the risk of arterial and venous thrombosis, which led to considerable interest in antithrombotic treatment to prevent and treat these COVID-19-related complications [iv]. In this context, some attention has been paid to the repurposing for COVID-19 therapy of serine protease inhibitors, including some direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs), such as the factor Xa-selective inhibitors otamixaban [v] and a newly synthesized guanidino-containing isonipecotamide derivative, besides the thrombin-selective inhibitor nafamostat [vi], the aim being to identify molecules capable of acting both at the level of virus entry (i.e., blocking the protease activation of the Spike protein by inhibiting TMPRSS2 transmembrane serine protease 2) and the downstream thrombotic complications.

An increasing number of studies has shown abnormal serum coagulation parameters in hospitalized patients with severe forms of COVID-19 with a trend toward hypercoagulable state, which may result in the high prevalence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) especially in non-typical locations, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and ARDS [

vii]. In addition, endothelial injury causing microvascular pulmonary thrombosis is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with interstitial pneumonia [

viii]. Despite the fast-growing understanding of the clinical features and natural history of infection, COVID-19 still remains a partially unmet clinical need [

ix,

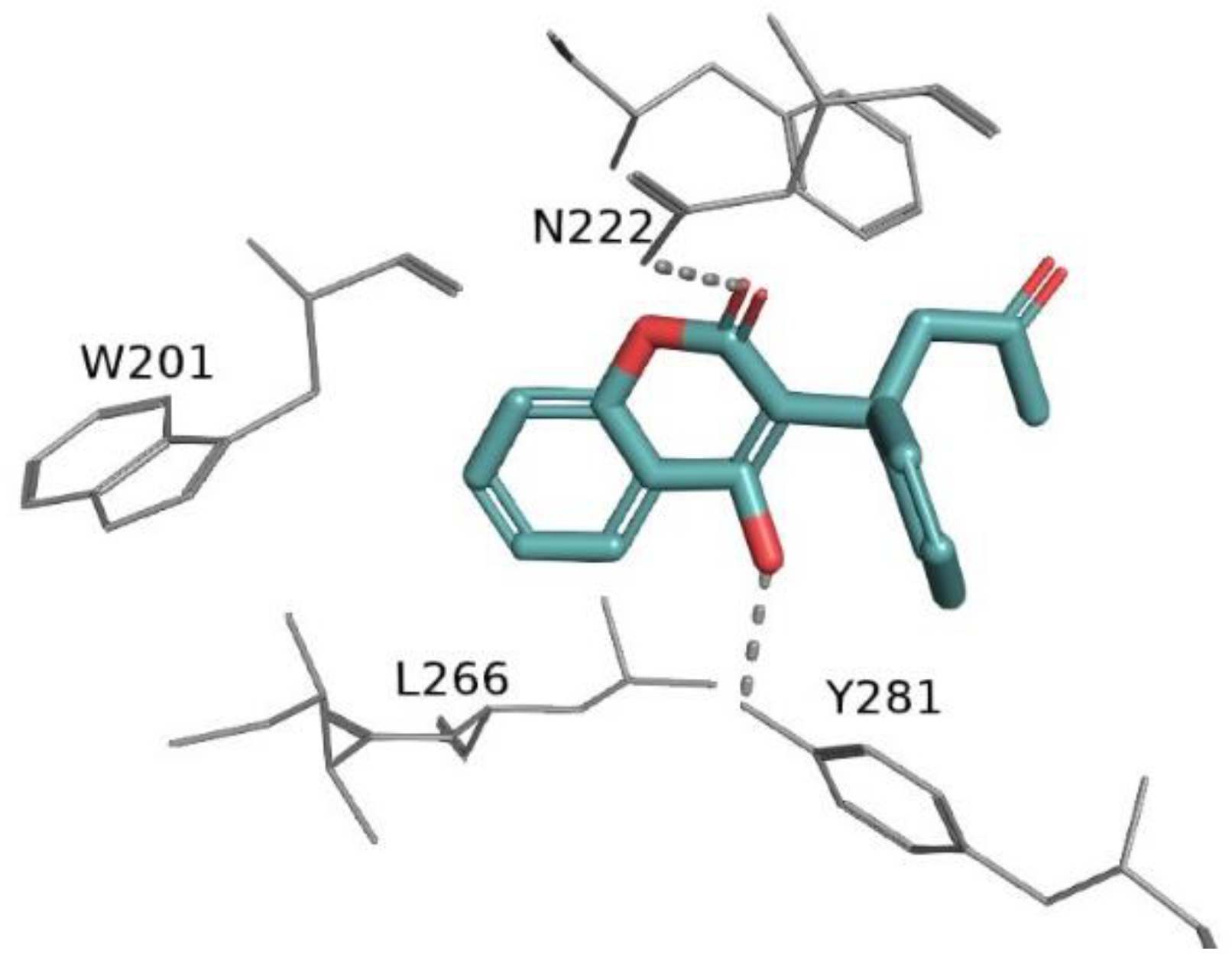

x]. The high risk of COVID-19-associated thrombotic events and the related role of anticoagulants is one of the unresolved issues. Anticoagulant drugs, such as heparins, vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) and, more recently, direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs), are utilized in the management of thrombotic disorders. VKAs, such as warfarin, were the preferred anticoagulant agents before the approval of DOACs. Warfarin inhibits the vitamin K epoxide reductase complex 1 (VKORC1,

Figure 1), thereby blocking the synthesis of clotting factors.

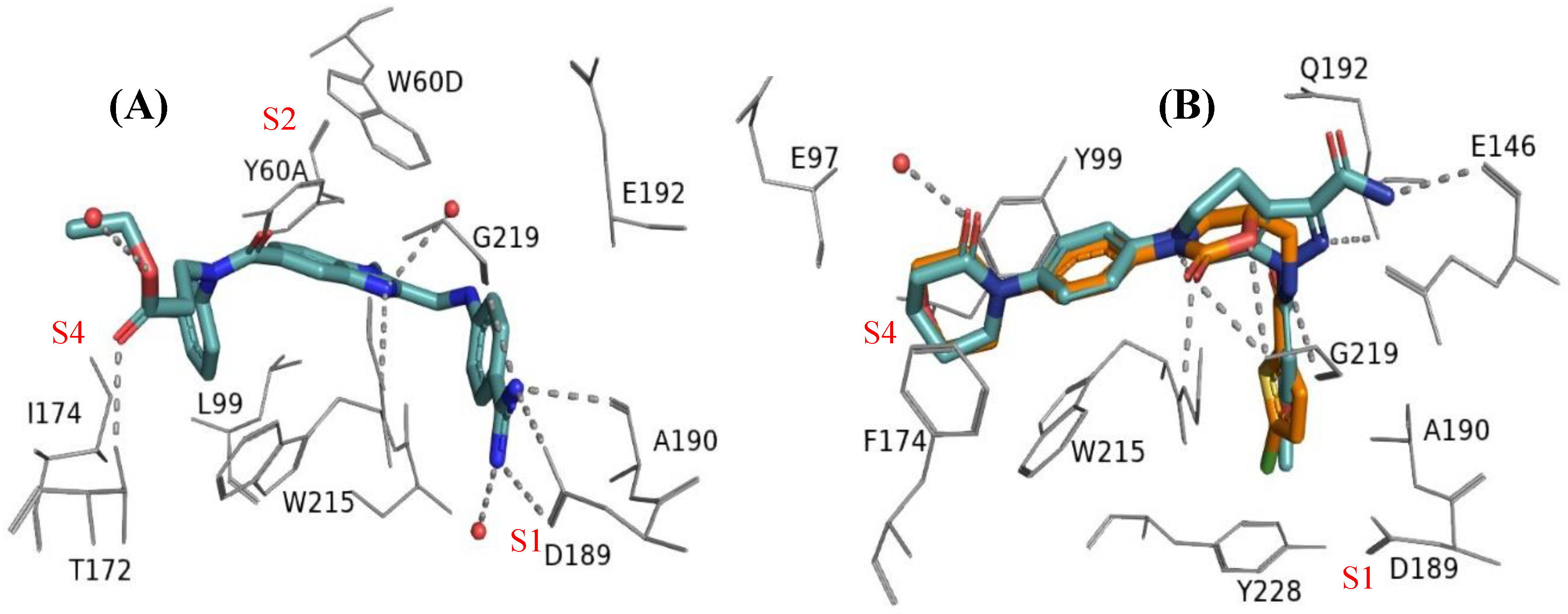

DOACs proved to be more effective and safer than warfarin. They act as selective inhibitors of thrombin (thr, e.g. dabigatran;

Figure 2A) or activated factor X (fXa, e.g. apixaban and rivaroxaban;

Figure 2B) in the blood coagulation cascade. DOACs offer several advantages over warfarin, such as rapid onset, short duration of action, and reversible binding to their targets. Additionally, they simplify clinical management, by reducing food- and drug-drug interactions, frequency of monitoring, and risk of bleeding [

xi,

xii]. Accordingly, their effectiveness in preventing and treating thromboembolic events has been well-established across a range of clinical settings.

Given that early endothelial injury leading to microvascular pulmonary thrombosis could possibly be associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with respiratory failure caused by interstitial pneumonia, the hypothesis was put forward that COVID-19 patients on anticoagulant therapy at the time of the infection might be protected from adverse outcomes as compared to non-treated patients. In October 2021, the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) convened an international panel of experts, along with representatives from patient communities and methodologists. The objective was to formulate evidence-based recommendations concerning the use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents for patients diagnosed with COVID-19 across various clinical contexts [xiii].

Despite the plethora of studies on the management of COVID-19 that had been published, a substantial uncertainty persists regarding the use of anticoagulants for the prevention and treatment of thromboembolic events in hospitalized patients with COVID-19, also in terms of drugs and dosages for different patient populations. In this context, some studies focused on patients already on oral anticoagulant therapy (OAT) when diagnosed with COVID-19, based on the hypothesis that they could be at lower risk of adverse outcomes. A large randomized controlled trial found that treatment with anticoagulants reduced the risk of death in patients with COVID-19 who were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) [xiv]. However, controversial results on the role of OAT on diverse clinical outcomes of COVID-19 patients were reported. Some studies showed that prior use of therapeutic anticoagulation did not improve survival in hospitalized COVID-19 patients and that similar outcomes were observed both for patients treated with VKAs or DOACs [xv,xvi]. In contrast, a retrospective cohort study reported that COVID-19 patients on OAT at the time of infection and during the disease showed significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality at 21 days [xvii]. Another study reported that, among elderly patients hospitalized for COVID-19, OAT had a significantly lower mortality rate than patients not receiving anticoagulation [xviii,xix]. A retrospective observational study from CORIST registry also showed that OACs might have protective effects on adverse COVID-19 outcomes in hospitalized patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) and that fewer adverse events occurred in patients on therapy with DOACs compared to patients on therapy with VKAs [xx]. Interestingly, another study reported that high-risk AF patients on OAT had a lower risk of receiving a positive COVID-19 test and severe COVID-19 outcomes [xxi].

In the light of the above considerations, a major purpose of this retrospective study is to assess whether the OAT (with either DOACs or VKAs) could impact on medium-term mortality of COVID-19 patients. To this end a cohort of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 during pandemic was analyzed, focusing on association of OAT with patients’ characteristics, disease severity, comorbidities and co-medications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

This observational matched cohort study was conducted in the Regional General Hospital "F. Miulli" in Acquaviva delle Fonti, Bari, Italy, a 600-bed referral center that dedicated up to 300 beds to COVID-19 patients during pandemic emergency from March 17, 2020 to June 15, 2021. The primary endpoint of this study was the mortality at 90-day in patients admitted for COVID-19. For patients residing in Puglia, deaths occurring after hospital discharge were detected by the regional health information system. Among 1253 patients admitted for COVID-19, 1211 were evaluated for this study after the exclusion of those resident in other regions.

Because several baseline variables were different between survivors and non-survivors, we matched the two cohorts (247 survivors and 247 deceased within 90 days from hospitalization) using an automated procedure to select similar patients 1:1 according to gender, age (difference lower than 5 years), admission (difference up to 30 days) and intensive care needs within three days since admission. The following data of selected patients were collected: demographic information (age, gender), clinical symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, comorbidities, vital signs, pharmacological treatments (before and during hospitalization), in-hospital course (admission in intensive care unit and respiratory support measures), complications (ARDS at admission or developed during hospitalization) and mortality, and laboratory tests. All data are recorded on an electronic datasheet.

This study was approved by the institutional review board (#7780, Independent ethical committee – Policlinico of Bari, Italy) and conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All the data of interest were collected by consulting the patients' medical records. The study population was divided according to mortality at 90 days to detect potential protective effects of the use of OACs on that endpoint.

2.2. Statistical Analysis

Data are reported as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or percentage for categorical variables. Data of the paired patients were compared with a dependent samples t-test (continuous variables) and McNemar's test (dichotomous information). A conditional logistic regression model, appropriate for matched data, was used to compare data of paired patients. Odds Ratios (ORs) with 95% Confidence Interval (95% CI) were estimated. All analyses were conducted using STATA software, version 16 (Stata-Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 494 patients were matched 1:1 according to mortality at 90 days since hospital admission, as 247 survivors and 247 non-survivors. In

Table 1 patients’ characteristics (i.e., demographics, comorbidities, pharmacotherapies) at hospital admission are summarized. Groups were similar in terms of matching criteria: age (77±10 years), gender (141 men and 106 women) and ICU admission within 3 days (25 patients in each cohort). Mortality at 90-day was associated with higher prevalence of arteriopathy, history of heart failure (HF), cancer, respiratory diseases, atrial fibrillation and kidney failure (

Table 1).

Compared to patients living at 90 days, those with fatal event achieved more frequently HF (23.1% vs 10.5%; p < 0.001), AF (22.3% vs 13.4%; p = 0.009), as well as arteriopathy, cancer, asthma or COPD, and renal insufficiency. Regarding pre-admission pharmacotherapies, neither DOACs nor warfarin, and heparins as well, seem to provide statistically significant beneficial effects (p > 0.05). With a few exceptions (ACE inhibitors, antidiabetics and statins), no pharmacological treatment showed favorable trend (i.e., higher frequency in survivors), whereas patients treated with aldosterone antagonists were significantly more frequent (p < 0.001) in non-survivors (30.0% vs 13.8%).

As summarized in

Table 2, clinical features of dead patients within 90 days since admission, especially those related to respiratory parameters at admission and respiratory supports, were worse than those of survivors.

As far as the pharmacological treatments are concerned, the data related to the broad—spectrum antiviral remdesivir and the HIV-targeted antiretroviral lopinavir, repurposed against SARS-CoV-2, are too few for drawing conclusions, despite some trends. The same applies to the old antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine (often administered in combination with the macrolide antibiotic azithromycin), supposed able to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection during the first phase of pandemics, and later proven to lack clinical benefit for COVID-19 [xxii,xxiii]. Indeed, despite the statistical significance (p = 0.007) of the difference between the survivors’ group (9.7% frequency) and non-survivors (5.3% frequency), the evidence remains inconclusive. A favorable trend might be deduced for azithromycin.

Subjects treated with subcutaneous low-molecular weight heparins (LMWHs) did not experience any significant beneficial effect in terms of 90-day mortality. In contrast, among non-survivors, patients treated with unfractioned heparins (HMWHs) are twice as many as those found among survivors. At admission, patients in OAT were 60 (24.3%) in the group of survivors (21 in the DOAC group and 12 in the VKA (warfarin) group; 27 started OAT during hospitalization) and 69 (27.9%) in deceased patients (25 in the DOAC group and 13 in the VKA group; 31 started OAT during hospitalization). No significant difference (p > 0.005) in frequency of patients in OAT was observed between survivors and dead patients. No other pharmacological treatment proved to significantly affect the medium-term mortality, except for patients treated with vitamin D. Interestingly, Vitamin D—treated patients populated the group of survivors (42.9%) much more (p < 0.001) than the group of non-survivors (27.9%).

As shown in

Table 3, that summarizes clinical parameters at admission, deceased patients were characterized by higher levels of azotemia, serum lactate dehydrogenase and C-reactive protein. Importantly, IL-6 and procalcitonin, markers of a severe infection in progress, and D-dimers, markers of deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism as well as inflammation and infection, were higher in non-survivors compared to survivors. According to previous studies [i,ii], albumin levels and various parameters from blood count analysis were altered in non-survivors (

Table S1 in

Supplementary Materials).

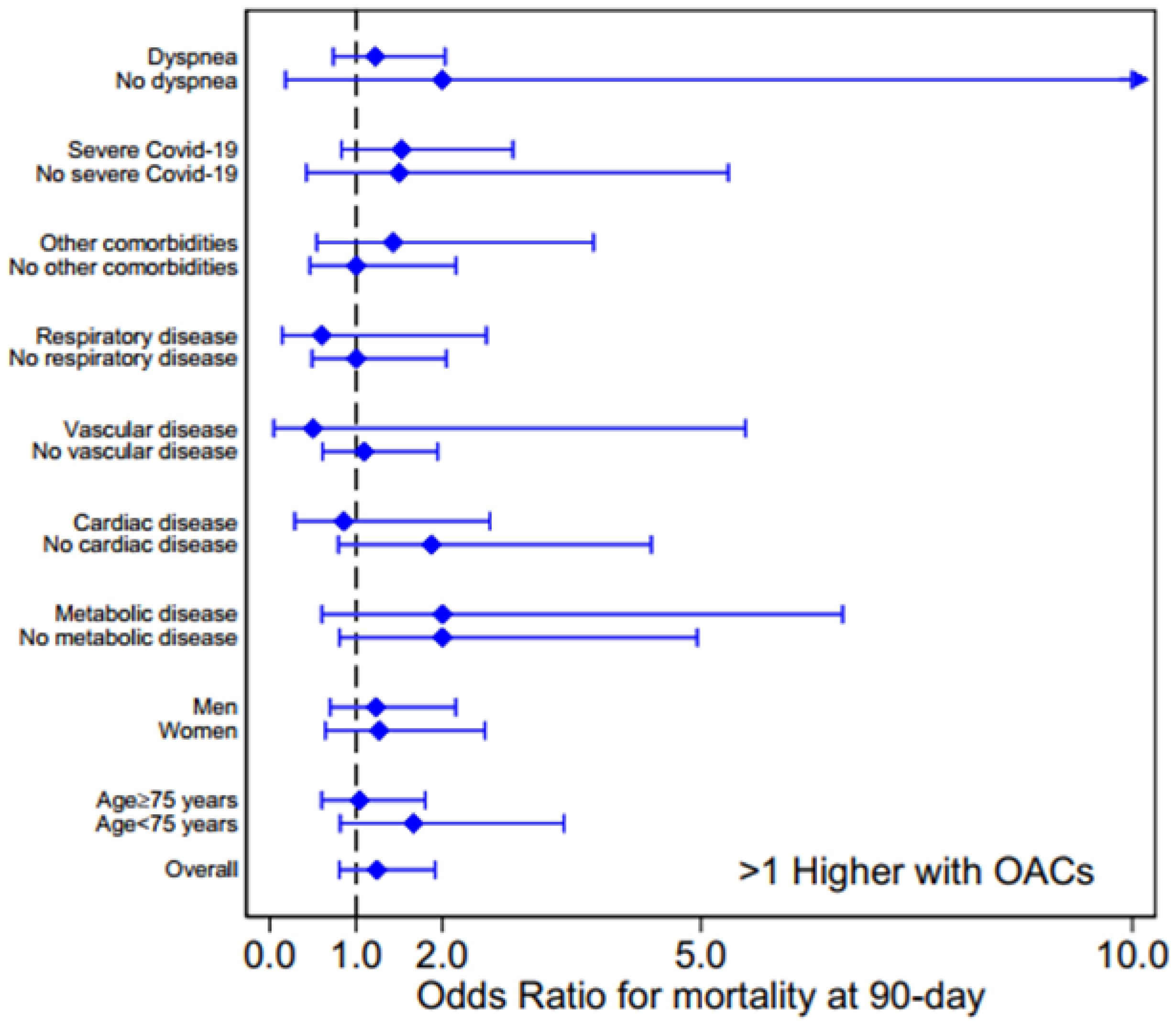

To investigate into the association between OAT (including warfarin as VKA and the DOACs apixaban and edoxaban) and mortality at 90 days, we calculated the Odds Ratios (ORs) for the survivors’ and non-survivors’ subgroups encompassing age, gender, comorbidities,

clinical and respiratory parameters at admission,

pharmacotherapies (data in Table 1 and

Table 2, according to presence/absence of a categorical factor or by values above/below median for continuous data

). The ORs for age, gender, comorbidities and COVID-19 severity are shown in Figure 3, whereas the OR subgroup analysis of laboratory parameters and pharmacological therapies, and for clinical and respiratory parameters at admission, are reported in Figures S1 and S2, respectively, in Supp. Materials.

Figure 3 shows that there is no association between OAT (DOACs or VKA) and mortality, the OR values being higher than 1, with a large 95% confidence interval, for several conditions (overall OR = 1.24, 95% confidence intervals 0.81-1.92,

p = 0.324). Moreover, for each analyzed characteristic and clinical parameter, no difference in OAC prevalence was observed between survivors and dead patients.

4. Discussion

The main statistically significant outcomes of this retrospective clinical study could be the following: (i) among the cardiovascular comorbidities, HF and AF proved to have the highest negative impact on medium-term mortality of COVID-19 patients; (ii) OAT (both DOACs and VKAs), either before and during hospitalization, was found to be not significantly associated to beneficial effects; (iii) the use of canrenone, as mineralcorticoid receptor antagonist in antihypertensive therapy, appeared to worsen the clinical course of COVID-19 patients, whereas (iv) vitamin D supplementation appears to have beneficial effects.

4.1. Comorbidities Influencing COVID-19-Related Mortality

As it has been widely demonstrated, the presence of certain comorbidities and complications significantly impacts the survival rates of COVID-19 patients [xxiv,xxv,xxvi]. Therefore, dissecting the intricate relationship between various comorbidities and COVID-19 outcomes can pave the way for developing improved clinical strategies and therapeutic protocols, potentially mitigating the impact of the disease.

According to the established impact of cardiovascular diseases [xxvii], representing a multiplier of the risk of death in the event of SARS-CoV-2 infection, in our retrospective study, HF and AF, characterized by a pro-thrombotic state that frequently complicate each other, are among the cardiovascular comorbidities mainly linked to medium-term mortality of COVID-19 patients. As widely reported, thromboembolic complications result in death increase in COVID-19 patients. The high level of D-dimers, indicating an increased hypercoagulation, together with elevated levels of IL-6 and CRP, indicating sustained inflammation, are associated with an increase of infection, sepsis and mortality in COVID-19 patients [xxxvii,xxviii]. In our study, D-dimers, IL-6, procalcitonin and CRP were found to be higher in non-survivors compared with surviving patients, which could highlight the effect of increased inflammation and thromboembolic complications on medium-term mortality of COVID-19 patients.

Compared to patients living at 90 days, those who suffer fatal events achieved more frequently respiratory disease or COPD. Indeed, respiratory impairment has a significant impact on mortality as indicated by the respiratory insufficiency, dyspnea and high values of positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) significantly characterizing the population of non-survivors with respect to survivors.

4.2. Impact of Oral Anticoagulation Therapy on COVID-19 Clinical Course

The main purpose of this study was to investigate the eventual association between OAT and mortality in COVID-19 patients. An increased number of studies have shown abnormal serum coagulation parameters in hospitalized patients with severe forms of COVID-19 with a trend toward hypercoagulable state [xxix,xxx,xxxi]. Thus, during the pandemic, anticoagulation treatment has been considered a pharmacological strategy to reduce the risk of mortality in patients affected by severe form of COVID-19 [xxxii,xxxiii]. However, the true benefit of OAT on clinical outcome of hospitalized patients is still debated.

In our patients’ cohort, OAT with either DOACs or VKAs before and during hospitalization, proved to not exert any beneficial effect on mortality within 90 days since SARS-CoV-2 infection. Our findings are consistent with those reported in previous observational studies and meta-analysis which showed no significant lower mortality in COVID-19 patients in OAT [xxxiv,xxxv,xxxiii]. Although the mechanisms underlying SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis are not yet completely understood, the interplay between inflammation and coagulation should have a pivotal role. Indeed, the severe inflammatory response and disseminated intravascular coagulation together with virus-induced local inflammatory reactions may affect endothelial cell function leading to vessel wall damage and consequent microvascular thrombosis [iii,xxxvi,xxxvii]. Some authors hypothesized that microvascular pulmonary thrombosis in COVID-19-induced pneumonia is sustained by a complex interplay between clotting system activation and immune-mediated inflammatory response [xxxviii,xxxix]. Based on this mechanism, which involves two processes mutually reinforcing each other, it might be argued that, as likely occurred in the cohort of COVID-19 patients under investigation, OAT, by targeting one single pathway, cannot favorably affect the progression of SARS-CoV-2 infection and the natural history of the disease.

Another explanation of the lacking association between OAT and beneficial effect on mortality could be derived from the current view regarding the mechanisms responsible for COVID-19-associated coagulopathy in which fibrin is considered as a key driver of thromboinflammation [xl]. Indeed, very recently, it has been demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 spike protein interacts with fibrinogen, promoting fibrin polymerization and ultimately triggering its thromboinflammatory activity [xli]. In this light, we can postulate that, despite OAT, blood clots in the COVID-19 patients’ cohort remain resistant to degradation, since hypercoagulation state is mainly due to elevated plasma fibrinogen, as on the other hand supported by the elevated D-dimer levels in non-survivors. Interestingly, a fibrin-target immunotherapy is currently proposed for patients with acute and long COVID-19 [xl].

4.3. Impact of Other Pharmacological Treatments on COVID-19 Mortality

As highlighted above, the use of the aldosterone antagonist canrenone, i.e., the active metabolite of spironolactone, in the form of canrenoic acid or potassium canrenoate, appeared to worsen the clinical course of the investigated COVID-19 patients’ cohort. This was somehow surprising, due to the potential of MRAs to prevent aldosterone from causing fibrosis and inflammation. Indeed, it has been reported that aldosterone levels increase in COVID-19 patients and some studies demonstrated that the treatment with MRAs have an overall positive impact on clinical improvement and all-cause mortality [xlii,xliii,xliv]. However, systemic review and meta-analysis did not establish a significant association between MRA therapy and mortality in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 [xlv], and the effect of canrenone in COVID-19 patients remains still uncertain.

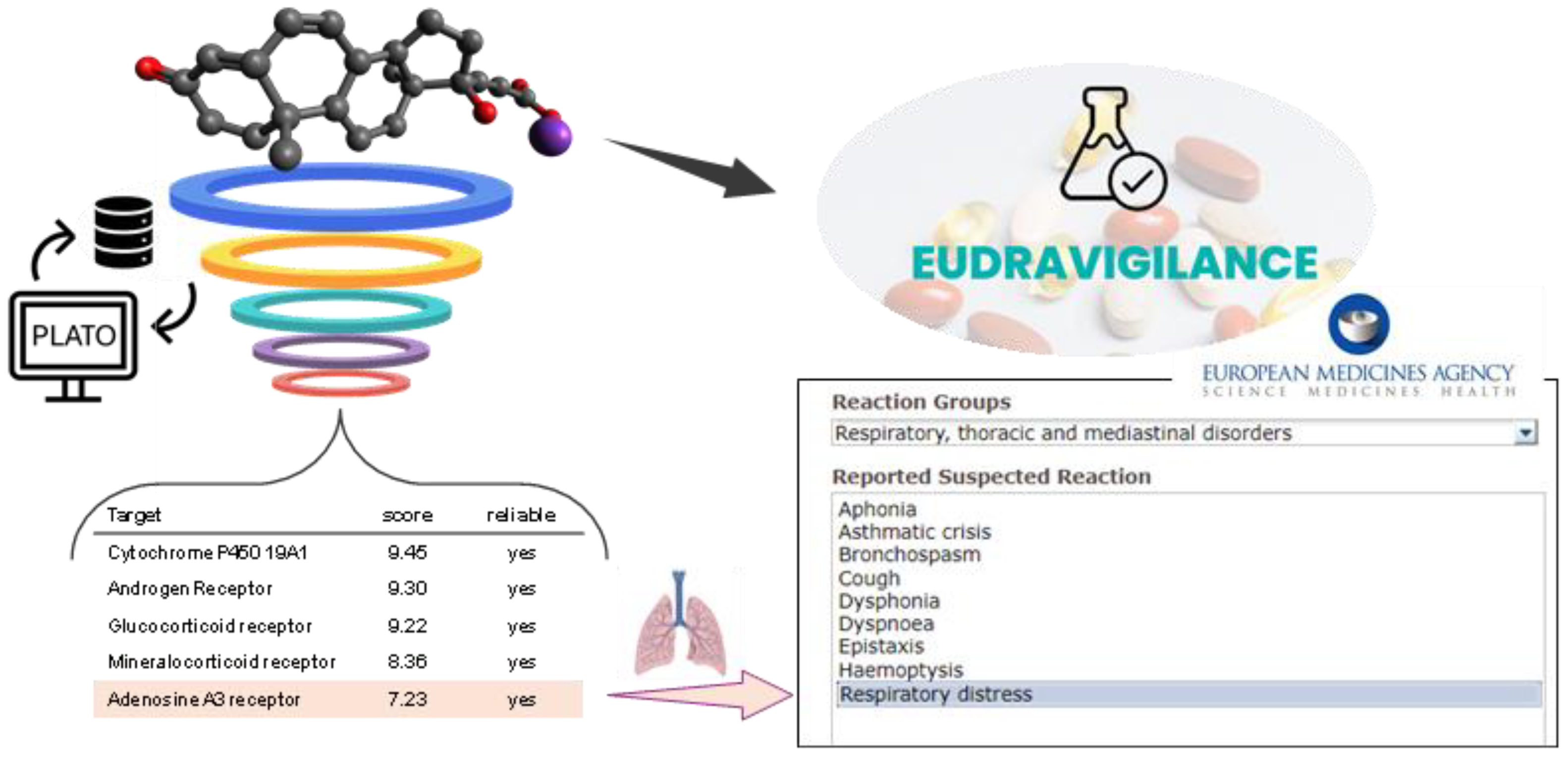

To possibly understand the canrenone capability of increasing the severity of SARS-CoV-2 infection, maybe postulating undisclosed off-targets drug activities, we queried a digital platform, namely PLATO (i.e., Polypharmacology pLATform predictiOn), developed by some of us for efficient target fishing and bioactivity profiling of bioactive small molecules [

xlvi,

xlvii]. The target fishing tool of PLATO (

Figure S3 in Supp. Mat.) prioritized, after the expected targets (androgen, glucocorticoid, mineralcorticoid, progesterone receptors), the A

3 adenosine receptor (A

3AR) among the potential targets of canrenone (

Figure 6). This in-silico outcome was rather interesting, considering that several studies showed that A

3AR, together with other purinergic receptors, may have a role in lung inflammation and that targeting these receptors for pulmonary diseases might be of therapeutic interest [

xlviii,

xlix,

l]. As a matter of fact, the modulation of purinergic receptors has been demonstrated to have an impact on severe consequences of COVID-19 [

li,

lii]. As far as A

3AR signaling transduction is concerned, its stimulation inhibits neutrophil degranulation in neutrophil-mediated tissue injury, TNFα and platelet activation, and factor-induced chemotaxis of human eosinophils [xlix]. Importantly, based on the ability to reduce levels of inflammatory mediators, piclidenoson, an A

3AR agonist, was tested for compassionate use in COVID-19 patients [xlix,

liii,

liv]. Thus, it can be hypothesized that canrenone interacting with A

3AR at pulmonary levels might act as an antagonist, in addition to eliciting other biological responses through its interaction with other steroid receptors, worsening the course of disease. In support of this hypothesis, among the adverse drug reactions reported for potassium canrenoate in the Eudravigilance database [

lv], there are some concerning the System Organ Class “Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders” with suspected reactions including bronchospasm, cough, dyspnea, respiratory distress (

Figure 6).

Unlike potassium canrenoate/canrenone, supplementation with vitamin D proved to significantly improve the clinical outcome of the hospitalized COVID-19 patients, at least with respect to the endpoint of medium-term mortality. Notably, among the survivors, 106 patients (42.9%) were receiving vitamin D, compared to only 69 patients (27.9%) among the deceased ones. This observation should be in line with the established anti-inflammatory properties of vitamin D and its impact on the management of the SARS-CoV-2 infection since the onset of the pandemic. Actually, a large meta-analysis indicates that vitamin D, in its active form, namely calcitriol, may have both beneficial and potentially negative effects in COVID-19 patients [lvi]. Calcitriol enhances ACE2 expression, helping to restore the ACE2/ACE ratio, which counteracts the pro-inflammatory and pro-thrombotic effects of SARS-CoV-2 [lvii]. Calcitriol has also been shown to reduce inflammation by inhibiting TLR-2 and the NLRP3 inflammasome, while promoting autophagy and antimicrobial peptide release. However, some studies, including the CORONAVIT trial, suggest that high doses of vitamin D may not effectively reduce the risk of infection or improve outcomes in hospitalized patients [lviii]. While calcitriol can reduce inflammation and enhance immune responses, it may also favor the production of certain cytokines, complicating its overall effectiveness. Our findings, however, suggest a beneficial effect of vitamin D supplementation. The apparent discrepancy with literature and clinical data once again underlines the need for further studies to clarify the therapeutic implications of vitamin D in the management of COVID-19.

5. Conclusions

This retrospective study showed that HF and AF resulted the cardiovascular comorbidities mainly associated to medium-term mortality in COVID-19 patients, even more significantly than cancer, asthma and respiratory diseases (e.g., COPD). Although HF or AF are characterized by a procoagulant state, no statistically significant association was found between OAT before or during hospitalization, with either warfarin as VKA or apixaban (edoxaban in a few cases) as DOAC, and the severity of COVID-19 disease and medium-term mortality.

Clinical data indicate that there is no evidence of harmful effects of VKA or DOAC (i.e., the number of patients in OAT are practically the same in the surviving and deceased patients’ groups) on the course of COVID-19 disease, although both drugs, similarly to subcutaneous administered LMWHs, do not alleviate the disease severity.

Regarding the other pharmacological treatments, two outcomes emerged as highly significant: (i) Canrenone or potassium canrenoate, as anti-aldosterone drugs, taken by hypertensive patients at admission were found to be associated with 90-days mortality; (ii) vitamin D showed particular benefit against COVID-19. While the effects of vitamin D has been highlighted in literature, though with contrasting arguments [lvi], the negative effects of anti-aldosterone drugs were quite surprising. These effects appeared consistent with the off-target activities suggested by the Eudravigilance database and the digital predictive platform PLATO, which suggested the A3 adenosine receptor as a potential additional target to the expected modulation of other nuclear steroid receptors. Ultimately, this study, conducted on a large cohort of COVID-19 patients, may contribute to assessing the impact of cardiovascular comorbidities and OAT in COVID-19 outcomes, as well as to provide insights into how other factors and/or drugs (aldosterone antagonists, for example) might influence the severity of the SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org, Figures S1-3; Table S1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.D.A., A.L. and F.M.; methodology, G.D., M.V.T. and P.G., O.N.; software, P.G.; validation, G.D., M.V.T., F.S., C.D., O.N; formal analysis, P.G.; investigation, A.L. and P.I.; resources, A.L. and F.M.; data curation, G.D., M.V.T. and P.G.; writing—original draft preparation, G.D., M.V.T., F.M., A.L. and C.D.A.; writing—review and editing, F.S., C.D., P.I., O.N. and A.D.; visualization, G.D., M.V.T., F.S., C.D. and P.G.; supervision, F.M., A.D., A.L. and C.D.A.; project administration, A.L. and C.D.A; funding acquisition, A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data available upon request.

Acknowledgments

F.S. gratefully acknowledges Puglia region for research grant PO FESR—FSE 2014/2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhou, P.; Yang, X.-L.; Wang, X.-G.; Hu, B.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, W.; Si, H.-R.; Zhu, Y.; Li, B.; Huang, C.-L.; et al. A Pneumonia Outbreak Associated with a New Coronavirus of Probable Bat Origin. Nature 2020, 579, 270–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Guo, S.; He, Y.; Zuo, Q.; Liu, D.; Xiao, M.; Fan, J.; Li, X. COVID-19 Is Distinct From SARS-CoV-2-Negative Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Guo, H.; Zhou, P.; Shi, Z.-L. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021, 19, 141–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. Extrapulmonary Manifestations of COVID-19. Nature Medicine 2020, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hempel, T.; Elez, K.; Krüger, N.; Raich, L.; Shrimp, J.H.; Danov, O.; Jonigk, D.; Braun, A.; Shen, M.; Hall, M.D.; et al. Synergistic Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry by Otamixaban and Covalent Protease Inhibitors: Pre-Clinical Assessment of Pharmacological and Molecular Properties. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12, 12600–12609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maio, F.; Rullo, M.; de Candia, M.; Purgatorio, R.; Lopopolo, G.; Santarelli, G.; Palmieri, V.; Papi, M.; Elia, G.; De Candia, E.; et al. Evaluation of Novel Guanidino-Containing Isonipecotamide Inhibitors of Blood Coagulation Factors against SARS-CoV-2 Virus Infection. Viruses 2022, 14, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samarelli, F.; Graziano, G.; Gambacorta, N.; Graps, E.A.; Leonetti, F.; Nicolotti, O.; Altomare, C.D. Small Molecules for the Treatment of Long-COVID-Related Vascular Damage and Abnormal Blood Clotting: A Patent-Based Appraisal. Viruses 2024, 16, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, V. Chronic Oral Anticoagulation and Clinical Outcome in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Cardiovascular Drugs and Therapy 2022, 36, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Topol, E. Solving the Puzzle of Long Covid. Science 2024, 383, 830–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, E.M.; Mackman, N.; Warren, R.Q.; Wolberg, A.S.; Mosnier, L.O.; Campbell, R.A.; Gralinski, L.E.; Rondina, M.T.; Van De Veerdonk, F.L.; Hoffmeister, K.M.; et al. Understanding COVID-19-Associated Coagulopathy. Nat Rev Immunol 2022, 22, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heestermans, M.; Poenou, G.; Hamzeh-Cognasse, H.; Cognasse, F.; Bertoletti, L. Anticoagulants: A Short History, Their Mechanism of Action, Pharmacology, and Indications. Cells 2022, 11, 3214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mele, M.; Mele, A.; Imbrici, P.; Samarelli, F.; Purgatorio, R.; Dinoi, G.; Correale, M.; Nicolotti, O.; Luca, A.D.; Brunetti, N.D.; et al. Pleiotropic Effects of Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Chronic Heart Failure and Atrial Fibrillation: Machine Learning Analysis. Molecules 2024, 29, 2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyropoulos, A.C. Good Practice Statements for Antithrombotic Therapy in the Management of COVID-19: Guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost. 2022, 20, 2226–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann Kreuziger, L.; Sholzberg, M.; Cushman, M. Anticoagulation in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. Blood 2022, 140, 809–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiegelenberg, J.P. Prior Use of Therapeutic Anticoagulation Does Not Protect against COVID-19 Related Clinical Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients: A Propensity Score-matched Cohort Study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021, 87, 4842–4850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covino, M.; De Matteis, G.; Della Polla, D.; Burzo, M.L.; Pascale, M.M.; Santoro, M.; De Cristofaro, R.; Gasbarrini, A.; De Candia, E.; Franceschi, F. Does Chronic Oral Anticoagulation Reduce In-Hospital Mortality among COVID-19 Older Patients? Aging Clin Exp Res 2021, 33, 2335–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, R.F.; Forte, K.; Buscher, M.G.; Chess, A.; Patel, A.; Moylan, T.; Mize, C.H.; Werdmann, M.; Ferrigno, R. The Association of Preinfection Daily Oral Anticoagulation Use and All-Cause in Hospital Mortality From Novel Coronavirus 2019 at 21 Days: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Critical Care Explorations 2021, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denas, G.; Gennaro, N.; Ferroni, E.; Fedeli, U.; Lorenzoni, G.; Gregori, D.; Iliceto, S.; Pengo. V. Reduction in All-Cause Mortality in COVID-19 Patients on Chronic Oral Anticoagulation: A Population-Based Propensity Score Matched Study. International Journal of Cardiology 2021, 329, 266–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumagalli, S.; Trevisan, C.; Signore, S.D.; Pelagalli, G.; Volpato, S.; Gareri, P.; Mossello, E.; Malara, A.; Monzani, F.; Coin, A.; et al. COVID-19 and Atrial Fibrillation in Older Patients: Does Oral Anticoagulant Therapy Provide a Survival Benefit?—An Insight from the GeroCovid Registry. Thromb Haemost 2022, 122, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ageno, W.; De Candia, E.; Iacoviello, L.; Di Castelnuovo, A. Protective Effect of Oral Anticoagulant Drugs in Atrial Fibrillation Patients Admitted for COVID-19: Results from the CORIST Study. Thrombosis Research 2021, 203, 138–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A.Y.; Tomlinson, L.; Brown, J.P.; Elson, W.; Walker, A.J.; Schultze, A. Association between Oral Anticoagulants and COVID 19-Related Outcomes: a population-based cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2022, e456–e463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, I.S.; Boulware, D.R.; Lee, T.C. Hydroxychloroquine for COVID19: The curtains close on a comedy of errors. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022, 11, 100268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deplanque, D. Hydroxychloroquine and COVID-19: The endgame! Therapie 2023, 78, 343–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller-Wieland, D.; Marx, N.; Dreher, M.; Fritzen, K.; Schnell, O. COVID-19 and Cardiovascular Comorbidities. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2022, 130, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ejaz, H.; Alsrhani, A.; Zafar, A.; et al. COVID-19 and Comorbidities: Deleterious Impact on Infected Patients. Journal of Infection and Public Health 2020, 13, 1833–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Klein, S.L.; Garibaldi, B.T.; Li, H.; Wu, C.; Osevala, N.M.; Li, T.; Margolick, J.B.; Pawelec, G.; Leng, S.X. Aging in COVID-19: Vulnerability, Immunity and Intervention. Ageing Research Reviews 2021, 65, 101205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, F.; Manla, Y.; Atallah, B.; Starling, R.C. Heart Failure and COVID-19. Heart Fail Rev 2021, 26, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smilowitz, N.R.; Kunichoff, D.; Garshick, M.; Shah, B.; Pillinger, M.; Hochman, J.S.; Berger, J.S. C-Reactive Protein and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with COVID-19. European Heart Journal 2021, 42, 2270–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Micco, P.; Russo, V.; Carannante, N.; Imparato, M.; Rodolfi, S.; Cardillo, G.; Lodigiani, C. Clotting Factors in COVID-19: Epidemiological Association and Prognostic Values in Different Clinical Presentations in an Italian Cohort. JCM 2020, 9, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, R.J.; Manuel, A. COVID-19 Cytokine Storm: The Interplay between Inflammation and Coagulation. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2020, 8, e46–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Li, D.; Wang, X.; Sun, Z. Abnormal Coagulation Parameters Are Associated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020, 18, 844–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thachil, J.; Tang. N.; Gando S.; Falanga A.; Cattaneo M.; Levi M.; Clark C.; Iba T. ISTH Interim Guidance on Recognition and Management of Coagulopathy in COVID-19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020, 18, 1023–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, V.; Cardillo, G.; Viggiano, G.V.; Mangiacapra, S.; Cavalli, A.; Fontanella, A.; Agrusta, F.; Bellizzi, A.; Amitrano, M.; Iannuzzo, M.; et al. Fondaparinux Use in Patients With COVID-19: A Preliminary Multicenter Real-World Experience. J Cardiovasc PharmacolTM 2020, 76, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiavone, M.; Gasperetti, A.; Mancone, M.; Curnis, A.; Mascioli, G.; Mitacchione, G.; Busana, M.; Sabato, F.; Gobbi, C.; Antinori, S.; et al. Oral Anticoagulation and Clinical Outcomes in COVID-19: An Italian Multicenter Experience. International Journal of Cardiology 2021, 323, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tremblay, D.; van Gerwen, M.; Alsen, M.; Thibaud, S.; Kessler, A.; Venugopal, S.; Makki, I.; Qin, Q.; Dharmapuri, S.; Jun, T.; et al. Impact of Anticoagulation Prior to COVID-19 Infection: A Propensity Score–Matched Cohort Study. Blood, 2020, 136, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, V.; Di Maio, M.; Attena, E.; Silverio, A.; Scudiero, F.; Celentani, D.; Lodigiani, C.; Di Micco, P. Clinical Impact of Pre-Admission Antithrombotic Therapy in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: A Multicenter Observational Study. Pharmacological Research 2020, 159, 104965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connors, J.M.; Levy, J.H. COVID-19 and Its Implications for Thrombosis and Anticoagulation. Blood 2020, 135, 2033–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadid, T.; Kafri, Z.; Al-Katib, A. Coagulation and Anticoagulation in COVID-19. Blood Reviews 2021, 47, 100761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scudiero, F.; Silverio, A.; Di Maio, M.; Russo, V.; Citro, R.; Personeni, D.; Cafro, A.; D’Andrea, A.; Attena, E.; Pezzullo, S.; et al. Pulmonary Embolism in COVID-19 Patients: Prevalence, Predictors and Clinical Outcome. Thrombosis Research 2021, 198, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magrini, E.; Garlanda, C. COVID-19 Thromboinflammation: Adding Inflammatory Fibrin to the Puzzle. Trends in Immunology, 2024; 45, 721–723. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, J.K.; Yan, Z.; Montano, M.; Sozmen E., G.; Dixit, K.; t, Al. Fibrin Drives Thromboinflammation and Neuropathology in COVID-19. Nature 2024, 633, 905–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicenzi, M.; Ruscica, M.; Iodice, S.; Rota, I.; Ratti, A.; Cosola, R.D.; Corsini, A.; Bollati, V.; Aliberti, S.; Blasi, F. The Efficacy of the Mineralcorticoid Receptor Antagonist Canrenone in COVID-19 Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Zuo, Y.; Yalavarthi, S.; Hunker, K.L.; Knight, J.S.; Kanthi, Y.; Obi, A.T.; Ganesh, S.K. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein S1-Mediated Endothelial Injury and Pro-Inflammatory State Is Amplified by Dihydrotestosterone and Prevented by Mineralocorticoid Antagonism. Viruses 2021, 13, 2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fels, B.; Acharya, S.; Vahldieck, C.; Graf, T.; a Käding, N.; Rupp, J.; Kusche-Vihrog, K. Mineralocorticoid Receptor-Antagonism Prevents COVID-19-Dependent Glycocalyx Damage. Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology 2022, 474, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Miyazaki, K.; Shah, P.; Kozai, L.; Kewcharoen, J. Association between Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonist and Mortality in SARS-CoV-2 Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare 2022, 10, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciriaco, F.; Gambacorta, N.; Trisciuzzi, D.; Nicolotti, O. PLATO: A Predictive Drug Discovery Web Platform for Efficient Target Fishing and Bioactivity Profiling of Small Molecules. IJMS 2022, 23, 5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciriaco, F.; Gambacorta, N.; Alberga, D.; Nicolotti, O. Quantitative Polypharmacology Profiling Based on a Multifingerprint Similarity Predictive Approach. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 61, 4868–4876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobson, K.A.; Merighi, S.; Varani, K.; Borea, P.A.; Baraldi, S.; Tabrizi, M.A.; Romagnoli, R.; Baraldi, P.G.; Ciancetta, A.; Tosh, D.K.; et al. A3 Adenosine Receptors as Modulators of Inflammation: From Medicinal Chemistry to Therapy. Med Res Rev. 2018, 38, 1031–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincenzi, F.; Pasquini, S.; Contri, C.; Cappello, M.; Nigro, M.; Travagli, A.; Merighi, S.; Gessi, S.; Borea, P.A.; Varani, K. Pharmacology of Adenosine Receptors: Recent Advancements. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duangrat, R.; Parichatikanond, W.; Chanmahasathien, W.; Mangmool, S. Adenosine A3 Receptor: From Molecular Signaling to Therapeutic Strategies for Heart Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Anjos, F.; Simões, J.L.B.; Assmann, C.E.; Carvalho, F.B.; Bagatini, M.D. Potential Therapeutic Role of Purinergic Receptors in Cardiovascular Disease Mediated by SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Immunology Research 2020, 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdés, A.; Moreno L., O.; Rello S., R.; Orduña, A.; Bernardo, D.; Cifuentes, A. Metabolomics Study of COVID-19 Patients in Four Different Clinical Stages. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarei, M.; Vaighan, N.S.; Ziai, S.A. Purinergic Receptor Ligands: The Cytokine Storm Attenuators, Potential Therapeutic Agents for the Treatment of COVID-19. IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY AND IMMUNOTOXICOLOGY, 2021, 1–11.

- Piclidenoson for Treatment of COVID-19 - A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04333472.

-

https://dap.ema.europa.eu/analytics/saw.dll?PortalPages.

- Gotelli, E.; Soldano, S.; Hysa, E.; Paolino, S.; Campitiello, R.; Pizzorni, C.; Sulli, A.; Smith, V.; Cutolo, M. Vitamin D and COVID-19: Narrative Review after 3 Years of Pandemic. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getachew, B.; Tizabi, Y. Vitamin D and COVID-19: Role of ACE2, age, gender, and ethnicity. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 5285–5294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolliffe, D.A.; Holt, H.; Greenig, M.; Talaei, M.; Perdek, N.; Pfeffer, P.; Vivaldi, G.; Maltby, S.; Symons, J.; Barlow, N.L.; et al. Effect of a test-and-treat approach to vitamin D supplementation on risk of all cause acute respiratory tract infection and Covid-19: phase 3 randomised controlled trial (CORONAVIT). BMJ 2022, 378, e071230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).