Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Post Hoc Power Analysis

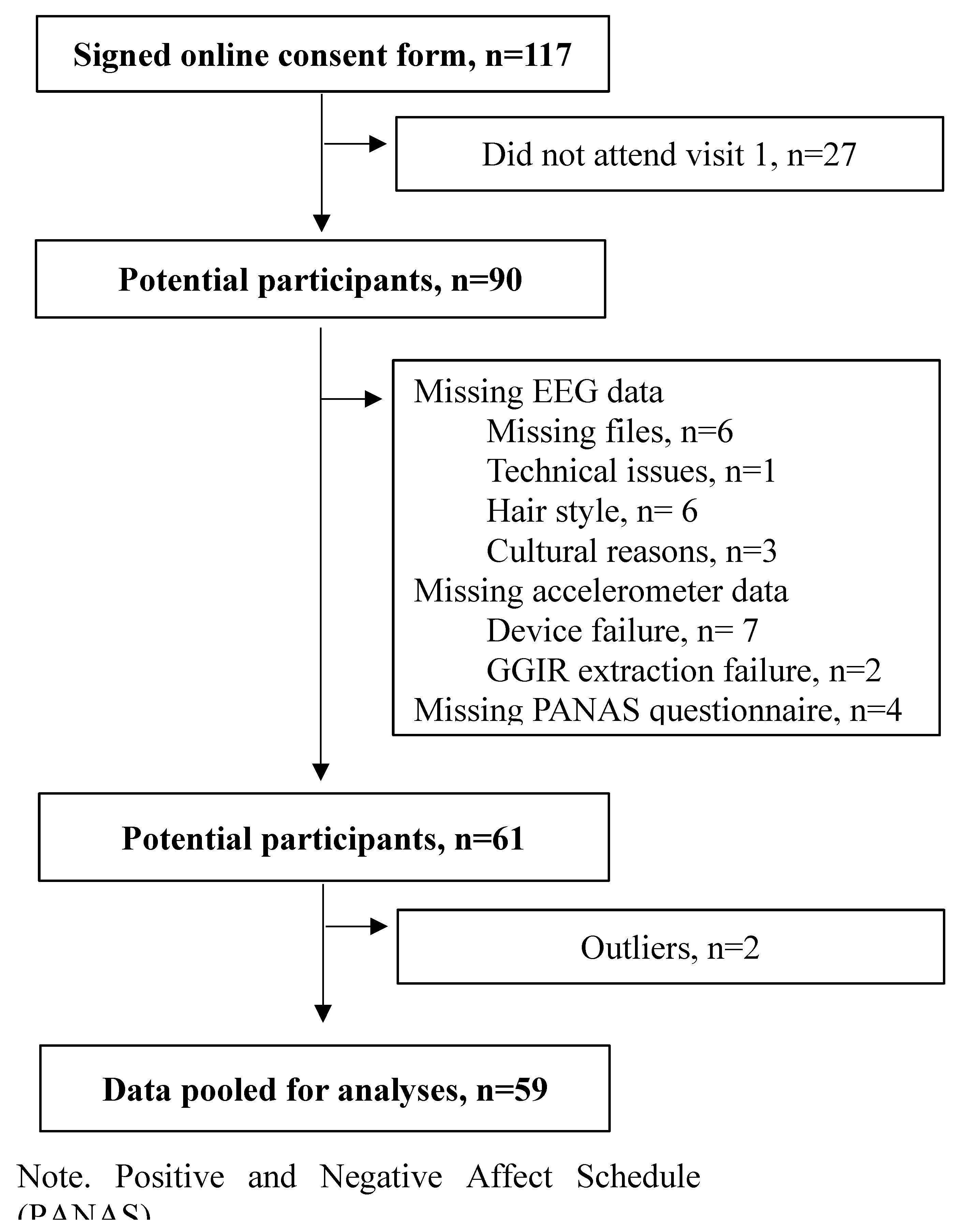

2.2. Participants

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Accelerometry

2.3.2. EEG

2.3.2.1. Recording

2.3.2.2. Processing

2.3.2.3. AA

2.3.3. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)

2.4. Procedure

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

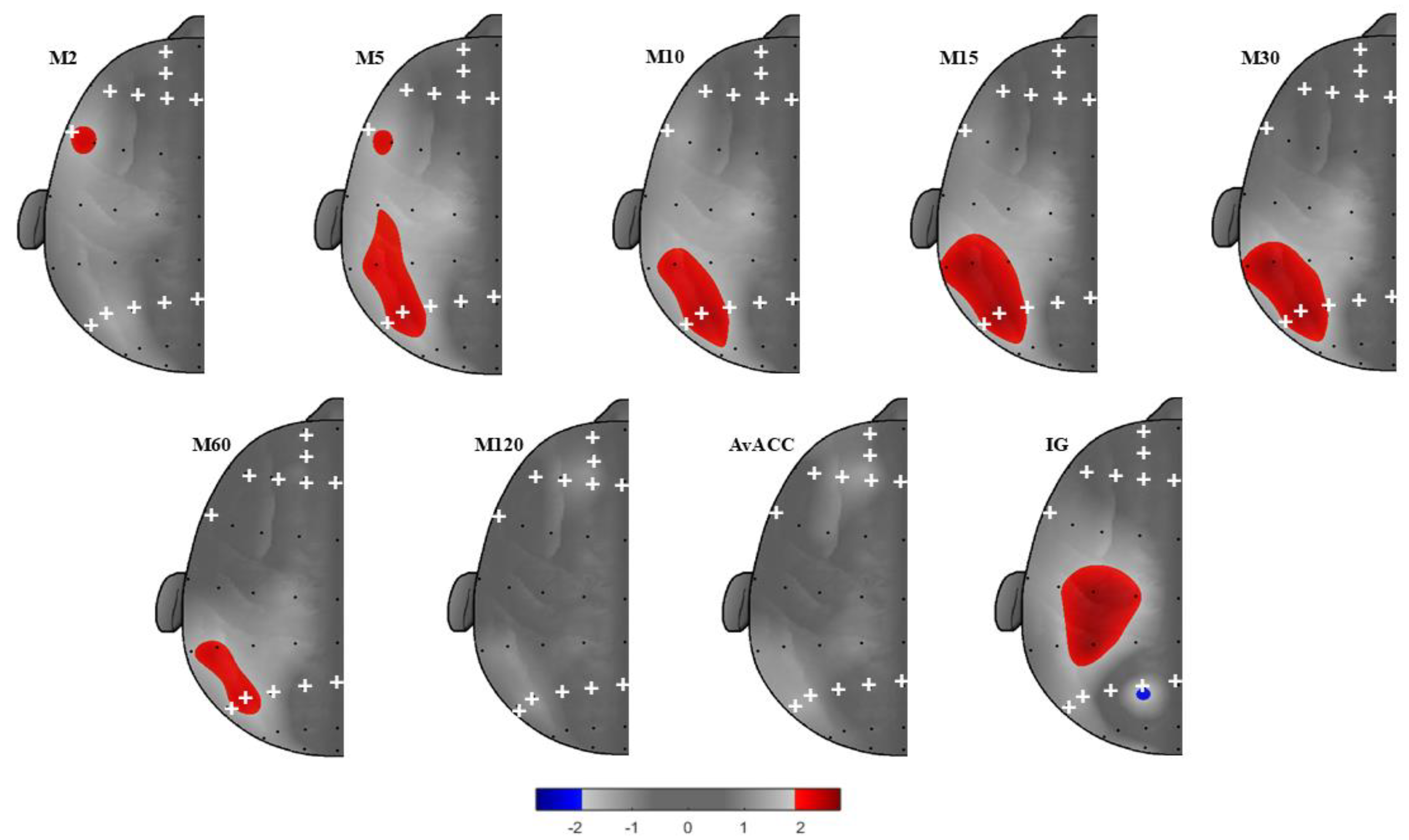

Frontal and parietal AA as predictors of PA

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bull, F.C.; Al-Ansari, S.S.; Biddle, S.; Borodulin, K.; Buman, M.P.; Cardon, G.; et al. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med 2020, 54, 1451–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piercy, K.L.; Troiano, R.P.; Ballard, R.M.; Carlson, S.A.; Fulton, J.E.; Galuska, D.A.; et al. The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018, 320, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, C.E.; Carlson, S.A.; Saint-Maurice, P.F.; Patel, S.; Salerno, E.; Loftfield, E.; et al. Sedentary Behavior in United States Adults: Fall 2019. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2021, 53, 2512–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Cao, C.; Kantor, E.D.; Nguyen, L.H.; Zheng, X.; Park, Y.; et al. Trends in Sedentary Behavior Among the US Population, 2001-2016. JAMA 2019, 321, 1587–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Difrancesco, S.; Penninx, B.W.J.H.; Merikangas, K.R.; van Hemert, A.M.; Riese, H.; Lamers, F. Within-day bidirectional associations between physical activity and affect: A real-time ambulatory study in persons with and without depressive and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety 2022, 39, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekäläinen, T.; Luchetti, M.; Terracciano, A.; Gamaldo, A.A.; Sliwinski, M.J.; Sutin, A.R. Momentary Associations Between Physical Activity, Affect, and Purpose in Life. Annals of Behavioral Medicine 2024, 58, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, L.T.; Hernandez, R.; Spruijt-Metz, D.; Gonzalez, J.S.; Pyatak, E.A. Movement matters: short-term impacts of physical activity on mood and well-being. J Behav Med 2023, 46, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, T.P.; Burzynska, A.; Voss, M.; Fanning, J.; Salerno, E.A.; Prakash, R.; et al. Brain Structure and Function Predict Adherence to an Exercise Intervention in Older Adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2022, 54, 1483–1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Ayllon, M.; Neumann, A.; Hofman, A.; Vernooij, M.W.; Neitzel, J. The bidirectional relationship between brain structure and physical activity: A longitudinal analysis in the UK Biobank. Neurobiology of Aging 2024, 138, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, D.M.; Dunsiger, S.; Ciccolo, J.T.; Lewis, B.A.; Albrecht, A.E.; Marcus, B.H. Acute affective response to a moderate-intensity exercise stimulus predicts physical activity participation 6 and 12 months later. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2008, 9, 231–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.J. What does the prefrontal cortex “do” in affect: perspectives on frontal EEG asymmetry research. Biological Psychology 2004, 67, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmon-Jones, E.; Gable, P.A.; Peterson, C.K. The role of asymmetric frontal cortical activity in emotion-related phenomena: A review and update. Biological Psychology 2010, 84, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Jones, E.; Gable, P.A. On the role of asymmetric frontal cortical activity in approach and withdrawal motivation: An updated review of the evidence. Psychophysiology 2018, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Jia, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, X. The impact of single sessions of aerobic exercise at varying intensities on depressive symptoms in college students: evidence from resting-state EEG in the parietal region. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmiero, M.; Piccardi, L. Frontal EEG Asymmetry of Mood: A Mini-Review. Front Behav Neurosci 2017, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silveira, R.; Prado, R.C.R.; Brietzke, C.; Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; Santos, T.M.; Pires, F.O.; et al. Prefrontal cortex asymmetry and psychological responses to exercise: A systematic review. Physiology & Behavior 2019, 208, 112580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufs, H.; Kleinschmidt, A.; Beyerle, A.; Eger, E.; Salek-Haddadi, A.; Preibisch, C.; et al. EEG-correlated fMRI of human alpha activity. NeuroImage 2003, 19, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzello, S.J.; Hall, E.E.; Ekkekakis, P. Regional brain activation as a biological marker of affective responsivity to acute exercise: Influence of fitness. Psychophysiology 2001, 38, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzzello, S.J.; Landers, D.M. State anxiety reduction and exercise: does hemispheric activation reflect such changes? Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 1994, 26, 1028. [Google Scholar]

- Petruzzello, S.J.; Tate, A.K. Brain activation, affect, and aerobic exercise: An examination of both state-independent and state-dependent relationships. Psychophysiology 1997, 34, 527–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M.; Graham, D.; Grant, A.; King, P.; Cooper, D. Regional brain activation and affective response to physical activity among healthy adolescents. Biol Psychol 2009, 82, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Petruzzello, S.J.; Hatfield, B.D. The Influence of Exercise Intensity on Frontal Electroencephalographic Asymmetry and Self-Reported Affect. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport 2010, 81, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.E.; Ekkekakis, P.; Petruzzello, S.J. Regional brain activity and strenuous exercise: Predicting affective responses using EEG asymmetry. Biological Psychology 2007, 75, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, E.E.; Ekkekakis, P.; Petruzzello, S.J. Predicting affective responses to exercise using resting EEG frontal asymmetry: Does intensity matter? Biological Psychology 2010, 83, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, M.; Kim, S.; Kim, J.; Petruzzello, S.J.; Hatfield, B.D. Examining the exercise-affect dose–response relationship: Does duration influence frontal EEG asymmetry? International Journal of Psychophysiology 2009, 72, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chesbro, G.A.; Owens, C.; Reese, M.; De Stefano, L.; Kellawan, J.M.; Larson, D.J.; et al. Changes in Brain Activity Immediately Post-Exercise Indicate a Role for Central Fatigue in the Volitional Termination of Exercise. Int J Exerc Sci 2024, 17, 220–234. [Google Scholar]

- Crabbe, J.B.; Dishman, R.K. Brain electrocortical activity during and after exercise: A quantitative synthesis. Psychophysiology 2004, 41, 563–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, W.; Nitschke, J.B.; Etienne, M.A.; Miller, G.A. Patterns of regional brain activity differentiate types of anxiety. J Abnorm Psychol 1997, 106, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, W.; Nitschke, J.B.; Miller, G.A. Lateralization in emotion and emotional disorders. Current Directions in Psychological Science 1998, 7, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosang, L.; Mouchlianitis, E.; Guérin, S.M.R.; Karageorghis, C.I. Effects of exercise on electroencephalography-recorded neural oscillations: a systematic review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology 2022, 0, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Threadgill, A.H.; Wilhelm, R.A.; Zagdsuren, B.; MacDonald, H.V.; Richardson, M.T.; Gable, P.A. Frontal asymmetry: A novel biomarker for physical activity and sedentary behavior. Psychophysiology 2020, 57, e13633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, R.A.; Lacey, M.F.; Masters, S.L.; Breeden, C.J.; Mann, E.; MacDonald, H.V.; et al. Greater weekly physical activity linked to left resting frontal alpha asymmetry in women: A study on gender differences in highly active young adults. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2024, 74, 102679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, S.A.; Adamo, K.B.; Hamel, M.E.; Hardt, J.; Gorber, S.C.; Tremblay, M. A comparison of direct versus self-report measures for assessing physical activity in adults: a systematic review. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2008, 5, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prince, S.A.; Cardilli, L.; Reed, J.L.; Saunders, T.J.; Kite, C.; Douillette, K.; et al. A comparison of self-reported and device measured sedentary behaviour in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2020, 17, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, P.; Ngetich, R.K.; Zhang, J.; Jin, Z.; Li, L. Differential involvement of frontoparietal network and insula cortex in emotion regulation. Neuropsychologia 2021, 161, 107991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, K.L.; Wager, T.; Taylor, S.F.; Liberzon, I. Functional neuroanatomy of emotion: a meta-analysis of emotion activation studies in PET and fMRI. Neuroimage 2002, 16, 331–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reiman, E.M.; Lane, R.D.; Ahern, G.L.; Schwartz, G.E.; Davidson, R.J.; Friston, K.J.; et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of externally and internally generated human emotion. Am J Psychiatry 1997, 154, 918–925. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, C.M.; Flannery, O.; Soto, D. Distinct parietal sites mediate the influences of mood, arousal, and their interaction on human recognition memory. Cogn Affect Behav Neurosci 2014, 14, 1327–1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chastin, S.F.M.; Buck, C.; Freiberger, E.; Murphy, M.; Brug, J.; Cardon, G.; et al. Systematic literature review of determinants of sedentary behaviour in older adults: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015, 12, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition 2018; 118.

- Plasqui, G.; Westerterp, K.R. Physical Activity Assessment With Accelerometers: An Evaluation Against Doubly Labeled Water. Obesity 2007, 15, 2371–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, A.; Jackson, D.; Hammerla, N.; Plötz, T.; Olivier, P.; Granat, M.H.; et al. Large Scale Population Assessment of Physical Activity Using Wrist Worn Accelerometers: The UK Biobank Study. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, e0169649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.H.; Rezende, L.F.M.; Joh, H.K.; Keum, N.; Ferrari, G.; Rey-Lopez, J.P.; et al. Long-Term Leisure-Time Physical Activity Intensity and All-Cause and Cause-Specific Mortality: A Prospective Cohort of US Adults. Circulation 2022, 146, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, A.; van Hees, V.T.; Stein, M.J.; Gastell, S.; Steindorf, K.; Herbolsheimer, F.; et al. Large-scale assessment of physical activity in a population using high-resolution hip-worn accelerometry: the German National Cohort (NAKO). Sci Rep 2024, 14, 7927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowlands, A.V. Moving Forward With Accelerometer-Assessed Physical Activity: Two Strategies to Ensure Meaningful, Interpretable, and Comparable Measures. Pediatr Exerc Sci 2018, 30, 450–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawkins, N.P.; Yates, T.; Edwardson, C.L.; Maylor, B.; Davies, M.J.; Dunstan, D.; et al. Comparing 24 h physical activity profiles: Office workers, women with a history of gestational diabetes and people with chronic disease condition(s). Journal of Sports Sciences 2021, 39, 219–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dygrýn, J.; Medrano, M.; Molina-Garcia, P.; Rubín, L.; Jakubec, L.; Janda, D.; et al. Associations of novel 24-h accelerometer-derived metrics with adiposity in children and adolescents. Environ Health Prev Med 2021, 26, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.P.; Connor Gorber, S.; Dinh, T.; Duggan, M.; et al. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth: An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2016, 41 (Suppl 3), S311–S327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairclough, S.J.; Rowlands, A.V.; del Pozo Cruz, B.; Crotti, M.; Foweather, L.; Graves, L.E.F.; et al. Reference values for wrist-worn accelerometer physical activity metrics in England children and adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2023, 20, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowlands, A.V.; Edwardson, C.L.; Davies, M.J.; Khunti, K.; Harrington, D.M.; Yates, T. Beyond Cut Points: Accelerometer Metrics that Capture the Physical Activity Profile. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2018, 50, 1323–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, A.V.; Dawkins, N.P.; Maylor, B.; Edwardson, C.L.; Fairclough, S.J.; Davies, M.J.; et al. Enhancing the value of accelerometer-assessed physical activity: meaningful visual comparisons of data-driven translational accelerometer metrics. Sports Med Open 2019, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RStudio Team. RStudio Desktop [Internet]. 2024. Available from: https://posit.co/download/rstudio-desktop/.

- van Hees, V.T.; Migueles, J.H.; Fang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Heywood, J.; Mirkes, E.R.; et al. GGIR: Raw Accelerometer Data Analysis [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2022 Dec 29]. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=GGIR.

- van Hees, V.T.; Fang, Z.; Langford, J.; Assah, F.; Mohammad, A.; da Silva, I.C.M.; et al. Autocalibration of accelerometer data for free-living physical activity assessment using local gravity and temperature: an evaluation on four continents. Journal of Applied Physiology 2014, 117, 738–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Hees VTvan Gorzelniak, L.; León, E.C.D.; Eder, M.; Pias, M.; Taherian, S.; et al. Separating Movement and Gravity Components in an Acceleration Signal and Implications for the Assessment of Human Daily Physical Activity. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e61691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, D.S.; Maylor, B.D. Comparison of physical activity metrics from two research-grade accelerometers worn on the non-dominant wrist and thigh in children. Journal of Sports Sciences 2023, 41, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quante, M.; Kaplan, E.R.; Rueschman, M.; Cailler, M.; Buxton, O.M.; Redline, S. Practical considerations in using accelerometers to assess physical activity, sedentary behavior, and sleep. Sleep Health 2015, 1, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, M.; Van Hees, V.T.; Hansen, B.H.; Ekelund, U. Age Group Comparability of Raw Accelerometer Output from Wrist- and Hip-Worn Monitors. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2014, 46, 1816–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, M.; Hansen, B.H.; van Hees, V.T.; Ekelund, U. Evaluation of raw acceleration sedentary thresholds in children and adults. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports 2017, 27, 1814–1823. [Google Scholar]

- Chatrian, G.E.; Lettich, E.; Nelson, P.L. Ten Percent Electrode System for Topographic Studies of Spontaneous and Evoked EEG Activities. American Journal of EEG Technology 1985, 25, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzen, D.; Genç, E.; Getzmann, S.; Larra, M.F.; Wascher, E.; Ocklenburg, S. Frontal and parietal EEG alpha asymmetry: a large-scale investigation of short-term reliability on distinct EEG systems. Brain Struct Funct 2022, 227, 725–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomarken, A.J.; Davidson, R.J.; Henriques, J.B. Resting frontal brain asymmetry predicts affective responses to films. J Pers Soc Psychol 1990, 59, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delorme, A.; Makeig, S. EEGLAB: an open source toolbox for analysis of single-trial EEG dynamics including independent component analysis. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2004, 134, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Calderon, J.; Luck, S.J. ERPLAB: an open-source toolbox for the analysis of event-related potentials. Front Hum Neurosci 2014, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, C.Y.; Hsu, S.H.; Pion-Tonachini, L.; Jung, T.P. Evaluation of Artifact Subspace Reconstruction for Automatic Artifact Components Removal in Multi-Channel EEG Recordings. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2020, 67, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothe, C.A.; Makeig, S. BCILAB: a platform for brain-computer interface development. J Neural Eng 2013, 10, 056014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pontifex, M.B.; Miskovic, V.; Laszlo, S. Evaluating the efficacy of fully automated approaches for the selection of eyeblink ICA components. Psychophysiology 2017, 54, 780–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allen, J.J.B.; Urry, H.L.; Hitt, S.K.; Coan, J.A. The stability of resting frontal electroencephalographic asymmetry in depression. Psychophysiology 2004, 41, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niermann, C.Y.N.; Herrmann, C.; von Haaren, B.; van Kann, D.; Woll, A. Affect and Subsequent Physical Activity: An Ambulatory Assessment Study Examining the Affect-Activity Association in a Real-Life Context. Front Psychol 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressman, S.D.; Petrie, K.J.; Sivertsen, B. How Strongly Connected Are Positive Affect and Physical Exercise? Results From a Large General Population Study of Young Adults. Clin Psychol Eur 2020, 2, e3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B (Methodological) 1995, 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drollette, E.S.; Pasupathi, P.A.; Slutsky-Ganesh, A.B.; Etnier, J.L. Take a Break for Memory Sake! Effects of Short Physical Activity Breaks on Inhibitory Control, Episodic Memory, and Event-Related Potentials in Children. Brain Sciences 2024, 14, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haehl, W.; Mirifar, A.; Beckmann, J. Regulate to facilitate: A scoping review of prefrontal asymmetry in sport and exercise. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 2022, 60, 102143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, P.W.; Steptoe, A.; Liao, Y.; Hsueh, M.C.; Chen, L.J. A cut-off of daily sedentary time and all-cause mortality in adults: a meta-regression analysis involving more than 1 million participants. BMC Medicine 2018, 16, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hicks, R.A.; Hall, P.A.; Staines, W.R.; McIlroy, W.E. Frontal alpha asymmetry and aerobic exercise: are changes due to cardiovascular demand or bilateral rhythmic movement? Biological Psychology 2018, 132, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, T.; Schneider, S.; Brümmer, V.; Strüder, H.K. Frontal EEG asymmetry: The effects of sustained walking in the elderly. Neuroscience Letters 2010, 485, 134–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, X.; Liu, X.; Van Dam, N.T.; Hof, P.R.; Fan, J. Cognition-emotion integration in the anterior insular cortex. Cereb Cortex 2013, 23, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cefis, M.; Chaney, R.; Wirtz, J.; Méloux, A.; Quirié, A.; Leger, C.; et al. Molecular mechanisms underlying physical exercise-induced brain BDNF overproduction. Front Mol Neurosci 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakes, T.R.; Pizzagalli, D.A.; Hendrick, A.M.; Horras, K.A.; Larson, C.L.; Abercrombie, H.C.; et al. Functional coupling of simultaneous electrical and metabolic activity in the human brain. Hum Brain Mapp 2004, 21, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, A. Functional neuroanatomy of altered states of consciousness: the transient hypofrontality hypothesis. Conscious Cogn 2003, 12, 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ide, K.; Secher, N.H. Cerebral blood flow and metabolism during exercise. Prog Neurobiol 2000, 61, 397–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.K.; Cohen, J.D. An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annu Rev Neurosci 2001, 24, 167–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coan, J.A.; Allen, J.J.B. Frontal EEG asymmetry as a moderator and mediator of emotion. Biological Psychology 2004, 67, 7–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marent, P.J.; Cardon, G.; Dumuid, D.; Albouy, G.; van Uffelen, J. 24-hour movement behaviours are cross-sectionally associated with cognitive function in healthy adults aged 55 years and older. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 38619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rollo, S.; Antsygina, O.; Tremblay, M.S. The whole day matters: Understanding 24-hour movement guideline adherence and relationships with health indicators across the lifespan. Journal of Sport and Health Science 2020, 9, 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Measure | Mean (+-SD) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 21.76 (2.92) |

| Height (cm) | 170.49 (10.50) |

| Weight (kg) | 76.36 (15.92) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.18 (5.00) |

| Gender (n[%]) | |

| Male | 17[29%] |

| Female | 42[71%] |

| Ethnicity (n[%]) | |

| Non-Hispanic | 43[73%] |

| Hispanic | 12[20%] |

| No response | 4[7%] |

| ST (min/day) | 743.32 (95.91) |

| LPA (min/day) | 142.00 (35.36) |

| MVPA (min/day) | 109.34 (36.52) |

| IG (mg) | -2.48 (0.16) |

| AvAcc (mg) | 28.82 (6.94) |

| M120 (mg) | 69.78 (21.32) |

| M60 (mg) | 89.36 (30.49) |

| M30 (mg) | 110.78 (40.75) |

| M15 (mg) | 135.72 (52.34) |

| M10 (mg) | 152.76 (63.26) |

| M5 (mg) | 183.50 (81.80) |

| M2 (mg) | 235.41 (136.81) |

| aPositive affect | 24.90 (9.62) |

| aNegative affect | 12.98 (3.09) |

| Overall model for sex, affect, and EEG | Predictor | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | F | p | B | Berror | β | t | p | CI | |

| IG | |||||||||

| P2-P1 | .264 | 6.573 | .001 | -.403 | .185 | -.264 | -2.180 | .034* | -.774, -.033 |

| M60 | |||||||||

| P6-P5 | .234 | 5.614 | .002 | 34.700 | 14.600 | .292 | 2.377 | .021* | 5.441, 63.960 |

| M30 | |||||||||

| P6-P5 | .295 | 7.669 | .000 | 48.924 | 18.724 | .308 | 2.613 | .012* | 11.401, 86.448 |

| P4-P3 | .276 | 6.976 | .000 | 60.759 | 26.699 | .268 | 2.276 | .027* | 7.254, 114.264 |

| M15 | |||||||||

| P6-P5 | .297 | 7.761 | .000 | 62.783 | 24.009 | .308 | 2.615 | .011* | 14.668, 110.897 |

| P4-P3 | .278 | 7.076 | .000 | 78.156 | 34.227 | .269 | 2.283 | .026* | 9.563, 146.748 |

| M10 | |||||||||

| P6-P5 | .265 | 6.606 | .001 | 73.913 | 29.679 | .300 | 2.490 | .016* | 14.434, 133.391 |

| P4-P3 | .250 | 6.105 | .001 | 94.063 | 42.178 | .268 | 2.230 | .030* | 9.538, 178.589 |

| M5 | |||||||||

| P6-P5 | .260 | 6.440 | .001 | 91.054 | 38.508 | .286 | 2.365 | .022* | 13.882, 168.227 |

| P4-P3 | .244 | 5.918 | .001 | 113.726 | 54.752 | .250 | 2.077 | .042* | 4.000, 223.453 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).