Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. Number of Participants and fNIRS Data Analyzed

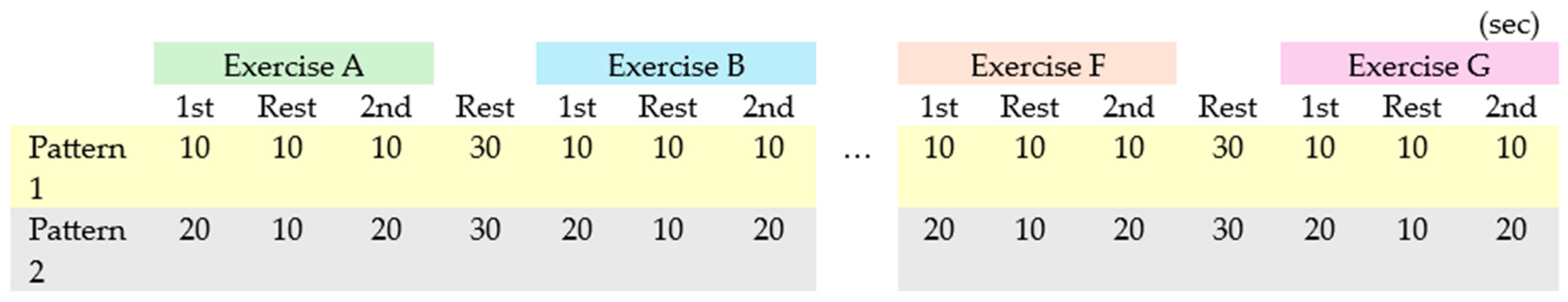

2.2. Procedure

2.3. LPA

3. Measures

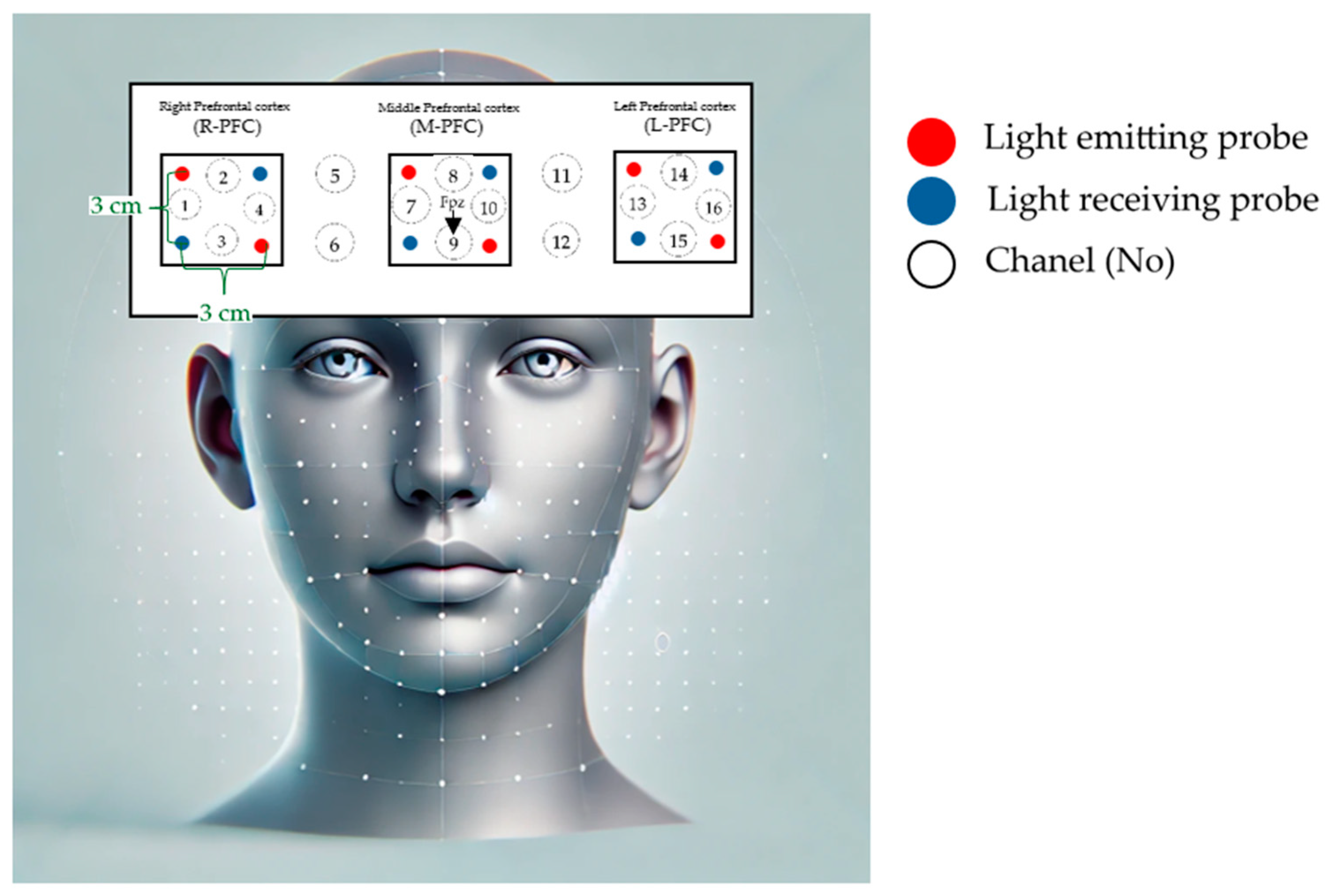

3.1. fNIRS

3.2. fNIRS Data Processing

- Data where oxy-Hb and deoxy-Hb were in antiphase were considered for further analysis.

- Data were retained when deoxy-Hb levels were stable and approached zero, indicating minimal extracerebral interference.

- Simultaneous increases or decreases in oxy-Hb and deoxy-Hb levels were specifically analyzed to assess their coherence.

- Data were selected if the proportion of deoxy-Hb remained lower than that of oxy-Hb, unless there was significant variation in the deoxy-Hb signal, which led to data exclusion.

- -

- Channels 1 to 4 were assigned to the right PFC (R-PFC).

- -

- Channels 7 to 10 corresponded to the middle PFC (M-PFC).

- -

- Channels 13 to 16 represented the left PFC (L-PFC).

4. Statistical Analysis

5. Results

Ratings of Perceived Exertion (RPE)

Comparison Between Rest and LPA (Pattern 2)

Comparison Between Pattern 1 and Pattern 2

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- H. İ. Ceylan, A. F. Silva, R. Ramirez-Campillo, and E. Murawska-Ciałowicz, “Exploring the Effect of Acute and Regular Physical Exercise on Circulating Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor Levels in Individuals with Obesity: A Comprehensive Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” May 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- M. Kukla-Bartoszek and K. Głombik, “Train and Reprogram Your Brain: Effects of Physical Exercise at Different Stages of Life on Brain Functions Saved in Epigenetic Modifications,” Nov. 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- F. Latino and F. Tafuri, “The role of physical activity in the physiological activation of the scholastic pre-requirements,” AIMS Neurosci, vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 244–259, 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Li, X. Qu, K. Shi, Y. Yang, and J. Sun, “Physical exercise for brain plasticity promotion an overview of the underlying oscillatory mechanism,” 2024, Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- J. Q. Jing, S. J. Jia, and C. J. Yang, “Physical activity promotes brain development through serotonin during early childhood,” Aug. 30, 2024, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Khalil, “The BDNF-Interactive Model for Sustainable Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Humans: Synergistic Effects of Environmentally-Mediated Physical Activity, Cognitive Stimulation, and Mindfulness,” Dec. 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- R. R. Kraemer and B. R. Kraemer, “The effects of peripheral hormone responses to exercise on adult hippocampal neurogenesis,” 2023, Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- M. H. Khalil, “Neurosustainability,” Front Hum Neurosci, vol. 18, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. L. Plas et al., “Neural circuits for the adaptive regulation of fear and extinction memory,” 2024, Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- S. Battaglia, A. Avenanti, L. Vécsei, and M. Tanaka, “Neural Correlates and Molecular Mechanisms of Memory and Learning,” Mar. 01, 2024, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI). [CrossRef]

- M. Ribeiro, Y. N. Yordanova, V. Noblet, G. Herbet, and D. Ricard, “White matter tracts and executive functions: A review of causal and correlation evidence,” Feb. 01, 2024, Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- F. Mao, F. Huang, S. Zhao, and Q. Fang, “Effects of cognitively engaging physical activity interventions on executive function in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” 2024, Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Salehinejad, E. Ghanavati, M. H. A. Rashid, and M. A. Nitsche, “Hot and cold executive functions in the brain: A prefrontal-cingular network,” Brain Neurosci Adv, vol. 5, p. 239821282110077, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Boyle, S. Betts, and H. Lu, “Monoaminergic Modulation of Learning and Cognitive Function in the Prefrontal Cortex,” Brain Sci, vol. 14, no. 9, p. 902, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Anderson, E. J. Wind, and L. S. Robison, “Exploring the neuroprotective role of physical activity in cerebral small vessel disease,” Jun. 15, 2024, Elsevier B.V. [CrossRef]

- A. Kaiser et al., “A Randomized Controlled Trial on the Effects of a 12-Week High- vs. Low-Intensity Exercise Intervention on Hippocampal Structure and Function in Healthy, Young Adults,” Front Psychiatry, vol. 12, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- R. B. Batacan, M. J. Duncan, V. J. Dalbo, P. S. Tucker, and A. S. Fenning, “Effects of Light Intensity Activity on CVD Risk Factors: A Systematic Review of Intervention Studies,” 2015, Hindawi Limited. [CrossRef]

- D. Greenwalt, S. Phillips, C. Ozemek, R. Arena, and A. Sabbahi, “The Impact of Light Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior and Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Extending Lifespan and Healthspan Outcomes: How Little is Still Significant? A Narrative Review,” Oct. 01, 2023, Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- L. Youssef et al., “Neurophysiological effects of acute aerobic exercise in young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis,” Sep. 01, 2024, Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- J. Siette et al., “A Pilot Study of BRAIN BOOTCAMP, a Low-Intensity Intervention on Diet, Exercise, Cognitive Activity, and Social Interaction to Improve Older Adults’ Dementia Risk Scores,” Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Martínez-Díaz and L. Carrasco Páez, “Little but Intense: Using a HIIT-Based Strategy to Improve Mood and Cognitive Functioning in College Students,” Healthcare (Switzerland), vol. 11, no. 13, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J. Yu, G. Li, and Y. Wang, “Exercise intervention on the brain structure and function of patients with mild cognitive impairment: systematic review based on magnetic resonance imaging studies,” 2024, Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- Huang et al., “Comparative effects of different types of exercise on endothelial function, arterial stiffness, and executive function in sedentary young individuals: a randomized controlled trial,” Mar. 11, 2024. [CrossRef]

- X. Chen, N. Hu, H. Han, G. Cai, and Y. Qin, “Effects of high-intensity interval training in a cold environment on arterial stiffness and cerebral hemodynamics in sedentary Chinese college female students post-COVID-19,” Front Neurol, vol. 15, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Keshmiri, H. Sumioka, R. Yamazaki, and H. Ishiguro, “Differential effect of the physical embodiment on the prefrontal cortex activity as quantified by its entropy,” Entropy, vol. 21, no. 9, Sep. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Zimmermann, R. Richardson, and K. D. Baker, “Maturational changes in prefrontal and amygdala circuits in adolescence: implications for understanding fear inhibition during a vulnerable period of development,” Mar. 01, 2019, MDPI AG. [CrossRef]

- Trofimova, “Functional Constructivism Approach to Multilevel Nature of Bio-Behavioral Diversity,” Oct. 27, 2021, Frontiers Media S.A. [CrossRef]

- A. Kampaite et al., “Brain connectivity changes underlying depression and fatigue in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: A systematic review,” PLoS One, vol. 19, no. 3 March, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Naito, K. Oka, and K. Ishii, “Hemodynamics of short-duration light-intensity physical exercise in the prefrontal cortex of children: a functional near-infrared spectroscopy study,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- G. Cruz, Y. N. Leow, N. M. Le, E. Adam, R. Huda, and M. Sur, “CORTICAL-SUBCORTICAL INTERACTIONS IN GOAL-DIRECTED BEHAVIOR,” Physiol Rev, vol. 103, no. 1, pp. 347–389, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. W. Cacciatore, D. I. Anderson, and R. G. Cohen, “Central mechanisms of muscle tone regulation: implications for pain and performance,” Front Neurosci, vol. 18, 2024. [CrossRef]

- H. B. Coslett, J. Medina, D. K. Goodman, Y. Wang, and A. Burkey, “Can they touch? A novel mental motor imagery task for the assessment of back pain,” Frontiers in Pain Research, vol. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Sanchis-Navarro, F. G. Luna, J. Lupiáñez, and F. Huertas, “Benefits of a light- intensity bout of exercise on attentional networks functioning,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, p. 25745, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jung et al., “A mechanistic understanding of cognitive performance deficits concurrent with vigorous intensity exercise,” Brain Cogn, vol. 180, Oct. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Guan et al., “Effects and neural mechanisms of different physical activity on major depressive disorder based on cerebral multimodality monitoring: a narrative review,” 2024, Frontiers Media SA. [CrossRef]

- Jung, S. Ryu, M. Kang, A. H. Javadi, and P. D. Loprinzi, “Evaluation of the transient hypofrontality theory in the context of exercise: A systematic review with meta-analysis,” Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, vol. 75, no. 7, pp. 1193–1214, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Crum et al., “Body fat predictive of acute effects of exercise on prefrontal hemodynamics and speed,” Neuropsychologia, vol. 196, Apr. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Kan et al., “Differences in cortical activation characteristics between younger and older adults during single/dual-tasks: A cross-sectional study based on fNIRS,” Biomed Signal Process Control, vol. 99, Jan. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Saraiva, M. A. Castro, and J. P. Vilas-Boas, “Muscular and Prefrontal Cortex Activity during Dual-Task Performing in Young Adults,” Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 736–747, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. H. M. Monteiro, A. J. Marcori, N. R. da Conceição, R. L. M. Monteiro, D. B. Coelho, and L. A. Teixeira, “Cortical activity in body balance tasks as a function of motor and cognitive demands: A systematic review,” Nov. 01, 2024, John Wiley and Sons Inc. [CrossRef]

- E. Zangen et al., “Prefrontal cortex neurons encode ambient light intensity differentially across regions and layers,” Nat Commun, vol. 15, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. Kimura, T. Hosokawa, T. Ujikawa, and T. Ito, “Effects of different exercise intensities on prefrontal activity during a dual task,” Sci Rep, vol. 12, no. 1, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Hong, D. Bao, B. Manor, Y. Zhou, and J. Zhou, “Effects of endurance exercise on physiologic complexity of the hemodynamics in prefrontal cortex,” Neurophotonics, vol. 11, no. 01, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Damrongthai et al., “Slow running benefits: Boosts in mood and facilitation of prefrontal cognition even at very light intensity,” Jan. 30, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Jung, S. Ryu, M. Kang, A. H. Javadi, and P. D. Loprinzi, “Evaluation of the transient hypofrontality theory in the context of exercise: A systematic review with meta-analysis,” Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, vol. 75, no. 7, pp. 1193–1214, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Cheng, L. Cong, D. Hui, C. Teng, W. Li, and J. Ma, “Enhancement of prefrontal functional connectivity under the influence of concurrent physical load during mental tasks,” Front Hum Neurosci, vol. 18, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. Liu, Y. Liu, and L. Wu, “Exploring the dynamics of prefrontal cortex in the interaction between orienteering experience and cognitive performance by fNIRS,” Sci Rep, vol. 14, no. 1, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Sahnoune et al., “Exercise ameliorates neurocognitive impairments in a translational model of pediatric radiotherapy,” Neuro Oncol, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 695–704, Apr. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. Hosang, E. Mouchlianitis, S. M. R. Guérin, and C. I. Karageorghis, “Effects of exercise on electroencephalography-recorded neural oscillations: a systematic review,” Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Sanaeifar et al., “Beneficial effects of physical exercise on cognitive-behavioral impairments and brain-derived neurotrophic factor alteration in the limbic system induced by neurodegeneration,” Oct. 01, 2024, Elsevier Inc. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J. Lu, Y. Sun, and J. Li, “Recreational gymnastics exercise of moderate intensity enhances executive function in Chinese preschoolers: A randomized controlled trial,” Psych J, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

| All | Pattern 1 | Pattern 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Age, mean ± SD, years | 12.3 ± 1.4 | 12.3 ± 1.3 | 12.3 ± 1.3 | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 24 | 63 | 21 | 66 | 22 | 65 |

| Female | 14 | 37 | 11 | 34 | 12 | 35 |

| Age Groups | ||||||

| 10–11 years | 12 | 31 | 9 | 29 | 10 | 30 |

| 12 years | 15 | 39 | 12 | 38 | 13 | 38 |

| 13–14 years | 11 | 29 | 8 | 25 | 9 | 27 |

| Dominant Hand | ||||||

| Right | 35 | 92 | 30 | 91 | 31 | 91 |

| Left | 3 | 8 | 3 | 9 | 3 | 9 |

| Event ID | Exercise | Description |

|---|---|---|

| A | Nick Tilts | Gently tilt your head toward one shoulder and hold for a few seconds, then repeat on the other side. |

| B | Arm Cross Stretch | Extend one arm straight across your chest. Use the other hand to pull the extended arm closer, stretching the shoulder. |

| C | Wrist Rolls | Extend your arms out in front of you and gently roll your wrists clockwise and then counterclockwise. |

| D | Side Bends | Stand with feet shoulder-width apart. Slowly bend to one side, sliding your hand down your leg, then switch to the other side. |

| E | Heel Digs | Stand upright and dig one heel into the ground, toe pointing upwards. Alternate legs. |

| F | Torso Twists | Stand with feet planted firmly, twist your torso to one side as far as is comfortable, then switch sides. |

| G | Marching in Place | Lift your knees high one at a time, as if marching on the spot. |

| Ankle Circles | Lift one foot off the ground and rotate the ankle in a circular motion. Rotate a few times in one direction, then switch directions and finally switch feet. |

|

Event (ID-Seconds) |

Region |

Oxy-Hb (mM・mm) | Oxy-Hb (Z-score) |

F |

P |

η² |

||||||

| Rest | Exercise | Rest | Exercise | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

| A-10 Upward Stretch | R-PFC | 0,05 | 0,11 | 0,09 | 0,12 | -0,10 | 0,08 | 0,65 | 0,10 | 1,35 | 0.430 | 0,01 |

| M-PFC | -0,03 | 0,10 | 0,06 | 0,14 | -0,27 | 0,09 | 0,68 | 0,11 | 4,60 | 0.039* | 0,07 | |

| L-PFC | 0,02 | 0,15 | 0,08 | 0,16 | -0,15 | 0,13 | 0,80 | 0,14 | 1,22 | 0.276 | 0,03 | |

| B-10 Shoulder Stretch | R-PFC | 0,01 | 0,09 | 0,02 | 0,10 | -0,07 | 0,07 | 0,50 | 0,08 | 1,08 | 0.362 | 0,00 |

| M-PFC | 0,00 | 0,08 | 0,12 | 0,15 | -0,12 | 0,10 | 0,85 | 0,12 | 2,03 | 0.092 | 0,04 | |

| L-PFC | 0,01 | 0,11 | 0,10 | 0,12 | -0,10 | 0,09 | 0,89 | 0,11 | 1,40 | 0.249 | 0,02 | |

| C-10 Elbow Circles | R-PFC | -0,02 | 0,12 | 0,08 | 0,14 | -0,16 | 0,11 | 0,85 | 0,12 | 1,88 | 0.085 | 0,05 |

| M-PFC | -0,05 | 0,14 | 0,10 | 0,16 | -0,50 | 0,13 | 0,69 | 0,14 | 3,87 | 0.042* | 0,08 | |

| L-PFC | -0,03 | 0,13 | 0,11 | 0,15 | -0,42 | 0,12 | 0,87 | 0,13 | 5,21 | 0.019* | 0,09 | |

| D-10 Trunk Twist | R-PFC | 0,00 | 0,10 | 0,07 | 0,12 | -0,10 | 0,08 | 0,62 | 0,10 | 1,35 | 0.440 | 0,01 |

| M-PFC | -0,03 | 0,11 | 0,08 | 0,14 | -0,27 | 0,09 | 0,80 | 0,11 | 4,90 | 0.033* | 0,07 | |

| L-PFC | -0,04 | 0,12 | 0,09 | 0,15 | -0,29 | 0,12 | 0,84 | 0,13 | 5,87 | 0.017* | 0,10 | |

| E-10 Washing Hands | R-PFC | 0,03 | 0,10 | 0,06 | 0,12 | -0,10 | 0,08 | 0,63 | 0,10 | 1,27 | 0.402 | 0,01 |

| M-PFC | 0,02 | 0,09 | 0,11 | 0,14 | -0,22 | 0,09 | 0,48 | 0,12 | 2,78 | 0.068 | 0,05 | |

| L-PFC | 0,00 | 0,08 | 0,09 | 0,11 | -0,34 | 0,07 | 0,89 | 0,10 | 3,87 | 0.049* | 0,06 | |

| F-10 Thumb & Pinky | R-PFC | -0,01 | 0,11 | 0,07 | 0,13 | -0,20 | 0,10 | 0,72 | 0,11 | 1,70 | 0.285 | 0,02 |

| M-PFC | -0,03 | 0,12 | 0,10 | 0,14 | -0,29 | 0,11 | 0,72 | 0,13 | 4,98 | 0.028* | 0,08 | |

| L-PFC | -0,02 | 0,13 | 0,12 | 0,15 | -0,34 | 0,12 | 0,89 | 0,13 | 6,73 | 0.012* | 0,12 | |

| G-10 Single Leg Balance | R-PFC | -0,04 | 0,10 | 0,09 | 0,12 | -0,28 | 0,08 | 0,90 | 0,10 | 6,10 | 0.017* | 0,11 |

| M-PFC | -0,08 | 0,09 | 0,15 | 0,12 | -0,38 | 0,07 | 0,96 | 0,09 | 8,23 | 0.008* | 0,14 | |

| L-PFC | -0,06 | 0,11 | 0,13 | 0,13 | -0,42 | 0,10 | 0,78 | 0,11 | 9,45 | 0.004* | 0,16 | |

|

Event (ID-Seconds) |

Region |

Oxy-Hb (mM mm) | Oxy-Hb (Z-score) |

F |

P |

η² |

||||||

| Rest | Exercise | Rest | Exercise | |||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||||

| A-20 Upward Stretch | R-PFC | -0,05 | 0,22 | 0,10 | 0,30 | -0,32 | 0,90 | 0,28 | 0,92 | 7,12 | 0.011* | 0,10 |

| M-PFC | 0,02 | 0,25 | 0,12 | 0,28 | -0,22 | 0,78 | 0,64 | 1,15 | 3,32 | 0.068 | 0,05 | |

| L-PFC | -0,03 | 0,23 | 0,14 | 0,27 | -0,14 | 0,80 | 0,71 | 1,10 | 2,10 | 0.125 | 0,03 | |

| B-20 Shoulder Stretch | R-PFC | 0,00 | 0,14 | 0,08 | 0,18 | -0,08 | 0,68 | 0,62 | 1,01 | 1,82 | 0.220 | 0,02 |

| M-PFC | 0,04 | 0,16 | 0,15 | 0,20 | -0,16 | 0,80 | 0,82 | 0,98 | 3,95 | 0.049* | 0,06 | |

| L-PFC | -0,01 | 0,15 | 0,09 | 0,19 | -0,12 | 0,73 | 0,68 | 1,03 | 2,37 | 0.099 | 0,04 | |

| C-20 Elbow Circles | R-PFC | 0,02 | 0,13 | 0,11 | 0,24 | -0,18 | 0,72 | 0,71 | 1,15 | 4,28 | 0.041* | 0,07 |

| M-PFC | -0,03 | 0,17 | 0,14 | 0,25 | -0,25 | 0,65 | 0,89 | 1,10 | 5,42 | 0.026* | 0,09 | |

| L-PFC | -0,02 | 0,14 | 0,12 | 0,23 | -0,15 | 0,68 | 0,74 | 1,07 | 3,10 | 0.073 | 0,05 | |

| D-20 Trunk Twist | R-PFC | -0,06 | 0,12 | 0,15 | 0,20 | -0,38 | 0,70 | 0,85 | 1,10 | 18,31 | < 0.001* | 0,21 |

| M-PFC | -0,08 | 0,18 | 0,19 | 0,27 | -0,40 | 0,74 | 0,92 | 1,12 | 22,10 | < 0.001* | 0,24 | |

| L-PFC | -0,09 | 0,16 | 0,20 | 0,26 | -0,45 | 0,78 | 1,01 | 1,15 | 26,87 | < 0.001* | 0,28 | |

| E-20 Washing Hands | R-PFC | -0,04 | 0,13 | 0,09 | 0,18 | -0,30 | 0,68 | 0,64 | 0,98 | 7,21 | 0.012* | 0,11 |

| M-PFC | -0,05 | 0,15 | 0,13 | 0,22 | -0,36 | 0,62 | 0,81 | 0,93 | 13,47 | < 0.001* | 0,15 | |

| L-PFC | -0,03 | 0,12 | 0,10 | 0,18 | -0,34 | 0,59 | 0,74 | 0,85 | 5,19 | 0.029* | 0,07 | |

| F-20 Thumb & Pinky | R-PFC | -0,02 | 0,13 | 0,07 | 0,16 | -0,20 | 0,64 | 0,72 | 0,90 | 11,65 | 0.001* | 0,14 |

| M-PFC | 0,01 | 0,14 | 0,09 | 0,18 | -0,15 | 0,70 | 0,81 | 0,92 | 4,71 | 0.032* | 0,08 | |

| L-PFC | -0,03 | 0,15 | 0,11 | 0,20 | -0,31 | 0,78 | 0,85 | 1,03 | 9,88 | 0.003* | 0,12 | |

| G-20 Single Leg Balance | R-PFC | -0,05 | 0,12 | 0,14 | 0,18 | -0,41 | 0,70 | 0,88 | 1,08 | 16,20 | < 0.001* | 0,19 |

| M-PFC | -0,07 | 0,16 | 0,18 | 0,22 | -0,37 | 0,72 | 0,95 | 1,10 | 19,10 | < 0.001* | 0,23 | |

| L-PFC | -0,08 | 0,17 | 0,15 | 0,21 | -0,45 | 0,80 | 0,87 | 1,02 | 22,71 | < 0.001* | 0,26 | |

|

Event (ID, Name) |

Pattern 1 | Pattern 2 |

F |

P |

|||

| Region | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |||

| A Upward Stretch | R-PFC | 0,20 | 1,32 | 0,62 | 1,30 | 0,78 | 0.381 |

| M-PFC | 0,48 | 1,29 | 0,41 | 1,48 | 0,12 | 0.731 | |

| L-PFC | 0,28 | 1,64 | 0,31 | 0,84 | 0,15 | 0.699 | |

| B Shoulder Stretch | R-PFC | 0,07 | 1,40 | 0,16 | 1,10 | 0,18 | 0.672 |

| M-PFC | 0,12 | 1,28 | 0,34 | 1,53 | 0,09 | 0.762 | |

| L-PFC | 0,22 | 1,30 | 0,36 | 1,48 | 0,27 | 0.601 | |

| C Elbow Circles | R-PFC | 0,31 | 0,97 | 0,12 | 1,40 | 0,30 | 0.587 |

| M-PFC | 0,98 | 1,02 | 1,07 | 1,36 | 0,42 | 0.519 | |

| L-PFC | 0,82 | 1,16 | 1,03 | 1,50 | 0,53 | 0.469 | |

| D Trunk Twist | R-PFC | 0,18 | 1,50 | 0,62 | 1,38 | 0,51 | 0.479 |

| M-PFC | 0,52 | 1,69 | 0,86 | 1,32 | 0,36 | 0.549 | |

| L-PFC | 0,55 | 1,28 | 0,94 | 1,18 | 0,66 | 0.422 | |

| E Washing Hands | R-PFC | 0,22 | 1,46 | 0,60 | 1,38 | 0,33 | 0.564 |

| M-PFC | 0,45 | 1,52 | 0,72 | 1,24 | 0,20 | 0.656 | |

| L-PFC | 0,66 | 1,32 | 0,78 | 1,40 | 0,18 | 0.678 | |

| F Thumb & Pinky | R-PFC | 0,56 | 1,65 | 0,73 | 1,25 | 0,08 | 0.778 |

| M-PFC | 0,92 | 1,14 | 0,88 | 1,06 | 0,14 | 0.707 | |

| L-PFC | 0,75 | 1,20 | 0,90 | 1,14 | 0,11 | 0.741 | |

| G Single Leg Balance | R-PFC | 0,72 | 1,29 | 0,88 | 1,19 | 0,19 | 0.662 |

| M-PFC | 0,82 | 1,42 | 1,10 | 1,32 | 0,24 | 0.626 | |

| L-PFC | 0,85 | 1,25 | 1,12 | 1,30 | 0,17 | 0.681 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).