3.1. Morphology and Microstructure of CNFs/CF

Figure 1 exhibits the morphology of CNFs/CF with various diameters at different magnifications. The as-grown CNFs are slightly entangled, forming a well-developed network with tremendous open pores. This porous 3D architecture allows the rapid transport of ions from the electrolyte to the entire surface of the CNFs/CF electrodes and makes it quickly available for electric double-layer formation. When the reaction temperature reached 800 ℃ (

Figure 1a–c), the carbon fibers of the fabrics were interconnected by CNFs, and the boundary between fiber and fiber was indistinct. The surface of the carbon fiber was covered by a thick mat of CNFs which were with an average diameter of approximately 25 nm. At this temperature, the catalysts exhibited improved catalytic performance, and the carbon sources had a higher diffusion rate, resulting in CNFs with a bigger length-diameter ratio and a smaller diameter. In this experiment, we included a control group where the reaction temperature was set at 750 ℃. As shown in

Figure 1d–f, the carbon fibers were coated with CNFs, and the average diameter of the CNFs was around 50 nm.

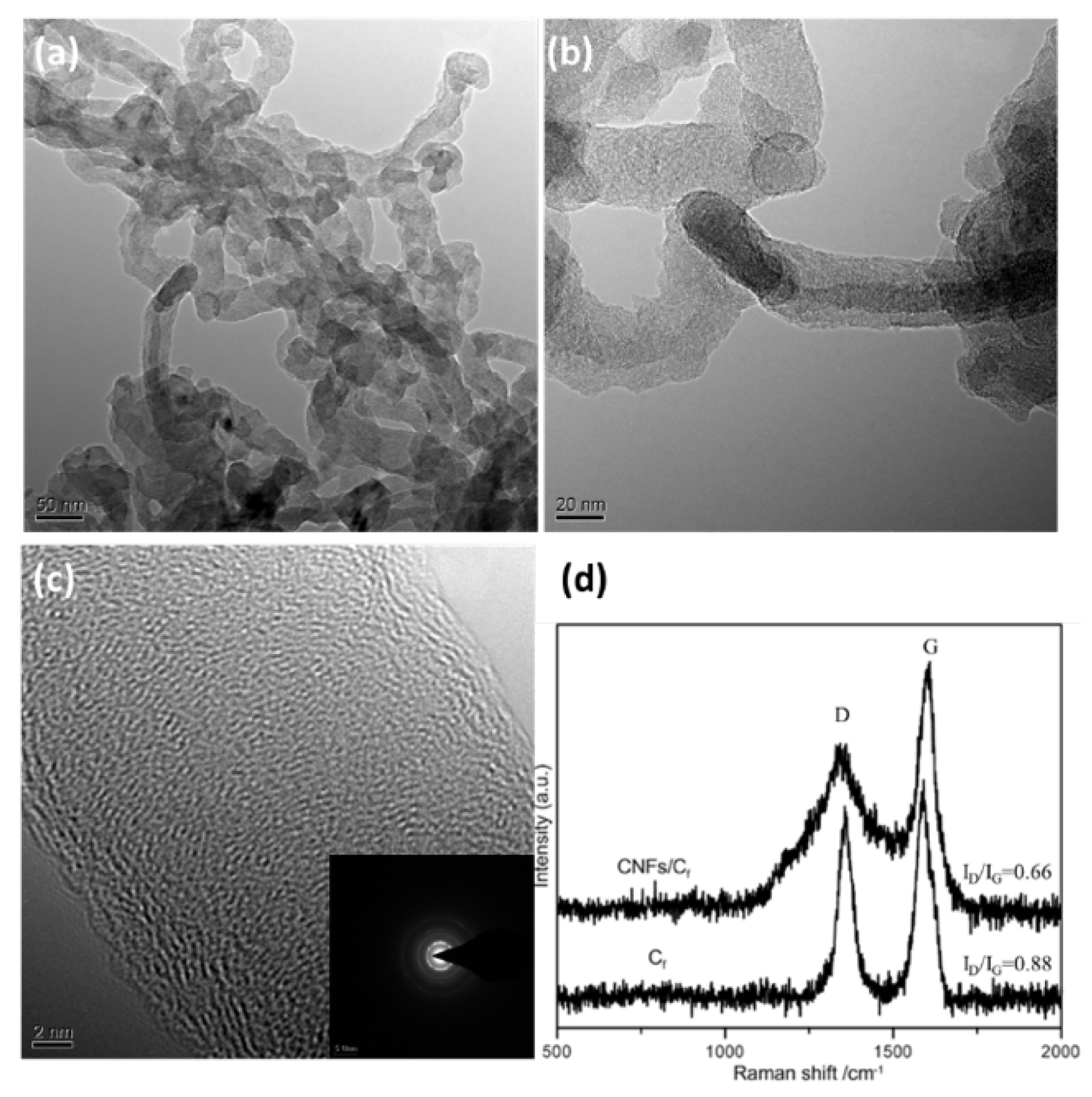

Figure 2 shows the TEM and Raman spectra of 25 nm-CNFs/CF. It can be seen from

Figure 2a,b that the CNFs were solid cylinders and the catalyst particles were located at the top.

Figure 2c exhibits the wall stripes and diffraction spots. It can be seen that the CNFs were not hollow and possessed a high degree of graphitization. The diameter of the CNFs was approximately 25 nm which was consistent with SEM observations.

Figure 2d displays the Raman spectrum of CNFs/CF. As can be seen, there were two main bands in the Raman spectrum: the D peak at around 1350 cm

-1 and the G peak at around 1580 cm

-1. The G-band corresponds to graphite mode (sp

2-bonds), while the D-band corresponds to diamond mode (sp

3-bonds), which indicates the presence of disorder or defects in the nanofiber structures. The graphitization degree of 25 nm-CNFs/CF can be determined by the I

D/I

G ratio (defined as R). The lower R-value indicates a higher degree of graphitization in the sample [

18,

19]. Specifically, the R-value for the 25 nm-CNFs/CF sample was 0.66, while that of the CF sample was 0.88. Therefore, the Raman spectra suggested that in situ formations of CNFs lead to a higher microcrystal order of carbon and an improved graphitization degree.

3.2. Electrochemical Properties of CNFs/CF

To investigate the electrochemical performance of CNFs/CF composites, cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge/discharge (GCD), and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) techniques were applied in a three-electrode system. The objective was to clarify the regulatory role of the morphology and microstructure in modulating the electrochemical performance of the composite electrodes, thereby providing experimental insights for the rational design of high-performance supercapacitor electrode materials.

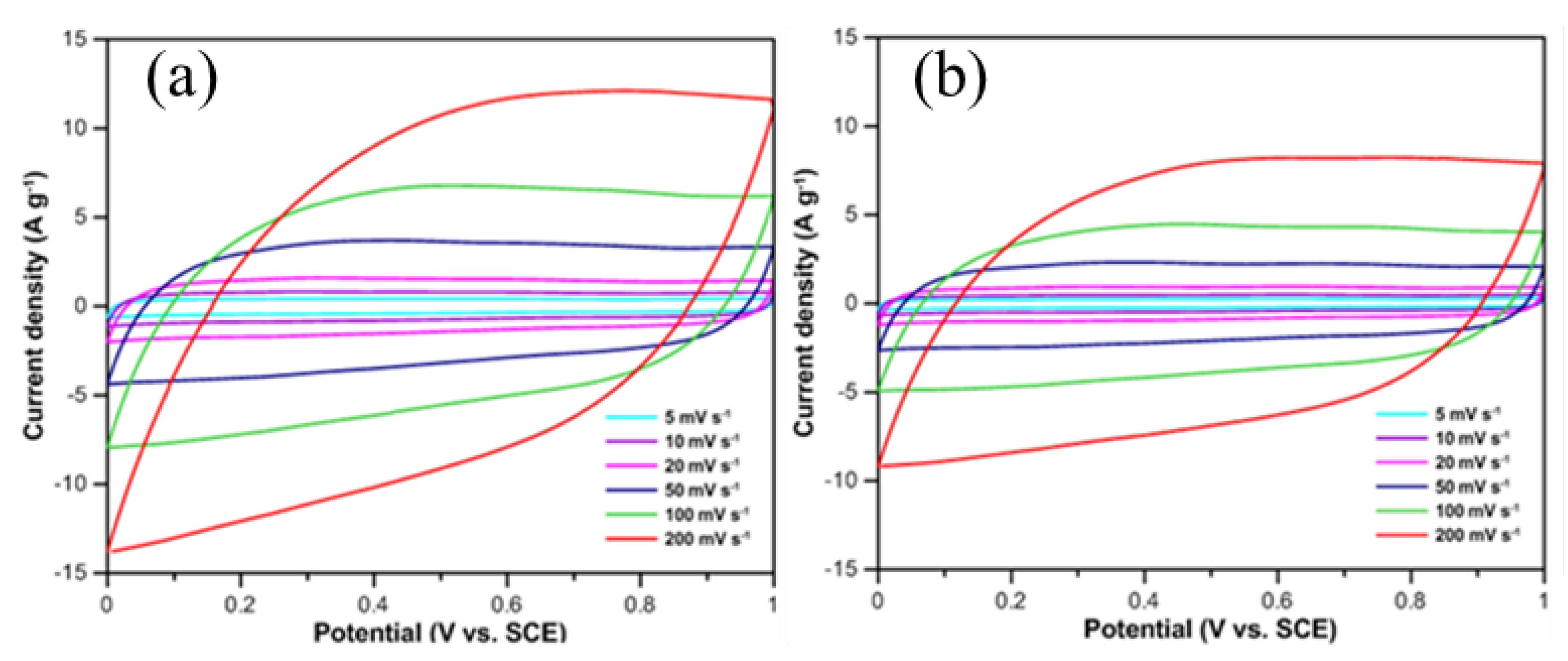

Figure 3 displays the CV curves and specific capacitance of CNFs/CF composites with different diameters under varying scan rates. The potential window in this test ranged from 0 to 1 V, and the scanning rates were set at 5 mV/s, 10 mV/s, 20 mV/s, 50 mV/s, 100 mV/s, and 200 mV/s, respectively. Theoretically, an ideal electric double-layer capacitor (EDLC) exhibits a CV curve with a regular rectangular shape, which arises from the instantaneous formation of an electric double layer at the electrode-electrolyte interface and the rapid stabilization of current upon scan direction reversal. However, deviations from this ideal morphology are commonly observed in practice, due to electrode internal resistance, surface functional groups, and other interfacial effects.

Figure 3a,c demonstrate that the CV curves of CNFs/CF composites with both diameters exhibit symmetric parallelogram profiles, and no distinct redox peaks are detected across the entire potential window. This observation confirms that the energy storage mechanism of the CNFs/CF electrodes is dominated by electric double-layer capacitance. The electrolyte ions can be rapidly and uniformly adsorbed onto the CNFs/CF surface to form a stable electric double layer. Upon instantaneous reversal of the scan direction, the current promptly inverts and stabilizes, demonstrating excellent electrochemical reversibility of the CNFs/CF composites. The scan rate exerts a significant influence on the current intensity and enclosed area of the CV curve, which are directly correlated with the specific capacitance of the electrode material, and experimental results indicate that with increasing scan rate, the current of the CV curves for both CNFs/CF composites increases proportionally, the enclosed area expands synchronously while the curve morphology remains essentially unchanged, which is an indication of the good rate capability of the materials.

The specific capacitance (C, F g

-1) can be calculated from the CV curves based on equations (1):

where m is the mass of the CNFs, v is the potential scan rate, (Va-Vc) is the sweep potential window, and I (V) is the voltametric current on CV curves. The calculated results are summarized in

Table 1.

As exhibited in

Table 1, the specific capacitances of the two CNFs/CF composites exhibit a decreasing trend with the elevation of scan rate. Specifically, at a scan rate of 5 mV/s, the specific capacitances of the 20 nm-diameter and 50 nm-diameter CNFs/CF composites attain 77.0 F/g and 46.8 F/g, respectively; when the scan rate is increased to 200 mV/s, their specific capacitances decrease to 36.3 F/g and 28.3 F/g, respectively. This variation tendency is highly consistent with the energy storage mechanism of EDLCs. At lower scan rates, the electrolyte solution is afforded sufficient time to interact with the electrode surface, which facilitates the complete formation of the electric double layer and thereby results in a higher specific capacitance. In contrast, at higher scan rates, the diffusion rate of electrolyte ions is unable to keep up with the rate of voltage change, leading to the incomplete formation of the electric double layer and a subsequent reduction in specific capacitance. Furthermore, under the same scan rate condition, the CNFs/CF composite with a smaller diameter presents a larger enclosed area in its cyclic voltammetry (CV) curve, which is indicative of more excellent capacitive performance. Experimental results demonstrate that the 25 nm-CNFs/CF composite exhibits superior energy storage performance. Furthermore, the variation relationship between specific capacitance and scan rate further enables the analysis of the capacitance retention characteristics of the electrode materials. The 50 nm-CNFs/CF retained a higher capacitance, approximately 60.47%, at 200 mV/s compared to its capacitance at 5 mV/s, as opposed to 47.14% for 25 nm-CNFs/CF. This high capacitance retention rate of the 50 nm-CNFs/Cf composite can be ascribed to the relatively larger pore size of its constituent CNFs. Specifically, the larger pore structure enables more effective electrolyte penetration even at high scan rates, which in turn ensures the efficient utilization of the electrode's surface area and ultimately contributes to the higher capacitance retention.

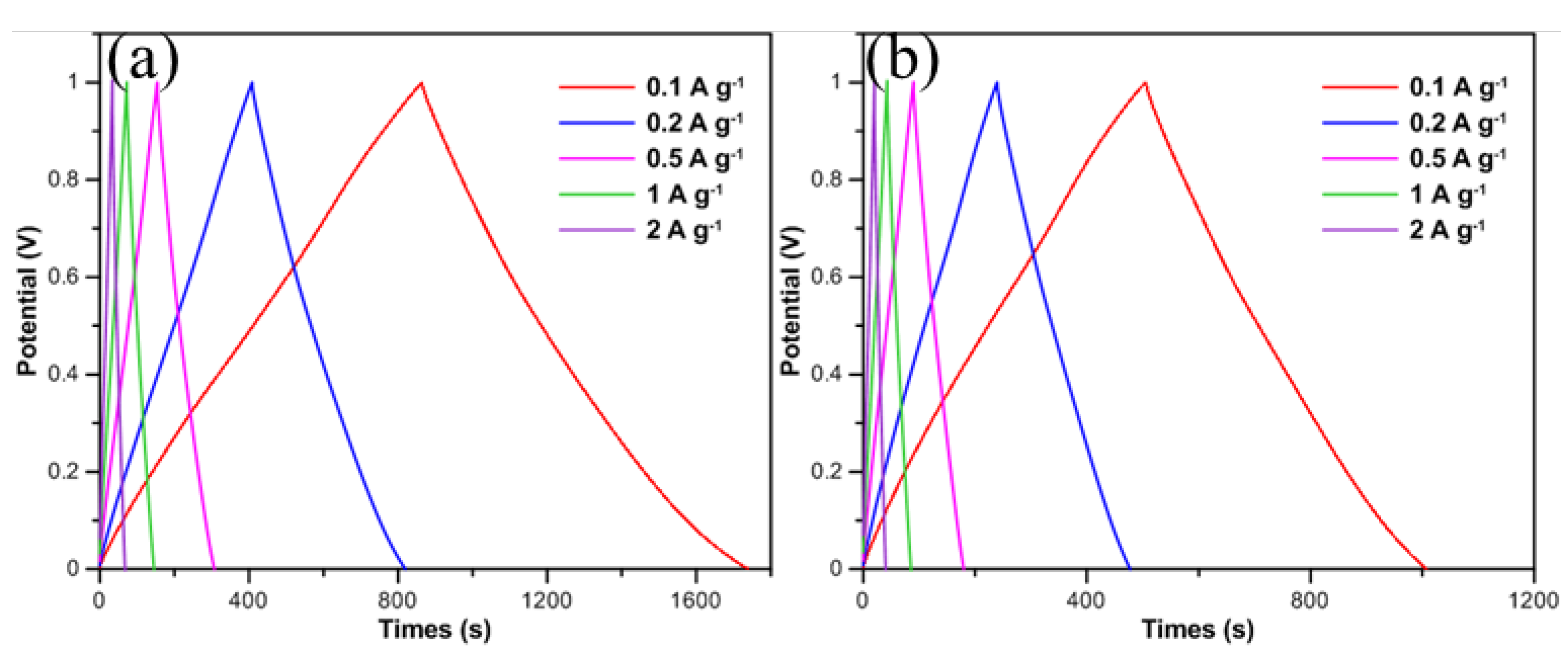

Figure 4 shows the galvanostatic charge-discharge (GCD) curves of CNFs/CF with different diameters under various scan rates. GCD measurements were conducted with current densities ranging from 0.1 to 2 A/g, and the voltage was limited to 0 and 1 V. From the perspective of electrochemical theory, the GCD curve of an ideal supercapacitor should exhibit a standard isosceles triangular shape, which is a direct reflection of its charge-discharge efficiency approaching 100%. However, due to multiple factors in practical test systems, a perfect GCD curve is difficult to achieve. An abrupt potential drop commonly occurs at the initial stage of constant current discharge, which is defined as the IR drop. Previous studies have confirmed [

20] that the IR drop attributed to the resistance of electrolytes, the contact resistance between carbon and the current collector, and the inner resistance of ion migration in carbon micropores. Among these, the internal resistance of ion migration within carbon micropores accounts for the highest proportion of the total IR drop. It is worth noting that smaller IR drop indicates lower internal resistance of the electrode material.

Figure 4 exhibit the GCD curves of 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF, respectively. It can be seen that the shapes of the curves which indicated superior reversible faradic reactions were close to the theoretical isosceles triangle curve with basically linear slopes, exhibiting good symmetry at every current density. Meanwhile, only a slight IR drop appears at the initial stage of the discharge curves of both composites, which indicates that the CNFs/CF composites have low internal resistance properties, reflecting the formation of a good interfacial bonding between CNFs and the CF substrate, and the device as a whole exhibits excellent electrical conductivity and ion diffusion/transport capabilities. It should be particularly noted that the discharge time of the CNFs/CF composites is slightly longer than the charge time under all test conditions. Taking the test results of 50 nm-CNFs/CF in

Figure 4b at a current density of 0.1 A/g as an example, the charge time is 505.6 s, while the discharge time is 502 s. This difference may be related to the kinetic characteristics of the ion adsorption-desorption process on the electrode surface. Further analysis shows that with the increase of current density, the specific capacitances of both 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF gradually decrease. This regularity indicates that the ion accessibility within the CNFs layer is the dominant factor leading to capacitance degradation. At high current densities, electrolyte ions cannot fully diffuse into the microporous structure of the electrode material within a short time, resulting in reduced utilization of the electrode surface and ultimately manifesting as a decrease in specific capacitance. Overall, both CNFs/CF composites exhibit stable capacitance output characteristics and good electrochemical reversibility when used as supercapacitor electrode materials. This conclusion is highly consistent with the analysis results of cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests, verifying the reliability of the characterization results.

The specific capacitance (C, F/g) can be calculated from the charge/discharge curves based on Equation (2):

where m represents the mass of the CNFs, I is the applied current, and dV/dt is the slope of the discharge curve after the IR drop.

Table 2 summarizes the calculated specific capacitance results of CNFs/CF composites with different diameters under various current densities. As can be seen from the data in

Table 2, at a low current density of 0.1 A/g, the specific capacitances of 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF reach 87.5 F/g and 50.2 F/g, respectively. When the current density increases to 1 A/g, the specific capacitances of the two materials are 72.8 F/g and 42.8 F/g, with corresponding capacitance retentions of 83.20% and 85.26%, respectively. When the current density further increases to 2 A/g, the specific capacitances of 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF still maintain at 67.6 F/g and 40.0 F/g, demonstrating good rate stability.

The maximum specific capacitances of 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF were determined to be 87.5 F/g and 50.2 F/g, respectively. A prior study [

4] systematically investigated the structural and electrochemical properties of VACNT/CF and ECNT/CF composites, where the maximum specific capacitances of 50 nm-VACNT/CF and 50 nm-ECNT/CF were reported as 75 F/g and 42 F/g, respectively. To elucidate the key factors governing the specific capacitance of carbon-based composite electrodes, comparative analyses were conducted between the materials synthesized in this work and those reported in the literature [

4].

A comparison of the specific capacitance values of 25 nm-CNFs/CF as presented in this study reveals that the maximum specific capacitance of 25 nm CNFs/CF can reach 87.5 F/g, whereas that of 50 nm- VACNT/CF is only 75 F/g. This result indicates that the outer diameter exerts a significant influence on the specific capacitance. For the VACNT/CF electrode system, the VACNTs can only grow along certain directions [

22,

23]. Directional growth constraints limit the expansion of the surface area, as evidenced by lesser specific capacitance than irregularly porous 25 nm-CNFs/CF.

To further clarify the role of structural characteristics in determining capacitance performance, a comparative evaluation of the maximum specific capacitances between 50 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-ECNT/CF electrodes was performed, which demonstrates that the unique hollow structure of CNTs does not exert a substantial effect on enhancing specific capacitance. It is widely recognized that the most prominent structural distinction between CNTs and CNFs resides in the presence or absence of a characteristic hollow tubular architecture. Theoretically, the intrinsic tubular structure of CNTs should endow them with a larger specific surface area and thus superior specific capacitance relative to CNFs. However, several factors mitigate this theoretical advantage: firstly, the interlayer spacing of multi-walled CNTs (MWCNTs) is typically smaller than the ionic radius of adsorbing species, which inhibits ion penetration into the interlayer regions and thereby eliminates capacitance contribution from these domains [

9]; secondly, the inner channels of CNTs are often underutilized due to size-dependent limitations on ion infiltration, offsetting the potential capacitance gains associated with their hollow structure; additionally, microstructural defects and growth mechanisms of the nanomaterials can modulate the internal resistance of the electrode, a parameter that is closely correlated with the measured specific capacitance. In the present study, the as-synthesized CNFs exhibit a high degree of graphitization (

Figure 2c), and the tip-growth mechanism adopted during their fabrication facilitates the formation of robust C-C covalent bonds at the interface between the CNFs and the carbon fiber current collector. Consequently, despite the absence of a distinct hollow structure, the 50 nm-CNFs/CF electrode demonstrates a marginally higher specific capacitance than 50 nm-ECNT/CF electrode.

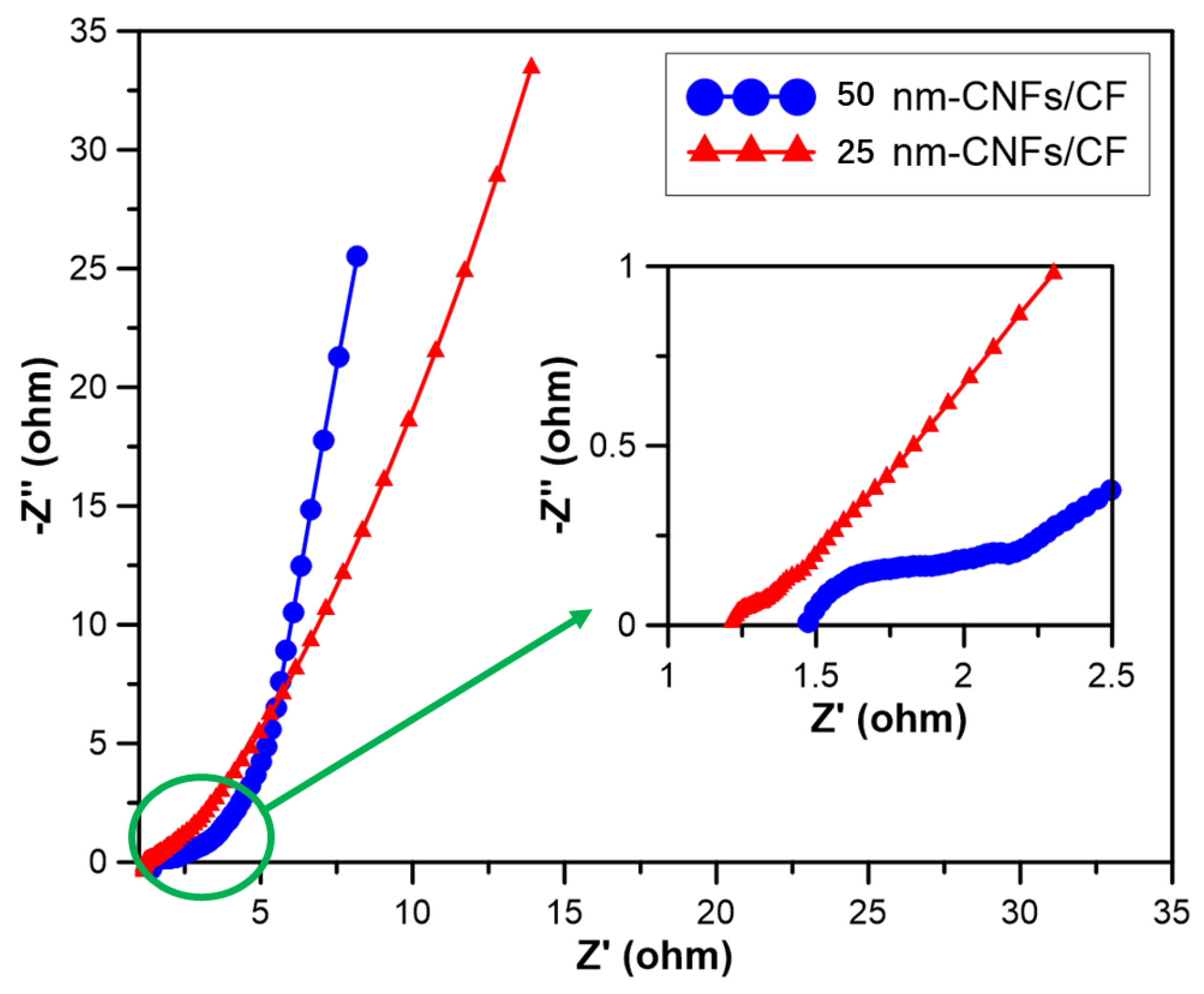

To further understand the charge transfer and electrochemical kinetics of the electrodes, The EIS measurements were conducted in the frequency from 10 MHz to 100 kHz with a perturbation amplitude of 5 mV versus the open circuit potential. The resulting Nyquist plots and a partially enlarged view focusing on the high-frequency region of the 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF composites are displayed in

Figure 5.

The Nyquist plots comprise (i) the high frequencies region. When a high-frequency signal is applied to the ideal supercapacitor, the curve in this zone should be perpendicular to the horizontal coordinate. However, owing to the influence of Faraday reactions occurring on the electrode surface, a typical observation here is a semicircle. Therefore, this region serves to characterize the Faraday impedance of the electrode materials. The size of the semicircle is related to the morphology and conductivity of the material, the diameter of the semicircle corresponds to the charge transfer resistance (R

ct) at the electrode/electrolyte interface, the intersection of the X-axis and semi-circular curve can characterize the electrode resistance (R

t) of the material which is mainly related to the electrolyte resistance (R

s), the internal resistance of the active material (R

m) and the contact resistance (R

c) between the collector and the electrolyte. (ii) the medium frequencies region, also known as the Warburg region. It usually appears a straight line with a slope of 45◦ which corresponds to semi-infinite Warburg impedance (R

w). By extending the line in the reverse direction, the intersection of the X-axis can characterize the value of R

w. (iii) the low frequencies region. (iii) the very low frequencies region. In this region, it presents a vertical line which is due to the accumulation of ions at the bottom of the pores of the electrode material. The line's proximity to being parallel to the Y-axis indicates the proximity to an ideal capacitor [

21].

Figure 5 illustrates an incomplete semicircle in the high frequencies region for both CNFs/CF composites. It indicated that the CNFs/CF electrodes exhibited low resistance between CNFs and CF. Compared with 25 nm-CNFs/CF, the semicircle-wrapped area of 50 nm-CNFs/CF was larger. Analyzing the Nyquist plots in the high-to-medium frequencies region, the charge transfer resistances (Rt) for 25 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF composites, obtained from the x-intercept, are measured at 1.2 Ω and 1.4 Ω, respectively. In the medium-frequency region, the value of R

w of 20 nm-CNFs/CF and 50 nm-CNFs/CF composites were found to be 1.25 Ω and 1.8 Ω, respectively. At low frequencies, the plots of 50 nm-CNFs/CF took on an almost vertical line, indicating an ideal capacitive behavior with low diffusion resistance. Conversely, the 25 nm-CNFs/CF electrodes exhibited a relatively low slope. To summarize, the results showed that the resistance of 25 nm-CNFs/CF was smaller, and its energy storage characteristic was better. On the other hand, 50 nm-CNFs/CF approached an ideal capacitor, displaying higher capacitance retention. These findings aligned with the results obtained from CV tests.