1. Introduction

Net Primary Productivity (NPP), defined as the amount of carbon fixed by plants through photosynthesis and stored as biomass, is a key indicator of ecosystem health, carbon sequestration, and agricultural productivity [

1]. It serves as a critical metric for assessing global ecological responses to climate change and supports sustainable development planning [

2]. Exploring changes in NPP and grasping their underlying mechanisms are pivotal in unveiling the sustainability of terrestrial ecosystems amidst natural, environmental, and anthropogenic shifts [

3,

4].

Current evidence indicates that topographical factors, encompassing elevation, slope, aspect, and hydrological conditions, exert both direct and indirect influences on the growth environment and ecological niche of vegetation, thereby impacting NPP [

5]. Climate change can also result in decreased biodiversity and deteriorating soil quality, which can have additional repercussions on NPP within ecosystems [

6]. Furthermore, forests and grasslands typically manifest elevated NPP levels, whereas croplands and urban zones often present relatively diminished levels. Varied land use types and shifts in land use practices can lead to distinct effects on NPP [

7]. Moreover, intensive land cultivation and excessive grazing within agricultural regions can lead to land degradation and diminished vegetation, thereby causing a decline in NPP levels [

8]. Research findings also have demonstrated a deceleration in the growth pace of NPP in high-latitude regions, and tropical areas could witness a decline in NPP due to extreme climatic events like droughts and heat waves [

9]. Moreover, the influence of human activities, including nitrogen deposition, land use alteration, and greenhouse gas emissions, on NPP is on the rise [

10].

Investigating the factors that influence NPP is key to understanding how ecosystems respond and adapt, offering a scientific foundation for safeguarding ecological systems and promoting sustainable development [

9]. The influence of NPP arises from various factors, including climate, soil nutrients, vegetation types, land use, and others [

1], with temperature and precipitation holding notable sway over NPP, and their correlation frequently displays non-linear patterns [

7]. Although previous studies have offered valuable insights into the drivers of NPP, there remains a significant gap in understanding the marginal contributions of these factors to variations in NPP.

The Sahel region is a semi-arid zone spanning northern Africa which comprises various land cover categories and complex ecosystems and is known to be sensitive to environmental change [

11,

12]. Environmental degradation, rainfall variability, and land-use pressures threaten food security and livelihood resilience in this region [

13,

14]. Recent decades have witnessed increasing climatic variability and extremes in the Sahel, characterized by unpredictable rainfall patterns, rising temperatures, and prolonged drought periods [

15,

16]. Such climate-driven disturbances directly impact vegetation dynamics, land productivity, and ecological resilience, exacerbating socioeconomic instability and vulnerability to disasters such as drought and famine [

16]. Given these circumstances, enhancing predictive insights into NPP variation is not only ecologically critical but also vital for disaster resilience and strategic resource management [

7].

Traditional NPP modelling often relied on global-scale regression methods or empirical models, which assume spatial stationarity and linear relationships between vegetation productivity and environmental predictors [

17]. While these models offer insight into general trends, they typically fail to adequately capture localised variability among variables, limiting the precision and applicability of their predictions to localised context, particularly in regions with complex climate-vegetation interactions like Sahel [

18]. Addressing this limitation, geographically weighted regression (GWR) has emerged as a powerful approach that explicitly models spatial variability by allowing regression parameters to vary geographically [

19]. GWR improves predictive performance by accounting for spatial non-stationarity, that is, the variability of statistical relationships across space, thus providing more nuanced and locally relevant predictions of NPP [

17,

20,

21,

22]. However, despite its proven advantages over conventional regression methods, GWR alone still faces limitations, notably in modelling highly nonlinear, complex interaction typical of ecological data [

23]. To overcome these challenges, the integration of geographic weighting into machine learning algorithms offers a promising solution. Recent developments, such as Geographically Weighted Random Forests (GWRF) and Geographically Weighted Neural Networks (GWNN), have demonstrated improved accuracy in spatial predictions by modelling complex nonlinear relationships and accounting for spatial heterogeneity [

24,

25]. However, their application in ecological prediction, particularly within the context of disaster-prone regions such as the Sahel, remains substantially underexplored.

This study addresses this gap by investigating the potential of geographically weighted statistical and machine learning methods (GWR, GWRF, GWNN) for accurately predicting NPP within the eastern Sahel region, an area marked by acute environmental vulnerability, socio-economic instability, and heightened disaster risks [

14]. Specifically, this study aims to (1) examine spatial variability and relationships between key environmental drivers (temperature, rainfall, soil moisture, elevation) and NPP, (2) implement GWR alongside GWRF and GWNN models to capture spatial and nonlinear dynamics effectively, and (3) evaluate and compare the predictive performance of GWR, GWRF, and GWNN. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 describes the principles of GWR, GWRF, and GWNN, along with datasets used.

Section 3 presents results, while

Section 4 provides discussion and conclusions based on the study’s findings.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

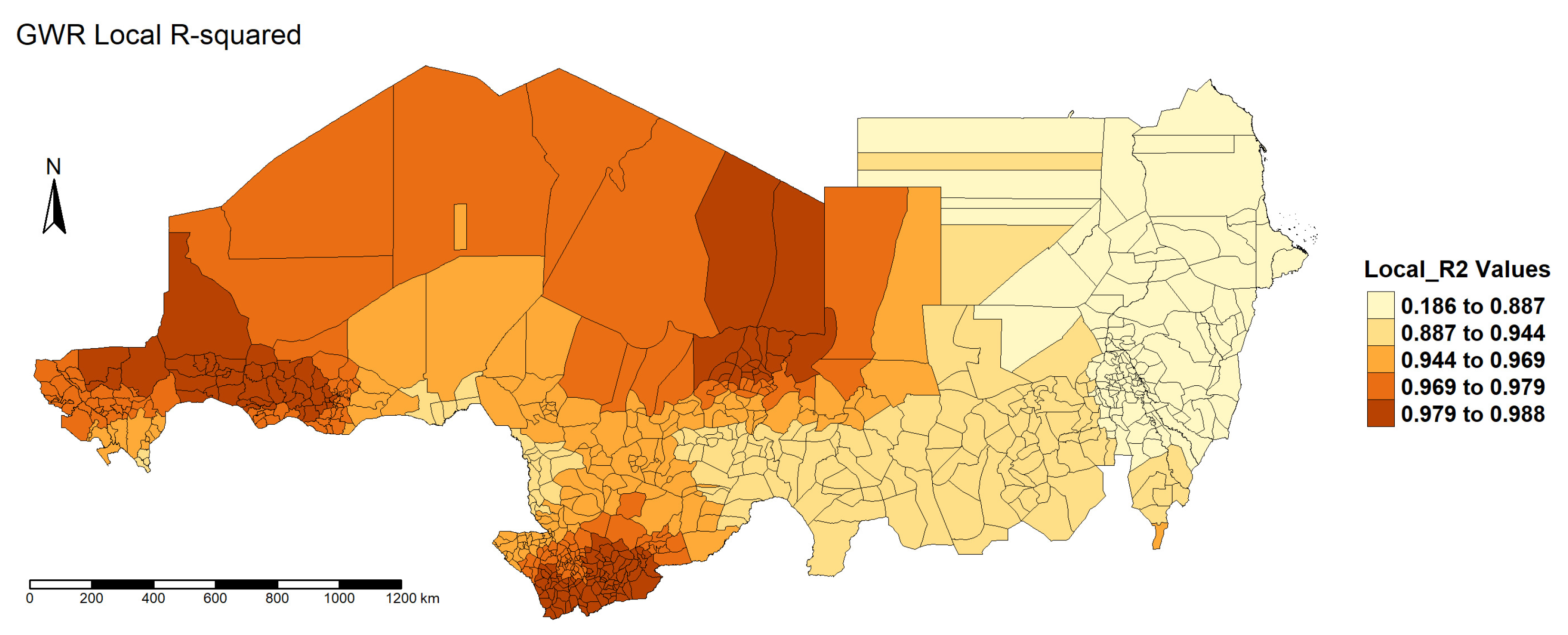

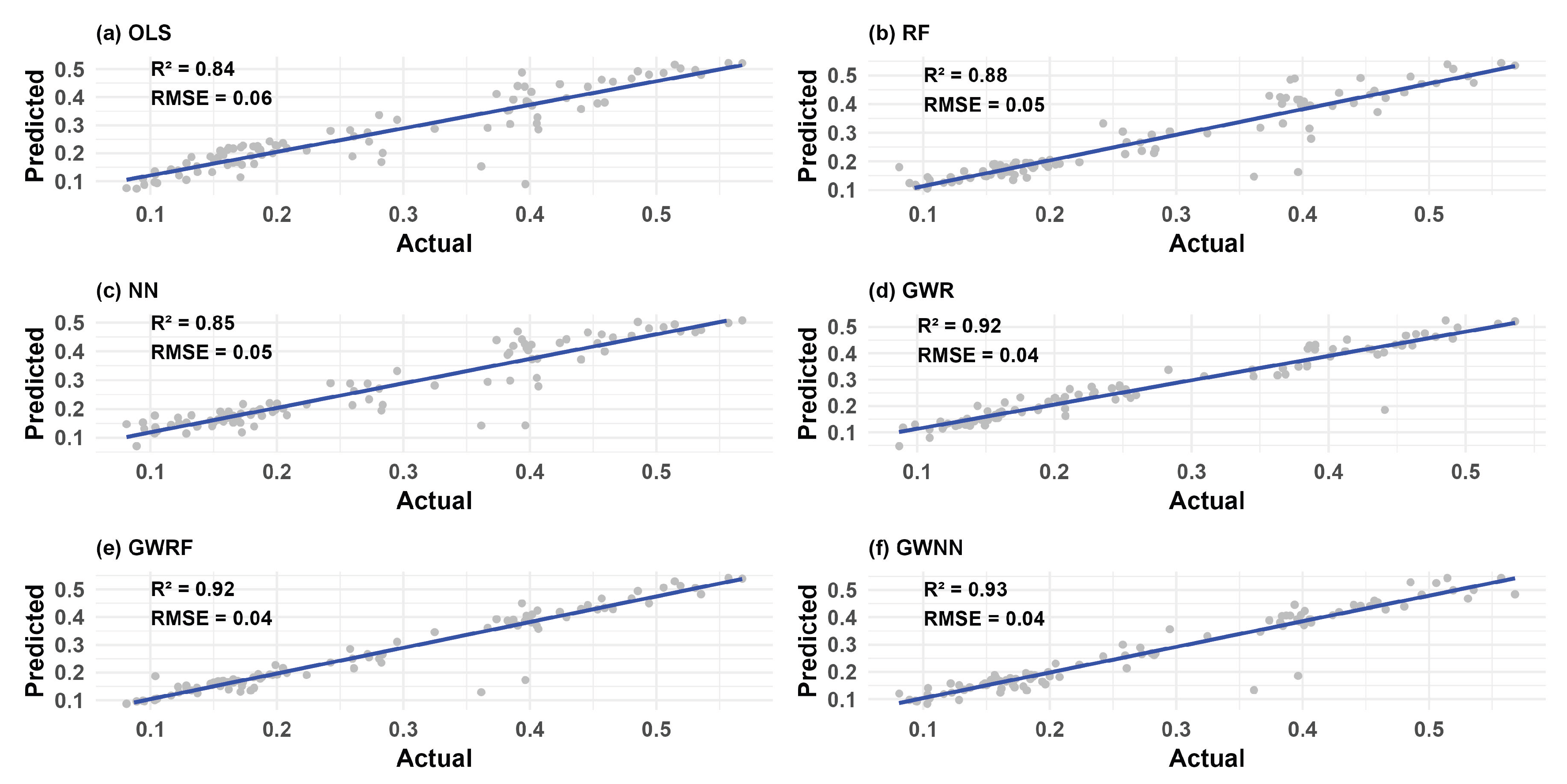

This study investigated the effectiveness of spatially adaptive regression and machine learning models, specifically GWR, GWRF, and GWNN, in predicting NPP within the Eastern Sahel. The primary goal was to determine how effectively these methodologies capture spatial heterogeneity and nonlinear relationships between NPP and various environmental predictors, including rainfall, temperature, soil moisture, and elevation. Each of the three geographically weighted models showed superior predictive performance relative to the global OLS baseline. Notably, the GWNN model achieved the highest (0.9360), followed closely by GWRF (0.9308) and GWR (0.9207). These findings validate the potential of integrating geographic weighting with nonlinear learning in ecological modelling.

The improved predictive performance of spatially weighted models over the global OLS model indicates the presence of spatial non-stationarity in the relationship between NPP and its climatic and topographic influences. The GWR model, which allows for local variation in parameter estimates, demonstrated significant enhancements over the global baseline, consistent with findings from other environmental studies where spatial regression captured region-specific effects more accurately than global models [

19,

61]. The additional performance gains observed in GWRF and GWNN suggest that incorporating nonlinear learning into spatial frameworks yields further benefits, particularly in modelling complex ecological processes. This is in agreement with emerging studies that apply spatially weighted machine learning techniques to land surface modelling and environmental prediction [

62,

63]. The results underscore that NPP is influenced not only by the intensity of predictors but also by spatial context, which linear global models do not fully capture.

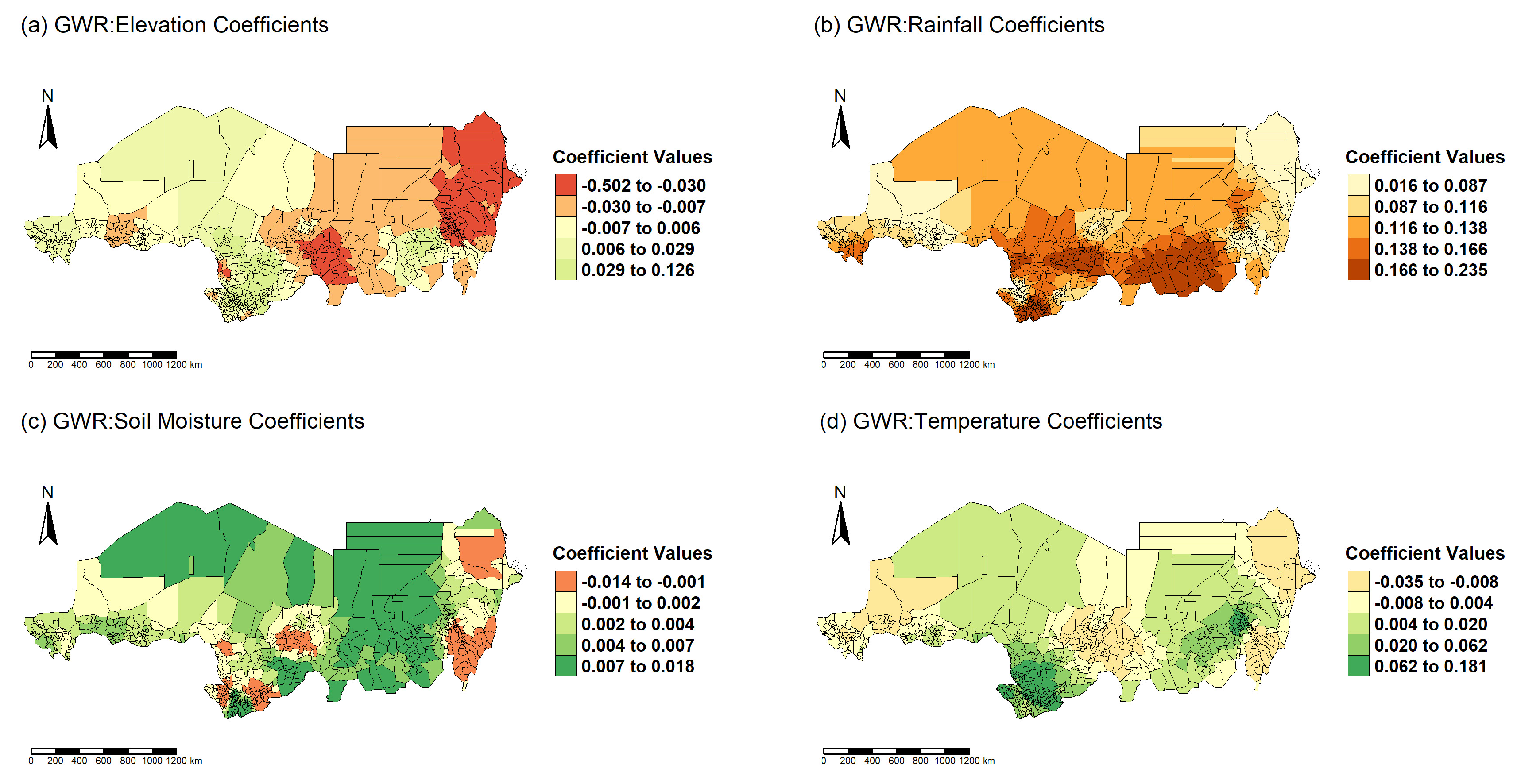

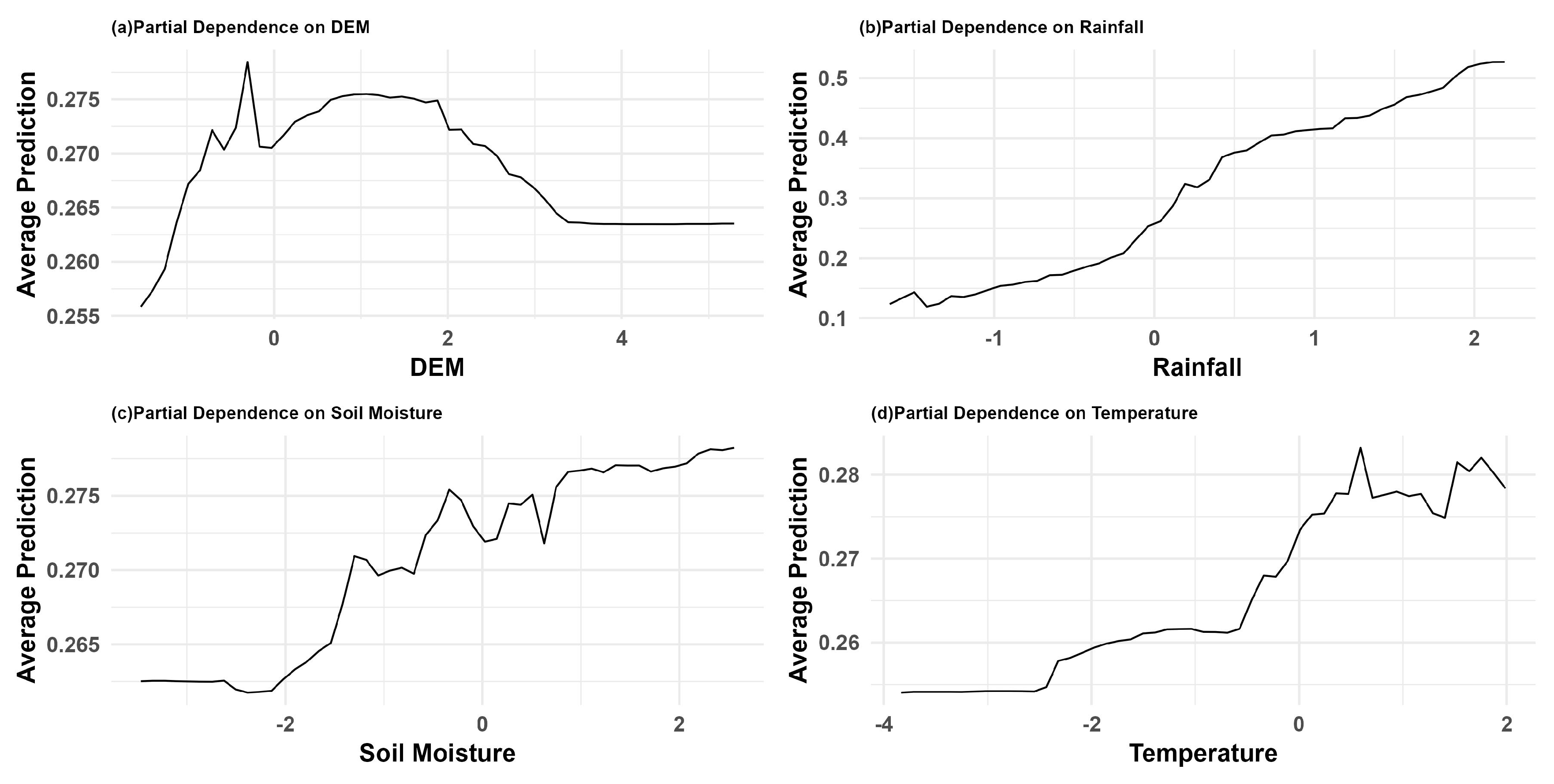

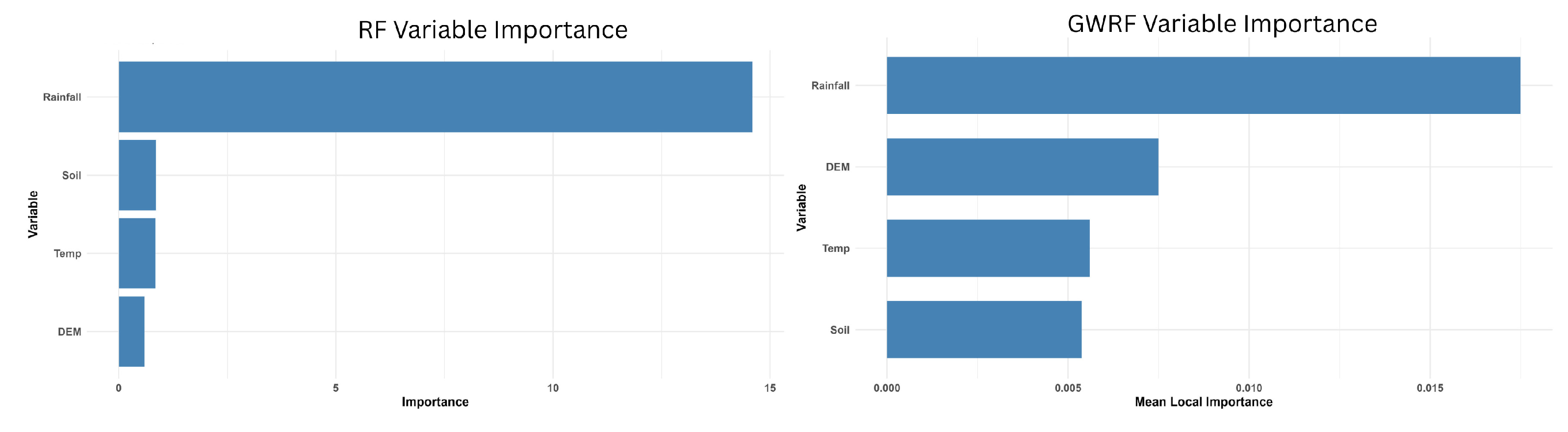

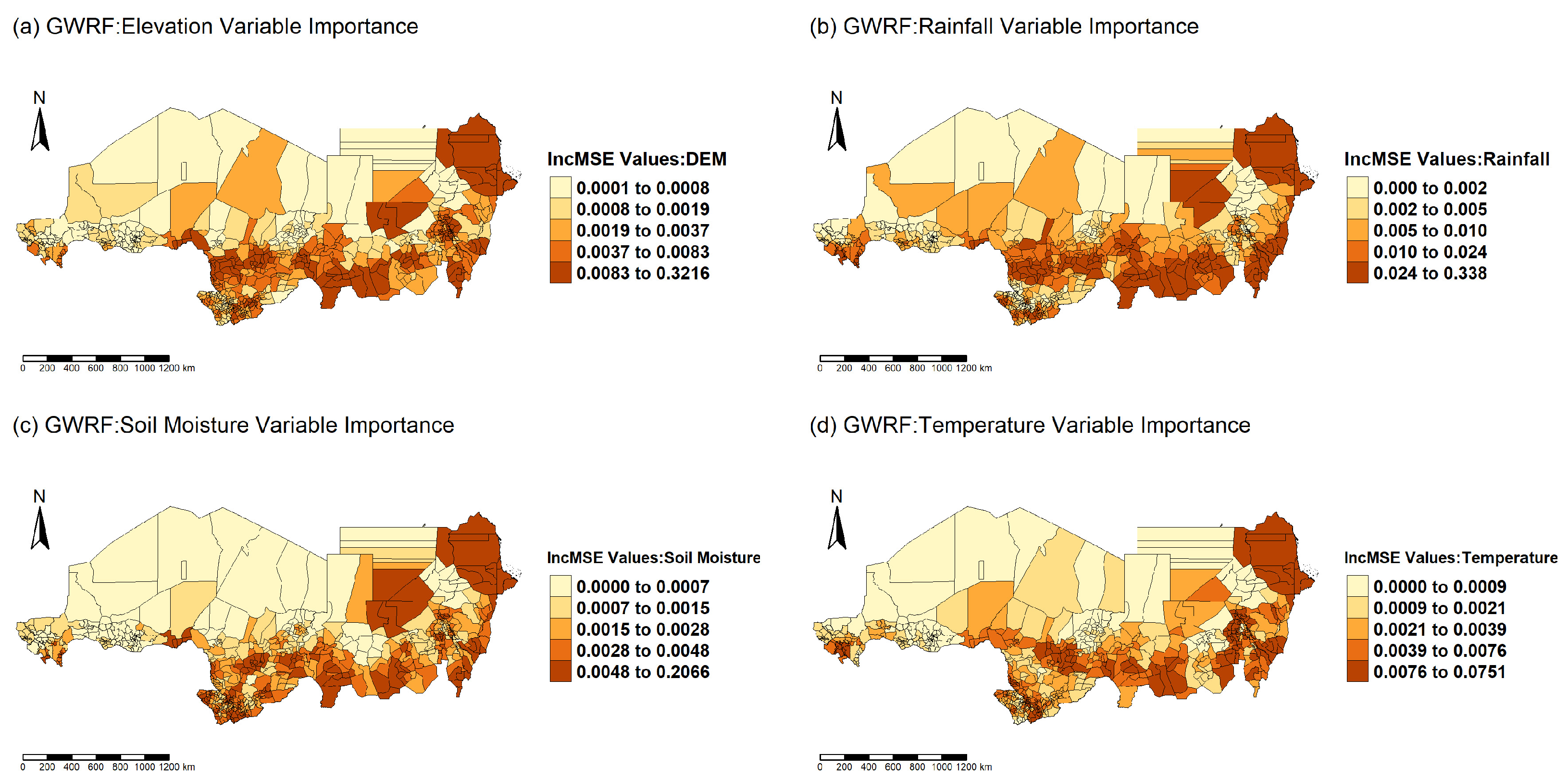

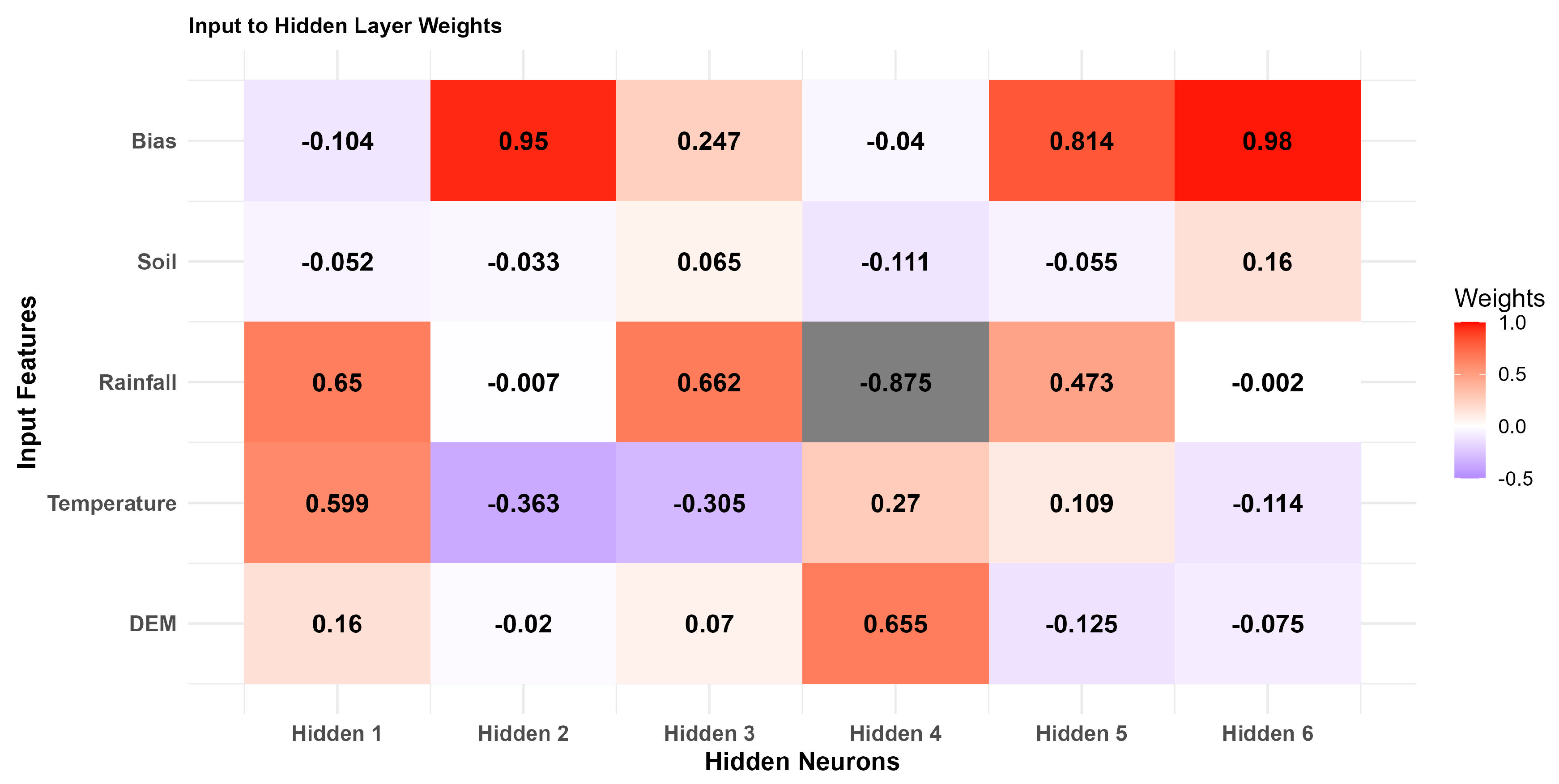

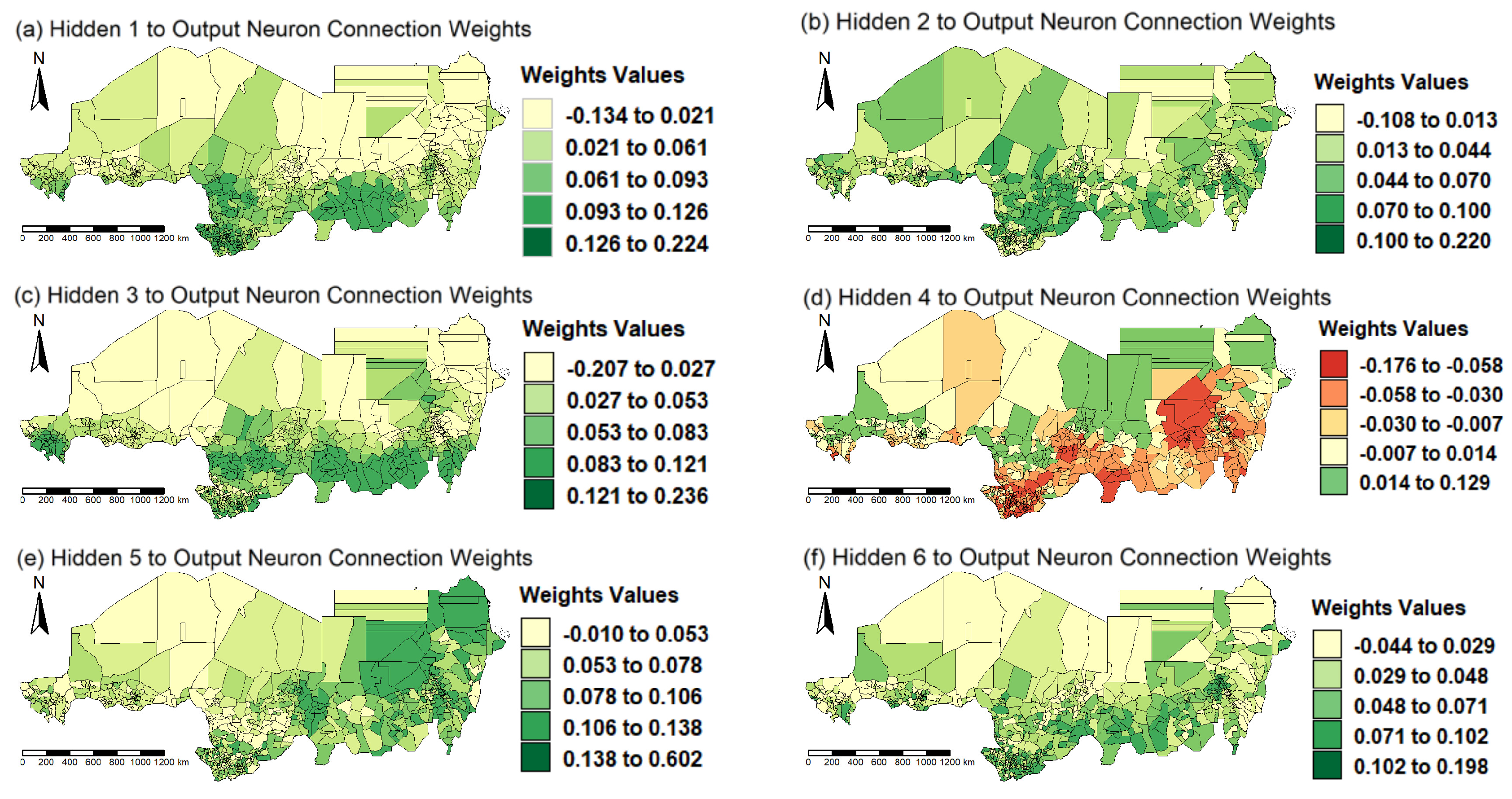

The spatial variation in predictor significance and model coefficients has revealed complex ecological dynamics across the Eastern Sahel. Rainfall has consistently emerged as the most significant driver of NPP across all models, particularly in southern Chad and parts of Sudan where vegetation productivity is closely linked to precipitation patterns. This observation is consistent with prior studies that highlight rainfall as a primary limiting factor in semi-arid ecosystems [

64,

65]. The influence of elevation was more variable, with negative associations in the eastern highlands of Sudan and positive or neutral effects in flatter regions, suggesting local topographic modulation of microclimates and vegetation patterns. Temperature and soil moisture showed weaker and more spatially inconsistent effects, reinforcing the importance of modeling their interactions within local ecological contexts. The ability of GWRF and GWNN to reveal these spatially heterogeneous relationships provides a methodological advantage over global models that assume uniformity in predictor influence.

This study presents a groundbreaking contribution to spatial ecological modelling by employing and comparing geographically weighted versions of Random Forests and Neural Networks, which are methods that have not been fully utilised in environmental productivity assessments. Although GWR has been widely applied in spatial analysis, few studies have extended geographically weighted frameworks to nonlinear models capable of capturing both spatial non-stationarity and complex interactions among predictors. The integration of machine learning within a spatially weighted structure, as implemented in GWRF and GWNN, demonstrates that predictive models can retain local interpretability while accommodating nonlinear ecological behaviours. Notably, the GWNN model achieved the highest overall performance, underscoring its potential as a flexible and powerful tool for regional-scale environmental prediction. By adapting these methodologies to the data-scarce, climate-sensitive context of the Eastern Sahel, this study also addresses a geographic gap in the literature, where predictive spatial modelling of NPP remains limited.

The findings present significant implications for both scientific modelling and the practical management of land in arid and semi-arid ecosystems. By improving the spatial accuracy of NPP predictions, geographically weighted machine learning models can facilitate more targeted monitoring of vegetation productivity, land degradation, and ecological vulnerability. These tools are particularly valuable in regions such as the Sahel, where climate variability, food insecurity, and resource pressures intersect. Moreover, the capacity to quantify spatially diverse influences of environmental drivers enables policymakers and practitioners to create interventions that are tailored to specific contexts, such as regionally focused land restoration strategies or climate adaptation plans. From a modelling standpoint, this study highlights the effectiveness of combining local weighting schemes with nonlinear learning to address spatial complexity, an approach that could be applied to other environmental indicators beyond NPP.

By integrating GWNN and GWRF into ecological modelling, this research addresses a deficiency in the realm of spatial machine learning applications, illustrating the importance of these methodologies in recognising region-specific productivity drivers. Additionally, their implementation in a climate-vulnerable area emphasises their practical applicability for land monitoring and adaptation planning. Despite the models achieving strong spatial fits, the analysis was temporally static, thereby limiting the understanding of seasonal dynamics. The inclusion of further variables, like land cover or anthropogenic influences, could improve the precision of predictions. However, the synergy of spatial diagnostics and machine learning presents a transferable framework for ecological forecasting. Future research should aim to include spatio-temporal modelling and uncertainty quantification, as well as delve into explainable AI to enhance model transparency. Such innovations could significantly advance predictive ecology and provide insights for data-driven approaches to combat land degradation and environmental hazards.

Figure 2.

Spatial Distribution of NPP in Chad, Niger, and Sudan (2019–2021).

Figure 2.

Spatial Distribution of NPP in Chad, Niger, and Sudan (2019–2021).

Figure 3.

Descriptive maps of NPP and its predictors.

Figure 3.

Descriptive maps of NPP and its predictors.

Figure 4.

Map of OLS Residual Distribution.

Figure 4.

Map of OLS Residual Distribution.

Figure 5.

Maps of the GWR Coefficient Estimates.

Figure 5.

Maps of the GWR Coefficient Estimates.

Figure 6.

Map of Values from the GWR Model.

Figure 6.

Map of Values from the GWR Model.

Figure 7.

Visualising Nonlinear Effects of Covariates with PDPs.

Figure 7.

Visualising Nonlinear Effects of Covariates with PDPs.

Figure 8.

Global Feature Importance (RF) and Mean Local Feature Importance (GWRF) Based on IncMSE.

Figure 8.

Global Feature Importance (RF) and Mean Local Feature Importance (GWRF) Based on IncMSE.

Figure 9.

Local Feature Importance Maps.

Figure 9.

Local Feature Importance Maps.

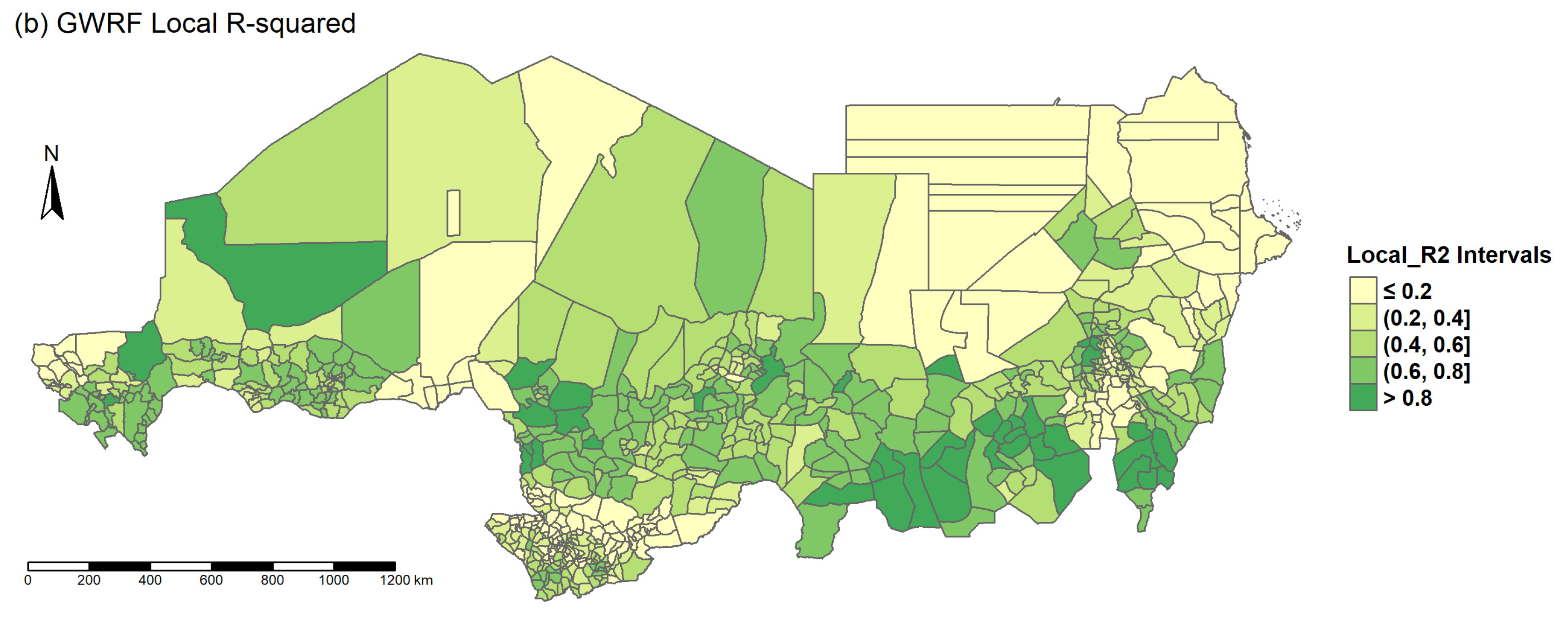

Figure 10.

Map of Values from the GWRF Model.

Figure 10.

Map of Values from the GWRF Model.

Figure 11.

Input to Hidden Layer Weights.

Figure 11.

Input to Hidden Layer Weights.

Figure 12.

GWNN Connection Weights (Hidden to Output Neurons).

Figure 12.

GWNN Connection Weights (Hidden to Output Neurons).

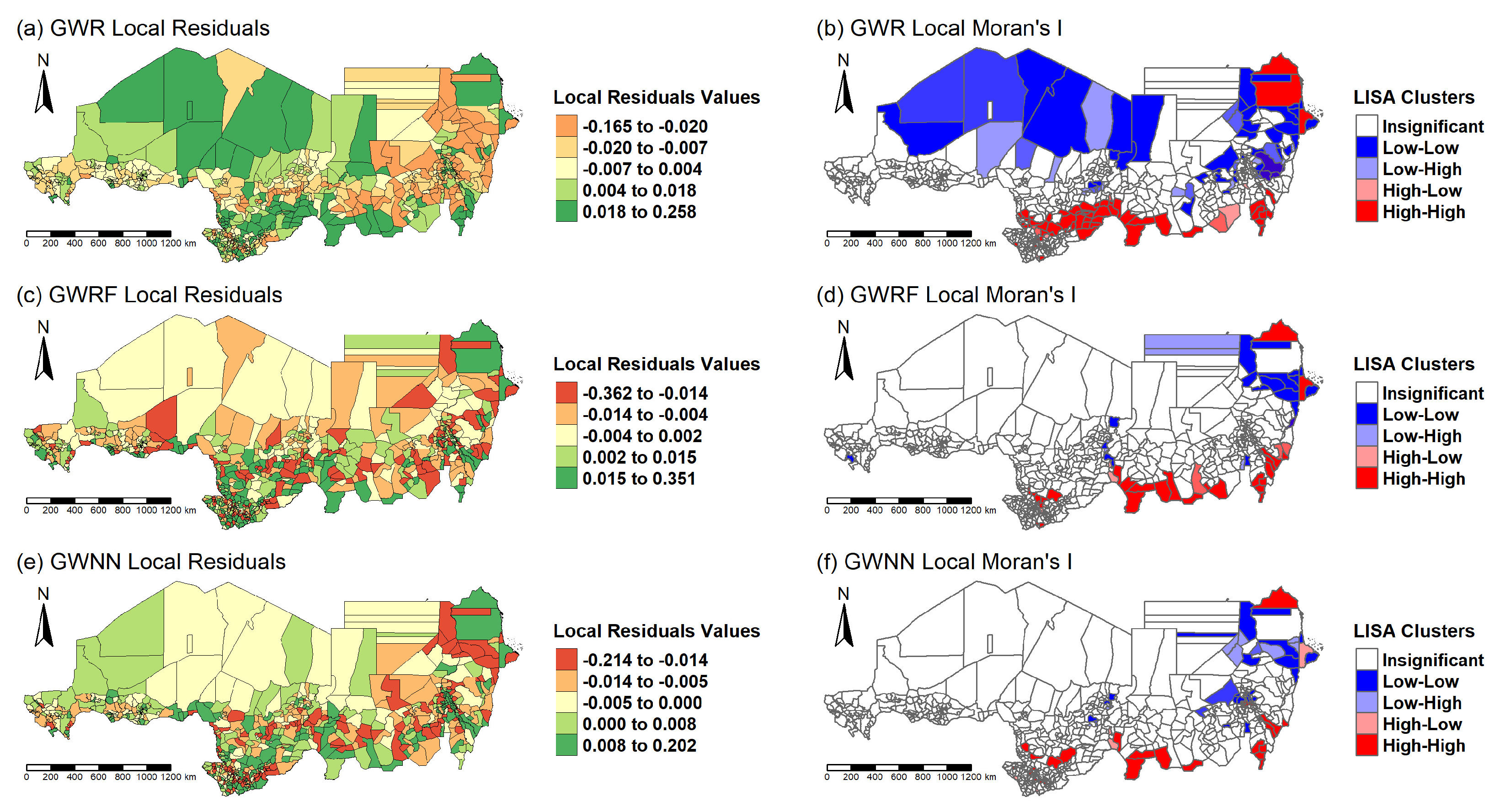

Figure 13.

Residual Mapping and Spatial Clustering (Local Moran’s I) for each Model.

Figure 13.

Residual Mapping and Spatial Clustering (Local Moran’s I) for each Model.

Figure 14.

The Scatterplots of Actual and Predicted NPP in 94 test samples for the OLS, RF, NN, GWR, GWRF, and GWNN Models, Respectively.

Figure 14.

The Scatterplots of Actual and Predicted NPP in 94 test samples for the OLS, RF, NN, GWR, GWRF, and GWNN Models, Respectively.

Table 1.

Datasets and Data Sources for Study Parameters.

Table 1.

Datasets and Data Sources for Study Parameters.

| Data |

Variables |

Unit |

Source |

Format |

Spatial Resolution |

| Climate |

Rainfall |

|

CHIRPS |

TIF file (.tif) |

|

| |

Temperature |

|

ECMWF |

NetCDF (.nc) |

|

| Soil |

Soil Moisture |

|

ESACCI |

NetCDF (.nc) |

|

| Topography |

Elevation |

|

SRTM |

TIF file (.tif) |

|

| Vegetation Indices |

NDVI |

- |

AVHRR |

NetCDF-4 (.nc4) |

|

Table 2.

Missingness Percentage per Variable.

Table 2.

Missingness Percentage per Variable.

| Variables |

Missing Value % |

| NDVI/NPP |

2.23 |

| Soil Moisture |

3.30 |

| Elevation |

7.03 |

| Rainfall |

0.00 |

| Temperature |

1.81 |

Table 3.

Summary statistics of NPP and environmental predictors.

Table 3.

Summary statistics of NPP and environmental predictors.

| Variable |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

Median |

SD |

| NPP |

0.006 |

0.602 |

0.272 |

0.228 |

0.135 |

|

Soil Moisture

|

0.061 |

0.248 |

0.169 |

0.181 |

0.031 |

|

Elevation

|

201.13 |

1297.68 |

447.12 |

411.36 |

160.69 |

|

Temperature

|

269.95 |

304.28 |

301.77 |

301.70 |

1.26 |

|

Rainfall

|

0.44 |

117.68 |

50.86 |

44.42 |

30.50 |

Table 4.

OLS Results.

| Variable |

Coefficient |

Std Error |

t-Statistic |

p-value |

| Intercept |

0.272211 |

0.001783 |

152.630 |

< 2e-16 |

| DEM |

0.010649 |

0.002396 |

4.445 |

9.82e-06 |

| Soil |

0.012330 |

0.001880 |

6.559 |

8.96e-11 |

| Rainfall |

0.122999 |

0.002011 |

61.174 |

< 2e-16 |

| Temp |

0.017131 |

0.002407 |

7.117 |

2.19e-12 |

| Adjusted

|

0.8354 |

|

|

|

Table 5.

Coefficient Estimates from GWR and OLS Regressions.

Table 5.

Coefficient Estimates from GWR and OLS Regressions.

| |

Min. |

1st Qu. |

Median |

Mean |

3rd Qu. |

Max. |

F3 Test

(p-value) |

Global

OLS |

| Intercept |

0.0304 |

0.2182 |

0.2703 |

0.2582 |

0.2965 |

0.4116 |

1.50e-152 |

0.272211 |

| DEM |

-0.5019 |

-0.0209 |

-0.0001 |

-0.0115 |

0.0194 |

0.1259 |

4.37e-139 |

0.010649 |

| Soil Moisture |

-0.0136 |

0.0002 |

0.0027 |

0.0030 |

0.0063 |

0.0183 |

2.90e-10 |

0.012330 |

| Rainfall |

0.0155 |

0.0940 |

0.1279 |

0.1280 |

0.1583 |

0.2352 |

4.34e-146 |

0.122999 |

| Temperature |

-0.0350 |

-0.0055 |

0.0103 |

0.0260 |

0.0522 |

0.1815 |

2.62e-183 |

0.017131 |

Table 6.

Summary Results of RF and GWRF Models.

Table 6.

Summary Results of RF and GWRF Models.

| |

RF |

GWRF |

| |

|

|

Local Feature Importance (IncMSE) |

| Rank |

Variable |

Global Feature Importance |

Variable |

Min |

Max |

Mean |

Std |

| 1 |

Rainfall |

14.5951 |

Rainfall |

|

0.3379 |

0.0175 |

0.0331 |

| 2 |

Soil Moisture |

0.8620 |

DEM |

|

0.3216 |

0.0075 |

0.0212 |

| 3 |

Temperature |

0.8408 |

Temperature |

|

0.0751 |

0.0056 |

0.0084 |

| 4 |

DEM |

0.5900 |

Soil Moisture |

|

0.2066 |

0.0054 |

0.0173 |

|

0.8985 |

0.9376 |

| MSE |

0.0018 |

0.001 |

Table 7.

Missingness Percentage per Variable.

Table 7.

Missingness Percentage per Variable.

| The Local Value of

|

% of counties |

| ≤ 0.2 |

22.04 |

| (0.2, 0.4] |

16.30 |

| (0.4, 0.6] |

27.69 |

| (0.6, 0.8] |

27.26 |

| > 0.8 |

6.71 |

Table 8.

Global Moran’s I for Residuals of GWR, GWRF, and GWNN.

Table 8.

Global Moran’s I for Residuals of GWR, GWRF, and GWNN.

| Model |

Global Moran’s I |

p-value |

| GWR |

0.1750 |

2.2e-05 |

| GWRF |

-0.0352 |

0.9958 |

| GWNN |

-0.0004 |

0.4810 |

Table 9.

Comparison of Models’ Performance on the Test Dataset using Cross-validation.

Table 9.

Comparison of Models’ Performance on the Test Dataset using Cross-validation.

| |

OLS |

RF |

NN |

GWR |

GWRF |

GWNN |

| MSE |

0.0030 |

0.0018 |

0.0023 |

0.0015 |

0.0013 |

0.0012 |

| RMSE |

0.0542 |

0.0429 |

0.0474 |

0.0371 |

0.0337 |

0.0333 |

| MAE |

0.0392 |

0.0270 |

0.0324 |

0.0243 |

0.0191 |

0.0205 |

|

0.8378 |

0.9008 |

0.8755 |

0.9207 |

0.9308 |

0.9360 |