Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

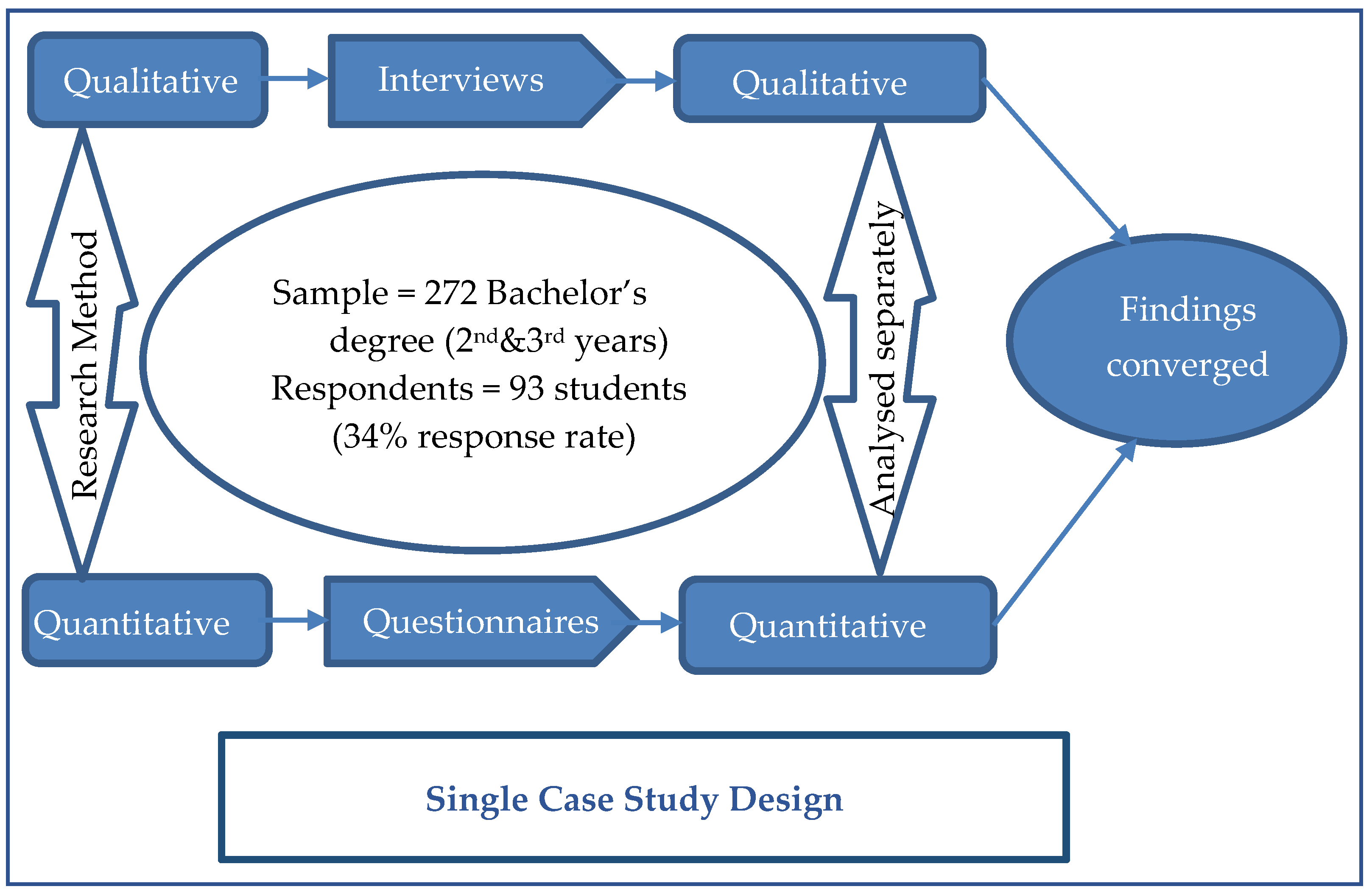

2. Methodology

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants and Sampling

2.3. Data Analysis and Presentation

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. AI Use Declaration

3. Results and Discussion

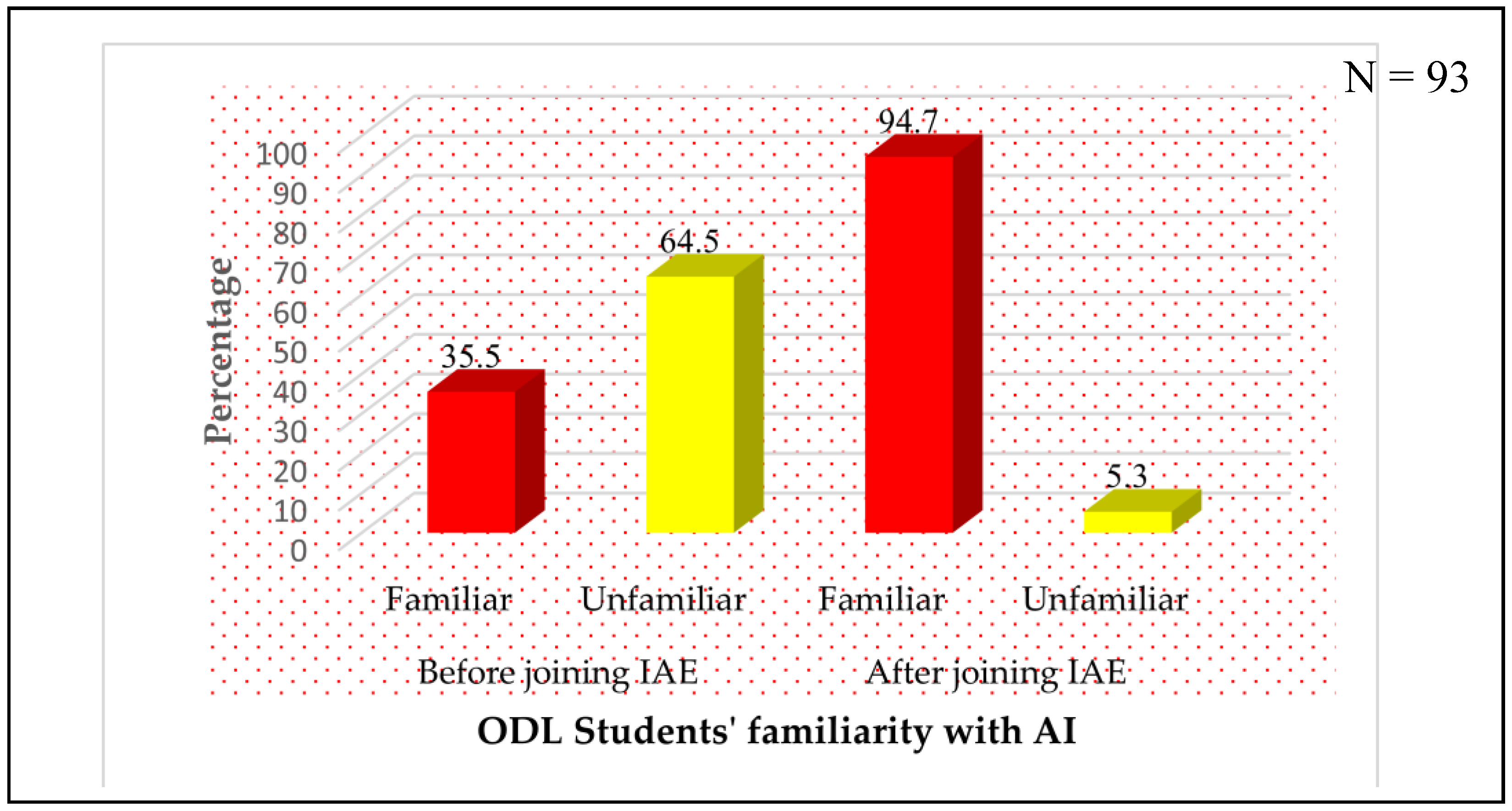

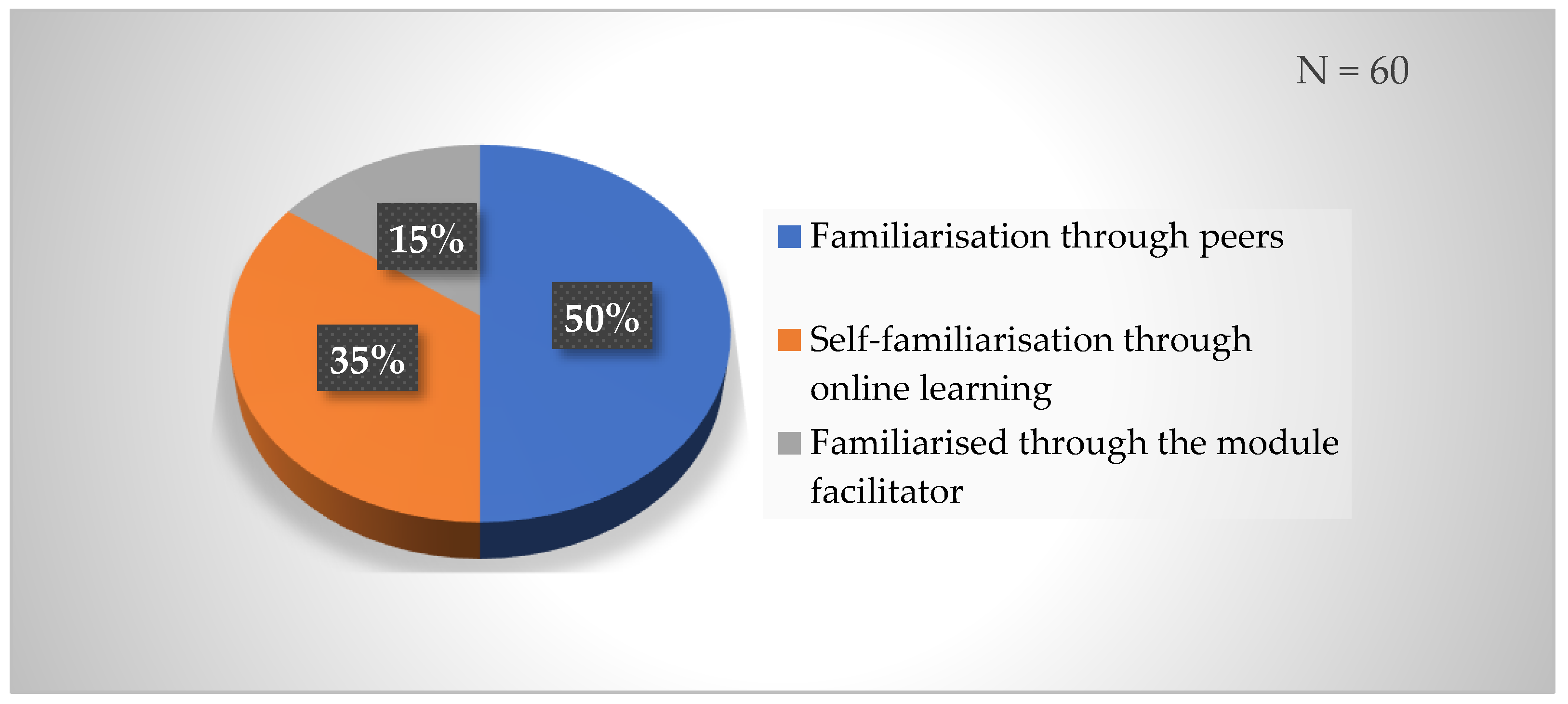

3.1. Participants’ Familiarity with AI Tools

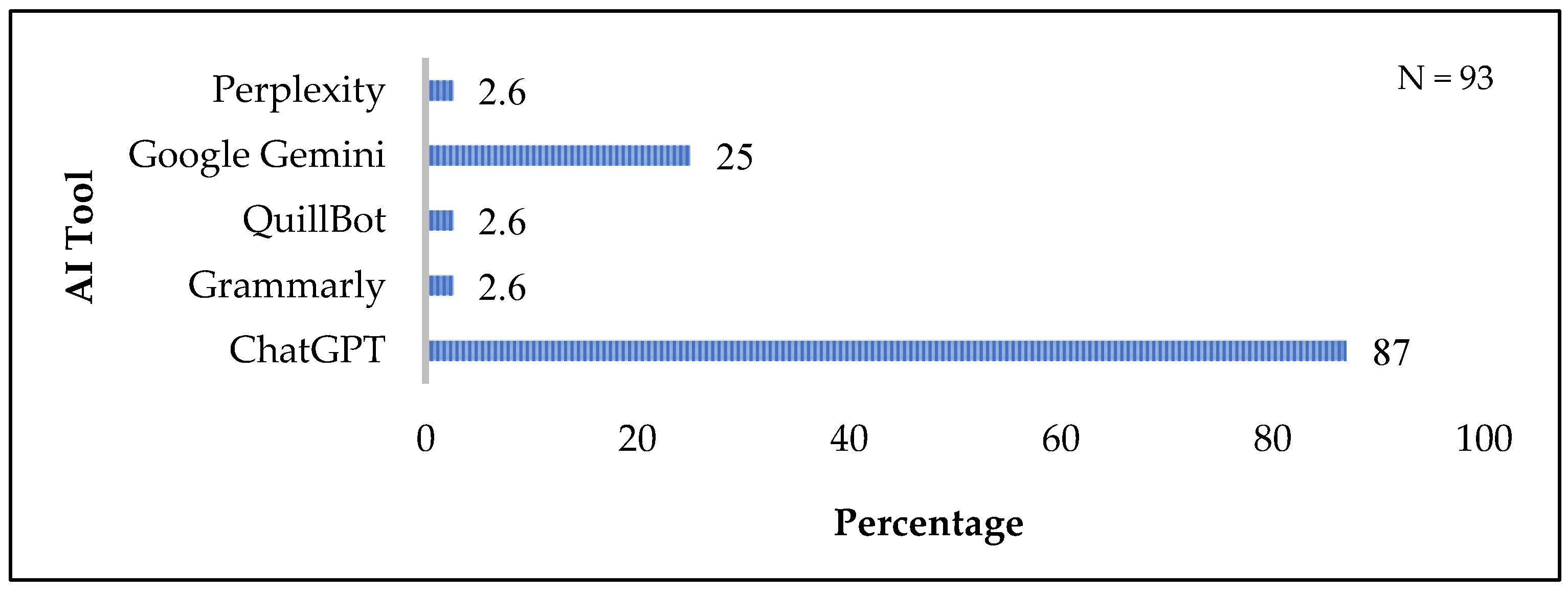

3.2. Preferred AI Tools Among the [anonymized] ODL Students

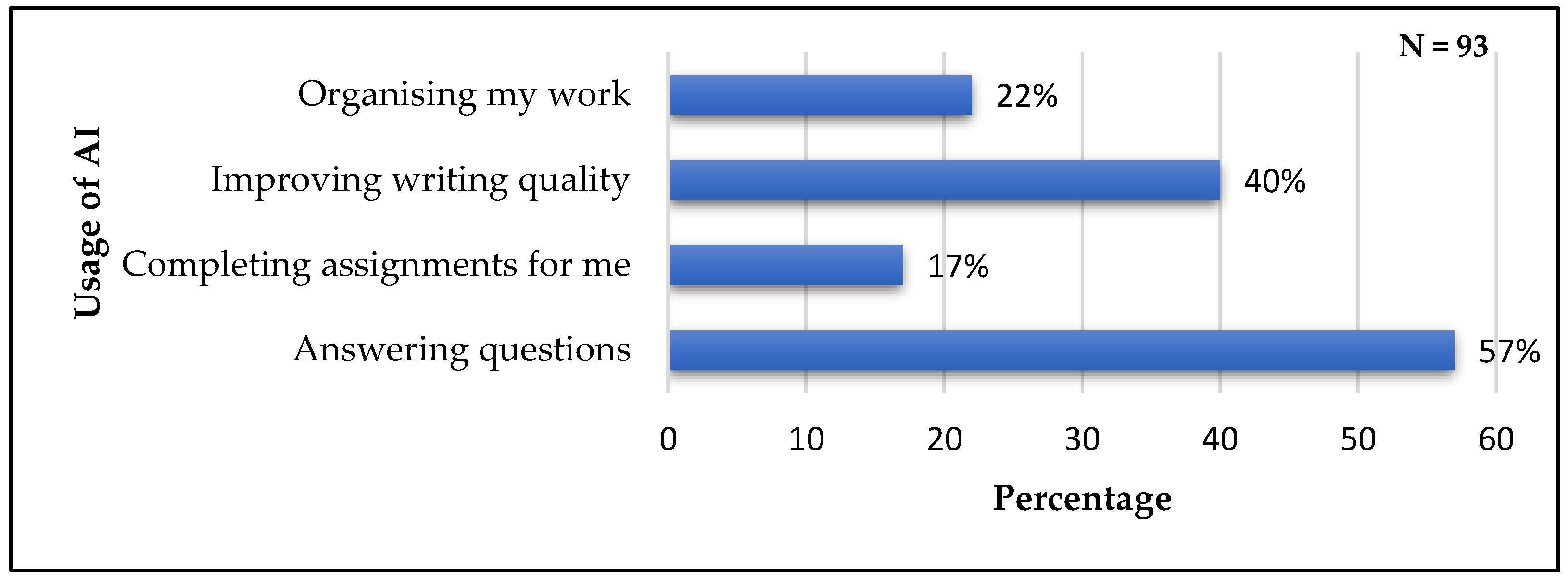

3.3. Utilisation of the AI-Preferred Tools Among ODL Students

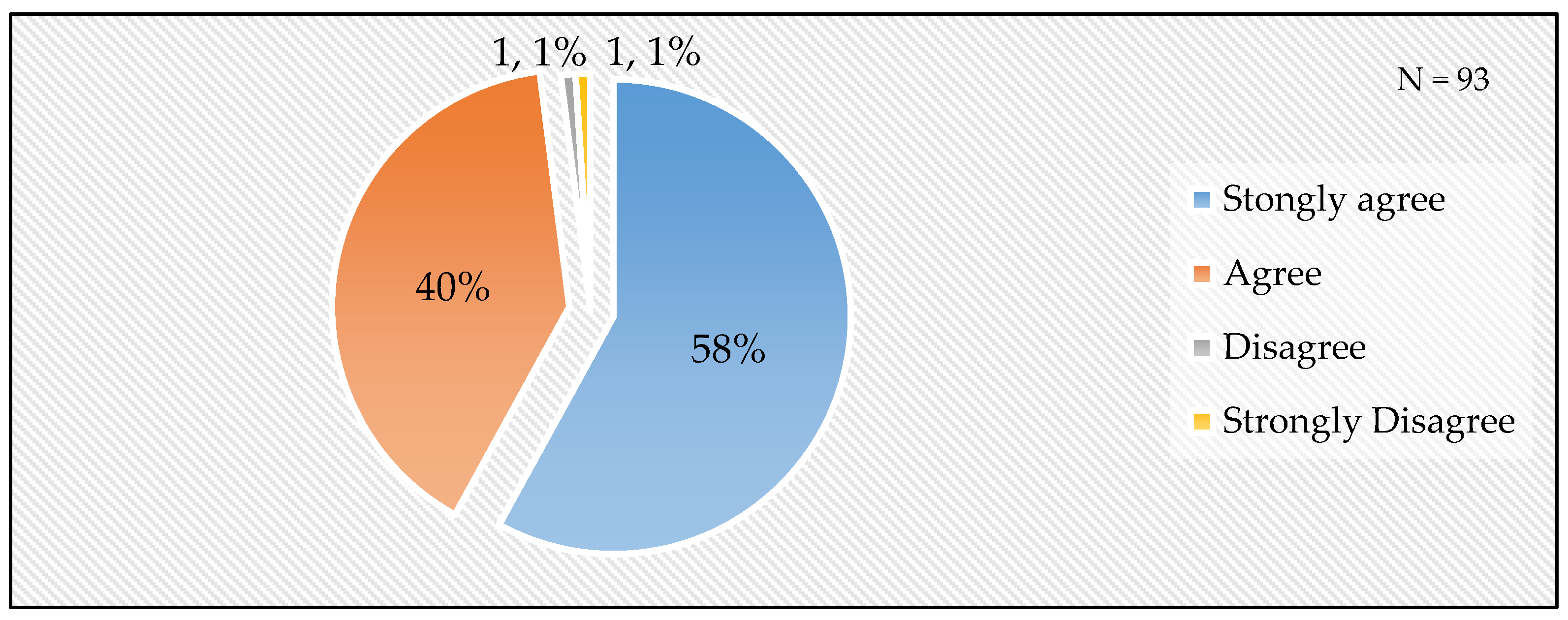

3.4. ODL Students’ Perspectives on the Use of AI Tools in Their Learning

4. Conclusions and Recommendations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| BACE | Bachelor in Adult and Continuing Education |

| BAECD | Bachelor in Adult Education and Community Development |

| ChatGPT | Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer |

| IAE | Institute of Adult Education |

| ICT | Information and Communications Technology |

| ODL | Open and Distance Learning |

References

- S. E. Öncü, M. S. E. Öncü, M. Gevher, and E. Erdoğdu, “Exploring the potential use of generative AI for learner support in ODL at scale,” J. Educ. Technol. Online Learn., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 80–99, 2025. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Maijo, “Learners’ Perception and Preference of Open and Distance Learning Mode at the Institute of Adult Education, Tanzania,” East African J. Educ. Soc. Sci., vol. 2, no. Issue 3, pp. 79–86, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Magembe, “Challenges Facing ODL Students when Conducting Research in Tanzania : A Case of Institute of Adult Education Regional Centres,” J. Adult Educ. Tanzania, vol. 25, no. 2, pp. 45–68, 2023. [CrossRef]

- O. Emmanuel, “Challenges of Assessment of Teaching and Learning in Open and Distance Learning (ODL): The Case Study of Diploma Programme Offered by the Institute of Adult Education in Tanzania,” J. Adult Educ. Tanzania, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 41–63, 2018.

- M. R. M. Amin, I. M. R. M. Amin, I. Ismail, and V. M. Sivakumaran, “Revolutionizing Education with Artificial Intelligence (AI)? Challenges, and Implications for Open and Distance Learning (ODL),” Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open, vol. 11, no. January, p. 101308, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. O. Oparaduru and F. N. Uchendu, “Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Open and Distance Learning and e-Learning: A Comprehensive Overview,” Niger. Open, Distance e-Learning J., vol. 2, no. May, pp. 54–62, 2024.

- H. Lin and Q. Chen, “Artificial intelligence (AI) -integrated educational applications and college students’ creativity and academic emotions: students and teachers’ perceptions and attitudes,” BMC Psychol., vol. 12, no. 1, p. 487, 2024. [CrossRef]

- URT, “National Guidelines for Artificial Intelligence in Education,” Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, Ministry of Education Science and Technology, 2025.

- URT, “National Digital Education Strategy, 2024/25 - 2029/30,” Ministry of Education, Science and Technology, 2025.

- UNESCO, “Beijing Consensus on Artificial Intelligence and Education,” 2019.

- AU, “Continental Artificial Intelligence Strategy: Harnessing AI for Africa’s Development and Prosperity,” 2024.

- S. A. Itasanmi, O. A. S. A. Itasanmi, O. A. Ajani, H. A. Andong, and C. N. Tawo, “Assessment of Artificial Intelligence (AI) Proficiency and its Demographic Dynamics among Open Distance Learning (ODL) Students in Nigeria,” Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res., vol. 24, no. 6, pp. 251–272, 2025. [CrossRef]

- F. Yaseenzai, G. F. Yaseenzai, G. Mustafa, M. Zafar, I. Chaudhary, and S. Yasir, “Use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Open and Distance Learning (ODL) institutions: Opportunities, Challenges, and the Way Forward,” Jahan-e-Tahqeeq, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 507–517, 2024.

- Z. Li, C. Z. Li, C. Wang, and C. J. Bonk, “Exploring the Utility of ChatGPT for Self-Directed Online Language Learning,” Online Learn. J., vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 157–180, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Sengul, S. T. Sengul, S. Sarikose, B. Uncu, and N. Kaya, “The effect of artificial intelligence literacy on self-directed learning skills: The mediating role of attitude towards artificial intelligence: A study on nursing and midwifery students,” Nurse Educ. Pract., vol. 88, p. 104516, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Marquardson, “Embracing Artificial Intelligence to Improve Self-Directed Learning: A Cybersecurity Classroom Study,” Inf. Syst. Educ. J., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 4–13, 2024. [CrossRef]

- C. Bosch and D. Kruger, “AI chatbots as Open Educational Resources: Enhancing student agency and Self-Directed Learning I chatbot AI come Risorse Educative Aperte: potenziare l’efficacia della partecipazione nel processo educativo e l’apprendimento autoregolato dello studente,” Ital. J. Educ. Technol., vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 53–68, 2024.

- M. Al Mashagbeh, M. M. Al Mashagbeh, M. Alsharqawi, U. Tudevdagva, and H. J. Khasawneh, “Student engagement with artificial intelligence tools in academia : A survey of Jordanian universities,” Front. Educ., vol. 10, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. P. Suharto, Zubaidi, Nurdjizah, A. N. Putri, and P. Sekarsari, “The use of AI-based Writing Tools ( Quillbot and Chatgpt ) in Developing the Writing Competence of Language Learners,” Esteem J. English Study Program., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 259–269, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. Omar, Z. R. Omar, Z. Osman, and O. L. Hsien, “Artificial Intelligence Adoption in Authentic Online Assessments : A Study of Online Distance Learning Institutions,” Int. J. Acad. Res. Progress. Educ. Dev., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 864–879, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. Freeman, “Student Generative AI Survey 2025,” HEPI Policy Note 61, no. February. Higher Education Policy Institute, pp. 1–12, 2025.

- H. Mbembati and H. Bakiri, “Generative Artificial Intelligence-Based Learning Resources for Computing Students in Tanzania Higher Learning Institutions,” Univ. Dar es Salaam Libr. J., vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 146–162, 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. M. Stuart, “Effects of Artificial Intelligence on the Academic Competency of Students of Higher Learning Institutions : A Case Study of Kampala International University in Tanzania,” Tanzanian J. Multidiscip. Stud., vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 63–84, 2024.

- G. S. Mollel, “Determinants of AI Utilization among Tanzania Higher Learning Students : Examining Trends, Predictors, and Academic Applications,” East African J. Inf. Technol., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 57–69, 2025. [CrossRef]

- M. Baynit, C. B. F. M. Baynit, C. B. F. Mnyanyi, and M. S. Msoroka, “Digital Learning in the Age of Artificial Intelligence: Insights from Selected Higher Learning Institutions in Tanzania,” African Q. Soc. Sci. Rev., vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 96–112, 2025. [CrossRef]

- J. W. Creswell and V. L. P. Clark, Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. SAGE Publications, 2017.

- B. E. Mariki, “Multimedia Features towards Skills Development in Open Learning : A Case of the Girls Inspire Project in Tanzania,” East African J. Educ. Soc. Sci., vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 89–98, 2024. [CrossRef]

- D. D. Nulty, “The adequacy of response rates to online and paper surveys: What can be done?,” Assess. Eval. High. Educ., vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 301–314, 2008. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Sax, S. K. L. J. Sax, S. K. Gilmartin, and A. N. Bryant, “Assessing Response Rates and Nonresponse Bias in Web,” Res. High. Educ., vol. 44, no. 4, pp. 409–432, 2003. [CrossRef]

- V. J. Owan, K. B. V. J. Owan, K. B. Abang, D. O. Idika, E. O. Etta, and B. A. Bassey, “Exploring the Potential of Artificial Intelligence Tools in Educational Measurement and Assessment,” EURASIA J. Math. Sci. Technol. Educ., vol. 19, no. 8, p. Article 13428, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Wang, “Exploring Students’ Generative AI-Assisted Writing Processes: Perceptions and Experiences from Native and Nonnative English Speakers,” Technol. Knowl. Learn., vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 1825–1846, 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. N. T. Nguyen, N. T. N. T. Nguyen, N. Van Lai, and Q. T. Nguyen, “Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Education: A Case Study on ChatGPT’s Influence on Student Learning Behaviors,” Educ. Process Int. J., vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 105–121, 2024. [CrossRef]

| Participants | Excerpts |

|---|---|

| Student 10 | As distance learners, AI helps us to access learning and understand various issues related to our studies. |

| Student 5 | In cases where clarification is needed on complex words or topics, it is easier for us who study remotely to ask AI than it is to ask fellow students. |

| Student 15 | AI assists us in gaining broader knowledge. |

| Student 9 | AI make our lives easier as it clarifies various issues. |

| Student 13 | We get instant answers to our class assignments. |

| Student 6 | The technology saves time when searching for answers to what we need. |

| Student 4 | The AI tools simplify our learning, help us answer questions with authentic examples and provide us with knowledge beyond the learning materials provided by module facilitators. |

| Student 7 | AI acts like a facilitator … we ask it questions and get answers, sometimes better than those of module facilitators. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).