1. Introduction

The properties of space are essential for theories, see e. g. Newton [

1], Maxwell [

2], Einstein [

3], Minkowski [

4], Einstein [

5], Hilbert [

6], Hubble [

7], Lamb and Retherford [

8], Casimir [

9], Zeldovich [

10], Perlmutter et al. [

11], Smoot [

12] and Riess et al. [

13]. Thereby, outer space is a relatively ideal form of space in the universe, as outer space is hardly disturbed by molecules or other objects. Hereby, the universe consists of space and of the objects in space.

Moreover, the properties of space are important for applications such as space navigation, see for instance Soffel [

14], telecommunication, quantum cryptography or quantum computer networks.

In order to understand space, it is essential to understand that space has a nonzero energy density

or

. It has essentially been proposed by Einstein [

15] in terms of a cosmological constant

. And its value has been measured by Perlmutter et al. [

11], Riess and others [

16], Smoot [

12].

Furthermore, space was not given in advance. Instead, space expanded from the Big Bang until today, and space will expand in the future, see Friedmann [

17], Wirtz [

18], Lemaître [

19], Hubble [

7], Hobson et al. [

20], Workman and others [

21], Planck Collaboration [

22]. Thereby, the measurable present-day rate

of increase of the space exhibits a problem, the

- tension: Measurements provide different values of

at the 5

confidence level, see Riess and others [

13].

This problem is explained here at the level of first principles and a founded and critically reflected scientific method, see sections (

Section 1.1,

Section 1.1.1).

Firstly, an idealization of space is identified with help of a paradox. The idealization is that in present-day science space as a single entity. With help of a founded derivation, this idealization is overcome: Homogeneous space is a stochastic average of indivisible volume portions.

Secondly, a volume dynamics is derived for these volume portions.

Thirdly, the quantum postulates, gravity, and the Local Formation of Volume (LFV) are derived from this volume dynamics.

Fourthly, based on these founded and derived dynamical processes, the energy density of volume is derived for the case of a homogeneous universe. For that case, this energy density is called . It is in precise accordance with the observed value of the early universe, which was very homogeneous. Moreover, for this homogeneous case, the corresponding value is identified, in precise accordance with observation.

Of course, the universe is heterogeneous. Accordingly, the heterogeneity is analyzed in addition to the homogeneous universe. As a result, the value of the late universe, which is very heterogeneous, is derived. This result is in precise accordance with observation.

These results provide a very convincing evidence for the concept that homogeneous space is a stochastic average of indivisible volume portions. Moreover, these results represent a very clear evidence that the

- tension is explained by the gradual evolution of heterogeneity in the universe. These two fundamental insights improve the present-day model of cosmology, the

CDM model. Additionally, these findings can be applied to space navigation and exploration, see Carmesin [

23,

24].

1.1. Hypothetic Deductive Method

In this paper, the results are obtained by the hypothetic deductive method, see Popper [

25,

26], Niiniluoto, Sintonen and Wolenski [

27]. Hereby, the following hypotheses are used:

1.1.1. Used Hypotheses

In this section, the hypotheses are presented that are used in the hypothetic deductive method. Thereby, these hypotheses are very founded. Therefore, the risk of failure is very small.

(1) The space, that can be observed in the whole volume

V ranging from Earth to the light horizon, is isotropic and homogeneous at this universal scale. Local heterogeneities are possible, for instance near a mass

M, see Schwarzschild [

28], Dyson, Eddington and Davidson [

29,

30]. This has been observed, see Planck Collaboration [

22].

(1.1) Moreover, there is natural space that is very homogeneous and isotropic at small scales. For instance, natural space is very homogeneous and isotropic in a void, see Zeldovich, Einasto and Shandarin [

31], Contarini et al. [

32], and natural space was very homogeneous and isotropic in the early universe, see Planck Collaboration [

22].

(1.2) Furthermore, in the heterogeneous universe, natural space can exhibit slight heterogeneity, additionally. For instance, in the heterogeneous universe, Abbott et al. [

33] observed the merger of a binary stellar-mass black hole system, and the gravitational waves emitted thereby. These gravitational waves can be interpreted as coherent states that cannot be emitted in a natural homogeneous universe without heterogeneity, as only an appropriate heterogeneity can emit coherent states.

(2) Space has a positive energy density

, it is the dark energy density. It is the density of the energy

E of the volume

V of the space in part (1), divided by this volume:

This has been discovered by Perlmutter et al. [

11], Riess and others [

16], Smoot [

12].

(3) The energy speed relation of special relativity theory (SRT) holds, see Einstein [

3], Hobson et al. [

20]: In general, an object with an energy

E has a velocity

relative to a mass

, that is used as a reference. Its absolute value is called speed

. In the case of zero speed,

, the energy is called rest energy

. The energy speed relation of SRT is as follows:

In the case

, the relation has the following equivalent form:

Hereby and in the following, the velocity is determined relative to an adequate coordinate system of relativity theory, for details see section (

Section 1.1.5).

(4) Each volume or volume portion

of space has zero rest energy

, and it has zero rest mass

.

(5) In a process of increase of volume or space, the dark energy density

is a nonzero constant, whereby only very small variations might occur. This approximate constancy has been observed for the expansion of space since the Big Bang, see Planck Collaboration [

22], Riess et al. [

13]. Additionally, that constancy has been proposed by general relativity theory and cosmology, see Einstein [

15], Friedmann [

17], Lemaître [

19], Hobson et al. [

20]. Furthermore, the value of

is derived here, and the results are additional evidence for this approximate constancy.

The above very founded hypotheses (1) to (5) will be used for deductions in this paper.

1.1.2. Why Volume Has no Rest Mass

In this section, it is shown that volume has zero rest mass .

In the vicinity of a mass

M, there occurs additional volume

, see section (

Section 1.1.4) or

Figure 1. If that additional volume would have a rest energy

, then there would be an additional rest mass

in the vicinity of each mass

M. Such an additional rest mass has never been observed, see e. g. Landau and Lifschitz [

34], Workman et al. [

21], Planck Collaboration [

22], Zogg [

35]. For instance, if there would be such an additional rest mass

, then this

would modify the orbits of the GPS satellites, and this would have been observed, but this has not been observed. Consequently, additional volume

has no rest mass.

Moreover, the additional volume in the vicinity of a mass is the same type of volume as the usual volume that occurs without any mass. this is confirmed by the observation that only one type of volume has been observed, see e. g. Workman et al. [

21], Planck Collaboration [

22], Casimir [

9], Zeldovich [

10], Perlmutter et al. [

11]. Therefore, in general, volume has no rest mass.

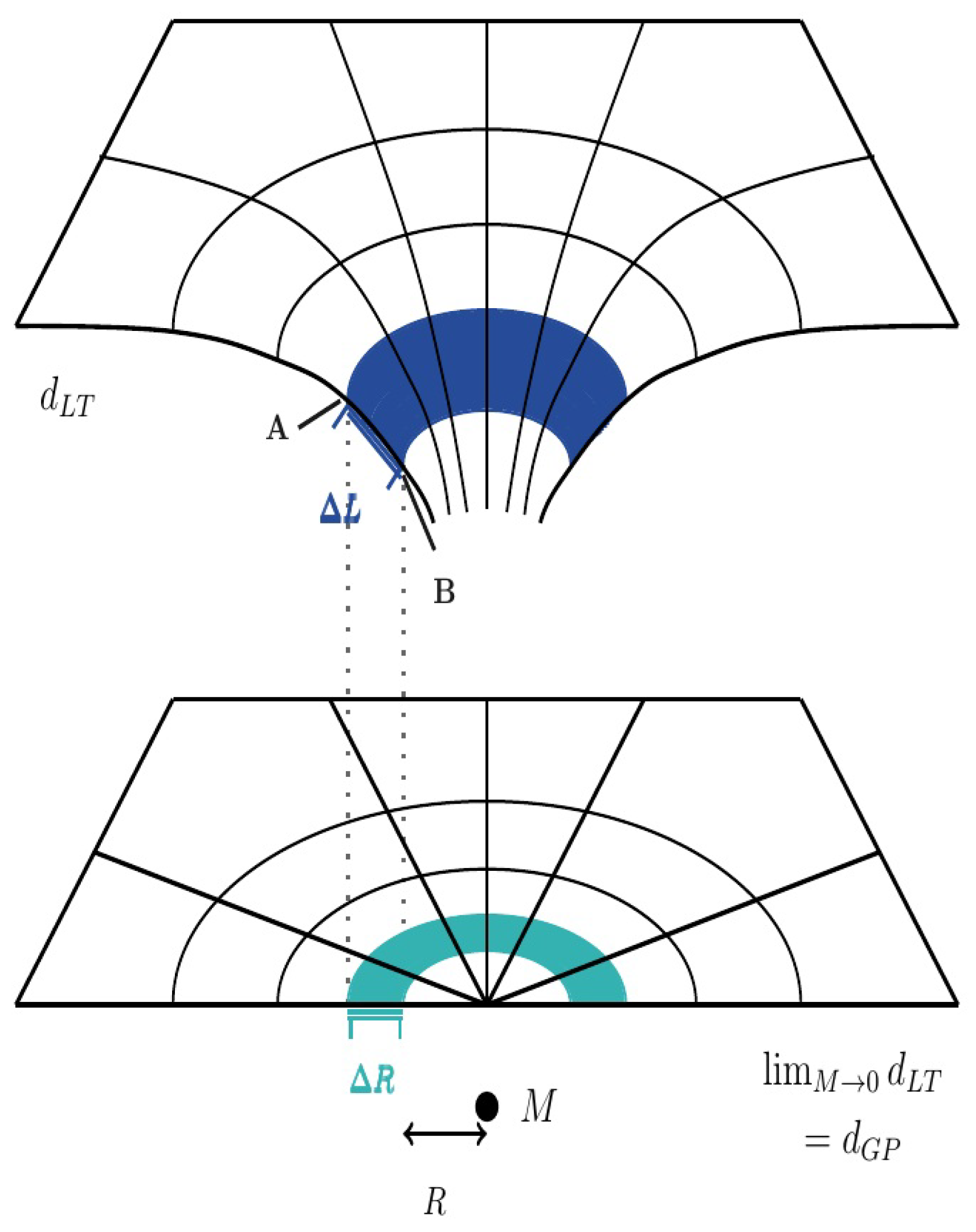

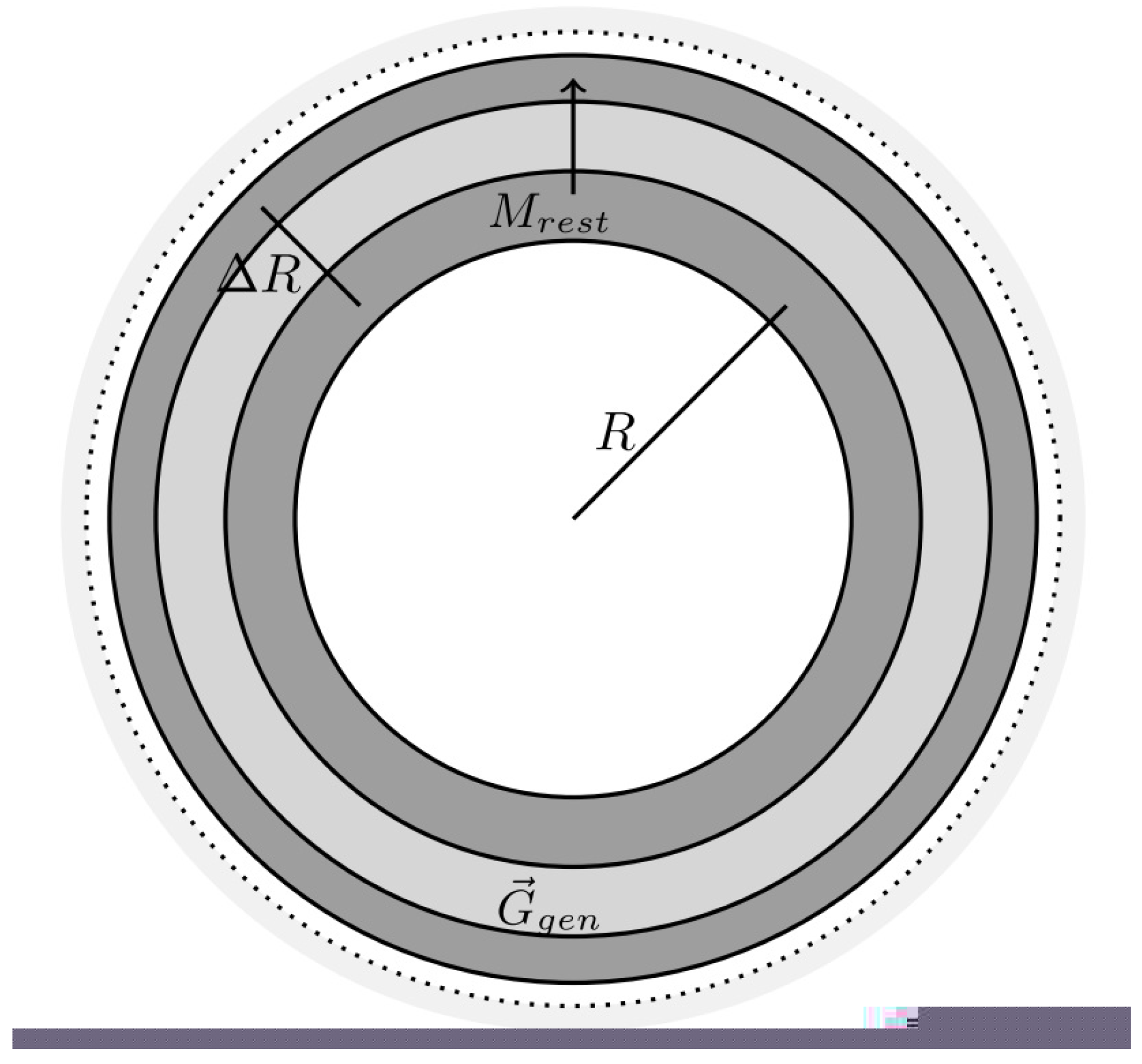

1.1.3. Mass Causes an Increase of Radial Light Travel Distance

In this section, it is shown that a mass

M causes an increase of the radial distance

R to

M. This increase occurs at each radial difference

, see

Figure 1.

For instance, in the vicinity of a mass

M, an original (at

) radial distance

is increased by the square root

of the radial element

of the metric tensor to a value

, see

Figure 1,

Hereby, the value

can be measured as a

light travel distance, see Hobson et al. [

20]. Similarly, the original value

can be measured with help of two hand leads, the distance is called

gravitational parallax distance, see Carmesin [

23,

36].

As a consequence of general relativity, see Einstein [

5], Hilbert [

6], Hobson et al. [

20], at each radial coordinate (or gravitational parallax distance)

R, the radial element

of the metric tensor can be expressed with help of the Schwarzschild [

28] radius

:

These relations are in precise accordance with observation, see e. g. Dyson, Eddington and Davidson [

29], Pound and Rebka [

30], Will [

37].

According to the Hacking [

38] criterion of reality, this increase of radial light travel distance

is real, as it can be manipulated as follows: The mass

M can be increased, and this causes an increase of radial light travel distance

, see Eqs. (

5 and

6).

Moreover, also the gravitational parallax distance

is real, as it can be manipulated as well: For instance, in

Figure 1,

is the distance between the points

A and

B. If

B moves towards

A, then

decreases. Next, the corresponding volume is analyzed:

1.1.4. Mass Causes an Increase of Volume

In this section, the following is shown: In the vicinity of a mass M, the increase of the radial length causes an increase of the volume.

Without loss of generality, an portion of volume is used with and .

In the vicinity of a mass

M, the radial distance

is increased to the respective light travel distance

by the factor

, while

and

are not changed by

M. Consequently, the volume

is increased to the respective volume

by the factor

, see Eq. (

5):

The difference of the volume

measured with the gravitational parallax distance and the volume

measured with the light travel distance is called

additional volume:

The ratio

is called

relative additional volume :

1.1.5. On the Adequate Coordinate Systems

In the theory of relativity, a time interval

of a clock onboard a satellite

E and a time interval

of a clock onboard a satellite

F exhibit the phenomenon of kinematic time dilation. Thereby, relativity theory states: Between two events

A and

B, a clock in a laboratory coordinate system exhibits a time

, a clock onboard the satellite

E exhibits a time

, and a clock onboard the satellite

F exhibits a time

as follows:

Hereby,

is the speed of the satellite

E relative to the laboratory coordinate system, and

is the speed of the satellite

F relative to the laboratory coordinate system. However, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) realized that relativity theory does not provide information about the choice of an adequate laboratory coordinate system or laboratory frame. Such information about the frame is essential for predicting the times shown by the above clocks, and it is important for space navigation. The IAU called this lack of information the problem of finding an

adequate coordinate system (ACS), see Soffel [

14].

The problem of finding an adequate coordinate system (ACS) has been solved [

23,

24,

39].

Thereby, for each point P in the universe, the following has been shown:

(1) An ACS exists.

(2) The ACS has a uniquely determined velocity , relative to an arbitrarily chosen coordinate system .

(3) can be measured, and procedures of measurement are provided.

(4) can be predicted and calculated, and procedures for it are provided.

(5) The equations of time dilation in Eq. (

10), as well as the energy speed relation in Eqs. (

2 and

3) hold, when the ACS is used. Moreover, the typical results of relativity hold, when the ACS is used.

(6) There exists an absolute zero of the fractional kinematic time difference

whereby the chosen laboratory coordinate system is equal to the ACS.

In this paper, the ACS is used. Therefore, the derived results have clearly defined conditions.

1.2. Observed Energy Density of Volume

In outer space, Perlmutter et al. [

11] and Riess et al. [

16] discovered the accelerated rate of expansion of the universe. Based on the Friedmann Lemaître equation (FLE), this implies a nonzero energy density of empty space, see e. g. Friedmann [

17], Lemaître [

19], Hobson et al. [

20], Carmesin [

40]. It is called density

of the cosmological constant

or density

of the dark energy density [

10,

15,

20,

41]. An actual value observed with help of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) is as follows: [

22,

23,

40]

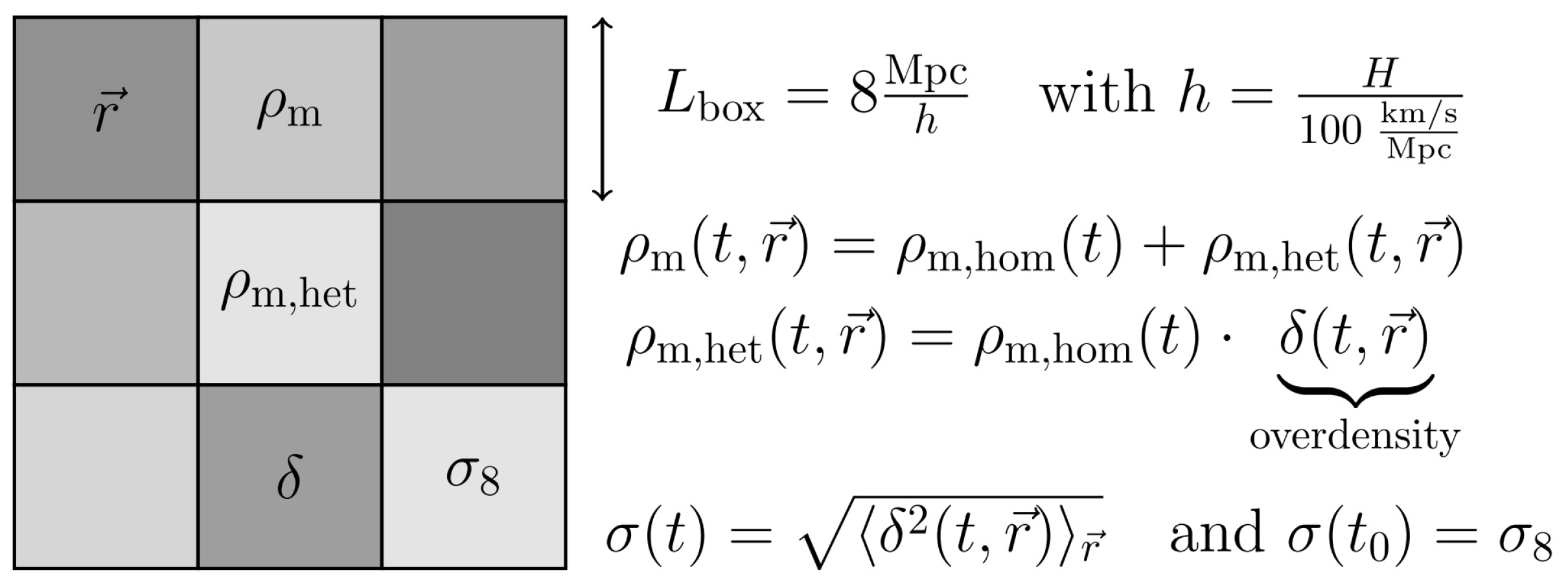

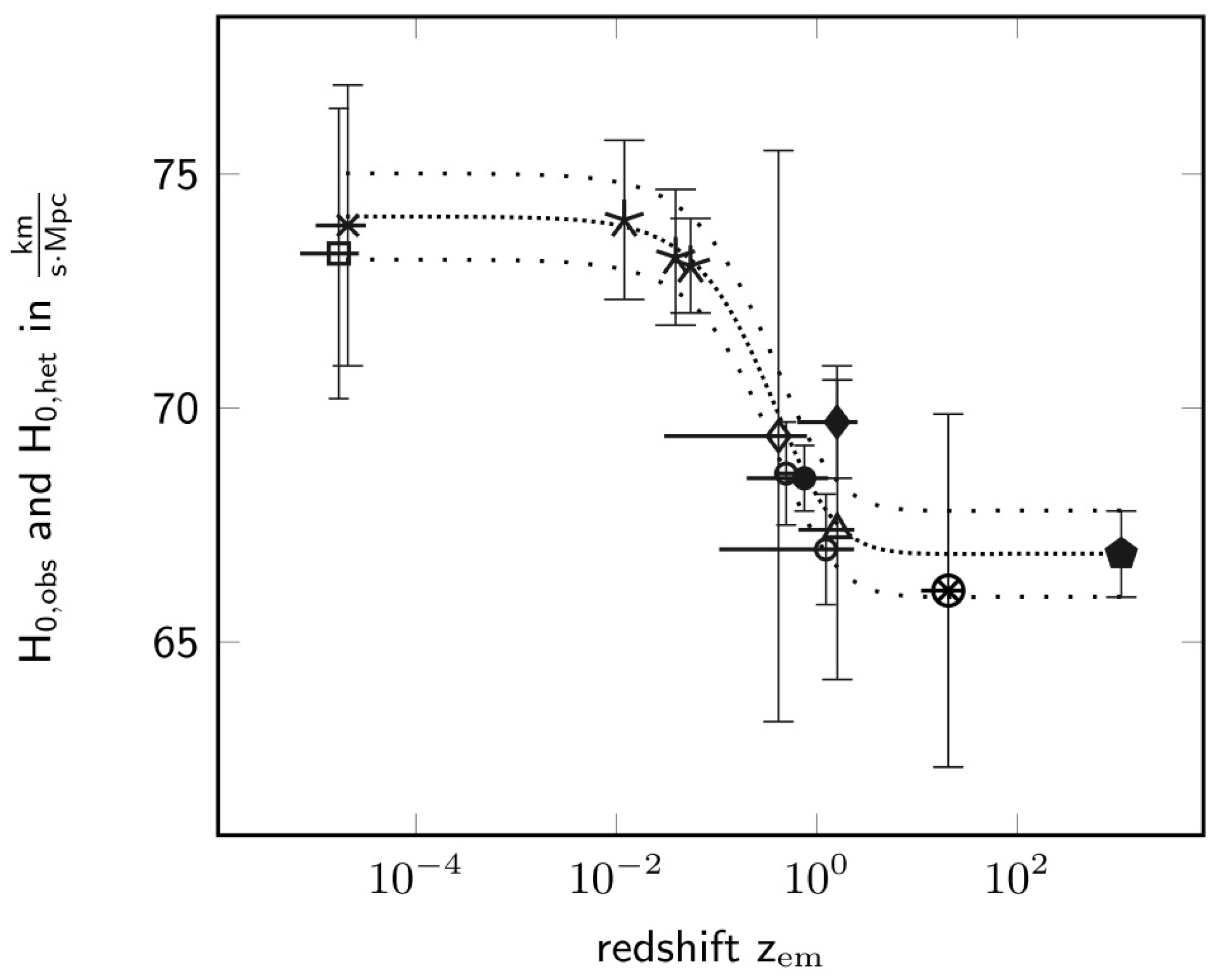

2. Problem of the Hubble Tension

In this section, we summarize a very interesting problem of modern physics. In particular, this problem is a discrepancy of two observed values that should be equal according to the

CDM model of present-day physics, see e. g. Hobson et al. [

20]. Consequently, this discrepancy falsifies the

CDM model. In general, according to the hypothetic deductive method, a solution of such a falsification-problem provides the chance to improve concepts of physics [

25,

26]. In this paper, we will use the problem in order to develop founded and essential improvements of present-day physics.

Hubble [

7] discovered the present-day rate of expansion of space since the Big Bang, the

Hubble constant . In general, the Hubble constant is measured by utilizing signals that have been emitted at a time

or at a corresponding redshift

, see e. g. Hobson et al. [

20].

Penzias and Wilson [

42] discovered the

cosmic

microwave

background (CMB), a radiation that has been emitted in the early universe, at

after the Big Bang. Utilizing that radiation, the Planck Collaboration [

22] observed the corresponding value of the Hubble constant:

Hereby, the redshift of emission is

. In the measurement, the so-called temperature - temperature correlation, TT, has been used[

22] table 2, column 1.

As another example, Riess et al. [

13] utilized radiation emitted from supernovae of type Ia in near galaxies and obtained the following observed

- value:

Thereby, many galaxies with different redshift values

have been observed. Accordingly, the redshift

of emission is described by the average of the redshift values of the observed[

13] sections 5.1 and 5.2 galaxies,

.

Riess et al. [

13] observed a discrepancy between the

- value based on the CMB and the

- value based on near galaxies. Such a discrepancy is called

Hubble tension or

tension, see e. g. Planck Collaboration [

22]. That discrepancy is at the five

confidence level. Consequently, that discrepancy can be regarded and named as a scientific result [

13]. This result falsifies the

CDM model, as this model states that the value of

should not depend on the redshift value of observed objects. Based on such a falsification of a model, that model can be interpreted as an

idealization, see e. g. Shech [

45], Song et al. [

46]. Consequently, the

idealization of the ΛCDM model is identified:

The Hubble tension falsifies the CDM model. Accordingly, the CDM model is an idealization.

Therefore, the Hubble tension or tension is a founded scientific problem. A fundamental solution of this problem is derived in this paper. Hereby, no fit is executed, no unfounded hypothesis is proposed, and a precise accordance with observation is achieved, and predictions are derived.

Moreover, the value of the Hubble constant

of the early universe is a

- value of a nearly homogeneous universe, since the early universe was nearly homogeneous [

22]. In contrast,

is a

- value of the late universe, as the observed supernovae occured in the late universe. Additionally,

is a value of the heterogenous universe, as the late universe is very heterogeneous [

22,

47,

48].

As the Hubble constant describes the rate of expansion of space since the Big Bang, we analyze the properties of space in more detail. For it, in section (

Section 3), we show that the present-day view of space includes a paradox, the so-called space paradox. Moreover, we derive a solution of that space paradox. With it, we will explain and derive the Hubble tension. This solves the problem of the Hubble tension.

3. Space paradox

In general, a paradox provides the chance to develop a deep insight [

49]. In this section, we will derive a paradox, and we will use it in order to develop a deep insight.

In the following, the space, that can be observed in the whole volume

V ranging from Earth to the light horizon, is considered. For instance, this space has been observed [

22].

In physical concepts that are commonly used at the present-day, the space with its volume

V is considered as a

single entity, see e. g. Newton [

1], Maxwell [

2], Einstein [

5,

17], Lemaître [

19], Landau and Lifschitz [

50], Hobson et al. [

20], Planck Collaboration [

22].

That space has a positive energy density

, see Eq. (

1):

As a consequence of SRT, the volume

V with its energy

E of space, velocity

, and speed

, obey the energy speed relation, see Eqs. (

2 and

3)

As the energy density is nonzero, the energy

E is nonzero. Thus, the above relation can be divided by

. Therefore, the following form of the energy momentum relation holds:

As a consequence of the zero rest energy

of

V, see Eq. (

4), the right hand side in Eq. (

17) is zero. Consequently, the volume

V with its energy

E has the speed

c of light in vacuum.

3.1. The paradox

In physical concepts that are commonly used at the present-day, the volume is considered as a single entity, see e. g. Newton [

1], Maxwell [

2], Einstein [

5], Friedmann [

17], Lemaître [

19], Landau and Lifschitz [

50], Hobson et al. [

20], Planck Collaboration [

22]. In such a concept of volume, that whole volume would move parallel to some unit direction vector

and with the speed of light,

, see Eq. (

18).

However, that velocity

would break the isotropy of space observed at a universal scale [

22]. This is a contradiction. In general, a paradox is a contradiction, the solution of which provides a deeper insight [

49]. The above contradiction is called the

space paradox. It is solved next:

3.2. A solution of the space paradox in natural homogeneous space

(1) The space paradox has five premises: There are four founded premises about space and its volume

V, see section (

Section 1.1), parts (1) - (4), part (5) is not used here: isotropy, the positive dark energy density, the energy speed relation of SRT (which is correct in the used ACS, see

Section 1.1.5), and the zero rest energy

. And there is one hardly founded premise (see the beginning of

Section 3.1): the concept of space as a single entity. Therefore, space is not a single entity.

As space is not a single object, it must consist of many parts of the volume V. These parts are analyzed next. Thereby, a part of the space with its volume V is called a volume portion (VP).

Hereby, parts of volume with at least one local maximum of volume are analyzed. Thereby, for each part, one such maximum is used in order to localize that part . Such a part is called a localized VP.

Since the energy and volume of space have the speed

, the above parts

must have the same speed. For instance, each part

has its speed

In general, a part of volume is called volume portion.

(2) Next, for the case of a homogeneous universe and space, and for the case of a usual density , The following question is analyzed:

Can such a part with consist of smaller parts ?

Hereby, a usual density

is a density below an ultrahigh critical density

at which the symmetry of space breaks in a phase transition. This can occur in a phase transition from space to matter in the Higgs [

51] mechanism. Moreover, this can take place in a dimensional phase transition [

36,

40,

52,

53]).

If such a part with of space would consist of smaller parts , then the following would be implied:

(2.1) Each smaller part would have the speed , as the energy and volume of space have the speed .

(2.2) Consequently, each part would have a velocity , with a direction vector with norm one.

(2.3) As the considered universe is homogeneous (see part (2)), there is no source that could provide a uniform direction of the direction vectors .

(2.4) Hence, the velocity

of the considered part

with

would be an average of the velocities

. Thereby, as a consequence of the different direction vectors

in part (2.3), the velocity

would have an absolute value smaller than

c, i. e.

. This would contradict the speed

in Eq. (

19).

(2.5) Therefore, the parts with speeds cannot consist of smaller parts. This is the answer to the question in (2). This implies that the parts with are indivisible. Such a part with its speed is called indivisible volume portion, indivisible VP.

(3) Next, it is shown how the indivisible VPs solve the space paradox:

(3.1) The energy and volume of space have the speed c, and the energy of space obeys , as space consists of indivisible VPs with the speed .

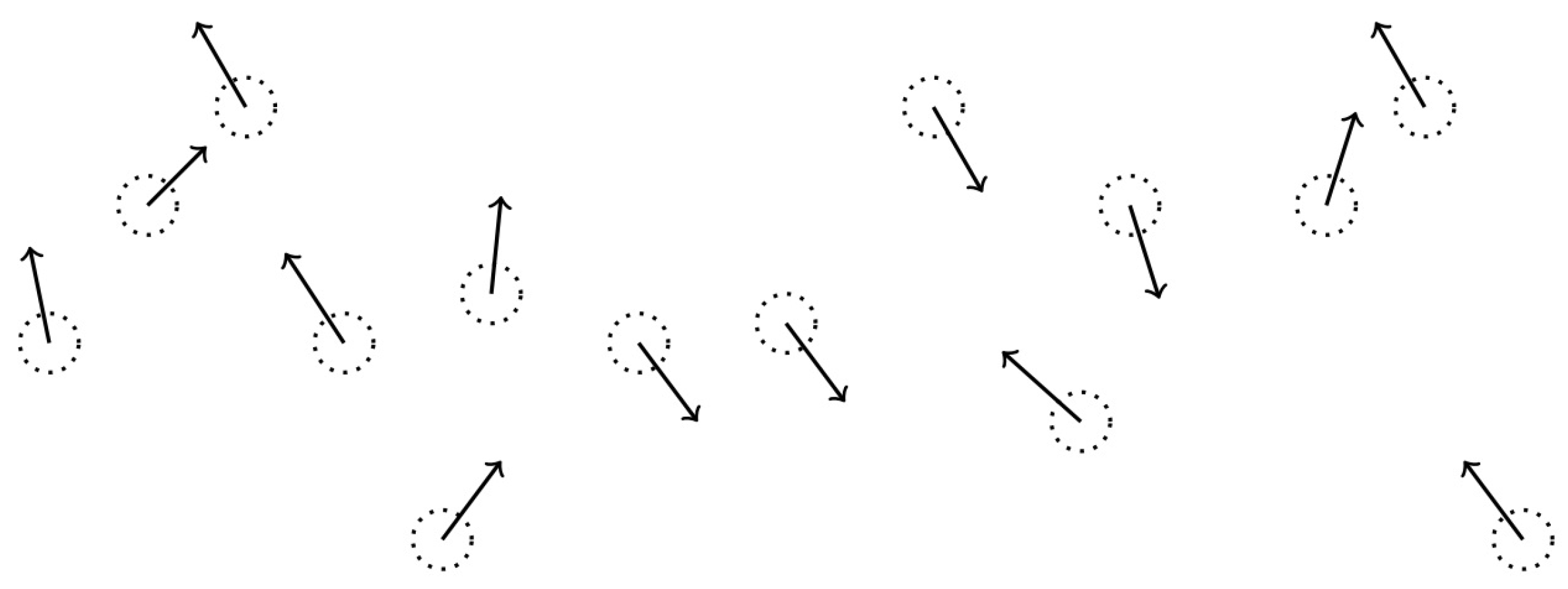

(3.2) Moreover, the velocities of the indivisible VPs have stochastic direction vectors , that are distributed isotropically. Hence, these velocities average to zero.

(3.3) As a consequence, space is isotropic at a universal scale, see

Figure 2. In this manner, the space paradox is solved.

Therefore, we obtain the following deep insight, the stochastic property of space:

In a homogeneous and isotropic universe, space is a stochastic average of many indivisible volume portions , each with the speed . Hereby, the velocities of the volume portions average to zero.

(4) Next, the solution is generalized to heterogeneous space: The early universe was very homogeneous and isotropic [

22]. The heterogeneity of the mass distribution in the universe increased gradually, and thereby the heterogeneity of space evolved gradually [

23,

36,

48,

54,

55]. Therefore, the natural heterogeneous space is a slight variation of the natural homogeneous and isotropic space. Details of that variation will be derived in the solution of the Hubble tension below.

3.3. Examples of Parts of Space

In this section, essential parts of natural space with the volume V are analyzed.

(1) Additional volume in the vicinity of a mass M:

In the vicinity of a mass

M, there occurs additional volume

, see section (

Section 1.1.4). It is at rest relative to

M. Moreover, in the vicinity of

M, the ACS (see

Section 1.1.5) [

23,

24,

39]. is nearly at rest at

M. Consequently, the speed of the additional volume in the vicinity of a mass is clearly smaller than

c, i. e.

. Each additional volume with a speed

must be a stochastic average of the indivisible VPs

with their speeds

, as space with its volume

V consists of indivisible VPs

with their speeds

. This is the case for homogeneous and isotropic space and for the case of heterogeneous space which is a slight variation of homogeneous and isotropic space.

Altogether, additional volume that is at rest in the vicinity of a mass M is a stochastic average of indivisible VPs.

(2) Relative additional volume :

In general, a VP

is located within an underlying VP

. The relative additional volume

is the following ratio of the VP

and of its underlying VP

, see section (

Section 1.1.4):

Thereby, the ratio

is usually interpreted as a tensor element, whereby the

L - direction is the

z - direction or the 3 - direction:

In general, a volume portion VP

represents a change of an underlying VP

, and this change represents a tensor element or tensor. Thereby, typically, the change of each VP

has a quadrupolar structure. A dipolar structure is excluded, as volume cannot be negative. Therefore, each change of an underlying VP

can be described by a tensor of rank two. It is called

change tensor [

23,

36]

. In general, an element

of a change tensor is the ratio of the change

divided by the underlying length

:

Hereby, for each normalized direction vector

, the underlying length

is the sum of the original length

and the change

:

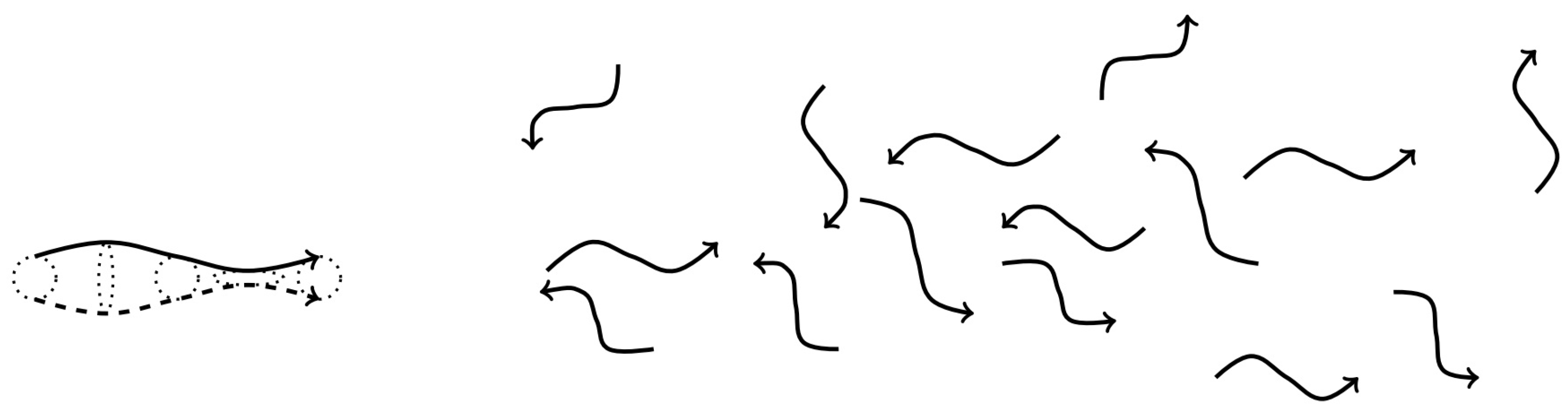

In general, indivisible VPs can have the structure of a change tensor as well, see

Figure 3.

(3) Gravitational wave:

Without loss of generality, a gravitational wave can be described as follows [

50]: It has an angular frequency

. At a location, a gravitational wave has one direction of propagation

, and two transverse directions

and

. There are two possible modes. In a first mode, the elongations are

and

, with

, see

Figure 3. The second mode is equal to the first mode rotated by 45

o around

.

The elongations and the velocity of the gravitational wave can be measured with help of a Michelson interferometer. For instance, Abbott et al. [

33] measured the amplitude

.

In the theory of waves, the above observed gravitational wave is a wave with a coherence length that amounts several wave lengths. Accordingly, a gravitational wave could be interpreted as a coherent state in the framework of quantum physics, if quantum physics is applicable.

3.4. On Quantum Properties of an Indivisible VP

The indivisible VP in homogenous space is very founded. According to this indivisibility, a minimal extension of an indivisible VP is estimated with help of the Heisenberg [

56] uncertainty relation of quantum physics:

In general, an indivisible VP can have very different forms, and matter or radiation can be placed in the VP. As an example, and as a very simple model, an indivisible VP is analyzed, that has the form of a ball with a radius , and that contains no radiation or matter.

Consequently, the volume is

Thus, the VP has the following energy:

As the VP has the speed

. the energy momentum relation of special relativity theory (SRT) provides the following momentum:

In the rest system of the VP, the momentum is zero, so that the standard deviation alias uncertainty of momentum is estimated by

. Similarly, the spatial standard deviation alias uncertainty of the indivisible VP is estimated by

The Heisenberg [

56] uncertainty relation for these standard deviations is as follows:

The estimated standard deviations in Eqs. (

26 and

27) are inserted into the above uncertainty relation:

This uncertainty relation is solved for the spatial uncertainty

:

Altogether, the very particular considered indivisible VP, that does not contain any matter or radiation, has a minimal spatial uncertainty of

3.5. Empirical Evidence for Indivisible Volume Portions

The derivation of indivisible VPs is based on isotropy at small scales. Accordingly, empirical evidence for indivisible VPs is of interest. Such evidence is presented in this section.

3.5.1. Estimated Time Uncertainty of Indivisible Volume Portions

In four-dimensional spacetime, the length

of an indivisible VP is estimated by Eq. (

30). It is the standard deviation according to the Heisenberg [

56] uncertainty relation. In four-dimensional spacetime, the corresponding time uncertainty

of an indivisible volume portion is estimated by the ratio of the length and the velocity of light

c:

For instance, for the case of an averaging time of one second,

, the fractional uncertainty is estimated as follows

3.5.2. Time Uncertainty of an Atomic Clock Using Gas

Many atomic clocks use gas atoms [

57,

58]. As these atoms move in natural space, and as an atom is very small compared to the estimated size of an indivisible VP, the clock’s uncertainty is larger or equal to the uncertainty of an indivisible VP in homogeneous natural space, in general. Similarly, if an object moves within a ship, then the object’s uncertainty is larger or equal to the ship’s uncertainty, in general.

For the case of natural space consisting of indivisible VPs, the uncertainty of space is estimated by

in Eq. (

32). Therefore, for the case of averaging of one second,

In general, the uncertainty of a clock can be reduced by averaging during a time

. Thereby, according to statistics, and according to observation, the uncertainty decreases by the factor

[

57,

59]. Empirical data show the following [

57]: Atomic clocks that use gas atoms, that are not confined to any particular location or trajectory, and that are averaged at most one second,

, exhibit time uncertainties larger than the estimated uncertainty of indivisible VPs in Eq. (

32). This provides evidence for the existence of indivisible VPs. Moreover, a control experiment is available:

3.5.3. Time Uncertainty of an Atomic Lattice Clock

In an atomic lattice clock, the used atoms are confined to the potential minima of a standing wave of laser light. Hereby, the standing wave, and the device that generates that wave, are large compared to the estimated size of an indivisible VP. As a consequence, these atoms do not move freely in an indivisible VP of homogeneous natural space, but in artificially generated potential minima. Therefore, the atomic lattice clock’s uncertainty can be smaller than the estimated uncertainty of indivisble VPs in Eq. (

32). In fact, measurements show that this is clearly the case. There is even a local maximum of the uncertainty as a function of the time

of averaging [

60]:

This control experiment provides evidence for the following: The independence of the uncertainty of natural space and of indivisible VPs can provide a very small uncertainty of an atomic lattice clock.

4. On the Dynamics of Volume Portions

In this section, a very valuable and insightful description of VPs is developed. With it, a very general differential equation (DEQ) of the dynamics of VPs is derived.

Here and in the following, mathematically, a VP could be arbitrarily small. Physically, the Heisenberg [

56] uncertainty relation limits the standard deviation of a VP from below. A particular example is analyzed in section (

Section 3.4).

4.1. Additional Volume

In this section, the increase

of the volume

of a VP is analyzed. For it, the difference of the increased volume

and the original volume

of the VP is used:

Hereby and in the following, a light travel distance

is larger or equal to the corresponding gravitational parallax distance

, i. e.

, so the particular case without curvature is included. The above difference

is called

additional volume, see section (

Section 1.1.4).

Similarly as in section (

Section 1.1.3), according to the Hacking [

38] criterion, the enlarged volume

and the additional volume

are real, as they can be manipulated. In contrast, the original volume

is an idealization corresponding to the idealization of flat space:

Each VP has a real additional volume and a real enlarged volume

, according to the Hacking [

38] criterion.

In order to derive general laws of physics, this difference is normalized in the next section:

4.2. Relative Additional Volume

In general, in order to derive general laws of physics, it is valuable to use intensive quantities rather than extensive quantities [

61]. In the present case of a VP, it is useful to utilize the ratio of its real additional volume

and its real enlarged volume

. Such ratios are formed and analyzed in detail in this section:

That ratio is called

relative additional volume , see Eq. (

9):

The relation to the metric tensor is achieved by inserting Eqs. (

7 and

36) into Eq. (

37):

This is an example for the fact that curvature can be described by the metric tensor or by the relative additional volume. Moreover, the relative additional volume of a VP is real, as it is a ratio of real quantities of that VP:

Each VP has a real relative additional volume.

Furthermore, the description with the additional volume is compatible with the volume portions that become necessary for the solution of the space paradox. In contrast, the metric tensor does not include the concept of volume portions, and it does not provide the dynamics of the volume portions. As a consequence, the description with the volume portions provides the additional possibility to derive the dynamics of volume portions. Of course, the metric tensor provides the description of time dilation directly. In the case of volume portions, the Schwarzschild [

28] metric is used. Thereby, the tensor element of the time

is utilized. With it, an interval of coordinate time

is transformed to an interval of own time

[

20]. With help of the volume portions, the dynamics of volume portions is derived next:

4.3. Dynamics of Volume Portions

In this section, the dynamics of an arbitrary VP is described by its relative additional volume. The result is achieved with help of calculus or standard analysis only. As a consequence, the dynamics of VPs derived here is very general.

Firstly, the applicability of calculus or standard analysis is investigated:

Calculus or analysis are a mathematical tool, such as algebra and stochastics. Thereby, calculus or analysis do not include a prejudice about the continuity of space and time. The reason is that in the present investigation, space is a stochastic average of VPs. Hereby, VPs will be characterized by eigenvalues with a spectrum of eigenvalues. This spectrum can turn out to be discrete, continuous or partially discrete and partially continuous. As calculus or analysis are used in this study, these fields of mathematics do not necessarily include a prejudice about the discreteness or continuity of space.

In contrast, an exclusion of calculus and analysis would include a prejudice about the discreteness or continuity of space.

In fact, the space paradox and the implied structure of space as a stochastic average of VPs does already deduce an essential degree of discreteness of space. And it is important to investigate the amount of discreteness and continuity of these VPs in the following.

Moreover, in this paper, the physical reality of the used and deduced concepts is permanently tested with help of the Hacking [

38] criterion.

Secondly, the differential equation, DEQ, of VPs is derived:

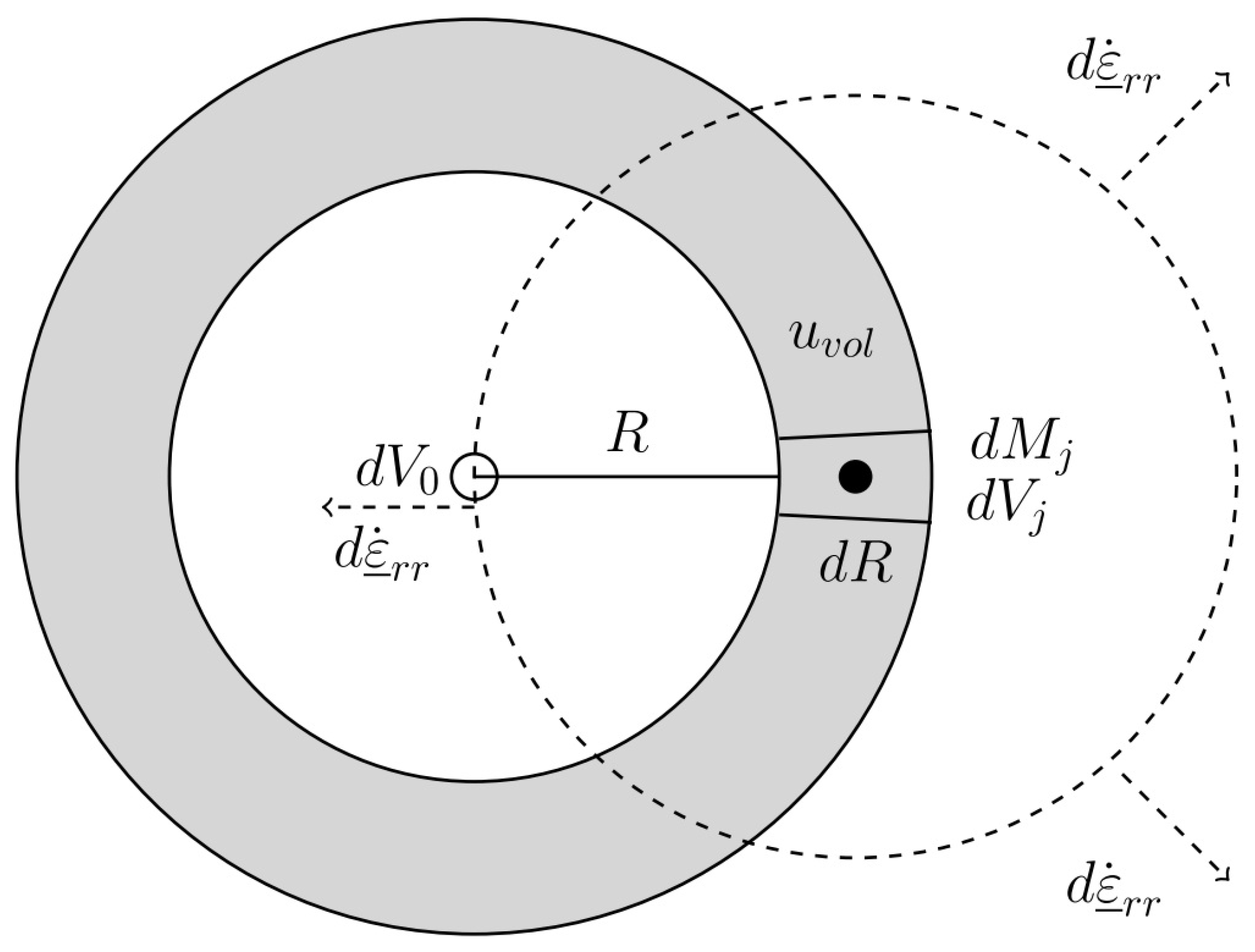

Each localized VP (see

Section 3.2, part (1)) has a local maximum of its relative additional volume

. It is a function of its three-dimensional position vector

and of the time

. It is illustrated in

Figure 4, whereby the three-dimensional position vector is summarized by a position

L. Altogether, a localized VP can be described by a function

with a local maximum. If there should be several local maxima or a set of local maxima, then one local maximum can be chosen as a convention.

As a fact of calculus or of analysis, at the local maximum, the change of

is zero. Thus, the total derivative is zero:

That derivative is evaluated with help of partial derivatives:

The VP moves parallel to a corresponding direction unit vector

of its velocity

. Therefore, during a time

, the vector

changes by the amount

=

. With it, the total derivative in Eq. (

40) is

The above Eq. is divided by

. Moreover, the Eq. is solved for

:

This is the differential equation, DEQ, of VPs or of

volume dynamics (VD). A Lorentz invariant form of the DEQ is achieved as follows. The square is applied to Eq. (

42), and the right hand side is subtracted,

Each localized VP fulfills the volume dynamics in Eq. (

42) or in the Lorentz invariant Eq. (

43).

For the following reasons, the derived dynamics is very founded and insightful: The derived DEQ of VD describes the dynamics of a VP with at least one local maximum. The derivation uses no postulate or unfounded hypothesis. In contrast, general relativity uses postulates such as the Einstein Hilbert action or the Einstein field equation [

5,

6]. Similarly, quantum physics uses ’guessed’ postulates [

62,

63,

64]. Also gravity uses ’guessed’ postulates or restrictions. Examples are the restriction to physics without quanta in general relativity [

5], and in Newton’s gravity [

1]. Another example is the graviton hypothesis. Thereby, gravity uses hypothetic quanta [

65].

Indeed, we will show later that the DEQ of VD implies gravity and curvature of space and time. Moreover, we will show that the DEQ of VD implies the postulates of quantum physics. In particular, based on the VD, we derive the Schrödinger equation in the next section.

5. Derivation of the Schrödinger Equation

In this section, we show that each VP fulfills a generalized Schrödinger equation (GSEQ), which implies the usual Schrödinger equation (SEQ), which holds for the special case of a non-relativistic mass M.

5.1. The Volume Dynamics Implies the GSEQ

In this section it is shown, that VPs with their VD imply the GSEQ.

(1) In a first investigation, the geometry of relative additional volume is analyzed:

For each VP, the DEQ (

42) of VD is fulfilled. Thereby, the VP moves in the direction

of its velocity, see

Figure 4.

In general, a relative additional volume with an increase

with the normalized direction vector

and with a propagation of indivisible VPs in the same direction, and with an underlying length

, is called

unidirectional relative additional volume

, see Eqs. (

21,

22 and

23). More information about such tensors can be found in the literature [

23,

36,

50,

66,

67].

(2) Next, each VP is described by the DEQ of VD. In that DEQ,

is inserted. Additionally, the time derivative is applied, so that the relative additional volume

becomes

, which is usually expressed by

. As a consequence, the DEQ of VD implies the following DEQ:

(3) Next, as an equivalence transformation of the above DEQ, the factor

is multiplied. This multiplication is also physically equivalent, as the system of units can be chosen freely. And the factor

ℏ is one in natural units [

68]. Consequently, the DEQ of VD implies the following DEQ:

Moreover, for the case of an indivisible VP, this indivisibility corresponds to the quantum property with its universal unit of quantization, the Planck [

69] constant

h or its reduced version

.

Accordingly, the correspondence principle is applicable [

68]. Consequently, the rectangular bracket is identified with the momentum operator[

67] chapter 9:

In this DEQ,

represents a rate. That rate is normalized by a factor

. In physics,

has the dimension time and the unit second. Consequently, the normalized rate

is dimensionless and has the unit one. It will be shown that the normalized rate has the role of a wave function in the above DEQ. Accordingly, the normalized rate is called wave function

. Of course, this can be regarded as an abbreviation, if desired. As a consequence, the DEQ of VD implies the following DEQ:

The product of the momentum operator and the direction vector of propagation,

, is the operator of the absolute value of the momentum

:

In the present case of a VP that propagates with the speed

c, special relativity implies that the product of

c and the momentum

p is the energy

E. Consequently, according to the correspondence principle [

68], pages 673-674, the product of

c and the momentum operator is the energy operator:

This Eq. has the form of a Schrödinger equation, SEQ. However, the SEQ holds for non-relativistic objects. In contrast, this DEQ holds for relativistic objects too, and it implies the SEQ for non-relativistic objects, see next section (

Section 5.2). Thus, this DEQ is the GSEQ. Moreover,

is real, as it is the derivative of the real

. As a consequence, the wave function

is real, as it is the normalized form of the real

.

Each VP fulfills the GSEQ (50) and has a physically real wave function in Eq. (

48). Thereby, according to the Hacking [

38] criterion, a wave function has an extraordinary physical reality, as it can be manipulated even in a nonlocal manner [

71].

5.2. The Volume Dynamics Implies the SEQ

In this section it is shown, that VPs with their VD imply the SEQ.

For each localizable quantum object at , the following is implied:

(1) For the case of

ultrafast objects, with

[

21] an energy eigenvalue is obtained by the following linear approximation of the energy momentum relation

with respect to the small ratio

:

Hereby,

marks the first order approximation for small

. The corresponding linear approximation of the GSEQ is obtained by replacing the eigenvalue

p by its operator

:

(2) For the case of slow objects, with , the following holds:

(2a) An energy eigenvalue of the energy is obtained by the following linear approximation of the energy momentum relation

with respect to the small ratio

:

(2b) The corresponding linear approximation of the GSEQ is obtained by replacing the eigenvalue

p by its operator

.

Hereby, the wave function includes the rest energy

. Accordingly, the wave function is named

. In general, the following squares are equal:

(2c) The wave function is factorized:

The left hand side of Eq. (

54) is evaluated with the product rule:

(2d) In the above DEQ,

is subtracted. The resulting DEQ is divided by

. As a consequence, the SEQ proposed or postulated by Schrödinger [

72] is derived from the VD:

Additionally,

can include a potential energy:

5.3. Interpretation of VPs and Masses

In this section, the relation between VPs and masses is elaborated on the basis of the above dynamics of the VD, the GSEQ and the SEQ, and of the Higgs [

51] mechanism:

Some elementary particles form their mass by a phase transition [

21,

51,

73,

74,

75]:

In physics [

9,

68,

76], empty space is called

vacuum, and its energy density is the density

of dark energy [

11,

77]. In the above phase transition, the vacuum transforms to a mass.

As shown by the space paradox, the vacuum is a stochastic average of indivisible VPs. As a consequence, the above phase transition transforms indivisible volume portions to a mass.

In a typical phase transition, objects change from one phase to another phase. Thereby, these objects are described by the same fundamental dynamics in the first phase, in the second phase and during the transition. An example is the phase transition of condensation [

78,

79].

In the present case, such a fundamental dynamics that holds in the first phase, in the second phase and during the transition has been derived. It is the DEQ of VD. It holds for VPs in the first phase, and it implies the SEQ that holds for the masses in the second phase. A description of the phase transition in the framework of the VPs is elaborated in Carmesin [

75].

Of course, the question remains how a mass can emit its wave function. This will be derived in the next section: In part (

Section 6), it is shown that the VPs provide gravity as well as the local curvature of space and time as a byproduct. It has already been shown that a mass causes additional volume and VPs, see sections (

Section 1.1.3 and

Section 4.1). In section (

Section 7), the process of

local formation of volume (LFV) and of VPs is described, and a corresponding DEQ of the LFV is derived. These VPs formed by a mass

M represent the wave function of that mass. In part (

Section 10), it is shown for the case of the homogeneous universe, that this DEQ of LFV provides the emergence of the space of the universe and of the energy density

of that space in a homogeneous universe. More generally, in a heterogeneous universe, the energy density of space is

, and the difference of

and

increases gradually with the heterogeneity of the universe, and this difference remained relatively small during the time from the Big Bang until today.

Both results are in precise accordance with observation. Therefore, these results provide a clear evidence for the present theory of VPs.

Each mass M fulfills the SEQ (59) implied by the GSEQ.

M can be formed from VPs via a phase transition [

51,

53,

75].

6. Gravity and Curvature

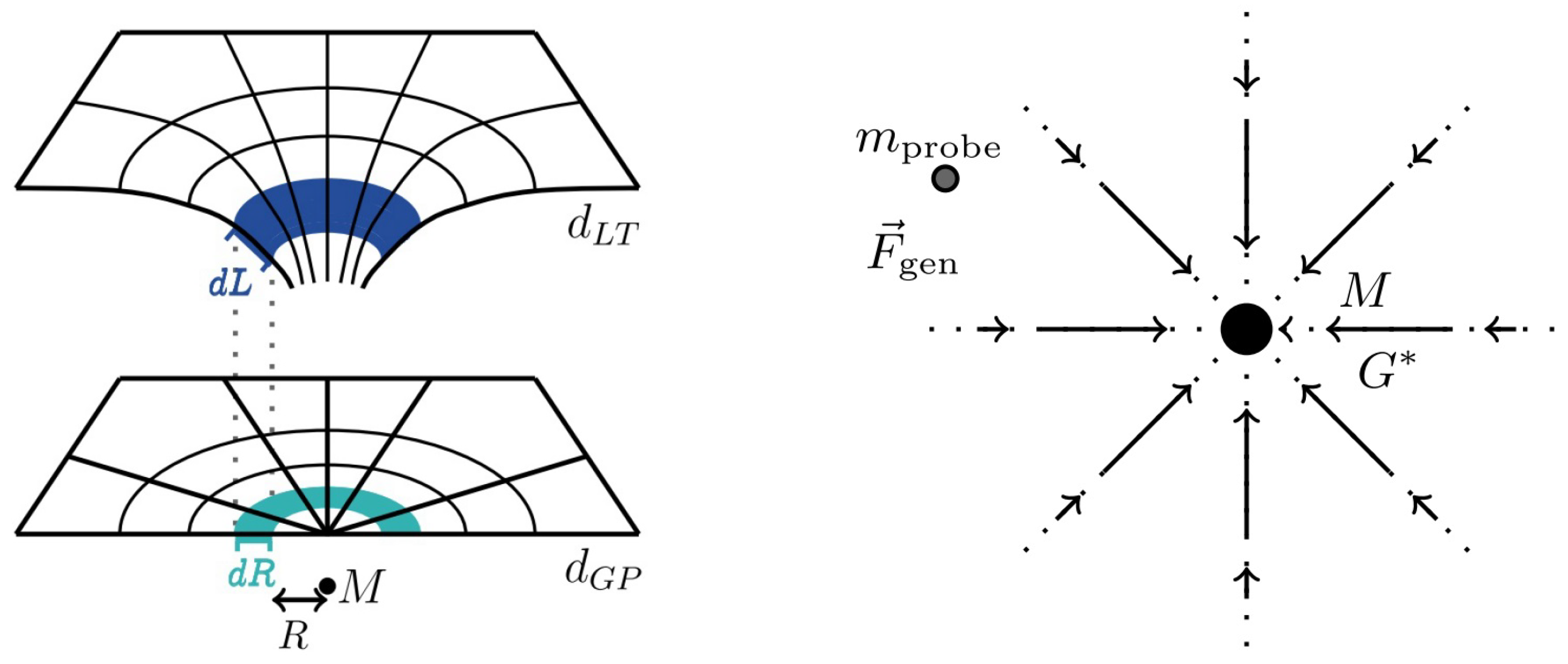

In the vicinity of a mass

M, there occurs a curvature of space, as well as an exact gravitational potential and field, see

Figure 1. Next it is shown how these phenomena are implied by the DEQ of VD:

6.1. Potential and Field

In this section, an exact generalized potential and generalized field are derived from the volume portions.

6.1.1. Generalized Potential and Field

In the vicinity of a mass

M, see

Figure 5, the unidirectional radial relative additional volume

exhibits the following properties. Hereby, spherical polar coordinates

with

M at the origin,

at

and

at

in

Figure 5 are used:

(1) For each indivisible VP , the relative additional volume propagates according to the DEQ of VD.

(1.1) That DEQ is multiplied by

c:

(1.2) At an event

, including the set

of its surrounding events in a time interval

and in a ball

, with

in the vicinity of the mass, the sum of the relative additional volume of all indivisible VPs

is applied:

(1.3) The bracket in the above DEQ has the form of a generalized potential

Hereby, the potential is generalized, as it describes volume portions, since is the relative additional volume of an indivisible VP.

(1.4) The negative gradient of that generalized potential is the generalized field

, see

Figure 5:

(1.5) Therefore, the DEQ of VD in Eq. (

60) takes the form of the following

rate gravity relation:

The potential and field in the above equation are generalized to the respective quantities for one indivisible VP

. Thereby, the potential is

and the field is as follows:

These relations are results of the VD. Formally, these results can be obtained by an application of the above average with one indivisible VP only.

For comparison, expectation values of the field have been derived from the VD as follows: Firstly, a quantum field theory has been derived from the VD. Secondly, the expectation value of a field has been derived from the quantum field theory [

23,

67].

(2) For these indivisible VPs, and for each event

, that rate gravity relation can be expressed with help of the following

rate gravity scalar:

(3) For each underlying volume

, and for each event

, with a gravitational parallax distance

R from

M, the generalized field is proportional to

:

This result is derived as follows:

(3.1) Eq. (

64) is multiplied by

. Hence, the field is as follows:

(3.2) Integration with respect to

from zero to a time

yields:

The time

is chosen so small that the integral in the above Eq. is approximated by

. Thus, the field is as follows:

(3.3) The definition

is used. The energy density

of volume is nonzero, as it is approximately the same as

, which is nonzero [

11,

12,

16]. Therefore, the indivisible VP

is proportional to the corresponding energy

. The latter is proportional to the momentum

, as each VP propagates with the speed

c, that is:

.

(3.4) The underlying volume

of a shell with center

M is considered. It is as follows:

. Thus, the field is as follows:

Hereby, the thickness of each shell is chosen constant, so that it does not dependent on R. Thence, the first fraction is constant. The 2nd fraction is the momentum current flowing through each shell. It is constant, as no shell causes any momentum. Consequently, . q. e. d.

A version of the corresponding result for a dimension

is shown in Carmesin[

67] THM 9.

(4) As M is the source of the field , that field is proportional to M: .

Thus, there is a universal constant

of proportionality:

In general, the value of a universal constant, such as , must be obtained from observation. Accordingly, is obtained in the next section. Additionally, the curvature of space is analyzed:

6.1.2. Spin, Statistics and the Additive Structure of VPs, Potentials and Fields

In general, a VP has the tensor property of a quadrupolar structure, see section (

Section 3). Consequently, it is represented by a tensor of rank two.

Therefore, at the level of quantum physics, an indivisible VP has an integer valued spin, see Landau and Lifschitz [

81], §58, Carmesin [

82]:

As a consequence, at the level of quantum physics, an indivisible VP is a boson, see Landau and Lifschitz [

81], §64, Carmesin [

82]. Consequently, at the level of quantum physics, an indivisible VP obeys the Bose [

83] statistics, alias Bose - Einstein statistics, see Landau and Lifschitz [

81], §64, Sakurai and Napolitano [

63], section 7.2.

The Bose - Einstein statistics implies that several bosons can exist at the same place. Consequently, the additional volumes

caused by different masses

can exist simultaneously at each point

P in the universe, and these

add up at

P. This, in turn, implies that the potential

at

P is the sum of these additional volumes

multiplied by

. This founds Eq. (

62) at the level of quantum physics. As a consequence of this potential, the generalized field

has the same additive structure.

6.2. Curvature in the Vicinity of a Mass

The DEQ of VD provides the curvature in the vicinity of a mass M as follows:

(1) For the case of a shell with the center

M and with the gravitational parallax radius

R, the relative additional volume

is as follows:

The resulting fraction

is called

position factor [

67]:

The fraction

is identified with the root of the radial tensor element of the metric tensor. It occurs in the vicinity of a mass

M.

More generally, at each

R, or at each event

with

, the curvature can be generalized for the case of a single indivisible VP

, with the relative additional volume

, as follows:

(2) A DEQ for the position factor is derived: For it,

is applied to Eq. (

79). This implies:

The potential

is solved for

, and this is inserted into Eq. (

82):

The gradient

is applied:

The field

is identified:

The field and the direction vector are antiparallel. Consequently, the field is as follows:

The field as a function of the mass in Eq. (

76) is used:

(3) The DEQ for the position factor is solved:

Integration by parts yields:

The integral is evaluated with a constant

K of integration:

That result is solved for the position factor:

In the limit

, there is no curvature. Consequently,

. As a consequence,

. Therefore, the solution of the DEQ provides the position factor as follows:

(4) The position factor in Eq. (

91) is compared with observation. For it, the position factor is replaced by the inverse root of the radial tensor element (see Eq.

80):

Moreover, observation shows that this inverse root of the radial tensor element is as follows [

20,

84]:

Hereby, we use the definition of the Schwarzschild radius

. The comparison of the two relations for the tensor element in Eqs. (

92 and

93) shows that the generalized universal constant

is the same as Newton’s constant of gravitation

G. Thus, the generalized field is identified with the exact gravitational field and the generalized potential is identified with the exact gravitational potential. These identified potential and field are exact, as they are derived without any approximation, and as they provide the correct curvature. This exact gravitation, derived here exactly, differs from Newton’s law of gravitation, which is an approximation.

In the vicinity of a mass, the indivisible VPs cause a generalized potential, a generalized field, the gravitational field and the curvature of space and time. The respective Eqs. are derived.

6.3. Discussion of Gravity and Curvature

In the vicinity of a mass M, the VD provides the relative additional volume as a function of r. That provides the exact gravitational potential . That exact gravitational potential provides the exact gravitational field . In the following, these valuable and insightful properties are analyzed and interpreted:

6.3.1. Transmission of the Potential and Field

The indivisible VPs

with their relative additional volume

provide a net outward propagation. Thereby, these indivisible VPs transmit a nonzero momentum, as the energy density

is positive. As a consequence, these indivisible VPs transmit the gravitational interaction. This confirms the idea of the graviton hypothesis proposed by Blokhintsev and Galperin [

65]. Moreover, these indivisible VPs explicate the mechanism of the transmission of gravity.

In addition, these indivisible VPs cause and explain the curvature of space. Thereby, the curvature is explained with help of the sum of indivisible VPs. More generally, the curvature of a single indivisible VP has been generalized, see Eqs. (

80 and

81).

6.3.2. On the Exactness of the Potential and Field

The generalized potential and field derived here are exact. In contrast, the gravitational potential is only an approximation in Newton’s theory. For instance, correction terms depending on the gravitational parallax distance

R and on the velocity

have been elaborated in Post-Newtonian approximations [

85,

86], Eq. (2.49). Accordingly, the following question arises: How is the exactness achieved here?

Essentially, this is achieved here by the application of especially useful distance measures and coordinates systems:

Firstly, for each point

P in the universe, there is an adequate coordinate system (ACS), so that an object at rest in the ACS has the absolute zero of velocity, see section (

Section 1.1.5) or Carmesin [

23,

24,

39]. This ACS is used here. As a consequence, the velocity-terms in Post-Newtonian approximation are zero.

Secondly, two measurable distance measures are used, see

Figure 1: the light travel distance

[

87], and the gravitational parallax distance

[

23,

36,

40], it can also be measured as a circumferential distance [

88,

89], section 2.6.

Hereby, according to the Hacking [

38] criterion, the light travel distance

to a field generating mass

M is real, as an increase of

M can change that distance

. In contrast, the gravitational parallax distance

to a field generating mass

M is idealized, as it represents the limit

M to zero of the light travel distance:

This is a typical idealization based on a limit [

46]. Though the gravitational parallax distance

is idealized and not real, that distance

can be measured, and that distance

provides the

law, see

Figure 5.

Thirdly, the exact potential and field are determined as follows: For the case of a point P, the idealized gravitational parallax distance from P to the field generating mass M is measured or determined by other means. With it, the potential and the field are determined as a function of , by using the respective equations in this section and paper. The result is exact, as no approximation has been used in the derivation of these equations.

In contrast, in Newton’s theory, the flatness of space has been introduced as a postulate. Accordingly, a user might use that postulate and the light travel distance , and the equations for potentials and fields in Newton’s mechanics. In such a postulate based determination of the potential or field, the result is an approximation only.

6.3.3. Advantage of the Exact Potential and Field

Altogether, the indivisible VPs cause the transmission of gravity, the exact gravitational potential, the exact gravitational field and the exact curvature of space, in an indivisible and impartible manner. Thereby, by using the adequate coordinate system and the measurable idealized gravitational parallax distance, relatively short, highly structured, and clarifying equations can be used. Moreover, the results are parts of the unification of relativity, gravity and quanta. This unification uses the relative difference , which is based on both distance measures: the real and the idealized .

7. Local Formation of Volume in Nature

In this section, the dynamics of the local formation of volume (LFV) is derived.

In the vicinity of a mass M, additional volume propagates outwards in a radial direction. Thereby, the amount of additional volume increases. Consequently, there occurs locally formed volume, LFV, or in the radial direction r. Hereby and in the following, an underlined variable marks the formed volume or the process of formation of volume. Such LFV can be caused by the mass M.

More precisely, that LFV occurs at each location. At each location, there is a gradient of the relative additional volume , or of the potential , or there is a gravitational field . As a consequence, more generally, locally, the LFV is caused by a local gravitational field. In this section, the relation between the LFV and its cause is analyzed: the field or .

7.1. Definition of Locally Formed Volume

If additional volume

forms in a volume

and in a direction

during a time

, then this process can be described by the following normalized rate of unidirectional LFV:

That LFV is described by a general law, which is derived in the next section:

7.2. Law of Locally Formed Volume

In this section, the mechanism of the local formation of volume is explained and formulated. This law of the local formation of volume is derived in section (

Section 7.3).

In the vicinity of a mass M or an effective mass , and at a based distance R from M or , the following holds for the normalized rate:

(1) In the far distance approximation, FDA, the ratio

is relatively small compared to 1. Thereby, at first order in that ratio

, the normalized rate is as follows:

Hereby,

is the component parallel to

of the generalized field.

is the cause of the rate of LFV

. More generally, each field

in a direction

causes a unidirectional normalized rate

in that direction. Moreover, this field

is equal to the exact gravitational field

, see section (

Section 6):

(2) As a consequence, the non-diagonal components do not provide additional volume.

(3) The exact value of the rate

is:

(4) More generally,

is a function

that has to be determined. The definition yields

=

. The substitution

=

=

yields

=

. The substitution

=

=

yields

=

. Using

, and

=

yields:

=

=

. Evaluation of the derivative yields

=

=

-

.

=

and

imly

(5) Eq. (

99) can be solved numerically and provides the metric in a rotation symmetric system:

7.3. Derivation of the Law of LFV

In this section, the mechanism and the law of local formation of volume are derived.

Part (1): At each radial coordinate R, a shell with center at M, and with thickness represents the analyzed volume . Thereby, the additional volume is in a shell with radius R, thickness , and volume . Similarly, the LFV is in a shell with radius R, thickness , and volume .

The LFV is analyzed at leading order in the increment . This is exact, as the increment can be made as small as desired. If the additional volume increases as a function of R, then there occurs formed volume , whereby the direction r is equal to the radial direction.

In general, the observable additional volume

in a shell with center

N, with radius

R, and with thickness

is a function of

R. Consequently, the LFV is the change of

as a function of

R. Therefore, the change

of volume in a shell with thickness

is equal to the derivative of the observable additional volume

multiplied by that thickness

:

Thereby,

is as follows:

In the

far

distance

approximation, FDA, in leading order in

,

is as follows:

With it, the derivative in Eq. (

101) is as follows:

With it, the change in Eq. (

101) is as follows:

With it, and with

, and with

, the normalized rate of unidirectional LFV in Eq. (

95) is as follows:

With it, and with

, the normalized rate of unidirectional LFV in Eq. (

106) is as follows:

The above fraction is the absolute value of the field. Thereby, the field is antiparallel to the radial unit vector

:

Application of the square yields Eq. (

97):

In the case of an effective mass, there is no rotational invariance with respect to

, in general. In that case, the proof is performed for each angular direction separately[

89] chapter 9. Moreover, each field

parallel to a direction

causes a unidirectional rate

, according to Eq. (

97).

Part (3): We analyze the rate in Eq.(

95):

The change

is the change of

As the time of propagation

is incremental, and since a field in the radial direction causes changes in the radial direction only, we can express the difference at linear order in

:

Next,

L is substituted by

R:

Next,

is used, as well as

:

The derivative is evaluated:

Each mass and each effective mass cause a gravitational field. At each location, the local gravitational field causes local formation of volume. The respective rates are expressed in Eqs. (96, 98, 99 and 107). 8. Energy Density of the Gravitational Field

In this section, the energy density of a gravitational field is introduced and derived.

8.1. Measurement of the energy density of the field

The energy density of the field can be measured as follows: A rest mass

is distributed uniformly in a shell with a radius

R and a small thickness

, see

Figure 6. That mass is lifted by a radial difference

. Thereby, the required energy

is measured. This energy is located in the field within the shell with center

M, thickness

and radius

R, see

Figure 6. That shell has the volume

Consequently, the absolute value of the measured energy density is as follows:

The positive required energy compensates the energy of the field in the shell, as the field in the shell with volume

is eliminated in the process of lifting the mass. Consequently, the sign of the field is negative:

Alternatively, this measured energy can be calculated:

8.2. Derivation of the Energy Density of the Field

The required energy

can be calculated [

67]:

The measured energy density in Eq. (

119) can be calculated by inserting Eqs. (

120 and

117) into Eq. (

119):

For comparison, [

91] derived the same formula for the energy density

Peters [

91] derived this result in a Newtonian approximation.

In contrast, the exact energy density is derived here. This is achieved with help of the exact field, since no approximation is used here. This exactness is achieved here with help of the distinction between the two distance measures: the gravitational parallax distance and the corresponding light travel distance .

8.3. Compensation of the Negative Field

The RGS in Eqs. (

67 and

70) is divided by

, and

is used:

The sum in the above Eq. is identified with the summed relative additional volume of the indivisible VPs:

With it, the RGS in Eq. (

123) is as follows:

The second fraction in the above Eq. is identified with the energy density of the gravitational field

.

As a consequence, the fraction in the above Eq. is an energy density

u. That fraction describes indivisible VPs

that cause the field. Therefore, that fraction describes the energy density of the indivisible VPs

:

Consequently, the sum of the two energy densities is zero:

The energy density of one indivisible VP is obtained by using

and by inserting the field in Eq. (

66) into Eq. (

122):

Next, the rate gravity relation (see Eqs.

67 and

70) is generalized to one indivisible VP:

Similarly, Eq. (

128) is generalized to one indivisible VP:

With these generalizations, the energy density in Eq. (

129) implies the energy density

of one indivisible VP

as follows:

These relations are results of the VD.

For comparison, expectation values of the field have been derived from the VD as follows: Firstly, a quantum field theory has been derived from the VD. Secondly, the expectation value of a field has been derived from the quantum field theory [

23,

67].

Each indivisible VP has the energy density based on its rate. Moreover, each indivisible VP causes the energy density based on its gravity. Furthermore, each indivisible VP propagates at the speed c. Accordingly, such an indivisible VP can be called rate gravity wave, RGW.

9. Derivation of the Quantum Postulates

The VD, the dynamics of the indivisible VPs, implies the SEQ, see section (

Section 5.2), the fundamental deterministic dynamics of quantum physics. Accordingly, the following question arises: Does the VD imply the stochastic dynamics of quantum systems and the complete system of quantum postulates?

In order to answer this question, the deterministic time evolution is summarized in a postulate (see

Section 9.1), and mathematical consequences (see

Section 9.2 and

Section 9.3) are derived first.

Then the stochastic dynamics (see

Section 9.4) and the complete system (see

Section 9.5) of the quantum postulates are derived.

Additional rules about mixed states and about entanglement [

64] p. 46] have been derived from the VD [

67].

9.1. Postulate about the Deterministic Time Evolution

The VD implies the postulate about the deterministic time evolution of quanta[

93] p. 170:

Postulate about the deterministic time evolution

’The time evolution of the state vector is governed by the time-dependent Schrödinger equation, SEQ[

72] Eq. (4”):

where

is the Hamilton operator corresponding to the total energy of the system.’

More generally, the VD implies the GSEQ, see section (

Section 5.2).

9.2. On Hilbert space

In this section, the solution spaces of the SEQ and of the GSEQ are analyzed, in order to derive quantum postulates in later sections. In section (

Section 5.2) it is shown, that indivisible VPs can be described by the DEQ of VD, and that indivisible VPs as well as objects at the speed

are described by the quantum physical GSEQ. In particular, objects with relatively small momentum,

, in leading order in

, are described by the SEQ.

In this section, it is shown that the solutions of the SEQ, of the GSEQ and of the DEQ of VD form Hilbert spaces:

As usual, the Dirac notation is used: A wave function is expressed by a so-called ket .

Moreover, two wave functions,

and

, form a scalar product as follows:

Hereby, the superscript * marks the complex conjugate value, this notation is nowadays usual in quantum physics [

64,

93,

96,

97].

Based on that scalar product, a state

is multiplied by a normalization factor

so that the following scalar product is equal to one:

Next, it is shown that these states form a Hilbert space :

The states

form a

complete vector space, as they are solutions of the (linear DEQ) SEQ. As a consequence, they form a linear vector space, whereby they include all linear combinations of states

, including Fourier integrals, for instance. These form a complete Hilbert space

, see e. g. Teschl[

98] p. 47 or Sakurai and Napolitano[

63] p. 57.

Generalization: The above derivation holds as well for the GSEQ, including rates of change tensors . Consequently, such wave functions form a Hilbert space as well.

Altogether, the solutions of the DEQ of volume dynamics (VD) form a Hilbert space

, the solutions of the GSEQ form a Hilbert space

, and the solutions of the SEQ form a Hilbert space

. These DEQs and their respective Hilbert spaces, can describe VPs, indivisible VPs, matter, and radiation (the case of radiation is analyzed [

67]).

9.3. On Measurements, Operators, and Possible Outcomes

In this section, the modeling of measurements with help of the above Hilbert space of the solutions of the deterministic dynamics of the GSEQ or of the SEQ is elaborated. This will be used in later sections in order to derive quantum postulates.

Firstly, the possible outcomes of a single measurement process are derived.

Secondly, the necessity of an additional dynamics is identified.

(1) In physics, in general, a measurement is described as follows:

(1.1) A measurable physical quantity A of an object is a function f of the mathematical description of that object.

(1.2) Thereby, a change of the state should be as small as possible.

(1.3) In general, the function f can be described in linear order by an operator in Hilbert space, and by a Taylor series thereof: . Thereby, the zeroth order is not essential in physics. Thus, .

Therefore, a measurable physical quantity A of an object is described by a linear operator in the Hilbert space of the states of the object.

(1.4) In the present case, the mathematical description is a state in a Hilbert space.

(1.5) In linear order in

, the function applied to the state can be expressed as follows:

(1.6) In general, each state

can be expressed as a linear combination of eigenvectors

with eigenvalues

. Here, the case of discrete and different eigenvalues

, each with one eigenvector, is analyzed in detail, as other cases can be analyzed analogously:

(1.7) In order to keep the state unchanged in a single measurement process, see part (1.2), that process must act upon an eigenvector:

Therefore, the outcome of a single measurement process of a quantity A of an object, is one of the eigenvalues of the operator corresponding to A.

(2) In general, a state is a linear combination of eigenvectors. But a possible outcome of each single measurement process is one of the eigenvalues. As a consequence, there must be a second dynamics that provides the choice of the eigenvalue that occurs in the measurement.

(2.1) The derivation of the deterministic dynamics of indivisible VPs is completely general, as only analysis alias calculus has been used in the derivation. As a consequence, a second dynamics would be deterministic, it would reduce the generality of the deterministic dynamics.

(2.2) Therefore, a general second dynamics must be a stochastic dynamics.

This stochastic dynamics is derived next:

9.4. On the Stochastic Dynamics

In this section, the stochastic dynamics is derived from the properties of the indivisible VPs.

(1) For the case of a single indivisible VP , the probability to measure an indivisible VP at an event is proportional to the energy density of the indivisible VP at that event .

(2) The energy density is related to the wave function as follows:

(2.1) For the case of a single indivisible VP

, the wave function is the time derivative of its relative additional volume, multiplied by a normalization factor

, see section (

Section 5.2):

(2.2) The absolute square is applied to the above equation:

(2.3) The above equation is multiplied by

:

(2.4) In the above equation, the second fraction is identified with the energy density of the indivisible VP

:

(3) As a consequence, the probability

to measure an indivisible VP at an event

is proportional to the absolute square of the wave function:

(4) For each measurable quantity

A, and for the corresponding operator

, the probability to measure an eigenvalue

of an eigenvector

has been derived from the result in part (3) or in Eq. (

143) [

67].

Therefore, the result in part (3) or in Eq. (

143) is the fundamental stochastic dynamics of quantum physics.

(5) As a consequence, the VD implies both, deterministic time evolution as well as the stochastic dynamics of quantum physics. Consequently, the VD implies the full dynamics of quantum physics. This is the case, as for their respective systems, quantum field theory and the Dirac theory can both be derived with help of the above deterministic and stochastic dynamics [

23,

63,

67,

89,

101].

Using the above mathematical results as well as the deterministic and stochastic dynamics, the postulates of quantum physics are derived next:

9.5. Derivation of the Postulates

In this section, it is shown how the quantum postulates [

93] are implied by the VD:

(1) The postulate about the

deterministic time evolution has been derived in sections (

Section 5.2 and

Section 9.1).

(2) The postulate about

probabilistic outcomes of measurements is as follows[

93] p. 169, 170:

’If a measurement of an observable A is made in a state of the quantum mechanical system, then the following holds:

[1] The probability of obtaining one of the non-degenerate discrete eigenvalues

of the corresponding operator

is given by

where

is the eigenfunction of

with the eigenvalue

. If the state vector is normalized to unity,

.

[2] If the eigenvalue

is

-fold degenerate, this probability is given by

[3] If the operator

possesses a continuous eigenspectrum

, the probability that the result of a measurement will yield a value between

a and

is given by

This postulate can be derived from the stochastic dynamics in section (

Section 9.4). The derivation is presented in Carmesin [

67,

101,

103].

(3) The postulate about

Hilbert space is as follows[

93] p. 168:

’The state of a quantum mechanical system, at a given instant of time, is described by a vector , in the abstract Hilbert space of the system.’

For each given state of a quantum mechanical system, the full dynamics should be determined. It is the deterministic and stochastic dynamics in the above postulates (1) and (2). It has been shown here, that the states of the respective Hilbert space provide the full information to derive the deterministic time evolution (with the SEQ or with the GSEQ, more generally), and to derive the correct probabilities for the probabilistic outcomes. Therefore, ’the state of a quantum mechanical system, at a given instant of time, is described by a vector , in the abstract Hilbert space of the system’.

Moreover, it is insightful to realize that the correct probabilistic outcomes are a consequence of the gravitational properties of the VD. Therefore, it is enlightening to understand that the basis of the quantum postulates is a quantum gravitational foundation. As a consequence, a deep and fundamental understanding of quantum physics without understanding gravity and quantum gravity is hardly possible.