1. Introduction

Homicide, defined as the intentional killing of one person by another, encompasses both impulsive and premeditated acts (UNODC 2023). Intentional killings constitute the most severe form of interpersonal violence due to the inherent element of planning and deliberation (Ireland et al. 2018). The multiplicity of behavioral and situational factors involved, such as weapon use, demonstrates the complexity of this phenomenon (Payne and Byard 2023), necessitating a nuanced, multidisciplinary approach to effectively understand and address its root causes.

From an economic and social perspective, homicides represent an irreversible loss of human capital and a significant contraction of the labor force, as they disproportionately affect adolescents and young adults (Peñaherrera et al. 2019; Sanhueza et al. 2023). Furthermore, lethal violence hinders sustainable development by eroding the social fabric, fostering collective fear, undermining community cohesion, and diminishing public trust in state institutions (Stuart and Taylor 2021; Lanfear 2022). Political instability, the institutional weakness of security forces, and fragmented judicial systems further compound the problem (Chainey et al. 2021; Sanhueza et al. 2023). These effects are intensified in contexts characterized by high levels of inequality, social disintegration, and poverty, where organized crime poses a persistent threat (Tuttle 2021; Itskovich 2024).

Homicides associated with organized crime constitute a pressing global challenge, particularly in developing countries in Central and South America, which report some of the highest rates globally (Jaitman 2019; UNODC 2023). Although government responses have varied, with notable exceptions such as El Salvador (Paradela and Antón 2025; Kurylo 2025), the effectiveness of these strategies remains an unresolved challenge (Croci and Chainey 2022; Croci et al. 2025).

In recent years, the Republic of Ecuador has witnessed an exponential rise in homicide rates, placing it among the most violent countries in Latin America. The rate surged from 5.82 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2019 to 44.5 in 2023, reflecting a profound deterioration in public safety (Concha et al. 2020; Tello 2025). Territorial analyses reveal those provinces on the Pacific coast (Ramos et al. 2024) and in the Amazon region (Ortiz et al. 2022) exhibit homicide rates significantly exceeding the national average. Primary drivers of this trend include disputes over territorial control and competition in micro-drug trafficking markets among criminal organizations, cartels, and gangs (García 2024).

Various repressive interventions have been implemented to tackle homicides linked to organized crime; however, evidence indicates that achieving effective and sustainable mitigation requires a comprehensive understanding of the underlying dynamics and the implementation of coordinated, evidence-based strategies. Empirical research demonstrates that low educational attainment, high unemployment, and social exclusion increase individual risks of victimization and foster environments conducive to lethal violence in contexts of structural inequality (Pare and Felson 2014; Jaitman 2019; Gaitán and Velázquez 2021; Zungu and Mtshengu 2023; Itskovich 2024). Consequently, improving quality of life standards, promoting economic development, and expanding formal employment are essential prerequisites for reducing homicide rates (Vásquez et al. 2023).

While the available literature provides valuable insights into the national situation at the provincial level, critical determinants remain insufficiently explored and require a more geographically disaggregated analysis. In particular, it is imperative to examine localities characterized by socioeconomic inequalities that could contribute to the persistence of interpersonal violence. Therefore, this research aims to identify the relationship between homicides and adverse socioeconomic conditions in specific micro-territories within the country. By testing this hypothesis, the study seeks to inform the design of targeted social programs for priority areas of intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Territorial Organization

The Republic of Ecuador, which reported a population of 16,938,986 inhabitants in the 2022 national census (INEC 2024), is organized territorially into distinct administrative levels of planning (SENPLADES 2012). The national territory is segmented into nine zones, each comprising geographically proximate provinces. These zones are subdivided into “districts”, corresponding to one or more cantons (similar to municipalities), for a total of 140. In turn, each “district” is divided into “circuits”, equivalent to one or more parishes, amounting to 1,134 in total. In this context, a parish can be understood as a group of adjacent neighborhoods or communities. This territorial structure facilitates the provision of public services tailored to local socioeconomic characteristics, thereby enabling more effective and relevant responses to the population’s needs (Gallegos et al. 2021). Although an additional level of disaggregation known as “subcircuits” exists, this study focuses exclusively on the “circuit” level due to the unavailability of granular data within the consulted sources. Nevertheless, the “circuit” level provides a robust unit of analysis and serves as an adequate baseline for the prioritization of governmental interventions.

2.2. Design

An exploratory ecological study was designed, employing the 67 “circuits” comprising the 12 districts of Zone 8 of the Republic of Ecuador as the primary unit of analysis. These micro-territories are situated in the southwestern coastal region of the country, specifically within the province of Guayas, which encompasses the cantons of Guayaquil, Durán, and Samborondón.

This metropolitan area has experienced substantial demographic expansion, registering a growth of 59.7% relative to the 2010 census (INEC 2010; INEC 2024). Currently, the region concentrates 25.9% of the country’s total population, representing a total of 4,391,923 inhabitants.

2.3. Data Sources

The study utilized publicly available open-access data, which constitute the sole sources of information providing territorial disaggregation at the “circuit” level. First, administrative records from the National Police, compiled by the Directorate of Statistics and Security Economics (Ministry of the Interior 2025), were analyzed. This dataset encompasses cases of intentional homicides recorded in each “circuit” spanning the period from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2024. During this timeframe, the selected circuits registered a cumulative total of 9,713 intentional homicides, accounting for 31.8% of the national figure. Second, data regarding population and socioeconomic conditions at the “circuit” level were derived from estimates generated by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses, based on the 2010 Population Census (INEC 2010) and the 2013–2014 Living Conditions Survey (INEC 2014). These estimates incorporate key indicators such as the poverty rate and inequality, the latter measured by the Gini coefficient. Both socioeconomic indicators have been widely validated in extant literature to analyze their association with homicide rates (Mohammadi et al. 2022; López et al. 2024; Büttner 2025), as higher levels of poverty and inequality within a locality are consistently associated with an increased incidence of crime and violence, and consequently, elevated homicide rates.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis proceeded in distinct stages. First, a unified database was constructed for the 67 “circuits,” verifying the internal consistency of the data. Second, the 10-year cumulative incidence rate of homicide per 1,000 inhabitants was computed for each “circuit”. Third, a descriptive analysis was executed employing measures of central tendency and dispersion to characterize the distribution of homicide rates and socioeconomic indicators. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was applied to evaluate the associations between the socioeconomic indicators (predictor variables) and the homicide rate (dependent variable). The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Data processing and analysis were performed using Jamovi software (version 2.3.21.0). Finally, based on the mean values of the indicators, scatter plots were generated to categorize the “circuits” into four intervention quadrants (1°, 2°…), thereby identifying those in which the convergence of adverse socioeconomic conditions and high homicide rates signified the highest level of social vulnerability.

2.4. Program Design and Proposal

To address the second objective of this study, a narrative review of the scientific literature was undertaken to identify evidence-based interventions for reducing homicides in contexts characterized by poverty and inequality. For this purpose, AI-enhanced search functionalities available within the multidisciplinary databases Scopus and ScienceDirect were utilized. The synthesized evidence serves as a theoretical baseline for the design of the proposed intervention program.

3. Results

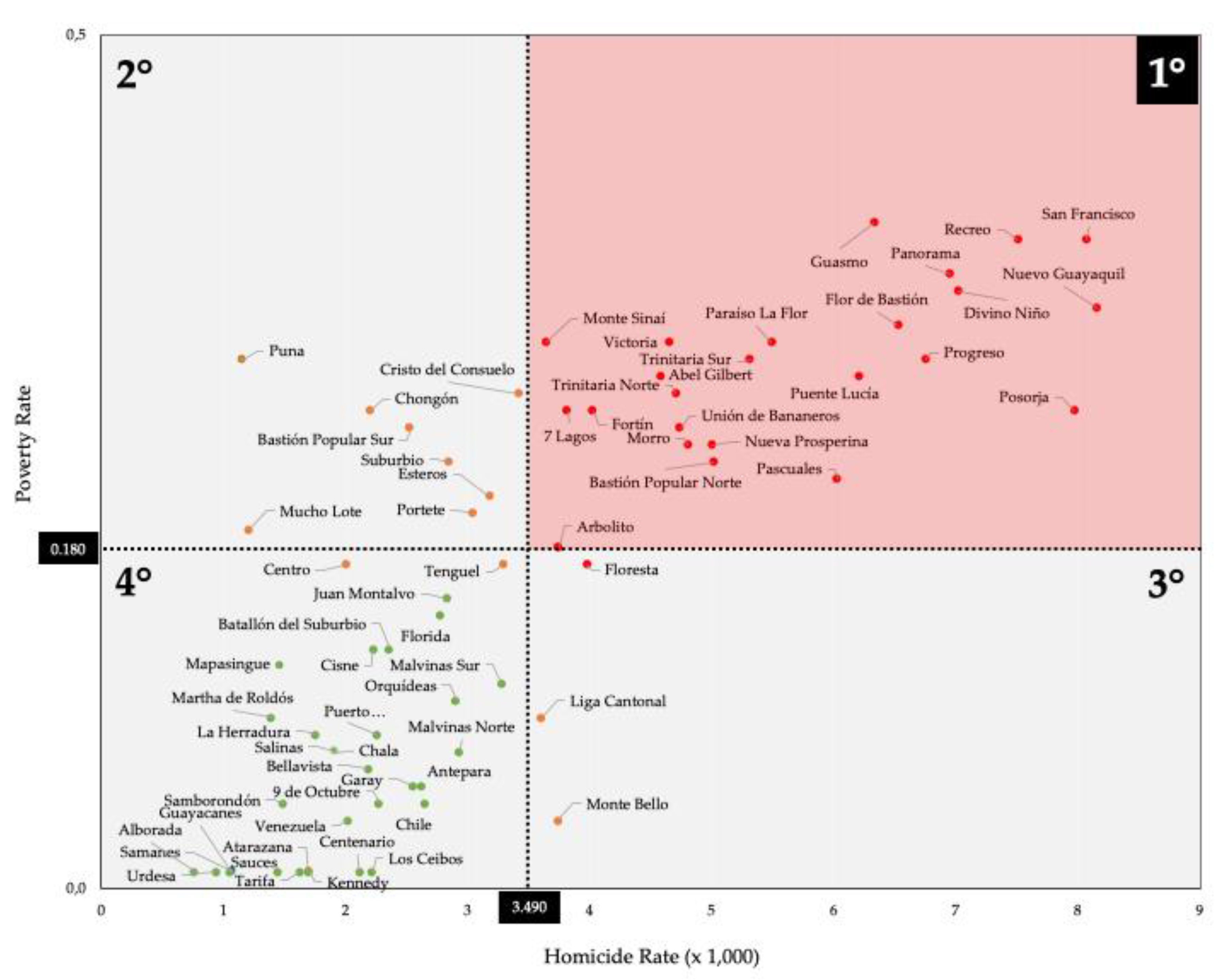

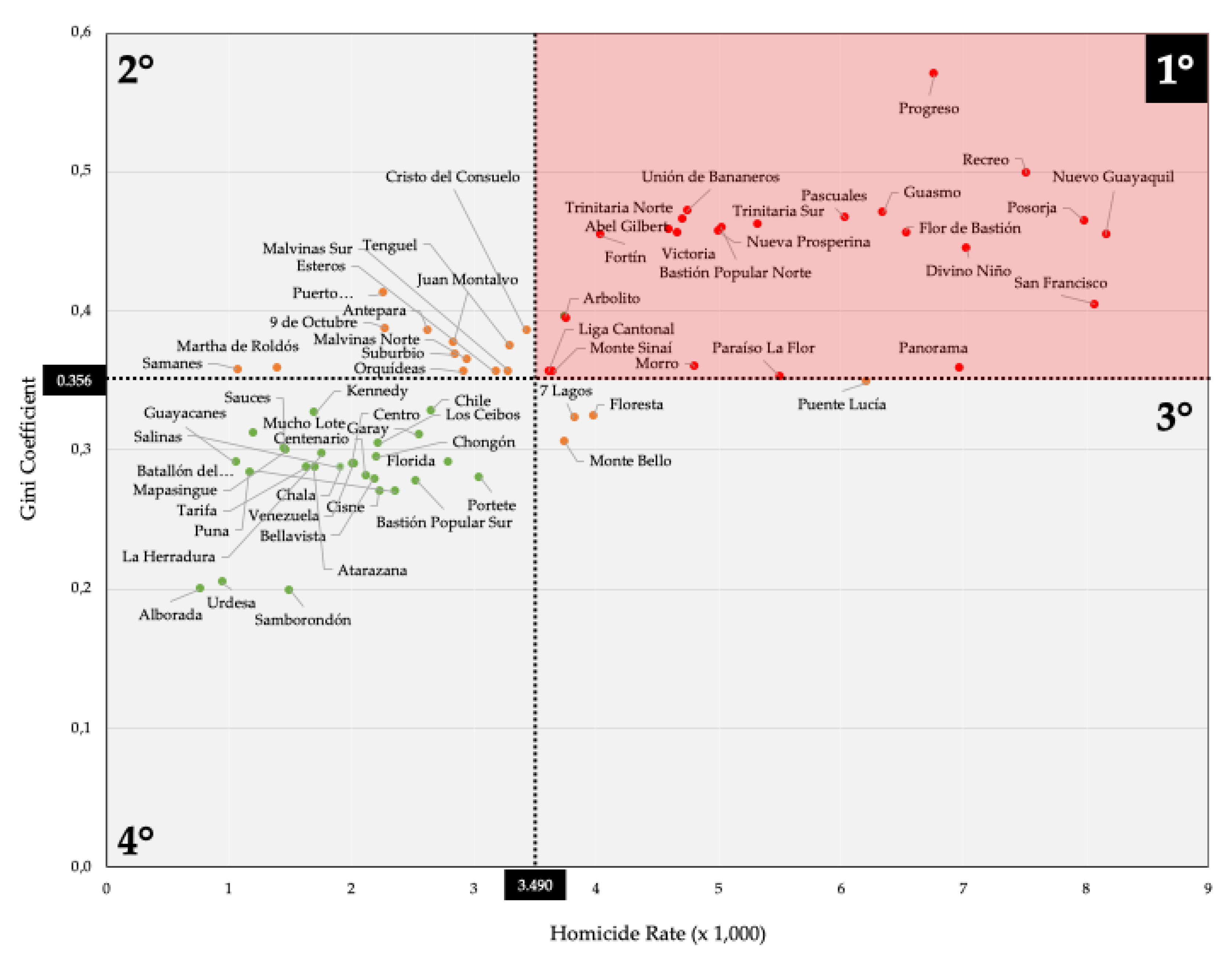

Among the 67 “circuits” analyzed, 27 registered homicide rates exceeding the mean (3.49 per 1,000 inhabitants; 95% CI: 3.01–3.97) (see

Table 1 and

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). The highest rates were documented in the “circuits” of Nuevo Guayaquil (8.16), San Francisco (8.07), and Posorja (7.98), whereas the lowest were recorded in Alborada (0.76), Urdesa (0.94), and Guayacanes (1.06).

The average poverty rate was 0.18, with a heterogeneous distribution across the “circuit” (see

Figure 1). Approximately one-third of the population lives under poverty conditions. The highest values were recorded in the “circuit” of Guasmo (0.39), San Francisco and Recreo (0.38), Panorama (0.36), and Divino Niño (0.35), in contrast to the lowest in Urdesa (0.01), Alborada (0.01), and Samborondón (0.05). A similar pattern of heterogeneity was observed for the Gini coefficient, with a mean value of 0.35 (see

Figure 2).

Figure 1 shows the classification of “circuit” into priority intervention quadrants, based on the combination of poverty and homicide rates. The upper right quadrant (1°) contains the most vulnerable “circuits”, characterized by high levels of poverty and high homicide rates. Similarly,

Figure 2 shows the relationship between the Gini coefficient and the homicide rate, where the upper right quadrant (1°) contains the most vulnerable “circuit”, i.e., those with high levels of inequality and homicides. The correlation analysis revealed positive and statistically significant associations between the homicide rate and both the poverty rate and the Gini coefficient (see

Table 1).

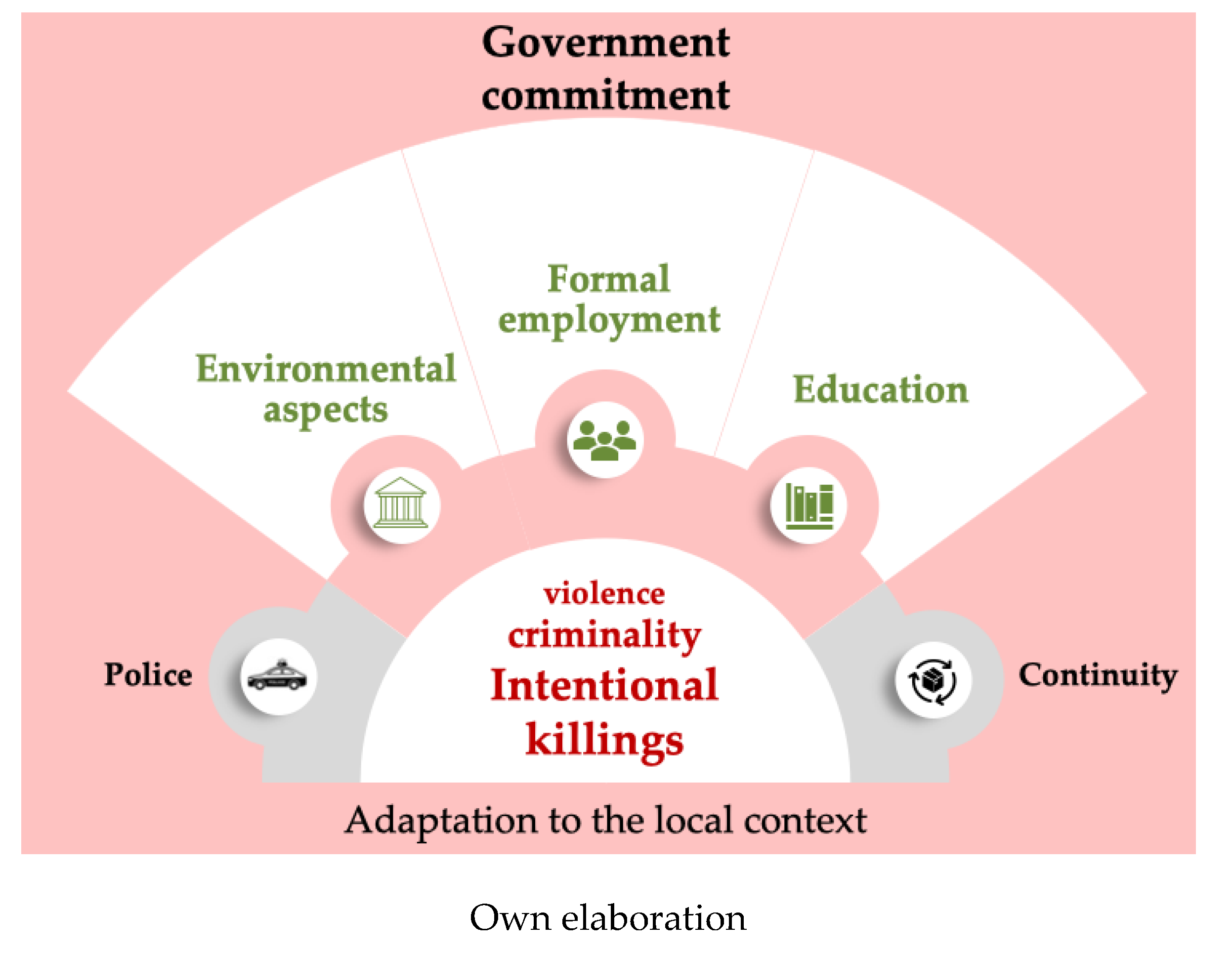

The literature review addressed the following central question: What interventions have demonstrated efficacy in reducing homicide rates in contexts characterized by poverty and social inequality? The identified studies were categorized into three main dimensions of effective intervention: (1) environmental improvements, (2) job creation, and (3) educational initiatives. Additionally, police presence and the continuity of interventions are recognized as key factors in achieving sustainable and significant reductions in homicide rates (see

Figure 3). The Discussion section will elaborate on effective interventions and will present images of the most problematic “circuits” (see

Figure 4).

4. Discussion and Conclusions

The results demonstrate a statistically significant relationship between socioeconomic indicators and homicides in the 67 “circuits” of the province of Guayas, Republic of Ecuador. Crucially, the analysis at the “circuit” level facilitates the identification of the most vulnerable territories that require special attention and priority intervention.

The literature review establishes a coherent framework of interventions that have proven efficacious in reducing homicides in similar contexts (see

Figure 3). The evidence indicates that improving the urban environment of neighborhoods is an effective strategy for reducing violence and homicide rates. The most effective interventions include optimizing road infrastructure (

Cerdá et al 2012), strengthening public lighting (

Martínez et al. 2018;

Rajan et al. 2022;

Monika and Kumar 2025), and creating or restoring common spaces such as parks and green areas (

Shepley et al. 2019;

Pearson et al. 2022). These actions increase citizens’ perceived safety and promote social cohesion and community ownership of urban spaces, which are recognized as protective factors against crime. For instance,

Figure 4a depicts the Monte Sinaí “circuit”, showing a settlement consisting of informal dwellings built with heterogeneous materials, located on uneven terrain with slopes, unpaved roads, and limited basic services. Although there are utility poles and power lines intended to supply the dwellings, they lack public lighting.

Figure 4b further illustrates an urban settlement whose dwellings are organized around a degraded central plot of land, which holds potential for adaptation as a public space.

Furthermore, the creation of formal employment mitigates socioeconomic inequality and, consequently, decreases the likelihood of involvement in criminal activities in marginalized areas (

Rowhani et al. 2022;

Khanna et al. 2023;

Rostad et al. 2024). Programs targeting young people are particularly noteworthy, as they have shown effectiveness in preventing antisocial behavior and violent crime (

Anser et al. 2020;

Thulin et al., 2022;

Joseph and Jay 2025).

Figure 4c–d demonstrates that, in most “circuits”, the working population engages in activities associated with informal employment on public roads.

Figure 4.

Photos of “circuits” in upper right quadrant, 1°.

Figure 4.

Photos of “circuits” in upper right quadrant, 1°.

Education constitutes a fundamental pillar for strengthening the social fabric in vulnerable contexts and plays a central role in violence and crime prevention strategies. Specifically, research highlights that early school-based interventions foster the development of skills such as self-regulation and peaceful conflict resolution, thereby reducing the likelihood of aggressive behavior during adolescence (Bray et al 2020; Payne 2025). Workshops focused on anger management, emotional education, and peaceful coexistence have demonstrated positive effects on modifying attitudes and behaviors among young people (Webster et al. 2013; Milam et al. 2018; Circo et al. 2020). Ultimately, an accessible, equitable, and high-quality education system with an emphasis on civic values and coexistence is crucial to mitigating risk factors associated with violent behavior.

In the domain of crime control and deterrence, research suggests that strengthening police presence and increasing the number of officers through targeted patrols in high-incidence areas yields positive results (Grinshteyn et al. 2016; Mangai et al. 2024; Mancha 2025). Strategies implemented in other contexts, such as focusing on individuals or groups involved in violent behavior and clearly disseminating legal norms, have equally proven efficacious. Furthermore, professionalism and ongoing police training are critical components contributing to reductions in violent crime (Bearfield et al. 2020).

Crucially, the effectiveness of all interventions is contingent upon a comprehensive approach underpinned by sustained governmental commitment, particularly in socially disadvantaged areas. Achieving this goal necessitates the allocation of adequate resources, the coordination of intersectoral programs, and the guarantee of public policy continuity (Atienzo et al. 2017; Chainey et al. 2021; Alcocer 2025).

This study is subject to limitations that should be duly considered when interpreting the results. First, the inherent characteristics of the ecological design prevent the establishment of direct causal relationships between the variables analyzed and pose the risk of ecological fallacy. Likewise, it was not feasible to incorporate or control for potential confounders that influence homicide dynamics, which may impact the accuracy of the associations observed. Nonetheless, the analysis identified statistically consistent patterns between socioeconomic indicators and the homicide rate at the “circuits” level. Second, given that an exhaustive systematic review of the literature was not conducted, it is acknowledged that not all existing evidence on effective interventions for homicide reduction was covered. Nevertheless, the actions included in

Figure 3 offer useful guidance for the design of intervention programs in the “circuits” identified as most vulnerable and prioritized (upper-right quadrant, 1°,

Figure 1 and

Figure 2). Finally, although the exact figures for poverty and inequality by “circuit” may have varied, the trend in these variables tends to persist over time. Therefore, the use of previous reference data is justified in light of the absence of more recent census data.

In conclusion, this study constitutes a relevant and timely contribution to the current debate regarding the citizen security crisis and homicide violence in the Republic of Ecuador, by shifting the focus toward a frequently overlooked level of territorial analysis: the micro-territories or “circuits” within the most disadvantaged areas. By moving beyond provincial generalizations, this research substantiates that lethal violence is not random; instead, it is heavily concentrated in specific territories characterized by profound structural inequalities, thereby enabling the precise identification of priority intervention quadrants.

Beyond the ecological and exploratory scope of this study, the findings strongly underscore the urgent need to transition toward a multisectoral social dialogue. The evidence suggests that the state response must transcend a purely reactive approach to mandate comprehensive strategies that integrate environmental interventions (recovery of public space and infrastructure), economic initiatives (local employment generation for youth), and educational programs (violence prevention and social cohesion).

Ultimately, the sustainable pacification of Zone 8 mandates a new social pact. It is imperative that targeted policies be directed toward these critical sectors, where articulated collaboration between the State, the private sector, and the community must move beyond rhetoric to become the indispensable operational foundation for rebuilding the social fabric and guaranteeing lasting security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; methodology, R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; software, R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; writing—original draft preparation, R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; writing—review and editing, R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; visualization, R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; supervision, R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G.; project administration, R.H.B.V. and A.R.G.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study can be found in the Materials and Methods section.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alcocer, M. 2025. Increasing intergovernmental coordination to fight crime: evidence from Mexico. Political Science Research and Methods, 13(3), 745-754. [CrossRef]

- Anser, M., Yousaf, Z., Nassani, A., Alotaibi, S., Kabbani, A., and Zaman, K. 2020. Dynamic linkages between poverty, inequality, crime, and social expenditures in a panel of 16 countries: two-step GMM estimates. Journal of Economic Structures, 9, 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Atienzo, E.E., Baxter, S.K. & Kaltenthaler, E. 2017. Interventions to prevent youth violence in Latin America: a systematic review. Int J Public Health, 62, 15–29. [CrossRef]

- Bearfield, D., Maranto, R., & Wolf, P. J. 2020. Making Violence Transparent: Ranking Police Departments in Major U.S. Cities to Make Black Lives Matter. Public Integrity, 23(2), 164–180. [CrossRef]

- Bray, M. J. C., Boulos, M. E., Shi, G., et al. 2020. Educational achievement and youth homicide mortality: a City-wide, neighborhood-based analysis. Injury Epidemiology, 7, 20. [CrossRef]

- Büttner, N. 2025. Local inequality and crime: New evidence from South Africa. Journal of Economic Inequality. [CrossRef]

- Cerdá, M., Morenoff, J. D., Hansen, B. B., Tessari Hicks, K. J., Duque, L. F., Restrepo, A., and Diez-Roux, A. V. 2012. Reducing violence by transforming neighborhoods: a natural experiment in Medellín, Colombia. American journal of epidemiology, 175(10), 1045–1053. [CrossRef]

- Chainey, S. P., Croci, G., and Rodriguez Forero, L. J. (2021). The Influence of Government Effectiveness and Corruption on the High Levels of Homicide in Latin America. Social Sciences, 10(5), 172. [CrossRef]

- Circo, G. M., Krupa, J. M., McGarrell, E., and De Biasi, A. 2020. Focused Deterrence and Program Fidelity: Evaluating the Impact of Detroit Ceasefire. Justice Evaluation Journal, 4(1), 112–130. [CrossRef]

- Concha-Eastman, A. , Muñoz, E., and Rennó-Santos, M. 2021. Homicides in Latin America and the Caribbean. En X. Bada & L. Rivera-Sánchez (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Sociology of Latin America. Oxford University Press. [CrossRef]

- Croci, G., and Chainey, S. 2022. An institutional perspective to understand Latin America’s high levels of homicide. British Journal of Criminology, 62(5), 1199–1218. [CrossRef]

- Croci, G. , Dammert, L., & Larroca, M. 2025. From Safe Havens to Hotspots: The Spread of Organised Crime Violence in Latin America. En R. P. Cavalcanti, D. S. Fonseca, V. Vegh Weis, K. Carrington, J. Hogg and J. Scott (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Criminology and the Global South. Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Gaitán-Rossi, P., and Velázquez Guadarrama, C. 2021. A systematic literature review of the mechanisms linking crime and poverty. Convergencia, 28, e14685. [CrossRef]

- Gallegos Rojas, R. X., Quiroz Castro, C. E., and Celi Masache, M. E. 2021. Descentralización y desconcentración. Análisis y perspectivas. Sur Academia, 8(16). [CrossRef]

- García-Ponce, O. 2024. Can Ecuador Avoid Becoming a Narco-State? Current History, 123(850), 56–62. [CrossRef]

- Grinshteyn, E. G., Eisenman, D. P., Cunningham, W. E., Andersen, R., & Ettner, S. L. 2016. Individual- and Neighborhood-Level Determinants of Fear of Violent Crime Among Adolescents. Family & community health, 39(2), 103–112. [CrossRef]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos – INEC. 2010. Memorias del Censo de Población y de Vivienda 2010. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/wp-content/descargas/Libros/Memorias/memorias_censo_2010.pdf.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos – INEC. 2014. Tabulados mapas de distritos. Available online: https://www.ecuadorencifras.gob.ec/documentos/web-inec/Estudios%20e%20Investigaciones/Pobreza_y_desdigualdad/Mapas_de_Pobreza/Tabulados_mapasdistritos.xlsx.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos – INEC. 2024. VIII Censo de Población y VII de Vivienda 2022: Reporte técnico. Available online: https://www.censoecuador.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/CPV_2022_Reporte_Tecnico_mar2024.pdf.

- Ireland, J., Birch, P., and Ireland, C. (Eds.). 2018. The Routledge International Handbook of Human Aggression: Current Issues and Perspectives (1st ed.). Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Itskovich, E. 2024. Economic Inequality, Relative Deprivation, and Crime: An Individual-Level Examination. Justice Quarterly, 42(4), 637–658. [CrossRef]

- Jaitman, L. 2019. Frontiers in the economics of crime: lessons for Latin America and the Caribbean. Latin American Economic Review, 28, 19. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, P. L., and Jay, J. 2025. Summer Youth Employment Programs as a Structural Approach to Prevent Youth Violence: An Integrative Review. Prevention science: the official journal of the Society for Prevention Research, 10.1007/s11121-025-01840-9. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, G., Medina, C., Nyshadham, A., Tamayo, J., and Torres, N. 2023. Formal Employment and Organised Crime: Regression Discontinuity Evidence from Colombia. The Economic Journal, 133(654), 2427-2448. [CrossRef]

- Kurylo, B. 2025. The flawed appeal of the Bukele method in the Americas. Conflict, Security & Development, 25(2), 209–249. [CrossRef]

- Lanfear, C. C. 2022. Collective efficacy and the built environment. Criminology, 60(2), 370–396. [CrossRef]

- López-Ortiz, E. , Altamirano, J. M., Romero-Henríquez, L. F., & López-Ortiz, G. 2024. Characterization of Homicides in Mexico: Analysis of 2015–2022. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 21(5), 617. [CrossRef]

- Mancha, A. 2025. When the State steps down: Reduced police surveillance and gang-related deaths in Brazil. World Development, 189, 117215. [CrossRef]

- Mangai, M. S., Masiya, T., & Masemola, G. 2024. Engaging communities as partners: policing strategies in Johannesburg. Safer Communities, 23(1), 86-102. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, L., Prada, S., and Estrada, D. 2018. Homicides, Public Goods, and Population Health in the Context of High Urban Violence Rates in Cali, Colombia. Journal of urban health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 95(3), 391–400. [CrossRef]

- Milam, A. J., Furr-Holden, C. D., Leaf, P., and Webster, D. 2018. Managing Conflicts in Urban Communities: Youth Attitudes Regarding Gun Violence. Journal of interpersonal violence, 33(24), 3815–3828. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of the Interior, Ecuador. 2025. Datos históricos de homicidios intencionales 2014–2024. Available online: https://datosabiertos.gob.ec/dataset/homicidios-intencionales/resource/36b055c8-e10c-4e57-ba25-3046ca5ef15d.

- Mohammadi, A., Bergquist, R., Fathi, G., Pishgar, E., de Melo, S. N., Sharifi, A., & Kiani, B. 2022. Homicide rates are spatially associated with built environment and socio-economic factors: a study in the neighbourhoods of Toronto, Canada. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1482. [CrossRef]

- Monika, E., and Kumar, T. R. 2025. Evaluating the Impact of Public Safety Measures on Crime Reduction: A Historical Data Perspective. 2025 8th International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), 1690-1696. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Prado, E., Villagran, P., Martinez-Abarca, A. L., et al. 2022. Female homicides and femicides in Ecuador: a nationwide ecological analysis from 2001 to 2017. BMC Women’s Health, 22, 260. [CrossRef]

- Paradela López, M., and Antón, J.-I. 2025. Has the iron fist against criminal gangs really worked in El Salvador? Defence and Peace Economics. [CrossRef]

- Pare, P. P., and Felson, R. 2014. Income inequality, poverty and crime across nations. The British Journal of Sociology, 65(3), 434–458. [CrossRef]

- Payne-James, J., and Byard, R. W. (Eds.). 2023. Forensic and legal medicine: Clinical and pathological aspects (1st ed.). CRC Press. [CrossRef]

- Payne, A. A. 2025. The Search for Social Justice in School-Based Crime and Delinquency Prevention. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 714(1), 97-113. [CrossRef]

- Pearson, A., Sanciangco, J., Wang, Y., Breetzke, G., Lin, Z., and Clevenger, K. 2022. The Relationship Between City “Greenness” and Homicide in the US: Evidence Over a 30-Year Period. Environment and Behavior, 54(2), 538–571. [CrossRef]

- Peñaherrera-Aguirre, M., Hertler, S. C., Figueredo, A. J., Fernandes, H. B. F., Cabeza de Baca, T., and Matheson, J. D. 2019. A social biogeography of homicide: Multilevel and sequential canonical examinations of intragroup unlawful killings. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 158–181. [CrossRef]

- Rajan, S., Reeping, P. M., Ladhani, Z., Vasudevan, L. M., and Branas, C. C. 2022. Gun violence in K-12 schools in the United States: Moving towards a preventive (versus reactive) framework. Preventive medicine, 165(Pt A), 107280. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, L., Román, K., and Amaro, I. R. 2024. An Exploratory Data Analysis of the Ecuadorian Security Crisis: Insights from 2021 and 2022. In M. V. Garcia, C. Gordón-Gallegos, A. Salazar-Ramírez & C. Nuñez (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Science, Electronics and Industrial Engineering (CSEI 2023) (Vol. 775). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Rostad, W. L., Gonzalez, A., and Ports, K. A. 2024. The Relationship Between State-Level Earned Income Tax Credits and Violent Crime. Prevention Science, 25, 878–881. [CrossRef]

- Rowhani-Rahbar, A., Schleimer, J. P., Moe, C. A., Rivara, F. P., and Hill, H. D. 2022. Income support policies and firearm violence prevention: A scoping review. Preventive Medicine, 165, 107133. [CrossRef]

- Sanhueza, A., Caffe, S., Araneda, N., Soliz, P., San Román-Orozco, O., and Baer, B. 2023. Homicide among young people in the countries of the Americas. Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública, 47, e108. [CrossRef]

- Secretaría Nacional de Planificación y Desarrollo – SENPLADES). 2012. Folleto informativo: Desconcentración — niveles administrativos de planificación (zonas, distritos, circuitos). Available online: https://www.planificacion.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/10/Folleto_informativo-Desconcentracion2012.pdf.

- Shepley, M., Sachs, N., Sadatsafavi, H., Fournier, C., and Peditto, K. 2019. The Impact of Green Space on Violent Crime in Urban Environments: An Evidence Synthesis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(24), 5119. [CrossRef]

- Stuart, B. A., and Taylor, E. J. (2021). The Effect of Social Connectedness on Crime: Evidence from the Great Migration. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 103(1), 18–33. [CrossRef]

- Tello Toapanta, J. C. 2025. Operational Approach to Combat Drug Trafficking Within the Framework of Non-international Armed Conflict in Ecuador. In G. F. Olmedo Cifuentes, D. G. Arcos Avilés and H. V. Lara Padilla (Eds.), Emerging Research in Intelligent Systems. CIT 2024. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems (Vol. 1348). Springer. [CrossRef]

- Thulin, E. J., Lee, D. B., Eisman, A. B., Reischl, T. M., Hutchison, P., Franzen, S., and Zimmerman, M. A. 2022. Longitudinal effects of Youth Empowerment Solutions: Preventing youth aggression and increasing prosocial behavior. American journal of community psychology, 70(1-2), 75–88. [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, J. (2021). Inequality, concentrated disadvantage, and homicide: Towards a multi-level theory of economic inequality and crime. Deviant Behavior, 43(2), 215–232. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime – UNODC. 2023. Global Study on Homicide 2023: Homicide and organized crime in Latin America and the Caribbean. Available online: https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/gsh/2023/GSH_2023_LAC_web.pdf.

- Vásquez, A., Alvarado, R., Tillaguango, B., et al. (2023). Impact of Social and Institutional Indicators on the Homicide Rate in Ecuador: An Analysis Using Advanced Time Series Techniques. Social Indicators Research, 169, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Webster, D. W., Whitehill, J. M., Vernick, J. S., and Curriero, F. C. 2013. Effects of Baltimore’s Safe Streets Program on gun violence: a replication of Chicago’s CeaseFire Program. Journal of urban health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 90(1), 27–40. [CrossRef]

- Zungu, L. T., and Mtshengu, T. R. 2023. The Twin Impacts of Income Inequality and Unemployment on Murder Crime in African Emerging Economies: A Mixed Models Approach. Economies, 11(2), 58. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).