Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

2.2. Fungal Growth and Inoculation of Tomato Plants

2.3. Low Temperature Treatment

2.4. Visual Damage

2.5. Histochemical Detection of Hydrogen Peroxide

2.6. Catalase Activity

2.7. Soluble Sugar Content

2.8. Proline Content

2.9. Stomatal Traits

2.10. Colony Forming Units (CFU) Counting

2.11. Evaluation of the Effect of Temperature on the Mycelial Growth Rate of Trichoderma asperellum

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

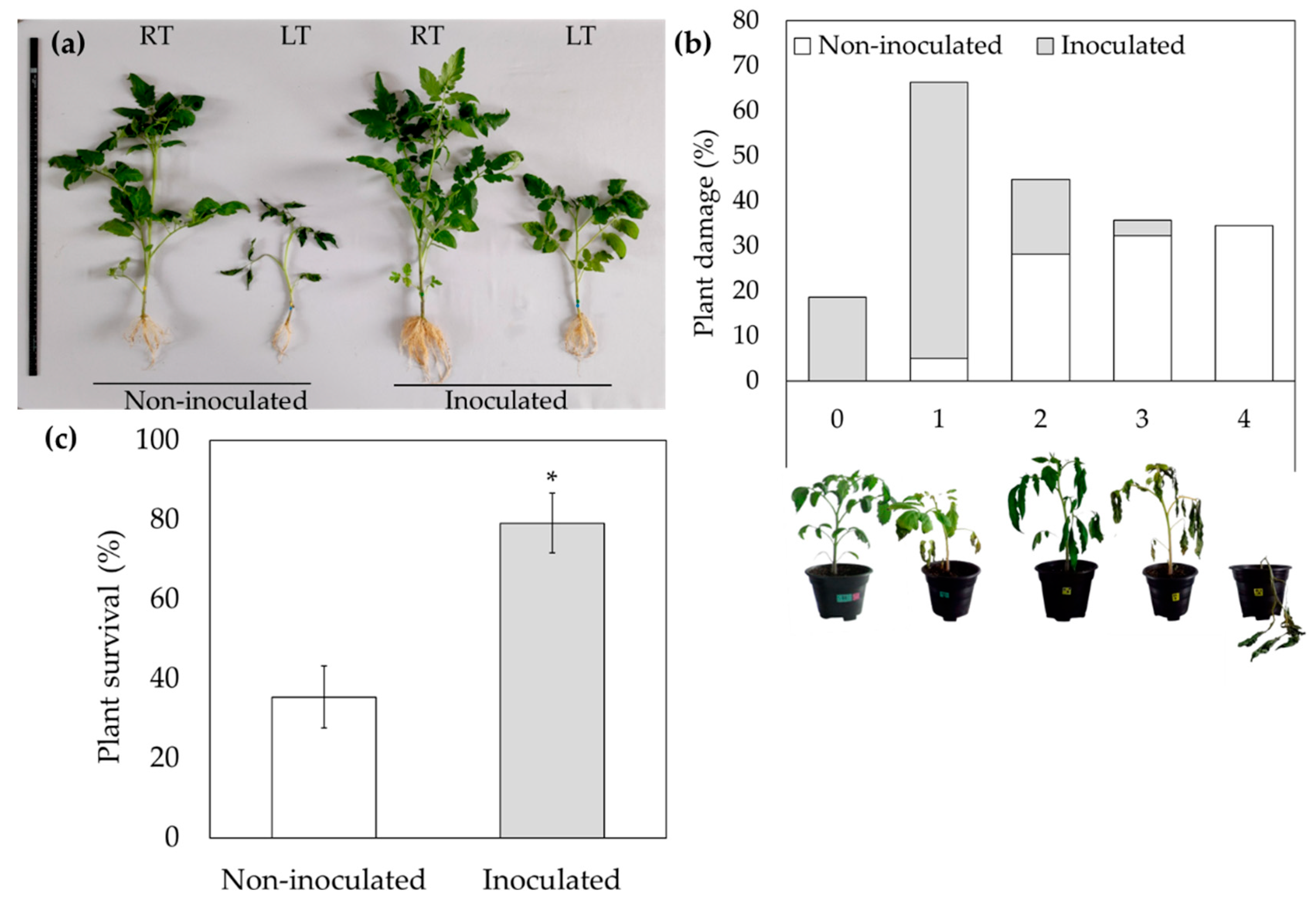

3.1. Trichoderma asperellum Enhances Low Temperature Tolerance in Tomato

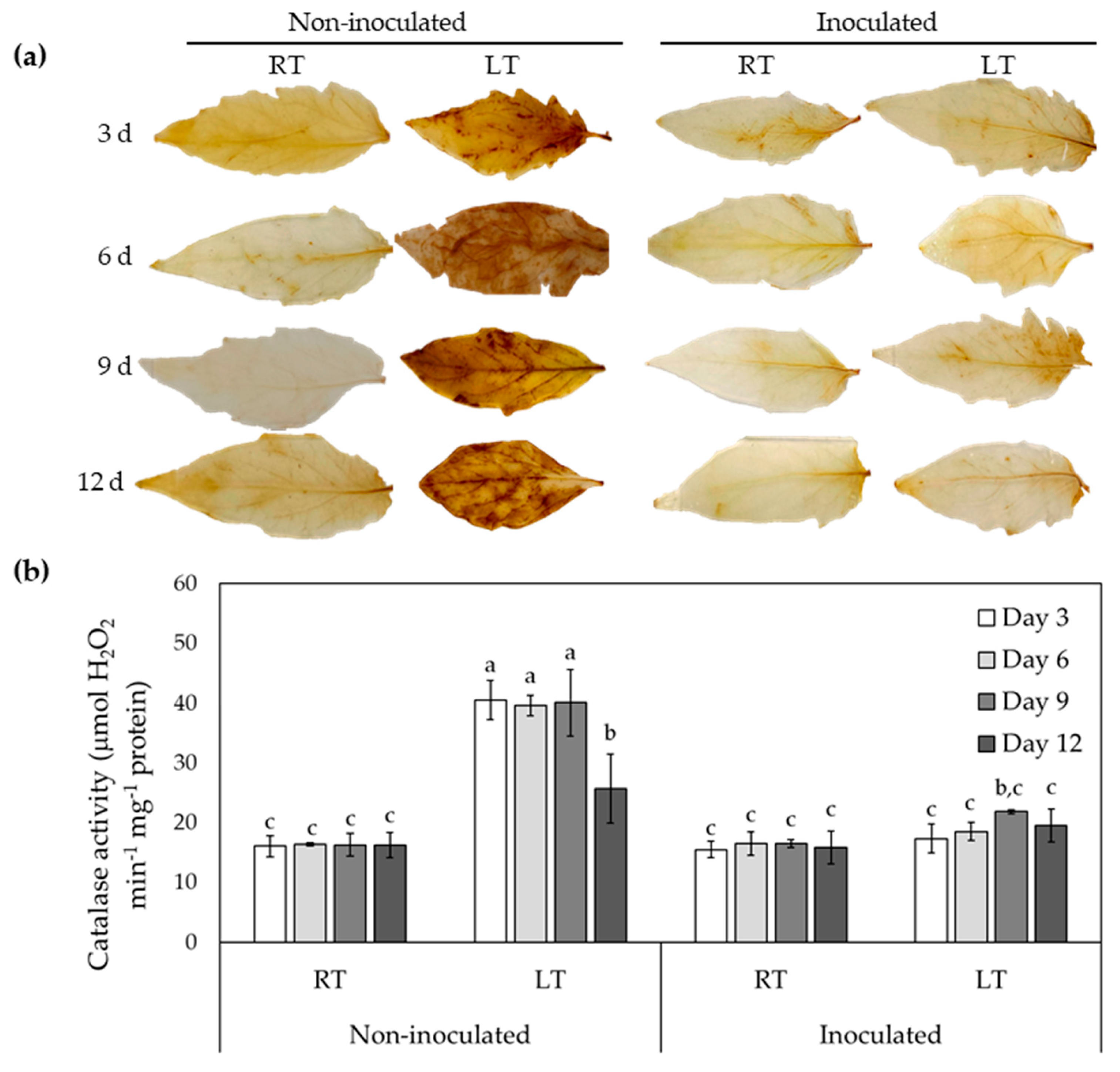

3.2. Trichoderma asperellum Decreases LT-Induced ROS Accumulation

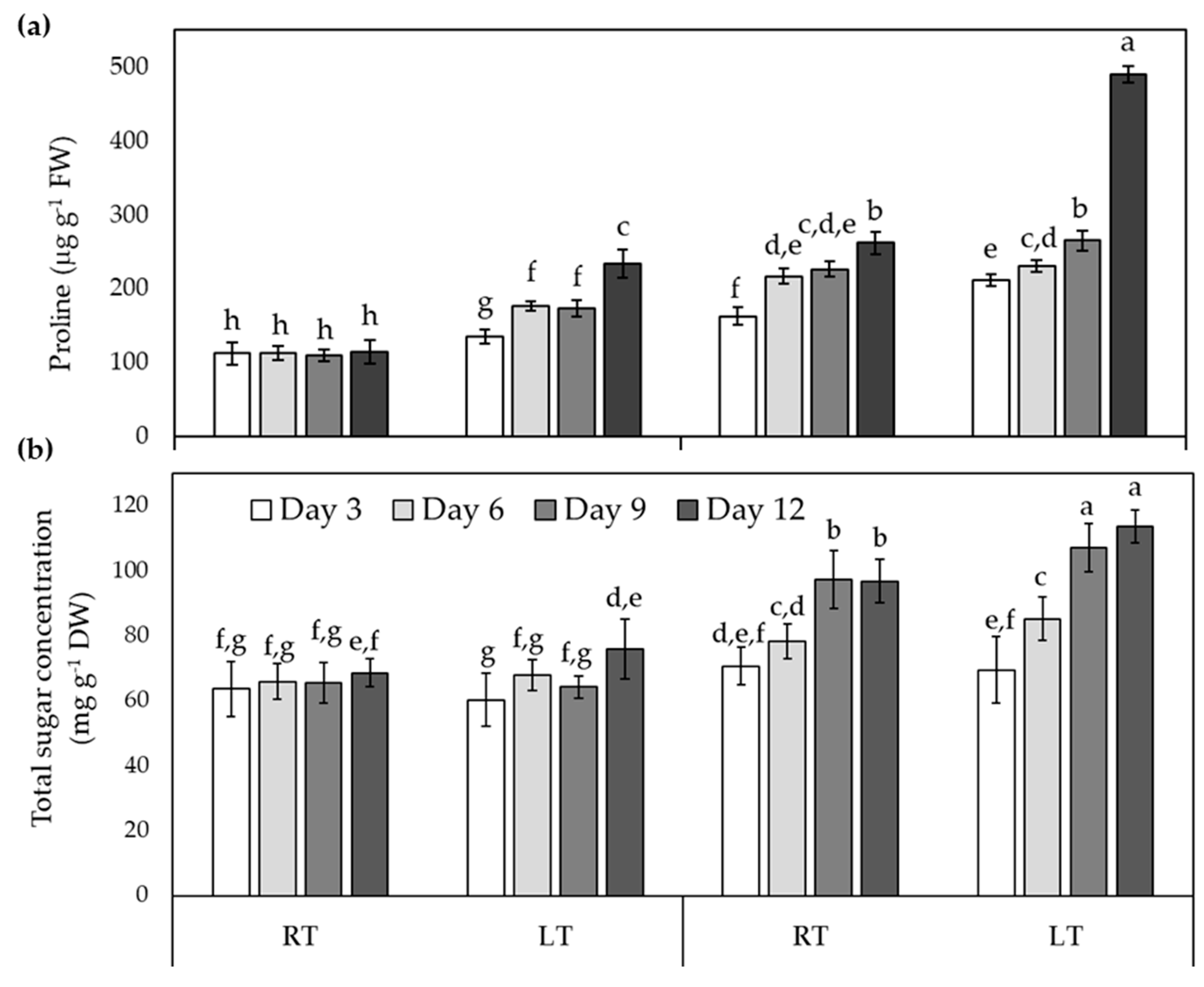

3.3. Trichoderma asperellum Promotes Overaccumulation of Proline and Total Soluble Sugars Content in Tomato Plants Under Low Temperature

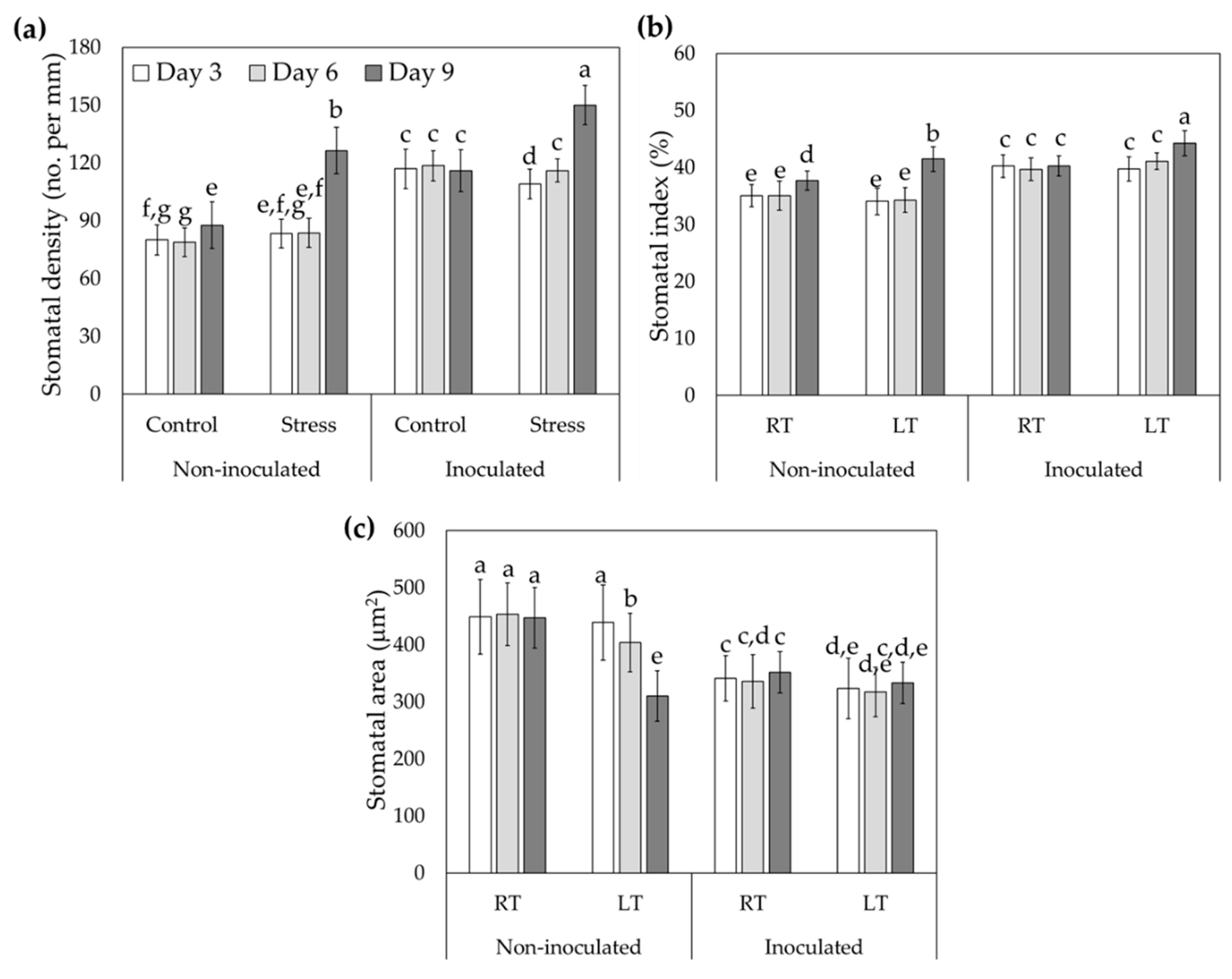

3.4. Analysis of Stomatal Traits in Tomato Inoculated with Trichoderma asperellum and Treated with Low Temperatures

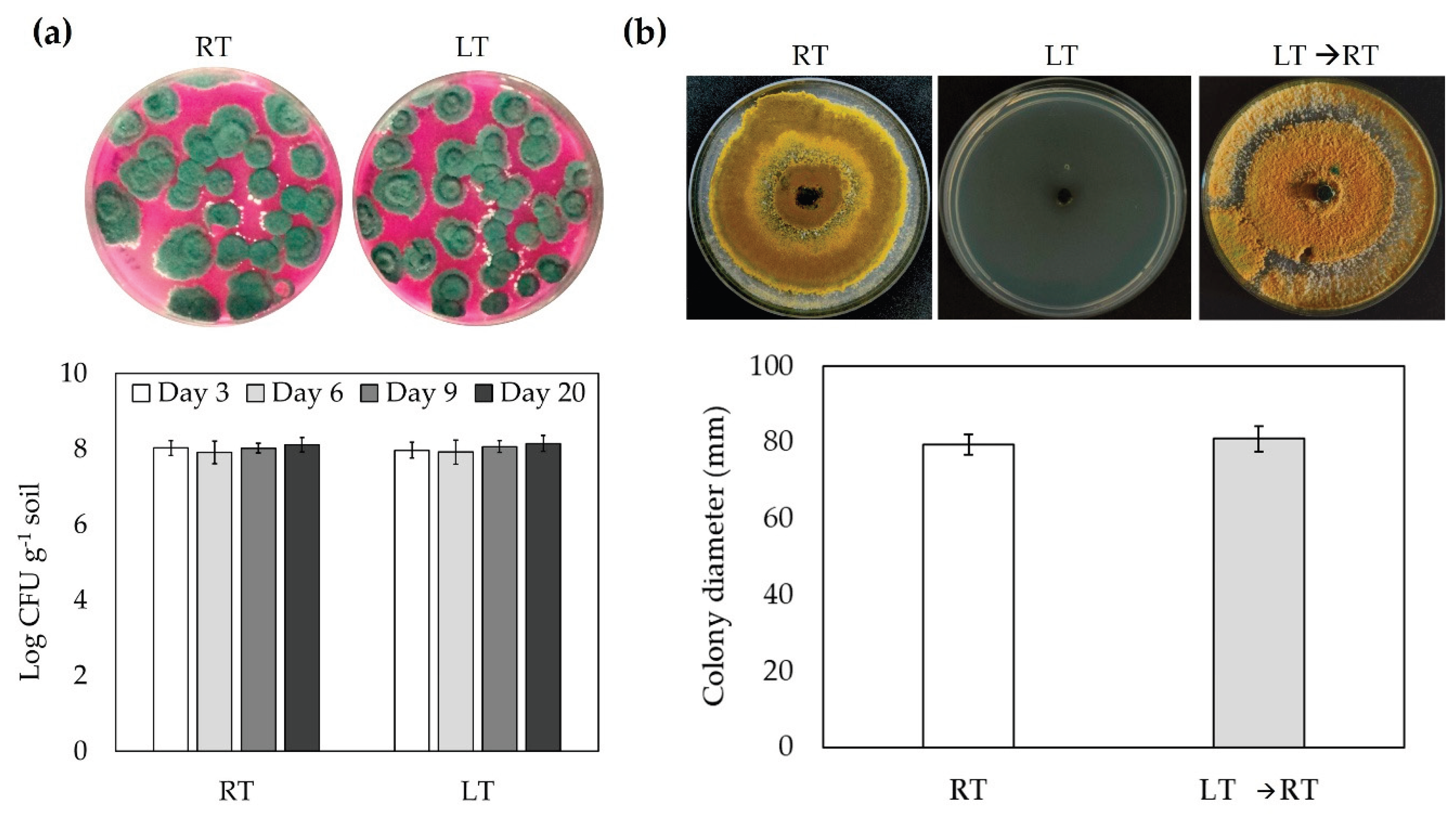

3.5. Trichoderma asperellum Survives in Low Temperatures Conditions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| APX | Ascorbate peroxidase |

| CAT | Catalase |

| CFU | Colony Forming Units |

| ET | Ethylene |

| GA | Gibberellin |

| JA | Jasmonic acid |

| LT | Low Temperatures |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| RT | Room Temperature |

| SA | Salicylic acid |

| SOD | Superoxide Dismutase |

References

- Tanaka, K.; Mudgil, Y.; Tunc-Ozdemir, M. Editorial: Abiotic stress and plant immunity – a challenge in climate change. Front Plant Sci 2023, 14, 1197435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Hwarari, D.; Korboe, H.M.; Ahmad, B.; Cao, Y.; Movahedi, A.; et al. Low temperature stress-induced perception and molecular signaling pathways in plants. Environ Exp Bot 2023, 207, 105190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devireddy, A.R.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; Tuskan, G.A.; Muchero, W.; Chen, J.-G. Role of reactive oxygen species and hormones in plant responses to temperature changes. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 8843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guy, C.L. Cold acclimation and freezing stress tolerance: role of protein metabolism. Annu Rev Plant Biol 1990, 41, 187–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, J.M. Chilling injury in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 1973, 24, 445–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, P.; Kim, K.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Mageswari, A.; Selvakumar, G.; Sa, T. Cold stress tolerance in psychrotolerant soil bacteria and their conferred chilling resistance in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum Mill.) under low temperatures. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0161592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Ploeg, D.; Heuvelink, E. Influence of sub-optimal temperature on tomato growth and yield: a review. J Hortic Sci Biotechnol 2005, 80, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.A.; Fariduddin, Q.; Yusuf, M. Lycopersicon esculentum under low temperature stress: an approach toward enhanced antioxidants and yield. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2015, 22, 14178–14188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo-Ríos, K.; Osorno-Suárez, M. delP.; Hernández-León, S.; Reyes-Santamaría, M.I.; Juárez-Díaz, J.A.; Pérez-España, V.H.; et al. Impact of Trichoderma asperellum on chilling and drought stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Horticulturae 2021, 7, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherzod, R.; Yang, E.Y.; Cho, M.C.; Chae, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Nam, C.W.; et al. Traits affecting low temperature tolerance in tomato and its application to breeding orogram. Plant Breed Biotechnol 2019, 7, 350–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, L,-J.; Zhang, B.; Shi, W.-W.; Li, H.-Y. Hydrogen peroxide in plants: a versatile molecule of the reactive oxygen species network. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2008, 50, 2–18. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL/visualize (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Meena, Y.K.; Khurana, D.S.; Kaur, N.; Singh, K. Phenolic compounds enhanced low temperature stress tolerance in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Curr J Appl Sci Technol 2017, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, T.; Khan, T.A.; Ahmad, A.; Yusuf, M.; Kappachery, S.; Fariduddin, Q.; et al. Exploring the effects of selenium and brassinosteroids on photosynthesis and protein expression patterns in tomato plants under low temperatures. Plants 2023, 12, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subramanian, P.; Mageswari, A.; Kim, K.; Lee, Y.; Sa, T. Psychrotolerant endophytic Pseudomonas sp. strains OB155 and OS261 induced chilling resistance in tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum Mill.) by activation of their antioxidant capacity. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 2015, 28, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.d.M.; Sultana, F.; Islam, S. Plant Growth-Promoting Fungi (PGPF): phytostimulation and induced systemic resistance. In Plant-Microbe Interact Agro-Ecol Perspect.; Singh, D.P., Singh, H.B., Prabha, R., Eds.; Interact. Agro-Ecol. Impacts; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Vol. 2, pp. 135–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E.; Howell, C.R.; Viterbo, A.; Chet, I.; Lorito, M. Trichoderma species - opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat Rev Microbiol 2004, 2, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gan, Y.; Xu, B. Application of plant-growth-promoting fungi Trichoderma longibrachiatum T6 enhances tolerance of wheat to salt stress through improvement of antioxidative defense system and gene expression. Front Plant Sci 2016, 7, 1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanclud, E.; Morel, J.-B. Plant hormones: a fungal point of view. Mol Plant Pathol 2016, 17, 1289–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illescas, M.; Pedrero-Méndez, A.; Pitorini-Bovolini, M.; Hermosa, R.; Monte, E. Phytohormone production profiles in Trichoderma species and their relationship to wheat plant responses to water stress. Pathogens 2021, 10, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamdan, N.-L.; Shalaby, S.; Ziv, T.; Kenerley, C.M.; Horwitz, B.A. Secretome of Trichoderma interacting with maize roots: role in induced systemic resistance. Mol Cell Proteomics 2015, 14, 1054–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, R.; Koren, R.; Kligun, E.; Gupta, R.; Leibman-Markus, M.; Mukherjee, P.K.; et al. Gliotoxin, an immunosuppressive fungal metabolite, primes plant immunity: evidence from Trichoderma virens-tomato interaction. mBio 2022, 13, e00389-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Guo, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, M.; Ruan, J.; Chen, J. Trichoderma and its role in biological control of plant fungal and nematode disease. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1160551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogaiah, S.; Abdelrahman, M.; Tran, L.-S.P.; Ito, S.-I. Different mechanisms of Trichoderma virens-mediated resistance in tomato against Fusarium wilt involve the jasmonic and salicylic acid pathways. Mol Plant Pathol 2018, 19, 870–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Huang, Y.; Ge, W.; Jia, Z.; Song, S.; Zhang, L.; et al. Involvement of jasmonic acid, ethylene and salicylic acid signaling pathways behind the systemic resistance induced by Trichoderma longibrachiatum H9 in cucumber. BMC Genomics 2019, 20, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, R.B.; Postigo, A.; Rius, S.P.; Rech, G.E.; Campos-Bermudez, V.A.; Vargas, W.A. Long-lasting primed state in maize plants: salicylic acid and steroid signaling pathways as key players in the early activation of immune responses in silks. Mol Plant-Microbe Interactions 2019, 32, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras-Cornejo, H.A.; Macías-Rodríguez, L.; Beltrán-Peña, E.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; López-Bucio, J. Trichoderma-induced plant immunity likely involves both hormonal- and camalexin-dependent mechanisms in Arabidopsis thaliana and confers resistance against necrotrophic fungi Botrytis cinerea. Plant Signal Behav 2011, 6, 1554–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kottb, M.; Gigolashvili, T.; Großkinsky, D.K.; Piechulla, B. Trichoderma volatiles effecting Arabidopsis: from inhibition to protection against phytopathogenic fungi. Front Microbiol 2015, 6, 995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-C.; Ren, J.-J.; Zhao, H.-J.; Wang, X.-L.; Wang, T.-H.; Jin, S.-D.; et al. Trichoderma harzianum improves defense against Fusarium oxysporum by regulating ROS and RNS metabolism, redox balance, and energy flow in cucumber roots. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Liu, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Yang, K. Alleviation of the effects of saline-alkaline stress on maize seedlings by regulation of active oxygen metabolism by Trichoderma asperellum. PloS One 2017, 12, e0179617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacheco-Trejo, J.; Aquino-Torres, E.; Reyes-Santamaría, M.I.; Islas-Pelcastre, M.; Pérez-Ríos, S.R.; Madariaga-Navarrete, A.; et al. Plant defensive responses triggered by Trichoderma spp. as tools to face stressful conditions. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Téllez, V.I.; Cruz-Olmedo, A.K.; Plasencia, J.; Gavilanes-Ruíz, M.; Arce-Cervantes, O.; Hernández-León, S.; et al. The protective effect of Trichoderma asperellum on tomato plants against Fusarium oxysporum and Botrytis cinerea diseases involves inhibition of reactive oxygen species production. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thordal-Christensen, H.; Zhang, Z.; Wei, Y.; Collinge, D.B. Subcellular localization of H2O2 in plants. H2O2 accumulation in papillae and hypersensitive response during the barley—powdery mildew interaction. Plant J 1997, 11, 1187–1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aebi, H. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol 1984, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.A.; McNeilly, T.; Collins, J.C. Accumulation of amino acids, proline, and carbohydrates in response to aluminum and manganese stress in maize. J Plant Nutr 2000, 23, 1303–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceulemans, R.; Van Praet, L.; Jiang, X.N. Effects of CO2 enrichment, leaf position and clone on stomatal index and epidermal cell density in poplar (Populus). New Phytol 1995, 131, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, I.; Kürschner, W. Stomatal density and index: The practice. In Foss. Plants Spores Mod. Tech.; 1999; pp. 257–260. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Medina, A.; Roldán, A.; Pascual, J.A. Interaction between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Trichoderma harzianum under conventional and low input fertilization field condition in melon crops: growth response and Fusarium wilt biocontrol. Appl Soil Ecol 2011, 47, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, A.L.A.; Negreiros, A.M.P.; Melo, N.J. de A.; Santos, F.J.Q.; Soares Silva, C.S.A.; Pinto, P.S.L.; et al. Adaptability and sensitivity of Trichoderma spp. isolates to environmental factors and fungicides. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wani, A.S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of proline under changing environments. Plant Signal Behav 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klessig, D.F.; Tian, M.; Choi, H.W. Multiple targets of salicylic acid and its derivatives in plants and animals. Front Immunol 2016, 7, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durner, J.; Klessig, D.F. Salicylic acid is a modulator of tobacco and mammalian catalases. J Biol Chem 1996, 271, 28492–28501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritonga, F.N.; Chen, S. Physiological and molecular mechanisms involved in cold stress tolerance in plants. Plants 2020, 9, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnoff, N.; Cumbes, Q.J. Hydroxyl radical scavenging activity of compatible solutes. Phytochemistry 1989, 28, 1057–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Signorelli, S.; Coitiño, E.L.; Borsani, O.; Monza, J. Molecular mechanisms for the reaction between •OH radicals and proline: insights on the role as reactive oxygen species scavenger in plant stress. J Phys Chem B 2014, 118, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hare, P.D.; Cress, W.A. Metabolic implications of stress-induced proline accumulation in plants. Plant Growth Regul 1997, 21, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forlani, G.; Trovato, M.; Funck, D.; Signorelli, S. Regulation of proline accumulation and its molecular and physiological functions in stress defence. In Osmoprotectant-Mediat. Abiotic Stress Toler. Plants Recent Adv. Future Perspect; Hossain, M.A., Kumar, V., Burritt, D.J., Fujita, M., Mäkelä, P.S.A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 73–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzetti, M.; Funck, D.; Trovato, M. Proline and ROS: a unified mechanism in plant development and stress response? Plants 2025, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Chen, F.; Ge, H.; Tian, F.; et al. Trichoderma harzianum mitigates salt stress in cucumber via multiple responses. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2019, 170, 436–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanpour, A.; Salimi, A.; Ghanbary, M.A.T.; Pirdashti, H.; Dehestani, A. The effect of Trichoderma harzianum in mitigating low temperature stress in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) plants. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 230, 134–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tan, P.; Chang, L.; Yue, Z.; Zeng, C.; Lo, M.; Liu, Z.; Dong, X.; Yan, M. Exogenous proline mitigates toxic effects of cadmium via the decrease of cadmium accumulation and reestablishment of redox homeostasis in Brassica juncea. BMC Plant Biology 2022, 22, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anchordoguy, T.J.; Rudolph, A.S.; Carpenter, J.F.; Crowe, J.H. Modes of interaction of cryoprotectants with membrane phospholipids during freezing. Cryobiology 1987, 24, 324–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakr, S.; Wang, M.; Dédaldéchamp, F.; Perez-Garcia, M.-D.; Ogé, L.; Hamama, L.; et al. The sugar-signaling Hub: overview of regulators and interaction with the hormonal and metabolic network. Int J Mol Sci 2018, 19, 2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuanyuan, M.; Yali, Z.; Jiang, L.; Hongbo, S. Roles of plant soluble sugars and their responses to plant cold stress. Afr J Biotechnol 2009, 8, 2004–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Latif, A. Activity of sucrose synthase and acid invertase in wheat seedlings during a cold-shock using micro plate reader assays. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2008, 2, 53–56. [Google Scholar]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Zhou, M.; Shabala, S. How does stomatal density and residual transpiration contribute to osmotic stress tolerance? Plants 2023, 12, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhou, G. Responses of leaf stomatal density to water status and its relationship with photosynthesis in a grass. J Exp Bot 2008, 59, 3317–3325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Z.Y.; Han, J.M.; Yi, X.P.; Zhang, W.F.; Zhang, Y.L. Coordinated variation between veins and stomata in cotton and its relationship with water-use efficiency under drought stress. Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 1326–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, P.J.; Beerling, D.J. Maximum leaf conductance driven by CO2 effects on stomatal size and density over geologic time. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2009, 106, 10343–10347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Baird, A.S.; He, N. Optimal community assembly related to leaf economic- hydraulic-anatomical traits. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Sack, L.; Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, K.; Zhang, Q.; et al. Relationships of stomatal morphology to the environment across plant communities. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 6629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hetherington, A.M.; Woodward, F.I. The role of stomata in sensing and driving environmental change. Nature 2003, 424, 901–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, P.J.; Drake, P.L.; Beerling, D.J. Plasticity in maximum stomatal conductance constrained by negative correlation between stomatal size and density: an analysis using Eucalyptus globulus. Plant Cell Environ 2009, 32, 1737–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarrie, S.A.; Jones, H.G. Effects of abscisic acid and water stress on development and morphology of wheat. J Exp Bot 1977, 28, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, P.L.; Froend, R.H.; Franks, P.J. Smaller, faster stomata: scaling of stomatal size, rate of response, and stomatal conductance. J Exp Bot 2013, 64, 495–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, J.A. Speedy small stomata? J Exp Bot 2014, 65, 1415–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.-B.; Guan, Z.-J.; Sun, M.; Zhang, J.-J.; Cao, K.-F.; Hu, H. Evolutionary association of stomatal traits with leaf vein density in Paphiopedilum, Orchidaceae. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrickson, M.; Banan, D.; Tournay, R.; Bakker, J.D.; Doty, S.L.; Kim, S.-H. Salicaceae endophyte inoculation alters stomatal patterning and improves the intrinsic water-use efficiency of Populus trichocarpa after a water deficit. J Exp Bot 2025, 76, 3499–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Hu, H.; Huang, G.; Huang, F.; Li, Y.; Palta, J. Soil inoculation with Burkholderia sp. LD-11 has positive effect on water-use efficiency in inbred lines of maize. Plant Soil 2015, 390, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukwudi, U.P.; Babalola, O.O.; Glick, B.R.; Santoyo, G.; Rigobelo, E.C. Field application of beneficial microbes to ameliorate drought stress in maize. Plant Soil 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y.; Sugano, S.S.; Shimada, T.; Hara-Nishimura, I. Enhancement of leaf photosynthetic capacity through increased stomatal density in Arabidopsis. New Phytol 2013, 198, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franks, P.J.; Farquhar, G.D. Effect of exogenous abscisic acid on stomatal development, stomatal mechanics, and leaf gas exchange in Tradescantia virginiana. Plant Physiol 2001, 125, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, J.K.; Hofmockel, K.S. Soil microbiomes and climate change. Nat Rev Microbiol 2020, 18, 35–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnecker, J.; Spiegel, F.; Li, Y.; Richter, A.; Sandén, T.; Spiegel, H.; et al. Microbial responses to soil cooling might explain increases in microbial biomass in winter. Biogeochemistry 2023, 164, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).