Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Sweet corn (Zea mays var. saccharata) is a widely spread crop that is highly valued for its sweet taste and high nutrient content. Over the past decade, there has been an exponential increase in the area devoted to sweet corn for grain production, attributed to both its nutritional qualities and economic value. In this context, we aimed to evaluate the impact of three genotypes (Deliciosul de Bacau, Royalty F1, and Hardy F1) and two fertilization types (chemical and organic) plus an unfertilized control, on yield, biometrical, biochemical, and quality indicators at an experimental station during 2022–2023. The results revealed significant influences of cultivar, fertilization method, and the interaction between these two experimental factors on most of the analysed indicators. Regardless of the fertilization type, the genotype Hardy F1 showed higher levels of photosynthetic activity, polyphenols and sucrose, leading to greater yield than that of Deliciosul de Bacau. The latter genotype and Royalty F1 displayed the highest chlorophyll A, chlorophyll B, and lycopene contents in the grain. The results of the present research emphasize the importance of adopting and monitoring sustainable agricultural practices to enhance both the production and quality of sweet corn, particularly referring to the nutritional value, and address the growing demand for organically cultivated products within the current context of climate change.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

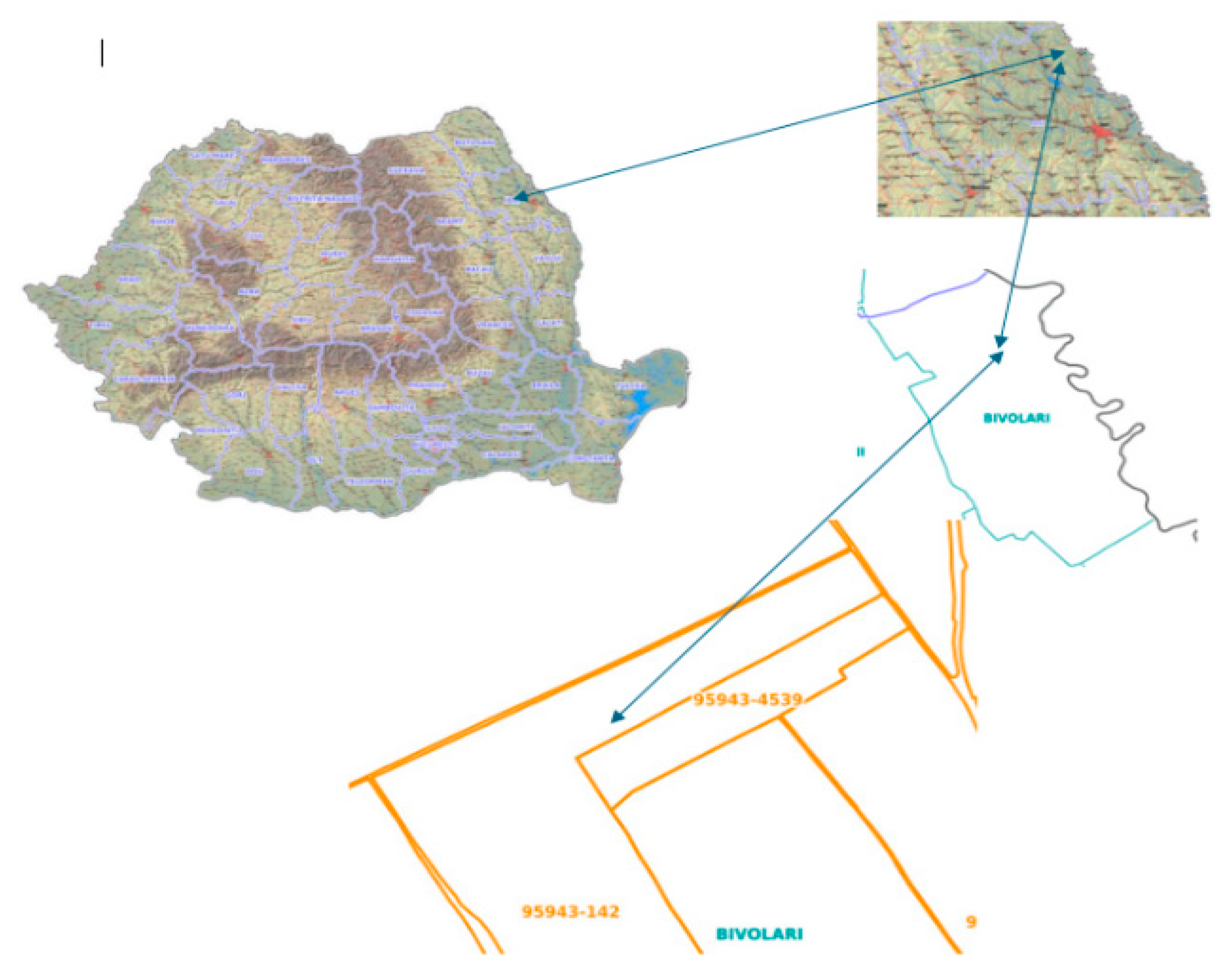

2.1. Location and Experimental Conditions

2.2. Biological Material and Experimental Design

2.3. Harvesting and Sample Preparation

2.4. Analytical Methods

2.5. Chlorophyll and Carotenoid Pigments

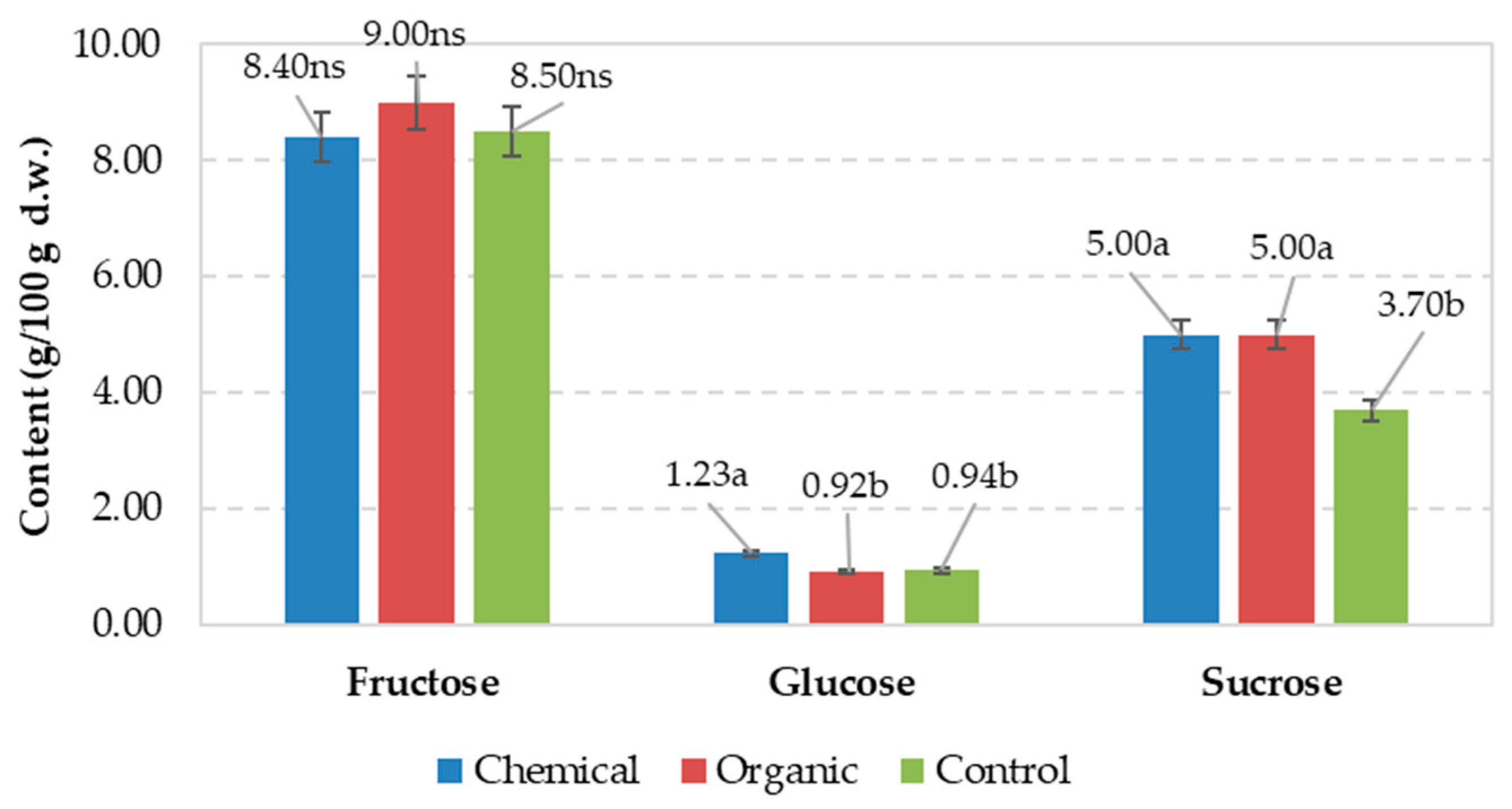

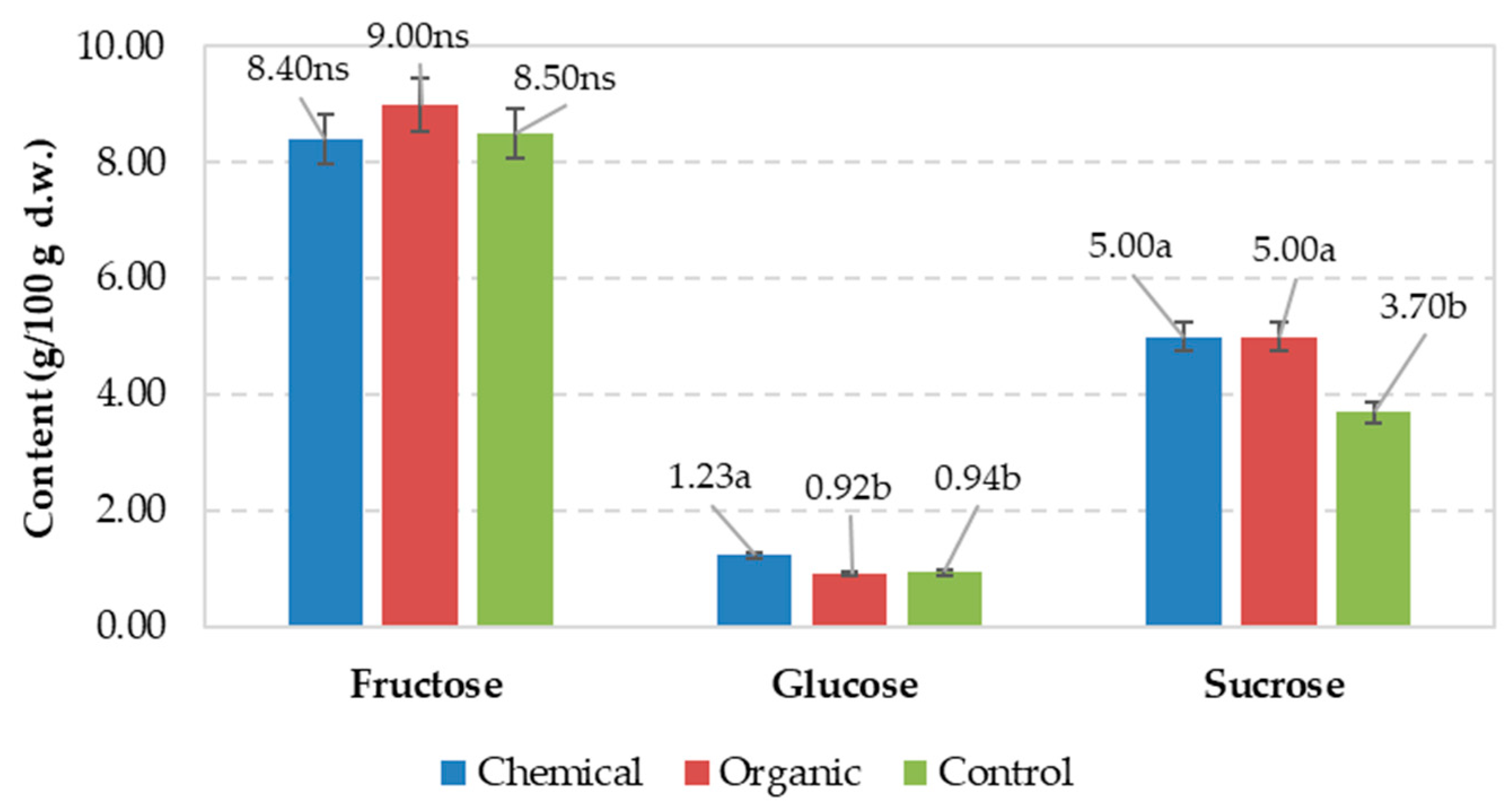

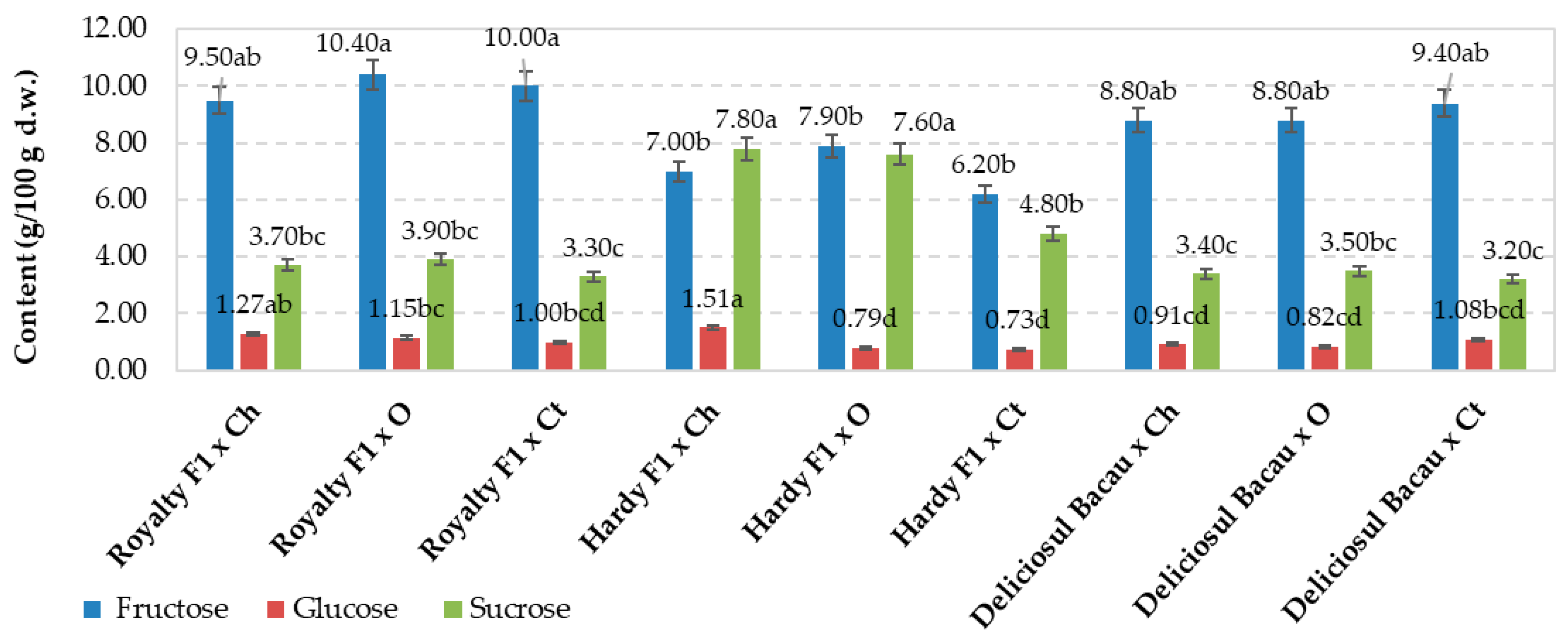

2.6. Sugar Analysis

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Influence of Cultivar and Fertilization Regime on Yield and Quality Characteristics

3.2. Interactions Between Variety and Fertilization Regime on Yield, Biometrical, Biochemical and Quality of Sweet Corn

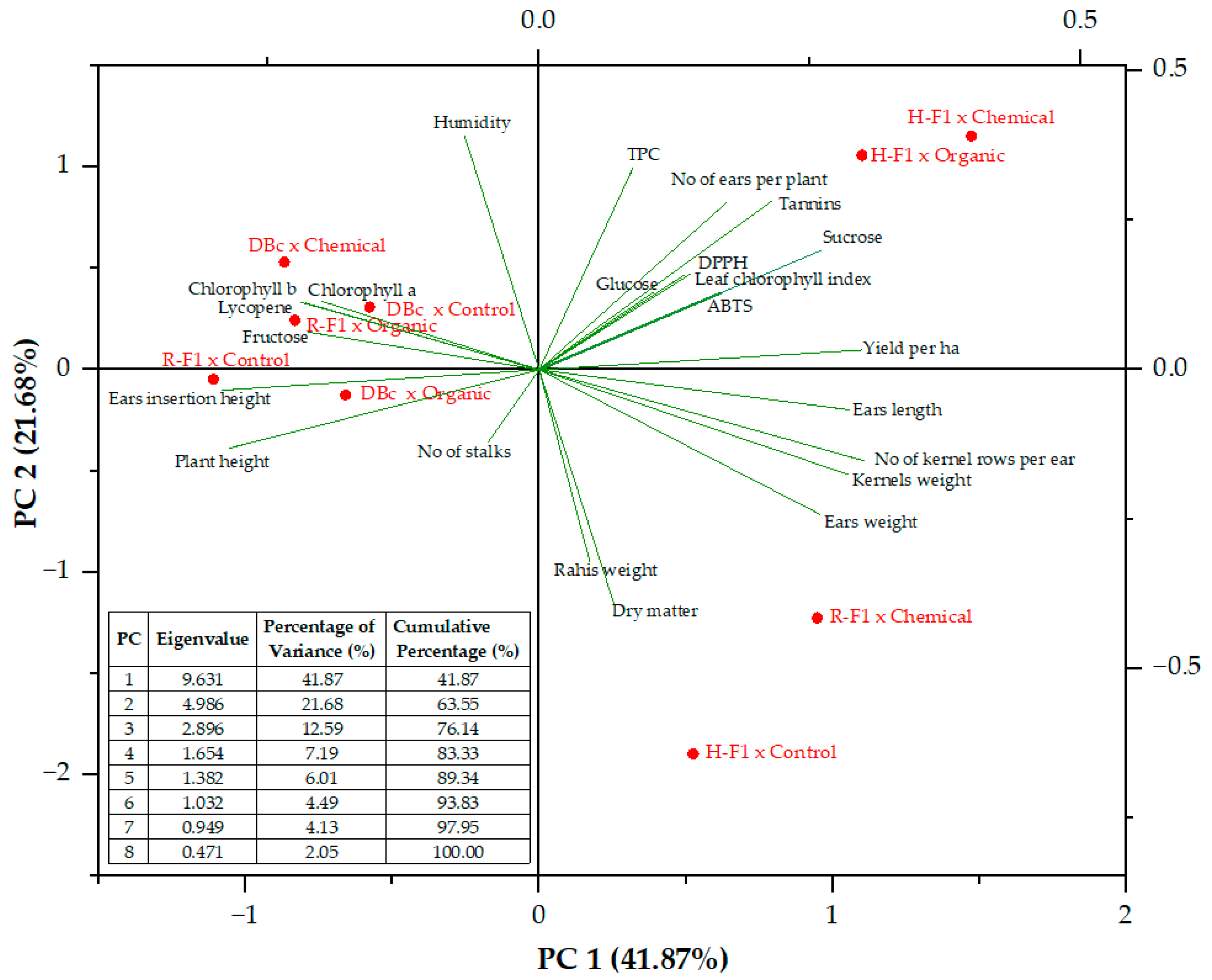

3.3. Dimensionality Reduction and Exploratory Causal Statistical Analysis of Data

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castillo-Gironés, S.; Masztalerz, K.; Lech, K.; Issa-Issa, H.; Figiel, A.; Carbonell-Barrachina, A.A. Impact of osmotic dehydration and different drying methods on the texture and sensory characteristic of sweet corn kernels. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2021, 45, e15383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranowska, A. The nutritional value and health benefits of sweet corn kernels (Zea mays ssp. saccharata). Health Prob Civil. 2023, 17, 408–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grain Production Worldwide by Type 2024/25. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/263977/world-grain-production-by-type/?srsltid=AfmBOooal7aBJTuXX495-p2vDyNnNqdXcAYLkSh0DNRNnH1KvpGipVdq (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Tanumihardjo, S.A.; McCulley, L.; Roh, R.; Lopez-Ridaura, S.; Palacios-Rojas, N.; Gunaratna, N.S. Maize Agro-Food systems to ensure food and nutrition security in reference to the sustainable development goals. Global Food Security 2020, 25, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erenstein, O.; Jaleta, M.; Sonder, K.; Mottaleb, K.; Prasanna, B.M. Global Maize production, consumption and trade: Trends and R&D implications. Food Sec. 2022, 14, 1295–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padhan, S.R.; Jat, S.L.; Mishra, P.; Darjee, S.; Saini, S.; Padhan, S.R.; Radheshyam; Ranjan, S.; Padhan, S.R.; Jat, S.L.; et al. Corn for Biofuel: Status, Prospects and Implications. In New Prospects of Maize; IntechOpen, 2023 ISBN 978-1-83768-632-2.

- Soare, R.; Dinu, M. Effect of biofertilizers on quality of sweet corn. Scientific Papers. Series B, Horticulture 2023, LXVII, 696–702. [Google Scholar]

- Sidahmed, H.; Vad, A.; Nagy, J. Advances in sweet corn (Zea mays L. saccharata) research from 2010 to 2025: Genetics, agronomy, and sustainable production. Agronomy 2025, 15, 1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budak, F.; Aydemir, S.K. Grain yield and nutritional values of sweet corn (Zea mays var. saccharata) in produced with good agricultural practices. Nutri Food Sci Int J. 2018, 7, 555710. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, U.; Tyagi, S.; Gadag, R.; Elayaraja, K.; Pathak, H. Analysis of water soluble and insoluble polysaccharides in kernels of different corns (Zea mays L.). Current Science 2016, 111, 1522–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becerra-Sanchez, F.; Taylor, G. Reducing post-harvest losses and improving quality in sweet corn (Zea mays L.): Challenges and solutions for less food waste and improved food security. Food and Energy Security 2021, 10, e277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canatoy, R.C.; Daquiado, N.P. Fertilization influence on biomass yield and nutrient uptake of sweet corn in potentially hardsetting soil under no tillage. Bull Natl Res Cent 2021, 45, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alahmari, L.A. Dietary fiber influence on overall health, with an emphasis on cvd, diabetes, obesity, colon cancer, and inflammation. Front Nutr 2024, 11, 1510564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilherme, R.; Reboredo, F.; Guerra, M.; Ressurreição, S.; Alvarenga, N. Elemental composition and some nutritional parameters of sweet pepper from organic and conventional agriculture. Plants 2020, 9, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, F.J.; Pradas, I.; Ruiz-Moreno, M.J.; Arroyo, F.T.; Perez-Romero, L.F.; Montenegro, J.C.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Effect of organic and conventional management on bio-functional quality of thirteen plum cultivars (Prunus salicina Lindl.). PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.H.; Beatty, E.R.; Kingman, S.M.; Bingham, S.A.; Englyst, H.N. Digestion and physiological properties of resistant starch in the human large bowel. Br J Nutr 1996, 75, 733–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Jhariya, A.N. Nutritional, medicinal and economical importance of corn: A mini review. Res. J. Pharmaceutical Sci 2013, 2, 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- Dragomir, V.; Brumă, I.S.; Butu, A.; Petcu, V.; Tanasă, L.; Horhocea, D. An overview of global maize market compared to romanian production. RAR 2022, 39, 535–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertek, A.; Kara, B. Yield and quality of sweet corn under deficit irrigation. Agricultural Water Management 2013, 129, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrowicka, M.; Mrowicki, J.; Kucharska, E.; Majsterek, I. Lutein and zeaxanthin and their roles in age-related macular degeneration—neurodegenerative disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lillioja, S.; Neal, A.L.; Tapsell, L.; Jacobs, D., Jr. Whole grains, type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and hypertension: Links to the aleurone preferred over indigestible fiber. BioFactors 2013, 39, 242–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, P.-F.; Chang, Y.-T.; Lai, J.-M.; Chou, K.-L.; Tai, S.-F.; Tseng, K.-C.; Chow, C.-N.; Jeng, S.-L.; Huang, H.-J.; Chang, W.-C. Long-term effects of fertilizers with regional climate variability on yield trends of sweet corn. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla, P.; Anibas, C.M.; Tracy, W.F. Sweet corn research around the world 2015–2020. Agronomy 2021, 11, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutuliac, R.; Precupeanu, C.; Vasilachi, I.C.; Cojocaru, A.; Rosca, M.; Stoleru, V. Response of sweet corn varieties to plant density and tiller removal: Preliminary studies. JALSE 2024, 57, 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apahidean, A.I.; Hoza, G.; Dinu, M.; Soare, R.; Mitre, V.; Sima, R.; Buta, E.; Rózsa, S. Qualitative changes occurred at several sweet corn (Zea mays convar. saccharata var. rugosa) cultivars in different agrotechnical conditions. Acta Hortic. 2024, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, T. Phytosterols in cereal by-products. J Americ Oil Chem Soc 2005, 82, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, Z.; Khalil, S.; Iqbal, A.; Islam, B.; Shah, W.; Ahmad, A.; Arif, M.; Sajjad, M.; Shah, F. Growth attributes of sweet corn under different planting regimes. Fresenius Environmental Bulletin 2018, 27, 6945–6951. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa Pereira, R.; Angelis-Pereira, M. Effect of organic versus conventional agricultural systems on bioactive compounds of fruits and vegetables: An integrative review. Cadernos de Ciência & Tecnologia 2022, 39, 27072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, A.; Gangahagedara, R.; Gamage, J.; Jayasinghe, N.; Kodikara, N.; Suraweera, P.; Merah, O. Role of organic farming for achieving sustainability in agriculture. Farming System 2023, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.H.; Jaafar, H.Z.E.; Karimi, E.; Ghasemzadeh, A. Impact of organic and inorganic fertilizers application on the phytochemical and antioxidant activity of Kacip Fatimah (Labisia pumila Benth). Molecules 2013, 18, 10973–10988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapałowska, A.; Jarecki, W. The impact of using different types of compost on the growth and yield of corn. Sustainability 2024, 16, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghdadi, A.; Halim, R.A.; Ghasemzadeh, A.; Ramlan, M.F.; Sakimin, S.Z. Impact of organic and inorganic fertilizers on the yield and quality of silage corn intercropped with soybean. PeerJ 2018, 6, e5280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoleru, V.; Mangalagiu, I.; Amăriucăi-Mantu, D.; Teliban, G.-C.; Cojocaru, A.; Rusu, O.-R.; Burducea, M.; Mihalache, G.; Rosca, M.; Caruso, G.; et al. Enhancing the nutritional value of sweet pepper through sustainable fertilization management. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusu, O.-R.; Mangalagiu, I.; Amăriucăi-Mantu, D.; Teliban, G.-C.; Cojocaru, A.; Burducea, M.; Mihalache, G.; Roșca, M.; Caruso, G.; Sekara, A.; et al. Interaction effects of cultivars and nutrition on quality and yield of tomato. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Nadeem, M.; Ashiq, W.; Zaeem, M.; Gilani, S.S.M.; Rajabi-Khamseh, S.; Pham, T.H.; Kavanagh, V.; Thomas, R.; Cheema, M. The effects of organic and inorganic phosphorus amendments on the biochemical attributes and active microbial population of agriculture podzols following silage corn cultivation in boreal climate. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 17297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Sharma, P.; Thakur, N. Sustainable farming practices and soil health: A pathway to achieving SDGs and future prospects. Discov Sustain 2024, 5, 250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Redondo, J.M.; Montenegro, J.C.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Using nitrogen stable isotopes to authenticate organically and conventionally grown vegetables: A new tracking framework. Agronomy 2022, 13, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Iglesias, L.; Puig, C.G.; Revilla, P.; Reigosa, M.J.; Pedrol, N. Faba bean as green manure for field weed control in maize. Weed Research 2018, 58, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Rozo, J.; Galvis-López, J.; Manjarres, E.; Merchán-Castellanos, N. Biosolids as fertilizer in the tomato crop. Revista de la Facultad de Agronomía de la Universidad del Zulia 2022, 39, e223931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marta, A.E.; Slabu, C.; Mihaela Covasa, M.; Motrescu, I.; Jitareanu, C.D. Comparative analysis of the influence of different biostimulators on the germination and sprouting behaviour of four wheat varieties. JALSE 2023, 55/2022, 377–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chețan, F.; Rusu, T.; Chețan, C.; Șimon, A.; Vălean, A.-M.; Ceclan, A.O.; Bărdaș, M.; Tărău, A. Application of unconventional tillage systems to maize cultivation and measures for rational use of agricultural lands. Land 2023, 12, 2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzanka, M.; Smoleń, S.; Skoczylas, Ł.; Grzanka, D. Synthesis of organic iodine compounds in sweetcorn under the influence of exogenous foliar application of iodine and vanadium. Molecules 2022, 27, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordóñez-Díaz, J.L.; Hervalejo, A.; Pereira-Caro, G.; Muñoz-Redondo, J.M.; Romero-Rodríguez, E.; Arenas-Arenas, F.J.; Moreno-Rojas, J.M. Effect of Rootstock and harvesting period on the bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity of two orange cultivars (‘Salustiana’ and ‘Sanguinelli’) widely used in juice industry. Processes 2020, 8, 1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ortega, A.; Pereira-Caro, G.; Luis Ordóñez, J.; Manuel Muñoz-Redondo, J.; Moreno-Rojas, R.; Pérez-Aparicio, J.; Manuel Moreno-Rojas, J. Changes in the antioxidant activity and metabolite profile of three onion varieties during the elaboration of ‘black onion. ’ Food Chemistry 2020, 311, 125958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slinkard, K.; Singleton, V.L. Total phenol analysis: Automation and comparison with manual methods. Am J Enol Vitic. 1977, 28, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, M.; Yamashita, I. Simple method for simultaneous determination of chlorophyll and carotenoids in tomato fruit. J. Japan. Soc. Food Sci. Technol. 1992, 39, 925–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojocaru, A.; Carbune, R.-V.; Teliban, G.-C.; Stan, T.; Mihalache, G.; Rosca, M.; Rusu, O.-R.; Butnariu, M.; Stoleru, V. Physiological, morphological and chemical changes in pea seeds under different storage conditions. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 28191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Ferdausi, A.; Sweety, A.Y.; Das, A.; Ferdoush, A.; Haque, M.A. Morphological characterization and genetic diversity analyses of plant traits contributed to grain yield in maize (Zea mays L.). J biosci agric res 2020, 25, 2047–2059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahato, A.; Shahi, J.P.; Singh, P.K.; Kumar, M. Genetic Diversity of sweet corn inbreds using agro-morphological traits and microsatellite markers. 3 Biotech 2018, 8, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subaedah, S.; Edy, E.; Mariana, K. Growth, yield, and sugar content of different varieties of sweet corn and harvest time. International Journal of Agronomy 2021, 2021, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niji, M.S.; Ravekisavan, R.; Ganesan, K.N.; Thiyagarajan, C. Genetic variability, heritability and character association studies in sweet corn (Zea mays L. saccharata). Electronic Journal of Plant Breeding 2018, 9, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskari, M.; Menexes, G.C.; Kalfas, I.; Gatzolis, I.; Dordas, C. Effects of fertilization on morphological and physiological characteristics and environmental cost of maize (Zea mays L.). Sustainability 2022, 14, 8866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, H.O.; Al-Obaidy, K.S. Response of sweet corn (Zea mays saccharata L.) to different levels of organic and inorganic fertilizer. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1252, 012065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, M.; Dong, C.; Bian, W.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Effects of different fertilization practices on maize yield, soil nutrients, soil moisture, and water use efficiency in Northern China based on a meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, I.; Yang, L.; Ahmad, S.; Farooq, S.; Al-Ghamdi, A.A.; Khan, A.; Zeeshan, M.; Elshikh, M.S.; Abbasi, A.M.; Zhou, X.-B. Nitrogen fertilizer modulates plant growth, chlorophyll pigments and enzymatic activities under different irrigation regimes. Agronomy 2022, 12, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Siddique, A.B.; Shabala, S.; Zhou, M.; Zhao, C. Phosphorus plays key roles in regulating plants’ physiological responses to abiotic stresses. Plants (Basel) 2023, 12, 2861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Han, Y.; Xu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Shen, J.; Cheng, L. Phosphorus partitioning contribute to phosphorus use efficiency during grain filling in Zea mays. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Păcurar, L.; Apahidean, M.; Has, V.; Apahidean, A. Morpho-productive and chemical composition of local and foreign sweet corn hybrids grown in the conditions of Transylvania Plateau. Bulletin of University of Agricultural Sciences and Veterinary Medicine Cluj-Napoca. Horticulture 2017, 74, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, D.; He, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, C. Comparison of carotenoid composition in immature and mature grains of corn (Zea mays L.) varieties. International Journal of Food Properties 2016, 19, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, U.M.; Sevindik, M.; Zarrabi, A.; Nami, M.; Ozdemir, B.; Kaplan, D.N.; Selamoglu, Z.; Hasan, M.; Kumar, M.; Alshehri, M.M.; et al. Lycopene: Food sources, biological activities, and human health benefits. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021, 2021, 2713511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlović, R.; Mladenović, J.; Pavlović, N.; Zdravković, M.; Josic, D.; Zdravković, J. Antioxidant Nutritional quality and the effect of thermal treatments on selected processing tomato lines. Acta scientiarum Polonorum. Hortorum cultus = Ogrodnictwo 2017, 16, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledenčan, T.; Horvat, D.; Špoljarić Marković, S.; Svečnjak, Z.; Jambrović, A.; Šimić, D. Effect of Harvest date on kernel quality and antioxidant activity in su1 sweet corn genotypes. Agronomy 2022, 12, 1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, S.; Mao, Y.; Gu, Y.; Huang, B.; He, Z.; Zeng, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Q.; Tang, M.; Chen, J. Carotenoid and phenolic compositions and antioxidant activity of 23 cultivars of corn grain and corn husk extract. Foods 2024, 13, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Huang, L.; Deng, Y.; Chi, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, M. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of eight representative sweet corn varieties grown in South China. International Journal of Food Properties 2017, 20, 3043–3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Murmu, K.; Mitra, B.; Bandopadhyay, P.; Kundu, R.; Roy, M.; Alfarraj, S.; Ansari, M.J.; Brestic, M.; Hossain, A. Various organic nutrient sources in combinations with inorganic fertilizers influence the yield and quality of sweet corn (Zea Mays L. Saccharata) in new alluvial soils of West Bengal, India. Phyton 2024, 93, 763–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Liu, H.; Yu, Y.; Li, G.; Qi, X.; Li, Y.; Li, T.; Guo, X.; Liu, R.H. Accumulation of phenolics, antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of sweet corn (Zea mays L.) during kernel maturation. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2021, 56, 2462–2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, H.-H.; Yi, G.; Go, Y.S.; Ha, J.Y.; Choi, Y.; Son, J.-H.; Shin, S.; Jung, T.-W.; Lee, S. Measuring antioxidant activity in yellow corn (Zea mays L.) inbreds from three different geographic regions. Applied Biological Chemistry 2021, 64, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragičević, V.; Brankov, M.; Stoiljković, M.; Tolimir, M.; Kanatas, P.; Travlos, I.; Simić, M. Kernel color and fertilization as factors of enhanced maize quality. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feregrino-Pérez, A.A.; Mercado-Luna, A.; Murillo-Cárdenas, C.A.; González-Santos, R.; Chávez-Servín, J.L.; Vargas-Madriz, A.F.; Luna-Sánchez, E. Polyphenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity in native maize of the Sierra Gorda of Querétaro. Agronomy 2024, 14, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elemosho, A.O.; Irondi, E.A.; Alamu, E.O.; Ajani, E.O.; Maziya-Dixon, B.; Menkir, A. Characterization of striga-resistant yellow-orange maize hybrids for bioactive, carbohydrate, and pasting properties. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2020, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragheb, E.E. Sweet Corn as affected by foliar application with amino – and humic acids under different fertilizer sources. Egypt. J. Hort. 2016, 43, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leandro da Cruz, L.; Gonçalves, G.M.B.; de Lima Glória, L.; de Faria Pereira, S.M.; de Almeida Carlos, C.; Vivas, M.; Pereira, M.G.; Barros de Oliveira, D. Phenolic compounds, carotenoids, and antioxidant activity in a super-sweet corn hybrid. Pesq. agropec. bras. 2022, 57, e02663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo, C.D.; Badea, M.; Colombo, F.; Orgiu, F.; Frigerio, G.; Pastor, R.F.; Restani, P. Antioxidant Activity of wine assessed by different in vitro methods. BIO Web Conf. 2017, 9, 04008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülçin, İ.; Huyut, Z.; Elmastaş, M.; Aboul-Enein, H.Y. Radical scavenging and antioxidant activity of tannic acid. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 2010, 3, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesarović, J.; Srdić, J.; Mladenović-Drinić, S.; Dragičević, V.; Simić, M.; Brankov, M.; Milojković-Opsenica, D. Evaluation of the nutritional profile of sweet maize after herbicide and foliar fertilizer application. Journal of Cereal Science 2019, 87, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Temperature (0C) | 2022 Months | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | June | July | Aug | Sept | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| Min | −7.0 | −5.5 | −2 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 14 | 12.2 | 18 | 5 | 0.2 | −1.4 | −7.6 |

| Max | 5 | 16.8 | 14.5 | 18.2 | 25.4 | 29.2 | 30.8 | 33.0 | 27.0 | 26.8 | 16.3 | 10.7 |

| Average | −5.5 | −2.4 | 2 | 10.8 | 12.4 | 18.5 | 22.2 | 24.4 | 20.2 | 13.7 | 9 | 5.5 |

| Precipitation (mm) | 21 | 19 | 44 | 67 | 30 | 66 | 42 | 15 | 102 | 44 | 54 | 12 |

| Temperature (0C) | 2023 months | |||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | June | July | Aug | Sept | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| Min | −5 | −3 | 0 | 6.0 | −2.2 | 12 | 11.2 | 13.7 | 1.2 | 6 | −5 | −4.6 |

| Max | 1 | 14 | 19 | 16 | 18.7 | 28 | 35.2 | 34.1 | 30.9 | 26 | 19.2 | 15.1 |

| Average | 0.5 | 5.1 | 7.8 | 12.1 | 13.4 | 20.9 | 23.5 | 25.1 | 21.1 | 14.7 | 8 | 3.1 |

| Precipitation (mm) | 29 | 28 | 34 | 47 | 54 | 82.8 | 69.8 | 14.4 | 32.2 | 54.4 | 45.4 | 13 |

| Factors | Chlorophyll Index | Plant Height (cm) | Ears Insertion (cm) | No of Stalks | No of Ears per Plant | Ears Weight (g) | No of Kernel Rows per Ear |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variety | |||||||

| Royalty F1 | 31.4 ± 1.0 | 220.2 ± 7.2 a | 79.4 ± 8.5 a | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 211.7 ± 8.5 ab | 14.3 ± 0.3 b |

| Hardy F1 | 34.9 ± 1.0 | 189.6 ± 9.6 b | 57.7 ± 2.7 b | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 239.2 ± 12.4 a | 16.9 ± 0.4 a |

| DBc | 33.9 ± 2.0 | 227.5 ± 7.3 a | 91.0 ± 3.2 a | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 192.3 ± 1.9 b | 13.3 ± 0.2 b |

| Signification for p≤0.05 | ns | * | * | ns | ns | * | * |

| Fertilizer | |||||||

| Chemical | 36.2 ± 0.8 a | 207.8 ± 10.8 | 73.0 ± 4.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 226.9 ± 5.9 | 15.9 ± 0.3 a |

| Organic | 32.9 ± 0.4 ab | 205.4 ± 10.9 | 75.2 ± 4.4 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.6 ± 0.2 | 205.3 ± 3.9 | 14.4 ± 0.2 b |

| Control | 31.1 ± 1.7 b | 224.1 ± 2.5 | 79.8 ± 5.5 | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 210.9 ± 15.5 | 14.2 ± 0.4 b |

| Signification for p≤0.05 | * | ns | ns | ns | ns | ns | * |

| Treatment | Ears Length (cm) | Rahis Weight (g) | Kernels Weight (g) | Dry Matter (%) | Yield per ha (kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royalty F1 | 20.96 ± 0.23 a | 90.05 ± 3.39 | 121.65 ± 5.15 b | 25.77 ± 1.44 | 10,828 ± 731 b |

| Hardy F1 | 21.6 ± 0.41 a | 92.66 ± 4.20 | 146.56 ± 8.40 a | 23.85 ± 1.33 | 13,995 ± 527 a |

| DBc | 19.78 ± 0.03 b | 96.45 ± 1.71 | 95.87 ± 3.47 c | 21.89 ± 1.22 | 7,682± 593 c |

| Signification for p≤0.05 | * | ns | * | ns | * |

| Chemical | 21.09 ± 0.31 | 92.81 ± 3.00 | 134.15 ± 2.89 | 25.14 ± 1.40 | 13,717 ± 961 a |

| Organic | 20.86 ± 0.08 | 92.88 ± 4.97 | 112.44 ± 4.23 | 22.14 ± 1.23 | 10,083 ± 667 b |

| Control | 20.40 ± 0.20 | 93.46 ± 6.42 | 117.48 ± 9.75 | 24.23 ± 1.35 | 8,705 ± 95 b |

| Signification for p≤0.05 | ns | ns | ns | ns | * |

| Factors | TPC (mg/g dw) |

ABTS (μM TE/g dw) |

DPPH (μM TE/g dw) |

A Chlorophyll (mg/100 g dw) |

B Chlorophyll (mg/100 g dw) |

Lycopene (mg/100 g dw) |

β-Carotene (mg/100 g dw) | Tannins (mg CE/100 g dw) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variety | ||||||||

| Royalty F1 | 1.78b | 1.70 | 1.34 | 4.2a | 6.3a | 2.14a | nd | 0.113b |

| Hardy F1 | 2.22a | 1.80 | 1.34 | 2.2b | 3.3b | 0.98b | nd | 0.168a |

| DBc | 2.05ab | 1.71 | 1.43 | 4.0a | 6.4a | 2.08a | nd | 0.131b |

| Signification for p ≤ 0.05 | * | ns | ns | * | * | * | ns | * |

| Fertilizer | ||||||||

| Chemical | 1.99 | 1.88a | 1.52a | 3.4b | 5.3b | 1.70b | nd | 0.162a |

| Organic | 2.12 | 1.68b | 1.44a | 4.2a | 6.4a | 2.16a | nd | 0.152a |

| Control | 1.94 | 1.65b | 1.16b | 2.7c | 4.3c | 1.35c | nd | 0.097b |

| Signification for p ≤ 0.05 | ns | * | * | * | * | * | ns | * |

| Treatment | Leaf Chlorophyll Index | Plant Height (cm) | Ears Inserts (cm) | No of Stalks | No of Ears per Plant | Ears Weight (g) | No of Kernel Rows per Ear |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF1 × Chemical | 32.8 ± 3.2 ab | 209.3 ± 14.1 abc | 69.1 ± 13.4 bcd | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.7 ± 0.2 ab | 263.7 ± 20.9 a | 17.7 ± 0.3 a |

| RF1 × Organic | 31.2 ± 1.34 ab | 212.9 ± 19.3 abc | 77.9 ± 4.4 abc | 1.7 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 ab | 200.2 ± 8.1 bc | 13.0 ± 0.6 b |

| RF1 × Control | 30.33± 3.0 b | 238.4 ± 5.4 a | 91.0 ± 9.0 a | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.2 ab | 171.2 ± 18.2 c | 12.1 ± 0.5 b |

| HF1 × Chemical | 39.9 ± 3.2 a | 183.7 ± 11.1 bc | 56.5 ± 3.7 cd | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.3 a | 239.6 ± 9.5 ab | 17.0 ± 0.3 a |

| HF1 × Organic | 32.3 ± 2.7 ab | 176.5 ± 7.7 c | 51.6 ± 4.5 d | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.1 ab | 214.8 ± 18.5 bc | 16.4 ± 0.8 a |

| HF1 × Control | 32.4 ± 2.5 ab | 208.5 ± 10.6 abc | 64.9 ± 1.1 bcd | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.1 b | 263.2 ± 18.5 a | 17.5 ± 0.9 a |

| DBc × Chemical | 36.0 ± 3.9 ab | 230.6 ± 8.1 ab | 93.4 ± 5.1 a | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.1 ab | 177.5 ± 6.3 c | 12.9 ± 0.6 b |

| DBc × Organic | 35.1 ± 1.2 ab | 226.7 ± 26.3 ab | 96.2 ± 4.7 a | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.2 ab | 201.1 ± 4.5 bc | 13.9 ± 0.7 b |

| DBc × Control | 30.6 ± 1.9 b | 225.3 ± 15.1 ab | 83.4 ± 7.1 ab | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.3 b | 198.3 ± 13.9 bc | 13.1 ± 0.6 b |

| Signification for p≤0.05 | * | * | * | ns | * | * | * |

| Treatment | Ears Length (cm) | Rahis Weight (g) | Kernels Weight (g) | Yield per ha (kg) | Dry Matter (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royalty F1 × Chemical | 22.10 ± 0.69 a | 102.58 ± 4.88 ab | 161.16 ± 16.39 a | 15,064 ± 692 ab | 30.24 ± 1.69 a |

| Royalty F1 × Organic | 20.61 ± 0.41 abcd | 89.16 ± 3.33 abc | 110.98 ± 5.97 bc | 9,345 ± 1,953 cd | 24.92 ± 1.39 b |

| Royalty F1 × Control | 20.16 ± 0.62 bcd | 78.40 ± 11.12 c | 92.81 ± 7.17 c | 8,073 ± 395 d | 22.16 ± 1.23 bc |

| Hardy F1 × Chemical | 22.08 ± 0.41 a | 86.38 ± 5.39 abc | 153.22 ± 5.71 a | 17,510 ± 2,767 a | 22.16 ± 1.24 bc |

| Hardy F1 × Organic | 21.55 ± 0.54 ab | 85.19 ± 4.09 bc | 129.59 ± 16.36 ab | 13,288 ± 977 bc | 19.36 ± 1.08 c |

| Hardy F1 × Control | 21.19 ± 0.44 abc | 106.40 ± 6.66 a | 156.87 ± 12.24 a | 11,187 ± 824 bcd | 30.03 ± 1.67 a |

| DBc × Chemical | 19.08 ± 0.36 d | 89.48 ± 1.60 abc | 88.07 ± 5.96 c | 8,576 ± 444 d | 23.03 ± 1.28 bc |

| DBc × Organic | 20.41 ± 0.41 bcd | 104.31 ± 9.06 ab | 96.76 ± 5.80 bc | 7,616 ± 1,055 d | 22.14 ± 1.23 bc |

| DBc × Control | 19.87 ± 0.35 cd | 95.57 ± 2.50 abc | 102.77 ± 11.99 bc | 6,853 ± 705.7 d | 20.49 ± 1.14 bc |

| Signification for p≤0.05 | * | * | * | * | * |

| Treatment | TPC (mg GAE/g dw) |

ABTS (μM TE/g dw) |

DPPH (μM TE/g dw) |

A Chlorophyll (mg/100 g dw) |

B Chlorophyll (mg/100 g dw) |

Lycopene (mg/100 g dw) |

β-Carotene (mg/100 g dw) |

Tannins (mg CE/100 g dw) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RF1 × Chemical | 1.50c | 1.89 | 1.67a | 1.6 fg | 2.5ef | 0.77f | nd | 0.147bc |

| RF1 × Organic | 2.14abc | 1.69 | 1.36abc | 7.6a | 11.2a | 3.96a | nd | 0.118cde |

| RF1 × Control | 1.72bc | 1.54 | 1.01bc | 3.3cd | 5.3cd | 1.69cd | nd | 0.075e |

| HF1 × Chemical | 2.88a | 1.83 | 1.62a | 3.2cd | 4.6d | 1.45cd | nd | 0.190ab |

| HF1 × Organic | 2.41ab | 1.91 | 1.43abc | 1.3 g | 2.0f | 0.56f | nd | 0.225a |

| HF1 × Control | 1.37c | 1.66 | 0.98c | 2.1ef | 3.2e | 0.93ef | nd | 0.089de |

| DBc × Chemical | 1.58c | 1.93 | 1.28abc | 5.5b | 8.7b | 2.87b | nd | 0.150bc |

| DBc × Organic | 1.83bc | 1.45 | 1.54ab | 3.7c | 6.0c | 1.95c | nd | 0.114cde |

| DBc × Control | 2.74a | 1.75 | 1.48abc | 2.7de | 4.5d | 1.43de | nd | 0.129cd |

| Signification for p≤0.05 | * | ns | * | * | * | * | ns | * |

| Traits | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | PC6 | PC7 | PC8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant height | -0.2857 | -0.1313 | 0.0310 | -0.0807 | 0.1075 | 0.2282 | -0.1864 | -0.1568 |

| No of stalks | -0.0472 | -0.1216 | 0.4247 | -0.4449 | -0.1356 | 0.0837 | -0.1389 | -0.0936 |

| Leaf chlorophyll index | 0.1399 | 0.1606 | 0.1470 | 0.4242 | 0.0363 | 0.3429 | -0.4530 | -0.1007 |

| Ears insertion height | -0.2927 | -0.0344 | 0.0186 | 0.0560 | 0.1882 | 0.2735 | -0.1934 | 0.0512 |

| No of ears per plant | 0.1724 | 0.2790 | 0.1696 | -0.0208 | -0.1805 | 0.3561 | -0.1612 | 0.2952 |

| Ears weight | 0.2595 | -0.2424 | 0.0700 | 0.0953 | 0.0954 | -0.1111 | 0.0324 | -0.0831 |

| No of kernel rows per ear | 0.3007 | -0.1528 | -0.0017 | 0.0775 | 0.0005 | 0.0280 | 0.0256 | 0.0526 |

| Ears length | 0.2860 | -0.0670 | 0.0980 | -0.0997 | 0.0590 | -0.2480 | -0.0975 | 0.3804 |

| Rahis weight | 0.0469 | -0.3222 | -0.0804 | 0.3486 | 0.4053 | 0.0536 | 0.1069 | -0.0378 |

| Kernels weight | 0.2858 | -0.1755 | 0.1076 | -0.0044 | -0.0230 | -0.1459 | 0.0023 | -0.0853 |

| Dry matter | 0.0688 | -0.3911 | 0.2401 | 0.0762 | -0.0739 | 0.0327 | 0.0825 | -0.0081 |

| Humidity | -0.0688 | 0.3911 | -0.2401 | -0.0762 | 0.0739 | -0.0327 | -0.0825 | 0.0081 |

| Yield per ha | 0.2981 | 0.0331 | 0.1961 | -0.0305 | -0.0813 | 0.0367 | -0.1029 | 0.1048 |

| TPC | 0.0866 | 0.3378 | -0.0403 | -0.0565 | 0.2550 | -0.4044 | -0.0483 | -0.4328 |

| ABTS | 0.1677 | 0.1289 | 0.1490 | -0.0644 | -0.1158 | 0.3973 | 0.5668 | -0.4342 |

| DPPH | 0.1346 | 0.1596 | 0.1645 | 0.0622 | 0.6399 | 0.1113 | 0.1194 | 0.2144 |

| Chlorophyll A | -0.2012 | 0.1149 | 0.3182 | 0.3189 | -0.1346 | -0.2051 | 0.1172 | 0.0485 |

| Chlorophyll B | -0.2199 | 0.1131 | 0.2958 | 0.3128 | -0.1130 | -0.1576 | 0.1105 | 0.0349 |

| Lycopene | -0.2153 | 0.1116 | 0.3057 | 0.3022 | -0.1025 | -0.1861 | 0.1364 | 0.0620 |

| Tannins | 0.2147 | 0.2823 | -0.0252 | 0.0476 | 0.0463 | 0.1936 | 0.3342 | 0.1089 |

| Fructose | -0.2127 | 0.0628 | 0.2240 | -0.3374 | 0.2457 | -0.0408 | 0.2507 | 0.3749 |

| Glucose | 0.1052 | 0.1290 | 0.4371 | -0.1674 | 0.2449 | -0.1242 | -0.2594 | -0.3198 |

| Sucrose | 0.2608 | 0.2000 | -0.0816 | 0.0823 | -0.2325 | -0.1721 | -0.0791 | 0.0926 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).