Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

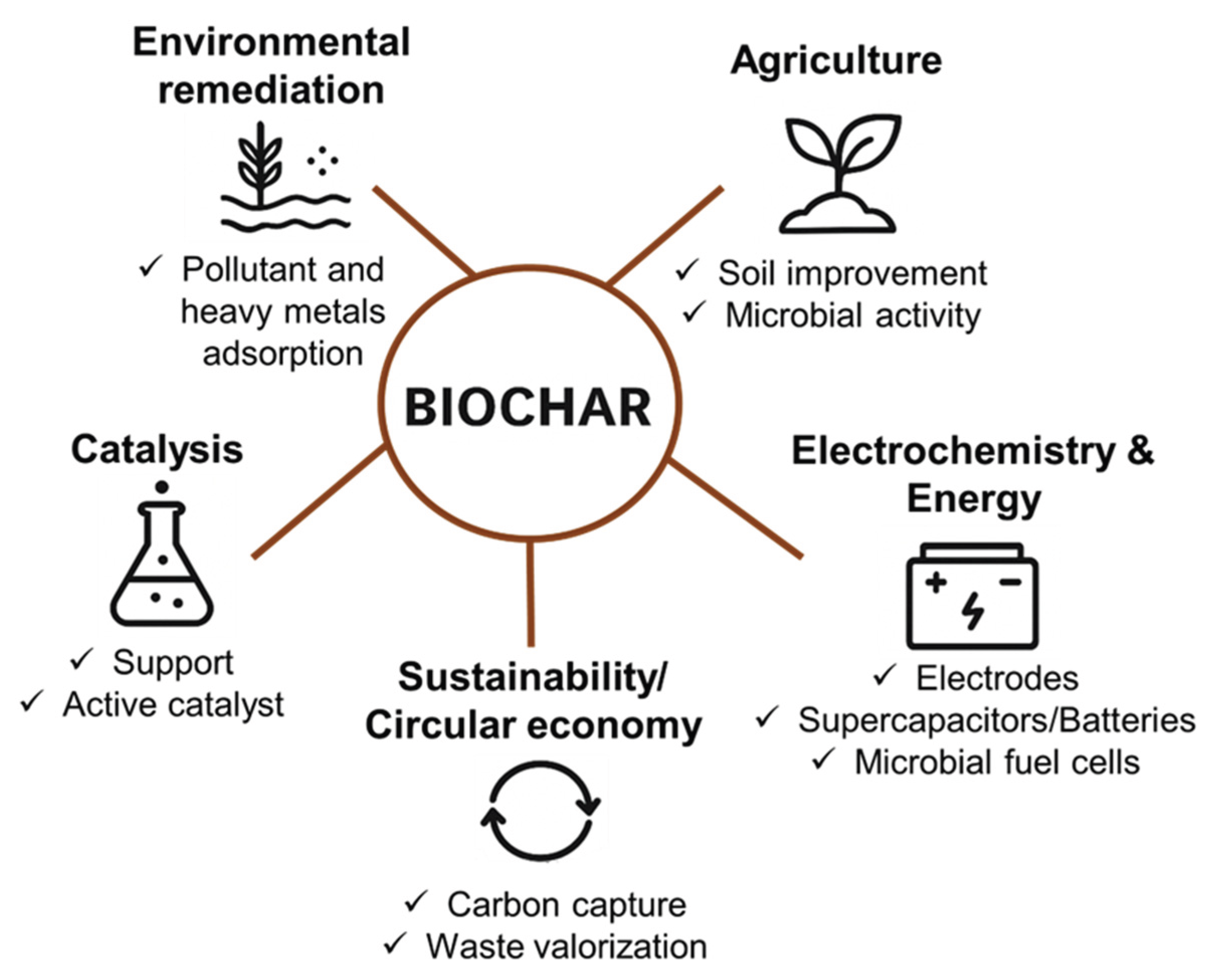

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

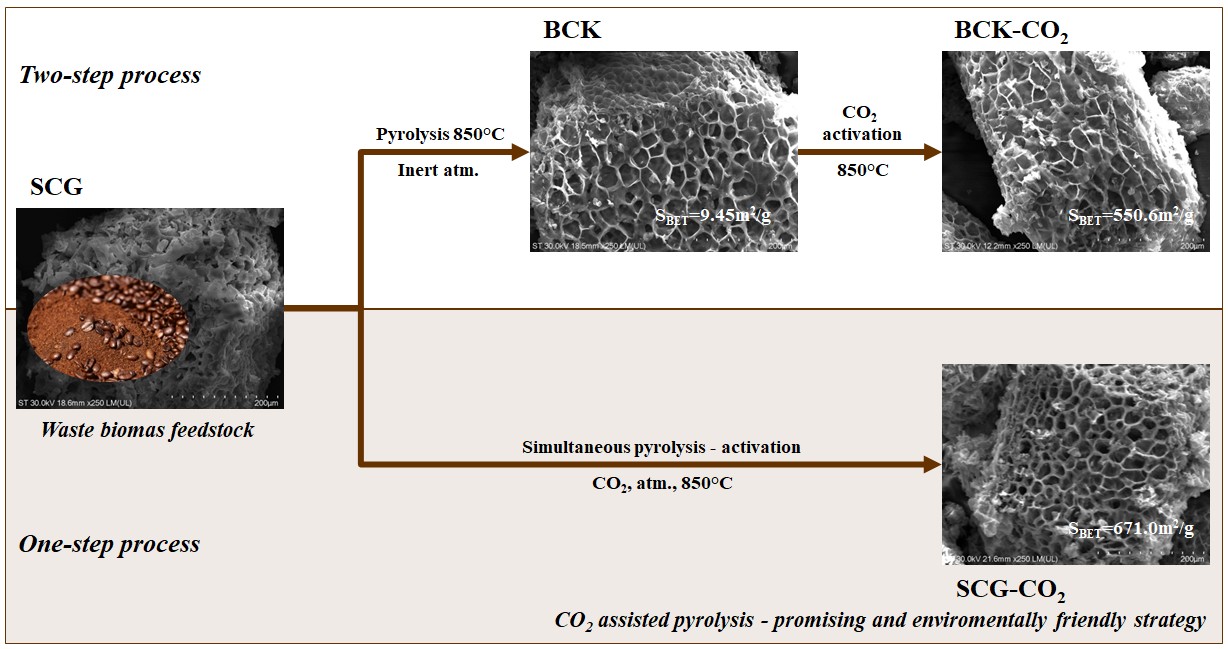

2.1. Production of Biochar from Spent Coffee Grounds

2.2. Determination of Biochar Yield and Proximate Composition

2.3. Surface Characterization of Biochar

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Determination of Biochar Yield and Proximate Composition

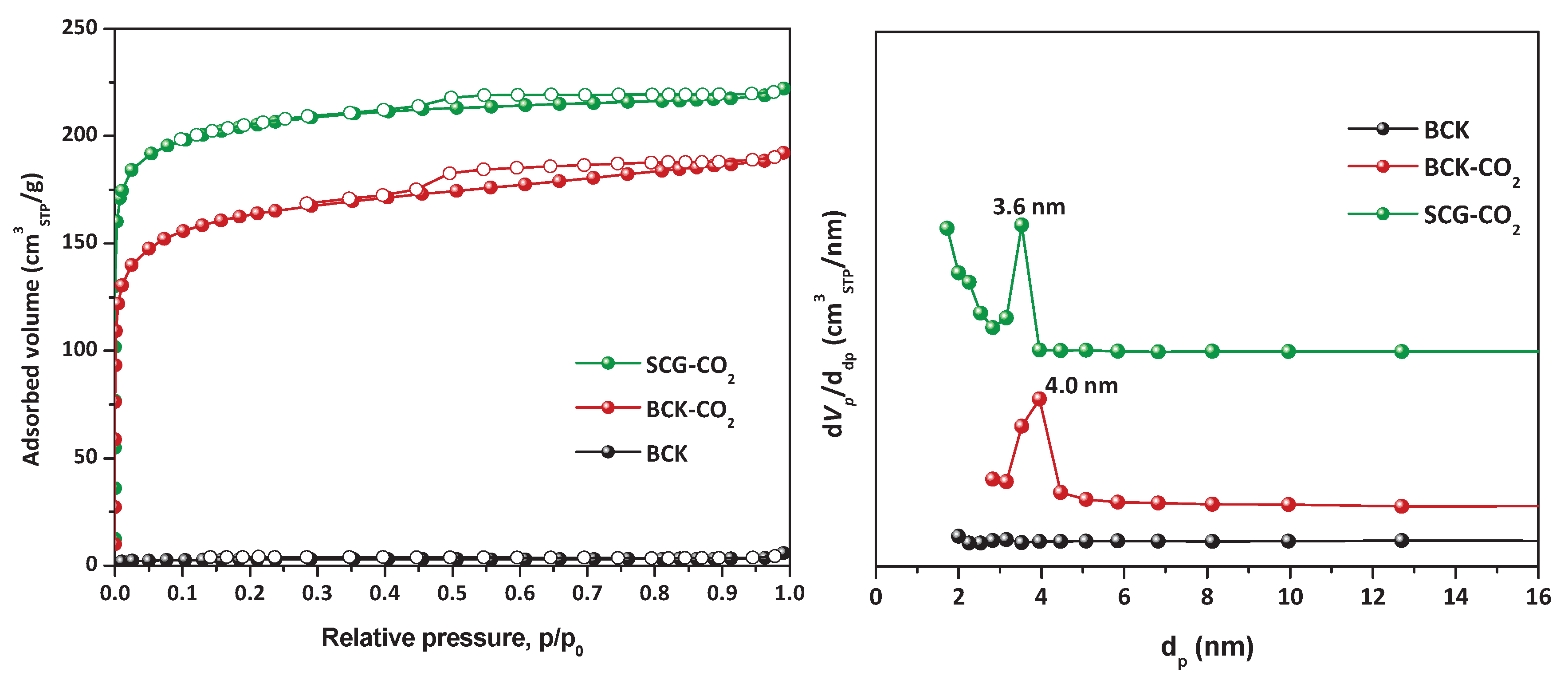

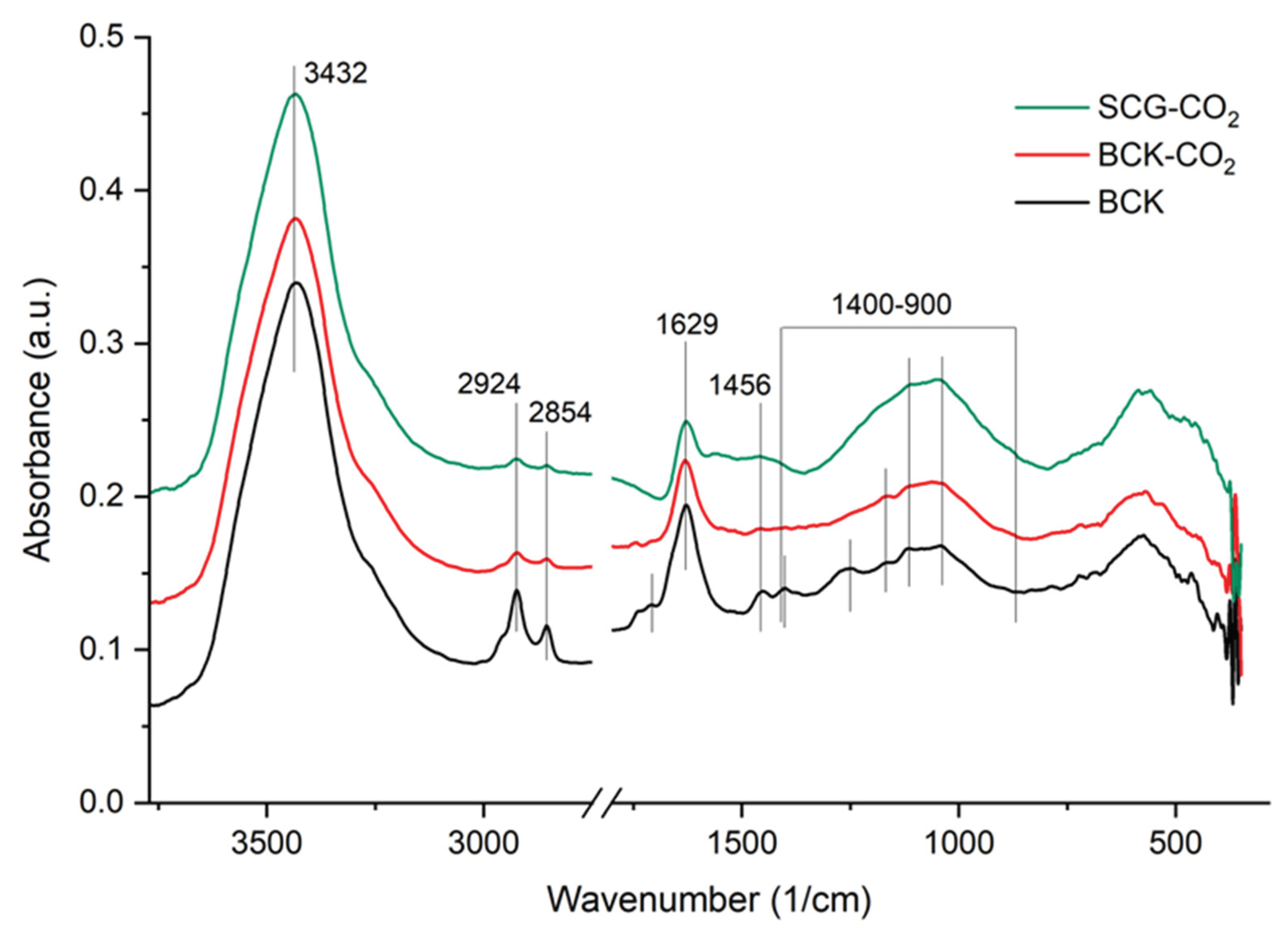

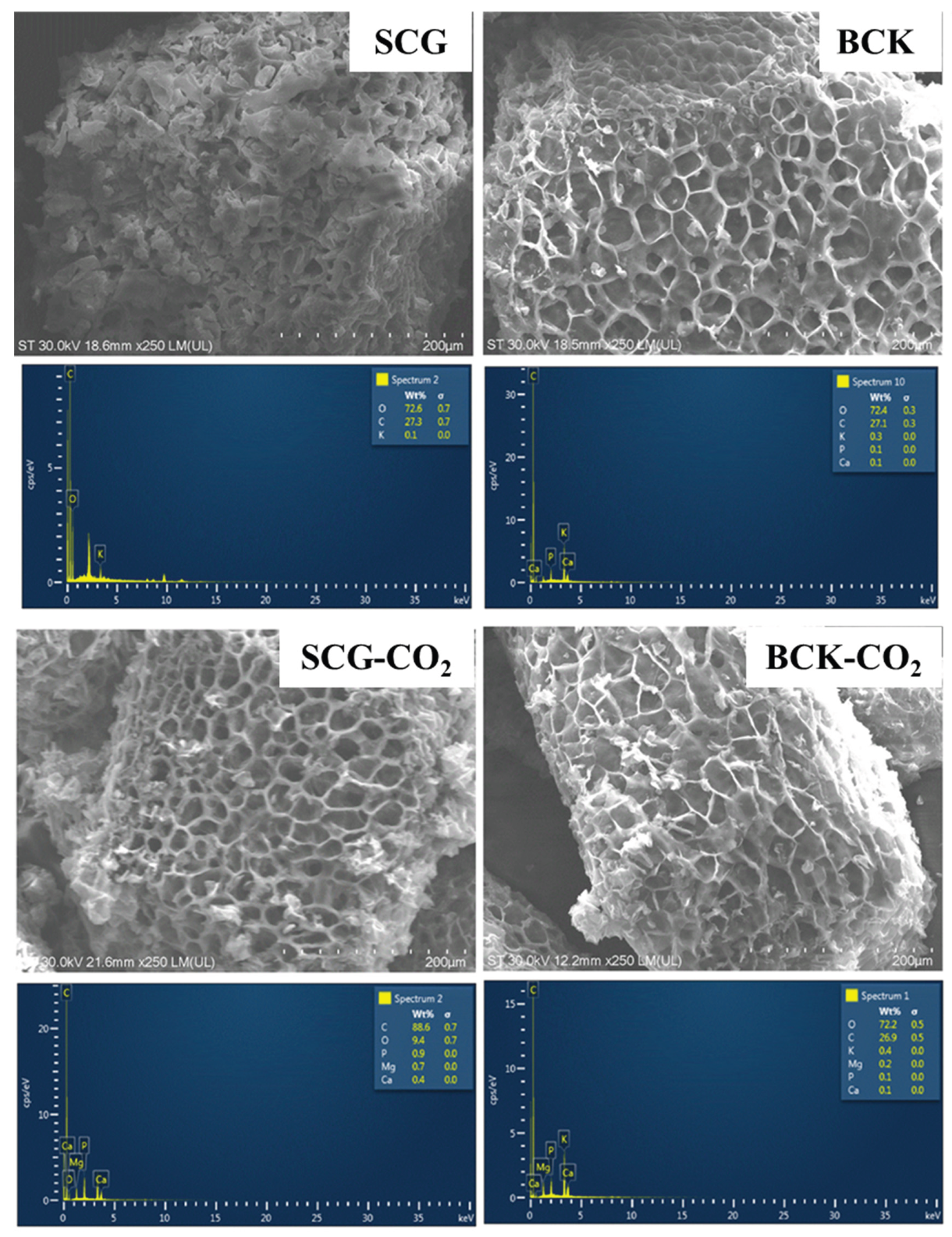

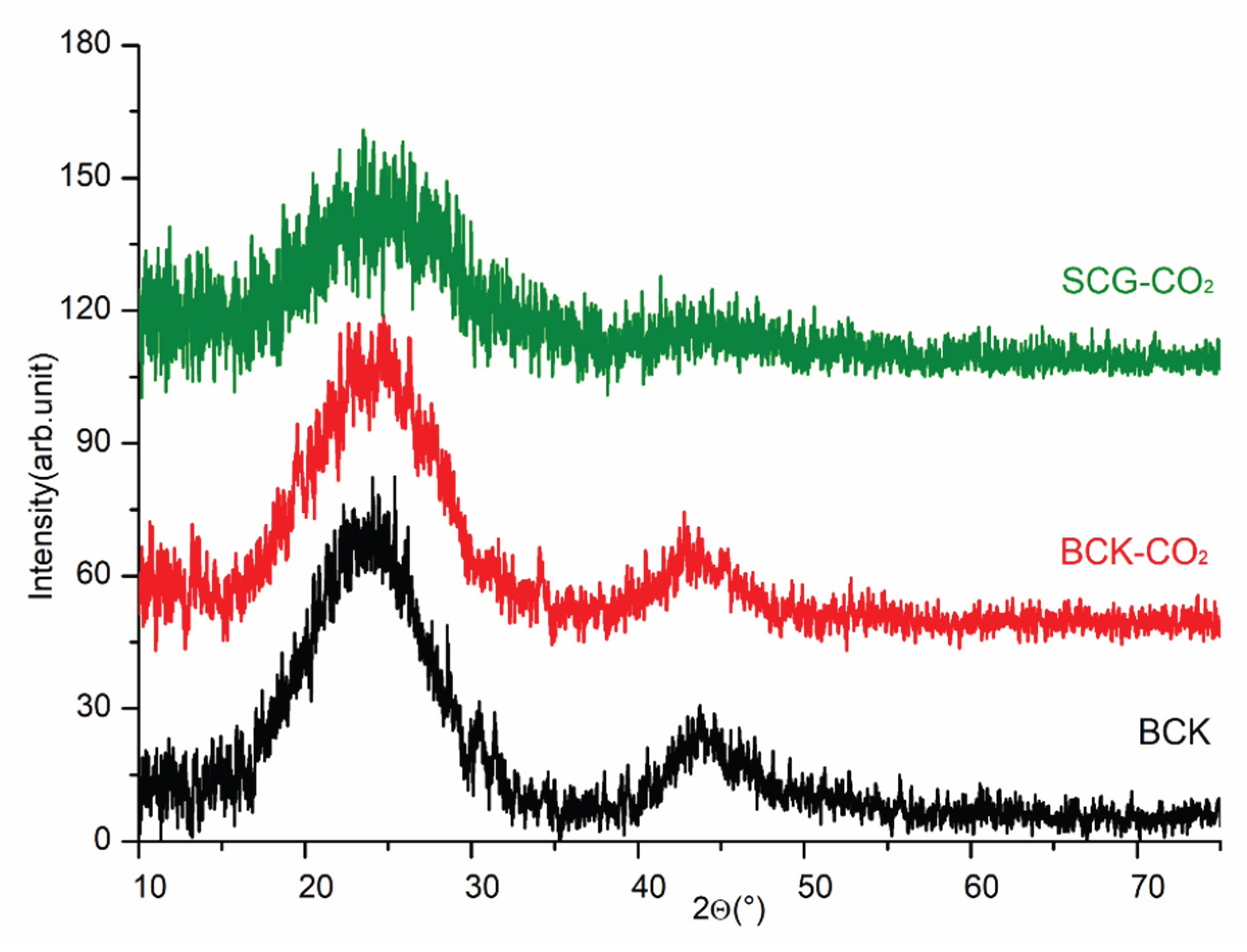

3.2. Surface Characterization of Biochar

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Varkolu, M.; Gundekari, S.; Omvesh; Palla, V.C.S.; Kumar, P.; Bhattacharjee, S.; Vinodkumar, T. Recent advances in biochar production, characterization, and environmental applications. Catalysts 2025, 15, 243. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Huang, P.; Ma, M.; Meng, X.; Hao, Y.; Sun, H. Effects of biochar on the environmental behavior of pesticides. In Biochar in Agriculture for Achieving Sustainable Development Goals; Tsang, D.C.W., Ok, Y.S., Academic Press, 2022, pp. 129-138. [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; He, L.; Jiang, M.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J.; Gustave, W.; Wang, S.; Deng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Z. Biochar for the removal of emerging pollutants from aquatic systems: A review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Jiang, M.; He, L.; Zhang, Z.; Gustave, W.; Viththika, M.; Niazi, N.K.; Chen, B.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; He, F. Challenges in safe environmental applications of biochar: identifying risks and unintended consequence. Biochar 2025, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Mu, G.; Wu, X.; Liu, Y.; Luo, W.; Wen, X. Remediation of soil contaminated by heavy metals using biochar: strategies and future prospects. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2023, 32, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, B.; Shao, Q.; Shi, J.; Yang, C.; Chu, H. Application of biochar for the adsorption of organic pollutants from wastewater: Modification strategies, mechanisms and challenges. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 300, 121925–121950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beljin, J.; Đukanović, N.; Anojčić, J.; Simetić, T.; Apostolović, T.; Mutić, S.; Maletić, S. Biochar in the remediation of organic pollutants in water: A review of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon and pesticide removal. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasseghian, Y.; Nadagouda, M.M.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Biochar-enhanced bioremediation of eutrophic waters impacted by algal blooms. J. Environ. Manage. 2024, 367, 122044–122057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Ekanayake, A.; Tyagi, V.K.; Vithanage, M.; Singh, R.; Rao, Y.R.S. Emerging contaminants in polluted waters: Harnessing Biochar's potential for effective treatment. J. Environ. Manage. 2025, 373, 123778–123806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, A.; Song, X.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Han, Z.; Gao, H.; Gao, Q.; Zha, Y. , Liu, Y.; Wu, X.; Wang, G. Biochar enhances soil hydrological function by improving the pore structure of saline soil. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 306, 109170–109182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndede, E.O.; Kurebito, S.; Idowu, O.; Tokunari, T.; Jindo, K. The potential of biochar to enhance the water retention properties of sandy agricultural soils. Agronomy 2022, 12, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ighalo, J.O.; Ohoro, C.R.; Ojukwu, V.E.; Oniye, M.; Shaikh, W.A.; Biswas, J.K.; Seth, C.S.; Mohan, G.B.M.; Chandran, S.A.; Rangabhashiyam, S. Biochar for ameliorating soil fertility and microbial diversity: From production to action of the black gold. iScience 2025, 28, 111524–111560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kaushik, R.; Pandit, M.K.; Lee, Y.-H. Biochar-induced microbial shifts: Advancing soil sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1748–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, J.; Ahmad, W.; Munsif, F.; Khan, A.; Zou, Z. Advances and prospects of biochar in improving soil fertility, biochemical quality, and environmental applications. Front. Environ. Sci. 2023, 11, 1114752–1114769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, R.P.; Astruc, D. Biochar as a support for nanocatalysts and other reagents: Recent advances and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 426, 213585–213622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, U.; Azim, Y. Biochar-Based Catalysts for the Production of Chemical and Energy. In: Biochar. Sustainable Materials and Technology; Bhawani, S.A., Bhat, A.H., Wahi, R., Ngaini, Z., Eds.; Springer, Singapore, 2024; pp. 169-189. [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.; Ponnada, S.; Kumari, I.; Sharma, R.K. Biochar as Catalyst. In Biochar-Based Catalysts. Sustainable Materials and Technology; Bhawani, S.A., Umar, K., Mohamad Ibrahim, M.N., Alotaibi, K.M. Springer, Singapore, 2024; pp. 17-28. [CrossRef]

- Azman, N.S.; Khairuddin, N.; Tengku Azmi, T.S.M.; Seenivasagam, S.; Hassan, M.A. Application of biochar from woodchip as catalyst support for biodiesel production. Catalysts 2023, 13, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, U.; Paul, S.J.; Jain, S. Biochar: A source of nano catalyst in transesterification process. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 46, 5501–5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadale, M.; Sarangi, P.K.; Jose, N.; Ray, D.P.; Jadhav, M.; Shrivastava, P.; Kumar T, N.; Debnath, S.; Shakyawar, D.B. A comprehensive review on biochar catalyst for advancement of pyrolytic conversion of biomass into valuable biofuels. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2025, In Press, Corrected Proof, 106232–106256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinke, C.; De Oliveira, P.R.; Bonacin, J.A.; Janegitz, B.C.; Mangrich, A.S.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F. State-of-the-art and perspectives in the use of biochar for electrochemical and electroanalytical applications. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 5272–5301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedulkar, A.P.; Dang, V.D.; Thamilselvan, A.; Doong, R.; Pandit, B. Sustainable high-energy supercapacitors: Metal oxide-agricultural waste biochar composites paving the way for a greener future. J. Energy Storage 2024, 77, 109723–109740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H; Gong, X.; Jia, L.; Chen, F.; Rao, Z.; Jing, S.; Tsiakaras, P. Highly efficient Li-O2 batteries based on self-standing NiFeP@NC/BC cathode derived from biochar supported Prussian blue analogues. J. Elecroanal. Chem. 2020, 867, 114124–114132. [CrossRef]

- Shyam, S.; Daimary, M.; Narayan, M.; Sarma, H. Biochar-based electroanalytical materials: Towards sustainable, high-performance electrocatalysts and sensors. Next Materials 2025, 8, 100873–100887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitha, A.; Devi, N.R. Prospects of biochar as a renewable resource for electricity. In Biochar - productive technologies, properties and applications; Bartoli, M., Giorcelli, M., Tagliaferro, A., Eds.; IntechOpen, London, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Biswal, B.K.; Balasubramanian, R. Use of biomass-derived biochar as a sustainable material for carbon sequestration in soil: recent advancements and future perspectives. NPJ Mater. Sustain. 2025, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyam, S.; Ahmed, S.; Joshi, S.J.; Sarma, H. Biochar as a soil amendment: implications for soil health, carbon sequestration, and climate resilience. Discov. Soil 2025, 2, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martiny, T.R.; Avila, L.B.; Rodrigues, T.L.; Tholozan, L.V.; Meili, L.; Felk de Almeida, A.R.; Silveira da Rosa, G. From waste to wealth: Exploring biochar’s role in environmental remediation and resource optimization. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 453, 142237–142261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasquez-Pinas, J.A.; Ghofrani-Isfahani, P.; Maya, D.Y.; Ravenni, G.; Castro, L.E.N.; Angelidaki, I.; Forster-Carneiro, T. Biochar in the circular bioeconomy: a bibliometric analysis of technologies, applications, and trends. Biofpr 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, R.T.; Ahmad, P.; Rafatullah, M. Insights into Biochar Applications: A Sustainable Strategy toward Carbon Neutrality and Circular Economy. In Catalytic applications of biochar for environmental remediation: Sustainable strategies towards a circular economy; Kapoor, R.T., Sillanpää, M., Rafatullah, M., Eds.; ACS Publications, 2024; Volume 2, pp. 1-30. [CrossRef]

- Sinyoung, S.; Jeeraro, A.; Udomkun, P.; Kunchariyakun, K.; Graham, M.; Kaewlom, P. Enhancing CO2 sequestration through corn stalk biochar-enhanced mortar: A synergistic approach with algal growth for carbon capture applications. Sustainability 2025, 17, 342–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Wang, L.; Ostrikov, K.; Huang, J. Designing carbon-based porous materials for carbon dioxide capture. Adv. Mater. Interfaces. 2023, 11, 2202290–2202318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibitoye, S.E.; Loha, C.; Mahamood, R.M.; Jen, T.-C.; Alam, M.; Sarkar, I.; Das, P.; Akinlabi, E.T. An overview of biochar production techniques and application in iron and steel industries. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2024, 11, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngaba, M.J.Y., Yemele, O.M., Hu, B.; Rennenberg, H.; Biochar application as a green clean-up method: bibliometric analysis of current trends and future perspectives. Biochar 2025, 7, 83. [CrossRef]

- Afshar, M.; Mofatteh, S. Biochar for a sustainable future: Environmentally friendly production and diverse applications. RINENG 2024, 23, 102433–102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waheed, A.; Xu, H.; Qiao, X.; Aili, A.; Yiremaikebayi, Y.; Haitao, D.; Muhammad, M. Biochar in sustainable agriculture and Climate Mitigation: Mechanisms, challenges, and applications in the circular bioeconomy. Biomass&Bioenergy 2025, 193, 107531–107545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; De Almeida Moreira, B.R.; Bai, Y.; Nadar, C.G.; Feng, Y.; Yadav, S. Assessing biochar's impact on greenhouse gas emissions, microbial biomass, and enzyme activities in agricultural soils through meta-analysis and machine learning. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 963, 178541–178554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Gupta, R.; Zhang, Q.; You, S. Review of biochar production via crop residue pyrolysis: Development and perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128423–128437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammini, A.; Brundin, E.; Grill, R.; Zellweger, H. Supply chain uncertainties of small-scale coffee husk-biochar production for activated carbon in Vietnam. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8069–8096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazbakhsh, M.; Nabavi, S.R.; Jafarian, S. Optimized production of high-performance activated biochar from sugarcane bagasse via systematic pyrolysis and chemical activation. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1554–1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sial, T.A.; Rajpar, I.; Khan, M.N.; Ali, A.; Shan, M.; Rajput, A.B.; Shah, P.A.N. Impact of fruit and vegetable wastes on the environment and possible management strategies. In Planet Earth: Scientific proposals to solve urgent issues. Núñez-Delgado, A. Eds.; Springer, Cham., 2024; pp. 307-330. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-53208-5_14. [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Guin, B.; Wilbanks, E.; Sternberg, J. Synthesis and characterization of soy hull biochar-based flexible polyurethane foam composites. Materials 2025, 18, 2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsvetanova, F.; Naydenova, G.; Boyadzhieva, S. Sunflower seed hulls and meal—A waste with diverse biotechnological benefits. Biomass 2025, 5, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Page-Dumroese, D.S.; Han, H.-S.; Anderson, N. Role of biochar made from low-value woody forest residues in ecological sustainability and carbon neutrality. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2025, 89, e20793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcina, A.; Petrillo, A.; Travaglioni, M.; di Chiara, S.; De Felice, F. A comparative life cycle assessment of different spent coffee grounds reuse strategies and a sensitivity analysis for verifying the environmental convenience based on the location of sites. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135727–135743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, N.; Liu, Z. , Yu, T., Yan, F. Spent coffee groundss: Present and future of environmentally friendly applications on industries-A review. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2024, 143, 104312–104325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, H.; Abolore, R.S.; Jaiswal, S.; Jaiswal, A.K. Toward circular economy: Potentials of spent coffee groundss in bioproducts and chemical production. Biomass 2024, 4, 286–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Food Waste Research. https://www.epa.gov/land-research/food-waste-research.

- Smith, A.; Brown, K.; Ogilvie, S.; Rushton, K.; Bates, J. Waste Management Options and Climate Change. Final report to the European Commission, DG Environment. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/pdf/waste/studies/climate_change.pdf.

- Skic, K.; Adamczuk, A.; Gryta, A.; Boguta, P.; Tóth, T.; Jozefaciuk, G. Surface areas and adsorption energies of biochars estimated from nitrogen and water vapour adsorption isotherms. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 30362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amalina, F.; Razak, A.S.A.; Krishnan, S.; Zularisam, A.W.; Nasrullah, M. A comprehensive assessment of the method for producing biochar, its characterization, stability, and potential applications in regenerative economic sustainability – A review. Cleaner Materials 2022, 3, 100045–100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braghiroli, F.L.; Bouafif, H.; Neculita, C.M.; Koubaa, A. Influence of pyro-gasification and activation conditions on the porosity of activated biochars: A literature review. Waste Biomass Valor. 2020, 11, 5079–5098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Wang, J.; Sun, W.; Peng, X.; Qi, X. Production of algae-derived biochar and its application in pollutants adsorption - A Mini Review. Separations 2025, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz, B.; Sommer-Márquez, A.; Ordoñez, P.E.; Bastardo-González, E.; Ricaurte, M.; Navas-Cárdenas, C. Synthesis methods, properties, and modifications of biochar-based materials for wastewater treatment: A Review. Resources 2024, 13, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakhar, A.; Canatoy, R.C.; Galgo, S.J.C.; Rafique, M.; Sarfraz, R. Advancements in modified biochar production techniques and soil application: a critical review. Fuel 2025, 400, 135745–135762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonappan, L.; Liu, Y.; Roussi, T.; Brar, S.K.; Surampalli, R.Y. Development of biochar-based green functional materials using organic acids for environmental applications. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 244, 118841–118851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.; Fang, Z.; Bolan, N.; Bhatnagar, A.; Gao, B.; Hou, D.; Wang, S.; Song, H.; Yang, X.; Shaheen, S.M.; Meng, J.; Chen, W.; Rinklebe, J.; Wang, H. Engineered biochar for environmental decontamination in aquatic and soil systems: a review. Carbon Res. 2022, 1, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murtaza, G.; Ahmed, Z.; Valipour, M.; Ali, I.; Usman, M.; Iqbal, R.; Zulfiqar, U.; Rizwan, M.; Mahmood, S.; Ullah, A.; Arslan, M.; Habib ur Rehman, M.; Ditta, A.; Tariq, A. Recent trends and economic significance of modified/functionalized biochars for remediation of environmental pollutants. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Tian, W.; Wang, Y. Effect of Pore Structure on CO2 adsorption performance for ZnCl2/FeCl3/H2O(g) co-activated walnut shell-based biochar. Atmosphere 2022, 13, 1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, Y.; Huang, J.; Zimmerman, A.R.; Chen, H.; Hu, X.; Gao, B. Mechanisms and adsorption capacities of hydrogen peroxide modified ball milled biochar for the removal of methylene blue from aqueous solutions. Bioresour. Technol. 2021, 337, 125432–125439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, S.M.X.; Chin, B.L.F.; Huang, M.M.; Yiin, C.L.; Kurnia, J.C; Lam, S.S.; Tan, Y.H.; Chai, Y.H.; Rashidi, N.A. Harnessing bamboo waste for high-performance supercapacitors: A comprehensive review of activation methods and applications. J. Energy Storage 2025, 105, 114613–114631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yameen, M.Z. , Naqvi, S.R., Juchelková, D.; Khan, M.N.A. Harnessing the power of functionalized biochar: progress, challenges, and future perspectives in energy, water treatment, and environmental sustainability. Biochar 2024, 6, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjadi, B.; Zubatiuk (Klimenko), T.A.; Leszczynska, D.; Chen, W.-Y. Chemical activation of biochar for energy and environmental applications: A comprehensive review. Rev. Chem. Eng. 2019, 35, 777–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Singh, B.; Acharya, B. A comprehensive review on activated carbon from pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass: An application for energy and the environment. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2024, 7, 100228–100253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahcheragh, S.K. , Bagheri Mohagheghi, M.M. & Shirpay, A. Effect of physical and chemical activation methods on the structure, optical absorbance, band gap and urbach energy of porous activated carbon. SN Appl. Sci. 2023, 5, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashidi, N.A. , Yusup, S. Production of palm kernel shell-based activated carbon by direct physical activation for carbon dioxide adsorption. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 33732–33746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagireddi, S.; Agarwal, J.R.; Vedapuri, D. Carbon dioxide capture, utilization, and sequestration: current status, challenges, and future prospects for global decarbonization. ACS Eng. Au 2023, 4, 22–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maniarasu, R.; Rathore, S.K.; Murugan, S. Biomass-based activated carbon for CO2 adsorption–A review. Energ. Environ. 2022, 34, 1674–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz-Ruiz, A.; Maisano, S.; Chiodo, V.; Urbani, F.; Dorodo, F. , Sanchez-Silva, L. Enhancing CO2 capture performance through activation of olive pomace biochar: A comparative study of physical and chemical methods. Sustain. Mater Techno. 2024, 42, e01177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-H.; Tsai, W.-T. Optimization of physical activation process by CO2 for activated carbon preparation from Honduras mahogany pod husk. Materials 2023, 16, 6558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, A.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Patah, M.F.A.; Bharath, G.; AlMohamadi, H.; Tang, D.Y.Y.; Show, P.L.; Banat, F. A comprehensive insight on activated carbon production from agricultural biomass: Parametric analysis, challenges, future recommendations & machine learning modelling. Resour. Cons. Recy. Adv. 2025, 27, 200284–200301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, G.; Canavesi, R.L.S.; Di Stasi, C.; Celzard, A.; Fierro, V.; Manyà, J.J. Biomass-derived carbons physically activated in one or two steps for CH4/CO2 separation. Renew. Energy 2022, 191, 122–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yek, P.N.Y.; Peng, W.; Wong, C.C.; Liew, R.K.; Ho, Y.L.; Mahari, W.A.W.; Azwar, E.; Yuan, T.Q.; Tabatabaei, M.; Aghbashlo, M.; Sonne, C.; Lam, S.S. Engineered biochar via microwave CO2 and steam pyrolysis to treat carcinogenic Congo red dye. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 395, 122636–122345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamian, R.; Heidarpour, M.; Mousavi, S.F.; Afyuni, M. Characterization and sodium sorption capacity of biochar and activated carbon prepared from rice husk. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2015, 17, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.S.; Park, C.R. Titration method for the identification of surface functional groups. In Materials Science and Engineering of Carbon, Inagaki, M., Kang, F., Butterworth-Heinemann, 2016, 273-286. [CrossRef]

- De Souza, L.Z.M.; Pinto, B.C.; Alves, A.B.; De Oliveira Ribeiro, A.V.; Feliciano, D.C.T.; Da Silva, L.H.; Dias, T.T.M.; Yilmaz, M.; De Oliveira, M.A.; Da Silva Bezerra, A.C.; Ferreira, O.E.; De Lima, R.P.; Do Santos Pimenta, L.P.; Machado, A.R.T. Ecotoxicological effects of biochar obtained from spent coffee groundss. Mat. Res. 2022, 225 (Suppl 2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, N.A.N.N.; Ahmad, R.; Ani, A.Y.; Ismail, S.N.A.S. Pyrolysis of spent coffee grounds: optimization of operating parameters on product yield. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1495, 012007. [CrossRef]

- Illingworth, J.M.; Rand, B.; Williams, P.T. Understanding the mechanism of two-step, pyrolysis-alkali chemical activation of fibrous biomass for the production of activated carbon fibre matting. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 235, 107348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, A.; Okolie, J.A.; Niu, C.; Dalai, A.K. Experimental and modeling studies of torrefaction of spent coffee groundss and coffee husk: effects on surface chemistry and carbon dioxide capture performance. ACS Omega. 2021, 7, 638–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spokas, K.A.; Novak, J.M.; Stewart, C.E.; Cantrell, K.B.; Uchimiya, M.; DuSaire, M.G.; Ro, K.S. Qualitative analysis of volatile organic compounds on biochar. Chemosphere 2011, 85, 869–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V. , Olivier, J. P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report), Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tala, W.; Chantara, S. Use of spent coffee grounds biochar as ambient PAHs sorbent and novel extraction method for GC-MS analysis. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2019, 26, 13025–13040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capunitan, J.A.; Capareda, S.C. Assessing the potential for biofuel production of corn stover pyrolysis using a pressurized batch reactor. Fuel 2012, 95, 563–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; He, Z.; Uchimiya, M. Comparison of biochar formation from various agricultural by-products using FTIR spectroscopy. Mod. Appl. Sci. 2015, 9, 246–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, S.; Yac’cob, N.A.N.; Ngadi, N.; Hassan, O.; Inuwa, I.M. From pollutant to solution of wastewater pollution: Synthesis of activated carbon from textile sludge for dye adsorption. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 26, 870–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Hu, Y.; Abbey, L.; Cesarino, I.; Goonetilleke, A.; He, Q. Exploring the properties and potential uses of biocarbon from spent coffee groundss: A comparative look at dry and wet processing methods. Processes 2023, 11, 2099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Gao, N. Biomass-based carbon materials for CO2 capture: A review. J. CO2 Util. 2023, 68, 102373–102390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roncancio, R.; Gore, J.P. CO2 char gasification: A systematic review from 2014 to 2020. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2021, 10, 100060–100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- França, E.d.S.; de Souza, A.F.; Rodríguez, D.M.; de Paula, N.Z.; Neves, A.G.D.; Cardoso, K.B.B.; Campos-Takaki, G.M.d.; de Lima, M.A.B.; Porto, A.L.F. Valorization of Spent Coffee Groundss as a Substrate for Fungal Laccase Production and Biosorbents for Textile Dye Decolorization. Fermentation 2025, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, L.; Baldassin, D.; Di Michele, A.; Bittencourt, C.; Menegazzo, F.; Signoretto, M. Activation strategies for rice husk biochar: enhancing porosity and performance as a support for Pd catalysts in hydrogenation reactions. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2025, 15, 5101–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanichok, N.; Kolkovskyi, P.; Ivanichok, O.; Kotsyubynsky, V.; Boychuk, V.; Rachiy, B.; Bembenek, M.; Warguła, Ł.; Abaszade, R.; Ropyak, L. Effect of thermal activation on the structure and electrochemical properties of carbon material obtained from walnut shells. Materials 2024, 17, 2514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Deng, M. Eco-friendly preparation of biomass-derived porous carbon and its electrochemical properties. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 22689–22697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cano, F.J.; Reyes-Vallejo, O.; Sánchez-Albores, R.M.; Sebastian, P.J.; Cruz-Salomón, A.; Hernández-Cruz, M.d.C.; Montejo-López, W.; González Reyes, M.; Serrano Ramirez, R.d.P.; Torres-Ventura, H.H. Activated biochar from pineapple crown biomass: A high-efficiency adsorbent for organic dye removal. Sustainability 2025, 17, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S.; Yadav, A.; Rangari, V. Surface tailored spent coffee grounds derived carbon reinforced waste HDPE composites for 3D printing application. Compos. Part C-Open 2025, 16, 100570–100583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Proximate composition | Textural characterisation | Surface acid-base properties | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASH (%) | VM (%) | FC (%) | TC | SBETa (m2/g) | Vpb (cm3/g) | dp (nm) |

Total acidity (mmol/g) | Total basicity (mmol/g) | |

| BCK | 7.7 | 11.9 | 80.4 | 0.87 | 9.75 | 0.005 | - | 4.6 | 2.2 |

| BCK-CO2 | 8.4 | 14.4 | 77.2 | 0.84 | 550.59 | 0.291 | 4 | 3.2 | 1.9 |

| SCG-CO2 | 9.6 | 17.3 | 73.1 | 0.80 | 671.04 | 0.331 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 1.9 |

| Parameter | Two-step pyrolysis - CO2 activation | One-step CO2 assisted pyrolysis |

|---|---|---|

| Process design | Pyrolysis under inert gas + separate CO2 activation | Integrated pyrolysis and activation under CO2 |

| Number of thermal stages | 2 | 1 |

| Energy demand | High (requires reheating) | Lower (single heating step) |

| CO2 utilization | Only during activation | During the entire thermal process |

| Time efficiency | Longer (two distinct stages) | Shorter (one-step process) |

| Environmental footprint | Higher (greater energy input) | Reduced (lower energy, CO2 valorization) |

| Textural properties | Relative high surface area | Superior |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).