Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

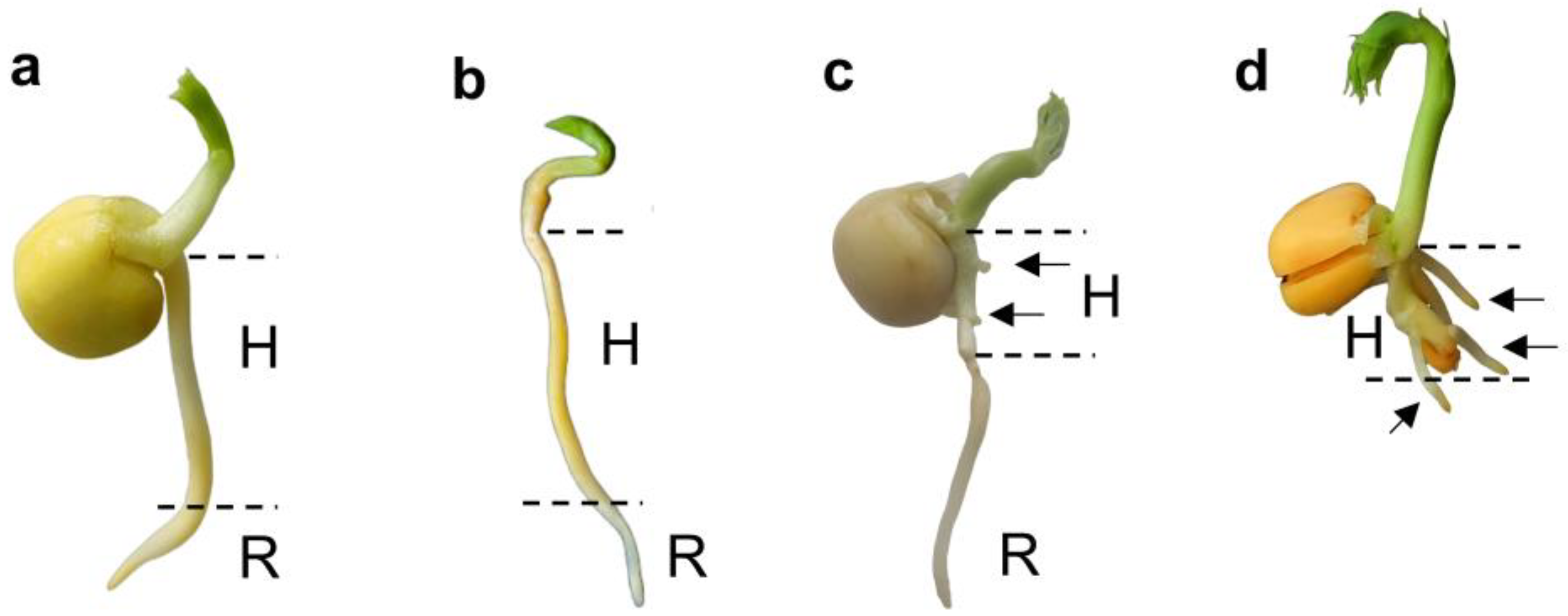

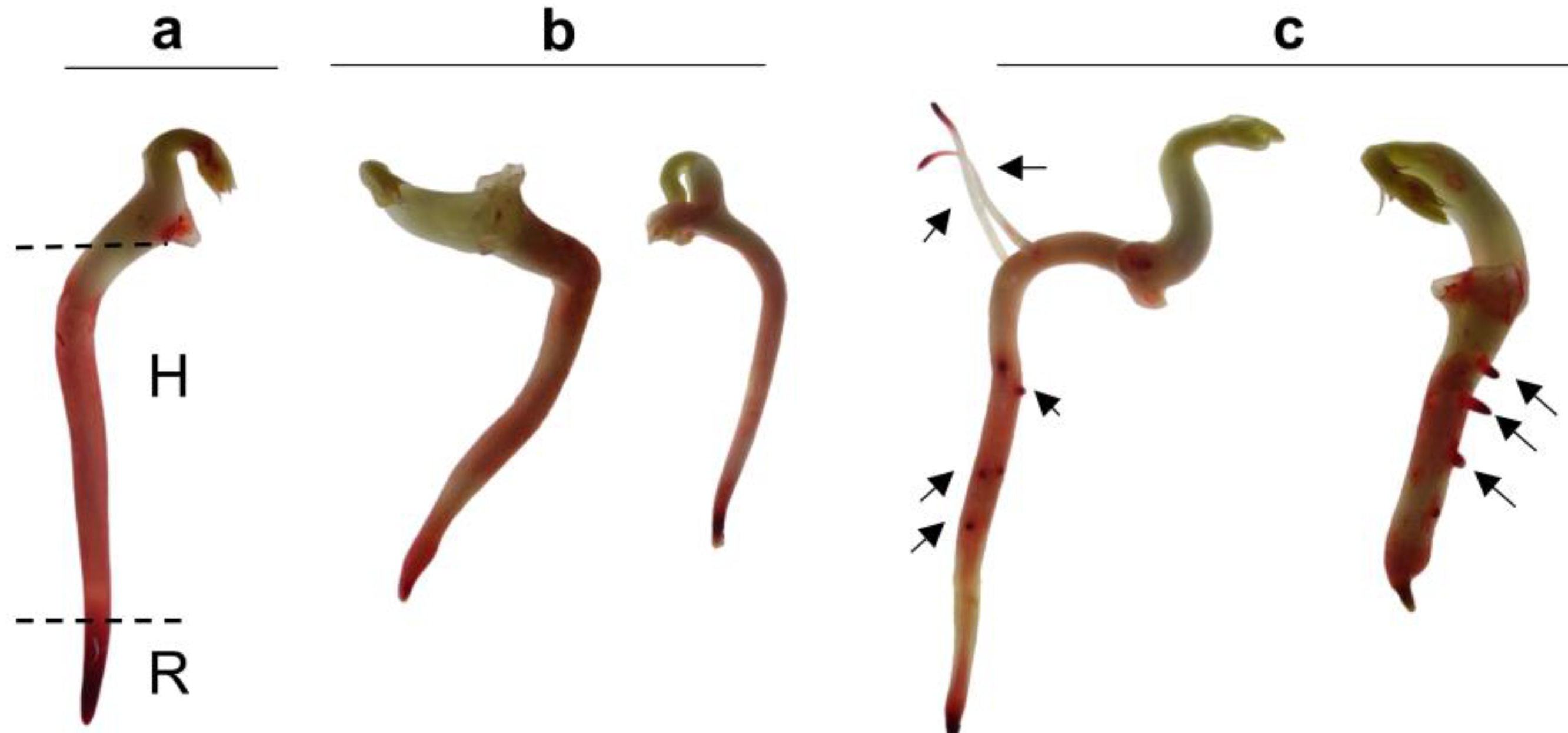

2.1. Effects of ‘Drying and Rehydration’ Treatment on Growth of Pisum sativum L. Seedlings

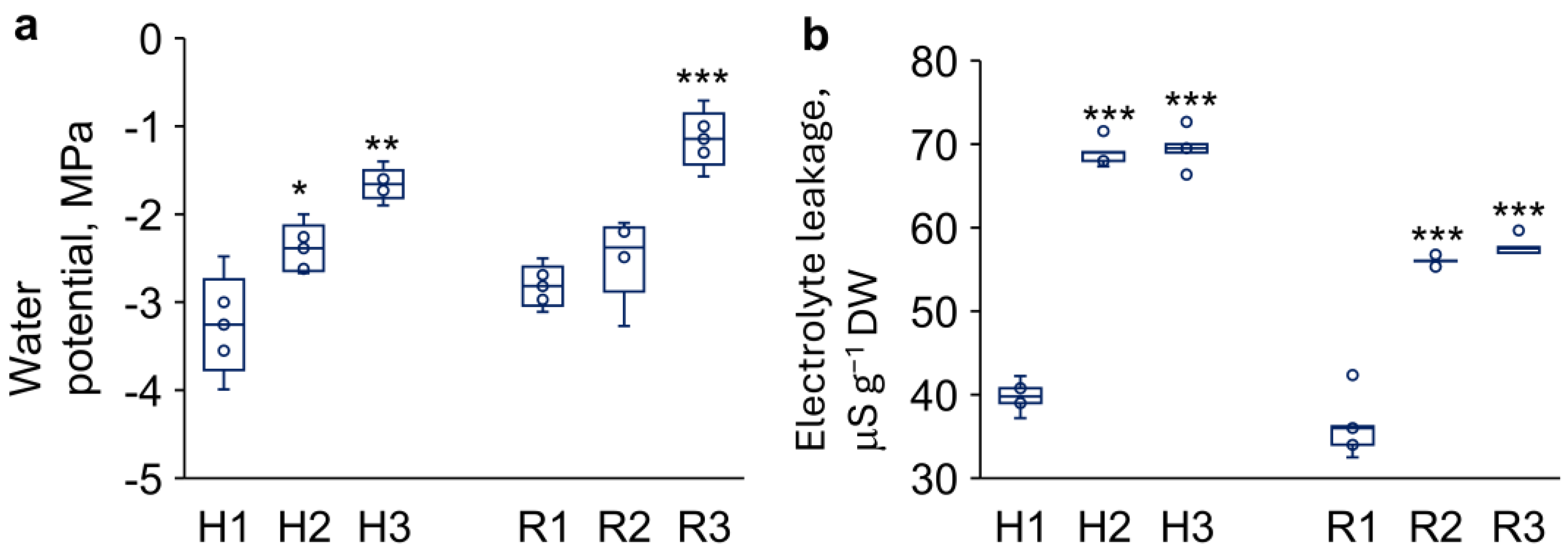

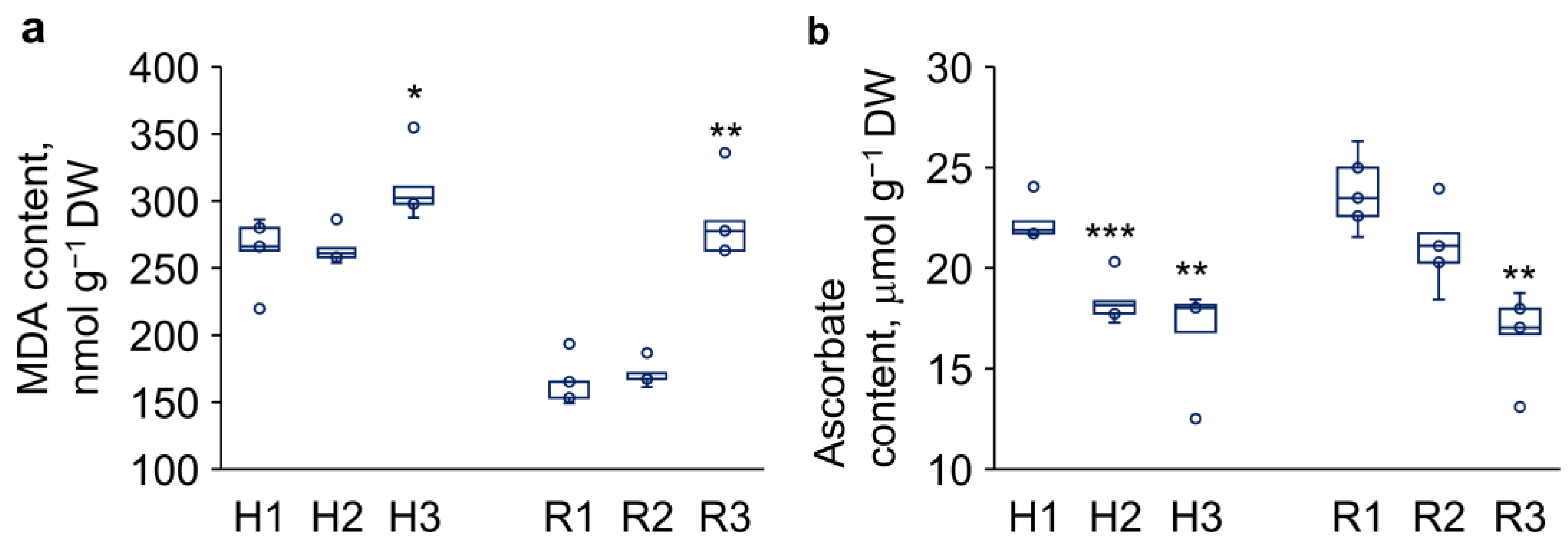

2.2. Physiological and Biochemical Responses of Pisum sativum L. Seedlings to ‘Drying and Rehydration’ Treatment

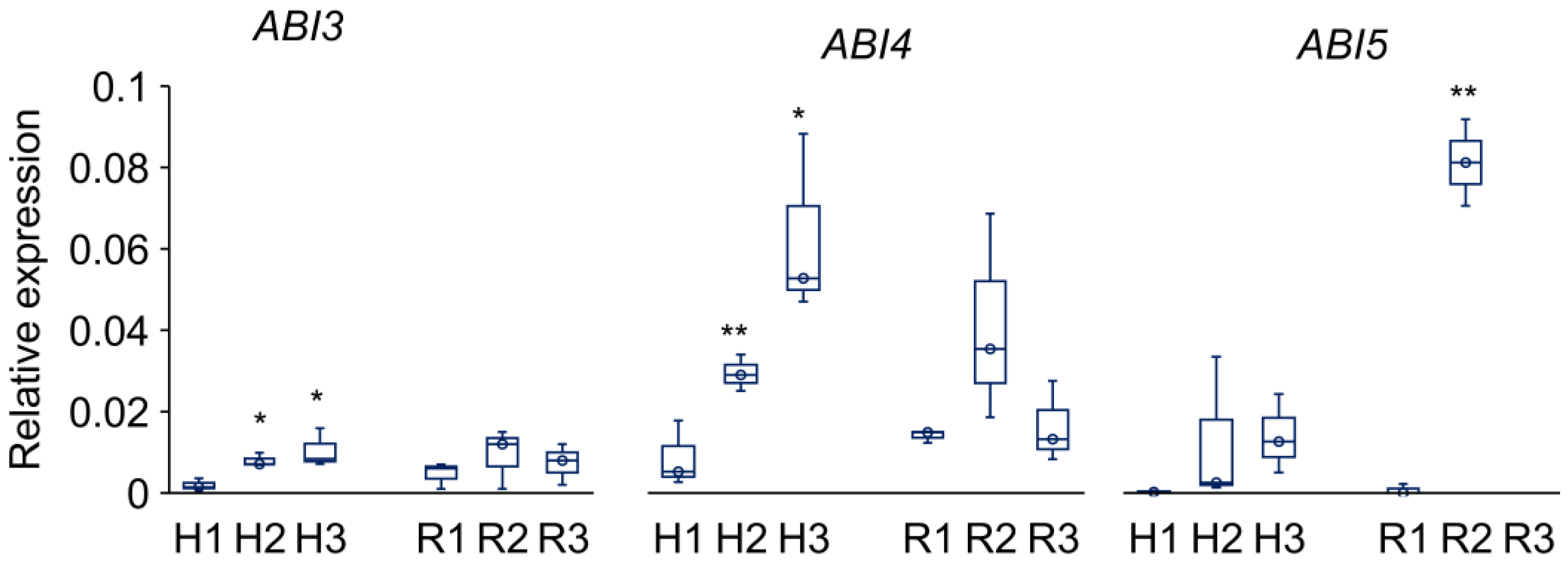

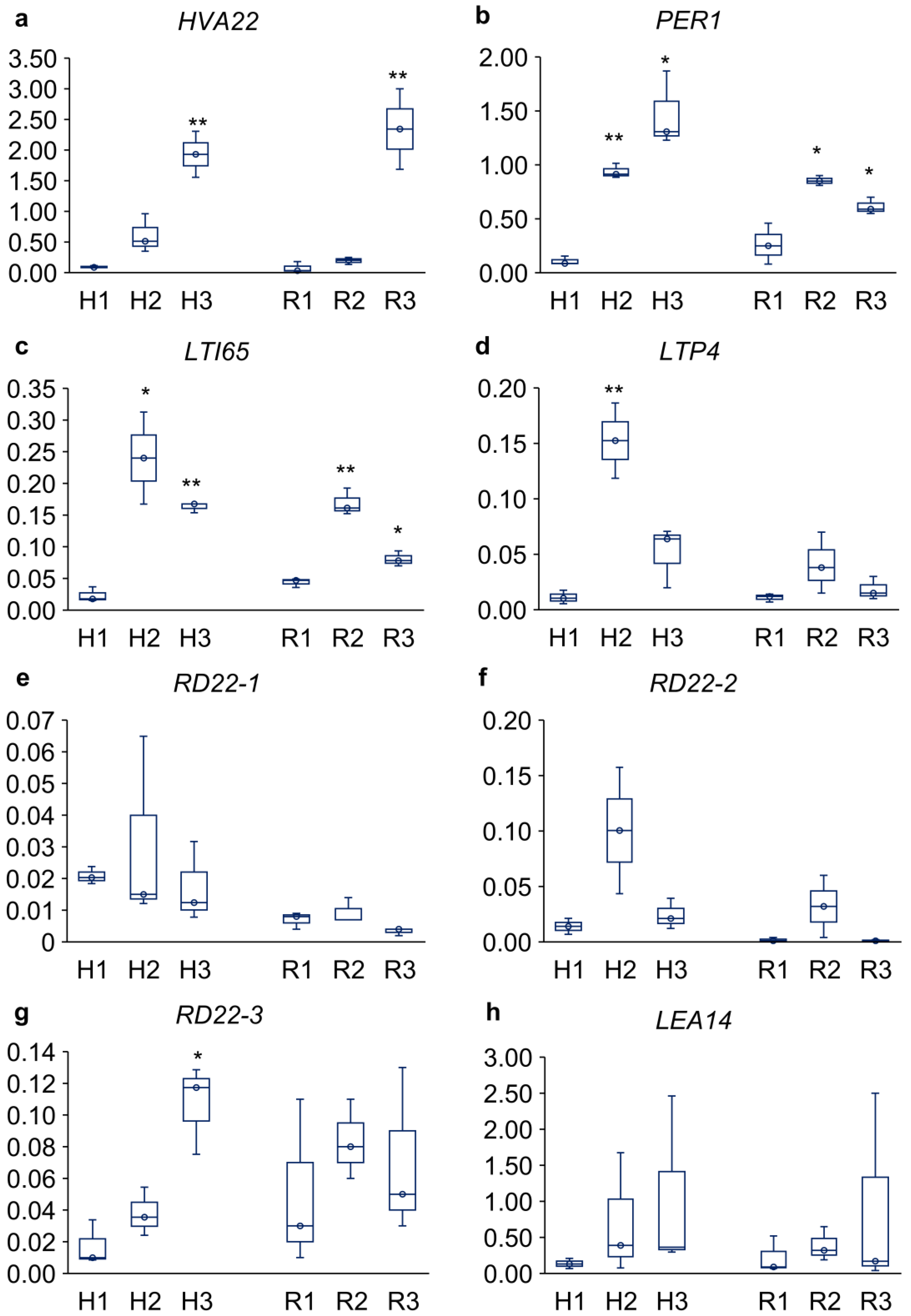

2.3. Changes in Expression of ABA-Depended Genes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

4.2. Tissue Viability

4.3. Water Potential and Cell Membrane Integrity

4.4. Biochemical Stress Markers

4.5. RNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Juenger, T.E.; Verslues, P.E. Time for a drought experiment: Do you know your plants’ water status? Plant Cell 2023, 35, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.A.; Hussain, S.; Khaliq, A.; Ashraf, U.; Anjum, S.A.; Men, S.; Wang, L. Chilling and drought stresses in crop plants: implications, cross talk, and potential management opportunities. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrant, J.M.; Hilhorst, H. Crops for dry environments. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 74, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M.; Messina, C.D. Breeding crops for drought-affected environments and improved climate resilience. Plant Cell 2023, 35, 162–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marks, R.A.; Ekwealor, J.T.B.; Artur, M.A.S.; Bondi, L.; Boothby, T.C.; Carmo, O.M.S.; Centeno, D.C.; Coe, K.K.; Dace, H.J.W.; Field, S.; et al. Life on the dry side: a roadmap to understanding desiccation tolerance and accelerating translational applications. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrant, J.M.; Moore, J.P. Programming desiccation-tolerance: from plants to seeds to resurrection plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2011, 14, 340–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosete-Enríquez, M.; Juárez-González, V.R.; Escobar-Muciño, E.; Muñoz-Rojas, J.; Quintero-Hernández, V. Surviving desiccation: key factors underlying tolerance in prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Protoplasma 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffe, A.L.; Castelle, C.J.; Banfield, J.F. Habitat transition in the evolution of bacteria and archaea. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 77, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliver, M.J.; Farrant, J.M.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; Mundree, S.; Williams, B.; Bewley, J.D. Desiccation tolerance: Avoiding cellular damage during drying and rehydration. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2020, 71, 435–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.-C.D.; Cooper, K.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; Farrant, J.M. Orthodox seeds and resurrection plants: two of a kind? Plant Physiol. 2017, 175, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, B.; Li, X.; Liang, Y.; Chen, M.; Liu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Oliver, M.J.; et al. Drying without dying: A genome database for desiccation-tolerant plants and evolution of desiccation tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2023, kiad672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolikova, G.; Leonova, T.; Vashurina, N.; Frolov, A.; Medvedev, S. Desiccation tolerance as the basis of long-term seed viability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, A.; Buijs, G.; Ligterink, W.; Hilhorst, H. Evolutionary ecophysiology of seed desiccation sensitivity. Funct. Plant Biol. 2018, 45, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leprince, O.; Pellizzaro, A.; Berriri, S.; Buitink, J. Late seed maturation: drying without dying. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 68, erw363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matilla, A.J. The Orthodox dry seeds are alive: A clear example of desiccation tolerance. Plants 2021, 11, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepiniec, L.; Devic, M.; Roscoe, T.J.; Bouyer, D.; Zhou, D.-X.; Boulard, C.; Baud, S.; Dubreucq, B. Molecular and epigenetic regulations and functions of the LAFL transcriptional regulators that control seed development. Plant Reprod. 2018, 31, 291–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, M.; Hoy, R.; Lu, B.; Song, L. Team effort: Combinatorial control of seed maturation by transcription factors. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 102091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhang, S.; Shan, S.; Xiang, Y. DELAY OF GERMINATION 1, the master regulator of seed dormancy, integrates the regulatory network of phytohormones at the transcriptional level to control seed dormancy. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2022, 44, 6205–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artur, M.A.S.; Zhao, T.; Ligterink, W.; Schranz, E.; Hilhorst, H.W.M. Dissecting the genomic diversification of late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) protein gene families in plants. Genome Biol. Evol. 2019, 11, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, D.; Li, Y.; Fang, T.; Shi, X.; Chen, X. Specific roles of tocopherols and tocotrienols in seed longevity and germination tolerance to abiotic stress in transgenic rice. Plant Sci. 2016, 244, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaraju, M.; Kumar, S.A.; Reddy, P.S.; Kumar, A.; Rao, D.M.; Kavi Kishor, P.B. Genome-scale identification, classification, and tissue specific expression analysis of late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) genes under abiotic stress conditions in Sorghum bicolor L. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0209980. [CrossRef]

- Roach, T.; Nagel, M.; Börner, A.; Eberle, C.; Kranner, I. Changes in tocochromanols and glutathione reveal differences in the mechanisms of seed ageing under seedbank conditions and controlled deterioration in barley. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2018, 156, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, N.; Rajjou, L.; North, H.M.; Debeaujon, I.; Marion-Poll, A.; Seo, M. Staying alive: molecular aspects of seed longevity. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016, 57, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, J.; Ischebeck, T. Ties between stress and lipid droplets pre-date seeds. Trends Plant Sci. 2020, 25, 1203–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchnak, I.; Coulon, D.; Salis, V.; D’Andréa, S.; Bréhélin, C. Lipid droplets are versatile organelles involved in plant development and plant response to environmental changes. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagano, A.; Folini, G.; Pagano, P.; Sincinelli, F.; Rossetto, A.; Macovei, A.; Balestrazzi, A. ROS accumulation as a hallmark of dehydration stress in primed and overprimed Medicago truncatula seeds. Agronomy 2022, 12, 268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demidchik, V. Mechanisms of oxidative stress in plants: From classical chemistry to cell biology. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2015, 109, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolikova, G.; Strygina, K.; Krylova, E.; Leonova, T.; Frolov, A.; Khlestkina, E.; Medvedev, S. Transition from seeds to seedlings: hormonal and epigenetic aspects. Plants 2021, 10, 1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verma, S.; Attuluri, V.P.S.; Robert, H.S. Transcriptional control of Arabidopsis seed development. Planta 2022, 255, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.-D.; Li, X.; Jiang, C.-K.; Wong, G.K.-S.; Rothfels, C.J.; Rao, G.-Y. Evolutionary analysis of the LAFL genes involved in the land plant seed maturation program. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolikova, G.; Strygina, K.; Krylova, E.; Vikhorev, A.; Bilova, T.; Frolov, A.; Khlestkina, E.; Medvedev, S. Seed-to-seedling transition in Pisum sativum L.: a transcriptomic approach. Plants 2022, 11, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolikova, G.; Krylova, E.; Petřík, I.; Vilis, P.; Vikhorev, A.; Strygina, K.; Strnad, M.; Frolov, A.; Khlestkina, E.; Medvedev, S. Involvement of abscisic acid in transition of pea (Pisum sativum L.) seeds from germination to post-germination stages. Plants 2024, 13, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agam, N.; Berliner, P.R. Dew formation and water vapor adsorption in semi-arid environments—A review. J. Arid Environ. 2006, 65, 572–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruggink, T.; van der Toorn, P. Induction of desiccation tolerance in germinated seeds. Seed Sci. Res. 1995, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buitink, J.; Ly Vu, B.; Satour, P.; Leprince, O. The re-establishment of desiccation tolerance in germinated radicles of Medicago truncatula Gaertn. seeds. Seed Sci. Res. 2003, 13, 273–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, B.; Naithani, S.C. Role of reactive oxygen species and antioxidative enzymes in the loss and re-establishment of desiccation tolerance in germinated pea seeds. South African J. Bot. 2023, 163, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sano, N.; Verdier, J. The re-establishment of desiccation tolerance in germinated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) seeds. Seed Sci. Res. 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, A.C.; Davide, L.C.; Braz, G.T.; Maia, J.; de Castro, E.M.; da Silva, E.A.A. Re-induction of desiccation tolerance in germinated cowpea seeds. South African J. Bot. 2017, 113, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, S.; Powell, A. Electrical conductivity vigour test: Physiological basis and use. Seed Test. Int. 2006, 32–35. [Google Scholar]

- Demidchik, V.; Straltsova, D.; Medvedev, S.S.; Pozhvanov, G. a; Sokolik, A.; Yurin, V. Stress-induced electrolyte leakage: the role of K+-permeable channels and involvement in programmed cell death and metabolic adjustment. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 1259–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Liu, Y.; Yan, H.; You, Q.; Yi, X.; Du, Z.; Xu, W.; Su, Z. agriGO v2.0: a GO analysis toolkit for the agricultural community, 2017 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W122–W129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinsmeister, J.; Lalanne, D.; Terrasson, E.; Chatelain, E.; Vandecasteele, C.; Vu, B.L.; Dubois-Laurent, C.; Geoffriau, E.; Signor, C. Le; Dalmais, M.; et al. ABI5 is a regulator of seed maturation and longevity in legumes. Plant Cell 2016, 28, 2735–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinsmeister, J.; Lalanne, D.; Ly Vu, B.; Schoefs, B.; Marchand, J.; Dang, T.T.; Buitink, J.; Leprince, O. ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 4 coordinates eoplast formation to ensure acquisition of seed longevity during maturation in Medicago truncatula. Plant J. 2023, 113, 934–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazzarrini, S.; Song, L. LAFL factors in seed development and phase transitions. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2024, 75, 459–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolikova, G.; Medvedev, S. Seed-to-seedling transition : Novel aspects. Plants 2022, 11, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maia, J.; Dekkers, B.J.W.; Provart, N.J.; Ligterink, W.; Hilhorst, H.W.M. The re-establishment of desiccation tolerance in germinated Arabidopsis thaliana seeds and its associated transcriptome. PLoS One 2011, 6, e29123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bewley, J.D.; Bradford, K.J.; Hilhorst, H.W.M.; Nonogaki, H. Seeds: physiology of development, germination and dormancy; 3rd Ed.; Springer New York: New York, NY, 2013; ISBN 978-1-4614-4692-7. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves, J. de P.; Gasparini, K.; Picoli, E.A. de T.; Costa, M.D.-B.L.; Araujo, W.L.; Zsögön, A.; Ribeiro, D.M. Metabolic control of seed germination in legumes. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 295, 154206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Mendoza, M.; Diaz, I.; Martinez, M. Insights on the proteases involved in barley and wheat grain germination. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graham, I.A. Seed storage oil mobilization. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2008, 59, 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, K.J. A water relations analysis of seed germination rates. Plant Physiol. 1990, 94, 840–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valgimigli, L. Lipid peroxidation and antioxidant protection. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jové, M.; Mota-Martorell, N.; Pradas, I.; Martín-Gari, M.; Ayala, V.; Pamplona, R. The Advanced lipoxidation end-product malondialdehyde-lysine in aging and longevity. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharova, E.; Romanova, A. Ascorbate in the apoplast of elongating plant cells. Biol. Commun. 2018, 63, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smirnoff, N.; Wheeler, G.L. The ascorbate biosynthesis pathway in plants is known, but there is a way to go with understanding control and functions. J. Exp. Bot. 2024, 75, 2604–2630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makavitskaya, M.; Svistunenko, D.; Navaselsky, I.; Hryvusevich, P.; Mackievic, V.; Rabadanova, C.; Tyutereva, E.; Samokhina, V.; Straltsova, D.; Sokolik, A.; et al. Novel roles of ascorbate in plants: induction of cytosolic Ca2+ signals and efflux from cells via anion channels. J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3477–3489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuan, P.A.; Kumar, R.; Rehal, P.K.; Toora, P.K.; Ayele, B.T. Molecular mechanisms underlying abscisic acid/gibberellin balance in the control of seed dormancy and germination in cereals. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, K.; Zhou, W.; Chen, F.; Luo, X.; Yang, W. Abscisic acid and gibberellins antagonistically mediate plant development and abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y. Integration of ABA, GA, and light signaling in seed germination through the regulation of ABI5. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Mo, W.; Zuo, Z.; Shi, Q.; Chen, X.; Zhao, X.; Han, J. From regulation to application: the role of abscisic acid in seed and fruit development and agronomic production strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, W.; Zheng, X.; Shi, Q.; Zhao, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, Z.; Zuo, Z. Unveiling the crucial roles of abscisic acid in plant physiology: implications for enhancing stress tolerance and productivity. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Nie, K.; Zhou, H.; Yan, X.; Zhan, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Song, C. ABI5 modulates seed germination via feedback regulation of the expression of the PYR/PYL/RCAR ABA receptor genes. New Phytol. 2020, 228, 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Han, X.; Yang, M.; Zhang, M.; Pan, J.; Yu, D. The transcription factor INDUCER OF CBF EXPRESSION1 interacts with ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE5 and DELLA proteins to fine-tune abscisic acid signaling during seed germination in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2019, 31, 1520–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Li, X.; Song, P.; Wang, Y.; Ma, J. Studies on the interactions of AFPs and bZIP transcription factor ABI5. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 590, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skubacz, A.; Daszkowska-Golec, A.; Szarejko, I. The role and regulation of ABI5 (ABA-insensitive 5) in plant development, abiotic stress responses and phytohormone crosstalk. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collin, A.; Daszkowska-Golec, A.; Szarejko, I. Updates on the role of ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 5 (ABI5) and ABSCISIC ACID-RESPONSIVE ELEMENT BINDING FACTORs (ABFs) in ABA signaling in different developmental stages in plants. Cells 2021, 10, 1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Molina, L.; Mongrand, S.; Chua, N.-H. A postgermination developmental arrest checkpoint is mediated by abscisic acid and requires the ABI5 transcription factor in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001, 98, 4782–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Q.; Uknes, S.J.; Ho, T.H. Hormone response complex in a novel abscisic acid and cycloheximide-inducible barley gene. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268, 23652–23660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, Q.; Chen, C.N.; Brands, A.; Pan, S.M.; David Ho, T.H. The stress- and abscisic acid-induced barley gene HVA22: Developmental regulation and homologues in diverse organisms. Plant Mol. Biol. 2001, 45, 327–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yuan, Y.; Xing, H.; Xin, M.; Saeed, M.; Wu, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhuang, T.; Zhang, X.; Mao, L.; et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the HVA22 gene family in cotton and functional analysis of GhHVA22E1D in drought and salt tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brands, A.; Ho, T.D. Function of a plant stress-induced gene, HVA22. Synthetic enhancement screen with its yeast homolog reveals its role in vesicular traffic. Plant Physiol. 2002, 130, 1121–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Wang, L. Genome-wide identification, evolution, and expression analysis of HVA22 gene family in Brassica napus L. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2025, 72, 7495–7515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Huang, L.; Li, X.; Ma, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Lin, F.; Liu, C. Comprehensive genome-wide analysis and expression profiling of the HVA22 gene family unveils their potential roles in soybean responses to abiotic stresses. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2025, 44, 2122–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharon, K. Cloning of HVA22 homolog from Aloe vera and preliminary study of transgenic plant development. Int. J. Pure Appl. Biosci. 2017, 5, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.-J.J.; David Ho, T.-H.; Ho, T.H.D. An abscisic acid-induced protein, HVA22, inhibits gibberellin-mediated programmed cell death in cereal aleurone cells. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 1710–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.N.; Chu, C.C.; Zentella, R.; Pan, S.M.; Ho, T.H.D. AtHVA22 gene family in Arabidopsis: Phylogenetic relationship, ABA and stress regulation, and tissue-specific expression. Plant Mol. Biol. 2002, 49, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietz, K.-J. Plant Peroxiredoxins. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2003, 54, 93–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Chu, P.; Zhou, Y.; Ding, Y.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Jiang, L.; Huang, S. Ectopic expression of NnPER1, a Nelumbo nucifera 1-cysteine peroxiredoxin antioxidant, enhances seed longevity and stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2016, 88, 608–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslekås, C.; Viken, M.K.; Grini, P.E.; Nygaard, V.; Nordgard, S.H.; Meza, T.J.; Aalen, R.B. Seed 1-cysteine peroxiredoxin antioxidants are not involved in dormancy, but contribute to inhibition of germination during stress. Plant Physiol. 2003, 133, 1148–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Ruan, J.; Chu, P.; Fu, W.; Liang, Z.; Li, Y.; Tong, J.; Xiao, L.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; et al. AtPER1 enhances primary seed dormancy and reduces seed germination by suppressing the ABA catabolism and GA biosynthesis in Arabidopsis seeds. Plant J. 2020, 101, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, R.P. Handbook on tetrazolium testing; 2nd ed.; International Seed Testing Association: Zurich, Switzerland, 1993; ISBN 3906549259.

- Velikova, V.; Yordanov, I.; Edreva, A. Oxidative stress and some antioxidant systems in acid rain-treated bean plants. Plant Sci. 2000, 151, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; He, W.; Guo, J.; Chang, X.; Su, P.; Zhang, L. Increased sensitivity to salt stress in an ascorbate-deficient Arabidopsis mutant. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 3041–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frolov, A.; Bilova, T.; Paudel, G.; Berger, R.; Balcke, G.U.G.U.; Birkemeyer, C.; Wessjohann, L.A.L.A. Early responses of mature Arabidopsis thaliana plants to reduced water potential in the agar-based polyethylene glycol infusion drought model. J. Plant Physiol. 2017, 208, 70–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knopkiewicz, M.; Wojtaszek, P. Validation of reference genes for gene expression analysis using quantitative polymerase chain reaction in pea lines (Pisum sativum) with different lodging susceptibility. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2019, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).