1. Introduction

To address production needs in an organization's daily operations, innovation and product development are crucial. These things ensure that the organization stays in business and becomes more competitive. Projects are activities planned to achieve innovation or development while staying within specified time and resource limits. These undertakings need practical resources and good time management to be successful [

1,

2]. Organizations commonly undertake projects to address internal needs [

3,

4] and fulfill strategic ob-jectives [

3,

5], such as enhancing efficiency, creating new products, or adapting to changing market and regulatory demands [

6]. Projects aimed at diversifying products or meeting current requirements may result in the development of industrial production facilities, thereby affecting the company's operational strategy [

7,

8]. The project life cycle is a series of steps that take a project from start to finish [

9,

10]. It gives project leaders an organized way to ensure projects move forward and achieve their goals [

5,

10,

11,

12]. The first stage is the feasibility assessment, during which the business case is analyzed to ascertain the project's viability [

13]. The subsequent phase involves planning and organization. This ensures the organization is prepared to achieve its objectives by establishing a management framework, forming teams, and allocating resources. Engineering, construction, and testing are important parts of the implementation process. They ensure that the project's deliverables meet quality requirements before they are handed over. The closure phase formally ends the project by documenting all deliverables and ensuring that the organization receives the benefits it was supposed to. This project life cycle framework can be used in several ways, including in sequential order or with overlapping phases. The best way to use it depends on how complicated and unique each project is. There are three primary project types: infrastructure, building, and industrial [

14]. Human resources are significant for industrial initiatives, especially those involving the construction and development of production facilities [

7]. The main factor in determining whether a project will be successful is having qualified personnel [

1,

2,

10]. An expert team is essential during the engineering phase, as they turn project requirements into a clear scope of work. Experts plan, analyze, and monitor the acquisition of goods and equipment during procurement [

9]. During the construction and installation phase, a team of experts is responsible for planning, reviewing, supervising, and testing to ensure that every work item meets the project's quality requirements [

15]. In a multi-project setting, where projects may develop simultaneously, overlap, or run one after the other, it becomes harder to manage them [

4,

16,

17,

18,

19]. There are numerous ways to manage the building of production facilities in industrial construction projects. One way to do this is for the project owner to manage the project themselves, utilizing their own resources [

1,

2,

16,

18,

20]. Another method is to hire consultants to help with planning, design, supervision, and implementation. The project owner would then contract the vendors and subcontractors directly [

21]. A third option is to hire a main contractor to complete the entire project under a lump-sum or EPC (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction) contract. The contractor takes on all the project's risks. This study focuses on the execution phase of industrial construction projects, during which the project owner is tasked with hiring consultants to supervise implementation and provide expert workforce resources. These professionals are used throughout various phases, including planning, engineering, procurement, construction, and the setup of production facilities [

22]. In this situation, one of the biggest problems is accurately planning and assigning an expert workforce, especially when multiple projects are underway simultaneously or overlap, which makes the required workforce more complex [

1,

4,

16,

17]. When there were differences between planned and actual demand for the expert workforce, shortages often occurred, affecting project timelines and outcomes [

1]. Project owners who use external expert workforce contractors must deal with additional delays, as it takes time to mobilize the expert workforce and ensure everyone is qualified [

4,

21]. To tackle these issues, this research presents a predictive and adaptive modeling methodology grounded in system dynamics that integrates quantifiable project risks and execution effectiveness variables into a feedback loop. This system enables organizations to dynamically predict the needs of their expert workers and make better decisions across multiple projects. This research also contributes to the broader sustainability discourse by linking human-capital planning to industrial resource efficiency. Sustainable projects management requires not only minimizing environmental and financial waste but also ensuring the long-term availability and effectiveness of expert personnel, a vital yet often neglected component of organizational sustainability.

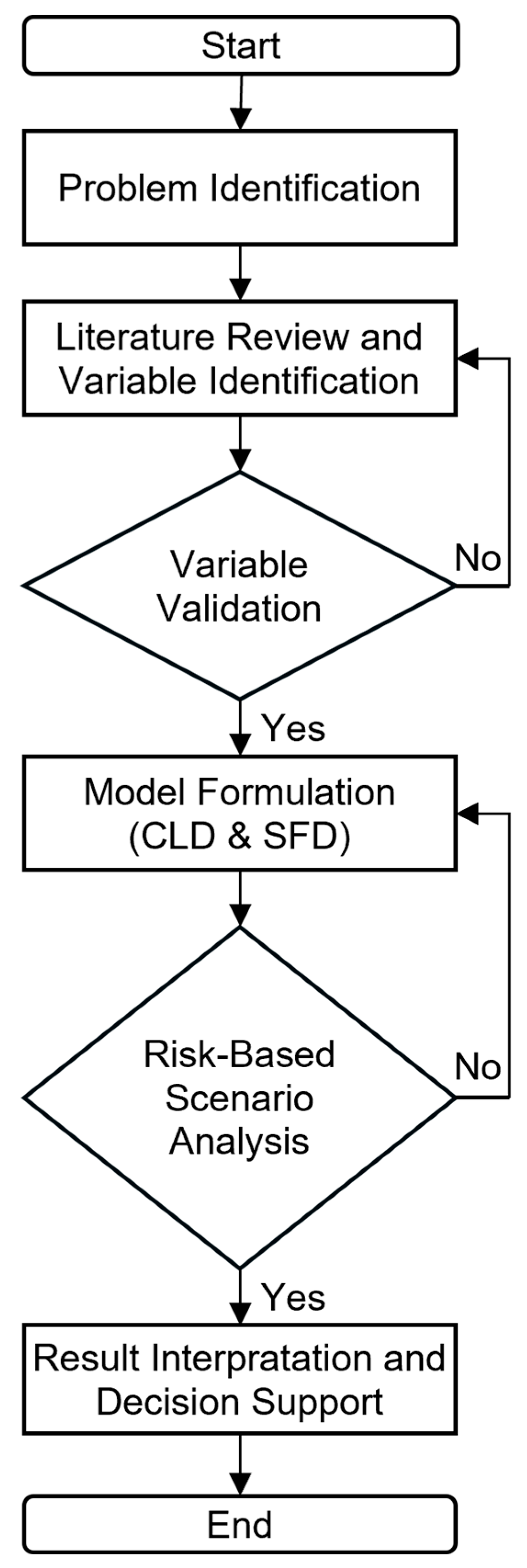

3. Methodology

The technique applied in this research combines literature analysis with a case study approach to address issues in multi-project management, specifically within the construction industry facility. This study identifies and validates critical variables affecting project execution by integrating qualitative and quantitative methodologies, particularly through the allocation of expert personnel in multi-project settings [

1,

4,

28]. Initially, a comprehensive literature review was conducted to identify relevant and valid variables from previous studies. These variables were thereafter examined through questionnaires distributed to experts and practitioners pertinent to the research focus. The verified variables highlighted the underlying study issues, which were further confirmed by field observations from different ongoing construction projects. Case studies were used throughout the project lifecycle to make sure it was viable and to validate both the conceptual and simulation models. A causal loop diagram (CLD) was created to examine how the variables are connected and how the system operates. Then, a stock-and-flow diagram (SFD) was constructed to show how the system's output changes over time. Ensure that it was appropriate. Model validation was performed across the phases. Validate the model's estimate of the required man-hours for the expert workforce using data from previous projects. The model was used for scenario-based risk analysis, which examined different inputs and provided the relevant outcome. It identified the most significant factors affecting the project's risk, and as a result, an expert workforce would be required.

These include resources, organizational structure, environmental factors, external factors, design, and technical obstacles [

6,

7]. The entire research method included a few interconnected steps: a comprehensive literature review, empirical testing of variables through questionnaires distributed to experts in the industrial facilities industry [

28], and ongoing enhancement of a dynamic system model. This approach was created to simulate and improve the allocation of expert personnel in environments with several projects. It provides a structured approach to efficiently deploy expert workforce resources [

28,

29,

32].

Figure 1 shows how to take a proactive approach to planning an expert workforce in complex multi-project settings to support the entire research process and its sequential stages.

When several projects are underway at the same time, a special method is needed to track how the need for expert workforce resources evolves over time, especially when it pertains to the risks encountered in project execution [

17,

33]. These risks may vary in intensity and effect over the course of the project, and they may coincide, affecting the overall demand for experts [

24,

25,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Systems dynamics is used to address these complex, continually evolving situations. This modeling technique enables determining and adapting the number of expert workers needed across multiple projects, which is beneficial for allocating them when risk profiles change [

1,

27,

28].

4. Result

This case study examines three chemical-process-based production facility projects in West Java, Indonesia. These facilities, commonly referred to as processing plants, have been executed during the project implementation phase, which includes planning, detailed engineering design, procurement, construction, and installation. The combined scope of work covers Projects A, B, and C, as shown in

Table 1, which outlines the overall effort required to complete each project from engineering to commissioning.

The expert workforce is responsible for performing the work during the planning and engineering phase, in accordance with the project owner's requirements and specifications. The group of experts works across many fields, including civil and architectural engineering, mechanical and piping engineering, electrical and instrumentation engineering, process control engineering, and project management [

20,

21]. During the procurement phase, the expert personnel are responsible for planning and acquiring materials and equipment for the production facility that complies with the project's design specifications. During construction and installation, the expert workforce is crucial to ensuring the work proceeds according to the plans developed during the engineering phase.

Table 2 shows the estimated man-hours of the expert workforce on the Engineering, Procurement, and Construction (EPC) phases. All the numbers are in man-hours.

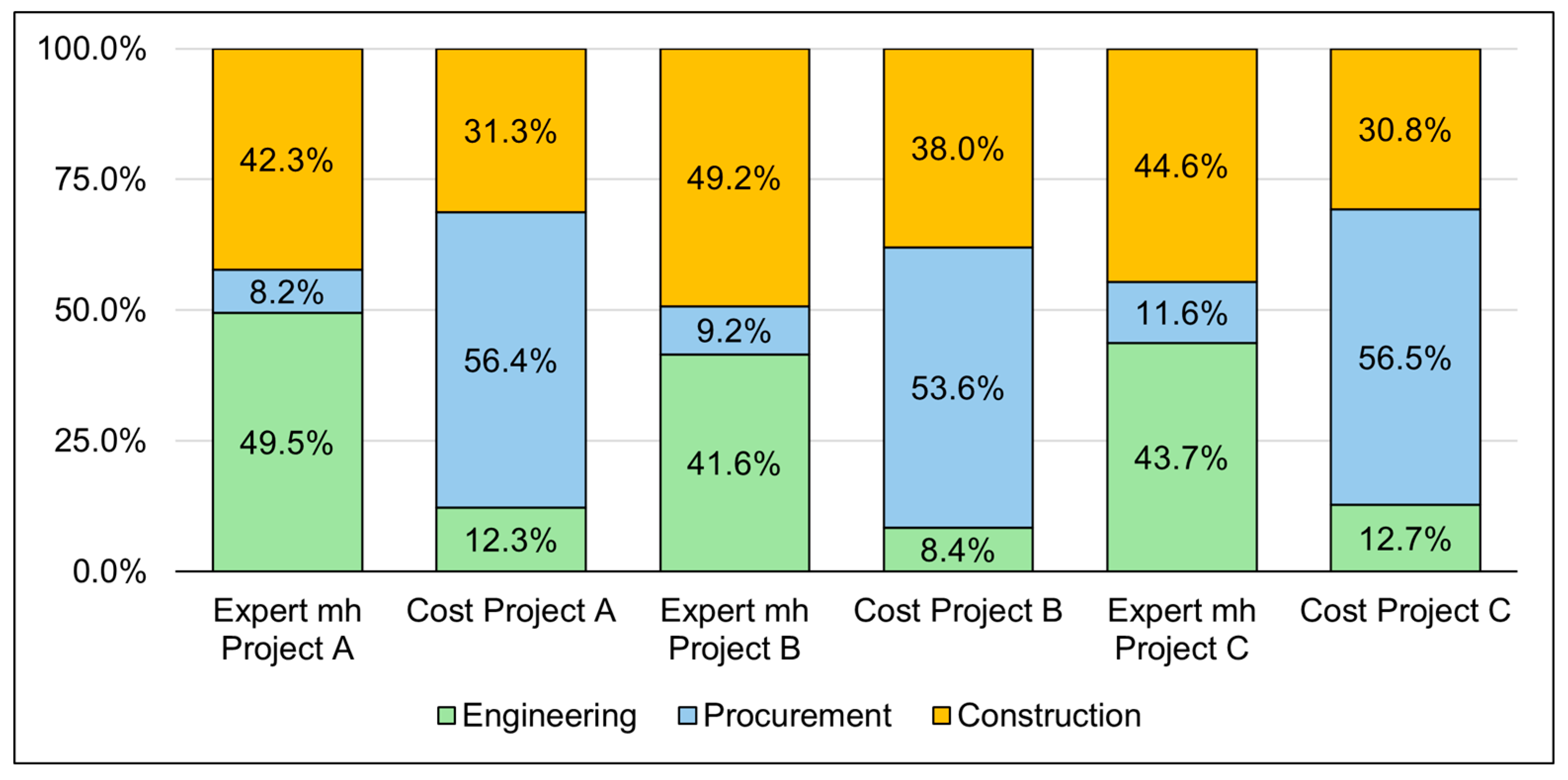

Figure 2 presents a histogram showing the relationship between the number of man-hours assigned to a project and the cost required to complete it. It also shows how the demand for an expert workforce is spread across different phases. The findings show that the engineering phase has the most demand for expert personnel across all projects. The phrase "expert mh" refers to the total number of expert man-hours, and "cost" refers to the project's total cost. Both numbers have been adjusted to 100%.

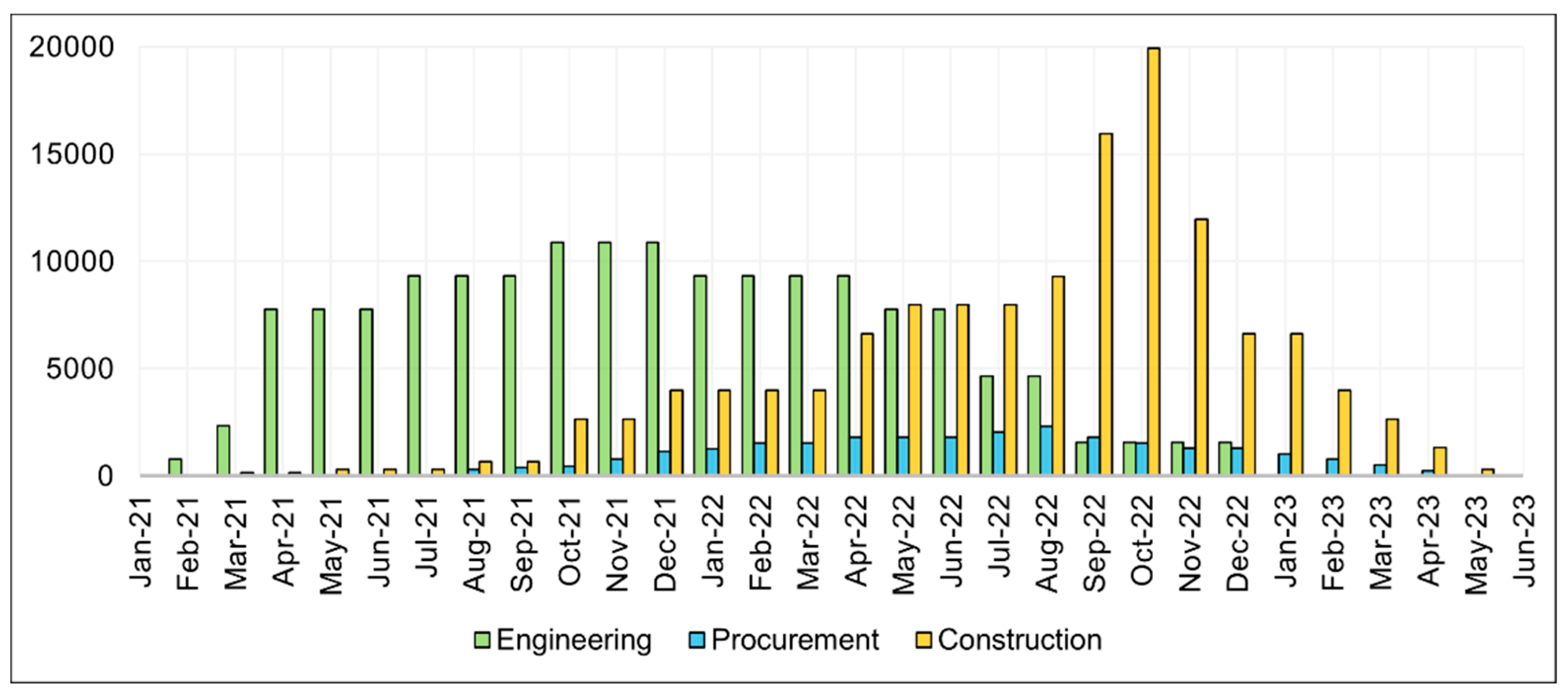

Each organizational unit assigned to a project is responsible for planning and providing its respective expert workforce man-hour loading, as illustrated in

Figure 3 for Project A. Within a multi-project management framework, the project owner supervises and coordinates the overall allocation of expert workforce man-hours across all ongoing projects.

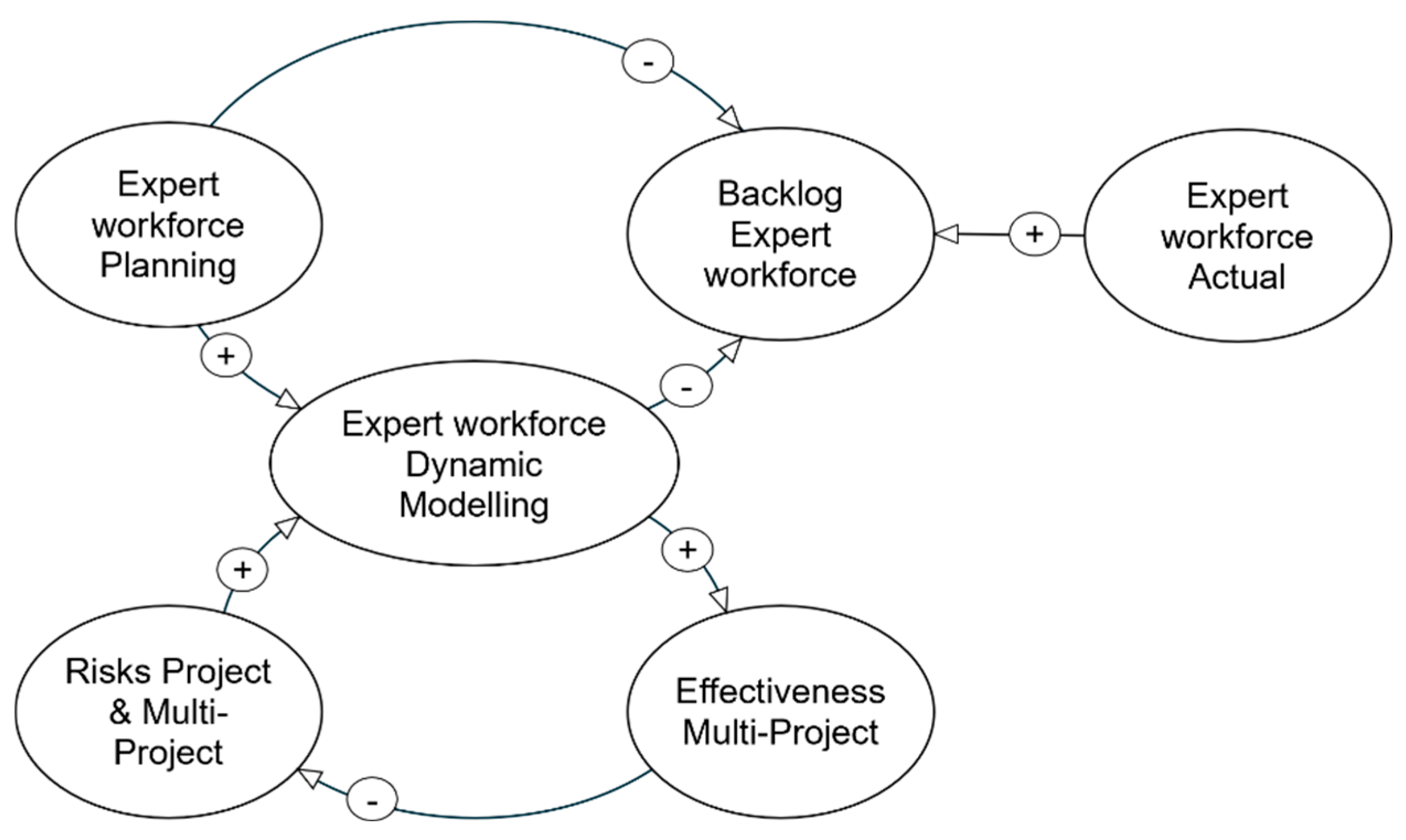

Risks affecting the demand for expert workers' hours emerge at both the project and multi-project levels. Modeling these demands at both levels improves the ability to identify potential expert shortages throughout project execution. Field observations and literature reviews were conducted to identify relevant risk variables and evaluate the effectiveness of multi-project implementation. These variables were then validated statistically based on feedback from construction professionals.

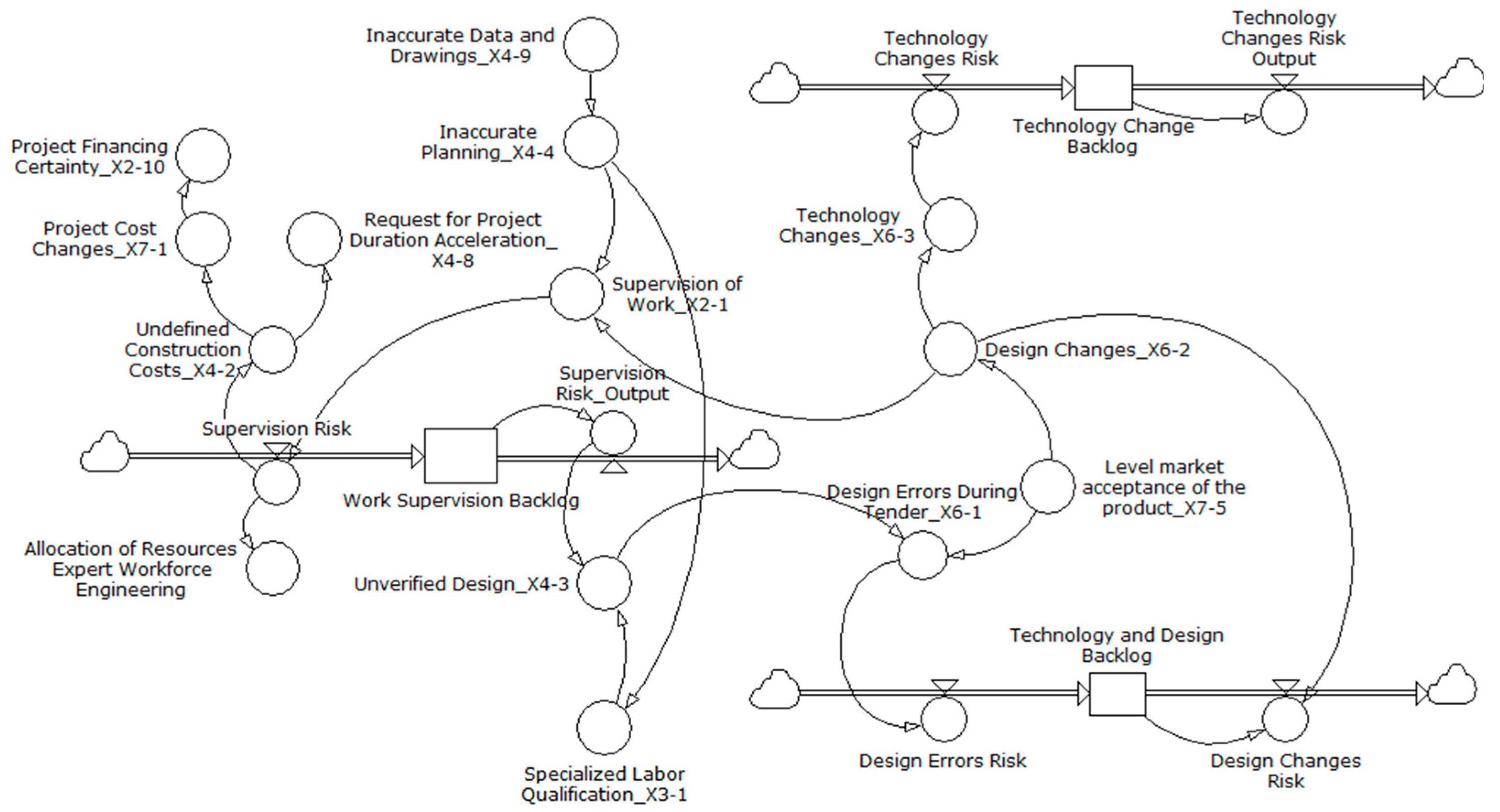

Figure 4 presents a simplified Causal Loop Diagram (CLD) that illustrates the interrelationships among expert workforce man-hour demand, multi-project effectiveness, and project-level and multi-project risks.

Table 3 lists the main risk variables that affect expert workforce man-hour allocation, particularly during engineering-related activities. Risk index values quantify factors such as the degree of supervision and adoption of new technologies; higher scores indicate greater effects on the number of man-hours required. The level of supervision is a crucial factor that directly affects the additional man-hours needed to mitigate project risks.

Figure 5 depicts the Stock and Flow Diagram (SFD), demonstrating the impact of accumulated risks on the distribution of expert workforce man-hours in engineering operations. By capturing the cumulative effect of engineering-related risks through reinforcing feedback loops, key variables such as supervision levels and technology changes dramatically increase the demand for an expert workforce.

Besides engineering-related risks, the quality of contractor performance could impact the allocation of expert workforce man-hours. Factors, including environmental conditions, changes in labor regulations, and delays in contractor payments, are incorporated into a risk index that measures the possible escalation in necessary man-hours. A higher score signifies a bigger potential impact, especially in multi-project contexts where stakeholder collaboration is essential. The engineering-phase model accurately delineates the effect of accumulated risks on the allocation of expert personnel through supervision levels, technological changes, and feedback loops. The analytical methodology utilized here can be extended to both the procurement and construction phases, adopting the same modeling principles.

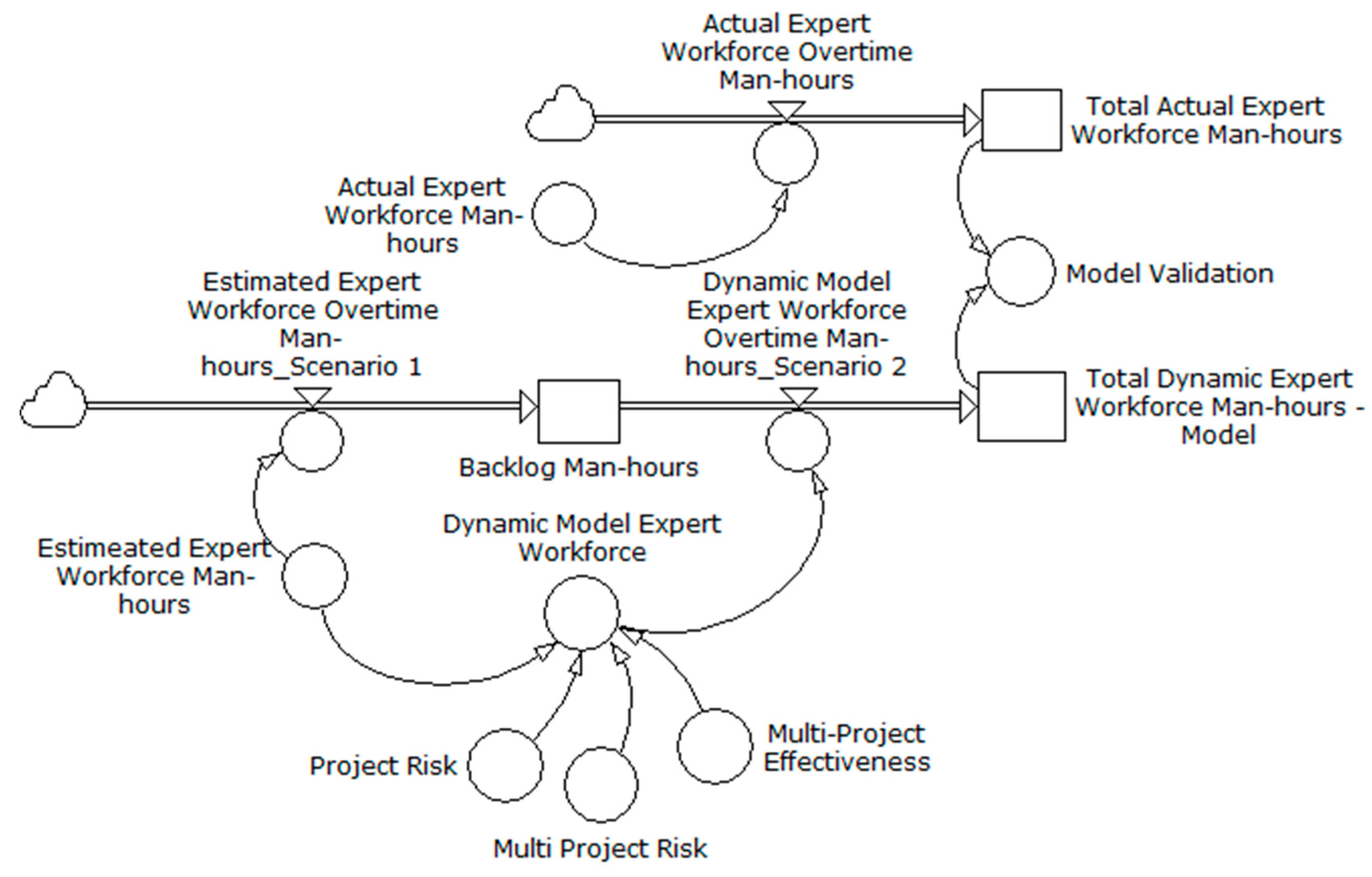

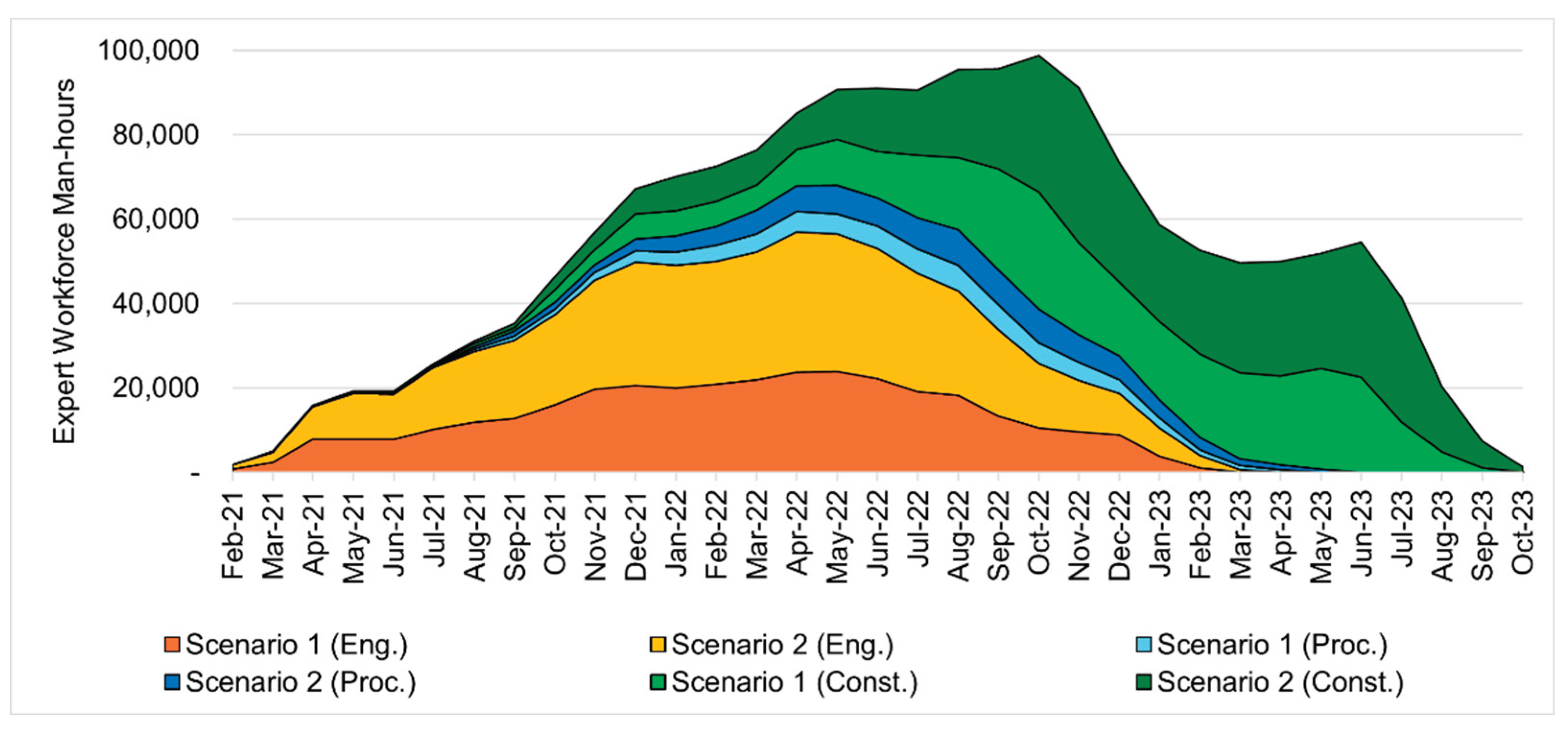

The dynamic model reveals that quality and coordination risks significantly influence workforce requirements through rework and process inefficiencies. Higher rework and coordination risks increase the additional workforce demand needed to manage inter-project interactions and stakeholder alignment. In contrast, effective multi-project coordination improves allocation efficiency by minimizing process losses. A dynamic system model was developed to determine the optimal allocation of expert man-hours during the engineering phase. The model consists of two simulated scenarios, as shown in

Figure 6. Scenario 1, the estimated expert workforce assumes a static allocation model, in which expert resources are immediately available from the market whenever shortages occur. This reflects a simplified assumption that an expert workforce can be mobilized on demand, leading to minimal change in the overall workforce profile over time.

Scenario 2, on the contrary, employs a dynamic modeling technique that leverages the quantifiable risk and effectiveness variables created in this study. As risks arise and effective values evolve, the needs of the expert workforce change throughout the project. As a result, the entire allocation of experts to the workforce expands over time, including changes that may not be obvious when employing solely an estimated expert workforce without dynamic modeling. In the real world, when there are insufficient workers, it might affect the timing, scope, quality, and cost of a project. It also combines multi-project maturity by continually changing workforce demands based on feedback on risk and effectiveness.

The simulation integrates the three-phase categories—Engineering (E), Procurement (P), and Construction (C)—within this EPC framework to reflect how functional risks influence man-hour requirements across the phases, resulting in a distinct quantitative impact distributed throughout the EPC process distributed throughout the EPC process, with standard deviation and time-delay parameters.

Table 4 summarizes these parameters applied to the simulation scenarios.

The simulation results reflect real-world conditions by integrating quantified risk and effectiveness factors as mitigation inputs to estimate expert workforce man-hour requirements.

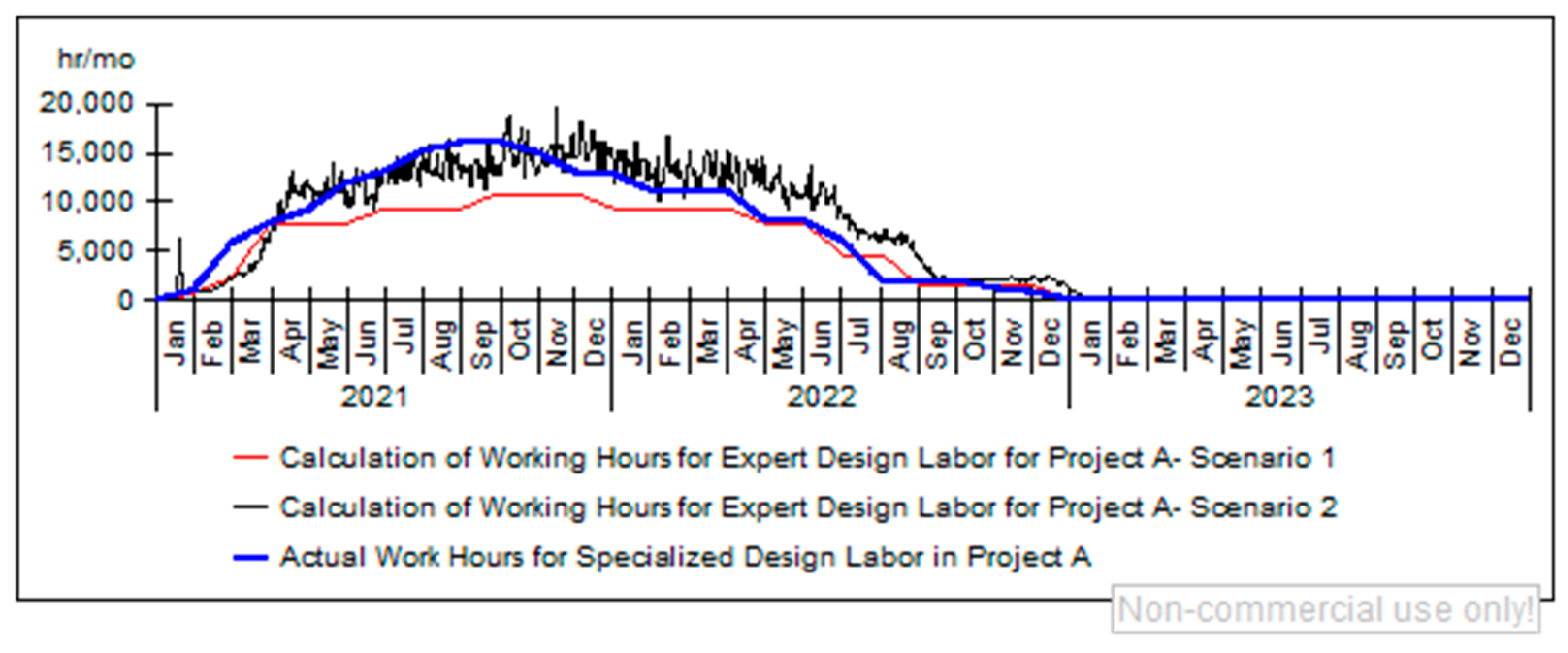

Figure 7 illustrates how this method compares real project data with the expert workforce need over time for both situations. Scenario 2 incorporates additional man-hours as risks change and effectiveness of the multi-project, however, Scenario 1 projects workforce demands without accounting for effectiveness or risk. The third curve in

Figure 7 shows actual data from Project A (2021–2023), validating the simulation results.

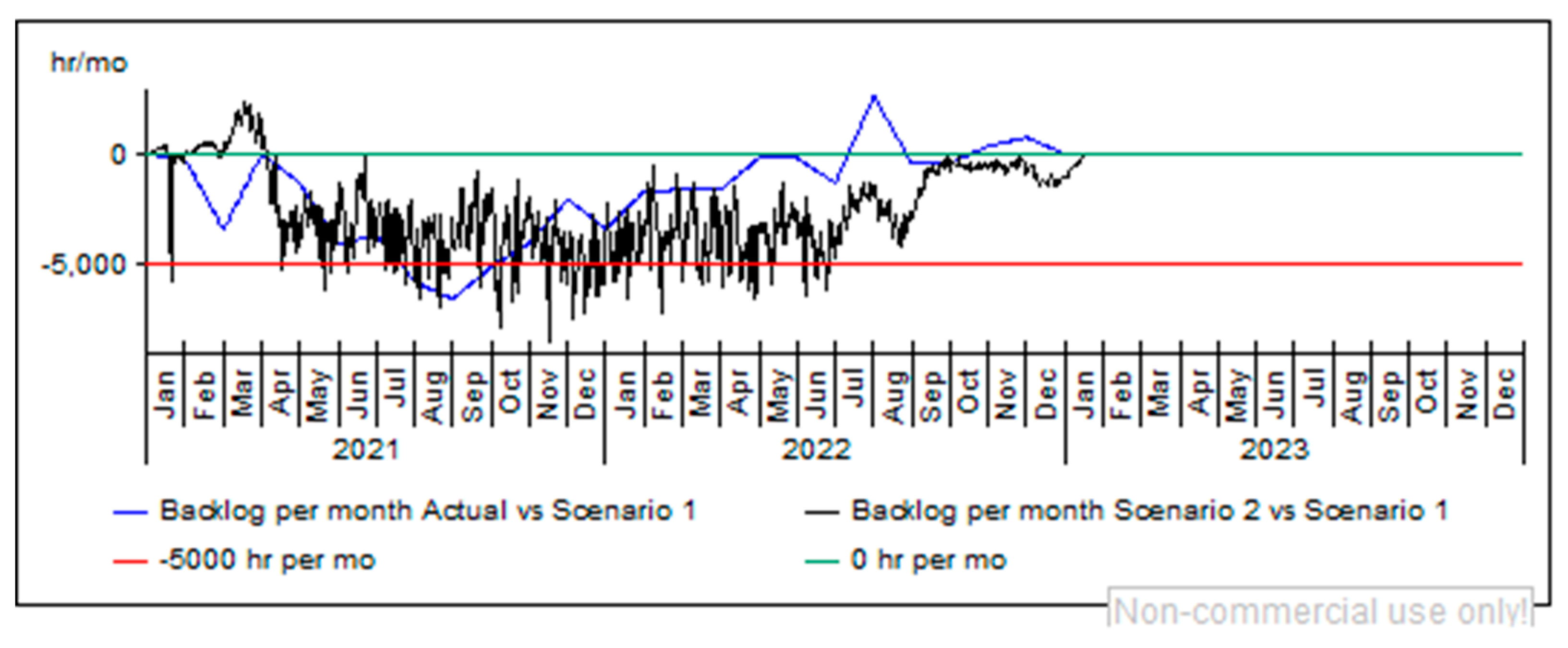

The simulation results, shown in

Figure 8, illustrate the deviation among the three data sets. Two comparisons are made: first, between Scenario 1 and the actual expert workforce man-hour demand, and second, between Scenarios 1 and 2. The results confirm that Scenario 2 provides a close approximation to real-world conditions, serving as a reliable method for simulation-based prediction of expert workforce requirements.

Model validation was performed by comparing simulation outputs with actual historical data. As summarized in

Table 5, the Scenario 2 simulation accurately predicts expert workforce demand in engineering activities over time, incorporating both risk and effectiveness factors from 2021 to 2023. Further detailed validation for procurement and construction phases, following the same modeling approach, is provided in the

Supplementary Materials.

Following Barlas [

32], two validation criteria were applied. First, the model's average monthly allocation of expert workforce man-hours was compared with the actual values, and the model was considered valid when the deviation was within ±5%. Second, data variation was assessed by comparing the standard deviation of simulated and actual allocations; deviations within ±30% were considered valid.

The validation results confirm that the Scenario 2 model is valid and consistent with actual project data, effectively supporting the entire man-hour estimation for the expert workforce as part of the overall risk-mitigation and effectiveness strategy in multi-project environments. The validation structure refers to Barlas' multiple-test framework to ensure both pattern and amplitude validity.

Table 6 presents the results of the average error (<±5%) and amplitude error (<±30%) tests for Projects A, B, and C, demonstrating that the model's behavior closely aligns with actual expert workforce utilization across the engineering, procurement, and construction phases.

The Scenario 2 results also indicate that expert workforce man-hours are required across the engineering, procurement, and construction phases.

Figure 9 shows this relationship, showing the expert workforce man-hours required for both scenarios. Scenario 2 enables accurate estimation of the number and qualification level of experts needed, directly supporting risk mitigation and improving overall execution effectiveness. From a broader perspective, this model enables project owners to plan resource allocation proactively while accounting for risk and performance factors. The proposed model contributes to sustainable industrial operations by ensuring optimal allocation of scarce expert resources, minimizing backlog accumulation, and reducing the need for reactive staffing. This strengthens long-term workforce sustainability and supports more resilient project execution environments.

In multi-project settings, the dynamic modeling technique offers a valuable and thorough framework for evaluating risks and effectiveness and enabling the proactive, data-driven distribution of expert workforce resources.

5. Conclusions

This study emphasizes the importance of risk-based expert workforce allocation for multi-project management. A dynamic model that integrates risk analysis into the allocation process was developed to adjust workforce requirements in real time. Emerging risks, including poor supervision, rework, and differences in project management effectiveness, cause expert demand to shift across concurrent or overlapping projects. By precisely predicting and modifying allocations based on detected risk variables, the suggested methodology reduces the risk of expert workforce shortages that could interfere with project delivery. It also corrects the distribution of the expert workforce from the standpoint of multi-project execution effectiveness.

A system dynamics approach was employed to model expert workforce requirements across the design, procurement, and construction phases. This approach enables predicting and adjusting workforce needs in response to evolving risks and changing project conditions. In multi-project environments—where concurrent execution is common—timely and accurate workforce planning remains a significant challenge. Critical risk factors, such as supervision quality, design changes, and external influences, substantially affect workforce demand. The model was validated using real project data, demonstrating that a risk-based allocation strategy can minimize delays and enhance overall execution efficiency.

This study further highlights the significance of standardized management techniques in multi-project settings, including transparency of information, availability of resources, and project managers' proficiency. The suggested approach anticipates future expert workforce shortages and dynamically adjusts allocations in response to new risks that arise during implementation. Real-world data validation confirmed that workforce planning that accounts for risk variables greatly enhances project outcomes. Therefore, by providing a systematic framework to reduce risks and improve execution effectiveness in multi-project, cross-industry situations, this study adds real value to construction activities in the industrial sector.

Although this research focuses primarily on industrial facility construction, particularly new or greenfield projects, its applicability extends beyond these contexts. The model can be adapted to brownfield projects by incorporating more complex risk factors and varying levels of implementation effectiveness influenced by site-specific conditions, regional dynamics, project types, and ownership structures. Future research should further examine the allocation of the skilled workforce in scenarios in which project owners contract directly with implementing contractors. In industrial construction projects, synergy between experts and skilled workers is critical to achieving efficient, effective task execution. These two workforce groups play complementary roles in maintaining quality and meeting project timelines. Therefore, applying risk-based workforce allocation models for both expert and skilled workforces is essential for achieving optimal project outcomes.