Submitted:

18 November 2025

Posted:

19 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

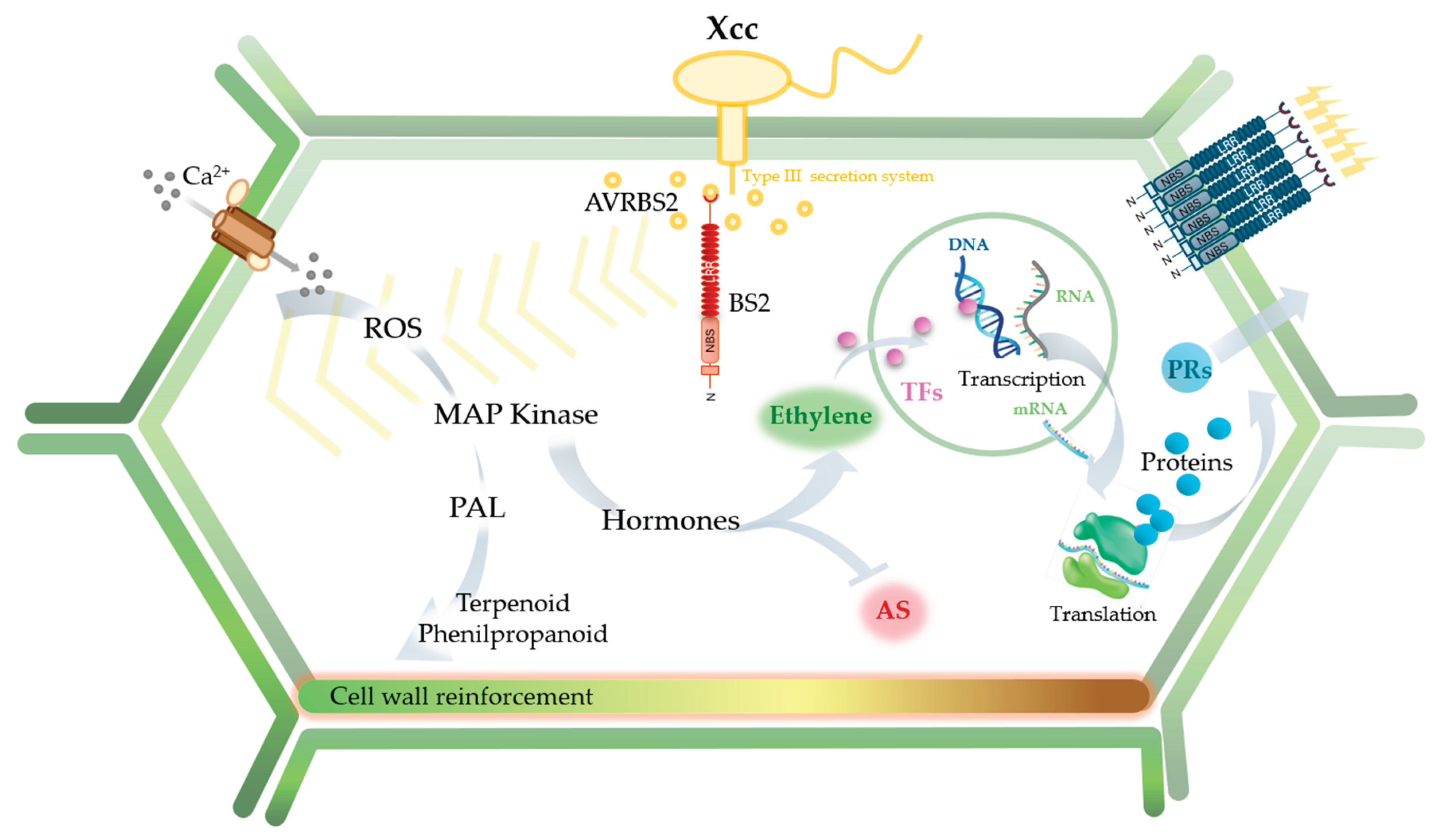

The pepper Bs2 resistance gene confers resistance to susceptible Solanaceae plants against pathogenic strains of Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria carrying the avrBs2 avirulence gene. Previously, we generated Bs2-transgenic Citrus sinensis plants that exhibited enhanced resistance to citrus canker caused by Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri (Xcc), although the underlying mechanisms remained unknown. To elucidate the molecular basis of the early defense response, we performed a comparative transcriptomic analysis of Bs2-expressing and non-transgenic plants 48 hours after Xcc inoculation. A total of 2,022 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified, including 1,356 up-regulated and 666 down-regulated genes. In Bs2-plants, 36.8% of the up-regulated DEGs were associated with defense responses and biotic stress. Functional annotation revealed major changes in genes encoding receptor-like kinases, transcription factors, hormone biosynthesis enzymes, pathogenesis-related proteins, secondary metabolism, and cell wall modification. Among hormone-related pathways, genes linked to ethylene biosynthesis and signaling were the most strongly regulated. Consistently, endogenous ethylene levels increased in Bs2-plants following Xcc infection, and treatment with an ethylene-releasing compound enhanced resistance in non-transgenic plants. Overall, our results indicate the Bs2 expression activates a complex defense network in citrus and may represent a valuable strategy for controlling canker and other Xanthomonas-induced diseases.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

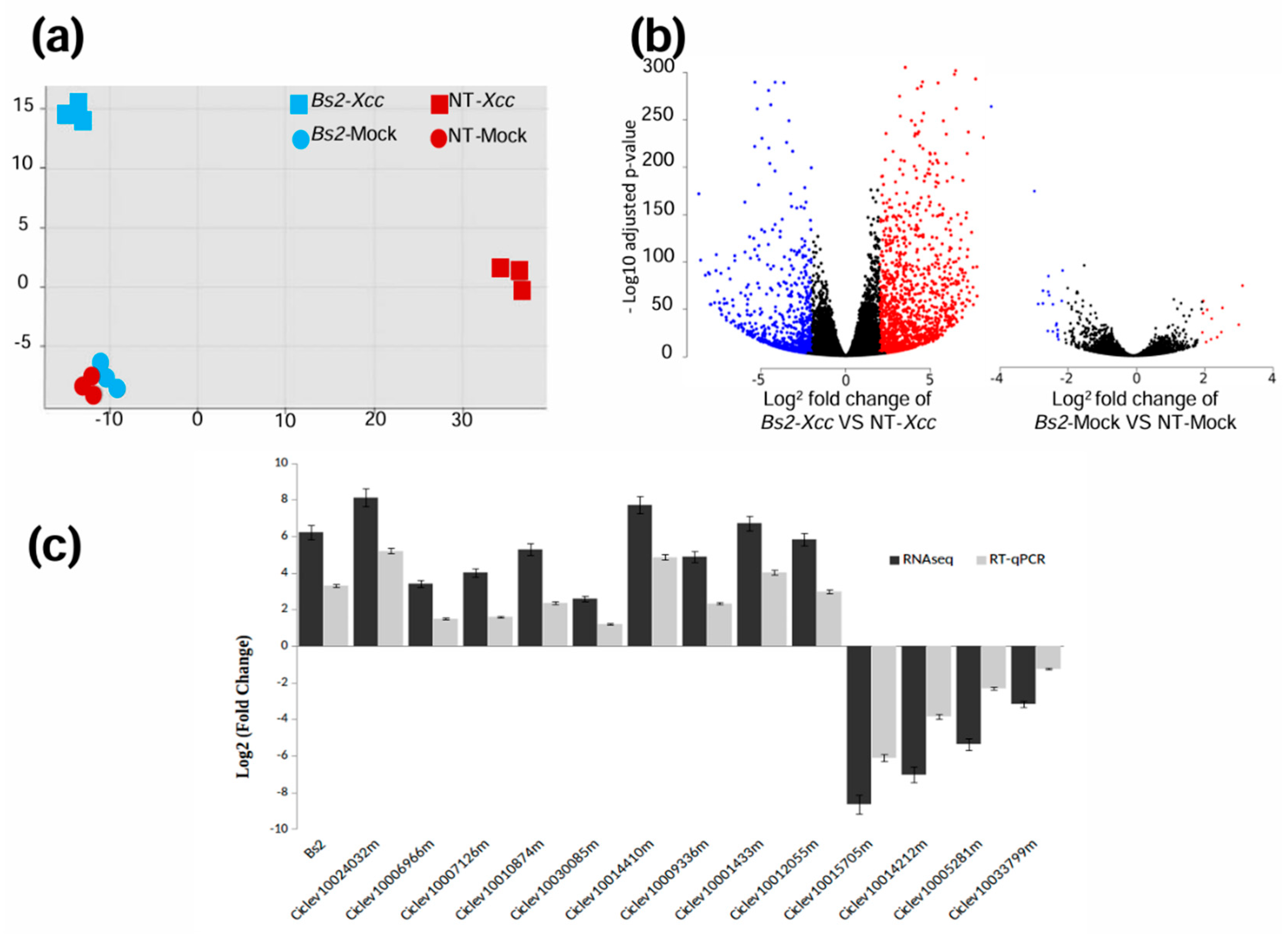

3.1. Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs) in Citrus Sinensis Bs2-Plants

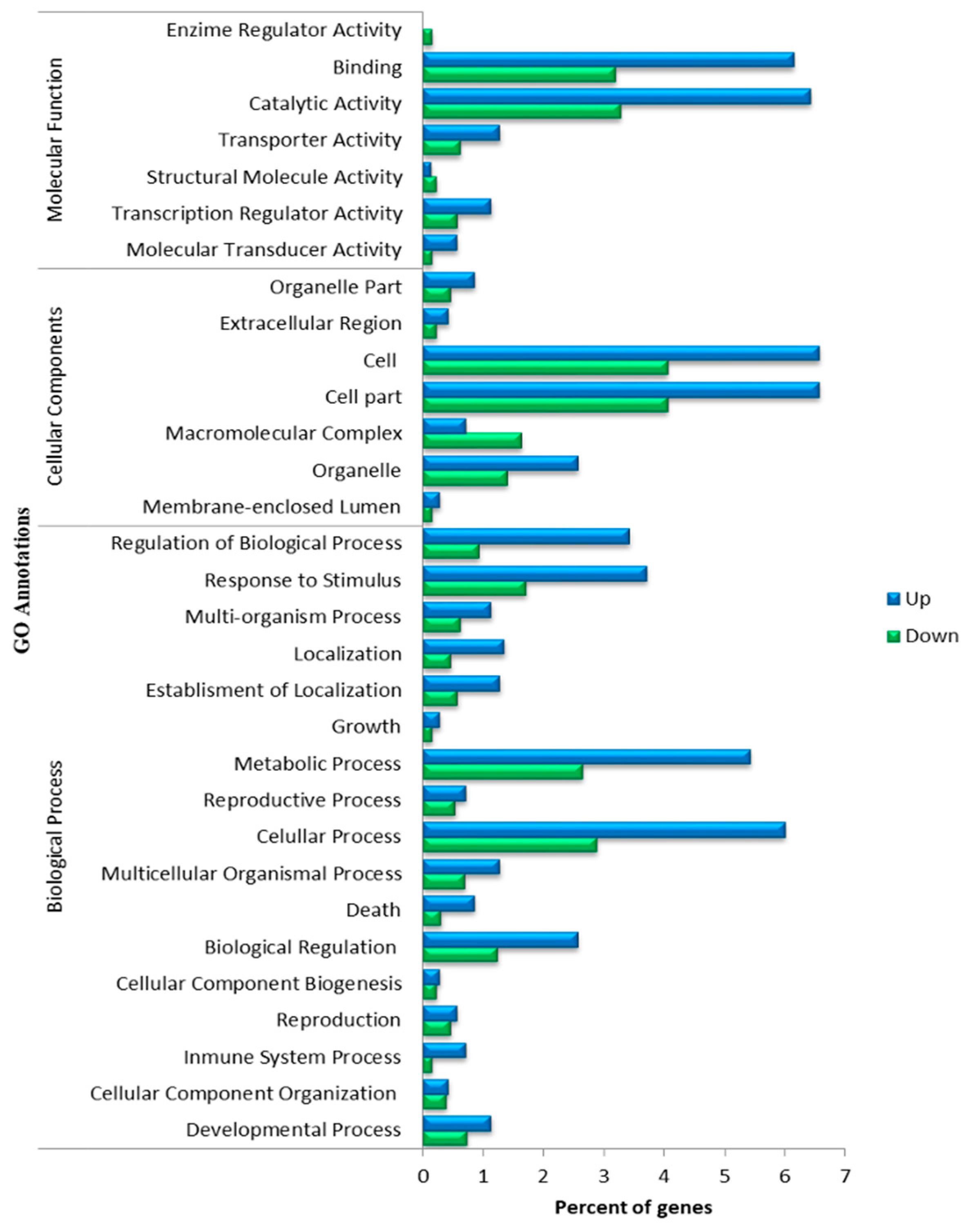

3.2. Functional Analysis of DEGs

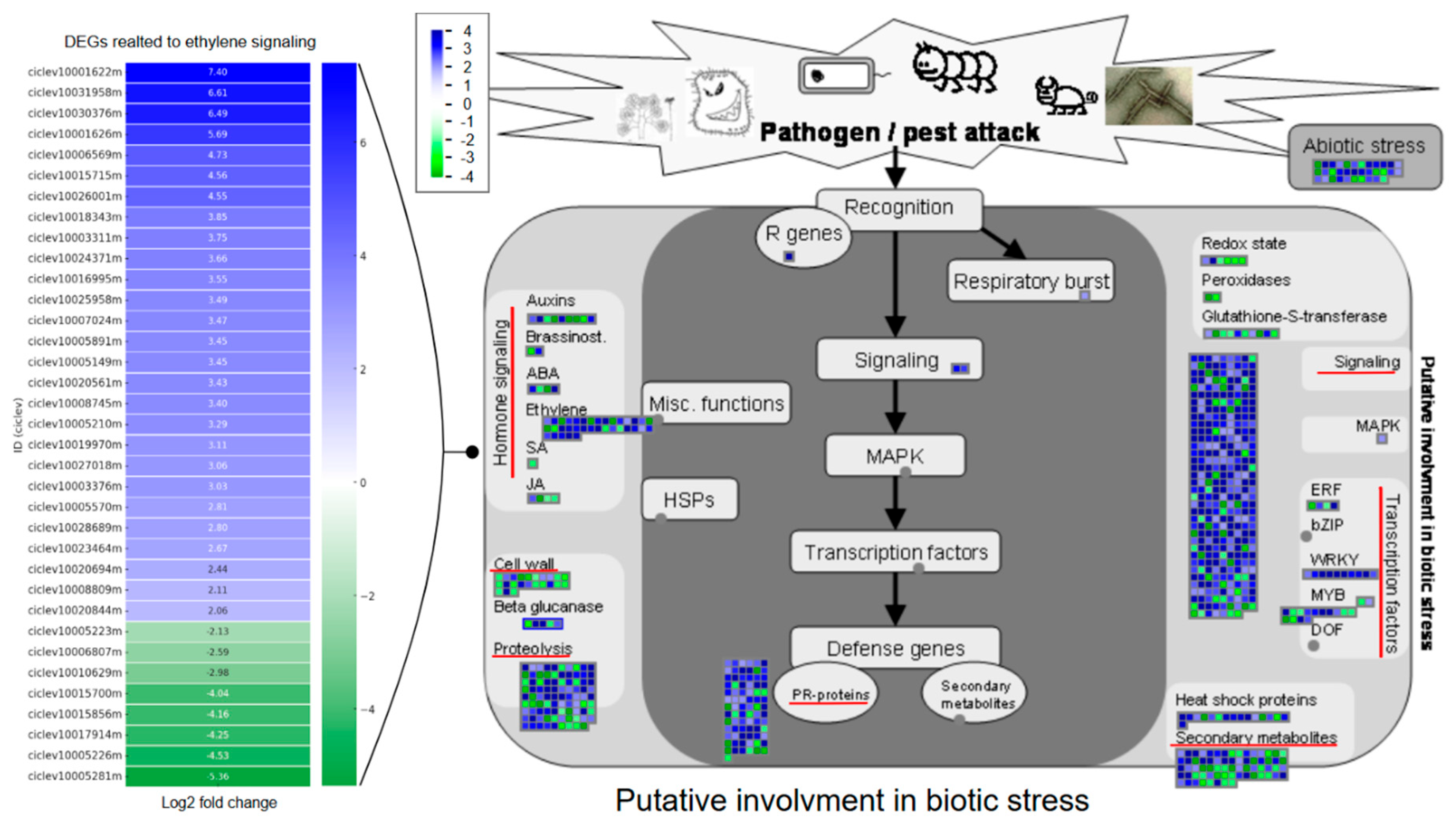

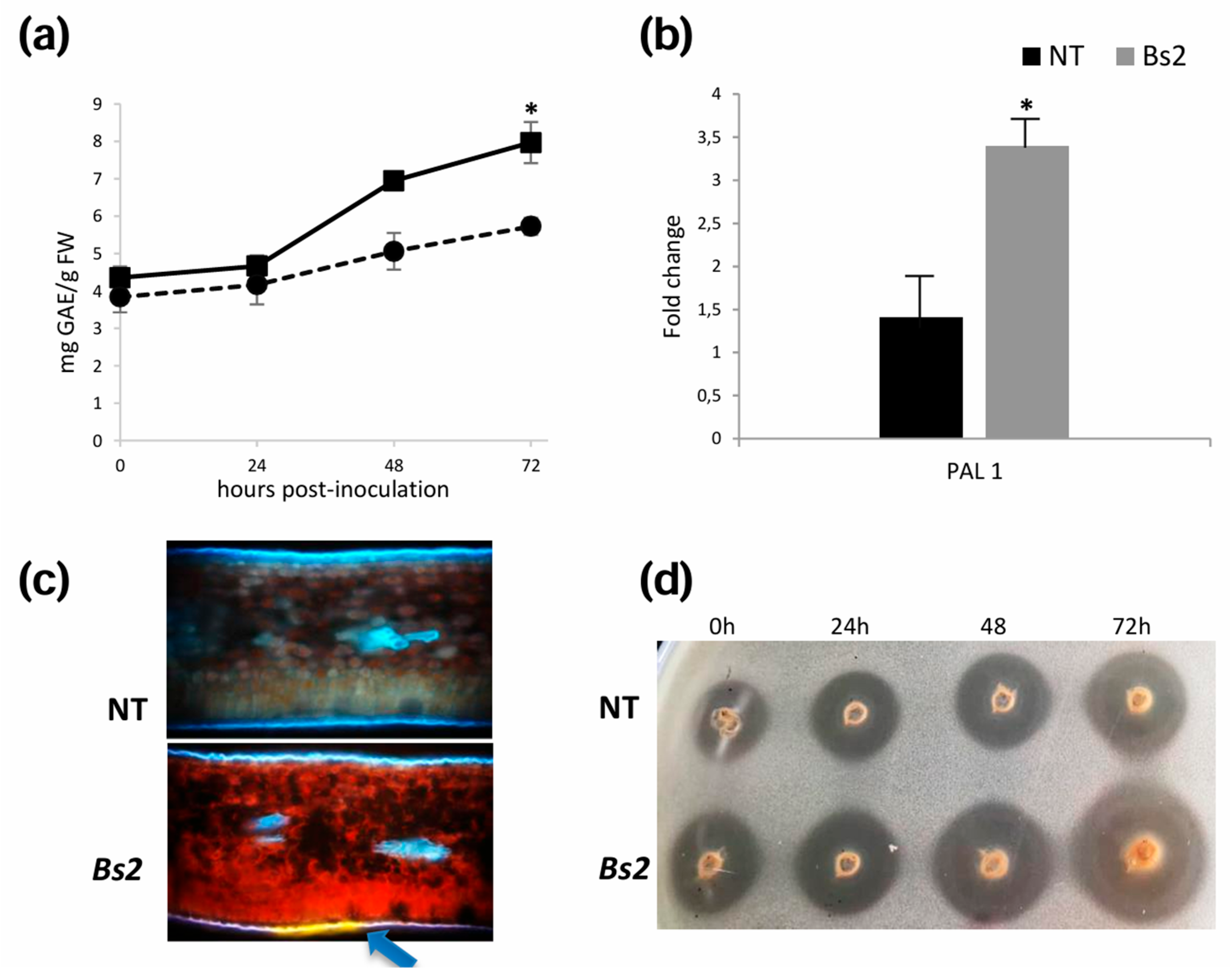

3.3. Plant Defense Is Induced in Bs2-Plants After Xcc Inoculation

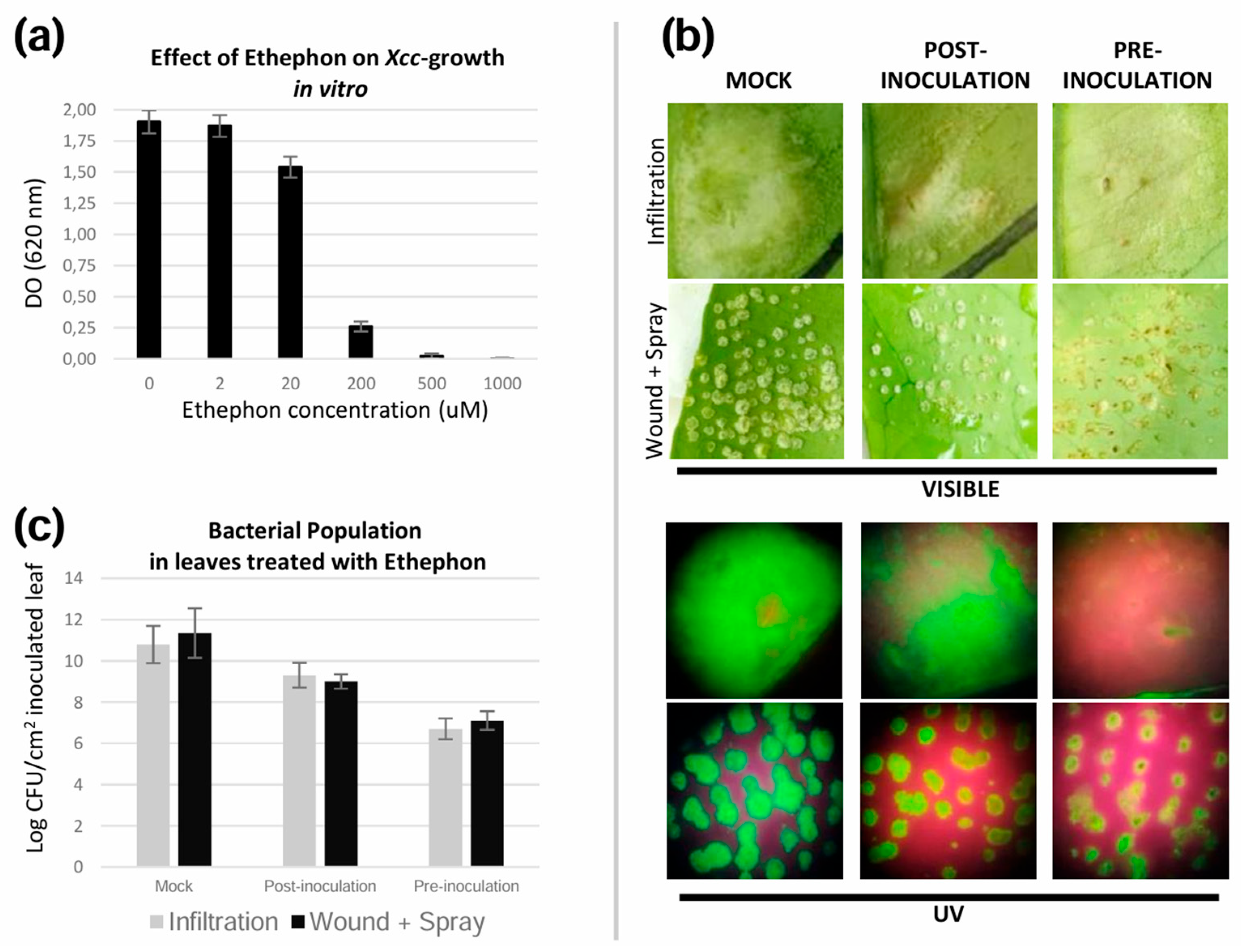

3.4. Bs2 Induces Major Regulation of the Ethylene Pathway

3.5. Changes in Secondary Metabolic Pathways and Cell Wall

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| avrBs2 | avrBs2 avirulence gene |

| Bs2 | Bs2 resistance gene from Capsicum annuum |

| Bs2-plants | Transgenic plants carrying the Bs2 gene |

| Ca²⁺ | Calcium ion |

| CFU | Colony Forming Units |

| CHS1 | Chalcone Synthase 1 |

| CRKs | Cysteine-Rich Receptor-Like Kinases |

| CT / Ct | Cycle Threshold (ΔΔCt method) |

| DEGs | Differentially Expressed Genes |

| DESeq2 | Differential expression analysis package |

| dpi | Days Post-Inoculation |

| DUF26 | Domain of Unknown Function 26 |

| ERFs | Ethylene-Responsive Factors |

| EREBPs | Ethylene-Responsive Element Binding Proteins |

| ET | Ethylene |

| ETI | Effector-Triggered Immunity |

| FDR | False Discovery Rate |

| FPKM | Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads |

| FW | Fresh Weight |

| GAE | Gallic Acid Equivalents |

| GFP | Green Fluorescent Protein |

| GO | Gene Ontology |

| HLB | Huanglongbing |

| hpi | Hours Post-Inoculation |

| HR | Hypersensitive Response |

| ICBR | Interdisciplinary Center for Biotechnology Research |

| IDT | Integrated DNA Technologies |

| JA | Jasmonic Acid |

| LRR | Leucine-Rich Repeat |

| LRR-RLK | Leucine-Rich Repeat Receptor-Like Kinase |

| MAPK / MAPKs | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase(s) |

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| MgCl₂ | Magnesium Chloride |

| NBS-LRR | Nucleotide-Binding Site – Leucine-Rich Repeat |

| NPR1 | Nonexpressor of Pathogenesis-Related Genes 1 |

| NT | Non-Transgenic |

| OD600 | Optical Density at 600 nm |

| PAL | Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase |

| PAL1 | Phenylalanine Ammonia-Lyase 1 |

| PAMPs | Pathogen-Associated Molecular Patterns |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PCC | Phenolic Compound Content |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PR | Pathogenesis-Related |

| PYM | Peptone–Yeast–Malt Extract Medium |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| R | Resistance |

| RLKs | Receptor-Like Kinases |

| RNA-seq | RNA sequencing |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| rpm | Revolutions Per Minute |

| SA | Salicylic Acid |

| SAR | Systemic Acquired Resistance |

| SAUR | Small Auxin Up RNA |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SRG1 | Senescence-Related Gene 1 |

| TFs | Transcription Factors |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| WAKs | Wall-Associated Kinases |

| Xaa | Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. Aurantifolii |

| Xcc | Xanthomonas citri pv. Citri |

| Xcm | Xanthomonas campestris pv. Musacearum |

| Xcv | Xanthomonas campestris pv. vesicatoria |

References

- Ali, S.; Hameed, A.; Muhae-Ud-Din, G.; Ikhlaq, M.; Ashfaq, M.; Atiq, M.; Ali, F.; Zia, Z.U.; Naqvi, S.A.H.; Wang, Y. Citrus Canker: A Persistent Threat to the Worldwide Citrus Industry—An Analysis. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behlau, F. An Overview of Citrus Canker in Brazil. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2021, 46, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Niu, Y.; He, B.; Ma, L.; Li, G.; Tran, V.-T.; Zeng, B.; Hu, Z. A Dual Selection Marker Transformation System Using Agrobacterium tumefaciens for the Industrial Aspergillus oryzae 3.042. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 29, 230–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stover, E.; Stange, R.R.; McCollum, T.G.; Jaynes, J.; Irey, M.; Mirkov, E. Screening Antimicrobial Peptides In Vitro for Use in Developing Transgenic Citrus Resistant to Huanglongbing and Citrus Canker. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2013, 138, 142–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, N.; Kobayashi, K.; Zanek, M.C.; Calcagno, J.; García, M.L.; Mentaberry, A. Transgenic Sweet Orange Plants Expressing a Dermaseptin Coding Sequence Show Reduced Symptoms of Citrus Canker Disease. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 167, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conti, G.; Gardella, V.; Vandecaveye, M.A.; Gómez, C.A.; Joris, G.; et al. Transgenic Citrange troyer Rootstocks Overexpressing Antimicrobial Potato Snakin-1 Show Reduced Citrus Canker Symptoms. J. Biotechnol. 2020, 324, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Francis, M.I.; Dawson, W.O.; Graham, J.H.; Orbović, V.; Triplett, E.W.; Zhonglin, M. Over-Expression of the Arabidopsis NPR1 Gene in Citrus Increases Resistance to Citrus Canker. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2010, 128, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.-Z.; Liu, J.-H. Transcriptional Profiling of Canker-Resistant Transgenic Sweet Orange Constitutively Overexpressing a Spermidine Synthase Gene. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 918136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, G.; Pitino, M.; Duan, Y.; Stover, E. Reduced Susceptibility to Xanthomonas citri in Transgenic Citrus Expressing the FLS2 Receptor from Nicotiana benthamiana. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2016, 29, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Xuan, X.; Wenwu, G. Production of Transgenic ‘Anliucheng’ Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis Osbeck) with Xa21 Gene for Potential Canker Resistance. J. Integr. Agric. 2014, 13, 2370–2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendín, L.N.; Orce, I.G.; Gómez, R.L.; Enrique, R.; Grellet Bournonville, C.F.; Noguera, A.S.; Vojnov, A.A.; Marano, M.R.; Castagnaro, A.P.; Filippone, M.P. Inducible Expression of Bs2 R Gene from Capsicum chacoense in Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis L. Osbeck) Confers Enhanced Resistance to Citrus Canker Disease. Plant Mol. Biol. 2017, 93, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marone, D.; Russo, M.A.; Laidò, G.; De Leonardis, A.M.; Mastrangelo, A.M. Plant Nucleotide Binding Site–Leucine-Rich Repeat (NBS-LRR) Genes: Active Guardians in Host Defense Responses. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 7302–7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, J.N.; Lorenzen, J.; Bahar, O.; Ronald, P.; Tripathi, L. Transgenic Expression of the Rice Xa21 Pattern-Recognition Receptor in Banana Confers Resistance to Xanthomonas campestris pv. musacearum. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2014, 12, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Lin, X.; Poland, J.; Trick, H.; Leach, J.; Hulbert, S. A Maize Resistance Gene Functions against Bacterial Streak Disease in Rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2005, 102, 15383–15388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, T.H.; Dahlbeck, D.; Clark, E.T.; Gajiwala, P.; Pasion, R.; Whalen, M.C.; Stall, R.E.; Staskawicz, B.J. Expression of the Bs2 Pepper Gene Confers Resistance to Bacterial Spot Disease in Tomato. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 14153–14158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sendín, L.; Filippone, M.; Orce, I.; Rigano, L.; Enrique, R.; Peña, L.; Vojnov, A.; Marano, M.; Castagnaro, A. Transient Expression of Pepper Bs2 Gene in Citrus limon as an Approach to Evaluate Its Utility for Management of Citrus Canker Disease. Plant Pathol. 2012, 61, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigano, L.A.; Siciliano, F.; Enrique, R.; Sendín, L.; Filippone, P.; Torres, P.S.; Qüesta, J.; Dow, J.M.; Castagnaro, A.P.; Vojnov, A.A. Biofilm Formation, Epiphytic Fitness, and Canker Development in Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007, 20, 1222–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siciliano, F.; Torres, P.; Sendín, L.; Bermejo, C.; Filippone, P.; Vellice, G.; Ramallo, J.; Castagnaro, A.; Vojnov, A.; Marano, M.R. Analysis of the Molecular Basis of Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri Pathogenesis in Citrus limon. Electron. J. Biotechnol. 2006, 9, 0–0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaisson, M.J.; Tesler, G. Mapping Single-Molecule Sequencing Reads Using Basic Local Alignment with Successive Refinement (BLASR): Application and Theory. BMC Bioinform. 2012, 13, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trapnell, C.; Roberts, A.; Goff, L.; Pertea, G.; Kim, D.; Kelley, D.R.; Pimentel, H.; Salzberg, S.L.; Rinn, J.L.; Pachter, L. Differential Gene and Transcript Expression Analysis of RNA-Seq Experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 2012, 7, 562–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-Seq Data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Z.; Zhou, X.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Su, Z. agriGO: A GO Analysis Toolkit for the Agricultural Community. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, W64–W70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thimm, O.; Bläsing, O.; Gibon, Y.; Nagel, A.; Meyer, S.; Krüger, P.; Selbig, J.; Müller, L.A.; Rhee, S.Y.; Stitt, M. MAPMAN: A User-Driven Tool to Display Genomics Data Sets onto Diagrams of Metabolic Pathways and Other Biological Processes. Plant J. 2004, 37, 914–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Hu, C.; Li, N.; Zhang, J.; Yan, J.; Deng, Z. Transformation of Sweet Orange [Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck] with pthA-nls for Acquiring Resistance to Citrus Canker Disease. Plant Mol. Biol. 2011, 75, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing Real-Time PCR Data by the Comparative CT Method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Long, X.; Zhao, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Song, M.; Ma, S.; Jing, Y.; Wang, S.; He, Y.; Esteban, C.R. A Single-Cell Transcriptomic Atlas of Human Skin Aging. Dev. Cell 2021, 56, 383–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, K.J.; Watkins, C.B.; Pritts, M.P.; Liu, R.H. Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Activities of Strawberries. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6887–6892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohorn, B.D.; Kohorn, S.L. The Cell Wall-Associated Kinases, WAKs, as Pectin Receptors. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campe, R.; Langenbach, C.; Leissing, F.; Popescu, G.V.; Popescu, S.C.; Goellner, K.; Beckers, G.J.; Conrath, U. ABC Transporter PEN3/PDR8/ABCG36 Interacts with Calmodulin, Which, Like PEN3, Is Required for Arabidopsis Nonhost Resistance. New Phytol. 2016, 209, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durrant, W.E.; Dong, X. Systemic Acquired Resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2004, 42, 185–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Loon, L.C.; Rep, M.; Pieterse, C.M. Significance of Inducible Defense-Related Proteins in Infected Plants. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 135–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klessig, D.F.; Choi, H.W.; Dempsey, D.A. Systemic Acquired Resistance and Salicylic Acid: Past, Present, and Future. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2018, 31, 871–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuladhar, P.; Sasidharan, S.; Saudagar, P. Role of Phenols and Polyphenols in Plant Defense Response to Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. In Biocontrol Agents and Secondary Metabolites; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 419–441. [Google Scholar]

- Minerdi, D.; Savoi, S.; Sabbatini, P. Role of Cytochrome P450 Enzyme in Plant–Microorganism Communication: A Focus on Grapevine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spartz, A.K.; Lee, S.H.; Wenger, J.P.; Gonzalez, N.; Itoh, H.; Inzé, D.; Peer, W.A.; Murphy, A.S.; Overvoorde, P.J.; Gray, W.M. The SAUR19 Subfamily of Small Auxin Up RNA Genes Promote Cell Expansion. Plant J. 2012, 70, 978–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, X.Z.; Liu, J.H. Transcriptional Profiling of Canker-Resistant Transgenic Sweet Orange (Citrus sinensis Osbeck) Constitutively Overexpressing a Spermidine Synthase Gene. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 2013, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, X.Z.; Liu, J.H.; Hong, N. Differential Structure and Physiological Response to Canker Challenge Between ‘Meiwa’ Kumquat and ‘Newhall’ Navel Orange with Contrasting Resistance. Sci. Hortic. 2011, 128, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeschlin, R.A.; Favaro, M.A.; Chiesa, M.A.; Alemano, S.; Vojnov, A.A.; Castagnaro, A.P.; Filippone, M.P.; Gmitter, F.G.; Gadea, J.; Marano, M.R. Resistance to Citrus Canker Induced by a Variant of Xanthomonas citri ssp. citri Is Associated with a Hypersensitive Cell Death Response Involving Autophagy-Associated Vacuolar Processes. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2017, 18, 1267–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Tsuda, K.; Parker, J.E. Effector-Triggered Immunity: From Pathogen Perception to Robust Defense. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2015, 66, 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, S.H.; Anand, S.; Singh, B.; Bohra, A.; Joshi, R. WRKY Transcription Factors and Plant Defense Responses: Latest Discoveries and Future Prospects. Plant Cell Rep. 2021, 40, 1071–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah-Zawawi, M.R.; Ahmad-Nizammuddin, N.F.; Govender, N.; Maon, S.N.; Abu-Bakar, N.; Mohamed-Hussein, Z.-A. Comparative Genome-Wide Analysis of WRKY, MADS-Box and MYB Transcription Factor Families in Arabidopsis and Rice. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Kumar, S.R.; Dwivedi, V.; Rai, A.; Pal, S.; Shasany, A.K.; Nagegowda, D.A. A WRKY Transcription Factor from Withania somnifera Regulates Triterpenoid Withanolide Accumulation and Biotic Stress Tolerance through Modulation of Phytosterol and Defense Pathways. New Phytol. 2017, 215, 1115–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramaroson, M.-L.; Koutouan, C.; Helesbeux, J.-J.; Le Clerc, V.; Hamama, L.; Geoffriau, E.; Briard, M. Role of Phenylpropanoids and Flavonoids in Plant Resistance to Pests and Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.S.; Wang, L.Y.; Chen, Y.J.; Tzeng, K.C.; Chang, S.C.; Chung, K.R.; Lee, M.H. Understanding Cellular Defence in Kumquat and Calamondin to Citrus Canker Caused by Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 79, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.D.; Dangl, J.L. The Plant Immune System. Nature 2006, 444, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesa, M.A.; Roeschlin, R.A.; Favaro, M.A.; Uviedo, F.; Campos-Beneyto, L.; D’Andrea, R.; Marano, M.R. Plant Responses Underlying Nonhost Resistance of Citrus limon Against Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019, 20, —. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broekaert, W.F.; Delauré, S.L.; De Bolle, M.F.; Cammue, B.P. The Role of Ethylene in Host–Pathogen Interactions. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2006, 44, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orce, I.G.; Debes, M.; Sendín, L.; Luque, A.; Arias, M.; Vojnov, A.; Marano, M.; Castagnaro, A.; Filippone, M.P. Closely Related Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri Isolates Trigger Distinct Histological and Transcriptional Responses in Citrus limon. Sci. Agric. 2016, 73, 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernadas, R.A.; Camillo, L.R.; Benedetti, C.E. Transcriptional Analysis of the Sweet Orange Interaction with Citrus Canker Pathogens Xanthomonas axonopodis pv. citri and X. axonopodis pv. aurantifolii. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008, 9, 609–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.; Haney, C.H. The Role of Plant Receptor-Like Kinases in Sensing Extrinsic and Host-Derived Signals and Shaping the Microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 2025, 33, 1233–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhou, L.; Yu, X.; Stover, E.; Luo, F.; Duan, Y. Transcriptome Profiling of Huanglongbing (HLB)-Tolerant and -Susceptible Citrus Plants Reveals the Role of Basal Resistance in HLB Tolerance. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).