2.2. Spin-Coating Thickness Model Simulation

The spin-coating step determines the initial resist thickness distribution, which has a profound impact on the fidelity of subsequent EBL processes. The thickness non-uniformity causes non-uniform exposure conditions since the local electron scattering and secondary electron yield depend on the thickness. Consequently, line edge roughness and pattern fidelity can be degraded if the resist thickness profile is not well modeled and compensated. Therefore, the inclusion of spin-coating impacts in the OPC design phase is essential to ensure robust downstream pattern transfer.

From the transport phenomenon perspective, the resist film deposited by spin-coating can be modeled as a thin Newtonian liquid layer under radially spreading conditions during rotation. The governing forces include centrifugal force, which drives outward flow; viscous shear stress, which provides resistance to radial stretching; capillary forces, which dominate near the wafer edge and generate the edge bead; and solvent evaporation, which reduces film thickness uniformly over time.

Treating the spin-coated resist as a Newtonian liquid under axisymmetry, the depth-averaged radial flux is obtained from the radial momentum balance in the lubrication approximation:

where

is the local film thickness as a function of radial position

and time

, the viscosity

, the density

, the spin speed

(

), and the pressure

. Substituting this constitutive relation into mass conservation under axial symmetry yields

where

represents the evaporation rate. Having symmetry with respect to angle

, only the radial direction

remains;

. In the wafer interior (away from the edge), curvature effects are weak so that

, so it follows the classic ODE for thickness,

which recovers the classical Emslie–Meyerhofer spin-speed scaling for the “core” thickness once the evaporation term is accounted for. The boundary conditions are symmetry at the wafer center (

,

) and no flux at the wafer edge (

), where bead buildup is accounted for by the Bornside correction. These fundamental considerations form the theoretical basis from which empirical and semi-empirical relations are obtained.

Collecting these results, the thickness profile , which represents the local resist thickness as a function of radial position and spin speed , is written as the sum of a core term and a capillary edge-bead correction:

where the three functional components scale with spin speed according to:

In this case, is a reference spin speed, and are the scaling exponents for central thickness, edge height, and edge-bead width, respectively. This setup combines the Emslie–Meyerhofer spin-speed relation with Bornside-type edge-bead corrections, ensuring fidelity at both the global and local levels.

The first term in Eq. (5) corresponds to interior (“core”) thickness driven by the balance between centrifugal forcing and viscous dissipation, which—together with evaporation—gives rise to the classic Emslie–Meyerhofer relation for the dependence on the spin speed (with depending on the type of evaporation). The polynomial term in reflects finite-radius corrections to the almost nearly uniform core. Closer to the edge of the wafer, capillarity becomes non-negligible: the curvature-induced pressure introduces a capillary pressure gradient that competes with centrifugal and viscous stresses, creating a boundary-layer-like region near the edge bead. Rather than re-solving the full lubrication PDE with curvature, a Bornside semi-empirical correction is adopted with a localized envelope , where is the edge-bead amplitude and its characteristic width. Both parameters inherit spin-speed scaling from the underlying capillary–viscous–centrifugal balance.

For exposure coupling, the local resist thickness is normalized and included in the electron-beam development threshold as

where

is the threshold of base development, α is a sensitivity coefficient, and

is the spatially normalized thickness map. This couple affect ensures that thickness differences in absorption affect local dose deposition and CD variability directly.

Model validation

The validity of the proposed spin-coating thickness formulation was assessed by comparison between the simulated results and both widely adopted literature correlations and manufacturers’ specifications.

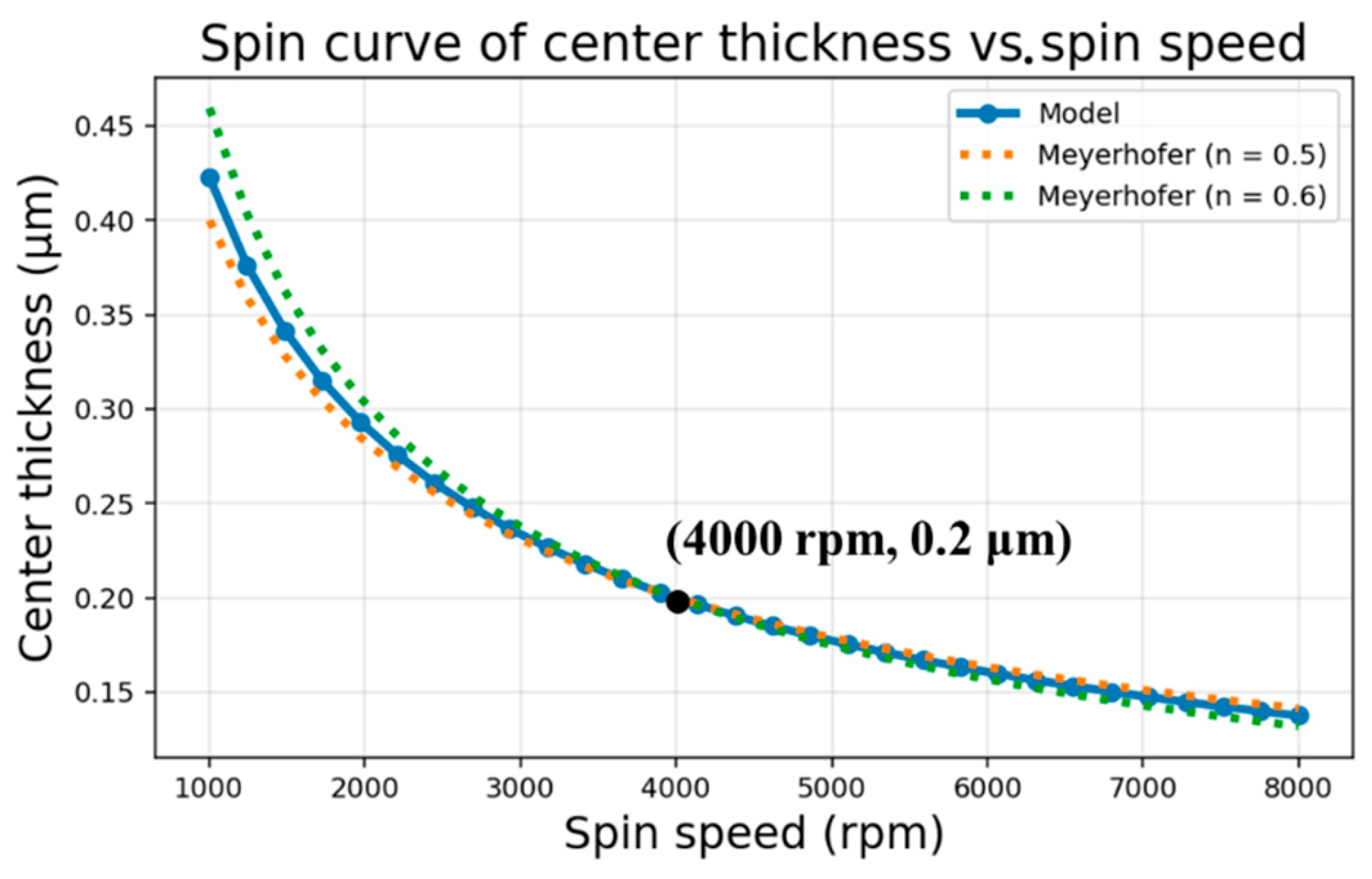

Figure 2 shows the correlation between center thickness and spin speed given by the spin curve. With a spin rate of 4000 rpm, the simulated thickness matches the datasheet value of 0.20 μm of AR-P 6200.09 as reported by Allresist [

55]. The proposed power-law index of

in our study falls within the conventional Meyerhofer evaporation-dominated range (0.5–0.7) [

37], and also agrees with the viscous flow scaling relation of the type

by Emslie–Bonner–Peck [

36] that prevails at the onset of spinning. This alignment with both empirical data and classical scaling theories demonstrates that the model closely approximates the expected speed-thickness relation over a very wide range of operations.

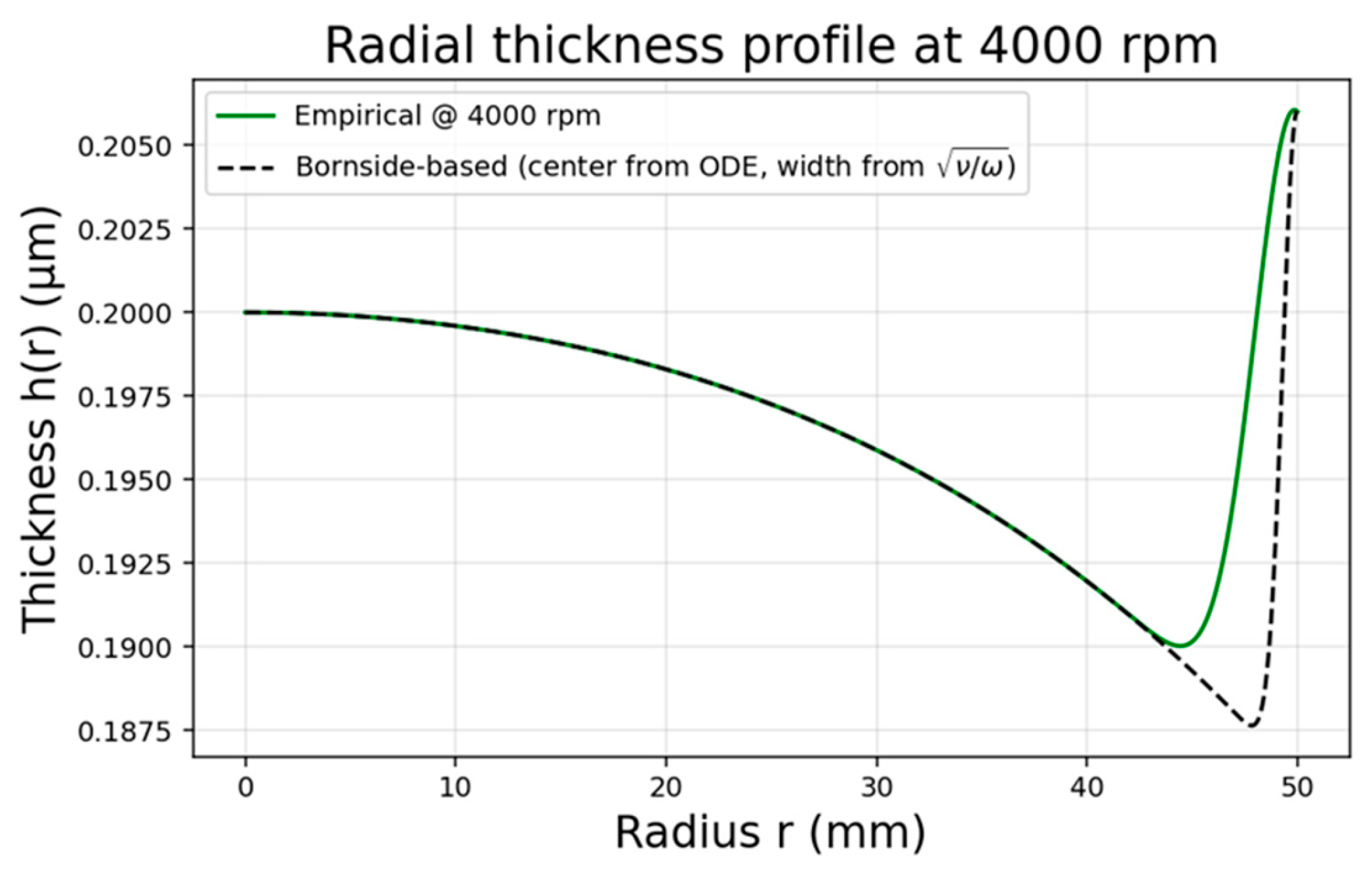

Figure 3 presents the radial thickness profile at 4000 rpm, which has been checked against the one-dimensional solution of Bornside et al. [

56]. Least-squares calibration of the polynomial coefficients provides

and

, which reduces the across-wafer RMS error to 3.8% with respect to the Bornside numerical profile. The mid-radius depression and the Gaussian-type thickening at the wafer edge have been modeled successfully, and the parameterization of the edge bead peak at approximately

has been derived by the parameter set

.The parameterization agrees with the 5–10% excess thickness at the wafer edge that has been determined by the FAB.nano application note [

57].

We should note that minor deviations between the simulation outputs and experimental data are typically discernible in actual spin-coating processes due to the uncontrollable dynamics of the edge beads and the wafer–chuck interface boundary conditions. These can be corrected by Bayesian inference or Kalman filtering–based data assimilation frameworks, which allows the reconciliation of the process measurements and the physical principle-based models. In practice, the region of minimum deviation is selected for following exposure coupling; in this work, a representative window of 600 nm × 600 nm was chosen in

Section 3.1 to provide reliable calibration and smooth transition to the subsequent EBL simulation stage.

2.3. E-Beam Lithography (EBL) Simulation

The resist exposure during EBL is precisely governed by the movement of charged particles within the column and their corresponding interaction of resultant character with the resist and the substrate. In this case, electron dynamics are defined through an explicit employment of the Lorentz force equation,

where

and

are the electron mass and charge, respectively. In practice, the magnetic field inside the accelerating region is negligible. This approximation is justified because the accelerating gap sustains MV/m-scale electric fields while residual magnetic flux is strongly suppressed by μ-metal shielding (high-permeability alloy), making the magnetic-to-electric force ratio

. For 30-keV electrons (non-relativistic approximation

) and typical fields

, the equivalent magnetic field is

, whereas stray magnetic field in the shielded gun region is far below this threshold

; thus, magnetic contributions in the accelerating region can be neglected to first order. Consequently, the Lorentz equations simplify to a coupled system driven solely by the radial and axial electric fields:

These fields come from the structure of the electrodes: the anode accelerates electrons with an electrode voltage of , and the focusing electrode applies along a column of length . The conversion between electrode voltage and electric field components can be directly obtained from electrostatics mathematically represented as . For application in this simplified model of a column, every electrode can be represented as a localized potential source,

where

can be either the anode voltage

or a focusing voltage

. A derivative of this potential with respect to

and

then generates the radial and vertical components of this electric field used within this trajectory integration process. Physically, this process corresponds to Lorentz force law considering a charge on an electron to be

. By substituting this negative charge within Eq. (11) (12), we guarantee a positive voltage on an electrode will create an attractive force upon an electron beam to reproduce the actual behavior of electron optical columns.

Trajectories are also set up at a finite source size and angular divergence (

,

) by optimization in

Section 3.2, representing the physical spread of the electron at emission. The integration procedure is based on the Dormand–Prince 5(4) method that assures accurate time-resolved tracking of focusing behavior over nanosecond scales [

58].

The trajectory set also offers simultaneously a description of the beam focusing and a quantitative characterization of the effective spot size at the resist plane. The landing radius set is transformed into a Gaussian-equivalent width using a robust median-based estimator,

Here, MAD denotes the median absolute deviation. This approach creates a direct mapping between the beam blur used in exposure calculations and the related column physics that governs particle transport. A wide focusing voltage (5~25kV) adjustment in

Section 3.2 is performed to minimize

and thus practically mimicking the autofocusing action of a real EBL system.

Having established the forward beam width, the exposure is modeled by rastering the pattern at a fixed step size . Any pixel tile that has an exposed area greater than a specified fraction of receives a charge shot,

where

is the nominal base dose. Superposition of Gaussian spots of width

gives us the fundamental exposure distribution

, accounting for the influence of a finite beam size.

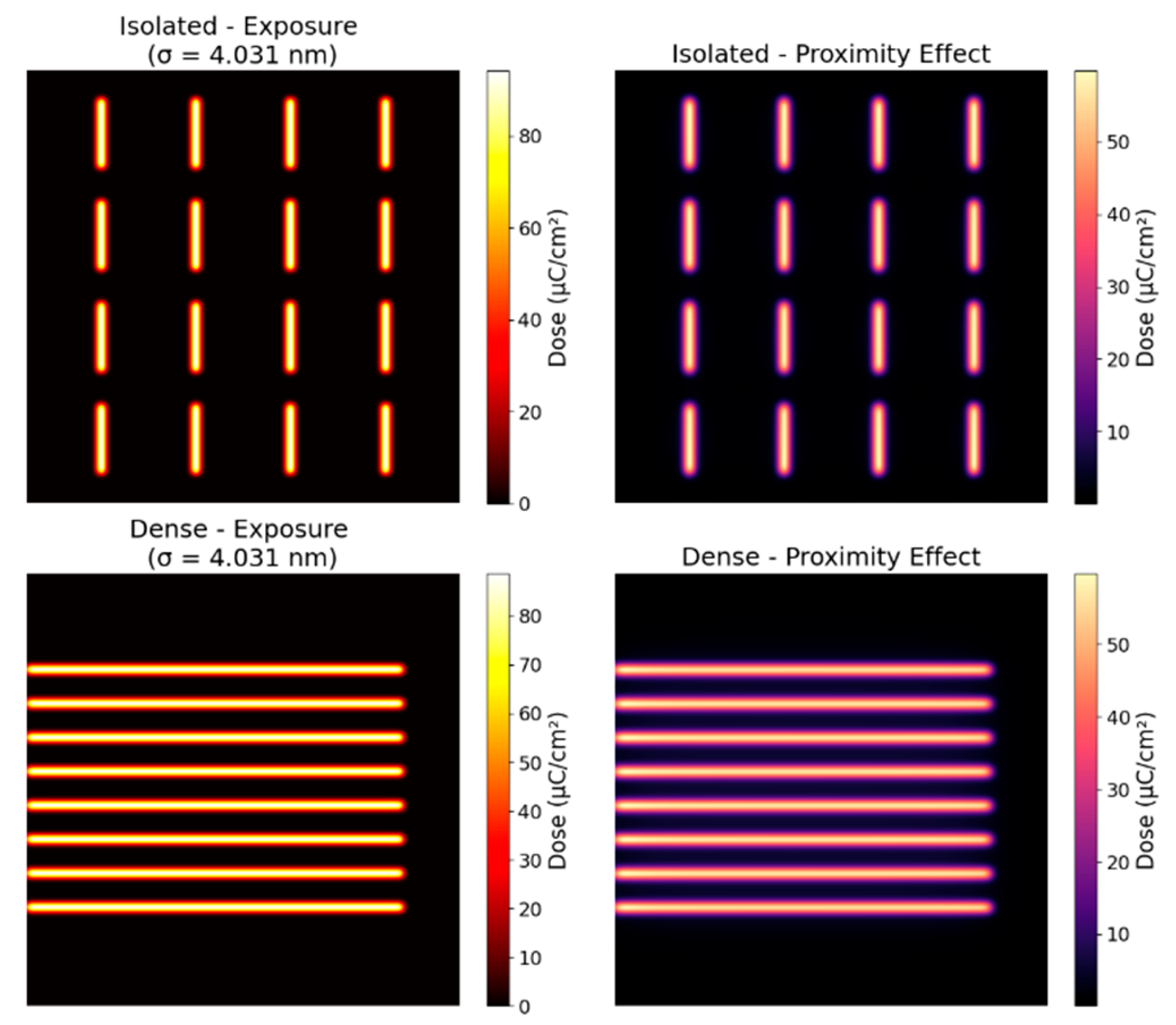

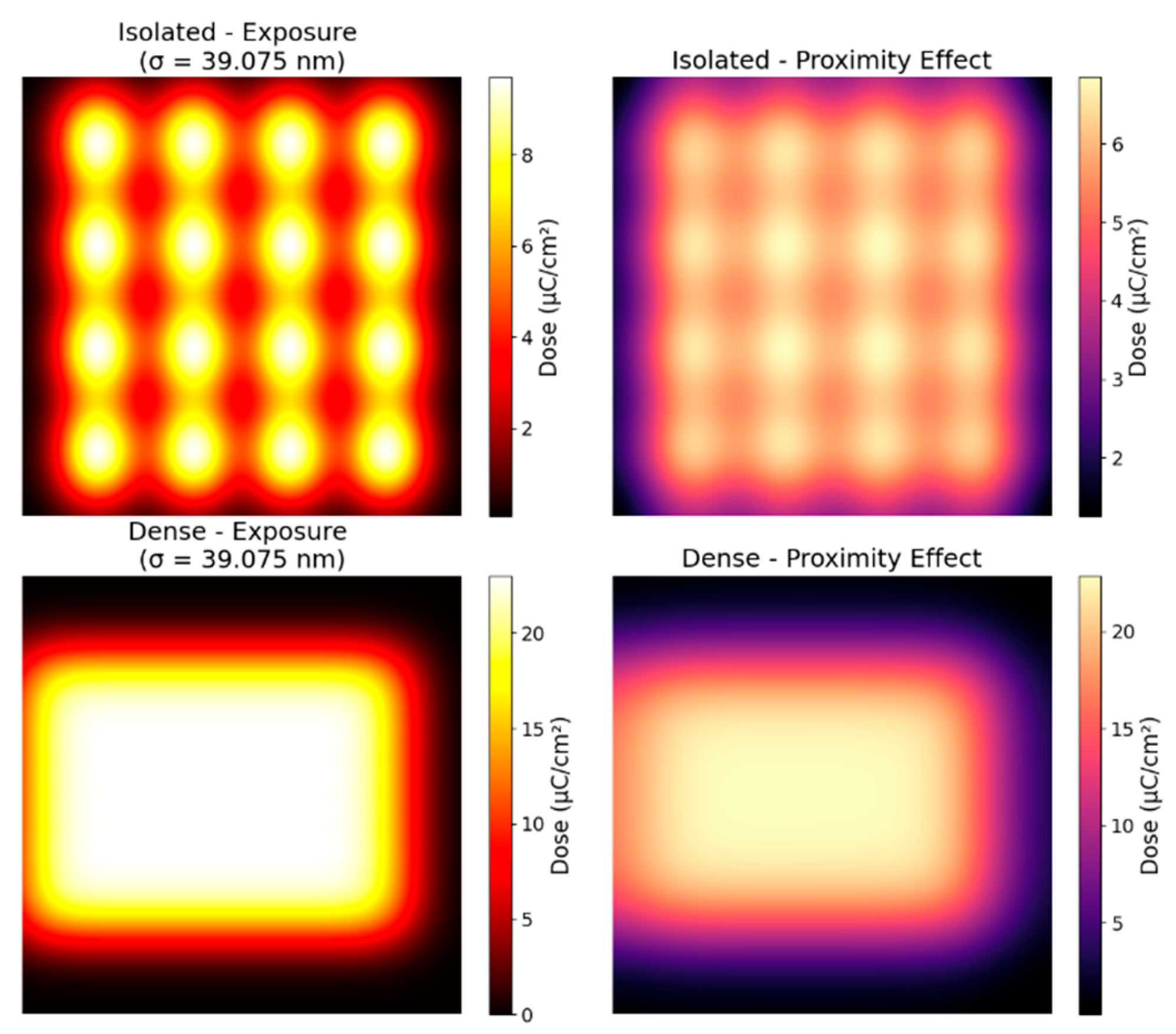

To simulate those scattering phenomena, the exposure map is convolved with a hybrid kernel that consists of two physically distinct components: a Gaussian that models the tightly concentrated primary beam, and a squared-Lorentzian that accounts for the slow drop of the tails due to the backscattered electrons. The modeling expression for the hybrid kernel is represented by

with weights

and

. In the present work

, and the Lorentzian scale is

. The convolution,

generates the effective dose distribution, whereby at the same time short-range forward scattering and long-range proximity effects are accounted for.

The development of the resist is modeled by a modulated global dose threshold from the previous model of spin-coating. The threshold is given by the following

where

is normalized thickness map after normalization,

is the base threshold ratio, and

quantifies the sensitivity to thickness variation. This expresses the physical truth that slightly higher exposures are needed for thicker resist areas in order for them to fully clear. The final resist pattern is described as

This simulation pipeline thus integrates column electrostatics, beam-size proxies from trajectories, scattering-induced proximity effects, and solubility of the resist into one physically valid model. The results—spatially resolved dose maps, proximity-corrected exposure, and developed contours—become direct inputs for following reactive ion etching simulation and NIL template pattern transfer.

2.4. Reactive Ion Etching (RIE) Simulation

To model the profile evolution during the dry etching stage, a physics-informed level set method is employed to simulate anisotropic RIE. This stage constitutes the third phase of the proposed three-stage NIL simulation framework, following EBL patterning. At this point in the process, a patterned photoresist layer has been transferred onto the substrate, and both materials are subjected to plasma etching to further define the desired topography. During RIE, vertical etching is dominated by directional ion bombardment; lateral erosion arises primarily from ion-assisted effects due to finite angular spread, with an additional minor omnidirectional chemical contribution. The simulation captures this dual-mode etching behavior by combining an angular-dependent etch rate model with a material-specific selectivity function. This allows for accurate prediction of profile evolution, accounting for the fact that photoresist masks remain largely unaffected during etching, while underlying substrate materials are etched based on local surface orientation and exposure.

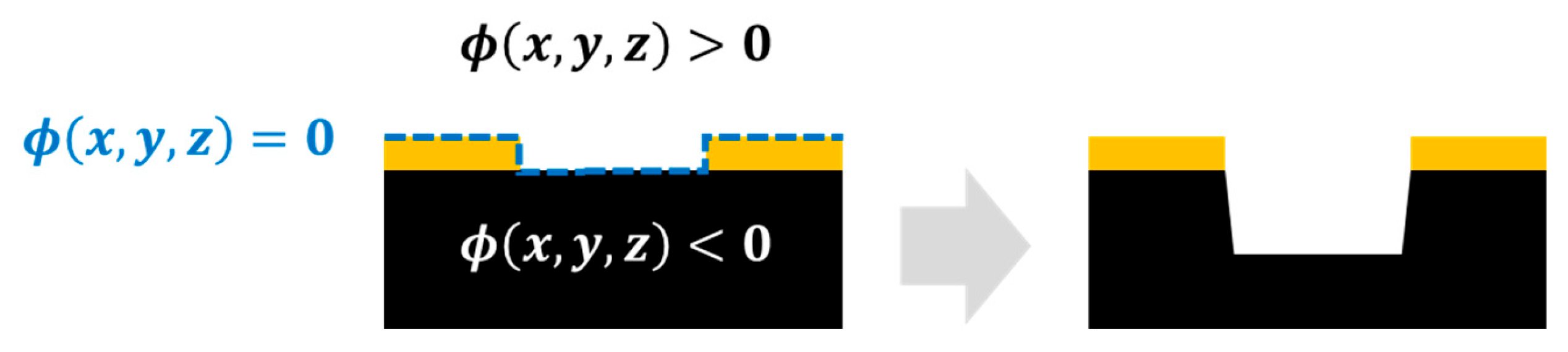

The interface between photoresist and substrate is represented using a level set function

, where in

Figure 4 the zero-level set

defines the material surface. In this formulation,

denotes the vacuum (air) region, while

corresponds to material regions, including both photoresist and substrate. The level set evolves in time according to the following Hamilton–Jacobi equation:

Here, is the total etch rate at the interface and is the magnitude of the spatial gradient of , ensuring proper geometric propagation along the normal surface. To account for material-dependent etch selectivity, photoresist is assigned a finite selectivity of 0.10, yielding a vertical etch rate that is one-tenth of the substrate’s and thus only minor mask erosion. In contrast, substrate regions undergo directional and chemical etching as described by the anisotropic etch model.

The etch rate is computed as a combination of directional (ion-driven) and isotropic (chemical) components:

where

denotes the intrinsic basic material-dependent vertical etch rate. The term

represents the cosine of the angle between the local surface normal and the vertical direction, thereby quantifying how aligned the surface is with the incoming ion flux. The parameter

introduces lateral etching behavior by allowing reduced etch rates on sloped or horizontal surfaces, mimicking the effect of angular broadening due to off-normal ion incidence and chemical diffusion. Finally,

accounts for the isotropic chemical etching contribution, treated here as a dimensionless scaling factor added to the angular term and modulated by

.

The surface normal vector is computed from the normalized gradient of the level set function:

To approximate the spatial derivatives of the level set function, a central difference scheme is employed at interior grid points. This method, derived from a symmetric Taylor expansion, achieves second-order accuracy, meaning that the associated truncation error decreases proportionally to as the spatial grid is refined. The discrete gradient at an interior point is computed as:

At the computational boundaries, where data from only one direction is available, first-order forward and backward difference schemes are applied. These one-sided methods yield first-order accuracy, with truncation errors that scale linearly as . Specifically, the boundary derivatives are computed using:

These schemes ensure stable and reasonably accurate estimation of spatial gradients, which are essential for normal vector calculation and interface evolution in the level set framework. In the temporal domain, the level set equation is integrated using an explicit Euler scheme, which advances the interface over time based on the local etch rate and gradient magnitude:

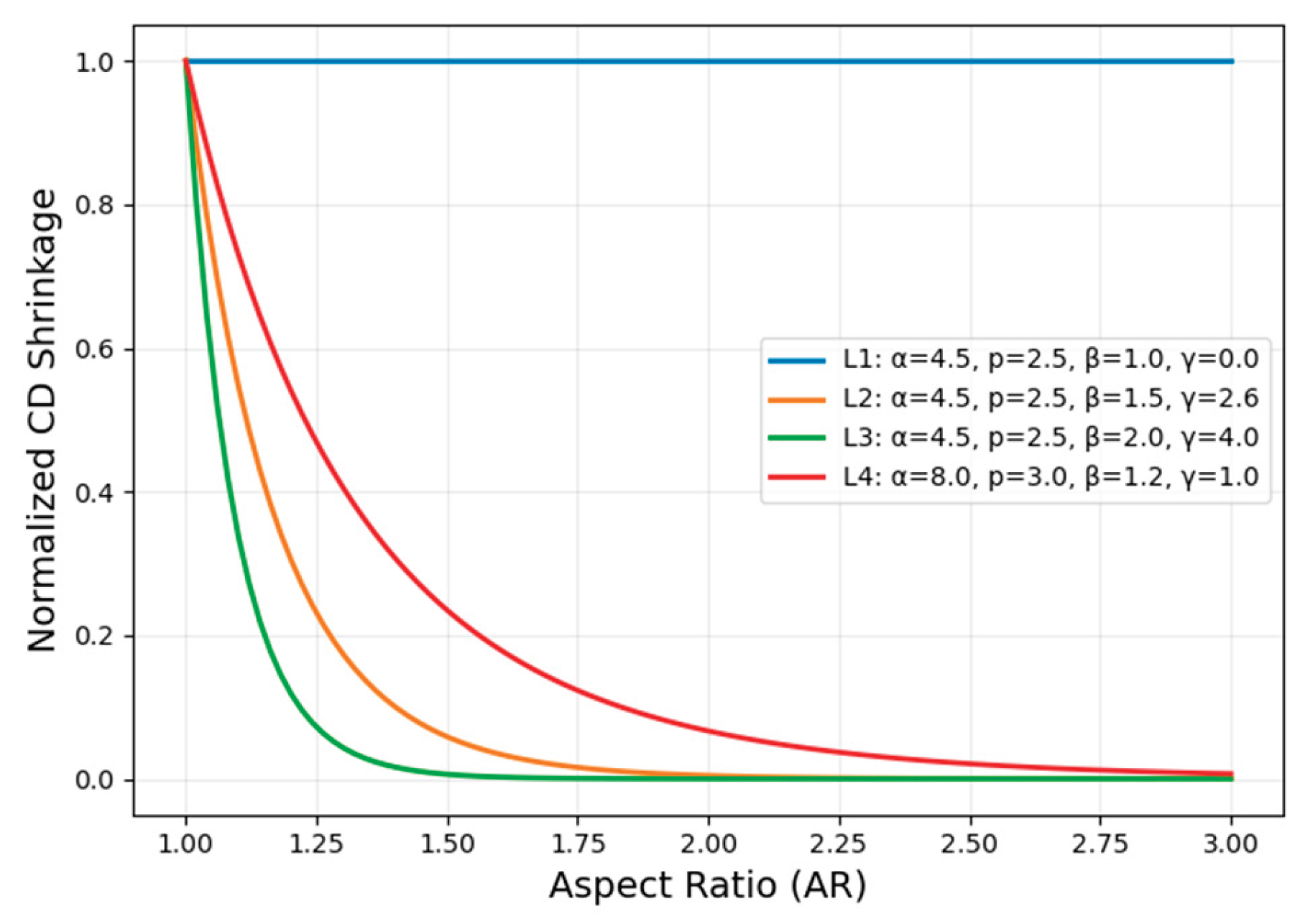

To justify the experimentally observed speed reduction inside high-aspect-ratio (AR) trenches, the basic level-set update (Eq. (22) ~ Eq. (29)) is supplemented by Aspect Ratio Dependent Etching (ARDE) factors that modulate the vertical and lateral channels as functions of local AR. Here, we explicitly integrated ARDE into the Hamilton–Jacobi scheme and numbered the equations for reference [

59]. ARDE is a transport-limited phenomenon in which the local etch rate decreases as a feature becomes deeper and narrower because of reactant depletion, by-product trapping, and partial ion-flux shadowing. We let the interfacial etch rate depend on the local aspect ratio

, where

is the etched depth accumulated at the substrate plane,

is the local opening width estimated from the ADI via a Euclidean distance transform, and

avoids division by zero. In this manner, the level-set evolution becomes

with material label

and unit normal

. For the substrate we write the anisotropic, transport-modified etch rate as

Eq. (31) outlines the contributions of vertical, lateral, and isotropic-chemical factors while keeping only a single material rate scale for dimensional consistency. The angular ion-flux envelope , controlling the vertical projection, is modeled as the Gaussian function of the incidence angle:

A smaller represents a more collimated beam and hence stronger anisotropy; conversely, a larger captures a wider angular distribution. This selection is convenient to calibrate (the single parameter maps to angular half-widths obtained from the instrument), numerically smooth (beneficial for stable normal estimations), and multiplicative. Therefore, it composes cleanly with other transport penalties outlined below.

Access limitation due to ARDE is encoded through a monotone penalty,

which reduces the effective vertical contribution as the feature deepens and narrows. Sidewall-dominated transport and passivation are captured by a stronger attenuation on the lateral channel,

so that narrow, high-AR trenches experience a disproportionately larger reduction in sideways advance than in vertical descent. In Eq. (21), the lateral geometric factor is written as

, which is equivalent to

by the identity

. Using

rather than

(or a signed

) ensures smoothness and non-negativity, avoids a cusp at

, and weights slopes proportionally according to their squared tilt. These features improve stability and eliminate grid-orientation bias in the three-dimensional updates. An expression for the chemical term is modeled as a dimensionless constant scaling of the base rate,

, i.e., independent of AR in this implementation. When desired, geometric shadowing in the vertical channel can be incorporated by replacing

with

, where

with

.

With Eq. (30) ~ Eq. (34), inward CD shrinkage arises during the evolution rather than being imposed afterward. As

grows in a trench,

lowers the vertical transport and

suppresses lateral advance even more strongly. Integrated over time in the Hamilton–Jacobi update, narrow features thus propagate more slowly both downward and sideways than wide openings. For illustration,

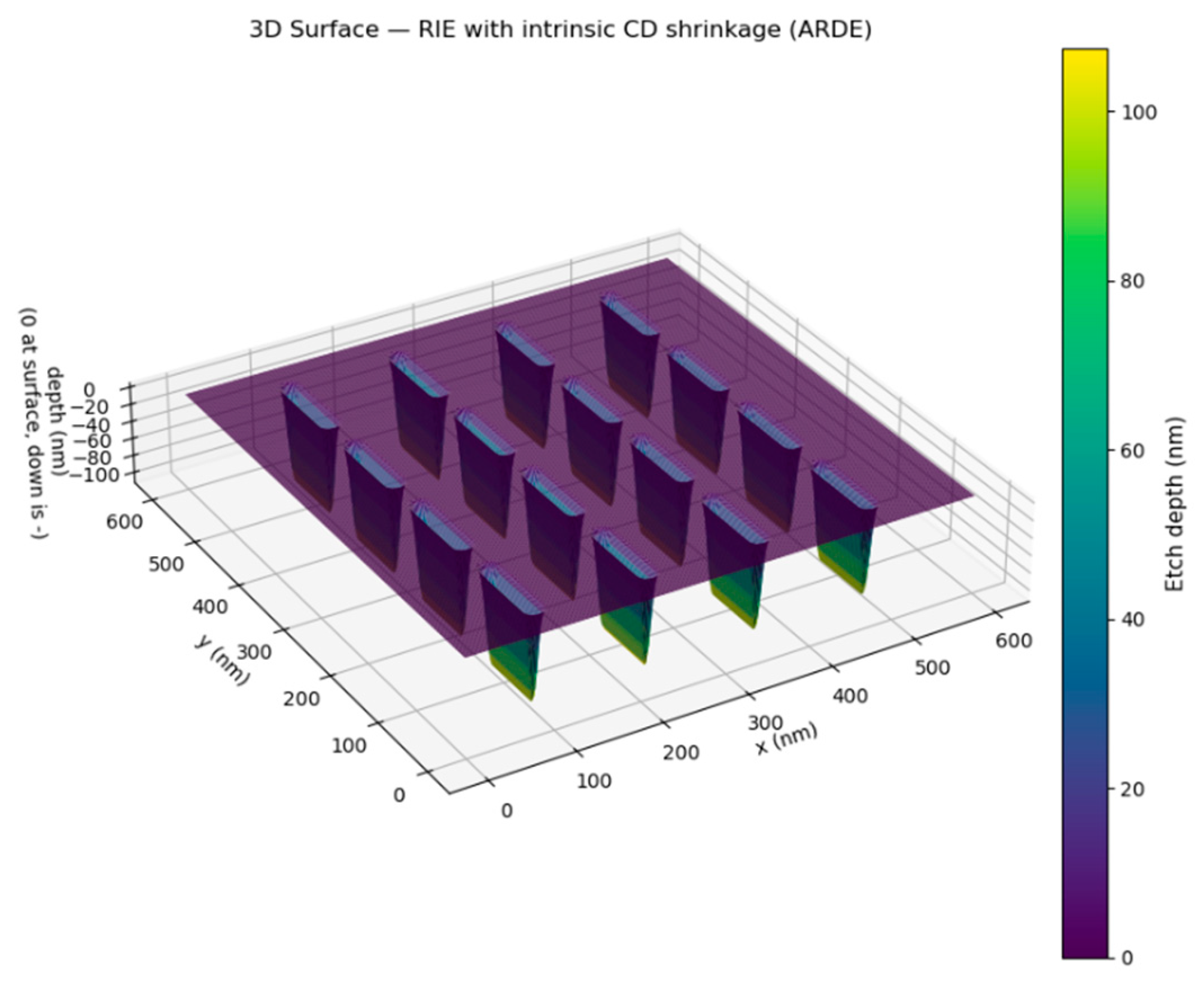

Figure 5 shows the simulated 3D final etched topography for isolated design layout under the RIE settings.

In addition to the continuous profile evolution, the computed etch depth distribution is subsequently mapped to a binary after etch inspection (AEI) image. The conversion from a continuous depth field

to a binary mask is performed by operating with a depth-biased threshold criterion:

where

denotes the nominal resist thickness and

is an adjustable scaling factor (typically set to 0.8). This operation ensures that only regions with sufficient penetration across the resist are classified as etched, thus reproducing CD shrinkage observed in experimental AEI profiles.

The resulting AEI contour exhibits a measurable inward bias that is consistent with transport-limited wafer behavior. In practice, (ARDE strength), (ARDE nonlinearity), (lateral weighting), (lateral attenuation exponent), (lateral passivation factor), and (beam collimation) are calibrated against cross-sectional SEMs so that simulated depth, sidewall angle, and CD loss match process trends without the need for ad-hoc post-processing. Together, the depth-biased thresholding offers a compact yet physically consistent approximation of AEI formation, complementing the physics-based level set evolution and facilitating quantitative analysis of CD shrinkage, line edge roughness, and pattern fidelity degradation.

2.5. Pattern Fidelity Metrics to be Used

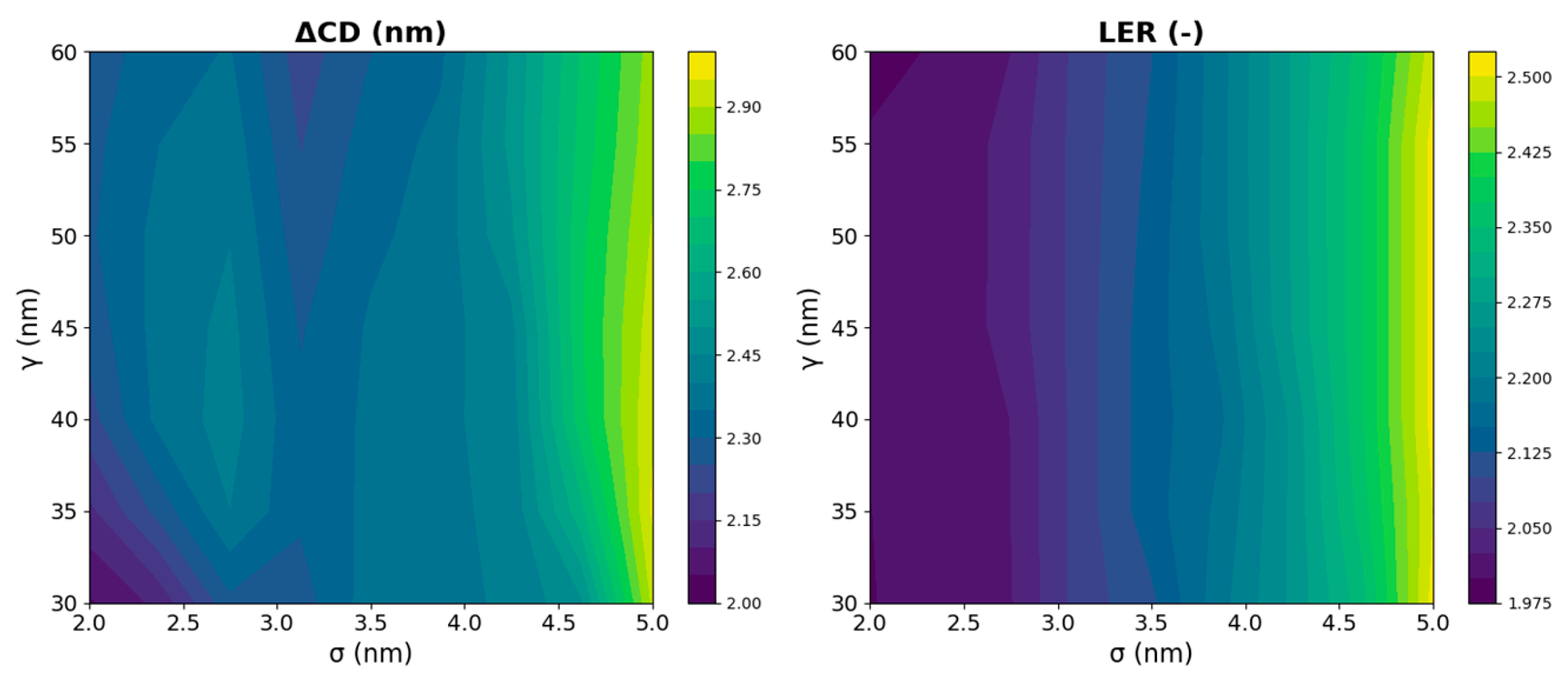

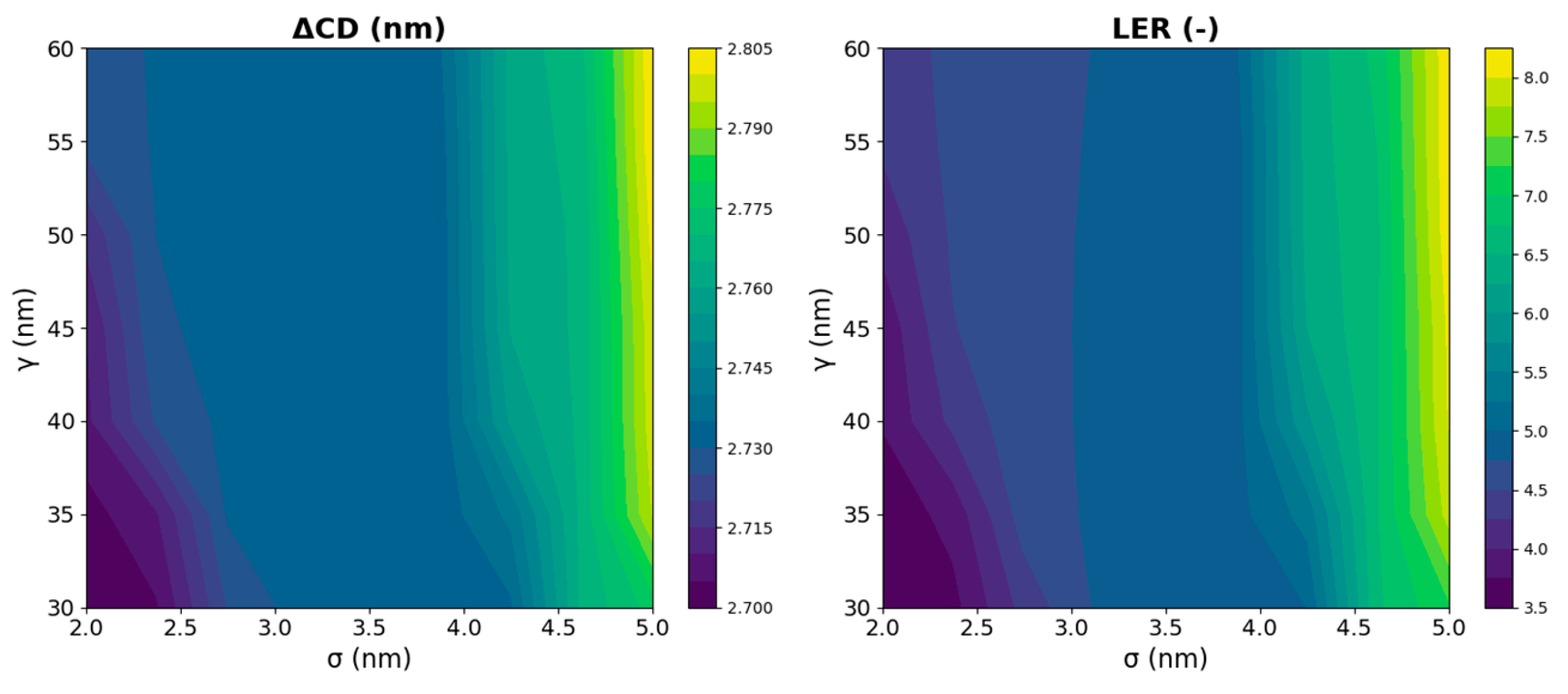

To quantify lithographic pattern fidelity produced by simulation, three mutually complementary metrics were applied: the normalized mean squared error (NMSE), the critical-dimension error (∆CD), and the line edge roughness (LER). These indicators present distinct but related views of pattern quality, covering overall image similarity, dimensional accuracy, and edge sharpness, respectively. All three metrics are widely used in OPC schemes of relevance to semiconductor lithography and are directly applicable to both EBL and RIE stages in this study.

-

(4)

Normalized Mean Squared Error (NMSE)

The NMSE compares the overall pixel-wise difference between the designed binary pattern and the simulated or developed pattern. It is given by:

where

is the number of total pixels. This normalized version provides scale invariance and a globally defined contour fidelity measure. In semiconductors, NMSE represents how well the exposure and development process can replicate desired pattern density and hence suits best for analyzing stochastic variations in near-10-nm features.

-

(5)

Critical-Dimension Error (∆CD)

The ∆CD quantifies the difference in linewidths from design to simulation on each contour feature. Rather than focusing on overall area differences, this metric directly measures the length of the shortest edge of each contour pattern printed in nanometers. The ∆CD is given by the expression:

where

stands for the nominal target width defined in the design layout, and

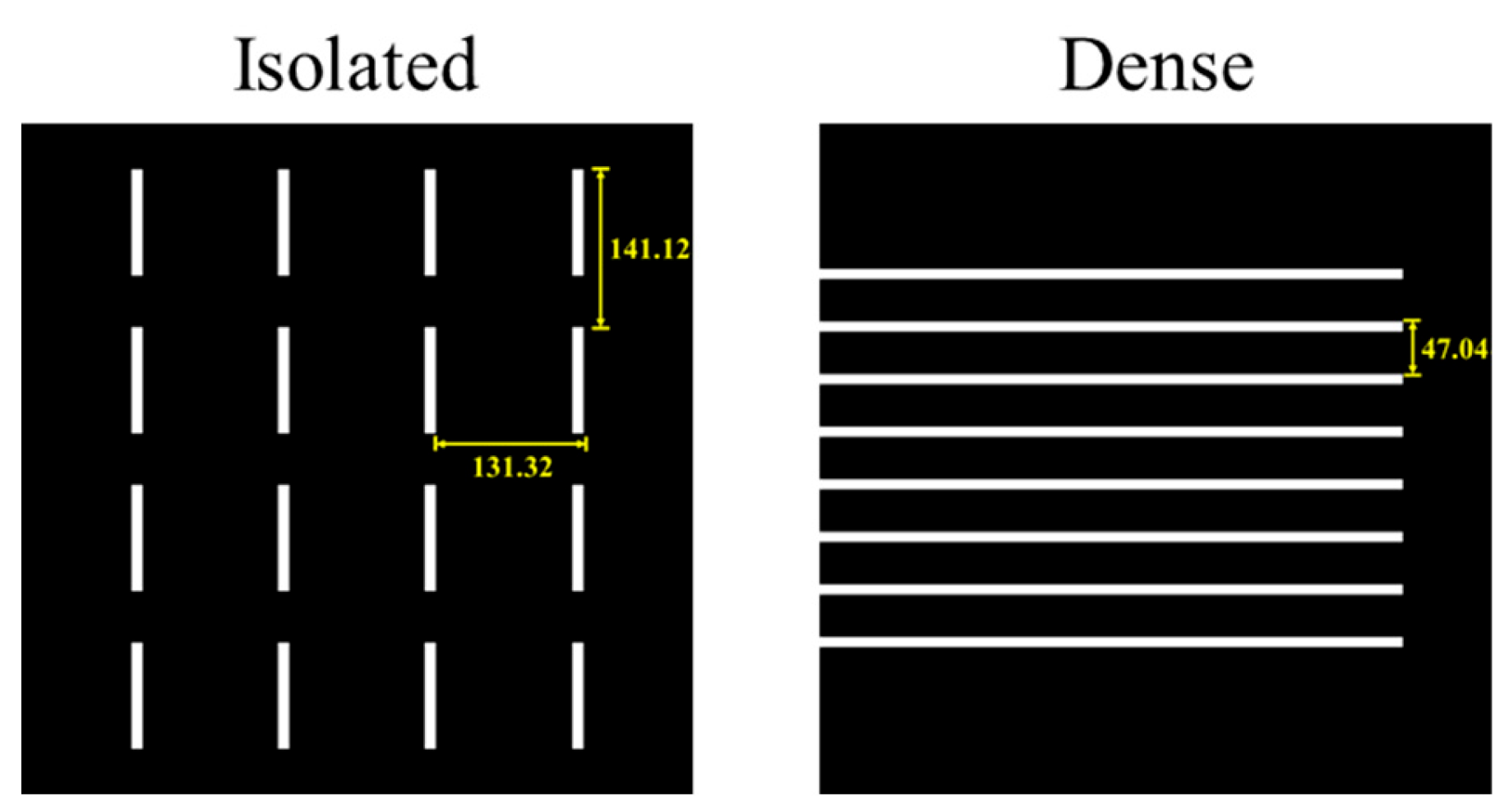

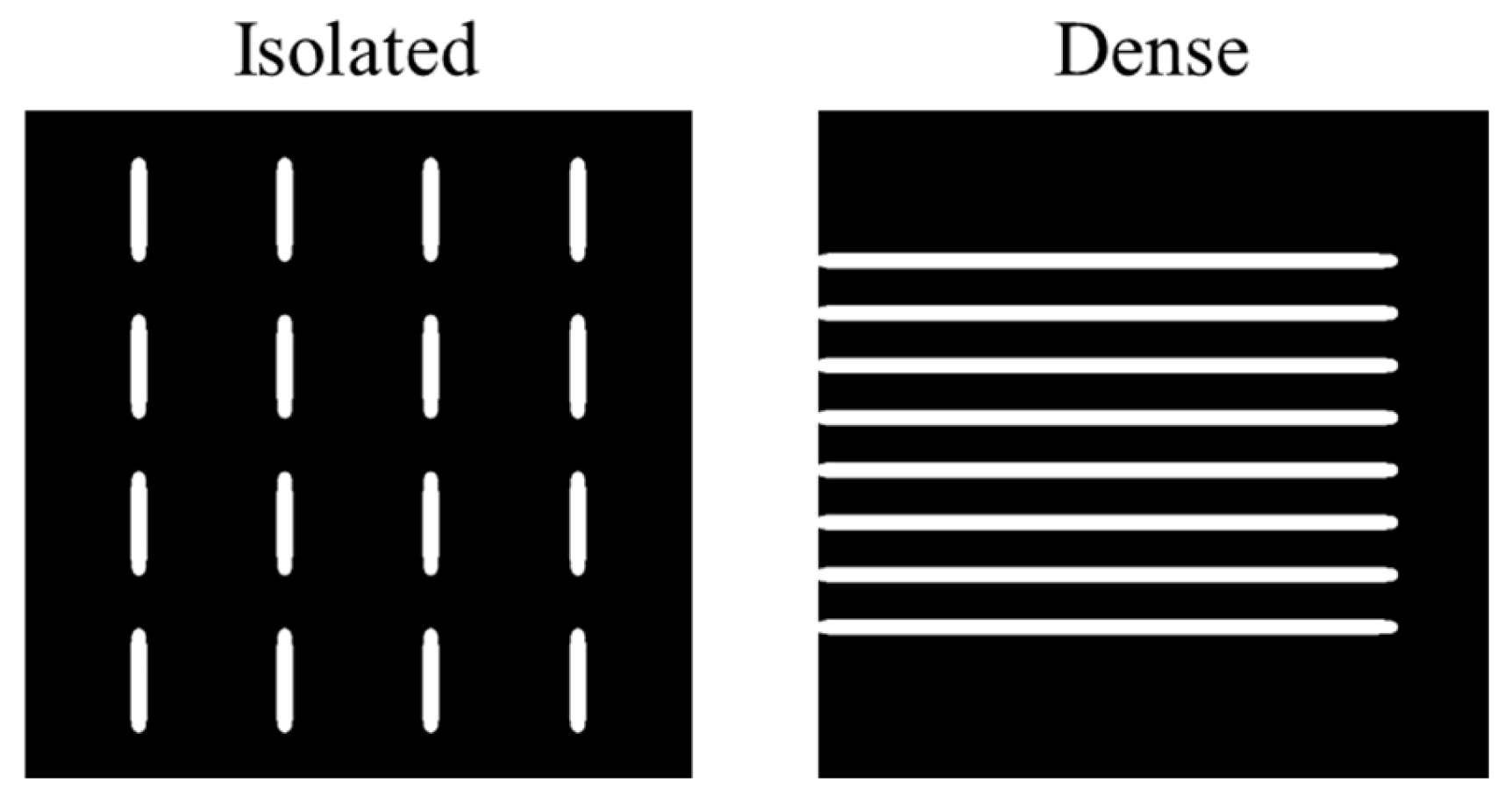

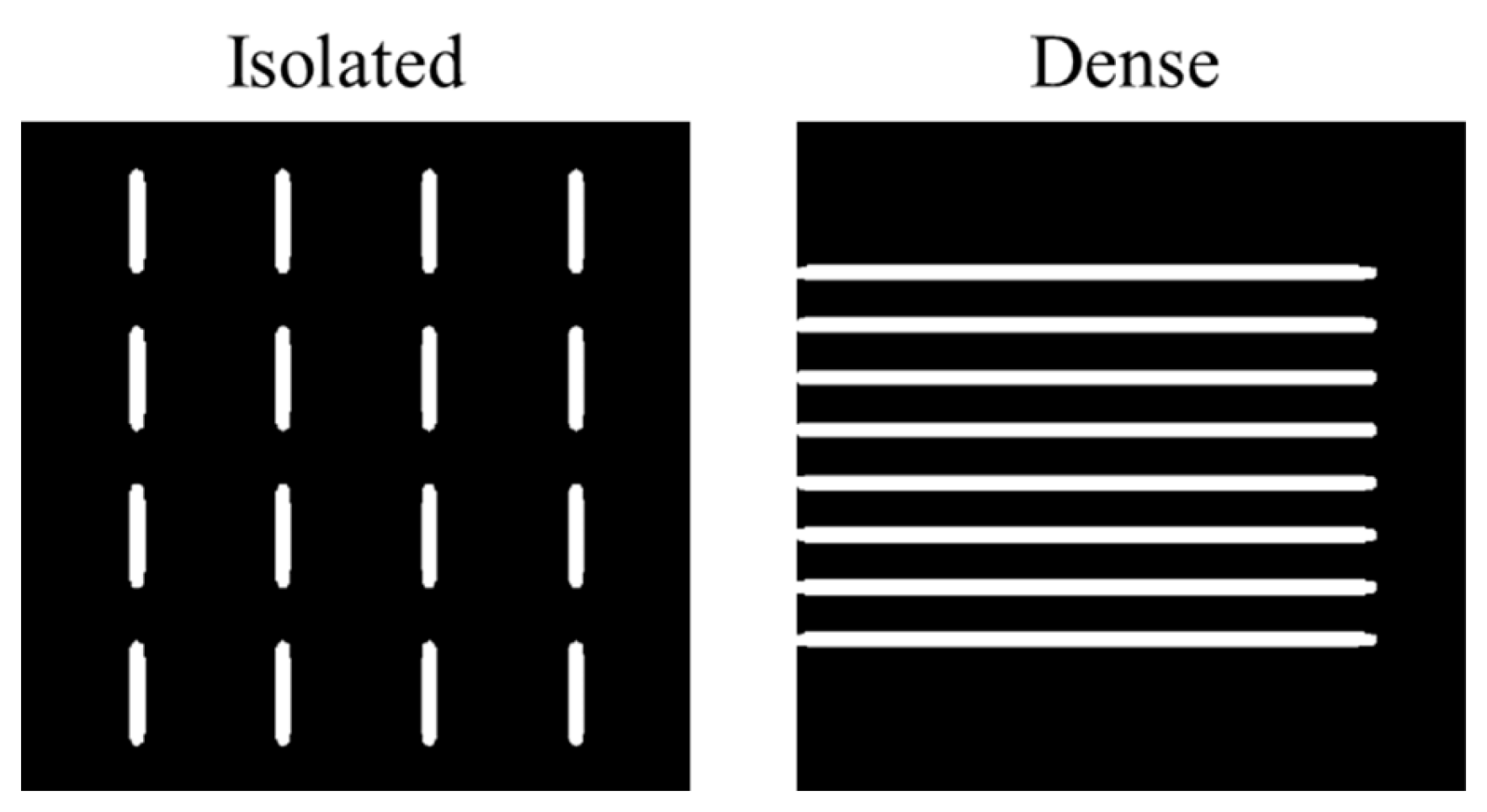

denotes the measured contour width after the simulation process (EBL or RIE). The design layouts used in this simulation investigation are represented in

Figure 1. From a lithographic perspective, ΔCD offers a direct quantification of dimensional accuracy, which serves as a key indicator of process proximity effects and pattern transfer fidelity across exposure and etching stages. While considering OPC, minimizing ΔCD ensures effective contour replication in accordance with design intent and reduces bias arising from local pattern density or exposure-induced effects.

-

(6)

Line-Edge Roughness (LER)

LER is used to find out how much edges after processing deviate from their initial straight boundaries. It is computed discrete representation by:

Here, and are edge profiles from the design layout and simulated patterns, respectively. This technique offers a feature process-independent edge fidelity measurement that is standardized. From a semiconductor standpoint, LER plays a robust role in transistor performance, line resistance, and device variability, thus forming one of the most significant parameters both in OPC and process qualification.

In the present framework, these three metrics are applied after both the EBL and RIE simulations to benchmark pattern fidelity across different process conditions. NMSE captures global deviations in the aerial or dose map, ΔCD highlights systematic dimensional deviations of printed contours relative to the intended design geometry, and LER provides sensitivity to fine-scale roughness amplified during resist development or etching. Their combined use ensures a balanced evaluation of proximity effects, beam focusing conditions, and downstream transfer fidelity. Importantly, this triad of metrics parallels the evaluation protocols used in OPC workflows, thereby reinforcing the industrial relevance of the physics-based simulation results presented here.