1. Introduction

Although Prosthesis patient mismatch (PPM) remains a controversial topic in literature, meta-analysis review suggested any degree of PPM is associated with poorer outcomes following surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) [

1,

2,

3]. The deleterious effects of mismatch are widely described in literature; attenuation of ventricular mass regression, reduces systolic function, worsens symptoms and quality of life, reduces bioprosthetic valve durability, and associated with increased postoperative mortality and late cardiac events [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Different approaches to avoid PPM post SAVR are implemented by surgeons across the globe including aortic root enlargement (ARE), sutureless valves, and low profile mechanical valves valves in middle or advanced age patients.

Current guidelines do not provide a standardized approach for specialist aortic valve service to prevent PPM, despite consistently poor outcomes reported in literature [

8]. In this study, the authors describe a program, from referral to discharge, following specific pathways including a novel algorithm, introducing new nomenclature to standardize a common language amongst valve specialists who design the surgical strategy to prevent any degree of mismatch. This proved successful for the first 100 consecutive patients through a contemporary clinical framework providing guidance for surgeons to anticipate and prevent mismatch, and in addition consider a lifetime valve strategy.

Authors acknowledge the difficulty in comparing valve types to predict PPM since its description by Rahimtoola in 1978 [

9]. For this study, we followed the formal classification of indexed effective orifice area (iEOA) calculated through dividing the valve effective orifice area (EOA) by the patient’s body surface area (BSA). The iEOA classifies mismatch as None or mild ppm >0.85 cm

2 / m2, moderate between 0.65 – 0.85 cm

2 / m2, and severe PPM < 0.65 cm

2 / m2. The rate of mismatch reported in literature is 2 to 20% in severe PPM, and 20 to 70% in moderate PPM [

10,

11,

12]. This criterion has been extensively tested over the years: the transvalvular gradient and the transvalvular flow play a key role in the functionality of the prosthesis size implanted. The former is determined by the EOA and transvalvular flow, which in turn is determined by cardiac output (CO) and BSA [

13] . This explains how same size prosthesis on different BSA patients could develop different types of PPM and lay out the principles of surgical planning and decision making before SAVR. Therefore, iEOA is patient specific and not prosthesis specific and cannot be transferred to other patients [

14,

15].

In this study, we propose a step-by-step approach combining the relevant variables available in current practice to prevent mismatch in a standardized approach:

1. Single point of referral as standard practice for aortic valve surgery.

2. Updated PPM calculator for prediction of mismatch.

3. Echocardiographic or CT assessment of the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) or annulus.

4. Heart team supporting surgeon’s operative strategy, and targeted selection of surgical bioprosthetic valves that are compatible for uncomplicated future transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).

5. Introduction of new nomenclature for a common language amongst Cardiac Surgeons and Cardiologists.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection Criteria

Single center and single surgeon experience in 100 consecutive adult cardiac surgery patients operated for aortic stenosis between 2020 and 2024. Aortic regurgitation (AR), emergency surgery, infective endocarditis (IE), multiple valve disease (MVD), left ventricular myomectomy and aortic surgery cases were excluded.

2.2. Study Design

A prospective review was conducted over the last four years identifying 100 patients to study an evolving surgical strategy in a high-volume center in the United Kingdom. Through a single point of referral, patients were identified as SAVR candidates, of which 60% meet criteria to be discussed in a multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting prior to surgery. Patients identified at risk of PPM underwent a Heart team guided decision-making process considering patient’s metrics and targeted imaging, guiding the surgeon´s decision for the most suitable No-mismatch strategy (NMS) or lifetime valve strategy (LVS).

2.3. Data Availability and Ethical Statement

We undertook a single-center, prospective observational study, conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice guidelines. Anonymized data were obtained from the institutional database normally utilized for patient care and therefore the need for informed consent was waived by the institutional Medical Ethical Committee. Baseline, echocardiographic, operative and outcome data were collected, validated, and analyzed.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

This is a pilot study of consecutive data used as a test cohort therefore a power calculation was not required at this stage. This data however may be used to plan for validation studies for other surgeons or other centres.

Continuous variables were presented as median and interquartile range, (IQR on

Table 1 and

Table 2), and categorical data using frequency and percentage. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v30. The baseline differences for demographic and clinical variables across each group were analyzed with the non-parametric test of Kruskal-Wallis.

2.5. Methods

Authors present the following nomenclature and parameters to describe the patient’s journey from referral to discharge:

2.5.1. Single Point of Referral

Refers to the process where all aortic valve patients are triaged for SAVR or TAVI, through a disease specific single point of referral with a standard criteria for the Heart Team discussion (Appendices 1 and 2).

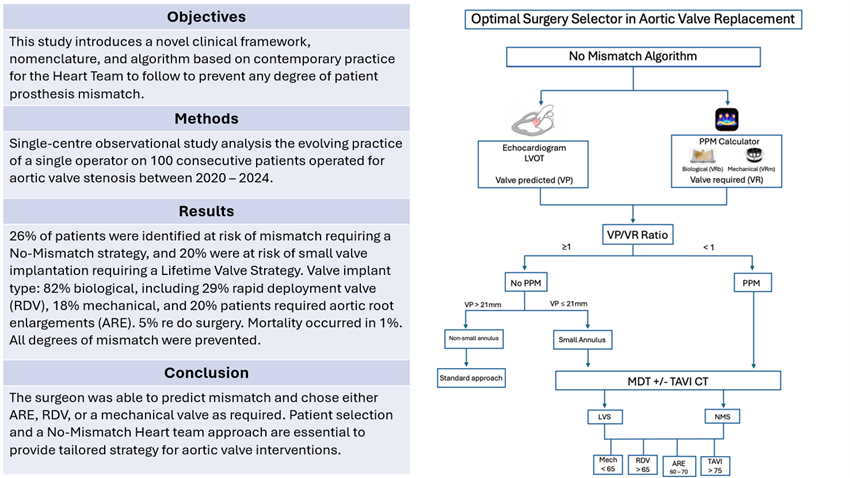

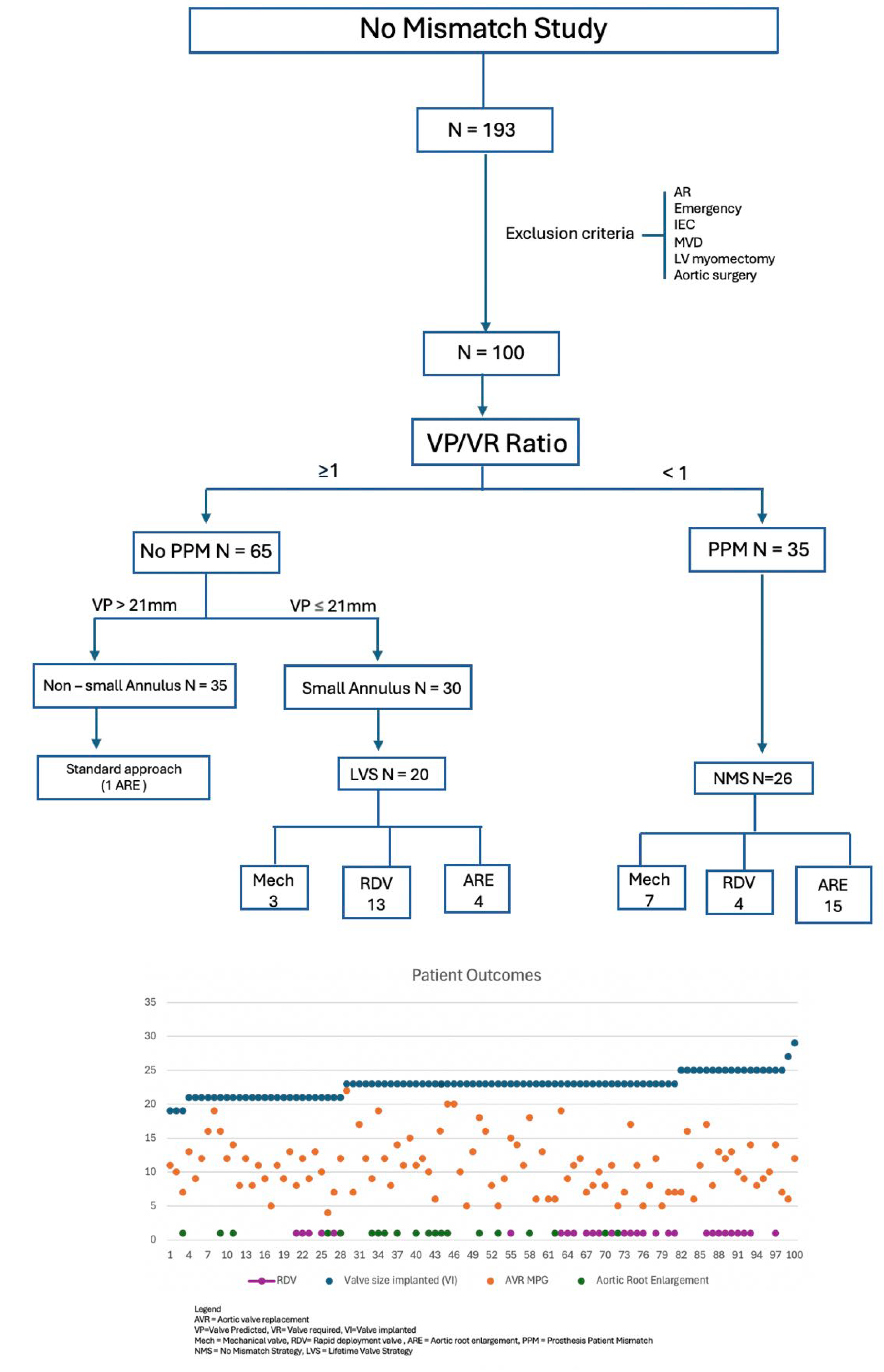

2.5.2. The No-Mismatch Algorithm

The No-Mismatch algorithm is presented in

Figure 1. The nomenclature proposed for a No-Mismatch strategy lies in the consideration of new concepts before SAVR, which are:

The Valve Predicted or VP describes the estimated valve that could fit in the LVOT as estimated by preoperative imaging.

The Valve Required or VR represents the valve provided by industry, required for the patient to avoid any degree of mismatch as assessed by the PPM calculator. This could be either biological (VRb) or mechanical (VRm). We used “Valve PPM” application, previously used in literature [

16].

The Valve Implanted or VI refers to the valve finally implanted intra-operatively.

We used a simple numerical hinge point of 1.0, where the surgeon could predict a discrepancy between the VP and the VR, suggesting a higher risk of mismatch, and recommending a No-Mismatch strategy (NMS) (

Figure 1).

Lifetime Valve Strategy (LVS) describes the event where a patient has a small root at risk of deployment of small valve (≤21mm), yet in the absence of mismatch risk. This strategy aims to address future intervention and risk of future mismatch.

This study proposes a reproducible decision process to avoid any degree of mismatch in which all SAVR patients are assessed preoperatively, categorized initially in two groups: 1- At risk of mismatch (PPM) or 2- No risk of mismatch (no PPM). Beyond this categorical classification, it also contemplates the risk of future mismatch in those whose preoperative parameters did not locate them as a mismatch risk, but present traits that can predict a mismatch in the future (small annulus, discrepancy between echo and CT scan sizes, non-standard anatomy). In those circumstances, they were offered a Lifetime Valve Strategy (LVS) to prevent mismatch with future intervention.

2.5.3. No Mismatch Algorithm Step-by-Step

The primary goal of the study is to avoid PPM. The No-Mismatch strategy is based on two key points: 1.

Prediction: identifying patients at risk of mismatch through PPM calculator and preoperative imaging studies (considering facilities and cost per center), and 2.

Prevention: through a

Heart team approach guiding the surgeon’s surgical strategy to avoid mismatch. The secondary goal of the study is to provide a

Lifetime Valve Strategy (LVS), identifying patients at risk of small valve deployment (≤21mm). Small valves in literature are associated with higher gradients, early structural valve deterioration (SVD), and poor outcomes with VIV-TAVI due to PPM [

17]. Thus, a strategy to implant larger valve should be considered after risk stratification.

The predicted mismatch lies in the discrepancy between the VP and the VR, and the real mismatch occurs in the discrepancy between VR and VI. The surgeon preoperatively assesses the risk of mismatch based on preoperative LVOT size (VP) on echocardiogram, VR from PPM calculator and finally “Ratio” assessment. Mismatch is predicted when the Ratio VP/VR < 1, and more targeted assessment of the annulus size and shape with more specific imaging including TAVI CT scan is recommended. This would also serve to identify patients with small root at risk of small valve implantation.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Patient population results can be found in

Table 1. Nine per cent of patients were aged 60 years or younger, 49% between 60 and 70, and 42% above 70. The median EuroSCORE II and Logistic EuroSCORE reflect low-moderate surgical risk. Urgent surgery was required in 51% during same in-hospital admission due to clinical presentation. The distribution of gender shows a slight male predominance (60% male, 40% female). The predominant valve pathologies were degenerative (59%) and congenital (35%), with rheumatic being rare (1%). Redo surgery was performed in 5% of patients for index valve failure (4%) or PPM (1%). After MDT discussion, 23% of the patients required CT TAVI for further assessment of the aortic root. Most patients exhibited normal sinus rhythm, 10% with atrial fibrillation or flutter, and one patient with permanent pacemaker (1%).

3.2. Intraoperative Characteristics

Intraoperative details can be found in

Table 2. Median sternotomy was performed in 90% of cases, while 10% had partial sternotomy. Most valves implanted were biological 82% (including 28% RDV) with only 18% mechanical. Aortic root enlargement (ARE) was performed in 20% of patients (all patients received Nicks procedure). Concomitant CABG was performed in 24% of the cases. Only 2% required Intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) support for known severe left ventricular dysfunction.

The smallest valve implanted (VI) for biological and mechanical valves were 21mm and 19mm respectively. The smallest valve required (VR) to avoid any mismatch in the cohort was 19mm for both biological and mechanical valves. The median values for post operative mean pressure gradient were 11.01 mmHg, indicating effectiveness after valve surgery. The cumulative cross clamp time was 83,8 min and the cumulative bypass time was 124,8 min.

3.3. Post-Operative Characteristics

Post operative characteristics are summarized in

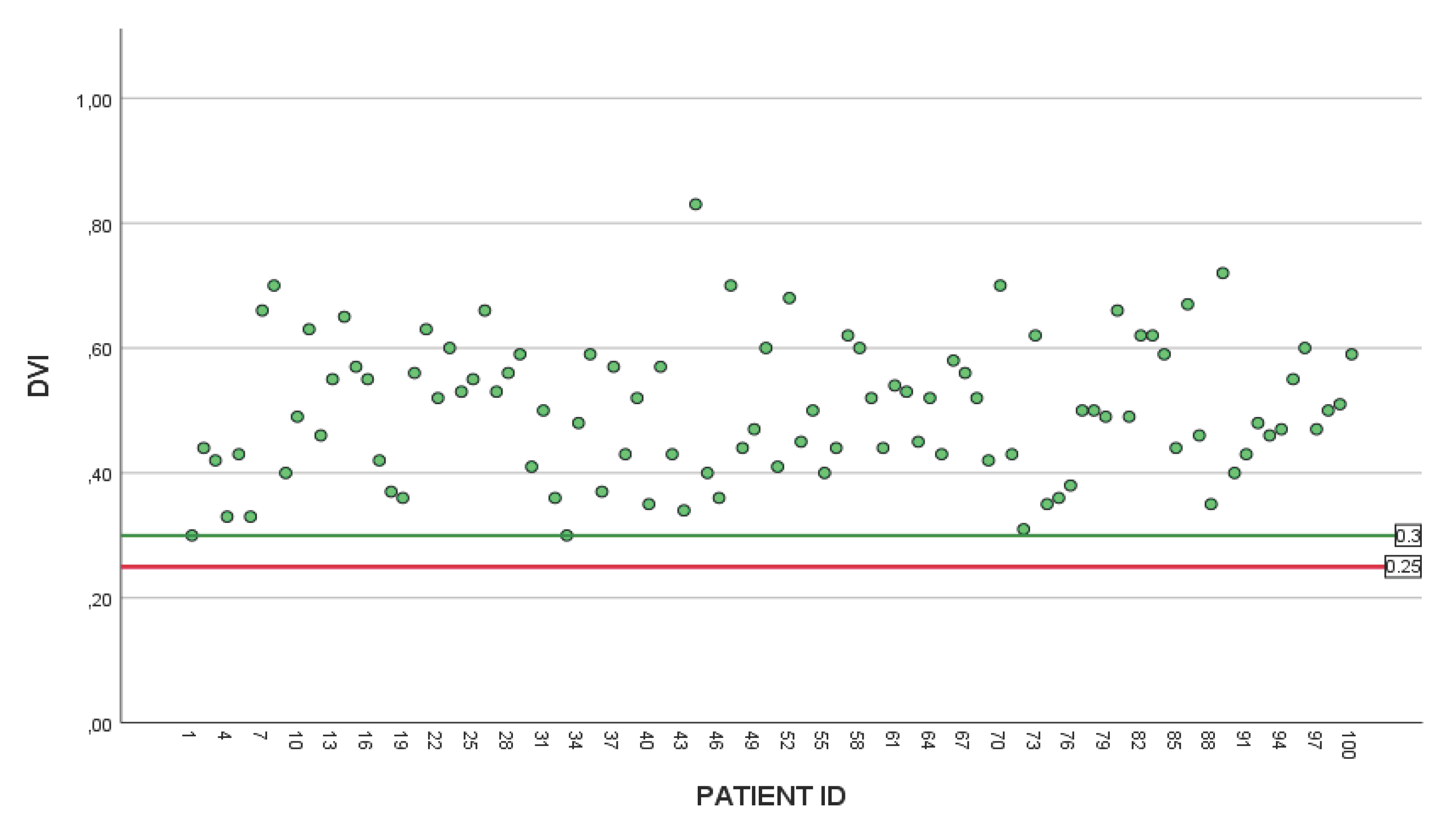

Table 3. Death occurred in one patient (1%) due to multi-organ failure. There was no post operative neurological dysfunction or stroke. Delayed drainage of pericardial effusion was required in 1%. Permanent pacing was required in 7%, new atrial fibrillation was observed in 16%, and hemofiltration for acute kidney injury (AKI) in 2%. No cases of deep sternal wound infections were reported. The median stay in hospital was 9 days. Postoperative follow up with baseline echocardiogram prior to discharge, and at 3-6 months. Post operative peak and mean gradients can be found in

Figure 2, and doppler velocity index (DVI) can be found in

Figure 3 showing no evidence of post operative mismatch.

3.4. Aortic Root Enlargement (ARE)

In our study, 20 ARE cases were identified (

Table 4), of which 4 cases represented redo surgery for index prosthetic valve failure. The decision for ARE was based mainly on preoperative assessment, and in a few instances was an intra operative decision. For the 35 cases identified at risk of mismatch (PPM group), 15 underwent ARE as the No-Mismatch strategy (NMS). However, patients whose VP/VR ratio did not predicted mismatch, intra-operative assessment of annulus size was taken into consideration, where 4 patients were offered an ARE as a lifetime valve strategy (LVS) for small aortic root.

Considering the 4 patients requiring redo surgery: Three patients had SVD (2 x 21mm and 1 x 23mm Biological valves) and 1 patient had mechanical valve failure due to pannus formation (19mm). Three patients were females, aged between 60 and 70, and the average time from index procedure to redo-surgery was 9 years.

All cases had successful ARE demonstrated by low postoperative gradients, optimal DVI measurements, improved LV function and no para-valvular leak (PVL). Implanted valve sizes are shown in

Table 4.

Postoperatively, 2 cases required pacemaker, and one patient required delayed drainage of pericardial effusion. One mortality was recorded due to multi-organ failure despite procedural success.

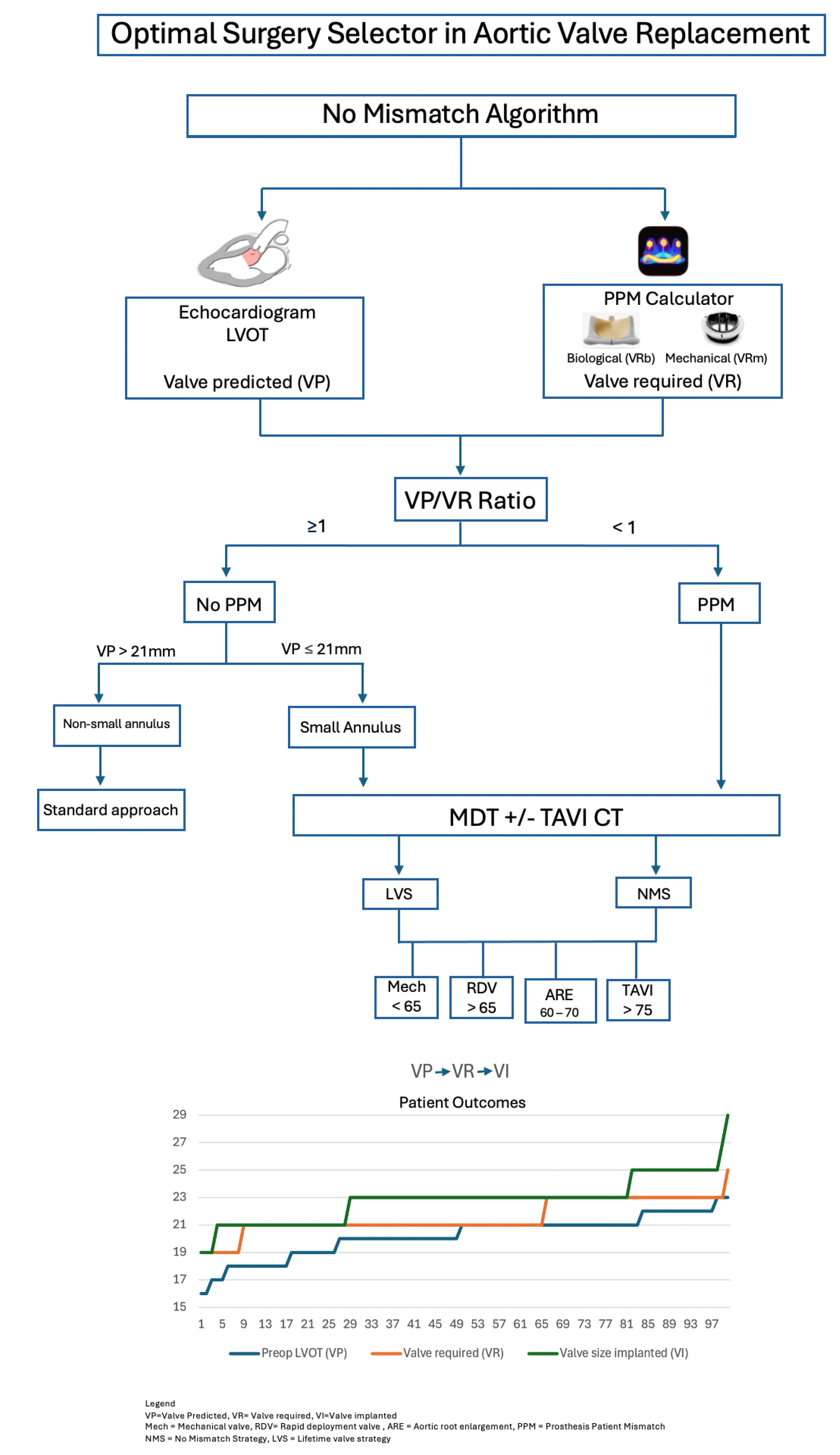

3.5. The No Mismatch Study Results

Flowchart 2 displays the total study numbers and strategies implemented. A total of 193 consecutive patients received SAVR in the designated period of 4 years. After applying exclusion criteria, the remaining 100 patients were included in the study.

The first goal of the study was to prevent mismatch. In our cohort, 35 patients were identified at a risk of PPM, with VP/VR < 1. Following preoperative assessment and MDT discussion, 26 cases required NMS (7 mechanical valves, 15 ARE, and 4 RDV)

All patients at risk of PPM (VP/VR < 1) had a small root (VP ≤ 21mm). However, not all patients with small roots had a predicted risk of mismatch. The second goal of the study is to provide a lifetime valve strategy (LVS) for patients with a small root and a negative prediction of mismatch. Sixty-five patients had a ratio ≥1representing a low risk for PPM (No PPM group), and therefore, the surgeon is likely to implant the valve required (VR) in the valve predicted area (VP) or LVOT.

As 91% of our cohort were aged > 60, and 51% aged between 60 and 70 (potential for future VIV - TAVI), the Lifetime Valve Strategy (LVS) considered mechanical valves in patients aged < 65, RDV in those aged > 65, and ARE between 60 and 70 at low surgical risk (

Figure 2). Small valve could be accepted for higher risk patients, provided no mismatch, and the valve implanted is TAVI-Friendly, i.e. internally mounted, durable, crackable or expandable, radio-opaque thus facilitating future VIV-TAVI. Considering the small annulus group (n=30) with no predicted mismatch, a Lifetime Valve Strategy (LVS) was implemented in 20 cases, including mechanical valve (3), RDV (13) and ARE (4).

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Initial analysis revealed a poor correlation between the valve predicted (VP) by the preoperative LVOT measurement and the final valve implanted (VI) (r=0.30). The estimation of the VI based on the VP measurement alone was noticed to fall short in the prediction of the correct valve to implant intraoperatively. This can be due to lack of standardization when measuring the LVOT on echocardiography, variation in annulus shape (35% bicuspid), changes in total diameter intra operatively after surgical debridement and annulus securing with pledgets or carrying out ARE.

In our initial series of the No Mismatch Algorithm, a total Intraclass Correlation Coefficient between VP and final VI was found in patients < 60 years old 0,92 (Excellent) particularly in the mechanical valves, 60 – 70 years old 0,64 (Moderate), > 70 years old 0,76 (Good).

In patients with aortic root enlargement (ARE), there were significant differences in pre op LVOT (p < 0.001), gender (p < 0.001), and final valve implanted (p < 0.001), suggesting that preoperative estimations are influenced by ARE impacting surgical planning.

Looking at the different age groups, there was a significant difference in the preoperative LVOT diameter (p=0.021), the final valve implanted VI (p=0.018), the mean pressure gradient post procedure (p=0.004), and mean peak gradient post procedure (p=0.005). Point estimates between VP and VI were calculated to evaluate how much correction the hinge point made amongst groups, finding of the 35% patients at risk of mismatch, 26% would benefit of a NMS after MDT discussion. We then recommend patients with a ratio VP/VR < 1 to be considered for 3D echo or CT TAVI scan based on availability, urgency of intervention, cost, and MDT discussion.

4. Discussion

The No Mismatch and a Lifetime Valve Strategy as a standard approach for the development of a specialist valve service is described in this study. Authors present the outcomes from a single center evolving practice implementing a Heart team strategy that can be reproducible. The tools and techniques used in this program are well accepted in current surgical practice, however the institutionalization, standardization, and combination of all the previous knowledge on that topic simplified for everyday use for the Heart team is a novel approach yet to be seen in literature.

The authors studied the difference between the final implanted valve (VI) size and preoperative predicted valve (VP) or LVOT. With the application of the NMS/LVS strategy, majority of patients (74%) received Valve Implanted (VI) larger than Valve predicted (VP), 14% received VI size equal to VP, and 12% received VI smaller than the VP. The latter could be explained by overestimation of the LVOT on echo, or the oval shape of the LVOT that had to conform to the circular structure of the stented valve implanted [

18]. In addition, following annular debridement and repair using pledgetted sutures or implanting high profile valve models with better orifice area and hemodynamic characteristics, implanted valve size may be smaller than the expected from LVOT measurement, yet PPM was still prevented.

Of paramount importance, all degrees of PPM were prevented, particularly the 26 patients identified at high risk of PPM and underwent a No-Mismatch strategy. As a measure of success, all valves implanted (VI) were larger or equal to the valves required (VR) to avoid mismatch. 82% of implanted valves were biological, and all stented biological valves were TAVI-friendly. The oldest patient receiving a mechanical valve was aged 66, avoiding lifelong anticoagulation and its associated complications at older age. All mechanical valves implanted were “Low INR” approved.

The main principle of a Lifetime Valve strategy (LVS) lies in avoiding small valves, and implanting TAVI-friendly ones especially in younger patients. Looking at implanted valve sizes, all 19mm valves were mechanical. 21 mm size valves were implanted in 24 patients, of which 8 were mechanical and 16 were biological. The decision to implant 21mm biological valves was balanced on individual risk of each case, as the majority were aged above 70, including patients turned down for TAVI, deemed anatomically unsuitable. Those patients received either a stented biological TAVI friendly valve, or a RDV with better haemodynamics in small annulus, potential platform for future TAVI [

17], and facilitated implantation through partial sternotomy.

The No PPM group had higher chance of valve requited (VR) accommodated in their predicted valve (VP) area or LVOT, however, a lifetime valve strategy was still considered in small annulus patients. ARE was offered in one patient in the “non -small annulus” arm of the flowchart, and four patients in the “small annulus” group, reflecting the effect of intraoperative assessment of annulus size on surgical decision, or the individual tailored decision for some patients.

This cohort presented a 7% rate of post operative pacemaker. This is in the context of 35% presenting with bicuspid aortic valve, in addition to 29% who received RDV, both associated with higher rate of postoperative pacemaker in literature [

18].

We introduced the use of rapid deployment valve in this study backing this practice with previous evidence highlighting the benefits of their use in a small annulus [

19] and proving comparable outcomes of RDV with aortic root enlargement [

20].

We can foresee a future debate on how to adapt the mismatch prevention flowchart into the current TAVI workups for patients who underwent SAVR. Different bioprosthetic models seem to degenerate unpredictably. Some degeneration is relatively acute rather than, ultimately affecting patient survival. Thus, having a system to assess and correctly estimate the optimal valve required in each step of the patient’s journey goes beyond the operating room. As authors acknowledge that measuring the EOA in prosthetic valves can be challenging, we aimed to report the maximum number of available post operative echo DVI data on the 30-day post operative echo along with the measured valve gradients. (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

This study aims for maximal prevention of PPM through raising awareness, education, and training of specialists in a structured Heart team involving Cardiologists and Cardiac Surgeons. This strategy will not eradicate the risk of mismatch, and we acknowledge that in some instances a compromise would be made to accept mismatch weighing risk and benefit.

The message behind the No Mismatch study extends beyond the largest possible valve for a patient’s anatomy, to simply the optimal valve required for a patient to avoid PPM, provide good flow dynamics, and accommodate a future TAVI as required. This approach can be used as a proposal by any cardiac surgeon in any cardiac unit, seeking the simplest procedure possible to ensure lifetime valve management. No-Mismatch strategy emphasizes safety in the surgical decision-making process, over single surgeon’s specific technique or expertise.

Study Limitations

The study is limited by small cohort, single centre, and single surgeon strategy. The novelty of this approach is aiming to avoid any degree of mismatch, yet long-term data is still awaited. The evolution of different surgical techniques makes this study a collection in a rapidly moving field (for instance, the introduction of rapid deployment valves, the expansion of aortic root enlargement cases in addition to surgical sub-specialization) making it difficult to compare to previous surgical practices. The study is also limited by the lack of standardization of the LVOT measurements in current literature. This cohort follows the LVOT measurements as reported by cardiac physiologists at its potential inter-observer bias. We recognize the limited data on VIV-in-RDV, and further studies of long-term outcomes will be required to provide better insight.

5. Conclusions

The results of our initial 100 cases emphasize the current need for developing personalized approach in aortic valve surgery. Patient selection, Heart valve team MDT, No-Mismatch and Lifetime Valve strategies are key to develop a patient specific approach prior to aortic valve replacement and can significantly avoid PPM. Larger studies and long-term data are required to implement similar patient centered strategies.

Appendix 1. Single Point of Referral for Aortic Valve In-Patients (SPR)Appendix 2. Significant Comorbidities

| Definitions |

Single Point of Referral (SPR)– refers to the process where all patients are referred through a disease specific single-entry portal.

SAVR pathway – patients referred and triaged to Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR) pathway.

TAVI pathway – patients referred and triaged to Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) pathway.

Joint SAVR / TAVI pathway – patients referred and triaged who are potentially suitable for either SAVR or TAVI.

Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) – forum consisting of the heart team where patients’ cases are discussed to determine optimal treatment. |

| Referring |

All in-patients with aortic valve disease requiring treatment should be referred through the assigned electronical system.

Cardiac images will be provided at time of referral.

All in-patient aortic valve referrals will be entered into Cardiac Database by the administrative team. |

| Clinical Triage |

A cardiac valve CNS and a cardiac surgery scheduler will triage referrals.

Patients suitable for SAVR pathway:

<74 years

Clinical Frailty Score (CFS) 1-4

Or

Infective endocarditis requiring operative treatment

Patients suitable for TAVI pathway:

>75 years

Or

<74 years with the following comorbidities (Appendix 2*):

Significant lung disease

Significant renal impairment

Significant bleeding disorder

Significant frailty

Malignancy requiring urgent curative treatment

Previous CABG

Previous stroke with residual neuro deficits

Elevated BMI

Patients suitable for joint SAVR / TAVI pathway:

70-74 - strong TAVI preference / degenerated tAVR

>75 - Bicuspid valves / coronary artery disease

Patients will be assessed jointly for SAVR / TAVI suitability and will be discussed at the MDT.

Patients turned down for surgery to be discussed at MDT prior to discharge to referring hospital.

|

| Appendix 2 |

Significant comorbidities:

eGFR < 30

BMI >45

liver cirrhosis with abnormal LFTs

Frailty CFS >5 |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Walid Elmahdy and Brianda Ripoll; Methodology, Walid Elmahdy and Brianda Ripoll; Validation, Brianda Ripoll; Formal analysis, Brianda Ripoll; Data curation, Walid Elmahdy and Brianda Ripoll; Writing – original draft, Brianda Ripoll; Writing – review & editing, Walid Elmahdy and Brianda Ripoll; Visualization, Mohamed Sherif, Yama Haqzad, Ahmed Omran, James O'Neill and Christopher Malkin; Supervision, Dominik Schlosshan; Project administration, Walid Elmahdy and Brianda Ripoll. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Leeds Heart Team, patients and professionals.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts to report.

Appendix

References

- Rayol S da C, Sá MPBO, Cavalcanti LRP, Saragiotto FAS, Diniz RGS, Sá FBC de A e, et al. Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch after Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement: Neither Uncommon nor Harmless. Braz J Cardiovasc Surg 2019;34:361–5.

- Sá MP, Jacquemyn X, Van den Eynde J, Chu D, Serna-Gallegos D, Ebels T, et al. Impact of Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch After Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Reconstructed Time-to-Event Data of 122 989 Patients With 592 952 Patient-Years. J Am Heart Assoc Wiley 2024;13:e033176.

- Elmahdy W, Osman M, Farag M, Shoaib A, Saad H, Sullivan K, et al. Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch Increases Early and Late Mortality in Low Risk Aortic Valve Replacement. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021;33:23–30.

- Matkovic M, Aleksic N, Bilbija I, Antic A, Lazovic JM, Cubrilo M, et al. Clinical Impact of Patient-Prosthesis Mismatch After Aortic Valve Replacement With a Mechanical or Biological Prosthesis. Tex Heart Inst J 2023;50:e228048.

- Head SJ, Mokhles MM, Osnabrugge RLJ, Pibarot P, Mack MJ, Takkenberg JJM, et al. The impact of prosthesis-patient mismatch on long-term survival after aortic valve replacement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 34 observational studies comprising 27 186 patients with 133 141 patient-years. Eur Heart J 2012;33:1518–29.

- Blais C, Dumesnil JG, Baillot R, Simard S, Doyle D, Pibarot P. Impact of valve prosthesis-patient mismatch on short-term mortality after aortic valve replacement. Circulation 2003;108:983–8.

- Flameng W, Herregods M-C, Vercalsteren M, Herijgers P, Bogaerts K, Meuris B. Prosthesis-patient mismatch predicts structural valve degeneration in bioprosthetic heart valves. Circulation 2010;121:2123–9.

- 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease | European Heart Journal | Oxford Academic. [accessed 2024].Available from https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/article/38/36/2739/4095039.

- Rahimtoola, SH. The problem of valve prosthesis-patient mismatch. Circulation 1978;58:20–4.

- Pibarot P, Clavel M-A, Dahou A. Patient and procedure selection for the prevention of prosthesis-patient mismatch following aortic valve replacement. [accessed 2024].Available from https://eurointervention.pcronline.com/article/patient-and-procedure-selection-for-the-prevention-of-prosthesis-patient-mismatch-following-aortic-valve-replacement.

- Pibarot P, Dumesnil JG. Prosthesis-patient mismatch: definition, clinical impact, and prevention. Heart Br Card Soc 2006;92:1022–9.

- Pibarot P, Dumesnil JG. Valve prosthesis-patient mismatch, 1978 to 2011: from original concept to compelling evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1136–9.

- Vriesendorp M, Groenwold R, Herrmann H, Head S, Wijngaarden R, Vriesendorp P, et al. The Clinical Implications of Body Surface Area as a Poor Proxy for Cardiac Output. Struct Heart 2021;5.

- Urso S, Sadaba R, Aldamiz-Echevarria G. Is patient-prosthesis mismatch an independent risk factor for early and mid-term overall mortality in adult patients undergoing aortic valve replacement? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2009;9:510–8.

- Sakamoto Y, Yoshitake M, Naganuma H, Kawada N, Kinouchi K, Hashimoto K. Reconsideration of patient-prosthesis mismatch definition from the valve indexed effective orifice area. Ann Thorac Surg 2010;89:1951–5.

- Cibin G, D’Onofrio A, Lorenzoni G, Lombardi V, Bergonzoni E, Fabozzo A, et al. Predicted vs. Observed Prosthesis–Patient Mismatch After Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement. Medicina (Mex) 2025;61:743.

- Landes U, Dvir D, Schoels W, Tron C, Ensminger S, Simonato M, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve-in-valve implantation in degenerative rapid deployment bioprostheses. EuroIntervention J Eur Collab Work Group Interv Cardiol Eur Soc Cardiol 2019;15:37–43.

- Guglielmetti L, Nazif T, Sorabella R, Akkoc D, Kantor A, Gomez A, et al. Bicuspid aortic valve increases risk of permanent pacemaker implant following aortic root replacement. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg Off J Eur Assoc Cardio-Thorac Surg 2016;50:497–503.

- Fiore A, Gueldich M, Folliguet T. Sutureless valves fit/perform well in a small aortic annulus. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2020;9:414–6.

- Agarwal R, Arnav A, Ranjan A, Mudgal S, Singh D. Sutureless valves versus aortic root enlargement for aortic valve replacement in small aortic annulus: A systematic review and pooled analysis. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 2023;31:524–32.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).