1. Introduction

Current guidelines recommend performing preventive aortic surgery at a maximum aortic diameter of ≥55 mm in patients without risk factors, >50 mm in patients with risk factors and ≥45 mm in those patients with other indications for cardiac surgery (most commonly, in fact, aortic valve procedures) or in case of concomitant Bicuspid Aortic Valve (BAV) [

1].

Regarding patients with an ascending aorta that has a diameter between 40mm and 44mm and a Fazel cluster II & III [

2] phenotype, which represent our target population in this study, including patients with a clearly dilated aorta (normal diameter 22 - 36mm), the treatment is contradictory: some observational studies favor a radical replacement of all ascending aortas during Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (SAVR) in patients with bicuspid aortic valve [

3,

4], while other studies suggest a more conservative attitude based on the size of the aorta [

5,

6].

Current guidelines indicate routine monitoring with cardiovascular imaging studies such as echocardiogram [

7], computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [

8] when patients have an aorta diameter within this range (40 - 44mm).

However, there is a contradictory attitude towards this approach on the part of several researchers, in fact some authors have reported a high risk of aneurysm or dissection of the ascending aorta in patients with BAV who have not undergone preventive repair of the ascending aorta at the time of the AVR [

9].

The aim of this study is to establish the most effective approach for determining and managing the evolution of aortic diameter in patients falling within the "gray area" (≥40 & <45mm) during aortic valve replacement for bicuspid aortic valve.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Ours is a retrospective observational study of a single center that includes all patients undergoing aortic valve replacement at the cardiac surgery department of AOU Federico II between January 2012 and December 2018. The time frame was chosen to provide at least a 5-year follow-up period and to present midterm results.

Aortic valve anatomy and pathology were defined using transthoracic (TTE) or transesophageal (TEE) color Doppler ultrasound; as the use of computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was not taken into consideration; patients had a BAV documented preoperatively, and measurements of the aortic root and ascending aorta were obtained by transthoracic echocardiographic or transesophageal techniques.

The patients in whom the data was obtained using CT scans, echocardiographic measurements performed by our operators were compared, the values were found to be similar.

All aortic valve replacements in patients with bicuspid aortic valve associated with aortic dilation less than 45mm were included; however, patients who were younger than 18 years of age, ascending aorta dimensions greater than or equal to 45mm or patients with an undocumented ascending thoracic aorta diameter were excluded.

The expected follow-up at one month, six months and then annually thereafter included physical examination of the patient and the performance of thoracic echocardiography (TTE) color Doppler or transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and/or CT angiography in certain cases; therefore, also using the same imaging technique used preoperatively during follow-up.

The primary endpoints were survival, reoperation rate and annual dilatation rate of the ascending aorta.

2.2. Patient Selection

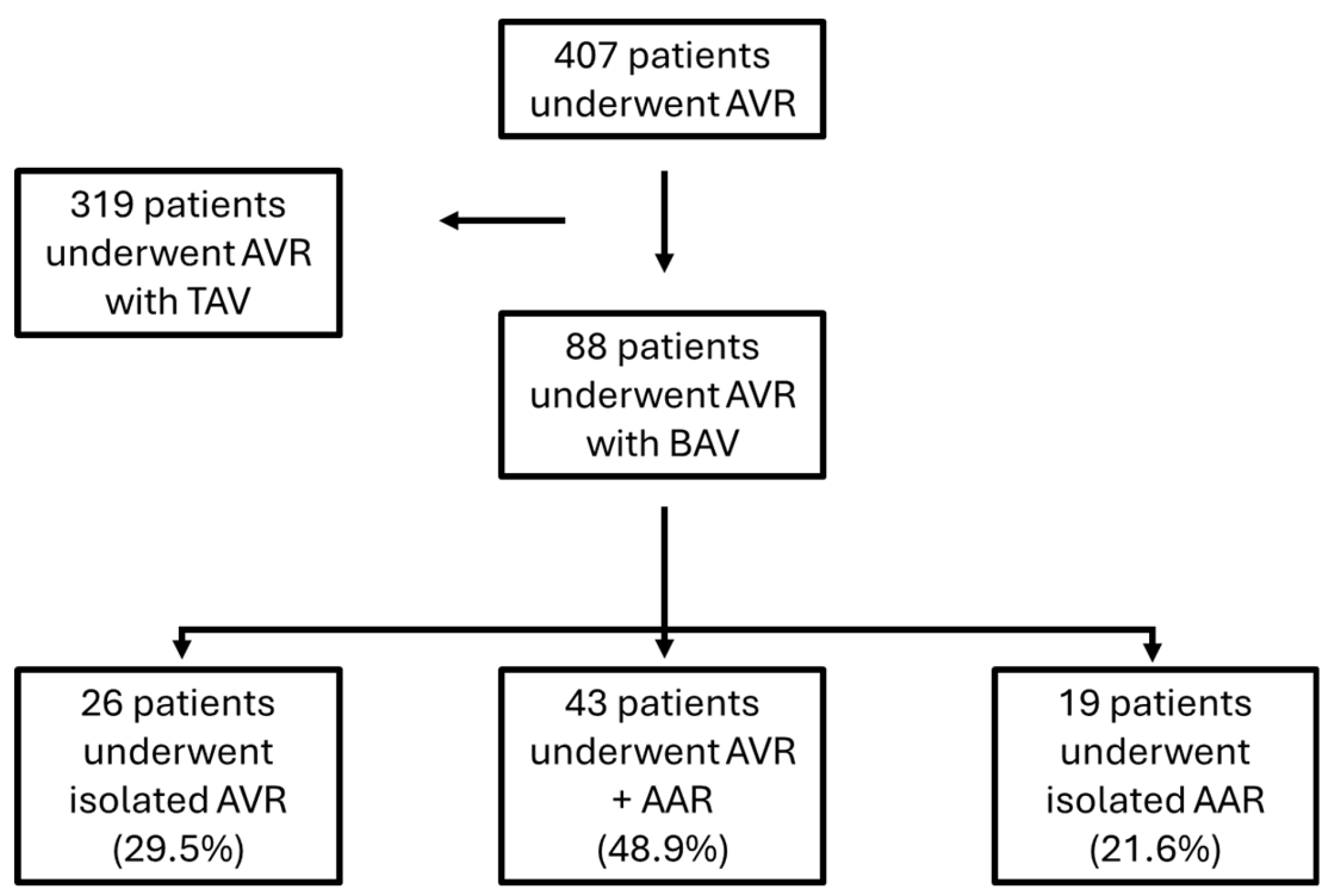

From January 2012 to December 2018 in our department 407 patients underwent aortic valve replacement surgery, of which 88 patients for BAV related pathology.

Of these 88 patients with BAV: 26 patients (29.5%) underwent isolated aortic valve replacement surgery (AVR), 43 (48.9%) underwent aortic valve replacement surgery + concomitant ascending aorta replacement while 19 patients (21.6%) underwent surgery to replace the ascending aorta only (

Figure 1).

Recently, international aorta experts developed a consensus statement on nomenclature and classification of BAV and BAVA: The valve should be described as ‘fused’, ‘2-sinus’ or ‘partial-fusion’ type, whereas the aortopathy has been classified as ‘root phenotype’ (15–20% cases, dilatation prevailing at the level of the sinuses), ‘ascending phenotype’ (70–75%, dilatation prevailing at the tubular tract) or ‘extended phenotypes’ (5–10%, either root dilatation with significant extension into the tubular tract or tubular dilatation involving also the proximal arch)[

10]. Both root and ascending phenotypes can evolve to extended phenotype in time [

1].

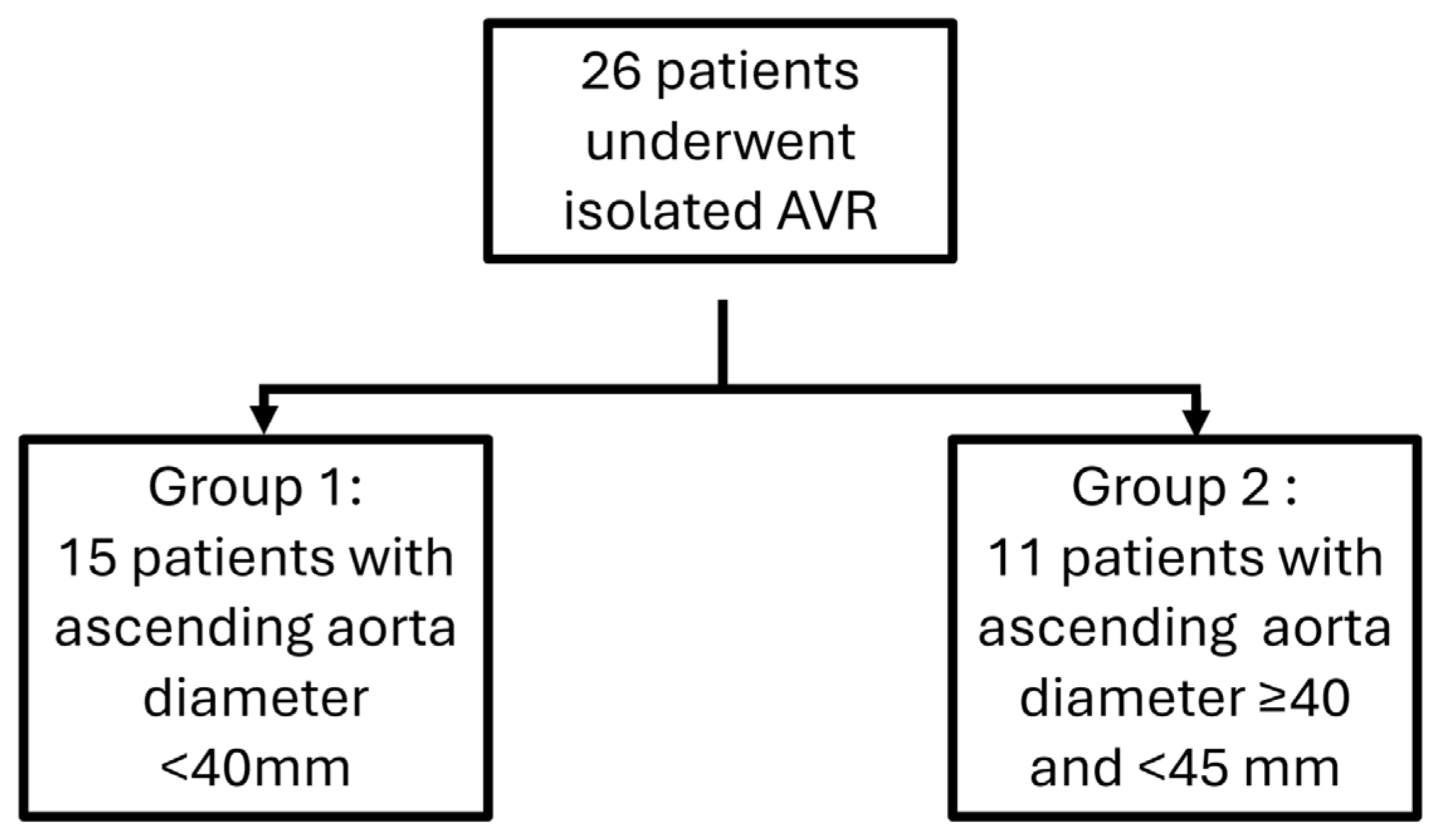

Because at the moment of surgery, guidelines didn’t distinguish aortic root dilation from tubular ascending aorta dilation, we divided the 26 patients who underwent isolated aortic valve replacement (AVR) surgery into two groups based on the diameter size of the ascending aorta. in the preoperative period, combining both patients with a root phenotype and those with an ascending phenotype: a first group comprising 15 patients with aorta diameter <40mm versus a group comprising 11 patients presenting with dilatation of the ascending aorta with a diameter of the latter being greater than or equal to 40mm and less than 45mm (

Figure 2).

2.3. Data Collection

Data were extracted from hospital registers and medical records of the Cardiac Surgery department of the Federico II University Hospital of Naples, in reference to aortic valve replacement surgeries performed between January 2012 and December 2018. The data collection included demographic information, patient comorbidities, echocardiographic imaging studies with measurement of the maximum diameter of the aortic root and ascending aorta. Follow-up data included incidences of reoperation and all cause mortality collected during follow-up visits or through phone contact with the treating physician.

Comorbidities include systemic arterial hypertension (>140mmHg/90mmHg; use of antihypertensive drugs), diabetes mellitus, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiac disease (myocardial infarction, angina, heart failure and/or atrial fibrillation), previous cardiac surgery and renal failure (level of creatinine >150 mmol/L).

Major complications were defined as: prosthesis malfunction, major bleeding (bleeding requiring surgical intervention), cardiac complications (myocardial infarction diagnosed by EKG and/or elevated cardiac enzymes), stroke (diagnosed by CT), acute renal failure (1.5-fold increase in baseline creatinine values), paraplegia (partial, complete or indefinite), pulmonary complications and 30-days all cause mortality.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables were summarized and presented using mean, standard deviation, range, and/or median. Categorical variables are presented with proportions.

Comparisons between continuous variables were performed with Student's t test, Mann-Whitney U test, or one-way analysis of variance. Comparison between categorical variables was performed with the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test (for sparse data); P values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The analysis of survival and annual growth rate of the ascending aorta were analyzed with the Kaplan-Meier test and the comparison and distribution between two different populations was performed with the Long-Rank Test (Cox-Mantel).

To evaluate predictors of long-term outcomes, P values less than 0.05 are considered statistically significant.

Data were analyzed by SPSS version 14.0 for Windows (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA).

3. Results

The patients observed in this study came to our attention symptomatic due to aortic valve dysfunction (aortic stenosis, aortic insufficiency and in some cases endocarditis) and after echocardiography it was also possible to observe the presence of the BAV and the degree of dilation of the thoracic aorta associated with it.

Between January 2012 and December 2018, 26 patients with BAV for aortic valve replacement were treated: 19 males (73.0%) and 7 females (27.0%) with an average age of 52.8 ± 12.2 years. The data relating to the two groups are shown in

Table 1.

In total 26 patients: 21 had aortic stenosis (13 from the first group and 8 from the second); 1 endocarditis on aortic valve (one from group 1); 4 aortic regurgitation (1 from the first group and 3 from the second group) (

Table 1)

All patients underwent an echocardiographic examination upon admission, with an average diameter of the aorta in the affected segment of 38.3±4.9 mm, with a value of 34.5±2.6mm in the first group and 43.4±1.5mm in the second group.

During the follow-up period of 8.8 ± 3.3 years (range from 5.5 to 12.1 years) no need for reoperation was found in any of the patients involved in the study.

The annual dilation rates assessed with TTE and/or CT scans during the follow-up period was 0.2±0.07 mm/year overall, with a rate of 0.2±0.06 in the first group and 0.3±0.09 in the second group (p=0.002); A calculated dilation of 2.4±0.8mm overall, by measuring 2.3±0.7 mm in the first group and 2.5±0.8 mm in the second group (

Table 3).

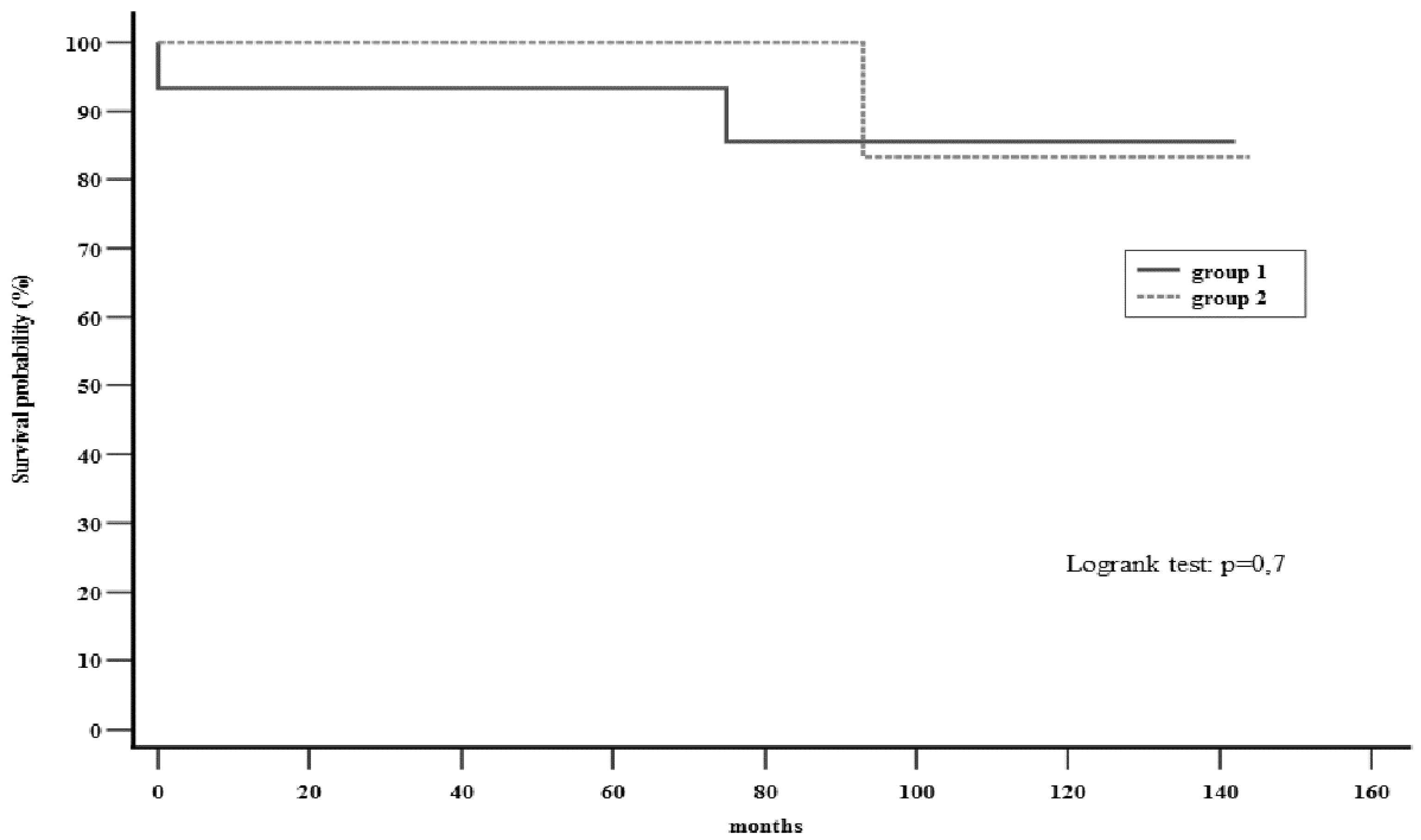

The survival rate was found to be 86.7% and 81.8% in the first and second groups, respectively. This included 1 case (6.7%) in group 1 and no cases in group 2 of in-hospital mortality (

Table 2). One case (6.7%) in group 1 and 2 cases (18.2%) in group 2 (of which only one was cardiac related) of long-term mortality were also encountered (

Table 3) (

Figure 3).

Table 2.

Perioperative results including choice of prostheses.

Table 2.

Perioperative results including choice of prostheses.

| |

All Patients

(n = 26) |

Group 1

(n = 15) |

Group 2

(n = 11) |

p |

| Mechanical Prosthesis, n (%) |

18 (69.2%) |

11 (73.3%) |

7 (63.6%) |

n.s. |

| In-hospital Mortality, n (%) |

1 (3.8%) |

1 (6.7%) |

---- |

n.s. |

Table 3.

Long-term results. follow-up 8.8 ± 3.3 years (5.5 to 12.1 years).

Table 3.

Long-term results. follow-up 8.8 ± 3.3 years (5.5 to 12.1 years).

| |

All Patients

(n = 26) |

Group 1

(n=15) |

Group 2

(n=11) |

P |

| Long-term Mortality, n (%) |

3 (11.5%) |

1 (6.7%) |

2 (18.2%) |

n.s. |

| └> Cardiac related, n (%) |

2 (7.7%) |

1 (6.7%) |

1 (9.1%) |

n.s. |

| Reoperation, n (%) |

---- |

---- |

---- |

n.s. |

| Aortic diameter prior to surgery (mm) |

38.3 ± 4.9 |

34.5 ± 2.6 |

43.4 ± 1.6 |

0.0001 |

| Aortic diameter at follow-up (mm) |

40.1 ± 5.1 |

36.4 ±2.8 |

45.5 ±1.1 |

0.0001 |

| Aortic dilatation (mm) |

2.4 ± 0.8 |

2.3 ± 0.7 |

2.5 ± 0.8 |

0.5 |

| Dilatation rate, (mm/year) |

0.2 ± 0.07 |

0.2 ± 0.06 |

0.3 ± 0.09 |

0.002 |

4. Discussion

Bicuspid aortic valve is a congenital anomaly present in 1-2% of the general population [

12] and is frequently encountered in cardiac surgery. Although the most common surgical approach is aortic valve replacement (AVR) for aortic stenosis or regurgitation, it is widely recognized that approximately 40-60% of patients with bicuspid disease also develop varying degrees of dilatation of the ascending aorta (referred to as “bicuspid aortic valve aortopathy (BAVA)” [

11,

12,

13]. BAV has a prevalence of around 30% of all surgical AVR procedures [

14] which is in line with our findings.

BAVA can cause complications in the long run with high mortality and morbidity, thus representing a notable risk factor for both the progressive dilatation of the ascending aorta (and possible rupture) and for aortic dissection with a mortality ranging from 50% to 76% [

11,

12,

13].

There are controversial hypotheses for the mechanism by which bicuspid aortopathy (BAVA) develops. Proponents of the genetic theory argue that bicuspid aortopathy is due to an intrinsic molecular defect of the aorta and that it develops independently of the function of the valve related to gene mutations in NOTCH1, GATA5, ACTA2 and TGFBR2 [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]; in contrast, there are studies that support a primary hemodynamic basis of bicuspid aortopathy [

21,

22,

23,

24].

This controversy is reflected in the choice of the most appropriate surgical intervention: if one looks at the genetic hypothesis, aortic valve replacement would certainly not limit the progression of the aortopathy, while if one considers only the hemodynamic hypothesis, AVR should be the decisive intervention.

Some authors have reported a high risk of aneurysm or dissection of the ascending aorta in patients with BAV who did not undergo preemptive repair of the ascending aorta at the time of AVR [

3].

In contrast, Rankin et al. argued in their study that aortic root reconstruction increases mortality when compared to isolated aortic valve replacement. All 409,904 valve procedures in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons database performed between 1994 and 2003 were evaluated: overall mortality for root reconstruction for aortic aneurysms was 10.5%, for aortic dissection it was 23.7 % and for root replacement without root pathology mortality was 9.5%; simple aortic valve replacement was the lowest risk surgery with an overall mortality of 5.7%. Given the high relative risk of aortic root replacement, the study recommends this surgery for patients with root aneurysms larger than 50mm or complex dissections, discouraging inappropriate root replacement [

25].

The current indications on the management of the proximal ascending aorta are, therefore, contradictory: some observational studies favor a radical replacement of all the ascending aortas during AVR in the patient with BAV, while other studies suggest a more conservative attitude based on the size of the ascending aorta.

In the study by Russo et al. [

24] 50 patients with BAV underwent isolated AVR and then compared to a control group of 50 patients who underwent tricuspid aortic valve replacement during the same time period; in the first group there were 24 late deaths associated with acute aortic syndrome, while in the control group no patients suffered aortic events. The study therefore concluded that the incidence of late acute aortic complications in patients with bicuspid aortic valve is high and recommends a policy of prophylactic replacement even of an apparently normal or slightly dilated aorta (<45mm) at the time of valve replacement surgery.

Svensson et al. argues, however, that aggressive resection is unjustified. Among the 1810 patients recruited, 1449 underwent isolated aortic valve surgery and 361 underwent ascending aorta replacement in addition to aortic valve surgery: the freedom from aortic complications of the former group at 15 years was 43% for aortic diameters of 45mm to 49mm and 81% and 86% for aortic diameters from 40mm to under 45mm, and less than 40mm respectively. They therefore concluded that preventive repair of the aorta should be carried out when it reaches a diameter greater than 45mm, to reduce the late risk of complications [

26].

Current guidelines indicate preventive surgical intervention of the ascending aorta when it reaches diameters ≥45mm in conjunction with an aortic valve replacement procedure in patients with BAV when performed by experienced surgeons [

27]; however, the management of dilated aorta with a diameter between 40mm and 45mm, excluding the 45mm, remains controversial and routine monitoring with cardiovascular imaging studies such as echocardiogram, computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is currently indicated [

27].

Our study demonstrated that there are no statistically significant differences in reference to the dilation of the ascending aorta at follow-up in the comparison between the two groups of patients with a diameter of the ascending aorta less than 40 mm and that with a diameter between 40 and 45 mm. However, between these two groups there is a statistically significant difference in the annual growth rate of the aorta. Furthermore, in our study the incidence of late aortic complications, at a follow-up of 8.8 ± 3.3 years, is close to zero probably because current diagnostic imaging techniques and current medical therapies have significantly reduced the incidence of such complications. Ultimately, we observed that patients with BAV with dilatation of the ascending aorta between 40mm and 45mm have a similar long-term survival and reoperation rate compared to patients who preoperatively had an ascending aorta with a diameter < 40mm.

Our results are also in line with the latest studies comparing bicuspid and tricuspid valves: Girdauskas et al. support the hypothesis that the mild to moderately dilated ascending aorta (40-45mm) in bicuspid valve stenosis behaves similarly to the ascending aorta in tricuspid aortic valve (TAV) stenosis after valve replacement surgery. This study compared the risk of late aortic events after valve replacement (AVR) in 153 patients with bicuspid valve stenosis and 172 patients with tricuspid valve stenosis. Overall survival after 15 years of follow-up was 78.4% in the BAV group compared to 55.6% in the TAV group; freedom from proximal aortic surgery at 15 years post-AVR was 94.3% in the BAV group compared to 89.5% in the TAV group [

5].

5. Conclusions

Our results support the guidelines by confirming that dilated proximal ascending aorta, ranging between 40 – 45 mm (Inclusive of 40mm but not of 45mm), do not require replacement in patients with BAV undergoing valve replacement surgery; provided they are kept under control over time with close follow-up and adequate medical therapy (beta blockers and vasodilators),

In our opinion, in young patients with a dilation close to 45 mm, the possible replacement of the ascending aorta should not be completely excluded especially when you take into consideration the evolution of surgical techniques and the advancement of biomedical materials. Even if not fully foreseen by the guidelines, the increased risk of reoperation linked to the longer life expectancy and the progressive increase in the rate of dilation, a possibly lower cutoff could be applied.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by S.H, R.G., V.S., C.C., E.P., and L.D.T. The first draft of the manuscript was written by S.H., R.G. and L.D.T., and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Authors/Task Force Members, Czerny M, Grabenwöger M, et al. EACTS/STS Guidelines for Diagnosing and Treating Acute and Chronic Syndromes of the Aortic Organ. Ann Thorac Surg. Published online February 22, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fazel SS, Mallidi HR, Lee RS, et al. The aortopathy of bicuspid aortic valve disease has distinctive patterns and usually involves the transverse aortic arch. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135(4):901-907.e9072. [CrossRef]

- Russo CF, Mazzetti S, Garatti A, et al. Aortic complications after bicuspid aortic valve replacement: long-term results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(5):S1773-S1799. [CrossRef]

- Yoshioka Y, Yajima S, Sakaniwa R, et al. Does the residual aorta dilate after replacement of the bicuspid aortic valve and ascending aorta?. J Thorac Dis. 2023;15(3):994-1008. [CrossRef]

- Girdauskas E, Disha K, Borger MA, Kuntze T. Long-term prognosis of ascending aortic aneurysm after aortic valve replacement for bicuspid versus tricuspid aortic valve stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;147(1):276-282. [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, T., Shekar, P., Ivkovic, V., Longford, N. T., Huang, C. C., Sigurdsson, M. I., Neely, R. C., Yammine, M., Ejiofor, J. I., Montiero Vieira, V., Shahram, J. T., Habchi, K. M., Malzberg, G. W., Martin, P. S., Bloom, J., Isselbacher, E. M., Muehlschlegel, J. D., Bicuspid Aortic Valve Consortium (BAVCon), Sundt, T. M., 3rd, & Body, S. C. (2018). Should the dilated ascending aorta be repaired at the time of bicuspid aortic valve replacement?. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery, 53(3), 560–568. [CrossRef]

- Song, S., Seo, J., Cho, I., Hong, G. R., Ha, J. W., & Shim, C. Y. (2021). Progression and Outcomes of Non-dysfunctional Bicuspid Aortic Valve: Longitudinal Data From a Large Korean Bicuspid Aortic Valve Registry. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine, 7, 603323. [CrossRef]

- Duijnhouwer A, van den Hoven A, Merkx R, et al. Differences in Aortopathy in Patients with a Bicuspid Aortic Valve with or without Aortic Coarctation. J Clin Med. 2020;9(2):290. Published 2020 Jan 21. [CrossRef]

- Girdauskas E, Rouman M, Disha K, et al. Aortic Dissection After Previous Aortic Valve Replacement for Bicuspid Aortic Valve Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(12):1409-1411. [CrossRef]

- Michelena HI, Della Corte A, Evangelista A, et al. International consensus statement on nomenclature and classification of the congenital bicuspid aortic valve and its aortopathy, for clinical, surgical, interventional and research purposes. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2021;60(3):448-476. [CrossRef]

- Sievers HH, Sievers HL. Aortopathy in bicuspid aortic valve disease - genes or hemodynamics? or Scylla and Charybdis?. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;39(6):803-804. [CrossRef]

- Fedak PW, Verma S, David TE, Leask RL, Weisel RD, Butany J. Clinical and pathophysiological implications of a bicuspid aortic valve. Circulation. 2002;106(8):900-904. [CrossRef]

- Michelena HI, Khanna AD, Mahoney D, et al. Incidence of aortic complications in patients with bicuspid aortic valves. JAMA. 2011;306(10):1104-1112. [CrossRef]

- Kong WK, Regeer MV, Ng AC, et al. Sex Differences in Phenotypes of Bicuspid Aortic Valve and Aortopathy: Insights From a Large Multicenter, International Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(3):e005155. [CrossRef]

- Padang, R., Bannon, P. G., Jeremy, R., Richmond, D. R., Semsarian, C., Vallely, M., Wilson, M., & Yan, T. D. (2013). The genetic and molecular basis of bicuspid aortic valve associated thoracic aortopathy: a link to phenotype heterogeneity. Annals of cardiothoracic surgery, 2(1), 83–91. [CrossRef]

- McKellar SH, Tester DJ, Yagubyan M, Majumdar R, Ackerman MJ, Sundt TM 3rd. Novel NOTCH1 mutations in patients with bicuspid aortic valve disease and thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;134(2):290-296. [CrossRef]

- Padang R, Bagnall RD, Richmond DR, Bannon PG, Semsarian C. Rare non-synonymous variations in the transcriptional activation domains of GATA5 in bicuspid aortic valve disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53(2):277-281. [CrossRef]

- Matthias Bechtel JF, Noack F, Sayk F, Erasmi AW, Bartels C, Sievers HH. Histopathological grading of ascending aortic aneurysm: comparison of patients with bicuspid versus tricuspid aortic valve. J Heart Valve Dis. 2003;12(1):54-61.

- Parai JL, Masters RG, Walley VM, Stinson WA, Veinot JP. Aortic medial changes associated with bicuspid aortic valve: myth or reality?. Can J Cardiol. 1999;15(11):1233-1238.

- Bauer M, Pasic M, Meyer R, et al. Morphometric analysis of aortic media in patients with bicuspid and tricuspid aortic valve. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74(1):58-62. [CrossRef]

- den Reijer, P. M., Sallee, D., 3rd, van der Velden, P., Zaaijer, E. R., Parks, W. J., Ramamurthy, S., Robbie, T. Q., Donati, G., Lamphier, C., Beekman, R. P., & Brummer, M. E. (2010). Hemodynamic predictors of aortic dilatation in bicuspid aortic valve by velocity-encoded cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, 12(1), 4. [CrossRef]

- Hope MD, Hope TA, Crook SE, et al. 4D flow CMR in assessment of valve-related ascending aortic disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(7):781-787. [CrossRef]

- Hope MD, Hope TA, Meadows AK, et al. Bicuspid aortic valve: four-dimensional MR evaluation of ascending aortic systolic flow patterns. Radiology. 2010;255(1):53-61. [CrossRef]

- Hope MD, Sigovan M, Wrenn SJ, Saloner D, Dyverfeldt P. MRI hemodynamic markers of progressive bicuspid aortic valve-related aortic disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014;40(1):140-145. [CrossRef]

- Rankin JS, Hammill BG, Ferguson TB Jr, et al. Determinants of operative mortality in valvular heart surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131(3):547-557. [CrossRef]

- Svensson LG, Kim KH, Blackstone EH, et al. Bicuspid aortic valve surgery with proactive ascending aorta repair. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142(3):622-629.e6293. [CrossRef]

- Isselbacher EM, Preventza O, Hamilton Black J 3rd, et al. 2022 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Aortic Disease: A Report of the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;146(24):e334-e482. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).