Submitted:

17 November 2025

Posted:

18 November 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

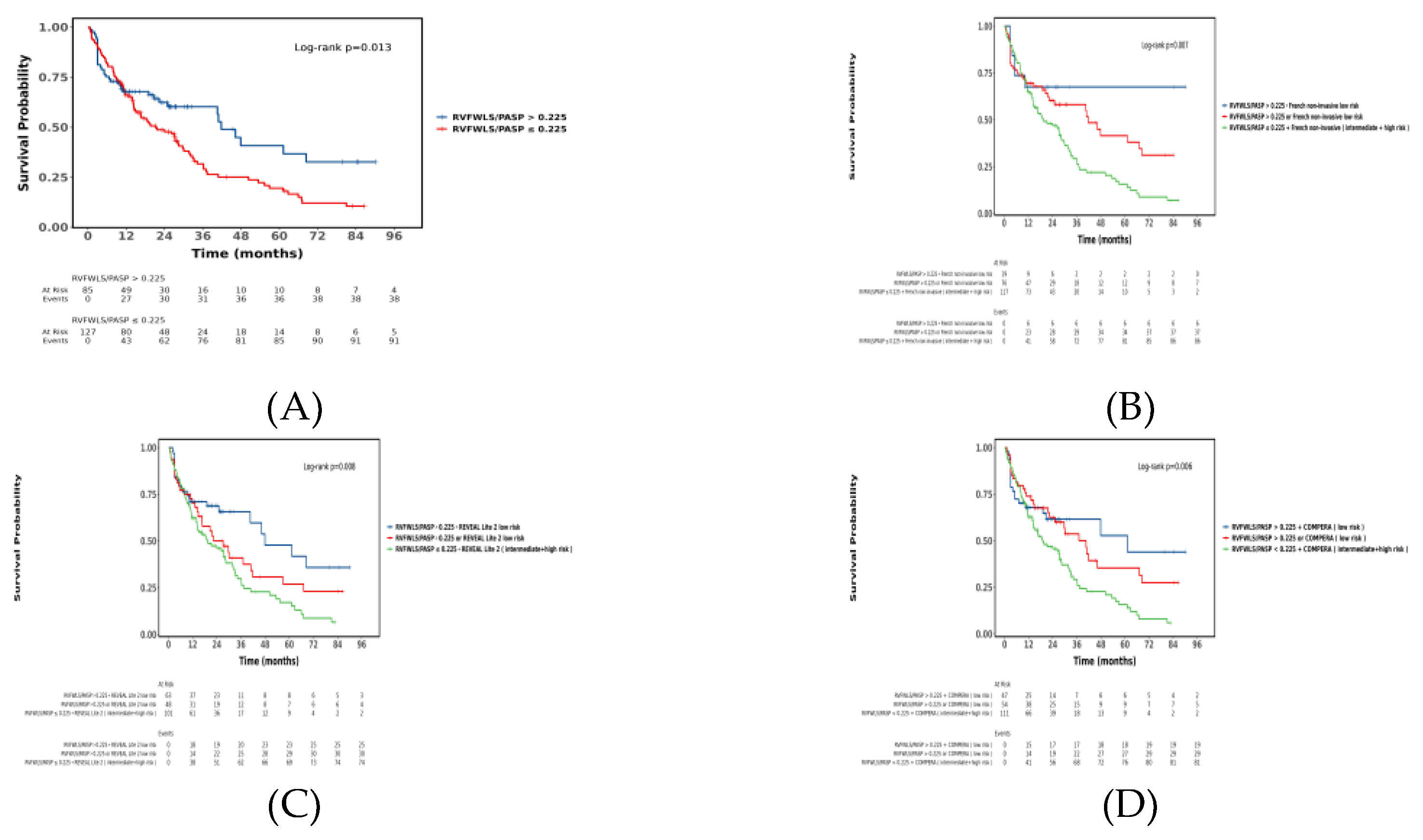

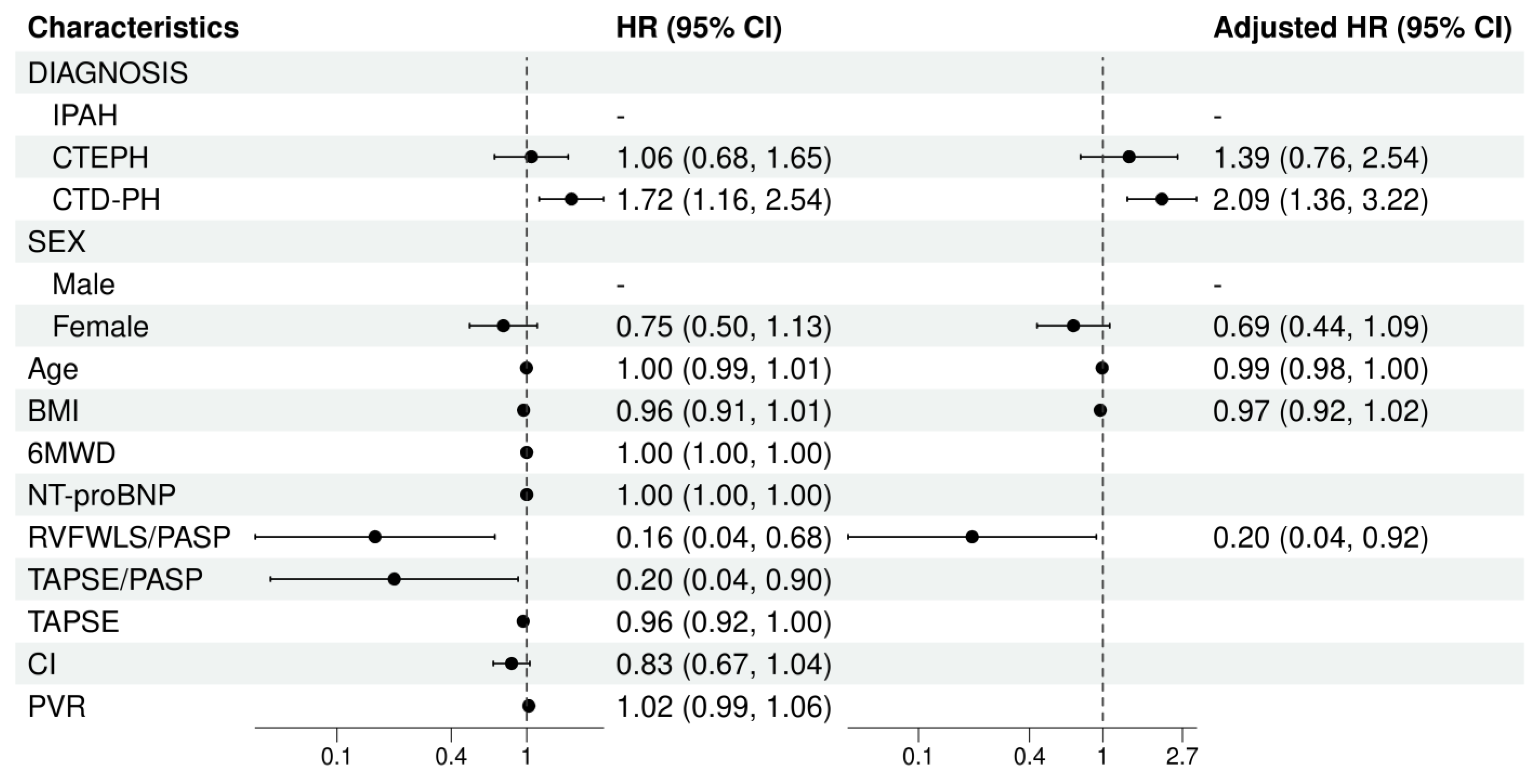

Background: The Right Ventricular Free Wall Longitudinal Strain/Pulmonary Arterial Systolic Pressure (RVFWLS/PASP) ratio is a novel echocardiographic parameter for assessing right ventricular–pulmonary artery (RV-PA) coupling. Its prognostic role in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) remains poorly defined. This study aimed to explore the prognostic value of RVFWLS/PASP in PAH. Methods: A retrospective cohort study was conducted involving patients with PAH at Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital and Nanyang Second People's Hospital from December 2009 to October 2024.The RVFWLS/PASP ratio is calculated, where the numerator (RVFWLS) is derived using speckle tracking echocardiography, and the denominator (PASP) is estimated based on the tricuspid regurgitation velocity. The primary endpoint was event-free survival, with events defined as all-cause mortality, lung transplantation, rehospitalization for right heart failure, or escalation of targeted therapy due to clinical deterioration. Cox regression analysis was used to identify and validate RVFWLS/PASP characteristics in patients with different outcomes. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was employed to evaluate the additive value of RVFWLS/PASP to previously established risk models. Results: A total of 216 adult PAH patients were enrolled. The median follow-up time was 31 months. The survival rate of patients in the lower RVFWLS/PASP group was significantly worse than those in the higher RVFWLS/PASP group (Log-rank P <0.05). Multivariate Cox regression demonstrated that after adjusting for other prognostic factors,RVFWLS/PASP ratio (HR = 0.20, 95% CI: 0.04-0.92, p = 0.039) and CTD-PH diagnosis (HR = 2.09, 95% CI: 1.36-3.22, p < 0.001) remained independent predictors of adverse clinical events. RVFWLS/PASP enabled further risk stratification of patients classified as low-risk by established models. Conclusion: The echocardiographic parameter RVFWLS/PASP serves as an independent determinant of long-term prognosis in patients with PAH, indicating that improved RV-PA coupling is significantly associated with better clinical outcomes. RVFWLS/PASP provides incremental value for risk stratification and may demonstrate heterogeneous utility across different clinical subgroups.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

2.2. Baseline Data Collection

2.3. Echocardiographic Measurements and Definitions

2.4. Risk Assessment Models

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

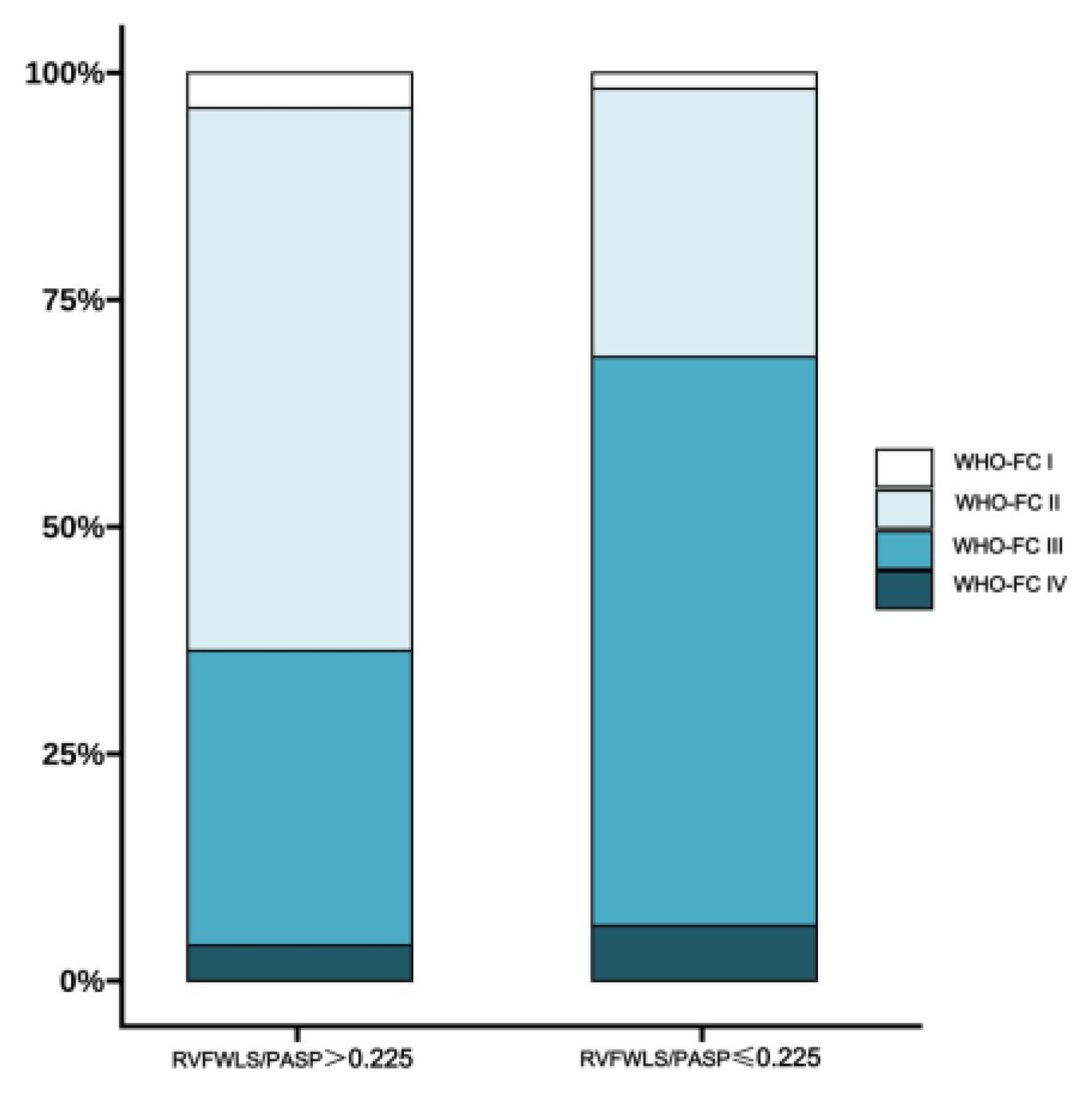

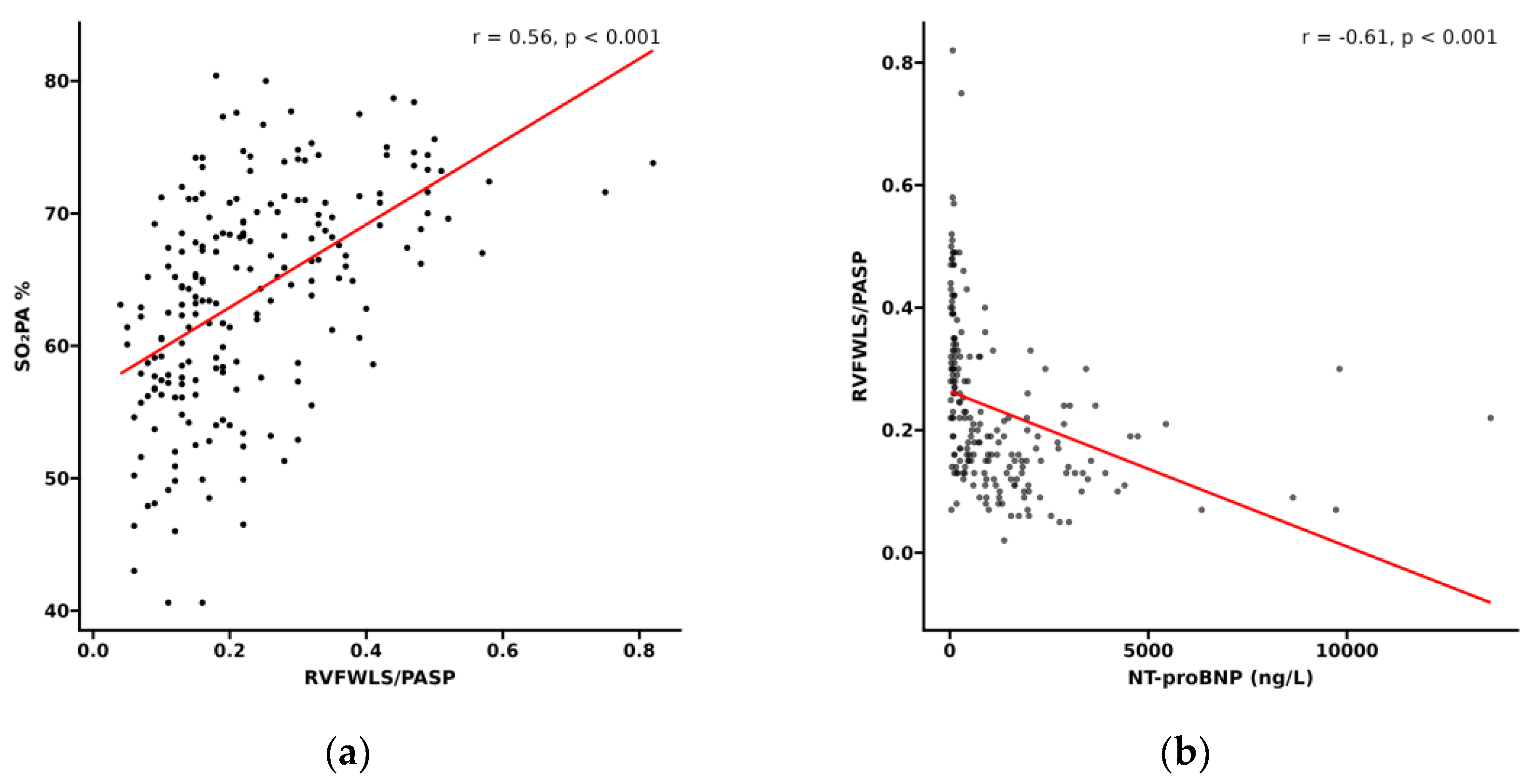

3.2. Relationship Between RVFWLS/PASP and Functional Status in PH Patients

3.3. Follow-up Results

3.4. Association Between RVFWLS/PASP and Long-term Outcomes in PAH

3.5. Incremental Value of RVFWLS/PASP in Predicting All-Cause Mortality

4. Discussion

Study Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Van Wolferen, S.A.; Marcus, J.T.; Boonstra, A.; Marques, K.M.; Bronzwaer, J.G.F.; Spreeuwenberg, M.D.; Postmus, P.; Vonk-Noordegraaf, A. Prognostic value of right ventricular mass, volume, and function in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2007, 28, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdev, A.; Villarraga, H.R.; Frantz, R.P.; McGoon, M.D.; Hsiao, J.-F.; Maalouf, J.F.; Ammash, N.M.; McCully, R.B.; Miller, F.A.; Pellikka, P.A.; et al. Right ventricular strain for prediction of survival in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Chest 2011, 139, 1299–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, R.J.; Hinderliter, A.L.; Willis, P.W.; Ralph, D.; Caldwell, E.J.; Williams, W.; A Ettinger, N.; Hill, N.S.; Summer, W.R.; de Boisblanc, B.; et al. Echocardiographic predictors of adverse outcomes in primary pulmonary hypertension. JACC 2002, 39, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noordegraaf, A.V.; Chin, K.M.; Haddad, F.; Hassoun, P.M.; Hemnes, A.R.; Hopkins, S.R.; Kawut, S.M.; Langleben, D.; Lumens, J.; Naeije, R. Pathophysiology of the right ventricle and of the pulmonary circulation in pulmonary hypertension: an update. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 53, 1801900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tunariu, N.; Gibbs, S.J.; Win, Z.; Gin-Sing, W.; Graham, A.; Gishen, P.; Al-Nahhas, A. Ventilation-perfusion scintigraphy is more sensitive than multidetector CTPA in detecting chronic thromboembolic pulmonary disease as a treatable cause of pulmonary hypertension. J. Nucl. Med. 2007, 48, 680–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoey, E.T.D.; Mirsadraee, S.; Pepke-Zaba, J.; Jenkins, D.P.; Gopalan, D.; Screaton, N.J. Dual-energy CT angiography for assessment of regional pulmonary perfusion in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: initial experience. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 196, 524–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2200879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolfo, D.; Albani, S.; Biondi, F.; De Luca, A.; Barbati, G.; Howard, L.; Giudice, F.L.; Tsampasian, V.; Pasanisi, E.M.; Airò, E.; et al. Global Right Heart Assessment with Speckle-Tracking Imaging Improves the Risk Prediction of a Validated Scoring System in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2020, 33, 1334–1344.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiè, N.; Hoeper, M.M.; Humbert, M.; Torbicki, A.; Vachiery, J.-L.; Barbera, J.A.; Beghetti, M.; Corris, P.; Gaine, S.; Gibbs, J.S.; et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS), endorsed by the International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur. Hear. J. 2009, 30, 2493–2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galié, N.; Humbert, M.; Vachiéry, J.-L.; Gibbs, S.; Lang, I.; Torbicki, A.; Simonneau, G.; Peacock, A.; Noordegraaf, A.V.; Beghetti, M.; et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 46, 903–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudski, L.G.; Lai, W.W.; Afilalo, J.; Hua, L.; Handschumacher, M.D.; Chandrasekaran, K.; Solomon, S.D.; Louie, E.K.; Schiller, N.B. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 685–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, R.J.; Hinderliter, A.L.; Willis, P.W.; Ralph, D.; Caldwell, E.J.; Williams, W.; A Ettinger, N.; Hill, N.S.; Summer, W.R.; de Boisblanc, B.; et al. Echocardiographic predictors of adverse outcomes in primary pulmonary hypertension. JACC 2002, 39, 1214–1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortuni, F.; Butcher, S.C.; Dietz, M.F.; van der Bijl, P.; Prihadi, E.A.; De Ferrari, G.M.; Marsan, N.A.; Bax, J.J.; Delgado, V. Right Ventricular–Pulmonary Arterial Coupling in Secondary Tricuspid Regurgitation. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 148, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ünlü, S.; Bézy, S.; Cvijic, M.; Duchenne, J.; Delcroix, M.; Voigt, J.-U. Right ventricular strain related to pulmonary artery pressure predicts clinical outcome in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Hear. J. - Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 24, 635–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muraru, D.; Onciul, S.; Peluso, D.; Soriani, N.; Cucchini, U.; Aruta, P.; Romeo, G.; Cavalli, G.; Iliceto, S.; Badano, L.P. Sex- and Method-Specific Reference Values for Right Ventricular Strain by 2-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 9, e003866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucly, A.; Weatherald, J.; Savale, L.; de Groote, P.; Cottin, V.; Prévot, G.; Chaouat, A.; Picard, F.; Horeau-Langlard, D.; Bourdin, A.; et al. External validation of a refined four-stratum risk assessment score from the French pulmonary hypertension registry. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 59, 2102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boucly, A.; Weatherald, J.; Savale, L.; Jaïs, X.; Cottin, V.; Prevot, G.; Picard, F.; de Groote, P.; Jevnikar, M.; Bergot, E.; et al. Risk assessment, prognosis and guideline implementation in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2017, 50, 1700889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benza, R.L.; Kanwar, M.K.; Raina, A.; Scott, J.V.; Zhao, C.L.; Selej, M.; Elliott, C.G.; Farber, H.W. Development and Validation of an Abridged Version of the REVEAL 2.0 Risk Score Calculator, REVEAL Lite 2, for Use in Patients With Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Chest 2021, 159, 337–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinojar, R.; Zamorano, J.L.; Gómez, A.G.; García-Martin, A.; Monteagudo, J.M.; Lunar, I.G.; Recalde, A.S.; Fernández-Golfín, C. Prognostic Impact of Right Ventricular Strain in Isolated Severe Tricuspid Regurgitation. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2023, 36, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hădăreanu, C.-D.; Hădăreanu, D.-R.; Toader, D.-M.; Iovănescu, M.-L.; Florescu, C.; Raicea, V.-C.; Donoiu, I. Prognostic value of the ratio between right ventricular free wall longitudinal strain and systolic pulmonary artery pressure in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction and ventricular secondary mitral regurgitation. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2025, 12, 1611772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancona, F.; Margonato, D.; Menzà, G.; Bellettini, M.; Melillo, F.; Stella, S.; Capogrosso, C.; Ingallina, G.; Biondi, F.; Boccellino, A.; et al. Ratio between right ventricular longitudinal strain and pulmonary arterial systolic pressure: A novel prognostic parameter in patients with severe tricuspid regurgitation. Int. J. Cardiol. 2023, 384, 55–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jani, V.P.; Strom, J.B.; Gami, A.; Beussink-Nelson, L.; Patel, R.; Michos, E.D.; Shah, S.J.; Freed, B.H.; Mukherjee, M. Optimal Method for Assessing Right Ventricular to Pulmonary Arterial Coupling in Older Healthy Adults: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Am. J. Cardiol. 2024, 222, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Lin, Y.; Xie, M.; Zhang, L.; Sun, W.; Deng, W.; Zhao, R.; Shi, J.; Li, W.; et al. Association of Glycemic Control With Right Ventricular Function Assessed by Two-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking and Three-Dimensional Echocardiography in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2024, 37, 1156–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabeshima, Y.; Kitano, T.; Node, K.; Takeuchi, M. Prognostic value of right ventricular free-wall longitudinal strain in patients with pulmonary hypertension: systematic review and meta-analyses. Open Hear. 2024, 11, e002561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanatta, E.; Polito, P.; Famoso, G.; Larosa, M.; De Zorzi, E.; Scarpieri, E.; Cozzi, F.; Doria, A. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in connective tissue disorders: Pathophysiology and treatment. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 244, 120–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avazmohammadi, R.; Mendiola, E.A.; Li, D.S.; Vanderslice, P.; Dixon, R.A.F.; Sacks, M.S. Interactions Between Structural Remodeling and Hypertrophy in the Right Ventricle in Response to Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. J. Biomech. Eng. 2019, 141, 0910161–09101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Mathai, S.C.; Jellis, C.; Freed, B.H.; Yanek, L.R.; Agoglia, H.; Chiu, C.; Jani, V.P.; Simpson, C.E.; Brittain, E.L.; et al. Defining Echocardiographic Degrees of Right Heart Size and Function in Pulmonary Vascular Disease From the PVDOMICS Study. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, M.; Jani, V.P.; Osgueritchian, R.; Mombeini, H.; Abidov, A.; Beck, G.; Erzurum, S.; Frantz, R.P.; Hassoun, P.M.; Hemnes, A.R.; et al. Echocardiographic Parameters and Risk Prediction in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Insights From the Redefining Pulmonary Hypertension Through Pulmonary Vascular Disease Phenomics Network. Chest 2025, 168, 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, Y.N.; Dubrock, H.; Hassoun, P.M.; Hemnes, A.; Horn, E.; Leopold, J.A.; Rischard, F.; Rosenzweig, E.B.; Hill, N.S.; Erzurum, S.C.; et al. Non-invasive prediction of pulmonary vascular disease-related exercise intolerance and survival in non-group 1 pulmonary hypertension. Eur. J. Hear. Fail. 2024, 26, 2323–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Characteristic | N = 216 |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| IPAH | 88 (40.7%) |

| CTEPH | 65 (30.1%) |

| CTD-PH | 63 (29.2%) |

| SEX, n (%) | |

| Male | 46 (21.3%) |

| Female | 170 (78.7%) |

| Age,years | 45 (32, 61) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.5 ± 3.5 |

| WHO-FC, n (%) | |

| Class I | 5 (2.6%) |

| Class II | 82 (41.8%) |

| Class III | 99 (50.5%) |

| Class IV | 10 (5.1%) |

| 6MWD, m | 405 (320, 470) |

| NT-proBNP, ng/L | 508 (113, 1,630) |

| RVFWLS/PASP | 0.19 (0.13, 0.31) |

| TAPSE/PASP | 0.25 (0.18, 0.34) |

| RVGLS/PASP | 0.18 (0.12, 0.28) |

| TR Severity, n (%) | |

| Trace | 25 (12.8%) |

| Mild | 82 (42.3%) |

| Moderate | 38 (19.6%) |

| Severe | 49 (25.3%) |

| TAPSE,mm | 17.0 (15.0, 20.0) |

| FAC, % | 23 (16, 32) |

| RA area, cm2 | 18 (14, 22) |

| RVMD, cm | 3.40 (2.90, 4.00) |

| LV-EId | 1.24 (1.08, 1.46) |

| LVEDD, cm | 3.92 ± 0.72 |

| LVEF,% | 75 (68, 82) |

| E/e' | 6.43 (4.80, 8.22) |

| mPAP, mmHg | 47 ± 14 |

| PAWP, mmHg | 7.0 (4.0, 10.0) |

| PVR, Woods units | 9.2 (6.3, 13.4) |

| CI, L/min/m2 | 2.80 (2.23, 3.29) |

| Characteristic | RVFWLS/PASP >0.225 N = 85 |

RVFWLS/PASP ≤0.225 N = 127 |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.639 | |||

| IPAH | 32 (37.6%) | 55 (43.3%) | ||

| CTEPH | 28 (32.9%) | 35 (27.6%) | ||

| CTD-PH | 25 (29.4%) | 37 (29.1%) | ||

| SEX, n (%) | 0.242 | |||

| Male | 15 (17.6%) | 31 (24.4%) | ||

| Female | 70 (82.4%) | 96 (75.6%) | ||

| Age,years | 43 (34, 60) | 45 (31, 62) | 0.733 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.9 ± 3.3 | 22.2 ± 3.7 | 0.174 | |

| WHO-FC, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| Class I | 3 (3.9%) | 2 (1.7%) | ||

| Class II | 46 (59.7%) | 34 (29.6%) | ||

| Class III | 25 (32.5%) | 72 (62.6%) | ||

| Class IV | 3 (3.9%) | 7 (6.1%) | ||

| 6MWD, m | 445 (400, 510) | 363 (275, 435) | <0.001 | |

| NT-proBNP, ng/L | 113 (70, 342) | 1,206 (508, 1,973) | <0.001 | |

| RVFWLS/PASP | 0.33 (0.28, 0.42) | 0.14 (0.11, 0.18) | <0.001 | |

| RVGLS/PASP | 0.30 (0.26, 0.40) | 0.13 (0.10, 0.16) | <0.001 | |

| TAPSE/PASP | 0.35 (0.28, 0.45) | 0.20 (0.16, 0.25) | <0.001 | |

| TR Severity, n (%) | <0.001 | |||

| None | 2 (2.7%) | 1 (0.8%) | ||

| Trace | 15 (20.5%) | 7 (5.9%) | ||

| Mild | 39 (53.4%) | 40 (33.9%) | ||

| Moderate | 10 (13.7%) | 28 (23.7%) | ||

| Severe | 7 (9.6%) | 42 (35.6%) | ||

| TAPSE,mm | 19.0 (17.0, 21.0) | 16.0 (14.0, 18.4) | <0.001 | |

| FAC, % | 31 (21, 39) | 19 (14, 26) | <0.001 | |

| RA area, cm2 | 16 (11, 18) | 20 (16, 24) | <0.001 | |

| RVMD, cm | 3.05 (2.50, 3.60) | 3.70 (3.30, 4.20) | <0.001 | |

| LV-EId | 1.07 (1.00, 1.21) | 1.37 (1.21, 1.56) | <0.001 | |

| LVEDD, cm | 4.26 ± 0.63 | 3.70 ± 0.67 | <0.001 | |

| LVEF,% | 73 (68, 77) | 77 (71, 84) | 0.002 | |

| E/e' | 6.24 (4.65, 7.59) | 6.60 (5.00, 8.60) | 0.190 | |

| mPAP, mmHg | 40 ± 11 | 53 ± 13 | <0.001 | |

| PAWP, mmHg | 7.5 (4.0, 10.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 9.0) | 0.231 | |

| PVR, Woods units | 6.3 (4.6, 8.7) | 11.4 (8.5, 16.4) | <0.001 | |

| CI, L/min/m2 | 3.17 (2.74, 3.62) | 2.50 (1.97, 2.97) | <0.001 | |

| Characteristic | Non-Deterioration Group N = 81 |

Deterioration Group N = 135 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| IPAH | 39 (48.1%) | 49 (36.3%) | |

| CTEPH | 33 (40.7%) | 32 (23.7%) | |

| CTD-PH | 9 (11.1%) | 54 (40.0%) | |

| SEX, n (%) | 0.668 | ||

| Male | 16 (19.8%) | 30 (22.2%) | |

| Female | 65 (80.2%) | 105 (77.8%) | |

| Age,years | 48 (34, 68) | 43 (32, 58) | 0.027 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 22.8 ± 3.1 | 22.3 ± 3.7 | 0.268 |

| WHO-FC, n (%) | 0.833 | ||

| Class I | 2 (2.7%) | 3 (2.5%) | |

| Class II | 32 (42.7%) | 50 (41.3%) | |

| Class III | 36 (48.0%) | 63 (52.1%) | |

| Class IV | 5 (6.7%) | 5 (4.1%) | |

| 6MWD, m | 410 (325, 475) | 396 (320, 465) | 0.600 |

| NT-proBNP, ng/L | 241 (78, 888) | 903 (220, 1,949) | <0.001 |

| RVFWLS/PASP | 0.26 (0.15, 0.35) | 0.18 (0.12, 0.26) | <0.001 |

| RVGLS/PASP | 0.23 (0.14, 0.34) | 0.16 (0.11, 0.23) | <0.001 |

| TAPSE/PASP | 0.28 (0.21, 0.37) | 0.23 (0.17, 0.31) | <0.001 |

| TR Severity, n (%) | 0.292 | ||

| None | 1 (1.4%) | 2 (1.7%) | |

| Trace | 10 (13.5%) | 12 (10.0%) | |

| Mild | 37 (50.0%) | 45 (37.5%) | |

| Moderate | 11 (14.9%) | 27 (22.5%) | |

| Severe | 15 (20.3%) | 34 (28.3%) | |

| TAPSE,mm | 18.0 (16.0, 20.0) | 17.0 (14.0, 19.8) | 0.024 |

| FAC, % | 25 (17, 35) | 22 (15, 31) | 0.051 |

| RA area, cm2 | 17 (13, 21) | 18 (15, 24) | 0.034 |

| RVMD, cm | 3.40 (2.70, 3.90) | 3.50 (3.10, 4.10) | 0.122 |

| LV-EId | 1.14 (1.00, 1.37) | 1.30 (1.13, 1.50) | <0.001 |

| LVEDD, cm | 4.09 ± 0.74 | 3.83 ± 0.69 | 0.011 |

| LVEF,% | 72 (66, 81) | 76 (71, 82) | 0.044 |

| E/e' | 6.90 (4.50, 9.10) | 6.27 (4.91, 8.00) | 0.403 |

| mPAP, mmHg | 45 ± 14 | 49 ± 13 | 0.033 |

| PAWP, mmHg | 8.0 (5.0, 11.0) | 6.0 (4.0, 9.0) | 0.020 |

| PVR, Woods units | 8.0 (5.4, 11.4) | 9.9 (6.9, 13.7) | 0.012 |

| CI, L/min/m2 | 2.87 (2.39, 3.39) | 2.67 (2.20, 3.23) | 0.210 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).