1. Introduction

In 2017, chronic kidney disease (CKD) was a substantial health care issue, with a global prevalence of 697.5 million cases and 1.2 million fatalities in 2017. It is widely recognized that CKD patients are at a heightened cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk [

1].

In one respect, CKD is an independent coronary artery disease (CAD) and a cardiovascular risk factor equivalent for all-cause mortality. However, CVDs could exacerbate the CKD progression to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD). [

2].

Additionally, research indicates that CVD is the primary cause of mortality in patients with CKD, particularly when the detected glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) is less than 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. The primary factors associated with an elevated mortality rate in CKD patients are ischemic heart disease and heart failure (HF), among other CVD. Furthermore, CKD is associated with a 2–3-fold increased atrial fibrillation (AF) incidence, which further elevates the cardiovascular mortality by 45% and all-cause mortality risk by 23% [

3].

left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction (LVDD) evidence is necessary for the HF diagnosis with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in the general population, even in the preclinical stage. LVDD is an independent all-cause mortality predictor [

4]

. Therefore, it is becoming increasingly crucial to accurately assess LVDD in the routine clinical practice context. The primary physiologic consequence of LVDD is increased LV filling pressures. Despite the fact that invasive methods are regarded as the "gold standard" for assessing LV filling pressures and LV diastolic function, echocardiography (Echo) is a frequently employed noninvasive choice [

4]

.

The 2016 ASE/SCAI guidelines simplify the evaluation of LV diastolic function by combining four variables into a single algorithm. However, the accuracy of the assessment will be impacted by the severe tricuspid valve lesions, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and right ventricular and low right atrial filling pressure presence. Transthoracic Echo remains necessary for an accurate LV diastolic function evaluation [

4].

The intrinsic deformation of the left atrium (LA) is directly reflected by speckle tracking, which is less influenced by the load change due to its relatively independent load environment and geometric model. It is recommended that the LA strain be employed in the LVDD diagnosis [

5].

A metric of the LA's filling and discharge is LA strain. HF with HFpEF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) has been confirmed as a diastolic dysfunction metric using LA strain. Conduit strain, reservoir strain, and booster (pump) strain are the three LA function phases that could be quantified using speckle-tracking analysis during Echo [

6].

For those who are not diagnosed with CVD, lower LA strain values (which indicate poorer LA function) are contrary outcomes indicative [

7]

, and HFpEF patients [

8]

. Despite the fact that ESRD cases are frequently prone to HFpEF and have diastolic dysfunction, LA strain could be a valuable prognostic tool for this population. However, there are minimal research on LA strain in this population.

There has been an evidence dearth regarding the distinctions in LA and LV strain and size changes across CKD stages, as well as the echocardiographic parameters that could be used to expect the GFR reject. Hence, we specifically aimed to address the role of LA strain value versus tissue Doppler Echo and the LA volume index in the LV diastolic function evaluation in CKD patients.

2. Methodology

It was a cross-sectional study done on 220 CKD patients with reference to the Cardiology department Tanta University for routine evaluation during a period of six months (April to September 2024). The anonymity of the study participants was maintained. CKD patients with EF>50% were included. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congenital heart disease, valvular heart disease, ischemic heart disease, previous myocardial dysfunction, dilated cardiomyopathy patients and EF < 50% patients were excluded. Study participants were categorized according to eGFR detected by creatinine clearance Cockcroft-gault equation into five groups; Group 1: GFR 90-120 mL/min/1.73 m2, Group2: GFR 60-90 mL/min/1.73 m2, group 3: GFR 30-60 mL/min/1.73 m2, group 4: GFR 15-29 mL/min/1.73 m2, group 5: GFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 [

9]. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tanta university, Egypt (reference number: 36264PR597/3/24, 09-03-2024).

3. Echocardiography

All patients were scheduled for Echo by using a Vivid E9 ultrasound system (GE Vingmed, Horton, Norway), all acquisitions were done with a broad-band M5S transducer (2.5-5 MHz) while the left lateral positioned patient utilizing apical four chambers, apical views and parasternal short axis and long axis views. Following the American Society of Echo (ASE) recommendations [

10]. The ECG was connected to establish the timing of cardiac cycle events. The ASE's recommendations were followed in the execution of two-dimensional Echo. The two-dimensional M-mode method was employed to measure EF, and the LA was assessed by examining its dimensions and volumes [

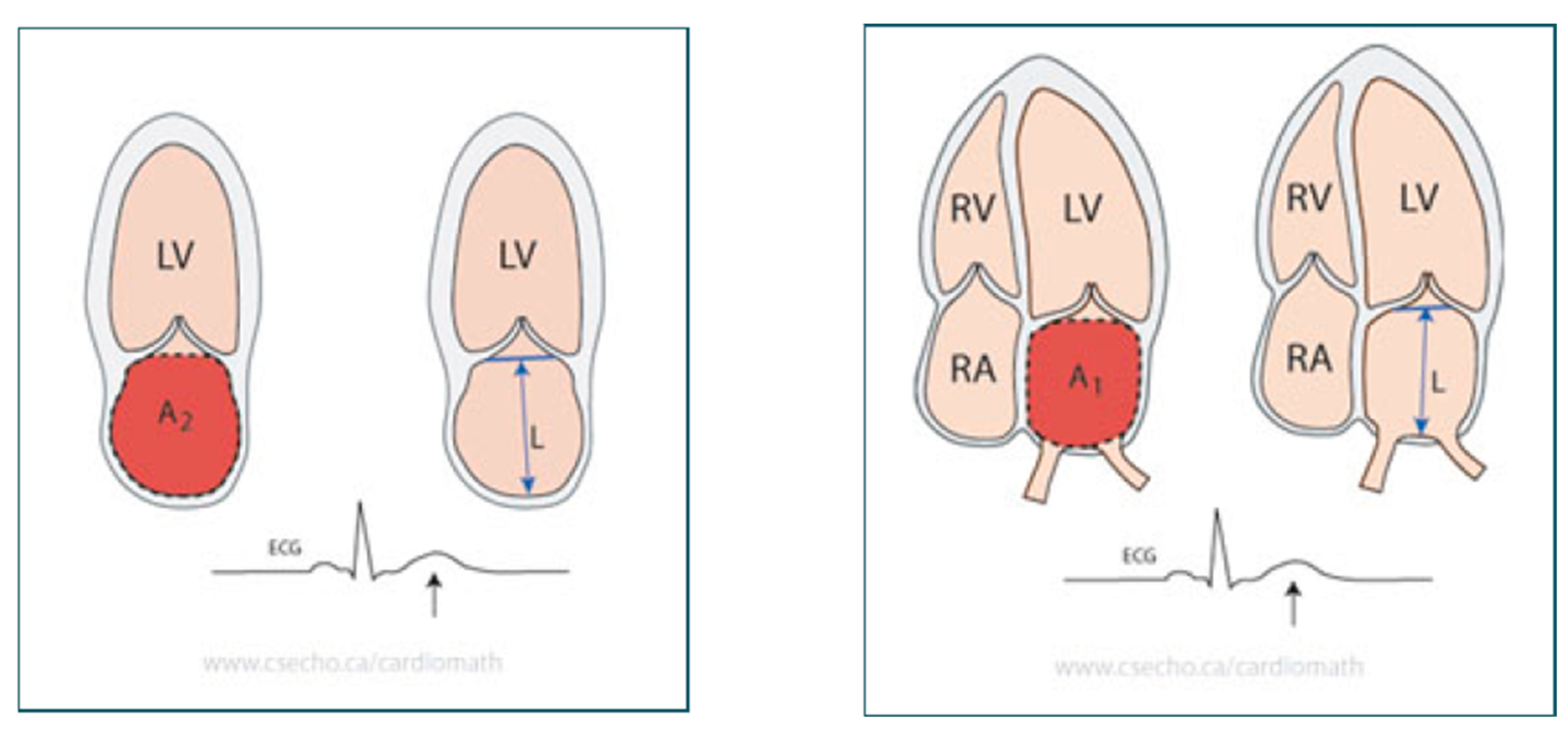

10]. Anteroposterior diameter measurement in parasternal long axis view utilizing the M-mode. LA volumes calculation was done using the Biplane Area-Length Method. The maximal LA size was determined at the end of the T wave on the ECG or at the end-ventricular systole end, immediately preceding the mitral valve opening. The pulmonary veins and the LA appendage confluences were eliminated during the planimetry procedure. The length, L, is the LA long-axis length, which is detected by the perpendicular line distance from the mitral annulus middle plane to the LA superior aspect. The length is assessed in both the 4- and 2-chamber views in the area-length formula, and the formula utilizes the shortest of these two length measurements, as illustrated in

Figure 1 [

11].

Pulsed-wave Doppler was utilized for diastolic function assessment by recording the trans mitral blood flow at the apical four-chamber view. We measured the E wave rate, the late diastolic blood flow rate (mitral late filling peak velocity, A), the E/A ratio, and the E wave deceleration time (DT). Tissue Doppler was employed to assessed the maximal early flow (e′) in the lateral and septum annulus, and the E/e′ ratio was estimated.

4. LA Longitudinal Strain Analysis

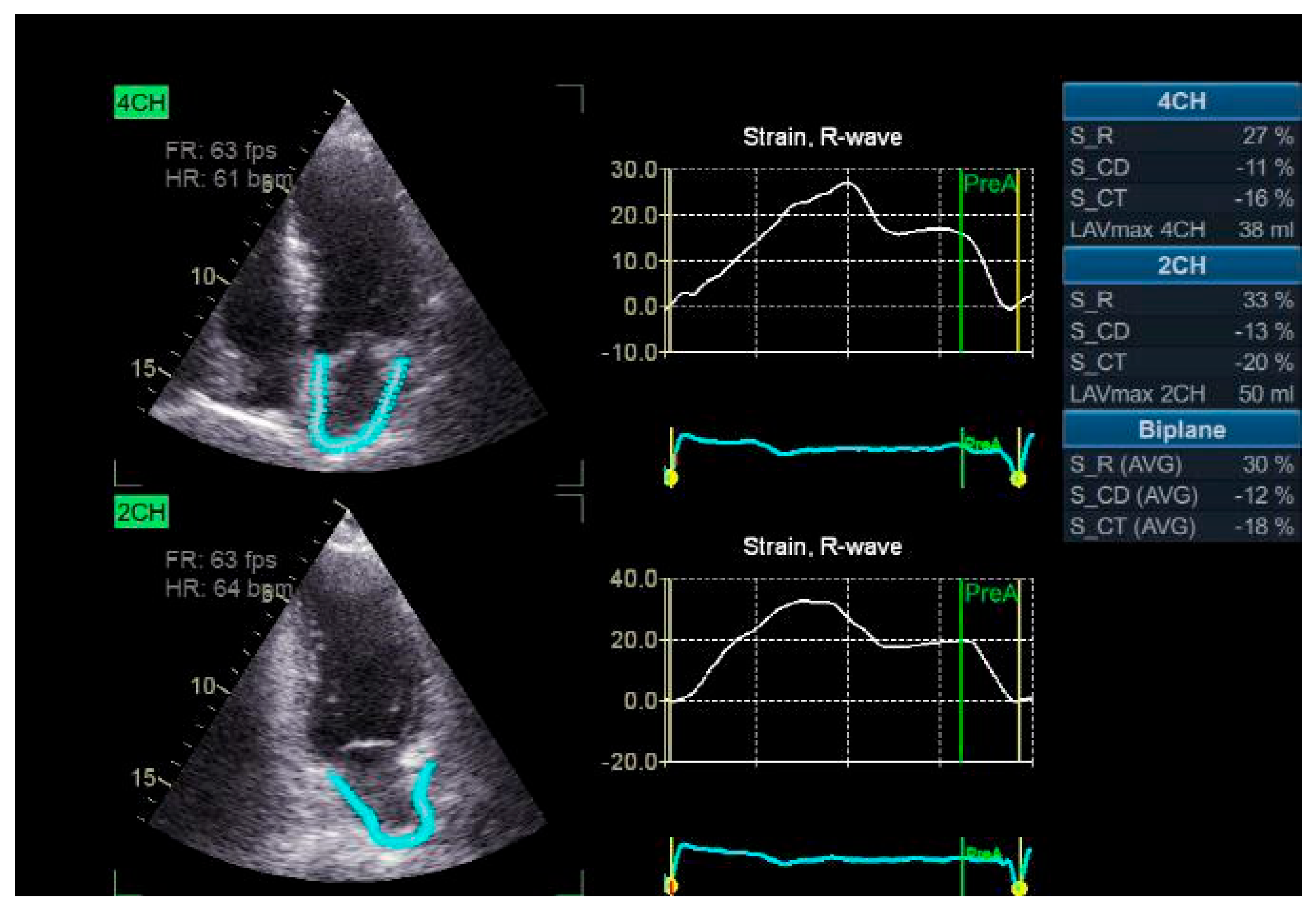

The strain rate and LA strain were measured utilizing the two-dimension strain analysis tool that is available on the Echo PAC workstation (GE Healthcare). The endocardial border defines the LA complete myocardial region of interest (ROI), like the left ventricle. An ROI that is adjustable and has a default width of 3 mm is advised. The operator could modify the size and configuration of the object to accommodate the LA wall thickness and to exclude the pericardium. The software automatically declined and excluded segments that were inadequately displayed from the analysis after dividing the atrial endocardium into six segments. The software generated the global longitudinal strain and strain rate profiles for each apical view. To achieve satisfactory tracking, the operator may either retry the imaging process or modify software parameters, including the smoothing functions and the ROI width. The electrocardiograph was recorded during the three consecutive heart pulses, and apical four and two-chamber views were obtained. The LA strain is identified as the absolute strain value in the three LA phases, which include conduit strain in early diastole (LASct), reservoir strain in systole (LASr), and contraction strain in late diastole (LAScd). LV end-diastole was the initial "0" reference point. The strains are as follows: LASr, which is estimated as the difference between the end-diastole and filling onset; LAScd, which is evaluated as the difference between the atrial contraction onset (prior to the Doppler A-wave onset) and the filling onset; and LASct, which is assessed as the difference between the atrial diastole end and filling onset the. The global strain was determined by averaging the respective values from both perspectives (

Figure 2) [

12].

5. Statistical Analysis

SPSS v27 (IBM©, Armonk, NY, USA) was utilized for the statistical analysis. The data distribution normality was indicated using the histograms and Shapiro-Wilks test. The quantitative parametric data were provided as mean and standard deviation (SD), and they were contrasted utilizing an unpaired student t-test between the two groups and a one-way ANOVA with post Hoc between the five groups. When appropriate, the Fisher's exact or the Chi-square test were utilized to analyze the frequency and (%) of the qualitative variables. Statistical significance was identified as a two-tailed P value < 0.05. We utilized receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to find the area under the curve (AUC) for the diagnostic value of E/A, LAVI, LA reservoir strain, and LA strain conduit can significantly diagnose LV Diastolic Function in CKD Patients.

6. Results

The study participants was categorized into 5 groups on the basis of GFR i.e. GR1=20(%), Gr2=24(%), Gr3=72(%), Gr4=64(%) and Gr5=40(%). The mean age of study contributors was 62.26±9.8 years. Out of 220, 112(51%) were male and 108(49%) were female patients. Distribution of study participants according to the GFR groups

Table 1. The patients’ max mean age was observed in Gr5 group i.e. 75.6±8.7 years and minimum were observed in Gr2 group i.e. 51.4±14.8. 70.8% and 75% male patients belonged to Gr2 and Gr1 group respectively. While 62.5% female patients were in Gr4 group. Hypertension was indicated in 67.5% of cases in the Gr5 group. 85% of patients of Gr1 had diabetes, 50% patients of Gr1 and Gr2 group each had smoking history, however 50% patients of Gr5 reported dyslipidemia. Diastolic dysfunction grade 2 and 3 was seen among Gr4 (59.4 & 20.3%) and Gr5 group (37.5% & 57.5%). None of the patients of Gr1 and Gr2 reported diastolic dysfunction of grade 2 & 3. Mean and standard deviation of studied markers i.e. E/A, average E/e', TR velocity and LAVI are depicted in

Figure 2. Maximum mean value among all markers was observed in Gr5 group. LA reservoir strain was significantly different among studied groups (P <0.001), it was significantly elevated in Gr1 than Gr3,4 and 5 (P value <0.05) and insignificantly different with Gr2 and it was significantly higher in Gr2 than Gr3,5 (P <0.05) and insignificantly different with Gr1,4 and was significantly lower in Gr3 than Gr 1,2,4 (P <0.05) and was significantly less in Gr4 than Gr1 and significantly greater in Gr4 than Gr3 (P <0.05) and was significantly lower in Gr5 than Gr1 and 2(P <0.05). LA strain conduit was significantly different among studied groups (P <0.001), it was significantly lower in Gr1 than Gr2,3,4 and 5 (P <0.05) and Gr2 was significantly lower than Gr3,4 and 5 (P <0.05), and was significantly less in Gr3 than Gr 4 and 5 (P value <0.05) and was significantly reduced in Gr4 than Gr5 (P <0.05). LA strain contraction was insignificantly different among the studied groups.

Table 1

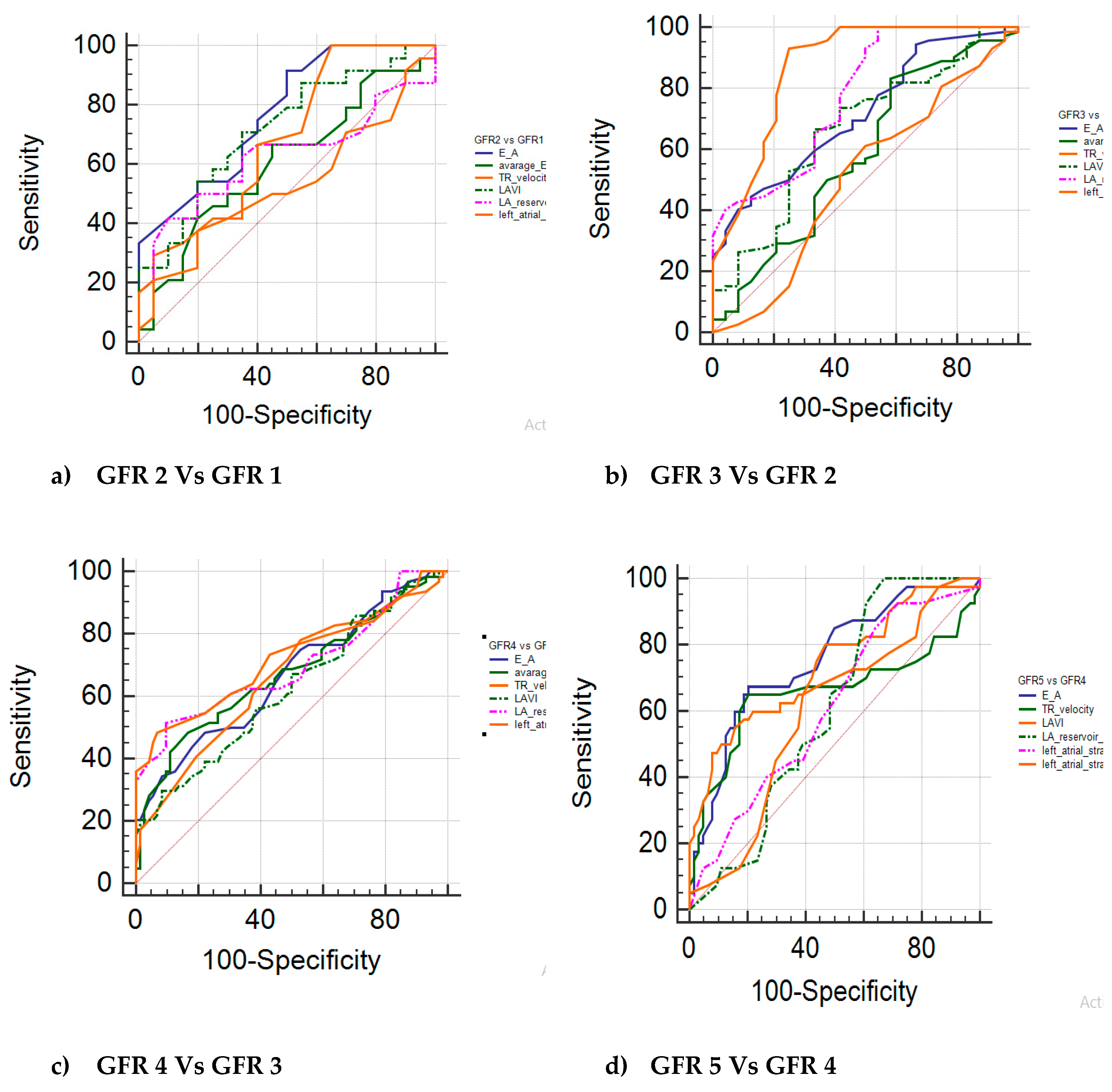

The studied markers diagnostic performance among GFR groups is mentioned in

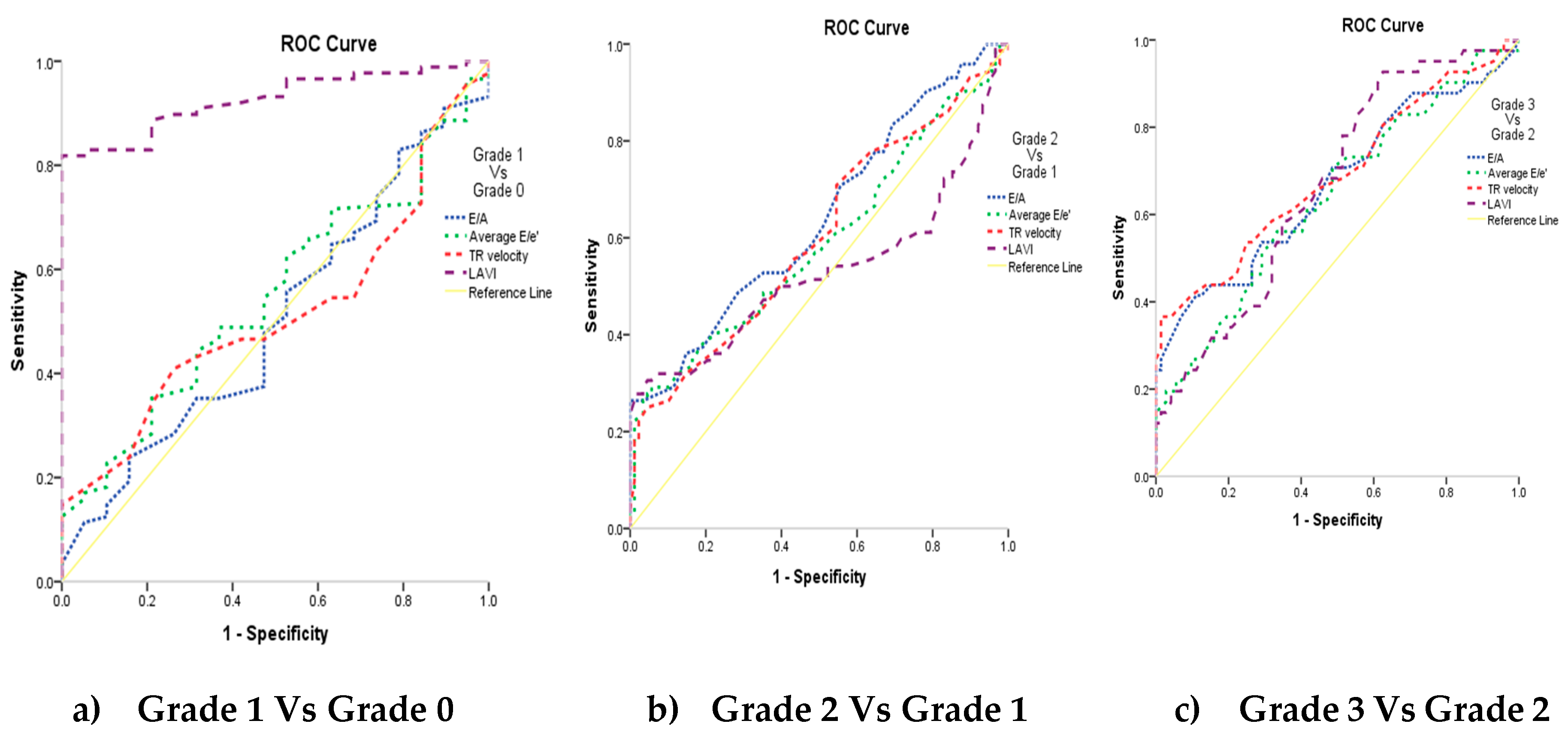

Table 2. The GFR groups were sub-grouped and compared with studied markers, sensitivity and specificity and AUC was indicated. The findings of the study showed statistically significant findings with E/A and LAVI, LAScd among all sub-groups (p≤0.01). In GFR 3 Vs GFR 2, showed statistically significant findings with LASr (p≤0.01). Subgroup GFR 4 vs GFR 3 and GFR 4 vs GFR 5 showed >90% specificity with LAVI, LASr and LAScd and statistically significant findings of both sub-groups was observed with all of the markers (p≤0.01). AUC more than 0.7 was seen among E/A and LAVI of GFR 2 vs GFR 1, E/A, LASr and LAScd of GFR 3 vs GFR 2, LAScd of GFR 4 vs GFR 3, E/A and LAVI of GFR 5 vs GFR 4. Receiver operating (ROC) curves of GFR subgroups with studied markers are shown in

Figure 3. The AUC of remaining sub-groups with markers was <0.7.

Table 2,

Figure 3.

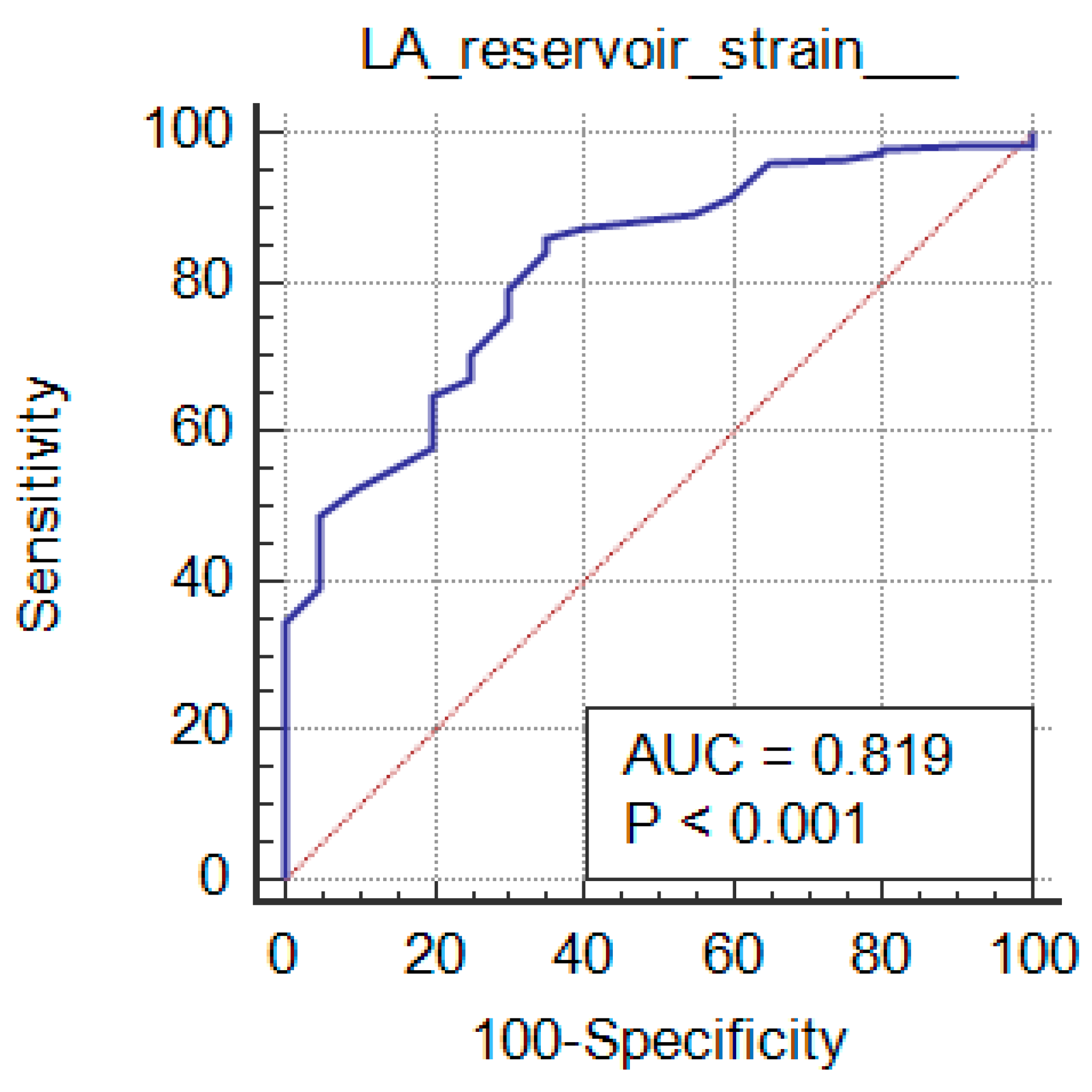

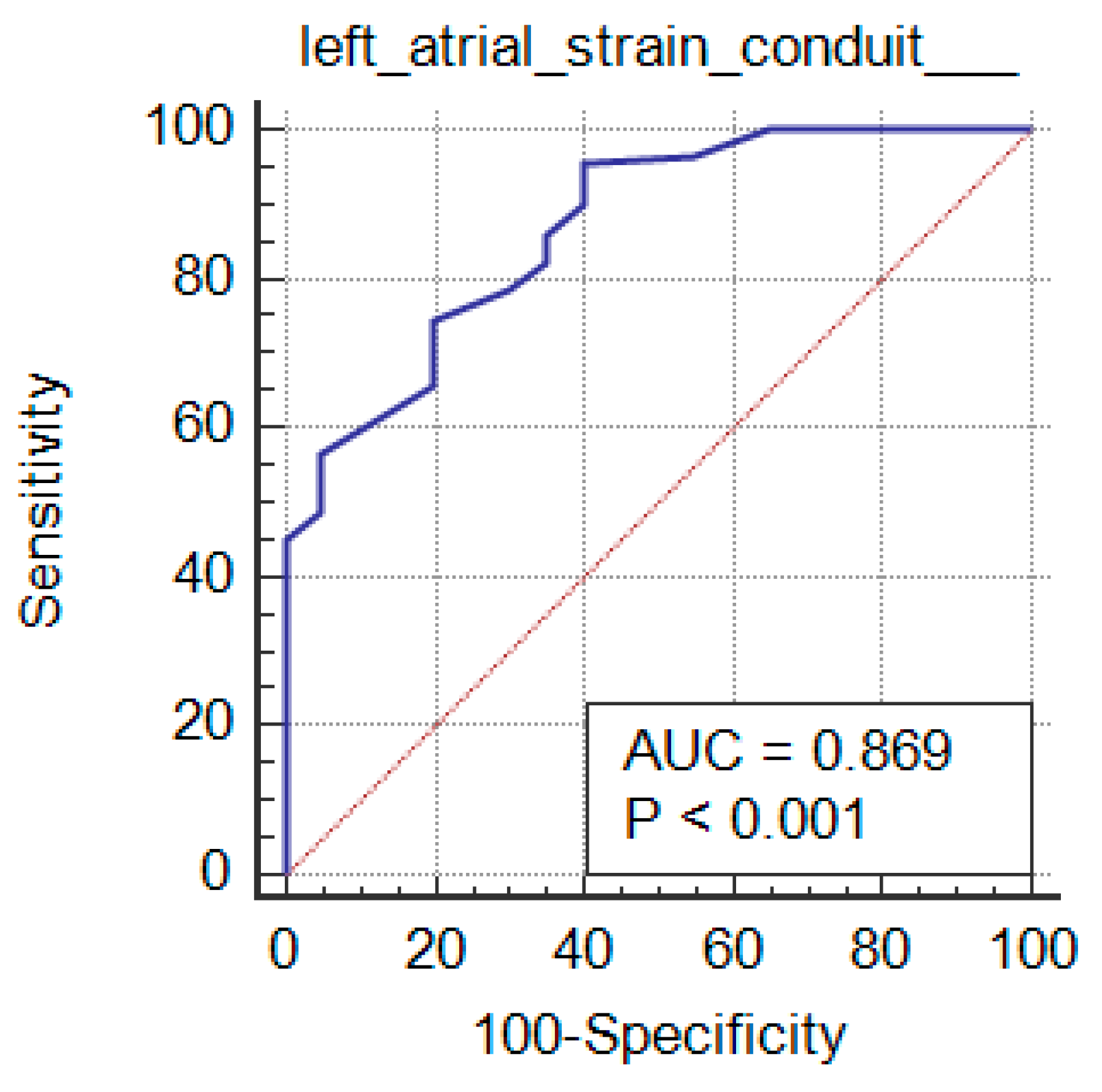

The studied markers diagnostic performance among the grades of the diastolic function is mentioned in Table 4. Comparison of grades with studied markers, their sensitivity and specificity and AUC determined that statistically significant findings were noticed with grade 3 vs grade 2 (p≤0.01). All the markers except LAVI showed significance with grade 2 vs grade 1 (p<0.05). grade 1 vs grade 0 showed statistically significance with LAVI (p<0.0001) only. LA reservoir strain and LA strain conduit can significantly diagnose LV Diastolic Function in CKD patients (P <0.001 and AUC=0.819 and 0.869 respectively) at cutoff ≤36 and >-23, with 86% and 95.5% sensitivity, 65% and 60% specificity, 96.1% and 96% PPV and 31.7% and 57.1% NPV respectively. LA strain contraction cannot diagnose LV Diastolic Function in patients with CKD.

Table 3

ROC curves of studied markers among grades of diastolic function are depicted in

Figure 4. AUC=0.926 was observed with LAVI among grade 1 vs grade 0 (0.9 is considered excellent in diagnosing patients with and without the disease) as shown in

Figure 6 (a), LAVI curve (purple dotted line) is above the diagonal line. While other markers among the grades of the diastolic function had AUC of 0.5-0.6, which suggests no discrimination in diagnosing the disease.

Figure 4.

7. Discussion

LA strain presents significant reproducibility and feasibility, which has lately emerged as a powerful measurement in LVDD evaluation [

13]. We aimed to address the role of LA strain value versus tissue Doppler Echo and the LA volume index in the LV diastolic function evaluation in CKD patients.

In this study of LA strain more sensitive and accurate than LAVI Specially in early kidney disease stages as early diagnosis of the disease gives better prognosis, also, we reported that conduit strain and LA reservoir strain had stronger associations with early stages of kidney disease than LA volume index. LA reservoir and LA strain conduit can significantly diagnose LV Diastolic Function in CKD cases (P <0.001 and AUC=0.819 and 0.869 respectively) at cutoff ≤36 and >-23, with 86% and 95.5% sensitivity, 65% and 60% specificity, 96.1% and 96% PPV and 31.7% and 57.1% NPV respectively. Conduit strain and LA reservoir have been detected in few ESRD studies with adjudicated outcomes.

In unadjusted analyses, Tsai et al. found that LA strain was associated with both overall and CV mortality [

14]. In 79 patients with ESRD, Papadopoulos et al. indicated that the LA reservoir strain predicted paroxysmal AF [

15]. Gan et al., in a recent study of pre-dialysis CKD Stages ¾ cases, detected that LA reservoir strain was a highly accurate predictor (AUC 0.84) of CKD Stages and overall mortality. The association between LA reservoir strain and the composite outcome was significant after adjusting for comorbidities and echocardiographic parameters [

16]. The average LA reservoir strain (24 ± 7%) was significantly worse than the normal LA reservoir strain (>39%) illustrated in a meta-analysis of healthy populations, as per Pathan et al. [

17], but comparable to HFpEF cases in the Treatment of Preserved Cardiac Function HF With an Aldosterone Antagonist (TOPCAT) [

18], and similar to CKD patients [

19].

In patients with LVEF ≥ 50%, Fan et al. [

12] found that LA strain was substantially impaired in the group with increased LVEDP. The LA reservoir strain predicted LVEDP > 16 mmHg with 82.9% specificity and 90% sensitivity at a cut-off of 26.7%, achieving a higher diagnosis accuracy than LAScd, E/e′, and LASct.

During the initial LVDD phase, the passive early transmitral diastolic flow is reduced as a result of diminished ventricular compliance and elevated LVEDP. Subsequently, the atrial pump function is improved to balance for the LV filling. The compliance of the LA could be compromised as a result of the elevated atrial pressure, which is necessary to maintain cardiac output as LV distensibility continues to decrease. As a result of persistently increased LVEDP and lowered LA compliance, LA function is impaired [

20]. This could be the potential mechanism responsible for the negative correlation between LA strain and LVEDP.

The LV pathological alterations could result in LA function impairment due to the intimate connection between the two chambers. In CKD patients, the LA is a chamber that is more susceptible to fluid accumulation and elevated LV filling pressure [

4].

The most prevalent cardiac abnormalities in CKD cases are LV hypertrophy, dilatation, and dysfunction. In previous research, it was discovered that LV hypertrophy was the initial significant cardiac impairment as a result of a consistently elevated plasma urea level, which becomes increasingly severe as CDK stages progress [

21]

, earlier than dysfunction and dilatation [

5]

. As the CKD severity increased, so did GLS in our study. This phenomenon could be attributed to the fact that the LV strain was susceptible to the preload and fluid excess condition, as well as uremic cardiomyopathy [

22].

LA volume index (LAVi) is a significant HF predictor and cardiovascular outcomes, and LA strain also serves a novel role in CKD [

23]. Through the cardiac cycle, the LA functions as a reservoir, accumulating blood from the pulmonary veins. Upon the diastolic phase commencing, the mitral valve functions as a conduit for the blood transfer from LA to LV. The contractile force of the LA will propel the remaining blood to the LV. [

24].

In our Nguyen et al. [

19] This trend was not observed by the LASct, despite the fact that the LASr and LAScd function rejected in tandem with kidney function, as demonstrated by the speckle tracking Echo data. Furthermore, this investigation determined that the LA reservoir conduit functions were a critical indicator that was associated with the CKD severity among the LA speckle tracking parameters. Consequently, it is possible that these echocardiographic speckle-tracking parameters are more susceptible to fluid excess during the initial CKD phases. This discovery was consistent with a earlier report that demonstrated that impaired LA and LV strain in CKD patients had no relationship with deteriorating renal function, and that eGFR was associated with GLS, LAScd, and LASr [

25].

Despite the absence of any differences in conventional Doppler parameters (E/A, E/e'), the diastolic myocardial mechanics of the ESRD group were significantly altered in a study that involved 53 ESRD cases and 85 controls. The earSR E/S ratio, apically atrial strain, reverse rotation, and strain rate fraction were significantly reduced in the ESRD group [

26]. Additionally, the type of dialysis affects the LA strain parameters. According to a single, limited study done by Aksu et al. [

27] In contrast to hemodialysis patients, patients who underwent peritoneal dialysis exhibited significantly greater peak systolic strain and LA strain with contraction values.

LA strain is altered prior to the onset of volume alterations and can predict both systolic and diastolic dysfunction. In a study that assessed the relationship between DD, LA function, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels both after and before maintenance hemodialysis (HD) sessions, 30 patients with preserved ejection fraction and on HD were included. BNP values were negatively correlated with LA volumes, and strain, and E/e' prior to HD.

It has been a topic of debate as to which echocardiographic LA abnormalities are more specific in this specific setting, as CKD patients typically have at least one comorbidity. Kadappu et al. sought to indicate the LA size and function by contrasting CKD cases with hypertensive normal kidney function patients. The objective was to ascertain the potential additive CKD influence on LA echocardiographic parameters. Although there were no distinctions between hypertensive and CKD patients in LAVi terms, CKD cases exhibited a significant reduction in color tissue Doppler systolic strain, and conduit, LA reservoir, and contractile functions. Consequently, LA strain is more effective than traditional two-dimensional echocardiographic measurements in distinguishing the CKD consequences from other potential associated comorbidities [

28].

Additionally, the LA reservoir, LA strain, and contractile function evaluation is highly beneficial in the identification of myocardial involvement in CKD, as these parameters decrease significantly in CKD cases contrasted to controls. These reductions occur earlier in time than those of LV parameters [

29].

LA strain appears to possess prognostic value in renal cases, as it does in the general population. LA reservoir strain could independently predict cardiovascular mortality and MACCE in 243 CKD stage 3–4 cases. It was significantly more accurate than LV mass, strain, and volume and established clinical risk scores (Framingham, Atherosclerotic CVD) [

30].

8. Limitations and Recommendations

Our study is limited by several factors, including its single-center nature. To ensure the validity of our findings, it is necessary to confirm their generalizability through large-scale prospective multicenter studies.

Further investigations, including a greater patient population, encompassing individuals with CKD Stages and accounting for additional clinical and echocardiographic factors, are necessary to validate our findings.

We suggest conducting more trials on bigger cohorts of patients with CKD using novel imaging modalities and incorporating other criteria to enhance the precision of LVDD assessment.

9. Conclusions

LA conduit strain and reservoir strain are independent markers that are highly valuable in evaluating diastolic function in patients with CKD. It is a superior and more sensitive approach than LAVI and E/e′ for evaluating LVDD even in the early CKD stages.

Author Contributions

E.E: conception and design, analysis, or interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript, approval of the final version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. ZA: interpretation of data, revising the manuscript, approval of the final version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. S.I.A: interpretation of data, revising the manuscript, approval of the final version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. M.S: interpretation of data, revising the manuscript, approval of the final version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. I.K. conception and design, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting and revising the manuscript, approval of the final version, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Tanta university, Egypt (reference number: 36264PR597/3/24, 09-03-2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Correspondence and requests for data supporting the study results can be addressed to the primary author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Kovesdy, C.P. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney international supplements. 2022, 12, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consortium, C.K.D.P. Association of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in general population cohorts: a collaborative meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2010, 375, 2073–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, S.; James, M.; Wiebe, N.; Hemmelgarn, B.; Manns, B.; Klarenbach, S.; et al. Cause of death in patients with reduced kidney function. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2015, 26, 2504–2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagueh, S.F. Left ventricular diastolic function: understanding pathophysiology, diagnosis, and prognosis with echocardiography. JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2020, 13, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dogan, U.; Ozdemir, K.; Akilli, H.; Aribas, A.; Turk, S. Evaluation of echocardiographic indices for the prediction of major adverse events during long-term follow-up in chronic hemodialysis patients with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. European Review for Medical & Pharmacological Sciences. 2012, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Frydas, A.; Morris, D.A.; Belyavskiy, E.; Radhakrishnan, A.K.; Kropf, M.; Tadic, M.; et al. Left atrial strain as sensitive marker of left ventricular diastolic dysfunction in heart failure. ESC heart failure. 2020, 7, 1956–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modin, D.; Biering-Sørensen, S.R.; Møgelvang, R.; Alhakak, A.S.; Jensen, J.S.; Biering-Sørensen, T. Prognostic value of left atrial strain in predicting cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the general population. European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging. 2019, 20, 804–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freed, B.H.; Daruwalla, V.; Cheng, J.Y.; Aguilar, F.G.; Beussink, L.; Choi, A.; et al. Prognostic utility and clinical significance of cardiac mechanics in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: importance of left atrial strain. Circulation: Cardiovascular Imaging. 2016, 9, e003754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliadis, F.; Didangelos, T.; Ntemka, A.; Makedou, A.; Moralidis, E.; Gotzamani-Psarakou, A.; et al. Glomerular filtration rate estimation in patients with type 2 diabetes: creatinine-or cystatin C-based equations? Diabetologia. 2011, 54, 2987–2994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Members, C.; Cheitlin, M.D.; Armstrong, W.F.; Aurigemma, G.P.; Beller, G.A.; Bierman, F.Z.; et al. ACC/AHA/ASE 2003 guideline update for the clinical application of echocardiography: summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ASE Committee to Update the 1997 Guidelines for the Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Circulation. 2003, 108, 1146–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Cimadevilla, C.; Nadia, B.; Dreyfus, J.; Perez, F.; Cueff, C.; Malanca, M.; et al. Echocardiographic measurement of left atrial volume: Does the method matter? Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases. 2015, 108, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, J.-L.; Su, B.; Zhao, X.; Zhou, B.-Y.; Ma, C.-S.; Wang, H.-P.; et al. Correlation of left atrial strain with left ventricular end-diastolic pressure in patients with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. The international journal of cardiovascular imaging. 2020, 36, 1659–1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cameli, M.; Mandoli, G.E.; Loiacono, F.; Dini, F.L.; Henein, M.; Mondillo, S. Left atrial strain: a new parameter for assessment of left ventricular filling pressure. Heart failure reviews. 2016, 21, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, W.-C.; Lee, W.-H.; Wu, P.-Y.; Huang, J.-C.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, S.-C.; et al. Ratio of transmitral E wave velocity to left atrial strain as a useful predictor of total and cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019, 9, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, C.E.; Pagourelias, E.; Bakogiannis, C.; Triantafyllou, K.; Baltoumas, K.; Kassimatis, E.; et al. Left atrial deformation as a potent predictor for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation in patients with end-stage renal disease. The International Journal of Cardiovascular Imaging. 2018, 34, 1393–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, G.C.; Kadappu, K.K.; Bhat, A.; Fernandez, F.; Gu, K.H.; Cai, L.; et al. Left atrial strain is the best predictor of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2021, 34, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathan, F.; D'Elia, N.; Nolan, M.T.; Marwick, T.H.; Negishi, K. Normal ranges of left atrial strain by speckle-tracking echocardiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2017, 30, 59–70.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.B.; Roca, G.Q.; Claggett, B.; Sweitzer, N.K.; Shah, S.J.; Anand, I.S.; et al. Prognostic relevance of left atrial dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation: Heart Failure. 2016, 9, e002763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Do, C.V.; Dang, D.T.V.; Do, L.D.; Doan, L.H.; Dang, H.T.V. Progressive alterations of left atrial and ventricular volume and strain across chronic kidney disease stages: a speckle tracking echocardiography study. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2023, 10, 1197427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensen, L.C.; Goossens, K.; Delgado, V.; Abou, R.; Rotmans, J.I.; Jukema, J.W.; et al. Prevalence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction in pre-dialysis and dialysis patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction. European journal of heart failure. 2018, 20, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park M, Hsu C-y, Li Y, Mishra RK, Keane M, Rosas SE, et al. Associations between kidney function and subclinical cardiac abnormalities in CKD.

Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2012, 23, 1725–1734.

- Wang, X.; Hong, J.; Zhang, T.; Xu, D. Changes in left ventricular and atrial mechanics and function after dialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery. 2021, 11, 1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanasa, A.; Tapoi, L.; Ureche, C.; Sascau, R.; Statescu, C.; Covic, A. Left atrial strain: A novel “biomarker” for chronic kidney disease patients? Echocardiography. 2021, 38, 2077–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blume, G.G.; Mcleod, C.J.; Barnes, M.E.; Seward, J.B.; Pellikka, P.A.; Bastiansen, P.M.; et al. Left atrial function: physiology, assessment, and clinical implications. European Journal of Echocardiography. 2011, 12, 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwama, K.; Nakanishi, K.; Daimon, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Sawada, N.; Hirose, K.; et al. Chronic kidney disease and subclinical abnormalities of left heart mechanics in the community. European Heart Journal Open. 2021, 1, oeab037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calleja, A.M.; Rakowski, H.; Williams, L.K.; Jamorski, M.; Chan, C.T.; Carasso, S. Left atrial and ventricular systolic and diastolic myocardial mechanics in patients with end-stage renal disease. Echocardiography. 2016, 33, 1495–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, U.; Aksu, D.; Gulcu, O.; Kalkan, K.; Topcu, S.; Aksakal, E.; et al. The effect of dialysis type on left atrial functions in patients with end-stage renal failure: A propensity score-matched analysis. Echocardiography. 2018, 35, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Fan, R.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; et al. Left atrial strain associated with alterations in cardiac diastolic function in patients with end-stage renal disease. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019, 35, 1803–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadappu, K.K.; Abhayaratna, K.; Boyd, A.; French, J.K.; Xuan, W.; Abhayaratna, W.; et al. Independent Echocardiographic Markers of Cardiovascular Involvement in Chronic Kidney Disease: The Value of Left Atrial Function and Volume. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, G.C.H.; Kadappu, K.K.; Bhat, A.; Fernandez, F.; Gu, K.H.; Cai, L.; et al. Left Atrial Strain Is the Best Predictor of Adverse Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2021, 34, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).