1. Introduction

Biosensors are electrochemical devices that translate biochemical reactions into electrical signals, enabling real-time monitoring of biological processes. They are used in applications such as: glucose monitoring in diabetic patients, checking enzyme levels in cancer patients, drug efficacy trials, tracking fermentation processes, detecting artificial sweeteners in food and drink, and monitoring cell viability in cell culture experimentation [

1]. Due to printed biosensors relying on surface interactions, they are highly sensitive to contamination or fouling during operation and are therefore commonly disposed of after one use, resulting in the release of harmful and hazardous materials into the environment.

Electrochemical sensors commonly comprise three electrodes: i) working electrode (WE) where the electrochemical reaction of interest occurs, ii) reference electrode (RE) which provides a stable and known potential to act as a reference (if required), and iii) counter electrode (CE) to complete the circuit [

2]. Silver or silver chloride are commonly used as the RE due to electrochemical stability and long term stability [

3]. Gold or carbon are often used for the WE and CE where gold provides a chemically inert surface with efficient electron transfer, and carbon offers a low-cost option with a wide potential window [

4,

5].

Silver and gold mining practices are highly environmentally damaging due to the leaching of toxic chemicals (i.e., cyanide and mercury), loss of biodiversity, and greenhouse gas emissions [

6]. Furthermore, the release of these resources to the environment via electronic waste results in the loss of valuable and finite resources, with silver release specifically reducing microbial soil populations, inhibiting enzyme activity, and disrupting plant growth [

7]. Carbon is often suggested as a promising alternative to noble metals, owing to its comparatively lower carbon footprint [

8]; however it is often an unfeasible replacement due to carbon’s lower conductivity which reduces device sensitivity [

9]. In addition to environmental concerns, silver and gold are greatly affected by both global instability [

10] and the increasing demand for electronic and energy harvesting devices [

11]. This is reflected in the price of silver and gold, which has increased by 49.8% and 46.2% respectively over the last year alone [

12,

13]. This further highlights the need and potential economic benefits for increased recovery and recycling of silver and gold.

There is growing research exploring methods for the extraction of silver and gold from mixed electronic waste via pyrometallurgical, hydrometallurgical, and bio-metallurgical methods, which can be used to separate high purity metal salts from chemically complex mixtures [

14]. While these processes offer effective routes to separation and recovery of high value materials, they are often convoluted, requiring the use of hazardous chemicals and high operating temperatures; ultimately facing significant economic limitations [

15]. This challenge is further exacerbated by the low recycling rate of electronic devices, which reached an average of 37.5% in 2023 across the EU; significantly lower than the 65% target [

16]. This may offer a partial explanation for the continued shortfall in recycling outputs relative to the growing demand for silver and gold [

17].

Circularity is an increasingly important consideration in the development of printed electronic (PE) devices. Concerns over resource use and e-waste, alongside EU Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation [

18], have made ecodesign and circularity central to electronics innovation. Integrating ecodesign principles from the earliest stages of development facilitates the creation of electronic products that are more durable, recyclable, and resource efficient [

19]. Design for recycling is particularly relevant for PE devices; innovations that enable easy disassembly and material separation at end-of-life can facilitate the recovery of valuable components such as gold and silver, while reducing the need for complex separation and recovery processes [

20].

Several papers report the development of lower environmental impact biosensors by using recycled fossil-based polymers (e.g., polyester terephthalate (PET) and polyimides) and carbon-based reinforcements (e.g., graphene) [

21,

22]. However, to address the environmental limitations of those substrates, attention has shifted toward bio-based and recyclable alternatives, like polylactic acid (PLA) offering significantly reduced greenhouse gas emissions when compared with PET [

23,

24]. Alternative solutions to PET or PLA substrates could be fully biodegradable materials such as paper-based substrates [

25], cellulose [

26] or gelatin-based materials [

27]. However, each of these offers an imperfect solution, whether it be the poor thermal and mechanical stability of gelatin or the porosity of paper-based substrates; properties that limit print definition and curing temperature (i.e., 80–120

oC). While these innovations provide exciting developments, they do not address the impacts of these devices at end-of-life, nor do they employ circular design principles. Recent advances from companies such as Ail Arian provide commercially viable solutions for silver ink recovery and reuse, but gaps remain for the remainder of the device components [

28].

Additive manufacturing is often discussed as a more sustainable route to manufacturing, due to the nature of depositing only the material that is required, and through producing mesh patterns to achieve sufficient percolation with less material [

29]. This approach provides an exciting route to minimising material usage but can often be overlooked by industry due to slower production times and lack of compatibility with pre-existing manufacturing lines; sustainable solutions must be attractive to industry to enable true adoption.

Any effort towards enhancing sustainability in electronics should be evaluated through Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Current literature indicates that PE technologies, such as roll-to-roll processing, inkjet or screen printing, and the use of biodegradable substrates, offer potential sustainability advantages compared to conventional silicon-based electronics [

28,

29]. However, several studies highlight that the production phase, particularly material preparation and large-scale printing processes, remains a major contributor to the overall environmental impact [

32]. Despite this progress, the state of the art still highlights that significant data and methodological gaps exist. For instance, reliable life-cycle inventories for printed conductive inks and polymeric substrates are limited, the diversity of materials and device architectures complicates cross-comparison, and end-of-life management strategies for printed components are not yet well established. Overall, LCA applications in printed electronics are in a consolidation phase, providing valuable insights into environmental hotspots but still requiring further research on primary data collection, circularity scenarios, and eco-design integration to support sustainable technology development.

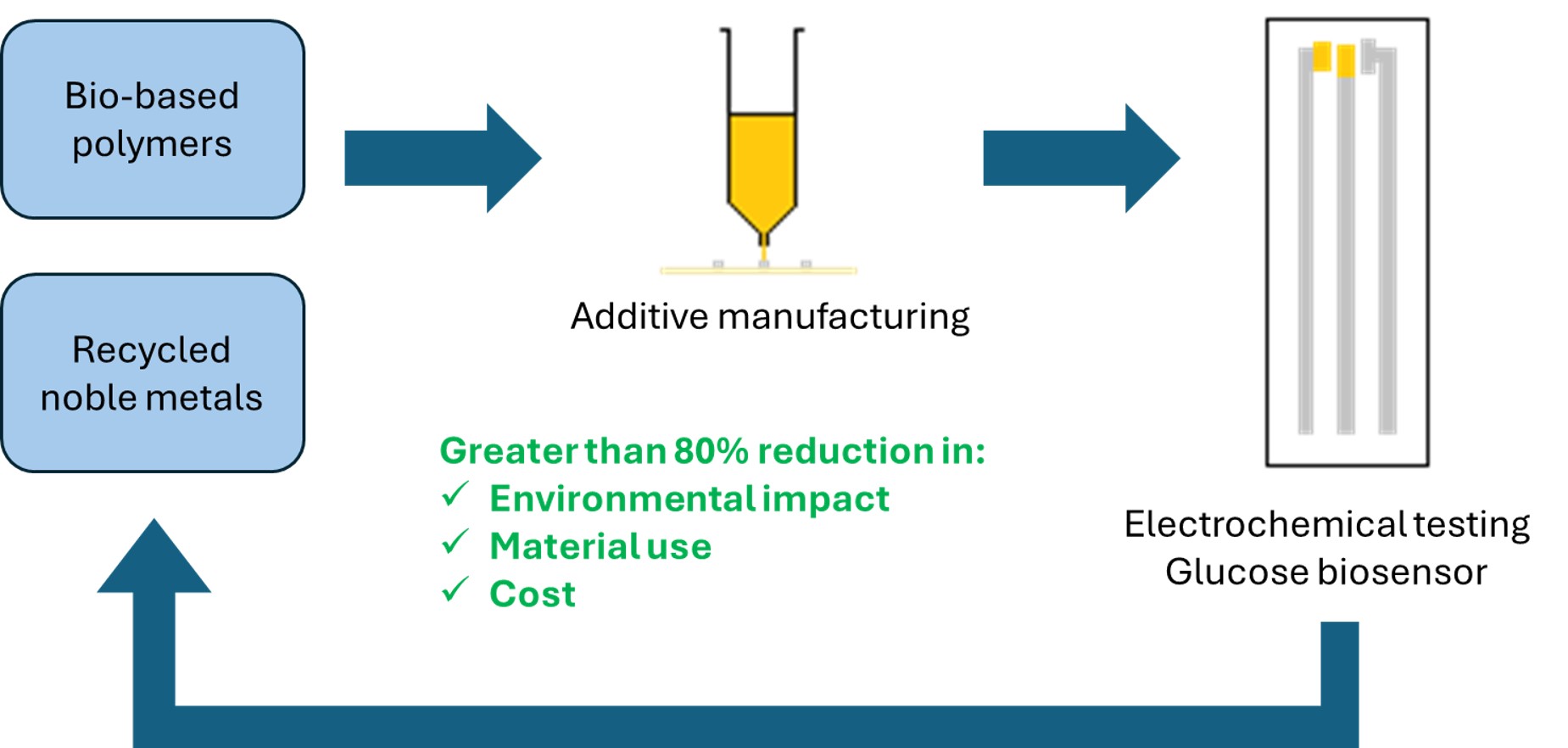

To achieve high-performance, cost-effective glucose biosensors with significantly reduced environmental impact, we propose a novel sensor architecture integrating material and process innovations. Devices combined closed-loop recycling with the use of silver and gold to maintain high performance without contributing to the electronic waste burden. By incorporating sustainable-by-design principles, strategic use of additive manufacturing, and biopolymer substrates, the environmental impact of these high performing devices was significantly reduced.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Polymers and solvents were sourced from Sigma Aldrich: cellulose acetate (Mn 30 kDa and 39.8% acetylation, Mn 50 kDa and 39.7 wt% acetylation), polycaprolactone (Mn 10 kDa and Mn 80 kDa), cyrene (Biorenewable), benzyl acetate (bioderived, ≥99%), ethyl acetate (≥99.5%) and acetone (≥99.5%). Silver flakes (EA0295, D50 5.2 µm) and gold flakes (PUAU594, D50 4.1 µm) were sourced from Metalor Advanced Coatings. Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) PMX17c was sourced from HiFi Films. The PLA substrate was provided by the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki at 0.38 ± 0.02 mm thickness [

32,

33]. Nitric acid (67-70%) was purchased from Fisher for ICP-MS sample preparation. Potassium ferrocyanide (K

4 [Fe(CN)

6]), potassium ferricyanide (K

3 [Fe(CN)

6]), potassium chloride (KCl), d-(+)-glucose, Trizma

® base and nitric acid (65%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (USA). All reagents used in sensor functionalisation and electrochemical testing were analytical grade. All solutions used in the electrochemical testing were prepared daily using type 1 ultrapure water (Direct-QTM 5 system, Millipore).

2.2. Mixing

Polymers were dissolved in solvents prior to combining with metal powders using a hotplate stirrer at 60 ºC and 350 rpm for 2 hours. Polymer solutions and metal powders were combined and mixed using dual-axis centrifugal mixing (DAC) at 1500 rpm for 1 minute. Mixing was repeated for a further 1 minute after the material inside the mixing container was redistributed with a spatula. For inks containing gold, 5 mm stainless steel ball bearings were added for 3 additional mixing steps at 2000 rpm for 30 second bursts to prevent heat buildup.

2.3. Rheology

Rheology measurements were carried out using a TA Instruments Discovery HR2 fitted with a 40 mm parallel roughened steel plate. Samples were held at 25 ºC and analysed using a 500 µm gap following a 1-minute equilibration. Ink behaviour was characterised by measuring viscosity at 1.5 s−1, 15 s−1, and 1000 s−1. Each shear rate was held for 60 seconds prior to returning the sample to 1.5 s−1 and holding until at least 10 measured points fell within a 5% tolerance. The purpose of this experiment was to simulate ink behaviour following being subjected to shearing stresses by the print process and recovering viscosity once shearing forces have been removed. To determine the time taken for solutions to solidify and heat required to enable sufficient flowability; samples were subjected to 1 Hz and 1% strain for 180 minutes at 20 ºC, following immediate heating to 40 ºC for 120 minutes.

2.4. Scanning Electron Microscopy

A Hitachi SU8230 field-emission electron microscope was used in secondary electron mode with an acceleration voltage of 3 kV, 10 µA emission current and a working distance of 11.6 mm. Ink was mounted onto a silicon chip and allowed to dry in air. No conductive coatings were applied before imaging the sample.

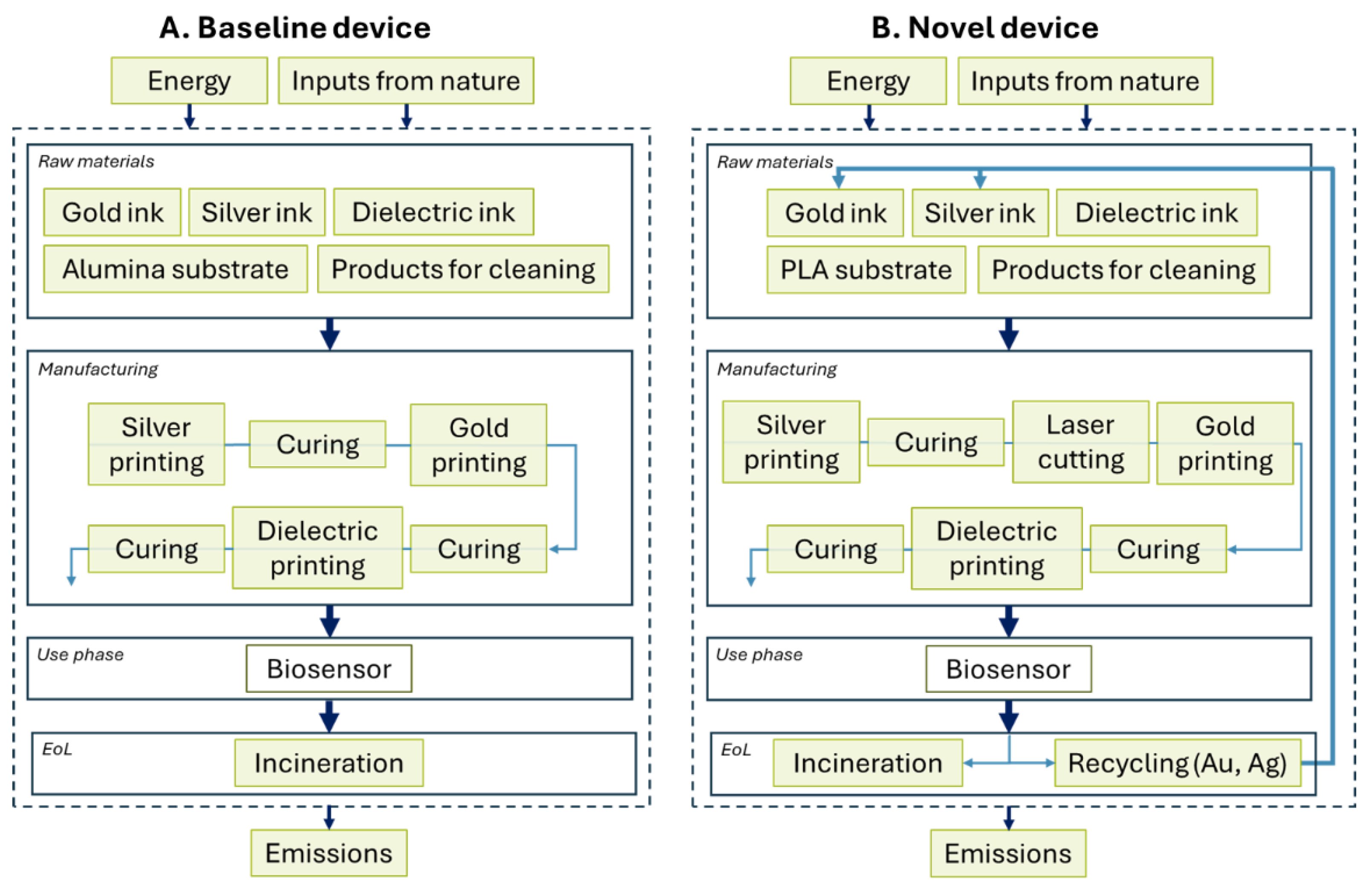

2.5. Design of Experiments

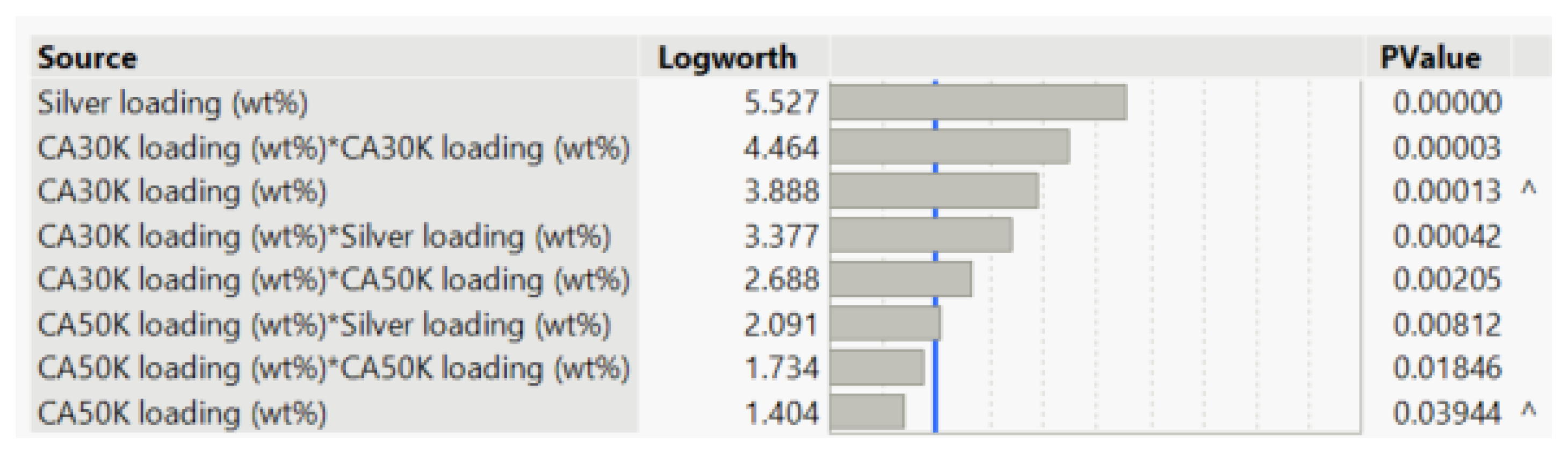

Design of Experiments (DoE) methods were used to accelerate the development and optimisation of the silver ink formulation. DoE can be used to create a data model of a formulation by carrying out a range of experiments to understand the effects of inputs (i.e., raw material loadings) on outputs (e.g., resistivity, viscosity). A response surface was designed in JMP (version 17.0) to provide a deep level of understanding of the formulation space and explore interactions between raw materials and non-linear phenomena. Twenty-four formulations were suggested by JMP with the inputs and outputs shown in

Table 1.

Results were fitted to a model to determine significant effects;

Figure 1 shows a summary of these effects where bars extending past the blue line are statistically significant. This table shows the inherent complexity of this formulation where inputs cannot be explored independently of one another.

The quality of fit can be assessed by checking actual-by-predicted plots shown in

Figure 2. Quality of fit is defined by R Squared (RSq), where highest is best; above 0.7 is a high-quality fit, and above 0.5 shows good quality. All responses achieved a high-quality fit.

2.6. PLA Substrate Preparation

PLA sheets were prepared using a single screw cast film extrusion line (Microex Cast, EUR.EX.MA Lab & Pilot Technology, Syncro group, Via Salvator Allende, 7—21049 Tradate (VA)—Italy). Prior to melt mixing, the samples were dried overnight under vacuum at 60 ºC. Processing temperature for PLA was set at 190 ºC for zones “cylinder 2”, “box”, and “lip”, “cylinder 1” was set at 180 ºC. The extrusion speed was 30 rpm, the first cylinder (calendar) was set to 0.1 m/min, 0.5 m/min for the second cylinder (haul off), and the third cylinder (winder) was set at 80% [

32,

33]. Stretch induced crystallisation was used to mimic biaxial stretching used in polymer substrate manufacturing, whereby a metal frame was used to clamp PLA sheets, promoting nucleation and growth of crystalline regions during annealing (S1, S2, S3, S4) [

34,

35].

2.7. Test Coatings & Basic Testing

To produce coatings for evaluation during the rapid screening of early formulations, a fixed gap was created using two lines of 50 µm thick tape adhered to a PET substrate. A microscope slide was then used to doctor the ink into the gap. Inks that were coated onto PET were dried in an oven at 120 ºC; PLA coatings were left to dry in air overnight. Coatings were assessed for sheet resistance and resistivity by measuring the current and resistance using a Keithley 2480 source meter attached to a four-point probe comprising 100 µm diameter pins with a 1-mm tip spacing, and by measuring thickness using a Hanatek FT3-Lab probe thickness gauge. Sheet resistance and resistivity were calculated using the equations shown in Gorman et al. [

37]. Adhesion was assessed by following ISO2409 using an Elcometer 1542 crosshatch test kit. Briefly, a crosshatch was created in the coating, tape (meeting the ISO2409 specification) was applied and then removed at a 45° angle. Finally, the amount of material that had been removed was visually assessed and quantified according to ISO2409.

2.8. Device Fabrication

Biosensors were designed to minimise the material required for fabrication, particularly with respect to the gold regions. The design incorporated three silver tracks of 1.2 mm wide and 31.75 mm long with a gap of 1.5 mm. The silver RE active area was 2.2 × 0.7 mm. Gold WE and CE active areas were 2.2 × 0.7 mm and 2.6 mm × 0.7 mm respectively. A gap of 0.7 mm was used between each electrode. Polyimide tape was used to isolate electrode areas on the fabricated devices.

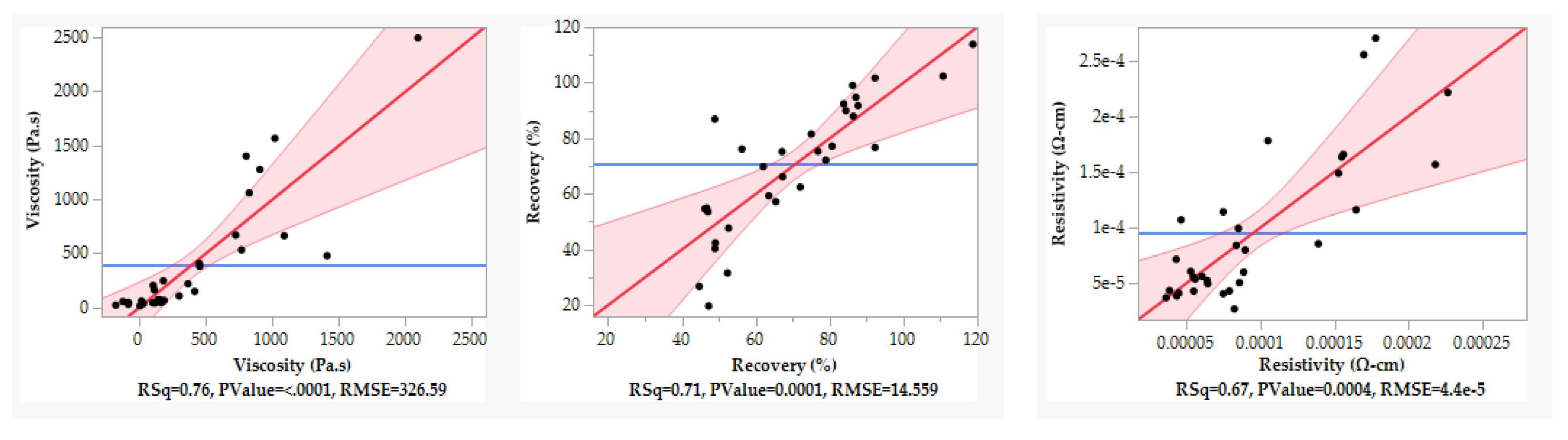

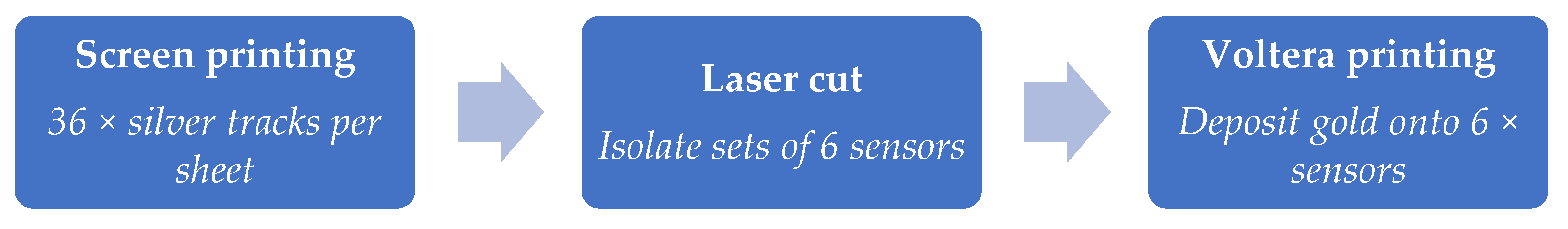

Novel devices were produced using a hybrid approach to balance scalability (screen printing) and material savings (digital printing), as shown in

Figure 3.

Screen printing was carried out using an ASM DEK Horizon 03iX and a squeegee with a shore A hardness of 70-75 and an angle of 45°. Silver tracks were printed using a polyester screen with a thread count of 120 threads per cm using threads with a diameter of 34 µm and a screen emulsion of 12 µm. The screen was flooded at a speed of 150 mm/sec and printing was carried out at 125 mm/sec with a print gap of 2.0 mm.

A Trotec Speedy 300 Laser was used to cut the individual sensors out of the larger sheet. A power of 18 W with a speed of 1 mm/sec was used for both polymer substrates.

Voltera printing was conducted using a Voltera V-One printer fitted with a 225 µm inner diameter metal dispensing tip. The printer was placed in a heated enclosure that was held at 30 ºC. The gold inks were preconditioned at 40 ºC and then loaded onto the Voltera V-One. The calibration cycle and printing began after a 5-minute equilibration. Printing was carried out with the following ink settings: pass spacing 0.2 mm, dispense height 0.15 mm, feed rate 350 mm/min, trim length 50 mm, trace penetration 0.15 mm, anti-stringing distance 1.0 mm, kick 0.35 mm, soft start ratio 0.2, soft stop ratio 0.15 and rheological setpoint 0.35.

2.9. Silver and Gold Recovery

Silver and gold flakes were recovered from two formats: 1) from waste ink formulations and single component printed samples, generated during ink and process development, and 2) from printed sensors containing both inks.

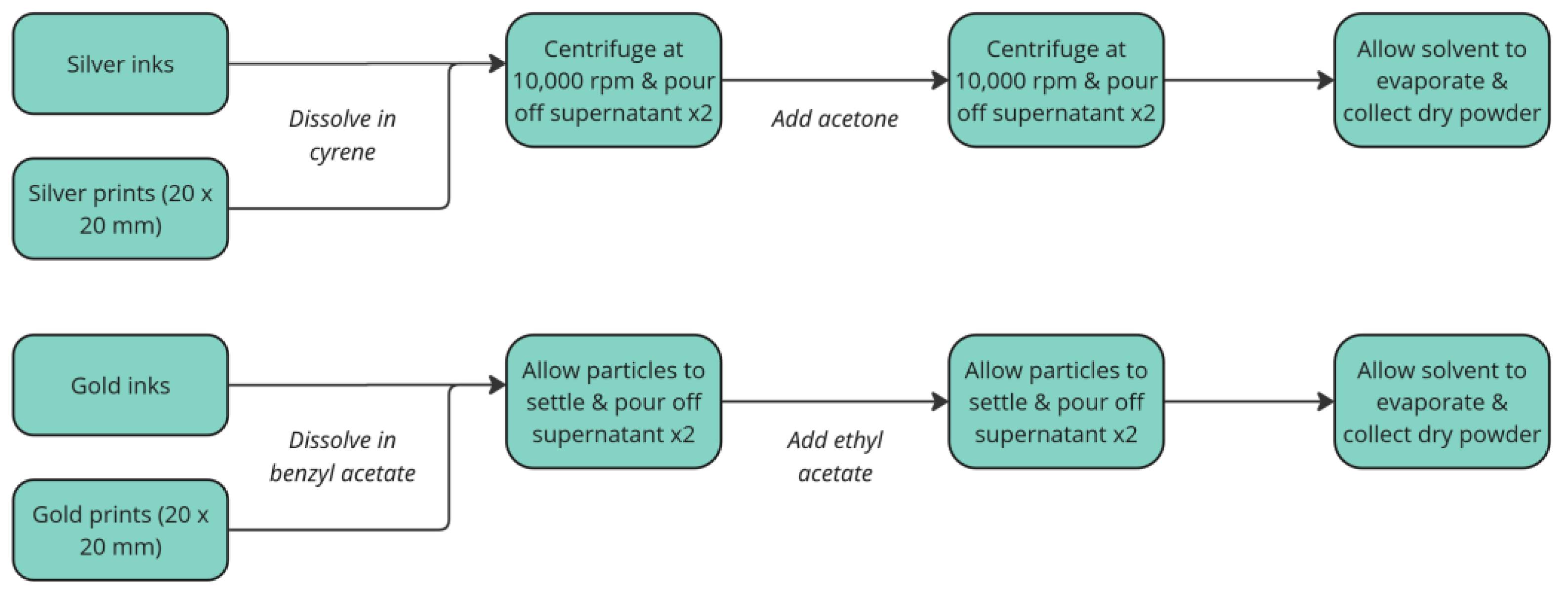

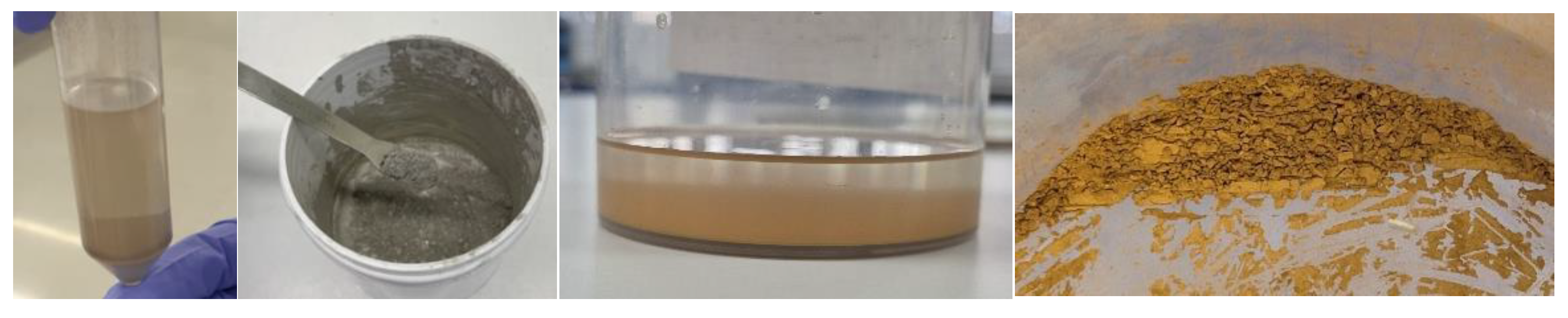

The processes used to recover silver and gold from samples in the first format is shown in

Figure 4. When recovering silver, centrifuge steps were employed using a Thermo Fisher Scientific, Sorvall Legend XFR at 10,000 rpm for 5 minutes. For gold recovery, washings were allowed to sediment under atmospheric conditions for 5 minutes. Fully washed samples were left in a fumehood overnight to allow any solvent to evaporate; the resulting powder could be easily loosened with a spatula.

For the second format, mixed metal coatings and devices, printed samples were cut into approximately 20 × 20 mm sections. Sequential washing steps were used to first recover gold, then recover silver. Cleaning steps used were as previously described;

Figure 5 shows an overview of the process.

2.10. ICP-MS

Analysis was performed using a Thermo Scientific iCAP-TQ ICP-MS operated in SQ KED mode. Samples were prepared by dissolving approximately 0.1-0.15 g in a minimal quantity of 70% nitric acid, prior to dilution with 2% w/w nitric acid (50 mL) to be within the calibrated range of the instrument. Instrument calibration was performed using a 23-element ICP standard sourced form Sigma-Aldrich, diluted with 2% nitric acid to give solutions in the range of 1-1000 ppb of silver (R2 of the calibration = 0.9992).

2.11. Enzyme Functionalisation

The screen-printed working electrode was functionalised with glucose oxidase (GOx) to enable selective detection of glucose. Prior to enzyme immobilisation, the electrode surface was rinsed with type 1 ultrapure water prior to applying a nitrogen flow to remove impurities and improve adhesion. GOx was immobilised onto the electrode by drop-casting the enzyme-water solution (2 µL of 10 mg/mL). Redox mediators were incorporated to facilitate electron transfer between the enzyme and the electrode surface; this was achieved by replicating a proprietary protocol used in the manufacturing of commercial Metrohm DropSens glucose sensors. The functionalised electrode was then dried under controlled conditions (40% RH, 25 ºC) and protected from light exposure. The sensor could be used immediately or stored in a refrigerator at 4 ºC and protected from light until required. This modification allowed the electrode to act as a biosensing platform, where the enzymatic oxidation of glucose generates an electrochemical signal proportional to its concentration.

2.12. Electrochemical Testing

All electrochemical measurements were performed with µStat-i M8ONE multichannel impedance analyser from Metrohm DropSens controlled by DropView 8400M software (version 2.1.19). To obtain the electrochemical analytical signals, aliquots (30 µL) of the indicated solution for each methodology were deposited onto the three-electrode system of the screen-printed electrodes (SPE).

Cyclic voltammetry was carried out at 450 mV to -300 mV potential at different scan rates (5, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 250, 500 mV/s to determine the electroactive surface area, using K3 [Fe(CN)6] as the analyte. EIS experiments were performed at open circuit potential with 10 mV amplitude potential in a frequency range between 100,000 and 0.01 Hz in a 1 mM ferrocyanide/ferricyanide 100 mM KCl solution. Chronoamperometry was carried out by applying a detection potential of +0.3 V for 60 seconds with different glucose concentration solutions from 1 to 100 mM in 100 mM TRIS pH 7.2 buffer solution.

The electrochemical results obtained with the SPE developed in this work were compared with those obtained using DRP-220BT (Metrohm DropSens) SPEs, customised to match the electrode geometry of the devices fabricated in this study, named from this point forward as the baseline device (Base0).

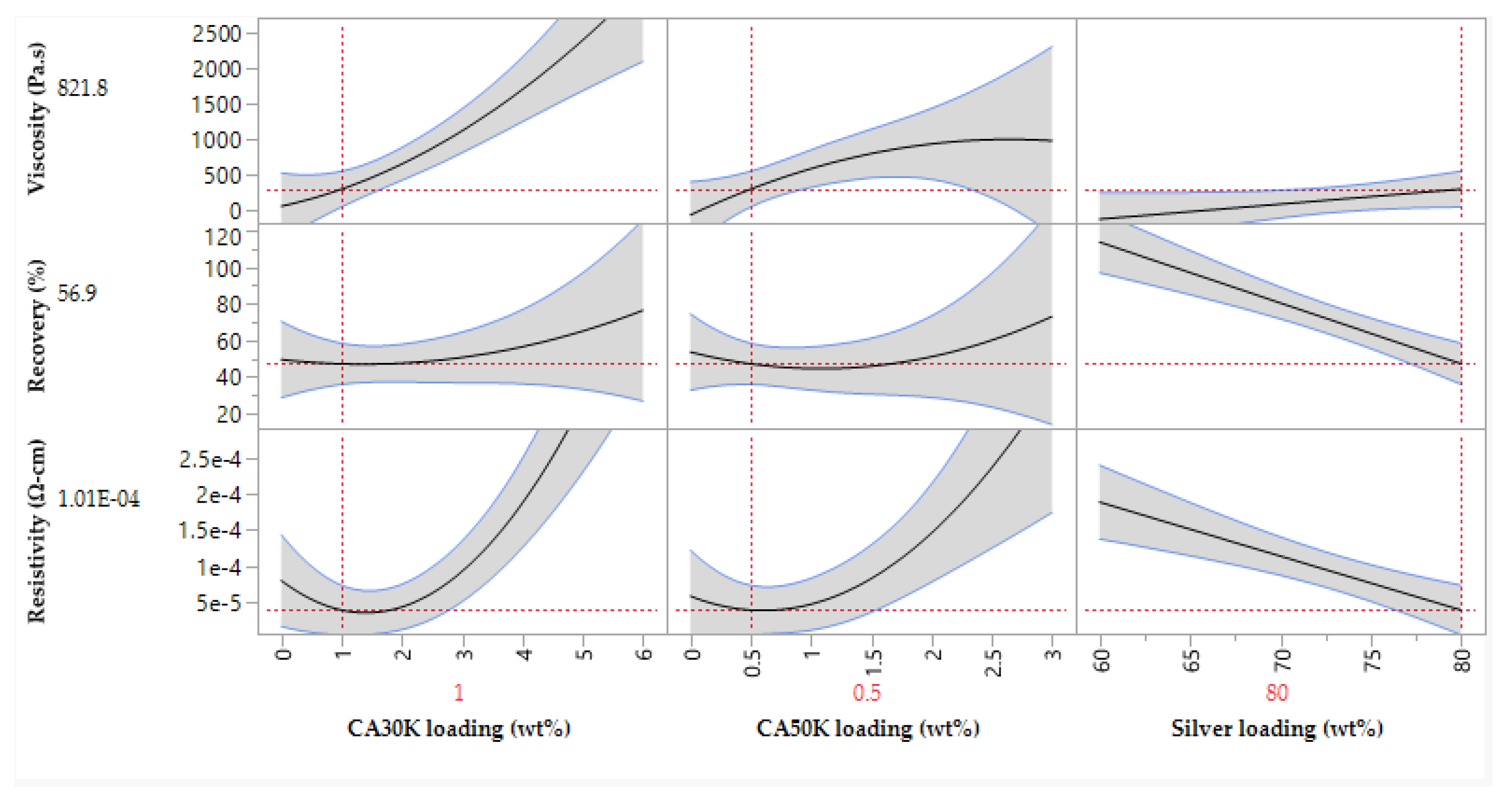

2.13. Life-Cycle Assessment

A Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) was conducted to quantify and compare the potential environmental impacts of the novel device that incorporated circular innovations against the baseline device that follow a linear economy model. LCA is the most widely accepted methodology to evaluate the environmental burdens of a defined system, either a product or a process. The LCA presented herein was conducted by following ISO 14040/14044 guidelines, which included four phases: (1) goal and scope definition, (2) inventory analysis, (3) impact assessment, and (4) interpretation [

24,

25].

The goal and scope definition determined the guidelines to be followed during the rest of the study by specifying the reason for conducting the study, intended use of the results, system boundaries, functional unit, data requirements, and study limitations. The inventory analysis involved collecting data to create a Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) of the inputs (energy and materials) and outputs (environmental releases and waste) associated with each stage of the life cycle. The impact assessment translated the LCI data into potential environmental impacts, using predefined impact assessment methods that incorporate characterisation factors for diverse environmental impact categories (e.g., climate change, acidification, eutrophication, human toxicity, etc). Finally, the interpretation phase combined and summarised the results from inventory analysis and impact assessment (consistent with the defined goal and scope) in order to reach conclusions and recommendations. In brief, LCA involves a material and energy balance applied to the product’s system, combined with an assessment of the environmental impacts related to the input and outputs to and from the product system.

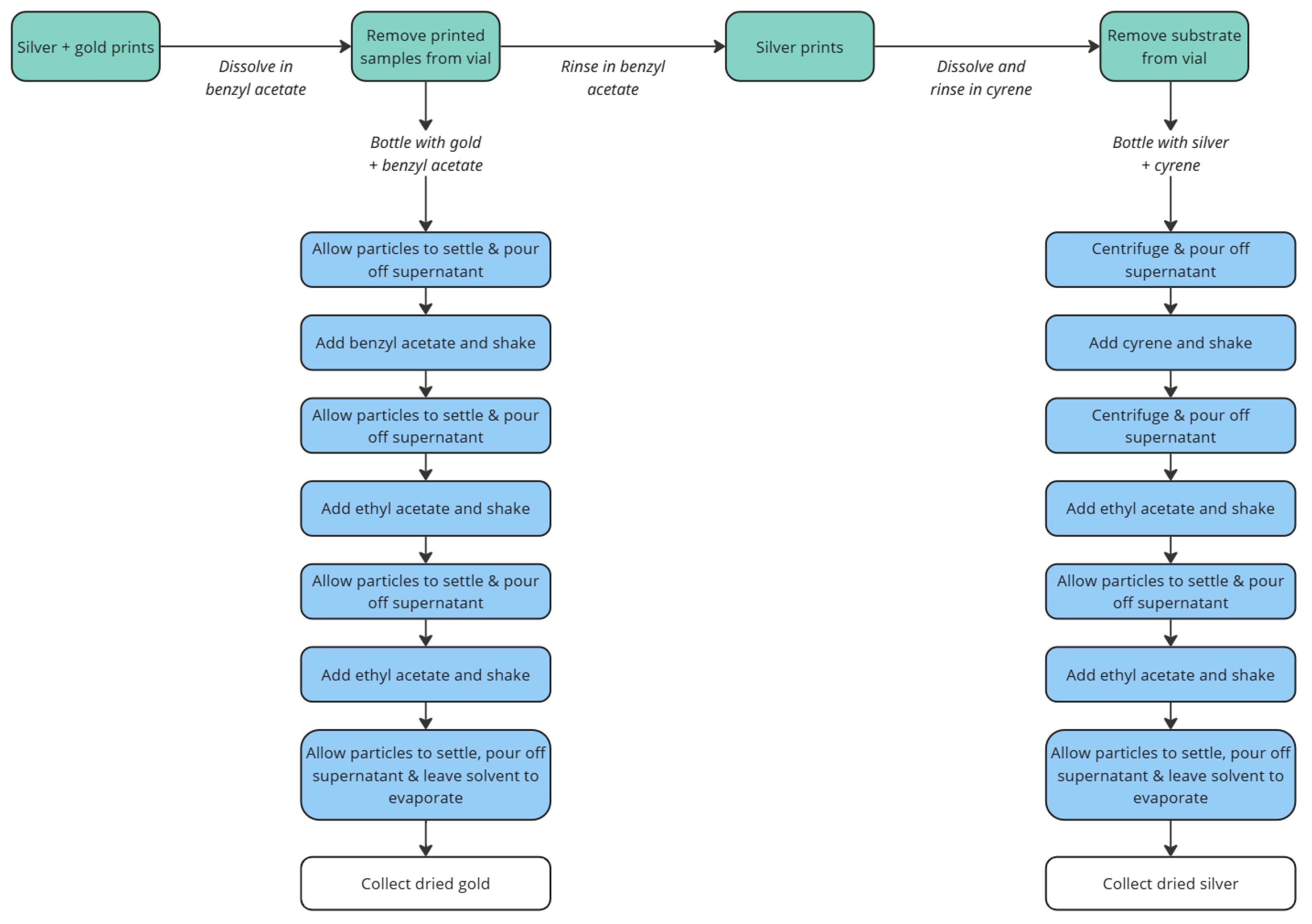

In the present study, the functional unit was defined as one biosensor, both for the novel and for the baseline devices. The scope was cradle-to-cradle, meaning that the study covers the totality of the life cycle, from raw material extraction, through fabrication of the device components and their assembly, up to the end-of-life (EoL) treatment, including the recovery and re-use of materials to produce new devices (in the case of the novel device). The system boundaries are presented in

Figure 6. Note that in this case a dielectric ink was not incorporated into the physical device, however it was included in the LCA to provide a fair comparison to the baseline device.

The materials and energy inventory in section 3.7 was based on primary data. For background processes for which primary data was not available (e.g., raw materials or electricity production), secondary data were taken from the Ecoinvent database (version 3.10) [

40] and/or modelled using literature data and stoichiometry-based method proposed by Langhorst et al. [

41]. The impact assessment method used to convert the inventory data into environmental impacts was the Environmental Footprint (EF, version 3.1) [

18], as incorporated in SimaPro software. EF 3.1 was used to assess 16 environmental impact categories at the midpoint level, including climate change (CC), ozone depletion (OD), ionszing radiation (IR), photochemical ozone formation (POF), particulate matter (PM), non-carcinogenic human toxicity (HTNc), carcinogenic human toxicity (HTc), acidification (A), eutrophication freshwater (Ef), eutrophication marine (Em), eutrophication terrestrial (Et), ecotoxicity freshwater (E), land use (LU), water use (WU), fossil resource use (RUF), mineral, and metal resource use (RUMM).

3. Results

3.1. Ink Binder Selection

When selecting materials several factors were considered: safety, solvent compatibility, and sustainability e.g., bio-based, bio-derived or biodegradable. Selective solubility of the ink binder was particularly important due to the intended goal of solvent-based recovery of silver and gold inks from the same device. It was therefore crucial that the silver ink was insoluble in at least one solvent that the gold ink was highly soluble in, and vice versa.

Using this criteria, cellulose acetate (CA) was selected for the silver ink due to the bio-derived nature of this polymer and its potential for degradation under industrial composting conditions [

42]. CA is a hydrophobic polymer not soluble in commonly used polar solvents such as alcohols and esters, yet it was found to be readily soluble in green-solvent cyrene [

43]. For the gold ink, polycaprolactone (PCL) was selected due to its well documented biodegradability [

44] and solubility in benzyl acetate—a bio-based solvent that can be produced via microbial fermentation [

45]. Furthermore, both polymers boast the advantage of a non-hazardous classification. With respect to the solvents, cyrene is an eye irritant, and benzyl acetate poses environmental hazards [

46]. Despite this, all chemicals were deemed suitable for use in commercial printing environments, which typically lack sufficient engineering controls, such as localised ventilation, to handle toxic chemicals.

3.2. Silver Ink Development

A silver ink was developed using the DoE outlined in section 2.5 and resultant experimental data was used to build a digital model of the formulation, enabling prediction of future experiments. JMP incorporates a ‘profile predictor’ which allows for prediction of properties for a suggested formulation, or the desired properties can be defined, and the model will predict a formulation to achieve those properties.

Figure 7 shows an example of the profile predictor.

This method also allowed for key trends to be identified. CA30K and CA50K loading had a proportional relationship to viscosity, where increasing loading resulting in a higher viscosity. Increasing the silver loading resulted in poorer viscosity recovery, while increasing CA30K and CA50K content improved viscosity recovery, likely due to polymer entanglement i.e., polymer chains partially wrapping around one another to create a ‘spring-like’ effect to retain the molecular structure of the ink during printing [

47]. Resistivity was increased by increasing the CA30K and CA50K content due to the higher proportion of non-conductive components in the ink. Conversely, silver loading decreased ink resistivity by resulting in a higher degree of particle-particle contacts between conductive flakes to achieve high percolation i.e., sufficient contact between flakes to allow electrons to flow from one flake to another [

48].

The model suggested a formulation containing 2.35 wt% CA30K, 0.67 wt% CA50K and 62 wt% silver. This ink was produced and characterised; predicted and experimental values were comparable.

Table 2.

Comparison of predicted and experimental values for the suggested final formulation.

Table 2.

Comparison of predicted and experimental values for the suggested final formulation.

| Ink parameter |

JMP17 predicted formulation |

Experimental data |

| Ink viscosity @ 1.5 s−1 (Pa.s) |

44.5 |

41.5 |

| Viscosity recovery (%) |

83.1 |

87.6 |

| Resistivity (Ω·cm) |

5.66 × 10−5

|

5.30 × 10−5

|

3.3. Gold Ink Development

Due to the high cost of gold, it was unfeasible to carry out a DoE to fully optimise the ink. Polycaprolactone 10 kDa at 20 wt% loading in benzyl acetate (PCL10K) and PCL 80 kDa at 10 wt% loading in benzyl acetate (PCL80K) were combined at 1:2, 1:1 and 2:1 ratios to achieve sufficient viscosity while minimising stringing behaviour, where a 2:1 ratio gave the best visible results. Stringing is a phenomenon that occurs due to the entanglement of polymers chains at a molecular level. It is commonly encountered in inks that contain high molecular weight polymers, where disentanglement is impossible [

49]. This can cause significant issues for additive processes, where ink detachment from the nozzle is crucial to preventing defects in the print.

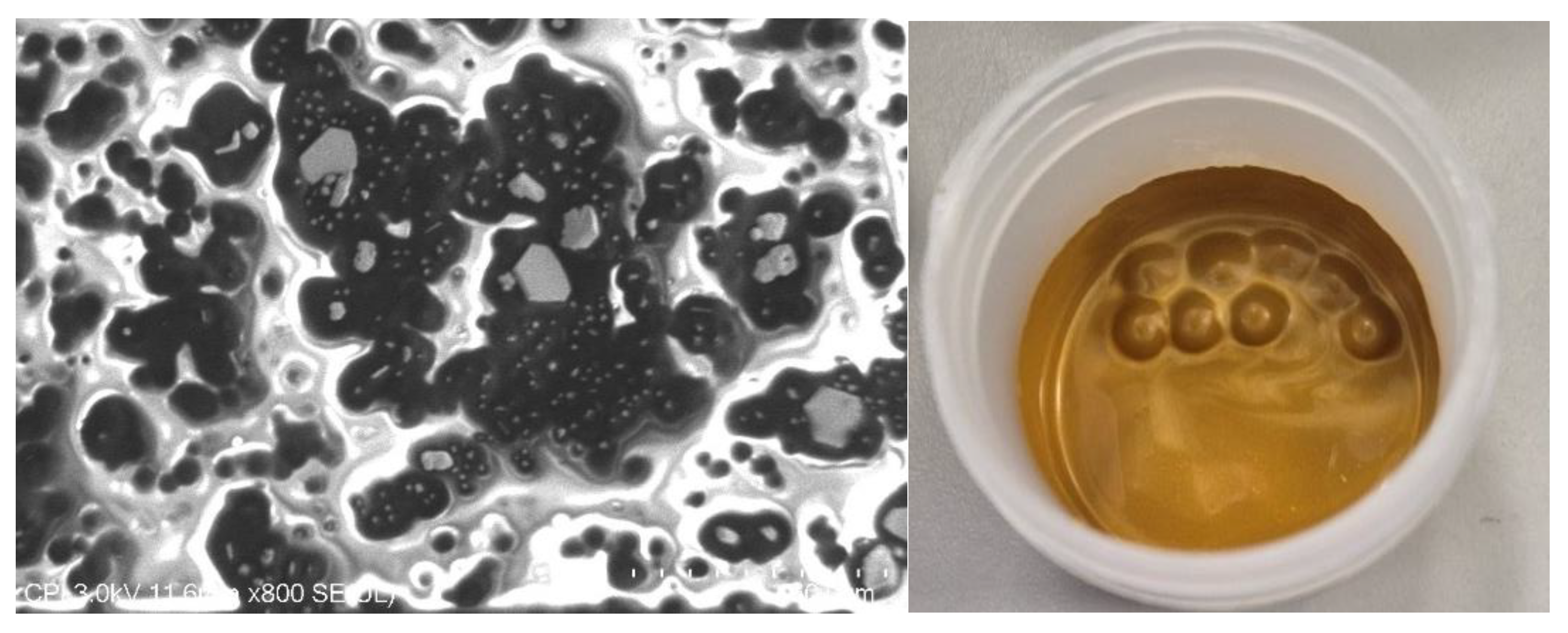

Gold was added initially at 75 wt%, 80 wt% and 85 wt% loading and the ink was DAC mixed; however, none of the inks exhibited conductivity. Scanning electron microscopy was carried out to determine whether there was sufficient contact between gold flakes to enable percolation.

Figure 8 (left) shows an image where particle agglomeration and regions of pure polymer, i.e., non-conductive regions, were evident. This suggested deagglomeration was required through higher intensity mixing methods. While several methods exist, such as three-roll milling, this method requires high volumes of ink (at least 25 g), and the rollers present a high chance of contamination when used in an R&D environment. A more feasible solution was the use of stainless-steel ball bearings in a DAC mixer pot (

Figure 8, right) to increase deagglomeration while working with low volumes of ink and minimising risk of contamination. Note that issues of contamination and ink volume are unlikely to translate to industrial manufacturing, therefore three-roll milling could be a viable commercial option.

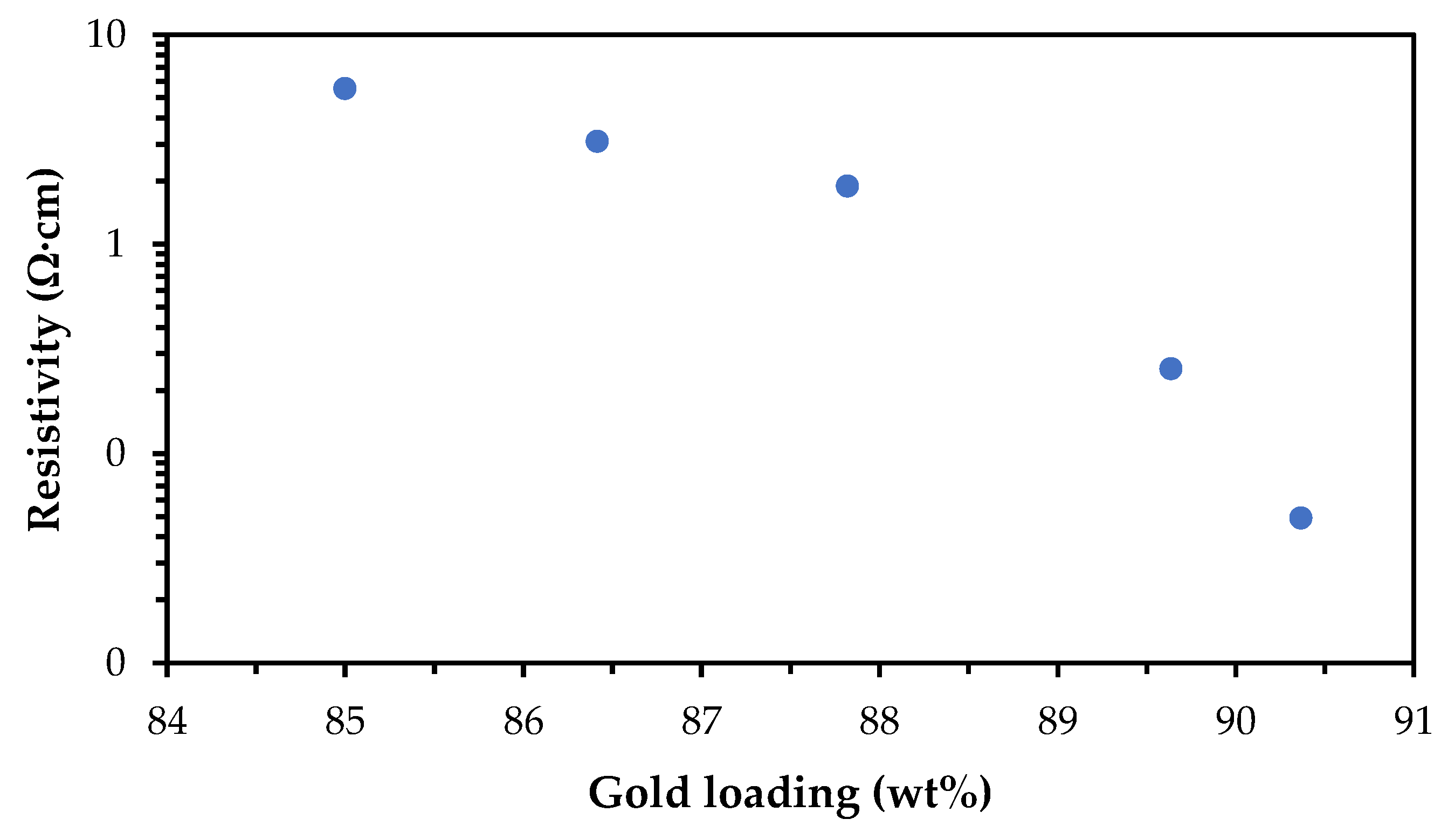

Following the mixing improvements, the ink containing 85 wt% gold flake was found to be conductive. The conductivity was optimised for the target application by increasing the gold loading to 90.5 wt%, which achieved a resistivity of 4.92 × 10

−2 Ω·cm (

Figure 9).

3.4. Silver and Gold Recovery

A key goal of this work was to recover and reuse silver and gold from the metallic components of a fully fabricated electronic device. In this situation, the conventional method of recovery would involve the chemical leaching of metallic salts and then subsequent resynthesis into particles or flakes. This is a long, expensive, and complex process [

14]. Given that this work had full control of the ink components, closed-loop recycling using a solvent extraction process was developed.

The process outlined in section 2.9 was initially carried out on waste inks generated during development work and test substrates where only one ink type, either silver or gold, had been printed. The recovered silver and gold powders were found to be contaminant free when analysed by ICP-MS, with 100% of the recovered mass attributed to either silver or gold.

Figure 10 shows images of silver sediment, dried powder, gold sediment, and gold powder from left to right.

Both recovered metal powders were then used to produce second generation inks which demonstrated near identical electrical performance,

Table 3. However, a reduction in viscosity recovery for the silver ink was notable. The silver flake used in the ink formulation is known to be coated with low molecular weight molecules to enhance the rheological stability and prevent sedimentation. It was hypothesised that the recycling process had removed this organic coating from the silver flake’s surface, therefore altering the intermolecular interactions between the silver flake and surrounding polymer solution, and the inks resultant rheology. Furthermore, the reduction in resistivity of the silver and gold inks would support this hypothesis.

To demonstrate the selective solubilities of the silver and gold polymeric binders, substrates that contained both silver and gold inks were separated using the sequential washing steps outlined in section 2.9. The recovered silver powder was found to be pure, containing 100% silver. Conversely, a small amount of silver contamination (1.03%) was found in the recovered gold powder, as measured by ICP-MS.

Both virgin and recycled silver inks were compared to a commercial equivalent (

Table 4). Novel inks showed slightly increased resistivity relative to a commercial counterpart at equivalent silver loading and curing temperature.

Gold inks were compared with a commercially available screen ink, as no commercial gold ink that was compatible with the Voltera printer existed. The ink that was developed within the project achieved a significantly higher resistivity due to sintering (i.e., melting of nano-sized metallic particles into a uniform film [

51]) not being employed, therefore conductivity relied on percolation between flakes (

Table 5). However, the drying and sintering temperatures for the commercial ink were significantly higher, resulting greater energy usage.

3.5. Sensor Fabrication

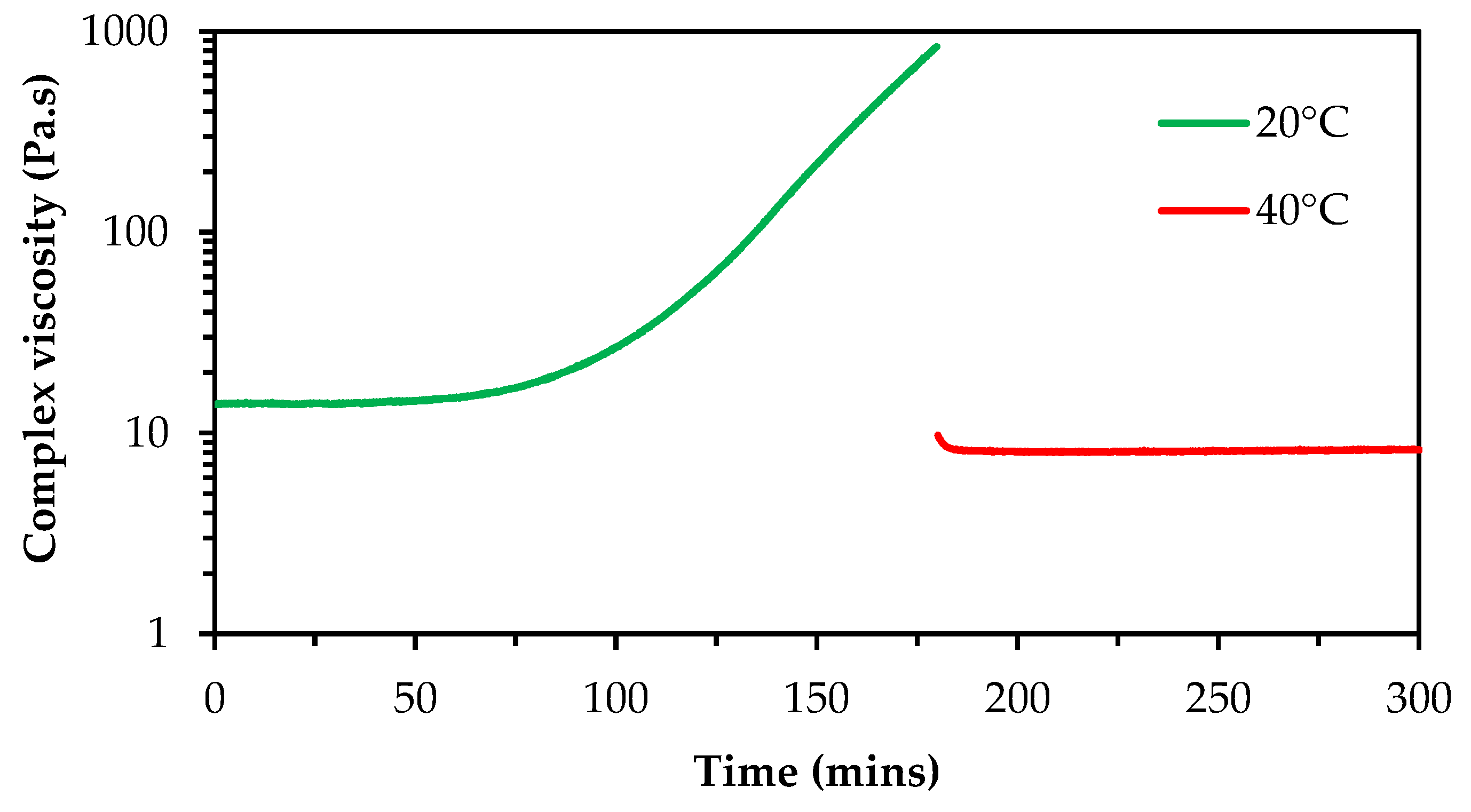

Virgin and recycled silver inks were screen printed to produce base electrodes; no notable differences between the two inks were observed during printing. The virgin gold ink was printed using the Voltera V-One where print settings were modified to achieve high reproducibility and ink coverage i.e., no gaps in the printed pads. However, variability in print performance over time was noted, resulting in the nozzle becoming blocked after an hour of printing. This was attributed to the ink solidifying in the syringe during printing. This was also observed when inks were left in ambient conditions in a sealed sample vial for an hour after mixing, therefore it was hypothesised that this change was due to the ink cooling rather than a result of shearing occurring during printing. To quantify this change and ascertain the effect of reheating the ink, the base polymer solution was analysed using rheology whereby the same sample was assessed at 20 °C and subsequently heated to 40 °C. It was noted that a significant increase in viscosity occurred after 1 hour (

Figure 11, green line), which limits the useability of the ink. However, heating the sample had an immediate and notable effect on reducing the viscosity and maintaining viscosity over a useful time period (

Figure 11, red line).

Clearly, it was desirable to print the ink while in a heated state. Unfortunately, the Voltera V-One printer does not possess the capability to heat the ink-filled syringe during printing. Therefore, the printer was housed inside of a heated enclosure. This resulted in significantly improved reproducibility of the printed sensors and allowed printing to be carried out over the course of four hours, without the print performance suffering or failing.

Optimisation of the sensor print settings focused on the anti-stringing distance, feed rate, and dispense height [

53]. Anti-stringing distance can be used to increase the distance the syringe raises from the substrate when moving between print regions to ensure no excess material remains attached to the nozzle. Failure to correctly optimise this setting can result in bridging between printed areas, leading to electrical shorts in the printed device. Feed rate and dispense height were interdependent; high feed rates usually require a low dispense height to ensure complete coverage, and low feed rates benefit from a high dispense height to minimise material build up and overprinting.

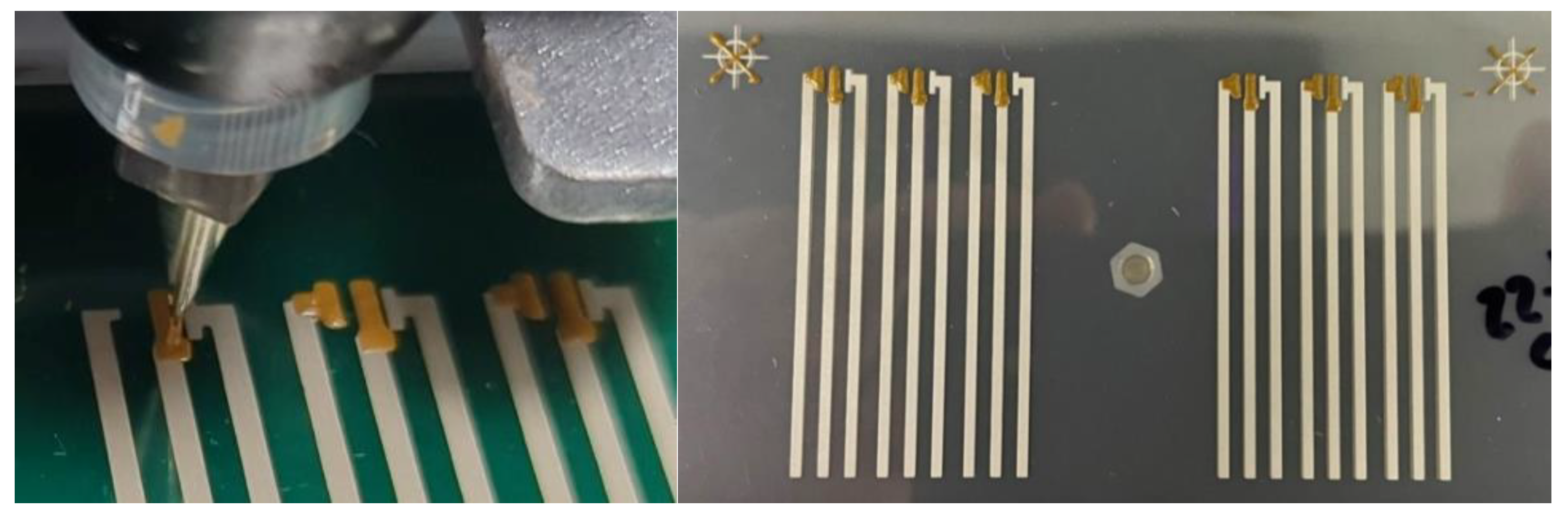

Devices were produced using the settings shown in section 2.8 with virgin and recycled gold ink, onto virgin and recycled silver electrodes, on PET and PLA. The same print settings were used for all device variations. Final devices showed gold pads to be well defined and no stringing was observed, as shown in

Figure 12.

Four sets of devices were fabricated: i) Sensor1—PET with virgin Ag and Au inks, ii) Sensor2—PET with recycled Ag and Au inks, iii) Sensor3—PLA with virgin Ag and Au inks, and iv) Sensor4—PLA with recycled Ag and Au inks. Note that adhesion was comparable for inks on both substrates where an ISO crosshatch test revealed no ink could be removed (ISO classification 0). This was significant because PET contained an adhesion promoter and the PLA did not.

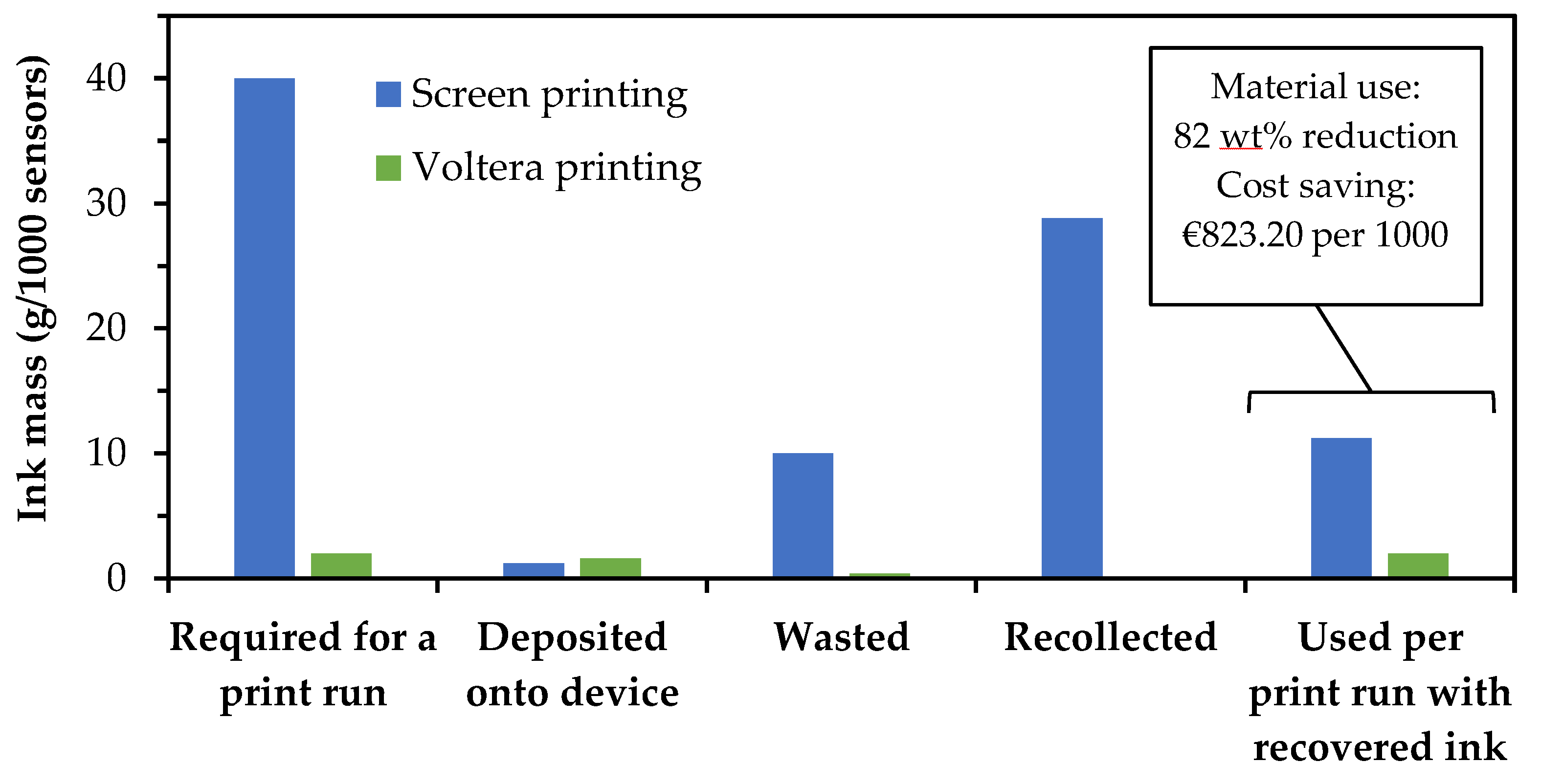

Printed biosensors are fully screen printed when manufactured commercially; therefore, a desk-based evaluation was carried out to compare ink usage for screen printing and Voltera printing to assess commercial viability. The mass of ink used and lost was recorded at each stage of a commercial 1000 device biosensor screen print run using a commercially available gold screen ink: i) ink applied to the screen at the start the process, ii) ink recovered after printing 1000 devices, iii) ink mass applied to the substrate, iv) calculated the ink wasted. The losses during Voltera printing of 18 devices were also weighed and recorded at the following stages i) ink lost during transfer from DAC pots to the syringe, ii) ink applied to the substrate, and iii) calculated ink remaining in the syringe that was not possible to recover. These values were extrapolated to 1000 devices to enable a fair comparison.

Figure 13 shows the comparison where the final column represents the significant drop in material usage when factoring in the amount of ink recovered from the screen after printing. This material saving was converted to a cost saving using a gold price of €89,46 per gram, as quoted by Metalor on 17/10/2024.

3.6. Functionalisation & Electrochemical Testing

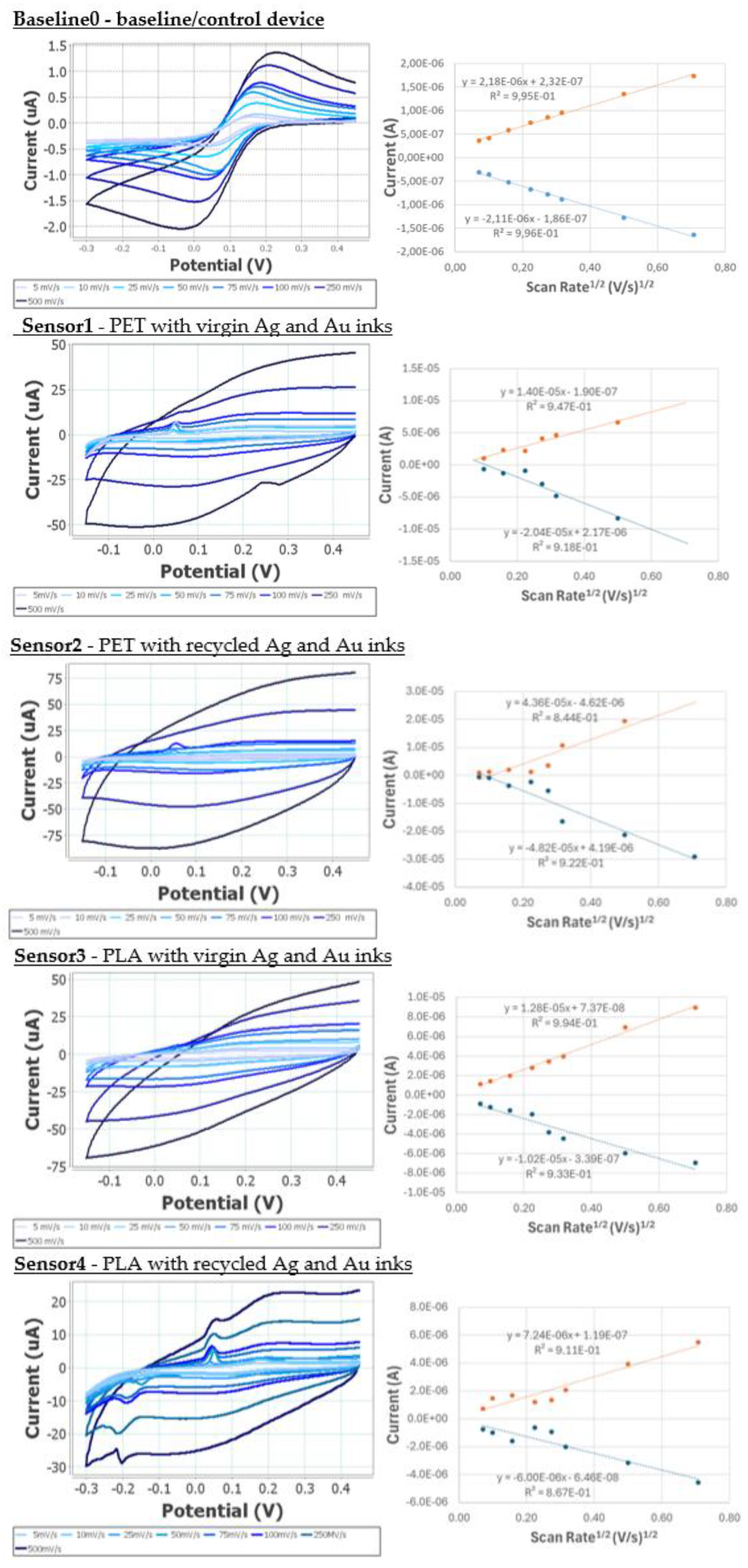

Novel and baseline biosensors were evaluated using electrochemical test methods to determine their performance as glucose biosensors. Cyclic voltammetry was employed to calculate the electroactive area of the working electrode according to the Randles-Ševćik equation ((Eq.

1) [

54]. This parameter is crucial for understanding and optimizing its analytical performance, as this parameter determines the effective amount of surface area available for electron transfer between the electrode and the analyte, in this case K

3 [Fe(CN)

6]. A larger electroactive area generally translates into a higher density of active sites, which increases sensitivity and improves the kinetics of electrochemical reactions. In the case of screen-printed electrodes, it is necessary that the electroactive area of the different screen-printed electrodes be as similar and reproducible as possible.

Where,

Ip is the peak current of redox couple,

n is the number of electrons participating in the redox reaction,

A is the electroactive surface area (cm

2),

D is the diffusion coefficient of K

3 [Fe(CN)

6] in the solution (cm

2 /s),

C is the concentration of K

3 [Fe(CN)

6] in the bulk solution (mol/cm

3), and

ν is the scan rate (V/s).The electrode areas calculated using the Randles–Ševćik equation and cyclic voltammetry were undertaken with 8 different scan rates (5, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 250, and 500 mV s

−1),

Figure 14.

Once the voltametric study of the electrodes at different scan rates was carried out, the current peak height was calculated. This was done for both the anodic and cathodic peaks, and calibration curves were created representing the square root of the scan rate versus the current. From the equation of the curve for each of the peaks and Randles- Ševćik equation (Eq.

1), the electroactive area of the electrode can be obtained.

Table 6 shows the results of the average of the values obtained for the electroactive area and variability for each of the electrodes studied compared to the theoretical geometric area.

All novel devices exhibited a higher electroactive surface area, potentially due to the increased surface roughness created by using flakes rather than a smooth sintered surface. The variability observed for the novel devices was higher than the baseline device, and significantly higher for the PET when compared with PLA.

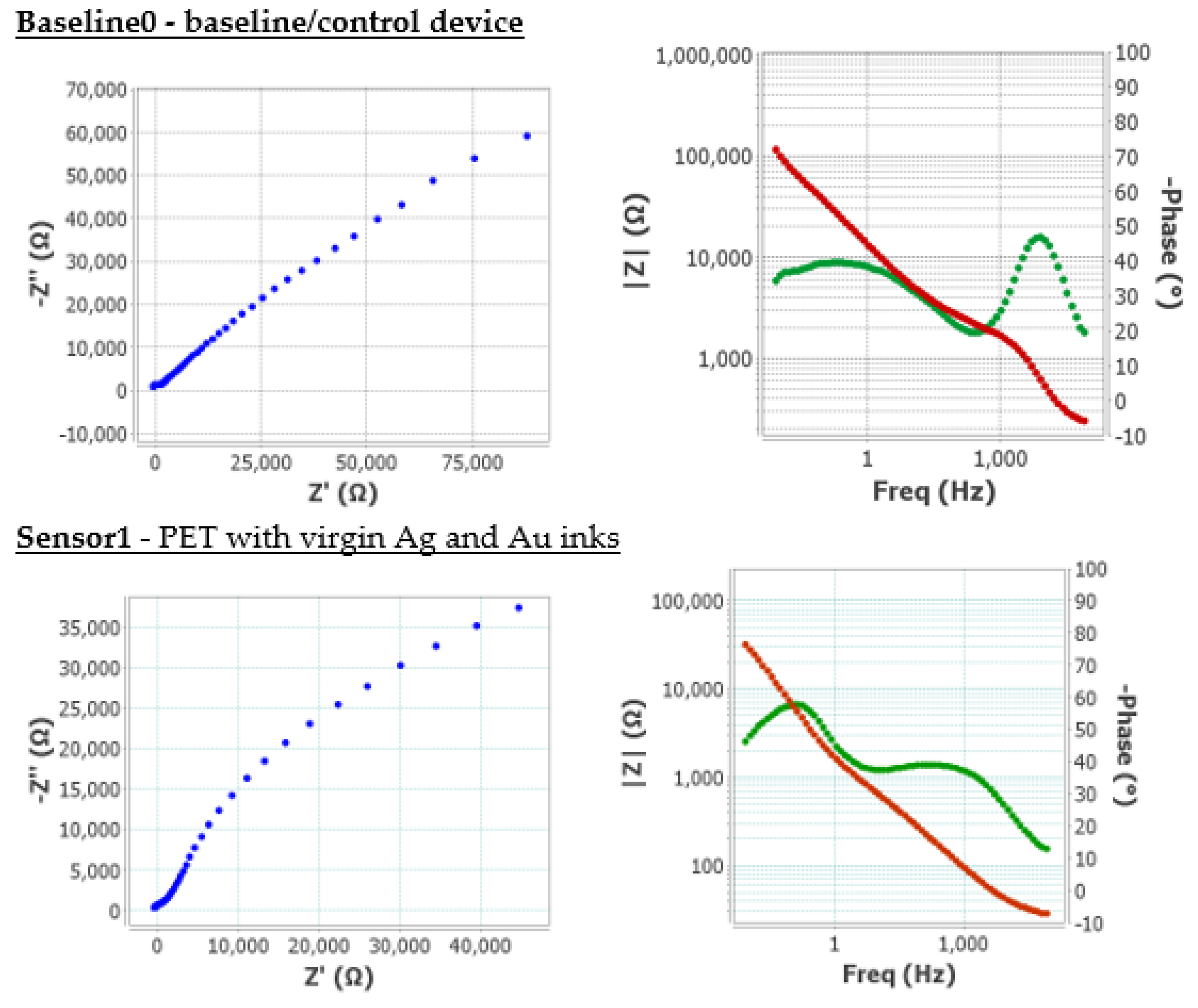

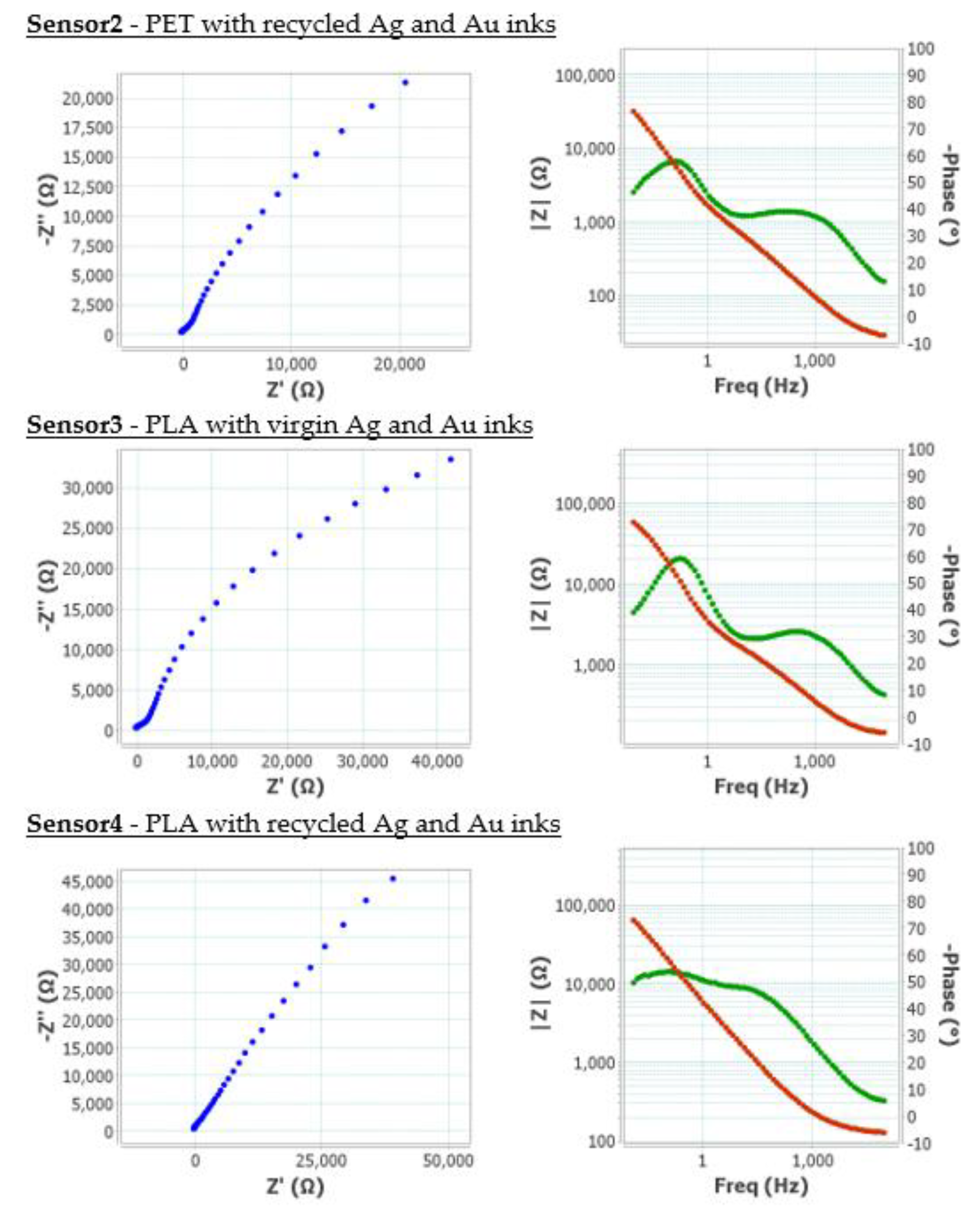

Furthermore, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was employed to characterise the behaviour of the developed screen-printed electrode. This technique provides detailed insights into the processes occurring at the electrode-electrolyte interface, such as charge transfer, double-layer formation, and ionic diffusion. By fitting the impedance data to equivalent circuit models, key parameters including solution resistance, interfacial capacitance, and charge transfer resistance were extracted, offering a comprehensive evaluation of electrochemical performance of the electrode,

Figure 15.

Once the electrochemical performance of the electrochemical transducers had been validated, the biosensor was functionalised with GOx using the method outlined in section 2.11. The biosensor consisted of the modified transducer with the sensing phase containing the recognition element, in this case GOx. This characterisation aimed to determine if the electrochemical sensor would function as a glucose biosensor. During the electrochemical detection of glucose, the analyte underwent enzymatic oxidation catalysed by GOx, resulting in the formation of H

2O

2 following the chemical reaction (Eq.

2). The generated H

2O

2 by the enzymatic reaction was subsequently detected at the electrode interface, generating a quantifiable current response.

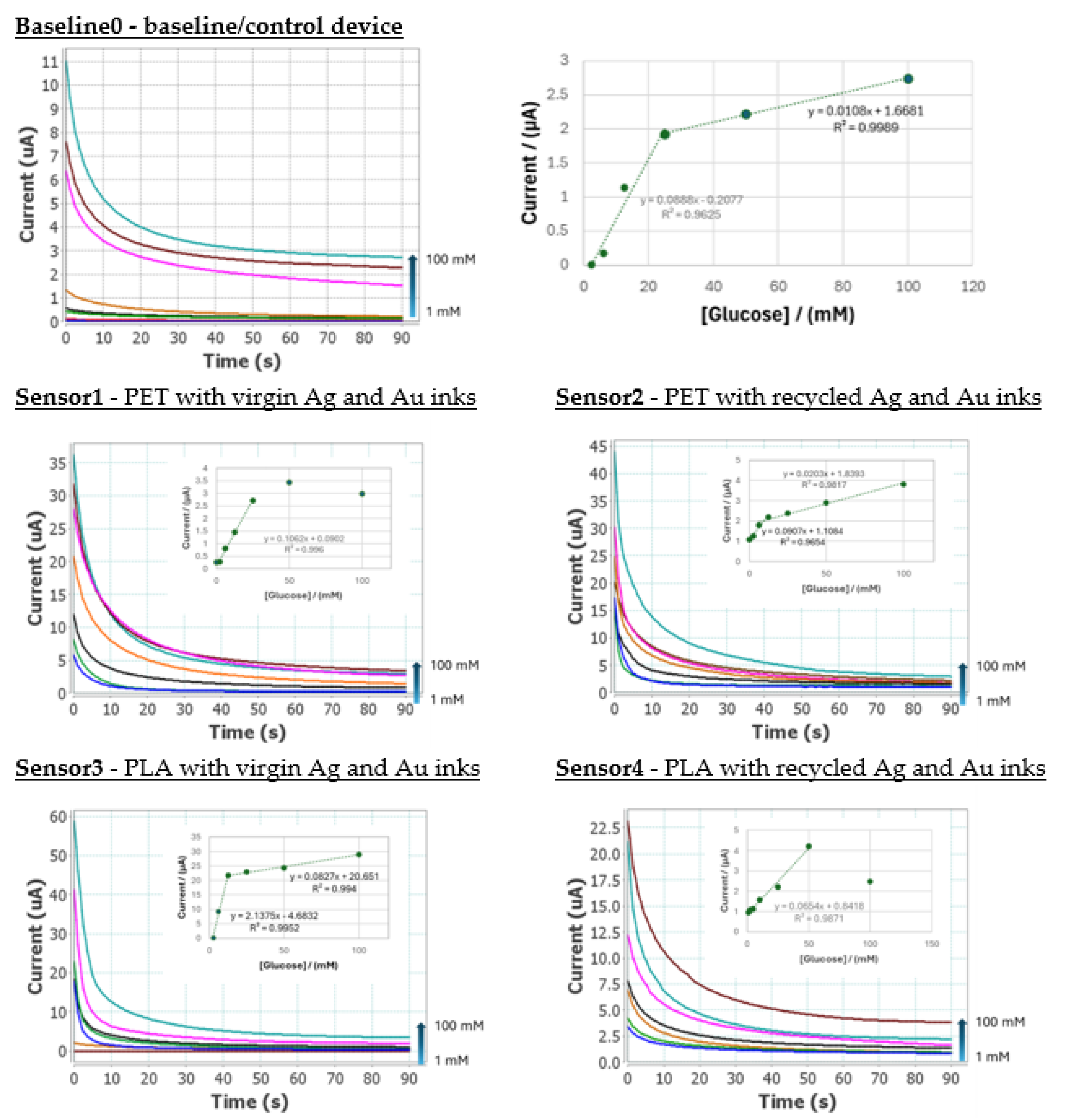

To obtain the analytical signal a drop of 30 µL of glucose solution at different concentrations was place on the electrode surface and evaluated by chronoamperometry. This applied a detection potential of +0.3 V for 60 seconds with different glucose concentration solution from 1 to 100 mM in 100 mM TRIS pH 7.2 buffer solution,

Figure 16.

3.7. Environmental Impact Assessment

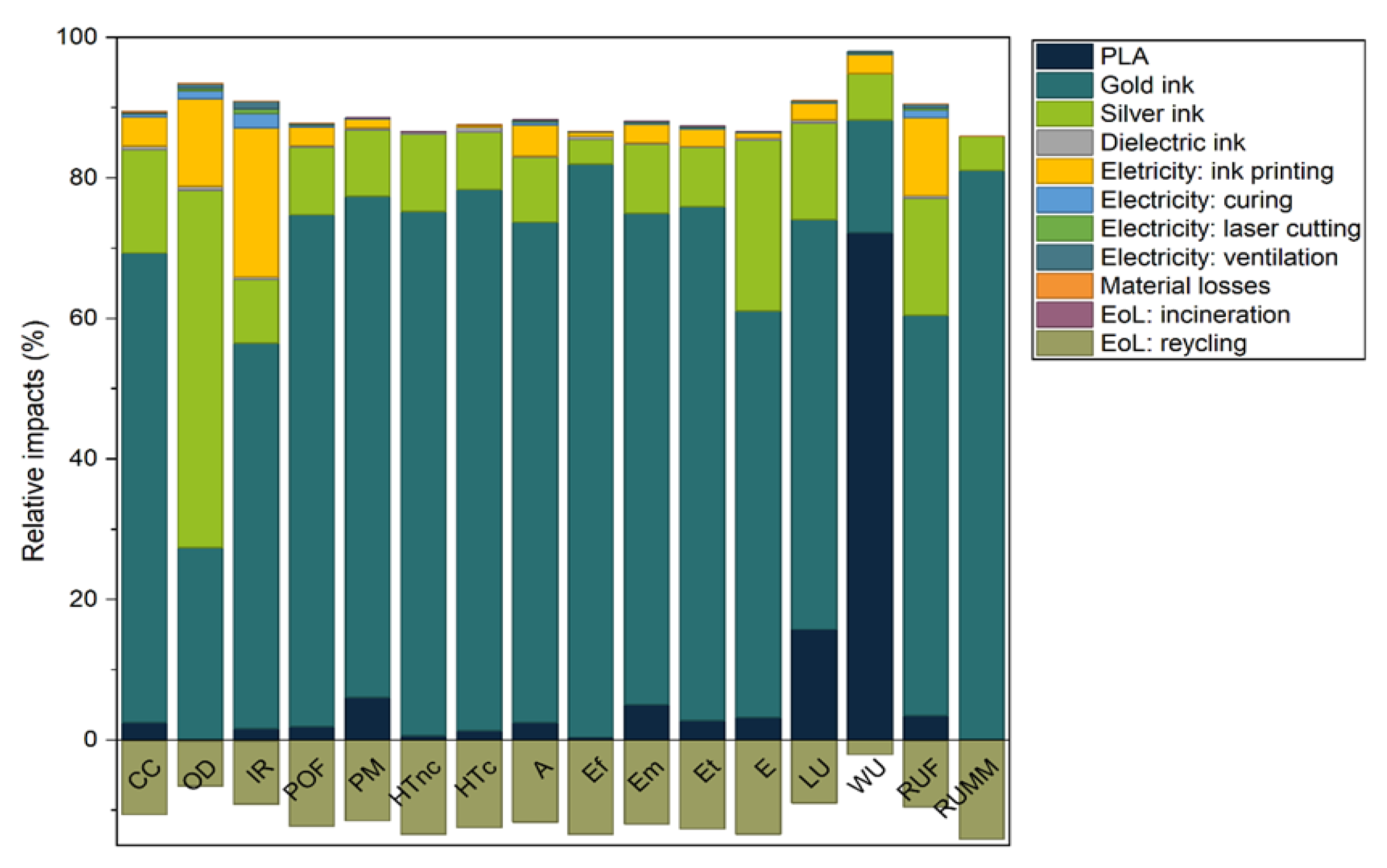

A full LCA was carried out from cradle-to-grave to compare these new innovations to a commercial baseline, based on the inventories collected for both baseline and novel devices. In

Table 7, the differences in material and processes are highlighted. The alumina substrate was replaced by a biobased PLA substrate in the novel device (requiring a new cutting step), the cleaning agents used for manufacturing were modified and a different curing method was considered. Due to a redesign of the biosensor, the quantities of substrate, inks and the overall weight of the device were reduced.

Figure 17 presents the main impact contributors of the novel device from the comparative LCA study. It was clear that the gold and silver inks were the main hotspots, accounting for up to 81% and up to 51%, respectively, of the total impacts depending on the categories. PLA was the main contributor towards water use (WU), with 72% of total impact. This was due to its biobased origin, which requires large volumes of water for biomass growth. The electricity consumed for ink printing had a limited contribution to the total impacts, while the impact contributions from dielectric ink, electricity for laser cutting and ventilation, material losses, and incineration at EoL were negligible. Negative impacts (or environmental credits) due to EoL recycling of devices were attributed to the novel recycling process presented herein, therefore reducing the need to extract fresh metals.

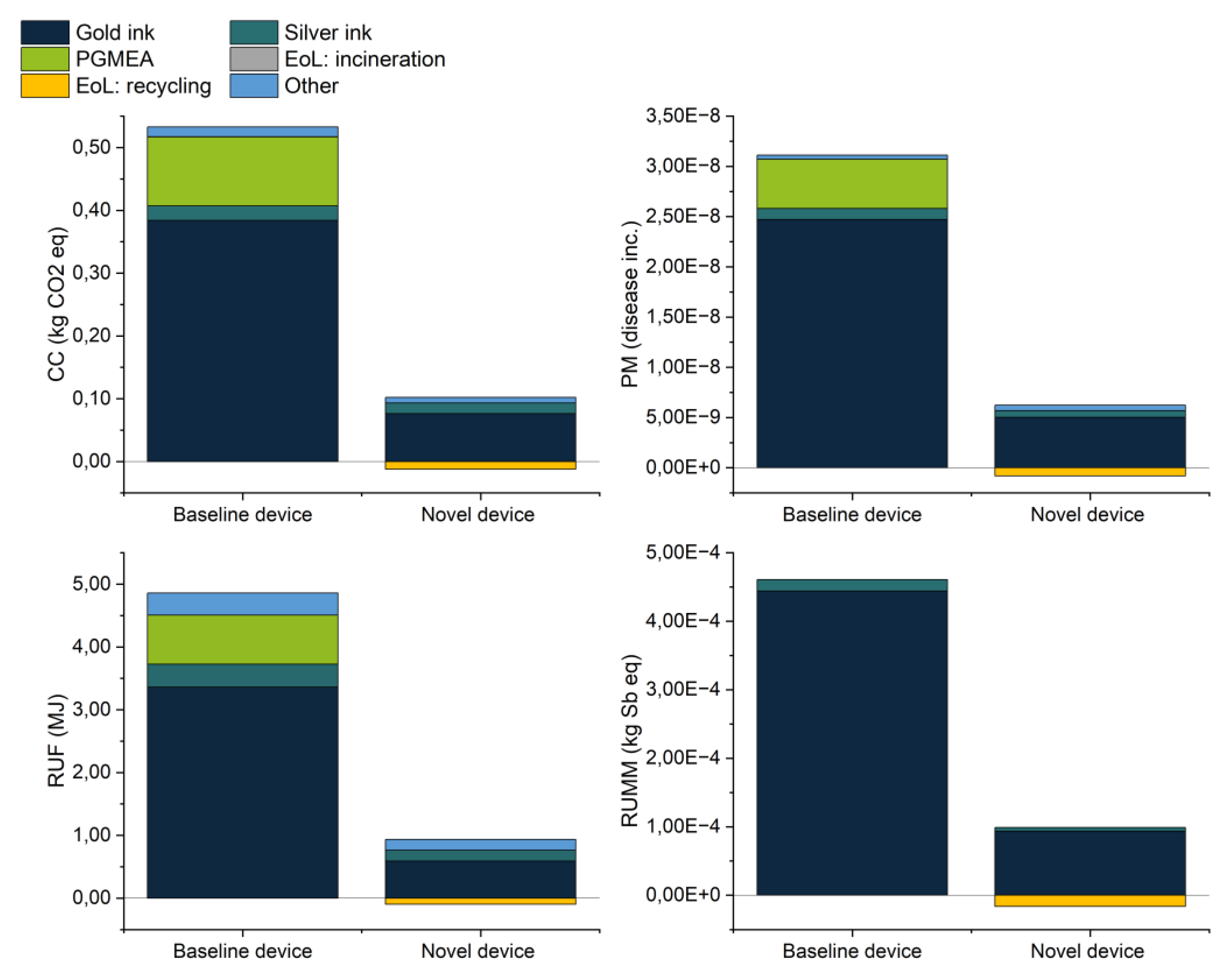

The comparative LCA study revealed that the novel biosensor had a significantly lower environmental impact than the baseline sensor for all impact categories; with the exception of water use (WU), whereby the values were similar in both cases. For all other impact categories, the reduction exceeded 80%.

Figure 18 compares the environmental impacts of both the baseline and the novel device for the most relevant impact categories according to EF category rules for IT equipment [

18], including climate change (CC), particulate matter (PM), fossil resource use (RUF), and mineral and metal resource use (RUMM). The hotspots remained the same in both devices; with the main contributor in the four categories represented by the gold ink, carrying about two-thirds of the impacts. Any remaining impacts were primarily distributed between propylene glycol methyl ether acetate (PGMEA) (only used in the baseline) and the silver ink, while the other components (including ceramic/PLA substrate, dielectric ink, electricity, and waste) had minor contributions. The drastic diminution of environmental impacts was due to the redesign of the biosensor in combination with the reduction of ink usage, ink losses during processing, and importantly, the closed-loop recycling of gold and silver.

4. Discussion

Using a DoE approach to design a silver ink enabled rapid formulation and optimisation through a well fitted model. The model was validated when the predicted properties of the ink were comparable to those that were experimentally determined. The ink achieved a resistivity within the same order of magnitude as a commercial equivalent and enabled the demonstration of closed-loop recycling for silver flakes

The gold ink achieved a significantly lower conductivity than the commercial equivalent due to the lack of sintering being employed, however, the energy savings achieved through lack of heating were significant. The usefulness of this ink will depend on the required performance of a particular biosensor, but where feasible, this ink provides an option with a significantly lower environmental impact, potentially lower production costs, and compatibility with polymer substrates. Furthermore, the electrochemical data demonstrated the high-performance nature of this ink, indicating that the surface availability of gold was more crucial than resistivity. It should be noted that while the gold content of the ink is higher for the novel gold ink, less ink was required per print run.

The solidification of the gold ink was hypothesised be due to low solubility of PCL in benzyl acetate. Additionally, PCL has a melting temperature of 60 °C, therefore mixing could introduce sufficient heat to cause PCL to melt. Both theories could be contributing, and this should be explored as part of future work. Nevertheless, this effect and the resulting performance of the ink was consistent, therefore it was practical to progress the ink to fabrication trials. Gold ink solidification enabled an unexpected benefit; liquid inks are not infinitely stable and the high-density gold particles will inevitably sediment over time. It is common practice for syringe-based inks to be stored frozen to slow the processes behind the instabilities and prevent printing inconsistencies. However, due to this solidification, the need for cold storage was removed. Many syringe dispensing systems employ syringe heating up to 60 ºC, therefore pairing this ink with a more capable syringe-based printer would enable reproducible printing without the need for pre-heating or placing the printer into a heated enclosure.

The PLA substrate provided a viable alternative to substrates such as PET that are more commonly used in the printed electronics industry. Electroactive surface area was notably lower for devices fabricated on PLA when compared with PET, potentially due to improved wettability due to PLA’s polar surface. Additionally, this polarity likely facilitates the high ink adhesion observed without requiring the addition of an adhesion promoter, while PET often requires the application of an adhesion promoter, limiting the recyclability at end-of-life. Further efforts should be carried out to develop suitable curing processes that are compatible with bio-based and temperature sensitive substrates; with methods such as NIR curing becoming more commonplace, this may provide a solution for faster drying while minimising heat exposure to the substrate.

Silver and gold recycling for single component systems was successful, with second generation devices achieving comparable results to first generation devices. This demonstrates a method that could be used by researchers to minimize their own costs and environmental impact by reusing materials from the development process. Is it is recommended that recycled metals be sufficiently characterised to ensure high purity (e.g., ICP-MS, EIS), and further investigation is required to understand the impact of potentially removing the coatings provided on the flakes by the manufacturer. By designing the inks to be selectively soluble in the solvents used in device fabrication, noble metals were successfully separated. Further optimisation is required as the recovered gold was found to be contaminated with 1.03% silver. In a gold biosensor layer, this contamination would likely impact sensing performance of a second-generation device.

These results, while very promising, demonstrate that further optimisation is required to maintain high purity gold after recycling. With further optimisation, there is a high potential for this recovery method given the processes’ simplicity and low toxicity nature. If the recovery process was further optimised, this closed-loop offering could be employed by biosensor device or ink manufacturers to lower their production costs by enabling the reuse of the expensive raw materials. Moreover, this is especially appealing due to the lack of requirements for specialist capital equipment investment or use of toxic chemicals. By recovering valuable components, manufacturers could offset the cost of setting up device return schemes with their customers and have more control over the quality of the inks used in their devices. Additionally, polymers could be recovered if this route proves to be economically and environmentally beneficial. It should be noted that no recycling was carried out following device functionalisation with glucose oxidase; this must be explored to determine whether biological species or other contaminants can be removed prior to recovering silver and gold.

Screen printing is a fast and highly scalable printing method; however, a minimum amount of ink is required per run to ensure full coverage of the screen. A significant proportion of this ink is recovered after printing, which is usually negligible when working with carbon or silver inks. However, due to the high cost of gold this waste becomes an issue. Significant material and cost savings were identified through incorporating digital printing for the gold layer. By employing screen printing for layers with greater ink coverage i.e., silver tracks and Voltera printing for the gold, the production time for the full device was not significantly increased. Gold layers took less than a minute per six devices, and while a full study should be carried out to compare production time and cost to incorporate digital printing, this highlighted the potential for digital printing to be impactful when implemented thoughtfully.

Estimation of the electroactive area using the Randles-Ševćik equation showed a significant increase of the electroactive surface areas in the second-generation sensors, especially in configurations with recycled layers of Ag and Au on PET and PLA substrates. This increase suggested a higher density of active sites available for electron transfer, which was consistent with the observed improvement in redox kinetics. The correlation between electroactive areas and amperometric sensitivity supported the hypothesis that the surface morphology and roughness induced by Voltera printing, the use of gold flakes, and the removal of organic coatings favoured an improvement in adsorption and catalytic efficiency of the electrode surface. It should be noted that the variability was higher for the novel devices; while this is to be expected for an experimental process, the variability for PET-based devices was significant. This is a notable benefit for using bio-based PLA as a replacement for PET in the fabrication of SPEs.

EIS was used as a key technique to evaluate the electrochemical interface of the functionalised sensors, providing information on charge transfer resistance (R

CT), double-layer capacitance (C

dl), and other parameters related to the kinetics of redox processes on the electrode surface. The Nyquist plots obtained showed well-defined semicircles in the high-frequency region, indicating typical behaviour for charge-transfer controlled systems. The reduction in the semicircle diameter in the second-generation sensors suggested a significant decrease in the R

CT, which was indicative of improved electron transfer efficiency between the redox probe and the electrode. This improvement was attributed to a larger electroactive area, as verified by cyclic voltammetry, and potential removal of the organic coating on gold flakes. In the Bode plots (

Figure 15), a shift towards higher frequencies in the maximum phase angle was observed, indicating a faster response of the electrochemical system. Furthermore, the slope of the impedance modulus curve in the low-frequency region was lower in the second-generation sensors, suggesting lower diffusive resistance and better accessibility of the analyte to the active surface.

Through a detailed comparison with the baseline biosensor, we showed that the novel device presented a significantly improved environmental profile. The environmental performances were enhanced by the redesign of the device to reduce ink usage, reduced ink waste by using digital printing, and the circular route that leads to closed-loop recycling of metals that are reintroduced into ink formulations. The identification of environmental hotpots allowed us to pave the way for future actions to continue progressing towards sustainability in PE devices.

Gold and silver inks were found to exhibit the highest environmental impacts due to the processes used to mine noble metals. This impact could be minimised by three approaches: i) the use of carbon-based conductive inks to replace metal-based inks when technically feasible, ii) improvements to gold and silver recycling processes to increase commercial attractiveness, and iii) redesign of devices to enable easier extraction of metals to further improve economic viability. One of the main bottlenecks still resides in the collection of PE waste to allow the recycling and reuse of noble metals; the logistics behind this waste stream are still largely unexploited by manufacturers, further reducing attractiveness of recycling as the economies of scale remain very low.

5. Conclusions

This article demonstrates how design for circularity can be highly impactful when employed in the early phases of new product development. State-of-the-art performance was achieved while significantly reducing environmental impact and cost, without compromising scalability. Digital manufacturing is not commonly found on high volume industrial print lines; however, this method is not dissimilar to adhesive dispensing, where high throughput solutions already exist. Therefore, it should be feasible to integrate syringe-based ink deposition into existing production processes. By demonstrating end-to-end innovation, the authors wish to encourage other researchers and manufacturers to embrace ecodesign principles for formulation and device design, as well as multidisciplinary collaboration, as there is a clear economic benefit in addition to the environmental gains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.S., D.I.B., M.B.G.G., G.P., L.B., I.Z.V., E.M.; methodology, A.M.S., D.I.B.; M.B.G.G., L.B., I.Z.V., E.M.; software; validation, D.I.B.; formal analysis; investigation, A.M.S., K.H., N.W., A.P., D.I.B., L. B., E.M., B.S., R.O.I., N.D.B., P.R., S.R., J.M., L.G.; resources, R.O.I, N.D.B.; data curation, A.M.S, L.B, I.Z.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.M.S, D.I.B, L.B; B.S., A.P., P.R.; writing—review and editing, G.L, I.Z.V, E.M; visualization, A.M.S., L.B., D.I.B.; supervision, A.M.S., E.M.; project administration; funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union under the GA no 101070556. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or RIA. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to protection of confidential and proprietary data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| PLA |

Polylactic acid |

| WE |

Working Electrode |

| CE |

Counter Electrode |

| RE |

Reference Electrode |

| PE |

Printed Electronics |

| EU |

European Union |

| PET |

Polyethylene terephthalate |

| Mw |

Weight average molecular weight |

| Mn |

Number average molecular weight |

| DAC |

Dual-Axis Centrifuge |

| QC |

Quality Control |

| ISO |

International Standards organisation |

| LCA |

Life Cycle Assessment |

| GOx |

Glucose Oxidase |

| SPE |

Screen Printed Electrodes |

| EF |

Environmental Footprint |

| CC |

Climate Change |

| OD |

Ozone Depletion |

| IR |

Ionising Radiation |

| POF |

Photochemical Ozone Formation |

| PM |

Particulate Matter |

| HTNc |

Non-carcinogenic human toxicity |

| HTc |

Carcinogenic human toxicity |

| A |

Acidification |

| Ef |

Eutrophication freshwater |

| Em |

Eutrophication marine |

| Et |

Eutrophication terrestrial |

| E |

Ecotoxicity freshwater |

| LU |

Land use |

| WU |

Water use |

| RUF |

Fossil resource use |

| RUMM |

Mineral and metal resource use |

| CA |

Cellulose Acetate |

| PCL |

Polycaprolactone |

| RSq |

R squared |

| DoE |

Design of Experiments |

| EIS |

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy |

| PGMEA |

Propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate |

| VOC |

Volatile Organic Compound |

| EoL |

End-of-Life |

| ICP-MS |

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry |

| RCT

|

Charge transfer resistance |

| CDL

|

Double layer capacitance |

| RH |

Relative Humidity |

References

- A. Singh et al., ‘Recent Advances in Electrochemical Biosensors: Applications, Challenges, and Future Scope’, Biosensors, vol. 11, no. 9, p. 336, Sept. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Munir, B. Ali, and S. Gul, ‘The advancements of 3D-printed electrodes in electrochemistry’, Discov. Electrochem., vol. 1, no. 1, p. 14, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- I. Maksimov, T. Asakai, and M. Ohata, ‘On the optimal use of silver–silver chloride reference electrodes’, Accreditation Qual. Assur., vol. 28, no. 2, pp. 65–68, Apr. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Zamani, V. Yang, L. Maziashvili, G. Fan, C. M. Klapperich, and A. L. Furst, ‘Surface Requirements for Optimal Biosensing with Disposable Gold Electrodes’, ACS Meas. Sci. Au, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 91–95, Apr. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Pimpilova, ‘A brief review on methods and materials for electrode modification: electroanalytical applications towards biologically relevant compounds’, Discov. Electrochem., vol. 1, no. 1, p. 12, Dec. 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Kursunoglu, ‘A Review on the Recovery of Critical Metals from Mine and Mineral Processing Tailings: Recent Advances’, J. Sustain. Metall., vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 2023–2050, 2025. [CrossRef]

- N. Tsepina, S. Kolesnikov, T. Minnikova, A. Timoshenko, and K. Kazeev, ‘Soil Contamination by Silver and Assessment of Its Ecotoxicity’, Rev. Agric. Sci., vol. 10, no. 0, pp. 186–205, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Vogel et al., ‘Defining and Achieving Next-Generation Green Electronics: A Perspective on Best Practices Through the Lens of Hybrid Printed Electronics’, IEEE Access, vol. 13, pp. 117135–117161, 2025. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Obeid et al., ‘Designs and Materials of Electrodes for Electrochemical Sensors’, ChemElectroChem, vol. 12, no. 19, p. e202500230, Oct. 2025. [CrossRef]

- ‘Why A Weakening Dollar Has Investors Eyeing Gold And Silver’. Accessed: Nov. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.forbes.com/councils/forbesfinancecouncil/2025/10/30/why-a-weakening-dollar-has-investors-eyeing-gold-and-silver/.

- ‘Silver Soars: Industrial Demand Drives Structural Shift—Mining Technology Insights’. Accessed: Nov. 03, 2025. Available: https://miningtechnologyinsights.com/2025/10/04/silver-soars-industrial-demand-drives-structural-shift/.

- ‘Silver Price History’. Accessed: Nov. 03, 2025. Available: https://silverprice.org/silver-price-history.html.

- ‘Gold Price History’. Accessed: Nov. 03, 2025. Available: https://goldprice.org/gold-price-chart.html.

- L. E. N. Gamage et al., ‘Recycling of Gold and Silver from Electronic Waste—A Review’, Mater. Circ. Econ., vol. 5, no. 1, p. 8, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- P. Phogat, S. Kumar, and M. Wan, ‘A scientometrics study of advancing sustainable metal recovery from e-waste: processes, challenges, and future directions’, RSC Sustain., vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 2434–2454, 2025. [CrossRef]

- ‘Waste statistics—electrical and electronic equipment—Statistics Explained—Eurostat’. Accessed: Nov. 06, 2025. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Waste_statistics_-_electrical_and_electronic_equipment.

- ‘Silver prices surge amid shortage’. Accessed: Nov. 03, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.marketplace.org/story/2025/10/21/silver-prices-surge-amid-shortage.

- ‘Document 32021H2279—Commission Recommendation (EU) 2021/2279 of 15 December 2021 on the use of the Environmental Footprint methods to measure and communicate the life cycle environmental performance of products and organisations’. [Online]. Available: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reco/2021/2279/oj/eng.

- I. D. Williams and O. S. Shittu, ‘Development of sustainable electronic products, business models and designs using circular economy thinking’, Detritus, no. 21, pp. 45–54, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Keal et al., ‘Design for recycle of devices to ensure efficient recovery of technology critical metals’, RSC Sustain., vol. 3, no. 6, pp. 2455–2471, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang et al., ‘Flexible printed circuit board based on graphene/polyimide composites with excellent thermal conductivity and sandwich structure’, Compos. Part Appl. Sci. Manuf., vol. 138, p. 106075, Nov. 2020. [CrossRef]

- I. A. De Araujo Andreotti et al., ‘Disposable and flexible electrochemical sensor made by recyclable material and low cost conductive ink’, J. Electroanal. Chem., vol. 840, pp. 109–116, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Terzopoulou, A. Zamboulis, N. D. Bikiaris, E. Xanthopoulou, R. O. Ioannidis, and D. N. Bikiaris, ‘A decade of innovation: Synthesis, properties and applications of PLA copolymers’, Prog. Polym. Sci., vol. 167, p. 101991, Aug. 2025. [CrossRef]

- L. Shen, E. Worrell, and M. K. Patel, ‘Comparing life cycle energy and GHG emissions of bio-based PET, recycled PET, PLA, and man-made cellulosics’, Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 625–639, Nov. 2012. [CrossRef]

- J. Mettakoonpitak et al., ‘Simple biodegradable plastic screen-printing for microfluidic paper-based analytical devices’, Sens. Actuators B Chem., vol. 331, p. 129463, Mar. 2021. [CrossRef]

- E. Palmieri, R. Cancelliere, F. Maita, L. Micheli, and L. Maiolo, ‘An ethyl cellulose novel biodegradable flexible substrate material for sustainable screen-printing’, RSC Adv., vol. 14, no. 25, pp. 18103–18108, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P.-L. Kang et al., ‘A Facile Fabrication of Biodegradable and Biocompatible Cross-Linked Gelatin as Screen Printing Substrates’, Polymers, vol. 12, no. 5, p. 1186, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- ‘Ail Arian—Reusable Silver Conductive Inks’. Accessed: Nov. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.ailarian.co.uk/.

- R. S. Shergill, P. Bhatia, L. Johnstone, and B. A. Patel, ‘Eco-Friendly Approach to Making 3D-Printed Electrochemical Sensors’, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 416–422, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Räikkönen, L. Sokka, L. Hepo--oja, S. Nordman, and T. M. Kraft, ‘Sustainable Production Insight Through LCA and LCC Analysis of Injection Overmolded Structural Electronics Manufactured through Roll--to--Roll Processes’, Glob. Chall., vol. 7, no. 11, p. 2300015, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Zikulnig, S. Carrara, and J. Kosel, ‘A life cycle assessment approach to minimize environmental impact for sustainable printed sensors’, Sci. Rep., vol. 15, no. 1, p. 10866, 2025. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Prenzel, F. Gehring, F. Fuhs, and S. Albrecht, ‘Influence of design properties of printed electronics on their environmental profile’, Matér. Tech., vol. 109, no. 5–6, p. 506, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. O. Ioannidis, Z. Terzopoulou, A. Zamboulis, N. D. Bikiaris, M. J. Noordam, and N. Nikolaidis, ‘Novel biobased, flexible blocky copolyesters based on poly(lactic acid) and poly(ethylene azelate)’, Mater. Adv., vol. 6, no. 9, pp. 2975–2989, 2025. [CrossRef]

- R. O. Ioannidis, P. A. Klonos, Z. Terzopoulou, N. Nikolaidis, A. Kyritsis, and D. D. Bikiaris, ‘Thermodynamic investigation of renewable block copolymers based on poly(lactic acid) and poly(ethylene azelate)’, Soft Matter, vol. 21, no. 33, pp. 6613–6626, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ma et al., ‘How Biaxial Flow Modulates Crystal Nucleation Behavior in Poly(lactic acid)’, Macromolecules, vol. 58, no. 14, pp. 7219–7229, July 2025. [CrossRef]

- E. Luoma et al., ‘Oriented and annealed poly(lactic acid) films and their performance in flexible printed and hybrid electronics’, J. Plast. Film Sheeting, vol. 37, no. 4, pp. 429–462, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- A.-M. Gorman, A. Clayton, T. O’Connell, and D. Johnson, ‘A recyclable screen ink with state-of-the-art performance developed using a bottom-up, safety and sustainability-driven approach’, MRS Adv., vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 311–316, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

-

ISO 14040:2006—Environmental management — Life cycle assessment — Principles and framework, ISO, July 2006. Accessed: Nov. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.iso.org/standard/37456.html.

-

ISO 14044:2006—Environmental management — Life cycle assessment — Requirements and guidelines, ISO, July 2006. Accessed: Nov. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.iso.org/standard/38498.html.

- G. Wernet, C. Bauer, B. Steubing, J. Reinhard, E. Moreno-Ruiz, and B. Weidema, ‘The ecoinvent database version 3 (part I): overview and methodology’, Int. J. Life Cycle Assess., vol. 21, no. 9, pp. 1218–1230, Sept. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Langhorst, B. Winter, D. Roskosch, and A. Bardow, ‘Stoichiometry-Based Estimation of Climate Impacts of Emerging Chemical Processes: Method Benchmarking and Recommendations’, ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng., vol. 11, no. 17, pp. 6600–6609, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. Yadav and M. Hakkarainen, ‘Degradable or not? Cellulose acetate as a model for complicated interplay between structure, environment and degradation’, Chemosphere, vol. 265, p. 128731, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, M. Dai, G. Luo, J. Fan, J. H. Clark, and S. Zhang, ‘Preparation and Application of Green Sustainable Solvent Cyrene’, Chemistry, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 2322–2346, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Ntrivala et al., ‘Polycaprolactone (PCL): the biodegradable polyester shaping the future of materials—a review on synthesis, properties, biodegradation, applications and future perspectives’, Eur. Polym. J., vol. 234, p. 114033, June 2025. [CrossRef]

- K. R. Choi, Z. W. Luo, G. B. Kim, H. Xu, and S. Y. Lee, ‘A microbial process for the production of benzyl acetate’, Nat. Chem. Eng., vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 216–228, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- ‘Merck | United Kingdom | Life Science Products & Service Solutions’. Accessed: Nov. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/GB/en.

- S. Schlisske et al., ‘Ink Formulation for Printed Organic Electronics: Investigating Effects of Aggregation on Structure and Rheology of Functional Inks Based on Conjugated Polymers in Mixed Solvents’, Adv. Mater. Technol., vol. 6, no. 2, p. 2000335, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. F. Voss, R. B. Laibowitz, and E. I. Alessandrini, ‘Percolation and fractal properties of thin gold films’, in The Mathematics and Physics of Disordered Media: Percolation, Random Walk, Modeling, and Simulation, vol. 1035, B. D. Hughes and B. W. Ninham, Eds, in Lecture Notes in Mathematics, vol. 1035. , Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1983, pp. 153–168. [CrossRef]

- P. S. Stephanou, ‘Variable entanglement density constitutive rheological model for polymeric fluids’, Rheol. Acta, vol. 63, no. 5, pp. 379–395, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- ‘LOCTITE-ECI-1010-EC-en_GL’. Accessed: Nov. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://datasheets.tdx.henkel.com/LOCTITE-ECI-1010-EC-en_GL.pdf.

- P. K. Summers, R. Wuhrer, and A. M. McDonagh, ‘Electrically conductive gold films formed by sintering of gold nanoparticles at room temperature initiated by ozone’, J. Nanoparticle Res., vol. 26, no. 5, p. 97, May 2024. [CrossRef]

- ‘Dycotec-DM-AUP-14040-Datasheet-1.04-1’. Accessed: Nov. 06, 2025. Available: https://www.dycotecmaterials.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Dycotec-DM-AUP-14040-Datasheet-1.04-1.pdf.

- ‘Print Settings | V-One | Voltera Docs’. Accessed: Nov. 06, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://docs.voltera.io/docs/v-one/learn-v-one/software-overview/print-settings.

- ‘Allen J. Bard and Larry R. Faulkner, Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications, New York: Wiley, 2001, 2nd ed.’, Russ. J. Electrochem., vol. 38, no. 12, pp. 1364–1365, Dec. 2002. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Summary of effects when data was fitted using a least squares linear regression model.

Figure 1.

Summary of effects when data was fitted using a least squares linear regression model.

Figure 2.

Actual by predicted plots for viscosity, % recovery and resistivity from left to right where RSq would ideally be above 0.7, 0.5 is deemed acceptable.

Figure 2.

Actual by predicted plots for viscosity, % recovery and resistivity from left to right where RSq would ideally be above 0.7, 0.5 is deemed acceptable.

Figure 3.

Overview of hybrid printing approach that enabled high throughput printing of silver tracks, isolation of smaller device sets via laser cutting to enable compatibility with the smaller print bed of the Voltera V-One, and gold printing using digital printing.

Figure 3.

Overview of hybrid printing approach that enabled high throughput printing of silver tracks, isolation of smaller device sets via laser cutting to enable compatibility with the smaller print bed of the Voltera V-One, and gold printing using digital printing.

Figure 4.

Overview of recovery processes from single component systems for silver (top) and gold (bottom).

Figure 4.

Overview of recovery processes from single component systems for silver (top) and gold (bottom).

Figure 5.

Overview of the process used to separate and purify silver and gold flake from mixed-metal dried samples.

Figure 5.

Overview of the process used to separate and purify silver and gold flake from mixed-metal dried samples.

Figure 6.

Flow chart of the system boundaries considered in the LCA.

Figure 6.

Flow chart of the system boundaries considered in the LCA.

Figure 7.

JMP17 profile predictor considering effects of inputs on outputs.

Figure 7.

JMP17 profile predictor considering effects of inputs on outputs.

Figure 8.

(left) Gold agglomeration in ink containing 85 wt% gold flake, (right) ball bearings included in DAC mixing to increase shearing force and resultant mixing intensity.

Figure 8.

(left) Gold agglomeration in ink containing 85 wt% gold flake, (right) ball bearings included in DAC mixing to increase shearing force and resultant mixing intensity.

Figure 9.

Resistivity with respect to gold loading for inks containing 1:2 PCL10K and PCL80K.

Figure 9.

Resistivity with respect to gold loading for inks containing 1:2 PCL10K and PCL80K.

Figure 10.

Images of the silver and gold extraction processes. From left to right: silver flake sediment, dried silver powder, gold flake sediment, and dried gold powder.

Figure 10.

Images of the silver and gold extraction processes. From left to right: silver flake sediment, dried silver powder, gold flake sediment, and dried gold powder.

Figure 11.

Viscosity change with respect to time for 1:1 PCL10K: PCL80K.The green line shows the change in viscosity at 20 °C at a constant frequency, the red line shows immediate heating of the same sample at 40 °C and analysis at consistent frequency.

Figure 11.

Viscosity change with respect to time for 1:1 PCL10K: PCL80K.The green line shows the change in viscosity at 20 °C at a constant frequency, the red line shows immediate heating of the same sample at 40 °C and analysis at consistent frequency.

Figure 12.

Image of gold printing on the Voltera V-One (left) and image of the final printed sensors.

Figure 12.

Image of gold printing on the Voltera V-One (left) and image of the final printed sensors.

Figure 13.

Material used or recovered at various stages of printing; the final column shows the actual amount of ink used by both print methods when factoring in ink waste and recollection.

Figure 13.

Material used or recovered at various stages of printing; the final column shows the actual amount of ink used by both print methods when factoring in ink waste and recollection.

Figure 14.

Cyclic voltammograms of 1 mM K3 [Fe(CN)6] 100 mM KCl solution scanning potential from 450 mV to -300 mV at potential at different scan rates (5, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 250, 500 mV/s (right) and calibration curves obtained from the current peak intensity (right) for baseline and novel devices.

Figure 14.

Cyclic voltammograms of 1 mM K3 [Fe(CN)6] 100 mM KCl solution scanning potential from 450 mV to -300 mV at potential at different scan rates (5, 10, 25, 50, 75, 100, 250, 500 mV/s (right) and calibration curves obtained from the current peak intensity (right) for baseline and novel devices.

Figure 15.

Nyquist diagram (blue line) and Bode diagram were magnitude of impedance |Z| is shown in red line and the phase angle is shown in green line, obtained with EIS experiments recorded in 1 mM of equimolar K4 [Fe(CN)6]/K3 [Fe(CN)6] 100 mM KCl for baseline and novel devices.

Figure 15.

Nyquist diagram (blue line) and Bode diagram were magnitude of impedance |Z| is shown in red line and the phase angle is shown in green line, obtained with EIS experiments recorded in 1 mM of equimolar K4 [Fe(CN)6]/K3 [Fe(CN)6] 100 mM KCl for baseline and novel devices.

Figure 16.

Amperometric responses obtain applying +0.3 V for 90 seconds in glucose solution with concentrations from 1 to 100 mM in 100 mM TRIS pH 7.2 buffer solution, (inset, calibration plots) for different electrodes: a) baseline device, b) PET virgin Ag virgin Au, c) PET recycled Ag recycled Au, d) PLA virgin Ag virgin Au, and e) PLA recycled Ag recycled Au (novel device).

Figure 16.

Amperometric responses obtain applying +0.3 V for 90 seconds in glucose solution with concentrations from 1 to 100 mM in 100 mM TRIS pH 7.2 buffer solution, (inset, calibration plots) for different electrodes: a) baseline device, b) PET virgin Ag virgin Au, c) PET recycled Ag recycled Au, d) PLA virgin Ag virgin Au, and e) PLA recycled Ag recycled Au (novel device).

Figure 17.

Relative environmental impacts of the novel device.

Figure 17.

Relative environmental impacts of the novel device.

Figure 18.

Breakdown of environmental impacts between the baseline biosensor and novel device.

Figure 18.

Breakdown of environmental impacts between the baseline biosensor and novel device.

Table 1.

Summary of inputs (with ranges) and outputs for this experimental design.

Table 1.

Summary of inputs (with ranges) and outputs for this experimental design.

| Inputs |

Outputs |

| Silver loading, 60–80 wt% |

Low-shear viscosity (1.5 s−1) |

| Cellulose acetate 30 kDa (CA30K), 0–6 wt% |

Viscosity recovery (%) |

| Cellulose acetate 50 kDa (CA50K), 0–1.33 wt% |

Resistivity (Ω·cm) |

Table 3.

Comparison of silver and gold inks using virgin and recycled silver and gold.

Table 3.

Comparison of silver and gold inks using virgin and recycled silver and gold.

| Test |

10 g scale,

virgin silver |

10 g scale,

recycled silver |

2 g scale, virgin gold |

2 g scale, recycled gold |

| Ink viscosity @ 1.5 s−1 (Pa.s) |

41.5 |

45.2 |

- |

- |

| Viscosity recovery (%) |

87.6 |

10.7 |

- |

- |

| Resistivity (Ω·cm) |

5.30 × 10−5

|

2.72 × 10−5

|

4.92 × 10−2

|

5.64 × 10−3

|

Table 4.

Comparison of novel silver screen ink to commercial silver screen ink Loctite ECI1010 [

50].

Table 4.

Comparison of novel silver screen ink to commercial silver screen ink Loctite ECI1010 [

50].

| Property |

Loctite ECI 1010 silver screen ink |

Virgin silver screen ink |

Recycled silver screen ink |

| Resistivity ( Ω·cm) |

1.43 × 10−5

|

5.30 × 10−5

|

2.72 × 10−5

|

| Silver content (wt%) |

62 |

62 |

62 |

| Drying temperature (°C) |

120 |

120 |

120 |

Table 5.

Comparison of novel gold Voltera ink to commercial gold screen ink DM-AUP-14040S [

52].

Table 5.

Comparison of novel gold Voltera ink to commercial gold screen ink DM-AUP-14040S [

52].

| Property |

DM-AUP-14040S gold screen ink |

Virgin gold Voltera ink |

Recycled gold Voltera ink |

| Resistivity (Ω·cm ) |

5.6 × 10−6

|

4.92 × 10−2

|

5.64 × 10−3

|

| Gold content (wt%) |

81–83 |

90.5 |

90.5 |

| Drying temperature (°C) |

150 |

Ambient |

Ambient |

| Sintering temperature (°C) |

850 |

Not required |

Not required |

Table 6.

Geometrical areas and average values of the electroactive areas of electrodes for 30 devices of each iteration.

Table 6.

Geometrical areas and average values of the electroactive areas of electrodes for 30 devices of each iteration.

| Electrode |

Geometrical area (mm2) |

Electroactive area (mm2) |

Variability, n=3 (%) |

| Base0—Baseline device |

1 |

0.45 |

6.08 |

| Sensor1—PET virgin Ag virgin Au |

1 |

2.51 |

53.36 |

| Sensor2—PET recycled Ag recycled Au |

1 |

4.55 |

91.68 |

| Sensor3—PLA virgin Ag virgin Au |

1 |

1.68 |

15.99 |

| Sensor4—PLA recycled gen Ag recycled Au (novel device) |

1 |