1. Introduction

Since 2000, research on aquatic food value chains has expanded significantly. However, fisheries and aquaculture are often analysed separately, reinforcing the misconception that they are unrelated [

1,

2] argued against the common tendency to treat the aquatic food value chain as a distinct field in fisheries and aquaculture, instead as integrated, given the obvious and interlinked nature. Recognizing their interconnectedness is essential for effective policy and sustainable sector development. This study forms part of the Asia-Africa BlueTech Superhighway (AABS) initiative, where IMTA is featured as the second implementation package. It was designed to offer a detailed assessment of Nigeria’s aquatic food sector and provide valuable insights into the industry’s current state. An integrated approach of aquatic food from fisheries and aquaculture was taken, given that in Nigeria, capture fisheries remain dominant, accounting for 75% of fish production [

3], though aquaculture is rapidly developing. Cage aquaculture is still largely traditional, with pen culture more common.

The IMTA project is a bold initiative aimed at transforming the scope and practices of aquaculture in Nigeria. IMTA’s success holds strategic importance for Nigeria, offering gains in food security, diversification beyond catfish monoculture, enhanced farmer livelihoods, increased investment potential, and expanded export opportunities [

4]. [

5] noted that economically, IMTA systems are more effective than mono and polyculture farming, as they improve animal growth and water quality, hence influencing all aspects of aquaculture [

5]. [

6] mentioned that challenges of IMTA in Hawaii and beyond include low financial returns, high startup costs, low profitability, and limitations to commercial expansion [

6]. According to [

7], integrating Atlantic salmon into IMTA was limited by the huge extractive species scale-up to achieve effective environmental mitigation, high capital and maintenance costs that are compounded by insufficient governmental support and a lack of commitment to innovation, and low policy execution. [

8], mentioned that despite recent growth in fish production, demand for fish far exceeds domestic supply, and imported frozen fish account for about 45% of the fish consumed in Nigeria, thus justifying the search for options for increasing production sustainably.

IMTA practice has been conducted for a thousand years despite gaining recognition in recent decades [

9]. Literature on IMTA can be situated within the domain of upstream analyses within the aquatic food value chain, given that it remains innovative in many countries as an aquatic system globally. A production model was examined in Peru [

10]. [

11] argued that it is reformative as a balanced system for sustainable aquaculture, and as reported by [

12], it is an environmentally friendly production system. [

9] reported the impact of IMTA production across different habitats using life cycle assessment. [

13] proposed downstream-related marketing issues, such as promoting the eco-certification of IMTA products. Despite their observations, studies on the aquatic food value chain market mix are rare. There appears to be a greater emphasis on consumer perceptions of sustainable products [

14], willingness to pay (WTP) [15, 16], and market access [

17]. Studies are based on consumers’ reactions and attitudes to the transformation in the aquatic food chain through innovation in the production technology, as may be the case with IMTA in Nigeria. The pivot of these studies is healthiness and sustainability; [

18] added the dimension of taste and nutrition.

This report highlights that, while the aquatic food value chain may appear fragmented at the upstream level, it converges at the midstream stage, where markets in Nigeria are inherently interconnected rather than distinct. In open markets, niche segments where consumers specifically seek either wild-caught or farmed fish are relatively uncommon. Researchers have also reported on a single value chain node in Bangladesh [

19] and Nigeria [

20], which focused on gender. In Nigeria, literature on fisheries aquatic food chains includes [

21,

22,

23], which dealt with fish processing methods, notably smoking and drying. For aquaculture aquatic food value chains, studies has [

24] worked on profitability, while [

25] was on the economic impacts of diseases. [

1,

25] reported on the transformation of the aquatic food system in Nigeria.

The broad objective of this study was to examine the structure, practices, and challenges of aquatic food production and marketing in selected coastal states of Nigeria that could inform strategies for IMTA. Specific objectives were document the types and volumes of aquatic food produced (including finfish, shellfish, and seaweeds) and assess the dominance of various species in coastal production systems; identify the prevailing production practices and assess the extent and limitations of post-harvest preservation methods such as smoking, sun-drying, and cold storage; analyse the marketing mix strategies employed by aquatic food traders, particularly distribution channels and promotional methods (e.g., word-of-mouth); evaluate consumer preferences, motivations, and openness toward new aquatic food products such as seaweeds; examine the challenges facing producers and traders in marketing aquatic foods, especially related to infrastructure, power supply, and storage technologies and assess the extent of local consumption versus export orientation in aquatic food sales, and the factors influencing market targeting and product distributions.

2. Materials and Methods

This report centres on three previously selected states: Lagos, Ogun, and Ondo States. These states were identified at the stakeholder meeting and the donor’s travel advisory guidance as suitable locations from the nine coastal states of Nigeria for the implementation of the IMTA project. Ethical approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee of the Lagos State University with approval No LASU/24/REC/096.

2.1. Study Areas

2.1.1. Lagos State

Lagos State, located in southwestern Nigeria, is a coastal and maritime hub with a significant portion of its land area covered by water bodies, including lagoons, rivers, and swamps. This geographical advantage makes it a prime location for fishing and aquaculture activities. The state yields around 174,553 tonnes of fish annually, with artisanal fisheries accounting for approximately 80% of total production. Aquaculture contributes 35,524 tonnes per year [

27]. Open-water fish farming systems, such as innovative fish cage culture, are being utilized to enhance production and generate employment opportunities for women and youth in artisanal fishing communities [

27].

Fish remains in high demand due to its affordability and nutritional benefits, positioning fish marketing as a crucial pillar of Lagos State’s economy. The fresh fish market operates under a monopolistic competition structure, where individual farmers independently determine pricing [

28]. According to [

28], the market is challenged by limited access to credit and operational inefficiencies; however, efforts are being made to improve market performance through capacity building and policy support. Fisheries and aquaculture play a crucial role in ensuring food security and driving socioeconomic development in the state. Efforts focused on production, promoting economic growth, and advancing sustainability within the sector are ongoing [

27,

28].

2.1.2. Ogun State

Ogun State is endowed with diverse water resources, rivers, streams, and wetlands that provide a supportive environment for fishing and aquaculture activities. Artisanal fishing is the dominant practice, with local communities relying on traditional methods to harvest fish, and a growing aquaculture sector, contributing to food security and income generation [

29]. Socioeconomic studies of the state highlighted in [

29] stated that fish farming in the state is profitable, with farmers achieving a return on investment of approximately 55%, despite being confronted with challenges such as the high cost of inputs like feed and fingerlings, limited access to credit, which affect the profitability of fish farming. Fish marketing in the state is largely driven by small-scale operations, with women playing a leading role in the trade but it faces challenges such as limited storage infrastructure and unstable pricing. Nevertheless, the sector remains a vital contributor to the state’s economy, and efforts are being made to improve market efficiency and support fish farmers through government initiatives and capacity-building programs [

30]. Overall, the fisheries and aquaculture sector in Ogun State contributes to food security, poverty alleviation, and economic development [

31].

2.1.3. Ondo State

The state has a diverse population, and fishing communities play a vital role in the local economy. Fish marketing in areas such as Igbokoda is both efficient and profitable, with women dominating the trade and earning an average monthly income of ₦60,000. Despite facing challenges like insufficient storage, fluctuating prices, and restricted access to credit, the sector continues to thrive [

32]. The study noted that efforts are being made to address these issues through agricultural policies and infrastructure improvements.

Fish farming in the state faces factors like the cost of land and the number of ponds owned, which impact profitability. Despite the challenges, the sector remains a significant source of revenue and employment for rural communities [

33]. [

34] reported that the fishing industry in Ondo State contributes to poverty alleviation, protein supply, and economic development, with artisanal fisheries being a key component.

2.2. Questionnaire Design and Data Collection

The questionnaire was developed and subsequently piloted across the three states. The instruments were later reviewed and validated by the team at WorldFish Ibadan and the Federal University of Technology, Akure. The instrument was uploaded into the Kobo Toolbox software, and four enumerators were recruited and received specialised training in data collection using tablet computers. To ensure data quality, enumerators were selected based on their professional qualifications, holding at least a BA/BSc, and prior hands-on experience in data collection, particularly with WorldFish projects. Each enumerator was assigned ten surveys per day across six days in each state.

2.3. Sampling Techniques

The research employed a multi-stage sampling approach across Lagos, Ogun, and Ondo.

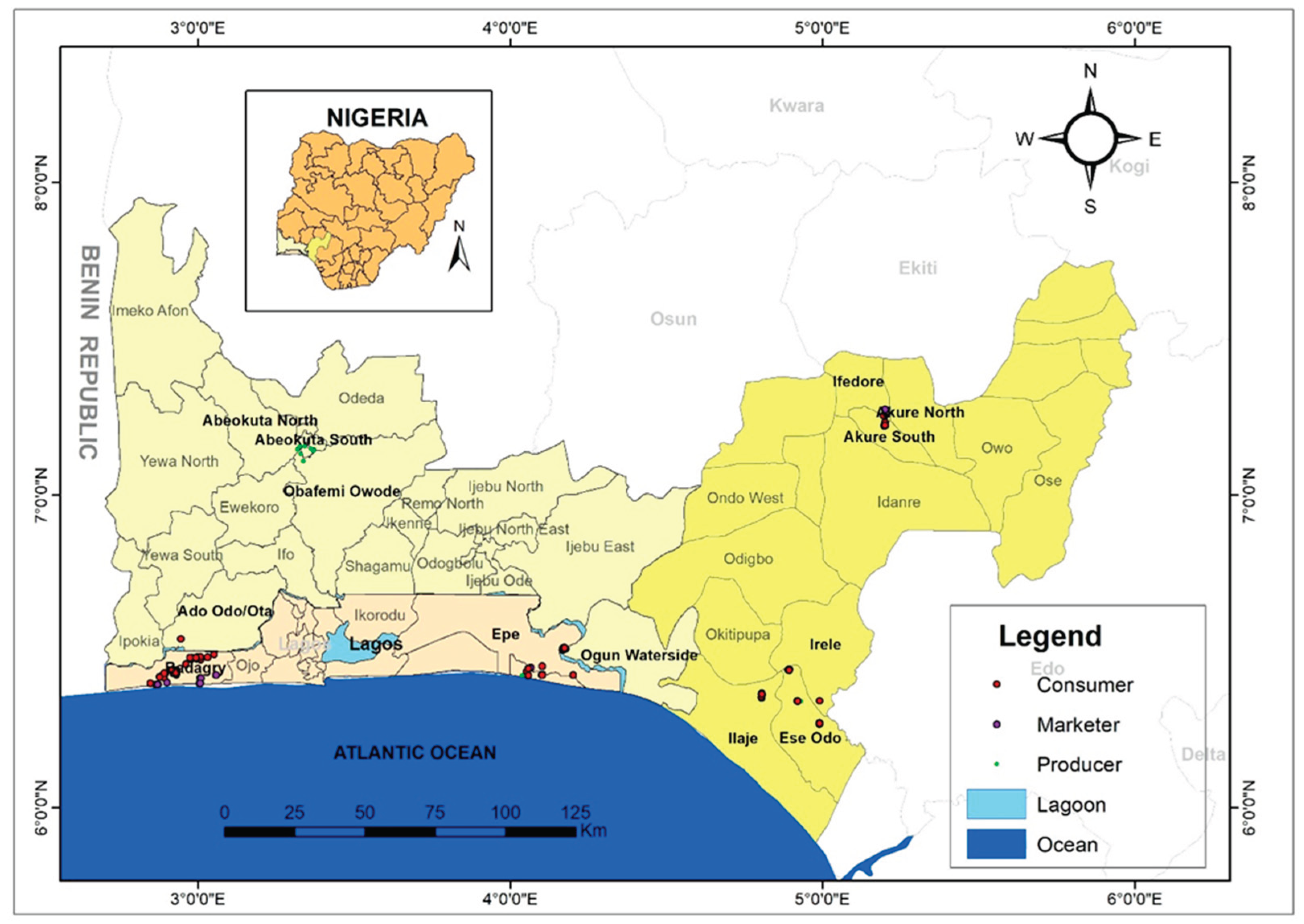

In each state, respondents were selected from key nodes along the fish value chain, including producers (fishers and fish farmers), traders and sellers (wholesalers and retailers), as well as consumers of both fresh and dried fish. The team interviewed around 239 respondents in each of the three states. Respondents in each state included women and men of different ages from sub-ethnic and religious communities. The spread of respondents across the LGAS and LCDAs is shown in

Figure 1 for each value chain node across the states. The choice of respondents interviewed was based on their willingness to participate in the survey. The justification for sampling more LGAs in Ogun state, more than Lagos state, is that Lagos has five agricultural zones commonly known as IBILE (Ikeja, Badagry, Ikorodu, Lagos Island, and Epe). Ikeja and Lagos Island were omitted because they are not water-based coastal areas. Ikorodu was not included due to logistical issues, while Epe shared a border with Lekki, which is under Ikorodu; thus, the sampling might result in duplicate responses. Water-based aquaculture is commonly practised in Ikorodu, Epe and Badagry divisions; thus, we sample two of the divisions.

Table 1 summarises the number of respondents interviewed in each state by value chain nodes (producers 115, traders 236, and consumers 362). Data were analysed using frequencies and percentages.

3. Results

3.1. Interpretation and Visualisation

Figure 1 presents a well-labelled and visually engaging spatial distribution map, illustrating the locations of value chain actors, oceanic features, and administrative boundaries. The map was developed using digital cartography techniques within the ArcGIS environment. The data presented in this study on the coordinates of the fish farmers are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy, legal, and ethical reasons.

3.2. Aquatic Foods by Coastal and Marine

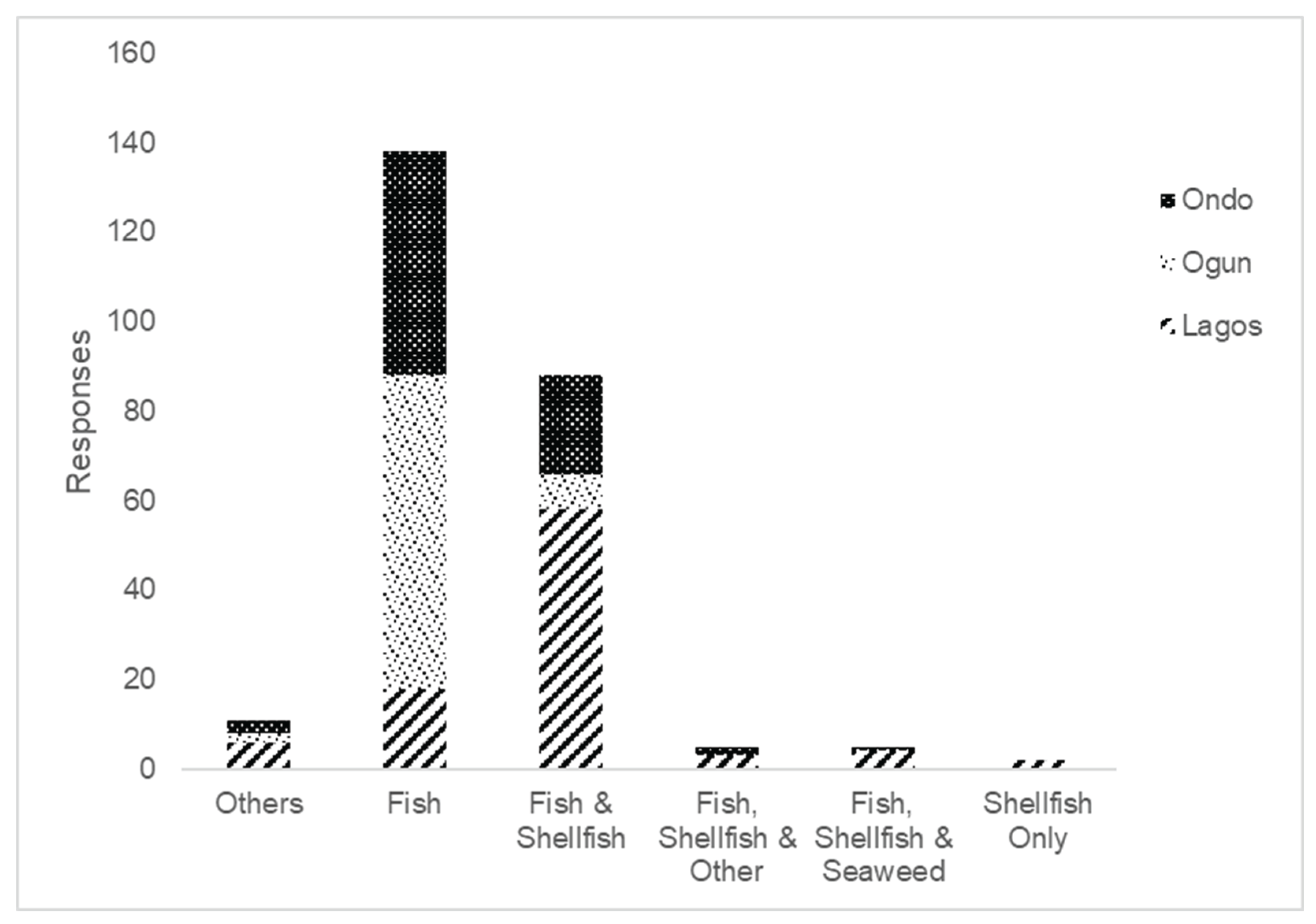

The varieties of aquatic foods produced and sold across the coastal states are shown in

Figure 2. Fish is the most commonly sold aquatic food across all states, with 74 of the respondent farmers from Ogun State stating that they mainly farm/harvest fish. Respondent farmers (57) operating in the Lagos States averred that the aquatic foods product they farm/harvested consisted of fish and shellfish with only 23 and 5 respondent farmers from Ondo and Ogun States. (only 5) trailing behind, indicating that shellfish is less popular in Ogun; meanwhile, alternative aquatic foods such as seaweed and shellfish alone are rarely sold, suggesting that the market is heavily dominated by fish, with minimal diversification into other aquatic food categories.

3.3. Information on Marketing Channels of Aquatic Food Across the Coastal States

The marketing channels across the three coastal states showed that data distribution nodes are location dependent. Zero channels are highest with consumers having access to the aquatic foods directly, especially in Ondo State, where 64.94% of respondents sell directly to consumers. In Lagos State, the zero market channels are not as common; one or two channels are popular means of distributing aquatic foods. Daily sales of aquatic foods are the most common sales method across the three states in terms of frequency of sales. In Lagos State, 83.54%, 75.00% in Ogun, and 63.64% in Ondo States responded that they daily have aquatic foods to sell. Weekly sales are common in Ogun State than in the three other states, with about 23.80% of respondents claiming they sell weekly. Traders playing more than one role, combining roles as retailers and wholesalers, is more common in Lagos State (50.64% of respondents). Whereas distributors in Ondo State practice fewer role switching, with 53.25% playing only the retailers’ roles.

Figure 1.

Map Indicating Sampling Locations across Producers, Traders, and Consumers.

Figure 1.

Map Indicating Sampling Locations across Producers, Traders, and Consumers.

3.4. Aquatic Food Market Types in the Three Coastal States

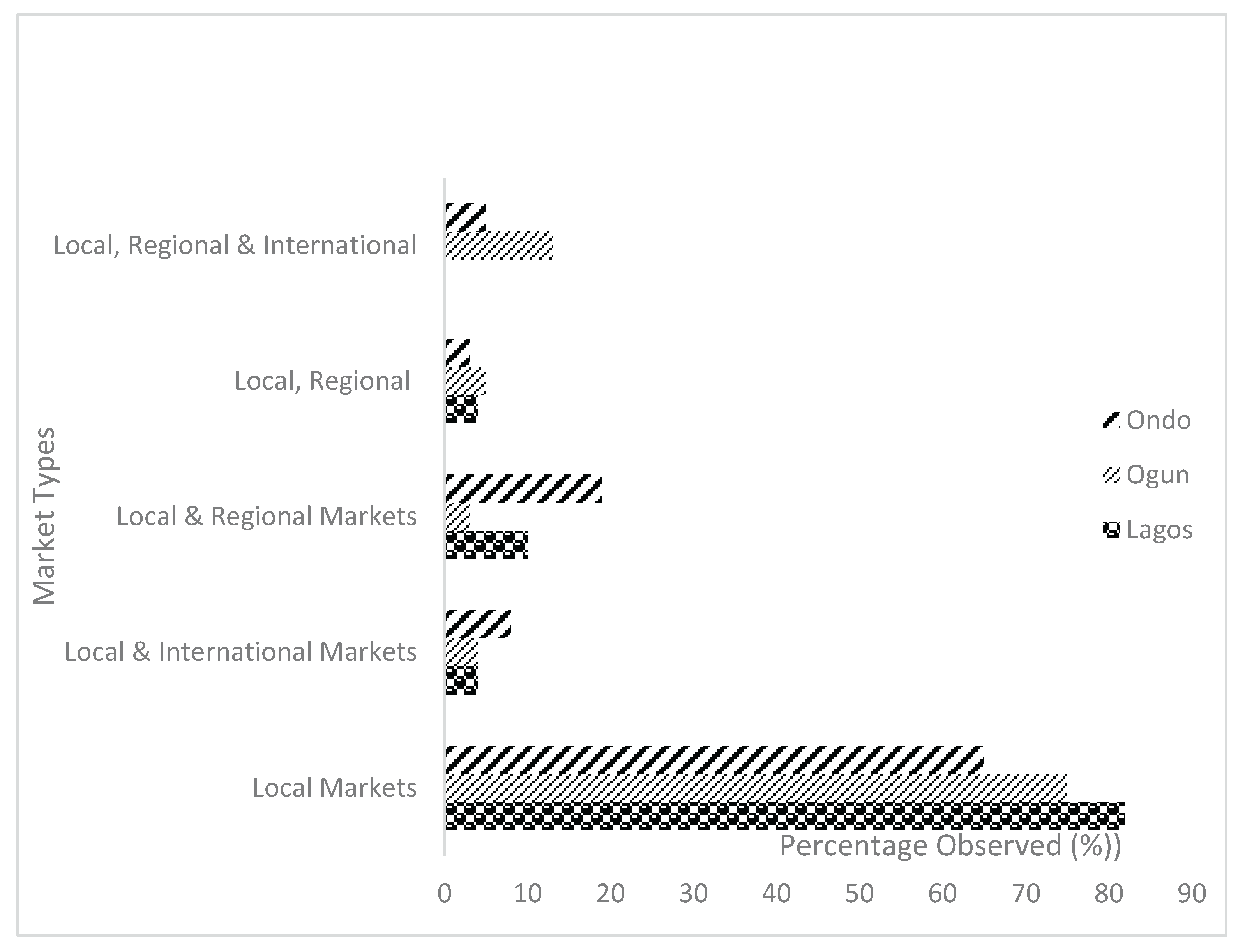

Local markets are the predominant sales channel, as shown in

Figure 3, with 81.3% in Lagos, 72.5% in Ogun, and 56.3% in Ondo relying solely on them. Export-related channels are minimal across the board, noted only in Lagos and Ogun at 1.3%, while Ondo shows no export activity. Ondo, however, exhibits a higher inclination toward combining local with regional markets (21.3%), compared to 12.5% in Lagos and 10.0% in Ogun. A mixed channel encompassing local, regional, and export markets is also more notable in Ogun (12.5%) than in Ondo (3.8%), and regional-only sales remain low in all three states.

3.5. Estimated Quantity of Aquatic Food Sales

Out of 236 respondents, the majority, 107 individuals, reported estimated monthly aquatic food sales ranging from 1 to 5 tonnes, indicating this volume as the most dominant in the market (see

Table 2). Additionally, 38 respondents indicated monthly sales between 11 and 15 tonnes, while a smaller group of 5 respondents reported sales volumes in the range of 26 to 30 tonnes per month.

3.6. Promotion Methods by Traders

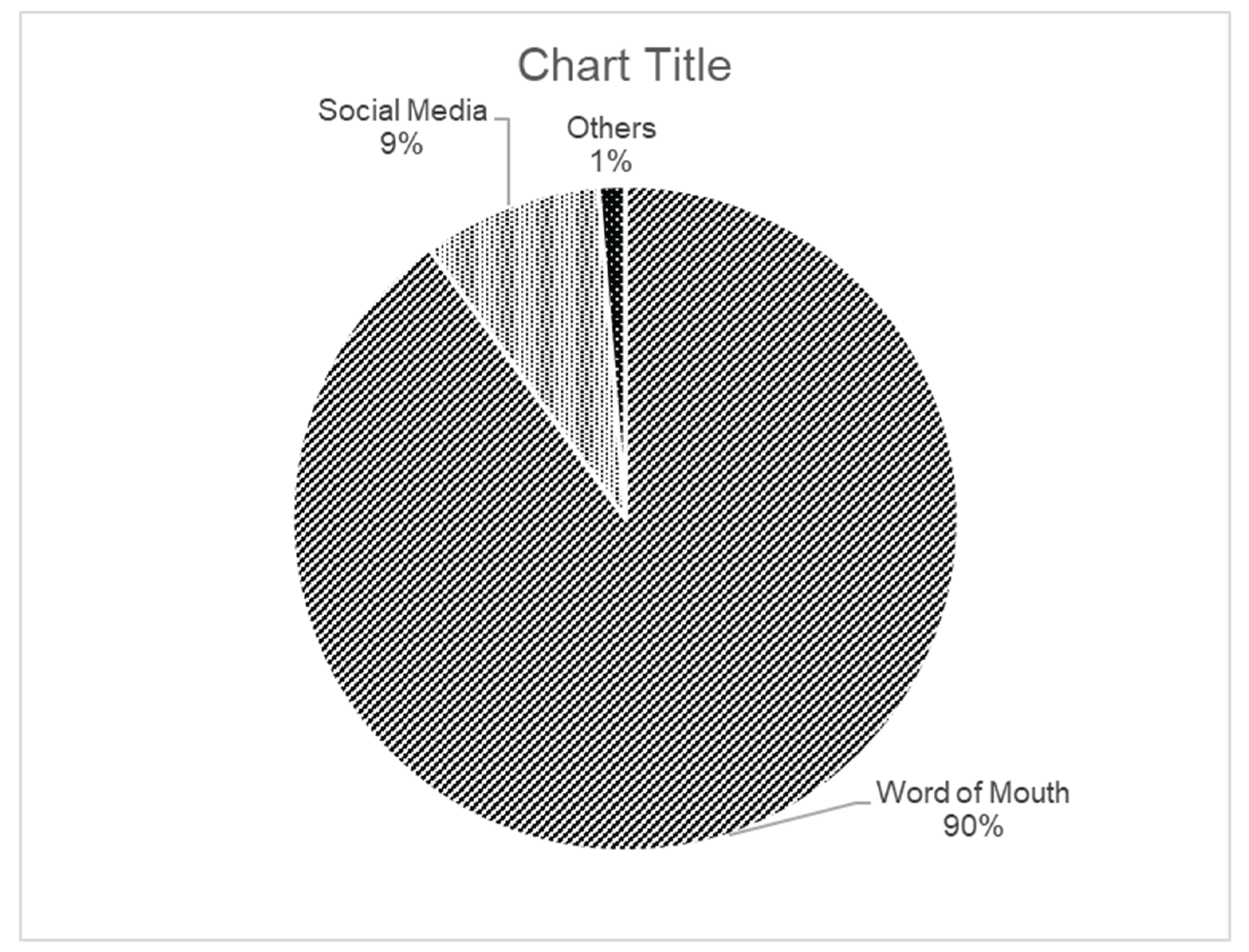

Word of Mouth (WOM) is the most dominant at 90% (pooled responses, n= 236) as seen in

Figure 4. Only 8.8% of the respondents were in favor of using social media (WhatsApp, Facebook, etc.), suggesting that businesses in this context rely less on digital platforms. The other category, accounting for only 1.3% (1 response), indicated the use of alternative marketing strategies, such as encore, to promote the product through advocacy and referrals, typically for distant regional and export markets. Community meetings also provided opportunities to promote sales of their products.

3.7. Postharvest Practices Across the Three Coastal States

Aquatic food marketers/traders employed different postharvest methods and value-addition strategies to prevent loss and wastage of their products, as shown in

Table 4. The respondents believed that the technique employed was sufficient to achieve their objectives of preserving the goods. In Lagos State, 90% (n=79) believe that they do have access to adequate storage. In Ogun State, 50% (n=80) answered Yes to the question of whether they have satisfactory storage methods. However, in Ondo, 60%opposed the view that the storage practice was adequate.

Responses to the strategies were different across the three states. In Lagos State, 90% of respondents adopted open-air storage, and 10% use the smoking method. In Ogun State, the two frequently used strategies are the open-air and cold room methods, according to 30% and 36% of respondents, while 9.1% of the respondents separately use icebox and smoking methods. In Ondo State, 80% of respondents use open-air storage. In Ondo State, 90% of respondents mentioned power outage.

Value addition and postharvest practices being practised include adding salt and pepper, sun-drying, cleaning with red oil, sun-drying with salt and pepper, unique packaging, smoking, and processing. Fish smoking and processing techniques were the most common methods in Lagos State; individually, the responses were 30% in both cases. Fish smoking, likewise, was common among traders in Ogun State, with 38% adopting it among the respondents. Sun-drying was the most common method of preserving the aquatic foods in Ondo State, as 30% responded to using the method.

Table 2.

Estimated Quantity of Aquatic Products Traded across Lagos, Ogun and Ondo States.

Table 2.

Estimated Quantity of Aquatic Products Traded across Lagos, Ogun and Ondo States.

| Quantity Category |

Lagos (N=32) |

Lagos (%) |

Ogun (N=78) |

Ogun (%) |

Ondo (N=35) |

Ondo (%) |

| 0.001–1 tonne |

17 |

53.13 |

16 |

20.51 |

29 |

82.86 |

| 1–10 tonnes |

15 |

46.87 |

56 |

71.80 |

6 |

17.14 |

| 11–20 tonnes |

0 |

0.00 |

5 |

6.41 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 21–30 tonnes |

0 |

0.00 |

1 |

1.28 |

0 |

0.00 |

| Total |

32 |

100 |

78 |

100 |

35 |

100 |

Figure 2.

Types of aquatic foods sold by coastal and marine food producers across the states.

Figure 2.

Types of aquatic foods sold by coastal and marine food producers across the states.

Figure 3.

Aquatic Food Market Types in the three coastal States.

Figure 3.

Aquatic Food Market Types in the three coastal States.

3.8. Aquatic Food Consumption Across the Three Coastal States

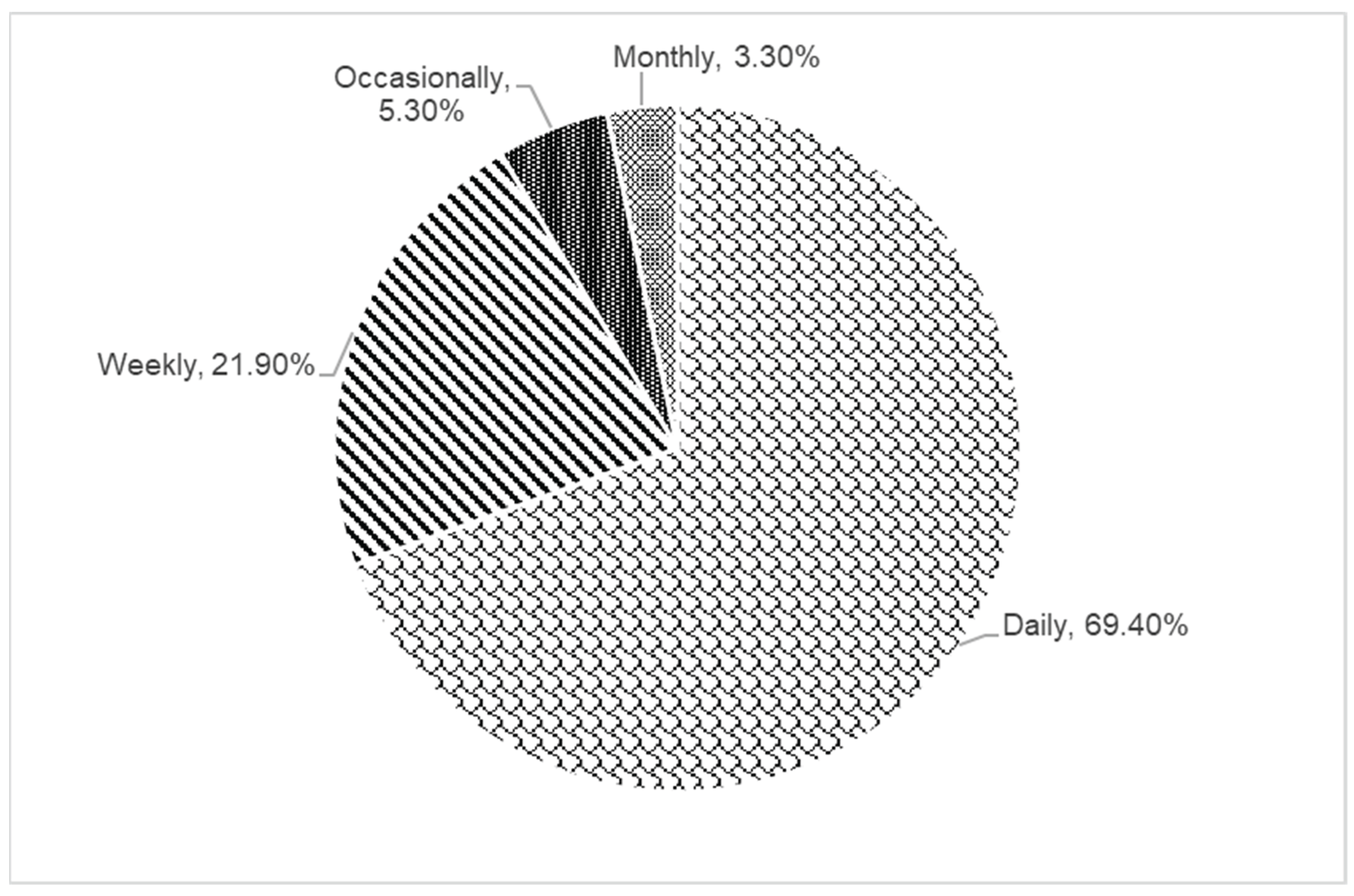

The pooled responses from consumers across the three states showed daily consumption was highest (

Figure 5), with 69.4% (n= 362) stating that they consume aquatic foods daily. The number of consumers mentioning that they consumed aquatic foods every week was estimated at 80 persons (21.9%). The respondents expressing that they consumed aquatic foods occasionally and monthly were low, representing 5.3% and 2.3%.

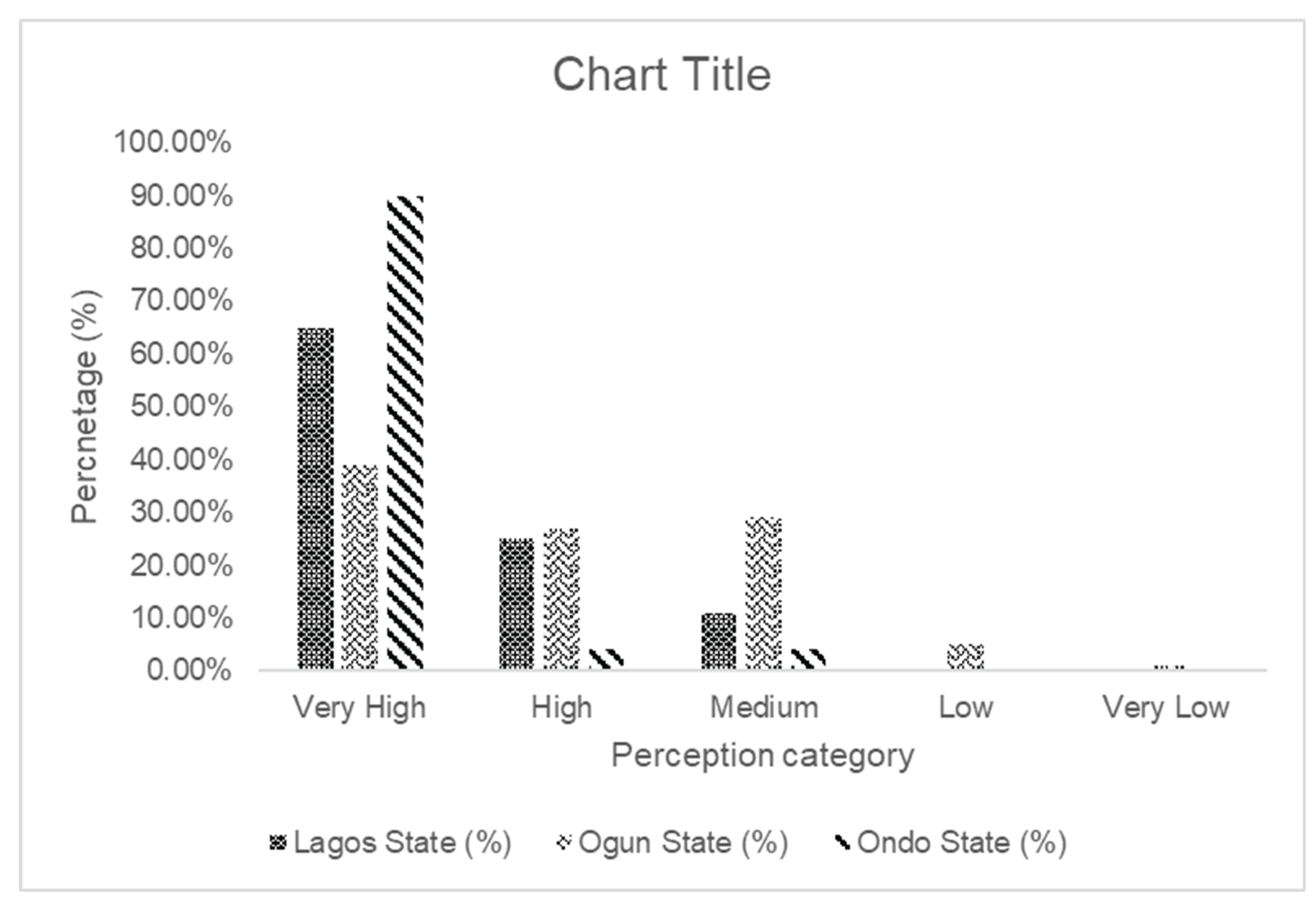

3.9. Consumers’ Perception of the Quality of Local Aquatic Food

Consumers in Lagos, Ogun, and Ondo hold positive views of locally produced aquatic foods, with very high-quality ratings dominating approximately 90% in Ondo, 65% in Lagos, and 40% in Ogun. High quality ratings are moderately present in Lagos and Ogun (around 25%), but minimal in Ondo, where Very High ratings are strongly preferred. Ogun shows the most variety, with 25% of consumers perceiving quality as Medium, while Lagos accounts for about 10% in this category, and Ondo has almost none. Negative perceptions (Low and Very Low) are rare, with Ogun showing a small share, and Lagos and Ondo reporting almost no concerns.

3.10. Consumers’ Perception of Imported Aquatic Foods, New Products (Seaweeds), and Willingness to Pay for Sustainable Aquatic Foods

The highlight of consumers’ perception of the quality of imported aquatic food in Lagos, Ogun, and Ondo states is shown in Table 6. Ondo shows the highest High-Quality ratings (43.3%), while Lagos expresses the most scepticism, with 35.8% rating the quality as Low. Ogun demonstrates the most balanced views, with 48.3% rating the quality as Medium, reflecting mixed opinions. Despite these differences, over 89% of consumers across all states are willing to try new aquatic food products, though Ondo has the highest percentage (10.4%) unwilling to do so, indicating a possible preference for traditional options. Support for sustainable aquatic foods is strong, with Ondo leading (85.0%), followed by Lagos (82.5%) and Ogun (79.2%). However, a small share, especially in Ogun (20.8%), remains unwilling to pay extra for a product’s sustainability.

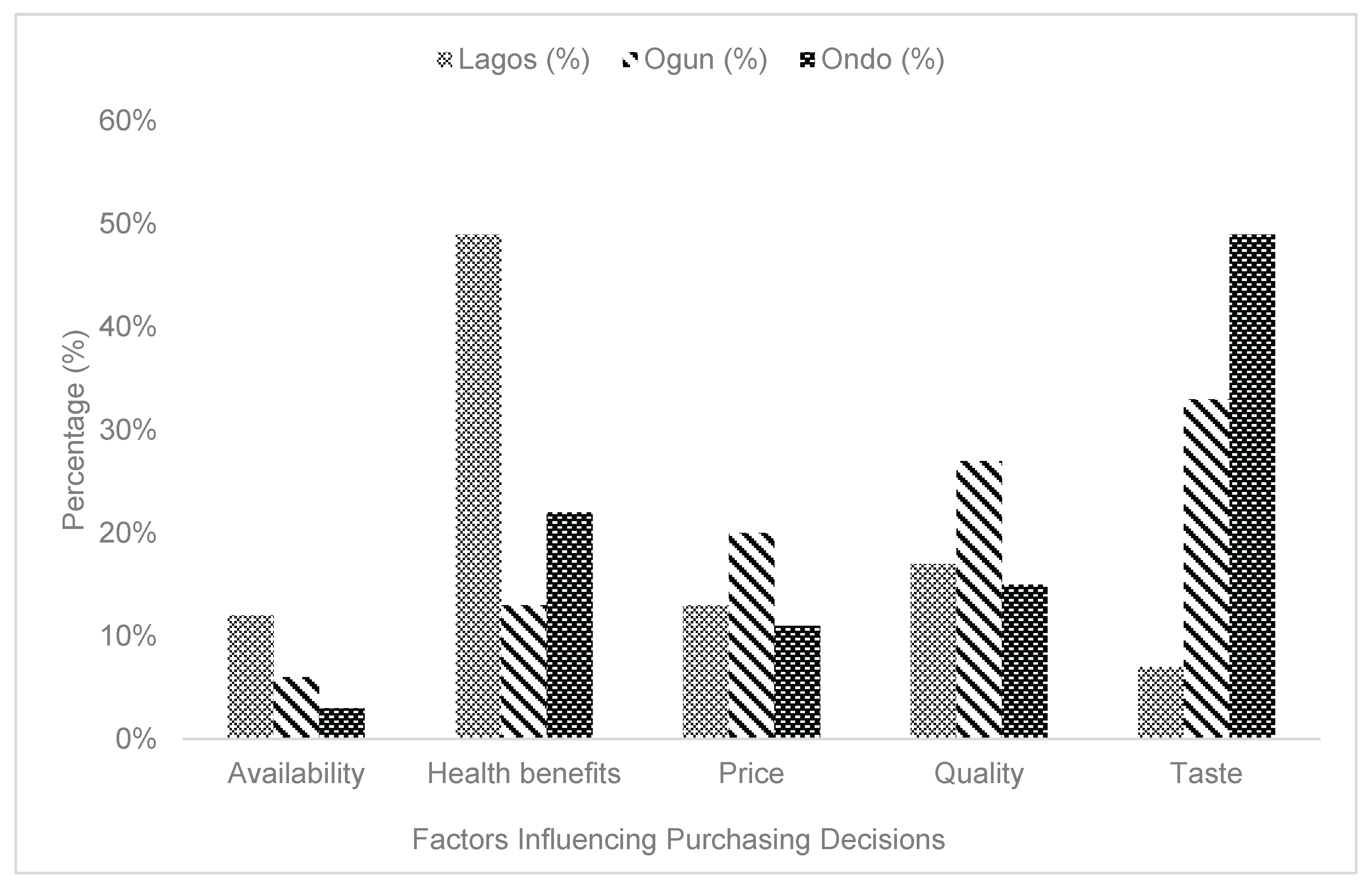

3.11. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Decisions on Aquatic Foods Across Coastal States

The factors guiding consumers’ purchase decisions on the consumption of aquatic foods are presented in

Figure 7. Responses to the following factors, availability, health benefits, price, quality, and taste, were different across the three coastal states. For instance, 49.2% of the respondents in Lagos considered health benefits the most important consideration in their decision to consume aquatic food, compared to 49.2% of respondents from Ondo who favoured that taste consideration is the most important factor that drives their purchase decisions. In Ondo State, taste is the most important factor influencing their choice of aquatic food consumption. In both Ondo and Ogun States, availability is the least factor that would persuade their consumption, unlike in Lagos State, taste is the least factor that would sway their choice of consumption of aquatic foods.

Figure 4.

Methods used by traders to promote sales of aquatic foods.

Figure 4.

Methods used by traders to promote sales of aquatic foods.

Figure 5.

Frequency of aquatic food consumption across the three coastal states.

Figure 5.

Frequency of aquatic food consumption across the three coastal states.

Figure 6.

Perception of consumers of the quality of local aquatic foods.

Figure 6.

Perception of consumers of the quality of local aquatic foods.

Table 3.

Postharvest Practices and value addition in across the coastal States.

Table 3.

Postharvest Practices and value addition in across the coastal States.

| Questions |

Lagos State |

Ogun State |

Ondo State |

| n=79 |

% |

n=78 |

% |

n=77 |

% |

| Do you have access to proper storage facilities? |

|

|

|

| Yes |

71 |

90 |

39 |

50 |

31 |

40 |

| No |

8 |

10 |

39 |

50 |

46 |

60 |

| If no, what storage methods do you use? |

|

| |

| Cold room facility |

0 |

|

30 |

38.5 |

7 |

9 |

| Ice boxes |

0 |

|

7 |

8.9 |

0 |

|

| Open-air storage |

71 |

90 |

35 |

44.9 |

62 |

80 |

| Smoking method |

8 |

10 |

6 |

7.7 |

8 |

10 |

| Do you face any power outages that affect your business operations? |

|

| Yes |

32 |

40 |

68 |

87.2 |

69 |

90 |

| No |

47 |

60 |

10 |

12.8 |

8 |

10 |

| How do you add value to the fish you market/sell? |

|

| Adding salt and pepper, |

8 |

10 |

15 |

19.2 |

15 |

19 |

| Sun-drying |

15 |

19 |

7 |

8.9 |

23 |

30 |

| Clean with red oil |

0 |

0 |

6 |

7.7 |

0 |

0 |

| Sun-drying with salt and pepper |

8 |

10 |

7 |

8.9 |

0 |

0 |

| Unique packaging |

0 |

0 |

5 |

6.4 |

17 |

22 |

| Smoking |

24 |

30 |

38 |

48.7 |

12 |

16 |

| Processing |

24 |

30 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

13 |

Table 4.

Consumers’ perception of imported aquatic foods, new products (seaweeds) and willingness to pay for sustainable aquatic foods.

Table 4.

Consumers’ perception of imported aquatic foods, new products (seaweeds) and willingness to pay for sustainable aquatic foods.

| Questions |

Lagos State |

Ogun State |

Ondo State |

| n=79 |

% |

n=78 |

% |

n=77 |

% |

| How do you perceive the quality of imported aquatic foods? |

|

|

|

| Very High |

5 |

5.8 |

8 |

10.3 |

4 |

5.0 |

High

Medium

Low

Very low

Would you be interested in trying new types of aquatic foods?

No

Yes

Are you willing to pay more for sustainable aquatic foods?

No

Yes

|

17

23

28

06

5

74

14

65 |

21.7

29.2

35.8

7.5

5.8

94.2

17.5

82.5 |

25

38

703

75

16

62 |

32.1

48.7

8.903.8

96.2

20.5

79.5 |

33

12

7

21

8

69

12

65 |

43.3

15

9.2

27.5

10.4

89.2

15

85

|

Figure 7.

Factors influencing consumers’ purchasing decisions on aquatic food.

Figure 7.

Factors influencing consumers’ purchasing decisions on aquatic food.

4. Discussion

Various types of aquatic food are produced and sold in Nigeria, with finfish being the most prevalent, while aquatic plants remain relatively uncommon. Lagos State has a high production of shellfish, confirming previous observations. According to the findings presented in [

35], finfish constitute the dominant aquatic food source in Nigeria, accounting for 94% of total production by volume. Crustaceans contribute 5%, while molluscs represent the remaining 1%. This aligns with the diversity of fish produced in the coastal states in this report. [

35] reported that despite high seaweed biodiversity in Nigeria’s coastal waters, they are a largely unexplored area for marine resources. [

36] reported that the domestic seafood market for shrimp and prawn is a mix of the modern and the traditional.

The distribution channels for aquatic foods vary according to the specific economic and logistical dynamics of each state. Lagos State stands out in terms of the daily frequency of aquatic food sales, reflecting its strategic economic role, extensive distribution networks, and status as a major market hub [

36]. The presence of major seaports such as Apapa and Tin Can Island further reinforced this position, enhancing Lagos State’s role as a central hub for aquatic food distribution and trade. Role switching, which is common in Lagos, is a marketing strategy adopted by smaller distributors who may not have sufficient capital to stay or act only as a wholesaler. A similar view, wholesaler/retailer switch roles, is indicated in [

39]. Wholesalers are independent traders who purchase fresh fish in bulk directly from farm gates and subsequently supply it to various retailers, including market women, fish processors, retail shops, and smaller-scale distributors.

Sales to domestic markets are dominant across all three coastal states, demonstrating that Nigeria is a high fish-consuming nation, and the aquatic food chain is an important economic activity. [

1] averred that aquatic food value chains have emerged spontaneously as clusters of economic activity in response to the pull of domestic demand and favourable conditions for fish production and distribution, in terms of environment and geography. The rising cost of imported fish products since 2015, coupled with the devaluation of the Naira in 2019, has created a more favorable environment for domestic fish producers to compete effectively in the local market [

40]. With a vibrant domestic fish market and promising export prospects, the aquatic food value chain presents significant investment opportunities—particularly as government efforts to diversify the economy increasingly prioritize agriculture-related sectors. There is also the government policy to reduce dependence on fish importation. All these factors serve as strong incentives for IMTA to gain government interest and backing, positioning it as a promising avenue for attracting and encouraging investment in the aquatic food sector.

Traditional means of communication between traders and consumers were dominant in the coastal states, with WOM being the most prevalent. WOM marketing process is one of the main means by which consumers obtain information in economically developing countries. WOM may contribute to the development of the food market [

41]. [

42] stated that WOM has been one of the most influential channels of consumer information globally for the past half-century. WOM is defined in another way as non-commercial, informal, and person-to-person communication between a sender and receiver about a product, service, brand, or organisation [

43]. Investors in IMTA are expected to use WOM and other innovative communication strategies.

Marketers in coastal communities employed a range of innovative strategies to reduce losses and wastage, supporting their sustainable livelihoods. Nonetheless, sun-drying and smoking remain the most widely practiced and well-documented methods in existing literature [44, 23]. They noted that a poor electric power supply hinders cold storage, which is quite important for aquatic food, given high spoilage tendencies. Climate-smart fish production (fisheries and aquaculture) remains largely restricted to the production of only the aquatic food value chain. An extensive review of existing literature revealed that information on climate-smart postharvest practices, as well as strategies for mitigating and adapting to climate change, remains relatively scarce. In the context of the AABS project, Nigeria should be prioritized during the exchange in work package 3.

For coastal communities, fish is even more important as a source of nutrition, as well as a base of the coastal economy [46], which supports the daily frequency of aquatic food consumption in this study. [

37] indicated that shrimp consumption in the Degema Local Government Area of Rivers State, Nigeria, is relatively high, as the community is familiar with the shrimps, and this aids their consumption. In their study, they identified several key factors influencing the consumption of shrimp and prawn, including their availability, appealing taste, rich nutrient profile, ease of chewing, low fat, and notable health benefits. These findings align closely with the observations made in the present study.

5. Conclusions

Production nodes of the aquatic food value chain consist of different aquatic food types, largely dominated by finfishes, while seaweeds, despite their diversity and availability, are rare in production. The market is primarily targeted for local consumption and a developing niche export market, regionally and outside the region. For most traders in the coastal state examined, annual sales volumes typically fall within the range of 1 to 5,000 tons. The marketing mix showed that traditional WOM is the most effective channel of communication between traders and consumers. Sun-drying and smoking are the most common strategies to reduce postharvest loss and wastage. Consumers are influenced by factors such as perceived health benefits and availability. A successful IMTA project is expected to change the dynamics and structure of the aquatic food production and marketing, especially with the addition of aquatic plants and shellfish production, improved post-harvest infrastructure, which can promote food and nutrition security as well as products destined for industry.

6. Recommendation

The following recommendations are proposed to improve the effectiveness, sustainability, and economic viability of the aquatic food value chain:

Strengthen Cold Chain Infrastructure: Post-harvest losses are a concern, and Nigeria could benefit from activities and outcomes related to Work Package 3 of the AABS- Climate-Smart Technologies for Reducing Aquatic Food Loss and Waste.

Promote and Scale Up Aquatic Plant: Aquatic plants need to be promoted for their use, especially for phytoremediation, as reported in the earlier study. Local variants suitable for each study location should be adopted in the second phase of the IMTA project in Nigeria.

Facilitate Access to New and Broader Markets: With existing sales largely focused on local markets, policy and infrastructural support are needed to develop niche regional and international markets. This can be achieved through branding, certification, and standardization of aquatic food products to meet export requirements. IMTA would be expected to broaden cultured species diversity.

Leverage Digital Marketing and E-commerce: The dominance of word-of-mouth (WOM) communication in the marketing mix should be augmented with digital platforms such as mobile applications, social media, and e-commerce channels to reach a broader consumer base, especially among younger and tech-savvy demographics. It is expected that innovative strategies would be included to the WOM by investors in IMTA.

Consumer Awareness and Nutrition Education: Given the strong influence of perceived health benefits and taste on consumer preferences, public awareness campaigns should be intensified to promote the nutritional advantages of diverse aquatic foods, including lesser-known products like aquatic plant, which is a major feature in IMTA.

Support Local Traders and Producers through Policy Interventions: Government policies that provide financial assistance, input subsidies, and cooperative frameworks for existing small-scale fishers, farmers, and traders should be maintained to safeguard community support for investors in IMTA. These measures are vital for boosting productivity and strengthening resilience against environmental and economic pressures.

Encourage Value Addition and Product Diversification: Investments in value-added processing, such as ready-to-cook or ready-to-eat aquatic food products, should be promoted to improve profitability and attract diverse consumer segments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Shehu L. Akintola, Sunil Siriwardena, Charles Iyangbe, Esther W. Magondu, and Rodrigue Yossa. Methodology, Shehu L. Akintola, Lateef A. Badmos, Akinkunmi S Ojo, Gbenga R. Ajepe, and Matthew A. Ajibade.; Validation, Victor T. Okomoda, Idowu J Fasakin, and Sunil Siriwardena; Formal Analysis, Shehu L. Akintola, Lateef A. Badmos, and Akinkunmi S Ojo.; Investigation, Shehu L. Akintola, Lateef A. Badmos, Akinkunmi S Ojo, Gbenga R. Ajepe, Matthew A. Ajibade.; Resources, Shehu L. Akintola, Lateef A. Badmos, Akinkunmi S Ojo, Gbenga R. Ajepe, Matthew A. Ajibade; Data Curation, Shehu L. Akintola, Lateef A. Badmos, Akinkunmi S Ojo, Gbenga R. Ajepe, Matthew A. Ajibade.Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Shehu L. Akintola, Lateef A. Badmos, Akinkunmi S Ojo, Gbenga R. Ajepe, Matthew A. Ajibade.; Writing—Review & Editing, Shehu L. Akintola, Lateef A. Badmos, Akinkunmi S Ojo, Gbenga R. Ajepe, Matthew A. Ajibade, Mary A. Gbadamosi, Victor T. Okomoda, Idowu J Fasakin, Sunil Siriwardena, Charles Iyangbe, Esther W. Magondu and Rodrigue Yossa; Visualization, Shehu L. Akintola.; Supervision, Esther W. Magondu and Rodrigue Yossa.; Project Administration, Shehu L. Akintola, Sunil Siriwardena, Charles Iyangbe, Esther W. Magondu, and Rodrigue Yossa.; Funding Acquisition, Rodrigue Yossa’.

Funding

Funding support for this project was provided by the UK International Development from the UK government (FCDO Project Number: 301203—Asia-Africa BlueTech Superhighway). The APC was funded by [FCDO].

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy, legal, and ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

This work was undertaken as part of the Asia-Africa BlueTech Superhighway (AABS), led by WorldFish and Lagos State University (LASU) is the partnering institution. Funding support for this project was provided by the UK International Development from the UK government; however, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies. The contributions of respondents are well appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Abbreviations

AABS- Asia-Africa BlueTech Superhighway—WorldFish; IMTA- Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture; LGAs- Local Government Areas; LCDAs- Local Council Development Areas; WOM- Words of Mouth

References

- Liverpool-Tasie LSO, Wineman A, Amadi MU, Gona A, Emenekwe CC, Fang M, et al., Rapid transformation in aquatic food value chains in three Nigerian states, Front Aquac, 3:1302100, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tezzo X, Bush SR, Oosterveer P, Belton B, Food system perspective on fisheries and aquaculture development in Asia, Agric Hum Values, 38(1):73–90, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, FAOStat fisheries and aquaculture database, 2023. Available from: https://www.fao.org/fishery/en/information (Accessed 2025 Apr 9).

- Chopin T, Buschmann AH, Halling C, Troell M, Kautsky N, Neori A, et al., Integrating seaweeds into marine aquaculture systems: A key toward sustainability, J Phycol, 37(6):975–86, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.K., Hasanuzzaman, A.F.M., Islam, S.S., Sarower, M.G., Mistry, S.K., Arafat, S.T. and Huq, K.A., 2025. Integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA): enhancing growth, production, immunological responses, and environmental management in aquaculture. Aquaculture International 33, p.336. Available at: . [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S., 2019. Challenges and opportunities of IMTA in Hawaii and beyond. Bulletin of the Japan Fisheries Research and Education Agency 49, pp.129–134.

- Sickander, O., & Filgueira, R. (2022). Factors affecting IMTA (integrated multi-trophic aquaculture) implementation on Atlantic salmon (Salmo Salar) farms. Aquaculture, 557, Article 738716. [CrossRef]

- Subasinghe RP, Siriwardena SN, Byrd KA, Chan C, Dizyee K, Shikuku KM, et al., Nigeria fish futures: Aquaculture in Nigeria—Increasing income, diversifying diets and empowering women. WorldFish; 2021.

- Hala AF, Chougule K, Cunha ME, Mendes MC, Oliveira I, Bradley T, et al., Life cycle assessment of integrated multi-trophic aquaculture: A review on methodology and challenges for its sustainability evaluation, Aquaculture, 741035, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Loayza-Aguilar RE, Huamancondor-Paz YP, Saldaña-Rojas GB, Olivos-Ramirez GE, Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture (IMTA): Strategic model for sustainable mariculture in Samanco Bay, Peru. Front Mar Sci, 10:1151810, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Radhakrishnan K, Dheeran P, Rajeshkannan R, Seenivasan P, Raghuvaran N, Naveenkumar R, et al., Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture: A balanced system for sustainable aquaculture. In: Fisheries Biology, Aquaculture and Post-Harvest Management. Vol. 1. NIPA® GENX Electronic Resources & Solutions P. Ltd; 2023.

- Khanjani MH, Zahedi S, Mohammadi A, Integrated multitrophic aquaculture (IMTA) as an environmentally friendly system for sustainable aquaculture: Functionality, species, and application of biofloc technology (BFT), Environ Sci Pollut Res, 29:67513–31, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Knowler D, Chopin T, Martínez-Espiñeira R, Neori A, Nobre A, Noce A, et al., The economics of Integrated Multi-Trophic Aquaculture: Where are we now and where do we need to go? Rev Aquac, 12:1579–94, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Camilleri MA, Cricelli L, Mauriello R, Strazzullo S, Consumer perceptions of sustainable products: A systematic literature review, Sustainability, 15(11):8923, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Mouchtaropoulou E, Mallidis I, Giannaki M, Koukaras K, Früh S, Ettinger T, et al., Consumer willingness to pay for fair and sustainable foods: Who profits in the agri-food chain? Front Sustain Food Syst, 8:1504985, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tran N, Shikuku KM, Hoffmann V, Lagerkvist CJ, Pincus L, Akintola SL, et al., Are consumers in developing countries willing to pay for aquaculture food safety certification? Evidence from a field experiment in Nigeria. Aquaculture, 550:737829, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Ababouch L, Nguyen KAT, de Souza MC, Fernandez-Polanco J, Value chains and market access for aquaculture products, J World Aquac Soc, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Lu J, Xiao Y, Zhang W, Taste, sustainability, and nutrition: Consumers’ attitude toward innovations in aquaculture products. Aquaculture, 587:740834, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Ali H, Belton B, Haque MM, Murshed-e-Jahan K, Transformation of the feed supply segment of the aquaculture value chain in Bangladesh, Aquaculture, 576:739897, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Adam R, Njogu L, A review of gender inequality and women’s empowerment in aquaculture using the reach-benefit-empower-transform framework approach: A case study of Nigeria, Front Aquac, 1:1052097, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Chilaka QM, Nwabeze GO, Odili OE, Challenges of inland artisanal fish production in Nigeria: Economic perspective, J Fish Aquat Sci, 9(6):501–5, 2014. [CrossRef]

- Nwokedi TC, Odumodu CU, Anyanwu JO, Ndikom OC, Gap analysis evaluation of Nigeria’s fish demand and production: Empirical evidences for investment in and policy development for offshore mariculture practices, Int J Fish Aquat Stud, 8(3):384–94, 2020.

- Akintola SL, Fakoya KA, Small-scale fisheries in the context of traditional post-harvest practice and the quest for food and nutritional security in Nigeria, Agric Food Secur, 6:34, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Olagunju OF, Kristófersson D, Tómasson T, Kristjánsson T, Profitability assessment of catfish farming in the Federal Capital Territory of Nigeria, Aquaculture, 555:738192, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Mukaila R, Ukwuaba IC, Umaru II. Economic impact of disease on small-scale catfish farms in Nigeria, Aquaculture, 575:739773, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Gona A, Woji G, Norbert S, Muhammad H, Liverpool-Tasie LS, Reardon T, et al, The rapid transformation of the fish value chain in Nigeria: Evidence from Kebbi State, Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy, Research Paper No. 118, 2018.

- Lagos State Ministry of Agriculture and Food Systems, Lagos Fisheries Programme. Lagos State Ministry of Agriculture and Food Systems, 2025. Available from: https://lagosagric.com/lagos-fisheries-programme/accessed 25 May 2025.

- Yesufu OA, Adejobi AO, Ekpo-Ufot U, Adeogun OI, Economics of fresh fish marketing among fish farmers in Lagos State, Nigeria, Ife J Agric, 27:1–15, 2014.

- Adewuyi SA, Phillip BB, Ayinde IA, Akerele D, Analysis of profitability of fish farming in Ogun State, Nigeria, J Hum Ecol, 31(3):179–84, 2010.

- Agbeja Y, Oluyede E, Oyedepo V, Socio-economic characteristics assessment and livelihood coping strategies of small-scale fisheries in Ogun Waterside Local Government Area, Nigeria Int J Fish Aquat Stud, 9(2):266–76, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Adewuyi SA, Phillip BB, Ayinde IA, Akerele D, Analysis of profitability of fish farming in Ogun State, Nigeria, J Hum Ecol, 31(3):179–84, 2010.

- Agbebi FO, Adetuwo KI, Analysis of socio-economic factors affecting fish marketing in Igbokoda fish market, Ondo State, Nigeria, Int J Environ Agric Biotechnol, 3(2), 2018. [CrossRef]

- Abbas AM, Aiyedun EA, Ebukiba ES, Otitoju MA, Iduseri EO, Olutumise AI, et al., Technical efficiency and profitability analysis of catfish farming in Ondo State, Nigeria, J Agric Sci Environ, 25:39–56, 2025. https://journal.funaab.edu.ng/index.php/JAgSE/article/view/2437.

- Akingba O, Afolabi A, Ayodele P, A study of the socio-economic indices of the fisher folks in five fishing communities in Ondo State, Nigeria, Afr J Fish Sci, 5(3):222–28, 2017.

- GlobeFish. Nigeria market profile, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2020. Available from: https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/8abfe048-7709-4ba7-a710-19256147af11/content (Accessed 2025 Apr 19).

- Kadiene EU, Biaoku DO, Bolaji DA, Ekele S, Adewunmi EK, Oluwatobi A, et al., Exploration of the seaweed resources in Nigeria: A case study of Lagos coastal waters, Open J Mar Sci, 15(1):13–34, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kalio GA, Amadi EE, Feniobu FT, Preliminary studies on the factors influencing consumers’ preference for shrimp and prawn in Degema Local Government Area of Rivers State, Nigeria, Direct Res J Agric Food Sci, 8(11):303–10, 2020. Available from: https://directresearchpublisher.org/drjafs/.

- US International Trade Administration. Distribution and sales channels, 2025. Available from: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/nigeria-distribution-and-sales-channels (accessed 19th April, 2025).

- Business Innovation Facility, Nigeria market analysis and strategy: Aquaculture, 2014. Available from: https://www.nipc.gov.ng/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Market-Analysis-and-Strategy-Aquaculture-1.pdf (accessed 20 April 2025).

- Liverpool-Tasie LSO, Sanou A, Reardon T, Belton B, Demand for imported versus domestic fish in Nigeria. J Agric Econ, 72:782–804, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Boccia F, Tohidi A, Analysis of green word-of-mouth advertising behavior of organic food consumers. Appetite, 198:107324, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chang SH, Chang CW, Tie strength, green expertise, and interpersonal influences on the purchase of organic food in an emerging market, Br Food J, 119(2):284–300, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Jaharuddin NS, Influences of background factors on consumers’ purchase intention in China’s organic food market: Assessing the moderating role of word-of-mouth (WOM), Cogent Bus Manag, 8(1):1876296, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Akintola SL, Fakoya KA, Elegbede IO, Odunayo EO, Lekan TJ, Chapter three: Postharvest practices in small-scale fisheries, In: Postharvest loss and food waste in fisheries and aquaculture, 2022. [CrossRef]

- CGIAR Research Program on Aquatic Agricultural Systems, Resilient livelihoods and food security in coastal aquatic agricultural systems: Investing in transformational change, Penang, Malaysia: CGIAR, Project Report: AAS-2012-28, 2012.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).