Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

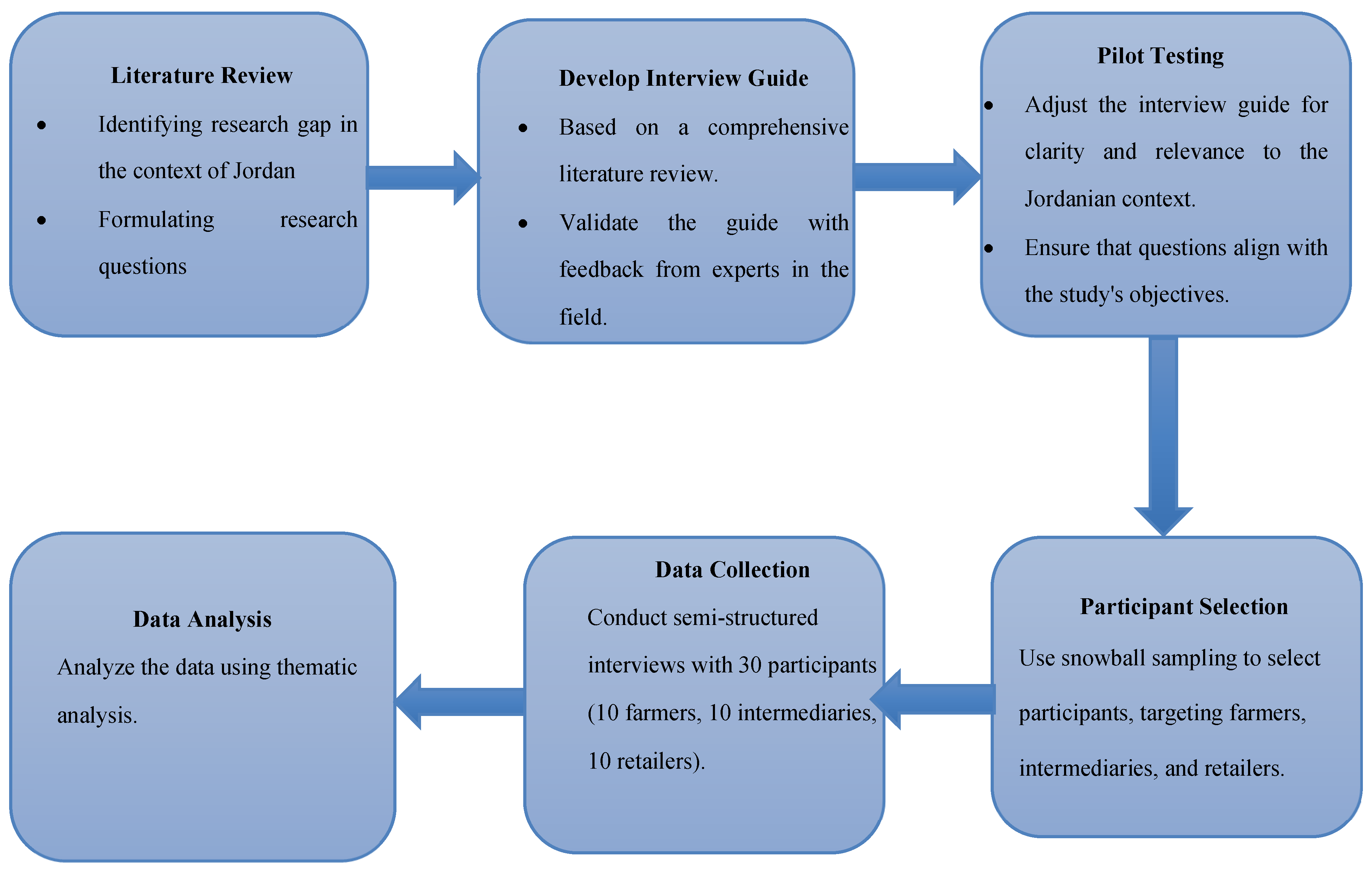

3. Methodology

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Supply Chain Relationships and Communication

4.2. Market Dynamics and Consumer Behavior

4.3. Supply Chain Operations and Efficiency

4.4. Supply Chain Sustainability

4.5. Challenges and Opportunities

4.6. Future Outlook and Adaptation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SFSC | Short food supply chain |

| FSC | Food supply chain |

References

- Wang, M. Evaluating the role of short food supply chains as a driver of sustainability: Empirical evidence from China. Unpublished. Doctoral Dissertation, Faculty of Business and Law, University of the West of England, Bristol, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Jarzębowski, S.; Bourlakis, M.; Bezat-Jarzębowska, A. Short food supply chains (SFSC) as local and sustainable systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vittersø, G.; Torjusen, H.; Laitala, K.; Tocco, B.; Biasini, B.; Csillag, P. , et al. Short food supply chains and their contributions to sustainability: Participants’ views and perceptions from 12 European cases. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Agriculture. Annual Agricultural Statistical Report 2022. Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, /: Retrieved from https.

- World Bank. Jordan: Distribution of gross domestic product (GDP) across economic sectors from 2012 to 2022. Statista, /: Retrieved , 2024, from https, 26 November 2024.

- Figueroa, J.L.; Mahmoud, M.; Breisinger, C. The role of agriculture and agro-processing for development in Jordan. Intl. Food Policy Res. Inst. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture. The National Food Security Strategy 2021–2030. Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, /: Retrieved from https.

- Bazzani, C.; Canavari, M. Alternative agri-food networks and short food supply chains: A review of the literature. Econ. Agro-Alimentare 2013, 15, 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paciarotti, C.; Torregiani, F. The logistics of the short food supply chain: A literature review. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomé, K.M.; Cappellesso, G.; Ramos, E.L.A.; de Lima Duarte, S.C. Food supply chains and short food supply chains: Coexistence conceptual framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amentae, T.K. Supply chain management approach to reduce food losses. Acta Univ. Agric. Sueciae 2018, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mohajan, H. The First Industrial Revolution: Creation of a New Global Human Era (No. 96644). University Library of Munich, Germany 2019.

- La Scalia, G.; Settanni, L.; Micale, R.; Enea, M. Predictive shelf life model based on RF technology for improving the management of food supply chain: A case study. Int. J. RF Technol. 2016, 7, 31–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartikainen, H.; Mogensen, L.; Svanes, E.; Franke, U. Food waste quantification in primary production: The Nordic countries as a case study. Waste Manag. 2018, 71, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Vorst, J.G.; Tromp, S.-O.; Zee, D.-J.V.D. Simulation modeling for food supply chain redesign: Integrated decision making on product quality, sustainability, and logistics. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2009, 47, 6611–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbery, B.W. Food supply chains: The long and short of it. 2009.

- Gori, F.; Castellini, A. Alternative food networks and short food supply chains: A systematic literature review based on a case study approach. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktar, M.W.; Sengupta, D.; Chowdhury, A. Impact of pesticides use in agriculture: Their benefits and hazards. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 2009, 2, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, S.; Wiek, A.; Bloemertz, L.; Bornemann, B.; Granchamp, L.; Villet, C. , et al. Opportunities and challenges of food policy councils in pursuit of food system sustainability and food democracy: A comparative case study from the Upper-Rhine region. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 6, 916178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, G.; Mulligan, C. Competitiveness of small farms and innovative food supply chains: The role of food hubs in creating sustainable regional and local food systems. Sustainability 2016, 8, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, P.; Borit, M. The components of a food traceability system. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 143–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Misleh, D. Moving beyond the impasse in geographies of ‘alternative’ food networks. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2022, 46, 1028–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, F.; Shahzadi, G.; Bourlakis, M.; John, A. Promoting resilient and sustainable food systems: A systematic literature review on short food supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 140364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. EU No. 1305/2013 of the European Parliament and Council of 17 December 2013 on support for rural development by the European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development, EAFRD, and repealing Council Regulation EC No. 1698/2005. European Commission, 17 December.

- Manzini, R.; Accorsi, R. The new conceptual framework for food supply chain assessment. J. Food Eng. 2013, 115, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, C.; Scott, S.; Geddes, A. Snowball sampling. SAGE Res. Methods Found. 2019.

- DeJonckheere, M.; Vaughn, L.M. Semi-structured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Fam. Med. Community Health 2019, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, S.; Anand, N. Issues and challenges in the supply chain of fruits & vegetables sector in India: A review. Int. J. Manag. Value Supply Chains 2015, 6, 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Chiffoleau, Y.; Dourian, T. Sustainable food supply chains: Is shortening the answer? A literature review for a research and innovation agenda. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, M.M.; Chang, Y.S. Temperature management for the quality assurance of a perishable food supply chain. Food Control 2014, 40, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubi, E. , Shbikat, N.; Noche, B. A system dynamics model to improving sustainable performance of the citrus farmers in Jordan Valley. Cleaner Prod Lett 2023, 4: 100034.

| Dimension | Conventional/long FSC | SFSC |

| Distance | Long physical distances between producers and consumers [23] | Close physical distance between producers and consumers [17,24] |

| Number of Intermediaries | Many result in distant/ impersonal relationships between producers and consumers [9] | Few or none, resulting in direct /interpersonal relationships between producers and consumers [17] |

| Complexity | Mass (large-scale) production, standardized products, intensification, monoculture, global markets, large corporations control market, and lack of transparency /shared information [10,17,20] | Small-scale production, difference and diverse products, biodiversity, local markets, Independent of corporate influence, community-driven, transparency/shared information [17,22] |

| Time | Manufactured/processed products, global markets, distant/ impersonal relationships [9,17,22] | Natural/fresh products, local markets, and direct/interpersonal relationships [8,22] |

| Flexibility and Responsiveness | Mass (large-scale) production, standardized products, global markets, distant relationships, and dis-embedded relationships [17,22] | Small-scale production, diversity of products, local markets, direct relationships, embedded relationships [22] |

| Environmental Impact | Agrochemicals, monoculture, minimal focus on sustainability, high exploitation of nature/communities [17,25] |

Organic/sustainable farming, biodiversity, significant focus on sustainability, low exploitation of nature/communities [20,23] |

| Cost | Mass (large-scale) production, global markets, and high exploitation of nature/communities [10,17] | Small-scale production, local markets, low exploitation of nature/communities [17] |

| Farmers | Position | Years of experience | Education level |

| 1 | Owner | 28 years | High school education |

| 2 | Owner | 20 years | Primary school education |

| 3 | Owner | 9 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 4 | Owner | 30 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 5 | Owner | 34 years | High school education |

| 6 | Owner | 12 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 7 | Owner | 10 years | Diploma |

| 8 | Owner | 35 years | High school education |

| 9 | Owner | 6 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 10 | Owner | 40 years | Ph.D. in Agriculture |

| Intermediaries | |||

| 1 | Owner | 40 years | Secondary education |

| 2 | Owner | 30 years | Secondary education |

| 3 | Owner | 25 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 4 | General manager | 40 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 5 | Company manager | 4 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 6 | Owner | 40 years | College Education |

| 7 | Administrator | 38 years | Diploma |

| 8 | Owner | 27 years | Secondary education |

| 9 | Owner | 35 years | Diploma |

| 10 | Partner and Manager | 45 years | Master’s degree |

| Retailers | |||

| 1 | Manager of fresh food | 14 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 2 | Supervisor of fresh food | 18 years | High school |

| 3 | Supervisor of fresh food | 6 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 4 | Supervisor of fresh food | 5 years | College Education |

| 5 | Owner and manager | 35 years | Primary school education |

| 6 | Purchase manager | 20 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 7 | Owner and manager | 7 years | High school |

| 8 | Purchasing officer | 6 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 9 | Store manager | 8 years | Bachelor’s degree |

| 10 | Supervisor of fresh food | 5 years | High school |

| Dimension | Farmer | Intermediary | Retailer |

| Trust and Communication | ● Relationships with intermediaries and retailers are based on mutual trust and strong communication. As Farmer 1 stated: “Our relationship relies on mutual trust, and we maintain strong communication to ensure smooth transactions and address any challenges.” ● Long-term relationships with intermediaries are common, as they rely on them to handle their products. ● Clear and frequent communication helps adjust quantities and discuss payments. |

● Trust is critical in relationships with both farmers and retailers. ● Often provide farmers financial support, strengthening trust and ensuring a stable supply chain. As Intermediary 2 highlighted, “Trust and commitment in relationships exist because the intermediary financially supports and funds the farmers. ● Open communication covers pricing, quantities, and logistics. |

● Trust in intermediaries is essential for consistent product quality and supply. ● Daily communication ensures effective inventory management and discusses payment schedules and order adjustments. ● As Retailer 10 stated, “We maintain regular communication with intermediaries to discuss payment schedules and make necessary adjustments to our orders based on market demand.” |

| Flexibility in Payment and Order Quantities | ● Deferred intermediary payments provide financial flexibility, especially during fluctuating production levels or unexpected costs. Farmer 2 explained, “The option for deferred payments from intermediaries helps us manage cash flow.” |

● Offer credit to farmers in exchange for exclusive supply agreements and deferred payments to retailers, ensuring smooth operations. As Intermediary 3 remarked, “We provide credit to farmers in exchange for exclusive supply agreements and offer deferred payments to retailers.” ● Adjust quantities purchased from farmers based on market demand to maintain efficiency. |

● Flexibility in payment options includes credit and adjusted schedules based on cash flow. ● Daily purchases from the central market allow order adjustments based on sales, reducing the risk of overstocking or spoilage. Retailer 7 mentioned, “Purchasing products daily from the central market gives us the flexibility to adjust our orders according to sales.” |

| Direct vs. Indirect Sales Channels | ● Primarily sell through intermediaries at the central market. ● Occasionally sell directly to retailers or local consumers, offering more transparency and sometimes better prices. Farmer 1 stated, “While we primarily rely on intermediaries at the central market to sell our produce, there are times when we sell directly to retailers or local consumers.” |

● Serve as the main link between farmers and retailers, managing logistics and market negotiations. ● Operate in the central market, ensuring product flow to retailers. As Intermediary 9 explained, “We operate in the central market, and our main role is to manage the flow of products from farmers to retailers.” ● Some intermediaries also sell directly to consumers or export markets. |

● Typically purchase from intermediaries at the central market. ● Occasionally buy directly from farmers for certain products, which allows for fresher produce and more control over quality and pricing. As Retailer 3 stated, “We generally purchase from intermediaries at the central market, but we buy certain products directly from farmers.” |

| Information and Product Traceability | ● Some provide labels with the farm’s name and location, but this is not common. ● Rely on intermediaries to communicate product information verbally to retailers and consumers. Farmer 4 noted, “We include labels with details about our farm and its location, but it’s not something that all farmers do regularly.” |

● Provide basic information about the farm and product origin, usually shared informally. ● Can trace products back to the farm but depend on verbal communication rather than formal systems. As Intermediary 9 explained, “We can trace products back to the farm but rely on verbal communication rather than formal systems for traceability.” |

● Rely on intermediaries for product origin information. ● Some place signs indicating locally sourced products, while others rely on staff to inform consumers upon request. Retailer 4 explained, “We often depend on intermediaries to tell us where the products come from. Sometimes, we place signs to show that products are locally sourced, but in many cases, our staff provides this information to consumers when they ask.” ● Traceability is limited and largely dependent on intermediaries. |

| Dimension | Farmer | Intermediary | Retailer |

| Consumer Demand for Local Products | ● Observed a significant shift in consumer preferences toward local fruits and vegetables, particularly during the pandemic. ● Consumers prioritize quality, freshness, availability, and safety of local produce. Farmer 6 remarked, “Consumers are more inclined to purchase local products due to quality, freshness, and availability.” ● Increased demand has positively impacted production and sales. |

● Confirmed a rise in demand for local produce, especially essential items like vegetables and citrus fruits, during the pandemic. ● Attributed the trend to consumer awareness of the benefits of fresh, locally sourced food. ● Noted that local products are competitively priced and readily available. As Intermediary 9 noted, “Local products tend to be more competitively priced and readily available, which makes them more attractive to consumers.” |

● Reported a growing consumer preference for local products due to their quality, affordability, and freshness. ● Highlighted consumer interest in knowing the origin of food and trust in the local supply chain. As Retailer 5 stated, “Consumers increasingly prefer local products due to trust in the local supply chain and the affordability of fresh options.” ● Local products meet demand consistently, fostering consumer loyalty. |

| Impact of the Pandemic on Consumer Purchasing Behavior | ● experienced a surge in demand for fresh products, especially vegetables and fruits. ● Attributed the increase to import restrictions, which shifted consumer focus to local options. Farmer 2 noted, “Demand has increased during the pandemic due to import restrictions, which have limited the availability of imported products and shifted consumer focus toward local options.” ● Emphasized the pandemic’s role in highlighting the importance of local food security. |

● Observed a spike in demand for essential products like vegetables and citrus fruits. ● Linked the trend to consumer preference for fresh and readily available products. As Intermediary 7 explained, “The increased preference for fresh and readily available products has led to increased demand.” ● Noted that supply disruptions in imported products further drove demand for local produce. |

● Reported increased demand for all fresh products, especially staple items such as vegetables and citrus fruits. ● Saw a rise in sales as consumers shifted purchasing priorities to locally available products. Retailer 7 noted, “We saw a significant rise in sales as consumers shifted their purchasing priorities toward locally available products.” ● Highlighted that consumers continue to favor local products even post-pandemic. |

| Seasonal Availability and Demand Fluctuations | ● Acknowledge that demand fluctuates with the seasons, with specific fruits and vegetables in higher demand at certain times. ● Typically meet market demand through local production but face occasional shortages when demand exceeds supply. Farmer 6 explained, “We can usually satisfy the market’s needs with local production, with occasional shortages when demand exceeds supply.” |

● Adjust product sourcing based on seasonal demand and availability. As Intermediary 2 explained, “We adjust the types of products we source based on season and product availability.” ● Manage shortages of specific items during out-of-season periods or adverse weather by relying on imports. ● Note that locally grown items are preferred when available. |

● Observe seasonal fluctuations in demand, with higher demand for certain products during peak seasons. As Retailer 4 remarked, “Demand for fresh products fluctuates seasonally, with higher demand for certain products during specific seasons.” ● Adapt by adjusting orders based on expected sales and seasonal availability. ● Supplement with imports when local products are unavailable, but generally, consumers prefer the taste and freshness of local produce |

| Influence of Price and Affordability on Consumer Preferences | ● Emphasize that competitive pricing of local produce is a key driver of consumer preference. As Farmer 7 stated, “Competitive pricing of local produce is a major reason for increased consumer preference.” ● Affordability attracts a broader customer base, particularly during economically challenging times. |

● Pricing is determined by supply and demand, with local produce often being more competitively priced than imports. As Intermediary 10 mentioned, “Pricing is dictated by supply and demand, and local produce is often more competitively priced than imports.” ● High prices due to limited supply or increased demand can reduce consumer purchases. |

● Affordable local products attract price-sensitive consumers. Retailer 2 noted, “Affordable local products attract consumers sensitive to price fluctuations.” ● Price competition with imports affects purchasing decisions, with a preference for competitively priced local items. ● Prioritize stocking affordable local products to maintain customer loyalty and stable demand. |

| Dimension | Farmer | Intermediary | Retailer |

| Handling and Transportation Processes | ● Transport produce directly to intermediaries at the central market, covering distances of 60-130 km depending on farm location. Farmer 7 explained, “Products are transported directly from the farm to intermediaries in the central market.” ● Use trucks and, in some cases, refrigerated vehicles to maintain freshness. ● Rely on manual handling tools, emphasizing minimal handling to prevent damage. ● Aim to keep transport time between 10 to 30 hours from harvest to market arrival. |

● Receive products at the central market, where they handle sorting, display, and sale to retailers. ● Maintain rapid turnaround within the market space to avoid long storage times. As Intermediary 3 noted, “We manage sorting, display, and sale to retailers, maintaining a rapid turnaround within the market space.” ● Use labor and manual handling tools, such as pallet jacks, ensuring minimal handling to prevent spoilage. |

● Acquire products from either farmers or intermediaries at the central market. ● Use their trucks, refrigerated vehicles, or rental transport to ensure good product condition upon store arrival. Retailer 6 stated, “We acquire products either directly from farmers or intermediaries at the central market, often using our vehicles for transport.” ● Employ labor and manual tools like pallet jacks for product handling. |

| Storage and Spoilage Management | ● Avoid long-term storage to reduce costs and spoilage risk, ensuring freshness by transporting products immediately after harvest. As Farmer 10 remarked, “Products are transported immediately after harvest, avoiding long-term storage to reduce spoilage risk.” ● Occasionally use rented facilities for short-term storage of specific items like pomegranates. |

● Store products at the central market for short durations, typically one to two days, depending on product type. As Intermediary 1 explained, “Storage time depends on the type of product, but most products are stored for one to two days.” ● Use shaded areas and wooden crates elevated to ensure air circulation. ● Use cooling rooms for items with longer shelf lives, like potatoes. ● Reduce prices during low demand to accelerate sales and prevent spoilage. |

● Manage daily orders to minimize storage times and prevent quality decline. ● Storage depends on the product type; items like potatoes and onions can be stored for several days without significant quality loss. ● Repurpose items into juices or salads if quality declines and offer discounts or promotions to sell older stock quickly to reduce spoilage. Retailer 6 noted, “If quality declines, we may repurpose items into juices or salads and offer discounts to reduce spoilage.” |

| Cost Components of the Supply Chain | ● High production costs, driven by rising prices of inputs like fertilizers and pesticides, significantly impact profitability. As Farmer 8 stated, “High production costs, especially due to rising prices of inputs like fertilizers and pesticides, impact our profitability.” ● Transportation costs are relatively low due to short distances between farms and markets. |

● Major costs include labor, operational expenses, and storage at the central market. ● Spoilage costs affect profitability, as some products need to be sold at reduced prices to avoid waste. As Intermediary 3 explained, ● “Spoilage costs impact profitability, as some products must be sold at reduced prices to minimize waste.” |

● Primary expenses are product acquisition, transportation, and operational costs. ● Spoilage costs are challenging, especially for perishable items that don’t sell quickly. ● Frequently adjust prices or run promotions to reduce spoilage losses. As Retailer 8 stated, “We adjust prices and offer promotions to minimize losses from spoilage.” ● Retailers with delivery services face additional expenses for refrigerated vehicles and logistics. |

| Delivery Services and Quality Maintenance | ● Focus on quick and direct transportation from farm to market to preserve freshness and minimize handling. As Farmer 5 remarked, “We primarily focus on quick and direct transportation from farm to market to preserve freshness.” ● Do not offer direct delivery to consumers, as transactions primarily occur at the central market with intermediaries. |

● Manage distribution from farmers to retailers, ensuring products are promptly displayed for sale at the central market. ● Minimize storage times to maintain product quality. As Intermediary 4 stated, “We ensure products are promptly displayed for sale at the central market, minimizing storage times.” ● Do not provide direct delivery to consumers. |

● Provide direct delivery services to consumers using refrigerated trucks or partnering with delivery companies. Retailer 4 mentioned, “Refrigerated trucks are used to ensure quality is maintained during direct delivery to consumers.” ● Focus on minimizing delivery time to maintain freshness and meet consumer expectations for high-quality produce. |

| Dimension | Farmer | Intermediary | Retailer |

| Environmental Sustainability | ● Reduce chemical fertilizer and pesticide use due to shorter supply distances, minimizing the need for prolonged crop preservation. ● Use simple and minimal packaging to lower resource usage and costs. As Farmer 10 stated, “shorter distances involved in supplying local markets reduce the need for extensive packaging, instead using simple packaging with minimal wrapping.” ● Short transport distances reduce fuel consumption. |

● Collaborate with recycling entities to reuse containers multiple times, reducing packaging waste. ● Minimize packaging when supplying local markets, which reduces environmental impact. Intermediary 6 noted that “supplying local markets reduces the need for packaging, and containers are reused multiple times to lower waste.” |

● Some employ eco-friendly packaging options and consolidate deliveries to reduce fuel use. Retailer 1 mentioned, “We use eco-friendly bags and consolidate deliveries to reduce fuel use.” ● Collaborate with recycling entities to reuse containers and reduce waste. ● Control order quantities based on daily sales to minimize food waste. |

| Economic Sustainability | ● Experience increased financial stability SFSCs, as they are less affected by external market disruptions. ● Fluctuating prices, high input costs, and competition challenge profitability. Farmer 4 explained that “SFSCs provide increased financial stability, but high production costs and competition can affect profitability.” |

● Generate consistent revenue through a fixed 6% transaction commission, minimizing financial risk. As Intermediary 5 stated, “Our revenue is consistent because we earn a fixed 6% commission on transactions.” ● Profitability is closely tied to product quantity and sales volume. |

● Benefit from economic stability through local sourcing, reducing the impact of external market changes. ● Profitability is influenced by demand, sales volume, and consumer price sensitivity. ● Control spoilage and storage costs to maintain margins. ● As Retailer 7 remarked, “profitability depends on product demand and its price, as consumer sensitivity to price fluctuations is high.” |

| Social Sustainability | ● Supports job creation within communities, mainly providing opportunities for women to participate in the food system. ● Improves market access for small-scale farmers. Farmer 9 noted, “The short food supply chain has enabled job creation, especially for women, and improved market access for small-scale farmers.” ● Promotes community self-sufficiency by reducing reliance on imports and fostering local economic growth. |

● Generates job opportunities and strengthens the local economy by creating opportunities for different sectors to participate, such as transportation, agricultural supplies, machinery, and packaging. As Intermediary 5 stated, “Our operations create opportunities across sectors like transportation and packaging, stimulating local economic participation.” |

● Empowers consumers by offering a variety of products, enabling them to make choices aligned with their needs and financial capabilities. ● strengthens social ties as consumers increasingly support local products, contributing to community engagement and local loyalty. Retailer 7 explained, “Offering a variety of products allows consumers to make choices based on their needs, which promotes engagement and supports local communities.” |

| Dimension | Farmer | Intermediary | Retailer |

| Impact of the Pandemic and Political Conditions | ● Faced challenges in transporting labor, products, and marketing due to pandemic movement restrictions. ● Struggled with shortages of inputs like fertilizers and pesticides, leading to crop losses from delayed work permits. As Farmer 2 mentioned, “Restrictions imposed during the pandemic made it difficult to obtain production inputs (fertilizers and pesticides) and led to crop losses due to delayed permits.” ● Political conditions increased input costs and affected product prices due to market fluctuations and limited export opportunities. |

● Experienced reduced working hours and restrictions on market operations during the pandemic, affecting product handling and transportation. ● Political conditions, such as decreased purchasing power and restricted exports, caused a surplus in local markets, increasing competition and price volatility, which impacted profitability. Intermediary 2 stated, “The decline in purchasing power internally and externally and export difficulties led to a surplus of products, which has affected product prices and profitability.” |

● Encountered issues with product availability, transportation challenges, and government-imposed price caps on some crops during the pandemic. Retailer 1 mentioned, “The pandemic has affected the availability of products, and the government set price caps on some crops.” ● Political factors have led to fluctuations in import-export conditions and consumer purchasing power, resulting in inconsistent demand and price sensitivity. |

| Challenges in Supply Chain Interactions | ● Face financial difficulties due to delayed payments from intermediaries and retailers, affecting cash flow and reinvestment capacity. ● Have limited control over product pricing, often set by intermediaries. As Farmer 5 stated, “Delayed payments from intermediaries and limited control over pricing create financial difficulties.” ● Dependence on intermediaries constrains market access. ● Highlight logistical challenges at central markets, such as the lack of air-conditioned halls and shelters. |

● Provide financial support to farmers in exchange for exclusive marketing rights, but production issues can disrupt payment schedules and reduce profitability. As Intermediary 2 explained, “Providing financial support to farmers for exclusive marketing rights can impact our payment schedules and profitability if production issues occur.” ● Face difficulties collecting deferred payments from retailers. ● Encounter instances where retailers bypass intermediaries to deal directly with farmers. |

● Struggle with pricing control by intermediaries, limiting their ability to offer competitive prices to consumers. Retailer 6 noted, “Intermediaries’ control over prices makes it hard to offer competitive prices to consumers.” ● Experience product monopolization during high-demand periods, which allows intermediaries to increase prices. |

| Opportunities for Improvement | ● Increase reliance on local agricultural inputs to reduce import dependency, stabilizing costs and availability. ● Expand crop diversity to reduce market saturation and build resilience to seasonal fluctuations. ● Advocate for government agricultural guidance to manage surplus production and minimize waste. ● As Farmer 3 mentioned, “Increasing reliance on local production inputs and receiving government agricultural guidance can help stabilize costs and manage surplus production.” |

● Develop better storage facilities to handle surplus production and maintain supply during off-peak seasons. Intermediary 7 stated, “Developing better storage facilities can help handle surplus production and maintain supply during off-peak seasons.” ● Implement agricultural plans to align production with market demands, reducing waste and market saturation. ● Encourage consumer support for local products to stabilize demand and create consistent revenue streams. |

● Support local farmers in boosting food security and reducing reliance on imported goods. ● Promote waste reduction and operational cost savings through efficient inventory management and collaborations with local producers. As Retailer 4 explained, “Supporting local products and promoting practices to reduce waste can strengthen local markets and boost food security.” ● Raise consumer awareness about the benefits of buying local to strengthen loyalty and local markets. |

| Dimension | Farmer | Intermediary | Retailer |

| Anticipated Changes in Jordan’s Fresh Products Supply Chain | ● Rising costs for inputs like labor and fertilizers are expected to strain production budgets. ● Climate change is anticipated to impact crop yields, increasing adaptation costs. ● Weak local purchasing power may push farmers to focus on export markets. As Farmer 1 mentioned, “Increasing costs for inputs such as fertilizers and the growing impact of climate change on production, coupled with weak local purchasing power, are driving us to focus more on export markets.” |

● Increased costs and declining local purchasing power are expected to affect demand for fresh products, affecting profitability. ● Anticipate greater crop variety and increased production due to agricultural development, which enhances self-sufficiency. Intermediary 6 mentioned, “Agricultural development will lead to the availability of new varieties, an increase in production quantities, and the achievement of self-sufficiency.” |

● Expect prices to fluctuate due to surrounding conditions, impacting consumer purchasing behavior. ● Anticipate an increase in the variety and quantity of locally grown crops, reducing import dependency and enhancing self-sufficiency. As Retailer 8 mentioned, “The quantity and diversity of local production will increase, reducing reliance on imported products and enhancing self-sufficiency.” ● Foresee challenges from climate and water availability but believe expanding local agriculture will stabilize supply. |

| Adaptation Strategies for Future Resilience | ● Expand into export markets and diversify crop varieties to meet local and international demand. ● Explore climate-resilient crops with lower water requirements and shorter growth cycles. ● Convert surplus production into processed goods to reduce waste and create alternative revenue streams. As Farmer 4 stated, “Converting surplus production into food industries.” ● Seek government agricultural guidance to align production with market needs better and enhance efficiency. |

● Increase stockpiling and storage capacity to ensure the availability of out-of-season products and stabilize prices during demand spikes. As Intermediary 2 mentioned, “Increase stockpiling capacity to increase the availability of out-of-season products at a reasonable price.” ● Improve market coordination to reduce waste and support price stability. ● Encourage farmers to cultivate high-demand, low-availability crop varieties. |

● Strengthen relationships with local farmers to ensure consistent supply and price stability. ● Develop efficient marketing and distribution strategies to deliver fresh, local produce more efficiently to consumers. ● Expand product offerings to include processed goods, diversifying consumer options and revenue streams. As Retailer 7 stated, “Expanding operations and adding other products in addition to vegetables and fruits.” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).