1. Introduction

Chlorination roasting is a pyrometallurgical process in which metal-containing compounds are converted into their corresponding chlorides in the presence of chlorinating agents. The process relies on differences in the Gibbs free energy of formation and the volatility of metal chlorides, which enables selective separation of target metals even in complex mineral systems. Historically, chlorination roasting was first applied in the extraction of silver and copper, and later extended to magnesium, tin, tungsten, rare earth, and nickel ores. In recent years, it has gained renewed interest for the treatment of metallurgical and electronic wastes, where it serves as an effective route for recovering valuable metals from secondary resources [

1].

Depending on the operating temperature, chlorination roasting can be classified as low-temperature, medium-temperature, and high-temperature roasting. Low-temperature chlorination roasting (below 320–400 °C) commonly employs chlorinating agents such as NH

4Cl or mixtures of NaCl and NH

4Cl [

2,

3,

4]. In this temperature range, chlorination proceeds through the formation of intermediate chloro-complexes, which subsequently decompose into stable metal chlorides. This approach requires relatively simple equipment and low energy input, making it suitable for oxide and sulfide raw materials of moderate metal content.

Medium-temperature chlorination roasting (400–800 °C) typically uses solid chlorides such as NaCl, CaCl

2, KCl, and MgCl

2. Under these conditions, the metal chlorides formed remain in the condensed state, enabling their selective dissolution during subsequent hydrometallurgical processing steps. This method is widely applied for the extraction of metals such as nickel, cobalt, lithium, and rare earth elements from ores and industrial wastes [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

High-temperature chlorination roasting (above 800 °C) leads to the formation of volatile metal chlorides that can be separated via evaporation and condensation. This approach is particularly applicable to metals such as zinc, copper, silver, and gold, as well as complex polymetallic residues [

9,

10,

11].

When lead in waste materials is present in the form of lead sulfate (PbSO

4), its extraction is typically carried out in chloride media, since PbSO

4 is poorly soluble and chemically stable in many reactive environments [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. Our previous work [

22] demonstrated that direct chloride leaching of lead cake using a solution containing 250 g/L NaCl and 1 M HCl achieved high dissolution degrees for Pb (96.79 %) and Ag (84.55 %). However, the insoluble residue still contained 1.57 % Pb, which exceeds typical environmental regulatory thresholds and therefore classifies the residue as hazardous waste. This indicates that direct leaching alone is insufficient to achieve complete lead removal.

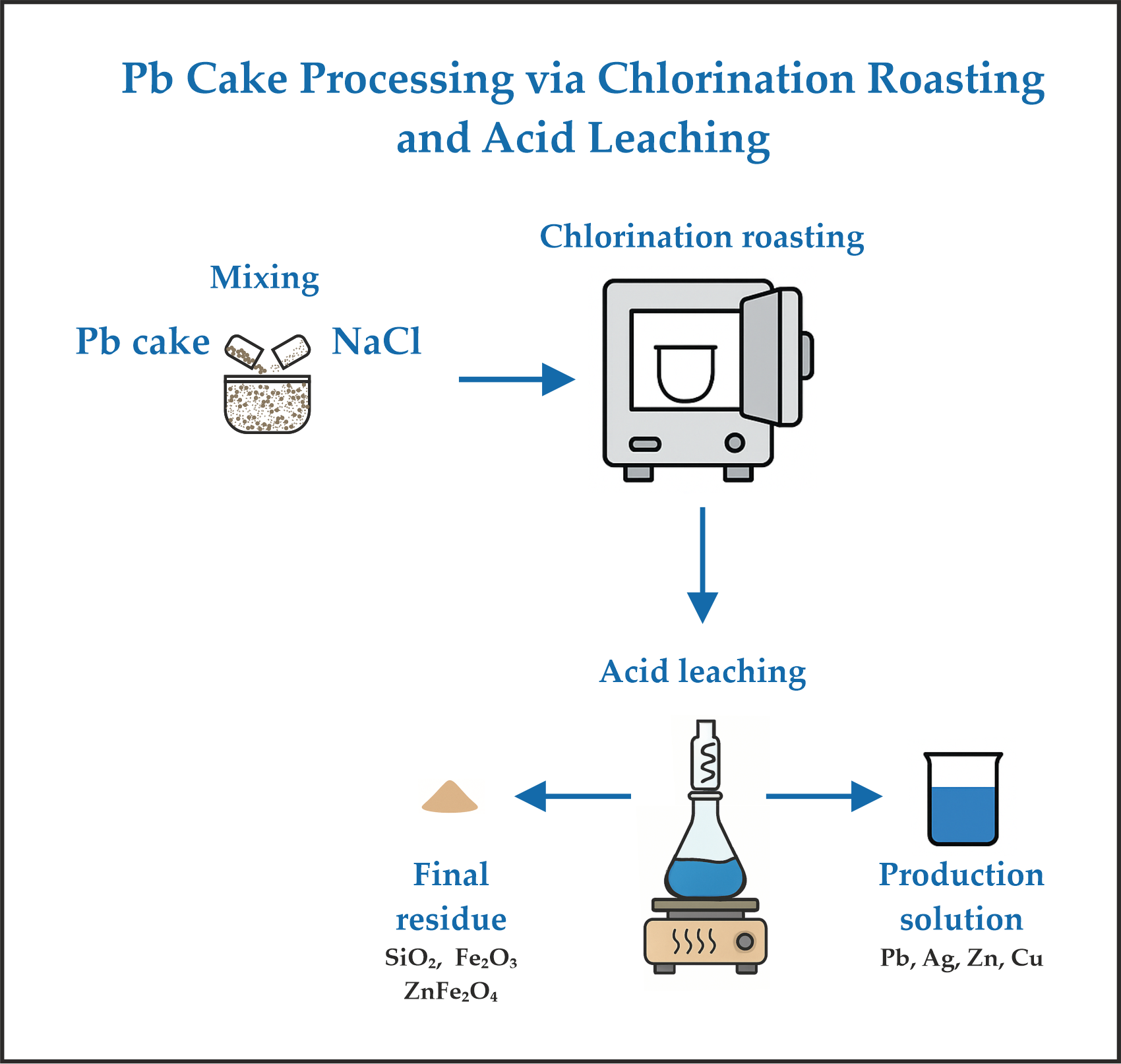

To overcome this limitation, additional thermal activation is required to convert PbSO4 into more soluble chloride phases prior to leaching. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to investigate the possibility of enhancing the extraction of lead and silver from lead cake through chlorination roasting followed by hydrometallurgical leaching, with the objective of reducing the Pb content in the final residue to levels below the hazardous waste classification threshold.

2. Materials and Methods

The initial lead cake was obtained as a result of high-acidity and high-temperature sulfuric acid leaching of zinc ferrite residue [

22]. The chemical composition of this material was determined by Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy (ICP-OES) using a Prodigy spectrometer (Teledyne Leeman Labs, USA). The results are summarized in

Table 1.

The XRD analysis [

22] confirmed that the lead cake consists of anglesite (PbSO

4) as the dominant phase, accompanied by bassanite (CaSO

4·0.5H

2O), franklinite (ZnFe

2O

4), hematite (Fe

2O

3), and a minor amount of sphalerite (ZnS).

Before the experiments, NaCl was dried at 105 °C for 12 h to remove residual moisture and ensure reagent stability. After drying, the NaCl and the lead cake were thoroughly mixed in a specified mass ratio and ground in an agate mortar to obtain a homogeneous fine mixture suitable for subsequent processing.

Chlorination roasting of the lead cake with NaCl was carried out in alumina crucibles, which are chemically inert and resistant to high temperatures. The experiments were conducted at various roasting temperatures using a muffle furnace (model FHP-05 – Witeg, Germany). Upon completion of the thermal treatment, the crucibles were removed from the furnace and allowed to cool to room temperature. The resulting roasted products were then ground and subjected to the leaching stage.

The leaching experiments were carried out in a vessel fitted with a reflux condenser and placed in a thermostatically controlled water bath, with continuous magnetic stirring to ensure homogeneous suspension of the solids. Upon completion of the experiments, the resulting pulp was rapidly filtered, and the insoluble residue was dried at 353 K for 24 h and subsequently weighed using an analytical balance KERN, model ABJ 320-4NM. The concentrations of the target metals in the insoluble residues were determined by ICP-OES. The extraction degrees of the target metals were calculated based on the chemical composition of the insoluble residues remaining after the leaching process.

The phase composition of the insoluble residues was determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Philips PW 1050 diffractometer (Philips Analytical, Eindhoven, Netherlands) equipped with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å), operating at 40 kV and 30 mA, with data collected over a 2θ range of 5° to 90°.

The morphology and phase composition of the insoluble residues obtained after the combined process were examined using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Oberkochen, Germany, coupled with Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS, Oxford Instruments, Oxford United Kingdom).

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Thermodynamic Assessment

Thermodynamic evaluation was carried out in order to assess the feasibility of converting lead sulfate (PbSO

4) into lead chloride (PbCl

2) during chlorination roasting. The standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG°) was calculated as a function of temperature for the following reactions:

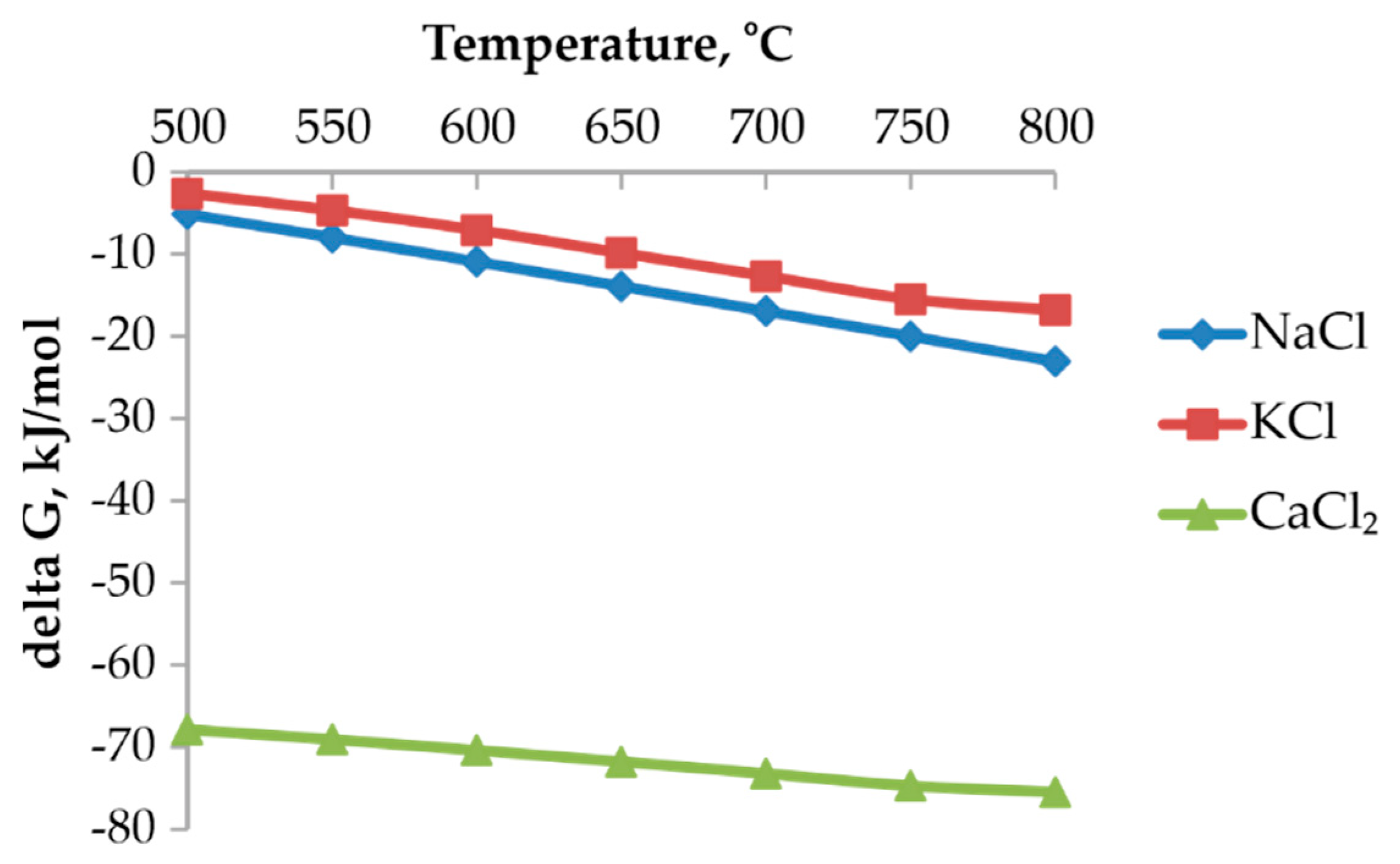

The calculated ΔG° values for these reactions as a function of temperature are presented in

Figure 1. The results show that ΔG° is negative across the investigated temperature range, indicating that the conversion of PbSO

4 to PbCl

2 is thermodynamically favorable. Among the chloride reagents considered, NaCl was selected for use in experimental work due to its low cost, wide availability, and ease of handling.

The formation of PbCl2 is particularly advantageous for subsequent hydrometallurgical processing because PbCl2 exhibits substantially higher solubility in chloride-containing acidic solutions compared to PbSO4. Therefore, the thermodynamic analysis confirms that chlorination roasting is an effective activation step that facilitates the dissolution of lead during the leaching stage.

3.2. Chlorination Roasting – Aqueous Leaching

Chlorination roasting of the lead cake was performed at three temperatures (500 °C, 600 °C, and 700 °C) and at lead cake-to-NaCl mass ratios of 1:1, 1:2, and 1:3, with roasting durations of 1 h and 2 h. Following roasting, the roasted material was subjected to aqueous leaching at 90 °C for 1 h at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:100, under continuous stirring. The effects of NaCl dosage, roasting temperature, and roasting time on the extraction degree of lead and silver were evaluated.

3.2.1. Effect of Lead Cake-to-NaCl Mass Ratio and Roasting Temperature

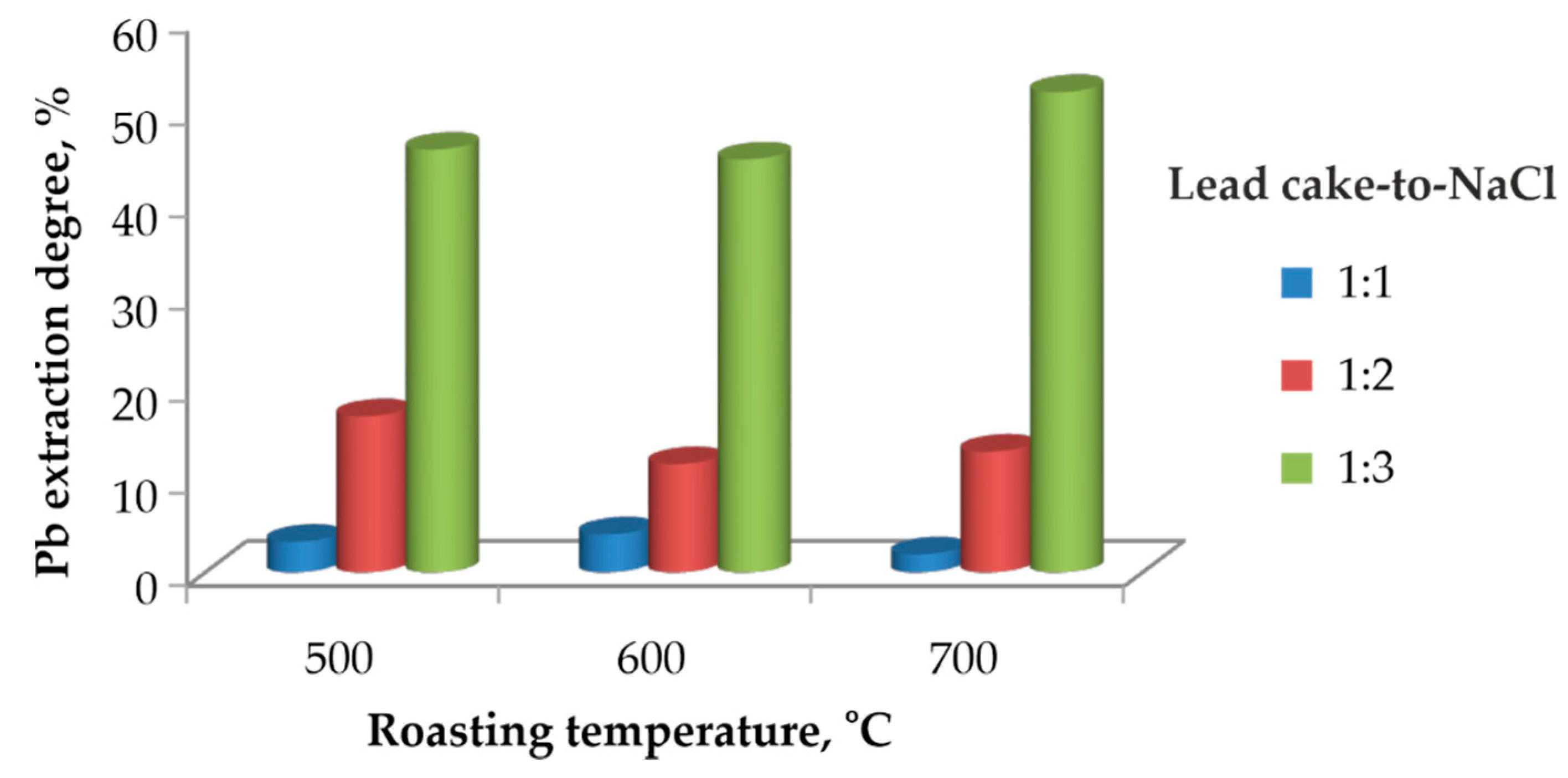

The influence of the lead cake-to-NaCl mass ratio on the extraction degree of lead at different chlorination roasting temperatures is presented in

Figure 2.

All experiments were carried out at a roasting duration of two hours. It is clearly observed that increasing the amount of NaCl results in a higher lead extraction degree. At a ratio of 1:1, the extraction degree remains below 10 % at all temperatures, indicating insufficient chlorination and incomplete conversion of PbSO4 to PbCl2. Increasing the ratio to 1:2 results in moderate improvement, with extraction degrees of approximately 10–20 %.

The highest extraction degree is achieved at a ratio of 1:3, regardless of the roasting temperature. In this case, lead extraction reaches nearly 50 % at 500 °C and 600 °C, and around 55 % at 700 °C. This demonstrates that providing a sufficient amount of chloride is essential for the effective conversion of PbSO4 to PbCl2.

3.2.2. Effect of Roasting Duration

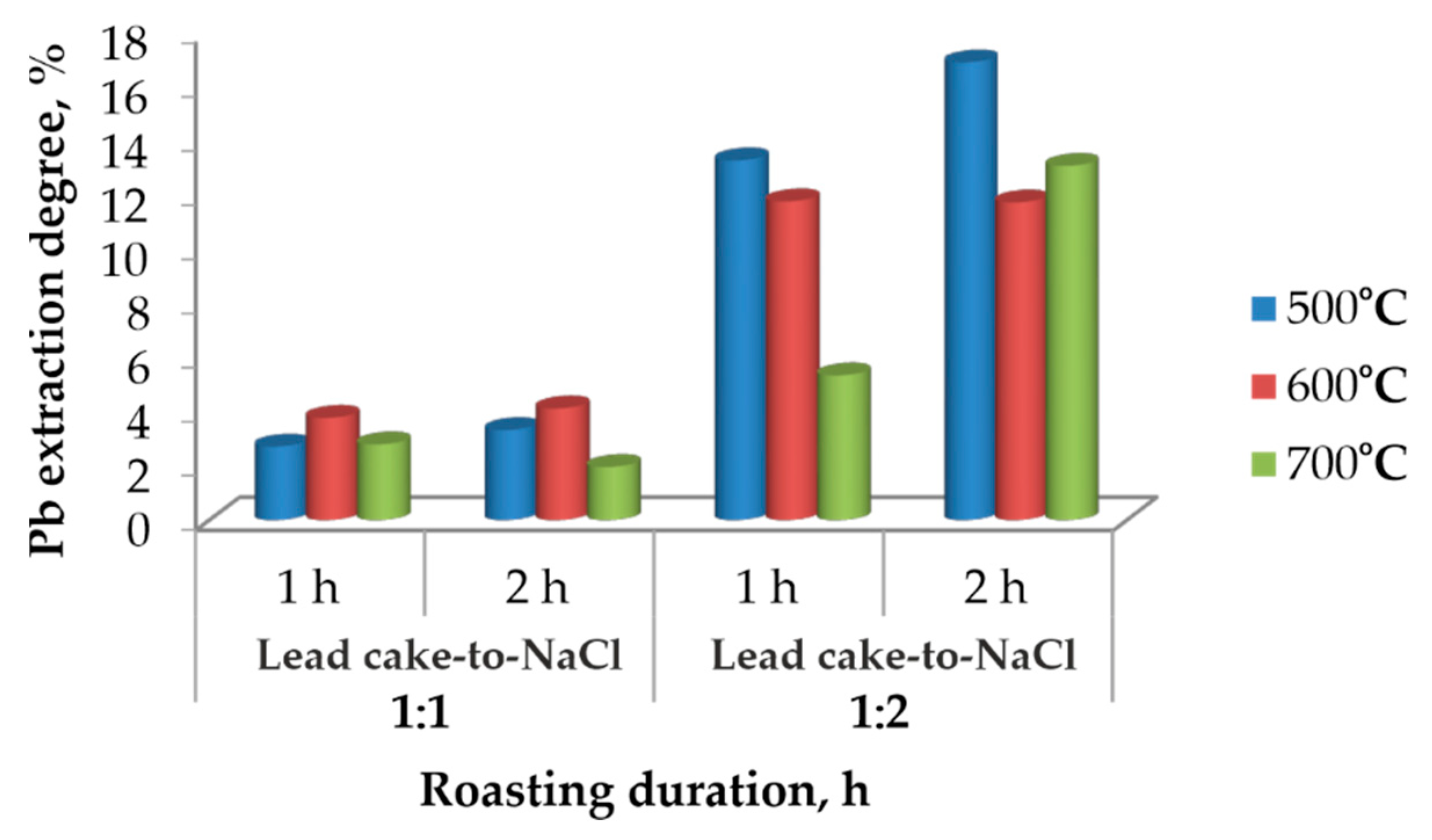

The effect of the roasting duration at different temperatures and lead cake-to-NaCl ratios was examined, and the results are presented in

Figure 3. The figure illustrates the effect of roasting temperature, the lead cake-to-NaCl ratio, and roasting duration on the extraction degree of lead. At a mass ratio of 1:1, the extraction degree remains low for both 1 h and 2 h of roasting, regardless of temperature. This indicates that when the amount of chloride is insufficient, the conversion of PbSO

4 to PbCl

2 is incomplete and the chlorination process proceeds to a limited extent.

When the mass ratio is increased to 1:2, a significant increase in lead extraction is observed. The highest extraction values are obtained at 600 °C, suggesting that this temperature is favorable for the chlorination reactions and for the formation of PbCl2 in a form that can be effectively dissolved during the subsequent aqueous leaching step. At 500 °C, improved extraction is also observed, although to a lesser extent, indicating slower reaction kinetics at lower temperature.

Notably, at 700 °C, the extraction degree decreases compared to 600 °C. This may be attributed to partial sintering and densification of the solid matrix, which reduces the reactive surface area, as well as the possible onset of PbCl2 volatilization. Increasing the roasting duration from 1 h to 2 h does not substantially improve extraction, suggesting that the chlorination reactions approach equilibrium within the first hour.

The chemical composition of the residues obtained after aqueous leaching of the roasted material (roasted at a lead cake-to-NaCl mass ratio of 1:3 and a roasting duration of 2 h) was determined by ICP-OES analysis. The results are presented in

Table 2.

As seen from the table, the three insoluble residues obtained after aqueous leaching are characterized by high residual Pb and Ag contents (approximately 17–20 % Pb and 0.04-0.05 % Ag), indicating that lead and silver were not fully extracted. This is most likely attributed to the high solid-to-liquid ratio (1:100) used during aqueous leaching, which leads to a significant reduction in the concentration of chloride ions in solution, limiting the dissolution of the formed PbCl2 and AgCl.

To verify this assumption, an additional experiment was carried out in which the material was roasted with NaCl at 500 °C and a lead cake-to-NaCl mass ratio of 1:3, followed by acid leaching with 1 M HCl at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 and temperature of 90oC. The resulting insoluble residue (Sample 4) contained only 0.96 % Pb and 0.1 % Ag, clearly demonstrating that acid leaching at a lower solid-to-liquid ratio is significantly more effective for dissolving PbCl2 and AgCl.

Furthermore, the behavior of silver generally follows that of lead. During chlorination roasting, Ag is converted predominantly into AgCl, which exhibits low solubility in aqueous chloride media, leading to its enrichment in the solid residue. However, in the acid leaching step, the significant decrease in Ag content indicates dissolution of AgCl and its transfer into solution, alongside Pb extraction.

3.3. XRD Analysis

The insoluble residues obtained after leaching of the roasted materials (

Table 2) were analyzed by X-ray diffraction, and the corresponding diffraction patterns are shown in

Figure 4.

Comparison with the initial lead cake indicates that chlorination roasting with NaCl leads to the conversion of PbSO4 into chloride-containing phases, resulting in the formation of PbCl2 and Pb(OH)Cl, as well as partial formation of Pb2(SO4)O. The obtained results showed that at temperature of 500 °C, chlorination is initiated, but a considerable amount of PbSO4 remains unconverted; at 600 °C, PbCl2 and Pb(OH)Cl are the dominant phases and the conversion is more complete; while at 700 °C, PbCl2 was predominant phase, but partial volatilization occurred, leading to losses of lead.

During washing of the roasted product, the formation of needle-shaped PbCl

2 crystals was observed (

Figure 5), confirming the chlorination pathway. Regardless of the roasting conditions, ZnFe

2O

4, Fe

2O

3, and SiO

2 remain stable and constitute the main matrix of the solid residue.

In contrast, acid leaching with 1 M HCl results in complete dissolution of Pb and Ag-bearing phases, whether they are sulfate-, chloride-, or hydroxychloride-based.

After this treatment, the residue consists primarily of SiO2, ZnFe2O4, and Fe2O3, which are chemically stable under the applied conditions. Therefore, chlorination roasting with NaCl at 500–600 °C is identified as optimal for converting PbSO4 into easily leachable chloride phases, whereas roasting at 700 °C leads to Pb loss due to the volatility of PbCl2.

3.4. SEM/EDS Analysis

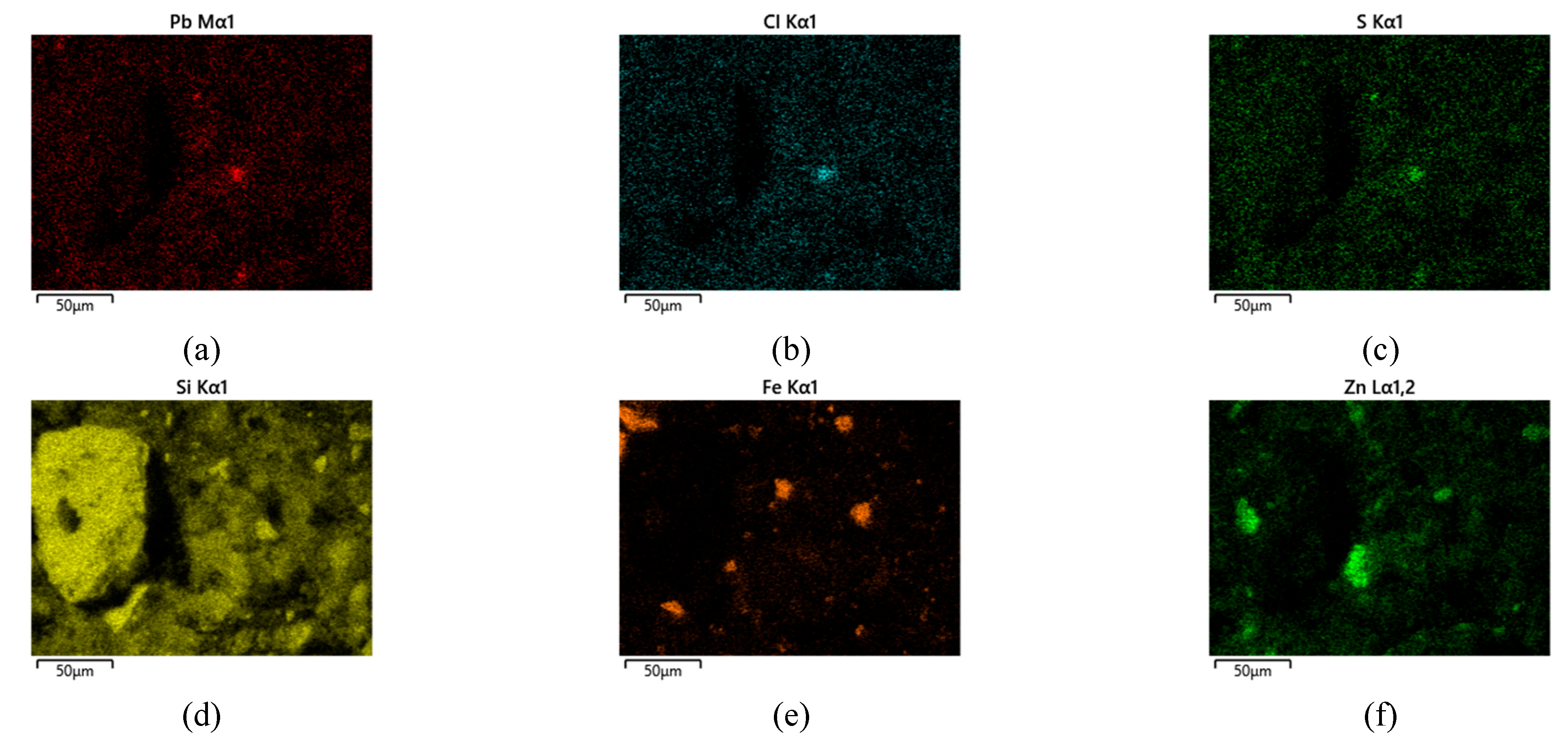

The microstructural and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) observations complement the XRD results and provide information on the spatial distribution of the phases in the solid residues after roasting and leaching. Two samples were examined by SEM/EDS:

In Sample 1, a heterogeneous microstructure is observed, consisting of bright Pb-enriched agglomerates and darker regions dominated by Zn- and Fe-containing phases (

Figure 6).

In addition to point EDS measurements, elemental distribution maps were obtained to visualize the spatial localization of Pb-bearing phases within the solid matrix. The elemental maps for Sample 1 (

Figure 7) show heterogeneous distribution of Pb, Cl, and S, occurring as localized enriched regions associated with PbCl

2, PbSO

4 and mixed oxychlorosulfate phases. These Pb-rich domains are embedded within a continuous Zn–Fe–Si matrix corresponding to ZnFe

2O

4, Fe

2O

3 and SiO

2. The presence of Pb-, Cl-, and S-rich regions confirms incomplete removal of Pb-bearing phases during aqueous extraction.

EDS spectra 18, 21, 23, and 24 (

Table 3) show high Pb contents (20–60 %), along with variable Cl and S levels, confirming the presence of PbCl

2, Pb(OH)Cl, PbSO

4, and Pb

2(SO

4)O. Spectrum 21 (59.3 %Pb, 7.6 %S) is characteristic of residual sulfate phases, while spectrum 18 (25.5 %Pb, 3.7 %Cl) indicates chlorinated phases. Spectrum 23 reflects partial coverage of ZnFe

2O

4 grains by Pb-bearing phases, which suggests incomplete removal of lead during aqueous leaching. In contrast, spectra 19 and 22 show negligible Pb and are dominated by ZnFe

2O

4, Fe

2O

3, and SiO

2, forming the stable matrix of the solid residue.

The microstructure of Sample 4 (500 °C, acid leaching) appears more porous and less compact, consistent with the removal of Pb-containing phases (

Figure 8).

The elemental maps for Sample 4 (

Figure 9) show the disappearance of Pb-, Cl-, and S-enriched regions, while the Zn–Fe–Si matrix remains structurally preserved, confirming the complete dissolution of Pb-bearing phases during acid leaching with 1 M HCl. These observations are in full agreement with the XRD and ICP-OES results.

In spectrum 25 (

Table 4), Pb is present at only 5.5 %, while in spectra 27, 28, 30, and 32, Pb levels are below 1 %, confirming complete dissolution of Pb-bearing phases during acid leaching. High Si, Zn, and Fe contents reflect the presence of quartz, zinc ferrite, and hematite. Spectrum 28 shows Zn–Al enrichment, characteristic of Al-substituted ferrite, known for high acid resistance.

Therefore, the SEM/EDS analysis confirms the phase evolution sequence established by the XRD results: aqueous leaching removes Pb only partially, whereas acid leaching leads to its complete removal, while the stable Zn–Fe–Si matrix remains preserved.

The EDS analyses of both Sample 1 and Sample 4 show that no silver-containing phases are detected. Silver is present at very low concentrations, and we believe it can only be identified by chemical methods, for example by ICP analysis.

3.5. Chlorination Roasting – Acid Leaching

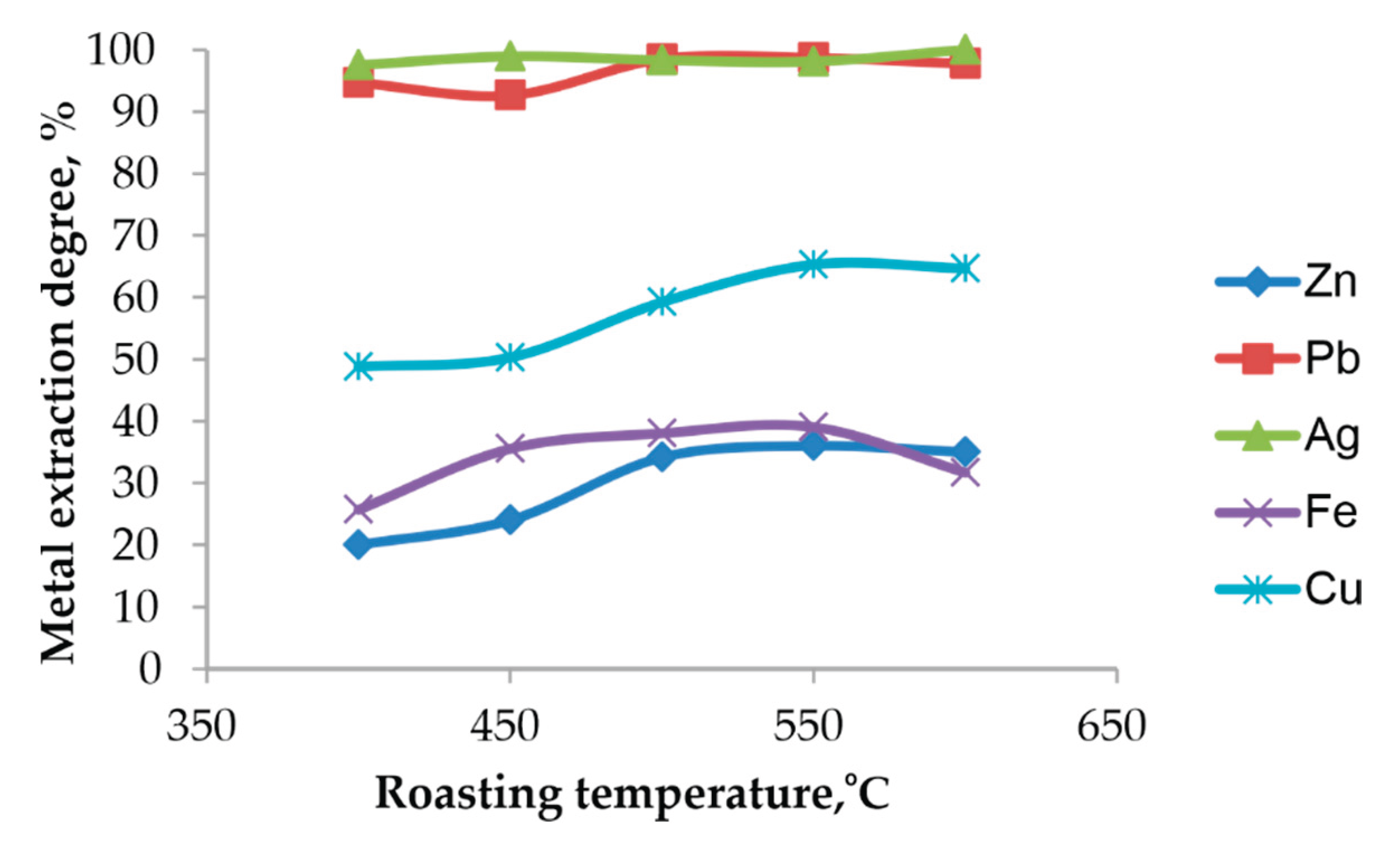

3.5.1. Effect of Roasting Temperature on the Extraction Degree of Metals with 1 M HCl

It is necessary to re-evaluate the effect of roasting temperature because it plays different roles during the various stages of hydrometallurgical leaching. During chlorination roasting, temperature controls the extent of conversion of PbSO4 to PbCl2 and related chlorinated phases. However, during the subsequent acid leaching stage, roasting temperature influences the solubility and stability of the formed Pb-bearing phases. Therefore, the optimal roasting temperature for maximizing chlorination does not necessarily correspond to the optimal temperature for achieving complete dissolution of lead. For this reason, the roasting temperature effect must be assessed independently as well as in the acid leaching stage.

The influence of the chlorination roasting temperature on the extraction degree of metals during subsequent acid leaching with 1 M HCl at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 and temperature of 90

oC is presented in

Figure 10.

At all roasting temperatures between 400 and 600 °C, the dissolution of Pb and Ag in 1 M HCl exceeds 97 %, which reflects the high solubility of the chlorinated phases produced during roasting, including PbSO4, PbCl2, Pb(OH)Cl, Pb2(SO4)O and AgCl, in chloride-containing acidic solutions. The dissolution behavior of Ag parallels that of Pb due to the formation of highly soluble Ag–Cl complexes in chloride solutions (primarily AgCl2− and AgCl32−).

By comparison, the extraction of Zn and Fe remains significantly lower and varies with roasting temperature, which is consistent with the resistance of ZnFe2O4 and Fe2O3 to dissolution in acidic chloride solutions. Cu shows a moderate increase in extraction degree with temperature, likely reflecting changes in the reactivity of Cu-bearing phases.

Table 5 presents the chemical compositions of the insoluble residues obtained after chlorination roasting followed by acid leaching.

The data show that the residual amounts of lead are very low at all roasting temperatures, with the minimum value of 0.9 % Pb at 550 °C. Silver is also present only in trace amounts (0.001–0.003 %), confirming its almost complete extraction. The concentrations of Zn, Fe and Cu remain essentially constant, reflecting the stability of the ferrite matrix and indicating that these elements do not dissolve significantly under the applied leaching conditions.

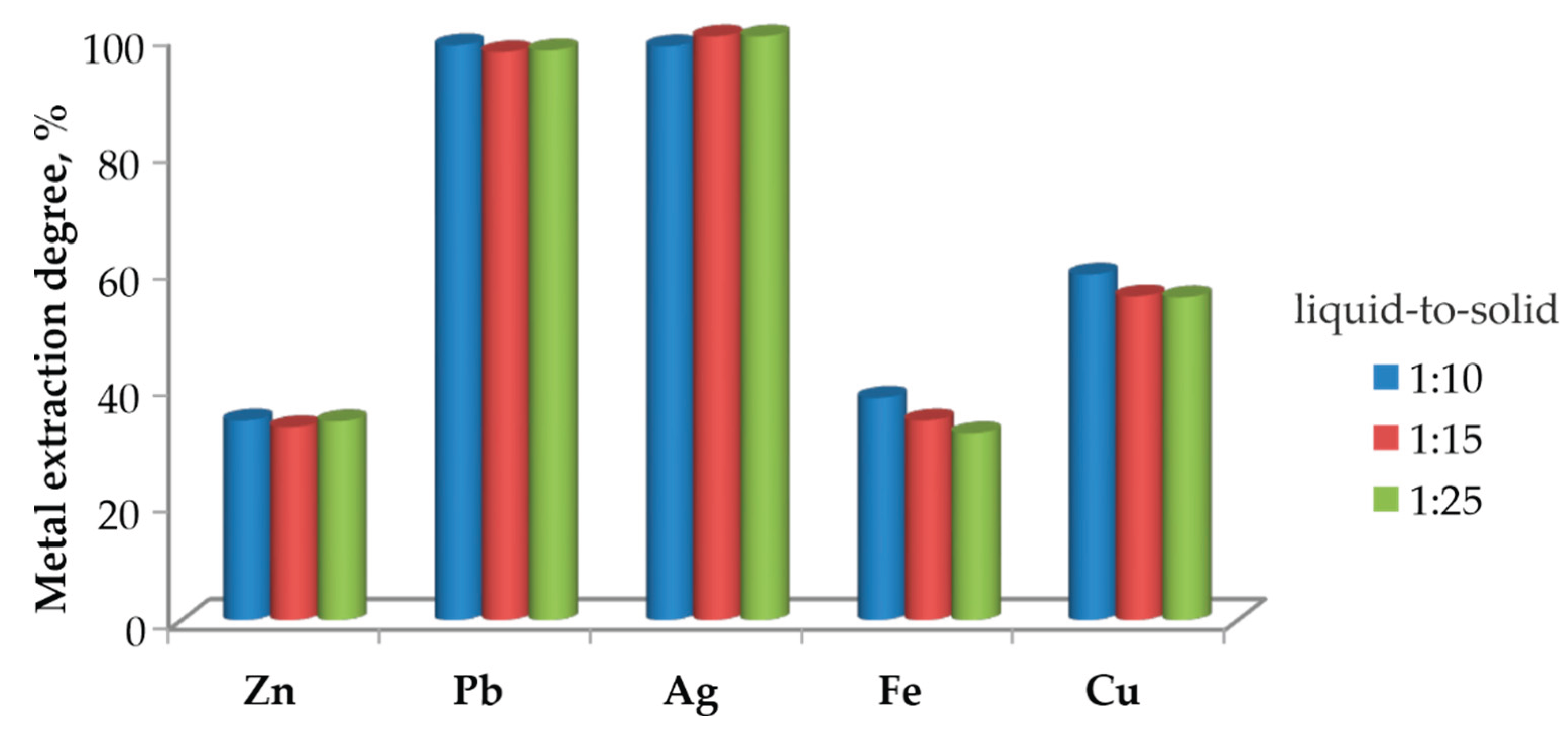

3.5.2. Effect of Pulp Density (Solid-to-Liquid Ratio) at 500 °C

Figure 11 illustrates the effect of pulp density on metal extraction from the roasted at 500 °C material, followed by leaching with 1 M HCl.

It is evident that changing the solid-to-liquid ratio from 1:10 to 1:25 does not significantly affect the extraction of Pb and Ag; in all cases, the extraction degree remains close to 100 %. This confirms the high solubility of Pb chloride phases and the easy dissolution of silver under the applied conditions.

In contrast, Zn and Fe display much lower extraction degrees, while Cu extraction increases at lower pulp densities, with the ratio 1:25 providing the highest dissolution efficiency.

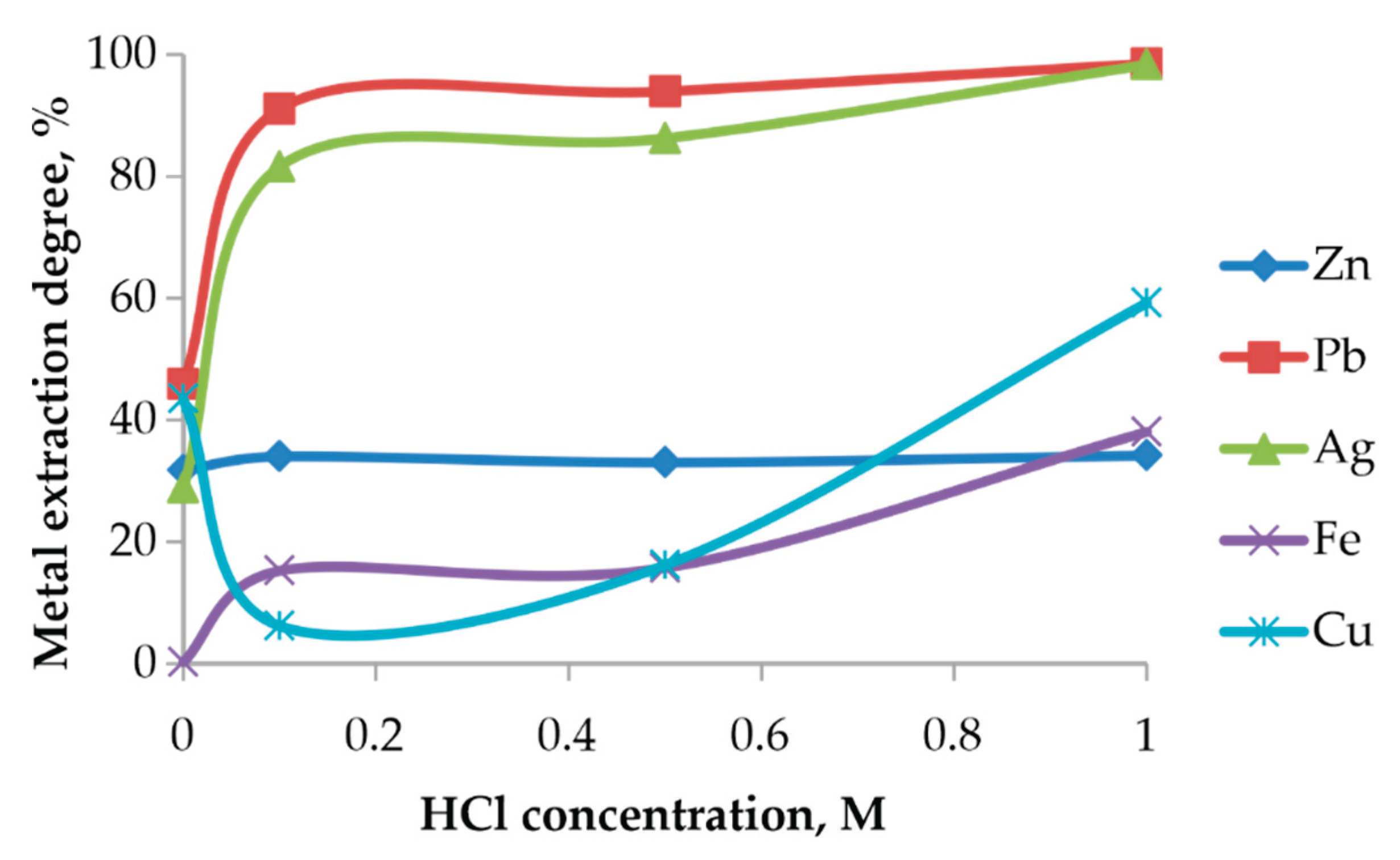

3.5.3. Effect of Acid Concentration

The increase in HCl concentration has a pronounced effect on the dissolution of Pb and Ag, whereas Zn, Fe, and Cu exhibit different behavior depending on the stability of their host phases (

Figure 12).

At low HCl concentrations (0–0.1 M), a sharp increase in Pb and Ag extraction is observed, reflecting the rapid formation of soluble chloride complexes such as PbCl42−, PbCl3−, and AgCl2−. The extraction degrees exceed 90–95 %, indicating that chlorination roasting successfully converted Pb-bearing phases into chloride forms that dissolve readily in chloride media.

In contrast, Zn extraction remains nearly constant (~30 %), consistent with the stability of ZnFe2O4, confirming that Zn remains locked within the ferrite matrix. Fe dissolution increases only at HCl concentrations above 0.6 M, when the protective oxide layers begin to destabilize.

During aqueous leaching, copper undergoes partial dissolution. In the range of 0.1–0.5 M HCl, a reduction in the extraction efficiency is observed, which is attributed to the formation of sparingly soluble phases. However, upon increasing the acid concentration to 1 M HCl, copper enters the solution due to the formation of stable chloro-complex species.

3.6. Comparison Between Chlorination Roasting + Acid Leaching and Direct Chloride Leaching

The developed combined process enables efficient and selective recovery of lead from lead cake and results in the formation of a stable residue with low residual Pb content. Chlorination roasting with NaCl at 500–550 °C ensures the activation of PbSO

4 and its conversion into soluble chloride forms, which are subsequently fully dissolved in 1 M HCl, while the ferrite–silica matrix remains unaffected. The process therefore demonstrates strong potential for integration into industrial flowsheets for the recycling of lead-containing residues. A comparison between the two examined routes – the combined chlorination roasting followed by acid leaching, and direct chloride leaching – clearly shows the advantage of the combined approach both in terms of metal extraction efficiency and the characteristics of the resulting solid residue. After chlorination roasting followed by leaching in 1 M HCl, the mass of the insoluble residue is reduced to 34.20 % of the initial material, whereas direct chloride leaching yields a residue corresponding to 45 % of the original mass (

Table 6). This indicates that the combined process facilitates a greater transfer of metal species into the solution phase, reflecting more complete activation and dissolution of the lead- and silver-bearing phases.

The most notable difference is the significantly lower Pb and Ag concentrations in the residue produced via chlorination roasting followed by acid leaching (0.90 % Pb and 0.0027 % Ag), compared to the residue obtained by direct chloride leaching (1.57 % Pb and 0.0160 % Ag).

In terms of metal extraction, the combined process again shows superior performance. Lead is extracted almost completely (98.68 %), and silver to 98.09 %, while the values for direct chloride leaching are 96.79 % and 84.55 %, respectively (

Table 7). This improvement results from the conversion of PbSO

4 into more soluble chloride phases during roasting, which are fully dissolved under acidic leaching conditions.

While Cu also shows improved extraction in the combined process, the extraction of Fe and Zn remains limited in both cases. This behavior is consistent with the persistence of the chemically stable zinc ferrite matrix (ZnFe2O4), which is resistant to dissolution in both chloride and acidic media. This interpretation is further supported by the XRD and SEM/EDS results, which confirm that after acid dissolution of the roasted material, the solid residue contains mainly ZnFe2O4, Fe2O3, and SiO2.

3.7. Assessment of the Leaching Toxicity of the Final Residue

The leaching behavior of the final solid residue was assessed using the European standard EN 12457-2 [

23], which specifies a compliance leaching test at a liquid-to-solid ratio of L/S = 10 L/kg under agitation for 24 h. After filtration, the eluate was analyzed for a set of regulated elements by ICP-OES, following the requirements of the Waste Acceptance Criteria (WAC) established in Council Decision 2003/33/EC [

24]. The measured concentrations were compared with the limit values for inert, non-hazardous and hazardous waste landfills as presented in

Table 8.

The results show that all analysed elements are well below the regulatory limits defined in the WAC. Lead, the key indicator metal, is leached at 0.12 mg/L, significantly lower than the inert waste limit of 0.5 mg/L. Zinc (0.08 mg/L) and copper (0.05 mg/L) are also far below their corresponding thresholds (4 mg/L and 2 mg/L, respectively).

All remaining regulated metals (As, Ba, Cd, Cr, Ni, Se, Hg, Mo, Sb) were below detection limits and therefore compliant with the most stringent WAC category.

These results confirm that the final residue exhibits very low metal mobility and meets the criteria for classification as inert waste, indicating minimal environmental risk upon disposal.

4. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the combined chlorination roasting–acid leaching process is a highly effective and environmentally advantageous method for recovering lead and silver from lead-bearing industrial residues. Chlorination roasting with NaCl at 500–600 °C enables the conversion of PbSO4 into easily soluble chloride phases such as PbCl2 and Pb(OH)Cl, while ZnFe2O4, Fe2O3, and SiO2 remain structurally stable and form the inert matrix of the final residue.

The subsequent leaching step plays a critical role in determining the efficiency of lead removal. Aqueous leaching at a high solid-to-liquid ratio (1:100) resulted in incomplete dissolution of lead, leaving 17–20 % Pb in the residue. In contrast, acid leaching with 1 M HCl at a solid-to-liquid ratio of 1:10 enabled nearly complete dissolution of Pb and Ag. reducing the Pb content in the final residue to as low as 0.90 % (at 550 °C).

A direct comparison with single-step chloride leaching shows that the two-step method provides both higher metal recoveries (Pb 98.68 %, Ag 98.09 %) and a lower final residue mass (34 % vs. 45 %). Additionally, the compliance leaching test (EN 12457-2) confirmed that the final residue meets the strict criteria for inert waste under EU Waste Acceptance Criteria.

Overall, the proposed combined method improves the efficiency of Pb and Ag extraction, reduces environmental risk, and provides a technically robust pathway for the sustainable treatment of lead-containing secondary materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization P.I. and B.L.; methodology P.I. and B.L.; software P.I., B.L., N.K.; validation P.I. and B.L.; formal analysis N.K.; investigation P.I., B.L., N.K.; resources P.I. and B.L.; data curation P.I. and B.L.; writing—original draft preparation P.I., B.L.; writing—review and editing P.I., B.L.; visualization P.I. and B.L.; supervision P.I. and B.L.; project administration P.I.; funding acquisition P.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by European Union Next Generation EU, through the National Recovery and Resilience Plan of the Republic of Bulgaria, project №BG-RRP-2.004-0002, “BiOrgaMCT”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not relevant.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting reported results have been included in the manuscript in the form of graphs.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the support from KCM - Bulgaria.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscope |

| EDS |

Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy |

| ICP-OES |

Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectroscopy |

| XRD |

X-ray diffraction |

| WAC |

Waste Acceptance Criteria |

References

- Fan, Z.-Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, R.-Y.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Zhang, T.-A.; Wang, X.-J.; Li, J.-D.; Zhao, X.-X.; Li, W.-J. Research and application mechanism of chlorination roasting for polymetallic minerals and waste. Miner. Eng. 2025, 232, 109493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zou, X.; Cheng, H.; et al. A novel ammonium chloride roasting approach for the high-efficiency co-sulfation of nickel, cobalt, and copper in polymetallic sulfide minerals. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2020, 51, 2769–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Song, J.; Hu, T.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.; Zou, F. Low-temperature chlorination-roasting–acid-leaching uranium process of uranium tailings: Comparison between microwave roasting and conventional roasting. Processes 2025, 13, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Yu, X.; Yang, G.; et al. Mechanistic insights into the chlorination volatilization of oxidized heavy metals via novel staggered chlorination roasting. Waste Dispos. Sustain. Energy 2025, 7, 151–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z. Chlorination roasting of laterite using salt chloride. Int. J. Miner. Process. 2016, 148, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Li, X.; Xiao, Y.; Yang, Y. Selective extraction of rare earth elements from NdFeB scrap by molten chlorides. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 2536–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, P.; Mu, W.; Sun, W.; et al. Efficient extraction of Ni, Cu and Co from mixed oxide–sulfide nickel concentrate by sodium chloride roasting: Behavior, mechanism and kinetics. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2024, 55, 1896–1909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Mu, W.; Wang, S.; Xin, H.; Shen, H.; Xu, Q.; Zhai, Y.; Luo, S. Synchronous extractions of nickel, copper, and cobalt by selective chlorinating roasting and water leaching to low-grade nickel–copper matte. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 195, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.-K.; Wang, Q.-M.; Guo, X.-Y.; Tian, Q.-H. Mechanism and kinetics for chlorination roasting of copper smelting slag. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 563–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wen, S.; Chen, Y.; et al. Process optimization and reaction mechanism of removing copper from an Fe-rich pyrite cinder using chlorination roasting. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2013, 20, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höber, L.; Witt, K.; Steinlechner, S. Selective chlorination and extraction of valuable metals from iron precipitation residues. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinadinovic, D.; Kamberovic, Z.; Sutic, A. Leaching kinetics of lead from lead(II) sulphate in aqueous calcium chloride and magnesium chloride solutions. Hydrometallurgy 1997, 47, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghavan, R.; Mohanan, P.K.; Swarnkar, S.R. Hydrometallurgical processing of lead-bearing materials for the recovery of lead and silver. Hydrometallurgy 2000, 58, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruşen, A.; Sunkar, A.S.; Topkaya, Y.A. Zinc and lead extraction from Çinkur leach residues by hydrometallurgical methods. Hydrometallurgy 2008, 93, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahmand, F.; Moradkhani, D.; Safarzadeh, M.S.; Rashchi, F. Brine leaching of lead-bearing zinc plant residues: Process optimization. Hydrometallurgy 2009, 95, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnajady, B.; Moghaddam, J.; Behnajady, M.A.; Rashchi, F. Optimizing lead leaching from zinc plant residues in NaCl–H2SO4–Ca(OH)2 media. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 3887–3894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Mu, W.; Shen, H.; Liu, S.; Zhai, Y. Leaching of lead from zinc leach residue in acidic CaCl2 solution. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2015, 22, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; et al. Efficient recycling of Pb from zinc leaching residues by hydrometallurgy. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 075505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silwamba, M.; Ito, M.; Hiroyoshi, N.; et al. Recovery of lead and zinc from zinc plant residues via dissolution–cementation in chloride media. Metals 2020, 10, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houshmand, A.R.; Azizi, A.; Bahri, Z. Recovery of lead from zinc production residue: Process optimization and kinetics. Geosyst. Eng. 2024, 27, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, T.; Gibas, K.; Borowski, K.; et al. Chloride leaching of silver and lead from residue after leaching of copper concentrates. Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process. 2017, 53, 893–907. [Google Scholar]

- Iliev, P.; Lucheva, B.; Kazakova, N.; Stefanova, V. Recovery of iron, silver and lead from zinc ferrite residue. Materials 2025, 18, 3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Committee for Standardization (CEN). EN 12457-2: Characterisation of Waste-Leaching-Compliance Test for Leaching of Granular Waste Materials and Sludges—Part 2: One Stage Batch Test at a Liquid to Solid Ratio of 10 L/kg for Materials with Particle Size below 4 mm; CEN: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

- European Council. Council Decision 2003/33/EC establishing criteria and procedures for the acceptance of waste at landfills. Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, L11, 27–49.

Figure 1.

Temperature influence on Gibbs free energy (ΔG).

Figure 1.

Temperature influence on Gibbs free energy (ΔG).

Figure 2.

Effect of chlorination roasting temperature and NaCl dosage on the lead extraction degree.

Figure 2.

Effect of chlorination roasting temperature and NaCl dosage on the lead extraction degree.

Figure 3.

Lead extraction degree as a function of roasting duration at different temperatures and lead cake-to-NaCl ratios.

Figure 3.

Lead extraction degree as a function of roasting duration at different temperatures and lead cake-to-NaCl ratios.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the initial lead cake and the roasted materials obtained under different roasting conditions.

Figure 4.

XRD patterns of the initial lead cake and the roasted materials obtained under different roasting conditions.

Figure 5.

Needle-shaped PbCl2 crystals formed during washing of the roasted product.

Figure 5.

Needle-shaped PbCl2 crystals formed during washing of the roasted product.

Figure 6.

SEM microstructure of Sample 1 (500 °C, aqueous leaching).

Figure 6.

SEM microstructure of Sample 1 (500 °C, aqueous leaching).

Figure 7.

EDS elemental mapping in Sample 1 (500 °C, aqueous leaching). (a) – Pb; (b) – Cl; (c) – S; (d) – Si; (e) – Fe; (f) – Zn

Figure 7.

EDS elemental mapping in Sample 1 (500 °C, aqueous leaching). (a) – Pb; (b) – Cl; (c) – S; (d) – Si; (e) – Fe; (f) – Zn

Figure 8.

SEM microstructure of Sample 4 (500 °C, acid leaching).

Figure 8.

SEM microstructure of Sample 4 (500 °C, acid leaching).

Figure 9.

EDS elemental mapping in Sample 4 (500 °C, acid leaching). (a) – Pb; (b) – Cl; (c) – S; (d) – Si; (e) – Fe; (f) - Zn.

Figure 9.

EDS elemental mapping in Sample 4 (500 °C, acid leaching). (a) – Pb; (b) – Cl; (c) – S; (d) – Si; (e) – Fe; (f) - Zn.

Figure 10.

Effect of chlorination roasting temperature on the extraction degree of metals during subsequent acid leaching with 1 M HCl.

Figure 10.

Effect of chlorination roasting temperature on the extraction degree of metals during subsequent acid leaching with 1 M HCl.

Figure 11.

Effect of pulp density on the extraction degree of metals.

Figure 11.

Effect of pulp density on the extraction degree of metals.

Figure 12.

Effect of HCl concentration on the extraction degree of metals.

Figure 12.

Effect of HCl concentration on the extraction degree of metals.

Table 1.

Main chemical composition of lead cake, wt. %.

Table 1.

Main chemical composition of lead cake, wt. %.

| Pb |

Ag |

Zn |

Cu |

Fe |

| 26.84 |

0.0554 |

1.13 |

0.17 |

7.98 |

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the residues obtained after aqueous and acid leaching of the roasted material.

Table 2.

Chemical composition of the residues obtained after aqueous and acid leaching of the roasted material.

| Sample No. |

Process |

T, °C |

Pb, wt. % |

Ag, wt. % |

Zn, wt. % |

Cu, wt. % |

Fe, wt. % |

| 1 |

Roasting – aqueous leaching |

500 |

19.39 |

0.0526 |

1.03 |

0.13 |

10.62 |

| 2 |

Roasting – aqueous leaching |

600 |

19.87 |

0.0458 |

0.99 |

0.14 |

10.67 |

| 3 |

Roasting – aqueous leaching |

700 |

17.28 |

0.0436 |

0.96 |

0.15 |

10.69 |

| 4 |

Roasting – acid leaching |

500 |

0.96 |

0.0100 |

1.76 |

0.22 |

8.78 |

Table 3.

EDS elemental composition (wt. %) of selected micro-areas in Sample 1.

Table 3.

EDS elemental composition (wt. %) of selected micro-areas in Sample 1.

| Element (wt. %) |

Sp.18 |

Sp.19 |

Sp.21 |

Sp.22 |

Sp.23 |

Sp.24 |

| Pb |

25.45 |

2.93 |

59.30 |

0.28 |

20.62 |

12.92 |

| Cl |

3.69 |

0.49 |

0.00 |

0.04 |

1.53 |

0.66 |

| S |

0.97 |

0.00 |

7.59 |

0.06 |

0.64 |

10.48 |

| O |

30.17 |

57.54 |

22.87 |

60.03 |

34.27 |

38.34 |

| Si |

11.69 |

38.35 |

1.08 |

39.33 |

11.95 |

11.31 |

| Fe |

12.71 |

0.63 |

8.85 |

0.09 |

11.62 |

7.83 |

| Zn |

5.58 |

0.07 |

0.32 |

0.17 |

10.91 |

3.11 |

| Cu |

3.21 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| Mn |

2.27 |

– |

– |

– |

1.91 |

1.12 |

| Al |

2.34 |

– |

– |

– |

5.42 |

1.74 |

| K |

0.77 |

– |

– |

– |

0.58 |

0.72 |

| Ca |

1.15 |

– |

– |

– |

0.56 |

11.79 |

Table 4.

EDS elemental composition (wt. %) of selected micro-areas in Sample 4.

Table 4.

EDS elemental composition (wt. %) of selected micro-areas in Sample 4.

| Element (wt. %) |

Sp.25 |

Sp.27 |

Sp.28 |

Sp.30 |

Sp.32 |

| Pb |

5.49 |

0.17 |

0.91 |

1.11 |

0.44 |

| Cl |

2.25 |

0.02 |

0.22 |

0.23 |

0.24 |

| S |

0.49 |

0.00 |

0.05 |

2.92 |

0.14 |

| O |

44.72 |

56.93 |

36.71 |

52.46 |

40.82 |

| Si |

27.69 |

39.79 |

4.86 |

28.93 |

15.43 |

| Fe |

3.58 |

0.24 |

3.43 |

4.53 |

3.61 |

| Zn |

6.69 |

1.90 |

28.40 |

5.66 |

19.91 |

| Al |

6.01 |

0.95 |

22.32 |

3.26 |

16.75 |

| Na |

2.22 |

– |

3.11 |

0.91 |

2.66 |

| K |

0.41 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

| Ca |

0.45 |

– |

– |

– |

– |

Table 5.

Chemical composition of the insoluble residues after roasting and acid leaching as a function of roasting temperature (wt. %).

Table 5.

Chemical composition of the insoluble residues after roasting and acid leaching as a function of roasting temperature (wt. %).

| Temperature ( °C) |

Pb |

Ag |

Zn |

Fe |

Cu |

| 400 |

3.13 |

0.0030 |

3.99 |

12.92 |

0.19 |

| 450 |

4.42 |

0.0013 |

3.56 |

11.48 |

0.19 |

| 500 |

1.01 |

0.0023 |

1.86 |

12.36 |

0.17 |

| 550 |

0.90 |

0.0027 |

4.46 |

12.29 |

0.15 |

| 600 |

1.44 |

0.0022 |

4.41 |

12.92 |

0.14 |

Table 6.

Chemical composition of insoluble residues obtained after chlorination roasting–acid leaching and direct chloride leaching (wt. %).

Table 6.

Chemical composition of insoluble residues obtained after chlorination roasting–acid leaching and direct chloride leaching (wt. %).

| Process |

Residue mass

( % of cake) |

Pb |

Cu |

Fe |

Ag |

Zn |

Chlorination roasting +

acid leaching |

34.20 |

0.90 |

0.15 |

12.29 |

0.0027 |

4.46 |

| Direct chloride leaching |

45.00 |

1.57 |

0.19 |

7.98 |

0.0160 |

1.38 |

Table 7.

Metal extraction efficiencies ( %) obtained via the two leaching routes.

Table 7.

Metal extraction efficiencies ( %) obtained via the two leaching routes.

| Process |

Pb |

Ag |

Cu |

Fe |

Zn |

Chlorination roasting +

acid leaching |

98.68 |

98.09 |

65.29 |

39.04 |

36.01 |

| Direct chloride leaching |

96.79 |

84.55 |

39.94 |

45.26 |

34.63 |

Table 8.

Waste Acceptance Criteria (WAC) leaching limits for metals at L/S = 10 L/kg, compared with results from this study, mg/L.

Table 8.

Waste Acceptance Criteria (WAC) leaching limits for metals at L/S = 10 L/kg, compared with results from this study, mg/L.

| Element |

Inert

waste landfill |

Non-hazardous

(stable, non-reactive) |

Hazardous

waste landfill |

This

study |

| As |

0.5 |

2 |

25 |

<0.01 |

| Ba |

20 |

100 |

300 |

<0.01 |

| Cd |

0.04 |

1 |

5 |

<0.01 |

| Cr (total) |

0.5 |

10 |

70 |

<0.01 |

| Cu |

2 |

50 |

100 |

0.05 |

| Hg |

0.01 |

0.2 |

2 |

<0.01 |

| Mo |

0.5 |

10 |

30 |

<0.01 |

| Ni |

0.4 |

10 |

40 |

<0.01 |

| Pb |

0.5 |

10 |

50 |

0.12 |

| Sb |

0.06 |

0.7 |

5 |

<0.01 |

| Se |

0.1 |

0.5 |

7 |

<0.01 |

| Zn |

4 |

50 |

200 |

0.08 |

| Chlorides |

800 |

15 000 |

25 000 |

13.5 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).