1. Introduction

Neuroscientists have long sought to understand how molecular programs orchestrate the emergence of complex cognition and behaviour. Neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs), including autism spectrum disorder (ASD), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), and intellectual disability (ID), provide a powerful lens through which to interrogate these mechanisms. These conditions originate early in life, persist throughout the lifespan, and profoundly affect cognition, social interaction, and adaptive functioning. Despite decades of research, the biological principles that bridge gene regulation, neural circuit formation, and behavioural phenotypes remain only partially defined.

Classical genetic studies have identified numerous susceptibility loci across diverse NDDs, yet DNA variation alone explains only a fraction of heritability [

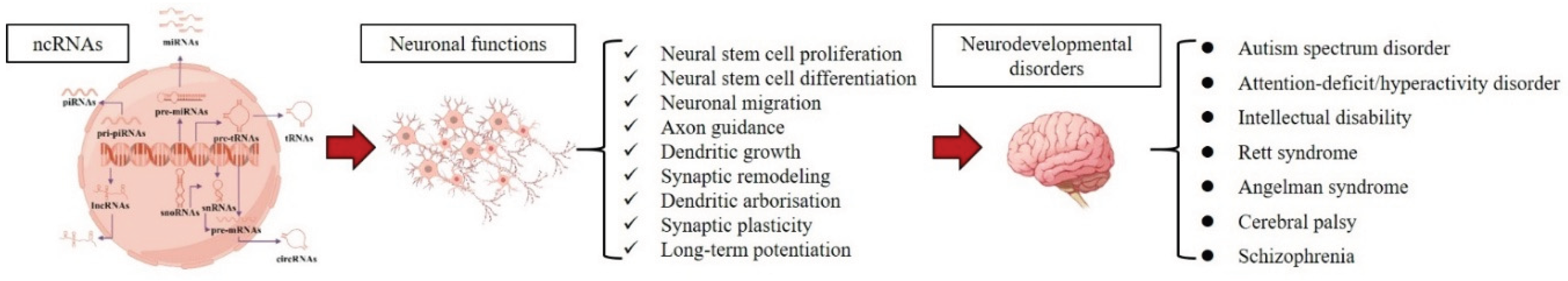

1]. This persistent gap has redirected attention from static genomic information toward the dynamic regulatory layers that govern gene expression. Among these, RNA-based mechanisms—and particularly non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs)—have emerged as crucial mediators that translate genetic potential into the cellular and circuit diversity of the developing brain. ncRNAs, encompassing microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), and transfer RNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs), shape transcriptional and translational landscapes with remarkable spatial and temporal precision. Their abundance, evolutionary conservation, and cell-type specificity in the brain position them as integral components of the molecular logic underlying neurodevelopment.

Technological advances in next-generation sequencing, single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, and integrative multi-omics approaches have transformed our understanding of this RNA layer. These tools now permit high-resolution mapping of ncRNA networks across neuronal and glial populations, revealing how distinct ncRNA signatures delineate vulnerable cell types, regulate synaptic plasticity, and intersect with epigenetic, metabolic, and neuroimmune pathways implicated in NDDs. In parallel, discoveries in extracellular vesicle (EV) biology have shown that ncRNAs circulate across the brain–body axis, functioning as long-range molecular messengers and offering a promising source of minimally invasive biomarkers.

Together, these findings reposition ncRNAs from passive by-products of transcription to active regulators of neural circuit assembly, maintenance, and plasticity. Yet several fundamental questions remain unresolved: How do ncRNA networks integrate genetic variation with environmental cues to sculpt neurodevelopmental trajectories? What principles govern their spatial organization, cell-type specificity, and intercellular mobility? And how can these insights be translated into RNA-guided diagnostics and therapeutics?

In this Review, we synthesize emerging evidence that defines the ncRNA landscape of neurodevelopmental disorders (

Figure 1). We discuss mechanistic pathways through which ncRNAs orchestrate brain development, highlight their translational potential as circulating biomarkers, and explore evolving strategies for therapeutic modulation. By integrating insights from genomics, transcriptomics, and systems neuroscience, we aim to outline how decoding the ncRNA regulatory axis may uncover unifying principles that link gene regulation to neural circuit function and the pathophysiology of neurodevelopmental disorders.

2. MicroRNAs in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Fundamental Roles of miRNAs in Neurodevelopment

The temporal and spatial choreography of microRNA (miRNA) expression mirrors the sequential milestones of brain development—from neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation to synaptic maturation and circuit refinement. During embryonic and early postnatal stages, canonical miRNAs such as miR-9, miR-124, and miR-132 orchestrate neurodevelopmental transitions by repressing multiple mRNA targets in a coordinated manner, thereby ensuring the precise timing of neuronal lineage commitment, axonal growth, and dendritic patterning [

2]. As neural circuits mature, these miRNAs act as molecular integrators that translate transcriptional, epigenetic, and environmental cues into finely tuned post-transcriptional programmes governing synaptic plasticity and network stability. Beyond cell-intrinsic regulation, miRNAs also function as mediators of intercellular communication. Exosome-encapsulated miRNAs, including miR-21, miR-132, and miR-134, are released by neurons and glia as vesicle-borne messengers that can traverse the blood–brain barrier and influence neuroimmune and metabolic signalling [

3]. Their extraordinary stability in extracellular fluids positions them as both local regulators of neural homeostasis and systemic biomarkers of neurodevelopmental health. Mechanistically, miRNA biogenesis is tightly coupled to neuronal activity and chromatin state. Activity-dependent transcription factors such as CREB and MEF2 directly regulate DROSHA/DICER processing, synchronising synaptic excitation with translational control [

2]. Disruption of these feedback loops perturbs temporal gene-expression synchrony, impairing synaptic refinement and predisposing to neurodevelopmental pathology. Collectively, miRNAs emerge as multi-scale regulators, integrating gene-network precision with environmental responsiveness, a dual property that underlies their potential both as molecular mediators of disease and as therapeutic entry points.

miRNAs and Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterised by extensive dysregulation of miRNA networks across cortical and subcortical regions, peripheral biofluids, and cellular models. Integrated mRNA–miRNA profiling of human post-mortem cortex reveals that mitochondrial and oxidative-phosphorylation genes are co-regulated by miR-181a-5p and miR-34a, defining a metabolic signature of neuronal stress [

4]. Environmental factors further shape this landscape: maternal hypoxia alters the miR-23b/27b/24 cluster in mice, transmitting epigenetic risk across generations [

5]. Network-level analyses highlight convergence between miRNA targets and high-confidence ASD genes such as CHD8, with the CHD8–Notch axis forming a miRNA-sensitive regulatory hub that governs neurogenesis [

6]. Functional studies confirm causal links between specific miRNAs and ASD-related phenotypes. In valproic-acid (VPA) models, loss of exosomal miR-215-5p activates the NEAT1/MAPK1/p-CRMP2 pathway, disrupting synaptic plasticity and social behaviour [

7]. In patient plasma, miR-195-5p levels correlate with symptom severity via FGFR1 regulation [

8], while miR-499a-5p achieves high diagnostic accuracy and associates with amygdala–caudate structural alterations [

9]. Systems biology identifies miR-21 as a pleiotropic node linking vascular stress with neurodevelopmental vulnerability [

10]. Computational analyses further suggest an epigenetic inheritance component: conserved autism-related miRNAs—including miR-146a, miR-181, and miR-21- are predicted to modulate DNA-methylation and histone-acetylation machinery [

11]. Depletion of AmnSINE1 repeat-derived transcripts in ASD cortex [

12] implies that miRNA–retrotransposon interactions contribute to transcriptomic instability during development. Animal and patient-derived cellular models reinforce these findings. BTBR mice exhibit broad prefrontal miRNA downregulation aligned with excitatory–inhibitory imbalance [

13]. In MEF2C-haploinsufficient hiPSC neurons and organoids, a gliogenic miRNA programme coincides with network hyperexcitability—both reversed by NMDA-receptor modulation [

14]. Therapeutically, miR-137 restoration via RVG-engineered extracellular vesicles rescues glucose metabolism, reduces neuroinflammation, and improves sociability in ASD models [

15]. Complementary plasma studies identify developmental shifts in miR-4433b-5p, miR-15a-5p, miR-335-5p, and miR-1180-3p, collectively yielding an AUC of 0.936 for early diagnosis [

16]. Together, these findings delineate a model in which miRNAs act as dynamic integrators of genetic, metabolic, and environmental risk—linking molecular dysregulation to behavioural diversity, while offering measurable and mechanistically interpretable biomarkers for precision stratification in ASD.

miRNAs and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) arises from disrupted molecular programmes that coordinate neurotransmission, neurotrophic signalling, and circadian rhythm. Multi-omics analyses reveal miRNA-regulated networks controlling synaptic transmission, dopamine metabolism, and clock-gene expression [

17]. In six European birth cohorts, 29 blood miRNAs correlate with hyperactivity and three with inattention, capturing behavioural variability consistent with clinical phenotypes [

18]. Case control studies identify downregulation of miR-34c-3p and miR-138-1, both targeting the BDNF pathway, accompanied by compensatory increases in serum BDNF [

19]. Mechanistic studies delineate converging miRNA circuits governing synaptic plasticity and attentional control. The lncMALAT1–miR-141-3p/200a-3p–NRXN1 axis modulates synaptic-adhesion gene expression, impairing learning and memory in ADHD models [

20]. In environmental paradigms, the miR-130/SNAP-25 pathway regulates presynaptic machinery in the anterior cingulate cortex and mediates lead-induced attentional deficits [

21]. Extracellular-vesicle profiling in adolescents identifies miRNA clusters overlapping with depression and anxiety yet retaining ADHD-specific patterns [

22]. Moreover, sex-biased miRNA expression in the developing mouse brain [

23] offers a plausible explanation for the higher prevalence of ADHD in males and the heterogeneity of symptom expression. Clinically, circulating miRNAs such as miR-26b-5p, miR-185-5p, and miR-142-3p have emerged as reproducible predictors of ADHD diagnosis and treatment responsiveness [

24,

25,

26]. Their peripheral stability and correlation with central neurotransmission pathways underscore their potential as non-invasive biomarkers for clinical stratification and longitudinal monitoring. These findings establish miRNAs as integrative regulators of dopaminergic, glutamatergic, and neurotrophic networks, bridging molecular neurobiology with translational psychiatry in ADHD.

Cross-Disorder Roles of miRNAs in Neurodevelopmental Impairment

The influence of miRNA dysregulation extends beyond ASD and ADHD to a broader continuum of disorders marked by cognitive, sensory, and motor impairment. In Rett syndrome, targeted modulation of miRNA-dependent X-chromosome inactivation ameliorates key phenotypes, suggesting that restoring MECP2 dosage via miRNA correction can re-establish transcriptional homeostasis [

27]. In perinatal hypoxia–ischaemia, bone-marrow-mesenchymal-stem-cell-derived exosomal miRNAs rescue cortical neurons and reduce gliosis, providing proof-of-concept for cell-free RNA therapies in cerebral palsy [

28]. Beyond neurons, glial miRNA signalling contributes critically to network stability. Human iPSC-derived astrocytes selectively package neuron-targeting miRNAs such as miR-483-5p and miR-138-5p into extracellular vesicles through FUS- and SRSF7-binding motifs, establishing a mechanism for astrocyte-to-neuron communication [

29]. The breadth of miRNA control is further exemplified by miR-34a-5p, which promotes hippocampal ferroptosis via SIRT1 suppression, linking metabolic stress to programmed cell death relevant to epileptic and developmental injury [

30]. At the systems level, the transcription factor NR4A2—a regulator of dopaminergic lineage specification and cognition—resides within miRNA-sensitive networks that bridge neurodevelopmental, psychiatric, and neurodegenerative spectra [

31]. Collectively, these cross-disorder findings converge on a unifying principle: miRNAs function as nodal regulators at the intersection of metabolism, chromatin architecture, and intercellular communication. Their pleiotropic influence across neuronal and glial compartments underscores both the vulnerability and the therapeutic plasticity of the developing brain.

3. Long Non-Coding RNAs in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Overview of lncRNA Biology in the Nervous System

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) comprise a heterogeneous class of transcripts (>200 nt) that regulate gene expression at epigenetic, transcriptional, and post-transcriptional levels. In the nervous system, lncRNAs direct neurogenesis, synaptogenesis, and circuit maturation through cis and trans mechanisms—recruiting chromatin modifiers, modulating transcriptional machinery, and scaffolding ribonucleoprotein complexes or ceRNA networks to fine-tune local translation and decay. Cross-disorder analyses highlight lncRNAs as central gatekeepers of neural homeostasis [

32]. Abundant transcripts such as NEAT1, MALAT1, and H19 orchestrate activity-dependent transcription, synaptic organization, and neuroinflammatory signalling, with region- and stage-specific isoforms enabling spatiotemporal precision. Advances in single-cell and total-RNA sequencing reveal lineage-restricted expression programs in neural progenitors and differentiated neurons, positioning lncRNAs as molecular nodes that couple chromatin architecture to transcriptional and synaptic plasticity [

33]. Collectively, lncRNAs emerge as architectural elements of the neural transcriptome—translating chromatin dynamics into adaptive gene-expression programs that underwrite neurodevelopmental complexity and vulnerability.

lncRNAs Regulation in Autism Spectrum Disorder

Converging evidence identifies lncRNAs as key intermediates linking genetic susceptibility, environmental stress, and synaptic dysfunction in ASD. In a landmark study, NEAT1 exacerbated ASD-like behaviours in valproic-acid–exposed mice by recruiting YY1 to the UBE3A promoter, enhancing transcription and promoting neuroinflammation and oxidative stress [

34]. This axis intersects with miRNA-mediated regulation: reduced exosomal miR-215-5p disinhibits the NEAT1/MAPK1/p-CRMP2 cascade, yielding parallel behavioural and synaptic phenotypes [

7], thereby positioning NEAT1 as a nodal regulator that couples environmental perturbation to transcriptional imbalance and circuit pathology. Beyond single transcripts, population-scale profiling demonstrates broad lncRNA perturbation. Peripheral blood analyses reveal altered PCAT-29, LINC-PINT, lincRNA-p21, lincRNA-ROR, and PCAT-1 [

35]. Independent plasma studies identify circulating LINC00662, LINC00507, and LINC02259, implicating immune and synaptic pathways and highlighting the potential of blood-based lncRNA diagnostics [

36]. Mechanistic modelling emphasizes strong cell-type specificity. Using a causal-inference framework (Cycle) on human single-nucleus RNA-seq, glial- and excitatory-restricted lncRNA hubs, such as SOX2-OT and MIR155HG, show high ASD-gene connectivity and coordinate modules for synaptic vesicle cycling and immune activation [

37]. Cross-species analyses reinforce conservation: in Microtus ochrogaster, pair-bonding engages transcriptional programs that overlap human psychiatric-risk genes, including lncRNA-regulated neurodevelopmental modules [

38]. Discrete lncRNA–protein and lncRNA–miRNA axes further refine the mechanism. The H19/miR-484 pathway tracks ASD severity and implicates oxidative and mitochondrial stress responses [

39]. The CHD8–SINEUP RNA interaction exemplifies translational up-regulation: SINEUP restores protein synthesis and rescues CHD8-suppression phenotypes without altering mRNA abundance [

40]. Genetic association connects dysregulated Csnk1a1p to kinase-mediated neurodevelopmental signalling [

41]. Together, these findings portray ASD as a disorder of transcriptional and post-transcriptional instability in which lncRNAs act both as drivers and buffers of regulatory homeostasis.

lncRNAs Regulation in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Mounting multi-omic, functional, and genetic data support lncRNA involvement in ADHD, particularly across circadian, synaptic, and cognitive domains. Peripheral profiling identifies rhythm-linked lncRNAs HULC and UCA1 as significantly elevated in ADHD independent of diurnal preference—suggesting disruption of lncRNA–clock feedback [

42]. Mechanistically, the lncMALAT1–miR-141-3p/200a-3p–NRXN1 axis regulates synaptic adhesion and constrains learning and memory capacity [

20], consistent with synaptic-plasticity deficits underlying cognitive symptoms. Genetic and structural data corroborate causality: a paracentric inversion disrupting SHANK2 and neighbouring LINC02714 was identified in an individual with ADHD and neurodevelopmental comorbidities, illustrating how structural variation can co-perturb protein-coding and non-coding loci essential for synaptic organization [

43]. Association analyses link RNF219-AS1 to ADHD behavioural phenotypes and white-matter microstructure [

44], while a SNP within BC200, a neuron-specific translational regulator, associates with multiple psychiatric disorders including ADHD [

45]. These observations define a multifactorial model in which lncRNAs operate at the intersection of circadian regulation, synaptic adhesion and structural genome integrity, translating regulatory imbalance into attentional and behavioural dysregulation.

lncRNA Dysfunction in Monogenic and Rare Neurodevelopmental Syndromes

LncRNA pathology extends to monogenic and rare syndromes where the non-coding element itself is causal. Deletion of CHASERR disrupts cis repression of CHD2, producing excessive CHD2 expression and a severe early-onset disorder with cortical atrophy and hypomyelination—establishing lncRNA haploinsufficiency as a direct pathogenic mechanism [

46]. In Rett syndrome, lncRNA regulation surfaces as both disease driver and therapeutic target. Modulation of microRNA-dependent X-chromosome inactivation alleviates Rett-like phenotypes [

27], while NEAT1 coordinates proteostasis and mRNA localization in neurons, shaping autophagy and stress resilience [

47]. Therapeutic platforms are beginning to leverage lncRNA biology directly. In Angelman syndrome, silencing of the paternal UBE3A allele by UBE3A-ATS can be reversed: an AAV-delivered dCas9 construct suppresses UBE3A-ATS transcription, unsilences paternal UBE3A and rescues behavioural deficits in mice—an allele-specific CRISPR interference proof-of-principle that avoids double-strand breaks [

48]. Additional lncRNA-dependent mechanisms link to cognition and learning: dysregulation of the MNK–SYNGAP1 axis perturbs synaptic signalling [

49], and lncRNA SPA, a splicing regulator during neural differentiation, is modulated by FUBP1, whose dual effects on SPA maturation underscore the intricacy of RNA-processing control [

50]. In sum, the mechanistic landscape of lncRNA biology spans transcriptional and epigenetic regulation, RNA processing, translation, and gene-dosage balance. LncRNAs are not merely modulators but direct determinants of disease expression, and increasingly, tractable targets for precision epigenetic intervention.

4. Circular RNAs in Neurodevelopmental Disorders

Biological Features of circRNAs in the Nervous System

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) are covalently closed, single-stranded transcripts generated by back-splicing, in which a downstream 5′ splice donor joins an upstream 3′ acceptor. This circular topology renders circRNAs resistant to exonucleolytic degradation, endowing them with exceptional molecular stability and enabling their preferential accumulation in post-mitotic tissues such as the brain. CircRNAs are evolutionarily conserved and exhibit striking spatial and temporal specificity, with pronounced enrichment at synapses—features that implicate them in activity-dependent gene regulation, neuronal differentiation, and synaptic plasticity [

32]. Functionally, circRNAs operate as multilayered regulators of gene expression. They act as molecular sponges for microRNAs and RNA-binding proteins, as scaffolds for ribonucleoprotein complexes, and as modulators of transcription or splicing of their host genes. In select cases, they even serve as templates for cap-independent translation. Within neurons, circRNAs integrate transcriptional and post-transcriptional control to fine-tune synaptic transmission, axonal guidance, and neuroimmune signalling. Their stability, conservation, and subcellular precision collectively position circRNAs as fundamental components of the neuronal regulatory architecture—and as promising candidates for biomarker discovery and therapeutic targeting in neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders.

circRNAs in Autism Spectrum Disorder

Convergent genetic, environmental, and post-transcriptional evidence identifies circRNAs as dynamic regulators in ASD. Genome-wide association and eQTL analyses reveal that genetic variants modulate circRNA biogenesis and abundance in a trans-regulatory fashion. Mai et al. demonstrated that circRNA quantitative trait loci (circQTLs) influence ASD risk by reshaping circRNA–miRNA–mRNA networks controlling synaptic and chromatin-regulatory genes—providing the first large-scale evidence that circRNAs serve as genetically anchored mediators of transcriptional variation contributing to ASD heritability [

51]. Environmental perturbations also remodel circRNA expression during neurodevelopment. In a murine model of air pollution exposure, Xie et al. identified 343 differentially expressed circRNAs mapping to synaptic and oxidative stress pathways [

52]. Notably, circRNAs derived from Dlgap1 and Grin2b, key postsynaptic density genes, were dysregulated—linking environmental insults to excitatory-circuit disturbances. These findings position circRNAs as transcriptional integrators bridging genetic susceptibility and environmental stress in ASD. Mechanistically, circRNAs exert their effects largely through competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks that buffer miRNA activity. Using plasma exosome sequencing, Zhao et al. reconstructed a comprehensive circRNA–miRNA–mRNA interactome, identifying 46 core circRNAs predicted to interact with miR-181b-5p, miR-15b-5p, and miR-218-5p—miRNAs previously linked to synaptic plasticity [

53]. These ceRNA modules converge on MAPK and calcium signalling pathways, offering a molecular framework for disrupted neuronal connectivity in ASD. Computational tools such as CircMiMi [

54] further enable cross-species prediction of circRNA–miRNA–mRNA interactions, uncovering conserved regulatory axes such as circ_0004104–miR-9–BCL11A, which modulate neuronal differentiation. Integration of these computational insights with multi-omics ASD datasets facilitates the prioritization of functionally validated ceRNA circuits for mechanistic study and therapeutic exploration. The exceptional stability of exosome-derived circRNAs also grants them strong biomarker potential. Together, current data define circRNAs as a multimodal regulatory layer that integrates inherited variation, environmental stress, and RNA-based intercellular communication—linking transcriptional instability to synaptic and metabolic dysfunction in ASD.

circRNA Networks Linking Developmental Injury, Plasticity, and Neuropsychiatric Pathology

Perinatal brain injury provides a natural context to examine how circRNAs regulate neural and muscular circuitry under early-life stress. Genome-wide circRNA sequencing in infants with cerebral palsy identified hsa_circ_0086354 as a differentially expressed transcript with high diagnostic accuracy, participating in inflammatory and cytoskeletal-remodelling networks [

55]. In parallel, studies in muscle satellite cells revealed that circNFIX modulates MEF2C, a transcription factor central to myogenesis and synaptic maturation, in patients with spastic cerebral palsy [

56]. These data suggest that circRNAs act at both neurogenic and myogenic interfaces, integrating central and peripheral transcriptional responses to developmental injury, and explaining the persistence of motor deficits after hypoxic–ischaemic events. Epitranscriptomic modification introduces an additional layer of control. In APP/PS1 mouse models, Zhang et al. identified widespread m

6A methylation of circRNAs associated with synaptic transmission and innate immune pathways [

57]. Such reversible marks may regulate circRNA stability, localization, and RBP interactions, adding fine-tuned plasticity to post-transcriptional regulation. Similarly, Siqueira et al. reported coordinated alterations in circRNAs and transcribed ultraconserved regions in mouse and human Rett models, converging on chromatin and synaptic pathways [

58]. This shared non-coding landscape implicates circRNAs in the MeCP2-dependent regulatory network controlling neuronal maturation and excitability.

CircRNA dysregulation also extends to early-onset psychiatric disorders. In first-episode schizophrenia, Zhang et al. identified region-specific modules such as hsa_circ_CORO1C–miR-708-3p–JARID2/LNPEP, linking epigenetic modifiers to neurodevelopmental signalling [

59]. Long et al. validated these networks by whole-transcriptome analysis, revealing convergence with dopaminergic and neuroinflammatory pathways [

60]. Du et al. demonstrated that plasma extracellular vesicle circRNAs form ceRNA networks overlapping neuronal adhesion and oxidative-stress genes [

61], suggesting that circRNAs shuttle regulatory information across central and peripheral compartments. Complementarily, Li et al. showed that activation of the ancestral retroviral envelope protein ERVWE1 upregulates circ_0001810, inducing mitochondrial dysfunction via AK2 and linking retroelement activation to circRNA-mediated neuronal stress [

62]. Beyond pathology, circRNAs also contribute to developmental architecture. Qi et al. described a conserved circRtn4–miR-24-3p–CHD5 axis promoting neurite outgrowth by derepressing the chromatin remodeler CHD5 [

63]. In Drosophila, the circular RNA Edis modulates neuronal differentiation and innate immunity via an Edis–Relish–castor feedback loop [

64,

65], highlighting evolutionary conservation of circRNA–immune crosstalk. Glial circRNAs also participate in stress responses: circFGFR2 triggers astrocytic pyroptosis in ischaemic stroke via inflammasome activation [

66], revealing mechanistic parallels between neuroinflammatory injury and early brain development.

CircRNAs participate in neuroprotective and degenerative processes alike. In epilepsy, Guo et al. identified hsa_circ_0000288 as a stabilizer of Caprin1, preserving synaptic integrity [

67], whereas circ_Csnk1g3 promotes hippocampal necroptosis and inflammation—effects reversed pharmacologically. Similar mechanisms extend into neurodegenerative contexts: circ_0049472 regulates PDE4A via miR-22-3p [

68], linking oxidative stress and RNA decay across Alzheimer’s and neurodevelopmental spectra. Across these diverse conditions, recurrent circRNA–miRNA–mRNA modules—including those involving miR-22-3p, CHD5, and MAPK signalling—suggest a unifying model of transcriptomic imbalance. CircRNAs act as stable molecular scaffolds, maintaining gene-expression networks across space and developmental time. Their closed-loop topology supports sustained regulatory control, translating genetic risk, environmental memory, and intercellular signalling into the long-term architecture of the brain.

At the systems level, circRNAs convert genetic variation into post-transcriptional misregulation via circQTLs [

51]; encode environmental memory, as in PM2.5-induced neurotoxicity [

52]; and mediate intercellular communication through exosomal transport [

53]. Mechanistically, they coordinate ceRNA crosstalk [

63], chromatin modification [

59], and immune–metabolic integration [

64,

65]. Together, these findings define circRNAs as evolutionarily conserved regulatory nodes connecting chromatin dynamics, neuronal excitability, and immune adaptation. Their detectability in biofluids and reversible post-transcriptional regulation make them compelling diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic entry points in neurodevelopmental medicine. With the advent of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, circRNA-mediated circuits can now be mapped at subcellular resolution, laying the groundwork for next-generation RNA therapeutics in developmental brain disorders.

5. tsRNAs and piRNAs as Emerging Neuroregulators

Transfer-RNA–derived small RNAs (tsRNAs) and PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) have moved from the periphery of RNA biology to the centre of neural regulation. Once viewed as germline-restricted or stress-responsive species, both classes are now recognised as integral components of the neuronal transcriptome that couple chromatin control, translational tuning, and epigenetic memory to developmental trajectories and plasticity. Their distinct biogenesis, rich chemical modification profiles, and persistence in post-mitotic neurons provide a molecular substrate for durable information storage that links metabolic and environmental cues to long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes. tsRNA biogenesis and actions. tsRNAs arise from precise cleavage of precursor or mature tRNAs by Dicer, ELAC2/RNase Z, RNase P, or angiogenin, yielding tRF-5, tRF-3, tRF-1, internal tRFs (i-tRFs), and longer stress-induced halves (tiRNAs). Fragment repertoires are cell-type- and context-specific, shaped by tRNA abundance, aminoacylation state, and modification density [

69,

70]. Angiogenin-dependent cleavage couples oxidative/metabolic stress to translational reprogramming, redirecting protein synthesis toward adaptive programmes. Beyond stress responses, tsRNAs modulate ribosome loading, interfere with initiation complexes, and fine-tune codon-specific translation efficiency—mechanisms that support activity-dependent plasticity and neuronal maintenance. piRNA biogenesis and actions. piRNAs (24–32 nt) are generated via a Dicer-independent pathway involving Zucchini-mediated cleavage and 3′/2′-O-methylation by HEN1, then associate with PIWIL1/HIWI and PIWIL2/HILI. Classically tasked with transposon repression through the ping–pong cycle, neuronal piRNAs additionally regulate mRNA stability, alternative splicing, and local translation, and interface with chromatin remodelling and DNA methylation pathways [

71]. Together, tsRNAs and piRNAs delineate an added tier of the neuronal epitranscriptome, bridging genome defence with adaptive gene regulation.

Multilayered Roles of tsRNAs in Translational Control and Neural Adaptation

In the developing brain, tsRNAs function as rapid post-transcriptional switches. Under oxidative or nutrient stress, angiogenin generates 5′-tiRNAs that inhibit cap-dependent translation by displacing the eIF4F complex from m

7G-capped mRNAs, conserving energy while sustaining essential survival synthesis [

69]. The tRNA modification landscape is a critical regulatory interface. Loss of 5-methylcytosine (m

5C) installed by NSUN2 or DNMT2 destabilises neuronal tRNAs, increases fragment production, and impairs differentiation, whereas N

1-methyladenosine (m

1A) and 7-methylguanosine (m

7G) tune Argonaute loading and target specificity [

72]. Enzymes such as NSUN2, TRMT6/61, METTL1, and WDR4 thus act as gatekeepers linking epigenetic state to translational capacity. Beyond global repression, tsRNAs execute sequence-specific, Argonaute-dependent silencing to fine-tune neurotrophin, MAPK, and mTOR signalling—core axes for dendritic growth and synaptic plasticity [

73]. In an Alzheimer’s model, the neuronal 5′-tRF tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 attenuated microglial activation and neuronal apoptosis by repressing the EphA7–ERK1/2–p70S6K pathway, illustrating precision control within neuroinflammatory–synaptic networks [

74].

tsRNAs also contribute to intergenerational inheritance. Ageing remodels sperm tsRNA repertoires targeting neurogenesis and synaptic pathways; microinjection of aged-sperm tsRNAs into naïve zygotes recapitulates anxiety-like behaviour and forebrain transcriptional changes in offspring [

75]. Therapeutically, leverage points include restoring modification homeostasis, delivering synthetic neuroprotective tsRNAs, or suppressing pathogenic fragments with antisense oligonucleotides—approaches that must account for modification-dependent stability, target affinity, and immunogenicity [

76].

piRNAs in Neural Regulation and Neurodevelopmental Disorders

piRNAs and PIWI proteins are enriched in hippocampal and cortical neurons, localising to dendrites and synapses where they modulate synaptic strength and memory consolidation. Disrupting PIWIL1/PIWIL2 impairs dendritic spine morphology and long-term potentiation, establishing a causal role for the pathway in cognition [

71]. Dysregulated piRNA landscapes are reported across neurological and neurodevelopmental diseases. In Parkinson’s disease, altered PIWI/piRNA expression in C. elegans and human tissue correlates with α-synuclein aggregation and dopaminergic loss [

77,

78], and loss of tdp-1 exacerbates piRNA mis-processing and neurotoxicity [

79]. In Alzheimer’s disease, large-scale plasma profiling identifies hundreds of differentially expressed piRNAs [

80,

81,

82]. These signatures converge on amyloid processing, tau phosphorylation, and neuroimmune control, underscoring dual roles as mechanisms and liquid biomarkers. In NDDs, including autism spectrum disorder, small-RNA sequencing of plasma and faecal samples detects brain-enriched piRNAs linked to synaptic and immune pathways [

83,

84,

85], suggesting participation in systemic communication beyond the CNS. Mechanistically, nuclear piRNAs recruit DNA- and histone-methyltransferase complexes to maintain transposon and synaptic-gene silencing, whereas cytoplasmic piRNAs engage long 3′-UTRs to tune local translation. Perturbation of either arm destabilises neuronal homeostasis, producing excitatory–inhibitory imbalance and circuit dysfunction typical of NDDs.

Interconnected Small-RNA Networks Linking Neurodevelopment

An emerging dimension of small-RNA biology lies in the gut–brain axis, where microbial and host signalling intersect to shape neurodevelopmental trajectories. In cohorts with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), coordinated alterations in microbiota composition and host piRNA expression, including species predicted to target cytokine and synaptic genes, have been identified in both stool and serum [

84]. These findings suggest that microbial metabolites or inflammatory cues can reprogram host piRNA landscapes, potentially influencing neuronal circuits via circulating extracellular vesicles enriched in small RNAs. Moreover, bacterial-derived tRNA fragments can enter the host circulation and modulate immune pathways that feed back onto neural development. Integrative analyses combining metagenomic, small-RNA, and metabolomic data are expected to uncover a multidirectional communication network in which tsRNAs and piRNAs translate microbial and environmental signals into epigenetic and neurodevelopmental outcomes. Viewed together, tsRNAs and piRNAs define a unified regulatory axis that complements and extends the established roles of miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs. Both classes link environmental and metabolic stimuli to transcriptional and translational control through chemically diverse, highly stable molecules capable of acting across cellular and temporal scales.

Enzymes governing tRNA methylation (NSUN2, TRMT6/61, METTL1) and piRNA maturation (HEN1, Zucchini) couple RNA modification to chromatin remodelling. Loss-of-function mutations in these pathways produce overlapping phenotypes—microcephaly, intellectual disability, and autistic-like behaviour—highlighting shared epigenetic control of neural development [

71,

72]. The remarkable stability and vesicular packaging of tsRNAs and piRNAs enable their transfer between cells and even across generations. In both extracellular vesicles and gametes, they transmit environmental or ageing-related information that can shape offspring neurodevelopment and stress resilience [

75,

83].

The presence of tsRNAs and piRNAs in plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and faeces makes them minimally invasive indicators capable of distinguishing disease states and progression [

80,

84]. Emerging RNA-based therapeutics—including antisense oligonucleotides, CRISPR-mediated modulation, and synthetic mimetics—seek to restore physiological small-RNA signalling and normalise neural gene expression [

74]. Together, these interconnected systems reveal a previously unrecognised layer of neurogenetic regulation that bridges metabolism, environment, and inheritance. tsRNAs act as rapid translators of metabolic and immune signals into local translational programmes, whereas piRNAs enforce durable epigenetic memory through PIWI-guided chromatin silencing. Their cooperation establishes a molecular grammar for encoding life-history information into neuronal function. As modification-aware single-cell and spatial transcriptomic technologies mature, resolving the cell-type-specific expression and interaction of tsRNAs and piRNAs will illuminate how these unconventional ncRNAs sculpt neural development, plasticity, and disease. This emerging paradigm recasts tsRNAs and piRNAs not as auxiliary regulators, but as foundational architects of the RNA-based regulatory circuitry that underpins cognition and neurodevelopmental health.

Table 1.

Disease-Linked ncRNAs in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disorders.

Table 1.

Disease-Linked ncRNAs in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disorders.

| |

ncRNA |

Aaxis |

Model System |

References |

| ASD |

miRNA |

miR-181a-5p, miR-34a |

Human post-mortem brain |

[4] |

| ASD |

miRNA/lncRNA |

miR-215-5p–NEAT1–MAPK1–p-CRMP2 |

VPA-induced ASD mouse model; exosomal miRNAs |

[7,34] |

| ASD |

miRNA |

miR-195-5p–FGFR1; miR-499a-5p |

Serum of children with ASD |

[8,9] |

| ASD |

lncRNA |

NEAT1–YY1–UBE3A |

Rat VPA model; cortical tissue |

[34] |

| ASD |

lncRNA |

PCAT-29, LINC-PINT, lincRNA-p21, lincRNA-ROR, PCAT-1 |

Peripheral blood of children |

[35] |

| ASD |

circRNA |

circRNA expression QTLs (circQTLs) |

Human genomic and transcriptomic datasets |

[51] |

| ASD |

circRNA |

PM2.5-induced circRNAs (Dlgap1-, Grin2b-derived) |

Mouse PM2.5 exposure ASD model |

[52] |

| ADHD |

miRNA |

miR-34c-3p, miR-138-1; miR-26b-5p, miR-185-5p, miR-142-3p |

Peripheral blood of children; multi-cohort analyses |

[18,19,24,25,26] |

| ADHD |

lncRNA/miRNA |

lncMALAT1–miR-141-3p/miR-200a-3p–NRXN1 |

ADHD rodent models; cellular assays |

[20] |

| ADHD |

miRNA |

miR-130–SNAP-25 |

Lead exposure models; ACC tissue |

[21] |

| Rett syndrome and related ID |

miRNA/lncRNA |

miRNA-dependent XCI; NEAT1 |

Rett mouse models; neuronal cultures |

[27,47] |

| CHASERR–CHD2 neurodevelopmental disorder |

lncRNA |

CHASERR |

Human patients; in vivo models |

[46] |

| Angelman syndrome |

lncRNA |

UBE3A-ATS |

Angelman mouse models; neuronal cultures |

[48] |

| Cerebral palsy (CP) |

miRNA/circRNA |

BMSC-derived exosomal miRNAs; hsa_circ_0086354; circNFIX–MEF2C |

Hypoxia–ischaemia models; infants with CP; muscle satellite cells |

[28,55,56] |

| Early-onset schizophrenia |

circRNA |

hsa_circ-CORO1C–miR-708-3p–JARID2/LNPEP; plasma EV circRNA networks |

Brain tissue; plasma EVs of first-onset patients |

[59,60,61] |

| Tic disorders and paediatric NDDs |

miRNA |

Plasma EV miRNA panels |

Plasma-derived small EVs |

[22,86] |

6. ncRNAs as Biomarkers: From Brain to Blood

The recognition that non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) circulate beyond the confines of the central nervous system has transformed the search for molecular biomarkers of neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). Unlike protein markers, which often degrade rapidly or reflect downstream pathology, ncRNAs display extraordinary biochemical stability due to compact secondary structures, association with RNA-binding proteins, and encapsulation within extracellular vesicles (EVs) [

1,

2]. These structural safeguards allow diverse ncRNA species—including microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), transfer-RNA-derived small RNAs (tsRNAs), PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs), small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs), and Y RNAs to persist in plasma, saliva, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and urine, thereby translating neuronal states into accessible peripheral readouts.

Across autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), peripheral transcriptomic analyses have identified reproducible ncRNA signatures paralleling the synaptic, mitochondrial, and immune gene networks disrupted in cortical and striatal regions. For example, serum miR-195-5p is elevated in ASD and correlates with clinical severity through FGFR1 regulation [

8], whereas miR-499a-5p demonstrates high diagnostic accuracy and associates with amygdala–caudate morphology [

9]. lncRNAs exhibit similar diagnostic potential: NEAT1 promotes UBE3A transcription and neuroinflammation [

34], while H19 correlates with symptom severity through the miR-484/oxidative-stress axis [

39]. These findings establish miRNAs and lncRNAs as peripheral reflections of central transcriptional imbalance, offering insight into molecular circuit dysfunction.

Mounting evidence indicates that EVs are the principal vehicles transporting brain-derived ncRNAs into circulation. Neuron- and astrocyte-derived exosomes can cross the blood–brain barrier while preserving their RNA cargo. Plasma EV profiling reveals enrichment for synaptic miRNAs and circRNAs involved in axon guidance and plasticity [

7,

15,

53]. These EV-associated ncRNAs likely originate from activity-dependent secretion, coupling neuronal firing and glial signaling to systemic circulation. Their encapsulation protects them from degradation and confers exceptional reproducibility, making EV-bound ncRNAs superior to freely circulating species for biomarker discovery.

Recent high-throughput studies extend this paradigm to additional ncRNA classes. piRNAs, once considered germline-restricted, are now detected in both brain and plasma, with disease-specific signatures. Large-scale sequencing identified hundreds of brain-enriched piRNAs distinguishing NDDs and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) with high accuracy [

80,

81,

82]. These piRNAs converge on chromatin-regulatory and synaptic pathways, suggesting that neuronal epigenetic programmes are echoed in circulation. Similarly, tRNA-derived fragments (tRFs) generated by angiogenin or Dicer regulate translation and oxidative-stress responses; altered methylation and abundance in patient serum mark metabolic imbalance [

69]. In both AD and ASD cohorts, tRFs associated with oxidative phosphorylation show consistent dysregulation, implicating tRNA-modifying enzymes such as NSUN2 and TRMT6/61 in neural vulnerability [

2,

72]. Previously overlooked ncRNAs—including snoRNAs and Y RNAs—are also emerging as circulating indicators. C/D box snoRNAs SNORD115 and SNORD116, transcribed from the imprinted 15q11–13 locus, are enriched in plasma EVs of AD patients and distinguish them from controls with high accuracy. Comparable snoRNA and Y-RNA fragments have been detected in ASD plasma [

84], suggesting evolutionarily conserved release mechanisms and cross-disease biomarker potential.

Realizing the clinical promise of ncRNA biomarkers requires standardized analytical frameworks. Pre-analytical variables—sample collection, haemolysis assessment, and data normalization—must be rigorously controlled [

1]. Comparative studies demonstrate that integrating total plasma RNA with EV-enriched RNA profiles enhances reproducibility and signal-to-noise ratio. Advanced detection platforms, including small-RNA-seq, total-RNA-seq, EV-RNA-seq, and targeted RT-qPCR panels, now permit comprehensive quantification across ncRNA classes. Analytically, machine-learning classifiers trained on multi-class ncRNA datasets outperform single-class models. In AD, combined lncRNA–piRNA–snoRNA signatures achieved AUC ≈ 0.96 [

80,

81], a framework now being extended to NDD subtype stratification and longitudinal monitoring.

Collectively, circulating ncRNAs constitute a stable, information-rich interface between the brain and periphery. Their biochemical stability [

1,

2], cell-type specificity [

7,

15], and cross-class complementarity define a multilayered communication network linking neural metabolism, epigenetic state, and systemic physiology. As modification-aware single-cell and spatial transcriptomic technologies evolve, it will become possible to map ncRNA release, trafficking, and uptake across neural circuits in vivo. Such frameworks promise blood-based monitoring of neurodevelopment and synaptic plasticity, transforming ncRNAs from static diagnostic markers into dynamic sentinels of brain health. Ultimately, circulating ncRNAs may serve not merely as biomarkers but as integrative molecular reporters—bridging the molecular, cellular, and systemic dimensions of neurodevelopmental biology.

Table 2.

Circulating ncRNAs as biomarkers in NDDs and related disorders.

Table 2.

Circulating ncRNAs as biomarkers in NDDs and related disorders.

| Disease |

Biofluid |

ncRNA Class |

Direction of Change |

References |

| ASD |

Serum |

miR-195-5p |

Up-regulated |

[8] |

| ASD |

Serum |

miR-499a-5p |

Up-regulated |

[9] |

| ASD |

Plasma |

Age-associated miRNA panel (miR-4433b-5p, miR-15a-5p, miR-335-5p, miR-1180-3p) |

Mixed age-dependent shifts |

[16] |

| ASD |

Peripheral blood |

lncRNAs PCAT-29, LINC-PINT, lincRNA-p21, lincRNA-ROR, PCAT-1 |

Down-regulated |

[35] |

| ASD |

Plasma EVs |

miR-215-5p |

Down-regulated |

[7] |

| ASD |

Plasma EVs |

circRNA panel (circRNA–miRNA–mRNA network) |

Multiple circRNAs are differentially expressed |

[53] |

| ASD |

Stool and serum |

piRNAs and miRNAs (gut–brain axis) |

Co-altered with microbiota composition |

[83,84,85] |

| ADHD |

Whole blood/plasma |

Panels of ~29 miRNAs (miR-26b-5p, miR-185-5p, miR-142-3p) |

Mixed |

[18,24,25,26] |

| Cerebral palsy |

Peripheral blood |

hsa_circ_0086354 |

Differentially expressed |

[55] |

| Schizophrenia |

Plasma EVs |

circRNA-mediated ceRNA networks |

Multiple circRNAs altered |

[61] |

7. Therapeutic Targeting of ncRNAs: From Bench to Bedside

The advent of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) therapeutics marks a conceptual shift from single-gene correction toward reprogramming entire regulatory networks. Because ncRNAs coordinate chromatin architecture, translational control, and synaptic plasticity, interventions at this level offer the ability to recalibrate dysregulated circuits that drive neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). Rather than editing individual loci, ncRNA-based strategies aim to restore network equilibrium, achieving molecular homeostasis through systemic regulatory rewiring.

Preclinical studies have demonstrated that re-establishing ncRNA balance can reverse both behavioural and molecular abnormalities in NDD models. In autism spectrum disorder (ASD), lentiviral re-expression of miR-137 or miR-215-5p restores glucose metabolism, suppresses neuroinflammation, and improves social behaviour [

7,

15]. Conversely, antisense inhibition of NEAT1, a lncRNA that recruits YY1 to the UBE3A promoter, mitigates valproic-acid–induced synaptic dysfunction [

34]. In Angelman syndrome, antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) targeting the UBE3A-ATS transcript unsilence the normally repressed paternal UBE3A allele—representing a landmark example of epigenetic reactivation through ncRNA modulation [

48]. These findings underscore ncRNAs as master regulators capable of reinstating transcriptional and metabolic stability when therapeutically tuned.

Emerging work extends ncRNA intervention to other molecular classes. Manipulating circular RNAs (circRNAs)—via siRNA-mediated knockdown of pathogenic isoforms or overexpression of neuroprotective ones—can remodel synaptic gene networks and attenuate neuroinflammation. Likewise, tRNA-derived fragments (tsRNAs) can be indirectly modulated by restoring the activity of tRNA-modifying enzymes such as NSUN2 or TRMT6/61, re-establishing the balance between translation repression and neuronal differentiation [

72]. Therapeutic exploration of PIWI-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) is at an earlier stage, yet enhancement of PIWI-protein activity or supplementation with protective piRNA pools may suppress transposon reactivation and neuroinflammatory cascades shared mechanisms in ageing and neurodegeneration. Together, these approaches highlight a continuum of regulatory intervention, where ncRNAs serve as molecular levers bridging chromatin state, translation efficiency, and cellular stress resilience.

The primary obstacle to ncRNA therapeutics remains efficient, cell-specific delivery across the blood–brain barrier (BBB). Advances in vector engineering now enable unprecedented precision. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors and lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) permit region- or cell-type–selective expression of ncRNA constructs, while exosome-based delivery offers a biologically compatible and immunologically inert alternative. In perinatal brain injury, exosomes derived from bone-marrow mesenchymal stem cells transfer neuroprotective miRNAs that rescue cortical neurons and reduce gliosis [

28]. Similarly, in Rett syndrome, manipulation of the X chromosome, linked lncRNA pathways via engineered vesicles, ameliorates neurological deficits [

27].

Integration of CRISPR–dCas9 systems with ncRNA promoters enables locus-specific activation or repression of endogenous genes, uniting RNA therapeutics with programmable epigenetic editing [

48]. These innovations collectively chart a path toward spatiotemporally controlled ncRNA therapeutics capable of modulating neural networks with surgical precision.

Despite these advances, several hurdles remain. Off-target hybridization, activation of innate immune sensors, and prolonged intracellular persistence demand rigorous pharmacological oversight. Comprehensive off-target mapping, immunogenicity testing, and pharmacokinetic modelling are essential to ensure safety. Next-generation designs incorporating switchable, biodegradable, or ligand-targeted systems aim to minimize immune activation while preserving delivery fidelity. Looking ahead, ncRNA pharmacology stands at the threshold of clinical translation. The convergence of synthetic biology, RNA chemistry, and neuro-epigenetics promises an era in which fine-tuning ncRNA circuitry may restore neurodevelopmental stability not by silencing disease, but by rebalancing the symphony of the neural transcriptome.

Table 3.

Therapeutic strategies targeting ncRNA pathways.

Table 3.

Therapeutic strategies targeting ncRNA pathways.

| Therapeutic |

ncRNA |

Disease |

Delivery |

References |

| miRNA mimic/replacement |

miR-137 |

ASD-like phenotypes in rodent models |

RVG-engineered extracellular vesicles |

[15] |

| miRNA mimic/replacement |

miR-215-5p |

VPA-induced ASD mouse model |

Viral vectors or EVs (preclinical) |

[7] |

| Antagomirs/ASO inhibitors |

miR-34a-5p |

Epilepsy and hippocampal ferroptosis models |

Chemically modified ASOs |

[30] |

| ASO-mediated knockdown |

NEAT1 |

Rett syndrome; VPA-induced ASD models |

Gapmer ASOs; viral vectors |

[34,47] |

| ASO knockdown/CRISPR interference |

UBE3A-ATS |

Angelman syndrome mouse models |

AAV–dCas9 constructs; ASOs |

[48] |

| siRNA/shRNA-mediated knockdown |

circ_0001810, circ-Csnk1g3 |

Schizophrenia; epilepsy models |

Viral vectors; nanoparticle delivery |

[62] |

| Overexpression of protective circRNA |

hsa_circ_0000288 |

Epilepsy mouse models |

Viral overexpression vectors |

[67] |

| Modulation of tRNA-modifying enzymes |

NSUN2, TRMT6/61, METTL1/WDR4 |

Microcephaly, ID, neurodevelopmental deficits |

Small molecules or gene therapy |

[71,72,74] |

| Synthetic tsRNA mimics |

tRFAla-AGC-3-M8 |

Alzheimer’s disease and neuroinflammation models |

Chemically stabilised RNA mimics |

[74] |

| PIWI–piRNA pathway enhancement |

Protective neuronal piRNA clusters |

Parkinson’s disease; neurodegenerative models |

Gene therapy; small-molecule PIWI modulators |

[71,77,78] |

| CRISPR–dCas9 epigenetic editing |

Enhancers, promoters, and lncRNA loci |

NDD risk loci in ASD and syndromic disorders |

AAV-delivered dCas9–KRAB/VP64 systems |

[48] |

8. Cell-Type-Specific ncRNA Networks Revealed by Single-Cell and Spatial Omics

The cellular heterogeneity of the human brain has long obscured the mechanistic understanding of non-coding RNA (ncRNA) function in neurodevelopmental disorders (NDDs). Recent advances in single-cell and spatial multi-omics now enable ncRNA expression to be mapped with unprecedented resolution—across cell types, developmental stages, and anatomical domains—revealing how discrete ncRNA programs orchestrate circuit formation and confer selective vulnerability to disease [

33].

Single-nucleus RNA sequencing of ASD cortex demonstrates that excitatory projection neurons, interneurons, and astrocytes possess distinct lncRNA and circRNA repertoires, many co-regulated with synaptic and immune pathways [

36,

37]. Among these, NEAT1 and MEG3 are selectively upregulated in astrocytes, where they coordinate inflammatory and stress-response gene programs [

34], whereas neuronal-specific lncRNAs interact with chromatin remodelers to govern activity-dependent transcription [

32]. Integration of single-cell transcriptomes with chromatin-accessibility and proteomic datasets identifies ncRNA-driven regulatory modules that define lineage-specific sensitivity to developmental perturbations, offering a molecular rationale for the cell-type-restricted pathology characteristic of NDDs.

Spatial transcriptomics extends these insights by preserving anatomical context. In both human and model systems, circRNAs enriched in cortical layer V neurons and hippocampal pyramidal cells localize to loci involved in synaptic-vesicle cycling and structural plasticity [

58]. Conversely, microglial lncRNAs cluster within neuroimmune hubs of the prefrontal cortex, aligning with region-specific inflammatory circuits [

32]. These spatially constrained transcriptional architectures suggest that ncRNA dysregulation produces circuit-specific pathophysiology rather than uniform global dysfunction, an emerging hallmark of complex neurodevelopmental disease.

Recent total-RNA single-cell technologies, capable of capturing non-polyadenylated species, have expanded ncRNA profiling to tsRNAs and piRNAs, providing the first cell-resolved view of small-RNA biology in the developing brain. These datasets reveal developmentally staged waves of small-RNA activity: tsRNAs dominate early neurogenesis, linking metabolic state to translational control, whereas piRNAs emerge during synaptogenesis, maintaining chromatin stability and repressing transposon activity [

69,

71]. Integration with live-cell imaging and metabolic labeling now enables real-time visualization of ncRNA turnover, illuminating how local RNA metabolism coordinates dendritic remodeling and synaptic plasticity.

As computational frameworks mature, the convergence of single-cell, spatial, and epitranscriptomic data is poised to generate three-dimensional atlases of ncRNA regulation across developmental time and brain architecture. These integrative maps will link molecular heterogeneity to neural-circuit function, forming the empirical basis for precision diagnostics and cell-type-specific RNA therapeutics. Ultimately, this emerging framework redefines ncRNAs not as static transcripts but as dynamic regulatory codes, encoding spatial and temporal logic into the developmental blueprint of the human brain.

Future Directions and Challenges

Collective evidence now positions non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) as the molecular infrastructure linking the genome, environment, and neuronal identity. Yet despite remarkable advances, major conceptual and translational challenges must be overcome before ncRNA biology can be fully translated into clinical neuroscience. Mechanistically, ncRNAs function not as isolated regulators but as interdependent components of a multilayered post-transcriptional ecosystem. miRNAs, lncRNAs, circRNAs, tsRNAs, and piRNAs share overlapping targets and RNA-binding partners, forming dynamic feedback circuits that fine-tune neuronal gene expression [

32,

70]. Disentangling this regulatory crosstalk is crucial for understanding emergent transcriptomic behaviours. Next-generation computational frameworks that integrate sequence complementarity, secondary structure, and spatial co-localization will be instrumental in predicting ncRNA–RNA and ncRNA–protein interactions at a systems level. Advances in machine learning and network biology are beginning to reveal how perturbations in one ncRNA class can ripple through the broader regulatory architecture, generating complex and sometimes nonlinear phenotypic outcomes.

An additional layer of regulation arises from the epitranscriptomic code—chemical modifications such as 5-methylcytosine (m5C), N6-methyladenosine (m6A), and pseudouridine (Ψ)—that diversify RNA stability, localization, and translation potential. Cell-type–resolved mapping of these marks will clarify how chemical diversity translates into functional specialization during brain development and plasticity. Understanding how ncRNAs intersect with RNA modifications to modulate chromatin state, neuronal differentiation, and circuit homeostasis represents one of the most pressing frontiers in neuroepigenetics.

Translationally, the field now faces the challenge of standardization and reproducibility. Large-scale, multi-centre cohorts with harmonized biofluid processing, unified normalization pipelines, and deep phenotypic characterization are required to validate ncRNA biomarkers across populations and developmental stages. Integrating ncRNA profiles with proteomic, metabolomic, and neuroimaging data will be essential to achieve the multidimensional precision necessary for regulatory qualification of diagnostic panels [

80,

83]. Establishing global data-sharing frameworks and analytical standards will accelerate reproducibility and foster cross-cohort meta-analysis, transforming ncRNA biomarker research from exploratory discovery to clinical validation.

On the therapeutic front, delivery and safety remain the key constraints. The convergence of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors, lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), and exosome-based carriers offers promising strategies to cross the blood–brain barrier and achieve cell-type-specific RNA delivery [

27,

28]. In parallel, CRISPR–dCas9 epigenetic editing now enables locus-specific activation or repression of ncRNA genes without inducing double-strand DNA breaks, allowing durable correction of transcriptomic dysregulation [

48]. Together, these advances define a rapidly maturing toolkit for precision RNA therapeutics in neurodevelopmental medicine.

The next frontier lies in connecting ncRNA dynamics to developmental time. Integration of spatial-omics atlases with longitudinal clinical and genetic datasets will enable reconstruction of ncRNA expression trajectories from embryogenesis through adulthood [

33]. Such frameworks will illuminate how early transcriptomic perturbations propagate through brain maturation, linking molecular alterations to circuit architecture and behavioural phenotype. Ultimately, this systems-level perspective will enable predictive modeling of neurodevelopmental trajectories, bridging genotype, cell-type vulnerability, and cognitive outcome.

Conclusion

ncRNAs have reshaped the molecular foundations of neuroscience. Once dismissed as transcriptional by-products, they are now recognized as architects of gene regulation, orchestrating an intricate network that links chromatin topology, transcriptional kinetics, translational control, and synaptic plasticity. Through their remarkable stability, mobility, and evolutionary adaptability, ncRNAs extend the influence of the genome beyond the boundaries of individual cells, conveying developmental state, metabolic condition, and environmental experience across tissues and even generations. As both mechanistic regulators and translational conduits, ncRNAs embody a new biological paradigm: one in which the nervous system encodes, adapts, and repairs itself through RNA-mediated communication. Their dual identity, as diagnostic sentinels and therapeutic levers, positions them as the molecular lingua franca uniting basic neurobiology with clinical neurodevelopmental medicine.

The challenge ahead lies not merely in cataloguing their diversity but in deciphering and harnessing their regulatory grammar, transforming the language of RNA biology into actionable strategies for diagnosis, prognosis, and precision therapy. In this emerging framework, ncRNAs are no longer peripheral to the central dogma: they represent its next evolutionary stage, the dynamic syntax through which the brain writes, edits, and preserves its own molecular narrative.

Author Contributions

JZ contributed to the acquisition of literature. JZ, SL, and XJ wrote the paper and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Karaivazoglou, K.; Triantos, C.; Aggeletopoulou, I. Non-Coding RNAs in Neurodevelopmental Disorders—From Diagnostic Biomarkers to Therapeutic Targets: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2025, 13, 1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.-T.; Chen, L.; Du, Y.; Jiang, Z.-Y.; Cheng, Y. MicroRNAs as Regulators, Biomarkers, and Therapeutic Targets in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 62, 5039–5056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.-N.; Zhu, H.-H.; Zhou, Z.-H.; Qu, K.-K. Exosomal microRNAs in common mental disorders: Mechanisms, biomarker potential and therapeutic implications. World J. Psychiatry 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, R.E.; Hill, Z.; Rose, S.; McCullough, S.; Porter-Gill, P.A.; Gill, P.S. Transcriptomic Signatures of Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Autism: Integrated mRNA and microRNA Profiling. Genes 2025, 16, 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güvenilir, E.; Şükranli, Z.Y.; Abusalim, M.R.S.; Oflamaz, A.O.; Doğanyiğit, Z.; Başaran, K.E.; Dolanbay, M.; Rassoulzadegan, M.; Taheri, S. Hypoxia Alters miRNAs Levels Involved in Non-Mendelian Inheritance of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2025, e68435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hua, S.; Jiao, D.; Chen, D.; Gu, Q.; Bao, C. Identification of Therapeutic Targets in Autism Spectrum Disorder through CHD8-Notch Pathway Interaction Analysis. PLOS ONE 2025, 20, e0325893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xie, L.; Shen, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Xu, D.; Bo, L.; Wu, L.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; et al. Reduced exosomal miR-215-5p activates the NEAT1/MAPK1/p-CRMP2 pathway and contributes to social dysfunction in a VPA-induced autism model. Neuropharmacology 2025, 278, 110539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Hou, Y.; Mao, J.; Gao, F. Expression of miR-195-5p in the serum of children with autism spectrum disorder and its correlation with the severity of the disease. Psychiatr. Genet. 2025, 35, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Bai, Y.; Gao, J.; Hou, Y.; Mao, J.; Gao, F.; Wang, J. Diagnostic Value of Serum miR-499a-5p in Chinese Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2025, 75, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Garg, P.; Trivedi, M.; Srivastava, P. Multiple system biology approaches reveals the role of the hsa-miR-21 in increasing risk of neurological disorders in patients suffering from hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2025, 39, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acerbi da Silva, L.N.; Stumpp, T. Bioinformatic Analysis of Autism-Related miRNAs and Their PoTential as Biomarkers for Autism Epigenetic Inheritance. Genes 2025, 16, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sciaraffa, N.; Santoni, D.; Greci, A.L.; Genovese, S.I.; Coronnello, C.; Arancio, W. Transcripts derived from AmnSINE1 repetitive sequences are depleted in the cortex of autism spectrum disorder patients. Front. Bioinform. 2025, 5, 1532981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mooney, C.; Parlante, A.; Canarutto, G.; Grigoli, A.; Scattoni, M.L.; Ricceri, L.; Jimenez-Mateos, E.M.; Sanz-Rodriguez, A.; Clementi, E.; Piazza, S.; et al. Deregulated mRNA and microRNA Expression Patterns in the Prefrontal Cortex of the BTBR Mouse Model of Autism. Mol. Neurobiol. 2025, 62, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trudler, D.; Ghatak, S.; Bula, M.; Parker, J.; Talantova, M.; Luevanos, M.; Labra, S.; Grabauskas, T.; Noveral, S.M.; Teranaka, M.; et al. Dysregulation of miRNA expression and excitation in MEF2C autism patient hiPSC-neurons and cerebral organoids. Mol. Psychiatry 2024, 30, 1479–1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Q.; Li, M.; Fan, L.; Zeng, X.; Zheng, D.; Wang, H.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, X.; Xing, L.; Wu, L.; et al. RVG engineered extracellular vesicles-transmitted miR-137 improves autism by modulating glucose metabolism and neuroinflammation. Mol. Psychiatry 2025, 30, 4072–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloum-Asfar, S.; Ltaief, S.M.; Taha, R.Z.; Nour-Eldine, W.; Abdulla, S.A.; Al-Shammari, A.R. MicroRNA Profiling Identifies Age-Associated MicroRNAs and Potential Biomarkers for Early Diagnosis of Autism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabana-Domínguez, J.; Artigas, M.S.; Arribas, L.; Alemany, S.; Vilar-Ribó, L.; Llonga, N.; Fadeuilhe, C.; Corrales, M.; Richarte, V.; Ramos-Quiroga, J.A.; et al. Comprehensive analysis of omics data identifies relevant gene networks for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dypås, L.B.; Duale, N.; Olsen, A.-K.; Bustamante, M.; Maitre, L.; Escaramis, G.; Julvez, J.; Aguilar-Lacasaña, S.; Andrusaityte, S.; Casas, M.; et al. Blood miRNA levels associated with ADHD traits in children across six European birth cohorts. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeidan, H.M.; Nashaat, N.H.; Hemimi, M.; Hashish, A.F.; Elsaeid, A.; El-Ghaffar, N.A.; Helal, S.I.; Meguid, N.A. Expression Patterns of miRNAs in Egyptian Children with ADHD: Clinical Study with Correlation Analysis. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 74, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhong, F.; Zhang, X.; Song, J.; Yuan, H.; Tian, T.; Hu, Y. Role of LncMALAT1-miR-141-3p/200a-3p-NRXN1 Axis in the Impairment of Learning and Memory Capacity in ADHD. Physiol. Res. 2023, 72, 645–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Guan, R.-L.; Zou, Y.-F.; Zheng, G.; Shen, X.-F.; Cao, Z.-P.; Yang, R.-H.; Liu, M.-C.; Du, K.-J.; Li, X.-H.; et al. MiR-130/SNAP-25 axis regulate presynaptic alteration in anterior cingulate cortex involved in lead induced attention deficits. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 443, 130249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honorato-Mauer, J.; Xavier, G.; Ota, V.K.; Chehimi, S.N.; Mafra, F.; Cuóco, C.; Ito, L.T.; Ormond, R.; Asprino, P.F.; Oliveira, A.; et al. Alterations in microRNA of extracellular vesicles associated with major depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity and anxiety disorders in adolescents. Transl. Psychiatry 2023, 13, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakats, S.; McAtamney, A.; Cross, H.; Wilson, M.J. Sex-biased gene and microRNA expression in the developing mouse brain is associated with neurodevelopmental functions and neurological phenotypes. Biol. Sex Differ. 2023, 14, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.J.; Kuo, H.C.; Lee, S.Y.; Huang, L.H.; Lin, Y.; Lin, P.H.; Li, S.C. MicroRNAs serve as prediction and treatment-response biomarkers of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and promote the differentiation of neuronal cells by repressing the apoptosis pathway. Transl. Psychiatry 2022, 12, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, P.; Pan, J.; Cai, Q.Q.; Zhang, F.; Peng, M.; Fan, X.L.; Ji, H.; Dong, Y.W.; Wu, X.Z.; Wu, L.H. MicroRNA profile as potential molecular signature for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. Biomarkers 2022, 27, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.; Wang, L.; Yen, C. Identification of diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Kaohsiung J. Med Sci. 2025, 41, e12931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.; Tihagam, R.D.; Wasko, U.N.; Equbal, Z.; Venkatesan, S.; Braczyk, K.; Przanowski, P.; Koo, B.I.; Saltani, I.; Singh, A.T.; et al. Targeting microRNA-dependent control of X chromosome inactivation improves the Rett Syndrome phenotype. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, Y.; Li, M.; Gao, L.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, C.; Tai, X. Spinal Tuina ameliorates cerebral palsy-associated neural impairment in hypoxia-ischemia model rats via BMSC-derived exosomal microRNAs. Brain Dev. 2025, 47, 104421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordillo-Sampedro, S.; Antounians, L.; Wei, W.; Mufteev, M.; Lendemeijer, B.; Kushner, S.A.; de Vrij, F.M.; Zani, A.; Ellis, J. iPSC-derived healthy human astrocytes selectively load miRNAs targeting neuronal genes into extracellular vesicles. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2024, 129, 103933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Yang, Z.; Li, J. The miR-34a-5p Promotes Hippocampal Neuronal Ferroptosis in Epilepsy by Regulating SIRT1. Neurochem. Res. 2025, 50, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sánchez, E.; Rojas, C.; Gómez, P.Y.; Martínez-Rodríguez, N.; Ruiz-Chow, Á.A.; Nava-Ruiz, C.; Ibáñéz-Cervantes, G.; Arciniega-Martínez, I.M.; Reséndiz-Albor, A.A.; Rojas, P. Regulation of NR4A2 Gene Expression and Its Importance in Neurodegenerative and Psychiatric Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 9162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilieva, M.S. Non-Coding RNAs in Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Unraveling the Hidden Players in Disease Pathogenesis. Cells 2024, 13, 1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isakova, A.; Quake, S.; Liu, D.; Cvijovic, I.; Sinha, R.; Eastman, A.; Weissman, I. Scalable single-cell total RNA-seq reveals non-coding programs in immunity, infection, and brain development. Res. Sq. 2025, 3, 7294776. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Zhou, H.; Chen, L.; Liu, Z. NEAT1 Promotes Valproic Acid-Induced Autism Spectrum Disorder by Recruiting YY1 to Regulate UBE3A Transcription. Mol. Neurobiol. 2024, 62, 846–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sane, S.; Ebrahimi, V.; Farsani, Z.S.; Ghafouri-Fard, S. Assessment of Expression of lncRNAs in Autistic Patients. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2024, 74, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serpe, C.; De Sanctis, P.; Marini, M.; Canaider, S.; Abruzzo, P.M.; Zucchini, C. Human Blood-Derived lncRNAs in Autism Spectrum Disorder. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, C.; Zhang, M.; Yang, H.; Wei, X.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, J. Modelling cell type-specific lncRNA regulatory network in autism with Cycle. BMC Bioinform. 2024, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila-González, D.; Lugo-Baca, J.; Camacho-Barrios, F.; Castro, A.; Arzate, D.; Paredes-Guerrero, R.; Díaz, N.; Portillo, W. Transcriptomic shifts in Microtus ochrogaster neurogenic niches reveal psychiatric-risk pathways engaged by pair-bond formation. Prog. Neurobiol. 2025, 253, 102831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Liu, C.; Jin, Q.; Yu, H.; Long, H. H19/miR-484 axis serves as a candidate biomarker correlated with autism spectrum disorder. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2025, 85, e10403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Leva, F.; Arnoldi, M.; Santarelli, S.; Massonot, M.; Lemée, M.V.; Bon, C.; Biagioli, M. SINEUP RNA rescues molecular phenotypes associated with CHD8 suppression in autism spectrum disorder model systems. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 1180–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, Z.; Rahmani, D.; Jazi, M.S.; Ghasemi, M.-R.; Sadeghi, H.; Miryounesi, M.; Razjouyan, K.; Bordbar, M.R.F. Altered expression of Csnk1a1p in Autism Spectrum Disorder in Iranian population: Case-control study. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkaya, C.; Karadag, M.; Hangul, Z.; Sahin, E.; Isbilen, E. Evaluation of the Regulatory Role of Circadian Rhythm Related Long Non-Coding RNAs in ADHD Etiogenesis. J. Atten. Disord. 2022, 27, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyghebaert, J.; Christiaenssen, B.; De Rademaeker, M.; Ende, J.V.D.; Vandeweyer, G.; Kooy, R.F.; Mateiu, L.; Annear, D. Paracentric inversion disrupting the SHANK2 gene. Eur. J. Med Genet. 2025, 75, 105009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, G.; Chen, W.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Qian, Q. A potential association of RNF219-AS1 with ADHD: Evidence from categorical analysis of clinical phenotypes and from quantitative exploration of executive function and white matter microstructure endophenotypes. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2021, 27, 603–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahaei, M.S.; Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Namvar, A.; Omrani, M.D.; Sayad, A.; Taheri, M. Association study of a single nucleotide polymorphism in brain cytoplasmic 200 long-noncoding RNA and psychiatric disorders. Metab. Brain Dis. 2020, 35, 1095–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesh, V.S.; Riquin, K.; Chatron, N.; Yoon, E.; Lamar, K.-M.; Aziz, M.C.; Monin, P.; O’Leary, M.C.; Goodrich, J.K.; Garimella, K.V.; et al. Neurodevelopmental Disorder Caused by Deletion of CHASERR, a lncRNA Gene. New Engl. J. Med. 2024, 391, 1511–1518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siqueira, E.; Velasco, C.D.; Tarrasón, A.; Soler, M.; Srinivas, T.; Setién, F.; Oliveira-Mateos, C.; Casado-Pelaez, M.; Martinez-Verbo, L.; Armstrong, J.; et al. NEAT1-mediated regulation of proteostasis and mRNA localization impacts autophagy dysregulation in Rett syndrome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolter, J.M.; James, L.M.; Boeshore, S.L.; Mao, H.; McCoy, E.S.; Ryan, D.F.; Fragola, G.; Taylor-Blake, B.; Stein, J.L.; Zylka, M.J. AAV-dCas9 vector unsilences paternal Ube3a in neurons by impeding Ube3a-ATS transcription. Commun. Biol. 2025, 8, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isik, C.M.; Bayyurt, E.B.T.; Sahin, N.O. The MNK-SYNGAP1 axis in specific learning disorder: Gene expression pattern and new perspectives. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2025, 184, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.H.; Nan, F.; Xu, G.; Wu, H.; Wei, M.Y.; Yang, L.; Wu, H. A dual effect of FUBP1 on SPA lncRNA maturation. RNA 2025, 31, 807–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, T.-L.; Chen, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chiang, T.-W.; Chuang, T.-J. Trans-genetic effects of circular RNA expression quantitative trait loci and potential causal mechanisms in autism. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27, 4695–4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Li, K.; Liang, X.; Tian, L.; Lin, B.; Yan, J.; Shi, Y.; Liu, X.; Xi, Z. Identification and characterization of circular RNA in the model of autism spectrum disorder from PM2.5 exposure. Front. Genet. 2023, 14, 970465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.; Zhong, Y.; Shen, F.; Cheng, X.; Qing, X.; Liu, J. Comprehensive exosomal microRNA profile and construction of competing endogenous RNA network in autism spectrum disorder: A pilot study. Biomol. Biomed. 2024, 24, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, T.-W.; Mai, T.-L.; Chuang, T.-J. CircMiMi: A stand-alone software for constructing circular RNA-microRNA-mRNA interactions across species. BMC Bioinform. 2022, 23, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; Bian, X.; Wu, C.; Wang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gu, X.; Zhuo, S.; Sun, S. Genome-wide analysis of circular RNAs and validation of hsa_circ_0086354 as a promising biomarker for early diagnosis of cerebral palsy. BMC Med Genom. 2022, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, B.; Hoque, P.; Robinson, K.G.; Lee, S.K.; Sinha, T.; Panda, A.; Shrader, M.W.; Parashar, V.; Akins, R.E.; Batish, M. The circular RNA circNFIX regulates MEF2C expression in muscle satellite cells in spastic cerebral palsy. J. Biol. Chem. 2024, 300, 107987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, S.; Han, S.; Sun, Y.; Han, M.; Zheng, X.; Li, F.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bi, J. Differential methylation of circRNA m6A in an APP/PS1 Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Mol. Med. Rep. 2023, 27, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, E.; Obiols-Guardia, A.; Jorge-Torres, O.C.; Oliveira-Mateos, C.; Soler, M.; Ramesh-Kumar, D.; Setién, F.; van Rossum, D.; Pascual-Alonso, A.; Xiol, C.; et al. Analysis of the circRNA and T-UCR populations identifies convergent pathways in mouse and human models of Rett syndrome. Mol. Ther.–Nucleic Acids 2021, 27, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]