1. Introduction

The pudendal nerve is a mixed sensory and motor nerve that supplies the perineum and external genitalia in both sexes. The nerve arises in the pelvic cavity from the anterior rami of spinal nerves S2, S3 and S4. The anatomical physiology of the nerve on MRI imaging can be seen in

Figure 1.

Pudendal neuralgia caused by pudendal nerve lesions is chronic, severely disabling, neuropathic pain in the distribution of the pudendal nerve.

It is a relatively rare condition in the general population, with an estimated incidence by the International Pudendal Neuropathy Foundation of 1 per 100,000 [

1]. However, the actual prevalence is believed to be substantially higher than previously reported, probably affecting up to 1% of the population with women affected more than twice as often as men [

2].

Pudendal neuralgia is often related to compression or entrapment of the pudendal nerve by the posterior pelvic ligaments (the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments) into the inter-ligamentous space or into Alcock’s canal [

3,

4,

5]. However, many other diseases of the pelvic structures can involve pudendal nerves and cause pudendal neuralgia.

The diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia is primarily clinical, according to the Nantes criteria [

3,

4,

5,

6]. The symptomatology affects the perineal and genital regions in both sexes and is usually worsened by sitting and relieved by standing or lying. Characteristically, patients are not awakened during sleeping. In addition, pain is not associated to objective sensory impairment and is relieved by pudendal nerve block.

Pudendal neuralgia is frequently underdiagnosed, confused with other causes of chronic pelvic and perineal pain and inappropriately treated, causing a delay in proper management and severely negatively impacting the quality of life [

3,

6].

Imaging is essential to explore potential causes of chronic pelvic pain and is decisive when it demonstrates a lesion able to account for the pudendal neuralgia [

3].

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) obtained with 1.5 or 3 Tesla scanners provide a high-quality anatomical study of the pelvic region, potentially allowing both detection of intrinsic pudendal nerve abnormalities as well as a possible definition of extrinsic causes of nerve injury. Despite that, only a few previous MRI studies are reported in the literature on the pudendal nerve and syndromes related to its damage [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

Aim of this study is to evaluate cases of pudendal neuralgia studied by MRI at our institution, to assess the site and mechanism of nerve damage and identify typical MRI diagnostic patterns.

2. Materials and Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 81 patients, 53 females (22-54 years old) and 28 males (19-59 years-old) with pudendal neuralgia clinical syndrome. Data collection spanned from 2017 to the present.

Patients with endometriosis, pelvic cancer, acute infections (e.g., perianal fistulas) and previous pelvic surgery were excluded.

In all patients with neuralgia in the territory of pudendal nerve innervation, we adopted an MRI protocol for pelvis and pelvic floor examination, using a 1.5 T MRI scanner (Ingenia, Philips Medical SDystems, Den Haag, Netherland).

In all patients MRI protocol included the following non-contrast enhanced sequences (Total Acquisition Time about 20 minutes) for anatomic evaluation of pelvic region:

Non-fat saturated axial, coronal and sagittal T2-weighted Fast Spin-Echo (FSE): TR 4000 msec, TE eff 100 msec, turbo factor 13, thickness 3 mm, parallel imaging SENSE AF 1.5.

Fat saturated axial T2-weighted FSE: TR 4500 msec, TE eff 100 msec, turbo factor 13, thickness 3 mm. TR 4000 msec, ET eff 100 msec, turbo factor 13, thickness 3 mm, parallel imaging SENSE AF 1.5, fat saturation obtained by Spectral Presaturation with Inversion Recovery (SPIR) strong.

Non-fat saturated Axial T1-weighted FSE: TR 450-550 msec, TE eff 10-15, turbo factor 3-5, thickness: 3 mm, parallel imaging SENSE AF 1.5.

Coronal and sagittal SSTSE T2-weighted myelography for detection of Tarlov cyst

In addition, in each patient EPI diffusion sequence encompassing all the course of the pudendal nerves, from sacrum to lower perineum, was acquired for neurography.

The parameters of the sequence were: TR 4100 msec, TE 85 msec, 3b (0, 100,600), acquisition matrix 125 x 100, EPI factor 41, Compressed Sense acceleration with reduction factor of 2.5, fat-suppression obtained by SPIR.

DWI Neurography Rationale

T2 fat-sat and STIR sequences are the most used and effective sequences to perform MR neurography and to detect peripheral nerves diseases.

Unfortunately, these sequences are affected by interferences due to moving blood in the vessels that generates signal hyperintensity interfering with the evaluation of the normal and abnormal nerves. The hyperintense vascular signal can also be a source of pitfalls [

14,

15]. Since DWI is a “Black Blood” sequence, it overcomes the issue of distinguishing between neural and vascular structures. T2 fat-sat sequence with cardiac triggering has been yet proposed to solve this problem [

10]. However, this technique is time consuming and signal from vessels is not sufficiently cancelled in some cases. 3D T2 fat-sat and fast-STIR neurography obtained after intravenous administration of gadolinium-chelate can better the quality of neurography of lumbar and brachial plexuses improving the suppression of the vascular signal. However, suppression of the signal from small peripheral vessels is not perfect and administration of gadolinium increase the cost of examination, exposes the patients to adverse reactions and is time consuming [

16,

17]

We overcame this obstacle using b600 diffusion-weighted images, as they are not affected by hyperintensities of vessels. Normally, in DWI sequences, lumbar and sacral nerve roots are hyperintense after exiting the neural foramina. Moreover, the sciatic nerve is always hyperintense along its entire course. On the other hand, the normal pudendal nerve does not appear hyperintense and it is not visible on DWI obtained with b600.

Two radiologists, one with 30 years’ experience and the second with 10 years’ experience evaluated the examinations to assess the presence of abnormalities. The final decision was obtained by consensus.

3. Results

In 42 patients, we observed hyperintensity of the pudendal nerve on DWI-weighted MR scans. Pudendal nerve abnormalities were unilateral in 33/42 patients and bilateral in 9/42

In 23/42 patients, pudendal nerve abnormalities are found in association with extra-neural abnormalities which with high probability played a role in the onset of pudendal neuralgia. Specifically, we observed the following pathologies:

- 1)

Hemorragic Tarlov’ cyst of the sacrum (1 patient)

- 2)

Unilateral or bilateral hypertrophy of the pyriform muscle (4 patients)

- 3)

Unilateral or bilateral lesions of the sacrotuberous and/or sacrospinous ligaments (interligamentous space) (5 patients)

- 4)

Unilateral rupture of puborectal and/or pubococcygeal muscle (4 patients)

- 5)

Perineal fibrosis involving Alcok’s canal (4 patients)

- 6)

Giant cyst of the prostatic utricle (1 patient)

- 7)

Pudendal nerve schwannomas (2 patients)

- 8)

Varices of the pudendal vein in the Alcock canals (2 patients)

3.1. Rapresentative Case (Figure 9)

A 33-year-old man suffered from a disabling perineal and scrotal pain lasting 3 years. The patient had been an amateur cyclist active for about 10 years. Pressure placed on the left nerve at the Alcock canal and medial to the ischial spine reproduced pain (Valleix phenomenon). MRI showed a thinning of the left sacrotuberous ligament probably due to laceration secondary to chronic microtrauma by cycling. Left pudendal nerve in the Alcock canal was hyperintense on b600 diffusion weighted scan. Block of the left pudendal nerve was performed with temporary relief (1 week) of the symptomatology.

4. Discussion

The pudendal nerve arises in the pelvic cavity from the anterior rami of spinal nerves S2, S3 and S4, then leaves the pelvis through the lower part of the greater sciatic foramen passing between the piriformis and coccygeus muscles

It runs between the sacrospinous and sacro-tuberous ligaments and reenters the pelvis through the lesser sciatic foramen accompanying the internal pudendal vessels forwards along the pudendal canal in the lateral wall of the ischiorectal fossa where is contained in a sheath of the obturator fascia [

4,

18,

19]

Along this tortuous pathway the pudendal nerve is exposed to injuries, namely entrapment.

In the general population, chronic pudendal neuralgia is a very uncommon illness, occurring in 1% of people and being more common in women [

1]. The genital and perineal areas of both sexes are affected by the symptomatology with typical worsening when sitting.

According to Nantes criteria, the key clinical points for diagnosis are represented by:

- 1)

the topographical distribution of the pain (from the anus to the penis or clitoris)

- 2)

exacerbation of pain when sitting

- 3)

lack of awakening during the night

- 4)

lack of objective sensory alterations

- 5)

response to pudendal nerve block.

Complementary diagnostic criteria are burning, shooting, stabbing pain, numbness, allodynia or hyperpathia, rectal or vaginal foreign body sensation, worsening of pain during the day, predominantly unilateral or triggered by defecation pain, and dyspareunia (painful intercourse).

Pudendal neuralgia is often related to compression or entrapment of the pudendal nerve along its course. The pudendal nerve is a mixed nerve having sensory, motor, and autonomic functions. It originates from the ventral branches of the second, third, and fourth sacral nerve roots (S2, S3, S4). It courses close to the anterior surface of the piriformis muscle, then exits the pelvis between the piriformis and coccygeus muscles (lower part of the greater sciatic foramen) and, after a brief extra-pelvic course between the sacrospinous and sacro-tuberous ligaments (interligamentous space), runs around the ischial spine and enters the perineum. In its distal course the nerve lies in the pudendal canal (Alcock’s canal) close to the internal pudendal vessels. Alcock’s canal is situated along the lateral wall of the ischiorectal fossa, with its covering formed by the obturator fascia. In its course into the Alcock canal, pudendal nerve gives rise to its terminal branches, including the inferior rectal nerve and the dorsal nerve of the penis or clitoris.

MRI provides good anatomical definition of the pelvic region, with visualization of the pudendal nerve, especially in its proximal segments. For this purpose, high spatial resolution (3 mm thick) T1 and T2-weighted scans along three Euclidean planes and 4-mm-thick EPI diffusion with b600 are particularly suitable (

Figure 1). MRI assessment of the distal branches of the pudendal nerve becomes more difficult, even after surgical marking [

7]

The most common cause of pudendal neuralgia is considered entrapment between the posterior pelvic ligaments (the sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments) compressing or trapping the pudendal nerve within the interligamentous region and/or at its entrance to the Alcock’s canal [

1,

2,

3,

4,

18,

19].

In addition, the pudendal nerve can be involved at the level of the sub-piriform canal, resulting in the piriform syndrome, which can cause both sciatica and, less frequently, pudendalgia. Entrapment of the distal branches of pudendal nerve (dorsal nerve of the clitoris/penis) can occur at the level of the distal Alcock’s canal.

Onset of pudendal neuralgia is often related to difficulties during childbirth (secondary to excessive stretching), trauma, sequelae of surgeries and radiotherapy, prolonged bicycle riding, pelvic fractures and neoplasms.

Tarlov cysts have been reported in literature as another potential cause of chronic lumbosacral and pelvic pain. Specifically, they are often located in the distribution of the pudendal nerve origin at the sacral nerve roots S2, S3, and S4, and it has been postulated that they may cause symptoms like pudendal neuralgia [

20,

21]. However, a recent study questions the actual role of Tarlov cysts in the genesis of pudendal neuralgia [

22]. In our cohort, a case of Tarlov cyst involved in traumatic fracture of the sacrum was considered as the probable cause of pudendal neuralgia since surgical decompression of the cyst relieved the symptoms.

Only a few previous studies on the pudendal nerve and the diagnostic potential of MRI in patients with pudendal neuralgia have been reported in the literature [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Most of these focus on MRI neurography of the pudendal nerve, by emphasizing that hyperintensity of the nerve is a crucial element for diagnosis of neuropathy.

Magnetic resonance neurography is based on sequences that suppress background tissues (including signal from small vessels) and highlight water content within nerves.

With the recent advancement in MR hardware and imaging techniques, several approaches to the MRI neurography of peripheral nerves has been proposed [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32].

In our experience, unlike other districts and for reasons related to the anatomical peculiarities of the pudendal nerve, vessels hyperintensity on T2-weighted fat-sat and STIR sequences, used to obtain MRI neurography, makes the diagnosis of pudendal neuropathy quite challenging. In addition, different MRI techniques were used and reported in the radiological literature and MRI diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuropathy were not clearly defined. In approximately half of our patients, we identified a DWI signal alteration of the pudendal nerve using thin-slice axial scans with an appropriate b value. The sensitivity of these sequences seems to be linked to the intrinsic characteristics of the nerve, which is composed of diamagnetic molecules [

33], and to its histological structure, which causes anisotropic diffusion of water [

32].

Therefore, based on these observations, we propose simple but effective diagnostic MRI criteria for assessing pudendal neuropathy. Specifically, the pudendal nerve should be considered abnormal if there is evident hyperintensity (comparable to that of the normal ipsilateral sciatic nerve) along its course on two consecutive or three non-consecutive b600 DWI images. (

Figure 2)

Finally, it is necessary to emphasize that in our cohort 39 out of 81 patients with symptoms compatible with pudendal neuralgia had not abnormalities on MRI examination. The cause of this negativity on MRI is not known, and the topic is worthy of further study. Probably some of these cases are due to acquired or genetically related (e.g., Charcot-Marie- Tooth) sensory neuropathies of the peripheral nerves [

34], not detectable with an MRI examination for limits of spatial and contrast resolution.

Limitations and Advantages

Our paper suffers of two main limitations:

1) All patients were studied with a 1.5 tesla scanner. Since 3 Tesla scanner improves the spatial resolution, we could expect better results with such a type of technology. Further studies performed with 3 Tesla scanner on groups of patients with pudendal neuralgia should be obtained.

2) We did not explore the potential role of new techniques as 3d T2 weighted sequence with blood signal suppression by a pre-saturation pulse that is a promising technique for studying small nerve branches without interference of small vessels signal [

35,

36,

37,

38]. To the best of our knowledge, reports on the use of this approach in patients with pudendal neuralgia have not yet been published.

However, there are some clear advantages in our approach based on diffusion neurography in patients with pudendal neuralgia.

These advantages are:

1) The technique is available on every 1.5 and 3 tesla scanners

2) It is solid and reliable in absence of metallic orthopedic hardware

3) The administration of gadolinium is not required.

5. Conclusions

In our study, we focused on the effective application of MRI in patients with a clinical diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia. MRI examination can be considered the gold standard in this field of pathology due to its non-invasive nature and good sensitivity and specificity. We also proposed an MRI protocol and diagnostic criteria emphasizing the role of the DWI sequence, which is a rapid, robust and largely available technique for assessing pudendal nerve abnormalities

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Michele Gaeta; methodology Francesca Granata; software, Sofia Turturici; formal analysis, Sofia Turturici, Karol Galletta, Marco Cavallaro, Salvatore Silipigni; investigation, Michele Gaeta, Francesca Granata; resources, Karol Galletta, Marco Cavallaro, Salvatore Silipigni, data curation, Aurelio Gaeta, Attilio Tuscano, Carmelo Geremia; writing—original draft preparation, Michele Gaeta and Francesca Granata; writing—review and editing, Michele Gaeta and Francesca Granata; visualization, Michele Gaeta, Francesca Granata; supervision, Michele Gaeta and Francesca Granata.; project administration, Michele Gaeta, Francesca Granata and Sofia Turturici. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by Ethics Committee of Messina (protocol code 9025; date of approval on 9th September 2025).”

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leslie, S.W.; Antolak, S.; Feloney, M.P.; Soon-Sutton, T.L. Pudendal Neuralgia. 2022 Nov 28. In: StatPearls. [PubMed]

- Hibner, M.; Desai, N.; Robertson, L.J.; Nour, M. Pudendal neuralgia. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010, 17, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labat, J.J.; Riant, T.; Robert, R.; Amarenco, G.; Lefaucheur, J.P.; Rigaud, J. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurourol Urodyn. 2008, 27, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, R.; Prat-Pradal, D.; Labat, J.J.; Bensignor, M.; Raoul, S.; Rebai, R.; Leborgne, J. Anatomic basis of chronic perineal pain: role of the pudendal nerve. Surg Radiol Anat. 1998, 20, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ploteau, S.; Labat, J.J.; Riant, T.; Levesque, A.; Robert, R.; Nizard, J. New concepts on functional chronic pelvic and perineal pain: pathophysiology and multidisciplinary management. Discov Med. 2015, 19, 185–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kaur, J.; Leslie, S.W.; Singh, P. Pudendal Nerve Entrapment Syndrome. StatPearls. January 2022. [PubMed]

- Chhabra, A.; McKenna, C.A.; Wadhwa, V.; Thawait, G.K.; Carrino, J.A.; Lees, G.P.; Dellon, A.L. 3T magnetic resonance neurography of pudendal nerve with cadaveric dissection correlation. World J Radiol. 2016, 8, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wadhwa, V.; Hamid, A.S.; Kumar, Y.; Scott, K.M.; Chhabra, A. Pudendal nerve and branch neuropathy: magnetic resonance neurography evaluation. Acta Radiol. 2017, 58, 726–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filler, A.G. Diagnosis and management of pudendal nerves entrapment syndrome: impact of MR neurography and open MR guided injections. Neurosurg Q 2008, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piloni, V.; Bergamasco, M.; Chiapperin, A.; et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of pudendal nerve: technique and results. Pelviperineology. 2020, 39, 132–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piloni, V.; Bergamasco, M.; Bregolin, F.; et al. MR imaging of the pudendal nerve: a one-year experience on an outpatient basis. Pelviperineology 2014, 33, 54–59. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, J.; Scott, K.; Xi, Y.; Ashikyan, O.; Chhabra, A. Role of 3 Tesla MR Neurography and CT-guided Injections for Pudendal Neuralgia: Analysis of Pain Response. Pain Physician. 2019, 22, E333–E344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Murphy, K.; Nasralla, M.; Pron Get, a.l. Management of Tarlov cysts: an uncommon but potentially serious spinal column disease—review of the literature and experience with over 1000 referrals. Neuroradiology 2024, 66, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N.G.; Talbott, J.; Chin, C.T.; Kliot, M. Peripheral nerve imaging. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 2016, 136, 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muniz Neto, F.J.; Kihara Filho, E.N.; Miranda, F.C.; Rosemberg, L.A.; Santos, D.C.B.; Taneja, A.K. Demystifying MR Neurography of the Lumbosacral Plexus: From Protocols to Pathologies. Biomed Res Int. 2018, 2018, 9608947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chhabra, A.; Madhuranthakam, A.J.; Andreisek, G. Magnetic resonance neurography: current perspectives and literature review. Eur Radiol 2018, 28, 698–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneag, D.B.; Daniels, S.P.; Geannette, C.; Queler, S.C.; Lin, B.Q.; de Silva, C.; Tan, E.T. Post-Contrast 3D Inversion Recovery Magnetic Resonance Neurography for Evaluation of Branch Nerves of the Brachial Plexus. Eur J Radiol. 2020, 132, 109304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafik, A.; el-Sherif, M.; Youssef, A.; Olfat, E.S. Surgical anatomy of the pudendal nerve and its clinical implication. Clinical Anatomy 1995, 8, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapletal, J.; Nanka, O.; Halaska, M.J.; Maxova, K.; Hajkova Hympanova, L.; Krofta, L.; Rob, L. Anatomy of the pudendal nerve in clinically important areas: a pictorial essay and narrative review. Surg Radiol Anat. 2024, 46, 211–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seaman, W.B.; Furlow, A.D.L.T. The myelographic appearance of sacral cysts. J Neurosurg 1956, 13, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta, F.L.; Quinones-Hinojosa, A.; Schmidt, M.H.; Weinstein, P.R. Diagnosis and management of sacral Tarlov cysts. Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurg Focus 2003, 15, E15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, V.M.; Khanna, R.; Kalinkin, O.; Castellanos, M.E.; Hibner, M. Evaluating the discordant relationship between Tarlov cysts and symptoms of pudendal neuralgia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020, 222, e1–e70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takahara, T.; Hendrikse, J.; Yamashita, T.; Mali, W.P.; Kwee, T.C.; Imai, Y.; Luijten, P.R. Diffusion-weighted MR neurography of the brachial plexus: feasibility study. Radiology. 2008, 249, 653–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, E. Imaging of peripheral nerve causes of chronic buttock pain and sciatica. Clin Radiol. 2021, 76, e1–e626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Noguerol, T.; Montesinos, P.; Hassankhani, A.; Bencardino, D.A.; Barousse, R.; Luna, A. Technical Update on MR Neurography. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2022, 26, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitman, J.; Lin, Y.; Tan, E.T.; Sneag, D. Magnetic Resonance Neurography of the Lumbosacral Plexus. Radiol Clin North Am 2023, 62, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Tan, E.T.; Campbell, G.; et al. Improved 3D DESS MR neurography of the lumbosacral plexus with deep learning and geometric image combination reconstruction. Skeletal Radiol 2024, 53, 1529–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Kong, X.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, X.; Gu, Y.; Xu, L. Enhanced MR neurography of the lumbosacral plexus with robust vascular suppression and improved delineation of its small branches. Eur J Radiol 2020, 129, 109128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, A.; Kanchustambham, P.; Mogharrabi, B.; Ratakonda, R.; Gill, K.; Xi, Y. MR Neurography of Lumbosacral Plexus: Incremental Value Over XR, CT, and MRI of L Spine With Improved Outcomes in Patients With Radiculopathy and Failed Back Surgery Syndrome. J Magn Reson Imaging 2023, 57, 139–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, J.; Lin, Y.; Tan, E.T.; Sneag, D.B. MR Neurography of the Lumbosacral Plexus: Technique and Disease Patterns. RadioGraphics 2025, 45, e240099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Meng, Q.; Chen, Y.; et al. 3-T imaging of the cranial nerves using three-dimensional reversed FISP with diffusion-weighted MR sequence. J Magn Reson Imaging 2008, 27, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foesleitner, O.; Sulaj, A.; Sturm, V.; Kronlage, M.; Godel, T.; Preisner, F.; Nawroth, P.P.; Bendszus, M.; Heiland, S.; Schwarz, D. Diffusion MRI in Peripheral Nerves: Optimized b Values and the Role of Non-Gaussian Diffusion. Radiology 2022, 302, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaeta, M.; Cavallaro, M.; Vinci SLet, a.l. Magnetism of materials: theory and practice in magnetic resonance imaging. Insights Imaging 2021, 12, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmar, J.M.; Laing, N.G.; Kennerson, M.L.; Ravenscroft, G. Genetics of inherited peripheral neuropathies and the next frontier: looking backwards to progress forwards. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2024, 95, 992–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Cruyssen, F.; Croonenborghs, T.M.; Hermans, R.; Jacobs, R.; Casselman, J. 3D Cranial Nerve Imaging, a Novel MR Neurography Technique Using Black-Blood STIR TSE with a Pseudo Steady-State Sweep and Motion-Sensitized Driven Equilibrium Pulse for the Visualization of the Extraforaminal Cranial Nerve Branches. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2021, 42, 578–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klupp, E.; Cervantes, B.; Sollmann, N.; Treibel, F.; Weidlich, D.; Baum, T.; Rummeny, E.J.; Zimmer, C.; Kirschke, J.S.; Karampinos, D.C. Improved Brachial Plexus Visualization Using an Adiabatic iMSDE-Prepared STIR 3D TSE. Clin Neuroradiol. 2019, 29, 631–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Harrison, C.; Mariappan, Y.K.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Chhabra, A.; Lenkinski, R.E.; Madhuranthakam, A.J. MR Neurography of Brachial Plexus at 3.0 T with Robust Fat and Blood Suppression. Radiology. 2017, 283, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.Y.; Lin, Y.; Carrino, J.A. An Updated Review of Magnetic Resonance Neurography for Plexus Imaging. Korean J Radiol. 2023, 24, 1114–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

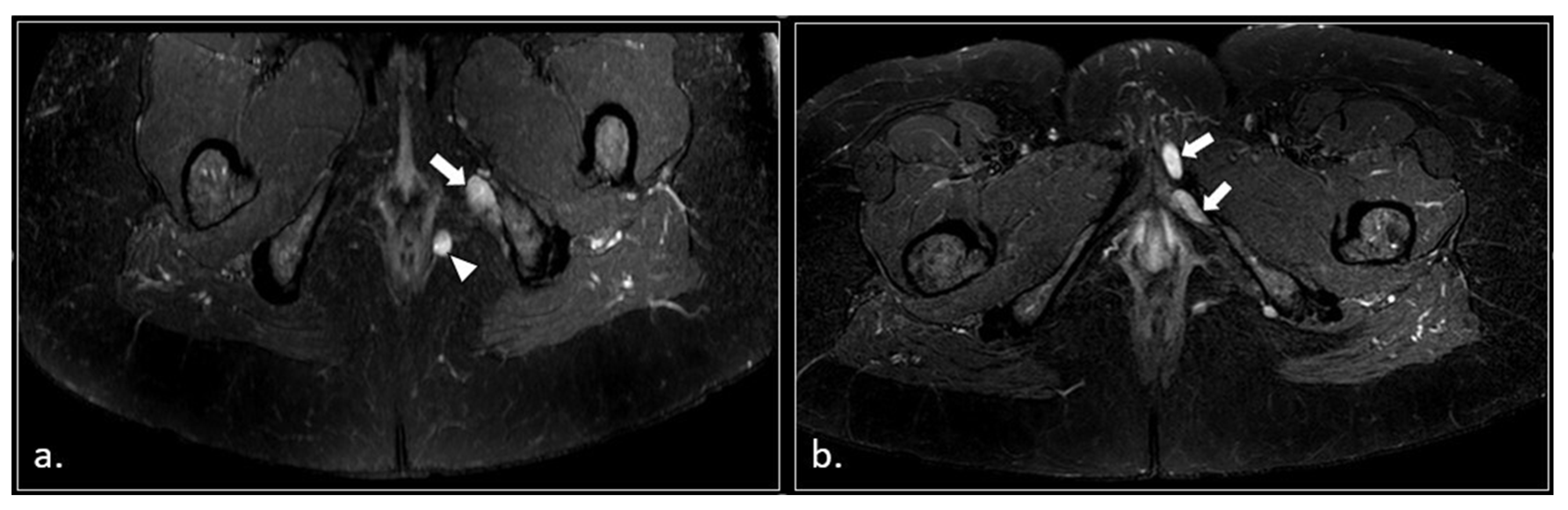

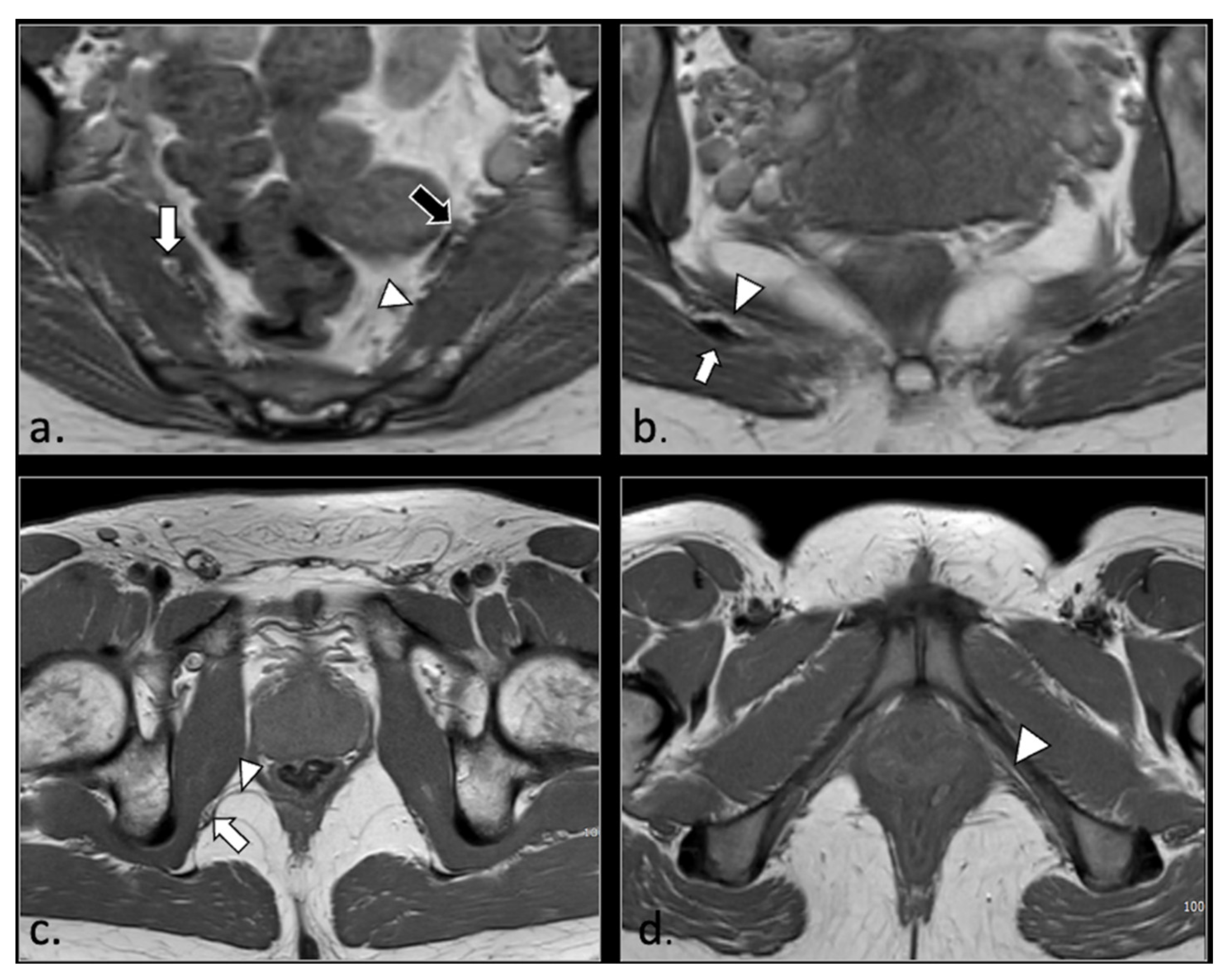

Figure 1.

Representation of the anatomic course of pudendal nerve at four fundamental levels. (a) Axial T1-weighted scan shows trough piriform muscles, lumbo-sacral (black arrow) and pudendal (arrowhead) plexuses of the anterior surface of left piriform muscle. On the right side, the S2 spinal root runs into the piriform muscle (arrow). This anatomic variation can predispose to nerve entrapment and pudendalgia. (b) Axial T1-weighted scan at the extra-pelvic course of the pudendal nerve. The nerve runs in the space between sacro-tuberous ligament posteriorly (arrow) and coccygeal muscle and sacro-spinous ligament (arrowhead) anteriorly. (c) Axial T1-weighted scan at the level of proximal Alcock’s canal. The pudendal neuro-vascular bundle runs close to the obturator internal muscle (arrow). The transverse course of inferior rectal neurovascular bundle can be seen into ischio-rectal fossa (arrowhead). (d) Axial T1-weighted scan at distal Alcock’s canal. At this level, it is difficult to detect the distal branches (arrowhead) of the pudendal nerve.

Figure 1.

Representation of the anatomic course of pudendal nerve at four fundamental levels. (a) Axial T1-weighted scan shows trough piriform muscles, lumbo-sacral (black arrow) and pudendal (arrowhead) plexuses of the anterior surface of left piriform muscle. On the right side, the S2 spinal root runs into the piriform muscle (arrow). This anatomic variation can predispose to nerve entrapment and pudendalgia. (b) Axial T1-weighted scan at the extra-pelvic course of the pudendal nerve. The nerve runs in the space between sacro-tuberous ligament posteriorly (arrow) and coccygeal muscle and sacro-spinous ligament (arrowhead) anteriorly. (c) Axial T1-weighted scan at the level of proximal Alcock’s canal. The pudendal neuro-vascular bundle runs close to the obturator internal muscle (arrow). The transverse course of inferior rectal neurovascular bundle can be seen into ischio-rectal fossa (arrowhead). (d) Axial T1-weighted scan at distal Alcock’s canal. At this level, it is difficult to detect the distal branches (arrowhead) of the pudendal nerve.

Figure 2.

A 24 years-old male with chronic pudendalgia. The onset of pudendalgia could be referred to a sacral trauma. (a) Coronal MRI myelography shows a large Tarlov cyst into the sacral canal (*). (b) Sagittal T1 scan of the lumbar spine demonstrates slight hyperintensity of the cyst, due to chronic hemorrhage (*). (c) Computed Tomography (CT scan) obtained 15 months before MRI examination, at the time of acute trauma, shows acute hemorrhage into the cyst (*) and a Morel Lavallée hematoma (arrow) in the deep subcutaneous tissue of the sacral region. Acute fracture of the sacrum around the cyst could be seen with a bone window (unshown).

Figure 2.

A 24 years-old male with chronic pudendalgia. The onset of pudendalgia could be referred to a sacral trauma. (a) Coronal MRI myelography shows a large Tarlov cyst into the sacral canal (*). (b) Sagittal T1 scan of the lumbar spine demonstrates slight hyperintensity of the cyst, due to chronic hemorrhage (*). (c) Computed Tomography (CT scan) obtained 15 months before MRI examination, at the time of acute trauma, shows acute hemorrhage into the cyst (*) and a Morel Lavallée hematoma (arrow) in the deep subcutaneous tissue of the sacral region. Acute fracture of the sacrum around the cyst could be seen with a bone window (unshown).

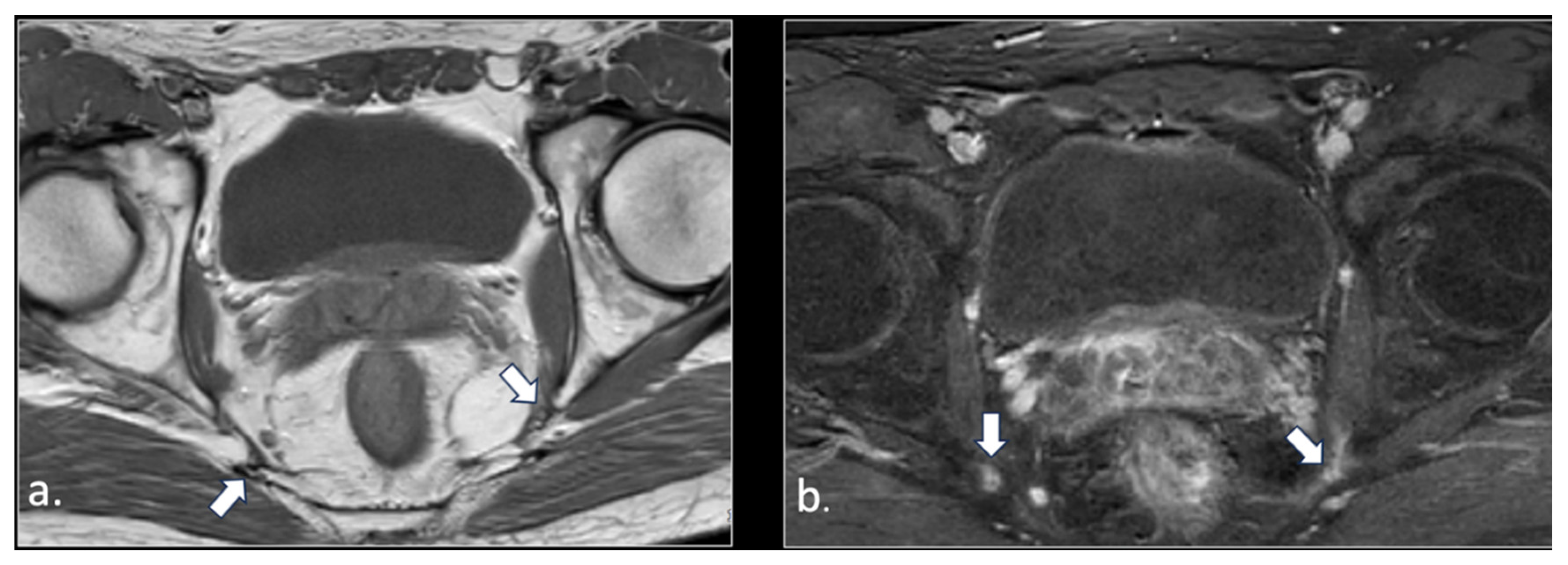

Figure 3.

37-year-old male with pudendal neuralgia. Axial T2-weighted scan through mid-pelvis shows hypertrophy of the left piriformis muscle. Roots of the lumbo sacral plexus lies on the anterior surface of the muscle. On the other hand, S2 and S3 roots of the pudendal plexus (arrow) can be seen along the medial surface of the muscle within an incomplete canal created by the two bellies (* and **) of the muscle.

Figure 3.

37-year-old male with pudendal neuralgia. Axial T2-weighted scan through mid-pelvis shows hypertrophy of the left piriformis muscle. Roots of the lumbo sacral plexus lies on the anterior surface of the muscle. On the other hand, S2 and S3 roots of the pudendal plexus (arrow) can be seen along the medial surface of the muscle within an incomplete canal created by the two bellies (* and **) of the muscle.

Figure 4.

32-year-old man with relapsing pudendalgia after decompressive surgery on both pudendal nerves. (a) Axial T1-weighted image, obtained at the level of ischial spine, shows fibrosis along the extra-pelvic course of both pudendal nerves (arrows). (b) Axial T1-weighted enhanced subtracted scan demonstrates enhancement along the course of the nerves (arrows).

Figure 4.

32-year-old man with relapsing pudendalgia after decompressive surgery on both pudendal nerves. (a) Axial T1-weighted image, obtained at the level of ischial spine, shows fibrosis along the extra-pelvic course of both pudendal nerves (arrows). (b) Axial T1-weighted enhanced subtracted scan demonstrates enhancement along the course of the nerves (arrows).

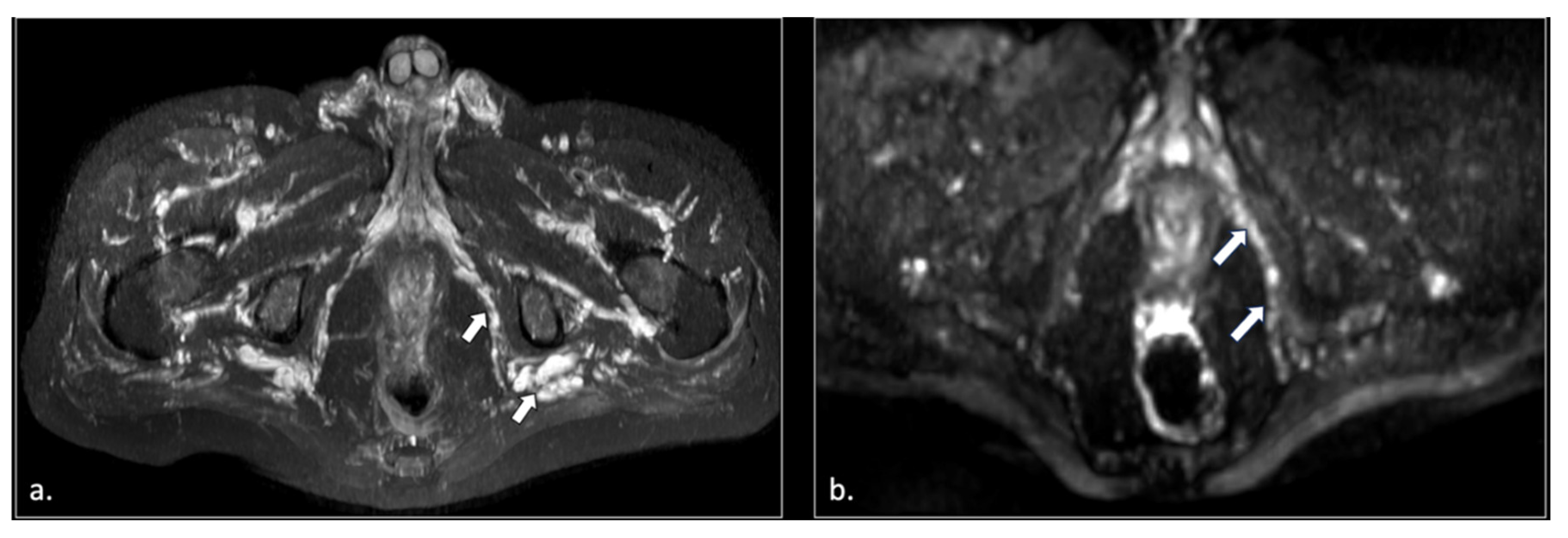

Figure 5.

71-year-old male with chronic pudendalgia. (a) STIR Maximum intensity Projection (MIP) scan shows diffuse venous dilatation of the lower pelvis, including varices of pudendal veins (arrow). (b) b600 DWI Maximum Intensity Projection (MIP) shows enlargement and hyperintensity of the left pudendal nerve (arrow).

Figure 5.

71-year-old male with chronic pudendalgia. (a) STIR Maximum intensity Projection (MIP) scan shows diffuse venous dilatation of the lower pelvis, including varices of pudendal veins (arrow). (b) b600 DWI Maximum Intensity Projection (MIP) shows enlargement and hyperintensity of the left pudendal nerve (arrow).

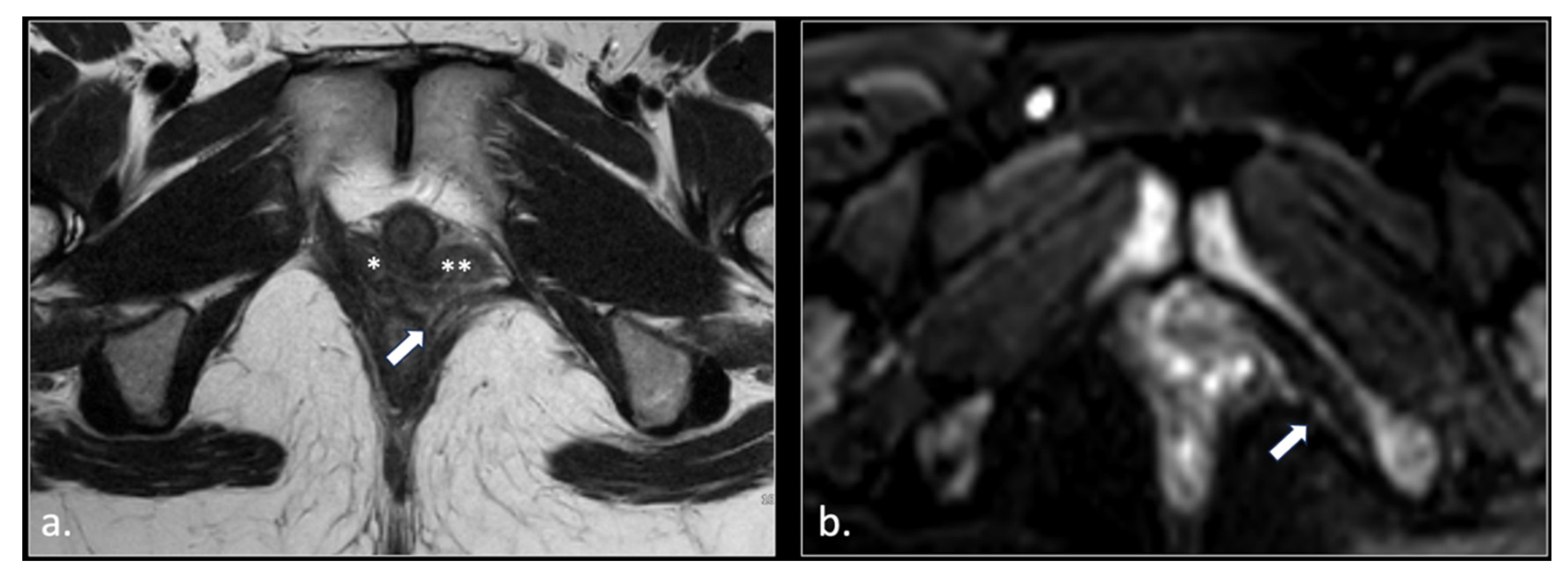

Figure 6.

43-years-old female with chronic post-traumatic pudendalgia. (a) Axial T2-weighted scan shows a normal right side pubo-coccygeus muscle (*). On the left side, an avulsion of the pubo-coccygeus muscle can be seen. The residual left pubo-coccygeus muscle is thinned (arrow). The vagina in shifted on the left side (**). (b) Axial b600 DWI scan demonstrates diffuse hyperintensity of the left pudendal nerve (arrow).

Figure 6.

43-years-old female with chronic post-traumatic pudendalgia. (a) Axial T2-weighted scan shows a normal right side pubo-coccygeus muscle (*). On the left side, an avulsion of the pubo-coccygeus muscle can be seen. The residual left pubo-coccygeus muscle is thinned (arrow). The vagina in shifted on the left side (**). (b) Axial b600 DWI scan demonstrates diffuse hyperintensity of the left pudendal nerve (arrow).

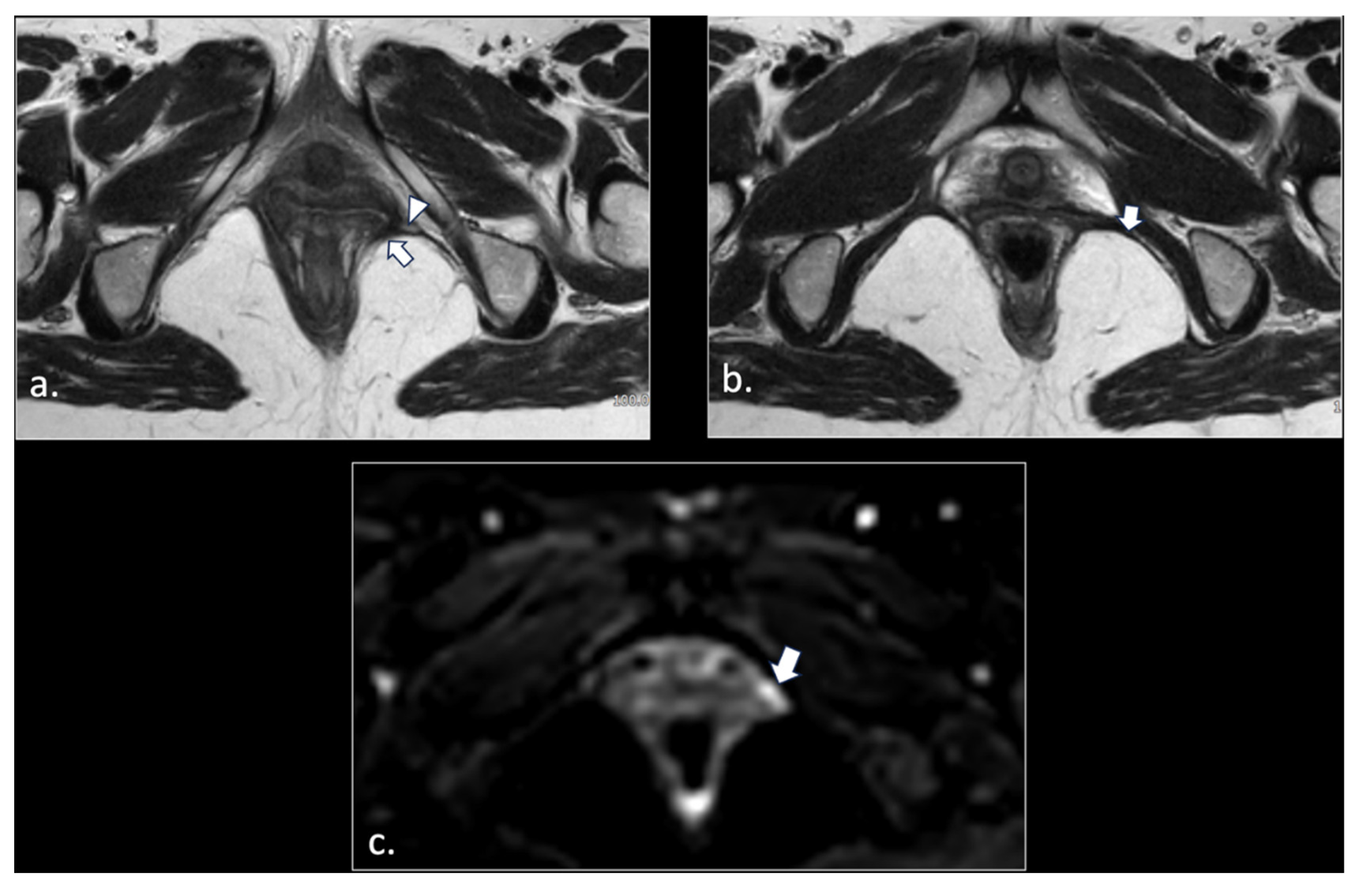

Figure 7.

(a) Axial T2-weigthed section through the distal Alcock’s canal shows an atrophy of the left pubo-coccigeal muscle (arrow) and paravaginal fibrosis on the same side. (b) A more cranial section shows with better advantage the paravaginal fibrosis (arrow); the wall of the vagina is stretched (arrowhead). (c) b600 DWI section, acquired at the same level of (b), shows a strong hyperintensity and enlargement of the left pudendal nerve (arrow).

Figure 7.

(a) Axial T2-weigthed section through the distal Alcock’s canal shows an atrophy of the left pubo-coccigeal muscle (arrow) and paravaginal fibrosis on the same side. (b) A more cranial section shows with better advantage the paravaginal fibrosis (arrow); the wall of the vagina is stretched (arrowhead). (c) b600 DWI section, acquired at the same level of (b), shows a strong hyperintensity and enlargement of the left pudendal nerve (arrow).

Figure 8.

50-years-old female with chronic pudendalgia. (a) STIR Maximum Intensity Projection (MIP) image demonstrates schwannomas of the left pudendal nerve (arrow) and inferior rectal nerve (arrowhead). (b) A lower section shows two schwannomas of the distal branches of the left pudendal nerve (arrow).

Figure 8.

50-years-old female with chronic pudendalgia. (a) STIR Maximum Intensity Projection (MIP) image demonstrates schwannomas of the left pudendal nerve (arrow) and inferior rectal nerve (arrowhead). (b) A lower section shows two schwannomas of the distal branches of the left pudendal nerve (arrow).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).