1. Introduction

Chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) is a prevalent and complex condition resulting from a diverse range of organic and functional disorders that affect both men and women. It is defined as non-malignant, non-cyclical pelvic pain lasting at least six months, often accompanied by cognitive, behavioral, or social challenges.[

1,

2] Women are disproportionately affected, with prevalence rates reaching up to 27%.[

3,

4] Due to its broad symptomatology, CPPS requires multidisciplinary care involving specialists such as gynecologists, urologists, colorectal surgeons, and pain management experts. The lack of universally agreed diagnostic criteria further complicates diagnosis and treatment. By the time the condition is identified, patients frequently undergo numerous diagnostic tests and treatments, leading to worsened severity and chronicity.[

5]

One key contributor to CPPS is pudendal neuropathy, characterized by genital, rectal, and perineal pain, with a reported prevalence of 1% in the general population and up to 20% in women.[

5] The pudendal nerve, originating from the S2, S3, and S4 branches of the sacral plexus, provides sensory and motor innervation to the perineal region.[

6] Pudendal neuralgia often arises from iatrogenic injuries, such as pelvic organ prolapse repair, or from repetitive trauma, including cycling injuries, prolonged sitting, or childbirth.[

7,

8,

9] Chronic constipation, diabetes mellitus, multiple sclerosis, and viral infections are additional potential causes.[

10,

11,

12]

Treatment options for pudendal neuropathy include pharmacologic therapies, physical therapy, and nerve blocks (NB) with perineural steroid injections.[

13,

14,

15,

16] While pharmacologic treatments and physical therapy offer variable benefits, nerve blocks are frequently used for diagnosis and initial management. However, their effectiveness often diminishes with repeated use, and surgical options, such as nerve decompression, carry risks of nerve injury and scarring.[

11,

17] These limitations underscore the need for alternative therapeutic approaches.

Pulsed radiofrequency ablation (pRFA) has emerged as a promising minimally invasive treatment for refractory pudendal neuralgia. Unlike traditional ablative therapies, which can cause permanent nerve damage, pRFA uses intermittent high-intensity current to modulate aberrant nerve signals without overheating the nerve, preserving function and allowing repeat procedures if needed.[

18,

19,

20,

21,

22] Evidence suggests pRFA is effective for various neuropathies, including pudendal neuralgia, as demonstrated in case reports and pilot studies.[

23,

24,

25]

A previous randomized trial by Wang et al. compared pRFA in 38 patients to steroid injections, demonstrating a clinical effectiveness rate of 92.1% for pRFA versus 35.9% for nerve blocks at three months.[

26] However, the study’s generalizability is limited due to regional differences in patient demographics and lifestyle factors. To bridge this gap, our study evaluates CT-guided pRFA in a consecutive patient cohort with extended follow-up, hypothesizing that pRFA offers superior and sustained outcomes compared to steroid injections for chronic refractory pudendal neuralgia.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

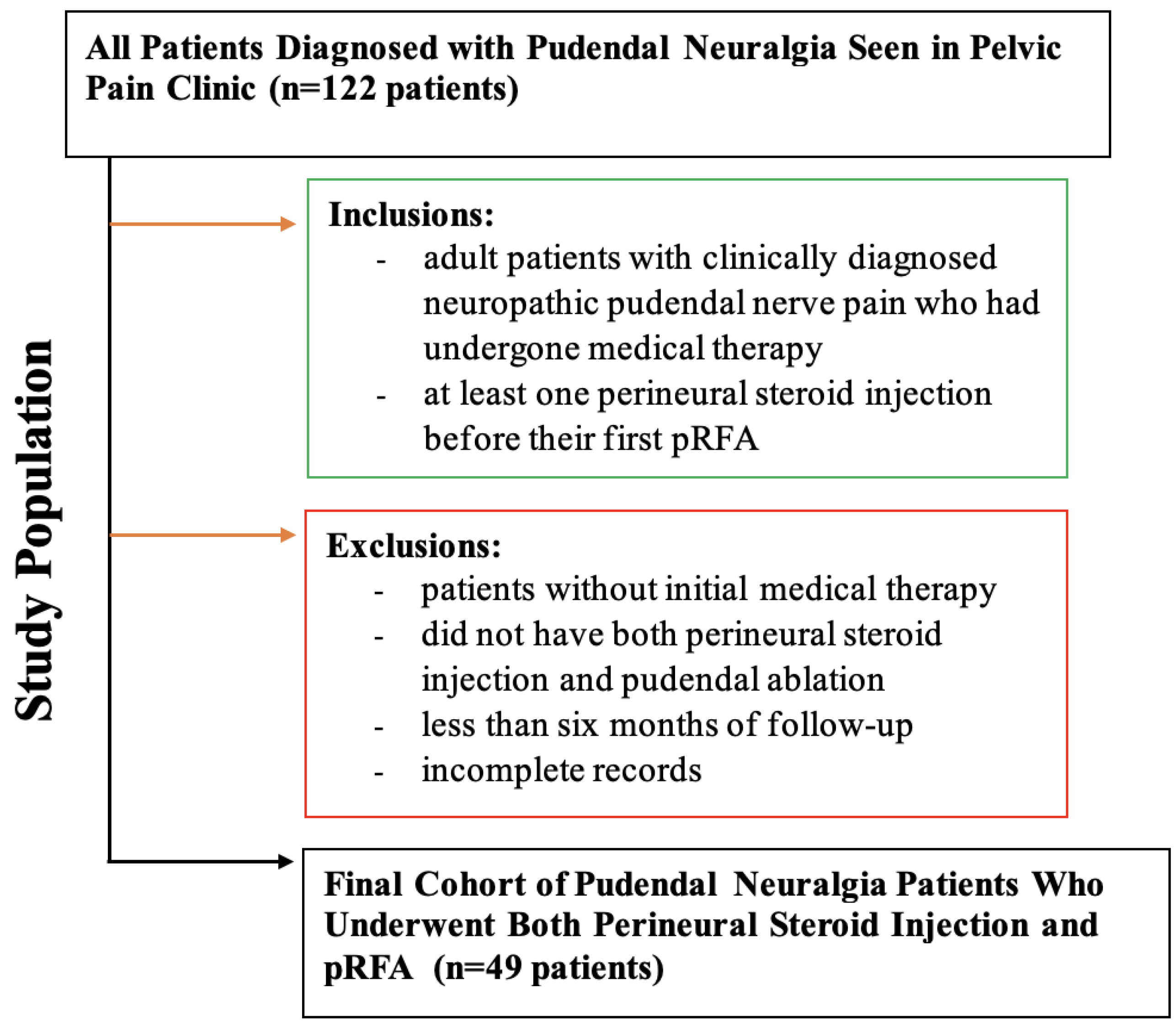

This retrospective cross-sectional study, approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) with a waiver of informed consent, analyzed a consecutive cohort of patients who underwent pudendal nerve pulsed radiofrequency ablation at a single tertiary care hospital, based on electronic health record chart reviews from April 2016 to August 2024.Patients were referred by physical medicine and rehabilitation physicians from a pelvic pain clinic, and the diagnoses were based on multiple criteria, including clinical findings of pudendal neuralgia, previous response to pelvic floor therapy and perineural steroid injection. All participants had previously received medical therapy and magnetic resonance neurography (MRN) of the lumbosacral plexus.

The inclusion criteria were adult patients (≥ 18 years) of all genders, clinically diagnosed with pudendal neuralgia, having received medical therapy and at least one injection before their first pRFA. Exclusion criteria included patients who did not undergo initial medical therapy, patients with less than six months of follow-up post-procedure, and those with incomplete electronic health records. Selection methodology can been illustrated in

Figure 1.

2.2. CT-guided Procedures.

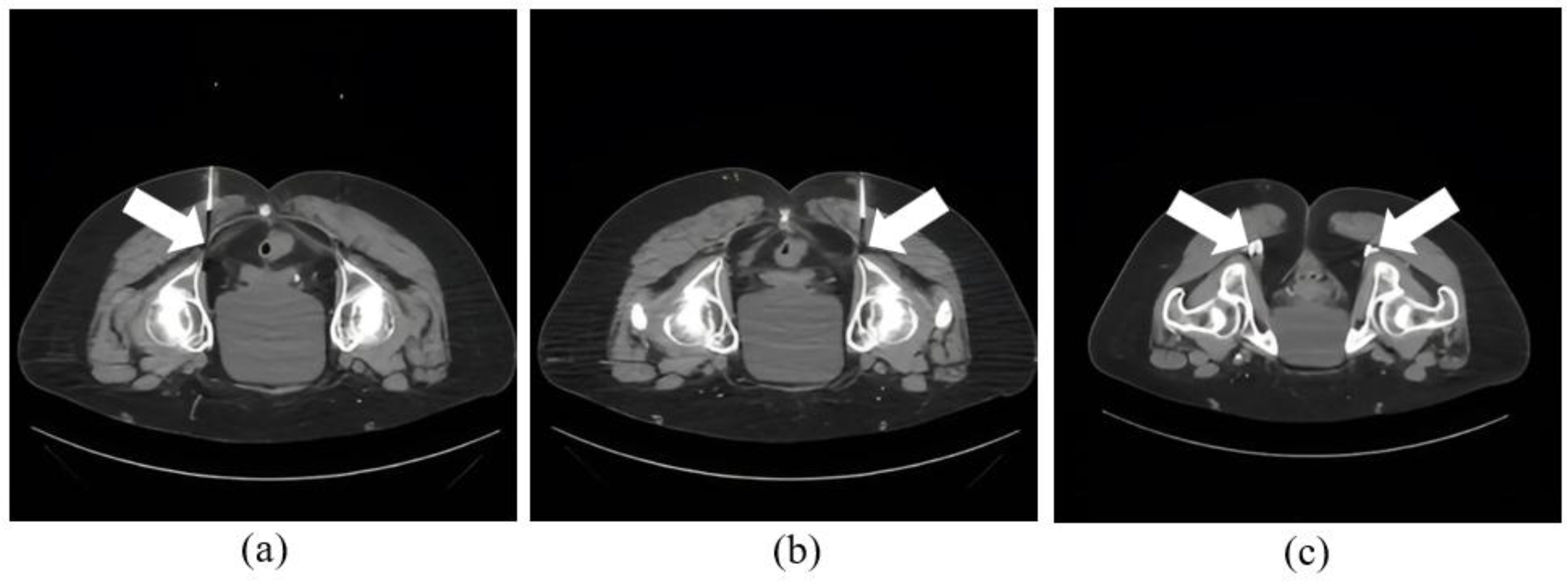

All ablation procedures followed a standardized intervention process. A procedural nurse brought the patient to the CT suite, attached them to cardiac and oxygen monitoring, placed the patient in a prone position, and completed a pre-procedural timeout. The procedures were performed under CT guidance and conscious sedation, with use of CT fluoroscopy. All pRFA procedures used the Neurotherm 2000iX Radiofrequency Generator (St Jude Medical, Saint Paul, MN). Thereafter, needle placement was planned using an initial CT guidance with radiopaque markers. Superficial anesthesia is administered with 1% lidocaine. Next, the operator placed a 22 G coaxial needle terminating next to the pudendal nerve in Alcock’s canal, under intermittent CT guidance. The location of pudendal nerve was ascertained as the most posterior structure in the pudendal neurovascular bundle under the sacrotuberous ligament with visualization of fascicular architecture and intermediate density (related to endoneurial fluid) than the adjacent slightly brighter or calcified vessel (due to hematocrit effect). CT localization was then used to confirm the needle tip placement, through injection of 1 ml of a 1:5 dilution of Isovue 200 iodinated contrast medium (

Figure 2). Subsequently, ablation was conducted with ablation probes advanced into the needles followed by sensory and motor stimulation testing at 2V-3V. Following this, pRFA was performed at 42°C for 120 seconds (

Figure 3). Then, the perineural space was injected with a 5 ml solution consisting of 2 ml 1% lidocaine, 2 ml 0.5% bupivacaine, and 1 ml dexamethasone 4 mg/ml like what patients had received previously as perineural injection alone using the same CT-guidance.

The procedure duration averaged 94 ± 46 minutes from patient arrival at CT to patient departure to the recovery area, which included setting up sedation, and time out, etc. The time from needle insertion for pudendal ablation and injection to needle removal ranged from 5-10 minutes.

Of the 49 patients receiving treatment, 46 underwent procedures with moderate sedation using fentanyl and midazolam, titrated for patient comfort, and continuously monitored by a procedural nurse. Two patients chose to forego sedation based on personal preference, and one patient with allergies to opiate medications received only midazolam. All patients reported comfort throughout the procedure, with an average administration of 83 ± 58 µg fentanyl and 1.2 ± 0.76 mg midazolam per procedure.

All procedures were considered technically successful, defined by the correct anatomical placement of the introducer needle, confirmed by pre-ablation injection of dilute water-soluble iodinated contrast, and achieving peak ablation temperatures of 42-43°C for a total duration of two minutes. No immediate complications were reported. Demographic data, clinically relevant history, imaging studies, and details of medical and surgical therapy were abstracted from patients' medical records. Ablation of respective pudendal nerves can be seen in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3.

2.3. Follow-Ups

The response to pRFA therapy was assessed using retrospective chart reviews and prospective telephone questionnaires, including the validated 10-point Visual Analog Scale (VAS) to measure pain severity. Pain scores, self-reported on pain response sheets and phone interviews, were evaluated post-ablation at 4 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months follow-ups as a standardized procedure. The duration of pain relief, defined as the time from the procedure to the return of pain, was also recorded, with the lowest pain score experienced during each duration noted.

For patients who underwent more than one pRFA, the procedures were ordered by their respective dates. Data on analgesic use before and after pRFA and perceived quality of life changes were collected at 4 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months post-procedure.

2.4. Statistics

Statistical analysis was conducted by a faculty statistician. Pain relief durations were compared between the first injection, last injection, and pRFA using a linear mixed model controlling for within-patient clustering, with log (duration+1) transformation applied to adjust for right skewness. Ad-hoc multiple comparisons between first, last, and pRFA were performed with Tukey adjustment, with similar analysis for the lowest pain scores. The time between pain onset and the date of pRFA was correlated with the best pain score and pain relief durations using Pearson correlation coefficient, considering a p-value of 0.05 as statistically significant. All statistical analyses, including ANOVA, chi-square tests, and Student's t-test, were performed using Prism GraphPad software.

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

Of the 122 patients diagnosed with pudendal neuralgia at our institutional pelvic pain clinic, inclusion criteria required adult patients with a clinical diagnosis who had undergone medical therapy and received at least one perineural steroid injection prior to their first pRFA. Exclusion criteria eliminated patients without prior medical therapy (n=28), those missing both interventions (n=19), follow-up < 6 months (n=20), or incomplete records (n=11). Ultimately, 49 patients met all criteria (follow-up ≥ 6 months), forming the final cohort for analysis.

3.2. Demographics

In this study, 49 patients with pudendal neuralgia underwent a total of 186 procedures, which included both initial and repeat perineural steroid injections as well as initial and subsequent pulsed radiofrequency ablations, with average follow up of 8.82 ± 2.39 months. The cohort had an average age of 61.7 ± 14.1 years and an average BMI of 26.3 ± 4.90; 30 participants were female, and 19 were male. Of these, 31 patients underwent one ablation, 13 had two ablations, 6 received three ablations, and 2 patients with recalcitrant pain underwent four ablations over six years. The most recent pain exacerbation prior to pRFA had persisted for an average of 8.12 ± 1.34 months. All patients were previously treated with at least one prior CT-guided perineural injection consisting of local anesthetic and corticosteroid, with an average of 2.10 ± 1.65 prior injections per nerve (range 1–8).

Pre-procedure MR neurography findings were available for all 49 patients. Among these, 51.0% (n=25) demonstrated no significant abnormalities. Nerve thickening or asymmetry of the pudendal nerve was observed in 16.3% (n=8), and T2 hyperintensity, indicative of inflammation or edema, was seen in 12.2% (n=6). Scarring or fibrosis around Alcock’s canal, potentially contributing to nerve compression, was noted in 18.4% (n=9) and atrophy of the surrounding pelvic musculature was identified in 26.5% (n=13) of patients.

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3 further outline patient characteristics.

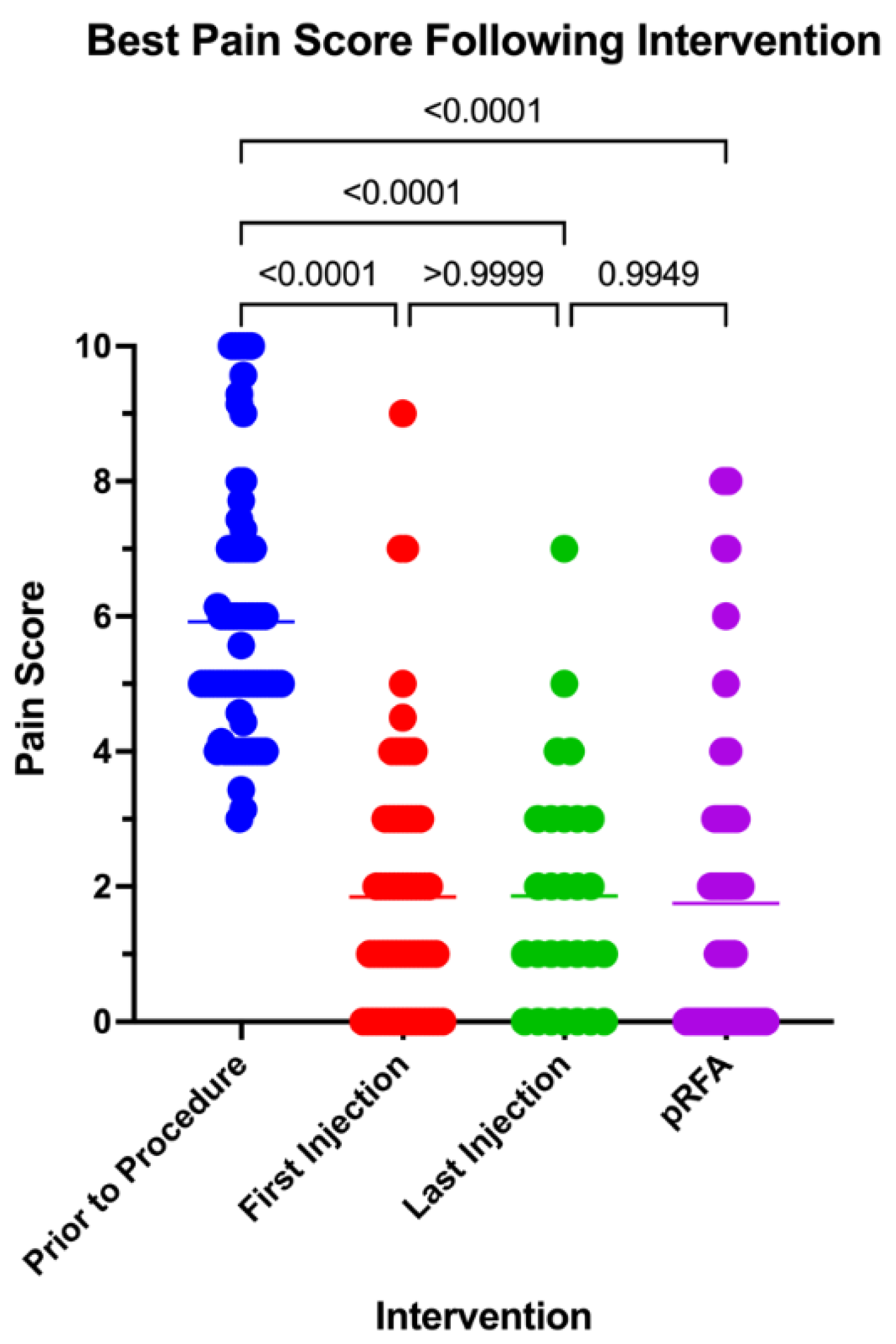

3.3. Pain Response

The initial pain scores, averaging 5.92 ± 2.78 prior to the procedures, were compared to the lowest pain scores recorded after the first and last injections, as well as the patient's overall lowest post-procedure pain score. All comparisons revealed statistically significant reductions in pain across procedures (P < 0.0001) (supplementary figure 1). The average pain score was compared to lowest pain score following pRFA was found to be slightly lower than first and most recent therapeutic injections, with post pRFA pain score average of 1.75 ± 2.21 compared to 1.85 ± 3.54 after the first injection and 1.64 ± 1.73 after the most recent injection. These differences, however, did not reach statistical significance, with p-values of 0.992 for pRFA compared to the first injection and p=0.995 for pRFA compared to the most recent injection

Figure 4.

Best Pain Score Following First Injection, Most Recent Injection, and pRFA Compared to Pre-Intervention Pain Score.

Figure 4.

Best Pain Score Following First Injection, Most Recent Injection, and pRFA Compared to Pre-Intervention Pain Score.

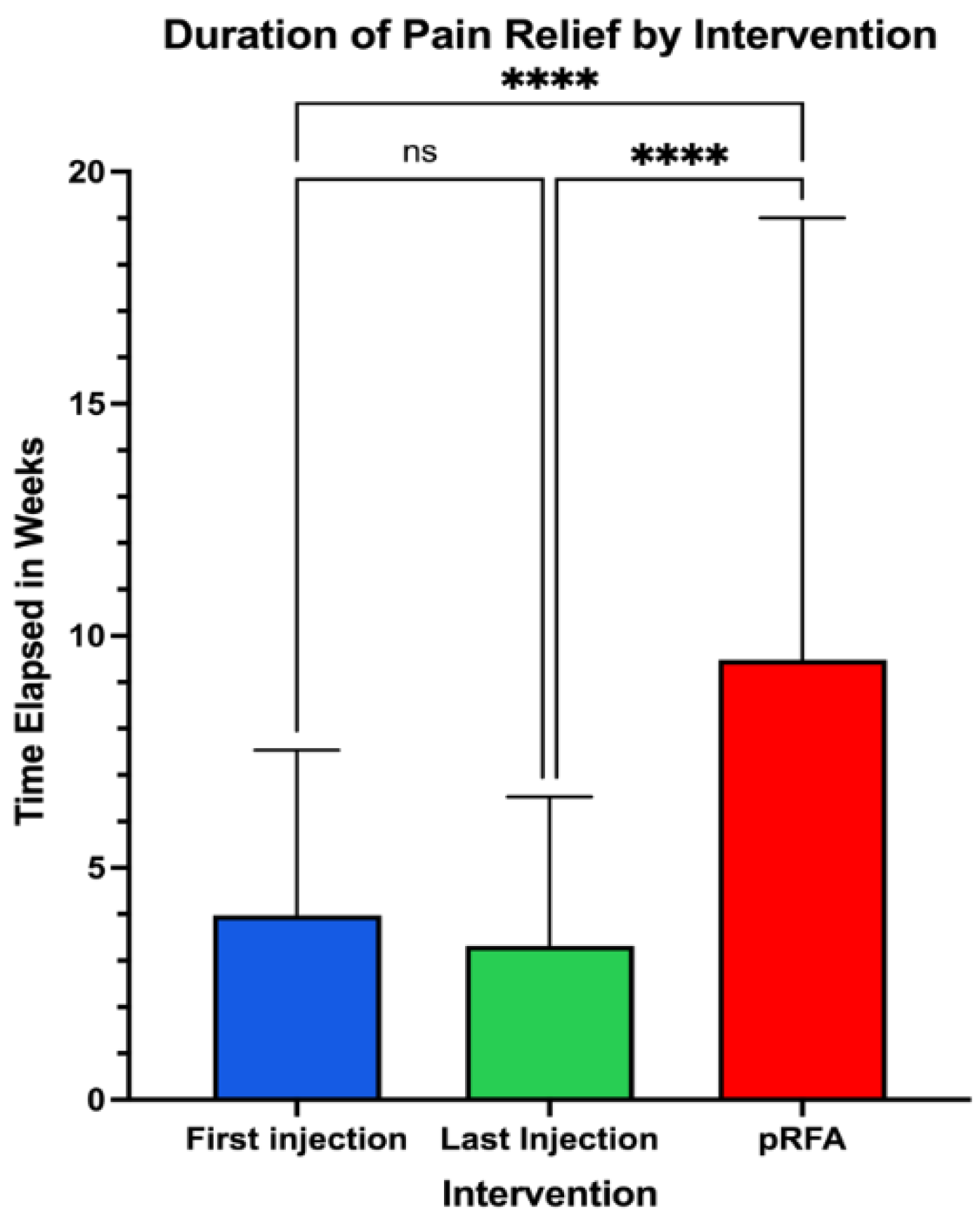

3.4. Duration of Response

The duration of improvement in pain symptoms was then compared, evaluating the post-procedural pain scores at subsequent follow up over a period of at least 6 months per patient (

Figure 2). Following pRFA, pain scores remained improved for 9.48 ± 9.52 weeks, compared to 3.98 ± 3.56 weeks for the first perineural injection and 3.32 ± 3.21 weeks for the most recent injection. The reported length of time for pain improvement with pRFA was significantly longer than that for the most initial injection (p<0.0001) and most recent injection (p<0.0001).

Figure 5.

Pain Relief Duration Comparing First Injection, Last Injection, and pRFA.

Figure 5.

Pain Relief Duration Comparing First Injection, Last Injection, and pRFA.

3.5. Quality of Life

A total of 36 patients had documented subjective scores pertaining to quality-of-life following pRFA up to 6 months. Quality of life scores were measured at 4 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months using patients’ questionnaires on subsequent follow up using Likert scales out of 10 with 10 being an improved sense of function, pain tolerance, and overall comfort compared to prior to the most recent procedure. Significant increases in quality-of-life scores were noted at the 4-week, 6-week, and 3-month time points with a non-significant increase sustained at the 6-month time point (p=0.0001, p=0.0003, p=0.0016, p=0.0726, respectively).

Figure 6.

Reported Quality Of Life Score Improvements Over Time Following pRFA.

Figure 6.

Reported Quality Of Life Score Improvements Over Time Following pRFA.

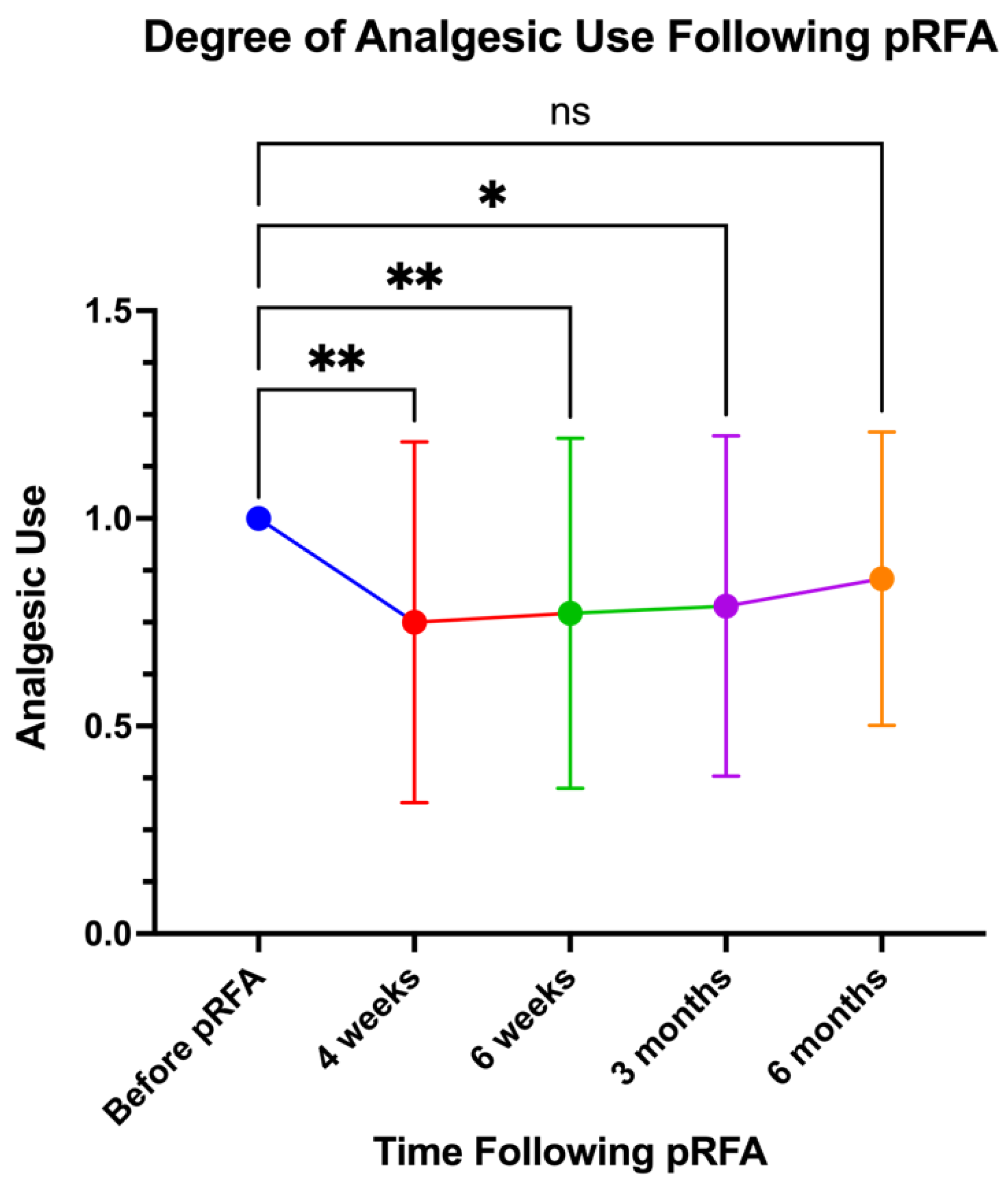

3.6. Analgesic Use

Likewise, 33 patients had documented scores related to their analgesic use following pRFA for up to six months. They were asked if there was a reduction in the frequency of painkiller and topical analgesic use at 4 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months. This was assessed using patient questionnaires with Likert scales ranging from 0 to 2, where 0 indicated no need for analgesics, 1 indicated continued use of their pre-procedure regimen, and 2 indicated a doubling of analgesic need. Significant decreases in scores were observed at the 4-week, 6-week, and 3-month time points with the 6-month time point showing a non-significant decrease in analgesic use (p=0.0014, p=0.0045, p=0.0110, p=0.1683 respectively).

Figure 7.

Reported Analgesic Use Over Time Following pRFA.

Figure 7.

Reported Analgesic Use Over Time Following pRFA.

3.7. Correlations

There was a variable time gap between when patients first reported experiencing their current symptoms as well as their duration of pain until their first perineural injection and first pRFA. The duration of time during which the patient experienced their initial symptoms leading up to their treatments was compared to the quantity and duration of pain relief. Pearson correlation testing found that there was no significant correlation between the time from the beginning of pain symptoms to the time of pRFA regarding pain score, r=0.11 (p=0.68), or the duration of pain relief, r=0.06 (p=0.87). Furthermore, no significant correlation was found for the time between the last perineural injection and the first pRFA regarding pain score, r=0.14 (p=0.72), or the duration of pain relief, r= –0.18 (p=0.75).

3.8. Complications

In terms of complications, of the 49 patients who underwent the study, 9 developed unintended symptoms that were partially or fully resolved within days of the procedure. Three patients experienced prolonged mild numbness in the perineal region, which was resolved within 3-4 days. Four patients reported soreness at the injection site, subsiding within 3–5 days with conservative management. Two patients experienced transient changes in bowel or bladder function, including mild urgency or difficulty, which were fully resolved within one week. These self-limiting symptoms required no additional interventions/revisions and resolved with symptomatic treatment.

4. Discussion

Our study demonstrates that pulsed radiofrequency ablation is an effective therapeutic option for managing chronic pudendal neuralgia, significantly improving both pain relief and quality of life. Among the 49 patients analyzed, the mean duration of pain relief following pRFA was 9.48 ± 9.52 weeks, which was substantially longer than the relief observed after the first (3.98 ± 3.56 weeks, p < 0.0001) and most recent perineural steroid injections (3.32 ± 3.21 weeks, p < 0.0001). Additionally, patients experienced significant quality-of-life improvements at 4 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months post-pRFA (p = 0.0014, p = 0.0045, p = 0.0110, respectively) and a corresponding reduction in analgesic use during these time points. Notably, the outcomes were consistent regardless of the severity or duration of symptoms prior to treatment.

Previously, perineural steroid injections and nerve blocks widely represented first-line interventions for managing pelvic neuropathy. While these modalities often provide substantial initial analgesia, their therapeutic efficacy tends to wane rapidly over successive administrations.[

27] This attenuation of benefit not only diminishes pain control but may also exacerbate disease progression, presenting a clinical challenge for long-term management. In response to these limitations, pulsed radiofrequency ablation has emerged as a compelling alternative, demonstrating distinct advantages over traditional steroid injections and continuous RFA.[

28,

29,

30] Technological advancements in imaging, including CT have further enhanced the precision of pRFA interventions leading to almost 100% technical success, making it a preferable option for ongoing pain management.[

25]

Our findings corroborate and expand upon the findings of previous research, demonstrating the superiority of pRFA over steroid injections alone in terms of pain relief duration. In a previously published small case series on pudendal neuralgia by Collard et al., the results of their pilot study showed similar results, i.e. pRFA significantly improved the duration of pain relief compared to the most recent perineural injection (p=0.0195), though not significantly different from the initial injection (p=0.64).[

25] Pain scores were lower with pRFA than with both the first and most recent injections, but these differences did not reach statistical significance (p=0.1094 and p=0.7539, respectively). In a long-term follow-up study by Krinjen involving 20 patients with a median follow-up of 4 years, 430 pRFA treatments were performed.[

23] Of the 18 patients who underwent multiple treatments, 79% reported their condition as "very much better" or "much better" at the 3-month follow-up, and this improvement persisted at long-term follow-up. The same 79% maintained their positive assessments, while only one patient reported a "much worse" condition at 3 months and did not receive further pRFA. The success rate of repeated pRFA was 89% at long-term follow-up, highlighting its effectiveness for sustained pain management. These results are comparable to the findings of Fang et al. in a randomized controlled trial, which included 77 patients with pudendal neuralgia.[

31] In this trial, patients were divided into two groups: 38 patients received pRFA with a pudendal nerve block and 39 patients in the control group received only nerve block with local anesthetics. The clinical effective rate was 92.1% in the pRFA group, compared to 35.9% in the NB group at 3 months follow-up.

While our study has contributed important insights, several limitations merit attention. Our research utilized repeated measures study design, lacking a control group, which relied on subjective patient reported data to confer results. Our study's reliance on patient-reported outcomes without the incorporation of objective pain measurement techniques could skew the data, introducing possible bias in patient reported outcomes. The potential for a placebo effect remains unaddressed. Additionally, the study did not benefit from a lengthy follow-up period, as data collection was limited to the six-month post-procedure time frame. These factors limit our ability to generalize the results across diverse patient populations and longer durations. Considering these issues, future research should aim for a more rigorous design, involving a larger, multicenter approach with both objective measures and an extended follow-up period.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, our study highlights the effectiveness of pRFA in managing pudendal neuralgia with improvements in pain relief, quality of life, and reduced analgesic use. Pain relief lasted an average of 9.48 weeks post-pRFA, significantly longer than corticosteroid injections. Outcomes were consistent regardless of the severity or duration of prior symptoms, demonstrating the broad applicability of pRFA. These findings support pRFA as a valuable treatment option for patients with pudendal nerve pain.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C., F.D.S., R.K., and K.S.; methodology, Z.Z., Y.X., and A.C.; software, Y.X. and Z.Z.; validation, Y.X., Z.Z., S.A., and M.W.; formal analysis, Y.X. Z.Z.; investigation, Z.Z., S.A., M.W., and H.S.; resources, A.C. data curation, Z.Z., S.A., and H.S.; writing—original draft preparation, Z.Z., A.C., S.A.; writing—review and editing, Z.Z., A.C., M.W., K.S., and R.K.; visualization, Z.Z.; supervision, A.C., K.S., and R.K.; project administration, Z.Z. and A.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (protocol code STU-2022-0281, approved on March 21, 2022). Ethical review and approval included a waiver of informed consent due to the retrospective nature of the study and minimal risk to participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study, minimal risk to participants, and the use of de-identified data, as approved by the Institutional Review Board. Written informed consent was not required for publication as no identifiable patient information is presented.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions but may be provided by the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with Institutional Review Board approval.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the administrative and technical support provided by the Department of Radiology and the Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation at UT Southwestern Medical Center.

Conflicts of Interest

A.C. reports the following disclosures: Consultant for ICON Medical and TREACE Medical Concepts Inc.; book royalties from Jaypee and Wolters; speaker for TMC Academy; medical advisor for IBL, Inc.; and research grants from IBL, Inc. and Qure-AI. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| cRFA |

Continuous Radiofrequency Ablation |

| VAS |

Visual Analog Scale |

| MRN |

Magnetic Resonance Neurography |

| CT |

Computed Tomography |

| RFA |

Radiofrequency Ablation |

| IRB |

Institutional Review Board |

| HIPAA |

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act |

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| QoL |

Quality of Life |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of Variance |

| PRF |

Pulsed Radiofrequency |

| RFN |

Radiofrequency Neurotomy |

References

- A standard for terminology in chronic pelvic pain syndromes: A report from the chronic pelvic pain working group of the international continence society - PubMed, (n.d.). https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.foyer.swmed.edu/27564065/ (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- S. Kothari, Neuromodulatory approaches to chronic pelvic pain and coccygodynia, Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 97 (2007) 365–371. [CrossRef]

- P. Latthe, M. P. Latthe, M. Latthe, L. Say, M. Gülmezoglu, K.S. Khan, WHO systematic review of prevalence of chronic pelvic pain: a neglected reproductive health morbidity, BMC Public Health 6 (2006) 177. [CrossRef]

- Prevalence of chronic pelvic pain among women: an updated review - PubMed, (n.d.). https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.foyer.swmed.edu/24658485/ (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- C.W. Hunter, B. C.W. Hunter, B. Stovall, G. Chen, J. Carlson, R. Levy, Anatomy, Pathophysiology and Interventional Therapies for Chronic Pelvic Pain: A Review. Pain Physician 2018, 21, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafik, M. el-Sherif, A. Youssef, E.S. Olfat, Surgical anatomy of the pudendal nerve and its clinical implications, Clin. Anat. N. Y. N 8 (1995) 110–115. [CrossRef]

- J. Kaur, S.W. J. Kaur, S.W. Leslie, P. Singh, Pudendal Nerve Entrapment Syndrome, in: StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544272/ (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- [R. Robert, D. [R. Robert, D. Prat-Pradal, J.J. Labat, M. Bensignor, S. Raoul, R. Rebai, J. Leborgne, Anatomic basis of chronic perineal pain: role of the pudendal nerve, Surg. Radiol. Anat. SRA 20 (1998) 93–98. [CrossRef]

- The vicious cycling: bicycling related urogenital disorders - PubMed, (n.d.). https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.foyer.swmed.edu/15716187/ (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- K.-C. Lien, D.M. K.-C. Lien, D.M. Morgan, J.O.L. Delancey, J.A. Ashton-Miller, Pudendal nerve stretch during vaginal birth: a 3D computer simulation, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 192 (2005) 1669–1676. [CrossRef]

- S.W. Leslie, S. S.W. Leslie, S. Antolak, M.P. Feloney, T.L. Soon-Sutton, Pudendal Neuralgia, in: StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562246/ (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- C.E. Ramsden, M.C. C.E. Ramsden, M.C. McDaniel, R.L. Harmon, K.M. Renney, A. Faure, Pudendal nerve entrapment as source of intractable perineal pain. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2003, 82, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuropathic pain in adults: pharmacological management in non-specialist settings, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), London, 2020. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK552848/ (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- Pharmacotherapy for neuropathic pain in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis - PubMed, (n.d.). https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.foyer.swmed.edu/25575710/ (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- Levesque, E. Bautrant, V. Quistrebert et al, Recommendations on the management of pudendal nerve entrapment syndrome: A formalised expert consensus, Eur. J. Pain Lond. Engl. 26 (2022) 7–17. [CrossRef]

- G. Basol, A. G. Basol, A. Kale, H. Gurbuz, E.C. Gundogdu, K.N. Baydilli, T. Usta, Transvaginal pudendal nerve blocks in patients with pudendal neuralgia: 2-year follow-up results, Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 306 (2022) 1107–1116. [CrossRef]

- Waxweiler, S. Dobos, V. Thill, L. Bruyninx, Selection criteria for surgical treatment of pudendal neuralgia, Neurourol. Urodyn. 36 (2017) 663–666. [CrossRef]

- Radiofrequency Ablation - StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf, (n.d.). https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.foyer.swmed.edu/books/NBK482387/ (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- Bladder Dysfunction and Pelvic Pain: The Role of Sacral, Tibial, and Pudendal Neuromodulation | SpringerLink, (n.d.). https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-031-19598-3_15 (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- Neuropathic Pain: A Maladaptive Response of the Nervous System to Damage - PMC, (n.d.). https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC2768555/ (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- H. Wu, J. H. Wu, J. Zhou, J. Chen, Y. Gu, L. Shi, H. Ni, Therapeutic efficacy and safety of radiofrequency ablation for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis, J. Pain Res. 12 (2019) 423–441. [CrossRef]

- Association Between Radiofrequency Rhizotomy Parameters and Duration of Pain Relief in Trigeminal Neuralgia Patients with Recurrent Pain - PubMed, (n.d.). https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.foyer.swmed.edu/31102773/ (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- E.A. Krijnen, K.J. E.A. Krijnen, K.J. Schweitzer, A.J.M. van Wijck, M.I.J. Withagen, Pulsed Radiofrequency of Pudendal Nerve for Treatment in Patients with Pudendal Neuralgia. A Case Series with Long-Term Follow-Up, Pain Pract. Off. J. World Inst. Pain 21 (2021) 703–707. [CrossRef]

- Petrov-Kondratov, A. Chhabra, S. Jones, Pulsed Radiofrequency Ablation of Pudendal Nerve for Treatment of a Case of Refractory Pelvic Pain, Pain Physician 20 (2017) E451–E454.

- M.D. Collard, Y. M.D. Collard, Y. Xi, A.A. Patel, K.M. Scott, S. Jones, A. Chhabra, Initial experience of CT-guided pulsed radiofrequency ablation of the pudendal nerve for chronic recalcitrant pelvic pain, Clin. Radiol. 74 (2019) 897.e17-897.e23. [CrossRef]

- The Clinical Efficacy of High-Voltage Long-Duration Pulsed Radiofrequency Treatment in Pudendal Neuralgia: A Retrospective Study - PubMed, (n.d.). https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.foyer.swmed.edu/33945192/ (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- R.V. Sondekoppam, B.C.H. R.V. Sondekoppam, B.C.H. Tsui, Factors Associated With Risk of Neurologic Complications After Peripheral Nerve Blocks: A Systematic Review, Anesth. Analg. 124 (2017) 645–660. [CrossRef]

- Pulsed Versus Conventional Radio Frequency Ablation for Lumbar Facet Joint Dysfunction | Current Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Reports, (n.d.). https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40141-013-0040-z (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- Radiofrequency Ablation and Its Role in Treating Chronic Pain, ASRA Pain Med. (n.d.). https://www.asra.com/news-publications/asra-newsletter/newsletter-item/asra-news/2020/08/01/radiofrequency-ablation-and-its-role-in-treating-chronic-pain (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- Use of Pulsed Radiofrequency in Clinical Practice, MedCentral (2012). https://www.medcentral.com/pain/chronic/use-pulsed-radiofrequency-clinical-practice (accessed , 2024). 23 December.

- H. Fang, J. Zhang, Y. Yang, L. Ye, X. Wang, Clinical effect and safety of pulsed radiofrequency treatment for pudendal neuralgia: a prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 2367–2374. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).