1. Introduction

Infertility represents a global health challenge, affecting an estimated 10-15% of couples of reproductive age worldwide [

1]. While in vitro fertilization (IVF) programs have achieved considerable advancements in addressing infertility – through optimized embryo culture conditions [

2,

3], refined morphological and molecular criteria for quality assessment [

4], and improved selection of the optimal developmental stage for uterine transfer [

5,

6] – pregnancy rates remain suboptimal. According to data from the Russian Association of Human Reproduction, success rates in IVF cycles do not exceed 30-49% [

7]. It is well-established that over half of early pregnancy losses are associated with aneuploid embryos [

8]. Moreover, the incidence of embryos with chromosomal aberrations exhibits a strong correlation with maternal age. The proportion of aneuploid embryos rises from 20-27% in women aged 26–30 years to as high as 95.5% in women aged 45 years [

9,

10]. Considering the contemporary trend toward delayed childbearing, the preimplantation identification of chromosomally abnormal embryos is of paramount importance.

The current clinical standard for assessing embryonic ploidy is invasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (iPGT-A) [

11]. This technique necessitates trophectoderm biopsy for chromosomal copy number variation analysis, an invasive procedure that induces mechanical stress on embryonic cells. This stress manifests as DNA budding and shedding from nuclei, significantly exceeding the levels observed during physiological blastocoel expansion and hatching [

12]. Consequently, the biopsy procedure itself may contribute to the occurrence of mosaic aneuploidy, in addition to errors in mitotic chromosome segregation. Furthermore, a multicenter randomized clinical trial [

13] demonstrated no significant improvement in live birth rates per transfer among women aged 25–40 years following the transfer of a euploid embryo selected via iPGT-A, compared to selection based solely on morphological criteria (50% vs. 46%; p = 0.32). This finding implies that the blastocyst's capacity for endometrial apposition, adhesion, and invasion is governed not only by cellular ploidy but also by a multitude of critical molecular mechanisms originating from both the blastocyst and the maternal endometrium, which collectively orchestrate a successful embryo-endometrial dialogue [

14,

15].

A principal limitation of iPGT-A is its inability to reliably distinguish between uniformly aneuploid and mosaic embryos. Evidence suggests that a subset of embryos diagnosed as aneuploid or mosaic by iPGT-A can result in the birth of healthy, euploid infants [

16,

17,

18], likely because the biopsy of 5–6 trophectoderm cells may not be representative of the entire embryo's chromosomal constitution. This underscores the necessity for alternative, preferably non-invasive, methods of embryo quality assessment. A comprehensive review by Silvia Toporcerová systematically analyzed the potential of various components of the embryonic secretome as a non-invasive platform for preimplantation testing and IVF outcome prediction [

19]. These components include extracellular genomic DNA, mitochondrial DNA, mRNA, long non-coding RNAs, small RNAs, proteins (e.g., VEGF-A, IL-6, histidine-rich glycoprotein HRG, EMMPRIN, HLA-G, various interleukins, LIF, GM-CSF, JARID2, hCG isoforms), and amino acids (e.g., leucine, alanine, serine). While the analysis of extracellular genomic DNA (ni-PGT-A) – released into the spent culture medium via apoptosis and within extracellular vesicles – demonstrates fewer diagnostic errors regarding embryonic mosaicism compared to iPGT-A (with 78% concordance between the methods), ni-PGT-A similarly fails to inform on the blastocyst's implantation potential. For other secretome components, the review concludes that a lack of reproducibility, validation, and robust clinical evaluation currently precludes their practical application, highlighting the need for further large-scale randomized controlled trials.

A promising frontier in reproductive biology involves the analysis of piwi-interacting RNAs (piwiRNAs), a class of small non-coding RNAs, in the spent embryo culture medium. piwiRNAs serve as crucial "guardians of the genome" by mediating transcriptional and post-transcriptional silencing of mobile genetic elements [

20,

21]. Consequently, an imbalance in piwiRNA composition could lead to genomic instability through the increased activity of repetitive sequences. Furthermore, PIWI proteins are instrumental in regulating the proliferation and maintenance of germline stem cells, the progenitors of oocytes and spermatozoa [

22,

23]; the quality of these gametes is a primary determinant of subsequent embryonic developmental potential. Our research group was the first to identify a correlation between the levels of specific piwiRNAs in the spent culture medium and the quality of morula and blastocyst stage embryos across various morphological grades, paving the way for a non-invasive test system to determine implantation potential independent of karyotype [

24,

25,

26].

In a recent investigation utilizing deep sequencing of small non-coding RNAs followed by quantitative RT-PCR validation, we analyzed spent media from day 5 blastocysts with known iPGT-A results and subsequent ART outcomes after euploid blastocyst transfer. This work yielded logistic regression models capable of identifying euploid blastocysts with high implantation potential based on the levels of specific extracellular piwiRNAs [

27]. The objective of the present study was to validate these identified marker piwiRNAs using an independent cohort of samples derived from spent culture media of day 5 blastocysts and from that of developmentally delayed embryos that formed late blastocysts on day 6 post fertilization.

3. Discussion

This study successfully validated a set of marker piwiRNA molecules, previously identified by our group [

27], on an independent cohort of spent blastocyst culture media. These molecules are associated with critical aspects of blastocyst quality, namely chromosomal ploidy and implantation competence. A key innovation of the present work was the development of logistic regression models tailored to embryos with differing developmental kinetics, specifically those forming late blastocysts on either day 5 or day 6 post-fertilization. Our earlier models for day 5 blastocysts [

27] often displayed a marked disparity between sensitivity and specificity, leading to either over-diagnosis of high-potential euploid embryos or over-diagnosis of poor-quality embryos. To address this, we implemented several methodological refinements.

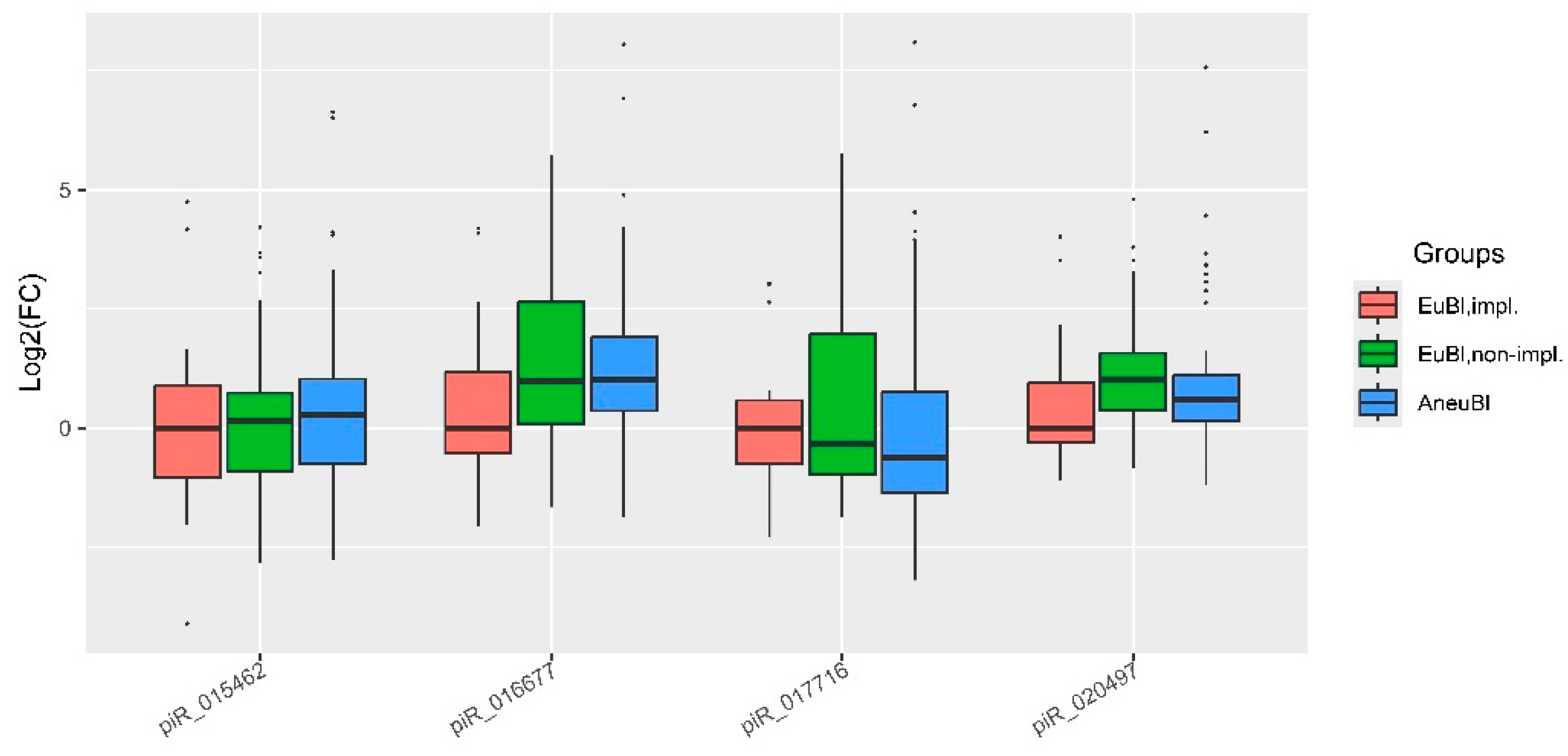

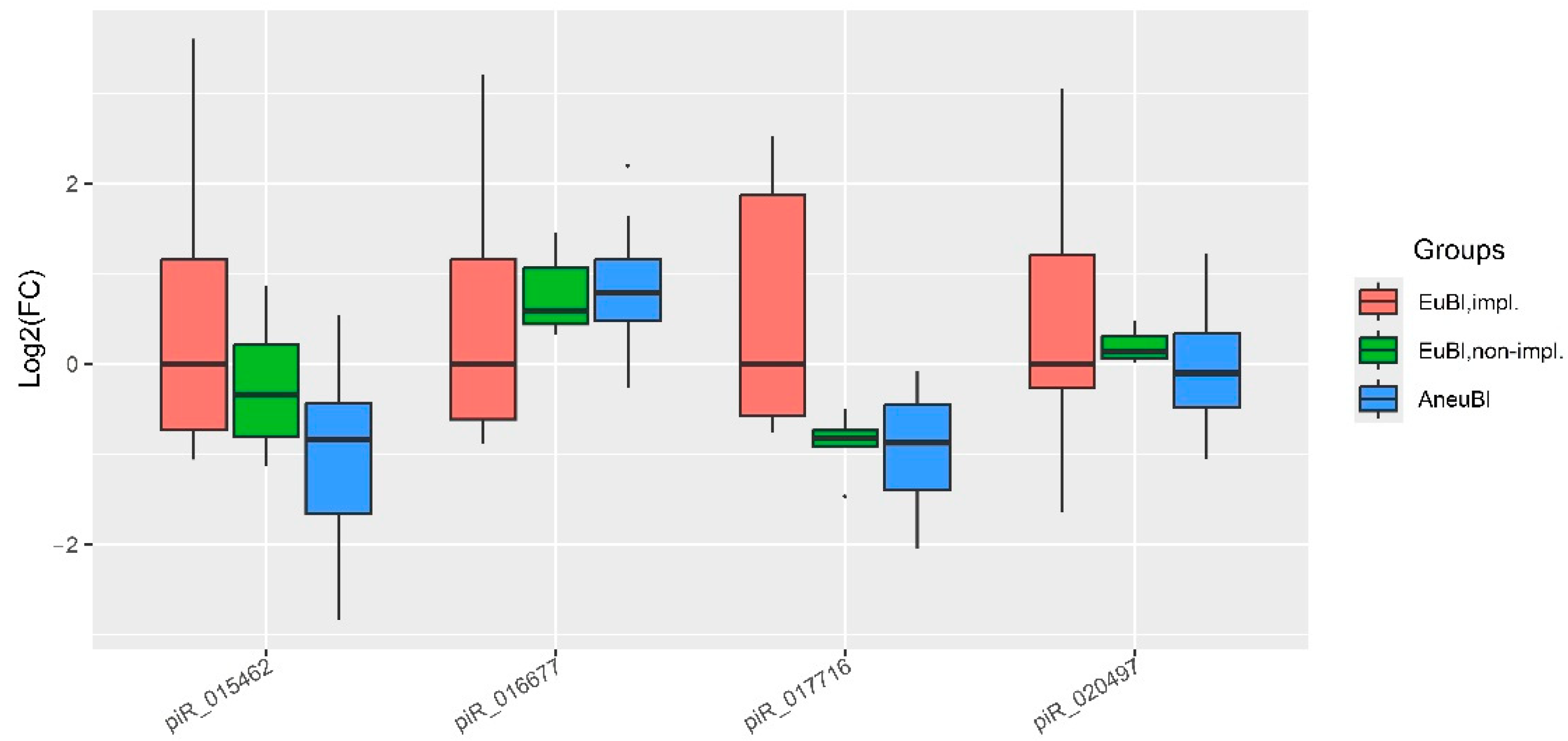

A critical procedural enhancement was the consistent normalization of each spent medium sample against its corresponding lot-matched control medium, incubated under identical temporal and thermal conditions. This step is crucial when using serum-containing media, as different lots can vary substantially in their baseline composition of small non-coding RNAs, including piwiRNAs, and incubation conditions can differentially affect RNA degradation rates, thereby confounding quantitative analysis. The importance of controlling for nucleic acid degradation in spent media is also emphasized in studies utilizing extracellular embryonic DNA for ni-PGT-A [

29]. A second key methodological refinement involved the use of a different quantitative metric for inter-group comparisons. We calculated the fold change for each marker piwiRNA in every spent medium sample relative to the median value observed in the reference group of euploid, implantation-competent embryos. This approach biologically contextualizes the data by quantifying the deviation of a given sample from an optimal, validated benchmark. It also helps to mitigate technical variations arising from different threshold determination algorithms inherent to various real-time PCR platforms.

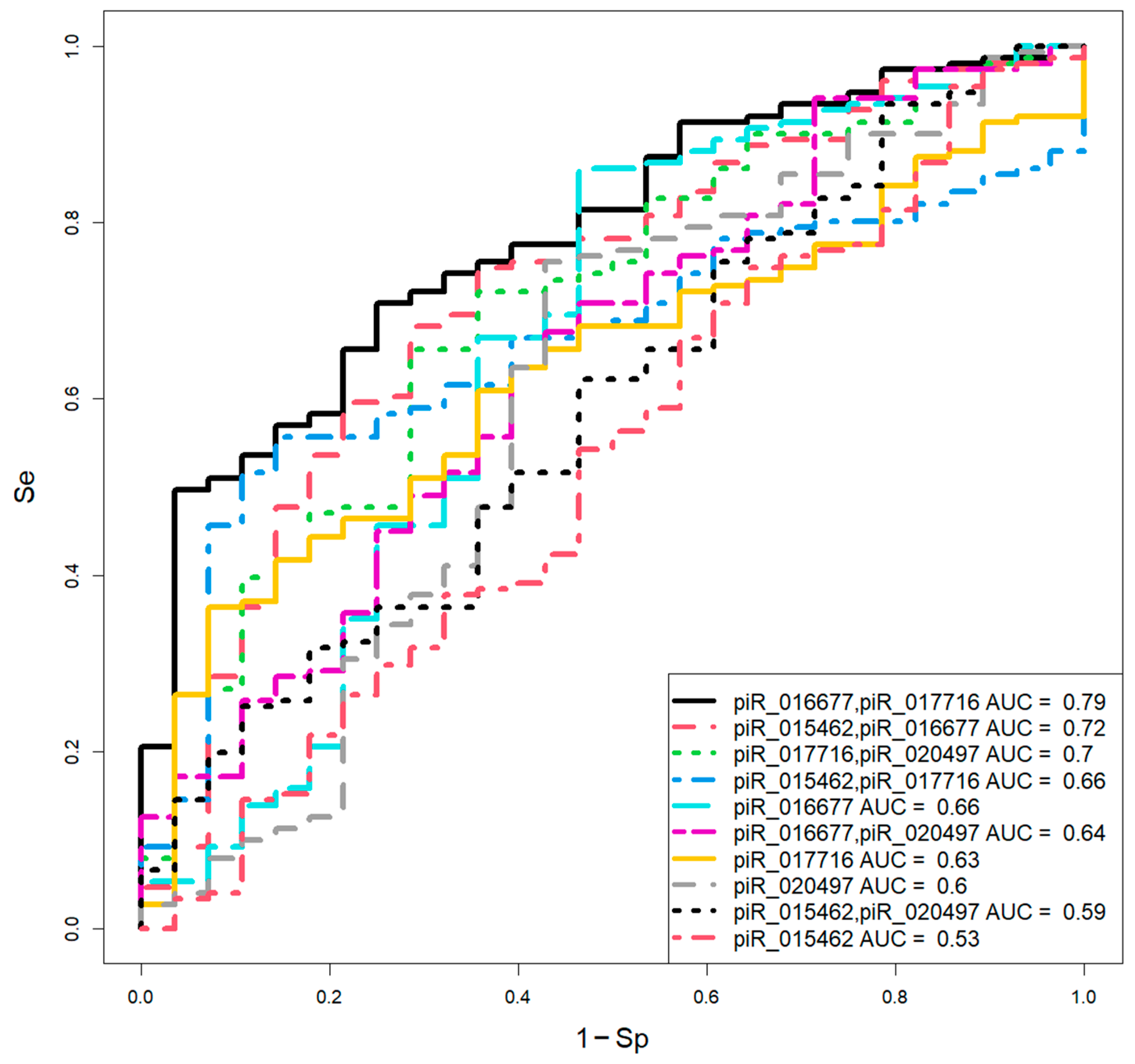

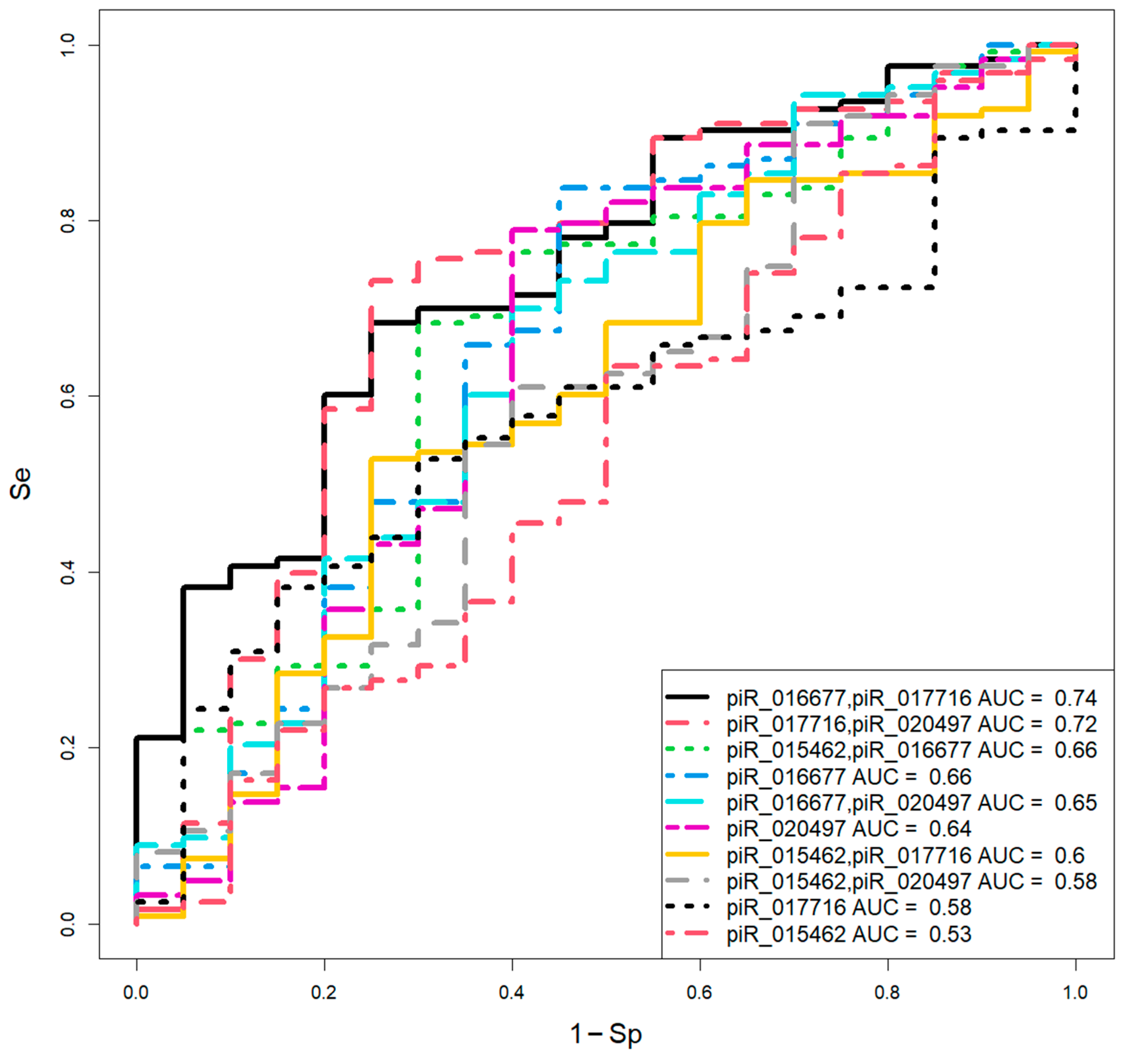

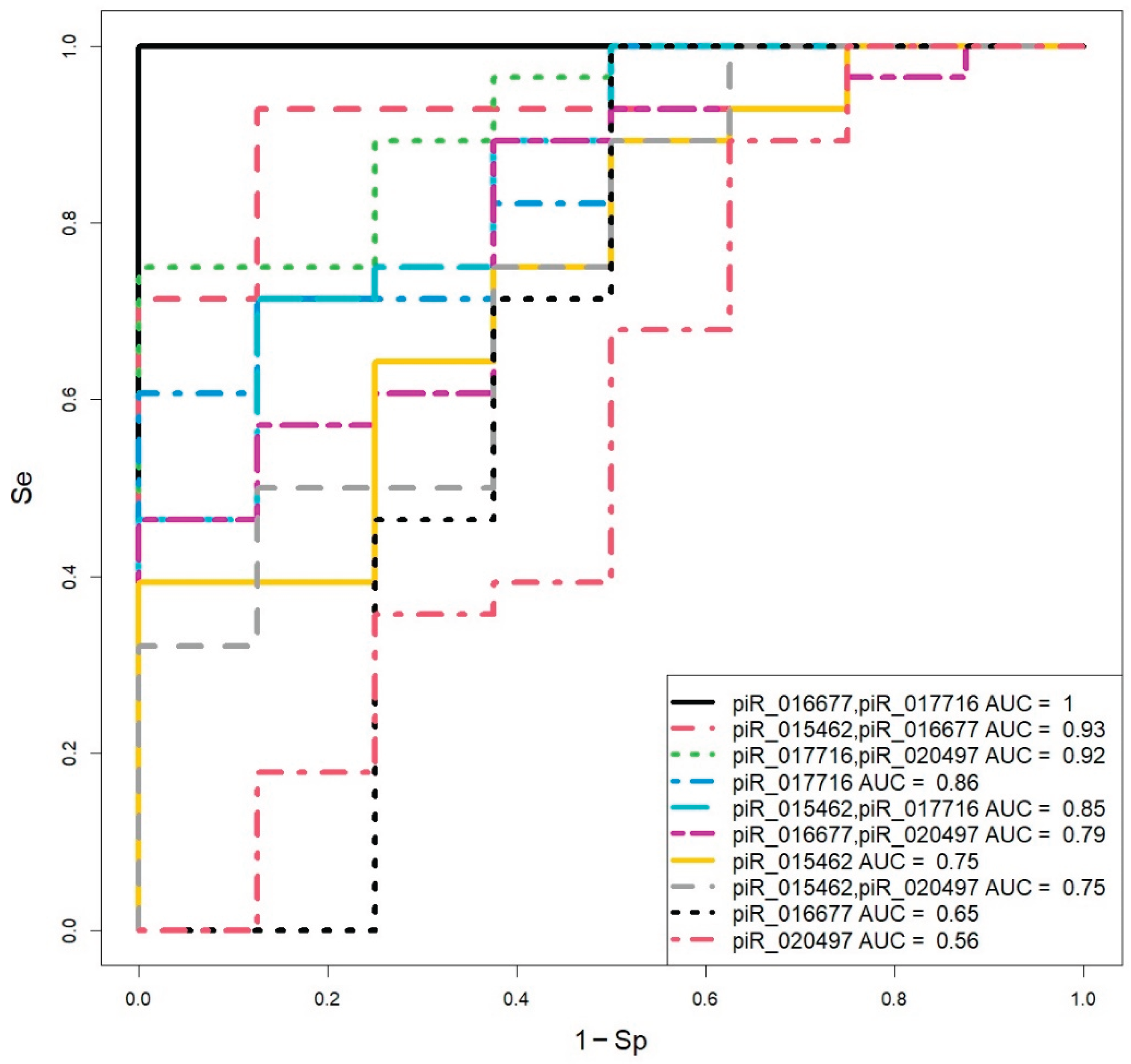

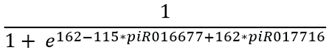

To our knowledge, no other research group has employed piwiRNAs to develop logistic regression models for the simultaneous assessment of embryonic ploidy and implantation potential. We developed specific models for day 5 blastocysts (piR_016677, piR_017716: Se=69%, Sp=75%; piR_017716, piR_020497: Se = 73%, Sp = 75%) and for day 6 blastocysts (piR_016677, piR_017716: Se = 100%, Sp = 100%; piR_015462, piR_016677: Se = 93%, Sp = 88%). Furthermore, to streamline the clinical selection of blastocysts for transfer, we identified unique piwiRNA combinations that form the basis of unified models applicable regardless of the day of blastocyst formation (day 5 or 6): piR_015462, piR_016677 (Se = 68%, Sp = 71%) and piR_017716, piR_020497 (Se = 66%, Sp = 71%). The molecules piR_015462 and piR_020497, which showed significant level differences between day 5 and day 6 poor-quality blastocysts, were likely excluded from the top-performing unified models for this reason.

Current non-invasive preimplantation embryo assessment strategies primarily focus on analyzing genomic or mitochondrial DNA from spent culture medium or blastocoelic fluid [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. While these methods can evaluate ploidy, they provide no direct information on implantation potential. Alternative non-invasive approaches rely on morphological and morphokinetic parameters [

36,

37,

38], which cannot provide a definitive conclusion regarding the ploidy of the embryo and its implantation potential. Notably, embryos with delayed development can still result in successful pregnancies and live births. Reported live birth rates for day 5, 6, and 7 blastocysts are 63%, 51%, and 14%, respectively (Liu et al. [

39]), and 69%, 55%, and 36% (Lane et al. [

40]). However, the incidence of aneuploidy is higher among day 7 blastocysts (42% euploid) compared to day 6 (54% euploid) and day 5 (63% euploid) blastocysts [

40], justifying iPGT-A recommendation for patients with only delayed embryos. The piwiRNA-based RT-PCR and logistic regression models developed herein present a promising alternative for assessing the quality of developmentally delayed blastocysts.

A fundamental function of piwiRNAs is to maintain genomic stability by facilitating the nuclear silencing of retrotransposons within the RISC complex, which recruits histone deacetylases, methyltransferases, and DNA methyltransferases to enact transcriptional repression [

41]. In humans, the primary active retrotransposon is LINE-1, whose transcription is regulated via CpG methylation and histone deacetylation [

42]. Aberrant LINE-1 expression is linked to genomic instability [

43] and has been correlated with meiotic defects and aneuploidy in oocytes [

44], as well as defective meiosis and sterility in male germ cells [

45]. According to the piRBase database, the marker piwiRNAs identified in this study – piR_016677, piR_017716, piR_020497, and piR_015462 – are encoded by LINE-1 sequences, suggesting their potential role in the epigenetic silencing of LINE-1 during gametogenesis and early embryogenesis.

Beyond transposon suppression, piwiRNAs regulate cellular signaling pathways through diverse mechanisms [

41]. For instance, pachytene piwiRNAs can guide the MIWI protein to target mRNAs, leading to their deadenylation and degradation via CAF1 [

46], or to direct mRNA cleavage [

47]. Using the miRanda algorithm [

25], and bioDBnet (

https://biodbnet-abcc.ncifcrf.gov/db/db2db.php) for gene symbol conversion, we identified potential mRNA targets for these piwiRNAs (

Table S2). Metascape enrichment analysis revealed that the protein products of these target genes are significantly involved in biological processes critical for gametogenesis and early embryogenesis, including male gamete generation, microtubule-based processes, cell morphogenesis, and the Hippo signaling pathway (

Table S3). Several target genes exemplify experimentally proven roles in genomic stability, spindle formation, kinetochore function, and cytokinesis—processes whose dysregulation leads to aneuploidy. For example, APOBEC3, a potential target of hsa_piR_020497, piR_016677, and piR_017716, is involved in defending against uncontrolled LINE-1 activity during gametogenesis and early development [

45]. Polo-like kinase 3 (PLK3, a target of hsa_piR_020497) regulates cell cycle progression and cytokinesis [

48]. PLK1, a closely related kinase, promotes centrosome disjunction by maintaining NEK2A activity, which phosphorylates the centrosomal linker protein rootletin (CROCC, a target of hsa_piR_015462). Mutations in CROCC cause severe chromosomal instability and segregation errors [

49]. Furthermore, subunits of the PP2A phosphatase (e.g., PPP2R5B, a target of hsa_piR_015462) interact with PLK1 and are crucial for maintaining genomic stability [

50]; inhibition of PPP2R5B perturbs sister chromatid cohesion.

The centrosome serves as a hub for the proteasome and its regulatory components [

51]. In eukaryotic cells, the 26S proteasome, comprising a 20S core and a 19S regulatory complexes, degrades the majority of intracellular proteins [

52]. PSMD2 (a target of hsa_piR_016677) is a subunit of the 19S complex [

53]. Notably, Polo-like kinases themselves are subject to ubiquitin-mediated degradation by the proteasome [

48]. This suggests a sophisticated feedback mechanism wherein hsa_piR_016677 and piR_020497 could influence spindle assembly and chromosome segregation by modulating the levels of PSMD2 and PLK3, respectively.

The anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), activated by Cdc20 or Cdh1 (a target of hsa_piR_015462), is another critical cell-cycle regulator employing ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis. During oogenesis, APC/CCdh1 maintains the prophase I arrest of primordial follicles by degrading cyclin B1 [

54]. In anaphase I, APC/CCdh1 facilitates chromosome separation by enabling the phosphorylation and dissociation of the centromeric protein Sgo2 [

55]. Deletion of Apc or Cdh1 in oocytes prevents Sgo2 dissociation and chromosome segregation, leading to aneuploidy.

The piwiRNAs associated with blastocyst aneuploidy in our study also potentially regulate centriolar proteins vital for gametogenesis. CEP128 (target of hsa_piR_015462), CEP164 (target of hsa_piR_017716), and basomuclin 1 (BNC1, target of hsa_piR_015462) are key components of the sperm's maternal centriole appendage, essential for organizing centriolar microtubules and the axoneme [

56,

57,

58,

59]. BNC1 is also critical for oogenesis, as its inhibition allows fertilization but arrests embryonic development at the 2-cell stage [

60].

The microtubule-associated protein MAP1A (target of hsa_piR_016677) plays a vital role in spermatogenesis by stabilizing microtubule structures within Sertoli cells, which are necessary for the directed transport of developing germ cells [

61]. Disruption of this process impairs male fertility. The protein RASSF1A (target of hsa_piR_015462) promotes microtubule stability by inhibiting HDAC6. Stable microtubules are essential for intracellular transport, centrosome/Golgi organization, and focal adhesion stability [

62].

During preimplantation development, starting at the 8-cell stage, blastomeres undergo polarization and compaction, processes dependent on cytoskeletal reorganization [

63]. The focal adhesion protein paxillin (PXN, target of hsa_piR_017716) interacts with α-tubulin [

64], and its upregulation post-compaction is implicated in forming the adhesive properties necessary for implantation [

65]. The adhesion protein CDH23 (target of hsa_piR_016677) regulates microtubule network stability and, together with PLEKHA7 (target of hsa_piR_015462), stabilizes adhesive intercellular contacts [

66,

67].

In summary, the selection of above mentioned specific piwiRNAs for quantifying blastocyst quality is strongly supported by their potential biological roles, spanning from genomic stability maintenance via LINE-1 regulation to direct involvement in cell cycle control, spindle assembly, and the cellular adhesion processes imperative for successful implantation.

(1)

(1)